Summary

Perineuronal nets (PNNs), composed primarily of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans with core proteins and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, are specialized extracellular matrices that modulate synaptic transmission. However, the specific function of PNNs in the cerebellum, particularly in the fastigial nucleus (FN), and their influence on motor skill regulation remains unclear. Here, we initially performed chemogenetic inactivation of the FN and confirmed that the activity of glutamatergic neurons in the FN is required for both gross and fine motor skills. We then demonstrated that motor skill tasks lead to modulation of PNN-GAGs in the FN of adult mice, as evidenced by fluorescent staining, while the mRNA levels of core proteins in PNNs remain unchanged. Upon enzymatic digestion of PNN-GAGs in the FN, treated mice exhibited improved motor performance and increased inhibitory synaptic terminals compared to controls. These findings suggest that PNNs in the FN play a crucial role in modulating motor skills.

Subject areas: Natural sciences, Biological sciences, Neuroscience, Systems neuroscience, Neuroanatomy, Behavioral neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

FN glutamatergic neurons are essential for motor skill regulation

-

•

Motor skill tasks modulate PNN-GAGs in the FN of adult mice

-

•

PNN-GAG removal in the FN improves motor skills and increases inhibitory terminals

Natural sciences; Biological sciences; Neuroscience; Systems neuroscience; Neuroanatomy; Behavioral neuroscience

Introduction

Motor skills are generally divided into gross and fine motor skills based on the muscle groups involved and the amplitude of movements.1 Gross motor skills primarily engage large muscle groups, such as those in the arms and legs, and are responsible for larger movements that maintain balance and posture, such as walking and running. In contrast, fine motor skills rely on smaller muscle groups, including those in the wrists and fingers, to execute precise movements such as writing and grasping. The cerebellum plays a crucial role in coordinating movements associated with motor skills.2 The deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) provide the major output of the cerebellum. Among DCN, the fastigial nucleus (FN) is the phylogenetically oldest and serves as an evolutionarily conserved subcortical motor coordinator.3,4 The FN is involved in controlling posture, movement, and encoding proprioceptive inputs.5,6 Previous studies suggest that electrical stimulation of the FN promotes motor recovery following cerebral ischemia,7 while optogenetic inhibition of the FN alleviates dystonia in tottering mice.8 Nevertheless, the physiological and functional roles of the FN in motor skill regulation remain poorly understood.

Neuronal axon initial segments, proximal dendrites, and cell bodies are surrounded by perineuronal nets (PNNs), a specialized form of extracellular matrices (ECMs).9,10 PNNs are mesh-like structures in which chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) play a key organizational role in maintaining their structure. CSPGs consist of core proteins and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains.11,12 GAGs serve as the primary interface for PNN interactions with other cellular or matrix components.13,14 The density of PNNs is particularly high in the mammalian DCN.9,15 While PNNs in most areas of the brain typically surround parvalbumin-expressing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons, they also enclose excitatory neurons in the DCN.16,17,18,19,20 PNNs regulate synaptic transmission by acting as physical barriers.17,21,22,23 Studies in other brain regions, such as the cortex and amygdala, have demonstrated that PNNs are involved in processes such as fear memory and learning.24,25,26 Furthermore, disorganized PNNs in the spinal cord and thalamus are linked to increased excitatory synaptic inputs and motor deficits.27,28 Recent evidence suggests a role for PNNs in the DCN in motor function, as PNNs are reduced in the DCN of mice exposed to enriched environments29 and may regulate eyeblink conditioning.17,30 However, direct evidence demonstrating how PNNs regulate motor skills in the DCN, particularly in the FN, is currently lacking.

In this study, we explore whether PNNs modulate motor skills within the cerebellar system using intracranial injections and behavioral analysis. We aimed to assess the necessity of FN activity for motor skill performance and investigate the role of GAGs on PNNs in the FN of adult mice, particularly in relation to gross and fine motor skills and synaptic transmission mechanisms.

Results

Glutamatergic neurons in the FN are required for motor skills

The FN is involved in controlling body posture and locomotion.5 To test whether FN neuronal activity is necessary for motor skills, we used Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice to identify glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons31 in the FN, respectively. We expressed Cre-dependent DIO-tetanus toxin (TeNT) in the FN of both mouse strains. TeNT is a molecular tool used for synaptic inactivation.32,33 Taking Vglut2-Cre mice as an example, we first demonstrated that the density of NeuN-positive neurons in the FN remained unaffected following DIO-TeNT infection (Ctr versus TeNT: 628.8 ± 27.43 cells per 1 mm2 versus 622.5 ± 22.92 cells per 1 mm2, p = 0.8685; Figures S1A and S1B). VAMP2 serves as a cleavage substrate for TeNT and is enriched in neuronal axonal boutons, making it a useful marker for verifying TeNT activity.34 We examined VAMP2 levels in boutons of FN glutamatergic neurons projecting to the vestibular nuclei. Our results demonstrated a significant reduction in VAMP2 levels within boutons of DIO-TeNT-infected FN glutamatergic neurons (Ctr versus TeNT: 1.00 ± 0.08 versus 0.49 ± 0.04, p = 0.0036; Figures S1C and S1D), indicating that the DIO-TeNT employed possesses functional activity.

Following the injections of AAV2/9-DIO-TeNT-mCherry or control (AAV2/9-DIO-mCherry) viruses, we conducted gross motor (beam walking) and fine motor (single-pellet reaching) behavioral tests (Figures 1A–1C). Fluorescence imaging of the FN revealed large, dense glutamatergic neurons, relatively small, sparse GABAergic neurons, and confirmed AAV2/9 injection localization (Figure 1D). In Vglut2-Cre mice, inactivation of FN glutamatergic neurons significantly increased both the latency and the number of footslips in the beam-walking test (Ctr versus TeNT: latency, 7.54 ± 0.51 s versus 13.08 ± 0.71 s, p < 0.0001; number of footslips, 0.67 ± 0.18 versus 2.38 ± 0.34, p = 0.0006; Figure 1E). Although both TeNT and control mice improved their success rate over time in the single-pellet reaching test, TeNT-injected mice consistently had lower success rates than controls (Interaction, F(4,56) = 0.1720, p = 0.9518; time, F(4,56) = 9.192, p < 0.0001; group, F(1,14) = 18.49, p = 0.0007; Figure 1F). In contrast, Vgat-Cre mice did not show significant differences between TeNT and control groups in either the beam-walking (Ctr versus TeNT: latency, 7.82 ± 0.32 s versus 8.55 ± 0.53 s, p = 0.2534; number of footslips, 0.61 ± 0.14 versus 0.70 ± 0 0.13, p = 0.6444; Figure 1G) or single-pellet reaching tests (Interaction, F(4,56) = 0.0247, p = 0.9988; time, F(4,56) = 5.135, p = 0.0014; group, F(1,14) = 0.0861, p = 0.7735; Figure 1H). Taken together, these results demonstrate that FN glutamatergic neurons are essential for motor skills.

Figure 1.

Glutamatergic neurons in the FN are required for motor skills

(A and B) Behavioral paradigms for the beam-walking test and single-pellet reaching test.

