SUMMARY

Vitamin C (vitC) is essential for health and shows promise in treating diseases like cancer, yet its mechanisms remain elusive. Here we report that vitC directly modifies lysine residues to form “vitcyl-lysine” - a process termed vitcylation. Vitcylation occurs in a dose-, pH-, and sequence-dependent manner in both cell-free systems and living cells. Mechanistically, vitC vitcylates STAT1-K298, impairing its interaction with phosphatase TCPTP and preventing STAT1-Y701 dephosphorylation. This leads to enhanced STAT1-mediated IFN signaling in tumor cells, increased MHC/HLA class-I expression, and activation of anti-tumor immunity in vitro and in vivo. The discovery of vitcylation as a distinctive post-translational modification provides significant insights into vitC’s cellular function and therapeutic potential, opening avenues for understanding its biological effects and applications in disease treatment.

In brief

Vitamin C directly modifies lysine residues through vitcylation, regulating STAT1 signaling and enhancing anti-tumor immune responses by preventing STAT1 dephosphorylation.

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin C (vitC), essential for humans who lack synthetic capability, has both basic nutritional roles and potential therapeutic applications.1 While low doses prevent diseases like scurvy,2 high-dose vitC’s role in cancer treatment has long been debated.3 Recent pharmacokinetic insights have renewed interest in its clinical applications,4–8 though its anti-cancer mechanisms, including generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS),4–6,9–13,14–16 and TET enzyme-mediated DNA demethylation,17–21 are not fully understood.

Under physiological conditions, VitC exists primarily as the ascorbate anion (175 Da), with dehydroascorbic acid (DHA, 174 Da) as its oxidized form.22–24 While DHA can undergo further oxidation at low pH to produce diketogulonate (DKG),25 leading to protein modifications called ascorbylations in plants, food, and certain animal tissues,26–29 these processes differ from physiological vitC modifications.

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) are crucial for physiological regulation,30–33 typically involving chemical alterations of specific amino acid side chains.32 Common modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and glycosylation,34–36 with recent mass spectrometry advances revealing several novel PTMs.37–41 These modifications regulate protein function by affecting protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity, protein stability, subcellular localization, and signaling pathways.

In this study, we show that ascorbate anion directly modifies lysine residues in peptides and proteins under physiological conditions, a process we term “vitcylation”, distinct from DHA-induced ascorbylation. This modification occurs in a pH- and dose-dependent manner. We identify numerous vitcylated proteins and demonstrate that vitC vitcylates the signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1) at lysine-298 (K298) in cancer cells, increasing its phosphorylation and nuclear translocation by impairing its interaction with T-cell protein-tyrosine phosphatase (TCPTP).42,43 This leads to activation of STAT1-mediated interferon (IFN) response pathways both in vitro and in vivo. Our findings provide molecular insights into vitC’s role in protein modification and immune regulation, with important implications for therapeutic applications.

RESULTS

VitC directly modifies lysine to form vitcyl-lysine in cell-free systems in a pH- and dose-dependent manner

Previous studies have shown that anhydride intermediates and homocysteine thiolactone (HTL) can react with lysine in proteins to form specific modifications.44 For example, succinic anhydride forms succinyl-lysine (succinylation) (Figure S1A),44,45 while HTL forms homocysteinyl-lysine (Figure S1B).46 Both these compounds share a common reactive lactone structure that enables lysine modification. We observed that vitC contains a similar reactive lactone structure (Figure 1A) and hypothesized it could modify the ε-amine group of lysine residues in peptides and proteins through its lactone structure to form a modified lysine, designated “vitcyl-lysine” (Figure 1A). To test this hypothesis, we incubated synthetic lysine-containing peptides with vitC at physiological pH (pH 7.4).41 Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/TOF MS) analysis revealed a 175 Da mass shift (Figure 1B), confirming that ascorbate anion modifies lysine residues to form vitcyl-lysine (Figures 1A and S1C).

Figure 1. VitC modifies lysine residues of peptides to form vitcyl-lysine in cell-free systems.

(A) Proposed mechanism of lysine vitcylation formation by ascorbate anion. The reactive lactone bond on the ascorbate anion is circled.

(B) Representative results of vitC-induced vitcylation formation in vitro. Synthetic lysine-containing peptides (sequences of the peptides were listed on the left of the spectrum, ‘Ac-’ means the N terminus of the peptide is protected by an acetyl group, hereafter for MALDI-TOF/TOF MS detection unless otherwise indicated) were incubated with either a vehicle, 2 mM vitC, 2 mM 1–13C-vitC, 2 mM 2-13C-vitC or 2 mM 1,2-13C-vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS, with the m/z range of each spectrum displayed above the spectrum. The m/z values of unmodified peptides and modified peptides are listed.

(C) MS spectrum (upper) and MS/MS spectrum (lower) of the unmodified peptide, vitcylated peptide, 1-13C-vitcylated peptide, 2-13C-vitcylated peptide, and 1,2-13C-vitcylated peptide (Ac-VSSPKVLQRL) detected by HPLC MS/MS. Lysine-containing unmodified fragments, vitcylated fragments, 1-13C-vitcylated fragments, 2-13C-vitcylated fragments, and 1,2-13C-vitcylated fragments are marked with green, red, and blue colors, respectively. The b ion refers to the N-terminal parts of the peptide, and the y ion refers to the C-terminal parts of the peptide (hereafter for HPLC-MS/MS analysis).

(D) Synthetic arginine-containing peptides were incubated with either a vehicle or 2 mM vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Previous studies showed that at low pH (~2.0), DHA oxidizes to DKG, modifying proteins in plants and food products with a mass shift of 58–148 Da, termed “ascorbylations” (Figure S1D).26–29 To determine whether DHA can form the modification under physiological conditions, we incubated lysine-containing peptides with either ascorbate anion or DHA (2 mM, pH 7.4). Only ascorbate anion formed modifications (Figure S1E), leading us to term this modification “vitcylation” to distinguish it from DHA-induced ascorbylation.

To validate this finding, we used isotope-labeled vitC variants (1-13C, 2-13C, and 1, 2-13C) (Figure S1F). MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analyses showed corresponding mass shifts: 176 Da for single-labeled (1-13C or 2-13C) and 177 Da for double-labeled (1, 2-13C) (Figure 1B). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–MS and MS/MS analysis confirmed these specific mass shifts in vitcylated peptide fragments (Figures 1C, S1G, and S1H), verifying the specific incorporation of vitC into lysine residues.

To further validate this lysine-specific modification, we conducted several experiments. When we substituted lysine with arginine, alanine, or cysteine in our test peptides, vitcylation was abolished (Figures 1D, S2A, and S2B), confirming the modification’s specificity for lysine residues. Using peptides with unprotected N-termini and multiple lysine residues, we demonstrated that vitC can modify both the N-terminus and multiple lysine residues within a peptide (Figures S2C and S2D). Importantly, no stable byproducts other than vitcylation were detected when using 1-13C-vitC (Figure S2E). The modification occurred with similar efficiency in both amine-containing buffer (Tris) and non-amine-containing buffer (PBS) (Figure S2F), suggesting buffer composition does not significantly affect the process. Furthermore, the modification displayed sequence specificity, as not all lysine-containing peptides were modified (Figure S2G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that vitcylation is a selective, lysine-specific modification with partial sequence dependency.

To further characterize lysine vitcylation, we examined its dependency on vitC concentration and pH in our cell-free system. Using physiologically achievable vitC concentrations (0.1–10 mM),47,48 we found that vitcylation increased with concentration, showing an EC50 of approximately 2 mM (Figure S2H). Stoichiometry and quantitative analysis confirmed substantial vitcylation formation at physiological concentrations (Figure S2I). We also assessed the pH dependency across a range of pH (4.0–11.5) covering physiological subcellular compartments (pH 6.5 to 8.2).49–51 Using 2 mM vitC, we observed increased vitcylation from pH 7.0 to pH 9.5–10.0, followed by a decline at higher pH (Figure S2J). This pattern suggests that vitcylation may occur preferentially in certain cellular compartments or conditions.

Together, our data identify lysine vitcylation is a previously unknown modification by vitC in its ascorbate anion form. This modification occurs in our cell-free and enzyme-free systems in a manner dependent on vitC dose-, pH-, and peptide-sequence.

VitC modifies lysine in cellular proteins to form lysine-vitcylated proteins

We next investigated the stoichiometry and specificity of vitcylation on purified proteins using HPLC-MS/MS. Significant vitcylation was detected on purified GAPDH and SMC1A following vitC treatment (Figure S3A), demonstrating that this modification occurs on intact proteins. We further conducted vitcylation with a whole-cell protein mix, isolated and purified by acetone precipitation,52 at two different pH conditions: pH 7.2 and pH 8.0. Our results indicated that vitC induced more abundant lysine vitcylation at pH 8.0 compared to pH 7.2 (Figure S3B; Table S1), suggesting that cellular location or physiological state may influence the extent of vitcylation.

