Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a bacterial pathogen that elicits a strong cellular immune response and thus has potential use as a vaccine vector. An attenuated strain, L. monocytogenes dal dat, produced by deletion of two genes (dal and dat) used for d-alanine synthesis, induces cytotoxic T lymphocytes and protective immunity in mice following infection in the presence of d-alanine. In order to obviate the dependence of L. monocytogenes dal dat on supplemental d-alanine yet retain its attenuation and immunogenicity, we explored mechanisms to allow transient endogenous synthesis of the amino acid. Here, we report on a derivative strain, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, that expresses a dal gene and synthesizes d-alanine under highly selective conditions. We constructed the suicide plasmid pRRR carrying a dal gene surrounded by two res1 sites and a resolvase gene, tnpR, which acts at the res1 sites. The resolvase gene is regulated by a promoter activated upon exposure to host cell cytosol. L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR was thus able to grow in liquid culture and to infect host cells without d-alanine supplementation. However, after infection of these cells, resolvase-mediated excision of the dal gene resulted in strong down-regulation of racemase expression. As a result, this system allowed only transient growth of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR in infected cells and survival in animals for only 2 to 3 days. Nevertheless, mice immunized with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR generated listeriolysin O-specific effector and memory CD8+ T cells and were protected against lethal challenge by wild-type Listeria. This vector may be an attractive vaccine candidate for the induction of protective cellular immune responses.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive, facultative intracellular, food-borne bacterium that elicits strong cell-mediated immunity (16, 23). It has shown promise as a live vaccine vector against model cancers (6, 20, 34, 36, 38), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (31), influenza virus (22), and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (19, 48) and has been suggested for use as an AIDS vaccine vector (17, 28). However, L. monocytogenes is itself a pathogen that can cause fatal infections, particularly in immune-compromised or pregnant individuals (14, 21, 59). Therefore, the safety of L. monocytogenes as a vaccine vector is a critical issue that could block the potential utility of this organism.

An ideal vaccine strain of any living organism must be highly attenuated but fully immunogenic. To achieve this, various mutations in virulence-associated determinants of L. monocytogenes have been exploited for potential use as vaccine vectors (1, 2, 6, 8, 19, 24, 29, 30, 55, 57), but many tend to have the limitation of either weak immunogenicity or insufficient avirulence. We developed a highly attenuated strain, L. monocytogenes dal dat, by inactivating two genes (dal and dat) essential for d-alanine biosynthesis (58). This strain requires the unusual amino acid d-alanine, not synthesized by vertebrates, for viability and infection. It showed no reversion or significant suppression of its auxotrophy under laboratory conditions (unpublished observations). In the transient presence of d-alanine, L. monocytogenes dal dat demonstrated an ability to induce cytotoxic T lymphocytes and protective immunity against lethal challenge by wild-type L. monocytogenes. L. monocytogenes dal dat has been explored as a vaccine carrier for the development of a live human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine (18, 28, 41-43).

Since L. monocytogenes dal dat is disabled as a result of its requirement for d-alanine, its immunogenicity in mice is achieved by the transient supply of d-alanine along with the vaccine. Consequently, comparable infection of monkeys or humans would require parenteral administration of significant quantities of d-alanine. While this compound appears to be safe in the small rodent and in rhesus macaques, its safety in humans is unknown. These considerations prompted us to devise ways to circumvent the need for exogenous d-alanine while retaining the high level of attenuation of the original strain. Recently, we showed that d-alanine could be safely generated in the bacterium through the conditional expression of a racemase gene from an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible promoter (27). Here, we describe and test a new solution to the problem. We constructed a chimeric plasmid (pRRR) containing (i) a copy of the Bacillus subtilis racemase gene dal surrounded by res1 sites (recognized by the recombination enzyme resolvase) and (ii) an L. monocytogenes actA promoter-regulated resolvase gene, tnpR. The actA promoter and resolvase enzyme are turned “off” when L. monocytogenes is grown in laboratory culture medium but turned “on” (over 200-fold as a result of up-regulation by the actA promoter) upon entry into the cytosol of host cells (9, 32, 49). As a result of the action of this enzyme, the dal gene is excised by recombination at the two res1 sites. The released dal gene fragment, without an origin of replication, is unable to replicate and is lost or destroyed by nuclease. We introduced the pRRR plasmid into L. monocytogenes dal dat to obtain the new strain L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, which we show here to be as efficient as L. monocytogenes dal dat for the stimulation of protective immunity against lethal wild-type L. monocytogenes challenge in mice and to be as attenuated as the original strain, but in the complete absence of exogenously supplied d-alanine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and plasmids.

The double-deletion strain L. monocytogenes dal dat and its wild-type (WT) parent, L. monocytogenes 10403S (referred to hereafter as L. monocytogenes WT), have been previously described (58). Plasmid pRRR (see below) was introduced into L. monocytogenes dal dat by electroporation according to a previously described protocol (37), and the resulting L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR transformants were selected on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates containing 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol. All bacterial strains were maintained as −80°C stocks; streaked onto BHI agar plates with or without d-alanine (200 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml), as necessary; and grown in BHI medium at 30°C with aeration. For infection of mice, an overnight culture of bacteria was diluted 1:10 into appropriate BHI medium, grown with shaking at 30°C for 3 to 4 h, harvested in log phase, dispensed in 1-ml aliquots, and frozen at −80°C until needed. An inoculum of bacteria was then prepared by thawing an aliquot, washing it twice, and diluting it in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Despite the fact that L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR was able to grow in the absence of d-alanine in culture media (see below), to ensure the constancy of plasmid content in cultures, we routinely grew these bacteria for freezing in chloramphenicol-containing media and isolated starting colonies for cultures from chloramphenicol-containing plates.

Plasmid pKSV7, used for cloning, is a shuttle vector capable of replication in both Escherichia coli and L. monocytogenes (50). Plasmid pKSV7-Bsdal contains the B. subtilis racemase gene dal with an intact 562-bp upstream promoter. Plasmids pRES1 and pIVET5n were kind gifts from Andrew Camilli (Tufts University) (11, 44, 45, 53). pRES1 contains two res1 sites, identical to res sites except for a base change at the resolution crossover site which reduces resolution efficiency about 10- to 20-fold. pIVET5n contains the cDNA of tnpR (encoding the site-specific recombinase resolvase) isolated from the transposon Tnγδ.

Construction of chimeric plasmid pRRR.