(C) Schematic of the experimental design.

(D) Left: scheme for the infection of the FN with AAV2/9-DIO-mCherry or AAV2/9-DIO-TeNT-mCherry in Vglut2-Cre or Vgat-Cre mice. Right: representative images showing mCherry expression in the FN of Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice. Red indicates mCherry labeling of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons; blue indicates DAPI.

(E and F) Increased latency time and number of footslips in the beam-walking test (E) and a reduced success rate in the single-pellet reaching test (F) for Vglut2-Cre mice injected with TeNT, compared to controls (N = 8 mice per group).

(G and H) Similar performance was observed in the beam-walking test (N = 11 mice per group) (G) and a comparable success rate for pellet retrievals in the single-pellet reaching test (N = 8 mice per group) (H) for Vgat-Cre mice in Ctr and TeNT groups. Ctr, mice that received FN injection of AAV2/9-DIO-mCherry; TeNT, mice that received FN injection of AAV2/9-DIO-TeNT-mCherry.

Scale bars: 1 mm and 200 μm in (D). For (E) and (G), unpaired t test. For (F) and (H), two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the standard error of measurement (SEM). FN, fastigial nucleus; Ctr, control; TeNT, tetanus toxin.

See also Figure S1.

Expression of PNNs in the mouse FN

PNNs are ECM structures that enwrap neurons involved in motor and sensory functions. Unlike PNNs in other brain regions that surround parvalbumin interneurons, PNNs in the DCN surround excitatory neurons. We first examined the developmental expression of PNNs in the FN. Wisteria floribunda lectin (WFA), a widely used PNN marker, binds to GAG side chains on PNNs.18

Coronal sections from mice at five postnatal time points (P14, P21, P30, P60, and P75) were stained with fluorescein-conjugated WFA (Figures 2A and S2). We observed a marked increase in PNN expression in the FN until P30, after which levels plateaued with no significant changes from P30 to P75 (P14, 38.71 ± 1.17 cells per 1 mm2; P21, 56.74 ± 1.70; P30, 68.95 ± 1.68; P60, 70.44 ± 1.04; P75, 73.37 ± 1.99; F(4,20) = 84.48; p < 0.0001; Figure 2B). Based on these observations, we used two-month-old mice in subsequent experiments to align with stereotaxic surgeries and behavioral tests. To further verify the neuronal population encircled by PNNs in the FN, we injected AAV2/9-DIO-mCherry into the FN of Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice followed by WFA staining (Figure S3). The results showed that WFA-positive PNNs predominantly formed around glutamatergic neurons, with no detectable WFA reactivity around GABAergic neurons (Figures 2C–2E).

Figure 2.

Expression of PNNs in the mouse FN

(A) Representative images of WFA staining in the FN of mice at P14 and P21, where WFA labels PNNs by binding to the GAGs associated with them.

(B) The number of WFA+ PNNs in the FN increased throughout postnatal development, with no significant changes observed from P30 to P75 (N = 5 mice per group).

(C) Representative images of WFA staining in the FN of Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice following AAV2/9-DIO-mCherry injection. PNNs enwrap glutamatergic neurons in the FN. Green indicates WFA; red indicates mCherry labeling of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons.

(D and E) Top: magnified representative views from (C) show that WFA+ PNNs enwrap glutamatergic neurons (D), but not GABAergic neurons (E). Bottom: graphs illustrate the corresponding WFA and mCherry intensity scans across a white line drawn on the magnified representative neurons.

Scale bars: 50 μm (A), 40 μm (C), and 10 μm (D–E). For (B), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For (D) and (E), fit spline/locally weighted scatterplot smoothing analysis. The colocalization is represented by measuring the fluorescence intensities of overlap along profiles spanning the representative neurons. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the SEM. PNNs, perineuronal nets; FN, fastigial nucleus; WFA, Wisteria floribunda lectin; GAGs, glycosaminoglycans; WT, wild-type; P14, postnatal day 14.

See also Figures S2 and S3.

GAGs on PNNs in the FN are dynamically regulated after motor skills

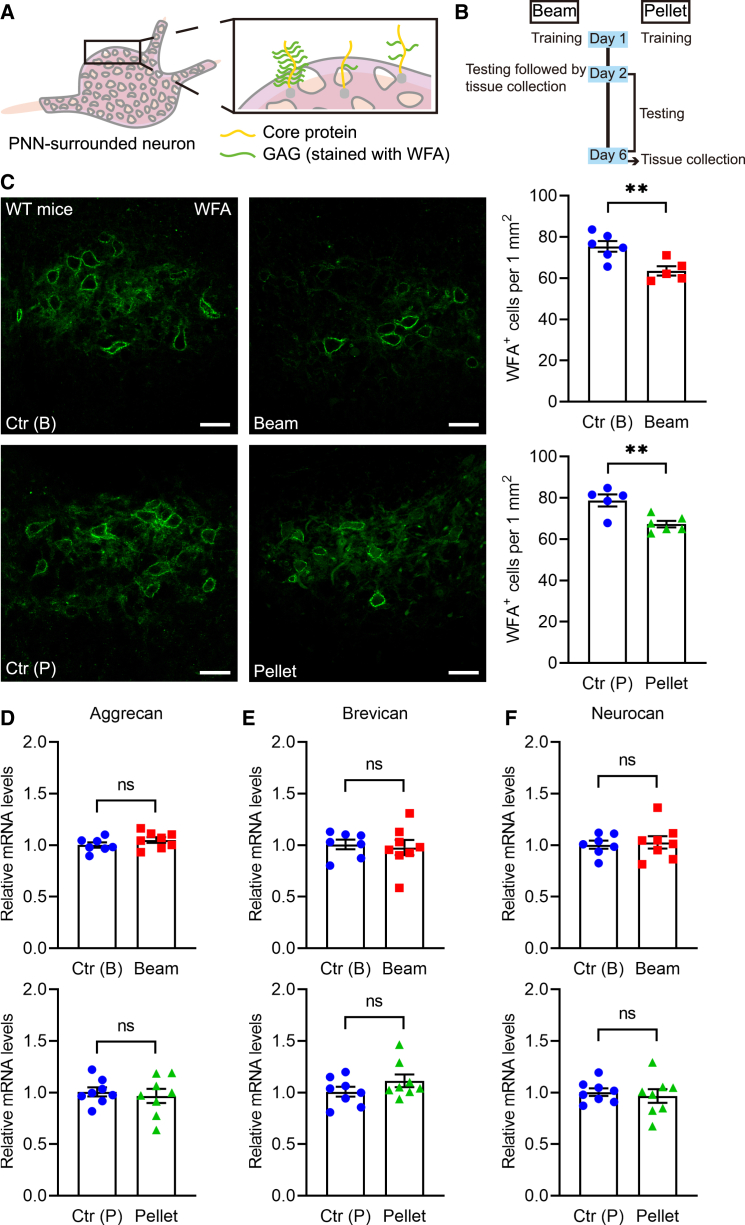

PNNs are primarily composed of CSPGs, which consist of core proteins with attached GAGs (Figure 3A). Considering the specific distribution of PNNs in the FN and their role in regulating synaptic transmission, we hypothesized that PNNs may be modulated in response to motor skill training. To test this, we compared PNNs in the FN of homecage control mice and mice subjected to motor skill tests (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

GAGs on PNNs in the FN are dynamically regulated after motor skills

(A) The schematic indicates that PNNs are primarily organized by CSPGs, which consist of core proteins with one or more attached GAG side chains.