To determine whether vitC modifies cellular proteins in intact cells, we measured intracellular vitC concentrations and detected vitcylated proteins after vitC treatment. Intracellular vitC levels increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner in both human (Cal-51) and murine (E0771 and PP) cancer cell lines (Figure S3C). PP is a recently developed syngeneic mouse breast tumor model driven by the concurrent loss of PTEN and p53.53 Interestingly, even without vitC supplementation, cells cultured in standard medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) exhibited basal intracellular vitC levels of ~100 μM (Figure S3C), likely due to vitC present in the FBS.54,55 Indeed, while basal medium contains no vitC, medium supplemented with 10% FBS contains approximately 10 μM vitC. (Figure S3D). Supplementing medium with 10% FBS exhibit increased intracellular vitC levels from below 50 μM to approximately 100 μM or higher (Figure S3E), indicating effective vitC uptake from the culture medium.

We investigated protein vitcylation in human Cal-51 and mouse E0771 cells treated with 2 mM vitC. Mass spectrometry identified 553 and 1405 vitcylated proteins in Cal-51 and E0771 cells, respectively, with 89 shared between both cell lines (Figures 2A and S3F; Tables S2-S4). Vitcylation was specific to lysine residues, with rare occurrences at the N-terminus and none other nucleophilic amino acids (Tables S2 and S3), consistent with earlier cell-free experiments (Figures S2B and S2C). Higher vitC doses increased the number of vitcylated proteins and sites (Figure S3G). Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the vitcylated proteins are distributed across subcellular locations with potential roles in multiple cellular processes and signaling pathways (Figures 2B–2E and S3H-S3K). While enriched lysine vitcylation motifs were observed, consistent with sequence-specific vitcylation in synthetic peptides (Figure S2G), no strong consensus sequence for vitcylation was identified (Figure S3L).

Figure 2. VitC induces lysine vitcylation on cellular proteins.

(A) Summary of the numbers of vitcylated proteins and sites identified in Cal-51 (human) and E0771 (mouse) cells.

(B) Subcellular locations of lysine vitcylated proteins identified in E0771 cells. The locations are classified into nuclear, cytosol, plasma membrane, extracellular, mitochondrial, cytosol_nuclear, and other compartments.

(C) Top ten gene ontology molecular function enrichment categories for vitcylated proteins identified in E0771 cells.

(D) Top ten gene ontology biological process enrichment categories for vitcylated proteins identified in E0771 cells.

(E) Top ten KEGG-based enrichment categories of lysine vitcylated proteins identified in E0771 cells.

(F) Extracted ion chromatograms (left) and MS/MS spectra (right) from HPLC-MS/MS analysis of vitcylated peptides (mouse SMC1A, K129) derived from E0771 (cellular peptide), its in vitro generated counterpart (synthetic peptide), and their mixture.

(G) Extracted MS/MS spectra from HPLC-MS/MS analysis of 1-13C-vitcylated peptides and vitcylated peptides (mouse SMC1A, K129) derived from E0771 cells. Lysine-containing 1-13C-vitcylated fragments and vitcylated fragments are marked by red and blue colors, respectively.

(H) Intracellular levels of lysine vitcylation, acetylation and methylation were measured in PP, E0771, Cal-51, and MCF7 cells cultured in medium containing a vehicle or vitC for 12 hours (2 mM vitC for PP and E0771, 0.5 mM vitC for Cal-51 and MCF7). Protein levels in each sample were normalized by coomassie staining, hereafter for global vitcylation detection. The quantifications of WB and coomassie staining were normalized to the untreated samples and are listed below, hereafter for global vitcylation detection.

(I) Intracellular levels of lysine vitcylation, acetylation and methylation were measured in E0771 cells cultured in medium containing different concentrations of vitC for 12 hours.

(J) Intracellular levels of lysine vitcylation, acetylation and methylation were measured in E0771 cultured in medium containing a vehicle or 2 mM vitC for 12 hours under different pH conditions.

(K) Intracellular lysine vitcylation, acetylation, and methylation levels were measured in E0771 cells cultured in medium containing 2 mM vitC for the indicated times.

(L) Lysine vitcylation, acetylation, and methylation levels of cytosolic and mitochondrial proteins were measured from E0771 cultured in medium with a vehicle or 2 mM vitC for 12 hours.

(M) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with 2 mM of vitC in the presence of denatured cell lysate (99°C for 5 min to denature the cell lysate) or active cell lysate at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS. The relative vitcylation levels were quantified (right, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We next determined whether vitC-induced lysine modifications in cellular proteins match those observed in synthetic peptides from our cell-free system (Figure 1). HPLC–MS/MS analysis showed that vitcylated peptides from vitC treated cells co-eluted with and had similar MS/MS spectra to vitC treated synthetic peptides in the cell-free system (Figures 2F, S3M, and S3N). Using isotopic 1-13C-vitC followed by MS/MS analysis further confirmed lysine vitcylation in cellular proteins (Figures 2G, S3O, and S3P). These results demonstrate that vitC treatment induces lysine vitcylation in cellular proteins in a manner consistent with our cell-free studies.

To further validate cellular lysine vitcylation, we developed a specific polyclonal antibody against vitcyl-lysine, confirming its specificity through dot-blot and western blot (WB) analyses (Figures S3Q-S3S). WB analysis detected specific bands in vitC-treated cancer cell lysates, using methylation and acetylation as controls (Figures 2H and S3T). These bands are outcompeted by vitcylated peptides (Figure S3U), confirming lysine vitcylation in cells. Further WB analysis demonstrated that cellular lysine vitcylation levels respond to vitC in a dose-, time-, and pH-dependent manner (Figures 2I–2K). Cells cultured with 10% FBS showed higher intracellular vitC and vitcylation levels compared to serum-free conditions (Figure S3V). Due to the higher pH of the mitochondrial matrix (7.7–8.2) versus cytosol (7.0–7.4),56,57 mitochondrial proteins showed more abundant vitcylation than cytosolic proteins (Figure 2L). These results demonstrate that vitC, as ascorbate anion, can modifies lysine residues in proteins in both human and murine cells.

To investigate potential enzymatic regulation of vitcylation in cells, we compared vitcylation formation in active versus denatured cell lysates. Active lysates enhanced vitC-induced vitcylation, while denatured lysates did not (Figure 2M). This indicates that cellular enzymes may catalyze or promotes vitcylation, potentially explaining the substrate selectivity observed in cells.

STAT1 vitcylation enhanced STAT1 phosphorylation and activation

We next investigated the functional role of lysine vitcylation in cells. Expression analysis of 4,604 cancer- and immune-related genes in vitC-treated E0771 cells revealed upregulation of immune and inflammatory responses genes (Figure 3A; Table S5). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) confirmed that the top-ranked genes in vitC-treated cells were associated with IFNγ response, IFNα response, and inflammatory response pathways (Figures 3B, S4A, and S4B).

Figure 3. Vitcylation of STAT1 K298 regulates the phosphorylation and activation of STAT1.

(A and B) Top-ranked upregulated GO terms (A) and upregulated GSEA signatures (B) in E0771 cells treated with 1 mM vitC for 2 days (n = 2).

(C) Extracted ion chromatograms (left) and MS/MS spectra (right) from HPLC-MS/MS analysis of a vitcylated peptide (human STAT1, K298) derived from Cal-51 cells (cellular peptide), its in vitro generated counterpart (synthetic peptide) and their mixture.

(D) Extracted MS/MS spectra from HPLC-MS/MS analysis of vitcylated peptide (upper) and 1–13C-vitcylated peptide (lower) (human STAT1, K298) derived from Cal-51 cells. Lysine-containing vitcylated fragments and 1-13C-vitcylated fragments are marked by blue and red colors, respectively.

(E) STAT1 vitcylation levels were measured from STAT1-GFP expressing cells (Cal-51 and PP cells) cultured in different concentrations of vitC for 12 hours.

(F) pSTAT1 flow cytometric analysis of Cal-51, E0771, and PP cells cultured in different concentrations of vitC for 2 days (2 mM vitC for E0771 and PP, 0.5 mM vitC for Cal-51, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(G) WB analysis of pSTAT1 in PP and Cal-51 cells cultured in different concentrations of IFNγ for 15 min with or without vitC treatment for 2 days (2 mM vitC for PP, 0.5 mM vitC for Cal-51).

(H) Measurement of vitcylation levels of STAT1-WT and STAT1-K298R in PP-sgSTAT1_1 cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP, after being cultured in medium containing 2 mM vitC or control medium for 12 hours.

(I) Flow cytometric analysis of pSTAT1 in PP-sgSTAT1_1 cell re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP, cultured in varying concentrations of vitC for 2 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(J) Nuclear translocation of STAT1 in PP-sgSTAT1_1 cell re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP, STAT1-K298R-GFP or STAT1-Y701A-GFP treated with 2 mM vitC (2 days) or 100 ng/ml IFNγ (15 min) was assessed by immunofluorescence (scale bar, 30 μM). The quantifications of immunofluorescence intensity are listed below, hereafter for STAT1 nuclear translocation assay.

(K) GSEA signatures of IFNγ response and IFNα response in PP-sgSTAT1_1 cell re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP, STAT1-K298R-GFP or STAT1-Y701A-GFP treated with 2 mM vitC (2 days) or 100 ng/ml IFNγ (24 hours) (n = 2).

