Abstract

Background

Global patterns in atopic dermatitis (AD) incidence and their associations with modifiable risk factors remain unclear.

Objective

We sought to analyze global trends in AD incidence and identify associated socioeconomic, environmental, and lifestyle factors contributing to its global disparities and epidemics.

Methods

Data on AD in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021 were extracted from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2021. Age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) were calculated by sex and region. Socioeconomic development was measured by the Sociodemographic Index, a composite indicator of income, education, and fertility. Modifiable risk factors—including high body mass index, low physical activity, air pollution, and unhealthy diets—were quantified using summary exposure values, reflecting the population-level exposure to each risk. Dietary risks included diet high in sugar-sweetened beverages, processed meat, and sodium, and low intake of whole grains. Relationships between ASIRs and summary exposure values were independently assessed using restricted cubic spline regression.

Results

In 2021, 16.0 million new cases of AD were recorded globally, with the highest ASIRs in high-income Asia Pacific (474.8 per 100,000 population) and Western Europe (421.7 per 100,000 population) geographically and higher ASIRs in women. AD incidence strongly increased with socioeconomic development. Among modifiable risk factors, high body mass index, low physical activity, and nitrogen dioxide pollution formed positive associations with AD risk. Diets rich in sugar-sweetened beverages, processed meat, and sodium and diet low in whole grains further increased the risk.

Conclusions

Global disparities in AD incidence trends are closely linked to socioeconomic development and modifiable risk factors, including obesity, air pollution, and unhealthy diets. Addressing these factors through targeted public health policies is essential to mitigating the global burden of AD, particularly in industrialized and rapidly developing regions.

Key words: Atopic dermatitis, incidence, Global Burden of Disease study, risk factors

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease characterized by recurrent eczematous lesions and intense itching.1 AD affects up to 20% of children and 2.1% to approximately 4.9% of adults in high-income countries, imposing a significant health and economic burden.2,3 Despite extensive research on AD prevalence and disability-adjusted life years, data on its global incidence remain limited. Although emerging treatments such as biologics have achieved significant success, AD remains incurable.1 The World Health Organization has included AD as part of its new framework for the primary care dermatological health strategy, highlighting global disparities in the burden of AD as a representative issue.4 Thus, understanding incidence trends is essential to identify high-risk populations and formulate targeted prevention strategies.

Previous studies have shown that AD is more common in industrialized countries, but a comprehensive global analysis of its geographic distribution and drivers is lacking. Most incidence studies have focused on specific regions, particularly Western Europe, with limited data from developing countries.5 Furthermore, variations in study design and definitions complicate global comparisons.6 Evidence suggests a heavier AD burden in countries with higher socioeconomic status,7 linked to industrialization-related factors such as air pollution and processed food consumption.8,9 However, a comprehensive global analysis integrating these risk factors is lacking.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021 was led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. It has 100,983 data sources calculated counts and age-standardized rates for 7 super regions, 21 regions, 204 countries and territories (including 21 countries with subnational sites), and 811 subnational sites worldwide from 1990 to 2021.10 All data can be accessed at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results. We aimed to assess global and regional trends in AD incidence and explore socioeconomic, environmental, and lifestyle factors contributing to these trends. We extracted age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) of AD from GBD 2021 to report the incidence risks across different periods, sexes, age groups, regions, and countries. The ASIRs were reported per 100,000 population, and the 95% uncertainty intervals were calculated from the 2.5th and 97.5th ordered values obtained from 500 random extractions from the posterior distribution.10 The estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) was used to describe the annual average trend in the changes in ASIR from 1990 to 2021. According to ln(ASIR) = ɑ + β × YEAR + ε, where β was the trend for ASIR over year and ε represented the error, the EAPC was calculated as: [exp(β) − 1] × 100.11

In addition, we examined the relationship between AD incidence and Sociodemographic Index (SDI). The SDI is an important metric for assessing the socioeconomic development level of a country or region. It is defined as the geometric mean of the total fertility rate for the population younger than 25 years, the average years of education for the population aged 15 years and older, and the lag-distributed income per capita. The SDI ranges from 0 to 1, and an increase in SDI indicates higher levels of socioeconomic development. Moreover, according to SDI values, GBD 2021 classified countries into 5 levels: high-, high-middle, middle-, low-middle, and low-SDI regions.10 Based on previous studies, risk factors primarily included ambient particulate matter pollution, ozone pollution, nitrogen dioxide pollution, high body mass index, low physical activity, diet high in sugar-sweetened beverage, diet low in whole grains, diet high in processed meat, diet high in red meat, diet high in sodium, and diet low in milk.12, 13, 14 These factors may also serve as indicators of industrialization and urbanization processes and were measured by summary exposure values (SEVs). The SEV is a key indicator in the GBD 2021, and it is a risk-weighted exposure level used to represent the overall population exposure to a risk factor. The value ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating that the population is exposed at the theoretical minimum risk exposure level, and 100 means that the population is exposed at the maximum level. The definitions of these risk factors in GBD 2021 have been established in previous studies.15 We used restricted cubic splines to examine the nonlinear relationship between incidence rates and modifiable factors across 204 countries. In addition, we applied a logarithmic function to address data dispersion issues in certain countries. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), with a significance level at P less than .05.