(B) Schematic of the experimental design.

(C) Representative images of WFA staining in the FN of control mice in the homecage and mice subjected to the beam-walking and single-pellet reaching tests. The number of WFA+ PNNs in the FN was fewer in mice trained on the beam-walking and single-pellet reaching tests compared to controls (N = 5–6 mice per group).

(D–F) The mRNA levels of core proteins, including aggrecan, brevican, and neurocan, did not differ between control mice in the homecage and those subjected to the beam-walking and single-pellet reaching tests (N = 7–8 mice per group).

Scale bar: 40 μm (C). Unpaired t test. ∗∗p < 0.01; ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the SEM. PNN, perineuronal net; FN, fastigial nucleus; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; WFA, Wisteria floribunda lectin; WT, wild-type; Ctr, control.

See also Figure S4.

WFA staining was used to label GAGs on PNNs, and we observed a significant reduction in WFA in the FN of both gross motor- and fine motor-trained mice compared to controls (Ctr(B) versus beam, 75.46 ± 2.62 cells per 1 mm2 versus 63.57 ± 2.25 cells per 1 mm2, p = 0.0084; Ctr(P) versus pellet, 78.77 ± 2.90 versus 67.31 ± 1.56, p = 0.0053; Figure 3C). Additionally, no differences in WFA-positive PNNs were observed between the left and right FN in either control or trained mice (left versus right: Ctr(B), 73.01 ± 2.97 cells per 1 mm2 versus 77.91 ± 4.00 cells per 1 mm2, p = 0.3492; Ctr(P), 77.67 ± 3.31 versus 79.87 ± 3.41, p = 0.6558; beam, 63.50 ± 3.73 versus 63.65 ± 4.48, p = 0.9801; pellet, 66.99 ± 3.44 versus 67.62 ± 3.21, p = 0.8959; Figure S4A), so subsequent experiments did not distinguish between hemispheres.

Next, we investigated whether PNNs in the FN are regulated at the mRNA level following motor skill training by evaluating the mRNA expression of key core proteins, including aggrecan, brevican, and neurocan (Table 1).26 We found no significant changes in the mRNA levels of these core proteins between the motor skill-trained and control groups (aggrecan: Ctr(B) versus beam, 1.00 ± 0.03 versus 1.05 ± 0.03, p = 0.2220, Ctr(P) versus pellet, 1.01 ± 0.04 versus 0.97 ± 0.07, p = 0.6369; brevican: Ctr(B) versus beam, 1.01 ± 0.05 versus 0.98 ± 0.07, p = 0.7486, Ctr(P) versus pellet, 1.01 ± 0.05 versus 1.12 ± 0.06, p = 0.1925; neurocan: Ctr(B) versus beam, 1.01 ± 0.04 versus 1.03 ± 0.06, p = 0.7624, Ctr(P) versus pellet, 1.01 ± 0.04 versus 0.97 ± 0.07, p = 0.6192; Figures 3D–3F). We also evaluated the staining density of aggrecan in mice subjected to motor skill training. Aggrecan is the largest member of the lectican family, containing numerous GAGs, and serves as the primary carrier of WFA targets.35,36 The vast majority of WFA-positive nets in the DCN contained aggrecan.20,30 No significant difference in aggrecan staining was observed between the motor skill-trained and control groups (Ctr(B) versus beam, 81.37 ± 5.53 cells per 1 mm2 versus 84.09 ± 4.75 cells per 1 mm2, p = 0.7214; Ctr(P) versus pellet, 80.17 ± 5.85 versus 79.72 ± 5.92, p = 0.9589; Figure S4B). These results suggest that gross and fine motor skill training primarily modulates GAGs, without affecting core protein constituents of PNNs.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

| Gene | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| Gapdh | forward primer: CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT reverse primer: TTGATGGCAACAATCTCCAC |

| Acan (aggrecan) | forward primer: CCAGCCTACACCCCAGTG reverse primer: GAGGGTGGGAAGCCATGT |

| Bcan (brevican) | forward primer: GTGGAGTGGCTGTGGCTC reverse primer: AACATAGGCAGCGGAAACC |

| Ncan (neurocan) | forward primer: CCAGCGACATGGGAGTAGAT reverse primer: GGGACACTGGGTGAGATCAA |

PNN-GAG degradation in the FN enhances motor skills

Given the dynamic regulation of PNN-GAGs following motor skill tasks, we next tested whether the enzymatic digestion of PNN-GAGs in the FN would affect motor performance. Chondroitinase ABC (ChABC), an enzyme that selectively digests GAGs without affecting core proteins,37,38 was used to degrade GAGs in the FN. First, we verified the activity of ChABC by chondroitin-4-sulfate (C4S)-stub staining. The appearance of C4S-stubs confirms successful digestion of PNN-GAGs in the FN (Figure S5A). Then we evaluated the time course of PNN recovery after ChABC injection. The left hemisphere received infusions of ChABC, while the right hemisphere received infusions of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control (Figures S5B and S5C). We found that PNNs were almost completely degraded in the FN at 4 days post-injection and remained at very low levels for up to three weeks (Figure S5D).

Based on these findings, subsequent experiments were conducted within this time window. Mice received bilateral injections of ChABC or PBS into the FN, and after 6 days of recovery, were subjected to motor skill tests (Figure 4A). The digestion of GAGs was confirmed by WFA staining post-behavioral testing (PBS versus ChABC, 52.59 ± 1.30 cells per 1 mm2 versus 20.05 ± 0.81 cells per 1 mm2, p < 0.0001; Figure 4B). In the beam-walking test, ChABC-treated mice showed a significantly reduced latency to cross the beam compared to controls, although there was no significant difference in the number of footslips (PBS versus ChABC: latency, 6.79 ± 0.26 s versus 5.42 ± 0.26 s, p = 0.0021; number of footslips, 0.58 ± 0.23 versus 0.42 ± 0.12, p = 0.5239; Figure 4C). This suggests that GAG degradation enhances motor coordination but has a limited effect on balance. In the single-pellet reaching test, both groups showed improvement over time, but ChABC-treated mice exhibited a higher success rate in grasping pellets than control mice (Interaction, F(4,64) = 0.1516, p = 0.9616; time, F(4,64) = 15.38, p < 0.0001; group, F(1,16) = 6.712, p = 0.0197; Figure 4D), indicating that GAG degradation promotes the improvement of fine motor skills. Taken together, these results indicate that PNN-GAG degradation in the FN enhances motor performance.

Figure 4.

PNN-GAG degradation in the FN enhances motor skills

(A) Left: a schematic of the experimental design. Right: an FN infusion scheme with ChABC or PBS in WT mice.

