Abstract

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have enabled detailed characterization of plant mitochondrial genomes. Here, we assembled and analyzed the mitochondrial genome of Quercus chenii Nakai, a key oak species in Fagaceae, using Illumina NovaSeq6000. The genome consists of a 364,958 bp linear and a 53,677 bp circular chromosome, totaling 418,635 bp with a GC content of 45.6%. Repeat-rich regions (210–250 and 300–340 kb) may facilitate structural rearrangements, while extensive RNA editing-particularly in nad4 and ccmF-likely enhances protein functionality and mitochondrial adaptability. Comparative collinearity analysis showed high structural conservation with Q. acutissima Carruth. (90.92%) but marked divergence from Fagus sylvatica L. (35.80%), suggesting lineage-specific rearrangements. Phylogenetic analysis based on the mitochondrial genome supports the same placement of Q. chenii within Fagaceae as that derived from the chloroplast genome. The Ka/Ks analysis across Fagaceae mitochondrial genomes revealed strong conservation of core genes, with adaptive variations in energy metabolism-related genes, suggesting functional divergence linked to metabolic optimization under environmental stress. These findings highlight the distinct evolutionary strategies of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes: the former optimizing energy production, while the latter fine-tunes photosynthesis and stress responses. Comparison analysis with the chloroplast genome further revealed both conserved (psbT and psbC) and divergent (ndhD and ndhF) genes, implying potential historical gene transfer events. Together, these findings highlight the dynamic yet conserved nature of the Q. chenii mitochondrial genome and provide new insights into organellar genome evolution, structural plasticity, and adaptive mechanisms within the Fagaceae family.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11877-3.

Keywords: Mitochondrial genome, Quercus chenii, Genome evolution, Repeat-mediated rearrangements, Fagaceae phylogeny

Introduction

Oak trees (Quercus spp.), prominent members of the Fagaceae family, are widely distributed across temperate and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere [1]. Oaks play essential roles in ecosystems, and their diverse species and extensive range make them ideal models for studying plant evolution and ecological adaptation [2, 3]. In China, Quercus chenii Nakai is a noteworthy species, prized for its high-quality timber and abundant acorn resources [4]. Oak wood, known for its hardness and durability, is commonly used in high-end furniture and oak barrels [5, 6]. Acorns are not only a vital food source for wildlife but also have practical applications, such as acorn starch, which is used in traditional medicine and the modern food industry [7–9]. These ecological and industrial roles highlight the importance of Q. chenii, emphasizing the need for deeper genetic and genomic investigations to support its conservation and sustainable use. The Fagaceae family, which includes eight genera: Quercus L., Castanea Mill., Fagus L., Lithocarpus Blume, Castanopsis (D. Don) Spach, Trigonobalanus Forman, Chrysolepis Hjelmq., and Notholithocarpus P. S. Manos, C. H. Cannon & S.H. Oh provide an ideal system for studying mitochondrial genome evolution [10–12]. Previous studies have focused on intergeneric comparisons within Fagaceae, revealing significant variation in genome size, structure, and sequence conservation [2, 13–15]. For instance, Castanea mollissima Blume and Fagus sylvatica L. exhibit distinct structural features and patterns of genomic rearrangement, reflecting evolutionary divergence between genera [16]. Similarly, the mitochondrial genome of Lithocarpus litseifolius (Hance) Chun has been characterized, showing unique structural diversity within the family [17]. However, less is known about mitochondrial genome variation among closely related species, particularly within the same genus or clade. For example, the difference in mitochondrial genome structure and function between closely related species such as Q. chenii and Q. acutissima, both within the same section of the Quercus genus, remain largely unexplored. Investigating these genomic differences at a finer phylogenetic scale could provide valuable insights into the evolutionary dynamics and functional adaptations of mitochondrial genomes, shedding light on processes such as gene rearrangement, sequence divergence, and adaptive evolution in this ecologically and economically important group of trees. Plant mitochondrial genomes are highly dynamic, largely due to homologous recombination mediated by repetitive sequences, leading to diverse genomic configurations [18, 19]. For example, the mitochondrial genome of Melastoma dodecandrum Lour., assembled using a PacBio-Illumina hybrid strategy, revealed large-scale rearrangements caused by micro inversions, along with lateral gene transfer from nuclear and chloroplast genomes [20]. Similarly, the mitochondrial genome of various pines exhibit a multi-branching structure [21], while Oenothera L. displays sub-circular molecules formed via recombination events mediated by repetitive sequences [22]. These findings underscore the structural complexity of plant mitochondrial genomes and their potential roles in species adaptation. Within the Fagaceae family, the mitochondrial genomes of C. mollissima, F. sylvatica, Q. acutissima, and L. litseifolius have been characterized, revealing features such as repeat-mediated rearrangements and distinct RNA editing patterns [23]. However, systematic studies on the mitochondrial genome of Q. chenii remain scarce, leaving its structural characterization and evolutionary mechanisms largely unexplored. This gap in research presents an opportunity to investigate the unique genomic features of Q. chenii and their potential role in the species’ adaptation and evolutionary dynamics within the Fagaceae family.

This study aims to explore the mitochondrial genome of Q. chenii to unravel its complex genomic structures and the evolutionary mechanisms driving environmental adaptation. Using high-throughput sequencing, we aim to identify unique structural features, investigate repeat-mediated rearrangements, and characterize RNA editing patterns. Comparative analyses with closely related species such as Q. acutissima and more distantly related species like C. mollissima, F. sylvatica, and L. litseifolius, will highlight both conserved and divergent genomic features. These findings will provide insights into the interplay between genome stability and functional plasticity, enhancing our understanding of mitochondrial genome evolution within the Fagaceae family.

Result

Description of the Quercus species mitogenomes

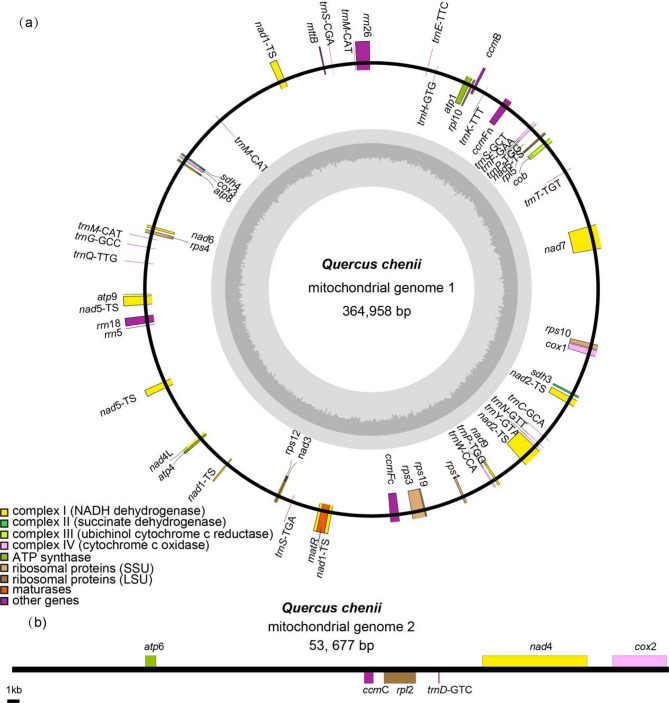

We characterized the mitochondrial genome structure of Q. chenii, which consists of two distinct components: a linear chromosome (364,958 bp) and a circular chromosome (53,677 bp) (Fig. 1). The total length of the mitogenome is 418,635 bp, as determined by sequencing results (Table 1) and comparative analysis. The Q. chenii mitogenome contains 35 protein-coding genes (PCGs), with an average coding sequence (CDS) length of 30,927 bp, representing 7.4% of the total genome length and a gene density of 57.4%. Additionally, the genome includes 20 tRNA, as well as 35 mRNA, and 3 rRNA genes, and 2 pseudogenes.