Results and discussion

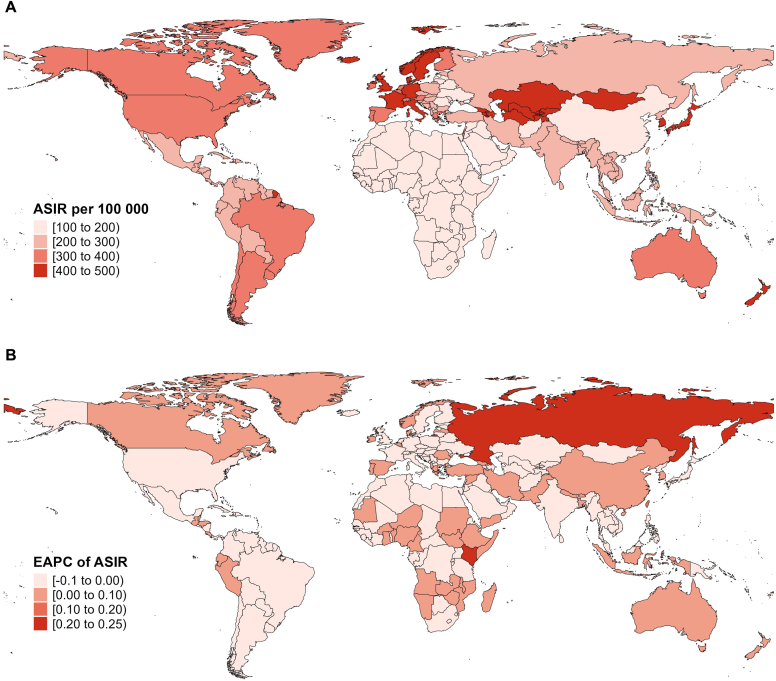

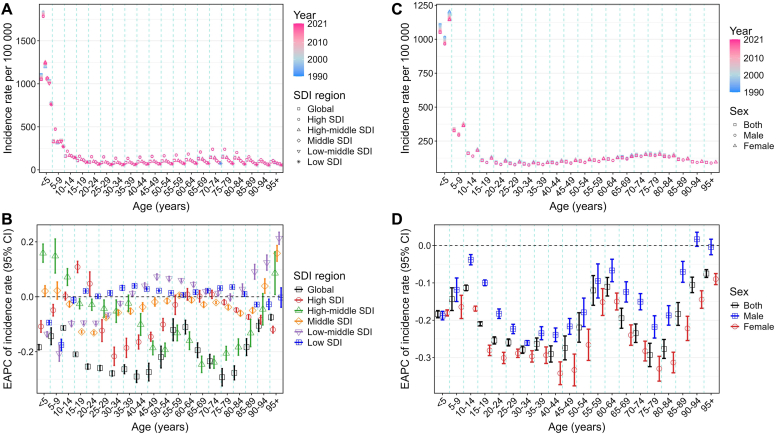

Our study revealed significant geographical disparities in AD global incidence (Table I; Fig 1). In 2021, the global AD incidence was 16.0 million new cases, with the highest ASIR observed in the high SDI region (356.6 per 100,000). High-income Asia Pacific (474.8 per 100,000 population) and Western Europe (421.7 per 100,000 population) were the most affected regions (Table I). At the national level, France, Japan, and Italy exhibited the highest ASIRs, whereas Latvia, Rwanda, and Congo reported the lowest rates (Table I; Fig 1, A). From 1990 to 2021, the global ASIR of AD decreased slightly (EAPC = −0.200), but significant regional disparities emerged. Eastern Europe showed the largest increase in AD incidence (EAPC = 0.223), whereas the high SDI region maintained persistently elevated rates (Table I). In 2021, women had a higher AD risk (241.9 per 100,000) than men (200.2 per 100,000), with a more significant decline in ASIR in females (EAPC = −0.218) (Table I). The age distribution showed 2 major peaks: younger than 5 years and 75 to 79 years, with a “W” pattern in ASIR across the lifespan. Among children (0-19 years), high-SDI regions had a higher EAPC, whereas lower-SDI regions showed higher EAPCs in older age groups (Fig 2).

Table I.