The chimeric plasmid pRRR was constructed sequentially (47) using pKSV7 as a plasmid backbone. PCR was used to amplify (i) a KpnI/BamHI fragment from L. monocytogenes chromosomal DNA containing the hly gene terminator using primers 5′-GG(GGTACC[KpnI])ACATCGTCCATCTATTTGCC-3′ and 5′-CG(GGATCC[BamHI])TAAAAAAATTAAAAAATAAGCCTG-3′, (ii) a BamHI/SalI fragment from L. monocytogenes chromosomal DNA containing the actA gene promoter using primers 5′-CG(GGATCC[BamHI])AGTTGGGGTTAACTGATTAAC-3′ and 5′-GC(GTCGAC[SalI])TCCCTCCTCGTGATACGC-3′, and (iii) a SalI/HindIII fragment from pIVET5n encoding the resolvase enzyme using primers 5′-GC(GTCGAC[SalI])ATGCGACTTTTTGGTTACGCA-3′ and 5′-CCC(AAGCTT[HindIII])A(TTTATCGTCATCATCCTTATAATC[Flag tag])GTTGCTTTCATTTATTACTTTATATACTGTTG-3′. The PCR fragments were purified and cloned into pGEM-T-EASY cloning vector (Promega, Madison, WI), sequenced to confirm their identity to previously published sequences (GenBank accession numbers M16207, NC_003210, and D16449), and then sequentially subcloned into pKSV7 to create plasmid pKSV7-TPR. PCR was then used to amplify a 1.7-kb XbaI/XbaI fragment from pKSV7-Bsdal encoding the B. subtilis dal gene using primers 5′-GC(TCTAGA[XbaI])GCTTTGAATTTAATAAACAATTTG-3′ and 5′-GCG(TCTAGA[XbaI])TTATTA(TGCATAATCTGGAACATCATATGGATA[hemagglutinin {HA} tag])ATTGCTTATATTTACCTGCAATAAAGG-3′, and after purification and verification of its sequence, the B. subtilis dal gene with upstream promoter was cloned into pRES1. An EcoRI/KpnI fragment (res1-dal-res1) from this plasmid was isolated, purified, and subcloned into pKSV7-TPR to create the final chimeric plasmid pRRR (shown in Fig. 1).

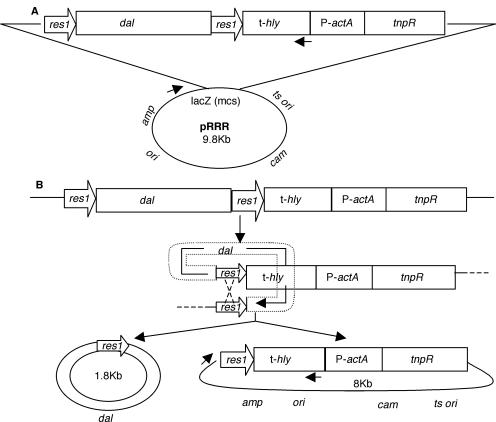

FIG. 1.

Chimeric plasmid pRRR for the regulated expression of the B. subtilis dal gene. (A) Structure of the plasmid. res1, resolvase recombination site; dal, B. subtilis alanine racemase gene; t-hly, L. monocytogenes hemolysin gene (hly) terminator; P-actA, L. monocytogenes actA promoter; tnpR, transposon γδ resolvase gene. The backbone of the plasmid, derived from pKSV7, contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication (ts ori) and a chloramphenicol resistance gene (cam) for plasmid selection in L. monocytogenes and an origin (ori), ampicillin resistance gene (amp), and multiple cloning site (mcs) within the β-galactosidase gene (lacZ) for gene cloning and selection in E. coli. The arrows indicate forward and reverse primers used in the experiment for which results are shown in Fig. 5D. (B) Resolution mechanism that results in excision of the dal gene from pRRR. Recombination involves the binding of resolvase dimers to the two res1 sites, their synapsis, double-strand cleavage, DNA strand exchange, and rejoining.

Intracellular growth.

The mouse macrophage-like J774 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Monolayers were grown on glass coverslips and infected with different strains of L. monocytogenes as described previously (39). At various times after infection, samples of the cultures were taken for Diff-Quik staining (Dade, Miami, FL). Alternatively, for the determination of viable intracellular bacteria, three coverslips at each time point were vortexed in distilled water to lyse the J774 cells, and dilutions of the supernatant were plated on appropriate media.

Plaque formation in L2 cells.

The plaque formation assay was performed as previously described (56). Briefly, confluent monolayers of mouse fibroblast L2 cells in six-well plates were infected with 106 L. monocytogenes organisms for 1 h, washed with PBS, and overlaid with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-10% FCS containing 0.7% agarose and 5 μg/ml gentamicin. The monolayers were stained with neutral red 3 days later, and mean plaque diameters were measured and compared with those of wild-type L. monocytogenes.

L. monocytogenes intracellular proteins.

L. monocytogenes intracellular proteins were prepared as previously described (7). Briefly, J774 cells were infected with L. monocytogenes at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 5.0, and at various times the infected cells were collected, washed to remove extracellular bacteria, and lysed on ice in PBS-0.1% NP-40-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Released intracellular L. monocytogenes bacteria were pelleted and digested with lysozyme (2 mM Tris · Cl, pH 8.0, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.1% lysozyme). Extracted bacterial proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to an Immun-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and either stained with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and counterstained with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) to detect racemase or stained with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to detect resolvase. Blots were developed using the ELC Western Blotting Analysis system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Detection of plasmid resolution products by PCR.

J774 cells were infected with L. monocytogenes, and bacterial extracts were prepared as for L. monocytogenes intracellular proteins, as described above. The lysozyme-digested sample was boiled for 10 min, and 5 μl was taken as a PCR template to detect the resolved or unresolved plasmid molecules using primers 5′-CACACAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCTAAAAAAATTAAAAAATAAGCCTG-3′ (see Fig. 1A).

Mouse infections.

Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were obtained through the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). The animals were infected intravenously (i.v.) with 2 × 107 CFU (L. monocytogenes dal dat or L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR) or 2 × 103 CFU (L. monocytogenes WT) for primary infections (the actual numbers of CFU were assessed following infection). Bacterial titers in the spleens of infected animals were quantified after homogenization of the organ in 3 ml sterile Hanks buffered salt solution, lysis at room temperature in sterile water, and plating of 10-fold serial dilutions on BHI agar supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin. The detection limit of this procedure was 10 CFU/spleen. All procedures used in this study complied with federal guidelines and institutional policies of the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometric analysis to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Surface staining was performed using freshly prepared single-cell suspensions of splenocytes or peritoneal-exudate cells. The cells were stained in 1% (wt/vol) FCS-PBS for 60 min at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-CD11a (clone M17/4; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), phycoerythrin-anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and allophycocyanin-conjugated H-2kd-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-listeriolysin O91-99 (LLO91-99) tetramers (MHC Tetramer Core Facility, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, GA). After being stained, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde-PBS, and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. The data were further analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

RESULTS

Construction of a strain of L. monocytogenes that uses resolvase-mediated recombination to regulate d-alanine racemase expression.

