Abstract

Aging is a dynamic process characterized by complex molecular changes, including shifts in lipid metabolism. To systematically define lipidome dynamics with age and identify sex-specific lipidomic signatures, we performed targeted lipidomic profiling of plasma samples from 1030 adults aged 50–98 years, analyzing 543 lipid species across all lipid classes using high-throughput mass spectrometry and assessing the circulating fatty acid composition by gas chromatography.

Our results reveal age-related lipidomic shifts, with ceramides and ether-linked phospholipids most affected. We identified three aging crests (55–60, 65–70, 75–80 years), with the 65–70 years crest dominant in men and the 75–80 years crest in women. Lipid enrichment analyses highlight acylcarnitines, sphingolipids and ether-linked phospholipids as key contributors, with functional indices indicating compositional shifts in lipid species.

These findings suggest an impairment of lipid functional categories, including loss of dynamic properties, alterations in bioenergetics, antioxidant defense, cellular identity, and signaling platforms. This study underscores the non-linear nature of lipid metabolism in aging and provides a foundation for identifying biomarkers and interventions to promote healthy aging.

Keywords: Aging dynamics, Aging crests, Metabolic adaptation, Lipid metabolism, Sex-specific lipidomics, Ether-linked phospholipids, Sphingolipids

1. Introduction

Aging is a dynamic process characterized by molecular changes that impact biological systems at multiple levels, including the genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and lipidome. These changes lead to a progressive decline in metabolic, cellular and tissue function [1] and contribute to the prevalence of age-related diseases [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. Understanding the complex patterns underlying the aging process is essential for identifying molecular signatures and uncovering mechanistic insights [7]. In this context, identifying inflection points and waves of change in biological data is crucial for improving our understanding of the physiological processes underlying aging. Such insights can inform strategies for early diagnosis and prevention of age-related diseases, which significantly increase morbidity and mortality rates while adversely affecting healthspan and quality of life [7,8].

Omics technologies are essential to comprehensibly understand the aging process and age-related diseases [9,10]. Lipidomics, which involves the extensive analysis of lipid profiles within biological systems, focuses on the dynamic nature of the lipidome and its crucial roles in cellular structural integrity, metabolism, signaling, bioenergetics, antioxidant capacity and inflammation, all of which modulate aging[[11], [12], [13], [14]]. Consequently, changes in lipidome composition influence critical aging processes such as metabolic regulation, cellular senescence, and chronic inflammation [12].

Plasma samples are a valuable resource in aging research due to their accessibility and ability to reflect systemic metabolic states and cellular functions [15,16]. Significantly, plasma transfer studies revealed that young plasma can partially reverse age-related brain changes in older animals, emphasizing the importance of plasma components in aging [17,18]. The circulating lipidome provides insights into metabolic states, correlates with longevity, and serves as a powerful tool for identifying biomarkers of aging and age-related diseases[15,[19], [20], [21], [22]]. Importantly, the circulating and membrane lipidome is a structured, complex, dynamic and flexible system, which demands functional plasticity, internal controls to monitor changes and confer stability, and adaptive responses to preserve essential biological properties and cellular functions within physiological limits [23,24]. The result is the formation and maintenance of a specific circulating and membrane lipidome which is tightly regulated by homeostatic mechanisms, with dietary influences being limited and transient, impacting only select lipid species. [[23], [24], [25]]. Consequently, lipidomics offers a robust framework for investigating age-related shifts in the lipidome, enabling the development of strategies to extend healthy lifespan and enhance quality of life through precision medicine [15].

Despite its promise, lipidomic research on aging during adult life in humans remains limited. Only recently researchers have been able to detect and quantify a large part of the human lipidome and capture the full spectrum of lipid classes; therefore large-cohort studies using these techniques are still limited [7,26]. Such large-scale research is particularly essential for providing opportunities to identify novel biomarkers and uncover pathways involved in aging incorporating sex-based differences, as aging dynamics vary significantly by sex—a major determinant of the plasma lipidome [15,27].

This study aims to characterize age-related shifts in the circulating lipidome, with a focus on sex-specific effects on lipid metabolism during human aging. Utilizing high-throughput targeted mass spectrometry (MS)-based lipidomic profiling, we analyzed 543 lipid species from plasma samples of a healthy adult cohort consisting of 1030 individuals aged 50–98 years (45.5 % females and 54.5 % males). Our objective is to systematically define lipidome dynamics with age and biomarkers of aging while providing a more comprehensive understanding of molecular-level sex-specific lipidomic changes associated with the aging process.

2. Results

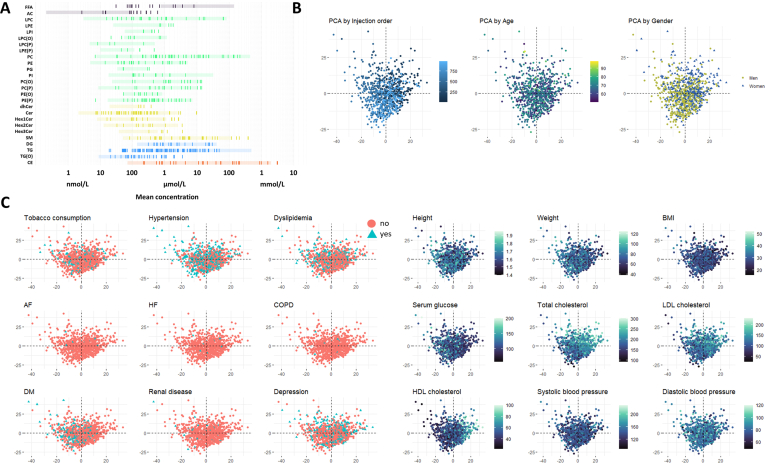

2.1. Plasma lipidomic profiling and health characteristics of the study population

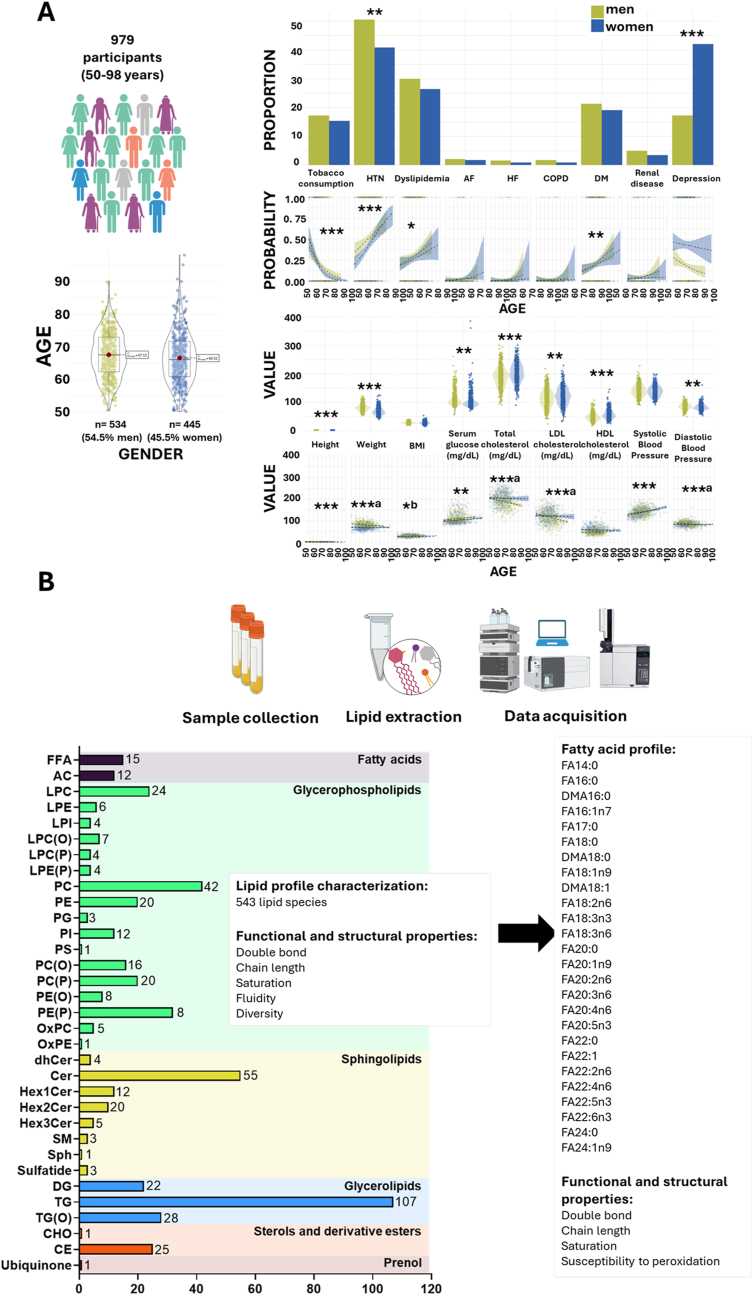

A targeted lipidomic approach encompassing 543 lipid species from all lipid classes was conducted to characterize the circulating lipidomic profile of a cohort of 1030 individuals aged 50–98 years. The study population (plasma samples were available from 979 participants) included 534 men (54.5 %) and 445 women (45.5 %) (Fig. 1). Women exhibited lower height and body weight compared to men, with no significant differences in body mass index (BMI). From a health perspective, women had a higher prevalence of depression, but a lower incidence of hypertension compared to men. Women also had lower diastolic blood pressure and serum glucose levels but higher levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol (Fig. 1A). Prevalence of tobacco consumption and height decreased with age, whereas dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, serum glucose and systolic blood pressure increased. BMI increased only in women and LDL and total cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure and weight decreased in men.

Fig. 1.

Study population characteristics and plasma lipidomics workflow.

A. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. The figure presents the demographic composition, clinical pathologies, and biochemical parameters of the study population (n = 979), consisting of individuals aged between 50 and 98 years. The cohort includes 54.5 % males and 45.5 % females. Pathological conditions and biochemical markers are shown, stratified by sex, to illustrate differences and distributions across the population. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001, a significant only in men, b significant only in women. AF: atrial fibrillation, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, DM: diabetes mellitus, HTN: hypertension, HF: heart failure. B. Overview of the lipidomics workflow for plasma analysis. The figure outlines the lipidomics workflow, starting with plasma sample collection, followed by lipid extraction, and data acquisition using liquid chromatography coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-QQQ-MS). A total of 543 lipid species, spanning all major lipid families, and 26 fatty acids were detected. From these lipids, functional and structural properties of the plasma lipidome were calculated, including double bond content, saturation level, chain length, susceptibility to peroxidation, lipid fluidity, and lipid diversity.

