Abstract

Introduction

Growth hormone (GH)-secreting pituitary tumors cause serious systemic comorbidities, necessitating the achievement of gross total resection (GTR) and biochemical remission. This study aims to identify predictors of resection status and biochemical remission.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 54 GH adenoma patients receiving endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach (EETSA). Medical records and magnetic resonance imaging were reviewed for tumor size, volume, resection status, invasion status, and Knosp and Hardy–Wilson grades. We also classified invasion status into high- and low-grade groups. Biochemical remission was defined as an insulin-like growth factor 1 value within sex- and age-adjusted reference or a random GH level < 1.0 ng/mL.

Results

The degrees of horizontal and vertical invasion based on preoperative Knosp and Hardy–Wilson grade were highly associated with intraoperative resection status (p = 0.0054, 0.0043 and 0.013 respectively). We also found more significant differences between resection status and higher-grade invasion (p = 0.0018, 0.006 and 0.0018, respectively). Hardy–Wilson grades and resection status were significantly associated with biochemical remission (p = 0.0484, 0.0252, and 0.0007, respectively). Although we observed no difference between outcomes with respect to micro- vs. macroadenoma, tumor size and volume were significantly associated with outcomes (p = 0.017, 0.0032, respectively). More significant differences were observed between biochemical remission and higher-grade Hardy–Wilson invasion grade (p = 0.0053 and 0.0075). Multivariate analysis showed that higher-grade Hardy–Wilson invasion correlated with resection status (p = 0.0481 and 0.0125); only resection status was associated with biochemical remission (p = 0.0101).

Conclusions

EETSA remains the best treatment option for GH adenomas. Biochemical remission was highly associated with invasion status and the possibility of achieving GTR. Aggressive resection for low-grade and pretreated high-grade tumors promises favorable outcomes.

Keywords: GH pituitary adenoma, Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach, Knosp and Hardy–Wilson grade, Resection status, Biochemical remission, Pre-operative treatment

Introduction

Acromegaly is a condition caused by the overproduction of growth hormone (GH) due to pituitary tumors and the subsequent production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). Control of acromegaly is critical because of the severe systemic comorbidities of this condition, which include cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and musculoskeletal disease. The extent of associated complications and mortality risk are related to the length of exposure to excess GH and IGF-1; thus, early diagnosis and treatment are imperative [1]. Achieving biochemical remission remains the most important goal when treating patients with GH-secreting pituitary tumors. Surgery is the first-line treatment modality, and an endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach (EETSA) is the most appropriate [2, 3]. An important parameter to predict the outcome after surgery is postoperative remission, and several predictors of postoperative biochemical remission have been identified: preoperative human growth hormone and IGF-1 levels, tumor size, tumor volume, Hardy–Wilson classification, Knosp classification, sphenoid sinus invasion, and previous surgery [3–9]. Most of these factors are related to the difficulty in achieving gross total resection (GTR) and biochemical remission [2, 4, 10–17]. However, very few studies have comprehensively discussed the factors influencing the outcomes of patients with GH adenomas. Therefore, we retrospectively reviewed our 16-year experience in treating patients with GH adenomas who received EETSA as the primary treatment. The aim of this study was to identify the pre- and postoperative factors affecting GTR and biochemical remission in our patients and to compare our results with those of other studies. In addition, we identify cases for which preoperative medications may be a more feasible approach.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with GH-secreting pituitary tumors at Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital from October 2004 to December 2020. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB No. 202401326B0). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. During this period, 54 patients received EETSA for pituitary tumor removal. Of these patients, 50 had sufficient medical records, including pre- and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and data on GH and IGF-1 levels. Two patients did not have postoperative MRI scans, and two patients were lost to follow-up from our outpatient department.