We previously produced the attenuated organism L. monocytogenes dal dat by deletion of two chromosomal genes (dal and dat) used by Listeria for d-alanine synthesis. d-Alanine is required for bacterial cell wall synthesis and growth. Immunization of mice with L. monocytogenes dal dat in the transient presence of d-alanine protects the animals from challenge with the wild-type strain (58). In this paper, we report the construction of a second-generation derivative of L. monocytogenes dal dat that no longer requires exogenous administration of d-alanine while still retaining a high level of attenuation and immunogenicity.

The strategy was to design a chimeric plasmid, pRRR (Fig. 1), that would allow control of d-alanine racemase gene (dal) expression by recombinational excision by the enzyme resolvase. The resulting plasmid contained the following components: (i) the dal gene of B. subtilis regulated by its own promoter (this gene had previously been shown to fully complement the growth defect of L. monocytogenes dal dat [58]); (ii) tnpR, which encodes the site-specific recombinase resolvase derived from transposon Tnγδ (44, 45); (iii) the P-actA promoter, used here to regulate tnpR transcription (this promoter has low basal transcriptional activity in laboratory media but is induced over 200-fold upon entry of L. monocytogenes into the cytosol of infected host cells [9, 32, 49]); and (iv) t-hly, the termination signal of the L. monocytogenes hemolysin gene, which was placed upstream of the actA promoter to ensure that tnpR transcription initiated only at the actA promoter. Thus, the construct was designed to ensure that expression of the resolvase enzyme would be down-modulated to a basal level when bacteria were grown in liquid culture but turned up when the bacteria were exposed to the cytosol of infected animal host cells. Resolvase acts at two short 114-base-pair sequences called res1 sites (11, 33) that we positioned at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the dal gene. Recombination between these two sites by the resolvase enzyme results in excision of the intervening dal gene. As shown in Fig. 1B, the resolution reaction generates a small 1.8-kb circle containing dal-res1, which is not a replicon and is thus degraded by nuclease or diluted during subsequent L. monocytogenes cell divisions and leaves behind an intact circular 8-kb product that is capable of continued replication.

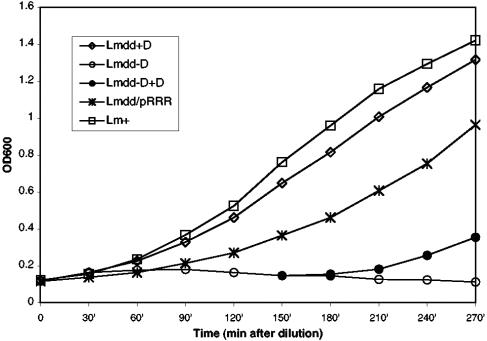

Figure 2 shows that the resulting new strain, designated L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, grew in bacteriological media completely independently of the presence of exogenous d-alanine, although at a somewhat lower rate than L. monocytogenes WT or L. monocytogenes dal dat plus d-alanine. As shown below, this lower rate of growth may result from low but finite basal transcription of the resolvase gene, resulting in some loss of the dal gene from pRRR.

FIG. 2.

d-Alanine independence of the L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR strain. All the strains were grown in liquid BHI medium in the presence (Lmdd+D) or absence (Lmdd-D, Lmdd/pRRR, and Lm+) of exogenous d-alanine (200 μg/ml) at 30°C. An aliquot of the L. monocytogenes dal dat culture (Lmdd-D) was provided with d-alanine at 150 min (Lmdd-D+D). The starting cultures were in the log phase of growth. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Growth of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR in eukaryotic cells is strictly controlled by resolution-regulated racemase gene expression.

L. monocytogenes dal dat is unable to grow within eukaryotic cells, but the defect can be suppressed by the addition of exogenous d-alanine (58). We investigated the ability of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR to replicate in eukaryotic cells without supplementation of d-alanine. J774 cells are mouse macrophage-like cells that readily take up L. monocytogenes by phagocytosis and permit cytoplasmic growth of the organism following its escape from the phagosome. These cells were examined histologically 5 h after infection at an MOI of 5 with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, L. monocytogenes dal dat, and L. monocytogenes WT. Large numbers of bacteria were found associated with the mouse cells infected with both L. monocytogenes WT (Fig. 3A) and L. monocytogenes dal dat in the presence of d-alanine (Fig. 3D), but no bacteria were seen if the amino acid was not supplied during L. monocytogenes dal dat infection (Fig. 3C). However, infection by L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR without addition of d-alanine resulted in significant growth of the organism (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Growth of L. monocytogenes WT (A), L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (B), and L. monocytogenes dal dat (C) in J774 macrophage-like cells at 5 h after infection (at an MOI of 5) without exogenous supplementation of d-alanine. (D) Infection by L. monocytogenes dal dat in the continuous presence of d-alanine (200 μg/ml). The images were captured using a 100× objective lens.

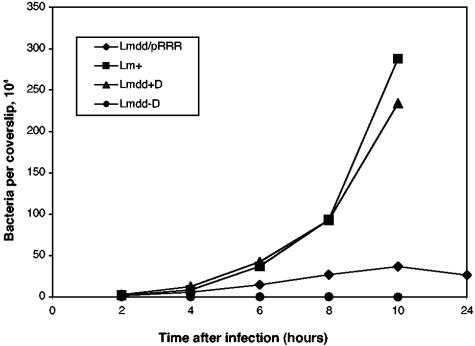

The number of live intracellular bacteria (defined by gentamicin resistance) that could form colonies on BHI medium containing d-alanine was determined at several time points after infection (Fig. 4). As shown previously, L. monocytogenes dal dat alone was unable to replicate in J774 cells (58). Its replication-defective phenotype could be suppressed by the inclusion of d-alanine in the tissue culture medium. On the other hand, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR was able to infect and replicate in J774 cells without any d-alanine supplementation, although it grew more slowly than L. monocytogenes WT or L. monocytogenes dal dat (with d-alanine). At 10 h postinfection, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR stopped dividing, and the number of viable bacteria began to decrease. This is the behavior expected if actA-promoted resolvase expression was activated upon exposure of the organisms to the cytosol of the J774 cells, resulting in enhanced excision of the dal gene from the pRRR plasmid. After approximately four divisions of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, the racemase enzyme and its product, d-alanine, became limiting and resulted in cessation of bacterial growth.

