Abstract

The preparation of specifically iodine-125 (125I)-labeled peptides of high purity and specific activity represents a key tool for the detailed characterization of their binding properties in interaction with their binding partners. Early synthetic methods for the incorporation of iodine faced challenges such as harsh reaction conditions, the use of strong oxidants and low reproducibility. Herein, we review well-established radiolabeling strategies available to incorporate radionuclide into a protein of interest, and our long-term experience with a mild, simple and generally applicable technique of 125I late-stage-labeling of biomolecules using the Pierce iodination reagent for the direct solid-phase oxidation of radioactive iodide. General recommendations, tips, and details of optimized chromatographic conditions to isolate pure, specifically 125I-mono-labeled biomolecules are illustrated on a diverse series of (poly)peptides, ranging up to 7.6 kDa and 67 amino acids (aa). These series include peptides that contain at least one tyrosine or histidine residue, along with those featuring disulfide crosslinking or lipophilic derivatization. This mild and straightforward late-stage-labeling technique is easily applicable to longer and more sensitive proteins, as demonstrated in the cases of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGF-BP-3) (29 kDa and 264 aa) and the acid-labile subunit (ALS) (93 kDa and 578 aa).

Keywords: 125I-labeling of peptides, Late-stage peptide labeling, Site-specific labeling, Radiohalogenated prosthetic groups, Radiochemical stability, Intramolecular effect of 125I decay, High specific activity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Comprehensive review of radiohalogenation methods for biomolecular labeling.

-

•

Versatile radioiodination strategy for sensitive peptides and protein chains.

-

•

Simplified late-stage labeling protocol suitable for large proteins.

-

•

Optimized radio-HPLC conditions for isolating pure mono-iodinated probes.

-

•

General protocol adaptable for labeling with other iodine radioisotopes.

1. Introduction

The versatility of peptides in terms of their structure, biological activity, and potential applications has led to a resurgence of interest in their pharmacological properties, chemistry, and biology. Radionuclide-labeled peptides and proteins are extensively used in many areas of biochemistry, pharmacology, and medicine [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. For example, labeled peptides are frequently employed as tracer molecules in quantitative determinations, such as measuring hormone and hormone-receptor concentrations, or kinetic and equilibrium studies of both agonist and antagonist interactions with receptors [5]. Peptides labeled with radioisotopes of iodine are widely used in biological research, biodistribution, diagnostic imaging, and radiotherapy [1,6]. The first radiohalogenated peptide used in humans was the somatostatin analog 123I-204-090, developed by Krenning et al. [7], in 1989. The first radioiodinated peptide approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was tositumomab (Bexxar, 131I–B1 mAb), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) conjugated with the mixed β/γ-emitter 131I [8,9]. It received FDA approval in 2003 for the radioimmunotherapy treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. This drug is synthesized via direct labeling, using the direct electrophilic substitution method with Iodo-gen. The antigen-binding specificity displayed by mAbs is increasingly being harnessed to deliver radionuclides for cancer diagnosis and treatment [10]. Another notable example is 131I-omburtamab, a 131I-labeled mouse mAb prepared using Iodo-gen direct method. It was developed for the treatment of neuroblastomas, targeting both pediatric metastatic disease (including neonatal cases) and adult patients [11,12]. In June 2017, 131I-omburtamab received breakthrough therapy status for neuroblastoma in the United States [13].

Iodine-125 (125I) is particularly favored due to its suitable half-life (60 days), ease of labeling, and availability. It is commonly used for labeling of bulky molecules, such as (poly)peptides in saturation studies, competition radioligand binding assays, animal imaging, and in vivo biodistribution and clearance studies [3,[14], [15], [16]]. The long half-life of 125I also facilitates post mortem graphical analyses of tissue sections [17,18]. Over the last two decades, the computed tomography (CT)-guided radioactive 125I brachytherapy has been investigated for treating primary and even metastatic cancers of head and neck, thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, and spinal regions [19,20]. 125I-labeled proteins can be efficiently used for in vivo micro-imaging in small-animal studies to acquire high-resolution single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT) images. When these images are fused with x-ray CT data, they provide accurate anatomical localization of organ- and tissue-specific activities of the injected 125I-labeled pharmaceutical [14,21]. Such studies require the precise determination of very low amounts of labeled peptides and proteins, which can be accurately measured using tracer molecules labeled with high specific (molar) activity.

There are well-established radiolabeling strategies available to incorporate a radionuclide into a protein of interest (Scheme 1). The choice of labeling approach primarily depends on the intended application of the labeled material and the physical properties of the used radionuclide. Peptides containing the highly activated phenolic ring in tyrosine residues, and imidazole ring in histidine residues can be directly modified by electrophilic radioiodine [13,22,23]. Alternatively, peptides lacking iodinatable functional group, as well as macromolecules sensitive to oxidative reagents, can be labeled indirectly through conjugation with prosthetic groups, or bifunctional chelators that can bind radionuclide on one site and a peptide on another site. Many reviews describe indirect macromolecule modification using a conjugation group (e.g., active ester, hydrazide, and isothiocyanate) with a small prosthetic group that have been previously radiolabeled [2,3,24]. Kręcisz et al. [25] reported an overview of prosthetic methods using cyclic or acyclic bifunctional chelators for labeling proteins with radionuclides such as 99mTc, 64Cu, 68Ga, 90Y, and 177Lu, which are applied in nuclear medicine. For the successful application of a metal complex in vivo, it is necessary to consider and optimize parameters such as the chelator's charge and its lipophilicity, biological and physical half-lives, rapid complex formation, and the high complex stability. Diagnostic radionuclides are employed in molecular imaging modalities applied in nuclear medicine, including SPECT and positron emission tomography (PET). Li et al. [26] recently published a review of developments of macrocyclic chelators for innovative PET radiopharmaceuticals. Tolmachev and Stone-Elander [27] discussed numerous methods for binding prosthetic groups carrying various positron-emitting nuclides, including both radiohalogens (e.g., 18F, 124I, and 76Br) and radiometals (e.g., 44Sc, 52gMn, 64Cu, 68Ga, and 89Zr), with recommendations based on the biological characteristics of the tracers. Most prosthetic groups are designed to conjugate with amino groups (N-terminus, lysines) and thiol groups (cysteines). The advantage of this approach is that proteins typically contain many Lys/Cys residues, increasing the likelihood of successful labeling. However, the drawback is that the abundance of these amino acids (aa) can lead to variability in the number and location of conjugations, both within a single batch and between different preparations.

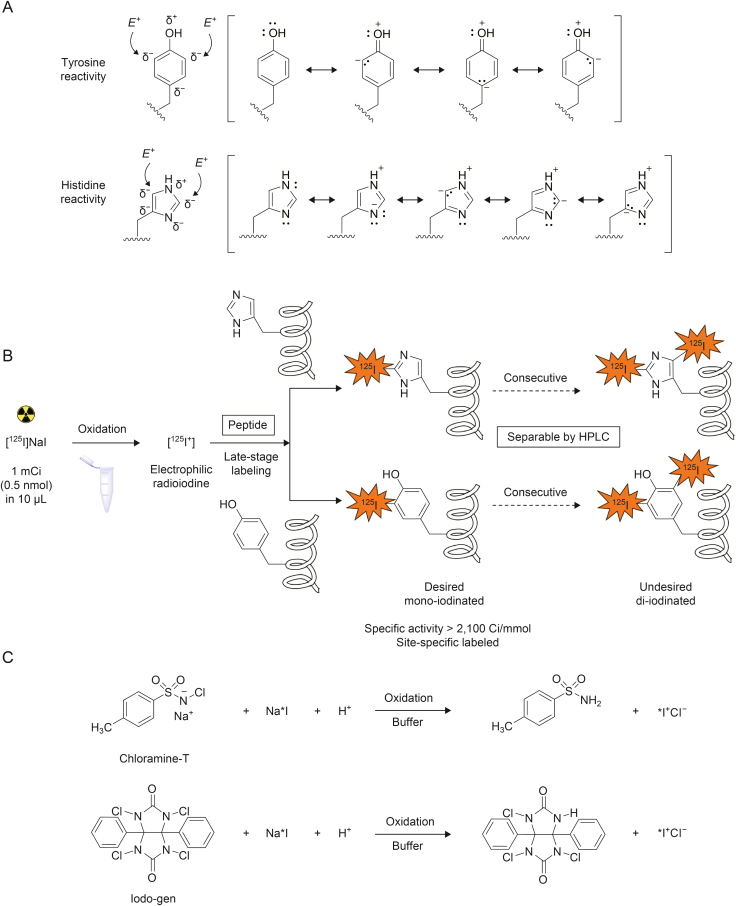

Scheme 1.

General strategies for protein radionuclide labeling.

A review article published by Wilbur [28] provided a comprehensive overview of methods for protein labeling using various types of radiohalogenated prosthetic groups, i.e., active esters, imidate esters, aldehydes, isocyanates, activated halides, maleimides, hydrazides, diazonium salts, and diazirines. These groups allow labeling of multiple reactive functional groups within aa structures, such as amines, alcohols, carboxylic acids, and thiols. However, attaching a bulky prosthetic group to a small peptide can significantly affect its binding affinity to the receptor and the in vivo pharmacokinetics of the radiolabeled peptide.