Pre- and postoperative MRI scans were reviewed by a neurosurgeon and neuroradiologist for general parameters including tumor size, tumor volume and resection status and some specific characteristics including cavernous sinus (CS) invasion, parasellar invasion, suprasellar invasion, infrasellar invasion, Knosp classification, and Hardy–Wilson classification. We used Knosp classification to evaluate the degree of cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery invasion and Hardy–Wilson classification to evaluate the degree of infrasellar, suprasellar, and parasellar invasion [18, 19]. In addition, we divided the tumors into two groups based on the level of cavernous sinus invasion. A less invasive tumor was defined as Knosp grade < 2, and a more invasive tumor as Knosp grade 3 or 4 [12]. Tumors classified below Hardy–Wilson grade 2 were defined as less infrasellar or sphenoidal sinus invasion, and those with Hardy–Wilson grade 3 or higher were defined as more infrasellar or sphenoidal sinus invasion [6]. The level of suprasellar invasion was based on Hardy–Wilson grade 0–C. Tumors classified below Hardy–Wilson grade C were considered to have less parasellar invasion, and those of grade D and E were considered to have more parasellar invasion [6]. Tumor size was determined by measuring the maximal horizontal length of the tumor in the MRI coronal view. Tumor size was classified as microadenoma (< 1 cm) or macroadenoma (≥ 1 cm). Tumor volume was calculated as A x B x C/2, where A represents the longest tumor length, B represents the longest perpendicular line to A, and C represents the tumor height. Biochemical remission was determined according to the current consensus guidelines as an IGF-1 value within sex- and age-adjusted reference or random GH level < 1.0 ng/mL [20, 21].

We used MedCalc version 19.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) for data analysis. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and the chi-square test was used to compare ordinal variables. Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney test were used for comparing continuous variables. Two multivariate models with stepwise selection methods were performed using the following variables: resection status, tumor volume, Knosp grade (3–4 vs. 0–2), Hardy–Wilson grade (3–4 vs. 1–2) and Hardy–Wilson stage (D–E vs. 0–C) were included. For biochemical remission, tumor volume, pure intrasellar lesion, Hardy–Wilson grade (3–4 vs. 1–2), Hardy–Wilson stage (D–E vs. 0–C), extent of resection, pre-operative GH, and pre-operative IGF-1. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In multivariate models, p ≤ 0.2 was included for covariate entry, and p ≤ 0.05 was considered for covariate stay.

Results

The overall rate of GTR among patients undergoing surgery was 78% (39 of 50 patients), and 27 patients (54%) achieved biochemical remission (Table 1). Comparison of patient data according to resection status (GTR vs. subtotal resection) revealed no significant differences in micro- or macroadenoma, tumor size, or tumor volume (p > 0.99; p = 0.06 and 0.06, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, the possibility of GTR decreased with increasing Knosp grade (p = 0.0054), and the Hardy–Wilson grade also was significantly associated with GTR status (p = 0.0043 and 0.013, respectively). Comparison of patient data according to the degree of invasiveness by Hardy–Wilson and Knosp grade showed that the GTR rate for both classification systems reached statistical significance (p = 0.0018, 0.006, and 0.0018, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Male | 23 (46%) |

| Age (years) | 44.4 ± 14.3 |

| Tumor characteristics | |

| Macroadenoma | 40 (80%) |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.6 ± 0.7 |

| Tumor volume (cm3) | 2.1 ± 2.4 |

| Knosp grade | |

| 0 | 3 (6%) |

| 1 | 23 (46%) |

| 2 | 15 (30%) |

| 3 | 7 (14%) |

| 4 | 2 (4%) |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | |

| 1 | 9 (18%) |

| 2 | 19 (38%) |

| 3 | 14 (28%) |

| 4 | 8 (16%) |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | |

| 0 | 20 (40%) |

| A | 9 (18%) |

| B | 8 (16%) |

| C | 4 (2%) |

| D | 7 (2%) |

| E | 8 (16%) |

| Post-op characteristics | |

| Gross total resection | 39 (78%) |

| Post-op hGH | 1.6 ± 3.2 |

| Post-op IGF-1 | 279 ± 193.8 |

| Biochemical remission | 27 (54%) |

| Follow-up period (months) | 80.7 ± 46.9 |

Values are given as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables

hGH human growth hormone, IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor 1, Post-op postoperative

Table 2.