(B) Verification of PNN-GAG degradation in the FN following ChABC or PBS infusion after behavioral experiments. Left: representative images of WFA staining in the FN

post-behavioral experiments. Right: the graph demonstrates that ChABC had a remarkable effect on GAG degradation (N = 5 mice per group).

(C) A decrease in latency time was observed in the beam-walking test in ChABC-treated mice compared to controls, while there was no difference in the number of footslips (N = 8 mice per group).

(D) An increased success rate in the single-pellet reaching test was observed in ChABC-treated mice compared to controls (N = 9 mice per group).

Scale bar: 100 μm. For (B) and (C), unpaired t test. For (D), two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the SEM. PNN, perineuronal net; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; FN, fastigial nucleus; dpi, days post-injection; WFA, Wisteria floribunda lectin; ChABC, chondroitinase ABC; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild-type.

See also Figure S5.

PNN-GAG degradation in the FN increases GABAergic synaptic terminals

In the FN, the majority of presynaptic terminals form synapses with glutamatergic neurons.39 Specifically, glutamatergic terminals predominantly synapse onto the dendrites of glutamatergic neurons, whereas GABAergic terminals primarily synapse onto the somata of glutamatergic neurons (Figure 5A).30 Since PNNs surround glutamatergic neurons in the FN and are known to stabilize synaptic transmission, we investigated whether the degradation of PNN-GAGs alters synaptic terminals. Following the injection of ChABC or PBS into the FN, immunofluorescence staining for Vglut2 and Vgat was used to label excitatory glutamatergic and inhibitory GABAergic presynaptic terminals, respectively,40 while WFA staining confirmed GAG degradation (Figures 5B and 5C).

Figure 5.

PNN-GAG degradation in the FN increases GABAergic terminals without affecting glutamatergic terminals

(A) The schematic indicates that the Vgat and Vglut2 terminals synapse onto neuronal somata and dendrites, respectively.

(B) Left: a schematic of the experimental design. Right: an FN infusion scheme with ChABC or PBS in WT mice.

(C) Representative images verifying infusion with ChABC or PBS in the FN at four dpi via WFA staining.

(D) Immunolabeling for Vglut2 in the FN of ChABC and PBS-infused mice at four dpi.

(E) The density and size of Vglut2 terminals did not differ between control and ChABC-treated mice (N = 6 mice per group).

(F) Immunolabeling for Vgat in the FN of ChABC and PBS-infused mice at four dpi. Unlike Vglut2 terminals, which synapse onto dendrites of neurons, Vgat terminals synapse onto and outline neuronal somata (asterisks).

(G) The density of Vgat terminals was significantly increased after ChABC treatment, while the size of Vgat terminals remained unchanged (N = 6 mice per group).

Scale bars: 40 μm (C–E). Unpaired t test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the SEM. PNN, perineuronal net; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; FN, fastigial nucleus; ChABC, chondroitinase ABC; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild-type; WFA, Wisteria floribunda lectin; GABAergic, aminobutyric acid-ergic.

See also Figure S6.

We found no significant differences in the number or size of Vglut2-positive terminals between ChABC-injected and control mice (number: PBS versus ChABC, 2,192 ± 130.50 n/mm2 versus 1,939 ± 71.23 n/mm2, p = 0.1198; size: PBS versus ChABC, 1.25 ± 0.05 μm2 versus 1.22 ± 0.05 μm2, p = 0.6824; Figures 5D and 5E). Similarly, there were no differences in the size of Vgat-positive terminals. However, the number of Vgat-positive terminals was significantly increased in ChABC-treated mice compared to controls (number: PBS versus ChABC, 144.20 ± 2.79 n/mm versus 168.40 ± 3.19 n/mm, p = 0.0002; size: PBS versus ChABC, 1.75 ± 0.06 μm2 versus 1.88 ± 0.08 μm2, p = 0.2426; Figures 5F and 5G). Given that the GABAergic terminals in the DCN predominantly originate from Purkinje cells (PCs) and local interneurons,40 we performed double staining for Vgat and calbindin. The results demonstrated that the vast majority of GABAergic terminals in the FN are derived from PCs, and the terminals primarily affected by ChABC are those of PC origin (PBS versus ChABC: calbindin+ Vgat+, 152.40 ± 3.57 n/mm versus 172.80 ± 2.65 n/mm, p = 0.0010; calbindin− Vgat+, 3.90 ± 0.28 versus 3.65 ± 0.42, p = 0.6274; Figure S6). Taken together, these findings suggest that PNN-GAG degradation in the FN selectively increases inhibitory terminals, particularly PC terminals.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the following: (1) FN glutamatergic neurons are necessary for gross and fine motor skills; (2) GAGs, rather than core proteins on PNNs in FN glutamatergic neurons, are modulated after motor skill tasks; (3) degradation of PNN-GAGs in the FN enhances motor skills; and (4) degradation of PNN-GAGs in the FN increases the number of GABAergic terminals. These findings suggest that PNN regulation in the FN plays a critical role in controlling cerebellar motor functions.

We found that FN glutamatergic neuronal activity is necessary for both gross and fine motor skills. While previous studies in cats have shown that FN inactivation or lesions primarily impair balance and coordination rather than fine motor skills such as grasping,3,41,42 our results indicate that mice with FN inactivation via TeNT injections perform poorly on both the beam-walking test (gross motor) and the single-pellet reaching test (fine motor). This highlights the significant role of glutamatergic neurons in the FN for motor skill regulation.

PNNs begin to form after birth and stabilize as the critical period of brain development ends43,44 unless disturbed by external factors such as illness. This observation aligns with our finding that PNN expression in FN glutamatergic neurons increases with age until it plateaus around P30. Interestingly, we also observed a reduction in PNN expression in adult mice following motor skill tests. This modulation was confined to the GAG side chains of the PNNs, without affecting the core proteins. Given that GAGs mediate most PNN interactions with other molecules,13,14 we propose that dysregulation of PNN-GAGs may impact motor skills by affecting synaptic transmission.

In the single-pellet reaching test, mice predominantly used one paw; however, we observed no significant difference in PNN density between the left and right FN. This suggests that unilateral limb stimulation may induce bilateral changes in the cerebellum. Existing research supports this hypothesis. First, evidence indicates that bilateral hemispheric cerebellar stimulation improves postural control.45 Second, another study has demonstrated cerebellar involvement in reactive grip control for both ipsilateral and contralateral hands.46 Additionally, a functional connectome study of the cerebellum has also revealed connectivity between the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres,47 further supporting interhemispheric information exchange.

Previous studies have reported changes in PNN expression under different conditions. For example, mice exposed to enriched environments show reduced PNN expression in the DCN, with both GAGs and core proteins affected.29 In contrast, our study found that only GAGs were modulated after motor skill tests. A similar pattern was observed in a study on the spinal cord, where GAGs on PNNs were reduced after peripheral nerve injury, while core proteins remained unaffected.37 Microglia were implicated in this reduction of GAGs, suggesting that motor skill activity might also influence glial cell activity, which in turn could regulate PNN stability. This presents a potential avenue for future research.

