Abstract

This study aimed to encapsulate bioactive peptides derived from Sargassum angustifolium protein isolate within calcium alginate and chia seed gum matrices using freeze-drying. The encapsulated microbeads and microcapsules were evaluated based on encapsulation efficiency (EE), surface charge (zeta potential), microstructure, chemical composition, and thermal properties. Results indicated that Alg-SAPH exhibited a higher EE compared to CSG-SAPH. Alg-SAPH microbeads displayed a more negative zeta potential than CSG-SAPH microcapsules, suggesting enhanced electrostatic stability. Structural analysis revealed that Alg-SAPH formed interconnected microbead chains, whereas CSG-SAPH demonstrated a shell-like morphology. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis showed that Alg-SAPH had a lower melting point compared to CSG-SAPH, whereas its transition enthalpy was significantly higher. The findings suggest that encapsulating SAPH within biopolymeric carriers enhances its stability and bioavailability, offering a promising approach for incorporating bioactive peptides into functional foods and therapeutic applications while masking their undesirable taste.

Keywords: Bioactive peptides, Calcium alginate, Chia seed gum, Encapsulation, Sargassum angustifolium

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Bioactive peptides extracted from Sargassum angustifolium (SAPH).

-

•

The SAPH were encapsulated in calcium alginate (Alg) and chia seed gum (CSG).

-

•

Alg-SAPH had higher encapsulation efficiency (88.48 %) than CSG-SAPH (77.24 %).

-

•

Alg-SAPH microbeads had more negative charges than CSG-SAPH microcapsules.

-

•

SAPH enhances their stability for use in food and health applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the extraction and functionalization of algal proteins have garnered increasing attention due to their vast potential in food, pharmaceutical, and biomedical industries (Akcicek et al., 2021). Among various marine algae, Sargassum angustifolium, a brown macroalga native to the Persian Gulf and harvested in both summer and winter, has been identified as a rich source of essential biopolymers such as alginate (20.9–22.4 % w/w), glucan (36.2–43.1 % w/w), lignin-like polyphenols (11.8–25.8 % w/w), and ash (35.5–43.8 % w/w), along with considerable protein content that varies seasonally (Antigo et al., 2020).

Despite its promising nutritional composition, the direct use of algal proteins in functional applications is often limited by their low digestibility and bioavailability, attributed to complex globular structures. To address this, enzymatic hydrolysis particularly using Alcalase has been widely adopted to produce bioactive peptides (BAPs) with enhanced functional and physiological properties (Apoorva et al., 2020). However, these hydrolysates are prone to degradation under gastrointestinal (GI) conditions and often possess undesirable sensory characteristics, such as bitterness, which limit their incorporation into commercial formulations (Ardalan et al., 2018). Encapsulation has emerged as an effective approach to overcome these challenges by improving peptide stability, masking bitter taste, and enabling targeted release to specific sites of action in the GI tract (Bao et al., 2019). Several delivery systems ranging from self-assembled carriers to nano-hydrogels and biopolymer-based matrices have been investigated for their ability to protect and release bioactive molecules in a controlled manner (Capitani et al., 2016). Recent research has increasingly focused on the encapsulation of marine-derived protein hydrolysates, demonstrating that such strategies can enhance their antioxidant capacity, thermal stability, and sustained release under simulated gastrointestinal conditions (Mohammadi et al., 2022). Such advances highlight the necessity of selecting appropriate biopolymeric carriers to optimize the delivery efficiency of algal peptides in food systems. Recent advancements have particularly focused on natural, food-grade biopolymers, such as calcium alginate (Alg) and chia seed gum (CSG), due to their biocompatibility, gel-forming capacity, and suitability for controlled delivery applications (Diana et al., 2021; Forutan et al., 2022). Calcium alginate forms cross-linked hydrogel beads that are stable in acidic environments and offer mechanical protection to encapsulated compounds. On the other hand, CSG, a hydrophilic, anionic heteropolysaccharide rich in functional groups, contributes to matrix integrity and sustained release by increasing viscosity and forming cohesive gels (Goh et al., 2016).

In addition, chia seed gum has been shown to possess excellent emulsifying, stabilizing, and film-forming properties, making it a multifunctional candidate for encapsulation technologies in functional food and nutraceutical applications. Its molecular structure supports both ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions, facilitating the entrapment of bioactive compounds under mild processing conditions (Timilsena et al., 2021). Recent studies support the suitability of both materials for delivering sensitive bioactives, including polyphenols, vitamins, and peptides, under simulated digestive conditions (Diana et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2019).

While numerous reports have addressed the encapsulation of plant-derived peptides, only a few studies have focused specifically on peptides derived from S. angustifolium. In our previous work, we demonstrated the antioxidant potential and techno-functional properties of S. angustifolium protein hydrolysates, confirming their relevance for functional food formulations (Jafarirad et al., 2023). Furthermore, our recent in vitro investigation showed that probiotic yogurt fortified with these peptides exhibited suitable inhibitory activity against Streptococcus mutans, highlighting their potential in oral health applications (Jafarirad et al., 2025).