Patient and tumor data according to gross total resection status

| GTR (n = 39) |

STR (n = 11) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 16 (41.03%) | 7 (63.64%) | 0.18* |

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 14.6 | 41.4 ± 13.1 | 0.43** |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Macroadenoma | 31 (79.49%) | 9 (81.82%) | 1 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 0.06 |

| Tumor volume (cm3) | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 3.8 | 0.06 |

| Knosp grade | 0.0054 | ||

| 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1 | 21 | 2 | |

| 2 | 12 | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | 0.0043 | ||

| 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| 2 | 19 | 0 | |

| 3 | 9 | 5 | |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Stage | 0.013 | ||

| 0 | 18 | 2 | |

| A | 8 | 1 | |

| B | 6 | 2 | |

| C | 4 | 0 | |

| D | 0 | 1 | |

| E | 3 | 5 | |

GTR gross total resection; STR subtotal resection; hGH human growth hormone, IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor 1

Values are given as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables

*X2 test (Chi-square test); Fisher’s exact test used if ≥ 25% of cells had expected count < 5

**Because patient age data had a normal distribution, Student’s t test was more appropriate than the Mann–Whitney test (Wilcoxon rank sum test)

Table 3.

Association between tumor invasiveness grade and gross total resection status

| Variable | GTR (n = 39) |

STR (n = 11) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knosp Grade | 0.0018 | ||

| 0–2 | 36 | 5 | |

| 3–4 | 3 | 6 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | 0.006 | ||

| 1–2 | 26 | 2 | |

| 3–4 | 13 | 9 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Stage | 0.0018 | ||

| 0–C | 36 | 5 | |

| D–E | 3 | 6 |

GTR gross total resection, STR subtotal resection

Comparison of patients with and without biochemical remission showed that those who achieved biochemical remission had a smaller tumor size (p = 0.017) and volume (p = 0.0032) (Table 4). We also found that the rate of achieving biochemical remission decreased with increasing invasiveness according to Hardy–Wilson grading (p = 0.0484 and 0.0252) but not by higher Knosp grade (p = 0.2456). In addition, no significant differences were observed between patients with or without supra-, intra- or infrasellar invasion (p = 0.39, 0.06 and 0.32, respectively). Biochemical remission correlated with resection status (p = 0.0007), and GTR correlated highly with invasion status. The rate of biochemical remission differed significantly between these two classification systems. We further divided the patients into two groups according to the degree of invasiveness for each grading system and found that the rate of achieving biochemical remission was significantly associated with invasiveness as indicated by the Hardy–Wilson grading system (p = 0.0053 and 0.0075) but not by the Knosp grade (p = 0.2697) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Patient and tumor data according to biochemical remission status

| Remission (n = 27) |

Non-remission (n = 23) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 13 (48.15%) | 10 (43.48%) | 0.74* |

| Age (years) | 44.3 ± 13.1 | 44.6 ± 15.9 | 0.93** |

| Tumor characteristics | |||

| Macroadenoma | 20 (74.07%) | 20 (86.96%) | 0.30 |

| Tumor size | 1.3 ± 0.5 cm | 1.8 ± 0.8 cm | 0.017 |

| Tumor volume | 1.4 ± 1.5 cm3 | 3.0 ± 3.0 cm3 | 0.0032 |

| Suprasellar invasion | 12 (44.44%) | 13 (56.52%) | 0.39* |

| Pure intrasellar lesion | 14 (51.85%) | 6 (26.09%) | 0.06* |

| Infrasellar invasion | 7 (25.93%) | 9 (39.13%) | 0.32* |

| Knosp Grade | 0.2456 | ||

| 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1 | 14 | 9 | |

| 2 | 7 | 8 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | 0.0484 | ||

| 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| 2 | 13 | 6 | |

| 3 | 4 | 10 | |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Stage | 0.0252 | ||