Incident cases and ASIR rate per 100,000 people for AD in 1990 and 2021, along with its EAPC from 1990 to 2021

| Group | 1990 |

2021 |

EAPC in ASIR from 1990 to 2021 (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASIR per 100,000 people (95% UI) | Incidence cases (95% UI) | ASIR per 100,000 people (95% UI) | Incidence cases (95% UI) | ||

| Global | 234.8 (223 to 247.1) | 13,479,211.6 (12,764,379.7 to 14,220,772) | 220.6 (209.5 to 232) | 16,006,680.6 (15,211,260 to 16,819,872.2) | −0.200 (−0.207 to −0.193) |

| Male | 211.6 (200.8 to 223) | 6,183,579.9 (5,850,344.8 to 6,536,379.8) | 200.2 (189.9 to 210.8) | 7,381,252.1 (7,002,029.3 to 7,757,744.1) | −0.176 (−0.183 to −0.169) |

| Female | 258.8 (245.7 to 272.5) | 7,295,631.7 (6,912,354.5 to 7,687,316.8) | 241.9 (229.5 to 255) | 8,625,428.5 (8,207,394.8 to 9,079,673.4) | −0.218 (−0.226 to −0.211) |

| SDI region | |||||

| High SDI | 364.4 (345.4 to 384.5) | 2,698,867.8 (2,568,563 to 2,837,275.6) | 356.6 (338 to 376.4) | 2,896,045.5 (2,767,868.1 to 3,033,370.6) | −0.082 (−0.098 to −0.066) |

| High-middle SDI | 240.4 (227.5 to 254) | 2,377,462.7 (2,249,771.5 to 2,512,496.9) | 242.1 (229 to 255.8) | 2,375,916.9 (2,259,336.1 to 2,493,749.7) | 0.064 (0.031 to 0.098) |

| Middle SDI | 217.9 (207 to 229.4) | 4,105,159.8 (3,890,280.9 to 4,333,231.6) | 216.9 (205.9 to 228) | 4,548,528.4 (4,328,067.5 to 4,773,827.1) | −0.016 (−0.022 to −0.009) |

| Low-middle SDI | 206 (194.7 to 218.5) | 3,086,221.8 (2,905,941.1 to 3,292,062.9) | 199.3 (188.5 to 210.9) | 3,851,926 (3,639,019.9 to 4,084,140.3) | −0.127 (−0.135 to −0.118) |

| Low SDI | 168.7 (159.8 to 178.3) | 1,199,564.3 (1,125,599.2 to 1,273,999.8) | 164 (155.3 to 173.2) | 2,321,227 (2,184,646.2 to 2,461,868.8) | −0.094 (−0.103 to −0.086) |

| GBD region | |||||

| High-income Asia Pacific | 474 (447.6 to 501.7) | 626,876.6 (594,028.3 to 661,841.7) | 474.8 (448.4 to 505.4) | 548,317.2 (523,498.1 to 576,178.4) | −0.001 (−0.016 to 0.014) |

| High-income North America | 334.7 (319.7 to 350.3) | 846,111.4 (811,246.6 to 881,428) | 334.6 (319.4 to 349.7) | 1,017,928.4 (978,333.6 to 1,058,953.3) | −0.015 (−0.034 to 0.004) |

| Western Europe | 423.1 (395.9 to 450.9) | 1,248,808.6 (1,177,134.8 to 1,322,702.4) | 421.7 (394.6 to 449) | 1,314,246.3 (1,247,463 to 1,386,446.3) | −0.015 (−0.023 to −0.007) |

| Australasia | 338.6 (315.8 to 361.5) | 58,508.2 (54,869.6 to 62,300.9) | 338.7 (314.3 to 364.6) | 79,312.1 (74,364.7 to 84,575.2) | 0.001 (−0.007 to 0.010) |

| Southern Latin America | 388 (357.9 to 417.6) | 196,769.2 (181,414.8 to 211,882.5) | 387.8 (357.7 to 417.3) | 210,489 (195,432.1 to 225,391.9) | −0.002 (−0.002 to −0.002) |

| Andean Latin America | 226.7 (214.7 to 239.3) | 101,452.8 (95,491.1 to 107,998.9) | 226.5 (214.5 to 239.2) | 144,620 (136,875.6 to 152,711.1) | 0.008 (−0.002 to 0.018) |

| Tropical Latin America | 300.9 (286.2 to 315.7) | 493,228.4 (465,889.2 to 519,774.6) | 301.1 (286.2 to 316.1) | 597,030.7 (570,728.3 to 624,861.1) | −0.004 (−0.008 to 0.000) |

| Central Latin America | 249.1 (234.8 to 265) | 495,904.7 (464,290.5 to 529,533) | 248.1 (233.8 to 263.5) | 562,683.9 (531,464.3 to 597,527.9) | −0.021 (−0.026 to −0.015) |

| Caribbean | 263.2 (244.2 to 283.5) | 99,841.8 (92,382 to 107,678.7) | 263.1 (244 to 283.3) | 112,945.6 (104,990 to 121,307.8) | −0.002 (−0.002 to −0.002) |

| Eastern Europe | 211.6 (200.8 to 223.4) | 424,399.4 (405,060.6 to 445,937.5) | 222.5 (211 to 235.3) | 342,998.7 (329,031.7 to 358,216.4) | 0.223 (0.181 to 0.266) |