Despite these promising findings, the structural instability and sensitivity of hydrolyzed peptides during digestion necessitate further improvement. Therefore, the present study addresses this gap by comparing two biopolymer-based encapsulation systems: calcium alginate and chia seed gum, for their effectiveness in protecting and delivering S. angustifolium peptides. The novelty of this study stems from a comparative encapsulation of bioactive peptides derived specifically from Sargassum angustifolium a brown macroalga native to the Persian Gulf using two distinct natural biopolymer matrices: calcium alginate and chia seed gum. While previous studies have explored encapsulation of plant or microalgal peptides, little attention has been given to S. angustifolium derived peptides and their stabilization within food-grade matrices. This is the first study to systematically evaluate and compare encapsulation efficiency, physicochemical stability (zeta potential, thermal behavior, and microstructure), and release potential of these two systems under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, highlighting their suitability for functional food and nutraceutical applications. By enhancing peptide stability and bioavailability, this study supports the application of marine-derived bioactives in the development of next-generation functional foods and nutraceuticals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Calcium alginate with a molecular weight of 120,000–190,000 g/mol and CaCl2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Germany). CSG was purchased from a local producer (Tehran, Iran). The solvents and other chemicals used in this study were prepared (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Protein extraction from Sargassum angustifolium and its hydrolysis by Alcalase

The protein from Sargassum angustifolium was extracted using an alkalization-precipitation technique (Wei et al., 2019). The extracted protein, referred to as Sargassum angustifolium protein isolate (SAPI), was freeze-dried and subsequently hydrolyzed. Under optimized conditions, SAPI (2 % w/v) was heated at 90 °C for 10 min to facilitate structural unfolding. The solution was then cooled to 35–40 °C, and the pH was adjusted to 7. Hydrolysis was performed using alcalase at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 2 % (w/w) at a temperature of 60–65 °C for 90 min. Enzyme inactivation was achieved by heating at 90 °C for 10 min. The hydrolysate solution was subsequently cooled to 30 °C and centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 15 min. The supernatant, containing soluble peptides, was collected and freeze-dried at −48 °C. The lyophilized powder, referred to as Sargassum angustifolium protein hydrolysate (SAPH), was stored at 4 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Encapsulation of protein hydrolysates

2.3.1. Preparation of alginate microbeads

Alginate microbeads containing SAPH were prepared using a modified protocol based on Raei et al. [15]. A 3 % (w/v) calcium alginate solution was prepared by dissolving alginate in deionized hot water and stirring vigorously for 10 min. Separately, 10 g of SAPH was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water (10 % w/v) at pH 5.5, and the solution was allowed to hydrate overnight. The SAPH and alginate solutions were then mixed at a 1:10 (w/w) ratio and stirred at 1000 rpm for 1 h to ensure complete homogeneity. To improve dispersion and reduce aggregation, the mixture was sonicated at 100 W for 1 min. The final solution was then transferred into a syringe and added dropwise into 150 mL of calcium chloride solution (3 % w/v) to induce gelation through ionic crosslinking.

The formed microbeads were allowed to cure at 4 °C for 30 min to stabilize the structure, after which they were collected by centrifugation at 6000 ×g for 15 min. Finally, the obtained alginate microbeads encapsulating SAPH (Alg-SAPH) were freeze-dried (lyophilized) and stored at 4 °C until further analysis.

2.3.2. Preparation of CSG microcapsules

The CSG microcapsules were synthesized by initially dissolving chia seed gum (0.1 % w/v) in deionized water under constant stirring at 500 rpm for 2 h to ensure complete hydration. Simultaneously, Sargassum angustifolium protein hydrolysate (SAPH) was dissolved in deionized water at a concentration of 10 % (w/v) and allowed to hydrate overnight at pH 5.5. The hydrated SAPH solution was then blended with the pre-hydrated CSG solution in a 1:10 (w/w) ratio and stirred at 800 rpm for 1 h. To enhance dispersion and reduce particle aggregation, the mixture was sonicated at 100 W for 1 min. Microcapsules were subsequently formed by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 30 min. The resulting encapsulated SAPH was collected, freeze-dried, and stored at 4 °C until further analysis [11, 15]. This method facilitated efficient encapsulation, helping to improve the stability and controlled release of bioactive peptides.

2.4. Encapsulation efficiency (EE)

Encapsulation efficiency (EE) was determined according to the method described by Niazi Tabar et al. (Niazi Tabar et al., 2025). The concentration of encapsulated SAPHs was indirectly quantified by measuring the concentration of non-entrapped SAPHs. Initially, the sample was passed through a 100 kDa ultrafiltration membrane under 10 psi pressure to separate the hydrolysates encapsulated within the microcapsules and/or microbeads from those remaining free in the matrix. The protein content of the filtrate was assessed using the Lowry method with a Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Richmond, CA, USA). EE was calculated using Eq. 1:

| (1) |

Encapsulated hydrolysates = Total hydrolysates – non-encapsulated hydrolysates.

2.5. Zeta potential

The surface charge of the microcapsules and/or microbeads was determined by measuring the zeta potential using a dynamic light scattering system (Zetasizer, Malvern Instruments, UK) in zeta mode (Javadpour et al., 2025). The samples were diluted 100-fold to ensure adequate light transmission. Measurements were conducted at ambient temperature.

2.6. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological characteristics of the microcapsules and/or microbeads were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples were coated with palladium and mounted onto aluminum stubs using double-sided adhesive carbon tape. Micrographs were captured at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV with a magnification of 1000 X (Shojaei et al., 2019).

