Abstract

Pathophysiological changes associated with anthrax lethal toxin included loss of plasma proteins, decreased platelet count, slower clotting times, fibrin deposits in tissue sections, and gross and histopathological evidence of hemorrhage. These findings suggest that blood vessel leakage and hemorrhage lead to disseminating intravascular coagulation and/or circulatory shock as an underlying pathophysiological mechanism.

Bacillus anthracis produces protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF), and lethal factor (LF), which are toxins that work in binary combinations. Since lethality can be induced by LF and PA (LeTx) independent of EF, the pathophysiology associated with LeTx is of particular interest. LeTx has been found to result in circulatory shock and death (5), but the changes that lead to these events have not been fully characterized.

Pathogen-free male and female, 4- to 12-week-old CAST/EiJ and C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine), which have different sensitivities to LeTx (11), and 3- to 5-week-old F1 (parents, CAST/EiJ × C57BL/6J), F2 CAST/Ei (parents, F1 × CAST/EiJ), and F2 C57BL/6 (possible twi carriers; parents, F1 × C57BL/6J) mice were used for these studies, which were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Recombinant PA and LF (List Biological Laboratories, Inc., Campbell, CA) were resuspended in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH ∼7.4, and stored in BSA-precoated tubes at −20°C. Purity of toxins was established via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels by the manufacturer. LeTx (PA, 4 μg/g of body weight, and LF, 2 μg/g) was administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, and mice were observed for clinical signs. The dosage was approximately 5 50% lethal doses based on Price et al. (12). Once clinical signs that preceded death by ∼2 to 3 h were identified, LeTx animals displaying these signs and matched control animals (i.p. injection of saline) were anesthetized via halothane inhalation. Blood was drawn via cardiac puncture and collected in serum tubes or in sodium citrate tubes for plasma isolation. The Veterinary Laboratory Resources, Inc. (Overland Park, Kansas), processed sera for chemistry panels using a Bayer Advia 1650 system (Bayer Diagnostics, Terrytown, New York) and plasma for coagulation panels using an STA Compact system (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, N.J.).

In animals that were sacrificed or died, the major organs were examined in situ, harvested, placed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections, 8 μm thick, were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical staining of fibrinogen, which cross-reacts with fibrin, was performed as follows: deparaffinization; 3% H2O2, 10 min; Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.05% Tween (TBST); 0.1% proteinase K in TBS, 10 min; TBST; 1:1,000 rabbit anti-human fibrinogen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), which cross-reacts with mouse fibrinogen, overnight at 4°C; TBST, LSAB+ (Dako), and DAB+ (Dako), 10 min.

Total glutathione was measured in the lungs and livers of LeTx C57BL/6J mice that were sacrificed when they displayed dyspnea and severe lethargy and in control (saline) C57BL/6J mice sacrificed at matching times. The assay was performed as previously described (4).

LeTx animals showed severe lethargy and weakness, hunched posture, and/or severe dyspnea within ∼2 to 3 h prior to death. Less common clinical signs included ataxia, rear limb paraplegia, bloat, and pale extremities. CAST/EiJ mice died at 26.7 h ± 2.0 (mean ± standard error [SE]; median, 24.9 h) with 1/6 surviving, and C57BL/6J died at 60.9 h ± 14.1 (median, 51.9 h) with 2/5 surviving (Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.036 for CAST/EiJ versus C57BL/6J LeTx mice that died). All F1 mice succumbed to LeTx (58.2 ± 8.2 h; n = 5), while 4/5 F2 CAST/Ei animals succumbed to LeTx (31.3 ± 1.9 h), and 2/3 F2 C57BL/6 mice survived, with the third animal dying at ∼78 h.

Blood panels revealed hypoglycemia, elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypoglobulinemia in LeTx C57BL/6J mice (58.6 ± 6.7 h, mean time of advance clinical signs ± SE) compared to vehicle-injected C57BL/6J mice (Table 1). There were no clear differences in the chemistry profile between LeTx (24.4 ± 1.2 h) and control CAST/EiJ mice.

