Abstract

Background & aims

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a common hip disorder characterized by abnormal contact between the femoral head and acetabulum, leading to pain, restricted mobility, and potential osteoarthritis. Despite its clinical significance, the role of periarticular muscle alterations in FAI progression remains controversial. This study aimed to systematically evaluate hip muscle strength alterations and their clinical implications in FAI through meta-analysis.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to PRISMA and AMSTAR guidelines, analyzing five cross-sectional studies (118 FAI patients, 89 controls) to compare hip muscle strength (flexion, extension, abduction/adduction) and functional outcomes (e.g., iHOT-33, HAGOS). Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Results

FAI patients exhibited significantly reduced hip flexion (− 0.338 Nm/kg) and extension (− 0.379 Nm/kg) strength versus controls, with compensatory neuromuscular adaptations (e.g., preferential biceps femoris recruitment) and altered kinetic chains. Core muscle weakness and inconsistent fatigue patterns were also observed. Secondary outcomes lacked sufficient data for meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Muscle deficits in FAI are multifactorial, involving strength loss, maladaptive coordination, and kinetic chain disruptions. Targeted rehabilitation should integrate hip-centric and core stabilization exercises, but longitudinal studies are needed to validate therapeutic efficacy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13018-025-06135-x.

Introduction

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) is a common hip disorder among young and middle-aged populations, typically caused by anatomical variations in the hip joint that lead to abnormal contact between the femoral head and acetabulum [1]. FAI is closely associated with sports injuries, congenital hip dysplasia, and other factors. Patients often present with limited hip mobility and periarticular pain. As the condition progresses, degenerative changes may occur, potentially leading to osteoarthritis. In severe cases, surgical intervention is required to improve quality of life [2]. However, some individuals exhibit radiographic evidence of structural abnormalities without apparent clinical symptoms [3].

Diagnosis of FAI relies on imaging modalities such as X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with classification based on morphological features of the femoral head and acetabulum. The most common subtypes include pincer-type, cam-type, and mixed-type FAI [4]. Different FAI subtypes variably impair hip joint function, and clinical manifestations may differ significantly among individuals. While some patients exhibit only radiographic abnormalities without overt symptoms, most experience varying degrees of pain and restricted mobility, which may ultimately compromise quality of life [4].

The role of muscles in stabilizing and protecting the hip joint is well-established. Research indicates that patients with FAI frequently exhibit weakness in periarticular muscles [5], particularly diminished function of key muscle groups such as the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius [6]. Additionally, core muscle weakness (e.g., iliopsoas, psoas major) is commonly observed in FAI patients [7]. Muscle strength deficits and restricted mobility often lead to inadequate strength training, which may further contribute to muscle atrophy, exacerbating hip joint instability. This creates a vicious cycle, ultimately accelerating functional deterioration of the joint.

Although current research confirms impaired muscle strength in FAI patients, the functional role and biomechanical mechanisms of periarticular muscles remain controversial. Some studies suggest these muscles may provide stabilizing effects that potentially slow disease progression [8, 9], while others argue that muscular alterations primarily represent compensatory changes secondary to pathology, with no definitive evidence establishing their causative role in FAI development [6, 10]. It is noteworthy that current studies exhibit significant disparities in the following aspects: First, the majority of research focuses on changes in muscle mass or clinical outcomes (e.g., pain, range of motion) before and after treatment (such as hip arthroplasty or hip arthroscopy) in patients with FAI, yet largely overlooks baseline muscle strength comparisons between FAI patients and healthy populations [11–16]. Second, existing meta-analyses primarily evaluate surgical efficacy but lack systematic integration of functional assessments of periarticular hip muscles in FAI patients. We contend that muscle function evaluation holds critical clinical value, as it not only provides objective criteria for surgical indications but also partially predicts functional recovery trajectories in FAI patients. Furthermore, although Albertoni et al. observed differences in joint range of motion between FAI patients and healthy controls, their study design did not quantitatively analyze muscle characteristics between the two cohorts [17]. Therefore, investigating the mechanistic role of muscle strength training in symptom alleviation and disease course modulation for FAI patients, along with establishing rehabilitation strategies centered on muscle function preservation (encompassing both perioperative and non-operative populations), has emerged as a pivotal direction in contemporary clinical research.