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of intracellular growth in J774 cells. J774 cells were infected with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRR), L. monocytogenes WT (Lm+), and L. monocytogenes dal dat (Lmdd-D) at an MOI of about 0.05 in d-alanine-free medium. L. monocytogenes dal dat infection in one culture (Lmdd+D) was in the continuous presence of d-alanine (200 μg/ml). At various times, samples of the cultures were lysed and the viable intracellular bacteria were enumerated.

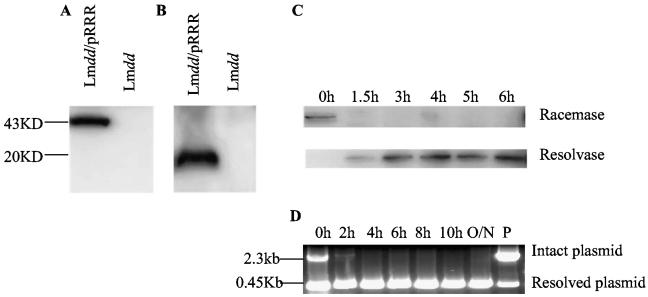

To gain further insight into the control of resolvase-mediated resolution, we examined the expression of both racemase and resolvase by immunoblot analysis during the infection of mouse cells. Racemase was detected as a single band of 43 kDa in extracts of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR grown in BHI medium (Fig. 5A); it was seen only if the plasmid was present and functional. As early as 1.5 h after L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR infection of J774 cells, however, racemase could no longer be detected in extracts of intracellular bacteria (Fig. 5C). Conversely, resolvase, a single band of 20 kDa (Fig. 5B), was not detectable early after infection but was increasingly up-regulated with time postinfection (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that the L. monocytogenes actA promoter functioned as postulated and that induction of resolvase expression resulted in resolution of the pRRR plasmid with strong down-modulation of racemase gene expression.

FIG. 5.

Regulated expression of d-alanine racemase and resolvase after infection of J774 cells. The dal and tnpR gene products, racemase and resolvase, were detected by Western blotting after SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis, and plasmid resolution was detected by PCR analysis. (A) Racemase. L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRRR) and L. monocytogenes dal dat (Lmdd) were grown for 4 h at 30°C in appropriate BHI medium, and proteins were extracted from the bacteria. Racemase is HA tagged (YPYDVPDYA) for detection. (B) Resolvase. J774 cells (5 × 106) were infected with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR or L. monocytogenes dal dat at an MOI of 5. At 5 h postinfection, cells were collected and Listeria proteins were extracted. Resolvase is FLAG tagged (DYKDDDDK) for detection. (C) Kinetics of enzyme expression. J774 cells (5 × 106) were infected with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR at an MOI of 5. At the indicated times after infection, cells were collected and Listeria protein extracts were prepared for the detection of racemase and resolvase. (D) Resolvase-mediated plasmid resolution detected by PCR analysis. J774 cells were infected and bacterial extracts were prepared as in panel C for use as a template for PCR analysis. 0h indicates the Listeria used for infection. P represents the pRRR plasmid prepared in E. coli. The positions of the primers used for PCR analysis are shown as short arrows in Fig. 1. O/N, overnight.

To provide direct evidence for the molecular changes expected with resolution of the pRRR plasmid, a PCR analysis of the system was performed using PCR primers that flanked the res1-dal-res1 segment, allowing detection of resolved and unresolved plasmid molecules. At various times after infection of J774 cells, the cells were lysed, and released bacteria were extracted and subjected to PCR analysis. Although the infecting L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR showed no resolvase protein by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5C, 0 h), PCR analysis indicated that the pRRR plasmid in these bacteria had already experienced some resolution (Fig. 5D, 0 h). It should be noted that the quantity of the resolved species is exaggerated by PCR analysis because of its smaller size. Nevertheless this attests to the high inherent activity of the γδ resolvase enzyme, even at the basal transcription level of the actA promoter. At 2 h postinfection (Fig. 5D, 2 h), resolution was almost complete and only trace amounts of intact pRRR remained. Thereafter (Fig. 5D, 4 h to O/N), no unresolved plasmid was detected by PCR.

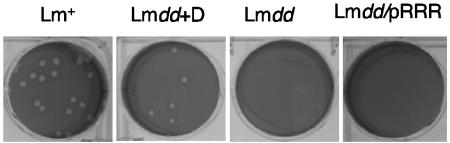

Plaque formation is a measure of the ability of Listeria to spread from cell to cell in monolayers of nonprofessional phagocytic cells. As shown in Fig. 6, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR did not produce detectable plaques in L2 cells. L. monocytogenes dal dat formed plaques only in the presence of d-alanine, and they were somewhat smaller than those produced by wild-type L. monocytogenes. The lack of detectable plaque formation by L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR is an indication that the early turn-off of racemase gene expression did not allow these bacteria to survive throughout the 4-day period required for full plaque formation. In the presence of d-alanine, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR formed normal plaques (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Plaque formation in infected monolayers of mouse L2 fibroblasts. L. monocytogenes WT (Lm+) or L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRRR) was grown in BHI without d-alanine and used to infect monolayers of L2 cells. L. monocytogenes dal dat was grown in BHI with 200 μg/ml of d-alanine and used to infect L2 cells with (Lmdd+D) or without (Lmdd) d-alanine. Plaque formation resulting from intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread of bacteria were visualized after 96 h.

L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR is as attenuated as L. monocytogenes dal dat in mice.

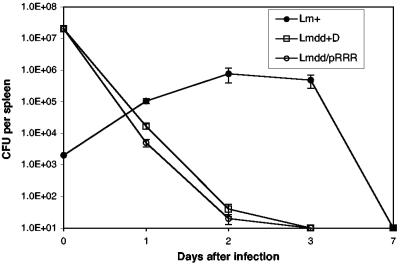

The 50% lethal dose (LD50) of wild-type L. monocytogenes in BALB/c mice is approximately 104 bacteria (4), while the LD50 of the L. monocytogenes dal dat strain is between 7 × 107 and 8 × 108 bacteria (depending on the presence or absence, respectively, of d-alanine in the inoculum) (58). The virulence of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR as measured by its LD50 was examined after i.v. infection of BALB/c mice and found to be approximately 108 bacteria (data not shown), 4 log10 greater than that of wild-type L. monocytogenes. To further examine the virulence of the L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR strain relative to its d-alanine-requiring parent, groups of mice were infected with sublethal doses of either L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR or L. monocytogenes dal dat plus d-alanine. The results in Fig. 7 show that, following tail vein infection with 2 × 107 bacteria, splenic bacteria from both strains fell to almost undetectable levels within 3 days, whereas the lower inoculum of 2 × 103 wild-type L. monocytogenes bacteria resulted in a peak of replication at 2 to 3 days after infection, increasing the number of bacteria by 2 to 3 log units. These results demonstrate that L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR is as attenuated as L. monocytogenes dal dat in mice.

