Abstract

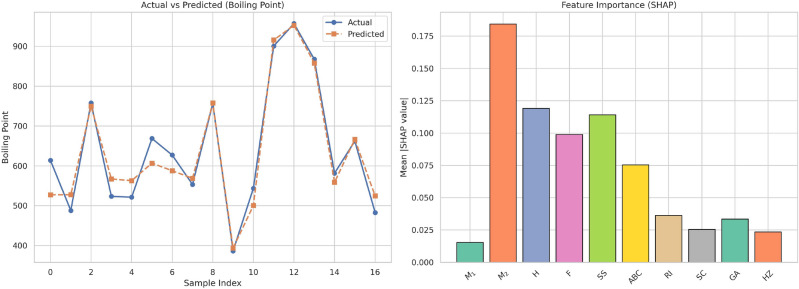

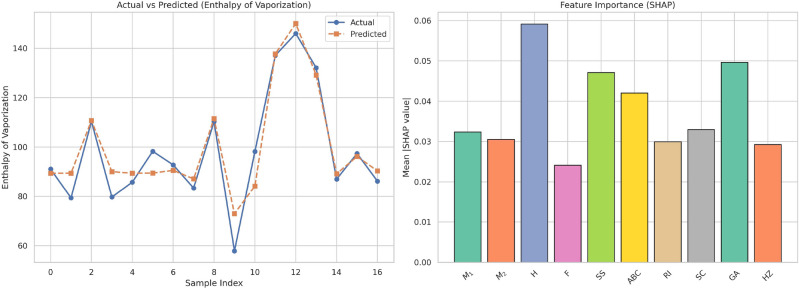

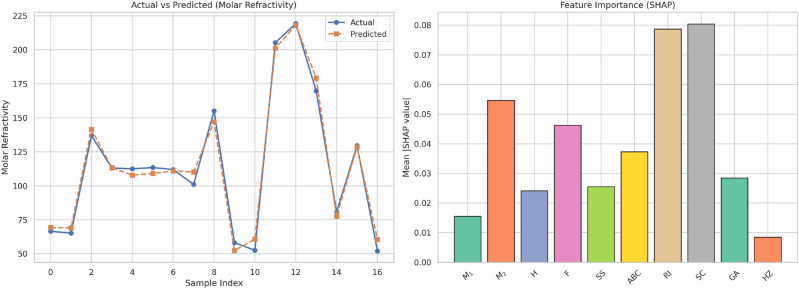

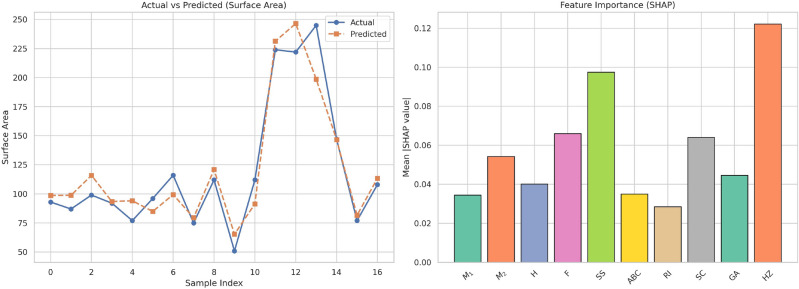

This work introduces a hybrid computational approach in which degree-based topological descriptors are harnessed with the aid of advanced regression models and artificial neural networks (ANNs) to predict the crucial physicochemical properties of 17 drugs for the treatment of bladder cancer. Each molecule is assigned a molecular graph, from which a series of topological descriptors such as Zagreb indices, Randic index, Atom Bond Connectivity (ABC), and Symmetric Division Degree (SSD)are computed. These indices are used as input features by various regression models along with linear, cubic, and feedforward ANNs. The performance of the models is analyzed using metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination  . ANNs showed the best predictive performance with the

. ANNs showed the best predictive performance with the  value achieving 0.99. Moreover, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was used to explain the contribution of each descriptor toward the models’ predictions. The findings validate the promise of the combination of graph-theoretic descriptors with the tools of machine learning to achieve solid and interpretable models of molecular property prediction, which hold the potential for drug discovery and optimization in oncologic applications.

value achieving 0.99. Moreover, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was used to explain the contribution of each descriptor toward the models’ predictions. The findings validate the promise of the combination of graph-theoretic descriptors with the tools of machine learning to achieve solid and interpretable models of molecular property prediction, which hold the potential for drug discovery and optimization in oncologic applications.

Keywords: Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Topological Indices, Degree-Based Descriptors, Cubic Regression, Linear Regression, QSPR, SHAP Analysis, Molecular Graphs, Bladder Cancer Drugs

Subject terms: Physical chemistry, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

Graph theory consists of the mathematical study of the properties of the graphs. A graph consists of a set of vertices, nodes, or points, and a set of edges, links, or lines connecting pairs of vertices. These structures are used to model pairwise relationship between elements1. These structures form the basis for a diverse range of fields including computer science, biology, transport systems, and social networks whereby elements are given by the vertices and their relationships given by the edges. The order of a graph is how many vertices there are in the graph and is usually defined as  . The degree of a vertex is how many edges it has and how many other vertices it has a connection to2. For an undirected graph, this is the number of edges that are in contact with the vertex, and for a directed graph there is a distinction made between in-degree (edges into the vertex) and out-degree (edges out of the vertex). A graph may be connected, whereby there is a path between every pair of vertices, or it might be disconnected. One of the many important problems in graph theory to solve is the problem of the shortest path between two vertices, which is used in the fields of routing and network optimization3. Another key concept within graph theory is that of cycles which are paths that begin and end in the same vertex but not visiting the same vertex or edge more than once (not counting the start/endpoint). A graph without a cycle in it is called acyclic wherein trees are a specific acyclic connnected graph4.

. The degree of a vertex is how many edges it has and how many other vertices it has a connection to2. For an undirected graph, this is the number of edges that are in contact with the vertex, and for a directed graph there is a distinction made between in-degree (edges into the vertex) and out-degree (edges out of the vertex). A graph may be connected, whereby there is a path between every pair of vertices, or it might be disconnected. One of the many important problems in graph theory to solve is the problem of the shortest path between two vertices, which is used in the fields of routing and network optimization3. Another key concept within graph theory is that of cycles which are paths that begin and end in the same vertex but not visiting the same vertex or edge more than once (not counting the start/endpoint). A graph without a cycle in it is called acyclic wherein trees are a specific acyclic connnected graph4.

Chemical graph theory is a discipline that specializes in using graph theory to model and study chemical structures and properties. Atoms in the chemical graph are modelled as vertices and chemical bonds as edges to form a molecular graph. Such graphs are typically undirected and simple, having no loop-edges or multiple edges between the same pair of vertices5. Chemical graph theory offers a good mathematical framework for the study of the topology of molecules to explain chemical behavior, predict the properties of molecules, and design new compounds. Among the key concepts is the use of topological indices as numerical values that are calculated using molecular graphs and which are related to physical, chemical or biological properties. These include the Wiener index as the sum of the shortest path distances between each pair of vertices and the Zagreb indices as a function of the degrees of the vertices. These are utilized very heavily in quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) and quantitative structure property relationship (QSPR) work in predicting how a given compound may act biologically or chemically.

Chemical graph theory also investigates the symmetry of the graph of a molecule using automorphism groups that uncover the structural equivalent and simplify the analysis of complex molecules6. Furthermore, spectral graph theory that examines the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrices that are related to the graph (such as the adjacency or Laplacian for the graph associated to a molecule), has widespread application in the study of the stability and chemical reactivity of a molecule. In organic chemistry, the graph identifies the isomers compounds of the same molecular formula but distinct in their structures based on their different graph representation7. The theory also assists in the identification of rings or cycles in molecules, which are important in the study of the aromaticity as well as other structural elements. In addition, chemical trees as a special type of graph that contains no cycle are utilized to represent the alkanes as well as other acyclic compounds. Chemical graph theory finds more and more use in computational chemistry and cheminformatics as algorithms involving graph theory are utilized in the virtual screening of huge chemical databases8. In general, chemical graph theory acts as a bridge between abstract mathematics and real-world chemistry through the provision of tools to model chemical structures methodically and predict their properties to enhance innovation in drug discovery, materials chemistry, as well as environmental chemistry.

Topological indices are quantitative values arising from a graph’s structure, particularly for molecular graphs in chemical graph theory. Topological indices represent a quantitative measure to characterize the topology of a molecule independent of the molecule’s geometric or spatial arrangement. In a graph of a molecule, atoms are vertices and bonds are edges9. Topological indices derive mathematical properties from these types of graphs to enable scientists to make correlations between the molecule’s structure and properties including boiling point, stability, biological activity, and reactivity. Topological indices are the cornerstones in quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) and quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) models for predictive chemistry in order to predict the nature of chemical compounds based on their structure10.

Huang et al.11 investigated QSPR modeling of glaucoma medication by employing XGBoost and regression methods, demonstrating good predictability for molecular properties using machine learning incorporation. Qin et al.12 proposed a Python-based QSPR model for lung cancer drugs with the use of topological descriptors, delivering good modeling of drug behavior and structure-property relationship. This research by Qin et al.13 applied graph-theoretical descriptors along with Python tools to forecast physicochemical anti-arrhythmic drug properties, providing excellent QSPR insights. Wei et al.14 used linear regression to correlate physical properties of structurally heterologous drugs, confirming the utility of topological indices in QSPR analysis. Ahmed et al.15 performed advanced QSPR modeling of NSAIDs with the use of machine learning and molecular descriptors, improving property prediction for pharmacological evaluation.

KJ16 explored cellular neural networks using new vertex-edge topological indices to study their structure and complexity. Jayanna17 investigated hyaluronic acid anticancer drug conjugates by utilizing recently developed ve-degree based topological indices to find QSPR correlations. Jayanna et al.18 investigated mathematical properties and possible uses of the Atom-Bond Sum-Connectivity index as a new graph-based molecular descriptor. Alsinai et al.19 investigated the fourth leap Zagreb index to examine the structural features of graphs. In the future, this index will be used to investigate topological behavior of other anticancer and neurological drug molecules.