Fig. 1.

The Schematic diagram of the structure and gene distribution of the Quercus species mitogenome. Genes shown on the outside and inside of the circle are transcribed clockwise and counterclockwise, respectively. The dark gray region in the inner circle depicts GC content

Table 1.

Summary of basic information on two oak mitochondrial genomes

| Species | Type | Total_len/bp | GC/% | PCGs_nu | CDS_len/bp | CDS_GC/% | tRNA_nu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q. chenii | linear | 364,958 | 45.56 | 30 | 26,001 | 43.09 | 19 |

| Q. chenii | circular | 53,677 | 45.8 | 5 | 4926 | 42.51 | 1 |

| Total | 418,635 | 45.6 | 35 | 30,927 | 43 | 20 | |

| tRNA_len/bp | tRNA_GC/% | rRNA_nu | rRNA_len/bp | rRNA_GC/% | pseudo_gene_nu | Total_gene_nu | |

| Q. chenii | 1413 | 50.6 | 3 | 5472 | 51.97 | 3 | 55 |

| Q. chenii | 74 | 63.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 1487 | 51.24 | 3 | 5472 | 51.97 | 2 | 61 |

len represents length; nu represents number; CDS represents coding sequence; PCGs represents protein-coding genes

Repetitive sequences, RNA editing events and RSCU analysis

The mitochondrial genome of Q. chenii contains 18 tandem repeats, 151 simple repeats, and 161 dispersed repeats (Table S1). SSRs and tandem repeats are predominantly concentrated in specific genomic regions, particularly between 210 and 250 kb, as well as 300 and 340 kb. These regions exhibit a high density repeat and more complex genome structures (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The distribution map of repetitive sequences on the Q.chenii genome. The outermost circle represents the mitochondrial genome sequence, followed inward by simple repeat sequences, tandem repeat sequences, and dispersed repeat sequences

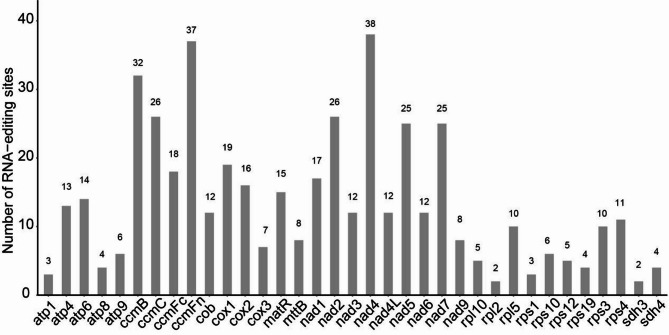

In the mitochondrial genomes of Q. chenii, certain genes, such as nad4 (38 editing sites), ccmF (37 editing sites) and ccmB (32 editing cites), exhibit a high number of RNA editing sites. In contrast, genes like rpl10 (2), rpl2 (2) and sdh (2) display relatively fewer editing sites (Fig. 3). A statistical analysis of RNA editing sites reveals significant differences in the distribution of editing events based on amino acid properties (Table 2). Among the various types of RNA editing, hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic transition are the most frequent, totaling 229 occurrences, or 49.04% of all editing events. The most common transformations in this category are TCA (Ser) to TTA (Leu) and TCG (Ser) to TTG (Leu), which occur 67 and 42 times, respectively. Hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic editing events are the second most prevalent, with 147 occurrences (31.48% of the total events). The most frequent changes are CCA (Pro) to CTA (Leu) and CCG (Pro) to CTG (Leu), observed 44 and 29 instances, respectively. Hydrophilic-to-hydrophilic editing events account for 52 occurrences (11.13% of the total), with CAT (His) to TAT (Tyr) and CGT (Arg) to TGT (Cys) being the most common, occurring 11 and 24 times, respectively. Notably, hydrophilic-to-stop codon editing events are rare, accounting for just 3 occurrences (0.64% of the total), primarily CGA (Rrg) to TGA (stop). In summary, RNA editing events involving transition between hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids account for over 80% of all editing events, making these the predominant types of RNA editing in the Q. chenii mitochondrial genome.

Fig. 3.

Prediction of RNA editing sites in the mitochondrial genome

Table 2.

Statistics of RNA editing sites prediction

| Type | RNA-editing | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| hydrophilic-hydrophilic | CAC (H) = > TAC (Y) | 9 | |

| CAT (H) = > TAT (Y) | 11 | ||

| CGC (R) = > TGC (C) | 8 | ||

| CGT (R) = > TGT (C) | 24 | ||

| total | 52 | 11.13% | |

| hydrophilic-hydrophobic | ACA (T) = > ATA (I) | 6 | |

| ACC (T) = > ATC (I) | 1 | ||

| ACG (T) = > ATG (M) | 7 | ||

| ACT (T) = > ATT (I) | 3 | ||

| CGG (R) = > TGG (W) | 30 | ||

| TCA (S) = > TTA (L) | 67 | ||

| TCC (S) = > TTC (F) | 33 | ||

| TCG (S) = > TTG (L) | 42 | ||

| TCT (S) = > TTT (F) | 40 | ||

| total | 229 | 49.04% | |

| hydrophilic-stop | CGA (R) = > TGA (X) | 3 | |

| total | 3 | 0.64% | |

| CCA (P) = > TCA (S) | 7 | ||

| CCC (P) = > TCC (S) | 11 | ||

| CCG (P) = > TCG (S) | 3 | ||

| CCT (P) = > TCT (S) | 15 | ||

| total | 36 | 7.71% | |

| hydrophobic-hydrophilic | CCA (P) = > CTA (L) | 44 | |

| CCC (P) = > CTC (L) | 6 | ||

| CCC (P) = > TTC (F) | 6 | ||

| CCG (P) = > CTG (L) | 29 | ||

| CCT (P) = > CTT (L) | 24 | ||

| CCT (P) = > TTT (F) | 10 | ||

| CTC (L) = > TTC (F) | 6 | ||

| CTT (L) = > TTT (F) | 12 | ||

| GCA (A) = > GTA (V) | 1 | ||

| GCG (A) = > GTG (V) | 6 | ||

| GCT (A) = > GTT (V) | 3 | ||

| total | 147 | 31.48% | |

| All | 467 | 100% |

Codon preference analysis of the Q. chenii mitochondrial genome reveals distinct preferences for specific synonymous codons across different amino acids (Table 3). For instance, leucine (Leu) and alanine (Ala) show a marked preference for the codons UUA and GCU, with RSCU values of 1.4521 and 1.5767, respectively, both exceeding the values of other synonymous codons. Among stop codons, UAA is the most frequently used, with an RSCU value of 1.2857, while UAG and UGA are less common, with RSCU values of 0.6 and 1.1143, respectively, indicating that UAA as the primary termination signal. For other amino acids, glutamine (Gln) strongly favors CAA (RSCU of 1.4786), while arginine (Arg) prefers AGA (RSCU of 1.4623). Notably, methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp) each have a single coding codon (AUG and UGG, respectively), both with RSCU values of 1, indicating no preference between synonymous codons for these amino acids. In summary, the Q. chenii mitochondrial genome exhibits a distinct pattern of codon preference across various amino acids, a pattern likely shaped by evolutionary pressures, gene expression efficiency, and protein stability.