FIG. 7.

Time course of recovery of bacteria from spleens of BALB/c mice after i.v. infection with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRRR) and L. monocytogenes WT (Lm+) in the absence of d-alanine and L. monocytogenes dal dat (Lmdd+D) in the presence of 10 mg of d-alanine in the inoculum. The points at day zero show the total number of viable bacteria injected. CFU per spleen at each time point indicates the mean number ± standard deviation of viable bacteria in the spleens of each group of three mice. The detection limit was 10 CFU.

Immune responses induced by L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR are comparable to those induced by L. monocytogenes dal dat and protect immunized mice against lethal challenge by wild-type L. monocytogenes.

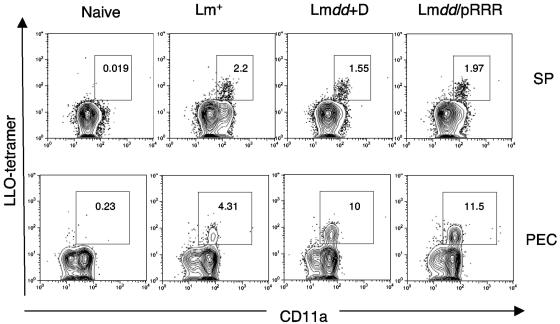

A CD8 T-cell response is essential for immunity to L. monocytogenes. Substantial evidence indicates that CD8 T cells are involved in the primary response and are especially important for protective immunity to secondary L. monocytogenes infection (23, 35). In BALB/c mice, CD8 T cells specific for LLO91-99 comprise the dominant CD8 response (10). Therefore, following sublethal immunization of mice with L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, we assessed this aspect of the immune response in spleens and in peritoneal exudate cells of the animals using an LLO91-99 peptide H-2kd tetramer. Figure 8 shows the primary response in naïve BALB/c mice at day 7 after immunization. In the spleen (Fig. 8, top), substantial populations of LLO-specific CD8 T cells were detected, and most of these showed high expression of CD11a, a β2 integrin that is up-regulated upon activation of CD8 T cells and is present at high levels on memory CD8 T cells (26). L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR and L. monocytogenes dal dat induced comparable percentages (1.97% and 1.55%, respectively), as well as similar total numbers (2.7 × 105 and 2.2 × 105 per spleen, respectively), of LLO-specific T cells (Fig. 9A). Despite infection at the lower dose of 2 × 103, wild-type L. monocytogenes induced a similar percentage of LLO-specific CD8 T cells (2.2%) but a somewhat lower total number of cells (1.9 × 105) (Fig. 9A). In the peritoneum (Fig. 8, bottom), L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR and L. monocytogenes dal dat infections stimulated a much stronger expansion/recruitment of LLO-specific CD8 T cells (11.5% and 10%, respectively) than in the spleen. However, mice vaccinated with wild-type L. monocytogenes showed only a modest expansion of LLO-specific CD8 T cells (4.31%) in this tissue. Similar results were observed when L. monocytogenes immunization was performed intraperitoneally (data not shown). In summary, like L. monocytogenes dal dat in the presence of d-alanine, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR in the absence of d-alanine could stimulate substantial primary antigen-specific CD8 T-cell responses.

FIG. 8.

Immune response induced by L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR. The induction of LLO-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen (top) and peritoneum (bottom) at 7 days after i.v. immunization with 2 × 103 L. monocytogenes WT (Lm+), 2 × 107 L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRRR), or 2 × 107 L. monocytogenes dal dat (Lmdd+D) (with 10 mg d-alanine in the inoculum) bacteria. Splenocytes (SP) and peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) were prepared and stained as described in Materials and Methods. Analysis of gated CD8+ T cells is shown, and the values represent the percentages of activated CD11a+ LLO tetramer+ cells in the CD8 population. Shown is a representative sample from three experiments.

FIG. 9.

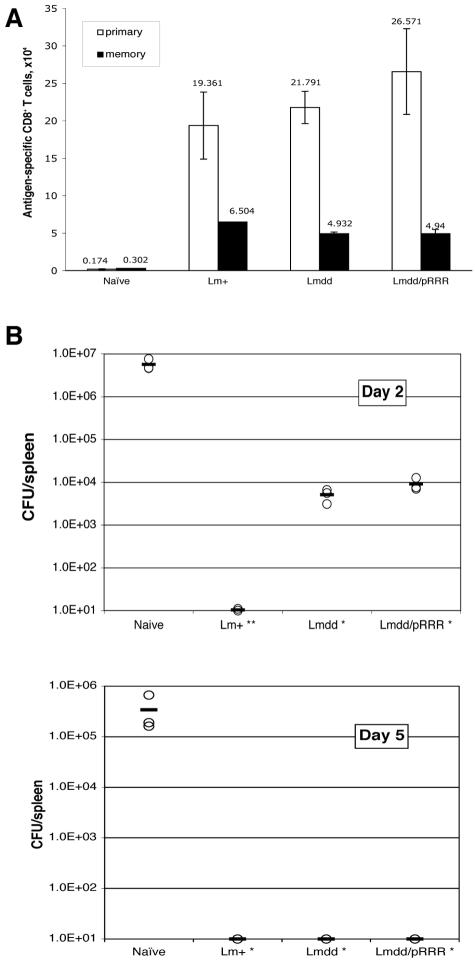

Protection of immunized mice against challenge with wild-type L. monocytogenes. Mice were immunized i.v. with 2 × 103 CFU of L. monocytogenes WT (Lm+), 2 × 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR (Lmdd/pRRR), or 2 × 107 CFU of L. monocytogenes dal dat (with 10 mg d-alanine in the inoculum) (Lmdd+D). (A) Effector and memory immune responses measured as total numbers of antigen-specific CD8 T cells in the spleen. At 7 days (effector cells) or 28 days (memory cells) after immunization, the numbers of LLO91-99-specific CD8 T cells were measured by LLO tetramer staining. The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three mice per group. (B) At 28 days after immunization, mice from the three groups in panel A and naive animals were challenged with 104 CFU of wild-type L. monocytogenes. The numbers of Listeria organisms in spleens were determined 2 and 5 days after challenge. The symbols represent bacterial loads in individual mice (three mice per group) and are representative of three independent experiments. The mean for each set of data is indicated by a bar. Using the two-tailed Student t test, the differences between the values from immunized mice and those from naive mice were significant at a P value of <0.05 (*, day 5 and day 2, L. monocytogenes dal dat and L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR) or a P value of <0.01 (**, day 2, L. monocytogenes WT). The detection limit was 10 CFU per spleen.

