Abstract

Background

Age-related hearing loss (HL) is highly prevalent among older adults, yet it often goes undetected and untreated. Routine screening in community settings is not widespread, and hearing aid uptake remains very low. We aimed to construct a composite risk score to identify individuals at high risk of HL for targeted audiometric screening.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from a community-based health screening program in Shenzhen, China. Participants underwent pure-tone audiometry at 500–8000 Hz to determine hearing thresholds. Moderate or greater HL was defined as a pure-tone average (PTA) ≥ 35dB in the better ear. Stepwise multivariable regression was used to identify predictors of HL, which were then used to develop a cumulative Hearing Risk Score (HRS).

Results

A total of 2,490 adults (mean age, 67.5 years, SD 5.8 years) were included; 32.5% (810 participants) had moderate or greater hearing loss. Of 22 risk factors included in the stepwise regression model, seven were identified: self-reported hearing difficulty, age 65 years or older, male sex, social isolation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disease. These were incorporated into the HRS, with total scores ranging from 1 to 23. The HRS was strongly associated with moderate or greater hearing loss, with adjusted odds ratios increasing from 4.50 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.57–12.88) for a score of 1 to 39.11 (13.50-113.33) for a score of 6 or more (P for trend < 0.001). Similar dose-response patterns were observed at all frequencies tested (0.5 to 8 kHz).

Conclusions

The HRS showed a clear dose-response relationship with HL and may serve as a practical tool to target older adults for confirmatory audiologic evaluation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06208-w.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Risk score, Older adults, Screening

Introduction

Age-related hearing loss is one of the most common chronic conditions affecting older adults. Globally, approximately 30% of people over 60 years of age have measurable hearing loss [1]. The prevalence of hearing impairment increases with advancing age and is higher in men than in women [2, 3]. By age 80, nearly half of older adults experience moderate or worse hearing loss [2, 4].

Despite this high prevalence, the condition often remains under-diagnosed and undertreated [4]. Many older individuals do not realize they have significant hearing deficits, or they attribute communication difficulties to other causes. Consequently, only a minority of seniors with hearing loss receive treatment, for example, an estimated 20–30% of older adults with documented hearing loss use hearing aids in high-income countries [3]. In China, usage rates are even lower, with estimates that only about 3–6% of hearing-impaired elderly people have acquired hearing aids [5]. This large detection and treatment gap represents a missed opportunity to improve older adults’ functioning and quality of life.

Unaddressed hearing loss in late life has significant public health and clinical consequences [6]. Hearing impairment contributes to communication difficulties, social isolation, depression, and cognitive decline [2, 7]. [8, 9] It has been identified as a modifiable risk factor for dementia in epidemiologic studies [10]. Encouragingly, interventions such as hearing aids can substantially improve hearing ability, communication, and social participation for many older adults [11], and recent evidence suggests they may even help slow cognitive decline in those at risk [12]. However, because many older adults never undergo hearing evaluations, they remain unaware of their impairment and do not benefit from available interventions. Unlike infant hearing loss, for which universal screening at birth is standard, there is currently no consensus or widespread practice for routine hearing loss screening in asymptomatic older adults. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the evidence insufficient to recommend universal screening in older populations [13], partly due to uncertainty about how best to identify those who would benefit and concerns about cost-effectiveness if testing everyone. As a result, hearing loss in elders is often only detected after it causes substantial handicap.

In community settings, especially in low- and middle-income regions, there is a need for simple, cost-effective strategies to improve early detection of hearing loss among older adults. One potential approach is to develop a risk stratification tool that can be applied during routine health encounters to flag individuals who are at high risk of clinically significant hearing impairment. If such individuals can be identified through a brief assessment of known risk factors, targeted audiometric testing can be performed for confirmation, thereby focusing resources on those most likely to have hearing loss. Previous studies have documented several factors associated with late-life hearing loss, including older age, male sex, a history of loud noise exposure (e.g. occupational noise), ototoxic medication or chronic ear infections, and systemic conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease [11, 14]. These factors could be combined into a composite risk score to identify individuals at risk for hearing impairment. We hypothesize that a composite Hearing Risk Score (HRS) derived from demographic, lifestyle, and health variables can effectively discriminate older adults with moderate or greater hearing loss from those with normal hearing, in a community population.

In this study, we developed a composite HRS to identify older adults at increased risk of audiometrically confirmed hearing loss, using demographic, clinical, and social variables commonly collected in routine care. Previous studies have typically examined individual risk factors or relied on subjective screening tools; in contrast, this score integrates multiple independent predictors into a single, weighted model. The HRS is intended for pragmatic application in primary care and community-based screening programs, particularly where audiometric capacity is limited. By enabling targeted referral for diagnostic evaluation, this approach could support earlier detection and management of hearing loss, and inform scalable public health strategies for ageing populations. All participants underwent pure-tone audiometry (PTA) as part of a routine health screening program, providing an opportunity to both derive the risk model and evaluate its performance against audiometric outcomes.