Julietraja et al.20 used several VDB indices to explore superphenalene molecules. These indices provide useful tools that can be used in our coming work to investigate the physicochemical characteristics of complex drug compounds. Alsinai et al.21 introduced HDR degree-based indices and the Mhr-polynomial to study COVID-19 drugs. These mathematical descriptors can be extended in our research to simulate topological indices of other drug medicines. Javaraju et al.22 applied fp-polynomial and indices based on domination for carbidopa-levodopa employed in Parkinson’s disease. In the future, such methods might be adapted to assess structural drug properties for cancer as well as chronic diseases.

There are different types of topological indices that fall primarily under degree based, distance based eigenvalue based, and information theoretic types. Degree based ones, including the Zagreb indices, Randic index, and Atom Bond Connectivity (ABC) index, are based on the vertex degrees (number of bonds that each atom participates in). These are useful for quantifying the degree of branching or linearity of a molecule23. Distance-based ones, including the Wiener index and Harary index, are a function of the shortest path distances between vertices and work well for approximating the size and shape of the molecule. Spectral or eigenvalue-based ones utilize the eigenvalues of matrices that the graph may have in common, e.g., the adjacency or Laplacian matrix, and are useful for determining symmetry and electronic nature. Information-theoretic ones consider the molecule’s graph as a network of information and estimate uncertainty or heterogeneity in the graph24.

Topological indices are of special significance since they are easily calculated and do not need costly experimental data or 3D structural information. Therefore, they are very useful in drug discovery and materials chemistry for high-throughput screening. They can be utilized to compare molecules, predict their chemistry and to make new compounds having desired properties25. A topological index is generally validated by assessing how well the result correlates with known physical or biological data. New indices are therefore being invented and existing ones being perfected in mathematical chemistry26. Different topological descriptor shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Different topological descriptor.

| Index Name | Formula |

|---|---|

| First Zagreb Index |  |

| Second Zagreb Index |  |

| The Harmonic Index |  |

| The Forgotten Index |  |

| Symmetric Division Degree |  |

| Atom Bond Connectivity Index |  |

| Randic Index |  |

| Sum Connectivity Index |  |

| Geometric Arithmetic Index |  |

| The Hyper-Zagreb Index |  |

Bladder cancer drugs

In this section, we give a synopsis of the most important drugs used in the treatment of bladder cancer with respect to their clinical indications and mechanisms of action. We supplement these descriptions with the chemical and molecular structure of each drug as well as their physicochemical properties. This holistic method of presentation facilitates the elucidation of the chemical properties and therapeutic significance of these drugs.

Lenalidomide (LEN) is a thalidomide analog that is chemically built around a phthalimide and a glutarimide ring with an extra amino group that is added for its intensified immunomodulating activity. It acts mainly by binding to Cereblon (CRBN), a member of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which results in the specific targeting of cancer cell survival-associated transcription factors for proteasomal destruction. Lenalidomide is employed in the treatment of Myeloma (MM), Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) with deletion 5q, and Mantle Cell Lymphoma27. It is orally active with close monitoring necessitated by its potential for causing neutropenia and venous thromboembolism. LEN forms an integral part of a number of combination chemotherapy regimens. Thalidomide (THAL) is a phthalimide and glutarimide ring system-containing synthetic agent that was originally used as a sedative. It works by inhibiting the action of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha as well as modulating other pro-inflammatory cytokines28. Thalidomide interacts with Cereblon (CRBN), altering transcription and angiogenesis. It is used nowadays against Multiple Myeloma (MM) and Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL), which is a dangerous inflammatory condition of leprosy. THAL is used with strict pregnancy prevention regimens owing to its teratogenic properties.

Cabozantinib (CABO) is a multi-targeted small-molecule Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI), structured around a quinoline skeleton with a urea linker. It inhibits a number of kinases such as Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition factor (MET), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), Anexelekto receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL), and Rearranged during Transfection29. CABO is used for the treatment of Medullary Thyroid Cancer (MTC), Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). It suppresses tumor angiogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis. Sorafenib (SOR) is a Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) with a biaryl urea structure that inhibits both Raf kinases (Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma [RAF]) and Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors (VEGFR) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptors30. Sorafenib’s dual blockade blocks tumor cell growth and angiogenesis. Sorafenib is used in advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer (DTC).

Sunitinib (SUN) is an oral multi-targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor that is structurally modeled on a pyrrole-indolinone framework. It suppresses a number of receptor tyrosine kinases with the likes of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR), Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR), Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase 3 (FLT3), and Stem Cell Factor Receptor31. SUN is approved for the treatment of Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) following imatinib failure, and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNET). It is an inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor cell signaling. Axitinib (AXI) is a second-generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) that is constructed around an indazole scaffold. It is a potent inhibitor of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors 1, 2, and 3 (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3) and hence a good anti-angiogenic drug32. It is mainly employed in advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), particularly following previous treatment with other TKIs. It stifles the supply of blood into the tumors and thereby slows growth and metastasis33. It is given orally and is noted for inducing side effects such as hypertension, tiredness, and diarrhea.

Lenvatinib (LENVA) is a multi-kinase inhibitor containing a carbamate-linked quinoline core that targets Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors (VEGFR), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors (FGFR), Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR), Rearranged during Transfection (RET), and KIT. It has a broad inhibition profile that inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth34. LENVA is employed in the treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma (DTC), and combination therapy in advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC). It is an orally administered drug with possible side effects of hypertension. Erlotinib (ERLO) is a quinazoline scaffold-based epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor. It is an inhibitor of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase and inhibits signal transduction pathways that play a part in the proliferation of cancerous cells. ERLO is employed for the treatment of EGFR mutation-positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) and Pancreas Cancer (in combination with gemcitabine). It is an oral drug with side effects such as skin rash, diarrhea, and interstitial lung disease35. Neratinib (NERA) is a quinoline-modified irreversible Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) that is active against both Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR). Through the action of covalently binding with the receptors, it assures long-term inhibition. NERA is mainly used as extended adjuvant treatment in early-stage HER2-positive Breast Cancer after trastuzumab-based treatment. It is an oral drug that induces diarrhea, which is usually controlled with prophylactic antidiarrheal therapy36.

Ifosfamide (IFO) is an alkylating agent that is a member of the oxazaphosphorine class of drugs and is structurally similar to cyclophosphamide. It needs hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes for its metabolic activation into active forms that alkylate DNA and cross-link and bring about apoptosis. IFO is employed in different tumors such as Sarcomas, Testicular Cancer, and Lymphomas. It is intravenously given and is known to cause hemorrhagic cystitis that is avoided with the administration of mesna37. Cytarabine (ARA-C) is a cytosine nucleoside with an arabinose sugar in the place of ribose that acts as an inhibitor of DNA synthesis. It is activated intracellularly into cytarabine triphosphate and is incorporated into DNA and acts as an inhibitor of DNA polymerase. ARA-C finds its clinical utilization in the treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), and other haematologic malignancies. It is intravenously or intrathecally administered38. Docetaxel (DOC) is a semisynthetic derivative of the European yew tree’s paclitaxel. It is a microtubule stabilizer that blocks the depolymerization of microtubules and suppresses mitosis and induces apoptosis. DOC is indicated for the treatment of Breast Cancer, NSCLC (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer), Prostate Cancer, and Gastric Cancer. DOC is given intravenously and is associated with neutropenia, fluid retention, and neuropathy39.

Paclitaxel (PTX), obtained from the Pacific yew tree as a natural product, is a microtubule binder that stabilizes the microtubules, inhibiting the process of cell division in mitosis. PTX finds a broad range of uses in the treatment of Breast Cancer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma, NSCLC (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer), and Ovarian Cancer. Intravenous administration is common with PTX and is typically used with other chemotherapeutic drugs. Peripheral neuropathy, neutropenia, and hypersensitivity reactions are common side effects of40,41. Valrubicin (VAL) is a structurally related anthracycline derivative of doxorubicin with a trifluoroacetyl modification added for increased lipophilicity. It intercalates into DNA and is a inhibitor of the enzyme topoisomerase II that interferes with DNA replication and DNA transcription. VAL is administered intravesically for the specific treatment of Bacillus Calmette Gurin (BCG)-refractory Bladder Cancer. It is given directly into the bladder and does not have significant systemic uptake. Local bladder irritation is the most frequently observed side effect42.

Mitomycin (MMC) is a mitomycin antibiotic obtained from the organism Streptomyces caespitosus with an aziridine quinone structure. It is a metabolically activated alkylating agent that cross-linked DNA and suppresses its synthesis. MMC is employed against gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer with intravenous and intravesical uses. It is used in ophthalmic surgical procedures as an antiscarring agent. Its side effects are bone marrow suppression and hemolytic-uremic syndrome43. Erdafitinib is an oral pan-Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) inhibitor with a structure of a bis-aryl urea. It is an inhibitor of FGFR14, which interferes with the FGFR signaling pathway that is involved in cell growth and survival. It is approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma with FGFR genetic alterations. It is orally administered and is associated with hyperphosphatemia, stomatitis, and central serous retinopathy43.

Gemcitabine is a deoxycytidine nucleoside analog that is an inhibitor of DNA synthesis and an inducer of apoptosis in dividing cancer cells. It is used to treat a number of solid tumors with most frequency in bladder cancer, pancreatic cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer. In bladder cancer treatment, Gemcitabine is used most commonly as systemic chemotherapy in the treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic urothelial carcinoma as well as intravesical treatment of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), particularly for patients not responsive to Bacillus CalmetteGurin (BCG) treatment. It is most commonly given with Cisplatin for improved therapeutic responses in advanced bladder cancer. Gemcitabine is most acceptable and is an integral part of many treatment protocols in bladder cancer44.

We denote chemical structure with  , where

, where  and molecular structure with

and molecular structure with  , where

, where  . Chemical and molecular structures are shown in Fig. 1. The physicochemical properties are shown in Table 2.

. Chemical and molecular structures are shown in Fig. 1. The physicochemical properties are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Graphs  and corresponding molecular graphs

and corresponding molecular graphs  of eye disease drugs (

of eye disease drugs ( ).