2.7. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical structure of the microcapsules and/or microbeads was analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Spectrum 100, Perkin-Elmer, USA). The samples were pressed into KBr pellets and scanned within the spectral range of 4000 to 650 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1 (Sheybani et al., 2023).

2.8. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The thermal characteristics of the microcapsules and/or microbeads were examined using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC-028, Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH). Briefly, 10 mg of Alg-SAPH and CSG-SAPH samples were weighed into aluminum pans and hermetically sealed. The samples were heated from 0 to 300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min (Vakilian et al., 2024).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 23). Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's test to determine significant differences between means. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Encapsulation efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of Alg-SAPH and CSG-SAPH was evaluated and is presented in Table 1. The results indicate that Alg-SAPH microbeads exhibited significantly higher EE (88.48 %) compared to CSG-SAPH microcapsules (77.24 %).

Table 1.

Encapsulation efficiency (%) and zeta-potential of Alg microbeads and CSG microcapsules containing SAPH.⁎

| Samples | EE (%) | Zeta-potential |

|---|---|---|

| Alg-SAPH | 88.48 ± 0.57a | −29.60 ± 1.5a |

| CSG-SAPH | 77.24 ± 0.90b | −19.64 ± 1.2b |

Different small superscript letters show significant difference in the columns (p < 0.05).

This difference is primarily attributed to the superior gelation behavior and cross-linking ability of alginate, which provides a more compact and stable network for entrapping peptides efficiently (Apoorva et al., 2020; Raei et al., 2015).

Alginate is composed of β-D-mannuronic acid (M-block) and α-L-guluronic acid (G-block), linked via 1–4 glycosidic bonds. This structure forms stable hydrogels in the presence of divalent cations like Ca2+, creating a three-dimensional network that enhances physical entrapment of bioactives (Bao et al., 2019). The so-called “egg-box” model describes this cross-linking mechanism, which contributes to the high mechanical strength and encapsulation capability of alginate-based carriers (Apoorva et al., 2020). Additionally, Alg-SAPH microbeads displayed a more negative zeta potential (−29.60 mV) than CSG-SAPH microcapsules (−19.64 mV), suggesting enhanced electrostatic stability. The strong negative surface charge of alginate contributes to greater electrostatic repulsion between particles, reducing aggregation and facilitating more uniform dispersion, which may indirectly improve EE (Mohan et al., 2016). Another critical factor is alginate's pH-responsive behavior: it forms an insoluble alginic acid matrix under acidic gastric conditions thus protecting the core peptides and swells in the small intestine's alkaline environment, promoting controlled release (Bao et al., 2019; Raei et al., 2015). Furthermore, higher concentrations of alginate provide more binding sites for calcium ions, resulting in a denser gel structure with improved peptide retention. Use of other biopolymers in composite systems has also shown potential in enhancing EE. For instance, alginate-tragacanth gum hydrogels demonstrated increased peptide entrapment due to hydrogen bonding and improved gel strength (Apoorva et al., 2020). On the other hand, chia seed mucilage (CSG) is a natural polysaccharide rich in carboxylic acid groups, which facilitate complexation with positively charged molecules. In this study, SAPH peptides (at pH 5.5) were successfully entrapped within the negatively charged CSG matrix, achieving an EE of 77.24 %. Although slightly lower than alginate, this is still a relatively high efficiency, attributable to the viscoelastic and emulsifying properties of CSG (Capitani et al., 2016; Timilsena et al., 2021). Chia seed mucilage has previously been applied as an encapsulant in combination with maltodextrin and gum arabic for sensitive compounds such as beet dye (Antigo et al., 2020), essential oils, and vitamins. Its high water-binding capacity and ability to form cohesive films are critical factors in entrapment efficiency (Timilsena et al., 2021). CSG also exhibits shear-thinning behavior and increases system viscosity, which can help reduce diffusion of encapsulated materials, particularly under mild processing conditions (Capitani et al., 2016). Furthermore, CSG contains 2.6–18 % protein, depending on extraction conditions, which enhances its emulsification capacity and interaction with peptides (Punia & Dhull, 2019). In summary, while both systems showed acceptable performance, Alg-SAPH demonstrated significantly higher encapsulation efficiency, mainly due to its superior ionic cross-linking ability, greater charge density, and more compact gel network, making it a more effective system for protecting bioactive peptides in food and pharmaceutical applications.

3.2. Zeta potential

Zeta potential analysis provides critical information regarding the surface charge, electrostatic interactions, and colloidal stability of encapsulated systems. As shown in Table 1, both Alg-SAPH and CSG-SAPH exhibited negative zeta potential values, indicative of electrostatic repulsion among particles, which is essential for preventing aggregation and ensuring dispersion uniformity in aqueous media.

The zeta potential of Alg-SAPH microbeads was −29.60 ± 1.5 mV, significantly more negative than that of CSG-SAPH microcapsules (−19.64 ± 1.2 mV), reflecting a higher charge density and superior colloidal stability in the alginate-based system.