Since STAT1 activation drives IFN response programs,58 and our initial analysis revealed STAT1 lysine-298 (K298) vitcylation upon vitC treatment (Table S2), we focused on this modification. K298, a crucial regulatory site conserved in vertebrates (Figure S4C),59–61 is surface-exposed and accessible for vitcylation (Figure S4D). We investigated STAT1 vitcylation in vitC-treated human Cal-51 and mouse E0771 breast cancer cells. HPLC-MS/MS analysis showed that vitcylated STAT1 K298 peptides from cells co-eluted with and matched MS/MS spectra of vitC-treated synthetic peptides (Figures 3C and S4E). Using isotopic 1-13C-vitC confirmed K298 vitcylation in both human and mouse cells (Figures 3D and S4F), with quantification showing substantial modification at physiological vitC concentrations (Figure S4G).

We next explored whether STAT1 vitcylation affects cellular immunity and inflammatory responses. Since STAT1 tyrosine 701 phosphorylation (pSTAT1) is crucial for nuclear translocation and subsequent IFN responses,62,63 we investigated the relationship between STAT1 vitcylation and phosphorylation. Using GFP-tagged STAT1 (STAT1-GFP) pulldown with GFP-antibody followed by WB analysis with anti-vitcylation antibody, we found that vitC treatment increased both STAT1 vitcylation and phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner in Cal-51, E0771, and PP cells (Figures 3E, 3F, S4H and S4I). Notably, vitC did not induce vitcylation of STAT2 and STAT3 (Figures S4J and S4K), indicating specificity among different STAT family members.

VitC treatment increased pSTAT1 levels across various tumor cell lines but showed no effect in STAT1-deficient AGS cell line (Figure S4L),64 suggesting vitcylation as a common mechanism for STAT1 activation in tumors. VitC increased both basal pSTAT1 levels and IFNγ-induced pSTAT1 response, as shown by WB and flow cytometry (Figures 3G and S4M). Both STAT1 vitcylation and phosphorylation exhibited pH dependency (Figures S4N and S4O), consistent with findings in our cell-free system (Figure S2J).

Immunofluorescence studies confirmed that vitC treatment enhanced STAT1 nuclear translocation and increased pSTAT1 levels (Figures S4P-S4R). Further investigation revealed that vitcylation occurs on both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of STAT1, as shown by analysis of STAT1-WT, STAT1-Y701A, and STAT1-Y701E (Figures S4S and S4T). We also found that vitC treatment promoted STAT1 ubiquitination and accelerated its degradation (Figures S4U and S4V), suggesting a dual role: while vitcylation enhances STAT1 phosphorylation and activation, it also promotes STAT1 degradation to prevent hyperactivation. This regulation indicates how vitC-induced STAT1 vitcylation coordinates phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and protein turnover to achieve nuanced control of STAT1 activity and IFN response.

To further study STAT1 vitcylation’s role in phosphorylation and activation, we generated STAT1-null PP tumor cells using CRISPR/Cas9 (Figure S4W). We then reintroduced STAT1-WT, vitcylation-defective STAT1-K298R, or phosphorylation-detective STAT1-Y701A (Figure S4X). Only STAT1-WT, not STAT1-K298R, restored STAT1 vitcylation and enhanced phosphorylation upon vitC treatment in STAT1-null cells (Figures 3H, 3I, and S4Y). Both the STAT1-K298R and STAT1-Y701A mutations prevented vitC-induced STAT1 nuclear translocation (Figure 3J). RNA-seq analysis further confirmed these mutations abolished vitC-triggered IFN response gene transcription, though STAT1-K298R mutation did not affect IFNγ-induced responses (Figure 3K). These results demonstrate that STAT1 vitcylation activates STAT1 in tumor cells by modulating its phosphorylation, with K298 playing a crucial role in vitC-mediated STAT1 activation.

STAT1 vitcylation prevents STAT1 from dephosphorylation by its phosphatase TCPTP

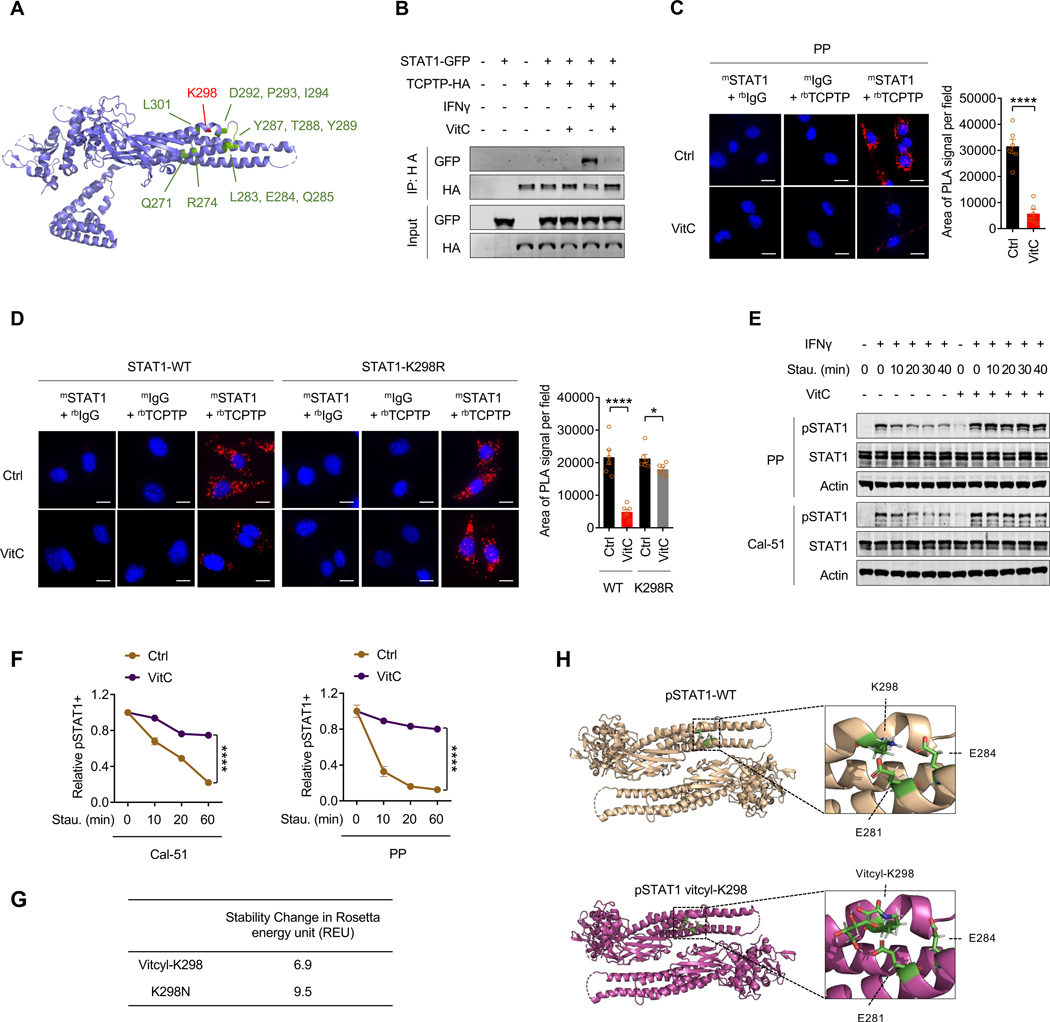

We investigated the molecular mechanism linking STAT1 phosphorylation and vitcylation. Previous studies identified STAT1 gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), an autoimmune disorder.65 This GOF mechanism involves impaired STAT1 dephosphorylation leading to Y701 hyperphosphorylation in response to interferons.65,66 Interestingly, one such mutation is K298N, which results in elevated pSTAT1 levels both in basal conditions and after IFNγ stimulation.59 Many STAT1 GOF mutations cluster near K298 in the protein structure (Figure 4A), suggesting a mechanistic link between K298 modification and STAT1 phosphorylation regulation.

Figure 4. Vitcylation of STAT1 K298 prevents its dephosphorylation by TCPTP.

(A) Ribbon representation of human STAT1. The K298 site and several gain-of-function mutation sites are marked by red and green colors, respectively. The side chain of K298 is shown.

(B) HeLa cells co-expressing STAT1-GFP and TCPTP-HA were treated with vehicle or 300 μM vitC for 24 hours, followed by stimulation with 100 ng/ml IFNγ for 15 min. The interaction between STAT1 and TCPTP was assayed by co-immunoprecipitation.

(C) STAT1-TCPTP PLA analysis (left) and quantification (right) of PP cells treated with a vehicle or 2 mM vitC for 2 days (scale bar, 30 μM). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(D) STAT1-TCPTP PLA analysis (left) and quantification (right) of PP-sgSTAT1_1 cell re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP and STAT1-K298R-GFP treated with vehicle or 2 mM vitC for 24 hours (scale bar, 15 μM). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

(E) Cells were pretreated with vehicle or vitC (0.2 mM vitC for Cal-51, 1 mM vitC for PP) for 2 days, then stimulated with 100 ng/ml IFNγ for 15 min followed by incubation with 1 μM staurosporine for the indicated times. The pSTAT1 levels were measured by WB immediately.

(F) Cells were pretreated with vehicle or vitC (0.2 mM vitC for Cal-51, 1 mM vitC for PP) for 2 days, then stimulated with 100 ng/ml IFNγ for 15 min followed by incubation with 1 μM staurosporine for the indicated times. The relative pSTAT1+ populations were measured by flow cytometry immediately (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(G) Stability changes in Rosetta energy unit (REU) of STAT1 caused by K298 vitcylation and K298N mutation as determined by the Rosetta atom energy function model system.