The mean and median concentration of each lipid, expressed in nmol/mL, are provided in Supplementary Dataset 1. The values obtained are consistent with those previously reported in the literature, supporting the reliability of our lipid quantification[[28], [29], [30], [31]]. To provide a reference framework, lipid concentrations were compared to values reported for the NIST Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1950, which represents ‘normal’ human plasma obtained from 100 healthy donors (equal numbers of men and women aged 40–50 years), with a racial distribution reflecting that of the U.S. population (Supplementary Fig. 1A). While the NIST SRM provides a standardized reference for lipid concentrations in healthy adult plasma, physiological processes such as aging may lead to deviations from these values. Notably, the higher levels of acylcarnitines observed in our cohort compared to the NIST SRM are consistent with previous findings reported in an elderly Spanish population [32], reinforcing that these differences reflect age-associated metabolic shifts rather than technical variability. To assess potential batch effects, a principal component analysis (PCA) including all samples and their injection order was performed, and suggest minimal impact of injection sequence on data variability (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, to ensure maximum robustness, injection order was included as a covariate in all statistical models. To explore the influence of age, sex, and other potential confounders on lipidome variability, we performed a PCA, with samples colored by these variables. Among them, cholesterol levels (total, LDL, and HDL) showed a notable contribution to the observed variance (Supplementary Fig. 1B and C). To further explore the circulating lipidome, functional and structural properties were assessed using calculated indexes, such as saturation (SAT), average chain length (ACL), double bond index (DBI), fluidity index (FlI), and diversity index (DvI) (see Methods section), derived from the 543 lipid species detected and quantified (Fig. 1B). The specific contribution to the indexes is specified in Supplementary Dataset 2. Additionally, the basal fatty acid composition of the circulating lipidome, expressed as %mol, along with derived indexes, was determined (Fig. 1B) and is detailed in Supplementary Dataset 1. To investigate the changes in the lipid phenotype associated with aging, different analytical approaches were employed, including both linear and non-linear modelling to also account for non-linear trends across human aging adjusting by all the relevant clinical parameters (Supplementary Fig. 2, Methods), and performing enrichment analyses by lipid category to define which ones were significantly affected during human aging. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we accounted for hypolipemiant drug use as a confounding factor. The results showed minimal lipid changes (<5 %) with borderline significance, confirming that medication use does not impact our conclusions. This is likely due to the high overlap between dyslipidemia and hypolipemiant drug users (73 %), while only 5 % of individuals with dyslipidemia were not on medication, minimizing its independent effect on lipidomic changes. Given these results and the variability in drug type, treatment, and dosage within hypolipemiant drugs, the analysis was maintained without considering this factor as a confounder.

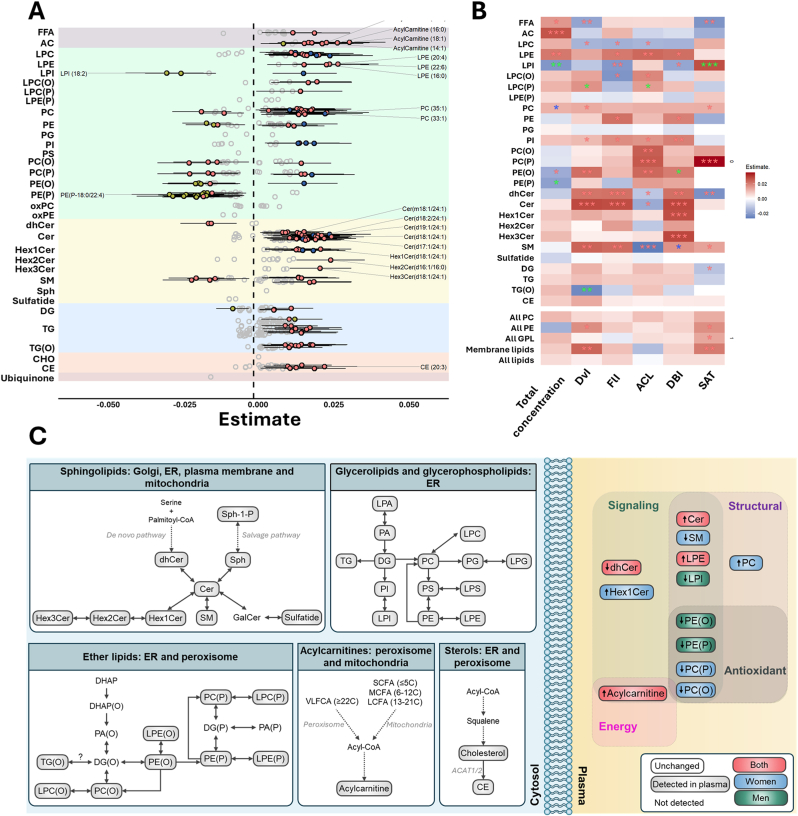

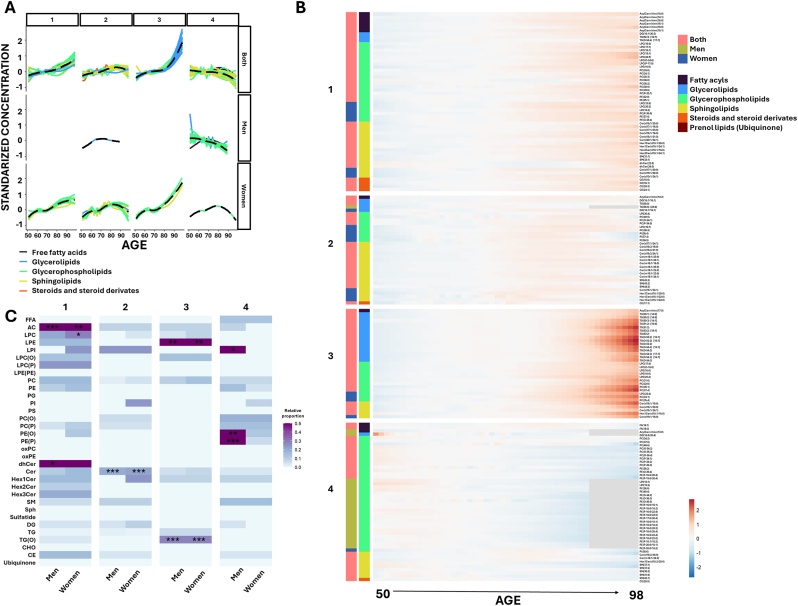

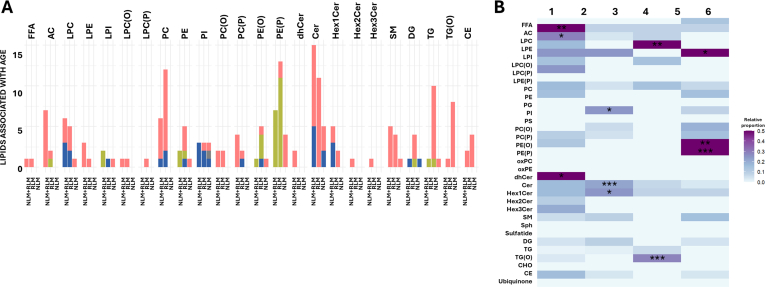

2.2. Aging drives comprehensive alterations in the sphingolipid profile

Linear regression analysis highlighted significant shifts in sphingolipid metabolism over the aging process. Specifically, aging was associated with decreased levels of dehydroceramides and increased ceramides in both sexes, and increased hexosyl1ceramides (Hex1Cer) and decreased sphingomyelin exclusively in women (Fig. 2, Supplementary Dataset 3). Moreover, analyses of functional and structural properties of plasma sphingolipidome exhibited consistent age-related trends. In dehydroceramides, DvI, FlI, and DBI increased with age, while ACL and SAT decreased. Similarly, ceramides showed age-associated increases in DvI, FlI, and DBI, along with a reduction in ACL. For hexosylated ceramides, DBI increased in both Hex1Cer and Hex3Cer species. In sphingomyelins, aging was associated with increased DvI, FlI, and DBI (particularly in women), an increase in SAT, and a decrease in ACL. Non-linear modeling further uncovered 4 lipid clusters based on their aging-associated patterns (Fig. 3A and B, Supplementary Dataset 4 and 5). Cluster 2, enriched with ceramides species, complemented the linear analyses by revealing that the global increase in ceramides levels during aging plateau and begin to decline around the age of 85 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Plasma lipid species linearly associated with age, grouped by class.