Methods

Study design and population

We performed a cross-sectional study using data from a routine health screening program for older adults in Longgang District, Shenzhen, China. Residents of the district above 60 years are offered annual health examinations at community health centers. Participants were enrolled using consecutive sampling: all eligible individuals who attended the screening between January and December 2024 and consented to undergo pure-tone audiometry and completed the risk factor questionnaire were included. We excluded those with incomplete audiometric data or missing key risk factor information. All included variables had less than 5% missing data. Given the low proportion of missingness and the focus on risk model development, we used complete-case analysis. The details of inclusion and exclusion are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. All participants provided informed consent for their health data to be used in research, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Longgang District Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital, Shenzhen. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational research to ensure transparency and comprehensive reporting.

This study was embedded in a routine community screening program and did not use formal sample size calculations a priori. However, the final sample of 2,490 participants, including 810 with moderate or greater hearing loss, provided sufficient statistical power for the planned multivariable regression analysis. With 22 candidate predictors initially considered and seven retained in the final model, the number of outcome events per variable exceeded the conventional minimum threshold of 10, supporting model reliability and precision of effect estimates.

Hearing assessment

Hearing function was evaluated by trained examiners using pure-tone audiometry in a sound-treated environment at the community health centers. Air-conduction hearing thresholds were measured in each ear at standard frequencies of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, 4000 Hz, and 8000 Hz. For each participant, we calculated the pure-tone average (PTA) in decibels hearing level (dB HL), defined as the mean of hearing thresholds across these frequencies in the better-hearing ear. We categorized hearing loss severity based on the PTA of the better ear. In this analysis, “moderate or greater hearing loss” was defined as a PTA ≥ 35 dB HL, roughly corresponding to at least moderate impairment in conventional classifications. Participants with PTA < 35 dB were considered to have no or mild hearing loss. This binary outcome (moderate-or-worse vs. mild-or-better) was used for risk factor modeling and is the primary outcome of interest. We also examined hearing thresholds as continuous outcomes in secondary analyses.

Risk factor data collection

A structured questionnaire and clinical examination were administered to collect information on a broad range of potential risk factors for hearing loss. The questionnaire was designed to capture both lifestyle factors (such as smoking, alcohol use, and tea consumption) and medical history (including chronic conditions like otitis media and otitis externa, as well as cardiovascular, metabolic, and cerebrovascular diseases). Details of the questionnaire are provided in the Supplementary Table S1.

Demographic variables included age (in years), sex, educational attainment (categorized as primary school or less, middle school, or college and above), annual household income (categorized in local currency as ≤ ¥9,999, ¥10,000–49,999, or ≥ ¥50,000), and lifelong occupation type (categorized as manual labor, non-manual, or other). Lifestyle factors included cigarette smoking status (categorized as never vs. ever; ever-smokers combined current and former smokers), alcohol use (never vs. current or past drinker), and tea consumption habit. Participants were also asked about sleep quality (self-rated as good/very good vs. bad/very bad) and the frequency of social contact (used as an index of social isolation). For social contact, we recorded how often the individual has in-person or phone contact with family, friends, or neighbors; those with extremely infrequent contact (essentially less than once per week or who reported feeling socially isolated) were categorized as socially isolated.

Self-reported hearing difficulty was assessed using a structured question that asked participants to evaluate their ability to hear in both quiet and noisy environments. The response options were categorized into seven levels reflecting varying degrees of perceived hearing challenges, ranging from “no difficulty in quiet environments and only occasional difficulty in noisy environments” to “unable to hear most speech even when volume is increased.” Each response was assigned a code from 1 to 7, and the responses were subsequently reordered to reflect increasing severity based on alignment with World Health Organization (WHO) classifications for hearing impairment [15]. Self-perceived hearing handicap was assessed using the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE), a 10-item screening version designed to evaluate the emotional and social impacts of hearing loss [16]. Each item was scored as 0 (no), 2 (sometimes), or 4 (yes), yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicated greater perceived hearing handicap.

Medical history was obtained for major chronic conditions and ear-related conditions. Participants reported physician-diagnosed cardiovascular disease (such as coronary heart disease or heart failure), metabolic disease (including diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome), cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischemic attack), and musculoskeletal disease (such as arthritis or chronic joint pain). We specifically inquired about histories of chronic otitis media (middle ear infection) and otitis externa (outer ear infection), as these can impact hearing. Occupational or environmental noise exposure (yes/no) were defined as regular exposure to loud noise from workplaces, machinery, or explosions without adequate hearing protection. Additional exploratory measures included symptoms of dizziness or vestibular problems and mental health screening for depression.

Risk score development

We considered 22 candidate variables in the initial analysis based on literature and hypothesized relevance [11]. These candidates included self-reported hearing difficulty, HHIE, all the demographics, lifestyle factors, and health conditions listed above. To identify the strongest independent predictors of hearing loss, we performed a stepwise multivariable logistic regression with significance threshold p < 0.05 for retention. This approach was selected to reduce model complexity while retaining variables with the strongest independent associations, supporting development of a practical screening tool. Although stepwise regression may be subject to risks of overfitting, we addressed this by ensuring an adequate number of outcome events per variable, conducting robustness checks across model specifications, and evaluating clinical plausibility of included predictors. In parallel, we also examined a linear regression model treating better-ear PTA as a continuous outcome, to ensure consistency of risk factors identified through both approaches (given that hearing loss severity is on a spectrum). In the final multivariable model, we obtained the regression coefficient (β) and 95% confidence interval for each retained predictor, along with its statistical significance.

