Abstract

Background

Array-based DNA methylation profiling is the gold standard for central nervous system (CNS) tumor molecular classification, but requires over 100 ng input DNA from surgical tissue. Cell-free tumor DNA (cfDNA) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) offers an alternative for diagnosis and disease monitoring. This study aimed to test the utilization of enzymatic DNA methylation sequencing (EM-seq) methods to overcome input DNA limitations.

Methods

We used the NEBNext EM-seq v2 kit on various amounts of cfDNA, as low as 0.1 ng, extracted from archival CSF samples of 10 patients with CNS tumors. Tumor classification was performed via MNP-Flex using CpG sites overlapping those on the MethylationEPIC array.

Results

EM-seq provided sufficient genomic coverage for 10 and 1 ng input DNA samples to generate global DNA methylation profiles. Samples with 0.1 ng input showed lower coverage due to read duplication. Methylation levels for CpG sites with at least 5× coverage were highly correlated across various input DNA amounts, indicating that lower input cfDNA can still be used for tumor classification. The MNP-Flex classifier, trained on tissue DNA methylation data, successfully predicted CNS tumor types for 7 out of 10 CSF samples using EM-seq methylation data with only 1 ng of input cfDNA, consistent with diagnoses based on tissue MethylationEPIC classification and/or histopathology. Additionally, we detected focal and arm-level copy number alterations previously identified via clinical cytogenetics of tumor tissue.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of CNS tumor molecular classification based on CSF using the EM-seq approach, and establishes potential sample quality limitations for future studies.

Keywords: cell-free DNA, CNS tumor classification, MNP-flex, enzymatic methylation sequencing, molecular diagnosis

Key Points.

EM-seq can profile methylation of cell-free DNA from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using 1–10 ng of DNA input.

DNA methylation profiles from the CSF were able to successfully classify 70% of tested samples.

Copy number variations can be detected by EM-seq for treatment response/disease monitoring.

Importance of the Study.

Obtaining adequate biopsy of central nervous system (CNS) tumors for diagnosis, particularly in pediatric populations, can be challenging without significant morbidity and sampling bias in the case of mixed tumors. Liquid biopsy of CNS tumors may provide a supplemental or alternative method of obtaining tumor diagnosis, and its limited invasiveness provides the potential to acquire additional useful disease-monitoring information during and after treatment. Given that the current gold standard for molecular classification of CNS tumors is based on DNA methylation profiling of tumor tissue, we sought to demonstrate the feasibility of using cell-free DNA from CSF for methylation profiling. To achieve this, we combined enzymatic methylation sequencing to achieve sufficient coverage for DNA methylation profiling, and a methylation-platform-agnostic classifier, MNP-Flex. We tested multiple input DNA amounts and established potential sample quality limits for accurate classification. These results represent important preliminary steps towards establishing DNA methylation profiling of the CSF for CNS tumor diagnosis.

Molecular diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) tumors has rapidly advanced in the last few years, with tumor classification based on genome-wide DNA methylation profiling emerging as the gold standard for molecular classification.1,2 The “Molecular Neuro-Pathology” (MNP) DNA methylation-based tumor classification algorithm, developed by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), has been adapted widely for clinical diagnosis. This platform has been trained and designed for use with DNA methylation data generated by the Illumina HumanMethylation450 and MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarrays (hereafter, “MethylationEPIC”) from tumor tissue. However, sufficient tumor sample from biopsy can be difficult to obtain for many tumor types, particularly within pediatric populations, due to surgically challenging tumor locations (ie, deep in the brain) and intratumoral heterogenicity, limiting the utility of the current approach to DNA methylation analysis of tumor tissue. Additionally, repeated biopsy of the tumor is often not practical for the molecular monitoring of a tumor’s response to ongoing treatment.

Compared to conventional tissue biopsies, liquid biopsies have become an attractive alternative for DNA methylation-based tumor diagnosis. Liquid biopsies have multiple advantages over conventional tissue biopsy, including (1) minimally invasive sampling procedure; (2) potentially less sampling bias for heterogeneous tumors; and (3) potential use for longitudinal monitoring of disease progression and treatment response.3–5 The majority of liquid biopsy assays have been developed using plasma or serum. More recently, groups have explored the possibility of using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), partly because it offers promising advantages for diagnosing CNS tumors, including glioma, ependymoma, and medulloblastoma.6–12 First, studies have shown that patients with CNS tumors harbor more cell-free tumor DNA in the CSF than in plasma—likely due to the presence of the blood–brain barrier13–15—suggesting that more informative molecular profiling can be performed on CSF samples. Second, CSF is akin to an ultrafiltrate and has fewer potential contaminants and lower background cellularity that could interfere with clinical assays as compared to plasma.16,17 Third, since CSF sampling is a routine procedure in the management of many types of CNS tumors, no additional procedure would be required for developing new clinical assays. Despite these advantages, molecular analysis of CSF has yet to be widely adopted for clinical diagnosis of CNS tumors or tumor monitoring, mostly due to the limited quantity of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) obtained from CSF samples.

DNA methylation array data is the standard input for the current MNP classifier. However, the minimal DNA input amount (200 ng, as recommended by the manufacturer) is the biggest challenge for CSF samples, as published studies usually report obtaining less than 50 ng of cfDNA from 200 to 500 mL CSF.6,12,14 Recently, Nanopore sequencing to detect DNA methylation status, followed by classification using a novel method (NanoDx), has been reported using as low as 3–5 ng of cfDNA from CSF. Among 129 samples, the classification success rate is 17.1% (n = 22) with NanoDx alone and 38.8% (n = 50) when combined with copy number variant (CNV) analysis.18 A more accurate approach with lower DNA input requirements is needed to move forward with CSF-based tumor classification development.

Enzymatic DNA methylation sequencing (EM-seq) technology has recently been developed, which detects 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) using a 2-step enzymatic reaction19 instead of bisulfite conversion. In the first step, 2 enzymes work in parallel to protect the methylated and hydroxymethylated cytosines. Ten-eleven translocation 2 (TET2) methylcytosine dioxygenase oxidizes 5mC and 5hmC, and T4-phage beta-glucosyltransferase (T4-BGT) glucosylates 5hmC on DNA into products that cannot be deaminated in the second step. Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit 3A (APOBEC3A) is used in the second step to convert unmodified cytosines into uracils by deamination.19 The resultant DNA is then sequenced using an Illumina system. Due to the mild reaction conditions of EM-seq, a lower amount of DNA input is needed, compared to conventional bisulfite sequencing, making EM-seq a potential alternative technology for analyzing CSF samples. However, whether EM-seq technology can be used for CSF with a low cfDNA amount has not been reported.