In this work, we explore the universality of a direct 125I-radioiodination technique and demonstrate its applicability on structurally diverse peptides, with a detailed focus on the highly relevant (poly)peptides currently being studied worldwide. These include neuropeptides involved in the regulation of energy metabolism, and hormones from the insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system, which are essential for controlling development, growth, and overall metabolic homeostasis. Insulin and its two related growth factors, IGF-1 and IGF-2, are part of a complex protein network that includes not only these hormones but also their receptors and IGF-binding proteins (IGF-BPs). The biological effects of insulin-like hormones are determined by their affinities for receptors and BPs, as well as the tissue distribution of all components. However, the exact mechanism of receptor binding and signal transduction remains unclear and requires further investigation, ensuring ongoing high demand for these labeled biomolecules. Any malfunction in this hormone system can lead to serious health issues, such as diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, growth retardation, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [29,30].

To study binding interactions within the hormone-receptor system and to develop new hormone derivatives for medical applications, highly sensitive binding assays are essential. Labeling with 125I allows site-specific modification that preserves a protein's binding properties while providing the sensitivity needed to study interactions at subnanomolar concentrations. Compared to fluorescent labels, which are often bulky and can alter peptide-binding properties, 125I-mono-labeling offers distinct advantages, including the ability to detect extremely low amounts of bound hormones at the femtomole (fmol) level [31,32].

The purpose of this work is to introduce the main strategies commonly used to radioiodinate peptides of interest with a focus on details of site-specific labeling using a straightforward oxidative method demonstrated on various biomolecules.

2. The choice of radioisotope

2.1. Internal vs. external isotopic labels

The choice of radioisotope for labeling determines the labeling strategy, its cost, the sequence of laboratory work and its safety, and the applicability of the resulting tracer. Generally, isotopic labels can be categorized as internal and external [33]. With an internal label an existing atom in a ligand molecule is replaced with a radioactive isotope of that atom (e.g., replacing 12C with 14C or 1H with 3H) making the tracer virtually identical to the unlabeled ligand. Tracers with an internal label are used in research assays for detecting small organic molecules such as pharmaceuticals, drugs, agrochemicals, and intermediates [34,35]. In contrast, an external label involves a covalently linked radioactive isotope (e.g., 125I) to a ligand molecule. A tracer with an external label is not identical with the unlabeled ligand, although its behavior may be indistinguishable in practice. The radioactive label must be incorporated into an aa residue located outside the site of the tracer's biological activity [1]. It is always necessary to verify that the physicochemical properties of an iodinated tracer remain unchanged compared to its unlabeled analog through appropriate assays [31,36,37].

For the counting of weak β-emitters (such as 14C or 3H), a solution of a labeled ligand in a scintillation cocktail needs to be prepared. In contrast, γ-counting of the 125I nuclide can be performed directly without the need of an expensive scintillation counting system (Table 1), ensuring a high-throughput screening [33]. Additionally, no preparation of scintillation sample is required, resulting in significant savings in labor and materials. The specific (molar) activities of γ-emitting isotopes are much higher, with a single 125I atom per molecule having specific activity of 80 TBq/mmol (2,170 Ci/mmol) compared with those of β-emitters (e.g. one 3H atom per molecule, with specific activity of 1.1 TBq/mmol (29.1 Ci/mmol)). This difference reduces counting times or enables the detection of smaller amounts of tracer within a dedicated counting period. Furthermore, the generation of radioactive waste is significantly reduced when liquid scintillation counting is avoided.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of the commonly used γ-emitting isotope 125I with those of β-emitters (14C and 3H) [33].

| Nuclide | Half-life t1/2 |

Atoms/Ci | Detection efficiency (%)a | Number of atoms equivalent to one detectable atom of 125I |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125I | 59.4 days | 1.77 × 1017 | 78–82 (γ-counting) | 1 |

| 14C | 5,730 years | 9.65 × 1021 | 85–95 (Liquid scintillation counting) | 37,010 |

| 3H | 12.3 years | 2.08 × 1019 | 55–60 (Liquid scintillation counting) | 51.6 |

Depending on the specific radiometric instrument used for counting.

2.2. Radioisotopes of iodine

There are thirty-seven known isotopes of iodine, four of which (123I, 124I, 125I, and 131I) have found practical applications as tracers and diagnostic and therapeutic agents in research and medicine [1,22,38]. The nuclides 123I, 125I, and 131I are commonly used as imaging agents for SPECT [3], while 124I is used for PET [25,39]. A promising isotope for future PET imaging is the relatively short-lived isotope 120I (t1/2 = 81 min), which may serve as an alternative to 124I. Isotopes 123I, 125I, and especially 131I are utilized in (human) radiotherapy [19]. 125I is primarily used in research studies; its soft gamma emission is readily detectable, and it is easy to protect personnel from internal contamination. The sixty-day half-life allows labeled materials to be prepared and stored for extended periods (typically 1–3 months) [16,37,[40], [41], [42]], depending on their chemical and radiochemical stability. In contrast, 131I has a shorter half-life of eight days and higher specific activity (Table 2). However, this shorter half-life means that activity in a sample decreases day by day, necessitating more often preparation of 131I-labeled compounds [6]. The more penetrating radiation from 131I also requires additional protection for radiosynthetic chemists involved in the synthesis and use of radioiodinated compounds. A labeling procedure developed for one isotope of iodine should be easily adaptable to another, considering the isotope's half-life and the chemical form of the supplied radioiodine [43].

Table 2.

Radioiodine isotopes commonly used in radioimaging and radiotherapy.

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Emission | Energymax (MeV) |

Specific activity (Ci/g) |

Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 123I | 13.2 h | γ (EC) | 0.159 | 1.9 × 106 | SPECT imaging |

| 124I | 4.2 days | β+ | 2.135 | 2.5 × 105 | PET imaging and radiotherapy |

| 125I | 59.4 days | γ (EC) | 0.035 | 1.7 × 104 | Preclinical research, small animal imaging, microSPECT, in vitro and in vivo studies, and radiotherapy |

| 131I | 8.0 days | β− | 0.606 | 1.2 × 105 | Therapy for hyperthyroidism and SPECT imaging |

EC: electron capture; SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography.

3. Radioiodination techniques

3.1. Direct methods

The direct method of radiolabeling with 125I typically involves the late-stage incorporation of 125I into either tyrosine residues or less reactive histidine residues [44,45] that are activated via electrophilic halogenation by electron-donating groups. This approach allows the radioactive nuclide to be introduced directly into the molecule of interest without any need for prior synthetic modification. The process is carried out by treating samples with [125I]NaI in the presence of an oxidizing reagent, which generates electrophilic iodine (125I+) [46]. In tyrosine residues, the phenolic hydroxyl group is positioned para to the aryl conjugation to the peptide, and iodination occurs at the ortho positions relative to the hydroxyl group. Moreover, the OH group possesses both a strong positive mesomeric effect and a negative inductive effect, allowing mono- or di-substitution of iodine at these sites (Scheme 2A) [47,48].

Scheme 2.

Electrophilic iodination on tyrosine and histidine moiety. (A) Resonance structures of tyrosine and histidine residues showing electron delocalization. Arrows indicate the positions for electrophilic substitution. E+ stays for electrophile. Reprinted from Refs. [[47], [48]] with permission. (B) Direct electrophilic iodination primarily results in iodination of tyrosine and histidine. (C) Formation of the reactive electrophilic radioiodine by Iodo-gen or chloramine-T. HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

Many techniques have been developed for incorporation of 125I into peptides [43]. The general requirement for radiohalogenation of proteins is simple and rapid workup that provides high radiochemical yield (RCY), purity, and high specific activity. The covalently bound label has to be in a chemically stable, non-exchangeable position. Direct electrophilic iodination primarily results in iodination of tyrosine and, to a lesser extent, histidine (less reactive, requiring longer reaction times and slightly higher pH). The formation of di-iodinated tyrosyl moieties depends on the stoichiometry of the peptide to Na∗I ratio used in the reaction. Importantly, undesirable di- and over-iodinated species, which may significantly alter peptide-binding properties compared to intact peptide, can be separated using appropriate high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods. (Scheme 2B). Although only microgram quantities of oxidants are used, the stoichiometry of the in-situ oxidizing reagent is often much greater than that of the halide. This necessitates the use of oxidants that do not adversely affect the molecules being labeled. For peptides containing a tyrosine or histidine residue, oxidative techniques generate reactive intermediate electrophilic species of 125I+ from commercially available sources of sodium [125I]iodide (Table 3) [49,50]. The most common oxidizing reagents used for this purpose are the N-haloamine compounds chloramine-T and Iodo-gen, as shown in Scheme 2C. The advantages and limitations of the most widely used 125I-radioiodination techniques are discussed in detail below.

Table 3.

Direct radioiodination techniques used for peptide labeling.

| Entry | Technique | Commonly used | Chemical structure | Reaction nature | Quenching | Inventors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iodine exchange | No | ICl/Na∗I | Homogeneous | No | McFarlane, 1958 (DOI: 10.1038/182053a0) |

| 2 | Chloramine-T | Yes |  |

Homogeneous | Yes | Greenwood et al., 1963 (DOI: 10.1042/bj0890114) |

| 3 | Enzymatic | Yes | LPO + H2O2 | Homogeneous | Dilution | Marchalonis, 1969 (DOI: 10.1042/bj1130299) |

| 4 | Iodine vaporization | No | – | Homogeneous | No | Butt, 1972 (DOI: 10.1677/joe.0.0550453) |

| 5 | Chlorine/hypochlorite | No | NaOCl | Homogeneous | Reducing reagent | Redshaw and Lynch, 1974 (DOI: 10.1677/joe.0.0600527) |

| 6 | Electrolysis | No | – | Homogeneous | No | Pennisi and Rosa, 1964 (PMID: 5383775) |

| 7 | Iodo-gen (Pierce™ iodination reagent) | Yes |  |

Heterogeneous | No | Fraker and Speck, 1978 (DOI: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91322-0) |

| 8 | Iodo-gen Pierce™ iodination tubes | Yes |  |

Heterogeneous | No | – |

| 9 | Iodo-beads (Pierce™ iodination Beads) | Yes |  |

Heterogeneous | No | Markwell, 1982 (DOI: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90025-2) |

| 10 | NH2Cl | – | NH2Cl | Homogeneous | Yes | Kumar and Woolum, 2021 (DOI: 10.3390/molecules26144344) |

−: no data; LPO: lactoperoxidase; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide.