After establishing that PNNs are downregulated following motor skills, we investigated whether GAG modification in the FN could causally affect motor skills. By directly digesting PNN-GAGs with ChABC, we found that mice with degraded PNN-GAGs performed better in motor skill tests. This facilitative effect is similar to what has been observed in other brain areas. A previous study on delay eyeblink conditioning showed that mice injected with ChABC into the interpositus nuclei exhibited improved performance compared to control animals.48 PNN degradation has also been used to manage over-consolidated drug-related memories in the amygdala.49 However, it is worth noting that PNN-GAG degradation in the spinal cord has been linked to adverse effects such as pain sensitization.37 This region-specific difference may be associated with the neuronal populations surrounded by PNNs and their functional diversity across different brain regions. Our findings suggest a novel role for PNNs in modulating motor skills.

PNNs in the cerebellum have been shown to limit the structural plasticity of PC axons.50 A previous study, which used ChABC to disrupt PNNs in the interpositus nuclei, observed an enhanced release probability of GABA rather than the formation of new presynaptic terminals.48 In contrast to this study, we observed that PNN-GAG degradation in the FN led to an increase in GABAergic synaptic terminals, particularly at the PC terminals, while glutamatergic terminals remained unchanged. This may be related to the role of semaphorin 3A (Sema3A), a repulsive axon guidance protein involved in repelling axon growth and inhibiting synapse formation.51,52 Sema3A binds to GAGs within PNNs and is released when GAGs are degraded.14,53 Since the majority of GABAergic terminals to the DCN come from PCs,30 which express the Sema3A receptor in their axons,54,55 the release of Sema3A could enhance the number of GABAergic synaptic terminals following GAG degradation.

Limitations of the study

Our study has some limitations. First, we observed that Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice (on a C57 BL/6 genetic background) had a higher baseline success rate in the single-pellet reaching test compared to FVB wild-type mice. Despite this, both strains exhibited similar performance trends over time (Figure S7). Due to the experimental design and the cost of mice, we could not entirely eliminate this confound. Second, WFA primarily labels the non-sulfated sites of GAGs56,57; therefore, the reduction in WFA staining could result from either a decrease in the number of GAGs or structural alterations in GAGs. Although we cannot exclude this possibility, both scenarios indicate modulation of GAGs after motor skill tasks. Future studies may explore this further. Third, of the commonly studied CSPGs, we analyzed aggrecan, brevican, and neurocan,26 with aggrecan being crucial for PNNs.30,58 However, CSPGs also include versican and phosphacan,19 and thus, we cannot rule out potential changes in these two proteins. Additionally, while ChABC effectively degrades PNNs, it also impacts the interstitial ECM.59 Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the behavioral changes observed may also be influenced by the degradation of other ECM.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that PNNs in the FN play a crucial role in both gross and fine motor skills, with GAGs being the key components involved. Understanding the mechanisms underlying motor skills is essential for addressing motor deficits associated with neurological disorders. Our findings suggest that GAGs on PNNs may represent promising therapeutic targets for regulating motor-skill behavior.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yan Zeng (zengyan68@wust.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82071272) and the Postdoctor Project of Hubei Province (no. 2024HBBHJD088).

Author contributions

M.H., conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing – original draft. P.F., formal analysis and writing – review and editing. C.-l.Z., resources. J.-w.D., methodology. T.W., methodology. Y.Z., conceptualization, writing – review and editing, and funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Wisteria floribunda lectin | Vector Laboratories | Cat#FL-1351-2; RRID: AB_2336875 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-aggrecan | Millipore | Cat#AB1031; RRID: AB_90460 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-chondroitin-4-sulfate | Millipore | Cat#MAB2030; RRID: AB_94510 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-VAMP2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#13508; RRID: AB_2798240 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-NeuN | Abcam | Cat#ab177487; RRID: AB_2532109 |

| mouse monoclonal anti-Vgat | Synaptic Systems | Cat#131011; RRID: AB_887872 |

| rabbit polyclonal anti-Vglut2 | Synaptic Systems | Cat#135403; RRID: AB_887883 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-calbindin | Abcam | Cat#ab108404; RRID: AB_10861236 |

| goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 | Abcam | Cat#ab150078; RRID: AB_2722519 |

| goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 | Abcam | Cat#ab150077; RRID: AB_2630356 |

| goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 | Abcam | Cat#ab150114; RRID: AB_2687594 |

| goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Abcam | Cat#ab150113; RRID: AB_2576208 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV2/9-Ef1a-DIO-mCherry | BrainVTA | Cat#PT-0013 |

| AAV2/9-Ef1a-DIO-TeNT-mCherry | BrainVTA | Cat#PT-2139 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Chondroitinase ABC | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C3667; CAS: 9024-13-9 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: FVB | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat#004828; RRID: IMSR_JAX:004828 |

| Mouse: Vglut2-cre | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat#028863; RRID: IMSR_JAX:028863 |

| Mouse: Vgat-cre | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat#028862; RRID: IMSR_JAX:028862 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for RT-qPCR, see Table 1 | Sangon Biotech | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| OlyVIA | Olympus | https://www.olympus-global.com |

| FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer | Olympus | https://www.olympus-global.com |

Experimental model and study participant details

Animals

Postnatal day 60 male FVB wild-type (WT) mice, Vglut2-Cre mice, and Vgat-Cre mice, purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, were used in this study. Vglut2-Cre mice and Vgat-Cre mice were used for experiments requiring specific neuronal labeling, while FVB WT mice were used for other experiments. All procedures were approved by the Wuhan University of Science and Technology Animal Research Committee (No.202010). The mice were housed on a 12-h dark/light cycle (8 p.m.–8 a.m., dark) with free access to food and water. All experiments adhered to the ARRIVE Guidelines.

Method details

Intracranial injection

Anesthesia was induced at 3% isoflurane and maintained at 1.5% during surgery. Mice were secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (68803, RWD, China). Injections were administered using a glass micropipette connected to a Hamilton injector (10 μL) and a controller (UMP3, WPI, USA), with an injection rate of 40 nL/min. After the injection, the pipette was left in place for 10 min to minimize brain tissue damage and prevent infusion leakage. The stereotaxic coordinates for targeting the FN, relative to the posterior fontanelle, were: AP, −2.46 mm; ML, ±0.90 mm; DV, −3.38 mm.

To infect FN glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons with mCherry and TeNT-mCherry, AAV2/9-EF1a-DIO-mCherry (titer: 5.76E+12 vg/mL; 40 nL/injection; BrainVTA) and AAV2/9-EF1a-DIO-TeNT-mCherry (titer: 4.84E+12 vg/mL; 40 nL/injection; BrainVTA) were injected into the FN of Vglut2-Cre and Vgat-Cre mice. For the enzyme ChABC (Cat#C3667, Sigma-Aldrich) injections into the FN, it was dissolved in sterile 0.01% PBS-BSA at a concentration of 50 U/mL. The control vehicle solution used was sterile PBS. In addition, although ChABC from Sigma-Aldrich is widely used to degrade PNN-GAGs, this enzyme stock may be contaminated with additional proteinases.60 A study has also employed heat-inactivated ChABC as a control.61 Therefore, we also administered heat-inactivated ChABC and demonstrated that there was no difference in the effects of heat-inactivated ChABC and PBS on PNNs. Heat-inactivation was performed at 85°C for 45 min61,62 ChABC activity was confirmed by C4S-stub staining.62 The injection volume was set at 40 nL per injection.