(H) Structures of wild-type and K298 vitcylated pSTAT1 in the antiparallel dimer conformation from the last snapshot of MD simulation. Vitcyl-K298 loses the salt bridges of K298/E281 and K298/E284 in STAT1.

See also Figure S5.

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that STAT1-K298 vitcylation might prevent STAT1 dephosphorylation by blocking phosphatase interaction. We investigated STAT1’s interaction with its phosphatase TCPTP through co-immunoprecipitation experiments, a well-documented association in previous studies.42,43,67 We found that vitC treatment disrupted the STAT1-TCPTP interaction (Figure 4B), while not affecting STAT1’s association with its kinase JAK1 (Figure S5A).58 Proximity ligation assay (PLA) confirmed vitC’s inhibitory effect on native STAT1-TCPTP interaction (Figures 4C and S5B), and this effect was impaired by the STAT1-K298R mutation (Figure 4D). In cells treated with vitC or a TCPTP inhibitor, STAT1 phosphorylation was sustained even after staurosporine treatment following IFNγ stimulation (Figures 4E, 4F, and S5C). This highlights how vitC regulates STAT1 phosphorylation by disrupting STAT1-TCPTP interaction. These results demonstrate that STAT1 vitcylation enhances STAT1 phosphorylation by preventing TCPTP-mediated dephosphorylation, establishing a mechanistic link between vitcylation and STAT1 activation.

Previous studies showed that IFNγ stimulation results in parallel pSTAT1 homodimers formation and recruitment to gamma interferon activation sites (GAS DNA elements), key events in the IFN signaling pathway.68–70 Recent research revealed that pSTAT1 dimers must rapidly rearrange from parallel to antiparallel conformation to bind TCPTP.71–73 Using Rosetta biomolecular modeling to analyze how STAT1-K298 modifications affect this conformational change, we found that both K298 vitcylation and K298N significantly destabilize the antiparallel dimer form of STAT1, with Rosetta energy unit (REU) changes of 6.9 and 9.5 respectively (Figure 4G). Further analysis of energy terms showed that both modifications disrupt salt bonds between K298 and E281/E284 in the antiparallel dimer conformation (Figures 4H, S5E, and S5F). Together, these data suggest that both STAT1-vitcyl-K298 and STAT1-K298N disrupt the structural transition of STAT1 between parallel dimers (required for DNA binding) and antiparallel dimer conformation (necessary for TCPTP-mediated dephosphorylation), favoring the parallel configuration and resulting in increased STAT1 phosphorylation. Intriguingly, while STAT1-K298N is a GOF genetic mutation and STAT1-K298-vitcylation is a chemical modification by vitC, they share a common molecular mechanism for enhancing immune response.

STAT1 vitcylation enhances MHC/HLA class I expression and immunogenicity of tumor cells

Since STAT1 phosphorylation and activation lead to IFN-mediated antigen processing and presentation in cells,74 we analyzed related gene expression using RT-qPCR and assessed major histocompatibility complex (MHC/HLA) class I expression by flow cytometry. VitC treatment upregulated multiple antigen processing and presentation genes in both PP cells (Tap1, Lmp2, H2k1, B2m and Irf1) and Cal-51 cells (HLA-B, TAP1, TAP2, LMP2 and B2M) (Figures 5A and S6A). Additionally, vitC enhanced MHC/HLA class I expression across various cancer cell lines, but not in the STAT1 deficient AGS cells (Figures 5B and S6B-S6D), and augmented IFNγ-induced MHC/HLA class I expression (Figures 5C and S6E). Consistent with the pH-dependent pattern of vitcylation and pSTAT1 (Figures S2J, S4N, and S4O), MHC/HLA class I expression also showed pH-dependent pattern (Figures 5D and S6F). Moreover, STAT1 knockout eliminated vitC-induced MHC/HLA class I expression, which was rescued by STAT1-WT but not the STAT1-K298R mutant (Figures 5E and S6G). These results suggest that STAT1 vitcylation contributes to STAT1 activation and MHC/HLA class I upregulation, revealing vitcylation’s role in modulating antigen processing and presentation pathways.

Figure 5. Vitcylation of STAT1 K298 enhances the expression of MHC/HLA class I and promotes immunogenicity in tumor cells.

(A) Quantitative PCR analysis of antigen processing and presentation gene expression in PP cells (n = 3) treated with either vehicle or 2 mM vitC for 2 days. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(B) Representative flow cytometry plots (left) and quantifications (right) of MHC-I expression on PP cells cultured in varying concentrations of vitC for 2 days (n=3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(C) Flow cytometric analysis of MHC-I expression on PP cells cultured in varying concentrations of IFNγ (100 ng/ml, 24 hours) with or without 2 mM vitC for 2 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(D) Flow cytometric analysis of MHC-I expression on PP cells cultured in different pH mediums with or without 2 mM vitC for 2 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

(E) Flow cytometric analysis of MHC-I expression on PP-sgSTAT1_1 cell overexpressing with STAT1-WT-GFP (2 single clones) or STAT1-K298R-GFP (2 single clones) cultured in varying concentrations of vitC for 2 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(F) Workflow for co-culturing of vitC-treated PP cells with bone marrow-derived DCs.

(G) Flow cytometry analysis of DCs co-cultured with vitC-pretreated PP cells. DCs (CD45+ CD11c+) were plotted, and quantifications of MHC II+, CD86+ and CD80+ were used to identify DC activity (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(H) Flow cytometric analysis of H-2Kb and pSTAT1 expression on B16-OVA cells treated with varying doses of vitC for 3 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(I) Workflow for co-culturing of vitC-treated B16-OVA or EL4-OVA cells with OT-I mice spleen-derived CD8+ T cells.

(J) Flow cytometric analysis of OT-I CD8+ T cells co-cultured with B16-OVA cells pretreated with 2 mM vitC. T cells (CD45+ CD3+ CD8+) proliferation and activity were quantified as CFSE− and IFNγ+, TNFα+ cells, respectively (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(K) Flow cytometric analysis of pSTAT1 in B16-OVA-sgSTAT1 cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP treated with vitC for 3 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

(L) Flow cytometric analysis of MHC-I expression on B16-OVA-sgSTAT1 cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP treated with vitC for 3 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(M) Flow cytometric analysis of H-2Kb binding SIINFEKL peptide on B16-OVA-sgSTAT1 cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP treated with vitC for 3 days (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(N) Flow cytometric analysis of OT-I CD8+ T cells co-cultured with B16-OVA-sgSTAT1 cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP pretreated with 2 mM vitC. T cells (CD45+ CD3+ CD8+) activity were quantified (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S6.

Previous studies showed that vitC functions through modulating ROS levels and acting as a cofactor for ten-eleven translocation enzymes (TETs) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1α) prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs).4,11,33,75–79 To assess whether these mechanisms contribute to increased MHC/HLA class I expression, we measured ROS levels alongside MHC/HLA class I expression at various vitC concentrations. While high-dose vitC (2 mM) increased ROS levels, lower doses (0.1 to 1 mM) reduced ROS levels (Figure S6H), consistent with vitC’s dual antioxidative/pro-oxidative properties.80–82 However, MHC/HLA class I expression increased linearly with vitC concentration (Figure S6H), suggesting that ROS modulation is not the primary mechanism for this effect. To determine the potential role of TET or PHD enzymes, we used specific inhibitors Bobcat 339 for TET and IOX2 PHD.83,84 While these inhibitors effectively reduced TET activity and increased HIF1α levels, respectively (Figures S6I and S6J), they didn’t affect vitC-induced increase in pSTAT1 and MHC/HLA class I expression (Figure S6K). These results suggest that the vitC’s effects on STAT1 phosphorylation and MHC/HLA class I expression occur independently of ROS, TET or PHD pathways, supporting a more direct mechanism through STAT1 vitcylation.

We next investigated vitC’s impact on tumor-immune cells interactions through co-cultured experiments (Figure 5F). When vitC-pretreated PP cells were co-cultured with dendritic cells (DCs) derived from naïve syngeneic FVB mice, we observed DC activation through increased MHC class II (MHC II) and co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and CD80 (Figures 5G and S6L).85,86 To further examine functional consequences of vitC-induced MHC/HLA class I expression, we employed ovalbumin (OVA)-expressing mouse tumor cell lines, B16-OVA and EL4-OVA.74 VitC treatment increased pSTAT1 and MHC-I expression in these cells (Figures 5H and S6M). co-culture of vitC-pretreated B16-OVA or EL4-OVA cells with MHC-I-restricted OVA-specific CD8+ T cells harvested from OT-I mice (Figure 5I) showed increased CD8+ T cell proliferation and anti-tumor cytokines production, including IFNγ and tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (Figures 5J and S6N-S6P).74 Importantly, STAT1-K298R mutation in B16-OVA cells eliminated vitC-induced effects: STAT1 phosphorylation (Figures 5K and S6Q), MHC-I expression (Figure 5L), OVA peptide presentation (Figure 5M), and OT-I CD8+ T cells activation in the co-coculture system (Figure 5N). This suggests that vitC triggers tumor cell immunogenicity through STAT1 vitcylation.