| Central Europe | 225.9 (212.6 to 241.5) | 235,993.1 (223,197.4 to 251,024.2) | 228 (214.9 to 244.4) | 175,479.5 (167,077.3 to 185,113.8) | 0.019 (0.014 to 0.024) |

| Central Asia | 414.9 (383.2 to 447.6) | 354,069.2 (326,261 to 384,109.6) | 413.8 (381.9 to 446.6) | 405,802.9 (374,757.1 to 438,245) | −0.009 (−0.009 to −0.008) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 188.4 (176.3 to 200.4) | 827,031.8 (769,144.6 to 884,216.5) | 183.1 (171 to 194.8) | 1,140,446.5 (1,064,110.5 to 1,214,779.8) | −0.110 (−0.115 to −0.104) |

| South Asia | 207.2 (195.4 to 220.5) | 2,905,258.8 (2,727,683 to 3,106,626.8) | 207.3 (195.4 to 220.6) | 3,536,548.4 (3,330,855.1 to 3,765,446.5) | −0.016 (−0.026 to −0.005) |

| Southeast Asia | 221 (208.7 to 233.7) | 1,182,083.7 (1,111,373.2 to 1,254,146.4) | 221.5 (209.6 to 233.9) | 1,391,475.2 (1,317,120 to 1,470,677.4) | 0.013 (0.010 to 0.017) |

| East Asia | 199.9 (189.8 to 210.5) | 2,363,055.9 (2,243,745.3 to 2,485,872.8) | 198.5 (189 to 208.5) | 2,262,743.8 (2,165,029.2 to 2,363,932.1) | −0.004 (−0.029 to 0.021) |

| Oceania | 236.1 (217.9 to 254.7) | 19,891.2 (18,236.8 to 21,619.7) | 236 (217.8 to 254.7) | 39,385.3 (36,179.8 to 42,678) | −0.001 (−0.002 to −0.001) |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 146.5 (139.2 to 153.9) | 391,159.3 (368,936.5 to 413,278.2) | 147 (139.6 to 154.2) | 942,165.1 (889,268.4 to 995,609.5) | 0.018 (0.012 to 0.024) |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 146.1 (138 to 154) | 393,284.7 (369,798.5 to 418,182.3) | 147.8 (139.3 to 155.8) | 794,689.4 (743,935.2 to 842,898.1) | 0.049 (0.043 to 0.055) |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 146.2 (135.8 to 157.2) | 116,342.1 (106,890.7 to 125,863.8) | 146.1 (135.7 to 157) | 263,640.9 (242,411.7 to 285,574.9) | −0.004 (−0.005 to −0.004) |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 152.9 (143.9 to 161.8) | 99,141.1 (93,064.6 to 105,185.6) | 152.8 (143.7 to 161.6) | 123,731.7 (116,275 to 131,091.9) | −0.003 (−0.004 to −0.003) |

| Countries and territories∗ | |||||

| Japan | 494.2 (467.7 to 521.7) | 450,799.6 (428,843.3 to 473,321) | 494.7 (467.7 to 525.8) | 397,124 (381,075.8 to 415,858.3) | −0.023 (−0.102 to 0.056) |

| France | 474 (436.9 to 515.1) | 223,481.8 (207,528.9 to 240,616.7) | 474.1 (436.9 to 515.2) | 235,809.1 (220,132.2 to 251,940.3) | −0.018 (−0.223 to 0.188) |

| Italy | 453.5 (427.9 to 480.7) | 181,778.2 (172,284.8 to 191,021.3) | 453.4 (427.8 to 480.5) | 176,007 (167,571.5 to 184,244.7) | −0.009 (−0.173 to 0.156) |

| Denmark | 452.3 (413.2 to 487) | 17,327.8 (15,991.6 to 18,606.7) | 452.2 (413.1 to 486.9) | 195,88.6 (18,159.7 to 20,987.3) | 0.023 (−0.164 to 0.210) |

| Republic of Korea | 434.9 (402.6 to 468.1) | 165,453.8 (152,963.4 to 179,059.2) | 435.3 (403.9 to 468.6) | 134,273.1 (125,819.7 to 143,008.7) | 0.016 (−0.117 to 0.148) |

| United Kingdom | 435.6 (412.3 to 459) | 200,318.2 (190,564 to 209,913.2) | 430.3 (406.4 to 455.5) | 216,609.7 (206,535.1 to 227,886.4) | −0.057 (−0.211 to 0.096) |

| Norway | 426.5 (403.1 to 450) | 14,372.8 (13,680.1 to 15,077.8) | 427.7 (404.2 to 452) | 16,917.2 (16,104.4 to 17,703.1) | 0.022 (−0.155 to 0.200) |

| Iceland | 424.9 (390.8 to 458.5) | 974.3 (898.7 to 1048.9) | 423.3 (389.5 to 459.3) | 1,166.7 (1,082.9 to 1,250.6) | −0.021 (−0.206 to 0.165) |