3.1.1. Iodine exchange radioiodination

The iodine exchange method uses radioactive iodine, such as 125I, in the form of iodide and converts it to [125I]ICl through a very rapid chemical exchange with non-radioactive ICl [51,52] in a buffered solution at pH 8. Because the only oxidizing agent present during the iodination procedure is the ICl itself, the protein is protected from potential damage caused by other oxidizing agents (Table 3, entry 1). This is particularly important when working with labile proteins [51], as other methods utilizing I− to I+ oxidation (e.g. chloramine-T radioiodination) have the potential to induce protein oxidation. However, the iodine exchange method has also disadvantages, including unpredictable and low specific activity (with only a few percent of iodine incorporation) and the rapid hydrolysis of the reagent by water. This was a pioneering method for iodine labeling and has been already entirely replaced by more efficient techniques.

3.1.2. Chloramine-T radioiodination

Chloramine-T or N-chloro-4-methylbenzene-1-sulfonamide (Table 3, entry 2), is a traditional and widely used oxidative reagent that enables a high degree of radioiodination [46]. As a potent oxidizing agent, it converts iodide to a more reactive form. The procedure is straightforward, requiring only simple mixing of solutions of the peptide to be labeled, sodium iodide, and chloramine-T. Then, the reaction has to be terminated by adding a reducing agent, such as sodium metabisulfite. The simplicity of the technique explains its widespread acceptance.

However, due to the homogenous nature of the reaction, chloramine-T can cause significant destruction of the labeled peptide, leading to oxidation of the sensitive aa, such as methionine to its sulfoxide analog and tryptophan to oxindole [43,49], or even to the protein denaturation. Since chloramine-T is a water-soluble reagent and the reaction proceeds readily in the solution phase, higher incorporation of radioactive iodine can be obtained in a shorter time than when using insoluble or immobilized oxidants [44].

Wajchenberg et al. [53] communicated that 125I-insulin prepared using the chloramine-T method provided lower immunoreactivity and greater denaturation in comparison with the iodoinsulin prepared by an enzymatic method. Chen et al. [17] documented radiosynthesis and pharmacokinetic data of 125I-labeled cyclic pentapeptide c(RGDyK), which achieved a RCY of 70%–90% and a specific activity of 63 TBq/mmol (1,700 Ci/mmol). However, the monofunctional methoxy-PEG (polyethylene glycol) modified 125I-c(RGDyK)-mPEG derivative was isolated with a much lower specific activity of 5.5–7.4 TBq/mmol (150–200 Ci/mmol).

3.1.3. Enzymatic radioiodination

The gentler enzymatic lactoperoxidase (LPO)/hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) oxidizing system is also commonly used for peptide and protein labeling (Table 3, entry 3) [40,53]. LPO is a member of the heme-containing peroxidase enzyme family. The general mechanism was suggested by Morrison and Schonbaum, who proposed that peroxidase catalysis begins with the oxidation of peroxidases by H2O2. The resulting derivative, compound LPOox, then acts as the oxidant for the halide ions. Such reactions can lead to either the formation of hypohalide or the halogenation of the enzyme apoprotein, followed by a transhalogenation to a final substrate [54]. A recent study reported that the reaction is initiated when H2O2 oxidizes iron bound to the porphyrin, forming an Fe O moiety (LPOox) [55]. At low (physiological) concentrations of H2O2, the halogenation cycle continues with the reaction of Na∗I with LPOox to form a ternary complex of lactoperoxidase with iodide and hydrogen peroxide (LPI). The oxygen bound to the iron is then transferred to generate an oxidized acceptor, a hypohalide ion, which participates in subsequent peptide labeling (Scheme 3). However, at high (non-physiological) H2O2 concentrations, a complete irreversible inactivation of LPO can occur [55]. The halogenation of tyrosine and histidine residues in proteins can also take place on the enzyme itself, which may make the LPO-catalyzed iodination more selective.

Scheme 3.

Enzymatic radioiodination on peptide chain. Lactoperoxidase (LPO)-catalyzed halogenation cycle. H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; LPI: a ternary complex of lactoperoxidase with iodide and hydrogen peroxide.

However, peroxidase-catalyzed halogenation is not routinely used due to issues with low transferability, reproducibility, and RCYs, primarily because the enzyme can undergo self-iodination [56,57]. Alternatively, LPO can be attached to a solid phase (lacto-beads) and removed by centrifugation [58]. It has been reported that tracers prepared by this technique experience less damage compared to those prepared by the chloramine-T method [37,53,59]. Nonetheless, the preparation of the reagents and the reaction conditions for this method are more technically demanding than those for the chloramine-T procedure, and are subject to greater variability in optimal reaction conditions. For example, the synthetic growth-hormone-releasing dodecapeptide Tyr-Ala-hexarelin was successfully 125I-labeled at the Tyr residue using an enzymobead iodination kit, yielding high specific activity of 81 TBq/mmol (2,200 Ci/mmol) [58]. Similarly, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) derivative, Arg34Lys26(Nε-(L-glutamyl(Nα-palmitoyl)))-GLP-1 (7–37) (NN2211) was enzymatically radio-labeled for absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion studies (ADME) [56]. Both [125I]NN2211 and [127I]NN2211 derivatives were iodinated at Tyr19 with RCY > 50% by using this enzymatic method.

3.1.4. Pierce™ iodination reagent (Iodo-gen) radioiodination

Oxidizing reagents can potentially damage proteins, particularly sensitive residues like methionine and tryptophan. The Pierce™ iodination reagent (Iodo-gen, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3α,6α-diphenyl-glycoluril) (Scheme 2C) is milder than chloramine-T but equally effective at iodine activation (Table 3, entry 7) [43,49]. Using this reagent in a solid-phase procedure makes the iodination gentler on sensitive proteins [60,61]. Unlike chloramine-T, the Pierce iodination reagent is insoluble in water, therefore can be coated on the walls of the iodination vessels to enable solid-phase oxidative activation. Protein iodination with this reagent occurs along the vessel walls [37]. Consequently, no reducing agent is needed, and minimal damage to the protein is observed because the reaction is terminated simply by decanting the reaction solution away from the coated Pierce iodination reagent or by filtration through syringe filters. The effect of surface reaction slows the rate of iodine incorporation into macromolecules from the extremely rapid 30 s reaction of soluble chloramine-T to a more convenient 2–30 min to obtain a similar yield [44]. A slower iodination process allows more control over the level of iodine derivatization.

Residual 125I+ iodonium species are quenched by adding an excess of quickly iodinated and easily separable material, such as BSA. This method offers better outcomes compared with those of other techniques, especially in terms of peptide recovery, as the micro-scale syntheses consistently achieve high levels of radioactivity incorporation while minimizing oxidative damage to a protein [49]. Salacinski et al. reported that Iodo-gen gives higher iodine incorporation with less damage than chloramine-T and LPO for the most proteins and peptides tested [37]. Koppe et al. [62] reported labeling of mAb MN-14 with Iodo-gen method, achieving high labeling efficiency (exceeding 90%). The 125I-MN-14, used for biodistribution experiments, had a specific activity of 41 kBq/μg, while the 131I-MN-14, prepared for radioimmunotherapy experiments with the same method, reached a specific activity of 960 kBq/μg. Liu et al. [63] successfully investigated the therapeutic efficacy of Iodo-gen-made ∗I-labeled anti-carcinoembryonic antigen mAb CL58 in a mouse model of human colon cancer.

Wang et al. [64] reported significant increase in radiolabeling yields of ∗I-labeled radiopharmaceuticals when very small reaction volumes (up to 25 μL) were used. They observed an interesting solvent effect when the polar aprotic solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as a precursor solvent in reactions carried out otherwise in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-buffered solutions (pH 7.4). RCYs of both water-soluble and water-insoluble small compounds increased to over 95% with the addition of DMSO. For example, when mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) was 125I-iodinated in the presence of a small amount of DMSO, the radioiodination yield increased from 49.5% (without DMSO) to 99.7% (with DMSO). However, when the antimucin mAb B72.3, known to target colon adenocarcinoma cells grown subcutaneously in mice, was used, the radiolabeling yields with and without DMSO were both over 99%.

Self-radioiodination of the oxidative reagent can be a concern when the large-scale production of an iodinated peptide is planned. Ünak et al. [65] observed 5%–10% of unidentified radioiodinated impurities when using Iodo-gen for labeling of small organic compounds. They concluded that approximately 10%–20% of the initial iodine radioactivity is consumed for the self-radioiodination of Iodo-gen itself when no other iodinatable substrate was added to the reaction mixture.