This pronounced negativity in alginate beads is attributed to the high abundance of carboxylate (-COO−) groups present in the α-L-guluronic and β-D-mannuronic acid units of alginate, which dissociate at pH values above ∼3.5, generating strong negative surface charges (Bao et al., 2019; Narsaiya & Majumdar, 2022). In addition, the egg-box model of calcium alginate gelation facilitates dense ionic crosslinking with Ca2+, which not only reinforces the polymer network but also immobilizes surface charges on the microbeads, further contributing to zeta potential stability (Apoorva et al., 2020). Moreover, the spatial configuration of alginate chains leads to a more exposed carboxylate surface, increasing the effective surface charge, especially after freeze-drying when water is removed and charge concentration per unit surface area increases. This structural configuration contributes to the significantly stronger electrostatic repulsion between Alg-SAPH particles, enhancing suspension stability.

In contrast, CSG-SAPH microcapsules displayed a moderately negative zeta potential, indicating lower electrostatic repulsion and a more loosely organized matrix structure. Chia seed gum is composed of neutral and weakly anionic polysaccharides, including xylose, glucose, and minor glucuronic acid residues, which provide fewer dissociable functional groups (Timilsena et al., 2021). Furthermore, the molecular conformation of CSG leads to entangled gel structures with less regular exposure of anionic groups, resulting in a lower surface charge density compared to alginate.

Another critical factor is the interaction of the encapsulated peptides with the matrix. At pH 5.5, SAPH peptides may carry partial positive or neutral charge depending on their isoelectric point (pI). In Alg-SAPH, strong ionic interactions occur between negatively charged alginate and positively charged residues on peptides, stabilizing the surface charge distribution. In CSG-SAPH, however, the interactions may be dominated by hydrogen bonding and weaker van der Waals forces, which do not contribute significantly to net surface charge (Forutan et al., 2022; Javadpour et al., 2025).

Importantly, zeta potential plays a direct role in encapsulation efficiency (EE). The higher negative surface charge in Alg-SAPH supports greater electrostatic attraction to positively charged regions of peptides, promoting tighter entrapment and reduced diffusion. This is consistent with the observed higher EE of Alg-SAPH (88.48 %) compared to CSG-SAPH (77.24 %), and also explains why Alg-SAPH showed better thermal and structural stability in DSC and FTIR analyses. Finally, from an application standpoint, a zeta potential greater than |25 mV| is generally considered the threshold for electrostatically stable colloidal systems, especially in food and pharmaceutical emulsions (Narsaiya & Majumdar, 2022). Based on this criterion, Alg-SAPH offers superior physical stability, making it more suitable for long-term storage and GI delivery. However, CSG-SAPH remains acceptable for systems where moderate stability and controlled release are prioritized.

3.3. Scanning electron microscopy

The morphological characteristics of Alg-SAPH microbeads and CSG-SAPH microcapsules were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 1). The Alg-SAPH microbeads exhibited noticeable shrinkage and surface wrinkles, likely due to the strong electrostatic interactions between calcium ions (Ca2+) and alginate polymer chains, which result in a denser hydrogel network during the gelation process (Apoorva et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2019). This compact structure could contribute to improved encapsulation efficiency and mechanical stability of the microbeads (Mohammadi et al., 2022). In contrast, CSG-SAPH microcapsules displayed a smoother, more spherical morphology, which can be attributed to the viscoelastic properties of chia seed gum (Capitani et al., 2016; Timilsena et al., 2021). The hydrophilic nature of chia seed gum facilitates uniform gelation, leading to a more homogeneous microcapsule structure. Similar surface characteristics have been reported in previous studies on chia seed gum-based encapsulation systems (Akcicek et al., 2021).

Fig. 1.

SEM micrographs of Alg-SAPH and CSG-SAPH encapsulates at magnification of 1000×.

The development of surface depressions in Alg-SAPH microbeads aligns with previous findings on pectin/high-amylose corn starch microcapsules, where water evaporation during freeze-drying caused minor structural deformations (Sheybani et al., 2023). The higher cross-linking density in Alg-SAPH microbeads might further contribute to surface irregularities. Additionally, minor cracks, particularly on larger Alg-SAPH microbeads, could be a result of electron beam interactions during SEM imaging, which has also been observed in alginate-based encapsulation systems (Anand et al., 2024).

Moreover, the pronounced wrinkling and collapse seen in Alg-SAPH beads can be explained by the rapid sublimation of ice crystals during freeze-drying, which places intense mechanical stress on the compact ionic network a phenomenon similarly observed in bioreactor-integrated alginate microcarriers assessed by Balsters et al. (2025) using trehalose as cryoprotectant (Balsters et al., 2025). In parallel, the dense ionic crosslinking not only imparts structural integrity but also limits water migration, resulting in localized internal fissures once the hydrogel's mechanical threshold is exceeded (Odziomek et al., 2024).

These structural features correlate with higher encapsulation efficiency and reduced water permeability, enhancing protection of bioactive peptides and ensuring slower release profiles (Mohammadi et al., 2022). In larger Alg-SAPH beads, minor cracks may also appear due to localized thermal expansion during SEM beam interaction with residual moisture, an artifact previously noted in semiquantified hydrogel analyses (Akcicek et al., 2021).