Once the key predictors were identified through stepwise linear regression using the bilateral average hearing threshold (mean of left and right ears) as the outcome variable, we constructed a weighted additive risk score. To determine the relative contribution of each predictor, we used the smallest significant β coefficient (metabolic disease, β = 2.00) as the reference and assigned it a score of 1. Scores for other predictors were derived by dividing their β coefficients by 2.00 and rounding to the nearest integer. Accordingly, mild, moderate, and severe self-reported hearing difficulty were assigned 1, 4, and 12 points, respectively; age 65 years or older was assigned 2 points; and male sex, social isolation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disease were each assigned 1 point. Total HRS was calculated as the sum of these weighted scores, ranging from 0 to 23. For analysis, scores of 6 or more were grouped due to small sample sizes at the upper end of the distribution.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation (SD) and compared between hearing loss groups using t-tests, while categorical variables were summarized by counts and percentages and compared using chi-square tests. Hearing-related risk factors were identified using backward stepwise linear regression with a significance level of p < 0.05 for variable retention. The odds ratios (ORs) for hearing loss for each score level was calculated, using HRS 0 as the reference group. Both unadjusted (crude) and adjusted ORs were obtained. The adjusted ORs were adjusted for potential confounding variables not included in the risk score, such as education, BMI, occupation type, alcohol use, sleep quality, and other chronic diseases. These variables were selected based on prior evidence suggesting their potential as confounders in the relationship between risk factors and hearing loss, although they were not included in the final risk score due to lack of independent predictive contribution. We assessed model fit using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to evaluate discriminative performance. Multicollinearity among predictors was examined using variance inflation factors (VIFs), with all included variables showing acceptable levels (VIF < 2.0). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, with a two-tailed significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

A total of 2,490 older adults who completed both the survey and audiometric testing were included. The mean age of participants was 67.5 years (SD 5.8 years), and 52% were women. Overall, 32.5% (810 individuals) were found to have moderate or greater hearing loss (PTA ≥ 35 dB in the better ear) during screening, while the remaining 67.5% (1,680 individuals) had no hearing loss or only mild impairment (< 35 dB PTA).

Participant characteristics by hearing status

Participants with moderate or greater hearing loss were older, had a higher proportion of men, had lower educational attainment, and were more likely to have ever smoked, self-reported hearing problem and HHIE score of ≥ 1 compared to those with no or mild hearing loss. Other demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors did not differ significantly between groups (p from 0.09 to 0.57) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| No or mild hearing loss (mean PTA < 35 dB) N = 1680 |

Moderate or greater hearing loss (mean PTA ≥ 35 dB) N = 810 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.53 (5.17) | 69.91 (6.55) | < 0.001 |

| Men, N (%) | 723 (43.0%) | 604(55.1%) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 24.05 (2.17) | 23.94 (2.35) | 0.28 |

| Education, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary or below | 706 (42.22%) | 429 (53.42%) | |

| Middle School | 876 (52.39%) | 347 (43.21%) | |

| College or above | 90 (5.38%) | 27 (3.36%) | |

| Household income, Yuan/Year, N (%) | 0.09 | ||

| ≤ 9,999 | 437 (43.70%) | 258 (49.24%) | |

| 10,000 ~ 49,999 | 326 (32.60%) | 161 (30.73%) | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 237 (23.70%) | 105 (20.04%) | |

| Occupation, N (%) | 0.49 | ||

| Manual | 1374 (82.13%) | 678 (83.91%) | |

| Nonmanual | 110 (6.58%) | 51 (6.31%) | |

| Others | 189 (11.30%) | 79 (9.78%) | |

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.01 | ||

| Never | 1397 (83.75%) | 640 (79.60%) | |

| Current/ex-smoker | 271 (16.25%) | 164 (20.40%) | |

| Alcohol use, N (%) | 0.23 | ||

| Never | 1480 (88.94%) | 701 (87.19%) | |

| Current/ex-drinker | 184 (11.06%) | 103 (12.81%) | |

| Sleep status, N (%) | 0.57 | ||

| Good/very good | 1399 (83.42%) | 666 (82.43%) | |

| Bad/very bad | 278 (16.58%) | 142 (17.57%) | |

| Dizzy severity, N (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Never | 1452 (86.43%) | 700 (86.42%) | |

| Mild | 122 (7.26%) | 52 (6.42%) | |

| Severe | 106 (6.31%) | 58 (7.16%) | |

| Noise exposure, N (%) | 0.37 | ||

| No | 985 (98.50%) | 512 (97.71%) | |

| Yes | 15 (1.50%) | 12 (2.29%) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, N (%) | 0.47 | ||

| No | 967 (57.56%) | 453 (55.93%) | |

| Yes | 713 (42.44%) | 357 (44.07%) | |

| Metabolic disease, N (%) | 0.23 | ||

| No | 1331 (79.23%) | 624 (77.04%) | |

| Yes | 349 (20.77%) | 186 (22.96%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease, N (%) | 0.14 | ||

| No | 1656 (98.57%) | 791 (97.65%) | |

| Yes | 24 (1.43%) | 19 (2.35%) | |

| Musculoskeletal disease, N (%) | 0.15 | ||

| No | 1628 (96.90%) | 775 (95.68%) | |

| Yes | 52 (3.10%) | 35 (4.32%) | |

| HHIE score, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1494 (62.83%) | 884 (37.17%) | |