To better inform clinical decision-making, particularly for surgeons evaluating patient conditions and optimizing treatment outcomes, we conducted this systematic review. By analyzing muscle strength characteristics in FAI patients, this study aims to provide robust clinical evidence that emphasizes the role of musculature in therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, we explore the potential of targeted interventions such as muscle strengthening exercises to improve patient prognosis.

Materials and methods

This systematic review adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines and the AMSTAR (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews) checklist. The study protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID: CRD420251050502).

Ethics and dissemination

No IRB/ethics committee approval was sought for this systematic review and meta-analysis, as it did not involve direct interaction with human subjects or collection of original data. Additionally, patient consent procedures were not applicable since this study exclusively utilized published data from previously conducted research. Consequently, ethical considerations regarding patient consent and IRB approval were not relevant to this meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion Criteria: (1) Demographic Characteristics: Age: Reported as mean ± standard deviation, with an average age range of 18–50 years (covering the primary FAI patient population); Sex: Clearly reported sex ratio (male/female percentage); Surgical History: Patients with prior hip surgeries (including arthroscopic or open procedures) were excluded. (2) Diagnostic criteria: Patients clinically diagnosed with FAI, specifically including: Cam-type FAI; Pincer-type FAI; Mixed-type FAI. (3) Study type: Prospective and observational studies with clear designs that provide relevant muscle strength and biomechanical data, with clearly defined sample sizes for both FAI patients and healthy control groups. (4) Outcome measures: Studies must report explicit lower-extremity muscle strength data, including: - Primary outcomes: Isometric muscle strength (hip flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, knee flexion/extension); Secondary outcomes: International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33), Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS). Exclusion Criteria: (1) Language restriction: Non-English publications (excluding translated literature). (2) Duplicate publications: Redundant reports of the same study or datasets. (3) Inaccessible data: Articles without full-text availability or with only abstracts, or incomplete data preventing valid analysis. (4) Incomplete data: Studies missing key metrics (e.g., muscle strength) or with insufficient data for evaluation. (5) Poor study quality: Studies with low methodological rigor, unclear protocols, or inadequate sample sizes (lacking statistical power).

Search strategy

Computerized searches will be conducted across the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PubMed, and Embase databases, covering records from each database’s inception through March 2025. Manual searches of reference lists from included studies will supplement the electronic retrieval. The search strategy incorporates both controlled vocabulary (MeSH/Emtree terms) and free-text terms, with the complete search syntax detailed in Supplementary File.

Data collection and analysis

Two investigators independently performed literature screening and data extraction based on the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria, followed by cross-verification. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third investigator for consensus decision-making. After initial title/abstract screening, potentially eligible studies underwent full-text assessment. The extraction process captured: (1) investigator(s), (2) publication year, (3) patient demographics (age, sex), (4) sample size, (5) study design, and (6) outcome measures.

Assessment of risk of Bias

Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions, with consultation of a third author when necessary. Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies [18] and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tool for cross-sectional studies [19]. The NOS provides a systematic assessment of three core dimensions in observational studies (selection bias, comparability between groups, and exposure/outcome measurement), while the JBI checklist was specifically developed for cross-sectional study designs to supplement methodological elements not covered by NOS (such as control of confounding factors and appropriateness of statistical methods). The NOS evaluates studies across three domains (selection, comparability, and outcome/exposure determination) through 9 scoring items. With the response rate item excluded, the total possible score was 8 points. The JBI tool assessed study quality across 12 items examining: study population, sample size, statistical methods, and outcome evaluation. Each item was rated as “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” or “not applicable.”