A. The forest plot illustrates the significant associations (FDR p-value <0.05) between the relative abundance of each lipid metabolite (z-scored) and age, using robust linear regression models. Models were adjusted for weight, height, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, history of depression, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac insufficiency, renal disease, atrial fibrillation, COPD, tobacco consumption, as well as serum glucose, total cholesterol, and HDL and LDL cholesterol. Dots represent the robust linear regression estimates for age, with whiskers indicating bootstrapped 95 % confidence intervals. Positive associations are shown in red for both sexes, blue for females, and green for males. Lipid classes are color-coded as follows: fatty acyls (gray), glycerophospholipids (green), sphingolipids (yellow), glycerolipids (blue), steroids and derivatives (orange), and ubiquinone (maroon). Top 20 lipids with lowest p-value are displayed. B. Heatmap representation of the robust linear regression estimates of the functional and structural properties of the lipidome, including significant lipid classes that show association with age for both sexes or separately for males and females. Properties include metrics such as total content, double bond content, chain length, saturation, lipid diversity, and lipid fluidity. A red asterisk indicates significance for both sexes, blue for females only, and green for males only (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). C. Schematic representation of the main affected lipid pathways. On the left (cytosol), lipid metabolic pathways are depicted, highlighting cellular compartments where the metabolic processing of detected lipids occurs. Pathways include additional lipid species that are part of these pathways but were not detected in the present study. On the right (plasma), only lipids identified as significant in the enrichment analyses are displayed, stratified for both sexes, as well as separately for males and females. Positive associations are shown in red for both sexes, blue for females, and green for males. FFA: free fatty acids; SCFA: short chain fatty acids; MCFA: medium chain fatty acids; LCFA: long chain fatty acids VLCFA: very-long chain fatty acids; LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE: lysophosphatidylethanolamine; LPI: lysophosphatidylinositol; LPC(O): alkyl-lysophosphatidylcholine; LPC(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- lysophosphatidylethanolamine; PC: phosphatidylcholine; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: phosphatidylglycerol; PI: phosphatidylinositol; PS: phosphatidylserine; PC(O): alkyl-phosphatidylcholine; PC(P) alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylcholine; PE(O): alkyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; PE(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylethanolamine; oxPC: oxidized phosphatidiylcholine; oxPE: oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine; dhCer: dihydroceramide; Cer: ceramide; Hex1Cer: hexosyl1ceramide; Hex2Cer: hexosyl2ceramide; Hex3Cer: hexosyl3ceramide; SM: sphingomyelin; Sph: sphingosine; DG: diacylglycerol; TG: triglyceride; TG(O): ether-linked triglyceride; CHO: cholesterol; CE: cholesteryl ester; LPA: Lysophosphatidic Acid; PA: Phosphatidic Acid; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; LPG: lysophosphatidylglycerol; LPS: lysophosphatidylserine; Sph-1-P: sphingosine-1-phosphate; GalCer: galactosylceramide; AC: acylcarnitine; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DG(O): ether-linked diacylglycerol. All PC: sum of the concentration of all phosphatidylcholines; All PE: sum of the concentration of all phosphatidylethanolamine; All GPL: sum of the concentration of all glycerophospholipids; Membrane lipids: sum of the concentration of all glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids; ACL: average chain length; DBI: double bond index; FlI: fluidity index. DvI: diversity index. FlI is calculated according to chain length and double bonds of their fatty acids. DvI represents the probability that two lipids randomly selected from a sample will belong to different species. Higher diversity values indicate higher diversity of lipids within the specified lipid class.

Fig. 3.

Clustering analysis and age-associated lipid patterns.

A. Clustering analysis of lipids associated with age across the study population, separated into six distinct clusters. The analysis considers lipid associations common in both sexes, and those specific for males and females. Solid lines represent the optimized LOESS smoothed function for each lipid and are colored according to lipid class. Dashed lines represent the overall cluster trend. B. Heatmap representation of lipid abundance by age, displaying the lipids within each cluster. Lipids are ordered according to their lipid class. The associations are indicated by color-coded bars: red for both sexes, green for males, and blue for females. C. Heatmap representing the proportion of lipids from each lipid category within each cluster, showing significant results from the enrichment analysis (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Results are stratified by sex, highlighting enriched lipid classes separately for males and females. Lipid classes are color-coded as follows: fatty acyls (gray), glycerophospholipids (green), sphingolipids (yellow), glycerolipids (blue), steroids and derivatives (orange), and ubiquinone (maroon). FFA: free fatty acids; AC: acylcarnitine; LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE: lysophosphatidylethanolamine; LPI: lysophosphatidylinositol; LPC(O): alkyl-lysophosphatidylcholine; LPC(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- lysophosphatidylcholine; PC: phosphatidylcholine; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: phosphatidylglycerol; PI: phosphatidylinositol; PS: phosphatidylserine; PC(O): alkyl-phosphatidylcholine; PC(P) alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylcholine; PE(O): alkyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; PE(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylethanolamine; oxPC: oxidized phosphatidylcholine; oxPE: oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine; dhCer: dihydroceramide; Cer: ceramide; Hex1Cer: hexosyl1ceramide; Hex2Cer: hexosyl2ceramide; Hex3Cer: hexosyl3ceramide; SM: sphingomyelin; Sph: sphingosine; DG: diacylglycerol; TG: triglyceride; TG(O): ether-linked triglyceride; CHO: cholesterol; CE: cholesteryl ester.

2.3. Shifts in phospholipid metabolism during aging highlight the role of ether-linked lipids

Linear analyses demonstrated a global increase in lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) levels and phosphatidylcholine (PC) mostly in women with aging (Fig. 2, Supplementary Dataset 3). LPE predominantly found in cluster 3, where a pronounced increase is observed at advanced ages (Fig. 3, Supplementary Dataset 5). Additionally, a reduction in lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) levels was identified in men, as confirmed by both linear and non-linear models (cluster 4), alongside a non-linear increase in lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) in women (cluster 1), and a rise in phosphatidylinositol (PI) levels up to 85 years of age, followed by a decline in older individuals (cluster 2) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Supplementary Dataset 3, 4 and 5). In terms of functional and structural properties, SAT of all glycerophospholipids increased with age. Particularly, DvI and SAT of PC increased, along with FlI and DBI of PE, and FlI, ACL, and DBI of LPE. FlI, ACL and DvI of LPC decreased, and FlI and DBI of LPI decreased while SAT increased in men.

Notably, ether-linked phospholipids exhibited significant alterations during aging. Ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), including both alkyl- (PE(O)) and alkenyl- (PE(P)) bonds, decreased significantly in men, while PC(O) and PC(P) decreased in women (Fig. 1, Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 2). PE(O) and PE(P) play a key role in defining cluster 4 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Dataset 5). Interestingly, functional and structural analyses revealed that DvI, ACL, and DBI (only in men) of PE(O) increased with age, while no significant functional or structural differences were observed in PE(P). Similarly, ACL and SAT of PC(P) and the ACL of PC(O) also showed an age-related increase, highlighting specific compositional shifts in ether-linked phospholipids during aging. DvI and ACL of LPC(P) increased with age in men, while FlI of LPC(O) decreased and ACL increased (Fig. 2B).

2.4. Energy metabolism alterations associated with aging

Aging induced notable changes in lipid species closely linked to energy metabolism. Linear analyses demonstrated a global increase in acylcarnitines and an increase in specific species of triglycerides (TG) (including ether-linked species), and cholesterol esters (CE). Interestingly, most of the TG(O) that significantly increased with age contained a C18:1 (oleic acid) in their structure, and most of the TG had a low degree of unsaturation in their fatty acyls (Supplementary Dataset 3). Globally, DvI of ether-linked TG decreased in men. Although the total levels of diglycerides and fatty acyls did not exhibit significant changes with aging, SAT of diglycerides decreased, while both DvI and SAT of fatty acyls decreased (Fig. 2B). Non-linear models provided further insights, revealing that acylcarnitines were predominantly associated with cluster 1, which included species that increased during aging. Cluster 3 is enriched in TG(O) including species that increased during aging and exhibited a sharp increase in the later stages of life (Fig. 3).

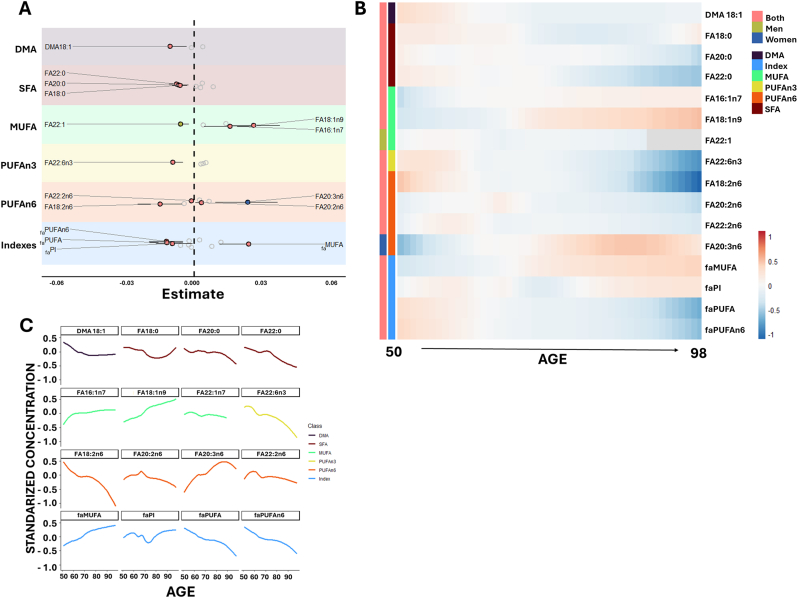

2.5. Age-associated changes in basal fatty acid profile of the circulating lipidome

As fatty acids form the core of most lipid complexes and play a key role in determining physico-chemical and biological properties of circulating and membrane lipids, we analyzed the basal fatty acid profile of the circulating lipidome. Specifically, we examined 26 individual fatty acids and 10 functional and structural fatty acid-related indexes, including saturated fatty acids (faSFA), unsaturated fatty acids (faUFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (faMUFA), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (faPUFA) from the n-3 and n-6 series (faPUFAn-3 and faPUFAn-6). Additionally, we assessed dimethyl acetal (faDMA) ─as fatty acid forms present in ether-linked lipids─, the average chain length (faACL), the double-bond index (faDBI), and the peroxidizability index (faPI) (Fig. 1, Fig. 4, Supplementary DataSet 1).

Fig. 4.

Age-Associated Changes in Circulating Fatty Acid Profile

A. Forest plot illustrating the significant associations (FDR p-value <0.05) between the relative abundance of each fatty acid and related indexes (z-scored) and age, using robust linear regression models. Models were adjusted for weight, height, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, history of depression, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac insufficiency, renal disease, atrial fibrillation, COPD, tobacco consumption, as well as serum glucose, total cholesterol, and HDL and LDL cholesterol. Dots represent the regression estimates for age, with whiskers indicating bootstrapped 95 % confidence intervals. Positive associations are color-coded: red for both sexes, blue for females, and green for males. Only statistically significant fatty acids and indexes are displayed. B. Heatmap representing fatty acid abundance and related indexes across age, displaying lipids within each cluster. Associations are indicated by color-coded bars: red for both sexes, green for males, and blue for females. C. Non-linear trends for statistically significant fatty acids associated with age. Solid lines represent the optimized LOESS-smoothed function for each fatty acid. Color coding indicates fatty acid groups: dimethyl acetals (DMA) in purple, saturated fatty acids (SFA) in red, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) in green, polyunsaturated fatty acids n-3 (PUFAn-3) in yellow, PUFAn-6 in orange, and derived indexes in blue. FA: fatty acid.

