Abstract

Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 is a new biomarker linked to circulatory failure prognosis and pathophysiology and is a potential actionable therapeutic target. In this short review intended for the clinician, a question-and-answer format provides key insights on the nature of this biomarker and the therapeutical potential of its targeted inhibition in critically ill patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-025-05545-x.

Keywords: Dipeptidyl peptidase 3, Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, Sepsis, Septic shock, Circulatory failure, Angiotensin II, Cardiogenic shock

Introduction

Recent studies have demonstrated that dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3), a cytosolic protein, only present in the plasma of healthy individuals in low concentration become elevated in critically ill patients, particularly those experiencing circulatory failure [1–6]. Most of the available evidence pertains to septic and cardiogenic shock. In these conditions, elevated circulating DPP3 (cDPP3) concentration, with various cut-offs ranging from 40 to 60 ng/mL has been associated with an increased need for cardiovascular support (vasopressors, inotropes and/or mechanical circulatory support), renal replacement therapy, and impaired survival [3–6]. Beyond its role as a biomarker, growing evidence suggests that cDPP3 may play a pathogenic role in acute conditions by triggering or perpetuating circulatory and renal failure. Consequently, inhibition of cDPP3 may exert therapeutic efficacy. Procizumab, the first-in-class DPP3-inhibiting monoclonal antibody, is currently undergoing clinical evaluation. In this short review intended for clinicians, we outline in a question-and-answer format, ten key points that aim to enhance the understanding of this protein and, in the era of precision medicine, provide insights into the development of a targeted therapy designed for critically ill patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Current understanding of the mode of action of cDPP3 and procizumab in circulatory failure. The upper part of the figure illustrates the pathogenic effects of high cDPP3, which excessively cleave angiotensin II, contributing to vasodilation, hypotension, and acute kidney injury. The lower part depicts the therapeutic action of procizumab, which inhibits cDPP3 activity, preserves angiotensin II, thereby stabilizing systemic and renal hemodynamics. (c)DPP3: (circulating) dipeptidyl peptidase 3

Question 1: What is DPP3?

DPP3 is an 83-kDa zinc-dependent aminopeptidase ubiquitously expressed across various cell types and highly conserved among species. It is predominantly localized within the cytoplasm, where it exerts non-enzymatic antioxidant activity via the NRF2-antioxidant response element pathway. Additionally, its enzymatic broad-spectrum cleavage ability implicates it in intracellular peptide catabolism and amino acid turnover. Recent evidence has identified DPP3 in several body fluids, including amniotic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and plasma, where it is referred to as circulating DPP3 (cDPP3) [7–9]. The mechanisms underlying the extracellular release of DPP3 remain insufficiently explored. Notably, the primary structure of DPP3 lacks both a signal peptide and a transmembrane domain that would typically argue for an extracellular release. Current hypotheses suggest a link between cell death and cDPP3 release, a notion supported by the observed association between cDPP3 concentration and markers of cell lysis, such as aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase [10, 11].

Question 2: Is cDPP3 enzymatically active?

In humans, a perfect correlation has been observed between cDPP3 concentration and enzymatic activity across both health and disease. This finding supports the notion that cDPP3 is released in its active form and retains its proteolytic function within the bloodstream [3, 6]. Consequently, in humans, measuring cDPP3 concentration or activity provides similar information.

Question 3: What are the known substrates of cDPP3?

DPP3 is an exo-aminopeptidase that cleaves dipeptides from the N-terminal end of various oligopeptides, typically ranging from 3 to 10 amino acids in length. The enzyme preferentially cleaves dipeptides such as Arg-Arg, Ala-Arg, Asp-Arg, and Tyr-Gly [12]. Cleavage of its natural substrates appears to be maximal at physiological pH (7.0-7.5) [7, 13]. Among its key physiological substrates, DPP3 degrades angiotensin II into angiotensin IV [3–8], which is further cleaved into a tetrapeptide [5–8] with no currently identified biological activity [14–16]. DPP3 also degrades angiotensin III [2–8], angiotensin [1–7], and angiotensin 1–5 [15–19]. Additionally, DPP3 cleaves endogenous opioids, including enkephalins and endomorphins (Table 1) [20, 21]. Finally, the synthetic substrate Arg-Arg-β-naphthylamide is frequently used to measure DPP3 activity in vitro, as its hydrolysis releases a fluorescent β-naphthylamide moiety [9].