Our previous work showed that immunization of mice with L. monocytogenes dal dat produced a long-term memory that enabled the infected host to resist subsequent lethal challenge by wild-type L. monocytogenes. We therefore assessed the level of the memory CD8 T-cell response induced by L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR immunization and also determined whether the induced immunity could confer protection against lethal L. monocytogenes WT challenge. Groups of mice were immunized and, at least 4 weeks later, either sacrificed and analyzed for the number of LLO-specific memory cells or challenged with L. monocytogenes WT to determine their degree of protection. Figure 9A compares the total number of Listeria-specific CD8 T cells in the spleens of naive and infected animals at 7 days, the height of the primary effector response, and 4 weeks later, the level of memory T cells after contraction of that response. As shown, immunization with L. monocytogenes WT, L. monocytogenes dal dat (plus d-alanine), or L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR all resulted in the retention of substantial populations of Listeria-specific memory CD8 T cells in the spleens.

To test for protection in these animals, the bacterial loads in the spleens of challenged mice were examined. Challenged naïve mice had high levels of bacteria in their spleens at 2 and 5 days postinfection (Fig. 9B). In contrast, L. monocytogenes WT-immune mice had no splenic bacteria above the limit of detection at either time point after challenge. The mice that had received a single dose of either L. monocytogenes dal dat or L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR showed a >2-log10 reduction of bacterial numbers on day 2 and a complete reduction in bacterial numbers by day 5, demonstrating substantial protective immunity. The greater protection in the mice immunized with wild-type Listeria may result from the slightly higher level of memory T cells in the spleens of these animals (Fig. 9A).

In summary, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR immunization elicits LLO-specific effector and memory CD8 T cells that protect against lethal challenge by wild-type L. monocytogenes, comparable to results obtained with L. monocytogenes dal dat but in the absence of exogenously supplied d-alanine.

DISCUSSION

In the past few years, there has been a striking increase in the number of listeriosis cases caused by L. monocytogenes (59). Although rare, the disease can be life threatening in newborns, pregnant women, elderly persons, and all immunosuppressed patients (such as organ transplant recipients or HIV patients), with an overall 30% mortality rate (40). Clinical syndromes include sepsis, central nervous system infections, endocarditis, gastroenteritis, and localized infections. Vertical transmission to the fetus often causes miscarriage or stillbirth in pregnant women (14, 21, 51). Since experimental infection is not a clinically ethical option, controlled trials have not allowed a drug of choice or duration of therapy to be established (40). The use of a live attenuated vaccine is thus appealing. The attenuated strain of L. monocytogenes described here, L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, which utilizes a host-induced recombination system to regulate d-alanine availability, appears to provide good immunogenicity while remaining highly attenuated. Therefore, it may be a promising vaccine against listeriosis or act as a vaccine carrier for use against other intracellular bacterial pathogens (31), viruses (19, 22, 28, 48, 54), tumors (6, 38), and parasites (52).

By introducing the suicide plasmid pRRR into L. monocytogenes dal dat, we showed that, when grown in laboratory medium, the resulting strain expressed the racemase enzyme, complementing the requirement of L. monocytogenes dal dat for exogenous d-alanine. L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR was thus able to grow in liquid culture without additional supplementation (Fig. 2). We also showed that L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR was able to grow intracellularly in J774 cells without added d-alanine (Fig. 3 and 4). However, in these cells, growth of the bacteria ceased after about 10 h. Cessation of growth occurred because on exposure to eukaryotic cytosol the plasmid was subject to a resolvase-mediated rearrangement (Fig. 1) that resulted in excision of the dal gene, producing a nonreplicable dal fragment sensitive to dilution and degradation.

Like L. monocytogenes dal dat in the absence of d-alanine, the ability of this organism to form plaques in L2 fibroblast monolayers was greatly impaired (Fig. 6). It is unlikely that this was due to lack of infection of the L2 cells (5) or inability to escape from the phagosome (13), since in the continuous presence of d-alanine, L. monocytogenes dal dat was able to exit the phagosome, grow intracellularly in J774 cells (58), and form plaques in L2 cells (Fig. 6). Rather, it is likely that in the 4 days required for plaque formation, the infecting L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR had lost its ability to replicate as a result of the efficient excision of the dal gene and the subsequent lack of racemase and d-alanine. This failure of cell-to-cell spread may restrict the in vivo intercellular transfer of bacteria from phagocytic cells (macrophages or Kupffer cells in the liver) to nonphagocytic cells (15, 46), contributing to the attenuation of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR during mouse infection. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 7, in mice infected with 0.2 LD50 of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, few bacteria survived for longer than 2 to 3 days. These mice nevertheless elicited a strong LLO-specific effector and memory CD8+ T-cell response (Fig. 8 and 9), protecting the animals against subsequent lethal challenge by wild-type L. monocytogenes (Fig. 9).

Several safety features have been incorporated into the L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR system. (i) To preclude recombination of a plasmid-borne racemase dal gene with the chromosome of the L. monocytogenes dal dat double-deletion strain, we used the dal gene from B. subtilis rather than the autologous gene of L. monocytogenes. The deduced amino acid sequence of the B. subtilis dal gene shares only 50% identity with its Listeria homologue. Nevertheless, as shown previously, the growth defect of L. monocytogenes dal dat could be complemented by a plasmid carrying the B. subtilis gene (58). (ii) The use of the temperature-sensitive pKSV7 backbone limited the number of copies of the racemase dal gene at the temperature of the infected animal. (iii) The resolvase-res1 recombination system (11, 12, 33) regulated by the L. monocytogenes actA promoter allowed control of the expression of the B. subtilis dal gene product, which in turn limited the survival of L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR in infected animals. This could be achieved because of the large difference in L. monocytogenes actA promoter activity in bacteria growing in bacteriological medium versus that in bacteria growing in the cytosol of infected eukaryotic host cells (9, 32, 49). This is shown in Fig. 5C, where the infecting L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, having been grown in BHI medium, was found to contain no detectable resolvase protein by Western blotting, whereas the protein was strongly up-regulated after entry of the bacterium into the cytosol of J774 cells. Nevertheless, the more sensitive PCR analysis shown in Fig. 5D indicated that, despite the low basal activity of the actA promoter in BHI medium, some resolvase activity could be detected, as indicated by the partial resolution of the pRRR plasmid in these cells. Interestingly, resolvase activity was even expressed during preparation of the plasmid in E. coli. As shown (Fig. 2 and 3), this low level of plasmid resolution did not prevent the bacteria from expressing d-alanine-independent growth.