Linear and non-linear modeling revealed that aging modulates the fatty acid composition of the circulating lipidome (Fig. 4A and C, Supplementary DataSet 3, 4 and 5). Specifically, DMA18:1 levels decreased with age. Among saturated fatty acids, FA18:0, FA20:0, and FA22:0 decreased at advanced ages. Regarding monounsaturated fatty acids, FA18:1 and FA16:1 increased with age in both sexes, whereas FA22:1 decreased only in men. For polyunsaturated fatty acids, FA22:6n3, FA18:2n6, and FA22:2n6 exhibited an age-related decline, while FA20:2n6 and FA20:3n6 increased only in women.

Globally, faMUFA levels increased with aging, whereas faPUFA – particularly faPUFAn-6 – and faPI decreased. The specific patterns of changes in all significantly affected fatty acids and derived indexes are presented in Fig. 4B–C.

Notably, FA 16:1 or 18:1 were present in about 50 % of Ceramides (12/25) and TG(O) (4/6), and in all HexCer (8/8, 6 Hex1Cer, 1 Hex2Cer and 1 Hex3 Cer), and DG (3/3), belonging to clusters 1–3, which contains those lipids that increased with age (Supplementary Dataset 5).

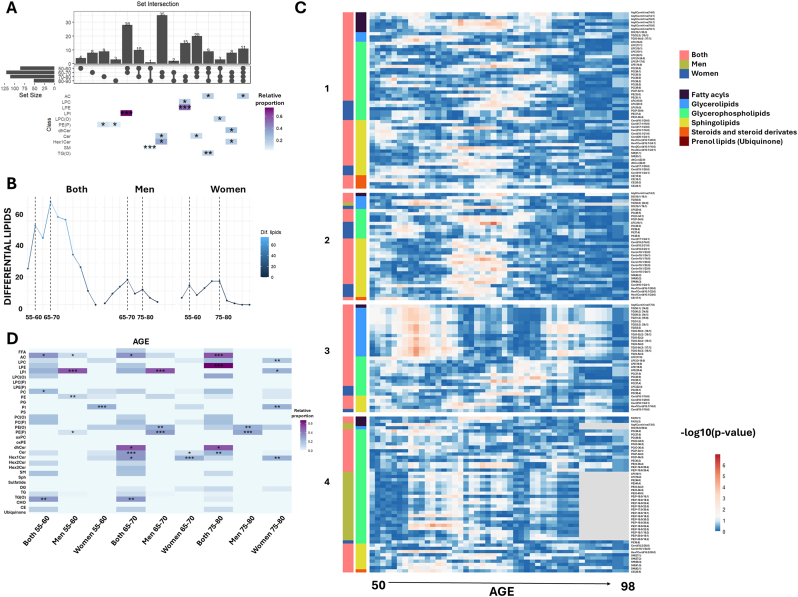

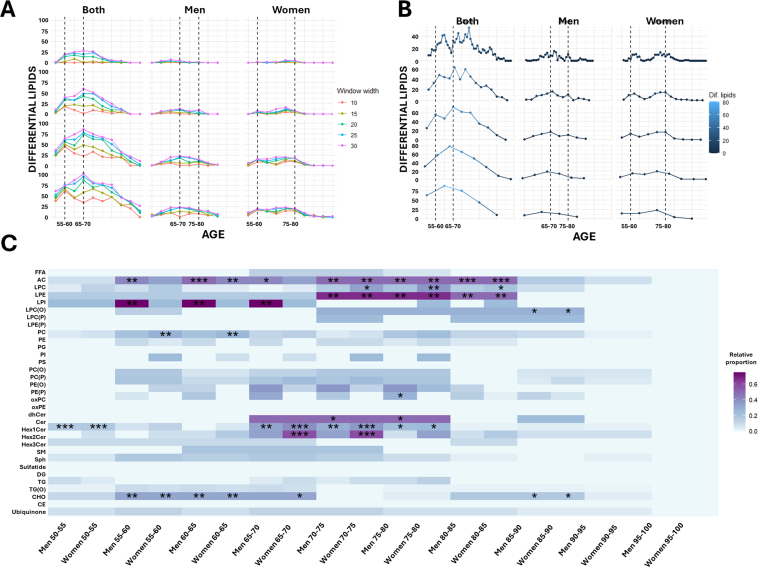

2.6. Three global aging crests highlight ether-linked phospholipids as sex-specific markers

To identify the most significant lipidomic alterations associated with aging, year-by-year changes were analyzed. First, a decade-by-decade comparison was conducted to determine lipid species that exhibited changes at some point within each decade, those specific to a particular decade, and those shared across multiple decades (Fig. 5, Supplementary Dataset 6). Results revealed 11 lipid species that changed consistently across all decades, predominantly acylcarnitines, highlighting the critical role of these lipids in the aging process. Additionally, 40 lipid species were identified as common to at least three decades. Specifically, ceramides changed in the first three decades (50–80), while dehydroceramides and Hex1Cer were prominent in the last three decades (60–90). TG(O) species varied in the first two decades (50–70), stabilized during the following decade (70–80), and changed again in the final decade (80–90). LPC(O) exhibited alterations in the first (50–60) and last two decades (70–90), remaining stable between 60 and 70. Interestingly, LPI changes were observed in the first two decades (50–70), while ceramides and Hex1Cer changed between 60 and 80 years. PE(P) metabolism was more affected in the last two decades (70–90).

Fig. 5.

Lipidomic changes across decades and aging crests.

A. UpSet plot illustrating common lipid changes by decade. Each bar represents an intersection, as indicated by the dots below, and the height of the bar, along with the number on top, reports the number of significant lipids within each intersection. Enriched lipid categories in each intersection are shown as a heatmap, with colors indicating the proportion relative to all analyzed lipids in that category. Asterisks represent significant results from enrichment analysis (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). B. Dot plot representing the number of differentially expressed lipids across ages, grouped into five-year intervals. C. Heatmap of the p-value distribution for lipid differences at each age. Colors represent the negative logarithm of p-values derived from Mann-Whitney U tests comparing lipid concentrations before and after each specified age. Lipids are ordered by lipid class, with associations indicated by color-coded bars: red for both sexes, green for males, and blue for females. D. Heatmap depicting the proportion of lipids from each lipid category within each aging crest. Significant results from enrichment analyses are indicated by asterisks (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Results are stratified by sex, highlighting enriched lipid classes separately for males and females. Lipid categories are color-coded as follows: fatty acyls (gray), glycerophospholipids (green), sphingolipids (yellow), glycerolipids (blue), steroids and derivatives (orange), and ubiquinone (maroon). FFA: free fatty acids; AC: acylcarnitine; LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE: lysophosphatidylethanolamine; LPI: lysophosphatidylinositol; LPC(O): alkyl-lysophosphatidylcholine; LPC(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- lysophosphatidylcholine; PC: phosphatidylcholine; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: phosphatidylglycerol; PI: phosphatidylinositol; PS: phosphatidylserine; PC(O): alkyl-phosphatidylcholine; PC(P) alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylcholine; PE(O): alkyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; PE(P): alkenyl (plasmalogen)- phosphatidylethanolamine; oxPC: oxidized phosphatidylcholine; oxPE: oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine; dhCer: dihydroceramide; Cer: ceramide; Hex1Cer: hexosyl1ceramide; Hex2Cer: hexosyl2ceramide; Hex3Cer: hexosyl3ceramide; SM: sphingomyelin; Sph: sphingosine; DG: diacylglycerol; TG: triglyceride; TG(O): ether-linked triglyceride; CHO: cholesterol; CE: cholesteryl ester.

To further pinpoint periods of significant lipidomic alterations, the number of differential lipid species was quantified in five-year intervals, identifying key crests in the aging process (Fig. 5B–D, Supplementary Dataset 7). Three majors global lipidomic crests were identified during the aging process, with intensity and lipid class predominance varying by sex. Overall, the most significant changes involved acylcarnitines, ceramides, glycosphingolipids and LPI, with each crest displaying specific sex-related features, and ether-linked phospholipids playing a prominent role. Specifically, two crests were observed when considering those lipids affected in both men and women: one between 55 and 60 years and another between 65 and 70 years. Sex-specific analyses revealed two crests in men, at 65–70 and 75–80 years, with the most prominent crest occurring at 65–70 years. In women, two crests were observed at 55–60 and 75–80 years, with the 75–80 crest being the most prominent. This highlights a key differential feature in the aging process, with men exhibiting a peak earlier than women. The detected crests persisted under varying age windows, steps, and p-value thresholds (Supplementary Fig. 3), and disappeared when ages were permuted. The distribution of p-values across ages is visualized in Fig. 5C.

Enrichment analysis of lipid classes at each detected crest revealed distinct patterns. The species changed in both sexes at the 55–60 years were enriched with acylcarnitines, PC and TG(O). Furthermore, specific acylcarnitines, LPI, PE and PE(P) changed in men, while PI changed in women. At the 65–70 years crest, acylcarnitine, dihydroceramide, ceramide, Hex1Cer and TG(O) enrichment was observed in both sexes, with LPI, PE(O) and PE(P) specifically enriched in men, and changes in specific ceramides and Hex1Cer were more prominent in women. Finally, at the 75–80 years crest, acylcarnitines and LPE dihydroceramides and ceramides changed similarly in both sexes, while PE(O) and PE(P) were enriched in men, and LPC, LPI, PI and Hex1Cer in women.

3. Discussion

Aging is a complex process marked by linear and nonlinear molecular changes [7] that impact various biological systems, including the lipidome. In this study, we employed high-throughput lipidomic profiling to comprehensively examine age-related shifts in the circulating lipidome, quantifying 543 lipid species across a well-characterized study population of 979 healthy adults (45.5 % females, 54.5 % males) aged from 50 to 98 years, accounting for multiple health characteristics. By integrating sex-specific analyses, we aimed to uncover distinct lipidomic patterns and dynamics, providing deeper insights into the role of lipid metabolism in aging.