Table 1.

Key DPP3 substrates of interest in human physiology

| Substrat | Amino-acid sequence | References |

|---|---|---|

| Angiotensins | ||

| Angiotensin II (1–8) | Asp-Arg↓Val-Tyr↓Ile-His-Pro-Phe | [14–16] |

| Angiotensin III (2–8) | Arg-Val↓Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe | [19] |

| Angiotensin IV (3–8) | Val-Tyr↓Ile-His-Pro-Phe | [14] |

| Angiotensin (1–7) | Asp-Arg↓Val-Tyr↓Ile-His-Pro | [15] |

| Angiotensin (1–5) | Asp-Arg↓Val-Tyr-Ile | [15] |

| Enkephalins | ||

| Met-enkephalin | Tyr-Gly↓Gly-Phe-Met | [21] |

| Leu-enkephalin | Tyr-Gly↓Gly-Phe-Leu | [20] |

| Endomorphins | ||

| Endomorphin-1 | Tyr-Pro↓Trp-Phe-NH2 | [20] |

| Endomorphin-2 | Tyr-Pro↓Phe-Phe-NH2 | [20] |

The arrow (↓) indicates the identified cleavage site(s). It is important to note that except for angiotensin peptides, DPP3 substrates have been identified solely in ex vivo experiments. The ability of DPP3 to cleave enkephalin and endomorphins ex vivo does not constitute a definitive proof of its involvement in the metabolism of these peptides in vivo

Question 4: What is the normal concentration of cDPP3 in healthy individuals?

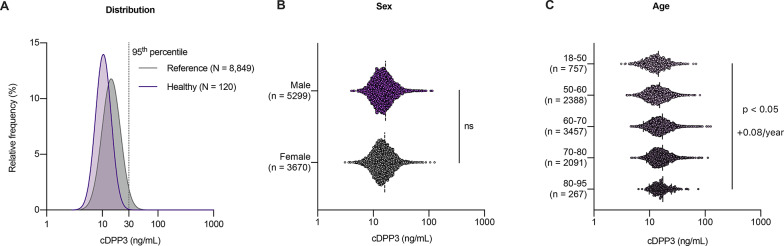

To date, cDPP3 concentrations have been measured in over 8,000 ambulatory individuals. These concentrations appear unaffected by sex (p = 0.20) and only minimally influenced by age (r = 0.12, p < 0.05, + 0.08 ng/mL/year) (Fig. 2). Among individuals without any detectable pathology nor treatment, the median cDPP3 concentration is approximately 10 ng/mL, with the 95th percentile reaching 19 ng/mL. In cohorts more representative of patients likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) (i.e., general populations of older individuals without an acute disease but with potential chronic comorbidities) [22, 23], the median cDPP3 concentration is 15 ng/mL, with the 95th percentile at 30 ng/mL. Pragmatically, in an ICU-like population, a baseline (i.e., out-of-hospital, non-acute) cDPP3 concentration below 30 ng/mL can be expected.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (cDPP3) concentration across cohorts of ambulatory individuals with relative frequency indicating the proportion of individual in each population with a given cDPP3 concentration (A), influence of sex (B) and age (C). The “healthy” population (n = 120) consists of individuals who are free of detectable pathology and are not receiving any medication. The “reference” population (n = 8,849) includes ambulatory individuals who may present with comorbidities and chronic treatments, reflecting the baseline characteristics of patients likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. Details about cohorts included in this analysis can be found in the supplemental table. cDPP3: circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3

Question 5: How could cDPP3 be implicated in the pathogenesis of circulatory failure?

Given its role in degrading angiotensin II and other angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) agonists (angiotensin III and IV), cDPP3 may contribute to dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and impaired AT1R signaling, thereby contributing to systemic vasodilation and hypotension [16, 24, 25]. Additionally, impaired AT1R signaling may contribute to acute kidney injury by the preferential loss of glomerular efferent arteriole tone, thereby decreasing glomerular capillary pressure and ultimately glomerular filtration rate [16, 24]. High cDPP3 has been associated with decreased systemic and renal vasoreactivity to angiotensin II, a finding that could explain why some patients have a poor hemodynamic response to exogenous angiotensin II [26, 27]. Interestingly, high cDPP3 induces the typical RAAS alterations that have been associated with the prognosis of circulatory failure patients. As cDPP3 hydrolyses angiotensin II but not angiotensin I, its elevation is associated with an increase of the angiotensin I/angiotensin II ratio [16, 25, 28, 29]. Furthermore, cDPP3-mediated hydrolysis of angiotensin II triggers renin release, in a known bio-feedback mechanism due to attenuated AT1R stimulation on juxtaglomerular cells [16, 25, 30].