In contrast, CSG-SAPH microcapsules displayed a smoother, more spherical and uniform surface, attributable to the intrinsically viscoelastic and hydrophilic nature of chia seed gum, which promotes gentler gelation and a flexible network structure. The random-coil polymer structure retains more internal moisture and mitigates collapse during freeze-drying, resulting in an uncollapsed morphology ideal for controlled-release systems (Timilsena et al., 2021). Furthermore, freeze-dried chia gum–gelatin microcapsules prepared at similar solids content preserved pore integrity and retained high bioactive load, with SEM images showing smooth, macroporous surfaces reflecting a balanced drying kinetics (Anand et al., 2024). This suggests that chia-based matrices can better accommodate volumetric changes without structural collapse (Balsters et al., 2025; Odziomek et al., 2024).

These morphological differences densely wrinkled Alg-SAPH vs. smooth, hydrated CSG-SAPH highlight the distinct gelation mechanisms and structural behaviors of the two polymers. Alginate's dense ionic crosslinking provides robust protection (Apoorva et al., 2020; Odziomek et al., 2024), while chia seed gum's softer matrix favors rapid hydration and matrix flexibility (Timilsena et al., 2021), offering tunable delivery options. Finally, such structural contrasts are critical in applications: the mechanically rigid Alg-SAPH beads are suited for environments requiring prolonged integrity under shear or pH changes (Balsters et al., 2025), whereas CSG-SAPH capsules, with their flexible, hydrated shell, are better positioned for digestive release or food applications where texture and mouthfeel are key considerations (Anand et al., 2024).

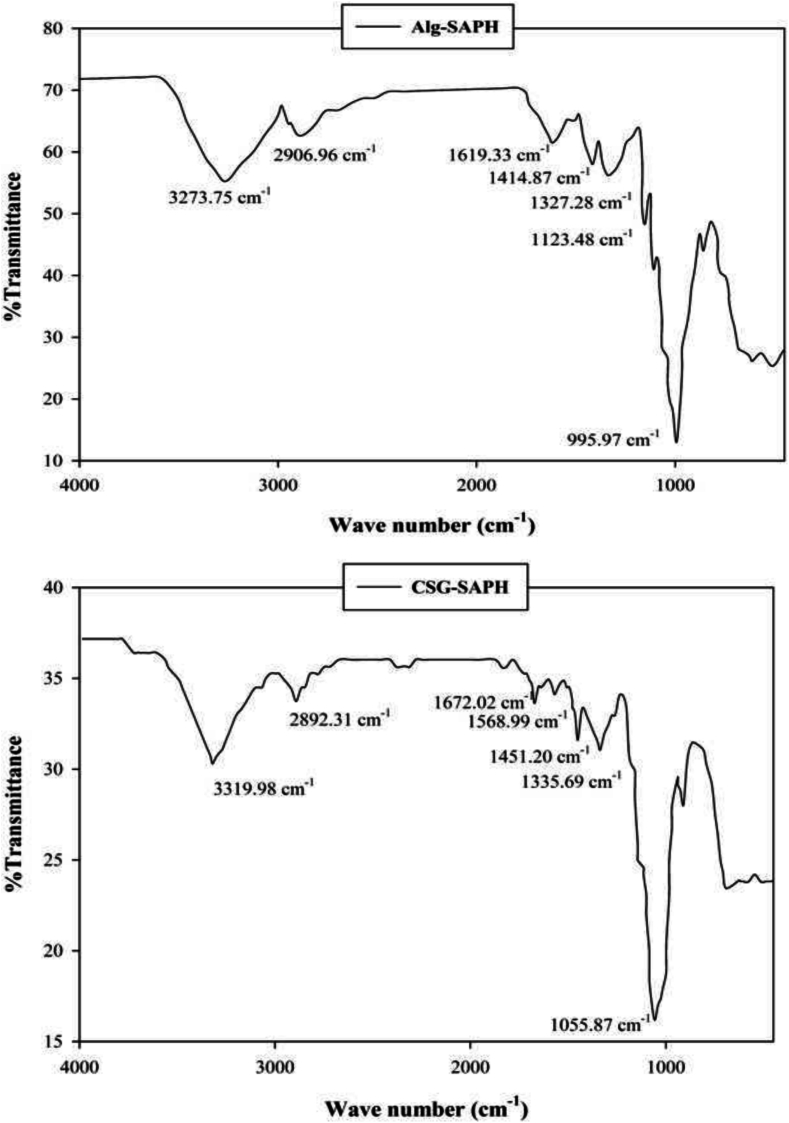

3.4. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in Fig. 2, provided detailed insights into the molecular interactions between Sargassum angustifolium protein hydrolysates (SAPH) and the biopolymeric encapsulation matrices calcium alginate (Alg) and chia seed gum (CSG). In the spectrum of Alg-SAPH microbeads, a broad absorption band appeared at 3273 cm−1, which corresponds to the stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (-OH) and amine (-NH₂) groups. This overlap indicates the formation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups in alginate and the amino groups in the peptides, a phenomenon that contributes to the stabilization of encapsulated peptides through non-covalent interactions (Timilsena et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2019). These hydrogen bonds reduce the molecular mobility of peptides and contribute to the resistance of the matrix against environmental and gastrointestinal degradation (Mohamed et al., 2024). The presence of a peak at 2906 cm−1, attributed to C—H stretching vibrations of methyl and methylene groups, further suggested the contribution of hydrophobic amino acid residues such as leucine and valine to stabilizing interactions within the matrix. Such hydrophobic interactions may improve the entrapment by increasing the affinity between the peptide core and the polymeric shell (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2024). A strong amide I band at 1619 cm−1 and accompanying amide III bands at 1414 and 1327 cm−1 confirmed the successful incorporation of SAPH peptides into the polymeric network. These bands, which originate from C O stretching and N—H bending, respectively, are reliable markers for assessing the secondary structure of proteins and their preservation during the encapsulation process. In addition, the characteristic peak at 995 cm−1, associated with guluronic acid blocks in alginate, confirmed the retention of the polymer's structure and the formation of a crosslinked “egg-box” gelation model with calcium ions, which is key to the encapsulation mechanism and mechanical integrity of alginate systems (Wei et al., 2019). This specific structural configuration supports the formation of a dense ionic network that helps retain small peptides and minimizes premature leakage (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2024).