To address this, in this feasibility study, we sought to test the performance of cfDNA methylation profiling on 10 CSF samples using a new version of the EM-seq kit developed by New England Biolabs (NEB), which is optimized for DNA input as low as 0.1 ng. We first tested the performance of the kit for EM-seq analysis, followed by tumor classification with varying DNA input, using 2 high-quality CSF samples. We then went on to further evaluate the performance of the technology by analyzing 8 additional samples with varying cfDNA quality to examine the limits of the system.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples

Deidentified archival CSF samples were obtained from the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center (Connecticut Children’s) biorepository and the Children’s Brain Tumor Network (CBTN) biorepository. The study was approved by both Connecticut Children’s and The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) Institutional Review Boards. CSF samples were centrifuged for 10 min at a minimum of 400 g to remove cells, and supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C prior to extraction.

Cell-Free DNA Extraction

Cell-free DNA was extracted from 500 to 1000 mL CSF using Quick-cfDNA Serum & Plasma Kit (Zymo Research) or QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturers’ protocols. The resultant cfDNA was quantified by DNA high-sensitivity (HS) Qubit assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Cell-free DNA ScreenTape assay (Agilent Technologies).

Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation was performed using NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit v2 kit and Unique Dual Index Primer pairs (NEB) according to manufacturer’s protocol, without DNA fragmentation due to the small size of the cfDNA. Sheared unmethylated lambda DNA and methylated pUC19 DNA were added to each cfDNA sample as negative and positive controls, respectively. Control DNA (1:500) was used for the 0.1 ng input samples, while 1:50 control DNA was used for 1 and 10 ng samples. A total of 14, 11, and 8 amplification cycles were used for 0.1, 1, and >1 ng of DNA input, respectively. Libraries were stored at −20°C prior to sequencing. Library fragment size profiles were checked using High Sensitivity DNA ScreenTape D5000 on Agilent TapeStation 4200 system (Agilent). Quantification of libraries was performed using real-time qPCR ViiA7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with probes targeting the Illumina sequencing adaptor. The expected average size of DNA fragments was about 350–370 bp, which is equal to the sum of cfDNA and Illumina sequencing adaptors. Sequencing was performed on Illumina Novaseq X Plus platform, generating paired-end reads of 150 bp.

Tumor Classification Using DKFZ’s MNP-Flex Classifier

DNA methylation sequencing data was processed using the nf-core/methylseq20 Nextflow pipeline (version 2.4.0, https://nf-co.re/methylseq/2.4.0) for quality control, adapter trimming, mapping, deduplication, and site-specific methylation calling (options: -profile “singularity,” --aligner “bismark,” --genome “GRCh38,” --em_seq). The resulting coverage (.cov.gz) files from bismark21 (version 0.24.0) were used to calculate beta values, which were subsetted to only include CpG sites overlapping with the Infinium MethylationEPIC array probe sites using bedtools22 (version 2.26.0) “intersect” function. Subsequently, coverage was calculated from the total number of methylated and unmethylated reads corresponding to each site, prior to classification using the platform-agnostic MNP-Flex classifier (as well as the prior MNPv12.8 classifier, using beta values of CpG sites corresponding to the MethylationEPIC array probe sites with missing values imputed using KNNimpute).2,23,24

Detection of Tumor-Specific Copy Number Variants Using cfDNA

Mapped, deduplicated reads from the methylseq pipeline were used for copy number variation analysis using CNVpytor (https://github.com/abyzovlab/CNVpytor),25 which calculates CNVs using normalized sequencing read depth. Relevant genes were identified for each sample using patient-specific primary tumor CNVs called by clinical cytogenetics (Supplementary Table 1), where available. Plots were made using different read binning sizes (1k bp, 10k bp, or 100k bp) depending on the size of the gene body.

Validation of Known CNVs Using Droplet Digital Polymerase Chain Reaction

cfDNA was extracted with the Quick-cfDNA Serum & Plasma Kit (Zymo). Reaction mix, including 7.8 mL of cfDNA, 11 mL of Supermix for probes (No dUTP) (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 1.1 mL 20× target primer/probe (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 1.1 mL 20× reference primer/probe (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and 5 U of the appropriate restriction enzyme (NEB), was added to each well of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) plate. The 96-well plate was then heat sealed and run on the Automated Droplet Generator with Droplet Generation Oil for Probes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) following manufacturer’s instructions. After droplet generation, the new 96-well plate was heat sealed for PCR (10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, and 60°C for 1 min, then 98°C for 10 min and cooling to 4°C). Droplets, after cycling, were analyzed using the QX200 Droplet Reader and the QuantaSoft software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Copy number was calculated by the instrument software with the target gene copies normalized to the reference gene RPP30.

Results:

Extraction and EM-seq Analysis With Various DNA Input Amounts of cfDNA From CSF

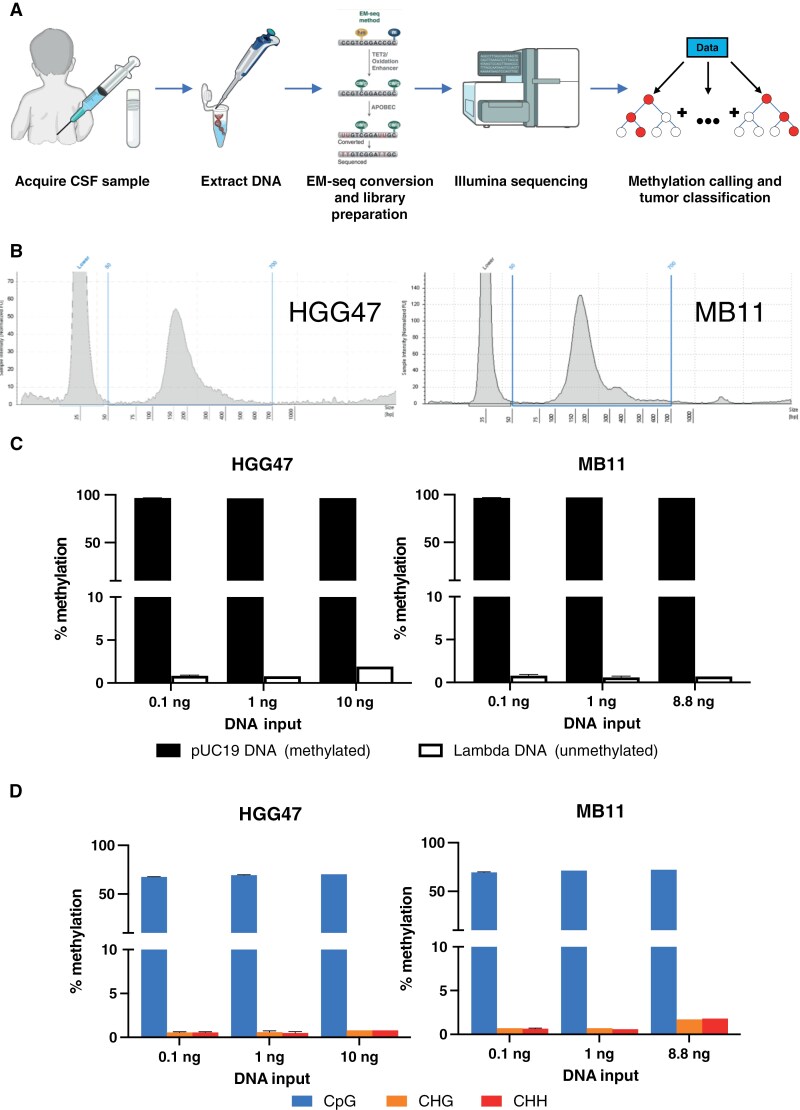

As a recent development of the EM-seq technology, a new version of NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit was developed for low DNA input as low as 0.1 ng. To test if EM-seq analysis on cfDNA extracted from CSF samples can be used for tumor classification, we extracted cfDNA from archival CSF samples and performed EM-seq. The schematic diagram of the workflow is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Overview of EM-seq analysis of CSF samples. (A) Schematic workflow of CSF sample preparation, sequencing, and analysis. Prepared using the NIAID NIH BIOART Source (https://bioart.niaid.nih.gov/). (B) DNA fragment size profile of extracted cfDNA from HGG47 and MB11 samples by TapeStation. Vertical blue lines represent the size range of cfDNA within the CSF (50–700 bp). (C) Average methylation values for spike-in controls for varying input DNA amounts in both HGG47 and MB11 samples. pUC19 (methylated) control shown in black, lambda (unmethylated) DNA shown in white. (D) Average methylation values for different cytosine contexts (CpG, CHG, CHH) for varying input DNA amounts in both HGG47 and MB11 samples.

To test the performance of the EM-seq kit with varying inputs of DNA, we obtained 2 deidentified archival CSF samples from Connecticut Children’s biorepository. The 2 samples chosen had detailed histopathology reports and DNA methylation classification using the MNP v12 classifier based on tumor tissue DNA. The first sample (HGG47) is from an 11-year-old female patient diagnosed with pediatric-type high-grade glioma with wildtype H3 and IDH. The second sample (MB11) is from a 7-year-old female patient diagnosed with classic variant medulloblastoma, WHO grade 4, non-WNT/non-SHH subtype with wildtype TP53. cfDNA was extracted from 1000 and 500 mL of CSF of HGG47 and MB11, respectively. The yield of total DNA, as measured by DNA HS Qubit assay, was 13.50 ng (HGG47) and 10.17 ng (MB11). The cell-free DNA ScreenTape assay showed that the average size of the cfDNA (ie, 50–700 bp) was 203 bp and 212 bp for HGG47 and MB11, respectively, and no appreciable high molecular mass DNA (>700 bp) contamination was found for either sample (Figure 1B).

Next, we performed EM-seq conversion and library preparation using the EM-seq v2 kit according to manufacturer’s protocols. To test the performance of EM-seq with various DNA input amounts, EM-seq libraries with 3 different amounts of cfDNA were made for each sample (Table 1). Library preparation metrics across all input DNA amounts and technical replicates, including library yield and fragment size, are shown in Table 1. In general, higher DNA input generated higher yield, with similar fragment lengths across all input amounts of cfDNA. All library preparations generated enough materials for Illumina sequencing.

Table 1.

Library preparation and sequencing metrics of EM-seq libraries.

| Case ID | Time of CSF acquisition | DNA input (ng) | Library yield measured by qPCR (nM) | Average size of library fragment (bp) | Percent Mapped | Mapped reads (millions) | Percent duplicated | Mean genomic coverage (X) |

| HGG47 | Pre-treatment | 10 | 23.38 | 346 | 89.3 | 603 | 9.8 | 43.3 |

| 1 | 7.15 | 377 | 88.2 | 541 | 43.1 | 24.6 | ||

| 8.26 | 359 | 88.8 | 624 | 45.4 | 27.2 | |||

| 0.1 | 6.11 | 352 | 82.5 | 976 | 95.4 | 3.5 | ||

| 6.94 | 365 | 83.9 | 1006 | 96.2 | 3.1 | |||

| MB11 | Pre-treatment | 8.8 | 8.09 | 379 | 85.4 | 794 | 15.3 | 53.8 |

| 1 | 9.08 | 352 | 84.2 | 919 | 43.2 | 40.2 | ||

| 0.1 | 8.52 | 331 | 84.4 | 1005 | 87.1 | 10.2 | ||

| 7.3 | 372 | 84 | 985 | 89.2 | 8.4 |

Sequencing was performed using the Illumina Novaseq X Plus platform, generating paired-end reads of 150 bp. Overall, the sequencing analysis generated an average of 828 mappable million reads per sample (ranging from 541 to 1006 million reads per sample) with an average 85.6% (standard deviation [SD] = 2.5%) of reads mappable to the human genome (Table 1). The percentages of duplicated reads are low at 9.8% and 15.3% for 10 ng (HGG47) and 8.8 ng (MB11) libraries, respectively. However, the percentages of duplicated reads increased with decreasing DNA input. For example, the average percentages of duplicated reads of 0.1 ng libraries are 92.0% (SD = 4.5%). Mean genomic coverage was impacted by this variation in duplicated reads, the mean genomic coverage of the 10 ng (HGG47) and 8.8 ng (MB11) libraries at 43.3’ and 53.8’, respectively. In contrast, 0.1 ng libraries only achieved a mean genomic coverage of 6.3’ (SD = 3.5’) due to their high level of duplication.