Table 3.

Statistics of codon preference

| AminoAcid | Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU | AminoAcid | Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | Ter | UAA | 15 | 1.2857 | M | Met | AUG | 277 | 1 |

| * | Ter | UAG | 7 | 0.6 | N | Asn | AAC | 112 | 0.6667 |

| * | Ter | UGA | 13 | 1.1143 | N | Asn | AAU | 224 | 1.3333 |

| A | Ala | GCA | 158 | 0.9693 | P | Pro | CCA | 168 | 1.1748 |

| A | Ala | GCC | 153 | 0.9387 | P | Pro | CCC | 112 | 0.7832 |

| A | Ala | GCG | 84 | 0.5153 | P | Pro | CCG | 88 | 0.6154 |

| A | Ala | GCU | 257 | 1.5767 | P | Pro | CCU | 204 | 1.4266 |

| C | Cys | UGC | 61 | 0.7922 | Q | Gln | CAA | 207 | 1.4786 |

| C | Cys | UGU | 93 | 1.2078 | Q | Gln | CAG | 73 | 0.5214 |

| D | Asp | GAC | 102 | 0.6126 | R | Arg | AGA | 165 | 1.4623 |

| D | Asp | GAU | 231 | 1.3874 | R | Arg | AGG | 87 | 0.771 |

| E | Glu | GAA | 306 | 1.3973 | R | Arg | CGA | 147 | 1.3028 |

| E | Glu | GAG | 132 | 0.6027 | R | Arg | CGC | 66 | 0.5849 |

| F | Phe | UUC | 298 | 0.8638 | R | Arg | CGG | 84 | 0.7445 |

| F | Phe | UUU | 392 | 1.1362 | R | Arg | CGU | 128 | 1.1344 |

| G | Gly | GGA | 256 | 1.4322 | S | Ser | AGC | 103 | 0.6498 |

| G | Gly | GGC | 100 | 0.5594 | S | Ser | AGU | 164 | 1.0347 |

| G | Gly | GGG | 136 | 0.7608 | S | Ser | UCA | 174 | 1.0978 |

| G | Gly | GGU | 223 | 1.2476 | S | Ser | UCC | 159 | 1.0032 |

| H | His | CAC | 61 | 0.5 | S | Ser | UCG | 134 | 0.8454 |

| H | His | CAU | 183 | 1.5 | S | Ser | UCU | 217 | 1.3691 |

| I | Ile | AUA | 215 | 0.8113 | T | Thr | ACA | 131 | 0.9962 |

| I | Ile | AUC | 230 | 0.8679 | T | Thr | ACC | 139 | 1.057 |

| I | Ile | AUU | 350 | 1.3208 | T | Thr | ACG | 73 | 0.5551 |

| K | Lys | AAA | 260 | 1.1899 | T | Thr | ACU | 183 | 1.3916 |

| K | Lys | AAG | 177 | 0.8101 | V | Val | GUA | 189 | 1.1924 |

| L | Leu | CUA | 168 | 0.9205 | V | Val | GUC | 121 | 0.7634 |

| L | Leu | CUC | 118 | 0.6466 | V | Val | GUG | 137 | 0.8644 |

| L | Leu | CUG | 104 | 0.5699 | V | Val | GUU | 187 | 1.1798 |

| L | Leu | CUU | 222 | 1.2164 | W | Trp | UGG | 155 | 1 |

| L | Leu | UUA | 265 | 1.4521 | Y | Tyr | UAC | 72 | 0.4601 |

| L | Leu | UUG | 218 | 1.1945 | Y | Tyr | UAU | 241 | 1.5399 |

Mitochondrial sequence collinearity analysis

The collinearity analysis reveals substantial variation in mitochondrial genome structure among species within the Fagaceae family (Fig. 4). Specifically, Q. acutissima and Q. chenii exhibit high collinearity percentages (85.50 and 90.92%, respectively), indicating strong genome conservation and close phylogenetic relationships. In contrast, the collinearity levels between F. sylvatica and Q. chenii are markedly lower (35.80 and 42.73%, respectively), reflecting substantial genomic rearrangements and a greater evolutionary divergence. Intermediate collinearity levels are observed between L. littoralis and C. mollissima (53.58 and 69.01%, respectively), suggesting moderate structural conservation, but with significant genomic rearrangements. Moreover, the distribution and fragmentation of red and blue syntenic blocks further underscore varying degrees of genomic rearrangements: distantly related species like F. sylvatica exhibit highly fragmented patterns, while more closely related species, such as Q. acutissima and Q. chenii. Display more cohesive syntenic patterns. Collectively, these findings illustrate the dynamic interplay between genome conservation and structural rearrangement, providing valuable insights into the evolutionary relationships and genomic architecture within the Fagaceae family.

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial sequence collinearity analysis of species within the Fagaceae family (The horizontal axis in each box represents the assembled sequences, while the vertical axis represents other sequences. The values in parentheses indicate the proportion of homologous sequences relative to the total genome. The red lines within the box represent forward alignments, and the blue lines represent reverse complementary alignments)

Evolutionary analysis in Fagaceae

The results indicate that most genes exhibit a Ka/Ks ratio of less than 1, suggesting that they are primarily under purifying selection, with a lower nonsynonymous substitution rate compared to the synonymous substitution rate. However, a few genes, such as nad1 and atp4, are outliers with significantly higher Ka/Ks ratios, indicating potential positive selection in certain species (Fig. 5). Additionally, genes with significant differences in Ka/Ks distribution ratios, such as atp6, rpl2, and rps4, highlight notable evolutionary trends. Among these, ribosomal protein-related genes (cox, cob) exhibit low, narrow Ka/Ks distributions, suggesting strong purifying selection and high functional conservation. In contrast, mitochondrial function-related genes (nad families) display wider Ka/Ks ranges, with genes like nad1 and nad4 showing higher median values. This suggests these genes may have undergone stronger selective pressures or functional divergence. Overall, the findings reveal significant variation in selective pressures among genes. The identification of significant genes and outliers provides valuable insights into species adaptation and functional evolution.

Fig. 5.

The selective pressure of genes within the Fagaceae family. Note: Genes with significance (P-Value (Fisher) less than 0.05) are marked with a red asterisk (*) above the maximum value

The results reveal significant variation in nucleotide diversity (π) across different gene regions (Fig. 6). Most genes display low π values, typically below 0.004, indicating minimal sequence variation and strong conservation. However, certain genes, such as cox2, rps10, and rps3, exhibit notably higher π values, reflecting greater nucleotide diversity in these regions. Conversely, genes like matR, nad7, and nad4 consistently show low π values, emphasizing their highly conserved nature. Further analysis reveals considerable variation in nucleotide diversity (π) within the rps gene family. Some genes, such as rps3, rps10, rps1, and rps19, exhibit significantly higher π values, indicating substantial sequence diversity. In contrast, rps12 shows an exceptionally low π value, suggesting a highly conserved sequence. This observation highlights the heterogeneity in nucleotide diversity within the rps family, where certain genes demonstrating significant variability while others remain highly conserved. Overall, the variation in π values across gene regions reveal distinct patterns of nucleotide diversity. These patterns likely reflect different evolutionary pressures and functional constraints acting on these genes.

Fig. 6.