Verification of injection

Mice were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The brains were removed and post-fixed in PFA for 12 h at 4°C. The brains were then dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose solutions, and 40 μm coronal sections were cut using a cryostat (Leica CM1950, Germany).

To verify the injection of AAV2/9-EF1a-DIO-mCherry and AAV2/9-EF1a-DIO-TeNT-mCherry, brain sections were examined at 10× magnification using an Olympus VS120 microscope. For verifying ChABC injections, WFA and C4S-stub staining were performed, and brain sections were imaged at 10× and 20× magnification using an Olympus VS120 microscope. OlyVIA software was used for image processing.

Behavior testing

Beam-walking test

The beam-walking test was conducted following a previously described protocol with minor modifications.63 Mice were placed 20 cm away from one end of the beam (1 m long, 0.7 cm wide), with an enclosed box at the other end. On the first day, an adaptive training was conducted. Each mouse crossed the beam three times to familiarize itself with the experimental setup. On the second day, during the testing phase, the latency to cross the beam and the number of footslips were recorded in three trials and averaged for each mouse.

Single-pellet reaching test

The single-pellet reaching test was adapted from a previous study with minor modifications.64,65 The testing apparatus was a Plexiglas box with a vertical slit in the front wall. Millet seeds were placed on a platform in front of the slit, and the mice reached through the slit to grasp the seeds. Two days prior to the test, the mice were food-restricted to 90% of their normal body weight.

The experiment was divided into two phases: training and testing. During training, mice were allowed to use both paws to grasp the seeds, and training was considered complete when the mouse made 20 grasping attempts in 20 min, with at least 14 attempts using the same paw. This paw was recorded as the preferred paw. In the testing phase, mice were allowed to attempt 30 reaches with the preferred paw in 20 min. Success was defined as the mouse successfully grasping the seed and bringing it to its mouth. The test was conducted over five days, and success rates were analyzed daily. Mice were not food-restricted during the testing phase.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% PFA in PBS. The brains were removed and post-fixed in PFA for 12 h at 4°C, then dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose solutions. Coronal sections (40 μm) were cut on a cryostat. Two to three sections per mouse were analyzed, and the mean was used for statistical analyses.

To label VAMP2 and NeuN, sections were washed in PBS and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X- for 1 h, followed by rabbit monoclonal anti-VAMP2 (Cat#13508, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000) and rabbit monoclonal anti-NeuN (Cat#ab177487, Abcam, 1:500) primary antibodies suspended in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X- for 12 h at 4°C. Next, the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Cat#ab150077, Abcam, 1:800) secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were imaged at 40× magnification using an Olympus FV1000 microscope or at 10× magnification using an Olympus VS120 microscope. Image processing was performed using FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer or OlyVIA software. VAMP2 fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ. NeuN-positive neurons were quantified using the “multi-point” function in ImageJ.

For PNN labeling, brain sections were washed in PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated WFA (4 μg/mL; Cat#FL-1351-2, Vector Laboratories) in PBS for 12 h at 4°C. None of the reagents used for WFA staining contained Triton X-.37 Sections were imaged at 40× magnification using an Olympus FV1000 microscope or at 20× magnification using an Olympus VS120 microscope. Image processing was performed using FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer or OlyVIA software. The “multi-point” function in ImageJ was used to count WFA-positive PNNs.

To label aggrecan and C4S-stub, sections were washed in PBS and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h, followed by rabbit polyclonal anti-aggrecan (Cat#AB1031, Millipore, 1:1000) and mouse monoclonal anti-C4S (Cat#MAB2030, Millipore, 1:1000) primary antibodies suspended in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum for 12 h at 4°C. Next, the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Cat#ab150078, Abcam, 1:800) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 (Cat#ab150114, Abcam, 1:800) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. None of the reagents contained Triton X-.37 Sections were imaged at 40× magnification using an Olympus FV1000 microscope or at 10× magnification using an Olympus VS120 microscope. Image processing was performed using FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer or OlyVIA software. The “multi-point” function in ImageJ was used to count aggrecan-positive PNNs.

To label GABAergic, glutamatergic and PC terminals, sections were washed in PBS and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X- for 1 h, followed by mouse monoclonal anti-Vgat (Cat#131011, Synaptic Systems, 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-Vglut2 (Cat#135403, Synaptic Systems, 1:1000), and rabbit monoclonal anti-calbindin (Cat#ab108404, Abcam, 1:200) primary antibodies suspended in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X- for 12 h at 4°C. Next, the sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 (Cat#ab150114, Abcam, 1:800), goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Cat#ab150113, Abcam, 1:800) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Cat#ab150078, Abcam, 1:800) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. One-micrometer-thick confocal images were taken using an Olympus FV1000 microscope with a 40× objective and 1.5× digital zoom. FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer software was used to process the images. ImageJ’s “analyze particle” function was used to quantify terminals. Glutamatergic terminals were counted per mm2 of image area, because excitatory inputs primarily act on the dendrites of FN neurons. GABAergic and PC terminals were counted per mm of neuronal membrane, focusing on cell bodies >250 μm2 because inhibitory inputs act on and outline the neuronal somata of FN neurons, and PNNs in the FN are present around excitatory neurons with a larger cell body size.30