| 0 | 14 | 6 | |

| A | 7 | 2 | |

| B | 3 | 5 | |

| C | 2 | 2 | |

| D | 0 | 1 | |

| E | 1 | 7 | |

| Gross total resection | 26 (96.3%) | 13 (56.52%) | 0.0007* |

| Pre-op hGH | 14.3 ± 15.4 | 32.4 ± 38.5 | 0.19 |

| Pre-op IGF-1 | 613.6 ± 241.1 | 688.9 ± 201.0 | 0.17 |

hGH human growth hormone, IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor 1

Values are given as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables

*X2 test (Chi-square test); Fisher’s exact test used if ≥ 25% of cells had expected count < 5

** Because patient age data had a normal distribution, Student’s t test was more appropriate than the Mann–Whitney test (Wilcoxon rank sum test)

Table 5.

Association between tumor invasiveness grade and biochemical remission status

| Remission (n = 27) |

Non-remission (n = 23) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knosp Grade | 0.2697 | ||

| 0–2 | 24 | 17 | |

| 3 ~ 4 | 3 | 6 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | 0.0053* | ||

| 1–2 | 20 | 8 | |

| 3–4 | 7 | 15 | |

| Hardy–Wilson Grade | 0.0075 | ||

| 0–C | 26 | 15 | |

| D–E | 1 | 8 |

*X2 test (Chi-square test); Fisher’s exact test used if ≥ 25% of cells had expected count < 5

Multivariate analysis showed a significant correlation between higher Hardy–Wilson grade (p, 0.0481; adjusted hazard ratio, 6.097; 95% confidence interval, 1.015–36.624), Hardy–Wilson stage (p, 0.0125; adjusted hazard ratio, 9.711, 95% confidence interval, 1.630–57.848) and resection status. A significant correlation was found between resection status and biochemical remission (p, 0.0101; adjusted hazard ratio, 17.308; 95% confidence interval, 1.972–151.882).

Discussion

Acromegaly is a disease that manifests as progressive bone and cartilage growth as well as systemic complications including cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory issues. The first-line therapy for acromegaly is surgical resection, and surgical resection alone leads to disease control in approximately 90% of microadenoma cases and 40–60% of macroadenoma cases [3]. Postoperative biochemical remission is highly related to the preoperative condition and intraoperative resection status [3–5, 7, 22, 23]. The importance of biochemical remission cannot be overemphasized because it ameliorates the systemic effects of elevated GH, IGF-1, and the resultant mortality/morbidity [24].