To examine the efficiency of the EM-seq conversion, sheared unmethylated lambda DNA and methylated pUC19 DNA were added to each sample according to manufacturer’s protocols. Oxidation of 5mC and 5hmC by TET2 and the glucosylation of 5hmC by T4-BGT protected the products from deamination by APOBEC3A and, as a result, only unmethylated cytosines will be deaminated to uracil. A high percentage of methylation found on methylated pUC19 DNA and a low percentage of methylation found on unmethylated lambda DNA indicated an efficient EM-seq conversion. The overall percentage of methylation on methylated pUC19 DNA and unmethylated Lambda DNA is 96.8% ± 0.2% (mean ± SD) and 0.9% ± 0.4%, respectively (Figure 1C). We also examined methylation of cytosines in different genomic contexts, as methylation of cytosines is largely exclusive to CpG dinucleotides in mammalian cells, and should be very low in other genomic contexts (CHG or CHH, where H represents A, C, or T nucleotides).26 The average methylation in the CpG context was detected at 69.7% ± 1.6%. As expected, the percentages of methylation in the CHG and CHH sites were low, ranging from 0.4% to 1.8% (Figure 1D). No significant difference in DNA methylation within a genomic context was observed across the various DNA inputs. The results indicated a high efficiency of expected EM-seq conversion, and that the data could be used for downstream analysis.

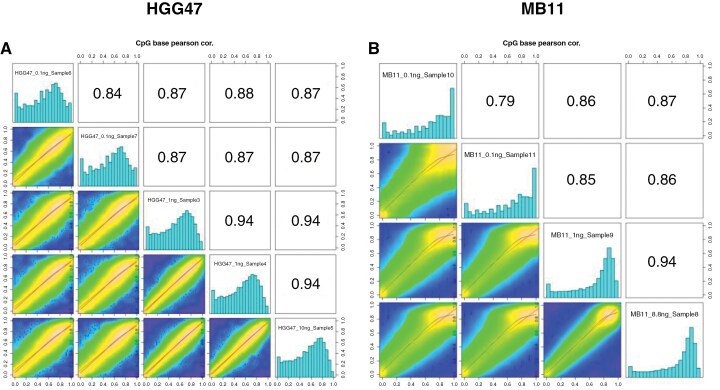

To further evaluate the consistency of results from sequencing, we compared the methylation values of CpG sites using different amounts of cfDNA. The correlation between methylation values of CpG sites with at least 10× coverage across all input cfDNA sequencing runs within a single sample (either HGG47 or MB11) is shown in Figure 2. As 1 and 10 ng inputs allowed for higher coverage due to lower duplication rates, the methylation values within those data are highly correlated (Pearson r = 0.94). More marginal coverage in the 0.1 ng input DNA data results in lower correlation with the methylation levels determined from high-input sample runs, although overall there is still high correlation in sites that have at least 10’ coverage across input amounts (Pearson r ≥ 0.85). This effect is more pronounced with equivalent plots using a 5’ coverage cutoff (Supplementary Figure 1), where the DNA methylation correlation in the higher input 1 and 10 ng sequencing runs is markedly higher than with the 0.1 ng samples. This indicates that overall, DNA methylation sequencing data obtained from the 0.1 ng samples are reliable, but due to high levels of read duplication, insufficient average coverage limits its utility for tumor classification using a genome-wide approach.

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation between methylation values of CpG sites with at least 10× coverage across all input cfDNA values for (A) HGG47 and (B) MB11.

Tumor DNA Methylation Classification Using Data Generated From EM-seq

Beta values were calculated for each CpG site from the ratio of methylated to total reads. This beta value matrix was limited to sites overlapping with the MethylationEPIC array probes used for classification by the MNP-Flex classifier2,23 and used as an input to the classifier in order to predict CNS tumor types for each sample at the superfamily, family, class, and subclass level. MNP-Flex was developed using the most updated training dataset and serves as a platform-agnostic method for CNS tumor classification that accepts DNA methylation sequencing data.

Tumor classification results with prediction scores of HGG47 and MB11 using CSF cfDNA are shown in Table 2, along with the gold-standard, array-based classification performed using the MethylationEPIC array with tumor tissue. For the HGG47 sample, classifications were consistent at all levels across different DNA input amounts, including superfamily (pediatric-type diffuse high-grade glioma), family (H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype), class (subtype A&B (novel)), and subclass (subtype B). The prediction scores decreased as the cfDNA input decreased, likely due to a reduction in coverage as input cfDNA decreased. Compared to the classification by tissue, the result from CSF agreed with that from tissue, except at the subclass level, where the tissue classified the sample as “subtype A” with high confidence. The prediction scores of classifications by CSF were marginal at the subclass level, and when using 0.1 ng of input cfDNA. We noted that, using the MNP v12.8 classifier with imputed missing values (KNNimpute24), the classification of this sample was correct to the subclass level, with high confidence (10 ng input, classification score = 0.99, Supplementary Table 2). In addition, the cfDNA methylation-based classification result is consistent with the histopathological diagnosis of the tumor as a pediatric-type high-grade glioma with wildtype H3 and IDH.

Table 2.

Tumor classification based on CSF (MNP-Flex) and tissue (MNP v.12) of HGG47 and MB11, across varied amounts of input cfDNA from CSF.

| Case ID | Sample type | DNA input (ng) | Methylation superfamily | Methylation family | Methylation class | Methylation subclass |

| HGG47 | CSF | 10.0 | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.628] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.614] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.566] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype B [0.336] |

| HGG47 | CSF | 1.0 | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.503] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.488] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.436] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype B [0.227] |

| HGG47 | CSF | 1.0 | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.465] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.447] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.372] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype B [0.212] |

| HGG47 | CSF | 0.1 | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.290] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.267] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.194] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype B [0.165] |

| HGG47 | CSF | 0.1 | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.219] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.182] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.114] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype B [0.090] |

| HGG47 | Tissue | N/A | Pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas [0.999] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3-wildtype and IDH-wildtype [0.999] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A&B (novel) [0.999] | Diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma, H3 wildtype and IDH wild type, Subtype A [0.930] |

| MB11 | CSF | 8.8 | Medulloblastoma [0.996] | medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.996] | medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.996] | Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass VIII [0.995] |

| MB11 | CSF | 1.0 | Medulloblastoma [0.997] | medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.997] | medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.996] | Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass VIII [0.996] |

| MB11 | CSF | 0.1 | Medulloblastoma [0.960] | medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.958] | medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.956] | Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass VIII [0.951] |

| MB11 | CSF | 0.1 | Medulloblastoma [0.888] | medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.883] | medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.876] | Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass VIII [0.866] |

| MB11 | Tissue | N/A | Medulloblastoma [0.999] | Medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.999] | Medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.999] | Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass VIII [0.999] |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MNP, Molecular Neuro-Pathology.