3.1.5. Pierce radioiodination tubes

Commercially available Pierce™ iodination tubes (Thermo Scientific) contain an oxidizing reagent, Iodo-gen, pre-coated on the glass surface, eliminating the need for a separate reagent surface-coating step (Table 3, entry 8) [66]. However, a limitation of these iodination tubes is that the concentration of the plated oxidizing reagent is relatively high, about 50 μg (115 nmol) of Iodo-gen per tube. The concentration is not suitable for reactions involving very low concentrations of the substrate to be labeled, such as 1–10 nmol of peptide and 37 MBq (1 mCi) of [125I]NaI (0.05 nmol). Using an excess of oxidizing reagent in such cases can result in a higher proportion of damaged peptides [41]. Janssens et al. [66] analyzed the iodination of five quorum sensing peptides. For the heptapeptide Q164 (SDLPFEH), two iodination methods were investigated. Using the Iodo-gen method, they achieved an iodination yield of about 20%, compared to only 2% with the Bolton–Hunter method.

3.1.6. Pierce radioiodination beads

Alternatively, Pierce™ iodination beads [67] (Thermo Scientific) are 3-mm diameter uniform polystyrene beads coated with an oxidizing reagent (immobilized chloramine-T derivative), providing efficient solid-phase activation of iodine for protein or peptide iodination procedures (Table 3, entry 9) [5]. These coated iodination beads offer a convenient and efficient method for iodine labeling without the damaging oxidative effects typically associated with chloramine-T and other solution-based methods. According to the manufacturer's instructions, one or two beads per milliliter of protein solution can be added, and after the labeling reaction, they can be easily removed, effectively eliminating the oxidizing agent from the protein [68]. However, the handling of this reaction setup can be somewhat inconvenient, especially for small-scale reactions (<10 nmol), as it may result in lower recovery of the labeled peptide. Robinson et al. [10] validated a method using 124I-labeled anti-HER2 diabody to investigate PET quantification of tumor uptake in small-animal model systems. This 124I-diabody C6.5 (52 kDa) was prepared using Iodo-gen-coated glass beads with labeling efficiencies up to 19%. In contrast, when conjugation with 124I-Bolton–Hunter reagent was carried out, only up to 8% RCY was achieved.

3.2. In vivo stability of radioiodinated peptides and proteins

The in vivo stability of radioiodinated pharmaceuticals used in nuclear imaging and radiotherapy is an important general concern. Loss of the label from radiopharmaceutical reduces the amount of activity that the compound can deliver to the target tissue and may lead to accumulation of free iodine in the thyroid. Iodotyrosine deiodinase has been identified as the enzyme that catalyzes the reductive deiodination of only small iodinated aromatic compounds, e.g., an ortho-iodophenol [69]. Geissler et al. [70] discovered that the over time decrease in radioactivity of 125I-labeled Tyr residues in the mAb DA4-4 was primarily caused by proteolytic catabolism in the internal lysosomes following internalization of the antibody-target complex. Enzymatic deiodination occurs only when the protein has already been disassembled into individual aa and the iodo-Tyr moieties are released as free aa units. Notably, a small iodo-Tyr pentapeptide-target complex does not undergo deiodination, which differs from the fate of the complex formed by the antibody DA4-4.

Bakker et al. [71], in the study on the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of radiolabeled 123I-Tyr3-octreotide, concluded that most of this octapeptide was excreted intact, and the residual non-specific radioactivity was mostly represented by the drug itself, which was undergoing standard clearance by the liver and the kidneys.

The rationale behind the design of the appropriate probe is that proteolytic decomposition of an antibody bound to its target cannot be prevented; therefore, at best, the radioiodinated label should be ideally retained within the lysosomes. The positively charged metabolites are retained much longer in lysosomes without being released into the cytoplasm, and the use of d-aa further prevents proteolysis. Foulon et al. [72] successfully designed a terminal pentapeptidic tag containing three positively charged d-aa (NH2-kr∗yrr-OH) labeled with 131I on the D-Tyr residue using Iodo-gen, and then conjugated it to the murine anti-EGFRvIII mAb L8A4 via maleimido functionality.

Cavina et al. [69] published a review summarizing successful rational improvements in the biostability of radioiodinated pharmaceuticals and provided general guidelines for designing stable radioiodinated compounds. They concluded that it is necessary to consider the whole molecule, rather than just the radioiodinated fragment. The main factor involved is the proteolytic cleavage of the radioiodine label from small iodinated compounds, while on-peptide deiodination was NOT observed. An analysis of radioiodination sites identified a general resistance of iodoarenes and arenes furnished with electron-donating groups (e.g., methoxy and methyl) towards in vivo deiodination; however, iodoanilines, iodophenols, and radioiodinated nitrogen-containing heterocycles were often not resistant to in vivo deiodination.

3.3. Indirect radioiodination via conjugation with 125I-labeled prosthetic groups

Iodination on tyrosine moieties is the most effective peptide labeling technique because it involves only a non-peptidic modification. However, if the presence or absence of iodine atom on the tyrosine residue is crucial to the function of the pharmacophore, an alternative labeling strategy is needed. In such cases, another iodinatable residue must be labeled instead, and the resulting isotopomers must be chromatographically separated, or an indirect labeling technique must be employed. The most common alternative approach has been to perform classical direct radioiodination of a small tyrosine-like molecule and then to attach this pre-labeled molecule to the free amino groups of lysine moieties in the protein. Radiohalogenation of small molecules for use as protein conjugates has different requirements for oxidizing reagents. Since these reactions are conducted in a separate vessel from the protein, stronger oxidizing reagents can be used without affecting the protein. While the overall radiolabeling efficiencies are lower with this approach, because it involves two consecutive separate labeling steps, the labeled product is not exposed to oxidative conditions at any point.

3.3.1. Bolton–Hunter radioiodination

The most widely used non-oxidative technique, which is milder to proteins than alternative direct labeling methods, involves the use of pre-labeled Bolton–Hunter conjugating reagent N-succinimidyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate (SHPP) (Scheme 4). This reagent contains one or two 125I atoms and conjugates with the N-terminal amino group of a peptide or the ε-amino group of lysine, forming a new stable amide bond (Scheme 4). The N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) active ester acylates primary amino groups in a buffered solution (pH 7–9) to form stable amide bonds with an iodinated p-hydroxyphenylpropionic residue [66]. Although this technique is gentle, it leads to greater derivatization of the peptide structure compared to oxidation methods. It is mainly used for labeling longer peptides or mAbs, which are large globular proteins capable of tolerating more substantial modifications. However, the main concern with this method is that the acylation site must not involve the pharmacophore, and optimizing the reaction is time-consuming [43]. Due to the low predictability of labeling results, it is not suitable for routine use.

Scheme 4.

Indirect radioiodination via conjugation with 125I-labeled Bolton–Hunter reagent. Radioiodination of Bolton–Hunter prosthetic reagent of high specific activity and its use for site-non-specific conjugation with a protein to be labeled. Reprinted from Ref. [66] with permission. SHPP: N-succinimidyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; mAb: monoclonal antibody.

Likewise other conjugating groups based on NHS esters, which are selective towards lysine ε-amino moieties within a protein chain, this method struggles with low site-specificity, potentially leading to batch-to-batch variability in labeling. This issue is particularly problematic for labeling large macromolecules, such as mAbs, which contain many lysine residues.

Janssens et al. [66] reported only very low yields (2%–6%) when using the Bolton–Hunter method for the iodination of quorum-sensing peptides. In contrast, Chaturvedi et al. [73] reported conjugation of prepared 124I-labeled Bolton–Hunter with JAA-F11 antibody achieving a good yield (30%). Importantly, the labeled mAb retained immunoreactivity similar to that of the non-labeled mAb. Unfortunately, this was not the case for 124I-labeled JAA-F11 prepared via direct oxidation with Iodo-gen beads. Because the direct Iodo-gen method labels tyrosine residues in the proteins, it could potentially alter the pharmacophore of JAA-F11 in the mAb. This example highlights the necessity of testing the immunoreactivity of labeled mAbs after radiolabeling and purification. Even though a gentle method with high labeling efficiency is used, when iodine is attached to the tyrosine or histidine residue near any of the receptor binding site, the final product is useless.

For macromolecules with many reactive sites, such as proteins or mAbs, where separation of regioisomers is not feasible, a non-specifically labeled product is always obtained. Therefore, radiochemists must have other alternative labeling methods available in their toolkit to label the protein of interest using different strategies. There is not a single radioiodination method that is universally the best, the easiest, or the most widely applicable.

Bolton–Hunter approach can be the method of choice when tyrosine residues, essential for protein function or immunogenicity, need to be preserved or in the case of modifying proteins lacking accessible tyrosine/histidine residues [3]. The reagent is commercially available from several sources; although it is rather expensive, it can be also prepared in-house via direct iodination of commercially available precursor (Scheme 4) [66]. The RCY can be significantly improved (up to 97%) with the addition of DMSO to the reaction mixture, compared to typical yields of 30%–75% [64].

SHPP is relatively insoluble in aqueous environments and must be dissolved in an organic solvent (such as dioxane or DMSO) before being added to a reaction medium. Fortunately, a water soluble version of the original Bolton–Hunter reagent is also commercially available: sulfosuccinimidyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate, sulfo-SHPP (Scheme 4). This compound contains a negatively charged sulfonate group on the NHS ring structure, providing enough hydrophilicity to allow direct addition to aqueous reaction media.