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectra of Alg-SAPH microbeads and CSG-SAPH microcapsules.

The FTIR spectrum of CSG-SAPH microcapsules displayed some similar features but with notable differences. A broad and more intense absorption band was observed at 3319 cm−1, which is indicative of a higher density of hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups in chia seed gum. This suggests the formation of stronger hydrogen bonding within the CSG matrix and between the matrix and the peptides. Such strong hydrogen bonding has been linked to enhanced swelling capacity and moisture retention in chia-based films and hydrogels (Khatoon et al., 2025).

The intensity of this band, higher than that observed in Alg-SAPH, implies a more hydrated and flexible gel structure that can support greater swelling and possibly a more rapid release of peptides. A peak at 2892 cm−1 confirmed the presence of C—H bonds from the incorporated peptides. The amide I band at 1672 cm−1 and a weaker amide II band at 1568 cm−1 provided further evidence of peptide incorporation, though with lower intensity compared to Alg-SAPH. This observation is in agreement with the lower encapsulation efficiency measured for CSG-SAPH (77.24 %) versus Alg-SAPH (88.48 %). The spectral region around 1335 cm−1 showed C—O, C—N, and C—H stretching vibrations, pointing to additional hydrogen bonding and polar interactions between SAPH and the chia polysaccharides. Moreover, the sharp peak at 1055 cm−1, characteristic of chia gum polysaccharides, indicates the integrity of the CSG network even after peptide loading and freeze-drying. These bands suggest that the chia matrix maintains its molecular conformation and does not collapse significantly during lyophilization, which is beneficial for sustained release applications (Abdel-Aty et al., 2024).

Comparative analysis of the spectra revealed that Alg-SAPH microbeads demonstrated stronger and more defined peptide–polymer interactions, promoting a more compact and stable encapsulation structure. The dominance of ionic interactions in the alginate system, reinforced by calcium ions, enhances peptide retention and provides thermal and colloidal stability. In contrast, the chia matrix operates primarily through hydrogen bonding and provides a more hydrated and diffusion-prone environment, allowing faster peptide release. These mechanistic differences indicate that alginate is more suitable for long-term protection and delayed release, whereas chia gum is favorable for rapid and moisture-responsive delivery scenarios (Abdel-Aty et al., 2024; Mohamed et al., 2024).

3.5. Differential scanning calorimetry

The thermal behavior of Alg-SAPH microbeads and CSG-SAPH microcapsules was investigated using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and the thermograms are presented in Fig. 3. The DSC curve for Alg-SAPH displayed a distinct endothermic peak at 70.89 °C, accompanied by an enthalpy value of +119.23 mJ/mg. In contrast, CSG-SAPH exhibited a thermal transition at a higher temperature of 87.41 °C but with a lower enthalpy of +72.40 mJ/mg. These thermal events primarily reflect the melting behavior of the encapsulation matrices and indicate differences in polymer–peptide interactions, encapsulation efficiency, and structural cohesion (Abdel-Aty et al., 2024; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2024).

Fig. 3.

DCS thermogram of Alg-SAPH microbeads and CSG-SAPH microcapsules.

The reduced melting point observed in Alg-SAPH, compared to pure alginate (∼100 °C), suggests that SAPH peptides disrupt the regular molecular organization of the alginate matrix. The presence of peptides likely increases the spacing between alginate chains, thereby diminishing overall thermal stability. This phenomenon has similarly been reported in other alginate-based systems, where the inclusion of low molecular weight bioactives alters crystallinity and promotes earlier thermal transitions (Mohamed et al., 2024). This effect can also be attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions between SAPH and guluronic acid residues within alginate. While these interactions enhance entrapment, they simultaneously induce local molecular disorder that reduces the degree of packing within the hydrogel matrix (Abdel-Aty et al., 2024). By contrast, CSG-SAPH microcapsules showed a higher melting point (87.41 °C), indicating a more thermally resilient network. This elevated thermal stability is likely related to the superior gel-forming capacity of chia seed gum and its ability to form extended hydrogen-bonded structures. The viscoelastic behavior and polysaccharide entanglement in CSG contribute to enhanced rigidity and resistance to thermal deformation (Khatoon et al., 2025). Additionally, prior studies have reported that chia seed gum remains thermally stable up to 250 °C, further confirming its suitability in high-temperature applications (Timilsena et al., 2021). In this context, the hydrogen bonding and mild electrostatic interactions in the CSG matrix, while contributing to structural resilience, form a less compact network that transitions thermally with lower energy demands (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2024).