Prediction score by MNP shown in brackets.

For MB11, CSF cfDNA classification shows superfamily: “medulloblastoma” family: “non-WNT/non-SHH activated subtype” class: “group 4” and subclass: “group 4, subclass VIII” (Table 2). The classifications were constant at all levels across different DNA input amounts. The prediction scores decreased slightly from 0.995 for 8.8 ng input to 0.866–0.951 for 0.1 ng input at the subclass level. Compared to the tumor classification by tissue, the results from CSF classification agreed at all levels with high confidence. The DNA methylation-based classification was also consistent with the histopathological report of the tumor as a non-WNT/non-SHH subtype medulloblastoma.

Taken together, based on these 2 samples, we demonstrated that EM-seq analysis (using NEBNext EM-seq kit v2) of CSF cfDNA down to 1 ng captures the tumor methylation profile. The generated data resulted in correct tumor classification by CSF using the MNP-Flex algorithm, with only minor discrepancies at the subclass level for HGG47, compared to the DNA methylation-based classification by tissue and the histopathological reports.

EM-seq Analysis of Additional CSF Samples of CNS Tumor Samples

A large variation in quantity and quality of cfDNA extracted from CSF was observed by us and by other groups previously.6,12,14 The 2 samples with successful classification described above had high-quality cfDNA. To test the feasibility of EM-seq analysis using CSF cfDNA with varied quality and cfDNA concentration, we used an additional eight CSF samples: 3 medulloblastoma, 1 pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, 1 germinoma, and 2 atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT). The cfDNA was extracted and measured by both DNA HS Qubit and Cell-free DNA ScreenTape assays following the same protocol used for the previous samples. The yield of cfDNA extraction by Qubit and determination of DNA size content by ScreenTape are listed in Supplementary Table 3. MB26, MB32, and G05 were included because of a low cfDNA yield extracted from CSF. The cfDNA yield of MB26 was 3.78 ng, while the yields of MB32 and G05 were too low to be detected by Qubit assay. In contrast, although high DNA yield was obtained for the samples ATRT30, ATRT52c, MB45, and HGG49, additional peaks were detected in the fragment size profiles. Both ATRT samples, as well as MB45 and HGG49, had fragment peaks at ~200 bp (ie, cfDNA) and additional peaks between 400 and 700 bp. ATRT30 and ATRT52c also had evidence of cellular DNA contamination, with peaks >700 bp. Finally, MB51 was included because it was a low-yield sample without any visible peak in the fragment size profiles. The TapeStation fragment size profiles of all samples are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Since 1 ng DNA input for EM-seq analysis generated data for correct tumor classification with prediction scores >0.5 in the first 2 samples, which is considered “suggestive” by the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative’s Molecular Characterization Initiative, the EM-seq conversion and library preparation of 8 additional selected samples were performed as previously described with 1 ng DNA input, except MB32 and G05. The maximum volume allowable for EM-seq library preparation (45 mL) was used for MB32 and G05 samples, which were equal to 1.22 and 1.50 ng, respectively, based on the ScreenTape analysis result. Post-library preparation QC was done, showing that the EM-seq libraries yield ranged from 0.72 to 13.42 nM. The sequencing metrics of the 8 libraries are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

The EM-seq data were subjected to DNA methylation-based classification using MNP-Flex, and the results are shown in Table 3 (with MNP12.8 results shown in Supplementary Table 5). The classification by cfDNA methylation was compared to the methylation classification of the tissue, where available, or the histopathologic diagnosis (images shown in Supplementary Figure 3). Among low-yield samples, all 3 samples (MB26, MB32, and G05) are correctly classified (scores = 0.961, 0.791, 0.914, respectively) at the family level. Unfortunately, we cannot confirm the class and subclass of these samples due to lack of DNA methylation-based classification by tissue. The score for MB32 at the class and subclass levels was more marginal. Based on the histopathological report of MB32, this is a recurrent medulloblastoma with more diffused severe anaplasia (>50%), comparing to the initial diagnosis, suggesting that this recurrent tumor may be altered from the original tumor and may not fit cleanly into existing tumor classes and subclasses. Both ATRT tumors were classified correctly, with classifications down to the subclass level, which match the classification based on tissue using MNP v12 classifier.

Table 3.

Comparison between histopathological/tissue methylation-based diagnosis and tumor classification by EM-seq analysis using CSF.

| Case ID | Tissue diagnosis source | Tissue diagnosis | Predicted classification by CSF methylation |

| MB26 | Tissue methylation (MNP v12) | Medulloblastoma [0.996] Medulloblastoma non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.996] Medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.963] Medulloblastoma Group 4, subclass V [0.909] |

Medulloblastoma [0.963] Medulloblastoma, non-WNT/non-SHH activated [0.961] Medulloblastoma Group 4 [0.941] Medulloblastoma Group 4, Subclass V [0.919] |

| MB32 | Tissue methylation (MNP v12) | Medulloblastoma [0.999] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated [0.999] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 3 [0.704] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 3 [0.704] |

Medulloblastoma [0.805] Medulloblastoma, SHH activated [0.791] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 4 [0.425] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 4 [0.425] |

| G05 | Histopathology | Germinoma KIT+, OCT4+, CD117+ PLAP- |

Germ cell tumors [0.914] Germ cell tumors of the CNS [0.914] Germinoma [0.914] Germinoma, subtype KIT mutant (novel) [0.913] |

| ATRT30 | Tissue methylation (MNP v12) | Other CNS embryonal tumors [0.942] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor [0.937] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, MYC activated [0.877] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, MYC activated [0.877] |