Data synthesis

For this meta-analysis, all statistical analyses of continuous outcomes were performed using STATA 18.0 software. Weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using χ² tests and I² statistics. A fixed-effects model was applied when heterogeneity was low (P > 0.1 and I² < 50%); otherwise, a random-effects model was employed. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity. A threshold of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection

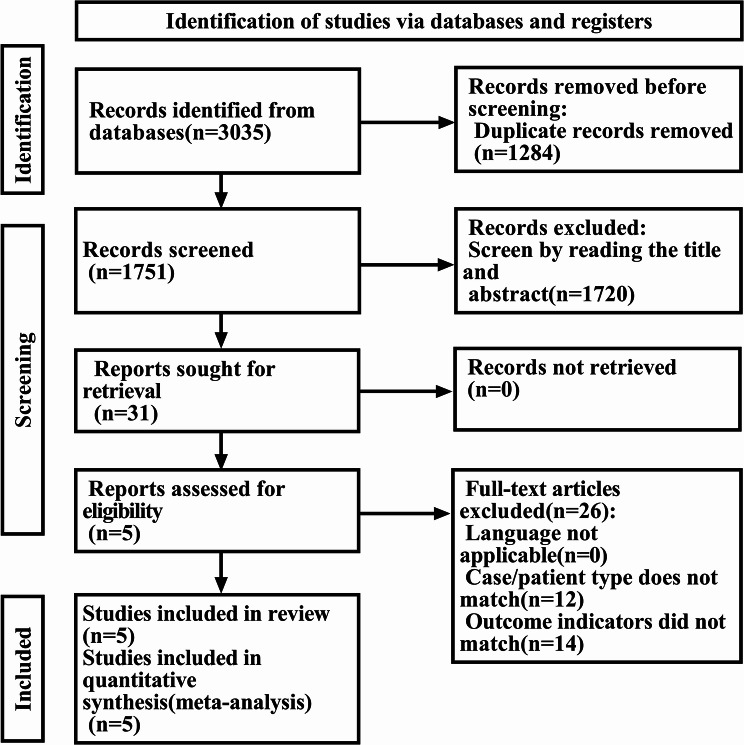

The initial database search yielded 3,035 potentially relevant articles. After removing duplicates using EndNote 20 software and screening titles and abstracts, 31 articles were selected for full-text review. Ultimately, 5 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Screening flowchart

Study characteristics

A total of five studies were included in this analysis, all of which were observational cross-sectional studies. The baseline characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Published Time | Age (FAI/Control) | M: F (FAI/Control) | Sample Size (FAI/Control) | Research Type | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catelli et al. | 2018 | 38.5 ± 8.0/32.8 ± 7.0 | 14:2/16:2 | 16/18 | Cross-sectional Observational Study | Hip flexion strength; Hip extension strength; Hip abduction strength; Knee flexion strength; HOOS | |

| Diamond et al. | 2015 | 24.7 ± 4.9/27.1 ± 4.5 | 11:4/10:4 | 15/14 | Cross-sectional Observational Study | Hip flexion strength; Hip extension strength; Hip abduction strength; Hip adduction strength; ihot-33; HAGOS | |

| Halliwell et al. | 2024 | 35.0 ± 11.0/32.0 ± 6.0 | 3:4/2:5 | 7/7 | Cross-sectional Observational Study | Hip flexion strength; Hip extension strength; Knee flexion strength; Knee extension strength; ihot-33; HAGOS; HOOS | |

| Kierkegaard et al. | 2017 | 36.0 ± 9.0/36.0 ± 9.0 | 22:38/12:18 | 60/30 | Cross-sectional Observational Study | Hip flexion strength; Hip extension strength; HAGOS | |

| Frasson et al. | 2018 | 28.0 ± 6.0/27.0 ± 5.0 | 20:0/20:0 | 20/20 | Cross-sectional Observational Study | Hip flexion strength; Hip extension strength; Hip abduction strength; Hip adduction strength; ihot-33 |