TABLE 1.

Clinical chemistry measurementsa

| Chemistry | Control C57BL/6J

|

LeTx C57BL/6J

|

P valueb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B10 | B12 | B14 | B16 | Median | B9 | B11 | B13 | B15 | Median | ||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 236 | 218 | 161 | 281 | 227 | 116 | 55 | 112 | 177 | 114 | 0.0571 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 31 | 33 | 28 | 25 | 29.5 | 37 | 44 | 70 | 65 | 54.5 | 0.0286 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.2286 |

| Sodium (mg/dl) | NPc | NP | 138 | 150 | 144 | 157 | 156 | 151 | 140 | 153.5 | 0.2667 |

| Chloride (mg/dl) | NP | NP | 92 | 107 | 99.5 | 124 | 120 | 120 | 97 | 120 | 0.2667 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 10.4 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 10.25 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.55 | 0.0286 |

| Adjusted calcium (mg/dl)d | 10.8 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 10.75 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 0.7143 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | NP | 11.6 | 15 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 12.1 | 15 | 10.25 | 0.7143 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 5 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 2.35 | 0.0286 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.1 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.0571 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 84 | 68 | 127 | 60 | 76 | 31 | 57 | 44 | 81 | 50.5 | 0.1143 |

| Globulin (g/dl) | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.85 | 0.0286 |

| Amylase (U/liter) | 3,030 | 4,907 | 13 | 4,333 | 3,681.5 | 5,596 | 30,274 | NP | 7 | 5,596 | 0.6286 |

| Lipase (U/liter) | NP | NP | 403 | 225 | 314 | 144 | 9450 | 418 | 176 | 297 | 1.000 |

Data for liver enzymes and potassium could not be reported due to mild to moderate hemolysis of the majority of the samples.

Formulated using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test.

NP, tests not performed due to limited sample volume.

Calcium is adjusted to take into account loss due to the protein-bound fraction associated with albumin. The formula used for correction is 3.5 − albumin (g/dl) + measured calcium (mg/dl).

For coagulation studies, blood samples were often pooled due to the large volume needed for a full coagulation panel and the decreased blood volume that was typically obtained from LeTx animals. LeTx C57BL/6J mice (66.4 ± 4.3 h, mean time of advance clinical signs ± SE) showed thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated prothrombin time (PT) and elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) compared to controls (Table 2). Platelets were statistically lower in LeTx mice than in vehicle mice, and the other three coagulation parameters showed no overlap in data points between LeTx and control mice.

TABLE 2.

Coagulation profilesa

| Group | Animal(s) | Platelet count (103/mm3) | Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | APTT (s) | PT (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | B22, B28 | 893 | 152 | 31.2 | 12.4 |

| B24, B26 | 1,032 | 162 | 28.5 | 11.5 | |

| B32, B36, B40 | 143 | 15.9 | 11.2 | ||

| B32 | 524 | ||||

| B36 | 731 | ||||

| B40 | 437 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 723.4 ± 247.9 | 152.3 ± 9.5 | 25.2 ± 8.17 | 11.7 ± 0.62 | |

| LeTx | B23, B17, B27 | 179 | <20 | 98.2 | 32.1 |

| B33, B35, B37 | 60 | 43.9 | 24.5 | ||

| B33 | 256 | ||||

| B35 | 144 | ||||

| B37 | 85 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 166.0 ± 71.45 | 40.0 ± 28.3 | 71.05 ± 38.4 | 28.3 ± 5.37 | |

| Pb | 0.0159 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Animal groups with two or more identifications were pooled due to small sample size and increased amount of blood needed for coagulation profiles.

Formulated using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test.