Other CNS embryonal tumors [0.671] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor [0.651] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, MYC activated [0.582] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, MYC activated [0.582] |

| ATRT52c | Tissue methylation (MNP v12) | Other CNS embryonal tumors [1.000] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor [1.000] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, SHH activated [0.995] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, SHH activated [0.995] |

Other CNS embryonal tumors [0.904] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor [0.897] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, SHH activated [0.885] Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, SHH activated [0.885] |

| MB45 | Tissue methylation (MNP v12) | Medulloblastoma [0.998] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated [0.998] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 1 [0.655] Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated, subtype 1 [0.655] |

Low-grade glial/glioneuronal/neuroepithelial tumors [0.122] Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [0.061] Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [0.061] Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [0.061] |

| HGG49 | Histopathology/tissue methylation (MNP v12) | High-grade glioma H-3 wildtype, IDH-wildtype, BRAF V600E mutation, homozygous CDKN2A deletion Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (methylation) |

Low-grade glial/glioneural/neuroepithelial tumors [0.140] Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma(-like) [0.088] Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma(-like) [0.088] Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [0.088] |

| MB51 | Tissue methylation (St. Jude classifier) | Methylation family: Medulloblastoma Group 3/4 [0.99] Methylation class: Medulloblastoma Group 3/4, subgroup 8 [0.99] |

Ependymal tumors [0.102] Meningioma [0.0987] Meningioma, benign [0.083] Meningioma, subclass benign 1 [0.055] |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MNP, Molecular Neuro-Pathology.

Methylation classification results reported for (in order): superfamily, family, class, and subclass. Prediction score by MNP shown in brackets.

The remaining samples, MB45, HGG49, and MB51, were classified with low prediction scores (<0.49), which indicates the tumor type cannot be determined. MB45 represents a tumor with a difficult original diagnosis, presenting with 2 separate tumors which were diagnosed at the same time, with 1 tumor found in the posterior fossa and the other in the pineal region. The unusual nature of this tumor may have complicated the cfDNA profile as compared to the tissue, as it may represent a mixture of DNA from both tumor sites. HGG49 tissue classified as a pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, which is a rare subtype of astrocytic glioma. Although diagnosis based on cfDNA using MNP-Flex was correct, the score was extremely low at all classification levels. Finally, we found no visible cfDNA peak on the TapeStation profile of MB51, which likely prevented us from obtaining any classification.

Taken together with HGG47 and MB11, we successfully performed EM-seq and MNP-Flex classification on ten CSF samples with different CNS tumor diagnosis. Seven out of 10 (70%) samples showed correct classification by the MNP-Flex algorithm. Our present study demonstrates the feasibility of tumor classification based on 1 ng of cfDNA extracted from CSF using EM-seq technology.

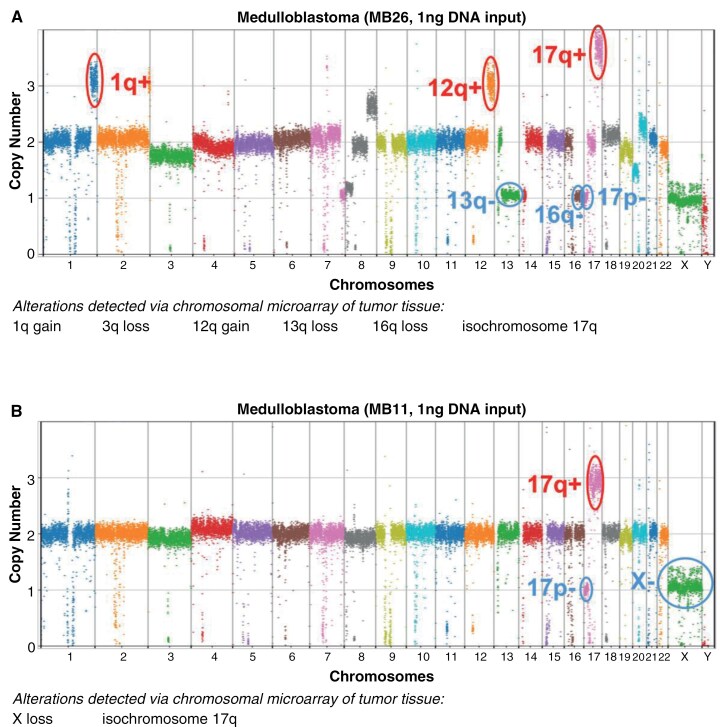

Copy Number Variation Detectable in CSF cfDNA Reveals Tumor-Specific Alterations

The MethylationEPIC array data are utilized not only for elucidating genome-wide DNA methylation patterns but also for estimating chromosomal copy number changes. This dual application enhances our understanding of tumors at different molecular levels, thereby facilitating diagnoses and disease monitoring. To evaluate whether similar copy number estimations can be achieved using EM-seq data, we investigated the detectability of CNVs in CSF cfDNA found in the original tumor tissue. We utilized CNVpytor to determine copy number using normalized read depth.25 Chromosomal arm-level copy number alterations were determined for each sample, and compared with those originally found within the tumor tissue using CNV microarray assay (OncoScan, Affymetrix),27 where available. Two illustrative examples are shown in Figure 3, with 5/6 (MB26, Figure 3A) and 2/2 (MB11, Figure 3B) chromosomal arm-level copy number alterations detectable in tumor tissue also found within the CSF. With MB26, there was a suggestion of 3q loss even though the results did not reach statistical significance. In additional samples, by reducing the read depth binning to 10k bp, we were also able to detect more focal alterations that were previously found in the original tumor tissue, including deletions of CDKN2A/B in HGG49 and deletions of TP53, RB, and SMAD4 in HGG47 (Supplementary Figure 4). Copy number alterations detected using bins of 1k bp–100k bp for all tested samples can be found in Supplementary Table 6, with genome-wide copy number plots of all samples in Supplementary Figure 5. Interestingly, the large-scale copy number alterations found in tissue for MB51, which was not classified correctly using CSF, were also not present in the copy number profile. This provides further evidence that insufficient tumor DNA was available in the CSF to perform classification. For the other misclassified samples, HGG49 and MB45, either no copy number data were available (HGG49), or copy number alterations were either not found in 1 of the 2 tumors from that patient (MB45), limiting our ability to explore this further.