HOOS, Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; ihot-33, International Hip Outcome Tool-33; HAGOS, Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score

Clinical outcomes

Table 1 presents the comparative characteristics of body metrics between FAI patients and healthy controls. The pooled analysis included 118 FAI patients and 89 healthy controls, with notable sex ratio differences between groups. All cross-sectional studies incorporated in the meta-analysis demonstrated low-to-moderate risk of bias upon quality assessment. The NOS evaluation showed that the included studies scored 7–8 points, indicating overall good methodological quality. The primary limitations were observed in the gender distribution between case and control groups, with only one study (20%) demonstrating satisfactory comparability. The JBI assessment revealed that all five studies met medium-to-high quality standards, with the most common methodological flaw being inadequate description of participant recruitment procedures. (See supplementary file)

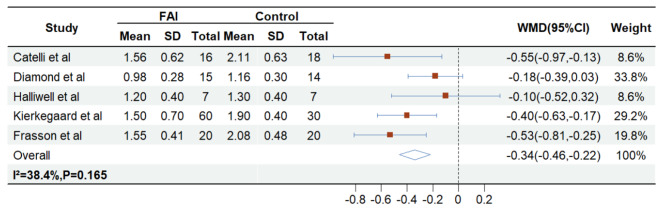

Supplementary File presents pooled estimates of effect sizes (WMD with 95% CIs) comparing FAI patients versus healthy controls: Hip flexion strength (-0.338 Nm/kg, 5 studies [3, 6, 20–22]; Fig. 2), Hip extension strength (-0.379 Nm/kg, 5 studies [3, 6, 20–22]; Fig. 3), Hip abduction strength (-0.224 Nm/kg, 3 studies [3, 20, 21]; Fig. 4), Hip adduction strength (-0.381 Nm/kg, 2 studies [20, 21]; Supplementary File), Knee flexion strength (-0.051 Nm/kg, 2 studies [3, 6]; Supplementary File), with only knee extension strength reported in 1 study [6]. For secondary outcomes (HAGOS, HOOS and iHOT-33), meta-analysis was precluded due to inconsistent definitions across studies and absence of control groups (see Supplementary File for details on missing secondary outcome data).

Fig. 2.

The impact of FAI and control group on the Hip flexion strength

Fig. 3.

The impact of FAI and control group on the Hip extension strength

Fig. 4.

The impact of FAI and control group on the Hip abduction strength

Sensitivity analysis

Significant heterogeneity was observed in hip extension strength analysis, prompting sensitivity analyses to evaluate result robustness. Using a leave-one-out approach, the pooled effect size remained consistently negative across all iterations, ranging from − 0.442 (excluding Catelli et al., 2018) to -0.269 (excluding Frasson et al., 2018), maintaining directional consistency with the original pooled estimate (-0.379, 95% CI: -0.667 to -0.091). All analyses except the exclusion of Kierkegaard et al. (2017) demonstrated 95% CIs excluding zero, confirming overall robustness. Notably, Kierkegaard et al.‘s study (FAI = 60, controls = 30) carried disproportionate weight in random-effects models due to its larger sample size, explaining its critical influence on effect stability. For hip adduction strength and knee flexion strength, the limited number of included studies (n = 2 each) precluded meaningful sensitivity analyses and reduced statistical reliability, underscoring the need for additional evidence to validate these outcomes.

Publication Bias

Although the small number of included studies (n = 5) precluded formal assessment (e.g., funnel plot), the possibility of publication bias remains. Small studies with negative results may have gone unpublished, potentially leading to overrepresentation of positive findings regarding muscle weakness in FAI patients and consequent overestimation of effect sizes. Future systematic reviews should incorporate grey literature and trial registry data to mitigate this bias.