It is noteworthy that elevated cDPP3 concentrations have been observed in patients suffering from circulatory failure of diverse etiologies. Thus, one can hypothesize that the release of cDPP3, potentially triggered by tissue hypoperfusion and cell death, may be a secondary insult precipitating or perpetuating circulatory failure by exacerbating vasodilation, suggesting that this pathogenic mechanism could be implicated in all shock states with a vasodilatory component [31]. While the role of cDPP3 in angiotensin II cleavage is well established, the implications of its activity on other peptides in the pathophysiology of circulatory failure warrants further investigation. Notably, DPP3 administration in mice transiently alters left ventricular function while cDPP3 inhibition has been associated with improved cardiac function in murine models of acute cardiac stress [3, 32]. Whether these effects reflect RAAS modulation remains elusive.

Question 6: Can cDPP3 be directly targeted in patients with circulatory failure?

Procizumab is a monoclonal immunoglobulin-G kappa antibody targeting cDPP3, initially used in mechanistic studies and currently being developed as a therapeutic agent for circulatory failure. In a porcine model of septic shock, procizumab, administered on top of standard resuscitation at shock onset, was associated with a reduced need for catecholamine support, lower lactate, decreased myocardial workload, and protection against myocardial injury. Additionally, fluid balance, and oxygenation were improved compared to standard resuscitation without procizumab [29]. This work strongly suggests that cDPP3 can be effectively targeted in circulatory failure. Ongoing research is evaluating its therapeutic potential in a porcine model of post-myocardial infarction circulatory failure.

Question 7: What are the expected benefits and risks of cDPP3 modulation?

Based on the current understanding of the mechanisms of action of cDPP3 and procizumab, administration of procizumab is expected to primarily stabilize hemodynamics by inhibiting cDPP3-mediated angiotensin II degradation. This, in turn, increases systemic vascular resistance, reduces the need for exogenous catecholamines, and improves organ perfusion and function. Additional benefits may arise from the accumulation of other cDPP3 substrates (e.g., angiotensin- [1–7], angiotensin- [1–5]).

Interestingly, procizumab does not completely abolish cDPP3 activity [16, 29], allowing for residual enzymatic function, theoretically mitigating the risks associated with excessive inhibition and the potential suppression of any physiological role. Additionally, as procizumab is an antibody, its volume of distribution is largely confined to the bloodstream, thereby avoiding interference with intracellular DPP3 and its antioxidant activity. In a phase I trial in healthy male volunteers (EU trial number: 2023-507035-37-00), procizumab up to the dose of 12 mg/kg exhibited an excellent safety profile without any serious adverse events. Interestingly, procizumab exhibited a relatively short half-life compared to other monoclonal IgG antibodies (terminal elimination half-life of ~ 53 h) which could be a characteristic of the antibody or caused by target mediated drug disposition, with procizumab-DPP3 complexes tending towards rapid clearance kinetics, as observed for cDPP3 [3]. This characteristic could reduce the risk of excessive inhibition of a potential physiological cDPP3 activity.

Question 8: What would be the optimal cDPP3 cut-off indicating procizumab treatment?