| Brunei Darussalam | 421.9 (390.9 to 451.3) | 1,288.6 (1,187.3 to 1,386.3) | 421.9 (391 to 451.2) | 1,533.6 (1,426.2 to 1,641.6) | −0.001 (−0.104 to 0.103) |

| New Zealand | 412.8 (388.8 to 439.7) | 12,414.5 (11,735.1 to 13,150.1) | 414.7 (390.2 to 438.7) | 16,456.6 (15,590.6 to 17,304) | 0.022 (−0.144 to 0.189) |

| Kyrgyzstan | 415.2 (383.2 to 448.3) | 23,639.6 (21,754.5 to 25,686.8) | 414.6 (382.6 to 447.5) | 31,386.2 (28,895.5 to 33,988.5) | −0.001 (−0.294 to 0.293) |

| Mongolia | 414.8 (382.8 to 447.8) | 12,176.4 (11,183.6 to 13,256.4) | 414.5 (382.6 to 447.5) | 15,430.3 (14,211.3 to 16,717.8) | −0.001 (−0.294 to 0.293) |

| Kazakhstan | 415.2 (383.2 to 448.2) | 74,224 (68,395.9 to 80,447.2) | 414.5 (382.6 to 447.4) | 79,700.8 (73,570.9 to 86,088.8) | −0.002 (−0.295 to 0.292) |

| Tajikistan | 414.7 (382.8 to 447.7) | 32,734.1 (30,037.7 to 35,716.7) | 413.7 (381.9 to 446.6) | 50,218 (46,257.3 to 54,542.4) | −0.003 (−0.296 to 0.291) |

| Uzbekistan | 415 (383.1 to 448) | 120,006.3 (110,278.4 to 130,719.3) | 413.7 (381.9 to 446.6) | 151,167 (139,527.1 to 163,702.3) | −0.003 (−0.296 to 0.290) |

| Armenia | 414.7 (382.8 to 447.6) | 15,175.7 (13,992.5 to 16,443.7) | 413.3 (381.5 to 446) | 9,452 (8,764.9 to 10,116.2) | −0.005 (−0.297 to 0.289) |

| Turkmenistan | 415.1 (383.1 to 448.1) | 20,907 (19,212.9 to 22,768.3) | 413.3 (381.4 to 446.1) | 21,840 (20,150.1 to 23,607.2) | −0.005 (−0.298 to 0.289) |

| Georgia | 411.9 (377.6 to 444.7) | 20,580.5 (18,932.8 to 22,203.6) | 412.6 (379.4 to 443.9) | 11,919.1 (11,000.9 to 12,782.7) | 0.035 (−0.259 to 0.330) |

| Azerbaijan | 414.7 (382.9 to 447.7) | 34,625.5 (31,907.4 to 37,571.4) | 412.3 (380.5 to 444.9) | 34,689.5 (32,118.9 to 37,260.7) | −0.008 (−0.301 to 0.286) |

| Sweden | 404.1 (382.9 to 427.9) | 27,473.8 (26,210.8 to 28,781.4) | 403.9 (382.8 to 427.8) | 31,708.3 (30,288.4 to 33,221.1) | −0.001 (−0.179 to 0.179) |

| Germany | 402.1 (376.3 to 429.3) | 238,227.5 (224,211.5 to 252,475.9) | 400.9 (373.9 to 427.9) | 239,716.8 (226,161.1 to 252,860.5) | −0.023 (−0.185 to 0.140) |

| Monaco | 395.1 (365.7 to 424.1) | 77.5 (73.1 to 82) | 396 (366.7 to 424.9) | 102.4 (96.7 to 108.4) | 0.004 (−0.175 to 0.182) |

| Portugal | 395.7 (366.4 to 424.7) | 30,759.3 (28,696.4 to 32,813) | 395.8 (366.5 to 424.8) | 27,768.9 (26,175.8 to 29,372.6) | 0.000 (−0.178 to 0.179) |

| Ireland | 395.4 (366.1 to 424.4) | 12,932.5 (12,002.1 to 13,897.5) | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.6) | 15,338.3 (14,351.9 to 16,329.6) | 0.001 (−0.178 to 0.179) |

| Belgium | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.4) | 30,225.8 (28,282.7 to 32,138.5) | 395.5 (366.3 to 424.5) | 33,150.1 (31,134.1 to 35,152.8) | 0.000 (−0.178 to 0.179) |

| Israel | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.6) | 20,227.8 (18,681 to 21,724.5) | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.5) | 37,141 (34,409.1 to 39,788.9) | −0.000 (−0.179 to 0.178) |

| Finland | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.5) | 15,528.1 (14,547.6 to 16,505) | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.4) | 15,185.3 (14,299.2 to 16,102.1) | −0.001 (−0.179 to 0.178) |

| The Netherlands | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.5) | 45,748.7 (42,770.9 to 48,645.4) | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.4) | 48,845.2 (45,944.2 to 51,725.4) | −0.000 (−0.178 to 0.178) |