Classification of parasellar invasion

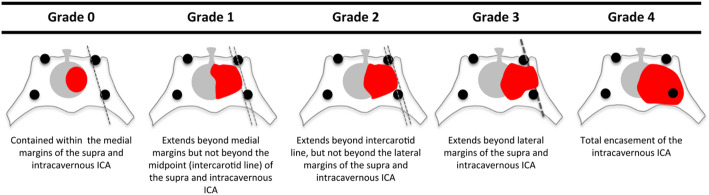

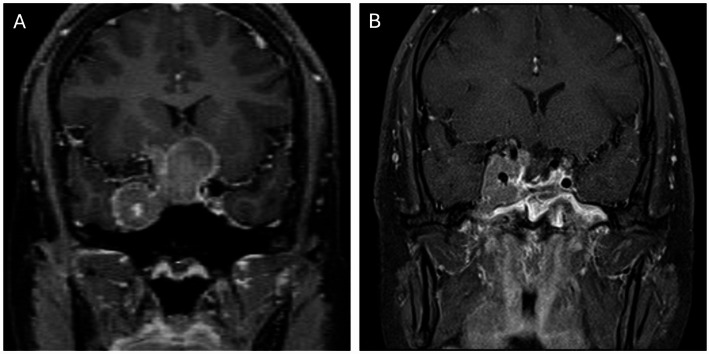

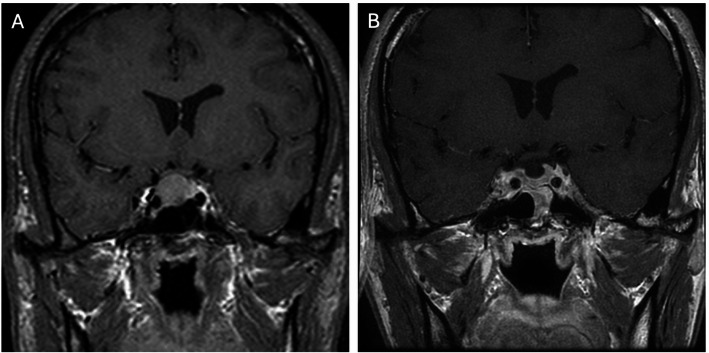

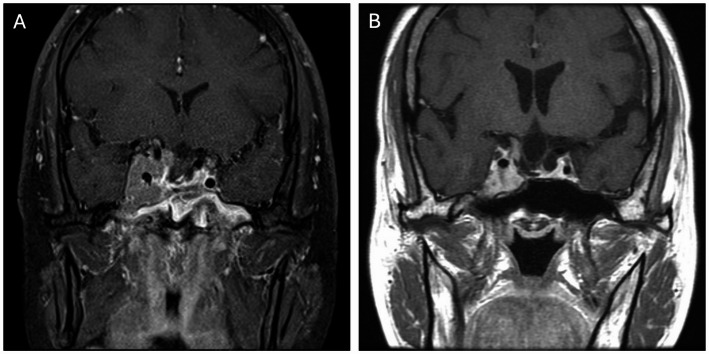

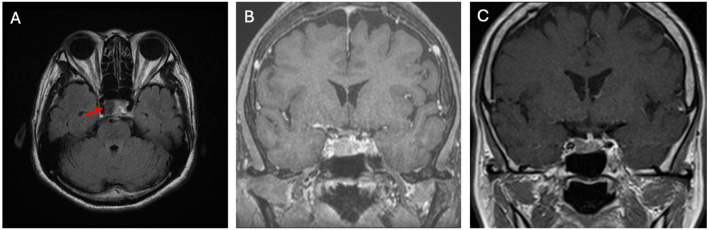

Knosp grade and Hardy–Wilson classification based on preoperative MRI are used to determine cavernous sinus and parasellar invasion [8, 9, 18, 19, 25]. Detailed descriptions of Knosp and Hardy grades are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. As shown in Fig. 3, high Knosp and Hardy grades were associated with lower rates of complete surgical resection and post-operative biochemical remission. A higher grade of tumor invasion was associated with a lower rate of achieving GTR, particularly for pituitary functioning tumors in which biochemical remission is even more critical than non-functioning tumors. An example of GTR attained in a low grade macroadenoma is shown in Fig. 4, further promising biochemical remission.

Fig. 1.

Knosp system grades the parasellar extension of a tumor towards the cavernous sinus in relation to the intracavernous carotid artery [8, 18]

Fig. 2.

Hardy–Wilson classification of pituitary tumors. Upper panel shows the classification of downward sphenoid bone invasion (grade 0, intact with normal contour; grade I, intact with bulging floor; grade II, intact with enlarged fossa; grade III, localized sellar destruction; grade IV, diffuse sellar destruction). Only grade III and IV tumors are considered invasive or high grade. Lower panel describes the classification of upward suprasellar extension (grade A, intrasellar location alone; grade B, recess of the third ventricle; grade C, whole anterior third ventricle; grade D, intracranial extradural; grade E, extracranial extradural) [9]

Fig. 3.

A patient with higher-grade Knosp (grade 4) and Hardy–Wilson classification (grade IV, stage E). A GH adenoma; B STR was accomplished with residue in the right cavernous sinus

Fig. 4.