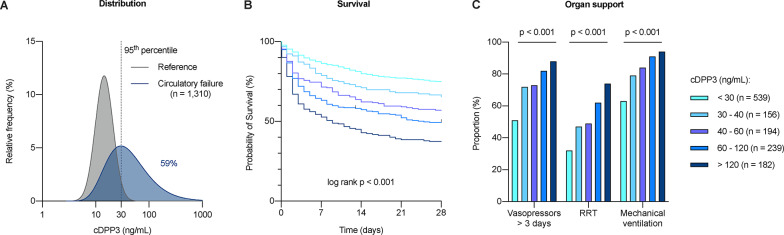

A meta-analysis from seven European cohorts of cardiogenic and septic shock patients [33–38] clearly demonstrates that as soon as cDPP3 concentrations exceed physiological values (i.e., the 95th percentile of an ICU-like population − 30 ng/mL), prognosis progressively worsens. Patients with elevated cDPP3 are more likely to need organ support and exhibit a steadily rising mortality rate with similar findings in the cardiogenic shock and septic shock subgroups (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, from a clinical, prognostic perspective, a continuous and monotonic relationship can be established between cDPP3 concentration and patient outcomes. Simply put, the higher the cDPP3 concentration, the worse the prognosis. Hence, prognostic enrichment could be achieved by selecting patients based on a cDPP3 cut-off of 30 ng/mL or higher, with expected more pronounced therapeutic efficacy in patients with the highest concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (cDPP3) concentration and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with circulatory failure, based on a meta-analysis of seven studies (1,310 patients): relative frequency of individuals in each populations with a given cDPP3 concentration, and proportion (%) of patients higher than the 30 ng/ml cut-off corresponding to the 95th percentile of a reference population (A), survival (B) and need for organ support (C) according to cDPP3. Patients who did not survive were systematically categorized as having required organ support. Details about cohorts included in this analysis can be found in the supplemental table. cDPP3: circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3; RRT: Renal replacement therapy

Question 9: What are the challenges in developing a cDPP3-targeted therapy?

Although procizumab has demonstrated safety in healthy individuals, several challenges must be addressed to optimize its potential to improve outcomes in critically ill patients.

First, the target patient phenotype must be precisely defined. While elevated cDPP3 appears to be a relatively common phenomenon in circulatory failure, affecting 40–70% of patients, inhibiting cDPP3 may not provide the same benefit to all of them. For instance, increasing vascular resistance is likely beneficial in predominantly vasodilatory shock but could potentially negatively impact cardiac function in isolated cardiogenic shock. Conversely, it is currently uncertain whether the etiology of shock plays a role in therapeutic response. Moreover, it remains to be elucidated if the presence of pathogenic vasodilation associated with elevated cDPP3 is sufficient to define a population likely to benefit from procizumab therapy. Second, the therapeutic time window for cDPP3 modulation must be precisely determined. While this window is likely within the early phases of critical care management, it is of upmost importance to establish the optimal timing for treatment initiation and the optimal duration of DPP3 inhibition. Given the relatively short half-life of the antibody, maintaining adequate therapeutic coverage may require repeated administrations. These questions will be investigated in a phase 1b trial (ProCARD-1b).

Question 10: How can we formally demonstrate the predictive enrichment value of a cDPP3 measurement?

For therapeutic purposes, it is crucial to establish a clear cut-off to answer the dichotomic question of whether the treatment should be administered. Logically, patients with the highest activation of the pathogenic pathway, reflected by the greatest elevation in cDPP3, might be the most likely to benefit from targeted cDPP3 inhibition, whereas patients with little to no elevation of cDPP3 may not derive a benefit from the treatment and could potentially experience adverse effects. However, from a pragmatic standpoint, the choice of cut-off must balance the likelihood of significantly altering patient trajectories with considerations related to patient recruitment and the objective of making the treatment accessible to the largest possible number of patients. As an illustration, a cut-off of cDPP3 > 30 ng/mL selects approximately 59% of patients with circulatory failure, whereas the 40 ng/mL cut-off, the most used cut-off in the prognostic literature, would select only 47% of patients. For this reason, the ProCARD-1b study will include patients with shock of septic or post-myocardial infarction origin and a “supraphysiological” cDPP3 concentration (cDPP3 > 30 ng/mL). Secondary analyses of this trial and subsequent studies will explore the heterogeneity of treatment effects based on cDPP3 concentration and may lead to a refinement of this operational cut-off. The identification of a cDPP3 concentration predictive of response to procizumab will formally demonstrate the biomarker’s ability to achieve predictive enrichment.

Conclusion

cDPP3 is a promising biomarker linked to the pathophysiology of circulatory failure and impaired patient prognosis. Ongoing studies are now exploring the therapeutic potential of targeted cDPP3 inhibition in humans.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- (c)DPP3