).

Table 2.

Physio-chemical properties.

| Graphs | Drugs | BP | EV | FP | MR | SA | MV | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lenalidomide | 614 | 91.1 | 325.1 | 66.5 | 93 | 177.5 | 26.3 |

|

Thalidomide | 487.8 | 79.4 | 248.8 | 65.2 | 87 | 161 | 25.9 |

|

Cabozantinib | 758.1 | 110.4 | 412.3 | 137 | 99 | 359 | 54.3 |

|

Sorafenib | 523.3 | 79.7 | 290.3 | 113.1 | 92 | 319.5 | 44.8 |

|

Sunitinib | 521.1 | 85.8 | 299.8 | 112.5 | 77 | 324.1 | 44.6 |

|

Axitinib | 668.9 | 98.3 | 358.3 | 113.5 | 96 | 284.8 | 45 |

|

Lenvatinib | 627.2 | 92.8 | 333.1 | 112 | 116 | 280.6 | 44.4 |

|

Erlotinib | 553.6 | 83.4 | 288.6 | 101.1 | 75 | 315.4 | 43.6 |

|

Neratinib | 757 | 110.3 | 411.6 | 155.1 | 112 | 416.8 | 61.5 |

|

Ifosfamide | 386.5 | 57.9 | 157.1 | 58.1 | 51 | 195.7 | 23 |

|

Cytarabine | 543.7 | 98.2 | 283.8 | 52.6 | 112 | 128.4 | 20.9 |

|

Docetaxel | 900.5 | 137.1 | 498.4 | 205.2 | 224 | 585.7 | 81.4 |

|

Paclitaxel | 957.1 | 146 | 532.6 | 219.3 | 222 | 610.6 | 86.9 |

|

Valrubicin | 867.7 | 132.1 | 478.6 | 169.8 | 245 | 469.8 | 65.3 |

|

MitomycinC | 581.8 | 87 | 305.6 | 80.8 | 147 | 213.7 | 32 |

|

Erdafitinib | 662.3 | 97.4 | 354.4 | 129.6 | 77 | 389.7 | 51.4 |

|

Gemcitabine | 482.7 | 86.2 | 245.7 | 52.1 | 108 | 142.3 | 20.6 |

Main results

Theorem 1

Let  be the molecular structure of Lenalidomide with edges

be the molecular structure of Lenalidomide with edges  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  then we have:

then we have:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Proof

|

Similarly we computed different indices as shown in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Degree based topological indices.

| Drugs |  |

|

H | F | SS | ABC | RI | SC | GA | HZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenalidomide | 104 | 126 | 8.7000 | 276 | 22.5761 | 15.0442 | 9.0754 | 9.5272 | 20.3025 | 528 |

| Thalidomide | 104 | 127 | 8.7333 | 276 | 22.61 | 15.0037 | 9.0922 | 9.541 | 20.3429 | 530 |

| Cabozantinib | 200 | 240 | 17.3714 | 526 | 43.9331 | 29.075 | 17.9122 | 18.7906 | 39.9043 | 1006 |

| Sorafenib | 164 | 187 | 14.419 | 434 | 35.6701 | 24.7041 | 15.1512 | 15.6105 | 32.5468 | 808 |

| Sunitinib | 150 | 178 | 13.2667 | 392 | 32.8726 | 22.1842 | 13.8498 | 14.2734 | 29.9329 | 748 |

| Axitinib | 146 | 171 | 13.5 | 362 | 33.0132 | 21.8679 | 13.7415 | 14.4185 | 30.5058 | 704 |

| Lenvatinib | 160 | 189 | 13.9333 | 414 | 35.2178 | 23.5699 | 14.4399 | 15.1157 | 32.023 | 792 |

| Erlotinib | 142 | 163 | 14 | 344 | 32.5554 | 21.799 | 14.245 | 14.665 | 30.5254 | 670 |

| Neratinib | 202 | 233 | 18.8 | 506 | 45.3206 | 30.641 | 19.3717 | 20.0346 | 41.9052 | 972 |

| Ifosfamide | 64 | 72 | 6.4857 | 166 | 14.337 | 9.9968 | 6.7265 | 6.6908 | 13.5206 | 310 |

| Cytarabine | 88 | 105 | 7.6333 | 234 | 19.0724 | 12.9633 | 8.0409 | 8.2491 | 17.2655 | 444 |

| Docetaxel | 326 | 403 | 25.2833 | 948 | 67.6692 | 45.8641 | 26.9904 | 28.0924 | 59.6364 | 1754 |

| Paclitaxel | 346 | 429 | 27.7833 | 976 | 73.2084 | 48.9918 | 29.2723 | 30.5924 | 65.099 | 1834 |

| Valrubicin | 278 | 338 | 22.5714 | 776 | 58.8312 | 39.7812 | 23.9268 | 24.7951 | 52.4217 | 1452 |

|

142 | 185 | 10.7571 | 408 | 29.6906 | 19.1994 | 11.3403 | 11.977 | 25.9298 | 778 |

| Erdafitinib | 172 | 201 | 15.4667 | 438 | 38.2298 | 25.6223 | 15.9611 | 16.6264 | 35.0392 | 840 |

| Gemcitabine | 96 | 116 | 7.8381 | 272 | 20.1644 | 13.8365 | 8.3742 | 8.5829 | 17.9789 | 504 |

Regression models

Regression analysis is a foundational tool in statistics and machine learning used to explore and quantify relationships between variables. Among the most widely used approaches are linear and cubic regression models, each serving distinct purposes depending on the complexity of the data and the nature of the relationships involved.

A linear regression model assumes a straight-line relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. The general form is:

|

where  is the predicted outcome,

is the predicted outcome,  is the predictor,

is the predictor,  and

and  are coefficients, and

are coefficients, and  is the error term. This model is favored for its simplicity, ease of interpretation, and low computational cost. It is best suited for data where the relationship between variables remains constant across the range.

is the error term. This model is favored for its simplicity, ease of interpretation, and low computational cost. It is best suited for data where the relationship between variables remains constant across the range.

However, linear regression has limitations when applied to more complex data structures. It lacks the capacity to capture curvature or changing trends in data behavior, often leading to underfitting when non-linear patterns are present.

A cubic regression model enhances flexibility by incorporating polynomial terms up to the third degree:

|

This model is capable of capturing more complex, non-linear relationships, including inflection points and changing rates of growth or decline. Cubic regression is particularly useful in fields like pharmacokinetics, economics, and environmental modeling, where variables do not interact in strictly linear ways.

Despite its adaptability, cubic regression carries certain drawbacks. It is more susceptible to overfitting, especially when applied to small or noisy datasets. Overfitting reduces a model’s ability to generalize to new data, thus limiting its predictive utility. Moreover, interpreting the influence of each term becomes less intuitive as complexity increases.

Table 4 shows the statistical parameters and regression models of different properties in terms of the thermal index (TI) for material  . The calculated properties are

. The calculated properties are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . All the properties are developed through both linear and cubic models. The respective statistical parameters are the correlation coefficient (

. All the properties are developed through both linear and cubic models. The respective statistical parameters are the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value. Typically, the cubic models are found to have improved performance in all of the properties compared to the linear models. This can be seen from the uniformly higher

), F-statistic (F), and p-value. Typically, the cubic models are found to have improved performance in all of the properties compared to the linear models. This can be seen from the uniformly higher  and

and  values and the minimal standard errors of the cubic models. For instance, the

values and the minimal standard errors of the cubic models. For instance, the  property finds very high correlationship with both linear (

property finds very high correlationship with both linear ( ) and cubic (

) and cubic ( ) models, with the cubic model providing higher accuracy. Likewise, the

) models, with the cubic model providing higher accuracy. Likewise, the  property shows an improvement in

property shows an improvement in  from 0.922 to 0.926 and a decrease in

from 0.922 to 0.926 and a decrease in  from 12.209 to 11.758 while moving from the linear to the cubic model. All the models prove to be statistically significant, with their respective p-values at 0.000, an indicator that the regression fits as shown in Fig. 2, especially the cubic ones, are very reliable in describing the behavior of

from 12.209 to 11.758 while moving from the linear to the cubic model. All the models prove to be statistically significant, with their respective p-values at 0.000, an indicator that the regression fits as shown in Fig. 2, especially the cubic ones, are very reliable in describing the behavior of  properties as functions of

properties as functions of  .

.

Table 4.

Statistical parameters and regression models for  .

.

| Property | Models | Equations | R |  |

|

F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.936 | 0.877 | 16.934 | 106.525 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.939 | 0.881 | 53.207 | 32.047 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.918 | 0.842 | 2.720 | 80.114 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.920 | 0.846 | 8.603 | 23.773 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.943 | 0.888 | 9.876 | 119.309 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.949 | 0.901 | 29.780 | 39.327 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.975 | 0.951 | 3.394 | 291.985 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.980 | 0.960 | 9.811 | 104.262 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.840 | 0.706 | 9.310 | 35.941 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.874 | 0.764 | 26.647 | 14.044 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.960 | 0.922 | 12.209 | 176.796 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.962 | 0.926 | 37.892 | 54.512 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.971 | 0.943 | 1.438 | 249.571 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.976 | 0.953 | 4.205 | 87.086 | 0.000 |