| >=1 | 186 (46.73%) | 398 (53.27%) | |

| Self-reported hearing problem | < 0.001 | ||

| Normal | 1107 (69.45%) | 487 (30.55%) | |

| Mild | 471 (55.02%) | 385 (44.98%) | |

| Moderate | 76 (40.86%) | 110 (59.14%) | |

| Severe | 19 (14.62%) | 111 (85.38%) |

PTA pure tone average, dB; BMI body mass index, kg/m2

Risk factors for hearing loss

Table 2 shows that, severe (β = 24.1, 95% CI: 20.9–27.4), moderate (β = 7.89, 95% CI: 5.30–10.5), and mild (β = 3.11, 95% CI: 1.59–4.63) self-reported hearing difficulties were all strongly associated with increased bilateral average hearing threshold (all p < 0.001). Older age (≥ 65 years) was also significantly associated with higher hearing threshold (β = 5.16, 95% CI: 3.69–6.62, p < 0.001), as was men (β = 2.93, 95% CI: 1.55–4.30, p < 0.001). Other significant factors included social isolation (β = 2.04, 95% CI: 0.45–3.63, p = 0.006), presence of cardiovascular disease (β = 2.03, 95% CI: 0.65–3.41, p = 0.004) and metabolic disease (β = 2.00, 95% CI: 0.33–3.66, p = 0.02). Each risk factor was assigned a weighted score, resulting in a cumulative range of 1 to 23 points in the final risk score system. The distribution of the risk score is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Stepwise screening of risk factors for bilateral average hearing threshold

| Risk factors (only significant factors were shown) | β (95% CI)† | P value | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported hearing problem | |||

| Mild | 3.11 (1.59, 4.63) | < 0.001 | 1 point |

| Moderate | 7.89 (5.30, 10.5) | < 0.001 | 4 points |

| Severe | 24.1 (20.9, 27.4) | < 0.001 | 12 points |

| Older age, ≥ 65 years | 5.16 (3.69, 6.62) | < 0.001 | 2 points |

| Male | 2.93 (1.55, 4.30) | < 0.001 | 1 point |

| Social isolation (people contact with < 1), yes | 2.04 (0.45, 3.63) | 0.006 | 1 point |

| Cardiovascular disease, yes | 2.03 (0.65, 3.41) | 0.004 | 1 point |

| Metabolic disease, yes | 2.00 (0.33, 3.66) | 0.02 | 1 point |

| Range 1 ~ 23 points | |||

†: The initial candidate variables were 22 variables, including self-reported hearing difficulty, HeariThe initial candidate variables were 22 variables, including self-reported hearing difficulty, Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly score, age, sex, education group, income group, obesity status, smoking, drinking, tea consumption, cardiovascular disease, metabolic conditions, cerebrovascular disease, musculoskeletal conditions, sleep quality, number of contacts, depression, nightmare frequency, SF-12 health score, noise exposure, otitis media, and otitis externa. Only six factors meeting the significance threshold (p < 0.05) were retained in the final model

Association between HRS and hearing loss

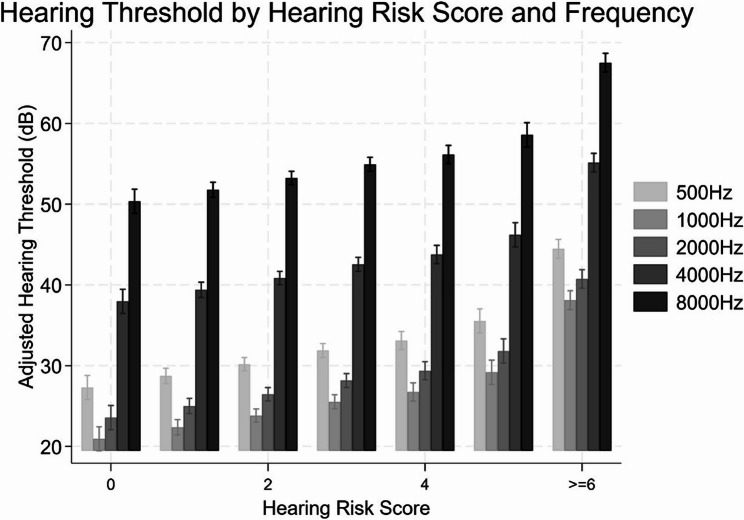

Participants with higher HRS were markedly more likely to have moderate or worse hearing impairment on audiometry, with a clear dose-response relationship (Table 3). In a multivariable logistic regression model adjusting for education level, body mass index, occupation type, alcohol use, sleep quality, and comorbidities, higher HRS were strongly associated with increased odds of hearing loss. Compared to participants with an HRS of 0, those with a score of 2 had an adjusted OR of 7.13 (95% CI: 2.54–20.05), score of 3 had OR 10.43 (95% CI: 3.71–29.34), score of 4 had OR 14.4 (95% CI: 5.02–41.28), score of 5 had OR 17.25 (95% CI: 5.74–51.8), and those with a score of 6 or more had the highest risk (adjusted OR = 39.11; 95% CI: 13.5–113.33) (p for trend < 0.001). A similar dose–response pattern was observed across all tested frequencies (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz), with adjusted ORs rising steadily as HRS increased. All frequency-specific trend tests were significant (p for trend < 0.001), indicating a consistent association between cumulative risk burden and hearing loss severity across the auditory spectrum (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between hearing risk score (HRS) and hearing loss