Figure 3.

Arm-level copy number alterations detected in cfDNA from CSF. Copy number calculated from read depth across 100kbp bins using CNVpytor. For each sample, (A) MB26 and (B) MB11, arm-level copy number alterations listed were detected via tumor chromosomal microarray of the tumor tissue taken at the same time point as the CSF collection and listed in the cytogenetics report for that case. Arm-level copy number gains (red) and losses (blue) corresponding to the those detected in tissue are circled for each sample.

Discussion:

Correct diagnosis, including subclassification, of CNS tumors is crucial to accurately stratify patients for accurate prognosis and therapy in order to optimize patient outcomes. Imaging of the tumor and histopathological analysis of surgical biopsies have been the most common practices for diagnosis for many decades. However, these methods alone could lead to potentially inconclusive diagnosis, particularly if there is limited tumor sample for evaluation. In 2018, Capper et al. reported that DNA methylation analysis from tumor tissue could be used for tumor classification and improving the diagnosis for pediatric and adult CNS tumors.2 Since then, tissue DNA methylation classification has become a gold standard for CNS tumor molecular diagnosis and has been incorporated into the new WHO classification CNS5 for some pediatric CNS tumors.28 However, in some CNS tumor cases, sufficient tissue biopsy for classification is not feasible due to inability to obtain adequate tumor tissue, related to tumor size and/or close proximity to vital brain structures. In these situations, liquid biopsy becomes an attractive alternative approach for diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring of disease. In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of using EM-seq analysis for tumor classification with as low as 1 ng of input cfDNA extracted from CSF samples.

For tumor classification, data of 10 ng samples with mean genomic coverage of 43.3’ and 53.8’ resulted in correct classification for both high-grade glioma and medulloblastoma. Although the mean genomic coverage decreased to 24.6 and 40.2’ in the 1 ng samples, correct classification was still achievable. The current version of MNP-Flex relies on 100 000 variant CpG sites. The number of sites with no coverage is small, representing under 1% of the data. So, the absolute degree of missing data is low, and the effect on the classification should be minimal. However, 0.1 ng samples with lower mean genomic coverage (3.1–10.2’) resulted in lower overall prediction scores. To address this limitation in the future, a targeted sequencing approach to increase coverage of relevant CpG sites may be explored, which could increase the possibility of using extremely low-input cfDNA for classification.

In addition, in the test of low-quality and/or low-yield cfDNA samples, correct tumor classification was found with 7/10 samples. For the 3 samples with poor results, there were additional factors that affected classification. As discussed previously, for 1 sample (MB45), the cfDNA within the CSF may have been a mixture from 2 tumors in the same patient, unusual presentation for this tumor type as 1 tumor arose in the pineal region. Although both of these tumors had the same tissue DNA methylation-based molecular diagnosis, they presented with different copy number alterations using the same assay. For another (HGG49), despite correct classification with high confidence using the tissue, the CSF classification had an extremely low score. Without copy number alterations detected in the original tumor by clinical array, we are unsure if sufficient tumor cfDNA was present to make a diagnosis. An additional sample with poor classification (MB51) had no visible cfDNA peak and was unable to be classified. We noted that this sample was classified with a low score as an ependymal tumor. This finding may suggest that the input DNA predominantly came from choroid plexus cells of ependymal origin, another potential source of nontumor DNA due to their role in the brain–CSF interface. Our results suggest that high-quality cfDNA, including the presence of monomeric and dimeric cfDNA (200–400 bp), is critical for correct tumor classification. Whether the observation is generalizable to additional tumor types should be investigated in future studies.

As a feasibility study, we aimed to demonstrate the success of EM-seq analysis using cfDNA extracted from CSF. We recognize some limitations of this study to confirm that EM-seq analysis on CSF can be used for classification of a broad range of CNS tumor types. First, the number of samples and tumor types used in this study is too small to reach any sort of comparative statistical power to the tissue-based classifier. To address this, a larger cohort study, including a variety of CNS tumor diagnoses, is currently being planned. Second, no classification algorithm trained on CSF cfDNA methylation data is available. The current classification algorithm has been developed based on the MethylationEPIC data generated from tissue. Whether this contributed to a lower prediction score for some samples is uncertain. A pairwise comparison between classification by tissue and CSF across a panel of CNS tumor types should be performed to determine whether the current classification algorithm for tissue is robust enough for data from cfDNA extracted from CSF, or if a CSF-specific algorithm is required to correctly classify tumor types. Third, the CSF samples used in this study are archival materials from various biorepositories. The collection method and handling process were not strictly controlled and standardized. A prior study using a panel-based sequencing approach in a large cohort found a significant decrease in detectable cfDNA when less than 2 mL of CSF was used for extraction.29 A prospective study with controlled CSF volumes may allow us to determine the detection limit relevant to genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. Whether the difference in collection methods and handling processes contributes to any variation in our results has to be investigated in a larger cohort study.

Currently, cfDNA extracted from plasma is another attractive liquid biopsy analyte being explored for disease detection, classification, and longitudinal monitoring. However, CSF is an ultrafiltered body fluid as compared to plasma, and likely has a higher signal-to-noise ratio for tumor analytes as compared to plasma. In addition, it has been previously reported that the nucleic acids extracted from CSF are higher in concentration than those from plasma for patients with CNS tumors, likely due to the presence of blood–brain barrier.13–15 Due to the ease of obtaining blood samples from patients, the feasibility of EM-seq analysis on plasma sample should be further assessed for its diagnostic potential. Investigation using matched CSF and plasma with EM-seq technology should be performed in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available online at Neuro-Oncology Advances (https://academic.oup.com/noa).

Acknowledgments

We graciously thank The Connecticut Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) and The Children’s Brain Tumor Network (CBTN) biorepositories for their support to make this study possible, as well as the vital contribution of the patients and their families to these repositiories. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the Genome Technologies Service at The Jackson Laboratory for expert assistance with the work described herein. This study was supported in part by the Shanfield Family Fund and the Nick Strong Foundation, whose generosity enabled this research. Finally, we’d like to express our appreciation to New England Biolabs, and specifically Chaithanya Ponnaluri and Louise Williams, for providing early access to the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq v2 Kit.

EGA accession number for uploaded data: EGAS50000000871

Contributor Information

Aaron Michael Taylor, Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Jody T Lombardi, Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Areeba Patel, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany.