RT-qPCR

After mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, brains were immediately removed and placed on ice. The FN tissues were dissected under a stereoscopic microscope. RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using a Reverse Transcription Kit (Biosharp). cDNA served as the template for qPCR using an SYBR Green qPCR Mix Kit (Biosharp). Primers for mouse GAPDH (control), aggrecan, brevican, and neurocan are listed in Table 1 qPCR was performed on C1000 PCR cyclers (Bio-Rad) with the following parameters: one cycle at 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 40 cycles at 50°C–60°C for 30 s, and 40 cycles at 72°C for 30 s. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software, as detailed in the figure legends and Table S1. For the beam-walking test and other pairwise comparisons, an unpaired t-test was used. two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was used for the single-pellet reaching test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests was used to assess age and temporal differences in PNN expression. Fit spline/locally weighted scatterplot smoothing analysis was employed to identify neuron types surrounded by PNNs. ‘N’ represents the number of mice. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and indicated by an asterisk. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Published: July 12, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112952.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Gentier I., D’Hondt E., Shultz S., Deforche B., Augustijn M., Hoorne S., Verlaecke K., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Lenoir M. Fine and gross motor skills differ between healthy-weight and obese children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013;34:4043–4051. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sathyamurthy A., Barik A., Dobrott C.I., Matson K.J.E., Stoica S., Pursley R., Chesler A.T., Levine A.J. Cerebellospinal neurons regulate motor performance and motor learning. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X.Y., Wang J.J., Zhu J.N. Cerebellar fastigial nucleus: from anatomic construction to physiological functions. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2016;3:9. doi: 10.1186/s40673-016-0047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yopak K.E., Pakan J.M.P., Wylie D.R. In: Evolution of Nervous Systems. Second Edition. Kaas J.H., editor. Academic Press; 2017. pp. 373–385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori S., Matsui T., Kuze B., Asanome M., Nakajima K., Matsuyama K. Cerebellar-induced locomotion: reticulospinal control of spinal rhythm generating mechanism in cats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;860:94–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks J.X., Cullen K.E. Multimodal integration in rostral fastigial nucleus provides an estimate of body movement. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:10499–10511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1937-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu B., Li J., Li L., Yu L., Li C. Electrical stimulation of cerebellar fastigial nucleus promotes the expression of growth arrest and DNA damage inducible gene beta and motor function recovery in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;520:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J.E., Chae S., Kim S., Jung Y.J., Kang M.G., Heo W.D., Kim D. Cerebellar 5HT-2A receptor mediates stress-induced onset of dystonia. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lafarga M., Berciano M.T., Blanco M. The perineuronal net in the fastigial nucleus of the rat cerebellum. A Golgi and quantitative study. Anat. Embryol. 1984;170:79–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00319461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celio M.R., Blümcke I. Perineuronal nets--a specialized form of extracellular matrix in the adult nervous system. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1994;19:128–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruoslahti E. Structure and biology of proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1988;4:229–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmermann D.R., Dours-Zimmermann M.T. Extracellular matrix of the central nervous system: from neglect to challenge. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2008;130:635–653. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beurdeley M., Spatazza J., Lee H.H.C., Sugiyama S., Bernard C., Di Nardo A.A., Hensch T.K., Prochiantz A. Otx2 binding to perineuronal nets persistently regulates plasticity in the mature visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:9429–9437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0394-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dick G., Tan C.L., Alves J.N., Ehlert E.M.E., Miller G.M., Hsieh-Wilson L.C., Sugahara K., Oosterhof A., van Kuppevelt T.H., Verhaagen J., et al. Semaphorin 3A binds to the perineuronal nets via chondroitin sulfate type E motifs in rodent brains. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:27384–27395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeger G., Brauer K., Härtig W., Brückner G. Mapping of perineuronal nets in the rat brain stained by colloidal iron hydroxide histochemistry and lectin cytochemistry. Neuroscience. 1994;58:371–388. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Ventura J., Lane M.A., Udina E. The role and modulation of spinal perineuronal nets in the healthy and injured spinal cord. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.893857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Dell D.E., Schreurs B.G., Smith-Bell C., Wang D. Disruption of rat deep cerebellar perineuronal net alters eyeblink conditioning and neuronal electrophysiology. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2021;177 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartig W., Brauer K., Bruckner G. Wisteria floribunda agglutinin-labelled nets surround parvalbumin-containing neurons. Neuroreport. 1992;3:869–872. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carulli D., Rhodes K.E., Brown D.J., Bonnert T.P., Pollack S.J., Oliver K., Strata P., Fawcett J.W. Composition of perineuronal nets in the adult rat cerebellum and the cellular origin of their components. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;494:559–577. doi: 10.1002/cne.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carulli D., Rhodes K.E., Fawcett J.W. Upregulation of aggrecan, link protein 1, and hyaluronan synthases during formation of perineuronal nets in the rat cerebellum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;501:83–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albinana E., Gutierrez-Luengo J., Hernandez-Juarez N., Baraibar A.M., Montell E., Verges J., Garcia A.G., Hernandez-Guijo J.M. Chondroitin sulfate induces depression of synaptic transmission and modulation of neuronal plasticity in rat hippocampal slices. Neural Plast. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/463854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L., Zhang Y., Ju J. Removal of perineuronal nets leads to altered neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the visual cortex with distinct time courses. Neurosci. Lett. 2022;785 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massey J.M., Amps J., Viapiano M.S., Matthews R.T., Wagoner M.R., Whitaker C.M., Alilain W., Yonkof A.L., Khalyfa A., Cooper N.G.F., et al. Increased chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan expression in denervated brainstem targets following spinal cord injury creates a barrier to axonal regeneration overcome by chondroitinase ABC and neurotrophin-3. Exp. Neurol. 2008;209:426–445. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gogolla N., Caroni P., Lüthi A., Herry C. Perineuronal nets protect fear memories from erasure. Science. 2009;325:1258–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.1174146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poli A., Viglione A., Mazziotti R., Totaro V., Morea S., Melani R., Silingardi D., Putignano E., Berardi N., Pizzorusso T. Selective disruption of perineuronal nets in mice lacking Crtl1 is sufficient to make fear memories susceptible to erasure. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023;60:4105–4119. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee S.B., Gutzeit V.A., Baman J., Aoued H.S., Doshi N.K., Liu R.C., Ressler K.J. Perineuronal nets in the adult sensory cortex are necessary for fear learning. Neuron. 2017;95:169–179.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Ventura J., Canal C., Hidalgo J., Penas C., Navarro X., Torres-Espin A., Fouad K., Udina E. Aberrant perineuronal nets alter spinal circuits, impair motor function, and increase plasticity. Exp. Neurol. 2022;358:114220. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonge K.M., Herbert M.J., Yagi M., Cook D.G., Banks W.A., Logsdon A.F. Changes in brain matrix glycan sulfation associate with reactive gliosis and motor coordination in mice with head trauma. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.745288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foscarin S., Ponchione D., Pajaj E., Leto K., Gawlak M., Wilczynski G.M., Rossi F., Carulli D. Experience-dependent plasticity and modulation of growth regulatory molecules at central synapses. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carulli D., Broersen R., de Winter F., Muir E.M., Mešković M., de Waal M., de Vries S., Boele H.J., Canto C.B., De Zeeuw C.I., Verhaagen J. Cerebellar plasticity and associative memories are controlled by perineuronal nets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:6855–6865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916163117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.An S., Li X., Deng L., Zhao P., Ding Z., Han Y., Luo Y., Liu X., Li A., Luo Q., et al. A whole-brain connectivity map of VTA and SNc glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in mice. Front. Neuroanat. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2021.818242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang X., Huang P., Huang L., Hu Z., Liu X., Shen J., Xi Y., Yang Y., Fu Y., Tao Q., et al. A visual circuit related to the nucleus reuniens for the spatial-memory-promoting effects of light treatment. Neuron. 