| HRS | N (% cases) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) † |

|---|---|---|---|

| All frequencies | |||

| 0 | 136 (9.56) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (18.39) | 2.13 (1.15–3.95) | 4.5 (1.57–12.88) |

| 2 | 689 (25.4) | 3.22 (1.77–5.85) | 7.13 (2.54–20.05) |

| 3 | 576 (35.42) | 5.19 (2.86–9.42) | 10.43 (3.71–29.34) |

| 4 | 258 (41.47) | 6.7 (3.6–12.5) | 14.4 (5.02–41.28) |

| 5 | 117 (46.15) | 8.11 (4.12–15.97) | 17.25 (5.74–51.8) |

| 6+ | 241 (70.54) | 22.65 (12-42.76) | 39.11 (13.5-113.33) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 500 Hz | |||

| 0 | 136 (18.38) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (24.74) | 1.46 (0.9–2.36) | 1.44 (0.78–2.67) |

| 2 | 689 (26.12) | 1.57 (0.99–2.5) | 1.86 (1.03–3.37) |

| 3 | 576 (29.86) | 1.89 (1.18–3.02) | 2 (1.1–3.64) |

| 4 | 258 (32.56) | 2.14 (1.29–3.56) | 2.09 (1.1–3.95) |

| 5 | 117 (35.9) | 2.49 (1.4–4.42) | 2.24 (1.09–4.59) |

| 6+ | 241 (58.51) | 6.26 (3.78–10.36) | 5.15 (2.72–9.74) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 1000 Hz | |||

| 0 | 136 (6.62) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (12.05) | 1.93 (0.93–4.01) | 5.1 (1.19–21.87) |

| 2 | 689 (14.37) | 2.37 (1.17–4.81) | 6.69 (1.59–28.08) |

| 3 | 576 (19.27) | 3.37 (1.66–6.83) | 8.66 (2.06–36.36) |

| 4 | 258 (21.71) | 3.91 (1.87–8.18) | 12.32 (2.89–52.58) |

| 5 | 117 (31.62) | 6.53 (2.99–14.24) | 20.51 (4.65–90.47) |

| 6+ | 241 (52.7) | 15.72 (7.64–32.35) | 40.13 (9.48-169.85) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 2000 Hz | |||

| 0 | 136 (8.09) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (16.28) | 2.21 (1.14–4.29) | 3.93 (1.36–11.3) |

| 2 | 689 (23.51) | 3.49 (1.84–6.63) | 6.54 (2.32–18.4) |

| 3 | 576 (30.56) | 5 (2.63–9.5) | 8.52 (3.02–24.01) |

| 4 | 258 (34.5) | 5.98 (3.07–11.67) | 11.02 (3.83–31.7) |

| 5 | 117 (39.32) | 7.36 (3.59–15.12) | 14.79 (4.92–44.51) |

| 6+ | 241 (66.39) | 22.45 (11.46–43.95) | 32.99 (11.41–95.36) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 4000 Hz | |||

| 0 | 136 (27.21) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (43.55) | 2.06 (1.36–3.14) | 3.05 (1.66–5.58) |

| 2 | 689 (61.83) | 4.33 (2.88–6.52) | 6.51 (3.6-11.77) |

| 3 | 576 (70.14) | 6.28 (4.14–9.54) | 9.56 (5.22–17.49) |

| 4 | 258 (72.87) | 7.19 (4.51–11.46) | 10.62 (5.55–20.29) |

| 5 | 117 (74.36) | 7.76 (4.43–13.6) | 11.51 (5.47–24.19) |

| 6+ | 241 (87.97) | 19.56 (11.38–33.62) | 24.52 (12.01–50.06) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 8000 Hz | |||

| 0 | 136 (60.29) | Ref (1.00) | Ref (1.00) |

| 1 | 473 (71.25) | 1.63 (1.1–2.43) | 1.8 (1.06–3.07) |

| 2 | 689 (80.26) | 2.68 (1.81–3.96) | 2.91 (1.72–4.92) |

| 3 | 576 (85.94) | 4.02 (2.65–6.1) | 4.33 (2.48–7.54) |

| 4 | 258 (88.76) | 5.2 (3.1–8.72) | 4.59 (2.45–8.63) |

| 5 | 117 (85.47) | 3.87 (2.09–7.19) | 3.95 (1.87–8.32) |

| 6+ | 241 (92.12) | 7.69 (4.3-13.76) | 7.95 (3.86–16.4) |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

†: Adjusted for BMI, education, occupation, alcohol use, sleep status, and disease history