The magnitude of nucleotide sequence variation within the Fagaceae family

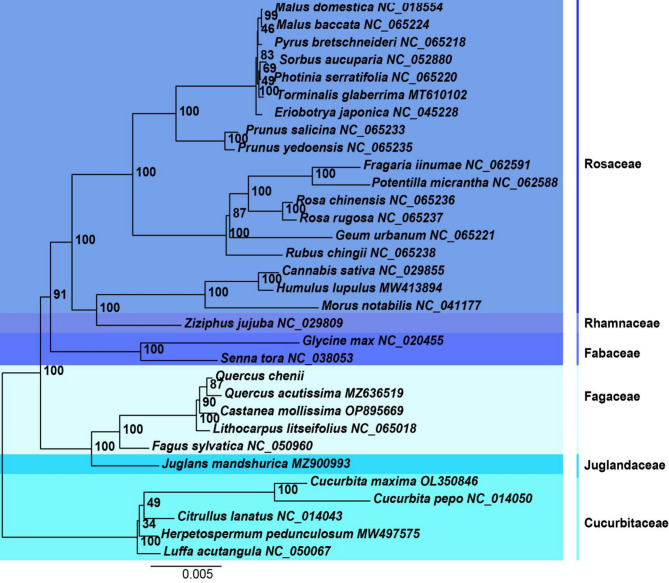

Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial genomes shows that Q. chenii and Q. acutissima cluster in the same branch with a high node support value of 87, indicating a close phylogenetic relationship and supporting the hypothesis that they share a recent common ancestor (Fig. 7). Both species belong to the Section Cerris of the genus Quercus, and the strong support for this clade further confirms their shared evolutionary history. Other genera within, such as C. mollissima and L. litseifolius, form adjacent branches with a node support value of 100, suggesting a relatively close phylogenetic relationship with Quercus. This pattern reflects the unique genomic structures and functional traits within the family. In contrast, F. sylvatica forms a more distinct branch, indicating a greater evolutionary divergence, likely due to differences or evolutionary divergence. Furthermore, species within Fagaceae are clearly separated from other families like Rosaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Fabaceae, highlighting the distinct evolutionary path of Fagaceae, shaped by genomic adaptations. Juglans mandshurica Maxim. (from the Juglandaceae family) is positioned relatively close to Fagaceae species, suggesting some conserved genomic features between these two families. These results reinforce the evolutionary distinctiveness of Fagaceae and its internal divergence, offering insights into its genomic evolution within the broader context of Fagales.

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial genomes

Analysis of homologous sequences in chloroplast and mitochondria

Comparative analysis of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Q. chenii reveals notable variation in sequence similarity across different genes (Table 4). Regions such as psbT (100% identity) and psbC (98.11% identity) exhibit high sequence conservation, indicating strong homology between the two genomes. In contrast, gene fragments, including ndhD and ndhF, show sequence identities below 50%, reflecting significant evolutionary divergence. Alignment lengths vary considerably, with longer alignments (e.g., psbB and ycf2) encompassing more extensive homologous regions, while shorter fragments (e.g., petL and rps4) suggest partial sequence conservation. Additionally, higher counts of mismatches and gap openings are observed in low-identity regions, such as ndhD and ndhF, underscoring the complexity of sequence divergence. The dispersed start and end positions of alignments between the two genomes further suggest potential gene rearrangements or translocations. This supports evidence of intergenomic sequence transfers and underscores the dynamic evolutionary processes shaping the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Q. chenii.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes

| Genes | Identity (%) | length | mismatches | Gap openings | start in query | end in query | start in subject | end in subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atpA_len507 | 58.964 | 502 | 190 | 4 | 5 | 493 | 66,867 | 65,371 |

| atpB_len498 | 25.806 | 310 | 210 | 5 | 69 | 366 | 66,681 | 65,776 |

| ndhA_len363 | 41.748 | 103 | 60 | 0 | 51 | 153 | 233,495 | 233,803 |

| ndhA_len363 | 65.714 | 35 | 12 | 0 | 215 | 249 | 115,656 | 115,760 |

| ndhB_len510 | 32.407 | 108 | 73 | 0 | 91 | 198 | 334,725 | 334,402 |

| ndhB_len510 | 35.498 | 231 | 137 | 4 | 243 | 465 | 317,854 | 317,174 |

| ndhC_len120 | 36.275 | 102 | 61 | 1 | 21 | 118 | 249,440 | 249,135 |

| ndhD_len505 | 24.551 | 167 | 120 | 3 | 294 | 457 | 317,644 | 317,153 |

| ndhD_len505 | 26.776 | 183 | 118 | 7 | 230 | 406 | 185,646 | 186,164 |

| ndhD_len505 | 27.517 | 149 | 90 | 4 | 332 | 477 | 44,326 | 44,727 |

| ndhD_len505 | 28.696 | 115 | 62 | 3 | 69 | 175 | 38,629 | 38,937 |

| ndhD_len505 | 34.302 | 172 | 109 | 2 | 156 | 326 | 40,334 | 40,840 |

| ndhF_len753 | 30.508 | 177 | 106 | 6 | 246 | 417 | 317,812 | 317,318 |

| ndhF_len753 | 46.459 | 353 | 172 | 5 | 110 | 454 | 185,247 | 186,278 |

| ndhF_len753 | 66.667 | 33 | 11 | 0 | 34 | 66 | 216,319 | 216,221 |

| ndhH_len393 | 34.921 | 63 | 37 | 1 | 4 | 62 | 16,420 | 16,232 |

| ndhH_len393 | 38.312 | 154 | 95 | 0 | 72 | 225 | 14,021 | 13,560 |

| ndhH_len393 | 39.189 | 74 | 40 | 1 | 228 | 301 | 12,498 | 12,292 |

| ndhH_len393 | 49.333 | 75 | 38 | 0 | 319 | 393 | 10,493 | 10,269 |

| ndhJ_len158 | 32.292 | 96 | 48 | 2 | 77 | 155 | 307,452 | 307,165 |

| petB_len215 | 33.862 | 189 | 124 | 1 | 27 | 215 | 40,862 | 40,299 |

| petD_len160 | 40.58 | 69 | 40 | 1 | 65 | 133 | 40,154 | 39,951 |

| petG_len37 | 86.486 | 37 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 37 | 305,792 | 305,902 |

| petL_len31 | 67.742 | 31 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 305,526 | 305,618 |

| psbA_len353 | 35.146 | 239 | 149 | 4 | 67 | 302 | 304,184 | 303,477 |

| psbB_len508 | 96.078 | 306 | 12 | 0 | 203 | 508 | 6081 | 6998 |

| psbC_len487 | 84.483 | 58 | 7 | 1 | 320 | 375 | 232,391 | 232,564 |

| psbC_len487 | 98.113 | 106 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 106 | 303,406 | 303,089 |

| psbD_len353 | 98.095 | 315 | 6 | 0 | 39 | 353 | 304,259 | 303,315 |

| psbE_len83 | 93.548 | 31 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 304,342 | 304,250 |

| psbT_len35 | 100 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 7188 | 7292 |