| Andorra | 394.6 (365.4 to 423.5) | 153.1 (143.2 to 163) | 395.4 (366.2 to 424.3) | 202.5 (190.6 to 214.6) | 0.004 (−0.174 to 0.182) |

| Luxembourg | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.5) | 1,146.1 (1,072.7 to 1,217.9) | 395.4 (366.1 to 424.3) | 1,821.3 (1,709.8 to 1,931.5) | −0.001 (−0.179 to 0.178) |

| Switzerland | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.4) | 20,364 (19,058 to 21,622.5) | 395.3 (366 to 424.2) | 25,068.6 (23,552.4 to 26,550.5) | −0.001 (−0.179 to 0.178) |

| Austria | 395.5 (366.2 to 424.5) | 23,162.5 (21,654.8 to 24,593.5) | 395.2 (366 to 424.2) | 24,907.4 (23,393.7 to 26,380.4) | −0.001 (−0.179 to 0.178) |

| San Marino | 395.7 (366.4 to 424.7) | 67 (62.7 to 71.2) | 395.2 (365.8 to 424.2) | 83.8 (79.1 to 88.8) | −0.002 (−0.180 to 0.177) |

| Malta | 395.6 (366.3 to 424.5) | 1,271 (1,184 to 1,358.5) | 395 (365.7 to 424) | 1,253 (1,181.3 to 1,327.2) | −0.002 (−0.180 to 0.177) |

| Singapore | 391.1 (358.1 to 422.1) | 9,334.6 (8,591.2 to 10,101.4) | 389 (359 to 420.8) | 15,386.5 (14,354.3 to 16,474.5) | −0.026 (−0.122 to 0.070) |

| Argentina | 388.1 (357.9 to 417.6) | 131,986.2 (121,666.8 to 142,060.7) | 387.8 (357.7 to 417.3) | 144,436.1 (133,963 to 154,818.1) | −0.001 (−0.152 to 0.151) |

| Uruguay | 387.9 (357.8 to 417.5) | 11,320.2 (10,466.4 to 12,130.5) | 387.7 (357.7 to 417.3) | 10,138.2 (9,415.9 to 10,837.2) | −0.001 (−0.152 to 0.151) |

| Chile | 387.9 (357.8 to 417.5) | 53,453.5 (49,368.3 to 57,682.8) | 387.7 (357.6 to 417.3) | 55,903.2 (51,983.9 to 59,745.1) | −0.000 (−0.152 to 0.152) |

| Spain | 384.8 (351.6 to 419.6) | 111,083 (102,448 to 120,297.9) | 384.8 (351.6 to 419.6) | 116,001.2 (107,586.1 to 124,691.8) | 0.002 (−0.171 to 0.176) |

| Cyprus | 375.8 (343 to 406.3) | 2,625.1 (2,407 to 2,831.8) | 375.8 (343 to 406.3) | 3,729.8 (3,455 to 4,000.5) | −0.008 (−0.181 to 0.164) |

| Greece | 368.9 (338.2 to 400.7) | 28,456.2 (26,232.7 to 30,594.5) | 371.3 (340.5 to 402.4) | 24,966.8 (23,313.8 to 26,646.9) | 0.032 (−0.126 to 0.190) |

| United States of America | 336.6 (321.6 to 351.8) | 770,603.6 (739,275.2 to 803,066.4) | 336.6 (321.5 to 351.4) | 922,005.3 (886,551.2 to 959,007.8) | −0.016 (−0.181 to 0.148) |

| Australia | 323 (298.6 to 346.6) | 46,093.6 (42,943.5 to 49,254.1) | 323.1 (298.3 to 351) | 62,855.5 (58,635.6 to 67,324) | 0.007 (−0.196 to 0.211) |

| Canada | 316.4 (299.5 to 334.4) | 75,316.9 (71,379.9 to 79,412.5) | 316.4 (299.5 to 334.5) | 95,750.1 (90,789.3 to 100,573.4) | 0.000 (−0.166 to 0.166) |

| Greenland | 315.3 (298.5 to 333.4) | 171.5 (161.9 to 181.6) | 315.7 (298.9 to 334.1) | 157 (148.7 to 165.6) | 0.001 (−0.165 to 0.167) |

| Brazil | 301 (286.2 to 315.8) | 477,939 (451,199.4 to 503,836.2) | 301.2 (286.2 to 316.2) | 576,541.4 (550,985.2 to 603,056.4) | −0.003 (−0.165 to 0.160) |

UI, Uncertainty interval.

The countries or territories with ASIR in 2021 more than 300/100,000.

Fig 1.

The global incidence of AD in 204 countries and territories. A, ASIR in 2021. B, EAPC in ASIR from 1990 to 2021.

Fig 2.

The change in the incidence of AD across different age groups, sexes, and SDI regions from 1990 to 2021. A, Change in ASIR by SDI. B, EAPC of ASIR by SDI. C, Change in ASIR by sex. D, EAPC of ASIR by sex.