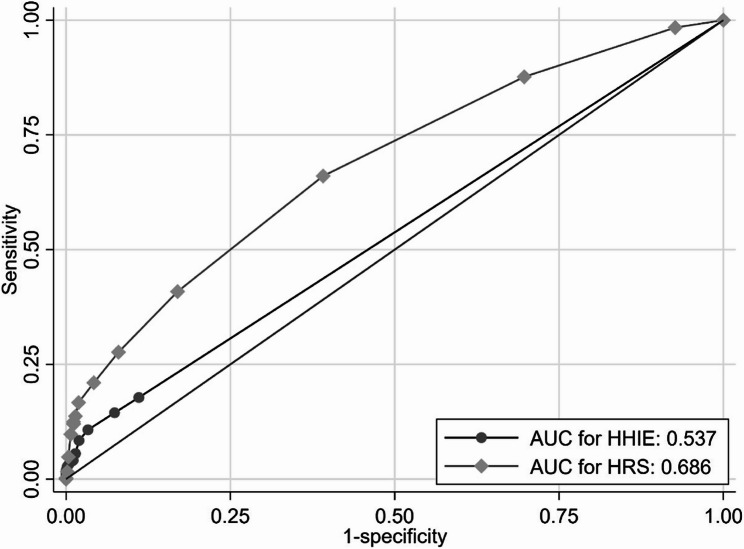

Figure 1 shows that, participants with lower risk scores (0–1) had relatively good hearing sensitivity on average, especially in lower frequencies, whereas those with high HRS showed substantially elevated thresholds, particularly at the higher frequencies. Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for the HRS and the HHIE in relation to hearing loss. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0·686 for HRS and 0·537 for HHIE (Fig. 2). The optimal cut-off point for the HRS was 2.

Fig. 1.

Age- and sex-adjusted pure-tone hearing thresholds across risk score categories at 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 8000 Hz. Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Hearing thresholds (in decibels, dB HL) were measured using pure-tone audiometry at the specified frequencies and adjusted for age and gender using linear regression. Risk scores reflect the cumulative number of hearing loss-related risk factors

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the Hearing Risk Score (HRS) and the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE)

Discussion

In this large community-based study of older adults, we developed a simple risk score to identify individuals at increased risk of hearing loss using routine health information. The HRS incorporates seven factors: self-reported hearing difficulty, age ≥ 65 years, male sex, social isolation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disease. The HRS showed a strong association with audiometrically measured hearing loss in a Chinese community sample. By relying on accessible and routinely collected variables, this tool offers potential for early risk stratification and targeted screening in primary care and community settings.

There is growing evidence that systemic health conditions such as hypertension [17], atherosclerosis [18], and diabetes [11, 19] play a role in age-related hearing loss by compromising the blood supply or neural health of the auditory system. Our finding that both cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease (a proxy for diabetes and related conditions) were independently associated with hearing loss supports the concept of hearing impairment as a multi-system geriatric issue. This suggests that clinicians managing patients with diabetes or heart disease should be attuned to the possibility of concurrent hearing decline. It also raises the question of whether better management of these chronic conditions could favorably impact auditory health, an area for future research.

The inclusion of social isolation as a risk factor in the HRS raises important questions regarding directionality. It is plausible that hearing loss contributes to social withdrawal rather than the reverse [20, 21]. We included it in the risk score because from a pragmatic standpoint, socially isolated individuals are a group that may especially benefit from outreach and screening, either because isolation may contribute to neglect of health needs including hearing, or because hearing loss itself may be contributing to their isolation [9, 22]. In either scenario, identifying someone as high risk due to social isolation provides an opportunity for intervention. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that social isolation is not a traditional “risk factor” in the causal sense; rather, it might be a marker of existing unaddressed hearing problems [23]. Further longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle these pathways and determine whether social isolation functions as a true risk factor or a marker of underlying impairment.

In our study, the adjusted odds of over 7 for HRS ≥ 2 vs. HRS of 0 seems to be quite high for an epidemiologic risk score. If one were to set a cutoff, say HRS ≥ 2, as an indicator for recommending a formal hearing test, our data suggest it would capture a large proportion of those with actual impairment (high sensitivity) while excluding many low-risk people (improving efficiency by avoiding testing everyone). We suggest an “optimal” cutoff of 2 in the present study. However, the cutoff point could be used flexibly depending on resource availability, e.g., in a resource-rich setting, anyone with score ≥ 1 might be sent for screening, whereas in a resource-limited setting, one might only target score ≥ 3 or 4 to focus on the highest risk group.

Moreover, it is worth comparing this risk score approach to other screening methods for hearing loss in older adults. Traditional screening often relies on either objective audiometric testing for all (which is resource-intensive) or simpler subjective tools like the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly, Screening (HHIE-S) questionnaire [24] or a single question (“Do you have difficulty with your hearing?”) [11, 25]. Self-report of hearing difficulty can indeed identify many people with impairment, but it may miss those who are unaware or in denial of their loss [25]. Our risk score not only focus on self-perception of hearing problem, but also accounts for objective background factors to predict risk. In practice, a combination of approaches may yield the best results, for example, administering a brief self-report hearing difficulty question and calculating the risk score. Those who either report difficulty or have a high risk score (or both) would be directed to audiometric evaluation. Such a dual approach could maximize sensitivity. On the other hand, risk factor-based screening has the advantage of leveraging information that might already be collected in primary care (age, medical history, and other relevant risk factors), without needing dedicated hearing-specific questions. The HRS we developed can be easily calculated as part of an electronic health record or a checklist during a senior health visit.