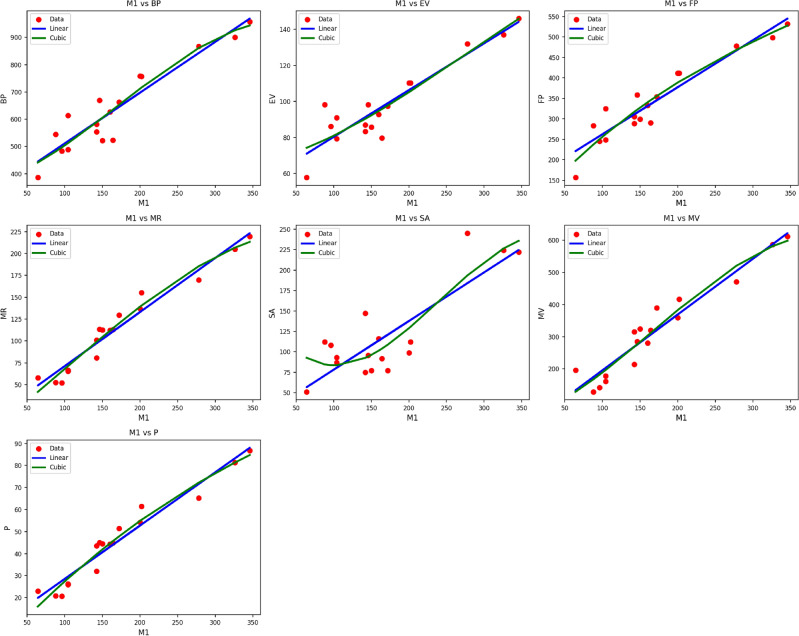

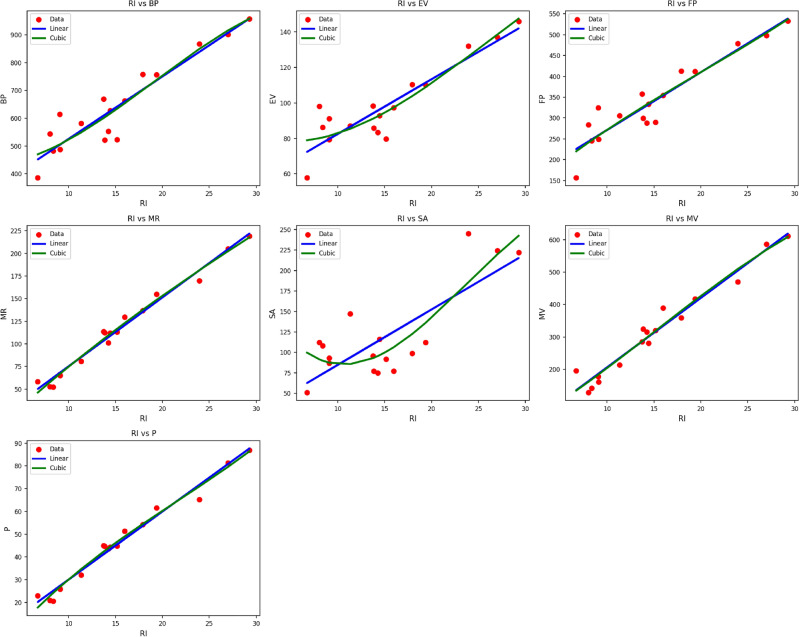

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus  .

.

Table 5 summarizes statistics parameters and regression models for different material  properties as functions of the thermal index,

properties as functions of the thermal index,  . The properties considered are

. The properties considered are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Both linear and cubic regression models were fitted to each property, and their performance is assessed with the use of statistics measures such as the correlation coefficient,

. Both linear and cubic regression models were fitted to each property, and their performance is assessed with the use of statistics measures such as the correlation coefficient,  , coefficient of determination,

, coefficient of determination,  , standard error,

, standard error,  , F-statistic, F, and the p-value. The cubic models tend to fit better than the linear models, as indicated by higher

, F-statistic, F, and the p-value. The cubic models tend to fit better than the linear models, as indicated by higher  and

and  values and lower standard errors. For instance, the

values and lower standard errors. For instance, the  property returns an

property returns an  value of 0.968 for the linear model and an

value of 0.968 for the linear model and an  value of 0.978 for the cubic model, with respective

value of 0.978 for the cubic model, with respective  values of 0.938 and 0.957. Likewise, the

values of 0.938 and 0.957. Likewise, the  property indicates that there is an improvement in model quality, with the cubic fit lowering the standard error from 9.162 to 7.392. The models are all statistically significant with associated p-values of 0.000, confirming the robustness of the models as shown in Fig. 3. The cubic models are particularly well-suited to model nonlinear trends in the property–TI relationships for

property indicates that there is an improvement in model quality, with the cubic fit lowering the standard error from 9.162 to 7.392. The models are all statistically significant with associated p-values of 0.000, confirming the robustness of the models as shown in Fig. 3. The cubic models are particularly well-suited to model nonlinear trends in the property–TI relationships for  .

.

Table 5.

Statistical parameters and regression models for  .

.

| Property | Models | Equations | R |  |

|

F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.935 | 0.875 | 16.495 | 104.967 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.941 | 0.885 | 46.040 | 33.262 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.922 | 0.850 | 2.564 | 85.266 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.923 | 0.851 | 7.437 | 24.772 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.940 | 0.884 | 9.743 | 114.258 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.952 | 0.905 | 25.573 | 41.478 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.962 | 0.926 | 4.045 | 187.475 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.968 | 0.938 | 10.784 | 65.212 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.861 | 0.742 | 8.442 | 43.031 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.888 | 0.788 | 22.215 | 16.127 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.946 | 0.895 | 13.722 | 127.202 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.949 | 0.900 | 38.824 | 39.038 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.957 | 0.917 | 1.686 | 165.239 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.964 | 0.929 | 4.540 | 56.344 | 0.000 |

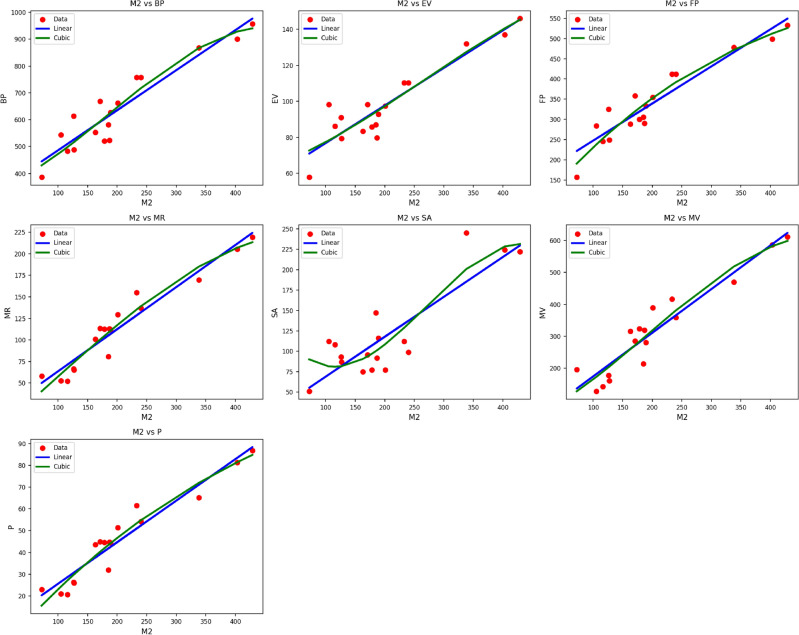

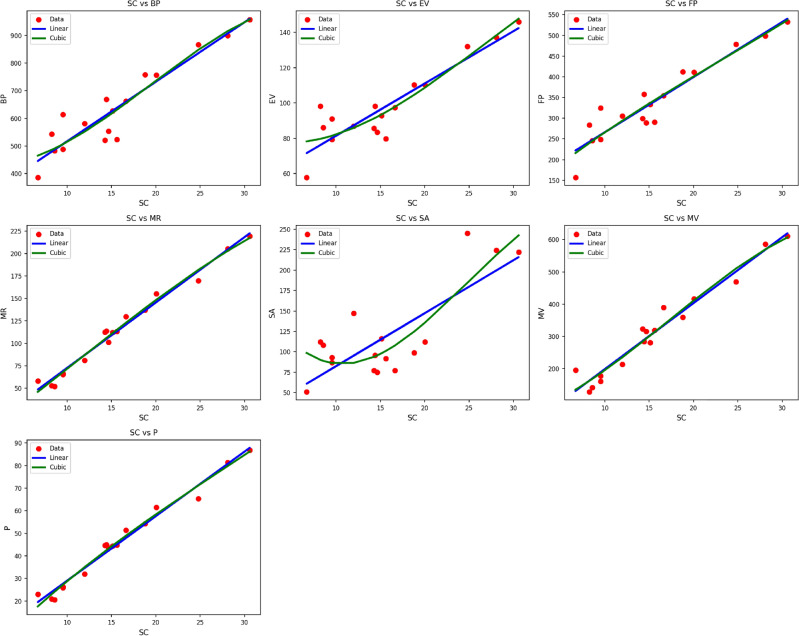

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus  .

.

Table 6 shows the statistical parameters and regression models for different material properties of  as functions of the thermal index (

as functions of the thermal index ( ). The material’s properties that are analyzed are

). The material’s properties that are analyzed are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Both linear and cubic models are fitted to each property, with performance evaluated through the use of the correlation coefficient (

. Both linear and cubic models are fitted to each property, with performance evaluated through the use of the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value. The data affirm that the cubic models tend to have better performance compared to the linear ones, as revealed by improved

), F-statistic (F), and p-value. The data affirm that the cubic models tend to have better performance compared to the linear ones, as revealed by improved  and

and  values alongside decreased standard errors. For example, the property

values alongside decreased standard errors. For example, the property  attains very high correlations under both models, with

attains very high correlations under both models, with  for the linear model and

for the linear model and  for the cubic model, and respective values of

for the cubic model, and respective values of  and

and  .

.  and

and  , too, have very high predictive performance, especially under cubic modeling. All models are significant statistically with p-values of 0.000, which verifies the validity of the regressions as shown in Fig. 4. The findings indicate that the cubic models are very effective in portraying the nonlinear relationship among thermal index and property variation for

, too, have very high predictive performance, especially under cubic modeling. All models are significant statistically with p-values of 0.000, which verifies the validity of the regressions as shown in Fig. 4. The findings indicate that the cubic models are very effective in portraying the nonlinear relationship among thermal index and property variation for  .

.

Table 6.