| rpl16_len135 | 42.553 | 141 | 72 | 2 | 1 | 132 | 284,081 | 283,659 |

| rpl2_len286 | 41.129 | 124 | 57 | 3 | 123 | 242 | 30,286 | 29,951 |

| rpl2_len286 | 50.877 | 57 | 27 | 1 | 38 | 94 | 32,941 | 32,774 |

| rpl2_len287 | 40.8 | 125 | 57 | 3 | 123 | 243 | 30,286 | 29,951 |

| rpl2_len287 | 50.877 | 57 | 27 | 1 | 38 | 94 | 32,941 | 32,774 |

| rps12_len123 | 60.163 | 123 | 49 | 0 | 1 | 123 | 249,077 | 248,709 |

| rps12_len124 | 57.5 | 120 | 51 | 0 | 1 | 120 | 249,077 | 248,718 |

| rps3_len221 | 34.906 | 106 | 65 | 2 | 114 | 215 | 284,424 | 284,107 |

| rps4_len202 | 43.396 | 53 | 30 | 0 | 88 | 140 | 168,109 | 167,951 |

| ycf2_len2277 | 63.158 | 38 | 13 | 1 | 976 | 1013 | 306,874 | 306,984 |

Discussion

Structural diversity and evolutionary patterns in Fagaceae mitochondrial genomes

The mitochondrial genome plays a crucial role in biological processes, such as energy metabolism, biosynthesis, signal transduction, and responses to environmental stress [24–26]. The proteins, tRNAs, and rRNAs encoded by the mitochondrial genome are critical not only for maintaining normal mitochondrial function but also for participating in complex molecular mechanisms that operate in coordination with the nuclear genome [27, 28]. Notably, the structure of mitochondrial genomes exhibits significant diversity across species, including variations in genome morphology such as single circular, multiple circular, linear, and multipartite configurations. In the Fagaceae family, mitochondrial genome configurations vary widely, ranging from single circular chromosomes, as seen in F. sylvatica [29], to multipartite structures, including the combination of linear and circular chromosomes found in Q. chenii.

Mitochondrial genomes in plants exhibit considerable diversity in size, structure, and function [26]. Some plants have larger mitochondrial genomes, which are often associated with complex gene rearrangements and abundant repetitive sequences [30, 31]. For example, the mitochondrial genome of Silene conica L. is approximately 11 Mb, making it one of the largest mitochondrial genomes known among plants [32]. Similarly, the mitochondrial genome of Tylosema esculentum (Burch.) A. Schreib. is around 10 Mb and demonstrates a multipartite genomic structure, which is relatively rare in plants and may be linked to adaptive features [33]. The mitochondrial genome of Nicotiana tabacum L. is approximately 5.1 Mb, featuring significant genome expansion and abundant repetitive sequences. In contrast, many plant species exhibit smaller mitochondrial genomes, such as Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. with approximately 367 kb and Vitis vinifera L. with about 500 kb, both of which lack significant genome rearrangements or expansions. In comparison, the mitochondrial genome of Q. chenii s of moderate size, with a linear chromosome (364,958 bp) and a circular chromosome (53,677 bp), totaling 418,635 bp and a GC content of 45.6%. This dual structure is characteristic of certain Fagaceae species, such as C. mollissima and Q. acutissima. The genome size of Q. chenii is intermediate, falling between the larger genome of L. litseifolius (573,177 bp) and the smaller genome of C. mollissima (388,038 bp) [16, 17]. Its gene density of 57.4% is consistent with that of F. sylvatica (58.2%) and C. mollissima (55.7%), indicating a relatively conserved proportion of functional genes across Fagaceae mitochondrial genomes.

Further insights into the evolutionary dynamics of Q.chenii can be gained through collinearity analysis. The high collinearity percentages between Q. chenii and Q. acutissima (90.92 and 85.50%, respectively) support their close phylogenetic relationship. In contrast, the lower collinearity between F. sylvatica and Q. chenii (35.80 and 42.73%, respectively) suggests significant genomic rearrangements. The adaptation of F. sylvatica to temperate conditions may involve such genomic rearrangements, including the loss or inversion of syntenic regions.

Impact of repetitive sequences and RNA editing on genome function and regulation

In plant mitochondrial genomes, repetitive sequences drive genome rearrangement and play key roles in functional regulation and adaptive evolution [34–37]. For example, repetitive sequences in species like kiwifruit (Actinidia Lindl.), Cuscuta gronovii Willd. ex Schult., and Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl mediate rearrangements that influence adaptation and functional regulation [35, 38, 39]. In Q. chenii, repetitive sequences are concentrated in regions spanning 210–250 kb and 300–340 kb, which may mediate homologous recombination or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) mechanisms [38]. In contrast, species like S. conica exhibit large-scale dispersed repeats, driving frequent recombination events and resulting in mitochondrial genome expansions exceeding 11 Mb [32]. Despite the presence of these repetitive elements, Q. chenii demonstrates remarkable genomic stability. This reflected in the coexistence of highly repetitive regions alongside conserved gene clusters (e.g., rpl16-rps3-rps19), suggesting a balance between dynamic rearrangements and structural conservation. Interestingly, the stability of repetitive sequences in Q. chenii parallels the conserved structure observed in the chloroplast genome within the genus Quercus. Unlike other plant lineages where extensive rearrangements are common, Quercus chloroplast genomes remain relatively stable. In contrast, the chloroplast genomes of Actinidia species, like A. chinensis Planch. and A. arguta (Siebold & Zucc.) Planch. ex Miq., have undergone substantial structural rearrangements at both intraspecific and intrageneric levels [40]. These differences highlight divergent evolutionary strategies, with varying degrees of genomic plasticity and structural conservation across plant taxa. Such comparisons enhance our understanding of how repetitive sequences in plant organellar genomes contribute to both stability and adaptability under distinct selective pressures.

Furthermore, RNA editing in mitochondrial genes plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial function [41]. In Q. chenii, genes encoding NADH dehydrogenase (nad-type) and cytochrome c maturation (ccm-type) proteins exhibit highest frequencies of RNA editing. This editing enhances the functionality of these proteins, which are critical for respiratory chain functionality. Nad-type genes, such as nad4, are essential for complex I, facilitating electrons transfer from NADH to ubiquinone, a crucial step in cellular energy metabolism [42]. Likewise, ccm-type genes, like ccmFn, are vital for cytochrome c maturation and the assembly of complex III. High-frequency RNA editing in these genes likely enhances their protein functionality, maintaining mitochondrial stability under varying metabolic conditions [43–45]. In Q. chenii, the frequent RNA editing observed in ccmFn may support the energy-intensive process of acorn maturation, similar to its role in maize, where disruption of ccmFn impairs complex III assembly and halts seed development [45]. Such precise post-transcriptional regulation is crucial for mitochondrial efficiency and adaption to metabolic demands during acorn development.

Selective pressure and functional evolution of genes in organellar genomes

The mitochondrial genome is essential for plant energy metabolism and environmental adaptation [26]. An analysis of selection pressure in Fagaceae mitochondrial genomes reveals significant conservation of core genes, accompanied by adaptive variations in certain genes. Most genes, such as nad9 and cox1, show strong purifying selection, while genes like nad1 and atp4 exhibit signs of positive selection. Additionally, variation in Ka/Ks ratios among specific mitochondrial genes reveals divergent evolutionary constraints. Genes such as atp6, rpl2, and rps4 exhibit wider Ka/Ks distributions, suggesting relaxed or heterogeneous selection pressures across lineages. Ribosomal protein genes like cox and cob show low Ka/Ks values, consistent with strong purifying selection. In contrast, energy metabolism-related genes, particularly nad1 and nad4, display higher variability, possibly reflecting functional divergence linked to metabolic optimization under stress. Similar trends are observed in chloroplast genome: core photosynthetic genes (rbcL, psbA) are highly conserved [2], while genes like ycf1 and ndhF exhibit higher Ka/Ks values, indicating potential positive selection. Notably, ycf1 has been associated with adaptive responses to environmental stress [46]. The contrasting patterns highlight the distinct evolutionary strategies of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes-one optimizing energy production, the other fine-tuning photosynthesis and stress responses. This underscores the role of functional specialization in shaping organellar genome evolution.