Notably, the enthalpy of Alg-SAPH was significantly higher than that of CSG-SAPH, suggesting that more energy is required to initiate the phase transition in alginate-based systems. This can be explained by the denser ionic crosslinking between alginate chains and calcium ions, combined with the high peptide encapsulation efficiency (88.48 %) in Alg-SAPH. These factors result in a tightly bound matrix that absorbs greater energy during thermal transition. It is also plausible that the dense hydrogel architecture of Alg-SAPH contains a higher number of reversible junction zones, making the system energetically more demanding to disassemble. Additionally, the cooperative behavior between alginate and peptides—mediated by electrostatic and hydrophilic forces—may act as an entropic barrier, further increasing the thermal energy requirement (Mohamed et al., 2024).

These differences in melting points and enthalpy values suggest functional implications for controlled delivery applications. Alg-SAPH, with its lower transition temperature but higher energy absorption, may provide better retention under moderate heating conditions, making it suitable for functional food matrices or postbiotic formulations. In contrast, CSG-SAPH, due to its higher melting point and lower enthalpy, may be better suited for applications requiring heat resistance and moisture-triggered release, such as probiotic capsules or thermally processed supplements (Abdel-Aty et al., 2024; Khatoon et al., 2025).

Ultimately, these results highlight that the choice of encapsulation matrix must be tailored to the intended application. Alginate offers a compact, high-energy retention system ideal for sustained and thermally sensitive bioactives, while chia seed gum provides a flexible and temperature-resilient alternative for responsive delivery platforms.

4. Conclusion

In this study, the encapsulation of bioactive peptides derived from Sargassum angustifolium protein hydrolysate (SAPH) was investigated using two natural biopolymeric carriers: calcium alginate (Alg-SAPH) and chia seed gum (CSG-SAPH). The primary objective was to evaluate and compare the physicochemical properties, structural characteristics, and thermal stability of the resulting delivery systems. The findings demonstrated that Alg-SAPH microbeads achieved superior encapsulation efficiency (88.48 %) and greater thermal enthalpy (119.23 mJ/mg) compared to CSG-SAPH microcapsules (77.24 % EE, 72.40 mJ/mg), indicating more effective peptide retention and structural compactness. Furthermore, the more negative zeta potential of Alg-SAPH (−29.60 mV) suggested enhanced colloidal stability, while morphological analysis revealed a more rigid but irregular surface compared to the smooth and spherical morphology of CSG-SAPH. FTIR and DSC analyses confirmed the presence of specific molecular interactions in both systems, with alginate forming a denser ionic network and chia gum providing a more hydrated and thermally resistant matrix. These results collectively indicate that Alg-SAPH is more suitable for applications requiring strong entrapment and structural integrity, whereas CSG-SAPH offers potential for controlled release under hydrated or thermal stress conditions. Therefore, both encapsulation strategies show promise for improving the stability and delivery of marine-derived peptides in functional food and nutraceutical formulations. Future studies should focus on targeted delivery, in vitro digestion models, and in vivo bioavailability assessments to further tailor these systems for specific health-related applications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sara Jafarirad: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Leila Nateghi: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Masoumeh Moslemi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kian Pahlevan Afshari: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kianoush Khosravi-Darani: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Leila Nateghi, Email: nateghi@iau.ac.ir.