Disscussion

The five cross-sectional studies [3, 6, 20–22] included in this systematic review demonstrated that FAI patients exhibit significantly lower peak isometric torque in periarticular hip muscles (particularly hip flexors and extensors) compared to healthy controls. These muscles play critical roles in maintaining joint stability and preventing pelvic tilt. Malloy et al. [23]found that FAI patients showed reduced hip external/internal rotation and flexion strength, with markedly limited pelvic mobility in both sagittal and coronal planes during single-leg squats, indicating restricted hip motion and insufficient muscular stabilization during increased pelvic movement—though this study did not assess hip abductors. Beyond periarticular hip muscle deficits, FAI patients also displayed notable core muscle weakness. Core strength, which correlates with pelvic positioning and spinal stability [24], is often compromised in FAI as patients adopt compensatory pelvic anterior tilt to offload the hip, increasing lumbar strain and potentially leading to rigid lumbosacral mechanics [25]. González et al. [26]identified impaired posterior chain endurance (e.g., iliopsoas weakness) during trunk isometric tests (flexion/extension/lateral support), while evidence supports the efficacy of combined lower-extremity and core strengthening in conservative management [27]. Although our analysis did not reveal significant knee muscle alterations, the biomechanical coupling between hip and knee muscles remains clinically relevant for cross-joint stabilization [28]. Consequently, rehabilitation should integrate not only hip-centric eccentric training but also closed-chain core-pelvis-knee exercises to address this kinetic interdependence [29].

Current evidence demonstrates inconsistent patterns of muscle strength alterations in FAI patients compared to femoroacetabular deformity (FAD) and healthy controls, particularly regarding specific muscle groups. For hip flexors/extensors: Zhang et al. [30] reported reduced hip flexion strength in FAI versus both FAD and controls, with no extension differences, whereas Catelli et al. [3]found FAI had weaker flexion than both groups while FAD showed superior extension strength. A muscle-specific analysis revealed distinct adaptation patterns: healthy controls exhibited greater semimembranosus strength, while FAD patients demonstrated weaker biceps femoris but stronger gluteus medius versus FAI [10]. This suggests asynchronous changes in synergistic muscles (e.g., hamstrings) during FAI progression. These findings suggest asynchronous alterations in synergistic muscle groups (e.g., hamstrings) during FAI progression. Specifically, while current evidence indicates that global hamstring dysfunction increases FAI risk [31], comparative analysis revealed differential hamstring manifestations between FAI and FAD patients (with semimembranosus weakness but relative preservation of biceps femoris). These differential manifestations may stem from the lack of standardized strength normalization (e.g., body weight-adjusted) and the heterogeneity of FAI subtypes. Furthermore, the differential activation patterns between semimembranosus and biceps femoris warrant further investigation, including standardized strength assessment protocols for subtypes and combined EMG temporal analysis to determine whether biceps femoris exhibits selective recruitment as an adaptive compensatory mechanism.

FAI patients exhibit not only muscle weakness but also fundamental reorganization of neuromuscular control patterns. Diamond et al. [32]demonstrated through EMG coactivation analysis that FAI patients show higher movement stereotypy (Variance Accounted For, VAF: 96.0% vs. 94.8%), indicating central nervous system adoption of simplified motor control strategies through reduced muscle activation variability. During symptomatic-direction movements, FAI patients preferentially recruit deep stabilizer muscles as pain-avoidance adaptations, whereas healthy controls maintain task-adaptive activation patterns. This maladaptive reorganization may create a vicious cycle: impaired muscular coordination alters load distribution across joints, while chronic compensatory patterns further suppress physiological muscle activation. Furthermore, a study measuring muscle activation during squatting demonstrated smaller differences in activation levels between gluteus maximus and obturator internus in FAI patients compared to controls [33]. Although these findings suggest altered movement strategies in FAI, the causal relationship with symptom progression remains unclear due to the lack of pre-symptomatic EMG data and potential confounding effects such as pain inhibition.