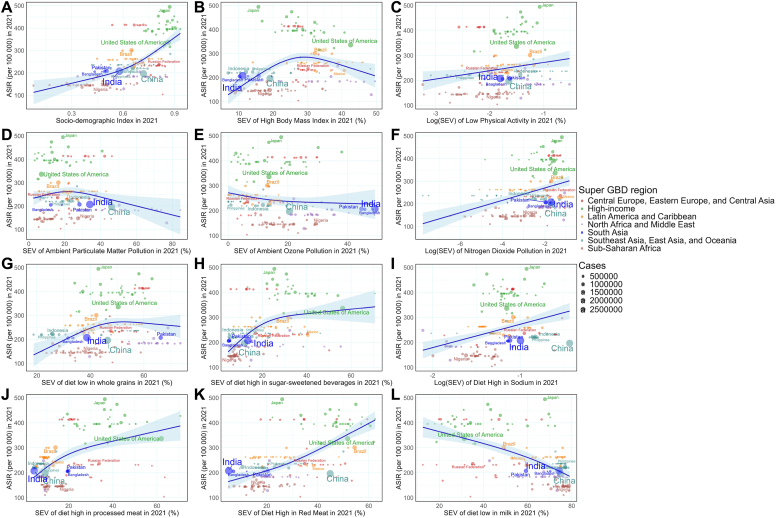

To understand the reason of the uneven distribution, we examined the relationship between SDI and ASIR. In 2021, SDI was significantly positively correlated with AD incidence (Fig 3, A), aligning with the observed results: countries with higher SDI levels exhibited a higher risk of AD. This is consistent with previous research findings.7 To explore the driving factors, we examined the relationship between ASIR and the SEVs of various modifiable risk factors, including air pollution, unhealthy lifestyles, and diets in 2021.

Fig 3.

Association between the SDI, unhealthy lifestyle, and air pollution and the ASIR of AD at national level in 2021. A, SDI. B, SEV of high body mass index. C, SEV of low physical activity. D, SEV of ambient particulate matter pollution. E, SEV of ambient ozone pollution. F, SEV of nitrogen dioxide pollution. G, SEV of diet low in whole grains. H, SEV of diet high in sugar-sweetened beverages. I, SEV of diet high in sodium. J, SEV of diet high in processed meat. K, SEV of diet high in red meat. L, SEV of diet low in milk.

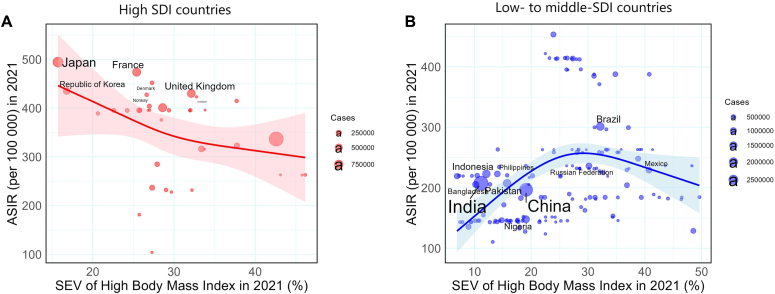

The SEV of high body mass index demonstrated a strong positive association with ASIR (Fig 3, B), highlighting the climbing role of obesity-driven systemic inflammation in AD pathogenesis. When countries were categorized into high-SDI and low- to middle-SDI groups, the positive association between body mass index and incidence was observed in low- to middle-income countries (Fig 4). Low physical activity was also positively associated with AD risk (Fig 3, C), indicating the adverse effects of sedentary lifestyles. Among environmental factors, nitrogen dioxide pollution exhibited a positive association with AD incidence (Fig 3, F), suggesting its role as a potent trigger for skin inflammation. Particulate matter pollution showed a weaker association (Fig 3, D), whereas ozone pollution showed no significant association (Fig 3, E). Dietary habits further influenced AD incidence. High intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, processed meat, red meat, and sodium was positively associated with ASIR, whereas low intake of whole grains contributed to a higher risk. Interestingly, low milk consumption showed a negative association, possibly reflecting its role as a common allergen in patients with AD (Fig 3, G-L).

Fig 4.

Association between the SEV of high body mass index and the ASIR of AD at national level in 2021. A, High-SDI countries. B, Low- to middle-SDI countries.

This study found high-SDI regions experiencing the greatest burden. The positive association between SDI and ASIR underscored the impact of urbanization and industrialization on AD risk. We integrated factors influencing ASIR from a global perspective for the first time. Modifiable factors such as obesity, pollution, and poor dietary habits play critical roles, suggesting opportunities for targeted interventions. It was reported that obesity has been associated with an increased incidence of AD in both children and adults,16,17 particularly occurring within the first 2 years of life and persistent obesity. Processed foods tend to be poorer nutritional quality, typically containing high levels of energy, salt, free sugars, and saturated fats, while being low in dietary fiber and essential vitamins.18 The beneficial effects of whole grains are primarily attributed to fiber, B vitamins, vitamin E, and other advantageous compounds found in wheat bran.19 Airborne pollutants have detrimental effects on skin barrier integrity and AD symptoms.20 Exposure to these unhealthy lifestyles and air pollution elevates systemic inflammation, potentially exacerbating chronic inflammatory diseases such as AD.21, 22, 23 These factors are closely linked to industrialization and urbanization, particularly in high-income and rapidly developing countries, suggesting that the adoption of a “westernized” lifestyle may contribute to AD onset.24 This also explains the high EAPC observed in the middle-high-SDI region, where a “risk accumulation” phenomenon emerges from facing both modern and traditional risk challenges, particularly in countries such as India and China.