Previous studies have explored predictors of hearing loss using isolated self-reported items or audiometric thresholds in clinical cohorts [26–28]. While tools like the HHIE-S have been used for community screening, their limited sensitivity, especially among individuals unaware of their impairment, restricts their utility [29, 30]. Our composite HRS, if validated in other populations, could be a valuable tool for public health programs aimed at early detection of hearing loss. Early identification through such risk stratification can lead to timely interventions, such as counseling on hearing conservation, provision of hearing aids or assistive listening devices, and enrollment in hearing rehabilitation programs, before profound social and cognitive consequences develop. Importantly, since hearing loss has been linked to cognitive decline and dementia [2], addressing hearing issues in mid- to late-life could potentially have spillover benefits in maintaining cognitive function [31]. Recent trials suggest that treating hearing loss might slow cognitive decline in certain high-risk individuals [32], so there is urgency to connect untreated hearing-impaired seniors with care. A tool like the HRS may help bridge that connection by finding them in the first place.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to infer causality or the temporal sequence of risk factors and hearing loss. As discussed, some factors like social isolation could be a result of hearing loss. We attempted to mitigate this by focusing on long-term characteristics (e.g., history of noise exposure, chronic diseases) as opposed to transient conditions. Second, the generalizability of our findings may be constrained to similar urban community-dwelling older populations. Longgang District is a relatively developed region; the prevalence of risk factors and environmental exposures might differ in rural areas or other countries. The risk score should be validated externally in other cohorts, both within China (e.g., rural elderly or other city populations) and in different ethnic groups, to ensure it performs well broadly. Third, our definition of hearing loss (PTA ≥ 35 dB) is somewhat specific; different definitions (such as PTA ≥ 40 dB which is a more standard cutoff for moderate loss) could slightly change the prevalence and possibly which factors appear most significant. However, additional analyses using ≥ 40 dB as a cutoff (not shown) yielded very similar risk factor selection, giving us confidence in the robustness of the score. Fourth, while we did adjust and find that the HRS predicted hearing loss independent of other risk factors such as education and alcohol use, there could still be residual confounding. For instance, unmeasured factors like genetic predisposition, cumulative exposure to ototoxic medications, or quality of health care could influence results. Fifth, due to small sample sizes at the upper tail of the score distribution, we grouped HRS values of 6 or higher for analysis. While this decision reduced statistical noise and improved stability of estimates, it may have obscured more granular variations in risk within this high-score group. Future studies with larger sample sizes could explore finer stratification to characterise risk gradients more precisely. Lastly, while we demonstrated the association of the HRS with hearing loss, we have not yet demonstrated that using this score in practice actually improves outcomes. The true test will be implementation studies or trials. For example, integrating the risk score into a community screening program and seeing if it leads to increased uptake of hearing aids or improved patient-reported outcomes compared to usual care. Additionally, any screening tool runs the risk of false positives (people flagged as high risk who turn out to have normal hearing) and false negatives (people with hearing loss who were not identified by the score). The consequences of false positives here are minimal, perhaps some extra audiometric tests, but false negatives mean some impaired individuals might be missed. Given the high baseline prevalence of hearing loss, even our “low risk” group (HRS 0) was not zero risk, some had hearing loss despite no risk factors. Therefore, clinicians should remain vigilant and not entirely dismiss hearing concerns in someone with a low score, especially if they or family report symptoms.

Further research should validate this HRS prospectively and assess its utility as part of a hearing loss screening strategy. A logical next step would be to test the HRS in a new cohort of older adults and evaluate its sensitivity and specificity in detecting undiagnosed hearing loss, possibly in comparison to existing screening questionnaires or methods. It would also be useful to examine the score’s predictive value for longitudinal outcomes. For example, does a higher risk score predict faster progression of hearing loss over time? Since our study was cross-sectional, a longitudinal follow-up of this cohort could determine whether those with higher HRS indeed experience greater decline in hearing in subsequent years. If so, the score might also identify people who would benefit from more frequent hearing monitoring. On the implementation front, integrating the risk score into electronic health record systems could automate the identification of high-risk patients during routine visits. Primary care physicians could receive an alert if an older patient has, say, 4 or more risk factors, prompting a brief hearing screen or referral. Community health workers could use a paper or mobile app version of the score in outreach programs. Given that some components of the score (like social isolation or CVD history) require patient-report, an educational campaign might be needed so that older adults or their caregivers can self-assess and seek evaluation if they tally multiple risk factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this community-based study established a concise HRS incorporating seven readily available risk factors, self-reported hearing difficulty, age 65 years or older, male sex, social isolation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disease, for identifying individuals at increased risk for moderate or greater hearing loss. The score showed a clear dose-response relationship with audiometric hearing thresholds, suggesting that the HRS may serve as a practical tool for risk stratification and referral to audiometric evaluation in primary care and community health settings.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Figure S1. Distribution of the study population by Hearing Risk Score (HRS) score. Figure S2. Flow diagram of the study participants. Table S1. Hearing loss questionnaire for older people.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants and the investigators in this study.

Authors’ contributions

J.J.L, W.X.G, L.X, contributed to conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; X.H.Z contributed to conception and design, data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; J.W, Y.H.Z, F.J, Y.D.Y, P.Z, F.M, contributed to conception and design, data acquisition and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by Shenzhen Longgang Innovation of Science and Technology Commission (LGKCYLWS2023003); Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No. SZXK039); Longgang Medical Discipline Construction Fund (Key Medica Discipline in Longgang District).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from the participants. All participants provided informed consent for their health data to be used in research, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Longgang District Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital, Shenzhen.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Juan Juan Li and Wei Xiang Gao contributed equally to this work and co-first authors.