Statistical parameters and regression models for H(G).

| Property | Models | Equations | R |  |

|

F |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.930 | 0.864 | 20.365 | 95.519 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.933 | 0.870 | 90.127 | 28.938 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.895 | 0.800 | 3.512 | 60.063 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.912 | 0.833 | 14.522 | 21.555 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.937 | 0.878 | 11.839 | 107.949 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.937 | 0.878 | 53.478 | 31.194 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.993 | 0.985 | 2.142 | 999.014 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.993 | 0.986 | 9.479 | 300.899 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.770 | 0.592 | 12.564 | 21.789 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.846 | 0.716 | 47.398 | 10.909 | 0.001 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.981 | 0.961 | 9.834 | 373.837 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.981 | 0.962 | 44.147 | 109.428 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.992 | 0.984 | 0.877 | 920.280 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.993 | 0.985 | 3.791 | 290.754 | 0.000 |

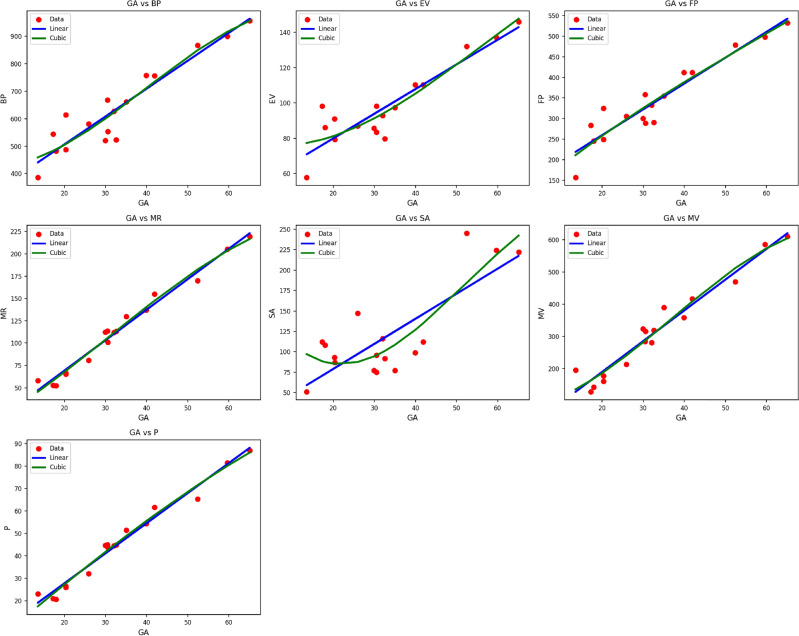

Fig. 4.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus H(G).

Table 7 shows the regression models and statistical parameters of different material property  with respect to the thermal index

with respect to the thermal index  . The considered material properties are

. The considered material properties are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Both linear and cubic regression models have been utilized, and model validity was evaluated with respect to critical statistics: correlation coefficient (

. Both linear and cubic regression models have been utilized, and model validity was evaluated with respect to critical statistics: correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value. By and large, the cubic models provide better fit and accuracy for all the properties, with greater

), F-statistic (F), and p-value. By and large, the cubic models provide better fit and accuracy for all the properties, with greater  and

and  values, and lesser standard errors. Particularly, the property

values, and lesser standard errors. Particularly, the property  shows high model fidelity, with the linear model giving

shows high model fidelity, with the linear model giving  and

and  , while the cubic model raises these to

, while the cubic model raises these to  and

and  , respectively. Correspondingly, the property

, respectively. Correspondingly, the property  gains substantially from cubic modeling, raising

gains substantially from cubic modeling, raising  from 0.896 to 0.916. All of the models are statistically significant with respective p-values of 0.000, reflecting very robust relationships as shown in Fig. 5. This highlights the use of cubic models in being able to describe the intricate, nonlinear behavior of the variation of property with thermal index for

from 0.896 to 0.916. All of the models are statistically significant with respective p-values of 0.000, reflecting very robust relationships as shown in Fig. 5. This highlights the use of cubic models in being able to describe the intricate, nonlinear behavior of the variation of property with thermal index for  .

.

Table 7.

Statistical parameters and regression models for F(G).

| Property | Models | Equations | R |  |

|

F |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.923 | 0.852 | 17.261 | 86.444 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.931 | 0.866 | 50.329 | 28.023 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.917 | 0.841 | 2.547 | 79.100 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.917 | 0.841 | 7.795 | 22.916 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.927 | 0.860 | 10.307 | 91.947 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.943 | 0.890 | 27.957 | 35.089 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.952 | 0.907 | 4.366 | 145.901 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.962 | 0.926 | 11.933 | 54.074 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.874 | 0.764 | 7.757 | 48.641 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.897 | 0.805 | 21.613 | 17.898 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.938 | 0.881 | 14.048 | 110.628 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.943 | 0.889 | 41.437 | 34.826 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.946 | 0.896 | 1.815 | 128.940 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.957 | 0.916 | 5.004 | 47.034 | 0.000 |

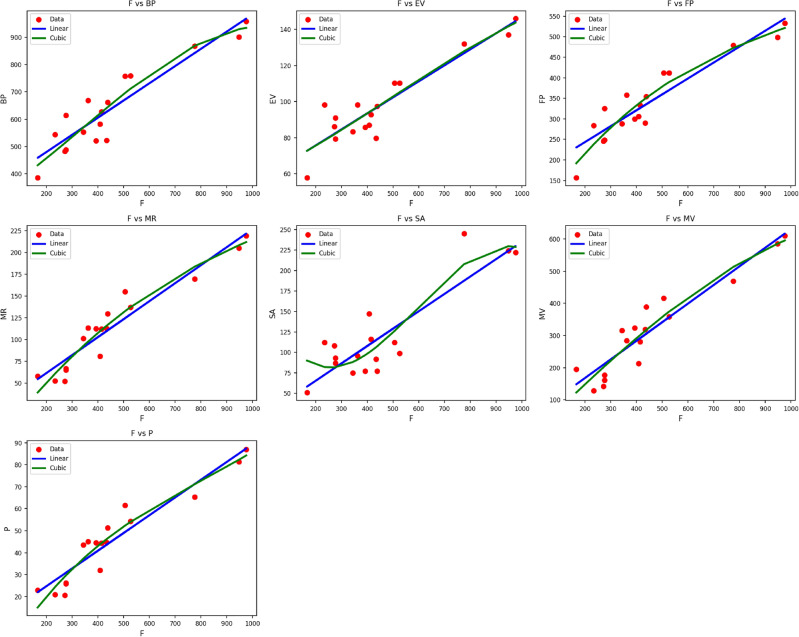

Fig. 5.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus F(G).

Table 8 presents the statistical parameters and regression models explaining the relationship between the thermal index  and selected material

and selected material  characteristics. These characteristics are

characteristics. These characteristics are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , for which both linear and cubic models have been formulated. Quality of each model is measured with the help of the correlation coefficient (

, for which both linear and cubic models have been formulated. Quality of each model is measured with the help of the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and the p-value. The cubic models have higher performance compared to the linear models in all the properties, with higher

), F-statistic (F), and the p-value. The cubic models have higher performance compared to the linear models in all the properties, with higher  and

and  values and lower standard errors. For instance, property

values and lower standard errors. For instance, property  performs very well under both models, with the cubic model producing

performs very well under both models, with the cubic model producing  , and

, and  , while the linear model offers

, while the linear model offers  , and

, and  . Similar improvement is seen in the use of cubic models for such properties as

. Similar improvement is seen in the use of cubic models for such properties as  ,

,  , and

, and  . The models are all statistically significant, with all the p-values being 0.000, which confirms the significance of the regressions as shown in Fig. 6. The results indicate the efficacy of cubic models in describing the intricate dependencies of material characteristics on the thermal index in

. The models are all statistically significant, with all the p-values being 0.000, which confirms the significance of the regressions as shown in Fig. 6. The results indicate the efficacy of cubic models in describing the intricate dependencies of material characteristics on the thermal index in  .

.

Table 8.

Statistical parameters and regression models for SS(G).

| Property | Model | Equation | R |  |

|

F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.939 | 0.882 | 17.429 | 112.553 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.941 | 0.885 | 59.488 | 33.231 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.913 | 0.834 | 2.943 | 75.346 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.919 | 0.845 | 9.805 | 23.595 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.946 | 0.896 | 10.070 | 128.659 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.949 | 0.900 | 33.888 | 39.184 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.985 | 0.969 | 2.835 | 474.289 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.987 | 0.974 | 9.028 | 161.184 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.814 | 0.663 | 10.501 | 29.518 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.861 | 0.741 | 31.737 | 12.389 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.969 | 0.939 | 11.366 | 231.024 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.971 | 0.942 | 38.151 | 70.590 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.982 | 0.964 | 1.209 | 400.999 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.984 | 0.968 | 3.894 | 133.229 | 0.000 |

Fig. 6.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus SS(G).

Table 9 illustrates the statistical parameters and regression models of the material  , investigating how different properties depend upon the thermal index (

, investigating how different properties depend upon the thermal index ( ). The considered properties are

). The considered properties are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . For all of them, both linear and cubic models were fitted, and assessed with the help of statistical characteristics: the correlation coefficient (

. For all of them, both linear and cubic models were fitted, and assessed with the help of statistical characteristics: the correlation coefficient ( ), the coefficient of determination (

), the coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and the p-value. Cubic models tend to produce a truer picture of the data, as reflected in increased

), F-statistic (F), and the p-value. Cubic models tend to produce a truer picture of the data, as reflected in increased  and

and  values as well as decreased standard errors. For example, the property

values as well as decreased standard errors. For example, the property  reflects outstanding model precision with the cubic regression achieving

reflects outstanding model precision with the cubic regression achieving  and

and  compared to the already robust linear model’s

compared to the already robust linear model’s  and

and  . Comparable improvements are seen in

. Comparable improvements are seen in  ,

,  , and

, and  , where the cubic models take into account the nonlinear trend. All models have p-values of 0.000, which verifies that they are statistically significant as shown in Fig. 7. This further proves the strength of cubic regression models to describe the thermal index-dependent behavior of

, where the cubic models take into account the nonlinear trend. All models have p-values of 0.000, which verifies that they are statistically significant as shown in Fig. 7. This further proves the strength of cubic regression models to describe the thermal index-dependent behavior of  ’s characteristics.

’s characteristics.

Table 9.