Kianoush Khosravi-Darani, Email: kkhosravi@sbmu.ac.ir.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abdel-Aty A.M., El-Sayed M.M., Salem W.M. Development of chia mucilage-based hydrogels for bioactive delivery: Structure–function relationship and release behavior. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;146 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.109049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akcicek A., Bozkurt F., Akgül C., Karasu S. Encapsulation of olive pomace extract in rocket seed gum and chia seed gum nanoparticles: Characterization, antioxidant activity and oxidative stability. Foods. 2021;10(8):1735. doi: 10.3390/foods10081735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand V., Vasudev S., Kumar M., Kaur C. Investigating the effect of wall material and homogenisation on chia seed oil microcapsules: SEM and stability analysis. Journal of Microencapsulation. 2024;41(1):66–78. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2023.2287396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antigo J.L.D., Stafussa A.P., de Cassia Bergamasco R., Madrona G.S. Chia seed mucilage as a potential encapsulating agent of a natural food dye. Journal of Food Engineering. 2020;285 doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2020.110101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apoorva A., Rameshbabu A.P., Dasgupta S., Dhara S., Padmavati M. Novel pH-sensitive alginate hydrogel delivery system reinforced with gum tragacanth for intestinal targeting of nutraceuticals. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;147:675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardalan Y., Jazini M., Karimi K. Sargassum angustifolium brown macroalga as a high potential substrate for alginate and ethanol production with minimal nutrient requirement. Algal Research. 2018;36:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2018.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balsters J.M., Bäumchen A., Roland M., Diebels S., Neubauer J.C., Gepp M.M., Zimmermann H. Drying of functional hydrogels: Development of a workflow for bioreactor-integrated freeze drying of protein-coated alginate microcarriers for iPS cell-based screenings. Gels. 2025;11(6):439. doi: 10.3390/gels11060439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao C., Jiang P., Chai J., Jiang Y., Li D., Bao W., Liu B., Norde W., Li Y. The delivery of sensitive food bioactive ingredients: Absorption mechanisms, influencing factors, encapsulation techniques and evaluation models. Food Research International. 2019;120:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitani M.I., Nolasco S.M., Tomás M.C. Stability of oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions with chia (Salvia hispanica L.) mucilage. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;61:537–546. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diana M.I., Selvin P.C., Selvasekarapandian S., Krishna M.V. Investigations on Na-ion conducting electrolyte based on sodium alginate biopolymer for all-solid-state sodium-ion batteries. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry. 2021;25:2009–2020. doi: 10.1007/s10008-021-04985-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forutan M., Hasani M., Hasani S., Salehi N., Sabbagh F. Liposome system for encapsulation of Spirulina platensis protein hydrolysates: Controlled-release in simulated gastrointestinal conditions, structural and functional properties. Materials. 2022;15(23):8581. doi: 10.3390/ma15238581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh K.K.T., Matia-Merino L., Chiang J.H., Quek R., Soh S.J.B., Lentle R.G. The physico-chemical properties of chia seed polysaccharide and its microgel dispersion rheology. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016;149:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarirad S., Nateghi L., Moslemi M., Pahlevan Afshari K. Functional properties of the bioactive peptides derived from Sargassum angustifolium algae. Food Measurement. 2023;17:6588–6599. doi: 10.1007/s11694-023-02161-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jafarirad S., Nateghi L., Moslemi M., Pahlevan Afshari K., Abad A.H., A., & Khosravi-Darani, K. In vitro inhibition of Streptococcus mutans by probiotic yogurt fortified with lactobacillus paracasei and Sargassum angustifolium protein hydrolysate: A functional yogurt for tooth decay prevention. Iranian Journal of Microbiology. 2025;17(3):420–433. doi: 10.18502/ijm.v17i3.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour M., Hosseini E., Nateghi L., Bazrafshan S. Enhancing margarine oxidative stability, antioxidant retention, and sensory quality via tragacanth-chitosan hydrogel microencapsulation of supercritical CO₂-extracted green coffee. Food Chemistry: X. 2025;28 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon S., Zargar S.M., Yousuf B. Advanced characterization of chia-based edible coatings: Functional group interactions and potential food applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2025;250 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.127837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed M.E., Gabr A.M.M., Sabry D.A. Improved encapsulation of marine-derived peptides using alginate-based microgels: A spectroscopic and thermal analysis. Marine Drugs. 2024;22(1):51. doi: 10.3390/md22010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M., Soltanzadeh M., Ebrahimi A.R., Hamishehkar H. Spirulina platensis protein hydrolysates: Techno-functional, nutritional and antioxidant properties. Algal Research. 2022;65 doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2022.102739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan A., McClements D.J., Udenigwe C.C. Encapsulation of bioactive whey peptides in soy lecithin-derived nanoliposomes: Influence of peptide molecular weight. Food Chemistry. 2016;213:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narsaiya M.S., Majumdar G.C. Understanding zeta potential for stability of colloidal dispersions in food and pharmaceuticals: A comprehensive review. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2022;43(1):123–135. doi: 10.1080/01932691.2020.1831279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niazi Tabar M., Nateghi L., Hashemi Ravan M., Rashidi L. Encapsulation of walnut husk and pomegranate peel extracts by alginate and chitosan-coated nanoemulsions. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2025;301 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.140349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odziomek K., Drabczyk A.K., Kościelniak P., Konieczny P., Barczewski M., Bialik-Wąs K. The role of freeze-drying as a multifunctional process in improving the properties of hydrogels for medical use. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(11):1512. doi: 10.3390/ph17111512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez C., Valencia P., Guzmán F. Structural behavior of alginate–peptide complexes: Insights from FTIR and DSC analyses. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2024;326 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Punia S., Dhull S.B. Chia seed (Salvia hispanica L.) mucilage (a heteropolysaccharide): Functional, thermal, rheological behaviour and its utilization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;140:1084–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raei M., Rajabzadeh G., Zibaei S., Jafari S.M., Sani A.M. Nano-encapsulation of isolated lactoferrin from camel milk by calcium alginate and evaluation of its release. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;79:669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheybani F., Rashidi L., Nateghi L., Yousefpour M., Mahdavi S.K. Development of ascorbyl palmitate-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) to increase the stability of Camelina oil. Food Bioscience. 2023;53 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei M., Eshaghi M., Nateghi L. Characterization of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose–whey protein concentrate bionanocomposite films reinforced by chitosan nanoparticles. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 2019;43(10) doi: 10.1111/jfpp.14158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timilsena Y.P., Wang B., Adhikari R., Adhikari B. Advances in the utilization of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) polysaccharide: A review. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;117 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vakilian K., Nateghi L., Javadi A. Advance online publication; Food Analytical Methods: 2024. Extraction and characterization of pectins from ripe grape pomace using both ultrasound-assisted and conventional techniques. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Yu Z., Lin K., Sun C., Dai L., Yang S., Mao L., Yuan F., Gao Y. Fabrication and characterization of resveratrol-loaded zein-propylene glycol alginate-rhamnolipid composite nanoparticles. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;95:336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.