There was no clear difference between the different strains of mice given LeTx with regard to gross pathology, which included hemothorax (8/29), hemoabdomen (6/29), hemorrhagic gall bladder (3/29), subdural hemorrhage (2/29), hemorrhage in a small section of jejunum (1/29), pale livers (2/29), and ascites (1/29). Subsequent studies in LeTx C57BL/6J mice revealed spleen hematomas, pale kidneys, excessively pale mesenteric fat, a high frequency of subdural hematomas and pale livers, and hemorrhage in the heart, brain, and large segments of the intestine (unpublished observations).

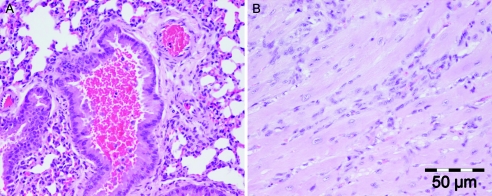

Histopathologically, the two main findings were hemorrhage into secondary and tertiary bronchi (10/29) (Fig. 1A) and evidence of heart muscle damage (9/29) that sometimes included fibroblast infiltration into the interstitium (Fig. 1B). Other findings included hepatic microabscesses and granulomas (4/29), small intestinal mucosal edema (1/29), and hematoma formation in the cardiac ventricular muscle wall (1/29).

FIG. 1.

(A) Pulmonary airway hemorrhage in a lumen of a bronchus in a LeTx-injected mouse (H&E stain). (B) Myocardial interstitial disease with infiltration of fibroblasts into the interstitial space between myocardial fibers. The presence of the fibroblasts indicates a reparative process after an insult to the cardiac muscle following LeTx injection. Tissue was taken from a mouse that survived the toxin challenge and was euthanized 11 days after LeTx injection (H&E stain).

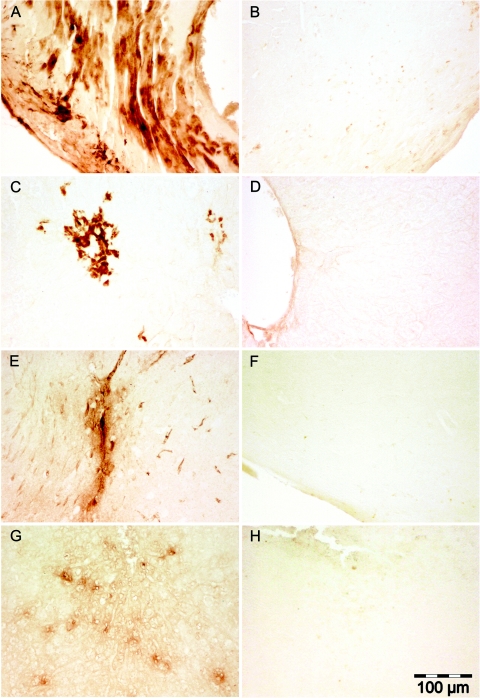

Fibrin deposits were present in the heart (Fig. 2A), liver (Fig. 2C), meninges (Fig. 2E), and spleen (Fig. 2G), but no single organ had deposits in all LeTx animals, nor did all LeTx animals have evidence of fibrin deposits.

FIG.2.

(A) Diffuse fibrin deposits throughout the cardiac musculature in a LeTx-injected mouse. (B) Cardiac muscle from a control mouse. (C) Focal areas of fibrin deposits in the liver parenchyma of a LeTx injected mouse. (D) Liver parenchyma of a control mouse. (E) Fibrin deposits in the meninges and underlying brain tissue from a LeTx mouse. (F) Meninges and underlying brain tissue of a control mouse. (G) Multifocal areas of fibrin deposits in the parenchyma of the spleen of a LeTx mouse. (H) Spleen parenchyma of a control mouse.

Glutathione levels were reduced in the lungs of LeTx C57BL/6J mice compared to vehicle mice (1.64 versus 2.11 nmol/mg tissue, median values, respectively; two-tailed generalized Wilcoxon test, n = 4/group, P = 0.0286). In the liver, glutathione was reduced in LeTx C57BL/6J mice compared to vehicle mice, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance (4.24 versus 5.98 nmol/mg tissue, n = 4/group, P = 0.1143).