To validate that STAT1 vitcylation induces tumor cell immunogenicity independently of TET2 and HIF1α, we generated TET2 and HIF1α knockout (KO) B16-OVA cells (Figure S6R). Neither TET2-KO nor HIF1α-KO significantly affected vitC-induced changes in pSTAT1 levels (Figure S6S), OVA peptide presentation (Figure S6T), and MHC-I expression (Figure S6U). TET2-KO also did not impact MHC-I-related gene transcription (Figure S6V). Furthermore, in co-culture experiments with OT-I derived CD8+ T cells, neither TET2-KO nor HIF1α-KO significantly affected vitC-induced T cell activation (Figure S6W). These results suggest that vitC regulates STAT1 activity and tumor cell immunogenicity independent of TET2 and HIF1α pathways. Together, these results demonstrate that STAT1 vitcylation enhances tumor cell immunogenicity and immune cell activation through a pathway distinct from vitC’s known mechanisms.

STAT1 vitcylation triggers anti-tumor immunity in vivo

We next investigated vitC’s on tumors and tumor immune microenvironment in vivo using mice bearing mouse E0771 tumor transplants treated with vitC via intraperitoneal injection (4g/kg/day). VitC treatment suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival in immunocompetent syngeneic mice (Figures 6A–6C), but not in immunocompromised mice (Figures 6D and 6E). VitC induced vitcylation in both tumor cells and immune cells within the tumor microenvironment (Figures 6F and S7A), with minimal effects on splenic immune cells (Figure S7B).

Figure 6. VitC induces vitcylation in tumor cells in vivo with increased STAT1-mediated immune responses.

(A) Workflow for monitoring tumor growth, as well as analyzing vitcylation levels and immune cell infiltration in tumors in vivo. Tumor cells were injected into the mammary fat pads of syngeneic female mice. Tumor-bearing mice were administered vitC (i.p. 4 g/kg/day) when tumor volume reached approximately 300 mm3. Following treatment, tumor growth and survival were monitored, and tumor tissues were harvested for analysis.

(B and C) Tumor growth (B) and survival (C) of E0771 allografts in C57BL/6 mice treated with vitC were analyzed (vehicle, n = 5; vitC treated, n = 5).

(D and E) Tumor growth (D) and survival (E) of E0771 allografts in NSG mice treated with vitC were analyzed, and results were compared between the vehicle group and the vitC-treated group (vehicle, n = 5; vitC treated, n = 5).

(F) Lysine vitcylation, acetylation, and methylation levels of tumor cells (CD45−) in E0771 tumors were measured by WB (n = 4 for each group). Protein levels were normalized by Coomassie staining.

(G and H) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1 (G) and MHC-I expression (H) on E0771 tumor cells (CD45−) from vehicle- or vitC-treated mice (vehicle, n = 10; vitC treated, n = 10). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

(I) Top-ranked upregulated GSEA signatures in the tumor tissue of vitC-treated E0771 tumor-bearing mice at 7 days (n = 2).

(J) STAT1-TCPTP PLA analysis (left) and quantification (right) were performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedding (FFPE) preparations of E0771 tumor tissues (scale bar, 20 μM).

(K) Gene signatures associated with immune cells (CD45+) in E0771 tumors that were enriched following vitC treatment were analyzed by NanoString.

(L) Flow cytometry analysis of the pSTAT1 level, MHC II and CD86 expression in DCs in E0771 tumor tissue from vehicle- or vitC-treated mice (vehicle, n = 9; vitC treated, n = 9). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(M and N) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1 level, TNFα and IFNγ expression in CD4+ T cells (M) and CD8+ T cells (N) in E0771 tumor tissue from vehicle- or vitC-treated mice (vehicle, n = 9; vitC treated, n = 9). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(O) VitC concentrations were analyzed in the plasma, tumor tissue, and spleen of vehicle- or vitC-treated E0771 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice (vehicle, n = 3; vitC treated, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001.

Consistent with in vitro findings, vitC treatment increased pSTAT1 (Figure 6G), MHC-I expression (Figure 6H), and IFN responses (Figure 6I; Table S6), while impairing STAT1-TCPTP interaction in tumor cells (Figure 6J). NanoString analysis revealed enhanced antigen processing gene expression in immune cells (Figure 6K). VitC treatment significantly activated tumor-infiltrating DCs and T cells (Figures 6L–6N, S7C and S7D), but had minimal effects on immune cells in spleen and lymph nodes (Figures S7E-S7L). Notably, high-doses vitC administration accumulated significantly in tumor tissues and plasma, but remained relatively low in spleen (Figure 6O), consistent with previous reports.87–90 This suggests selective tumor uptake of vitC enhances anti-tumor immunity without systemic immune activation. Similar results were observed in PP tumor-bearing syngeneic mice treated with vitC (Figures S7M-S7S).

To validate the importance of STAT1 vitcylation and phosphorylation in vitC-triggered anti-tumor immunity, we performed in vivo experiments utilizing tumor cells harboring the STAT1-K298R or STAT1-Y701A mutations. Both mutations abolished vitC-induced tumor growth suppression (Figure S7T) and impaired pSTAT1 and MHC-I expression (Figures 7A and 7B). They also prevented the production of STAT1-targeted immunosuppressive molecules IDO1 and PD-L1 in tumor cells (Figure S7U) and blocked immune cell activation in the tumor microenvironment (Figures 7C, S7V, and S7W). These findings suggest that vitC’s anti-tumor effects require both STAT1 vitcylation at K298 and phosphorylation at Y701.

Figure 7. VitC modulates the immune milieu via STAT1 vitcylation (A and B) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1.

(A) and MHC-I expression (B) on the xenografts of PP-sgSTAT1_1 tumor cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP, STAT1-K298R-GFP, or STAT1-Y701A-GFP treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 9; vitC treated, n = 9). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(C) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1 level, TNFα and IFNγ expression in CD8+ T cells on the xenografts of PP-sgSTAT1_1 tumor cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP, STAT1-K298R-GFP or STAT1-Y701A-GFP treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 9; vitC treated, n = 9). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

(D) Workflow for analyzing tumor growth, pSTAT1, OVA peptide presentation, and immune cell infiltration in the xenografts of B16-OVA, B16-OVA (TET2-KO), and B16-OVA (HIF1α-KO) tumor cells treated with vehicle or vitC in vivo.

(E and F) Tumor growth (E) and survival (F) of the xenografts of B16-OVA, B16-OVA (TET2-KO), and B16-OVA (HIF1α-KO) tumor cells treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 5; vitC treated, n = 5).

(G) Tumor growth of the xenografts of B16-OVA (STAT1-WT) and B16-OVA (STAT1-K298R) tumor cells treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 5; vitC treated, n = 5). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

(H) Survival of the xenografts of B16-OVA (STAT1-WT) and B16-OVA (STAT1-K298R) tumor cells treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 5; vitC treated, n = 5). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

(I and J) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1 (I) and OVA peptide presentation (J) on the xenografts of B16-OVA (STAT1-WT) and B16-OVA (STAT1-K298R) tumor cells treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 6; vitC treated, n = 6). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(K) Flow cytometry analysis of TNFα and IFNγ expression in OT1 CD8+ T cells on the xenografts of B16-OVA-sgSTAT1 tumor cells re-expressing STAT1-WT-GFP or STAT1-K298R-GFP treated with vehicle or vitC (vehicle, n = 6; vitC treated, n = 6). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01.

(L) Tumor growth of E0771 allografts in C57BL/6 mice treated with vitC as a single agent or in combination with anti-PD1 antibody (n = 4). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

See also Figure S7.

To investigate whether vitC regulates STAT1 independently of TET2 or HIF1α in tumor suppression, we conducted in vivo experiments using TET2-KO and HIF1α-KO B16-OVA tumor cells (Figure 7D). Notably, neither TET2-KO nor HIF1α-KO negated vitC’s effects on tumor suppression (Figures 7E and 7F), pSTAT1 levels (Figure S7X), OVA peptide presentation (Figure S7Y), or immune cell activation in the tumor microenvironment (Figure S7Z). In contrast, STAT1-K298R mutation abolished all these vitC-induced effects (Figures 7G-7K). These results suggest that STAT1 vitcylation mediates anti-tumor effects through a pathway independent of TET2 or HIF1α.

Given vitC’s anti-tumor effects, we explored its potential to enhance immune checkpoint therapy. We treated E0771 tumor-bearing mice with vitC and anti-PD1, alone or in combination. The combination treatment more effectively suppressed tumor growth than either agent alone (Figures 7L and S7AA), suggesting that high-dose vitC can enhance immunotherapy responses.

In summary, our studies reveal that vitC-induced STAT1 vitcylation enhances STAT1 phosphorylation, leading to increased antigen processing and presentation in tumor cells. This, in turn, activates various immune cells, including DCs and T cells, in the tumor microenvironment, triggering STAT1-mediated anti-tumor immunity. These findings provide a mechanistic explanation for vitC’s role in enhancing anti-tumor immune responses and suggest promising therapeutic strategies combining vitC with immunotherapy.

DISCUSSION

The evolutionary loss of vitC synthesis in humans through L-gulonolactone oxidase gene (encoding the enzyme responsible for converting glucose to vitC) raises intriguing questions about high-dose vitC supplementation’s necessity and safety. However, this change does not necessarily imply that high vitC intake is harmful. The mutation amid complex evolutionary pressures and environmental factors, and humans may have retained the ability to benefit from varying dietary vitC levels. Evolution often produces adequate rather than perfect solutions for survival. While losing vitC synthesis ability may have been advantageous in the ancestral environment, this doesn’t preclude benefits from higher intake in our modern context, given the drastically different environmental and dietary conditions we face today. Therefore, while evolutionary history provides valuable context, it alone cannot determine the harm or benefit of high vitC intake. The effects of high-dose vitC supplementation should be evaluated based on current scientific evidence, considering modern human physiology and health challenges.