Comparative analysis of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes in Q. chenii further reveals functional synergy and evolutionary divergence. Highly conserved homologous regions, such as psbT and psbC, imply potential coordination in essential metabolic processes. In contrast, genes like ndhD and ndhF exhibit marked divergence indicating the specialized roles of these organelles. For instance, while chloroplast ndhF is integral to photosynthetic electron transport, mitochondria may fulfill analogous functions via alternative metabolic pathways [47, 48]. These functional distinctions are further shaped by horizontal gene transfer (HGT), a process that has profoundly influenced organellar genome architecture in many plant species [49]. In Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai and Cucumis melo L. chloroplast-derived sequences have been integrated into mitochondrial genomes, likely facilitated by repetitive elements that mediate inter-genomic exchange [50]. Similar, events are observed in Apocynaceae species, where mitochondrial genes (sdh3, rps14) have migrated to the nucleus, and chloroplast genes such as rpoC2 and rpl2 have relocated into the mitochondrial genome of Asclepias syriaca L. [51, 52]. These dynamic exchanges, often accompanied by structural rearrangements, contribute to genomic diversity and may drive adaptive evolution [53]. In Q. chenii, observed mismatches and dispersed alignment patterns between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes provide indirect evidence of structural reshuffling or ancient gene transfers.

Conclusion

This study reveals a distinctive bipartite mitochondrial genome structure in Q. chenii, shaped by repeat-mediated rearrangements and reflecting moderate genomic complexity within Fagaceae. Comparative analyses highlight conserved synteny with Q. acutissima and notable divergence from F. sylvatica, indicating lineage-specific evolution. Frequent RNA editing in key genes such as nad4 and ccmF suggests enhanced protein functionality to support mitochondrial energy metabolism and developmental demands. Selection analysis reveals strong purifying pressure on core genes, while variability in nad genes reflects potential adaptive evolution. Comparative insights with chloroplast genomes reveal both conserved and divergent features, underscoring functional specialization and possible historical gene transfers. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the structural and evolutionary dynamics of organellar genomes and their roles in plant adaptation.

Materials and methods

Plant material, extraction of DNA, sequencing, assembly and annotation of the genome

The oak trees (Q. chenii) used in this study were planted on the campus of Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China (N 32°04′, E 118°48′), and their collection was conducted with permission. The plant material used in this study was formally identified by Xuan Li. A voucher specimen (Collection No.: 20240412QCXL) has been deposited in the Herbarium of Nanjing Forestry University, which is publicly accessible. Fresh leaves were collected, on ice, and immediately stored at − 80℃ until further use. Genomic DNA was isolated by the modified method CTAB [54]. In Q. chenii, the increased mismatches and dispersed alignment positions between the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes provide evidence for structural rearrangements or potential gene transfer events. High-quality clean data were obtained after filtering with fastp [55]. For third-generation sequencing, genomic DNA was fragmented, purified, end-repaired, and ligated with adapters. The SMRTbell library was constructed and sequenced on the Oxford Nanopore PromethION platform, with data filtered using filtlong [56].

The oak species mitochondrial genes (CDS, rRNA) were assembled using Minimap2 (v2.1) to align third-generation sequencing data to reference mitochondrial core genes (https://github.com/xul962464/plant_mt_ref_gene) [57]. Sequences longer than 50 bp with high alignment quality were selected as seeds. Raw data were iteratively aligned to these seeds, incorporating sequences with overlaps greater than 1 kb. Canu (v1.8) was used for error correction of the third-generation data [58]. Bowtie2 (v2.3.5.1) aligned second-generation data to corrected sequences [59], and Unicycler (v0.4.8) assembled them (https://github.com/rrwick/Unicycler). Bandage (v0.8.1) was used for visualization and manual adjustment [60]. The mitochondrial genome was annotated by aligning protein-coding genes and rRNA with the published reference mitochondrial genome of Quercus acutissima using BLAST, followed by manual adjustments. tRNA genes were annotated using tRNAscan-SE [61]. Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were identified with the Open Reading Frame Finder, excluding sequences shorter than 102 bp, redundant sequences, and overlaps with known genes; ORFs longer than 300 bp were further annotated against the nr database. RNA editing sites were predicted using PmtREP (http://cloud.genepioneer.com:9929/#/tool/alltool/detail/336).

Repetitive element and relative synonymous codon usage analysis

We utilized the MISA software (v1.0) to predict Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) with the following parameters: 1–10, 2–5, 3–4, 4 − 3, 5 − 3, 6 − 3 [62]. Additionally, we employed Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF; trf409.linux64) with parameters: 2 7 7 80 10 50 2000 -f -d -m, and BLASTn (v2.10.1) with parameters: -word_size 7, evalue 1e-5, to identify tandem repeats and dispersed repetitive sequences, respectively [63]. The results were visualized using Circos (v0.69-5) (http://circos.ca/software/download/). The codon usage bias was calculated using the following method: (the number of occurrences of a specific codon for an amino acid/the total number of occurrences of all codons for that amino acid)/(1/the number of synonymous codons for that amino acid). This can be expressed as (actual codon usage frequency/theoretical codon usage frequency). Unique CDS sequences were filtered and the calculations were performed using a custom Perl script.

Comparative analysis of evolutionary traits across multiple Fagaceae species

Base substitutions that result in amino acid changes are termed nonsynonymous mutations, while those that do not are called synonymous mutations. Nonsynonymous mutations are generally subject to natural selection. The ratio of nonsynonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution rates indicates the type of selection acting on a gene. A ratio greater than 1 suggests positive selection, while a ratio less than 1 indicates purifying selection. We conducted pairwise comparisons of closely related species to extract homologous gene pairs. The homologous gene pairs were aligned using the MAFFT software (v7.427; https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) [64]. Following alignment, the Ka and Ks values for each gene pair were calculated using the KaKs_Calculator software (v2.0; https://sourceforge.net/projects/kakscalculator2/), employing the MLWL method [65]. The Ka/Ks ratios for each gene pair were then computed and visualized using box plots.

Nucleotide diversity (pi) reveals the degree of variation in nucleotide sequences among different species, with highly variable regions potentially serving as molecular markers for population genetics studies. Homologous gene sequences from different species were globally aligned using the MAFFT software (v7.427, --auto mode; https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) [64]. The π value for each gene was then calculated using c.

Genome alignment between assembled sequences and other sequences was performed using the Nucmer software (v4.0.0beta2) with the --maxmatch parameter [66]. The resulting alignments were visualized as dot plots to illustrate genomic similarities and differences.

Analysis of homologous sequences between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes

We used the BLASTN software to compare chloroplast and mitochondrial sequences, setting a threshold of 1e-5 for the e-value [67]. The chloroplast genome sequences of Q. chenii (MF593894.1) as well as the mitochondrial genome sequences of Q. chenii, were obtained from the RefSeq database. Homologous fragments were extracted using the extractseq module from the EMBOSS (v6.6.0.0) package [68]. This analysis aims to clearly identify which coding sequences of the chloroplast genome have been transferred to the mitochondrial genome.

Construction of phylogenetic tree

We selected species from the orders Rosales, Fagales, Cucurbitales, and Fabales. Within the Fagaceae family, we included L. litseifolius, Q. acutissima, C. mollissima, and F. sylvatica to construct a phylogenetic tree. We aligned CDS sequences from different species using MAFFT (v7.427, --auto mode) and concatenated them [69]. The sequences were trimmed with trimAl (v1.4.rev 15, -gt 0.7) [70]. We determined the best-fit model (GTR) using jModelTest (v2.1.10). Finally, we constructed the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using RAxML (v8.2.10) with the GTRGAMMA model and 1000 bootstrap replicates [71].