Russell et al. [74] compared the Bolton–Hunter reagents with the iodination carried out on non-specific tyrosine moieties and found that Bolton–Hunter reagent conjugates were more resistant to deiodination than the tyrosine-labeled products. Although they did not further investigate the factors affecting deiodination or the effect of the modification's position within the peptide, it is assumed that the lysine conjugates do not undergo proteolytic cleavage, thereby preventing the release of the radioiodinated Bolton–Hunter label [69]. However, the non-conjugated Bolton–Hunter reagents share many structural features with 4-iodotyrosine and are likely good substrates for deiodinases. Indeed, the 124I-Bolton–Hunter reagent tends to undergo in vivo enzymatic deiodination, and to achieve radiolabel stability, a variety of radioiodinated carboxylic acid esters have been developed for conjugation to proteins [75].

3.3.2. Prosthetic groups with the lack of phenolic aromatic groups

The use of tri-n-butyltin intermediates for site-specific radiohalogenation of small molecules has led to widespread use of arylstannanes as reagents of choice for synthesis of a variety of radioiodinated prosthetic reagents. One end of the molecule can be designed to enhance in vitro labeling efficiency, while the other end can be tailored for conjugation with specific protein functionalities.

Different linkers can be placed between the radiolabeled tag and the protein to study the effect of spacing on the in vivo stability of the entire radiolabeled conjugate (∗I-tag-linker-protein) to its metabolic degradation (“deiodination”) [50].

N-Succinimidyl-3-[124I]-iodobenzoate (3-[124I]-SIB) or N-succinimidyl-4-[124I]-iodobenzoate (4-[124I]-SIB) (Scheme 5A) were developed to exhibit higher stability with respect to in vivo deiodination, as they lack phenolic aromatic groups [76,77]. Zalutsky and co-workers [77] reported successful syntheses of ∗I–SIB conjugated to mAbs, which resulted in significantly reduced thyroid radioiodine uptake when using 125I-SIB conjugated with goat IgG antibody compared to the direct labeling with 131I [78].

Scheme 5.

Radiohalogenated prosthetic groups. (A) Classic amine chelating prosthetic groups without phenolic motif: N-succinimidyl-[∗I]-iodobenzoate ([∗I]SIB), charged N-succinimidyl-[∗I]iodo-3-pyridinecarboxylate ([∗I]SIPC), and N-succinimidyl-4-guanidinomethyl-3-[∗I]iodobenzoate ([∗I]SGMIB). (B) Reaction sequence for synthesis of [∗I]SIB and charged [∗I]SIPC prosthetic groups, conjugation to one of the lysine moieties within the labeled protein. (C) Plausible mechanism of N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) oxidation of radioiodide to reactive ∗ICl. Reprinted from Ref. [83] with permission. (D) Synthesis of charged prosthetic group SGMIB labeled with radiohalogens of iodine or astatine-211. THF: tetrahydrofuran; Boc-SGMTB: N-succinimidyl-4-[N1,N2-bis(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)guanidinomethyl]-3-(trimethylstannyl)benzoate; TBHP: tert-butyl hydroperoxide; TFA: trifluoroacetic acid; AcOH: acetic acid; [211At]SAGMB: N-succinimidyl-3-[211At]astatoguanidinomethylbenzoate.

Reist et al. [79] found that in athymic mice with HC2 20 d2 xenografts, tumor uptake and tumor to healthy tissue ratios for L8A4 labeled with SIB were significantly higher than those observed when this mAb was labeled using Iodo-gen.

Zalutsky and co-workers [[75], [79]] have been investigating an alternative strategy for higher retention of radioactivity in tumor cells after the internalization of labeled mAbs. The design is based on the hypothesis that exocytosis of labeled catabolites across cells and lysosomal membranes can be minimized if they are charged species. N-Succinimidyl 5-(tributylstannyl)-3-pyridinecarboxylate was synthesized via a three-step reaction from 5-bromonicotinic acid (Scheme 5B), used as a precursor for radioiodination with ∗ICl. The radioiodination was performed under mild conditions in acetic acid (AcOH)–CHCl3 in the presence of oxidizing agent (N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) or peracetic acid), resulting in N-succinimidyl-5-[131I]iodo-3-pyridinecarboxylate ([131I]SIPC) (Schemes 5A and B), obtained in a yield greater than 80% [80]. Yang et al. [81] used 131I-SIPC for conjugation with insulin, which demonstrated higher in vivo stability than insulin directly radioiodinated via chloramine-T method. Non-specifically labeled insulin was used in both cases, and the specific activity of the prepared insulins was not reported.

NCS has been an attractive reagent for radiohalogenations of various N-succinimidyl organometallic intermediates because it is a weaker oxidant than tert-butyl hypochlorite, N-chlorotetrafluorosuccinimide, or dichloramine-T [82]. NCS does not halogenate phenolic compounds, thereby preventing dilution of the specific activity of most radiohalogen-labeled compounds by producing chloro-derivatives [28]. A drawback of using of NCS is that only small quantities (<10%) of water can be present without adversely affecting the oxidation process [28]. The mechanism of Na∗I oxidation with NCS is depicted in Scheme 5C. NCS is activated by protonation with glacial AcOH, and the iodide ion attacks the electrophilic chlorine atom of the intermediate, oxidizing the iodide and generating ∗ICl. The organometallic compound then reacts with the electrophilic iodine via ipso-SEAr (electrophilic aromatic substitution) to generate the desired iodoarenes (Scheme 5C) [83].

Another permanently charged reagent, N-succinimidyl-4-guanidinomethyl-3-[∗I]iodobenzoate ([∗I]SGMIB) (Scheme 5A), was designed by attaching a guanidinomethyl function to SIB. The key tin precursor, N-succinimidyl-4-[N1,N2-bis(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)guanidinomethyl]-3-(trimethylstannyl)benzoate (Boc-SGMTB) (Scheme 5D), was synthesized from 3-iodo-4-methylbenzoic acid in multiple steps [84]. An SGMIB analog labeled with an α-particle emitting heavy halogen, 211At (t1/2 = 7.2 h), N-succinimidyl-3-[211At]astatoguanidinomethylbenzoate ([211At]SAGMB) (Scheme 5D), can be synthesized from the tin precursor (Boc-SGMTB) using tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) in chloroform/acetic acid solution to oxidize radioiodide and astatide [85].

Compared to the other radiolabeling methods, significantly higher delivery and retention of radioactivity (two- to fourfold increase) in tumors were achieved (both in vitro and in vivo) when internalizing mAb anti-EGFRvIII L8A4 was radiolabeled with [∗I]SGMIB or [211At]SAGMB [84,85].

An imidate ester of phenol, known as the Wood's reagent (Scheme 6A) [86], can be used as a more stable alternative to NHS-active esters. It also conjugates amine groups, with the added advantage of retaining a positive charge on the formed amidine functionality at physiologic pH (Scheme 6B). The method was demonstrated on the labeling of hexadecapeptide gastrin G [87] and cell surface proteins [88]. Unlike the formation of amide bonds, the positive charge initially carried by the lysine amine is retained. Radiohalogenated isothiocyanates also react with protein amine to form stable thiourea bonds (Schemes 6A and C). 3-∗Iodophenyl isothiocyanate (Scheme 6A) has been used for the mAb radioiodination of D612, 17-1A, and Lym-1 [89,90]. Tolmachev and co-workers [91] reported a strategy involving radioiodinated prosthetic groups based on boron derivatives, such as 125I-(4-isothiocyanatobenzylammonio)-decahydro-closo-dodecaborate (∗I-DABI) (Scheme 6A). Negatively-charged polyhedral boron clusters can be easily halogenated forming highly stable boron-halogen bonds [92], making them promising for radionuclide diagnostics and cancer therapy. The ∗I-DABI can be effectively conjugated with macromolecules, as demonstrated by its conjugation with mAb Trastuzumab (RCY 55%–60%). The radioiodine label of 125I-dodecaborate cage conjugated to mAb was shown to be extremely stable in hydrophobic and high ionic strength solutions, and also under physiological conditions [91].

Scheme 6.

Indirect radiohalogenation of peptide chain via conjugation with radiohalogenated prosthetic groups. (A) Examples of ∗I-labeled prosthetic groups for conjugation with macromolecules. Radioiodination strategies using imidate ester (B), isothiocyanate (C), and maleimide (D) functionality.

The second commonly utilized functional group for protein conjugation is the sulfhydryl (thiol) group present on cysteine residues (Scheme 6D). Thiols can be reacted selectively over amines on a protein because they are better nucleophiles, particularly if the amines are protonated by pH adjustment to 7 or less [28]. N-(3-[125I]iodophenyl)maleimide (∗I-IPM) (Scheme 6A) has been used to label rabbit IgG and bovine serum albumin (BSA) [93]. Other maleimides have also been prepared and investigated, such as N-(4-[125I]iodophenyl)maleimide [94], and N-[2-(3-125I-iodobenzoyl)aminoethyl]maleimide (∗I-IBM) (Scheme 6A), which was conjugated with F3Cys peptide for tumor imaging with PET or SPECT techniques [95]. Another example is 3-maleimido-N-(4-[18F]fluorobenzyl)benzamide, which labeled rabbit IgG in 50% yield [94]. Wilbur et al. [96] evaluated five 211At- and 125I-labeled closo-decaborate2– anion probes containing hydrazone and poly(ethylene glycol) linkers, conjugated via sulfhydryl-reactive maleimide groups to mAb fragments (FABs). This labeling might be particularly beneficial for radioiodinated proteins or peptides that are localized to the kidneys.