Lin Xu and Xian Hai Zeng joint senior authorship.

Contributor Information

Lin Xu, Email: xulin27@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Xian Hai Zeng, Email: zxhklwx@163.com.

References

- 1.Collaborators GA. Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ferrán S, Manrique-Huarte R, Lima JP, Rodríguez-Zanetti C, Calavia D, Andrade CJ, Terrasa D, Huarte A, Manrique M. Early detection of hearing loss among the elderly. Life. 2024;14(4):471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed NS, Garcia-Morales EE, Myers C, Huang AR, Ehrlich JR, Killeen OJ, Hoover-Fong JE, Lin FR, Arnold ML, Oh ES, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss and hearing aid use among US medicare beneficiaries aged 71 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2326320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, Orji AU, Steinmetz JD, Abdoli A, Abdollahi M, Abu-Gharbieh E, Afshin A, Ahmed H. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He P, Wen X, Hu X, Gong R, Luo Y, Guo C, Chen G, Zheng X. Hearing aid acquisition in Chinese older adults with hearing loss. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Amezcua P, Powell D, Kuo P-L, Reed NS, Sullivan KJ, Palta P, Szklo M, Sharrett R, Schrack JA, Lin FR. Association of age-related hearing impairment with physical functioning among community-dwelling older adults in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113742–2113742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell DS, Oh ES, Lin FR, Deal JA. Hearing impairment and cognition in an aging world. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2021;22(4):387–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamrah MS, Bartlett L, Goldberg LR, Bindoff A, Vickers JC. Hearing loss, social isolation and depression in participants aged 50 years or over in tasmania, Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2024;43(4):692–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H, Wang J, Jiang CQ, Zhu F, Jin YL, Zhu T, Zhang WS, Xu L. Hearing loss and depressive symptoms in older chinese: whether social isolation plays a role. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chern A, Golub JS. Age-related hearing loss and dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2019;33(3):285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Epling JW, Kubik M. Screening for hearing loss in older adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawes P, Munro KJ. Hearing loss and dementia: where to from here?? Ear Hear. 2024;45(3):529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feltner C, Wallace IF, Kistler CE, Coker-Schwimmer M, Jonas DE. Screening for hearing loss in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1202–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin J. Screening for hearing loss in older adults. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olusanya B, Davis A, Hoffman H. Hearing loss grades and the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:725–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear. 1982;3(3):128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toyama K, Mogi M. Hypertension and the development of hearing loss. Hypertens Res. 2022;45(1):172–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morales EEG, Croll PH, Palta P, Goedegebure A, Reed NS, Betz JF, Lin FR, Deal JA. Association of carotid atherosclerosis with hearing loss: A cross-sectional analysis of the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head Neck Surg. 2023;149(3):223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samocha-Bonet D, Wu B, Ryugo DK. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss: a review. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, Zhu F, Jin YL, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Xu L. Associations of face-to-face and non-face-to-face social isolation with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: 13-year follow-up of the Guangzhou biobank cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, Zhu F, Jin YL, Thomas GN, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Xu L. Persistence of social isolation and mortality: 10-year follow-up of the Guangzhou biobank cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2023;322:115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis S, Sheik Ali S, Ahmed W. A review of the impact of hearing interventions on social isolation and loneliness in older people with hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(12):4653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrijo MF, Augusto ACS, Alencar TDS, Alves AM, Luchesi BM, Martins TCR. Relationship between depressive symptoms, social isolation, visual complaints and hearing loss in middle-aged and older adults. Psychiatriki. 2023;34(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duchêne J, Billiet L, Franco V, Bonnard D. Validation of the French version of HHIE-S (Hearing handicap inventory for the Elderly-Screening) questionnaire in French over-60 year-olds. Eur Annals Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2022;139(4):198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taher T, Wu F. Hearing Loss: Unmet Needs in a Digital Age. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2025;52:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Choi JE, Moon IJ, Baek S-Y, Kim SW, Cho Y-S. Discrepancies between self-reported hearing difficulty and hearing loss diagnosed by audiometry: prevalence and associated factors in a National survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e022440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engdahl B, Aarhus L. Prevalence and predictors of self-reported hearing aid use and benefit in norway: the HUNT study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, Ciarleglio AJ, Kim AH, Luchsinger JA, Rutherford BR. Subclinical hearing loss is associated with depressive symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(5):545–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li LYJ, Wang S-Y, Wu C-J, Tsai C-Y, Wu T-F, Lin Y-S. Screening for hearing impairment in older adults by smartphone-based audiometry, self-perception, HHIE screening questionnaire, and free-field voice test: comparative evaluation of the screening accuracy with standard pure-tone audiometry. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(10):e17213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ting H-C, Huang Y-Y. Sensitivity and specificity of hearing tests for screening hearing loss in older adults. J Otology. 2023;18(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tipirneni R, Ayanian JZ. Spillover benefits of medicaid expansion for older adults with low incomes. In: JAMA health forum. 2022;3:e221389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lin FR, Pike JR, Albert MS, Arnold M, Burgard S, Chisolm T, Couper D, Deal JA, Goman AM, Glynn NW, et al. Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10404):786–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Figure S1. Distribution of the study population by Hearing Risk Score (HRS) score. Figure S2. Flow diagram of the study participants. Table S1. Hearing loss questionnaire for older people.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.