Statistical parameters and regression models for ABC(G).

| Property | Model | Equation | R |  |

|

F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.934 | 0.872 | 18.354 | 102.529 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.935 | 0.873 | 69.495 | 29.922 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.910 | 0.828 | 3.028 | 72.210 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.916 | 0.839 | 11.158 | 22.508 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.941 | 0.886 | 10.624 | 116.880 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.944 | 0.891 | 39.481 | 35.567 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.985 | 0.970 | 2.826 | 488.105 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.988 | 0.975 | 9.797 | 170.596 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.814 | 0.662 | 10.627 | 29.419 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.863 | 0.744 | 35.192 | 12.592 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.971 | 0.943 | 11.076 | 249.749 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.973 | 0.946 | 41.182 | 75.692 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.982 | 0.964 | 1.214 | 406.331 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.985 | 0.970 | 4.220 | 141.440 | 0.000 |

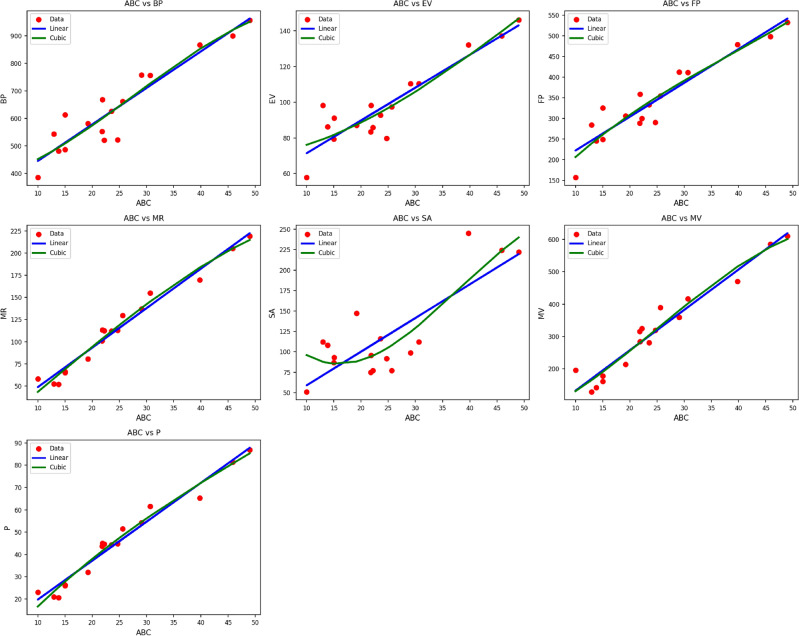

Fig. 7.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus ABC(G).

Table 10 shows the regression parameters and models for the material  , demonstrating the effect of thermal index (

, demonstrating the effect of thermal index ( ) on different characteristics such as

) on different characteristics such as  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . All the characteristics are modeled under both linear and cubic regression methods, where model performance is assessed in terms of correlation coefficient (

. All the characteristics are modeled under both linear and cubic regression methods, where model performance is assessed in terms of correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value. The cubic models continue to demonstrate better predictive performance than linear models, with higher

), F-statistic (F), and p-value. The cubic models continue to demonstrate better predictive performance than linear models, with higher  and

and  values and smaller standard errors. Particularly, the property

values and smaller standard errors. Particularly, the property  displays excellent agreement with the cubic model, reaching

displays excellent agreement with the cubic model, reaching  and

and  , marginally outperforming the linear model’s

, marginally outperforming the linear model’s  and

and  . Major improvements are also observed in properties like

. Major improvements are also observed in properties like  ,

,  , and

, and  , where cubic models are able to reproduce nonlinear relationships with

, where cubic models are able to reproduce nonlinear relationships with  more closely. All, barring

more closely. All, barring  ’s cubic fit (p = 0.001), have p-values of 0.000, which highlights their significance statistically. These findings affirm the efficacy of the cubic models to describe the sophisticated thermal behavior of

’s cubic fit (p = 0.001), have p-values of 0.000, which highlights their significance statistically. These findings affirm the efficacy of the cubic models to describe the sophisticated thermal behavior of  ’s characteristics as shown in Fig. 8.

’s characteristics as shown in Fig. 8.

Table 10.

Statistical parameters and regression models for RI(G).

| Property |  |

|

R |  |

|

F |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.930 | 0.864 | 20.056 | 95.447 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.931 | 0.867 | 89.558 | 28.204 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.899 | 0.809 | 3.381 | 63.521 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.913 | 0.833 | 14.266 | 21.568 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.937 | 0.878 | 11.659 | 107.856 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.937 | 0.879 | 52.435 | 31.351 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.991 | 0.981 | 2.366 | 790.034 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.992 | 0.983 | 10.061 | 257.319 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.787 | 0.619 | 11.958 | 24.366 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.855 | 0.731 | 45.345 | 11.748 | 0.001 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.979 | 0.959 | 10.024 | 347.733 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.979 | 0.959 | 44.797 | 102.350 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.989 | 0.978 | 1.001 | 681.344 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.991 | 0.982 | 4.140 | 234.627 | 0.000 |

Fig. 8.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus RI(G).

Table 11 shows the statistical parameters and regression models for material  , which illustrates the thermal index’s impact on various important parameters:

, which illustrates the thermal index’s impact on various important parameters:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Each parameter is considered in terms of both linear and cubic regression models, and model performance is evaluated in terms of the correlation coefficient (

. Each parameter is considered in terms of both linear and cubic regression models, and model performance is evaluated in terms of the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

Table 11.

Statistical parameters and regression models for SC(G).

| Property | Model | Equation | R |  |

SE | F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.934 | 0.872 | 19.321 | 102.152 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.935 | 0.875 | 80.065 | 30.224 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.903 | 0.815 | 3.303 | 65.948 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.915 | 0.837 | 12.991 | 22.182 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.941 | 0.886 | 11.186 | 116.394 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.942 | 0.887 | 46.658 | 33.922 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.991 | 0.981 | 2.364 | 779.329 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.991 | 0.983 | 9.410 | 249.576 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.788 | 0.621 | 11.825 | 24.626 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.852 | 0.726 | 42.144 | 11.469 | 0.001 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.977 | 0.955 | 10.382 | 317.822 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.978 | 0.956 | 42.893 | 94.442 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.989 | 0.978 | 1.003 | 667.601 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.990 | 0.981 | 3.954 | 218.013 | 0.000 |

The cubic models outperform their linear counterparts consistently, with improved fit for all but one property, as indicated by increased values of  and

and  , and decreased standard errors. For instance, the cubic model for

, and decreased standard errors. For instance, the cubic model for  yields

yields  ,

,  , an improvement over the linear model where

, an improvement over the linear model where  ,

,  . Analogously, the property

. Analogously, the property  is very well-captured with the cubic model, with values of

is very well-captured with the cubic model, with values of  ,

,  , as compared with

, as compared with  ,

,  in the linear model. In particular,

in the linear model. In particular,  shows very high correlation in both models, with the cubic model marginally outdoing the linear one (

shows very high correlation in both models, with the cubic model marginally outdoing the linear one ( ,

,  compared to

compared to  ,

,  ). The same trend is seen in characteristics such as

). The same trend is seen in characteristics such as  and

and  , where cubic models do a better job of capturing the nonlinear behavior caused due to thermal effects. All the regression models show high statistical significance with p-values of 0.000 in all cases, except for the cubic model of

, where cubic models do a better job of capturing the nonlinear behavior caused due to thermal effects. All the regression models show high statistical significance with p-values of 0.000 in all cases, except for the cubic model of  , which is statistically significant with a value of 0.001. These observations affirm the robustness and efficacy of cubic models of regression in portraying the complicated thermal behavior of the

, which is statistically significant with a value of 0.001. These observations affirm the robustness and efficacy of cubic models of regression in portraying the complicated thermal behavior of the  material as shown in Fig. 9.

material as shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus SC(G).

Table 12 summarizes the regression models and statistical parameters for the material  , indicating the effect of thermal index (

, indicating the effect of thermal index ( ) on each property:

) on each property:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Both cubic and linear regression models are evaluated for each property, with model performance assessed through the use of the correlation coefficient (

. Both cubic and linear regression models are evaluated for each property, with model performance assessed through the use of the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

Table 12.

Statistical parameters and regression models for SA(G).

| Property |  |

|

R |  |

|

F |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.938 | 0.879 | 18.078 | 109.166 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.939 | 0.882 | 65.335 | 32.304 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.907 | 0.822 | 3.116 | 69.450 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.917 | 0.841 | 10.770 | 22.903 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.945 | 0.893 | 10.432 | 125.174 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.946 | 0.895 | 37.819 | 36.773 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.989 | 0.978 | 2.431 | 681.613 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.990 | 0.981 | 8.388 | 221.224 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.795 | 0.632 | 11.237 | 25.721 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.852 | 0.726 | 35.378 | 11.499 | 0.001 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.974 | 0.949 | 10.605 | 280.989 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.975 | 0.951 | 37.903 | 84.972 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.987 | 0.975 | 1.034 | 581.083 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.989 | 0.977 | 3.585 | 186.649 | 0.000 |

Like with other data sets, the cubic models tend to provide enhanced predictive power compared to the linear models. The improvements are reflected in higher  ,

,  , and decreased standard errors for all but one property. For instance,

, and decreased standard errors for all but one property. For instance,  with the cubic model yields

with the cubic model yields  ,

,  , whereas the linear model yields

, whereas the linear model yields  ,

,  . Particularly, the property

. Particularly, the property  exhibits high predictive power with both models, and the cubic model yields

exhibits high predictive power with both models, and the cubic model yields  ,

,  , which marginally outperforms the linear model’s

, which marginally outperforms the linear model’s  ,

,  . The

. The  property also shows high model fit quality, with the cubic model generating

property also shows high model fit quality, with the cubic model generating  ,

,  , and a lesser

, and a lesser  , capturing the nonlinear relationships of

, capturing the nonlinear relationships of  more accurately. On the other hand, the property

more accurately. On the other hand, the property  shows weaker

shows weaker  values for both models, with the cubic model, though still with increased fit, giving

values for both models, with the cubic model, though still with increased fit, giving  , compared with the linear model

, compared with the linear model  . All of the models are statistically significant with a p-value of 0.000, with the exception of the cubic model for

. All of the models are statistically significant with a p-value of 0.000, with the exception of the cubic model for  , which is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.001. The results validate the application of cubic regression models for precise modeling of

, which is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.001. The results validate the application of cubic regression models for precise modeling of  thermal response as shown in Fig. 10.

thermal response as shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus GA(G).