3.3.3. Oxidative conjugation

An alternative approach for the 125I-radioiodination of peptides lacking a tyrosine moiety has recently been reported by Mushtag. This novel 125I-labeling strategy for biologically active molecules (proteins and peptides) involves an iodinated building block of an alkyl aldehyde and a site-specific aryldiamine-modified biomolecule in a high-yield (67%–99%) condensation reaction (Scheme S1) [97]. Radioiodinated human serum albumin (125I-HSA) prepared in this manner exhibited excellent in vivo stability. The method is reported to be site-specific, which might be the case for smaller peptides. However, achieving the site-specific conjugation of diaminaryl-maleimide linker with one of the cysteine moieties in larger proteins like HSA seems more challenging. Additionally, potential contamination of the labeled protein with trace amounts of copper, used in the final step of the process, may limit its broader application.

4. Optimal peptide radioiodination technique

To determine the optimal 125I-radiolabeling strategy for routine and frequent laboratory use, the commonly used methods listed in Table 3 need to be carefully considered. Key aspects such as labeling reliability, cost, simplicity of the reaction setup, universality of the labeling protocol, personal safety, RCY, recovery of labeled material, ease of use, extent of peptide modification, and stability of the label, were compared and evaluated. Herein, we review our long-term experience with a labeling technique using the convenient Pierce™ Iodination Reagent (Iodo-gen), which has become our first-choice strategy for the 125I-radioiodination of oligopeptides, (poly)peptides, and proteins (Table 4, Table 5). This method provides better outcomes than other techniques, offering high specific activity, reproducibility, applicability to a wide range of materials, and efficient recovery of iodinated peptides. The iodination process is straightforward and can be performed without specialized equipment, making it cost-effective as well. We demonstrate a practical application of this labeling technique to various peptides, including detailed conditions for labeling and chromatographic analyses, and share a number of tips and tricks to expedite the development of synthetic protocols.

Table 4.

Reaction conditions for 125I-radioiodination of peptides using Iodo-gen method.

| Entry | Peptide | Labeled position a | Time (min) | Na[125I] (MBq/mCi) |

Peptide/NaI (equivalents) | Typical RCY (%) b,c,d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBq) | mCi | ||||||

| 1 | [Sar1, Ile8]-angiotensin II | Tyr4 | 15 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 40 | 36 |

| 2 | 74 | 2 | 70 | 49 | |||

| 3 | 74 | 2 | 80 | 66 | |||

| 4 | DAMGO | Tyr1 | 15 | 15 | 0.4 | 100 | 57 |

| 5 | 1DMe-Y8Fa | d-Tyr1 | 15 | 74 | 2 | 20 | 37–49 |

| 6 | 15 | 74 | 2 | 40 | 60 | ||

| 7 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 70 | 76 | ||

| 8 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 90 | 49–75 | ||

| 9 | 20 | 37 | 1 | 60 | 52–53 | ||

| 10 | EYF | Tyr2 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 60 | 28–35 |

| 11 | 74 | 2 | 30 | 24 | |||

| 12 | [D-Pro10]-Dynorphin A | Tyr1 | 15 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 40 | 18 |

| 13 | PrRP-31 (rat) | Tyr20 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 15 | 45 |

| 14 | 74 | 2 | 39–53 | ||||

| 15 | 111 | 3 | 43–49 | ||||

| 16 | PrRP-31 (human) | Tyr20 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 22 | 17–25 |

| 17 | 74 | 2 | 20 | 36 | |||

| 18 | 74 | 2 | 30–40 | 24–30 | |||

| 19 | 111 | 3 | 25–37 | 16–18 | |||

| 20 | 148 | 4 | 11 | 27 | |||

| 21 | palm11-PrRP-31 (human) | Tyr20 | 30 | 37–111 | 1–3 | 25–30 | 4–9 |

| 22 | 55 | 1.5 | 100 | 28 | |||

| 23 | 18–37 | 0.5–1 | 150 | 17–19 | |||

| 24 | CART(61–102) | Tyr62 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 18 | 51–66 |

| 25 | 74 | 2 | 18 | 47–62 | |||

| 26 | 111 | 3 | 18 | 70 | |||

| 27 | CART(55–102) | Tyr62 | 15 | 59 | 1.6 | 35 | 19 |

| 28 | 33 | 0.9 | 18 | 10 | |||

| 29 | palmCART(61–102) | Tyr62 | 25 | 26 | 0.7 | 21–26 | 11–17 |

| 30 | octCART(61–102) | Tyr62 | 25 | 37 | 1 | 20 | 22 |

| 31 | PYY | Tyr20, Tyr21, Tyr27 | 15 | 33 | 0.9 | 25 | 6 |

| 32 | 15 | 55 | 1.5 | 30 | 9 | ||

| 33 | 15 | 74 | 2 | 25 | 14–21 | ||

| 34 | Ghrelin (rat) | His9 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 18 | 9–15 |

| 35 | 37 | 1 | 24 | 14–31 e | |||

| 36 | 74 | 2 | 18 | 23–37 | |||

| 37 | 148 | 4 | 18 | 50 | |||

| 38 | [Dpr(N-oct)3]ghrelin | His9 | 15 | 74 | 2 | 18 | 17–25 |

| 39 | 148 | 4 | 18 | 35 | |||

| 40 | [Sar1, Dpr(N-dec)3]ghrelin | His9 | 20 | 33 | 0.9 | 20 | 5–10 |

DAMGO: D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin; 1DMe-Y8Fa: yLF(Me)QPQRF-NH2; EYF: EYWSLAAPQRF-NH2; PrRP: prolactin-releasing peptide; CART: cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide; PYY: peptide YY.

Elucidated by mass spectrometry analysis of analogous 127I-iodinated fractions, performed using UltrafleXtreme™ matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization with time-of-flight analyzer (MALDI-TOF/TOF) (Bruker Daltonics).

Reaction performed as described in Section S.1.4 of Supplementary data.

Reaction repeated >5 times; an average radiochemical yield (RCY)/whole extent is shown.

Reaction vial not rinsed, if not stated otherwise.

Rinsing of reaction vial after iodination accomplished with pure water or 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)–bovine serum albumin (BSA) (2 × 100 μL).

Table 5.

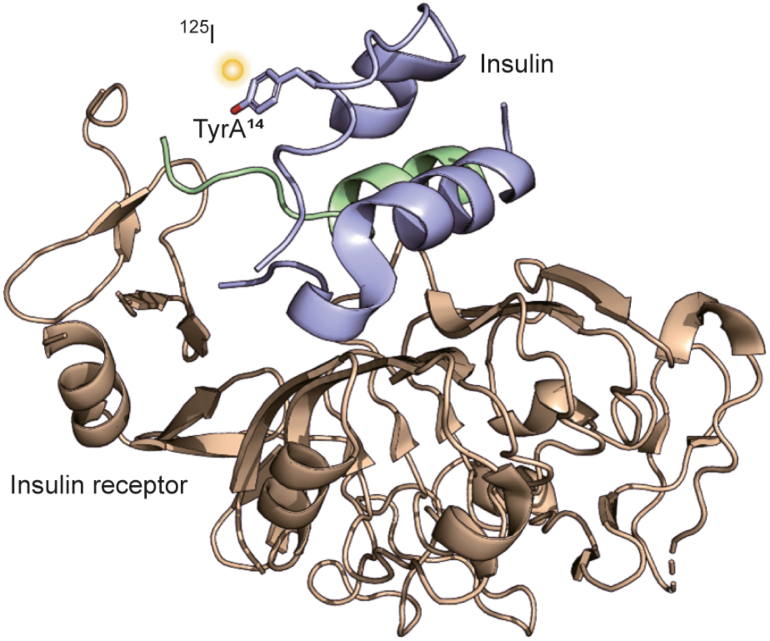

Conditions for the 125I-radioiodination of polypeptides and proteins belonging to the insulin family.

| Entry | Material | Labeled positiona | Time (min) |

Na[125I] (MBq/mCi) |

Peptide/NaI (equivalents) |

Typical RCYb,c,d (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBq | mCi | ||||||

| 1 | Insulin (human) | TyrA14 | 15 | 37 | 1 | 40 | 21–35 |

| 2 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 110 | 18–34 | |||

| 3 | [D-HisB24, GlyB31, TyrB32]-insulin | TyrB32 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 40 | 15 | |

| 4 | IGF-1 (human) | Tyr24, Tyr31, and Tyr60 (1:2:2) | 12 | 37 | 1 | 1.07 | 11–25e |

| 5 | 12 | 37 | 1 | 1.07 | 4–7 | ||

| 6 | 12 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 1.07 | 10e | ||

| 7 | 10 | 37 | 1 | 1.3–1.6 | 6–7 | ||

| 8 | 10 | 37 | 1 | 1.8 | 11 | ||

| 9 | 10 | 37 | 1 | 0.8 | 8 | ||

| 10 | IGF-2 (human) | Tyr2 | 5 | 74 | 2 | 0.8 | 6 |

| 11 | 5 | 74 | 2 | 1.7 | 6–9 | ||

| 12 | 8 | 74 | 2 | 0.8 | 12 | ||

| 13 | 5 | 74 | 2 | 3 | 18 | ||

| 14 | IGF-BP-3 | Not specified | 11 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 9 |

| 15 | ALS | Not specified | 16 | 5.5 | 0.15 | 1.0 | 7 |

IGF: insulin-like growth factor; IGF-BP: IGF-binding protein; ALS: acid-labile subunit.

Position of modification, elucidated by mass spectrometry analysis of analogous 127I-iodinated fractions performed using an UltrafleXtreme™ matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization with time-of-flight analyzer (MALDI–TOF/TOF) (Bruker Daltonics).

Reaction performed as described in S.1.4 of Supplementary data.

Reaction repeated >5 times; average radiochemical yield (RCY) or the range of RCY values are shown.