The assessment of health characteristics demonstrated significant sex differences in anthropometric measurements and clinical parameters, consistent with previous reports [33]. Notably, sex-specific patterns in lipid and lipoprotein levels emerged with age, with LDL cholesterol increasing in men and decreasing in women during adulthood, while total cholesterol declined more sharply in men in later years [34].

Our findings revealed that aging impacts lipid metabolism differently across lipid categories, with consistent lipidomic changes observed within each category. The most affected lipid categories included ceramide metabolism species, ether-linked phospholipids, acylcarnitines, TG, TG(O) and CE. A key highlight of our study is the identification of three aging crests (55–60, 65–70, and 75–80 years), representing periods of more pronounced lipidomic changes, with sex-specific differences. In men, the most prominent crest occurred at 65–70 years, while in women, the dominant crest was at 75–80 years. These findings align with previous studies identifying aging crests using various omic approaches, reinforcing the universality of plasma changes during aging [7,35].

Unlike prior studies, our work not only characterizes global aging crests but also reveals sex-specific patterns, offering deeper insight into the interaction between lipid metabolism and aging. The combination of a large cohort and extensive lipidomic coverage enabled a more refined definition of these aging-associated shifts. Lipid enrichment analysis revealed sex-specific patterns for each crest highlighting acylcarnitines, ceramides, glycosphingolipids, LPI and ether-linked phospholipids as main contributors to aging dynamics. Sphingolipids play a crucial role in cellular processes including membrane integrity, oxidative stress, and signal transduction[[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Moreover, sphingolipids are key regulators of longevity[[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]] and have been linked to aging and age-related diseases [28,[46], [47], [48], [49], [50]]. In our study, ceramide levels increased with aging, while dihydroceramides decreased. Notably, Hex1Cer increased, and sphingomyelins decreased exclusively in women, suggesting a sex-specific regulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Plasma ceramide, particularly C24:1, have been linked to aging and age-related diseases[26,46,[51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57]]. Consistent with these findings, our results revealed that C24:1 are the most affected ceramide molecules during aging. Our analysis of the basal fatty acid profile showed an age-related increase in FA16:1 and FA18:1, both present in 50 % of the significant ceramides and all HexCer species. Notably, elevated plasma C18:1 ceramides have been associated with frailty [58] and inflammation [59], while higher C16:1 ceramide levels have been linked to impaired lower-extremity function [60], highlighting their potential role in age-related decline.

A decade-by-decade analysis revealed that ceramide levels change most prominently between 50 and 80 years, contributing significantly to the 65–70 and 75–80 years aging crests. Non-linear modeling showed that ceramide levels increase until 85 years of age, then slightly decline, suggesting that individuals who achieve advanced age have lower plasma ceramide levels. This aligns with a previous findings demonstrating that extreme longevity is associated with reduced ceramide levels due to the preferential formation of hexosylceramides [14]. Notably, C16:1 Hex1Cer levels increased with aging exclusively in women, potentially contributing to their higher life expectancy. Functional and structural analyses showed age-related increases in DvI, FlI, and DBI, and decreases ACL for dihydroceramides, ceramides, and sphingomyelins, indicating that aging affects both lipid abundance and composition. These shifts in lipid diversity could be adaptive membrane remodeling or a sign of dysregulation and dysfunction. Further studies are needed to clarify this distinction.

Phospholipids play a critical role in regulating lifespan and healthspan [61]. While overall phospholipid content tends to decline with age, their specific contribution to the aging process remains incompletely understood. Prior investigations showed divergent findings on the behavior of PC levels with age [26,62]. In our work, we identified a global increase in PC levels, DvI and SAT, with a more pronounced rise in women at advanced ages. PC emerged as a key factor defining the 55–60 aging crest. LPC, recognized for its diverse functions and link to proinflammatory processes [26,63] also displayed a significant non-linear increase in women, consistent with prior findings [26,62]. LPE species, critical for cellular membrane structure and cell signaling, exhibited increased levels during aging, as observed in our work and in previous studies [26,64]. Structural analyses showed age-related increases in FlI and DBI for LPE and PE, indicating adaptive membrane dynamics. LPI, a bioactive lipid messenger [65,66], demonstrated sex-specific regulation in our study, with notable changes in PI-LPI metabolism. These findings underscore the complexity of PI-LPI regulation and its potential role in aging. Further research is required to elucidate the implications of PI-LPI metabolism in the aging process.

Ether-linked phospholipids also displayed marked changes, with PE(O) and PE(P) levels decreasing in men, while PC(O) and PC(P) decrease in women. These results are consistent with previously reported age-associated lipidomic alterations [28]. Ether lipids are strongly linked to aging and longevity, playing a structural role in cell membranes by enhancing lipid packing and reducing membrane fluidity, particularly in lipid raft microdomains [13,67]. They are crucial for membrane trafficking and cell signaling, serving as precursors for key molecules [12]. Additionally, their ether bond confers antioxidant properties, highlighting their protective role in cellular function [13,68].

Interestingly, functional indices (DvI, ACL, and DBI) increased despite the reduction in global PE(O) levels, suggesting compositional shifts that may influence membrane dynamics. Previous studies linked higher ether-linked PE levels with a healthier status, and consistently, reduced PE(O) and PE(P) levels were reported only in men [26].

Aging significantly alters energy metabolism-related lipids [69]. We observed a global increase in acylcarnitine levels and the saturation of their fatty acids, as well as elevated levels of specific TG, including ether-linked species, in which DvI increases, and CE.

Acylcarnitines are essential for transporting fatty acids into the mitochondria, where they fuel β-oxidation and energy metabolism [22,70]. Their age-related increase has been linked to incomplete β-oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction [22,70], a hallmark of aging.

Neutral lipids, including TG and CE, are also closely linked to longevity regulation [69], though their relationship with aging outcomes remains complex [[71], [72], [73], [74], [75]]. We observed an increase in specific TG species with a low unsaturation, particularly C18:1 TG(O), indicating a shift in lipid storage composition. Globally, the observed increase in specific species of TG and CE, along with elevated acylcarnitine levels, may be secondary to mitochondrial dysfunction, further highlighting its central role in aging. Together, these findings reveal the intricate interplay between lipid metabolism, mitochondrial health, and the aging process, offering insights into the metabolic shifts that accompany age-related changes.

Globally, fatty acid composition changes were also evident. Certain fatty acids have been linked to aging and longevity [23,76,77] with specific circulating fatty acid profile emerging as potential marker of longevity [21,78]. Our findings revealed an age-specific circulating fatty acid profile, characterized by decreased levels of FA22:6n3, previously associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [79], while FA20:5n3 remained unchanged, and a reduction in FA18:2n6, consistent with previous studies [78]. At a broader level, we observed an increase in MUFA and a decrease in PUFA, while SFA remained unchanged, in line with prior studies [78]. Notably, the rise in MUFA content, particularly FA18:1n9, has been described as a characteristic signature of long-lived individuals [78]. Whether these changes are a direct consequence of aging or reflect traits of individuals reaching advanced age remains unclear. Further research is needed to determine their role in longevity and aging process.

This study presents several strengths but also some limitations that should be addressed in future research: i) The large cohort size ensured sufficient statistical power to detect lipidomic changes across a wide age range. However, while the overall cohort size was substantial, the number of individuals in older ages was smaller, potentially reducing the statistical power for analyses in these age ranges. This highlights the importance of future studies including larger numbers of individuals in advanced age groups to validate our findings. ii) Another strength of the study is the detailed lipidomic profiling, which quantified over 500 lipid species across all lipid classes, providing an extensive view of the plasma lipidome during aging. Despite this broad scope, some areas of the lipidome remain unexplored due to the inherent limitations of current analytical platforms, which are unable to capture the full diversity of lipid molecules. Future advancements in lipidomic technologies could address these gaps and expand the coverage of the lipidome. iii) The study also benefits from robust statistical analyses, with adjustments made for numerous confounding variables, including anthropometric, health and metabolic factors, ensuring reliable and accurate results. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to track within-individual molecular changes over time. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the dynamic lipidomic shifts observed here and to distinguish whether these changes are causes or consequences of aging. iv) To minimize the dietary influence on the lipidome, we standardized the sampling time. However, certain nutrient-derived metabolites may still influence the plasma lipidome. Additionally, our cohort, drawn from a geographically restricted area in Spain, is relatively homogeneous in lifestyle and dietary habits. However, previous studies suggest that diet-induced lipidomic changes are limited and transient, affecting only specific lipid species[[23], [24], [25]], reinforcing the robustness of our findings. v) The inclusion of a region-specific cohort from Spain allowed for consistent sampling and analysis but introduces an ethnic bias that may limit the generalizability of the findings to other human populations. Expanding the study to more diverse cohorts would enhance its applicability and relevance. vi) Finally, the study emphasizes the modulable nature of the plasma lipidome, opening venues for exploring therapeutic interventions to regulate aging and associated metabolic alterations. However, the lack of information on tissue-specific contributions to the plasma lipidome limits the understanding of how systemic lipid changes reflect organ-specific dynamics. Further research integrating tissue-specific data will be crucial for unraveling the full complexity of lipid metabolism in aging.

In conclusion, this study integrates sex-specific analyses to uncover key lipidomic signatures that highlight the dynamic nature of aging and its differential effects in men and women. Ether lipids emerged as pivotal markers of sex-specific lipidomic differences, playing a central role in aging crests and facilitating metabolic adaptation. Additionally, sphingolipids were key contributors to age-related metabolic shifts. Our findings suggest an age-related impairment in lipid functional categories, including reduced dynamic properties and alterations in bioenergetics, antioxidant defense, cellular identity, and signaling platforms. These insights reinforce the importance of a sex-stratified approach in aging research and provide a robust framework for understanding the interplay between lipid metabolism and aging, paving the way for biomarker discovery and targeted interventions.

4. Methods

4.1. Study cohort, blood collection and plasma isolation

Samples and data from participants included in this study were provided by the IDIBGI Horizontal Aging Program and the IDIBGI Biobank from the Aging Imageomics Study. They were processed following standard operating procedures with the proper approval of the Ethics and Scientific Committees (2017.146). The Aging Imageomics Study is an observational study including participants living in the province of Girona (Northeast Catalonia, Spain). Detailed description of the cohort can be found here [80]. The study population consisted of 1030 subjects aged ≥50 years whose data were collected between November 2018 and June 2019. Eligibility criteria included age ≥50 years, dwelling in the community, no history of infection during the last 15 days, and consent to be informed of potential incidental findings. The mean age of the study population is 67.1 ± 7.3 years (range, 50–98 years), 45.9 % females, and 54.1 % males.