This study reveals that vitC directly modifies lysine residues in peptides and proteins through “vitcylation”, a process occurring across a broader pH range, peaking around pH 9–10. The pH and dose dependence suggest that high-dose vitC may offer distinct therapeutic effects compared to lower doses.

The discovery of lysine vitcylation opens new possibilities for biomarker development in various conditions. Analysis of specific vitcylated proteins and their modification patterns could reveal unique signatures associated with certain diseases or physiological states. These signatures could serve as diagnostic tools or biomarkers for monitoring treatment responses, particularly valuable in cancer where determining appropriate vitC dosage and monitoring treatment effects remain challenging.

Our understanding of STAT1 regulation has been enhanced by findings on K298 vitcylation. This modification destabilizes pSTAT1’s anti-parallel conformation, which is crucial for TCPTP binding and dephosphorylation. Consequently, this leads to elevated pSTAT1 levels and enhanced IFN-mediated immune responses. Interestingly, the disease-causing STAT1-K298N mutation in autoimmune conditions shares a similar molecular mechanism with STAT1-vitcyl-K298. However, their biological effects differ significantly: while K298N mutation causes chronic immune activation contributing to autoimmune disease, K298-vitcylation temporarily augments immune response in a manner that can be beneficial for combating pathological conditions, such as cancer and viral infections.

Our study addressed concerns about high-dose vitC’s systemic toxicity and physiological relevance. We observed that vitC accumulates preferentially in tumor tissues and plasma while maintaining relatively low in the spleen, suggesting a favorable pharmacokinetic profile for cancer treatment. These findings support the renewed interest in high-dose vitC as an anti-cancer agent. Clinical trials have demonstrated its safety and tolerability, showing promise both as a standalone treatment and in combination therapy.6,91,92 Moreover, vitC has shown benefit in mitigating chemotherapy side effects and improving quality of life for cancer patients, including those in palliative care.93,94

The identification of vitcylation as a distinctive PTM provides significant insights into vitC’s role in protein regulation and cellular function. This discovery expands our understanding of how protein modifications contribute to health and disease, while highlighting vitC’s importance as a regulatory molecule in the complex interplay between nutrients, cellular processes, and overall physiology. Further research will be crucial to fully elucidate the extent of vitcylation and its relevance in biological processes. This may lead to the discovery of new biomarkers and therapeutic targets, thereby deepening our understanding of vitC’s health benefits. These insights could fundamentally change our approach to nutritional biochemistry and medical treatment, offering new perspectives on the intersection of nutrition and health.

Limitations of the study

While we identify lysine vitcylation as a vitC-responsive modification, several aspects require further investigation. At the molecular and cellular level, we need to explore the pathological significance of diverse vitcylated proteins, understand the role of enhanced mitochondrial protein vitcylation and determine potential enzymatic regulation and substrate specificity mechanisms.

In terms of tumor and immune effects, single-cell sequencing analysis is needed to fully characterize vitC’s impact on different cell populations. Additional studies should examine vitC’s influence on tumor cell behavior (growth, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis) and antigen presentation in non-tumor cells, as well as the balance between local and systemic immune responses. Understanding these areas will be crucial for realizing the therapeutic potential of vitC-based therapeutic strategies in cancer and other diseases. Particularly important is determining how vitC’s targeting specificity influences its differential effects on tumor growth versus immune activation.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Jean J. Zhao (jean_zhao@dfci.harvard.edu)

Materials availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

Data and code availability

This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

STAR ★ METHODS

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

Cells were cultured under standard conditions in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cal-51, MCF7, E0771, PC-9, HCT116, and HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), verified to be negative for mycoplasma, and authenticated by short tandem repeat analysis using the Promega GenePrint 10 System. Cal-51, MCF7, PC-9, HCT116, and HeLa cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies) and PenStrep (Hyclone). E0771 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, PenStrep, and 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies, 15630080). B16-OVA and EL4-OVA cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 250 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). PP cells were derived from mouse mammary tumors and cultured in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 25 ng/ml hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml insulin, 8.5 ng/ml cholera toxin, 0.125 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 5 μM Y-27632 Rock1 inhibitor, and PenStrep, as previously described.95

Animals

All mouse experiments were conducted in compliance with federal laws and institutional guidelines, as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School. The relevant animal protocols limited the maximum tumor diameter to 25 mm, which was not exceeded in any experiment. CO2 inhalation was used to euthanize the mice. Female wild-type FVB and C57BL/6 mice, aged six-to-eight weeks, were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. For tumor formation assays, 5×105 PP cells or 105 E0771 cells were injected into the thorracic fat pad in 50% matrigel. VitC (Sigma-Aldrich, A4034) was prepared daily by resuspending the powder in PBS (Hyclone). Anti-mouse PD1 antibody (clone 332.8H3, kindly provided by Dr. Gordon Freeman at DFCI) was injected by intraperitoneal administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 3 days.96 Intraperitoneal administration of vitC was conducted at a dose of 4 g/kg, qd. Mice in the control group were treated with PBS.

METHOD DETAILS

In vitro vitcylation reaction

In vitro vitcylation reactions were conducted using a 30 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM sodium ascorbate (vitC), and 0.05 mg/ml synthetic substrate peptide. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 3 hours at 37°C. The peptide was then desalted by passing it through a C18 ZipTip (Millipore) and subjected to analysis using a MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (SCIEX-5800).

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis

The proteome of breast cancer cells was digested with sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega) overnight at the protease/protein ratio at 1:50. The resulting peptide mixture was desalted by C18, dried by vacuum centrifugation, and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. Peptides were resuspended in 5% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and analyzed by nanoLC/MS/MS using a NanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) interfaced to an Orbitrap Lumos mass spectrometer. Peptides were trapped on a self-packed precolumn (4 cm 7 μm Symmetry C18), separated on an analytical column (50 cm 5 μm Monitor C18) using an HPLC gradient (5–35% B in 90 minutes, A=0.1% formic acid, B=acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid), and introduced to the mass spectrometer by electrospray ionization. The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode and subjected the top 10 most abundant ions in each MS scan (120k resolution, m/z 300–2000, 800% AGC target) to MS/MS (7500 resolution, 35% NCE, m/z 100–2000). Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a 30-second duration. Raw MS files were converted to mgf and analyzed by Mascot version 2.6.1 using a forward/reverse database of human proteins (NCBI RefSeq). Search parameters included precursor and product ion tolerances of 10 ppm and 25 mmu, variable oxidation of methionine, vitcylation of lysine (+175.0237 Da), and fixed carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues.

Quantifications of targeted vitcylation peptides

A published method was employed.97 Briefly, a ratio of vitcylated peptide signal (the total ion counts (TIC) of vitcylated form) to the total peptide signal (TIC of vitcylated form + TIC of the non-vitcylated form) was calculated according to the following equation: TICvita./(TICvita.+TICnon-vita.)=Ratio of vitcylation.

Transcriptome methodology

An Ion AmpliSeq Custom Panel containing 4,604 cancer- and immune-associated genes (designed by Thermo Fisher using Ion AmpliSeq designer) was utilized for our studies, as previously described.74 For each sample, 10 ng total RNA was used to prepare the cDNA library. Libraries were multiplexed and amplified using an Ion OneTouch 2 System and sequenced on an Ion Torrent Proton system (Thermo Fisher). Count data was generated using Thermo Fisher’s Torrent suite and ampliSeqRNA analysis plugin. For Gene Ontology enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis, genes with a mean fold change (vitC treated vs control) greater than 2 or lesser than 0.5 were utilized. Gene Ontology enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis were carried out using Cytoscape Software and STRING plugin. For GSEA analysis, genes were first ranked according to log2(fold change) and then analyzed using the GSEAPreanked tool with MsigDB v7.1 Hallmarks gene sets and the ‘classic’ method.98

Bioinformatic analysis

The subcellular localization of vitcylated proteins was predicted using WoLF PSORT, a subcellular localization prediction program (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp ).99 Gene Ontology enrichment analysis for the vitcylated proteins was carried out using DAVID bioinformatics resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp ).100 KEGG pathway analysis was performed using KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/genelist/ ).101 For vitcylation motif analysis, the 10 amino acid residues (−10 to +10) on either side of the vitcylation site were selected and a consensus logo was generated using the WebLogo webserver (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi ).102

Flow cytometry

For tumor cell lines, one million cells were stained with the appropriate antibodies diluted in PBS (Hyclone) plus 2% FBS (Life Technologies) for 30 min on ice. For tumor samples, tumors were mechanically disrupted by chopping and chemically digested in dissociation buffer (2 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical), 0.02 mg/ml DNase (Sigma Aldrich) in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 5% FBS (Life Technologies), PenStrep (Hyclone) with agitation at 37°C for 45 min. After lysing of red blood cells (BD Biosciences), single-cell suspensions were incubated with appropriate antibodies for 30 min on ice.