Reaction vial not rinsed, unless stated otherwise.

Reaction rinsed with the addition of H2O (50–100 μL) prior to purification.

4.1. Reaction vessel coating

To control the course of the small-scale radioiodination reaction, it is convenient and desirable to conduct the reaction in self-made reaction vessels pre-coated with a small amount of Iodo-gen [49]. The reaction vessels (commercial 1.5-mL Protein LoBind® vials) are pre-coated by simply adding appropriate aliquots of a dichloromethane solution [37] of the Pierce™ Iodination Reagent (3, 5, 10, or 23 nmol) followed by convenient solvent evaporation using a refrigerated centrifugal vacuum concentrator. Typically prepared in larger batches, such as 100 vials at a time, these pre-coated reaction vials can be readily stored desiccated in a freezer (−20 °C) for over 36 months without any loss in reactivity.

4.2. Direct radioiodination approach

To simplify the reaction setup and enhance personal safety, minimizing the handling of radioactive material is always preferred (see Section S.1.1 of Supplementary data). A direct one-pot approach to iodination is more reasonable than the standard two-step Chizzonite indirect method, which involves pre-activation of the radioactive iodide in a pre-coated iodination tube [98] and transferring the active species to a separate reaction vessel, avoiding any potential contact of the iodinated material with the oxidative reagent. Using the direct iodination technique eliminates potential risks associated with the handling and transfer of the activated iodine form (125I+) and improves both the isolated yield of the labeled material and operator's safety.

4.3. Peptide recovery enhancement

The irreversible binding of most peptides, particularly those modified by fatty acids at the N-terminus, to the walls of polypropylene tubes can be a challenge. This issue was minimized by using Eppendorf LoBind® tubes. Additionally, if the walls of the test tubes in the collector are pre-saturated with a non-interfering peptide (e.g., BSA) prior to collection of the purified labeled peptide, irreversible binding is further reduced [99,100].

4.4. Trace labeling strategy

To suppress the generation of the unnecessary di-iodotyrosyl derivative of the 125I-labeled peptide, it is recommended that the molar excess of the native peptide over the source of radioactive iodine [125I]NaI to be greater than 10:1 (Table 4) [40,49]. The formation of di-iodotyrosyl cannot be completely avoided due to the stoichiometry [43]. For small and easily available oligopeptides, such as angiotensin II [101] or 1DMe [102], the best RCY was achieved with a molar ratio of 80 (Table 4, entry 3). For low-recovery, lipophilic N-terminus fatty-acid-modified peptides, increasing the peptide-to-radioiodine ratio to 100 ensures that a sufficient amount of labeled material can be isolated [103,104].

4.5. Factor of pH

The exact nature of reaction buffer depends on the properties of the protein to be radioiodinated. For optimal peptide solubility and tyrosine reactivity towards SEAr, the pH is often adjusted to 7.4 [36,37,49] in 0.1 M PBS [43,100]. Lower yields of iodinated protein are typically obtained at pH values below 6.5 and above 8.5 [41]. However, at pH 8.2–8.5 the iodination of histidine residues tends to be favored [3,43,50]. To improve access to iodinatable moieties within the peptide's three-dimensional (3D)-structure, 0.15 M NaCl is added to the reaction solution.

4.6. Reaction time

The optimal reaction time must be determined for each specific peptide, as it depends on the accessibility of the moiety being labeled and the reactivity of the aa (Table 4, Table 5). In general, tyrosine iodination proceeds much faster than histidine iodination, with the latter being approximately 30–80 times slower [44]. For histidyl moiety iodination, the incubation period can be prolonged to 45 min [105]. If the tyrosine residue is located in an accessible N-terminus region or more iodinatable moieties are available, the substitution can proceed rapidly. Over-iodination of the peptide can quickly become an issue, sometimes even after just a few min of reaction time [36,37,43,68].

After iodination, the remaining non-reacted 125I+ iodonium species are scavenged through the addition of excess of quickly iodinatable material, such as BSA, to the iodination reaction. The resulting 125I-BSA is easily separable by HPLC.

4.7. Isolation of a high-specific-activity peptide

To obtain a tracer of sufficiently high specific activity, about 78 TBq/mmol (2,100 Ci/mmol), the desired 125I-radiolabeled peptide must be separated from the non-labeled (unreacted) starting material [40,49,106]. To isolate a product of high radiochemical purity, the radiolabeled protein must be separated from reaction contaminants, aggregates, free iodide, damaged peptides, and salts. This is often accomplished by simple desalting with size-exclusion or gel filtration [43]. However, the size exclusion technique, which is commonly used for isolating iodinated peptides in pharmacokinetic studies, cannot effectively separate the unlabeled starting material, mono-labeled isotopomers, over-iodinated derivatives, and damaged proteins [41]. Mono-iodinated peptides are expected to behave (bio)chemically—considering size, secondary structure, and hydrophobicity—more similarly to non-labeled intact peptides than multi-labeled derivatives [107]. The addition of iodine can affect the reactivity of a smaller molecule more than that of a larger macromolecule. To isolate a pure regio-specifically mono-iodinated peptide of interest, chromatographic conditions using radio-HPLC instrumentation must be carefully developed [49].

4.7.1. HPLC conditions for isolation of specifically labeled peptide

HPLC offers rapid and easy operation while providing optimal separation of modified and unlabeled peptides [36,75,106,108]. Examples of chromatographic conditions, including column specifications and gradients, used for purifying of specific peptide are detailed in the Section S.1.2 of Supplementary data. The hydrophobicity of a peptide is increased upon incorporation of halogen atom. Generally, the earlier eluting peak on a reverse-phase system observed in the UV chromatogram represents the unlabeled (parent) material [109]. The later eluting minor peak of radioactivity typically represents the more hydrophobic di-iodotyrosyl derivative. Non-radioactive sodium [127I]-iodide can be used to optimize labeling conditions, study the reaction course, develop an efficient HPLC separation method, and specify the position of the modification through advanced mass spectrometry methods (MS/MS experiments, chymotrypsin peptide sequencing, Section S.1.3 of Supplementary data) [107,110]. Any isolated and fully characterized 127I-peptide analog should always be tested to confirm that its biological activity is preserved compared with its unlabeled counterpart.

4.7.2. Formulation and storage

Separated fractions of pure 125I-labeled material were collected into plastic tubes pre-saturated with 200 μL of a cocktail containing 1 mg/mL BSA and 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) at pH 7.3. Aliquots of labeled peptide were pipetted into low-bind Eppendorf tubes and lyophilized in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator, resulting in dry peptide dispersed in a BSA matrix. According to the literature [16,37,40], the lyophilized 125I-peptides can be stored at −20 °C and retain their receptor-binding properties for up to three months. No unbound iodide or radioactive debris were observed when radio-analytical radio-HPLC was performed after five months of storage [111].

4.7.3. Intramolecular effects of 125I decay

The intramolecular effects of 125I decay within o-iodotyrosine was studied by Berridge et al. [46] and Jiang et al. [112]. They prepared 125I-tyrosine with specific activity of 19.3 TBq/mmol (522 Ci/mmol), formulated in a buffer/ethanol solution. After a long-term study of the stored sample (up to 800 days), they described a coulombic explosion mechanism of disintegration. The electron-capture decay and resulting Auger cascades lead to a multiple charged tellurium atom (Scheme 7) [113]. The distribution of charges throughout the molecule occurs before its disruption. The energy released from the coulombic repulsions between the delocalized charges, as well as the energy from the subsequent charge neutralizations, is more than sufficient to overcome bond energies, leading to the disruption of the aromatic ring in a coulombic explosion. All products resulting from 125I decay were identified as small polar molecules.

Scheme 7.

Intramolecular effects of 125I decay on long-term radiochemical purity of formulated 125I-labeled peptides. Intramolecular effects of 125I decay within o-iodotyrosine residue. The decay of the radioisotope 125I into 125Te begins with an electron capture (EC) decay, followed by the emission of two groups of approximately 10 electrons, each via Auger processes [113]. Reprinted from Ref. [113] with permission. The resulting highly positively charged 125Te distributes its charge throughout the molecule, causing a coulombic explosion that leads to the destruction of the aromatic ring and formation of many polar fragments. No radioactive remnants are produced when a molecule is singly iodinated.

Damage to other labeled molecules from internal radiation is not a significant concern in the diluted solutions in which 125I-labeled tracers are usually stored. Furthermore, this damage can be virtually eliminated by adding free radical scavengers, such as ethanol, thiourea, ascorbate, tert-butanol, benzoic acid, mannitol, ethylene glycol, HEPES, or tris(hydroxymethyl)aminoethane (Tris) [[114], [115], [116], [117]]. The biophysical aspects of Auger processes have been reviewed elsewhere [118,119]. The absence of a “decay catastrophe” [120]—a situation where iodine decay disrupts a molecule containing another, yet undecayed, radioiodine atom—has crucial implications for the successful use of radioligands in receptor binding experiments, as a constant specific activity is assumed [111,121,122]. This type of damage can occur only with tracers containing at least two atoms of radioiodine, resulting in shorter shelf-life of the labeled material [111].

Doran et al. reported a rare example where the coulombic explosion mechanism of the carrier peptide disintegration does not apply to two singly radioiodinated peptides (cholecystokinin octapeptide and GLP-2) conjugated with 125I-Bolton–Hunter tag, with a specific activity of 80.7 TBq/mmol (2,180 Ci/mmol) [121]. Thus, the apparent absence of the decay catastrophe leads to an exponential decrease in specific activity over time. The authors speculated that spatial separation of the 125I-SHPP tag from the carrier peptide itself prevented its radiation-induced backbone fragmentation, allowing the bioactivity of each ligand to be largely conserved despite the radioactive decay of the iodine label.