Muscle fatigue characteristics serve as crucial functional biomarkers, yet the fatigue mechanisms of periarticular hip muscles remain poorly understood. Controlled experiments [34]revealed a paradoxical finding: while both isometric (-21%) and isokinetic (-16%) testing confirmed significantly reduced hip flexion strength in FAI patients, their fatigue rates (0.017 ± 0.011 vs. 0.020 ± 0.009 N·m·kg⁻¹·s⁻¹) and EMG (electromyography) fatigue indices—RMS (Root Mean Square, amplitude-domain measure of muscle activation) and MDF (Median Frequency, spectral shift indicator of metabolic fatigue)—showed no difference versus healthy controls. This dissociation suggests that systemic fatigue from perceived dysfunction may mask true muscular fatigue. However, critical limitations—including exclusion of key hip flexors (iliopsoas) and non-standardized contraction intensities—preclude definitive conclusions about fatigue kinetics in periarticular muscles.

FAI patients demonstrate location-specific biomechanical compensation patterns. During anterior impingement (abnormal contact between femoral head-neck junction and acetabular rim), prospective motion analysis [10] revealed significantly reduced posterior hip contact forces in FAI patients versus both FAD groups (difference phases: 0–7%/15–26%/79–100% of squat cycle) and healthy controls (0–7%/72–82%). Conversely, gait analysis reveals distinct adaptations: Ng et al. [7]documented slower cadence, shorter stride length, and markedly reduced iliopsoas complex strength in FAI patients during walking, leading to decreased anterosuperomedial joint contact forces. However, during swing phase with contralateral foot strike and hip extension, anterosuperior contact forces increase. The structurally coupled iliopsoas complex normally resists anterior subluxation [35]. Their weakening may compromise anterosuperior acetabular load distribution and reduce resultant joint reaction forces. Furthermore, periarticular muscles in FAI patients can stabilize the hip joint through capsular contraction to mitigate impact loading [36]. The relationship between muscle weakness and altered contact mechanics in FAI warrants further biomechanical investigation, with high-density EMG providing valuable insights into task-dependent variations in dynamic muscle recruitment patterns.

FAI patients exhibit altered lower limb kinetic chains that disrupt force transmission patterns, leading to abnormal knee loading. Spiker et al. [37]demonstrated increased knee valgus angles during fast walking in FAI patients, potentially compensating for elevated internal rotation moments. This aligns with established evidence showing that impaired hip internal rotation (FAI patients: 23.4°±7.6° vs. healthy controls: 30.4°±10.4°) significantly increases Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury risk [38]. These findings support an association between hip joint dysfunction and altered knee joint loading. Prospective longitudinal studies combined with hip-knee biomechanical modeling are warranted to establish causal relationships and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Understanding muscle strength alterations in FAI patients is critical for optimizing conservative management and rehabilitation strategies. Casartelli et al. [39]demonstrated that progressive exercise therapy—incorporating graded hip strengthening and core stabilization—achieved clinical improvement in 50% of participants, though severe cam-type FAI patients showed minimal pain relief. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) focusing on female FAI patients confirmed that trunk stabilization training not only enhanced hip abductor function but also improved 8-week functional outcomes when combined with lower extremity exercises. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive, multi-parameter predictive models (integrating morphological, kinetic, and EMG data) to stratify disease severity and personalize treatment plans [27].

Significant heterogeneity was observed in hip extension strength, warranting comprehensive investigation from both clinical and methodological perspectives. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the study by Kierkegaard et al. [22] contributed substantially to this heterogeneity, likely due to its larger sample size (FAI = 60, controls = 30). The 2:1 case-control design introduced selection bias not present in other studies. Beyond sample size imbalance, we identified several potential sources of heterogeneity. First, variations in gender distribution across studies may affect baseline muscle strength and compensatory capacity in FAI. Second, differences in disease severity and diagnostic criteria—including the α-angle threshold (ranging from 52° to 68°) and FAI subtype distribution—could lead to varying degrees of muscular impairment among patient cohorts. Despite this heterogeneity, all studies consistently demonstrated reduced periarticular hip muscle strength in FAI patients. Future research should standardize diagnostic criteria to enhance result comparability.