The blood chemistry of LeTx C57BL/6J animals provides an insight into pathogenesis. Hypoglycemia in LeTx mice was generally not low enough to cause clinical symptoms; thus, the low level is likely a secondary finding due to increased vessel permeability enabling loss of glucose into the extravascular space. LeTx C57BL/6J mice also showed hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypoglobulinemia compared to control animals, and vessel leakage is the likely cause of these reductions. LeTx was found to induce human endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro, suggesting a direct effect on the endothelial cells (8). However, tissue sections from LeTx mice that were stained for the apoptotic marker cleaved caspase-3 failed to reveal labeled endothelial cells (unpublished observation), but this does not rule out endothelial cell dysfunction, which could account for increased vessel leakage. In support of this possibility, LeTx has been found to alter endothelial barrier function in vitro independently of apoptosis or necrosis (14).

The elevated BUN in LeTx C57BL/6J mice in the presence of normal creatinine levels indicates a prerenal disorder, such as hemorrhage into the peritoneal or thoracic cavities, which was observed in several mice in this study. Intestinal hemorrhage was present in only one animal; however, we have observed hemorrhage in the intestine and in other organs (e.g., spleen and brain) in numerous subsequent LeTx C57BL/6J mice.

LeTx C57BL/6J animals showed a significantly decreased platelet count, decreased fibrinogen, and elevations in PT and APTT compared to controls. The decrease in platelets and fibrinogen is explained by their increased usage, which occurs in a consumption coagulopathy such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and/or increased loss due to increased vessel permeability or hemorrhage. Fibrin deposits were observed, albeit inconsistently, in a variety of organs from C57BL/6J, F1, and F2 mice, indicating that DIC was part of the pathophysiology in at least some LeTx mice. The elevations in both PT and APTT suggest a coagulopathy affecting all three (intrinsic, extrinsic, and common) clotting cascade pathways. The most likely cause for these changes would be vessel leakage, hemorrhage, and/or DIC.

There is a high concentration of toxin receptors in the bronchi (3), and lung involvement during LeTx pathogenesis is indicated by dyspnea, bronchial hemorrhage, and glutathione depletion. The latter finding reflects oxidative stress in the lung, although some edema also may be occurring, since glutathione is measured as nmol/mg (wet weight) tissue. In either case, LeTx leads either directly or indirectly to cellular dysfunction in the lung.

LeTx CAST/EiJ mice survived to only ∼25 h, which was similar to findings in a previous report (11), while C57BL/6J, F1, and F2 C57BL/6 LeTx mice generally survived longer than CAST/Ei or F2 CAST/Ei LeTx mice. There was an absence of clear blood chemistry findings indicating vessel leakage in LeTx CAST/Ei mice, but their blood was extremely difficult to collect in ample quantities and these mice did show evidence of hemorrhage. Furthermore, histopathology was similar to that for C57BL/6J animals, and 2/5 CAST/EiJ had evidence of fibrin staining. Thus, these mice may progress along a pathophysiological pathway similar to that seen with LeTx C57BL/6J mice, but a rapid onset of respiratory distress or circulatory shock may account for early death.

In summary, LeTx C57BL/6J mice suffered from vessel leakage, hemorrhage, and/or DIC based on chemistry profile, coagulation panels, fibrin deposits, and pathology. Since vessel leakage, hemorrhage, and/or DIC has been observed in anthrax cases (1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13), it suggests that LeTx in mice represents significant components of anthrax pathophysiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marsha Danley for performing the immunohistochemical staining.

This work was supported by internal funds from the University of Kansas Medical Center Lab Animal Resources Department and by external funds from the National Institutes of Health grant U54 AI057160 to the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (MRCE).