2021;109:347–362.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy A., Kunwar P.S., Li L.Y., Stagkourakis S., Wagenaar D.A., Anderson D.J. Stimulus-specific hypothalamic encoding of a persistent defensive state. Nature. 2020;586:730–734. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao R., Ren B., Xiao Y., Tian J., Zou Y., Wei J., Qi Y., Hu A., Xie X., Huang Z.J., et al. Axo-axonic synaptic input drives homeostatic plasticity by tuning the axon initial segment structurally and functionally. Sci. Adv. 2024;10 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamaguchi Y. Lecticans: organizers of the brain extracellular matrix. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000;57:276–289. doi: 10.1007/PL00000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hardingham T.E., Fosang A.J., Dudhia J. The structure, function and turnover of aggrecan, the large aggregating proteoglycan from cartilage. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1994;32:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tansley S., Gu N., Guzmán A.U., Cai W., Wong C., Lister K.C., Muñoz-Pino E., Yousefpour N., Roome R.B., Heal J., et al. Microglia-mediated degradation of perineuronal nets promotes pain. Science. 2022;377:80–86. doi: 10.1126/science.abl6773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradbury E.J., Moon L.D.F., Popat R.J., King V.R., Bennett G.S., Patel P.N., Fawcett J.W., McMahon S.B. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumel Y., Jacobson G.A., Cohen D. Implications of functional anatomy on information processing in the deep cerebellar nuclei. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2009;3:14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.03.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamenkovic V., Stamenkovic S., Jaworski T., Gawlak M., Jovanovic M., Jakovcevski I., Wilczynski G.M., Kaczmarek L., Schachner M., Radenovic L., Andjus P.R. The extracellular matrix glycoprotein tenascin-C and matrix metalloproteinases modify cerebellar structural plasticity by exposure to an enriched environment. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017;222:393–415. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1224-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milak M.S., Shimansky Y., Bracha V., Bloedel J.R. Effects of inactivating individual cerebellar nuclei on the performance and retention of an operantly conditioned forelimb movement. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:939–959. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin J.H., Cooper S.E., Hacking A., Ghez C. Differential effects of deep cerebellar nuclei inactivation on reaching and adaptive control. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1886–1899. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruckner G., Grosche J., Schmidt S., Hartig W., Margolis R.U., Delpech B., Seidenbecher C.I., Czaniera R., Schachner M. Postnatal development of perineuronal nets in wild-type mice and in a mutant deficient in tenascin-R. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;428:616–629. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001225)428:4<616::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye Q., Miao Q.L. Experience-dependent development of perineuronal nets and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan receptors in mouse visual cortex. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qurat Ul A., Ahmad Z., Ilyas S., Ishtiaq S., Tariq I., Nawaz Malik A., Liu T., Wang J. Comparison of a single session of tDCS on cerebellum vs. motor cortex in stroke patients: a randomized sham-controlled trial. Ann. Med. 2023;55 doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2252439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anens E., Kristensen B., Häger-Ross C. Reactive grip force control in persons with cerebellar stroke: effects on ipsilateral and contralateral hand. Exp. Brain Res. 2010;203:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Z., Zhang R., Huo H., Liu P., Zhang C., Feng T. Functional connectome of human cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2022;251 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirono M., Watanabe S., Karube F., Fujiyama F., Kawahara S., Nagao S., Yanagawa Y., Misonou H. Perineuronal nets in the deep cerebellar nuclei regulate GABAergic transmission and delay eyeblink conditioning. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:6130–6144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3238-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue Y.X., Xue L.F., Liu J.F., He J., Deng J.H., Sun S.C., Han H.B., Luo Y.X., Xu L.Z., Wu P., Lu L. Depletion of perineuronal nets in the amygdala to enhance the erasure of drug memories. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:6647–6658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5390-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corvetti L., Rossi F. Degradation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans induces sprouting of intact purkinje axons in the cerebellum of the adult rat. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7150–7158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0683-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzales J., Le Berre-Scoul C., Dariel A., Bréhéret P., Neunlist M., Boudin H. Semaphorin 3A controls enteric neuron connectivity and is inversely associated with synapsin 1 expression in Hirschsprung disease. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71865-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carulli D., Foscarin S., Faralli A., Pajaj E., Rossi F. Modulation of semaphorin3A in perineuronal nets during structural plasticity in the adult cerebellum. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;57:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vo T., Carulli D., Ehlert E.M.E., Kwok J.C.F., Dick G., Mecollari V., Moloney E.B., Neufeld G., de Winter F., Fawcett J.W., Verhaagen J. The chemorepulsive axon guidance protein semaphorin3A is a constituent of perineuronal nets in the adult rodent brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;56:186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Winter F., Kwok J.C.F., Fawcett J.W., Vo T.T., Carulli D., Verhaagen J. The Chemorepulsive Protein Semaphorin 3A and Perineuronal Net-Mediated Plasticity. Neural Plast. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3679545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutekunst C.A., Stewart E.N., Gross R.E. Immunohistochemical distribution of PlexinA4 in the adult rat central nervous system. Front. Neuroanat. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartig W., Meinicke A., Michalski D., Schob S., Jager C. Update on perineuronal net staining with Wisteria floribunda Agglutinin (WFA) Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnint.2022.851988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinez C.A., Pantazopoulos H., Gisabella B., Stephens E.T., Garteiser J., Del Arco A. Choice impulsivity after repeated social stress is associated with increased perineuronal nets in the medial prefrontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 2024;14:7093. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-57599-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rowlands D., Lensjø K.K., Dinh T., Yang S., Andrews M.R., Hafting T., Fyhn M., Fawcett J.W., Dick G. Aggrecan directs extracellular matrix-mediated neuronal plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:10102–10113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1122-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paylor J.W., Wendlandt E., Freeman T.S., Greba Q., Marks W.N., Howland J.G., Winship I.R. Impaired cognitive function after perineuronal net degradation in the medial prefrontal cortex. eNeuro. 2018;5 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0253-18.2018. ENEURO.0253-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spliid C.B., Toledo A.G., Salanti A., Esko J.D., Clausen T.M. Beware, commercial chondroitinases vary in activity and substrate specificity. Glycobiology. 2021;31:103–115. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwaa056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuczynski-Noyau L., Karmann S., Alberton P., Martinez-Corral I., Nampoothiri S., Sauvé F., Lhomme T., Quarta C., Apte S.S., Bouret S., et al. A plastic aggrecan barrier modulated by peripheral energy state gates metabolic signal access to arcuate neurons. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:6701. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50798-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alonge K.M., Mirzadeh Z., Scarlett J.M., Logsdon A.F., Brown J.M., Cabrales E., Chan C.K., Kaiyala K.J., Bentsen M.A., Banks W.A., et al. Hypothalamic perineuronal net assembly is required for sustained diabetes remission induced by fibroblast growth factor 1 in rats. Nat. Metab. 2020;2:1025–1033. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00275-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Latragna A., Sabaté San José A., Tsimpos P., Vermeiren S., Gualdani R., Chakrabarti S., Callejo G., Desiderio S., Shomroni O., Sitte M., et al. Prdm12 modulates pain-related behavior by remodeling gene expression in mature nociceptors. Pain. 2022;163:e927–e941. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padmashri R., Reiner B.C., Suresh A., Spartz E., Dunaevsky A. Altered structural and functional synaptic plasticity with motor skill learning in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:19715–19723. doi: 10.1523/Jneurosci.2514-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin R., Suarez-Pinilla A.S., Garcia-Font N., Laguna-Luque M.L., Lopez-Ramos J.C., Oset-Gasque M.J., Gruart A., Delgado-Garcia J.M., Torres M., Sanchez-Prieto J. The activation of mGluR4 rescues parallel fiber synaptic transmission and LTP, motor learning and social behavior in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Mol. Autism. 2023;14:14. doi: 10.1186/s13229-023-00547-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.