This study provides a global perspective on AD incidence and its influencing factors but has some limitations. First, the methodological constraints of GBD 2021 may have introduced bias, particularly in low-SDI countries with incomplete data, where estimates rely on modeling and neighboring country data. This reduces the accuracy in estimating the association between ASIR and factors related to industrialization. Second, inconsistent definitions of AD across countries may lead to diagnostic misclassification. Finally, because of data limitations, we were unable to explore the genetic factors of AD.

Global disparities in AD incidence trends are closely linked to socioeconomic development and modifiable risk factors, including obesity, air pollution, and unhealthy diets. Addressing these factors through targeted public health policies is essential to mitigating the global burden of AD, particularly in industrialized and rapidly developing regions.

Disclosure statement

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42477471) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2025JJ20084).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Contributor Information

Yi Xiao, Email: xiaoyixy@csu.edu.cn.

Juan Su, Email: sujuanderm@csu.edu.cn.

Minxue Shen, Email: shenmx1988@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Langan S.M., Irvine A.D., Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odhiambo J.A., Williams H.C., Clayton T.O., Robertson C.F., Asher M.I., ISAAC Phase Three Study Group Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251–1258.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbarot S., Auziere S., Gadkari A., Girolomoni G., Puig L., Simpson E.L., et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284–1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a strategic framework for integrated control and management of skin-related neglected tropical diseases. 2022. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/355448 Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Mehrmal S., Uppal P., Giesey R.L., Delost G.R. Identifying the prevalence and disability-adjusted life years of the most common dermatoses worldwide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:258–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dizon M.P., Yu A.M., Singh R.K., Wan J., Chren M.-M., Flohr C., et al. Systematic review of atopic dermatitis disease definition in studies using routinely collected health data. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1280–1287. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng C., Yu N., Ding Y., Shi Y. Epidemiological variations in global burden of atopic dermatitis: an analysis of trends from 1990 to 2019. Allergy. 2022;77:2843–2845. doi: 10.1111/all.15380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Z., Wu X., Yu S., Huynh M., Jena P.K., Nguyen M., et al. Short-term exposure to a Western diet induces psoriasiform dermatitis by promoting accumulation of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:1815–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S.K., Kim J.S., Seo H.-M. Exposure to air pollution and incidence of atopic dermatitis in the general population: a national population-based retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2133–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols H.B., de González A.B., Lacey J.V., Rosenberg P.S., Anderson W.F. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1564–1569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilaria P., Ersilia T., Nicoletta B., Federica T., Andrea V., Nevena S., et al. The role of the Western diet on atopic dermatitis: our experience and review of the current literature. Nutrients. 2023;15:3896. doi: 10.3390/nu15183896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg J.I., Song J., Pinto D., Yu S.H., Gilbert A.L., Dunlop D.D., et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with less physical activity in US adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1714–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn K. The role of air pollutants in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2162–2203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverberg J.I., Kleiman E., Lev-Tov H., Silverberg N.B., Durkin H.G., Joks R., et al. Association between obesity and atopic dermatitis in childhood: a case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1180–1186.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverberg J.I., Silverberg N.B., Lee-Wong M. Association between atopic dermatitis and obesity in adulthood. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:498–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juul F., Vaidean G., Parekh N. Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular diseases: potential mechanisms of action. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1673–1680. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slavin J. Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:129–134. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendricks A.J., Eichenfield L.F., Shi V.Y. The impact of airborne pollution on atopic dermatitis: a literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:16–23. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biazus Soares G., Mahmoud O., Yosipovitch G., Mochizuki H. The mind-skin connection: a narrative review exploring the link between inflammatory skin diseases and psychological stress. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:821–834. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christ A., Lauterbach M., Latz E. Western diet and the immune system: an inflammatory connection. Immunity. 2019;51:794–811. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandercappellen E.J., Koster A., Savelberg H.H.C.M., Eussen S.J.P.M., Dagnelie P.C., Schaper N.C., et al. Sedentary behaviour and physical activity are associated with biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and low-grade inflammation—relevance for (pre)diabetes: the Maastricht study. Diabetologia. 2022;65:777–789. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05651-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schram M.E., Tedja A.M., Spijker R., Bos J.D., Williams H.C., Spuls PhI. Is there a rural/urban gradient in the prevalence of eczema? A systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:964–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]