5. Radioiodination of neuropeptides––universality of Iodo-gen technique

The labeling of peptides with radionuclides offers unrivaled detection sensitivity in biological assays, localization, and imaging studies. Over the past 80 years, two iodine radionuclides, 125I and 131I, have been particularly popular for the in vitro studies of purified proteins and peptides. The preference for protein radioiodination over labeling with β-emitting radionuclides (e.g., 35S, 14C, and 3H) stems from several advantages. First, labeling with γ-emitters allows to reach high specific activities and offers the ease of late-stage labeling, the cost-effective readily available radionuclide sources, and the straightforward high-throughput measurement of large numbers of γ-emitting samples (hundreds per hour) using a gamma-counter. Additionally, the handling of radioiodination is simpler in comparison with methods like hydrogenation reactions. Since its inception in 1945 [123], radioiodination has remained central to a wide range of fundamental in vitro analytical biochemistry techniques, such as structure-activity studies and evaluation of the binding sites of peptide analogs to their receptors.

5.1. Short peptides

Using the general labeling strategy (Section S.1.4 of Supplementary data), a very high RCY of up to 76% can be achieved within just 15 min of reaction time when working with short peptides (about 8 aa in length). To achieve such high yields, the peptide has to have easily accessible tyrosine residues and the peptide to [125I]-NaI molar ratio should be 70–80. The 125I-radioiodination of [Sar1, Ile8]-angiotensin II [124], an endogenous agonist of angiotensin II receptors that mediates vasoconstriction, proceeds rapidly. An optimal balance between mono-iodinated and di-iodinated derivatives was observed after 15 min of reaction, with an RCY of up to 66% when a higher molar ratio (80 equivalents) of peptide to [125I]-NaI was used (Table 4, entry 3) [101]. The shortest peptide included in Table 4 is DAMGO ((Y, D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol)-enkephalin, entry 4), a μ-opioid receptor-selective ligand. Even at a low radioactivity amount of 14.8 MBq (0.4 mCi), the reaction yielded a high RCY of 57%.

5.2. Anorexigenic neuropeptides as anti-obesity and neuroprotective agents

The incidence of obesity has risen to epidemic proportions in recent years. Obesity is a major risk factor for developing serious conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. Peptides that regulate food intake, both anorexigenic (which decrease food intake) and orexigenic (which increase food intake), play a central role in the regulation of energy metabolism. Anorexigenic peptides, such as prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP), cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide (CART), neuropeptide FF (NPFF), and peptide YY (PYY), are promising candidates for the treatment of obesity and its related complications. Conversely, orexigenic peptides, such as ghrelin and opioids, are being considered for the treatment of cachexia, while their antagonists are explored for obesity treatment [125].

The conditions for labeling anorexigenic neuropeptides and their analogs belonging to the RF-amide family of peptides, which share an identical C-terminal aa sequence (RF-NH2), were extensively investigated. For exact peptide sequences and iodinated positions, see Table S1. Peptides 1DMe-Y8Fa [42,126], EYF and PrRP-31 [42,126] (the longest peptide in this group, an endogenous neuropeptide containing 31 aa, involved in regulating food intake [42]) yielded high RCY for a specific 125I-mono-tracer at D-Tyr1, Tyr2 and Tyr20, respectively (Table 4, entries 5–11, and 13–20). For optimal labeling, PrRP-31(rat) required 15 equivalents of the starting peptide and 37–111 MBq (1–3 mCi) of [125I]NaI to achieve a high RCY (39%–53%, Table 4, entries 13–15) [127]. Similarly, PrRP-31(human) was efficiently labeled with 20 equivalents of the starting peptide and 74 MBq (2 mCi) of [125I]NaI (Table 4, entry 17). Due to stoichiometric considerations, it is recommended to use a significant excess (>10 equivalents) of the starting peptide over the radioiodine reagent to suppress the formation of over-iodinated derivatives (Table 4, entry 18). Satoh et al. reported that using low equivalents of PrRP (rat or human) to [125I]NaI (6:1) provided a 125I-PrRP product with lower specific activity of 50 TBq/mmol (1,350 Ci/mmol), although the RCY was not reported [31].

5.2.1. Lipidized peptides

Recent epidemiological studies have identified obesity as a risk factor for the development of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other forms of dementia. Therefore, the potential neuroprotective effects of peptides that regulate food intake are being explored for therapeutic purposes. For these peptides to be effective in therapy, they need to be modified to increase their stability and ability to act centrally after peripheral administration. One successful strategy is the lipidization of peptides at regions of the molecule that do not affect their biological activity.

Lipidized PrRP-31 analogs have shown great potential in treating obesity and neurodegenerative diseases [102]. Lipidization of PrRP-31 not only stabilizes the peptide but also enhances its central effect after peripheral administration and increases its affinity for its receptor [126]. Human palm11-PrRP-31, modified with a lipophilic fatty acid chain, provided similar selectivity of iodination (Tyr20 vs His4/His6) as unmodified PrRP-31. However, a significant drop in isolated yield was observed due to the high lipophilicity of the peptide, which causes adhesion to surfaces during work-up processes, resulting in low recovery of the lipidized peptide [126]. When the labeling conditions used for unmodified PrRP-31 were applied to palm11-PrRP-31, a sharp decrease in RCY (to below 10%) was observed (Table 4, entry 21). To mitigate the adhesive nature of the lipophilic peptide, using a large excess of it over [125I]NaI (up to 100 equivalents) significantly increased the RCY to 28% (Table 4, entry 22).

5.2.2. Disulfide crosslinking

The general labeling strategy (Section S.1.4 of Supplementary data) can be efficiently applied to labeling of the CART series of peptides, which are involved in regulating food intake, stress, and other physiological functions [103]. The CART(61–102) peptide contains 42 aa, three disulfide bonds, and importantly, an accessible tyrosine residue (Tyr62) [7W2Z cryo-EM structure] (Fig. 1) [104]. Lin et al. [128] reported synthesis of mono-iodinated-Tyr62 CART(61–102) with a high specific activity of 81 TBq/mmol (2,200 Ci/mmol). Radioiodination of CART(61–102) yielded an exceptionally high RCY (up to 70%), even with a low consumption of the costly starting material (18 equivalents; Table 4, entries 24–26) [16,129]. The CART(61–102) molecule also contains methionine (Met7), a sulfur-containing aa susceptible to oxidation to methionine sulfoxide and further to methionine sulfone. As a result, four major peaks were observed in HPLC chromatograms, corresponding to the mono- and di-iodinated peptide combined, additionally each combined together with their oxidized Met7 isoforms [16].

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional (3D) structures of two peptides selectively radioiodinated by I-125 out of the receptor-peptide binding site. (A) Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide (CART)(61–102) (in violet; disulfide bonds between Cys⁶⁸ and Cys⁸⁶/Cys⁷⁴ and Cys⁹⁴/Cys⁸⁸ and Cys1⁰1 are shown in yellow). Residual amino acids (aa) are shown. The yellow sphere on TyrA62 depicts labeling with 125I. Created based on the 1hy9 NMR structure. (B) Interaction of ghrelin (in red) with ghrelin receptor. The yellow sphere on His9 depicts labeling with 125I. Created based on the 7W2Z cryo-EM structure. Reprinted from Refs. [104,126,133] with permission.

CART(55–102) contains two tyrosine residues (Tyr62 and Tyr66); however, only Tyr62 was selectively labeled, with no substitution observed at Tyr66 (Table 4, entries 27 and 28) [16]. The isolated fraction contained a small amount of 125I-Tyr62-mono-iodinated CART(55–102) oxidized at either Cys39 or Cys48 (7% RCY). Stanley et al. reported the 125I-labeling of CART(55–102) using the direct Iodo-gen method. However, after reverse-phase HPLC purification, the resulting radiolabeled probe exhibited a lower specific activity of 41 TBq/mmol (1,100 Ci/mmol), and the RCY was not disclosed [130].

Notably, lipidized (palm-, or oct-)CART(61–102) peptides were successfully 125I-labeled at Tyr62 with satisfactory yields (up to 22% RCY) while using only a limited amount of these valuable and difficult-to-synthesize peptides (Table 4, entries 29 and 30) [131]. In comparison to the high consumption required for palm11-PrRP-31 (100 equivalents), a lower amount of lipidized-CART(61–102) (20–26 equivalents) was sufficient to achieve a good RCY.

5.2.3. More iodinatable sites

Peptides possessing multiple tyrosine residues available for substitution via SEAr generally present a greater analytical challenge when iodinated derivatives need to be separated from each other [132]. Pancreatic PYY is a hormone secreted from endocrine L-cells in the small intestine. It is released after eating, circulates in the blood, and works by binding to receptors in the brain, where it decreases appetite and induces a feeling of fullness. PYY consists of 36 aa and contains 5 tyrosine residues (Tyr1, Tyr20, Tyr21, Tyr27, and Tyr36), each of which was iodinated to a roughly similar extent. The iodinated products were then separated and isolated using a standard C18 column (Section S.1.2 of Supplementary data). Three fractions of 125I-labeled PYY—radioiodinated at Tyr1, Tyr36, and Tyr20/Tyr21/Tyr27, respectively—were successfully separated and isolated (Table 4, entries 31–33) [126].

5.2.4. Histidine radioiodination