Ariella Tamariz, Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Jonathan Martin, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Markus J Bookland, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

David S Hersh, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Evan Cantor, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Xianyuan Song, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Felix Sahm, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany.

Patrick Kwok-Shing Ng, University of Connecticut Health, Farmington, Connecticut, USA; Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Joanna J Gell, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA; Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Ching C Lau, University of Connecticut Health, Farmington, Connecticut, USA; Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut, USA; Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, Connecticut, USA.

Funding

Martin J. Gavin Endowment and Start-up Fund (to C.C.L.); Department of Defense Cancer Research Program Career Development Award (W81XWH-22-1-0177-PRCRP to J.J.G.); CureSearch for Children’s Cancer Young Investigator Award in Pediatric Cancer Drug Development (685676 to J.J.G.); The Shanfield Family Fund (to J.J.G); Jackson Lab Cancer Center Fast Forward Award (TJL JAX CC FF Lau FY24 to C.C.L.); The Nick Strong Foundation (to C.C.L.).

Conflict of interest statement

A.M.T., J.T.L., A.P., A.T., J.M., M.J.B., D.S.H., E.C., X.S., P.K.-S.N., and J.J.G.—none declared. F.S.—co-founder and shareholder of Heidelberg Epignostix GmbH. C.C.L.—early access to the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq v2 Kit was provided by NEB.

Author contributions

Experimental design: A.M.T., J.T.L., J.J.G., P.K.-S.N., C.C.L. Implementation: A.M.T., J.T.L., A.P., A.T., J.M., M.J.B., D.S.H., E.C., X.S., F.S., P.K.-S.N., J.J.G., C.C.L. Data analysis/interpretation: A.M.T.,. J.T.L., A.P., A.T., P.K.-S.N., J.J.G., C.C.L. Manuscript writing: A.M.T., A.T., P.K.-S.N., J.J.G., C.C.L. Manuscript editing/revision: A.M.T., J.T.L., A.P., A.T., J.M., M.J.B., D.S.H., E.C., X.S., F.S., P.K.-S.N., J.J.G., C.C.L.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by both Connecticut Children’s and The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient for archival and use of the clinical samples.

Data availability

Methylation sequencing data are available at the European Genome Archive (accession number: EGAS50000000871). Raw ddPCR data available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Capper D, Stichel D, Sahm F, et al. Practical implementation of DNA methylation and copy-number-based CNS tumor diagnostics: the Heidelberg experience. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(2):181–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555(7697):469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Mattos-Arruda L, Mayor R, Ng CKY, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang J, Wang L.. Cell-Free DNA methylation profiling analysis-technologies and bioinformatics. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(11):1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, Horswell S, et al. Detection of ubiquitous and heterogeneous mutations in cell-free DNA from patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kojic M, Maybury MK, Waddell N, et al. Efficient detection and monitoring of pediatric brain malignancies with liquid biopsy based on patient-specific somatic mutation screening. Neuro-Oncology. 2023;25(8):1507–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seoane J, Escudero L.. Cerebrospinal fluid liquid biopsies for medulloblastoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(2):73–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedman JS, Hertz CAJ, Karajannis MA, Miller AM.. Tapping into the genome: the role of CSF ctDNA liquid biopsy in glioma. Neurooncol Adv. 2022;4(Suppl 2):ii33–ii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong LJ, Lueth M, Li XN, Lau CC, Vogel H.. Detection of mitochondrial DNA mutations in the tumor and cerebrospinal fluid of medulloblastoma patients. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):3866–3871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stepien N, Senfter D, Furtner J, et al. Proof-of-concept for liquid biopsy disease monitoring of MYC-amplified group 3 medulloblastoma by droplet digital PCR. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(9):2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madlener S, Furtner J, Stepien N, et al. Clinical applicability of miR517a detection in liquid biopsies of ETMR patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;145(6):843–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li J, Zhao S, Lee M, et al. Reliable tumor detection by whole-genome methylation sequencing of cell-free DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric medulloblastoma. Sci Adv. 2020;6(42). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma C, Yang X, Xing W, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA from non-small cell lung cancer brain metastasis in cerebrospinal fluid samples. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(3):588–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun Y, Li M, Ren S, et al. Exploring genetic alterations in circulating tumor DNA from cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric medulloblastoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pan Y, Long W, Liu Q.. Current advances and future perspectives of cerebrospinal fluid biopsy in midline brain malignancies. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20(12):88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones J, Nguyen H, Drummond K, Morokoff A.. Circulating biomarkers for glioma: a review. Neurosurgery. 2021;88(3):E221–E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ronvaux L, Riva M, Coosemans A, et al. Liquid biopsy in glioblastoma. Cancers. 2022;14(14):3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Afflerbach AK, Rohrandt C, Brändl B, et al. classification of brain tumors by nanopore sequencing of cell-free DNA from cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chem. 2024;70(1):250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaisvila R, Ponnaluri VKC, Sun Z, et al. Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Genome Res. 2021;31(7):1280–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. nf-core/methylseq: Huggy mollusc [computer program]. Version 2.6.0: Zenodo; 2024.

- 21. Krueger F, Andrews SR.. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(11):1571–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quinlan AR, Hall IM.. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(6):841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sahm F, Patel A, Göbel K, et al. Versatile, accessible cross-platform molecular profiling of central nervous system tumors: web-based, prospective multi-center validation. 2024.

- 24. Troyanskaya O, Cantor M, Sherlock G, et al. Missing value estimation methods for DNA microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(6):520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suvakov M, Panda A, Diesh C, Holmes I, Abyzov A.. CNVpytor: a tool for copy number variation detection and analysis from read depth and allele imbalance in whole-genome sequencing. GigaScience. 2021;10(11):giab074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He Y, Ecker JR.. Non-CG methylation in the human genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2015;16:55–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foster JM, Oumie A, Togneri FS, et al. Cross-laboratory validation of the OncoScan(R) FFPE Assay, a multiplex tool for whole genome tumour profiling. BMC Med Genomics. 2015;8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hickman RA, Miller AM, Holle BM, et al. Real-world experience with circulating tumor DNA in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with central nervous system tumors. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2024;12(1):151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Methylation sequencing data are available at the European Genome Archive (accession number: EGAS50000000871). Raw ddPCR data available upon reasonable request.