Blood samples from 979 participants were obtained by venipunction in the morning (between 08:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m.) after fasting overnight (8–10 h) and collected in one VACUTAINER CPT (Cell Preparation Tube; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing sodium heparin as the anticoagulant. Plasma fractions were collected after blood sample centrifugation, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and transferred before 4 h to a −80 °C freezer for storage at the Biobank central laboratory for future use. Due to technical issues the number of blood samples stored to perform the metabolomic analyses was 978.

4.2. Targeted lipidomic analysis

Lipidome extraction was performed as described previously [81]. In brief, 10uL of plasma was mixed with 100uL of butanol:methanol (1:1) with 10 mM ammonium formate which contained a mixture of internal standards (Supplementary Dataset 2). Samples were vortexed and set in a sonicator bath maintained at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were then centrifuged (14,000×g, 20 °C, 10 min) before transferring them into sample vials with glass inserts for analysis.

Lipid extracts were analyzed by LC-MS on an Agilent 6495 LC/QC mass spectrometer with an Agilent 1290 series HPLC system and a ZORBAX eclipse plus C18 column (2.1 × 100mm 1.8 mm, Agilent) with the thermostat set at 60 °C. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in positive and negative ion mode with dynamic scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

The solvent system consisted of solvent A: 50 % H2O/30 % acetonitrile/20 % isopropanol (v/v/v) containing 10 mM ammonium formate and solvent B: 1 % H2O/9 % acetonitrile/90 % isopropanol (v/v/v) containing 10 mM ammonium formate. The gradient was as follows: starting with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min at 10 % B and increasing to 45 % B over 2.7 min, then to 53 % over 0.1 min, to 65 % over 6.2 min, to 89 % over 0.1 min, to 92 % over 1.9 min and finally to 100 % over 0.1 min. The solvent was then held at 100 % B for 2.3 min (a total of 13,4 min). Equilibration was as follows: solvent was decreased from 100 % B to 10 % B over 0.1 min and held for an additional 0.9 min. The flow rate was then switched to 0.6 ml/min for 1 min before returning to 0.4 ml/min over 0.1 min. Solvent B was held at 10 % B for a further 0.9 min at 0.4 ml/min for a total cycle time of 16,5 min.

For quantification, chromatographic peaks were assigned to each lipid based on specified transitions (precursor > product ion) and retention time (Supplementary Dataset 2). Peaks were integrated using the Mass Hunter Agilent Mass Hunter Quantitative Analysis 10.1 software (Agilent Technologies). Quantification was achieved by using the ratio between each compound peak and the corresponding internal standard (ISTD). Data are expressed in nmol/mL. The whole dataset with the lipid intensities was introduced to the SERRF online platform [82], and triglycerides and cholesterol esters normalized signals were divided by the respective ISTD median signals to calculate the concentrations.

To further characterize the functional and structural properties of plasma lipidome, different indexes were calculated, as previously described [14]:

Double Bond Index (DBI): Sum, for each lipid species in a category (i.e. class/subclass/other classification): (species concentration∗number of double bonds/number of acyl chains)/total concentration of lipids in the category.

Acyl Chain Length (ACL): Sum, for each lipid species in a category (i.e. class/subclass/other classification): (species concentration ∗ number of carbons/number of acyl chains)/total concentration of lipids in the category.

Saturated species ratio (SAT): Concentration of saturated species in the category/total concentration of lipids in the category.

Fluidity Index (FlI) [83]: Sum, for each lipid species in a category (i.e. class/subclass/other classification): (species concentration ∗ fluidity contribution)/total concentration of lipids in the category.

Fluidity contribution = average of chain length contribution and double bond contribution, where

Chain length contribution = 1-(single chain length of the lipid species-minimum single chain length in the category)/range of single chain lengths in the category.

Double bond contribution = (single chain number of double bonds of the lipid species-minimum single chain number of double bonds in the category)/range of single chain number of double bonds in the category.

Diversity Index (DvI) [84]: Simpson's index of diversity = 1-D. The index follows the rationale from the diversity index calculated in ecology, which indicates the probability that two random individuals picked from an ecosystem belong to a different species, where D is the number of possible pairs from the same species that can be drawn from the sample/total number of possible pairs.

n = number of individuals from a species.

N = total number of individuals in the ecosystem.

We applied this concept to the lipid concentrations to calculate the diversity of plasma lipid species within the same lipid class or within the lipidome to know whether it is related to successful aging or not. Higher values indicate higher diversity of lipids and lower values indicate lower diversity of lipids. We used the alpha.div function from the asbio R package. We calculated the index based on concentrations rather than the number of lipids because most physicochemical properties are related to lipid content.

4.3. Basal fatty acid composition of the lipidome

Fatty acyl groups were analyzed as methyl esters derivatives by gas chromatography as previously described [77]. Lipids were extracted using a chloroform:methanol (2:1) method and transesterified with methanolic HCl at 75 °C for 90 min. Methyl esters were extracted with NaCl and n-pentane, evaporated under nitrogen and dissolved in CS2 for analysis.

Separation was performed using a DBWAX capillary column on an Agilent GC System 7890A with an FID detector in splitless mode. The injection port was maintained at 250 °C, and the detector at 250 °C. The program consisted of 1 min at 150 °C, followed by 25 °C/min to 180 °C, 10 °C/min to 200 °C, 5 °C/min to 220 °C, and finally 10 °C/mint to 230 °C for 5 min, with a post-run at 250 °C for 10 min. The total run time was 16.2 min.

The following fatty acyl indices were also calculated: saturated fatty acids (faSFA); unsaturated fatty acids (faUFA); monounsaturated fatty acids (faMUFA); polyunsaturated fatty acids (faPUFA) from n-3 and n-6 series (faPUFAn-3 and faPUFAn-6, respectively); dimethyl acetal (faDMA); and average chain length, faACL = [(Σ%Total14 x 14) + (Σ% Total16 × 16) + (Σ%Total18 × 18) + (Σ%Total20 × 20) + (Σ% Total22 × 22) + (Σ% Total24 × 24)]/100. The density of double-bonds was calculated with the Double-Bond Index, faDBI = [(1 × Σmol% monoenoic) + (2 × Σmol% dienoic) + (3 × Σmol% trienoic) + (4 × Σmol% tetraenoic) + (5 × Σmol% pentaenoic) + (6 × Σmol% hexaenoic)]. Susceptibility to peroxidation was calculated with the Peroxidizability Index, faPI = [(0.025 × Σmol% monoenoic) + (1 × Σmol% dienoic) + (2 × Σmol% trienoic) + (4 × Σmol% tetraenoic) + (6 × Σmol% pentaenoic) + (8 × Σmol% hexaenoic)]. Fatty acids are expressed in %mol.

4.4. Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, R software version 4.4.2 was used [85]. Lipid levels were normalized by calculating their z-scores. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to assess the effect of the different variables on the lipidome variability using the FactoMineR package [86]. Associations of lipid levels with age and their interaction with sex were evaluated with robust linear models using the MASS package [87]. P-values of the coefficients for age and its interaction with sex were obtained using a robust F-Test, and 95 % confidence intervals were obtained by bootstrapping. Non-linear models were evaluated according to the distance correlation, which has proven useful at revealing complex biological relationships [88], using the energy package [89] separately for men and women. Interactions with sex were evaluated using permutation tests to detect whether the differences in the distance correlations were sex-dependent. Locally Scaterplot Smoothing (LOESS) functions were adjusted on the statistically significant lipids, using quadratic functions and selecting the optimum span between 0.2 and 0.8 on a 10-fold cross-validation procedure, minimizing the root mean square error. Lipid category enrichment was calculated using hypergeometric tests.

Clusters were obtained by dynamic time warping on the LOESS adjusted functions with the dtwclust package [90], which is optimal for time-series data, using partitional clustering with partitioning around medioids. The number of clusters (between 2 and 20) was obtained by optimizing the silhouette, dunn, COP, Davies-Bouldin, and Calinski-Harabasz indexes.

The aging crests were obtained using a modified DE-SWAN algorithm [35], selecting unique ages as the center of n-year windows and computing Mann-Whitney U tests between the data before and after that age. The window was moved in one-year steps and the total number of statistically significant lipids at each age was computed. Different temporal resolutions were obtained by computing the number of unique statistically significant lipids at each age range.

All models were adjusted for potential confounders associated with pathological aging and that could affect the metabolome, based on an exhaustive literature review (weight, height, body mass index, systolic and diastolic pressure, antecedents of depression, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac insufficiency, diabetes, renal disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tobacco consumption, as well as serum glucose, total cholesterol and HDL and LDL cholesterol levels) [56,91,92], as well as injection order, and p-values were adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg's False Discovery Rate.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Joaquim Sol: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Anna Fernàndez-Bernal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Natalia Mota-Martorell: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Meritxell Martin-Garí: Resources, Formal analysis. Èlia Obis: Resources, Formal analysis. Alba Juanes: Resources, Formal analysis. Victoria Ayala: Resources, Formal analysis. Jordi Mayneris-Perxachs: Resources. Rafel Ramos: Resources. Víctor Pineda: Resources. Josep Garre-Olmo: Resources. Manuel Portero-Otin: Resources, Formal analysis. José Manuel Fernández-Real: Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Josep Puig: Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization. Mariona Jové: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Reinald Pamplona: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Code availability

The R code used for the analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (grant ref. PID2023-152233OB-I00, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, ‘A way to build Europe’), the Catalan Government: Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (ref. 2021SGR00990) and Department of Health (ref. SLT002/16/00250), and the Diputació de Lleida (PIRS-2024) to RP. The work is also supported by the Diputació de Lleida (PIRS-2023-09), The Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI24/01431) and “La Caixa” Foundation (HR21-00259) to M.J. This work was also partially supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain) through the research grants PI15/01934, PI18/01022, PI20/01090, and PI21/01361 (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund. “A way to make Europe”), and the Catalan Government (AGAUR, #SGR2017-0734, ICREA Academia Award 2021) to J.M.F–R.