Table 13 shows the statistical parameters and regression models of the material  , indicating how the thermal index (

, indicating how the thermal index ( ) influences important features like

) influences important features like  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Both linear and cubic models are utilized, with their performance measured in terms of the correlation coefficient (

. Both linear and cubic models are utilized, with their performance measured in terms of the correlation coefficient ( ), coefficient of determination (

), coefficient of determination ( ), standard error (

), standard error ( ), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

), F-statistic (F), and p-value.

Table 13.

Statistical parameters and regression models for HZ(G).

| Property | Models | Equations | R |  |

|

F |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Linear |  |

0.929 | 0.863 | 16.860 | 94.822 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.936 | 0.875 | 48.017 | 30.426 | 0.000 | |

| EV | Linear |  |

0.920 | 0.846 | 2.545 | 82.330 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.920 | 0.846 | 7.581 | 23.835 | 0.000 | |

| FP | Linear |  |

0.934 | 0.872 | 10.020 | 101.879 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.948 | 0.898 | 26.640 | 38.118 | 0.000 | |

| MR | Linear |  |

0.957 | 0.916 | 4.202 | 164.460 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.965 | 0.932 | 11.310 | 59.250 | 0.000 | |

| SA | Linear |  |

0.869 | 0.754 | 8.047 | 46.088 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.893 | 0.798 | 21.781 | 17.069 | 0.000 | |

| MV | Linear |  |

0.942 | 0.888 | 13.839 | 118.711 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.946 | 0.895 | 39.962 | 36.835 | 0.000 | |

| P | Linear |  |

0.952 | 0.906 | 1.750 | 145.028 | 0.000 |

| Cubic |  |

0.960 | 0.922 | 4.752 | 51.353 | 0.000 |

Cubic models tend to show enhanced predictive accuracy compared to linear models with higher  and

and  values along with lower standard errors for many of the properties. For instance, while the cubic model for

values along with lower standard errors for many of the properties. For instance, while the cubic model for  shows

shows  and

and  , an improvement over the linear model’s values of

, an improvement over the linear model’s values of  and

and  , the cubic model does well with

, the cubic model does well with  ,

,  , and lower

, and lower  for

for  , reflecting improved capture of the non-linear thermal characteristics. The parameter

, reflecting improved capture of the non-linear thermal characteristics. The parameter  also exhibits high agreement under both models, with the cubic model returning

also exhibits high agreement under both models, with the cubic model returning  ,

,  , very slightly higher than the linear model’s

, very slightly higher than the linear model’s  ,

,  .

.  also shows high agreement under both models, though with the cubic fit returning higher predictive accuracy (

also shows high agreement under both models, though with the cubic fit returning higher predictive accuracy ( ,

,  ). All models have excellent statistical significance, with all the p-values at 0.000, further supporting the application of cubic models to express the intricate thermal dependences of the

). All models have excellent statistical significance, with all the p-values at 0.000, further supporting the application of cubic models to express the intricate thermal dependences of the  material’s properties. These findings confirm that cubic regression models are more accurate and reliable in the description of the thermal response behavior for this material as shown in Fig. 11.

material’s properties. These findings confirm that cubic regression models are more accurate and reliable in the description of the thermal response behavior for this material as shown in Fig. 11.

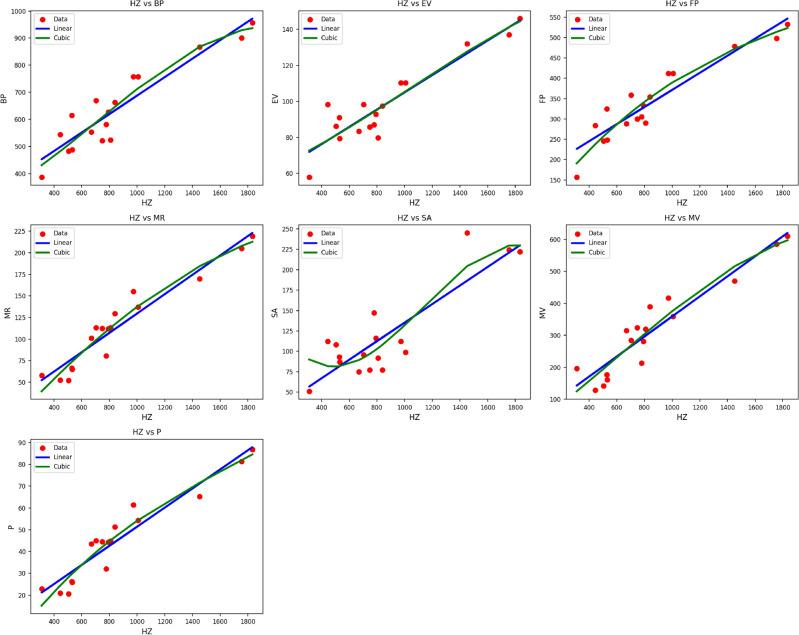

Fig. 11.

Scatter plots of actual data points (red) and regression model fits (linear in blue, cubic in green) for various drug response parameters versus HZ(G).

Table 14 displays an exhaustive comparison of observed and calculated Boiling Point (BP) values under different experimental conditions. Both cubic and linear regression models were utilized to predict BP as a function of the independent variable  . The data for actual BP reflects great variability throughout the experiments, reflecting the complicated physiological character of such response variables. The cubic model of regression always displays the best fit with the data, with the predicted values closest to actual measures, particularly in the cases of higher or lower values. This increased correspondence indicates that

. The data for actual BP reflects great variability throughout the experiments, reflecting the complicated physiological character of such response variables. The cubic model of regression always displays the best fit with the data, with the predicted values closest to actual measures, particularly in the cases of higher or lower values. This increased correspondence indicates that  is not linearly correlated with BP, and hence, the cubic model is more effective in accommodating these fluctuations. The linear model, in contrast, does reasonably well but under- or over-estimates where the data are curved. The residuals in these areas point to where the assumption of a straightforward linear dependency in BP prediction may fall short. In total, the analysis verifies that, in the case of BP, the use of a higher-order polynomial model, i.e., cubic regression, yields more accurate prediction. This indicates that BP responses depend upon several interacting variables, which are best described through non-linear methods.

is not linearly correlated with BP, and hence, the cubic model is more effective in accommodating these fluctuations. The linear model, in contrast, does reasonably well but under- or over-estimates where the data are curved. The residuals in these areas point to where the assumption of a straightforward linear dependency in BP prediction may fall short. In total, the analysis verifies that, in the case of BP, the use of a higher-order polynomial model, i.e., cubic regression, yields more accurate prediction. This indicates that BP responses depend upon several interacting variables, which are best described through non-linear methods.

Table 14.

Comparison of actual and predicted drug response values for BP.

| Index | Equation |  |

S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | BP | 614 | 487.8 | 758.1 | 523.3 | 521.1 | 668.9 | 627.2 | 553.6 | 757 | 386.5 | 543.7 | 900.5 | 957.1 | 867.7 | 581.8 | 662.3 | 482.7 |

|

Linear | 518.6 | 518.6 | 697.3 | 630.3 | 604.2 | 596.8 | 622.8 | 589.3 | 701.0 | 444.1 | 488.8 | 931.9 | 969.1 | 842.5 | 589.3 | 645.2 | 503.7 |

| Cubic | 511.5 | 511.5 | 711.9 | 635.1 | 605.3 | 596.8 | 626.6 | 588.4 | 716.1 | 440.6 | 481.6 | 926.0 | 943.8 | 861.1 | 588.4 | 652.2 | 496.3 | |

|

Linear | 525.0 | 526.5 | 694.9 | 615.9 | 602.5 | 592.1 | 618.9 | 580.1 | 684.4 | 444.5 | 493.7 | 937.7 | 976.5 | 840.9 | 612.9 | 636.8 | 510.1 |

| Cubic | 515.1 | 516.8 | 717.1 | 622.7 | 606.5 | 593.9 | 626.3 | 579.6 | 704.9 | 430.0 | 480.4 | 928.0 | 940.1 | 866.7 | 619.1 | 647.9 | 498.3 | |

| H | Linear | 502.6 | 503.4 | 709.1 | 638.8 | 611.4 | 616.9 | 627.2 | 628.8 | 743.1 | 449.9 | 477.2 | 897.5 | 957.0 | 832.9 | 551.6 | 663.7 | 482.1 |

| Cubic | 505.0 | 505.5 | 705.2 | 627.0 | 598.5 | 604.1 | 614.8 | 616.5 | 744.3 | 475.5 | 489.2 | 911.2 | 962.0 | 845.6 | 542.5 | 654.1 | 492.1 | |

| F | Linear | 527.8 | 527.8 | 684.9 | 627.1 | 600.7 | 581.8 | 614.5 | 570.5 | 672.4 | 458.7 | 501.4 | 950.2 | 967.8 | 842.1 | 610.8 | 629.6 | 525.3 |

| Cubic | 516.1 | 516.1 | 711.2 | 641.1 | 608.1 | 584.3 | 625.4 | 570.0 | 696.3 | 431.5 | 483.3 | 929.3 | 934.1 | 868.8 | 620.7 | 644.2 | 513.0 | |

| SS | Linear | 513.4 | 513.7 | 705.1 | 631.0 | 605.9 | 607.1 | 626.9 | 603.0 | 717.6 | 439.5 | 482.0 | 918.2 | 967.9 | 838.9 | 577.3 | 653.9 | 491.8 |

| Cubic | 508.9 | 509.2 | 713.0 | 629.6 | 602.0 | 603.4 | 625.1 | 598.9 | 727.1 | 450.0 | 481.8 | 921.1 | 951.6 | 854.8 | 571.6 | 655.2 | 489.9 | |