Limitation

As a systematic review and meta-analysis, this study was constrained by the quantity and quality of available literature, leading to several key limitations: (1) Incomplete reporting of periarticular muscle strength (e.g., hip internal/external rotator data were missing in 80% of studies) significantly reduced statistical power; (2) Among the included studies, each key functional outcome measure (HOOS, iHOT-33, and HAGOS) was fully reported in only one distinct study, with additional variability observed in assessment protocols across these studies; (3) Marked heterogeneity in hip extension strength analysis emerged due to imbalanced sample sizes, unequal sex distribution, and inconsistent diagnostic criteria (α-angle thresholds ranging 52°-68°). Importantly, the lack of comparative muscle mass data between FAI patients and healthy controls - a crucial factor for evaluating compensatory adaptations - coupled with the exclusive use of cross-sectional designs in all included studies, precludes causal inferences between muscle function changes and FAI progression. To address these gaps, future research should prioritize prospective cohort studies employing standardized protocols to simultaneously track dynamic changes in both muscle strength and mass.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Wen Zhang performed the research, Wen Zhang and Lei Chen analysed the data and wrote the paper, Lei Chen prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4; Table 1.Peijian Tong designed the research study.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.82274547, Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.LD22C060002, Zhejiang Provincial Project of Administration of Chinese Medicine No.2023ZL369, 2024 Zhejiang Chinese Medicine University Cultivation Plan for Top Innovative Talents of Post graduates (No: 2024YJSBJ011) and the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhejiang Province (No: GZY-ZJ-KJ-23064).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Authorship declaration

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and all authors agree with the publication of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wen Zhang and Lei Chen contributed equally as first authors.