For human antibodies, antibodies were purchased from BioLegend unless otherwise indicated: pSTAT1(Y701) (clone A17012A), HLA (clone W6/32), B2M (clone A17082A). Mouse antibodies: pSTAT1(Y701) (Cell Signaling Technology, 8062S), H-2Kq (clone KH114), H-2Kb (clone 28–8-6), B2M (clone A16041A), CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD3 (clone 145–2C11), CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD8 (clone HIT8a), IFNγ (clone XMG12), TNFα (clone MP6-XT22), CD11c (clone N418), CD86 (clone GL-1), CD80 (clone 16–10A1), MHC II (clone M5/114.15.2), CD103 (clone 2E7), H-2Kb binding SIINFEKL (clone 25-D1.16), I-A/I-E (MHC II, clone M5/114.15.2), CD206 (clone C068C2), CD11b (clone M1/70). Anti-mouse/rat FoxP3 staining set (eBioscience) was used for intracellular staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For IFNγ and TNFα analysis, cells were stimulated in vitro with the Leukocyte Activation Cocktail with protein transport inhibitor Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences, 550583).

Western blots

Western blotting was performed as previously described,74 using the following antibodies: anti-vitcylation antibody (generated by Abclonal Technology) and Cell Signaling Technology antibodies to pSTAT1 (9167S), STAT1 (14994S), GAPDH (5174S), ACTIN (4967S), GFP (2955S), HA (2367S), lysine acetylation (9441S), lysine methylation (14679S) and COX4 (4850S).

Dot-blot assays

Peptides were spotted on nitrocellulose membranes. After the membrane dried, the membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBST for 1 hour, followed by the incubation with the anti-vitcylation antibody overnight at 4°C and the secondary antibody overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with TBST, the membrane was scanned by Odyssey Dlx Imaging System (LI-COR).

Thermostability change calculation

The antiparallel dimer structure from PDB 1YVL (Asymmetric Unit) is initially considered with 3.00Å X-ray resolution. The whole calculation includes several steps as below:

1. The input structure preparation

The wild type K298, the mutation K298N and the vitcyl-K298 (in two chains) were relaxed with Cartesian coordination type and constraints.103–105 The option/flag was set as follows.

-nstruct 200

-ex1

-ex2

-relax:constrain_relax_to_start_coords

-ramp_constraints true

-use_input_sc

-flip_HNQ

-no_optH false

-relax:cartesian

-beta_nov16_cart

-corrections::beta_nov16

-crystal_refine

-in:auto_setup_metals

-extra_res PTM.params

The structures with the lowest scores were used in the next step.

2. The preparation of params and rotlib files

To make the vitcyl-K298 recognized by Rosetta, the params and rotlib files were generated by related modules using Lysine as reference.106,107

3. MD sampling

The side chain of vitcyl-K298 has more than 10 chi angles, which is beyond the recommended limitation of Rosetta. To better find the low energy conformations of vitcyl-K298, we adopted molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to perform the sampling. Ff14SB was used to parameterize the protein.108 The vitcyl-K298 was parameterized using GAFF and its partial charge was parameterized using RESP.109,110

10ns MD simulations were performed using Amber20 and 100 frames of snapshots were extracted from the last 5ns scoring using Rosetta. A 100kcal/mol positional restraints were given on residues 9 Å away from α-carbon of K298 to minimize the noise arose from the thermal fluctuation during the MD simulations.

4. Scoring and ddG calculation

The score_jd2 module was used with the following options.111,112

-beta_nov16_cart

-corrections::beta_nov16

-fa_max_dis 9.0

-extra_res VLY.params

Average scores for K298, N298 and vitcyl-K298 were calculated on the 100 frames of snapshots.

Values of ddG were calculated from the difference as:

ddG = Score avg(Mut/Mod) – Score ave(WT)

Cellular levels of vitC, ROS, and TET activity assay

Cellular vitC assay kit (Cayman, 700420), ROS/superoxide detection assay kit (abcam, ab139476), and epigenase 5mC-hydroxylase TET activity/inhibition assay kit (Epigentek, P-3086–48) were used for cellular vitC level assay, ROS level assay, and TET activity assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions, respectively.

Preparation of pan-specific anti-vitcyllysine polyclonal antibody

The pan-vitcyllysine antibody was generated using a synthetic vitcylated lysine-containing peptide mix, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyain (KLH) as an antigen. The sequence of the peptide mix is CXXXXXK*XXXX, where X represents any of the 20 standard amino acids, excluding cysteine; A cysteine residue was added to the peptide’s N terminus to facilitate conjugation with KLH. This conjugation reaction was carried out in 0.2% glutaraldehyde solution. The resulting vitcylated KLH was subjected to immunize rabbits. The population of the pan-specific antibodies recognizing vitcylated lysine was then purified using the vitcylated lysine-containing peptide mix. The specificity of the antibodies was evaluated using dot blots.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

PLA was performed using the Duolink In Situ Red Starter Kit Mouse/Rabbit (Sigma, DUO92101) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All reagents used for the procedure are from this kit, except the antibody for STAT1 (Santa Cruz, SC-464) and TCPTP (abcam, ab227916).

Measurement of in vivo vitC concentrations by HPLC-MS

VitC concentrations in vivo were measured by HPLC-MS as previously described.14 Briefly, excised tumors and spleens were placed in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes with 1 mL of 3 mM monobrombimane (MBB) in CH3OH:H2O (80:20) at 4°C and incubated for 3 h. After this, tissues were disrupted using stainless steel beads in a TissueLyser (Qiagen) and incubated for another 30 minutes at −20°C. Extracts were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm to pellet insoluble material, and supernatants were transferred to clean tubes. This extraction was repeated twice more, and all three supernatants were dried in a speed-vac (Savant) and stored at −80°C until analysis. Plasma samples were incubated with 2.5 mM MBB in CH3OH:H2O (80:20) at room temperature for 30 min, then diluted with CH3CN:H2O (70:30) containing 0.025% formic acid. The samples were vortexed, centrifuged for 20 minutes at 20,000g, and the supernatants transferred to autosampler vials for LC/MS analysis. For absolute vitC concentrations, MBB-treated plasma was diluted with 70% CH3CN containing 0.025% formic acid, and 1 μL was injected for LC/MS.

Q-TOF LC/MS analysis was conducted as referenced,113 detecting ascorbic acid in negative mode ([M-H]− at m/z 175.0248) and positive mode ([M+H]⁺ at m/z 177.0394) with retention times of 1.92 minutes and 0.99 minutes for ANP and RP columns, respectively. A vitC calibration curve was established for plasma, tumor lysate, and spleen lysate in the 0–600 μM range. Accuracy and precision were evaluated using spiked vitC standards in these samples. Intracellular vitC concentrations in tumor and spleen samples were calculated as nM/mg protein and converted to mM, assuming 1 g of protein equals 1 mL in volume.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was performed as previously described.114 Primer sequences used for RT-PCR were as follows. Tap1 (mouse) forward: 5’- GGACTTGCCTTGTTCCGAGAG-3’; reverse: 5’- GCTGCCACATAACTGATAGCGA-3’. Lmp2 (mouse) forward: 5’- ATGTGGTACTCAATTCACAAGCA-3’; reverse: 5’-AAGCAAGGATGGTTCCTGGAG-3’. B2m (mouse) forward: 5’-TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA-3’; reverse: 5’- CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC-3’. Irf1 (mouse) forward: 5’- GTTGTGCCATGAACTCCCTG-3’; reverse: 5’-GTGTCCGGGCTAACATCTCC-3’. H2k1 (mouse) forward: 5’- CAGGTGGAGCCCGAGTATTG-3’; reverse: 5’- CGTACATCCGTTGGAACGTG-3’. Actin (mouse) forward: 5’- CGCCACCAGTTCGCCATGGA-3’; reverse: 5’- TACAGCCCGGGGAGCATCGT-3’. HLA-B (human) forward: 5’- CAGTTCGTGAGGTTCGACAG-3’; reverse: 5’- CAGCCGTACATGCTCTGGA-3’. TAP1 (human) forward: 5’-CTGGGGAAGTCACCCTACC-3’; reverse: 5’- CAGAGGCTCCCGAGTTTGTG-3’. TAP2 (human) forward: 5’- TGGACGCGGCTTTACTGTG-3’; reverse: 5’- GCAGCCCTCTTAGCTTTAGCA-3’. LMP2 (human) forward: 5’- GCACCAACCGGGGACTTAC-3’; reverse: 5’- CACTCGGGAATCAGAACCCAT-3’. B2M (human) forward: 5’- GAGGCTATCCAGCGTACTCCA-3’; reverse: 5’- CGGCAGGCATACTCATCTTTT-3’. ACTIN (human) forward: 5’-CACCAACTGGGACGACAT-3’; reverse: 5’- ACAGCCTGGATAGCAACG-3’. Relative copy number was determined by calculating the fold change difference in the gene of interest relative to Actin (mouse) or ACTIN (human). RT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7300 machine.

Generation of mouse DCs

Mouse DCs were obtained from the bone marrow of FVB/NJ mice by modifying the previously described protocol.115 For DC generation, bone marrow cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (Stem Cell Technologies, 78017), 10% FBS, and 100 μg/ml PenStrep. Fresh RPMI 1640 with 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10% FBS, and 100 μg/ml PenStrep was added after 3 days, and non-adherent cells (DCs) were harvested and co-cultured with PP cells after another 2 days.