M.J. is a professor in the Serra Hunter program (Generalitat de Catalunya). J. M − P is funded by a Miguel Servet contract (CP18/00009, Co-funded by the European Social Fund “Investing in your future”) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. J.S was funded by a predoctoral PERIS contract (SLT002/16/00250) from the Catalan Government.

This study was conducted using samples/data from the Aging Imageomics Study, supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya through the Strategic Plan for Health Research and Innovation (PERIS) 2016–2020 (SLT002/16/00250). We want to particularly acknowledge the participants, to the IDIBGI Horizontal Aging Program and the IDIBGI Biobank (Biobanc IDIBGI, B.0000872), integrated in the Platform ISCIII Biomodels and Biobanks, for their collaboration.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2025.103779.

Contributor Information

Mariona Jové, Email: mariona.jove@udl.cat.

Reinald Pamplona, Email: reinald.pamplona@udl.cat.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

Data availability

The lipidomics dataset used for the analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Jové M., Portero-Otín M., Naudí A., Ferrer I., Pamplona R. Metabolomics of human brain aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014;73:640–657. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sol J., Ortega-Bravo M., Portero-Otín M., Piñol-Ripoll G., Ribas-Ripoll V., Artigues-Barberà E., Butí M., Pamplona R., Jové M. Human lifespan and sex-specific patterns of resilience to disease: a retrospective population-wide cohort study. BMC Med. 2024;22 doi: 10.1186/S12916-023-03206-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodgers J.L., Jones J., Bolleddu S.I., Vanthenapalli S., Rodgers L.E., Shah K., Karia K., Panguluri S.K. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2019;6 doi: 10.3390/JCDD6020019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poewe W., Seppi K., Tanner C.M., Halliday G.M., Brundin P., Volkmann J., Schrag A.E., Lang A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017;3:1–21. doi: 10.1038/NRDP.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hy L.X., Keller D.M. Prevalence of AD among whites: a summary by levels of severity. Neurology. 2000;55:198–204. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussbaum R.L., Ellis C.E. Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1356–1364. doi: 10.1056/NEJM2003RA020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen X., Wang C., Zhou X., Zhou W., Hornburg D., Wu S., Snyder M.P. Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging. Nat. Aging. 2024;2024:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s43587-024-00692-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler R.N., Miller R.A., Perry D., Carnes B.A., Williams T.F., Cassel C., Brody J., Bernard M.A., Partridge L., Kirkwood T., Martin G.M., Olshansky S.J. New model of health promotion and disease prevention for the 21st century. BMJ. 2008;337:149–150. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.A399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdes A.M., Glass D., Spector T.D. Omics technologies and the study of human ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:601–607. doi: 10.1038/NRG3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutledge J., Oh H., Wyss-Coray T. Measuring biological age using omics data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022;23:715–727. doi: 10.1038/S41576-022-00511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson A.A., Stolzing A. The role of lipid metabolism in aging, lifespan regulation, and age-related disease. Aging Cell. 2019;18 doi: 10.1111/ACEL.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jové M., Mota-Martorell N., Obis È., Sol J., Martín-Garí M., Ferrer I., Portero-Otin M., Pamplona R. Ether lipid-mediated antioxidant defense in Alzheimer's disease. Antioxidants. 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/ANTIOX12020293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradas I., Jové M., Huynh K., Puig J., Ingles M., Borras C., Viña J., Meikle P.J., Pamplona R. Exceptional human longevity is associated with a specific plasma phenotype of ether lipids. Redox Biol. 2019;21 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernàndez-Bernal A., Sol J., Galo-Licona J.D., Mota-Martorell N., Mas-Bargues C., Belenguer-Varea Á., Obis È., Viña J., Borrás C., Jové M., Pamplona R. Phenotypic upregulation of hexocylceramides and ether-linked phosphocholines as markers of human extreme longevity. Aging Cell. 2024 doi: 10.1111/ACEL.14429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panyard D.J., Yu B., Snyder M.P. The metabolomics of human aging: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/SCIADV.ADD6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Marcu A., Guo A.C., Liang K., Vázquez-Fresno R., Sajed T., Johnson D., Li C., Karu N., Sayeeda Z., Lo E., Assempour N., Berjanskii M., Singhal S., Arndt D., Liang Y., Badran H., Grant J., Serra-Cayuela A., Liu Y., Mandal R., Neveu V., Pon A., Knox C., Wilson M., Manach C., Scalbert A. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D608–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villeda S.A., Luo J., Mosher K.I., Zou B., Britschgi M., Bieri G., Stan T.M., Fainberg N., Ding Z., Eggel A., Lucin K.M., Czirr E., Park J.S., Couillard-Després S., Aigner L., Li G., Peskind E.R., Kaye J.A., Quinn J.F., Galasko D.R., Xie X.S., Rando T.A., Wyss-Coray T. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477:90–96. doi: 10.1038/NATURE10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villeda S.A., Plambeck K.E., Middeldorp J., Castellano J.M., Mosher K.I., Luo J., Smith L.K., Bieri G., Lin K., Berdnik D., Wabl R., Udeochu J., Wheatley E.G., Zou B., Simmons D.A., Xie X.S., Longo F.M., Wyss-Coray T. Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med. 2014;20:659–663. doi: 10.1038/NM.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dakterzada F., Jové M., Huerto R., Carnes A., Sol J., Pamplona R., Piñol-Ripoll G. Changes in plasma neutral and ether-linked lipids are associated with the pathology and progression of Alzheimer's disease. Aging Dis. 2023;14:1728. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dakterzada F., Jové M., Huerto R., Carnes A., Sol J., Pamplona R., Piñol-Ripoll G. Cerebrospinal fluid neutral lipids predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. GeroScience. 2023:1–14. doi: 10.1007/S11357-023-00989-X/FIGURES/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jové M., Naudí A., Aledo J.C., Cabré R., Ayala V., Portero-Otin M., Barja G., Pamplona R. Plasma long-chain free fatty acids predict mammalian longevity. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3346. doi: 10.1038/srep03346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sol J., Obis È., Mota-Martorell N., Pradas I., Galo-Licona J.D., Martin-Garí M., Fernández-Bernal A., Ortega-Bravo M., Mayneris-Perxachs J., Borrás C., Viña J., de la Fuente M., Mate I., Biarnes C., Pedraza S., Vilanova J.C., Brugada R., Ramos R., Serena J., Ramió-Torrentà L., Pineda V., Daunis-I-Estadella P., Thió-Henestrosa S., Barretina J., Garre-Olmo J., Portero-Otin M., Fernández-Real J.M., Puig J., Jové M., Pamplona R. Plasma acylcarnitines and gut-derived aromatic amino acids as sex-specific hub metabolites of the human aging metabolome. Aging Cell. 2023 doi: 10.1111/ACEL.13821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jové M., Mota-Martorell N., Pradas I., Galo-Licona J.D., Martín-Gari M., Obis È., Sol J., Pamplona R. The lipidome fingerprint of longevity. Molecules. 2020;25 doi: 10.3390/molecules25184343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagen R.M., Rodriguez-Cuenca S., Vidal-Puig A. An allostatic control of membrane lipid composition by SREBP1. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2689–2698. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hulbert A.J., Kelly M.A., Abbott S.K. Polyunsaturated fats, membrane lipids and animal longevity. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2014;184:149–166. doi: 10.1007/s00360-013-0786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornburg D., Wu S., Moqri M., Zhou X., Contrepois K., Bararpour N., Traber G.M., Su B., Metwally A.A., Avina M., Zhou W., Ubellacker J.M., Mishra T., Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose S.M., Kavathas P.B., Williams K.J., Snyder M.P. Dynamic lipidome alterations associated with human health, disease and ageing. Nat. Metab. 2023;5:1578–1594. doi: 10.1038/S42255-023-00880-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ansoleaga B., Jové M., Schlüter A., Garcia-Esparcia P., Moreno J., Pujol A., Pamplona R., Portero-Otín M., Ferrer I. Deregulation of purine metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beyene H.B., Olshansky G., Smith A.A.T., Giles C., Huynh K., Cinel M., Mellett N.A., Cadby G., Hung J., Hui J., Beilby J., Watts G.F., Shaw J.S., Moses E.K., Magliano D.J., Meikle P.J. High-coverage plasma lipidomics reveals novel sex-specific lipidomic fingerprints of age and BMI: evidence from two large population cohort studies. PLoS Biol. 2020;18 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burla B., Arita M., Arita M., Bendt A.K., Cazenave-Gassiot A., Dennis E.A., Ekroos K., Han X., Ikeda K., Liebisch G., Lin M.K., Loh T.P., Meikle P.J., Orešič M., Quehenberger O., Shevchenko A., Torta F., Wakelam M.J.O., Wheelock C.E., Wenk M.R. MS-based lipidomics of human blood plasma: a community-initiated position paper to develop accepted guidelines. J. Lipid Res. 2018;59:2001–2017. doi: 10.1194/JLR.S087163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torta F., Hoffmann N., Burla B., Alecu I., Arita M., Bamba T., Bennett S.A.L., Bertrand-Michel J., Brügger B., Cala M.P., Camacho-Muñoz D., Checa A., Chen M., Chocholoušková M., Cinel M., Chu-Van E., Colsch B., Coman C., Connell L., Sousa B.C., Dickens A.M., Fedorova M., Eiríksson F.F., Gallart-Ayala H., Ghorasaini M., Giera M., Guan X.L., Haid M., Hankemeier T., Harms A., Höring M., Holčapek M., Hornemann T., Hu C., Hülsmeier A.J., Huynh K., Jones C.M., Ivanisevic J., Izumi Y., Köfeler H.C., Lam S.M., Lange M., Lee J.C., Liebisch G., Lippa K., Lopez-Clavijo A.F., Manzi M., Martinefski M.R., Math R.G.H., Mayor S., Meikle P.J., Monge M.E., Moon M.H., Muralidharan S., Nicolaou A., Nguyen-Tran T., O'Donnell V.B., Orešič M., Ramanathan A., Riols F., Saigusa D., Schock T.B., Schwartz-Zimmermann H., Shui G., Singh M., Takahashi M., Thorsteinsdóttir M., Tomiyasu N., Tournadre A., Tsugawa H., Tyrrell V.J., van der Gugten G., Wakelam M.O., Wheelock C.E., Wolrab D., Xu G., Xu T., Bowden J.A., Ekroos K., Ahrends R., Wenk M.R. Concordant inter-laboratory derived concentrations of ceramides in human plasma reference materials via authentic standards. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:8562. doi: 10.1038/S41467-024-52087-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi C., Huynh K., Schooneveldt Y., Olshansky G., Liang A., Wang T., Beyene H.B., Dakic A., Wu J., Cinel M., Mellett N.A., Watts G.F., Hung J., Hui J., Beilby J., Curran J.E., Blangero J., Moses E.K., Simes J., Tonkin A.M., Kritharides L., Sullivan D., Tonkin A., Aylward P., Colquhoun D., Glasziou P., Harris P., Hunt D., Keech A., MacMahon S., Magnus P., Newel D., Nestel P., Sharpe N., Shaw J., Simes R.J., Thompson P., Thomson A., West M., White H., Thomson A., Simes S., Colquhoun D., Hague W., MacMahon S., Simes R.J., Simes R.J., Glasziou P., Caleo S., Hall J., Martin A., Mulray S., Barter P., Beilin L., Collins R., McNeil J., Meier P., Willimott H., Harris P., Hague W., Smithers D., Tonkin A., Wallace P., Willimott H., Hunt D., Baker J., Aylward P., Harris P., Hobbs M., Thompson P., Sharpe N., Hunt D., West M., Thompson P., White H., Aylward P., Colquhoun D., Sullivan D., Keech A., Thompson P., MacMahon S., Tonkin A., West M., White H., Anderson N., Hankey G., Simes R.J., Simes S., Watson J., Simes R.J., Sharpe N., Thomson A., Tonkin A., White H., Hague W., Baker J., Arulchelvam M., Chup S., Daly J., Hanna J., Leach A., Lee M., Loughhead J., Lundie-Jenkin H., Morrison J., Martin A., Mulray S., Netting S., Nguyen A., Pater H., Philip R., Pinna G., Rattos D., Ryerson S., Sazhin V., Simes S., Walsh R., Keech A., Simes R.J., Clague A., Mackie M., Yallop J., Boss K., MacMahon S., Whiting M., Shepard M., Leach J., Gandy M., Joughin J., Seabrook J., Abraham R., Allen J., Bates F., Beinart I., Breed E., Brown D., Bunyan N., Calvert D., Campbell T., Condon-Paoloni D., Conway B., Coupland L., Crowe J., Cunio N., Cuthbert B., Cuthbert N., D'Arcy S., Davidson P., Dwyer B., England J., Friend C., Fulcher G., Grant S., Hellestrand K., Kava M., Kritharides L., McGill D., McKee H., McLean A., Neaverson M., Nelson G., O'Neill M., Onuma C., O'Reilly F., Owensby A., Owensby D., Padley J., Parnell G., Paterson S., Pawsey C., Portley R., Quinn K., Ramsay D., Russell M., Ryan J., Sambrook B., Shields L., Silberberg J., Sinclair S., Sullivan D., Taverner P., Taylor D., Taylor M., Threlfall M., Turner J., Viles A., Waites J., Walker R., Walsh W., Wee K., West P., Wikramanayake R., Wilcken D., Woods J., Barnett R.K., Bogetic Z., Briggs H., Broughton A., Brown L., Buncle A., Calafiore P., Carrick L., Cavenett Y., Champness L., Clark R., Connor H., Counsell J., Deague J., Derwent-Smith G., Driscoll A., Feldtmann B., Fisher L., Forge B., Hamer A., Harrap H., Hodgens S., Hooten M., Hurley J., Jackson B., Johns J., Krafchek J., Larwill H., Lyall I., Marks S., Martin M., Mason B., McCabe J., Medley C., Morgan L., Mullan L., Ogilvy D., Phelps G., Phillips P., Prendergast H., Rose D., Rudge G., Ryan W., Sallaberger M., Savige G., Sia B., Soward A., Steinfort C., Tankard K., Tippett J., Tyack B., Voukelatis J., Wahlqvist M., Walker N., Whitten S., Yee R., Zanoni M., Ziffer R., Anderson K., Aroney G., Atkinson C., Boyd K., Bradfield R., Cameron G., Careless D., Carle A., Carroll P., Carruthers T., Chaseling D., Cooke B., Coverdale S., Currie B., d'Emden M., Ekin F., Elder R., Elsley T., Ferry L., Gnanaharan C., Graham K., Gunawardane K., Hadfield C., Halliday C., Halliday R., Heyworth A., Hicks B., Hicks P., Htut T., Hughes L., Humphries J., LeGood H., Nye J., O'Brien D., Real G., Roberts K., RossLee L., Sampson J., Scott I., Smith H., Smith-Orr V., Tan Y., Wicks B., Wicks J., Woodhouse S., Bradley J., Callaway L., Calvert A., Crettenden J., Dufek A., Dunn B., Dunphy C., Gow D., Hamilton-Craig I., Herewane K., Keynes S., McLeay L., McLeay R., Ng L., Thomas C., Tideman P., Wilson L., Yeend R., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Bradshaw P., Brooks M., Burton R., Garrett J., Gotch-Martin K., Hargan J., Hockings B., Lane G., Ross S., Cutforth R., D'Silva D., Hitchener W., Kimber V., Kirkland G., Neid P., Parkes R., Singh B., Singh C., Smith M., Smith S., Templer M., Whitehouse N., Allen-Narker R., Anandaraja R., Anandaraja S., Barclay P., Baskaranathan S., Bridgman P., Brown J., Bruning J., Calton J., Clague A., Clark M., Clarke D., Cook T., Coxon R., Denton M., Doone A., Easthope R., Elliott J., Ellis C., FosterPratt P., Frenneux C., Frenneux M., Friedlander D., Fry D., Gibson L., Gluyas M., Hall A., Hall K., Hamer A., Hart H., Healy P., Hedley J., Heuser P., Ikram H., Jardine D., Kenyon J., King H., Kirk T., Lawson T., Leslie P., Lewis G., Low E., Luke R., Mann S., McClean D., McHaffie D., Nairn L., Patel H., Pearce L., Ramanathan K., Rankin R., Reddy J., Reuben S., Ronaldson R., Roy D., Roy H., Scobie P., Scott D., Scott J., Skjellerup K., Stewart R., Walters D., Wilkins T., Vitanachy A., Wright P., Zambanini A., Shaw J.E., Magliano D.J., Salim A., Giles C., Meikle P.J. Statin effects on the lipidome: predicting statin usage and implications for cardiovascular risk prediction. J. Lipid Res. 2025;66 doi: 10.1016/J.JLR.2025.100800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caballero F.F., Struijk E.A., Lana A., Buño A., Rodríguez-Artalejo F., Lopez-Garcia E. Plasma acylcarnitines and risk of lower-extremity functional impairment in older adults: a nested case–control study. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1–8. doi: 10.1038/S41598-021-82912-Y. SUBJMETA=2422,320,45,53,631,692;KWRD=METABOLOMICS,PROGNOSTIC+MARKERS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauvais-Jarvis F., Bairey Merz N., Barnes P.J., Brinton R.D., Carrero J.J., DeMeo D.L., De Vries G.J., Epperson C.N., Govindan R., Klein S.L., Lonardo A., Maki P.M., McCullough L.D., Regitz-Zagrosek V., Regensteiner J.G., Rubin J.B., Sandberg K., Suzuki A. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396:565–582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holven K.B., Roeters van Lennep J. Sex differences in lipids: a life course approach. Atherosclerosis. 2023;384 doi: 10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2023.117270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehallier B., Gate D., Schaum N., Nanasi T., Lee S.E., Yousef H., Moran Losada P., Berdnik D., Keller A., Verghese J., Sathyan S., Franceschi C., Milman S., Barzilai N., Wyss-Coray T. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1843–1850. doi: 10.1038/S41591-019-0673-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trayssac M., Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Role of sphingolipids in senescence: implication in aging and age-related diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2018;128:2702. doi: 10.1172/JCI97949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meikle P.J., Summers S.A. Sphingolipids and phospholipids in insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017;13:79–91. doi: 10.1038/NRENDO.2016.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hannun Y.A., Obeid L.M. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:175–191. doi: 10.1038/NRM.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietveld A., Simons K. The differential miscibility of lipids as the basis for the formation of functional membrane rafts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:467–479. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4157(98)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posse de Chaves E., Sipione S. Sphingolipids and gangliosides of the nervous system in membrane function and dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1748–1759. doi: 10.1016/J.FEBSLET.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang X., Withers B.R., Dickson R.C. 2013. Sphingolipids and Lifespan Regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guillas I., Kirchman P.A., Chuard R., Pfefferli M., Jiang J.C., Jazwinski S.M., Conzelmann A. C26-CoA-dependent ceramide synthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is operated by Lag1p and Lac1p. EMBO J. 2001;20:2655–2665. doi: 10.1093/EMBOJ/20.11.2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schorling S., Vallée B., Barz W.P., Riezman H., Oesterhelt D. Lag1p and Lac1p are essential for the Acyl-CoA-dependent ceramide synthase reaction in Saccharomyces cerevisae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3417–3427. doi: 10.1091/MBC.12.11.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao R.P., Yuan C., Allegood J.C., Rawat S.S., Edwards M.B., Wang X., Merrill A.H., Acharya U., Acharya J.K. Ceramide transfer protein function is essential for normal oxidative stress response and lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0705049104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Q., Gong Z.J., Zhou Y., Yuan J.Q., Cheng J., Tian L., Li S., Da Lin X., Xu R., Zhu Z.R., Mao C. Role of Drosophila alkaline ceramidase (Dacer) in Drosophila development and longevity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:1477–1490. doi: 10.1007/S00018-010-0260-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkowitz L., Salazar C., Ryff C.D., Coe C.L., Rigotti A. Serum sphingolipid profiling as a novel biomarker for metabolic syndrome characterization. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/FCVM.2022.1092331/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]