(circulating) dipeptidyl peptidase 3

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- RAAS

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

Author contributions

All the authors listed meet the authorship criteria. AP wrote the initial version of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AP reports having received research grants from the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française (SRLF), the Société Française d’Anesthésie Réanimation (SFAR), the Zoll Fondation, the Fonds pour la chirurgie cardiaque and 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals GmbH. MK is supported by the Else Kroener-Fresenius-Stiftung (W3 Else Kroener Clinician Scientist Professorship). He reports grant and non-financial support from Adrenomed AG and CSL Vifor, as well as personal fees from Adrenomed AG, Sphingotec GmbH, CSL Vifor, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pharmacosmos and 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals GmbH. PP has received research grants, travel and consultancy reimbursements from 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals GmbH. UZ received speaker honoraria form 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals. KS is employed as chief scientific officer at 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals GmbH. AM reports personal fees from Orion, Roche, Adrenomed and Fire 1, and grants and personal fees from 4TEEN4 Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Abbott, Roche, and Sphingotec GmbH.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Deniau B, Picod A, Van Lier D, Vaittinada Ayar P, Santos K, Hartmann O, et al. High plasma dipeptidyl peptidase 3 levels are associated with mortality and organ failure in shock: results from the international, prospective and observational FROG-ICU cohort. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(2):e54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dépret F, Amzallag J, Pollina A, Fayolle-Pivot L, Coutrot M, Chaussard M, et al. Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase-3 at admission is associated with circulatory failure, acute kidney injury and death in severely ill burn patients. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2020;24(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deniau B, Rehfeld L, Santos K, Dienelt A, Azibani F, Sadoune M, et al. Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 is a myocardial depressant factor: dipeptidyl peptidase 3 Inhibition rapidly and sustainably improves haemodynamics. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(2):290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takagi K, Blet A, Levy B, Deniau B, Azibani F, Feliot E, et al. Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 and alteration in haemodynamics in cardiogenic shock: results from the OptimaCC trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(2):279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picod A, Nordin H, Jarczak D, Zeller T, Oddos C, Santos K, et al. High Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 predicts mortality and need for organ support in cardiogenic shock: an ancillary analysis of the ACCOST-HH trial. J Card Fail. 2025;31(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blet A, Deniau B, Santos K, van Lier DPT, Azibani F, Wittebole X, et al. Monitoring Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3) predicts improvement of organ failure and survival in sepsis: a prospective observational multinational study. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2021;25(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimamori Y, Watanabe Y, Fujimoto Y. Human placental dipeptidyl aminopeptidase III: hydrolysis of enkephalins and its stimulation by cobaltous ion. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1988;40(3):305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato H, Kimura K, Yamamoto Y, Hazato T. [Activity of DPP III in human cerebrospinal fluid derived from patients with pain]. Masui. 2003;52(3):257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehfeld L, Funk E, Jha S, Macheroux P, Melander O, Bergmann A. Novel methods for the quantification of dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3) concentration and activity in human blood samples. J Appl Lab Med. 2019;3(6):943–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Lier D, Beunders R, Kox M, Pickkers P. Associations of dipeptidyl-peptidase 3 with short-term outcome in a mixed admission ICU-cohort. J Crit Care. 2023;78:154383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Lier D, Deniau B, Santos K, Hartmann O, Dudoignon E, Depret F, et al. Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 3 and bio-adrenomedullin levels are associated with impaired outcomes in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a prospective international multicentre study. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(1):00342–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malovan G, Hierzberger B, Suraci S, Schaefer M, Santos K, Jha S, et al. The emerging role of dipeptidyl peptidase 3 in pathophysiology. FEBS J. 2023;290(9):2246–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abramić M, Zubanović M, Vitale L. Dipeptidyl peptidase III from human erythrocytes. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1988;369(1):29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang X, Shimizu A, Kurita S, Zankov DP, Takeuchi K, Yasuda-Yamahara M, et al. Novel therapeutic role for dipeptidyl peptidase III in the treatment of hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jha S, Taschler U, Domenig O, Poglitsch M, Bourgeois B, Pollheimer M, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 3 modulates the renin-angiotensin system in mice. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(40):13711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picod A, Placier S, Genest M, Callebert J, Julian N, Zalc M et al. Circulating Dipeptidyl Peptidase 3 Modulates Systemic and Renal Hemodynamics Through Cleavage of Angiotensin Peptides. Hypertens Dallas Tex. 1979. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cruz-Diaz N, Wilson BA, Pirro NT, Brosnihan KB, Marshall AC, Chappell MC. Identification of dipeptidyl peptidase 3 as the Angiotensin-(1-7) degrading peptidase in human HK-2 renal epithelial cells. Peptides. 2016;83:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abramić M, Schleuder D, Dolovcak L, Schröder W, Strupat K, Sagi D, et al. Human and rat dipeptidyl peptidase III: biochemical and mass spectrometric arguments for similarities and differences. Biol Chem. 2000;381(12):1233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramić M, Karačić Z, Šemanjski M, Vukelić B, Jajčanin-Jozić N. Aspartate 496 from the subsite S2 drives specificity of human dipeptidyl peptidase III. Biol Chem. 2015;396(4):359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsun M, Jajcanin N, Vukelić B, Spoljarić J, Abramić M. Human dipeptidyl peptidase III acts as a post-proline-cleaving enzyme on endomorphins. Biol Chem. 2007;388(3):343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezerra GA, Dobrovetsky E, Viertlmayr R, Dong A, Binter A, Abramic M, et al. Entropy-driven binding of opioid peptides induces a large domain motion in human dipeptidyl peptidase III. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(17):6525–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berglund G, Elmstähl S, Janzon L, Larsson SA. The Malmo diet and Cancer study. Design and feasibility. J Intern Med. 1993;233(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berglund G, Eriksson KF, Israelsson B, Kjellström T, Lindgärde F, Mattiasson I, et al. Cardiovascular risk groups and mortality in an urban Swedish male population: the Malmö preventive project. J Intern Med. 1996;239(6):489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picod A, Garcia B, Van Lier D, Pickkers P, Herpain A, Mebazaa A, et al. Impaired angiotensin II signaling in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picod A, Deniau B, Vaittinada Ayar P, Genest M, Julian N, Azibani F, et al. Alteration of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system in shock: role of the dipeptidyl peptidase 3. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):526–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna A, English SW, Wang XS, Ham K, Tumlin J, Szerlip H, et al. Angiotensin II for the treatment of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ham KR, Boldt DW, McCurdy MT, Busse LW, Favory R, Gong MN, et al. Sensitivity to angiotensin II dose in patients with vasodilatory shock: a prespecified analysis of the ATHOS-3 trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellomo R, Wunderink RG, Szerlip H, English SW, Busse LW, Deane AM, et al. Angiotensin I and angiotensin II concentrations and their ratio in catecholamine-resistant vasodilatory shock. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2020;06(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia B, Ter Schiphorst B, Santos K, Su F, Dewachter L, Vasques-Nóvoa F, et al. Inhibition of Circulating dipeptidyl-peptidase 3 by Procizumab in experimental septic shock reduces catecholamine exposure and myocardial injury. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2024;12(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellomo R, Forni LG, Busse LW, McCurdy MT, Ham KR, Boldt DW et al. Renin and survival in patients given angiotensin II for Catecholamine-Resistant vasodilatory shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wenzl FA, Bruno F, Kraler S, Klingenberg R, Akhmedov A, Ministrini S, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 3 plasma levels predict cardiogenic shock and mortality in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023. ehad545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Deniau B, Blet A, Santos K, Vaittinada Ayar P, Genest M, Kästorf M, et al. Inhibition of Circulating dipeptidyl-peptidase 3 restores cardiac function in a sepsis-induced model in rats: A proof of concept study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AdrenOSS-1 study investigators, Mebazaa A, Geven C, Hollinger A, Wittebole X, Chousterman BG et al. Circulating adrenomedullin estimates survival and reversibility of organ failure in sepsis: the prospective observational multinational Adrenomedullin and Outcome in Sepsis and Septic Shock-1 (AdrenOSS-1) study. Crit Care [Internet]. 2018 Dec [cited 2018 Dec 28];22(1). Available from: https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-018-2243-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Laterre PF, Pickkers P, Marx G, Wittebole X, Meziani F, Dugernier T, et al. Safety and tolerability of non-neutralizing adrenomedullin antibody adrecizumab (HAM8101) in septic shock patients: the AdrenOSS-2 phase 2a biomarker-guided trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karakas M, Akin I, Burdelski C, Clemmensen P, Grahn H, Jarczak D, et al. Single-dose of adrecizumab versus placebo in acute cardiogenic shock (ACCOST-HH): an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(3):247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, Køber L, Tarvasmäki T, Spinar J, et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(5):501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, Fuernau G, de Waha S, Meyer-Saraei R, et al. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2419–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy B, Clere-Jehl R, Legras A, Morichau-Beauchant T, Leone M, Frederique G, et al. Epinephrine versus norepinephrine for cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(2):173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.