Co-culture experiments

For in vitro co-culture of tumor cells with CD8+ T cells, B16-OVA and EL4-OVA cells were pretreated with vitC or PBS for 3 days. CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens of OT-I mice using a CD8a+ T-cell isolation kit (StemCell Technologies ) with an autoMACS Pro Separator. Isolated CD8+ T cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) with 5% FBS, labeled with 5 μM CFSE (Biolegend) for 10 min in the dark at room temperature, and washed twice in 10× volume of T cell media (RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco)). One hundred thousand CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with vitC- or control-pretreated tumor cells at a ratio of 1:8 tumor cells: T cells in RPMI 1640 supplemented with CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (1:1 ratio of cells: beads, ThermoFisher) 2.5 ng/ml IL-7 (Biolegend), 50 ng/ml IL-15 (Biolegend), and 2 ng/ml IL-2 (Biolegend) for 2 days at 37°C in the dark. At the experimental endpoint, CD8+ T cell proliferation and activation were analyzed by flow cytometry.

For in vitro co-culture of tumor cells with DCs, PP cells were pretreated with vitC or PBS for 3 days. One hundred thousand mouse bone marrow-derived DCs were co-cultured with vitC- or control-pretreated PP cells at a ratio of 1:4 tumor cells: DCs in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10% FBS and lipofectamine 3000 (2 μl/ml, Invitrogen) for 2 days at 37°C. At the experimental endpoint, DCs activation was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Generation of STAT1, TET2 and HIF1α deficient cells

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing systems were used to generate STAT1-deficient cells.116 Oligos sequences for guide RNAs were as follows. Stat1 (mouse) #1 forward: 5’- CACCGGAACCCCCCGTGCGCGTGG-3’; #1 reverse: 5’-AAACCCACGCGCACGGGGGGTTCC-3’. Stat1 (mouse) #2 forward: 5’-CACCGGTCGCAAACGAGACATCAT-3’; #2 reverse: 5’-AAACATGATGTCTCGTTTGCGACC-3’. Tet2 (mouse) #1 forward: 5’-CACCGCTACACGGCAGCAGCTTCG-3’; #1 reverse: 5’- AAACCGAAGCTGCTGCCGTGTAGC-3’. Tet2 (mouse) #2 forward: 5’- CACCGAGTGCTTCATGCAAATTCG-3’; #2 reverse: 5’- AAACCGAATTTGCATGAAGCACTC-3’. Hif1α (mouse) #1 forward: 5’- CACCGGGCGACACCATCATCTCTC-3’; #1 reverse: 5’- AAACGAGAGATGATGGTGTCGCCC-3’. Hif1α (mouse) #2 forward: 5’- CACCGCAACCTCTTGATTCAGTGC-3’; #2 reverse: 5’- AAACGCACTGAATCAAGAGGTTGC-3’. Annealed guide oligos were cloned into the CRISPR-Cas9 expression vector PX458. The constructed plasmids were transfected into cells. The next day, single GFP+ cells were sorted into 96-well plates by flow cytometry. Two weeks later, colonies emerged and single colonies were expanded into 6 well plates. STAT1, TET2, HIF1α knockout cells, and control cells were selected by western blot.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and immunoprecipitation (IP)

Cells were lysed using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% NP-40 (for Co-IP) or 0.5% NP-40 (for IP)) at 4°C for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 rcf for 15 min and the supernatants were collected and incubated with GFP-Trap magnetic agarose (Chromotek, gtma-20) overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads with lysis buffer three times, they were resuspended in 1× western blotting loading buffer and denatured at 95°C for 10 minutes.

Immunofluorescence

For endogenous STAT1 immunofluorescence, cultured cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The fixative was aspirated, and the cells were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 min each. The cells were then covered with ice-cold 100% methanol and incubated for 10 min at −20°C. After incubation, the cells were rinsed in PBS for 5 min. The specimen was blocked in blocking buffer (5% normal serum from the same species as the secondary antibody and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 60 min. The blocking solution was aspirated, and diluted STAT1 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 14994) was applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. The cells were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 min each, followed by incubation with a fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody (ThermoFisher, A-11008) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. The cells were then rinsed in PBS and incubated in PBS with DAPI (Cell Signaling Technology, 8961). Specimens were examined immediately using the appropriate excitation wavelength. For overexpressed STAT1-GFP immunofluorescence, cultured cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The fixative was aspirated, and the cells were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 min each. The cells were then incubated in PBS with DAPI (Cell Signaling Technology, 8961). Specimens were examined immediately using the appropriate excitation wavelength.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 9 (Graphpad Software Inc.). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for tumor growth analysis. For other analysis, unpaired two-tailed Student’s test (for normally distributed data) and Mann-Whitney nonparametric test (for skewed data that deviated from normality) were used to compare two conditions. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (for normally distributed data) and Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test (for skewed data) were used to compare three or more means. Quantitative data are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant; ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Figure. S1. Formation of vitC-derived vitcylation in vitro, related to figure 1

(A and B) Molecular mechanisms of lysine succinylation (A) and homocysteinylation formation(B) are presented, with the reactive lactone bonds circled for clarity.

(C) The structures, molecular weights, and pKa values of ascorbic acid, ascorbate anion, and dehydroascorbic acid are shown.

(D) The structures of cysteine ascorbylation and lysine ascorbylations are illustrated to differentiate them from lysine vitcylation.

(E) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with vehicle, 2 mM vitC, or 2 mM DHA at 37°C for 3 hours, and the formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.

(F) The structures of vitC, 1-13C-vitC, 2-13C-vitC, and 1, 2-13C-vitC used in this study are displayed.

(G and H) MS/MS spectrum (left) and MS spectrum (right) of the unmodified peptide, vitcylated peptide, 1-13C-vitcylated peptide, 2-13C-vitcylated peptide, and 1, 2-13C-vitcylated peptide (Ac-VLSPKAVQRF (G) and Ac-YAPVAKDLASR (H)) detected by HPLC-MS/MS. Lysine-containing unmodified fragments, vitcylated fragments, 1-13C-vitcylated fragments, 2-13C-vitcylated fragments, and 1, 2-13C-vitcylated fragments are marked with green, red, and blue colors, respectively.

Figure. S2. VitC specifically induces lysine vitcylation in vitro, related to figure 1

(A and B) Synthetic alanine-containing peptides (A) and cysteine-containing peptides (B) were incubated with either a vehicle or 2 mM vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.(C and D) Synthetic N-terminal unblocked peptides (C) and multiple lysine-containing peptides

(D) were incubated with either a vehicle or 2 mM vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.

(E) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with vehicle or 2 mM 1-13C-vitC at 37°C for 3 hours, and the formation of vitcylated peptides, along with any other byproducts, was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.(F) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with a vehicle or 2 mM vitC in tris buffer or PBS buffer at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.

(G) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides (peptide sequences were listed above the spectrum) were incubated with a vehicle or 2 mM vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS.

(H) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with varying concentrations of vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS. The relative vitcylation levels were quantified (right, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(I) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with varying concentrations of vitC at 37°C for 3 hours. Corresponding lysine-to-arginine substitution peptides were used as controls. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS, and accurate vitcylation levels were quantified (right, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. (N.D. Not Detectable).

(J) Synthetic lysine-containing peptides were incubated with 2 mM vitC in Tris-HCl buffer at different pH levels at 37°C for 3 hours. The formation of vitcylated peptides was detected by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS, and the relative vitcylation levels were quantified (right, n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Figure. S3. Lysine vitcylation exists in cells, related to figure 2

(A) Levels of vitcylation of mouse GAPDH K5 and mouse SMC1A K129 were determined by HPLC-MS/MS analysis. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.(B) Summary of the numbers of vitcylated proteins and sites identified in E0771 proteomic samples and E0771 proteomic samples incubated with vitC (1 mM for 12 hours) in Tris-HCl buffer at the indicated pH in vitro. E0771 proteomic samples were extracted by acetone.(C) Intracellular vitC levels were measured in Cal-51, E0771, and PP cells cultured in varying concentrations of vitC for 12 hours (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(D) VitC levels were measured in RPMI 1640 medium and DMEM/F12 medium with or without 10% FBS (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

(E) Intracellular vitC levels were measured in Cal-51, E0771, and PP cells cultured in medium with or without 10% FBS (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM, ****p < 0.0001.

(F) Venn diagram of shared vitcylated proteins identified in Cal-51 cells (human) and E0771 cells (mouse).

(G) Numbers of vitcylated proteins and sites identified in E0771 cells treated with varying concentrations of vitC are summarized.

(H) Subcellular locations of lysine vitcylated proteins identified in Cal-51 cells. The locations are classified as nuclear, cytosol, plasma membrane, extracellular, mitochondrial, cytosol_nuclear, and other compartments.

(I) Top ten gene ontology molecular function enrichment categories of vitcylated proteins identified in Cal-51 cells.(J) Top ten KEGG-based enrichment categories of lysine vitcylated proteins identified in Cal-51 cells.(K) Top ten gene ontology biological process enrichment categories of vitcylated proteins identified in Cal-51 cells.

(L) Sequence probability logos of significantly enriched vitcylated site motifs for ±10 amino acids around the lysine vitcylation sites identified in Cal-51 cells (human) and E0771 cells (mouse). The size of each letter represents the frequency of the amino acid residue at that position.