In the present study, we chose i.v. immunization because we required a more precise delivery of bacteria than could be obtained orally, in order to compare the efficacies of L. monocytogenes dal dat and L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR. In the setting of natural infection, however, L. monocytogenes is an agent causing food-borne disease and is thought to spread to various tissues and the placenta from the gastrointestinal tract by hematogenous dissemination (3, 51). Bypassing the gastrointestinal tract could lead to differences in dissemination. Moreover, oral immunization of L. monocytogenes as a vaccine is clearly the preferred route, not only because of the convenience of administration, but also because of the possibility of inducing mucosal immunity at the site of infection for many viral pathogens (19, 22, 48, 54). Using an L. monocytogenes dal dat-based recombinant of L. monocytogenes expressing HIV type 1 gag, we previously showed that oral immunization of BALB/c mice generated protective mucosal anti-HIV gag CD8+ T lymphocytes, thus supporting the possible development of an oral anti-HIV vaccine (18, 41-43). With the genetically modified HuEcad mouse model for orally acquired listeriosis now available (25), it will be interesting to explore L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR as an oral anti-HIV vaccine vector in this model.

The use of L. monocytogenes as a vaccine vector has the advantage of its being a gram-positive microorganism. It does not produce endotoxin and is susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics, thus avoiding the numerous side effects and toxicities of gram-positive lipopolysaccharide. It also avoids the potential dangers of viral vaccine systems. Nevertheless, it is necessary to bear in mind the pathogenic status and unique characteristics of L. monocytogenes. Continued studies of this kind of attenuated gram-positive antibiotic-sensitive vector will surely be of interest for vaccine development in the future. In that regard, several investigators have recently proposed a variety of modifications of L. monocytogenes to generate attenuated strains useful for immunization purposes (1, 6, 55). A comparison of their characteristics will be necessary to evaluate the relative merits of each. The d-alanine-deficient strain, which is completely unable to replicate in the absence of d-alanine and has never shown reversion or suppression in our hands (unpublished data), appears to be a safe and effective candidate upon which to build variants like L. monocytogenes dal dat/pRRR, as described here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Camilli for the kind gift of the pRES1 and pIVET5n plasmids and for helpful discussion of the use of the recombination system, Lee Zeng for his technical assistance in some experiments, and the MHC Tetramer Core Facility, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, GA, for reagents.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-42509 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelakopoulos, H., K. Loock, D. M. Sisul, E. R. Jensen, J. F. Miller, and E. L. Hohmann. 2002. Safety and shedding of an attenuated strain of Listeria monocytogenes with a deletion of actA/plcB in adult volunteers: a dose escalation study of oral inoculation. Infect. Immun. 70:3592-3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelberg, R., and I. S. Leal. 2000. Mutants of Listeria monocytogenes defective in in vitro invasion and cell-to-cell spreading still invade and proliferate in hepatocytes of neutropenic mice. Infect. Immun. 68:912-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakardjiev, A. I., B. A. Stacy, S. J. Fisher, and D. A. Portnoy. 2004. Listeriosis in the pregnant guinea pig: a model of vertical transmission. Infect. Immun. 72:489-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry, R. A., H. G. A. Bouwer, D. A. Portnoy, and D. J. Hinrichs. 1992. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 60:1625-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, L., and P. Cossart. 2000. Interactions between Listeria monocytogenes and host mammalian cells. Microbes Infect. 2:803-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockstedt, D. G., M. A. Giedlin, M. L. Leong, K. S. Bahjat, Y. Gao, W. Luckett, W. Liu, D. N. Cook, D. A. Portnoy, and T. W. Dubensky, Jr. 2004. Listeria-based cancer vaccines that segregate immunogenicity from toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:13832-13837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brundage, R. A., G. A. Smith, A. Camilli, J. A. Theriot, and D. A. Portnoy. 1993. Expression and phosphorylation of the Listeria monocytogenes actA protein in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11890-11894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunt, L. M., D. A. Portnoy, and E. R. Unanue. 1990. Presentation of Listeria monocytogenes to CD8+ T cells requires secretion of hemolysin and intracellular bacterial growth. J. Immunol. 145:3540-3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubert, A., Z. Sokolovic, S. K. Chun, L. Papatheodorou, A. Simm, and W. Goebel. 1999. Differential expression of Listeria monocytogenes virulence genes in mammalian host cells. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:323-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busch, D. H., I. M. Pilip, S. Vijh, and E. G. Pamer. 1998. Coordinate regulation of complex T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. Immunity 8:353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camilli, A., D. T. Beattie, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1994. Use of genetic recombination as a reporter of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2634-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilli, A., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 18:671-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dancz, C. E., A. Haraga, D. A. Portnoy, and D. E. Higgins. 2002. Inducible control of virulence gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes: temporal requirement of listeriolysin O during intracellular infection. J. Bacteriol. 184:5935-5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doganay, M. 2003. Listeriosis: clinical presentation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 35:173-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dussurget, O., J. Pizarro-Cerda, and P. Cossart. 2004. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:587-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farber, J. M., and P. I. Peterkin. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankel, F. R., S. Hedge, J. Lieberman, and Y. Paterson. 1995. Induction of cell-mediated immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein by using Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vector. J. Immunol. 155:4775-4782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman, R. S., F. R. Frankel, Z. Xu, and J. Lieberman. 2000. Induction of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD8 T-cell responses by Listeria monocytogenes and a hyperattenuated Listeria strain engineered to express HIV antigens. J. Virol. 74:9987-9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goossens, P. L., G. Milon, P. Cossart, and M.-F. Saron. 1995. Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes as a live vector for induction of CD8+ T cells in vivo: a study with the nucleoprotein of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Int. Immunol. 7:797-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunn, G. R., A. Zubair, C. Peters, Z. K. Pan, T. C. Wu, and Y. Paterson. 2001. Two Listeria monocytogenes vaccine vectors that express different molecular forms of human papilloma virus-16 (HPV-16) E7 induce qualitatively different T cell immunity that correlates with their ability to induce regression of established tumors immortalized by HPV-16. J. Immunol. 167:6471-6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hitchins, A. D., and R. C. Whiting. 2001. Food-borne Listeria monocytogenes risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. 18:1108-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikonomidis, G., D. Portnoy, W. Gerhard, and Y. Paterson. 1997. Influenza-specific immunity induced by recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccines. Vaccine 15:433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann, S. H. E. 1993. Immunity to intracellular bacteria. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:129-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauvau, G., S. Vijh, P. Kong, T. Horng, K. Kerksiek, N. Serbina, R. A. Tuma, and E. G. Pamer. 2001. Priming of memory but not effector CD8 T cells by a killed bacterial vaccine. Science 294:1735-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292:1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefrancois, L., S. Olson, and D. Masopust. 1999. A critical role for CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in amplification of the mucosal CD8 T cell response. J. Exp. Med. 190:1275-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Z., X. Zhao, D. E. Higgins, and F. R. Frankel. 2005. Conditional lethality yields a new vaccine strain of Listeria monocytogenes for the induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect. Immun. 73:5065-5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieberman, J., and F. R. Frankel. 2002. Engineered Listeria monocytogenes as an AIDS vaccine. Vaccine 20:2007-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marquis, H., H. G. A. Bouwer, D. J. Hinrichs, and D. A. Portnoy. 1993. Intracytoplasmic growth and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes auxotrophic mutants. Infect. Immun. 61:3756-3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michel, E., K. A. Reich, R. Favier, P. Berche, and P. Cossart. 1990. Attenuated mutants of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes obtained by single amino acid substitutions in listeriolysin O. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2167-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miki, K., T. Nagata, T. Tanaka, Y. H. Kim, M. Uchijima, N. Ohara, S. Nakamura, M. Okada, and Y. Koide. 2004. Induction of protective cellular immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by recombinant attenuated self-destructing Listeria monocytogenes strains harboring eukaryotic expression plasmids for antigen 85 complex and MPB/MPT51. Infect. Immun. 72:2014-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moors, M. A., B. Levitt, P. Youngman, and D. A. Portnoy. 1999. Expression of listeriolysin O and ActA by intracellular and extracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 67:131-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murley, L. L., and N. D. Grindley. 1998. Architecture of the gamma delta resolvase synaptosome: oriented heterodimers identify interactions essential for synapsis and recombination. Cell 95:553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paglia, P., I. Ariola, N. Frahm, T. Chakraborty, M. P. Colombo, and C. A. Guzman. 1997. The defined attenuated Listeria monocytogenes delta mp12 mutant is an effective oral vaccine carrier to trigger a long-lasting immune response against a mouse fibrosarcoma. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1570-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pamer, E. G. 2004. Immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:812-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan, Z. K., L. M. Weiskirch, and Y. Paterson. 1999. Regression of established B16F10 melanoma with a recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccine. Cancer Res. 59:5264-5269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park, S. F., and G. S. A. B. Stewart. 1990. High-efficiency transformation of Listeria monocytogenes by electroporation of penicillin-treated cells. Gene 94:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paterson, Y., and G. Ikonomidis. 1996. Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes cancer vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8:664-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portnoy, D. A., P. S. Jacks, and D. J. Hinrichs. 1988. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Exp. Med. 167:1459-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posfay-Barbe, K. M., and E. R. Wald. 2004. Listeriosis. Pediatr. Rev. 25:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rayevskaya, M., N. Kushnir, and F. R. Frankel. 2003. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus-gag CD8+ memory T cells generated in vitro from Listeria-immunized mice. Immunology 109:450-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rayevskaya, M., N. Kushnir, and F. R. Frankel. 2002. Safety and immunogenicity in neonatal mice of a hyperattenuated Listeria vaccine directed against human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 76:918-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rayevskaya, M. V., and F. R. Frankel. 2001. Systemic immunity and mucosal immunity are induced against human immunodeficiency virus Gag protein in mice by a new hyperattenuated strain of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Virol. 75:2786-2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reed, R. R. 1981. Resolution of cointegrates between transposons gamma delta and Tn3 defines the recombination site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:3428-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed, R. R. 1981. Transposon-mediated site-specific recombination: a defined in vitro system. Cell 25:713-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robbins, J. R., A. I. Barth, H. Marquis, E. L. de Hostos, W. J. Nelson, and J. A. Theriot. 1999. Listeria monocytogenes exploits normal host cell processes to spread from cell to cell. J. Cell Biol. 146:1333-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 48.Shen, H., M. K. Slifka, M. Matloubian, E. R. Jensen, R. Ahmed, and J. F. Miller. 1995. Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vehicle for the induction of protective anti-viral cell-mediated immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3987-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shetron-Rama, L. M., H. Marquis, H. G. Bouwer, and N. E. Freitag. 2002. Intracellular induction of Listeria monocytogenes actA expression. Infect. Immun. 70:1087-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, K., and P. Youngman. 1992. Use of a new integrational vector to investigate compartment-specific expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIM gene. Biochimie 74:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith, M. A., K. Takeuchi, R. E. Brackett, H. M. McClure, R. B. Raybourne, K. M. Williams, U. S. Babu, G. O. Ware, J. R. Broderson, and M. P. Doyle. 2003. Nonhuman primate model for Listeria monocytogenes-induced stillbirths. Infect. Immun. 71:1574-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soussi, N., G. Milon, J. H. Colle, E. Mougneau, N. Glaichenhaus, and P. L. Goossens. 2000. Listeria monocytogenes as a short-lived delivery system for the induction of type 1 cell-mediated immunity against the p36/LACK antigen of Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 68:1498-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stark, W. M., N. D. Grindley, G. F. Hatfull, and M. R. Boocock. 1991. Resolvase-catalysed reactions between res sites differing in the central dinucleotide of subsite I. EMBO J. 10:3541-3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevens, R., K. E. Howard, S. Nordone, M. Burkhard, and G. A. Dean. 2004. Oral immunization with recombinant Listeria monocytogenes controls virus load after vaginal challenge with feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 78:8210-8218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stritzker, J., J. Janda, C. Schoen, M. Taupp, S. Pilgrim, I. Gentschev, P. Schreier, G. Geginat, and W. Goebel. 2004. Growth, virulence, and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutants. Infect. Immun. 72:5622-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun, A. N., A. Camilli, and D. A. Portnoy. 1990. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect. Immun. 58:3770-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szalay, G., C. H. Ladel, and S. H. E. Kaufmann. 1995. Stimulation of protective CD8+ T lymphocytes by vaccination with nonliving bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12389-12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson, R. J., H. G. A. Bouwer, D. A. Portnoy, and F. R. Frankel. 1998. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a Listeria monocytogenes strain that requires d-alanine for growth. Infect. Immun. 66:3552-3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wing, E. J., and S. H. Gregory. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes: clinical and experimental update. J. Infect. Dis. 185(Suppl. 1):S18-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]