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

X.L. conceived the design and wrote the manuscript; S.Z performed the data analysis; Y.L. provided edits and suggestions for the language and content of the article; Y.F. and Y.A.E. supervised the project and provided suggestions for the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770699 to Y.F.), the State Scholarship Fund, the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF, Nanjing Forestry University Excellent Doctoral Thesis Fund (2171700124 to X.L), and the Jiangsu Innovation Engineering Fund (KYCX18_0989 to X.L).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository[PQ778323-PQ778324].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Appropriate permissions were obtained for the collection and use of Quercus chenii from the campus of Nanjing Forestry University.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yousry A. El-Kassaby, Email: y.el-kassaby@ubc.ca

Yanming Fang, Email: jwu4@njfu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Manos PS, Hipp AL. An updated infrageneric classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus subgenus Quercus): review of the contribution of phylogenomic data to biogeography and species diversity. Forests. 2021;12(6):786. 10.3390/f12060786. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X, Li YF, Sylvester SP, Zang M, El-Kassaby YA, Fang YM. Evolutionary patterns of nucleotide substitution rates in plastid genomes of Quercus. Ecol Evol. 2021;11(19):13401–14. 10.1002/ece3.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavender-Bares J. Diversification, adaptation, and community assembly of the American Oaks (Quercus), a model clade for integrating ecology and evolution. New Phytol. 2019;221(2):669–92. 10.1111/nph.15450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denk T, Grimm GW, Hipp AL, Bouchal JM, Schulze ED, Simeone MC. Niche evolution in a Northern temperate tree lineage: biogeographical legacies in Cork Oaks (Quercus section Cerris). Ann Bot-London. 2023;131(5):769–87. 10.1093/aob/mcad032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deaconu J, Porojan M, Timar MC, Bedelean B, Campean M. Comparative research on the structure, chemistry, and physical properties of Turkey oak and sessile oak wood. BioResources. 2023;18(3):5724–49. 10.15376/biores.18.3.5724-5749. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suhas E, Shinkaruk S, Pons A. Optimizing the identification of thiols in red wines using new oak-wood accelerated reductive treatment. Food Chem. 2024;437(1):137859. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inácio LG, Bernardino R, Bernardino S, Afonso C, Acorns. From an ancient food to a modern sustainable resource. Sustainability. 2024;16(22):9613. 10.3390/su16229613. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabłowska E, Tańska M. Acorns as a source of valuable compounds for food and medical applications: A review of Quercus species diversity and laboratory studies. Appl Sci. 2024;14(7):2799. 10.3390/app14072799. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pencák T, Dordevic D, Tremlová B. Utilization of oak (genus) tree parts in food industry: a review. Msao international-Journal Food Sci Technol. 2023;13(1):025–30. 10.2478/mjfst-2023-0003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soepadmo E, Van Steenis CGGJ. Fagaceae Flora Malesiana-Series 1 Spermatophyta. 1972;7(1):265–403. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crepet WL, Nixon KC. Earliest megafossil evidence of fagaceae: phylogenetic and biogeographic implications. Am J Bot. 1989;76:842–5. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1989.tb15062.x. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubitzki K. Fagaceae. In: Kubitzki KJ, Rohwer G, Bittrich B, editors. The families and genera of vascular plant volume II. New York: Springer-; 1993. pp. 301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li BY, Huang K, Chen XL, Qin C, Zhang XM. Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of Chloroplast genomes from four species in Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis. Bmc Genomic Data. 2024;25(1):57. 10.1186/s12863-024-01232-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang LL, Li Y, Zheng SS, Kozlowski G, Xu J, Song YG. Complete Chloroplast genomes of four Oaks from the section Cyclobalanopsis improve the phylogenetic analysis and Understanding of evolutionary processes in the genus Quercus. Genes-Basel. 2024;15(2):230. 10.3390/genes15020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Guo H, Zhu JL, Qu K, Chen Y, Guo YT, Ding P, Yang HP, Xu T, Jing Q, et al. Complex physical structure of complete mitochondrial genome of Quercus acutissima (Fagaceae): a significant energy plant. Genes-Basel. 2022;13(8):1321. 10.3390/genes13081321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo HL, Liu Q, Chen Y, Niu HY, Zhao QR, Song H, Pang RD, Huang XL, Zhang JZ, Zhao ZH. Comprehensive assembly and comparative examination of the full mitochondrial genome in Castanea mollissima Blume. Genomics. 2023;115(6):110740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu XY, Tian YQ, Li ZQ, Wu XJ, Xiang ZW, Wang YQ, Li J, Xiao SE. Assembly and characterization analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Lithocarpus litseifolius (Hance) Chun. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2024;1–19. 10.1007/s10722-024-01989-2.

- 18.Cole LW, Guo WH, Mower JP, Palmer JD. High and variable rates of repeat-mediated mitochondrial genome rearrangement in a genus of plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(11):2773–85. 10.1093/molbev/msy176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynn EL, Christensen AC. Repeats of unusual size in plant mitochondrial genomes: identification, incidence and evolution. G3: genes. Genomes Genet. 2019;9(2):549–59. 10.1534/g3.118.200948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou YZ, Zheng RY, Peng YK, Chen JM, Zhu XY, Xie K, Ahmad S, Chen JL, Wang F, Shen ML, et al. The first mitochondrial genome of Melastoma dodecandrum resolved structure evolution in Melastomataceae and micro inversions from inner horizontal gene transfer. Ind Crop Prod. 2023;205:117390. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117390. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao F, Zhao Y, Wang XR, Yang Y. Targeted metabolic and transcriptomic analysis of pinus yunnanensis var. Pygmaea with loss of apical dominance. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44(11):5485–97. 10.3390/cimb44110371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer A, Dotzek J, Walther D, Greiner S. Graph-based models of the Oenothera mitochondrial genome capture the enormous complexity of higher plant mitochondrial DNA organization. NAR Genomics Bioinf. 2022;4(2):lqac027. 10.1093/nargab/lqac027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu XD, Xin YX, Fu HH, Zhou CY, Liu QL, Tang XH, Zou LH, Liu ZJ, Chen SP, Lin WJ, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Castanopsis carlesii and Castanea henryi reveals the rearrangement and size differences of mitochondrial DNA molecules. Bmc Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):988. 10.1186/s12870-024-05618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picard M, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial signal transduction. Cell Metab. 2022;34(11):1620–53. 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barreto P, Koltun A, Nonato J, Yassitepe J, Maia I, Arruda P. Metabolism and signaling of plant mitochondria in adaptation to environmental stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11176. 10.3390/ijms231911176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Møller IM, Rasmusson AG, Van Aken O. Plant mitochondria-past, present and future. Plant J. 2021;108(4):912–59. 10.1111/tpj.15495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaniak-Golik A, Skoneczna A. Mitochondria–nucleus network for genome stability. Free Radical Bio Med. 2015;82:73–104. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vendramin R, Marine J, Leucci E. Non-coding RNA s: the dark side of nuclear-mitochondrial communication. EMBO J. 2017;36(9):1123–33. 10.15252/embj.201695546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mader M, Schroeder H, Schott T, Schöning-Stierand K, Montalvao APL, Liesebach H, Liesebach M, Fussi B, Kersten B. Mitochondrial genome of Fagus sylvatica L. as a source for taxonomic marker development in the fagales. Plants. 2020;9(10):1274. 10.3390/plants9101274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu ZQ, Liao XZ, Zhang XN, Tembrock LR, Broz A. Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria—A review of multichromosomal structuring. J Syst Evol. 2022;60(1):160–8. 10.1111/jse.12655. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Kan SL, Liao XZ, Zhou JW, Tembrock LR, Daniell H, Jin SX, Wu Z. Plant organellar genomes: much done, much more to do. Trends Plant Sci. 2024;29(7):754–69. 10.1016/j.tplants.2023.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Havird JC, Noe GR, Link L, Torres A, Logan DC, Sloan DB, Chicco AJ. Do angiosperms with highly divergent mitochondrial genomes have altered mitochondrial function? Mitochondrion. 2019;49: 1–11. 10.1016/j.mito.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Li J, Cullis C. The multipartite mitochondrial genome of Marama (Tylosema esculentum). Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:787443. 10.3389/fpls.2021.787443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu K, Liu D, Sun LM, Li M, Xia TT, Sun WX, Xia YF. De Novo assembly and comprehensive analysis of the mitochondrial genome of Taxus Wallichiana reveals different repeats mediate recombination to generate multiple conformations. Genomics. 2024;116(5):110900. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2024.110900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang SB, Li DW, Yao XH, Song QW, Wang ZP, Zhang Q, Zhong CH, Liu YF, Huang HW. Evolution and diversification of Kiwifruit mitogenomes through extensive whole-genome rearrangement and mosaic loss of intergenic sequences in a highly variable region. Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(4):1192–206. 10.1093/gbe/evz063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang WL, Zou JN, Yu YJ, Long WX, Li SQ. Repeats in mitochondrial and Chloroplast genomes characterize the ecotypes of the Oryza. Mol Breed. 2021;41(1):1–11. 10.1007/s11032-020-01198-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrieta-Montiel MP, Mackenzie SA. Plant mitochondrial genomes and recombination. In: Kempken F, editor Plant mitochondria. Advances in plant biology, 2011: vol 1. Springer, New York, NY. 10.1007/978-0-387-89781-33.