References

- 1.Agricola R, Weinans H. What is femoroacetabular impingement? Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(4):196–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bredella MA, Ulbrich EJ, Stoller DW, et al. Femoroacetabular Impingement Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2013;21(1):45–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catelli DS, Kowalski E, Beaulé PE, et al. Asymptomatic participants with a femoroacetabular deformity demonstrate stronger hip extensors and greater pelvis mobility during the deep squat task. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(7):2325967118782484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmaranzer F, Kheterpal AB, Bredella MA. Best practices: hip femoroacetabular impingement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216(3):585–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-de-la-Flor Á, Valera-Calero JA, García-Fernández P et al. Clinical presentation differences among four subtypes of femoroacetabular impingement: A Case-Control study 2024, 104 (4):179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Halliwell C, Rutherford D, Moreside J et al. Altered hip flexor and extensor activation during progressive inclined walking in individuals with femoroacetabular impingement. Syndrome J Sport Rehabil, 2024, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ng KC, Mantovani G, Modenese L, et al. Altered walking and muscle patterns reduce hip contact forces in individuals with symptomatic cam femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(11):2615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright AA, Hegedus EJ, Taylor JB et al. Non-operative management of femoroacetabular impingement: A prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial pilot study 2016, 19 (9):716–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Terrell SL, Olson GE, Lynch J. Therapeutic exercise approaches to nonoperative and postoperative management of femoroacetabular impingement. Syndrome J Athl Train. 2021;56(1):31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catelli DS, Kowalski E, Beaulé PE et al. Muscle and hip contact forces in asymptomatic men with cam morphology during deep squat frontiers in sports and active living, 2021, 3 716626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Migliorini F, Baroncini A, Eschweiler J et al. Return to sport after arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement surgeon, 2023, 21 (1):21–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Baroncini A, et al. Revision surgery and progression to total hip arthroplasty after surgical correction of femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(4):1146–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migliorini F, Liu Y, Eschweiler J et al. Increased range of motion but otherwise similar clinical outcome of arthroscopy over open osteoplasty for femoroacetabular impingement at midterm follow-up: A systematic review 2022, 20 (3):194–208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Migliorini F, Liu Y, Catalano G et al. Medium-term results of arthroscopic treatment for femoroacetabular impingement 2021, 138 (1):68–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lucenti L, Maffulli N, Bardazzi T, et al. Return to sport following arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(17):5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Bell A, et al. Midterm results after arthroscopic femoral neck osteoplasty combined with labral debridement for cam type femoroacetabular impingement in active adults. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albertoni DB, Gianola S, Bargeri S, et al. Does femoroacetabular impingement syndrome affect range of motion? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br Med Bull. 2023;145(1):45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan Z, Lockwood C, Munn Z, et al. The updated Joanna Briggs Institute model of Evidence-Based healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2019;17(1):58–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond LE, Wrigley TV, Hinman RS, et al. Isometric and isokinetic hip strength and agonist/antagonist ratios in symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(9):696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frasson VB, Vaz MA, Morales AB et al. Hip muscle weakness and reduced joint range of motion in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a case-control study 2020, 24 (1):39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kierkegaard S, Mechlenburg I, Lund B, et al. Impaired hip muscle strength in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(12):1062–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malloy P, Wichman DM, Garcia F, et al. Impaired lower extremity biomechanics, hip external rotation muscle weakness, and proximal femoral morphology predict impaired Single-Leg squat performance in people with FAI syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(11):2984–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim B, Yim J. Core stability and hip exercises improve physical function and activity in patients with Non-Specific low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;251(3):193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fader RR, Tao MA, Gaudiani MA et al. The role of lumbar lordosis and pelvic sagittal balance in femoroacetabular impingement bone joint J, 2018, 100–b (10):1275–1279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.González D E L A F Á, García-Arrabé M, Fernández-Pardo T, et al. Clinical presentation of anterior pelvic Tilt and trunk muscle endurance among patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2024;60(6):1027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoyama M, Ohnishi Y, Utsunomiya H, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing Conservative treatment with trunk stabilization exercise to standard hip muscle exercise for treating femoroacetabular impingement: A pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. 2019;29(4):267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez A, Lenz A, Thelen D. Electrical stimulation of the rectus femoris during pre-swing diminishes hip and knee flexion during the swing phase of normal gait. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2010;18(5):523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes D, Ribeiro DC, Ferreira T et al. Knee and hip dynamic muscle strength in individuals with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome scheduled for hip arthroscopy: A case-control study clinical biomechanics, 2022, 93105584. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Zhang J, Kim Y, Choi M et al. Characteristics of Biomechanical and physical function according to symptomatic and asymptomatic acetabular impingement syndrome in young adults healthcare, 2022, 10 (8):1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kraeutler MJ, Fioravanti MJ, Goodrich JA et al. Increased prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement in patients with proximal hamstring tendon injuries arthroscopy, 2019, 35 (5):1396–402. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Diamond LE, Van den Hoorn W, Bennell KL, et al. Coordination of deep hip muscle activity is altered in symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(7):1494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diamond LE, van den Hoorn W, Bennell KL et al. Deep hip muscle activation during squatting in femoroacetabular impingement syndrome clin biomech (Bristol), 2019, 69 141–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Casartelli NC, Leunig M, Item-Glatthorn JF et al. Hip flexor muscle fatigue in patients with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement int orthop, 2012, 36 (5):967–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Lifshitz L, Bar Sela S, Gal N, et al. Iliopsoas the hidden muscle: anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2020;19(6):235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrenson PR, Vicenzino BT, Hodges PW, et al. Pericapsular hip muscle activity in people with and without femoroacetabular impingement. Comparison Dynamic Tasks Phys Therapy Sport. 2020;45:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiker AM, Kraszewski AP, Maak TG, et al. Dynamic Assess Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome Hips Arthrosc. 2022;38(2):404–e4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VandenBerg C, Crawford EA, Sibilsky Enselman E et al. Restricted hip rotation is correlated with an increased risk for anterior cruciate ligament injury 2017, 33 (2):326–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Casartelli NC, Bizzini M, Maffiuletti NA, et al. Exercise therapy for the management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: preliminary results of clinical responsiveness. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(8):1074–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.