| ABC | Linear | 512.5 | 512.0 | 698.6 | 640.6 | 607.2 | 603.0 | 625.6 | 602.1 | 719.4 | 445.6 | 484.9 | 921.3 | 962.7 | 840.6 | 567.6 | 652.8 | 496.5 |

| Cubic | 509.5 | 509.0 | 704.1 | 640.7 | 604.7 | 600.3 | 624.4 | 599.3 | 726.8 | 452.3 | 484.7 | 921.9 | 951.1 | 852.1 | 563.4 | 654.0 | 494.9 | |

| RI | Linear | 504.5 | 504.8 | 702.8 | 640.9 | 611.6 | 609.2 | 624.9 | 620.5 | 735.6 | 451.7 | 481.2 | 906.6 | 957.9 | 837.9 | 555.3 | 659.0 | 488.7 |

| Cubic | 505.9 | 506.2 | 701.0 | 633.4 | 602.9 | 600.5 | 616.6 | 612.0 | 737.6 | 470.3 | 489.0 | 915.6 | 958.0 | 848.8 | 548.5 | 652.9 | 494.2 | |

| SC | Linear | 506.9 | 507.2 | 706.5 | 638.0 | 609.2 | 612.3 | 627.3 | 617.6 | 733.4 | 445.7 | 479.3 | 907.1 | 960.9 | 836.0 | 559.7 | 659.9 | 486.5 |

| Cubic | 506.5 | 506.7 | 706.8 | 631.1 | 600.8 | 604.0 | 619.7 | 609.5 | 736.9 | 465.0 | 486.1 | 915.8 | 958.0 | 848.3 | 552.0 | 654.9 | 491.2 | |

| SA | Linear | 509.5 | 509.9 | 708.6 | 633.9 | 607.3 | 613.1 | 628.5 | 613.3 | 728.9 | 440.6 | 478.6 | 909.0 | 964.5 | 835.8 | 566.6 | 659.2 | 485.9 |

| Cubic | 507.2 | 507.6 | 711.6 | 628.3 | 599.9 | 606.0 | 622.5 | 606.2 | 734.5 | 459.0 | 483.5 | 916.9 | 956.8 | 849.8 | 558.7 | 656.1 | 488.8 | |

| HZ | Linear | 526.4 | 527.1 | 689.5 | 622.0 | 601.5 | 586.5 | 616.5 | 574.9 | 677.9 | 452.0 | 497.7 | 944.8 | 972.1 | 841.7 | 611.7 | 632.9 | 518.2 |

| Cubic | 515.6 | 516.5 | 714.0 | 632.6 | 607.4 | 588.9 | 625.9 | 574.6 | 700.3 | 430.3 | 481.8 | 928.9 | 936.7 | 868.0 | 620.0 | 646.0 | 505.9 |

Table 15 contains the observed and calculated values of Enthalpy of Vaporization (EV) with linear and cubic models. In contrast to BP, there is a consistent and stable trend in the EV values in the experiments. Both the linear and cubic models have close agreement with the actual EV values. Yet, there is little difference between the models, indicating that the relationship of  and EV is mostly linear. The linear model makes very consistent predictions with little variation from the actual values, and it is an efficient and interpretable model to use for EV. Although the cubic model does add some flexibility, the performance improvement it offers in this application is marginal. This indicates that the increased complexity may not be justified, particularly in light of the model parsimony principle.

and EV is mostly linear. The linear model makes very consistent predictions with little variation from the actual values, and it is an efficient and interpretable model to use for EV. Although the cubic model does add some flexibility, the performance improvement it offers in this application is marginal. This indicates that the increased complexity may not be justified, particularly in light of the model parsimony principle.

Table 15.

Comparison of actual and predicted drug response values for EV.

| Index | Equation |  |

S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | EV | 91.1 | 79.4 | 110.4 | 79.7 | 85.8 | 98.3 | 92.8 | 83.4 | 110.3 | 57.9 | 98.2 | 137.1 | 146 | 132.1 | 87 | 97.4 | 86.2 |

|

Linear | 81.4 | 81.4 | 106.3 | 97.0 | 93.3 | 92.3 | 95.9 | 91.2 | 106.8 | 71.0 | 77.2 | 139.0 | 144.2 | 126.5 | 91.2 | 99.0 | 79.3 |

| Cubic | 81.8 | 81.8 | 105.1 | 95.7 | 92.3 | 91.3 | 94.7 | 90.4 | 105.7 | 74.3 | 78.6 | 140.3 | 145.8 | 126.8 | 90.4 | 97.8 | 80.2 | |

|

Linear | 82.2 | 82.4 | 106.0 | 94.9 | 93.1 | 91.6 | 95.3 | 89.9 | 104.5 | 70.9 | 77.8 | 140.0 | 145.5 | 126.5 | 94.5 | 97.9 | 80.1 |

| Cubic | 82.1 | 82.3 | 105.9 | 94.4 | 92.6 | 91.1 | 94.9 | 89.5 | 104.4 | 72.6 | 78.3 | 140.6 | 145.3 | 127.4 | 94.0 | 97.4 | 80.3 | |

| H | Linear | 79.5 | 79.6 | 107.8 | 98.1 | 94.4 | 95.2 | 96.6 | 96.8 | 112.4 | 72.3 | 76.1 | 133.5 | 141.7 | 124.7 | 86.2 | 101.6 | 76.7 |

| Cubic | 81.3 | 81.4 | 104.4 | 94.1 | 90.6 | 91.3 | 92.6 | 92.8 | 110.0 | 79.9 | 80.3 | 137.7 | 148.1 | 125.9 | 84.6 | 97.5 | 80.5 | |

| F | Linear | 82.5 | 82.5 | 104.6 | 96.5 | 92.8 | 90.1 | 94.7 | 88.5 | 102.9 | 72.7 | 78.7 | 142.1 | 144.6 | 126.8 | 94.2 | 96.8 | 82.1 |

| Cubic | 82.2 | 82.2 | 105.2 | 96.6 | 92.7 | 90.0 | 94.8 | 88.3 | 103.4 | 72.7 | 78.5 | 141.7 | 143.7 | 127.9 | 94.2 | 97.0 | 81.8 | |

| SS | Linear | 80.8 | 80.9 | 107.3 | 97.1 | 93.6 | 93.8 | 96.5 | 93.2 | 109.0 | 70.6 | 76.5 | 136.8 | 143.6 | 125.8 | 89.6 | 100.2 | 77.8 |

| Cubic | 81.6 | 81.6 | 105.3 | 94.9 | 91.7 | 91.9 | 94.4 | 91.4 | 107.1 | 75.9 | 78.9 | 139.1 | 147.1 | 126.2 | 88.3 | 98.0 | 79.7 | |

| ABC | Linear | 80.7 | 80.6 | 106.4 | 98.4 | 93.8 | 93.2 | 96.3 | 93.1 | 109.3 | 71.4 | 76.8 | 137.3 | 143.0 | 126.1 | 88.3 | 100.1 | 78.4 |

| Cubic | 81.7 | 81.7 | 104.1 | 96.2 | 92.0 | 91.5 | 94.3 | 91.4 | 107.1 | 76.1 | 79.2 | 139.6 | 146.8 | 126.0 | 87.4 | 97.8 | 80.2 | |

| RI | Linear | 79.7 | 79.7 | 107.0 | 98.4 | 94.4 | 94.1 | 96.2 | 95.6 | 111.5 | 72.4 | 76.5 | 135.0 | 142.0 | 125.5 | 86.7 | 100.9 | 77.5 |

| Cubic | 81.4 | 81.5 | 103.8 | 95.0 | 91.3 | 91.1 | 93.0 | 92.4 | 108.9 | 79.0 | 80.1 | 138.5 | 147.6 | 126.3 | 85.4 | 97.4 | 80.5 | |

| SC | Linear | 80.0 | 80.1 | 107.5 | 98.0 | 94.1 | 94.5 | 96.6 | 95.2 | 111.1 | 71.6 | 76.2 | 135.0 | 142.4 | 125.2 | 87.3 | 101.0 | 77.2 |

| Cubic | 81.4 | 81.4 | 104.5 | 94.8 | 91.2 | 91.6 | 93.4 | 92.2 | 108.7 | 78.2 | 79.7 | 138.4 | 147.7 | 125.9 | 85.8 | 97.8 | 80.1 | |

| SA | Linear | 80.4 | 80.4 | 107.7 | 97.5 | 93.8 | 94.6 | 96.7 | 94.6 | 110.5 | 70.9 | 76.1 | 135.3 | 142.9 | 125.2 | 88.2 | 100.9 | 77.1 |

| Cubic | 81.4 | 81.5 | 105.2 | 94.6 | 91.3 | 92.0 | 93.9 | 92.0 | 108.3 | 77.4 | 79.3 | 138.4 | 147.7 | 125.8 | 86.7 | 98.0 | 79.7 | |

| HZ | Linear | 82.3 | 82.4 | 105.3 | 95.8 | 92.9 | 90.8 | 95.0 | 89.1 | 103.6 | 71.9 | 78.3 | 141.2 | 145.0 | 126.7 | 94.3 | 97.3 | 81.2 |

| Cubic | 82.2 | 82.3 | 105.6 | 95.6 | 92.7 | 90.5 | 94.8 | 88.9 | 103.8 | 72.6 | 78.4 | 141.2 | 144.5 | 127.7 | 94.1 | 97.2 | 81.1 |

Table 16 illustrates the comparison of observed with fitted values of Flash Point (FP) with linear and cubic models. The observed FP values indicate moderate variability, indicating possible non-linearity in the relationship between FP and the independent variable  . The cubic regression model’s projections tend to be closer to the true values compared to the linear model. This is especially because, where FP takes mid-to-high values, the linear model will tend to over-simplify the trend. The cubic model can accommodate slight curvatures in the data due to its flexibility, leading to decreased prediction errors. The linear model, although easier to interpret and more straightforward, is seen to underperform in some experiments, especially at the boundaries of the value range. This highlights the necessity of looking into higher-order models whenever the data show non-linear behavior. In brief, the FP analysis shows that the cubic regression yields more precise projections and more accurately reflects the underlying dynamics of the response variable than the linear model.