- 38.Han FC, Bi CW, Zhao YX, Gao M, Wang YD, Chen YC. Unraveling the complex evolutionary features of the Cinnamomum camphora mitochondrial genome. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;43(7):183. 10.1007/s00299-024-03256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Z, Liu W, Qin XH, Xiao Z, Luo Q, Pan DN, Yang H, Liao SF, Chen XY. Unveiling the intricate structural variability induced by repeat-mediated recombination in the complete mitochondrial genome of Cuscuta gronovii willd. Genomics. 2024;110966. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2024.110966. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Gladysheva-Azgari M, Sharko F, Slobodova N, Petrova K, Boulygina E, Tsygankova S, Mitrofanova I. Comparative analysis revealed intrageneric and intraspecific genomic variation in Chloroplast genomes of Actinidia spp. Viridiplantae) Horticulturae. 2023;9(11):1175. 10.3390/horticulturae9111175. Actinidiaceae. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoop WK, Bacman SR, Barrera-Paez JD, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial gene editing. Nat Rev Method Prime. 2023;3(1):19. 10.1038/s43586-023-00215-0. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai HC, Hsieh CH, Hsu CW, Hsu YH, Chien LF. Cloning and organelle expression of bamboo mitochondrial complex I subunits Nad1, Nad2, Nad4, and Nad5 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):4054. 10.3390/ijms23074054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Akella S, Engstler C, Omini JJ, Rodriguez M, Obata T, Carrie C, Cerutti H, Mower JP. Recurrent evolutionary switches of mitochondrial cytochrome c maturation systems in archaeplastida. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1548. 10.1038/s41467-024-45813-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen RR, Wei QH, Liu Y, Li JK, Du XM, Chen Y, Wang JH, Liu YJ. The pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMP601 functions in maize seed development by affecting RNA editing of mitochondrial transcript CcmC. Crop J. 2023;11(5):1368–79. 10.1016/j.cj.2023.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun F, Wang XM, Bonnard G, Shen Y, Xiu ZH, Li XJ, Gao DH, Zhang ZH, Tan BC. Empty pericarp7 encodes a mitochondrial E-subgroup pentatricopeptide repeat protein that is required for CcmFN editing, mitochondrial function and seed development in maize. Plant J. 2015;84(2):283–95. 10.1111/tpj.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seol MA, Kim SS, Lee ES, Nam KH, Chun SJ, Lee JW. Yeast cadmium factor 1-enhanced oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Plant Biotechnol. 2024;51(1):337–43. 10.5010/JPB.2024.51.033.337. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strand DD, D’Andrea L, Bock R. The plastid NAD (P) H dehydrogenase-like complex: structure, function and evolutionary dynamics. Biochem J. 2019;476(19):2743–56. 10.1042/BCJ20190365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martín M, Funk HT, Serrot PH, Poltnigg P, Sabater B. Functional characterization of the thylakoid Ndh complex phosphorylation by site-directed mutations in the NdhF gene. Bba-Bioenergetics. 2009;1787(7):920–8. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aubin E, El Baidouri M, Panaud O. Horizontal gene transfers in plants. Life. 2021;11(8):857. 10.3390/life11080857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui HA, Ding Z, Zhu QL, Wu Y, Qiu BY, Gao P. Comparative analysis of nuclear, chloroplast, and mitochondrial genomes of watermelon and melon provides evidence of gene transfer. Sci Rep-Uk. 2021;11(1):1595. 10.1038/s41598-020-80149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park S, Ruhlman TA, Sabir JSM, Mutwakil MHZ, Baeshen MN, Sabir MJ, Baeshen NA, Jansen RK. Complete sequences of organelle genomes from the medicinal plant Rhazya stricta (Apocynaceae) and contrasting patterns of mitochondrial genome evolution across Asterids. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:405. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Straub SCK, Cronn RC, Edwards C, Fishbein M, Liston A. Horizontal transfer of DNA from the mitochondrial to the plastid genome and its subsequent evolution in milkweeds (apocynaceae). Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5(10):1872–85. 10.1093/gbe/evt140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kejnovsky E, Jedlicka P. Nucleic acids movement and its relation to genome dynamics of repetitive DNA: is cellular and intercellular movement of DNA and RNA molecules related to the evolutionary dynamic genome components? BioEssays. 2022;44(4):e2100242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doyle JJ. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen SF. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using Fastp. Imeta. 2023;2(2):e107. 10.1002/imt2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan Wick. Filtlong. Github. 2017. https://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong. Accessed: 2024 Mar 20.

- 57.Li H. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics. 2021;37(23):4572–4. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):722–36. 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–U54. 10.1038/NMETH.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(20):3350–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Chan PP, Lowe TM. tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1962:1–14. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Sebastian B, Thomas T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;(16):2583–5. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Chen Y, Ye W, Zhang Y, Xu YS. High speed BLASTN: an accelerated megablast search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(16):7762–8. 10.1093/nar/gkv784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80. 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2010;8(1):77–80. 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marçais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. Plos Comput Biol. 2018;14(1):e1005944. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samuel O, Gilles F. MUM&Co: accurate detection of all SV types through whole-genome alignment. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(10):3242–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bleasby LA. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–7. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma KI, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid 506 multiple sequence alignment based on fast fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;50730(14):3059–66. 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. TrimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15)1972– 1973. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Alexandros S. Bioinformatics. 2014;91312–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Alexandros S. Bioinformatics. 2014;91312–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository[PQ778323-PQ778324].