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramova, F. A., L. M. Grinberg, O. V. Yampolskaya, and D. H. Walker. 1993. Pathology of inhalational anthrax in 42 cases from the Sverdlovsk outbreak of 1979. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:2291-2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barakat, L. A., H. L. Quentzel, J. A. Jernigan, D. L. Kirschke, K. Griffith, S. M. Spear, K. Kelley, D. Barden, D. Mayo, D. S. Stephens, T. Popovic, C. Marston, S. R. Zaki, J. Guarner, W. J. Shieh, H. W. Carver 2nd, R. F. Meyer, D. L. Swerdlow, E. E. Mast, J. L. Hadler, and the Anthrax Bioterrorism Investigation Team. 2002. Fatal inhalational anthrax in a 94-year-old Connecticut woman. JAMA 287:863-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonuccelli, G., F. Sotgia, P. G. Frank, T. M. Williams, C. J. de Almeida, H. B. Tanowitz, P. E. Sherer, K. A. Hotchkiss, B. I. Terman, B. Rollman, A. Alileche, J. Brojatsch, and M. P. Lisanti. 2005. Anthrax toxin receptor (ATR/TEM8) is highly expressed in epithelial cells lining the toxin's three sites of entry (lungs, skin, and intestine). Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288:C1402-C1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarty, A., M. R. Emerson, and S. M. LeVine. 2003. Heme oxygenase-1 in SJL mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Mult. Scler. 9:372-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui, X., M. Moayeri, Y. Li, X. Li, M. Haley, Y. Fitz, R. Correa-Araujo, S. M. Banks, S. H. Leppla, and P. Q. Eichacker. 2004. Lethality during continuous anthrax lethal toxin infusion is associated with circulatory shock but not inflammatory cytokine of nitric oxide release in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286:R699-R709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman, A., O. Afonja, M. W. Chang, F. Mostashari, M. Blaser, G. Perez-Perez, H. Lazarus, R. Schacht, J. Guttenberg, M. Traister, and W. Borkowsky. 2002. Cutaneous anthrax associated with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and coagulopathy in a 7-month-old infant. JAMA 287:869-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grinberg, L. M., F. A. Abramova, O. V. Yampolskaya, D. H. Walker, and J. H. Smith. 2001. Quantitative pathology of inhalational anthrax I: quantitative microscopic findings. Mod. Pathol. 14:482-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirby, J. E. 2004. Anthrax lethal toxin induces human endothelial cell apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 72:430-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansour-Ghanaei, F., S. Zareh, and A. Salimi. 2002. GI anthrax: report of one case confirmed with autopsy. Med. Sci. Monit. 8:CS73-CS76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mina, B., J. P. Dym, F. Kuepper, R. Tso, C. Arrastia, I. Kaplounova, H. Faraj, A. Kwapniewski, C. M. Krol, M. Grosser, J. Glick, S. Fochios, A. Remolina, L. Vasovic, J. Moses, T. Robin, M. DeVita, and M. L. Tapper. 2002. Fatal inhalation anthrax with unknown source of exposure in a 61-year-old woman in New York City. JAMA 287:858-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moayeri, M., N. W. Martinez, J. Wiggins, H. A. Young, and S. H. Leppla. 2004. The susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin is influenced by genetic factors in addition to those controlling macrophage sensitivity. Infect. Immun. 72:4439-4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price, B. M., A. L. Liner, S. Park, S. H. Leppla, A. Mateczun, and D. R. Galloway. 2001. Protection against anthrax lethal toxin challenge by genetic immunization with a plasmid encoding the lethal factor protein. Infect. Immun. 69:4509-4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasconcelos, D., R. Barnewall, M. Babin, R. Hunt, J. Estep, C. Nielsen, R. Carnes, and J. Carney. 2003. Pathology of inhalation anthrax in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Lab. Investig. 83:1201-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warfel, J. M., A. D. Steele, and F. D'Agnillo. 2005. Anthrax lethal toxin induces endothelial barrier dysfunction. Am. J. Pathol. 166:1871-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]