A patient with lower-grade Knosp (grade 2) and Hardy–Wilson classification (grade II, stage B). A GH adenoma; B GTR was accomplished without residual tumor

Factors influencing intraoperative resection status

Cells that secrete GH reside in the inferior and lateral aspects of the pituitary gland. Consequently, tumors tend to grow in an inferior and lateral direction. Our results are similar to those of previous studies reporting that GTR was associated with achieving biochemical remission [4, 11, 12]. Therefore, achieving GTR is an important predictive factor for disease control. On the other hand, the most crucial determinant in resection is horizontal and vertical invasion. Our results show that intraoperative resection status was highly associated with preoperative Knosp and Hardy–Wilson grades (p = 0.0054, 0.0043, and 0.013, respectively) (Table 2). These results reflect the increase in surgical difficulty when the tumor extended beyond the sellar region in a horizontal or vertical direction. However, our data show that tumor size and volume were not significantly associated with achieving GTR (p = 0.06 and 0.06, respectively). This result contrasts that reported by Zeng et al. [12]. The main reason for this difference may be the mean size of macroadenoma in our study (1.76 cm), which may indicate a lack of higher-grade invasiveness such that the possibility of achieving GTR was similar between micro- and macroadenoma patients. This finding also underscores the importance of early diagnosis in GH adenoma patients, as smaller tumor size increases the possibility of achieving GTR and subsequent biochemical remission. Furthermore, association between GTR and tumor volume (p = 0.06) was closer to 0.05, suggesting that more precise volumetric measurement is important when defining the mass effect of a tumor, especially in irregularly shaped or residual tumors [26, 27]. We also found stronger associations between higher Knosp and Hardy grades and a lower probability of achieving GTR (p = 0.0018, 0.006, and 0.0018, respectively) (Table 3). These results further highlight the importance of careful interpretation of preoperative MRI and the degree of peripheral invasion, especially in tumors with a higher invasion classification.

Factors influencing biochemical remission

Unlike the intraoperative resection status, tumor size and volume correlated positively with postoperative biochemical remission (p = 0.017 and 0.0032, respectively) (Table 4). This finding is similar to the results of other studies [4, 5, 11, 22]. The preoperative Hardy–Wilson classification (p = 0.0484 and 0.0252) and resultant intraoperative resection status (p = 0.0007) were also significantly associated with postoperative biochemical remission. However, the preoperative Knosp grade was not significantly associated with remission status (p = 0.2456). The Knosp grade describes the degree of invasion relevant to the cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery, even in grade 1 and 2 tumors removing all of the tumor surrounding internal carotid artery is technically difficult. Therefore, tumors with a high Knosp grade may be less likely to achieve GTR and post-operative biochemical remission.

We also observed that suprasellar, pure intrasellar, and infrasellar invasion did not correlate with biochemical remission (p = 0.39, 0.06 and 0.32, respectively). This result further supports the notion that the tumor grade is far more important than the anatomical location of invasion for predicting biochemical remission. The suprasellar, pure intrasellar, and infrasellar factors describe anatomical location of vertical tumor invasion, which is thought to be less critical than horizontal invasion. Although the intrasellar tumors were easier to resect, the surgical techniques used were similar to those used for lower Knosp-grade tumors. In patients with infrasellar invasion toward the sphenoid floor or clivus, complete resection of tumors infiltrating into bone was challenging. In addition, GTR may be feasible for lower grade suprasellar invasion, but it remains challenging for higher grade suprasellar invasion (Table 5). Furthermore, although tumor size and volume were predictive of biochemical remission, the lower preoperative GH and IGF-1 levels did not correlate with postoperative biochemical remission (p = 0.19 and 0.17, respectively). Tumors with a smaller size and volume are thought to harbor fewer secreting tumor cells; however, not every tumor cell produces the same amount of GH and the resultant systemic effects. We found a strong association between a lower probability of postoperative biochemical remission (p = 0.0053 and 0.0075) and higher Hardy–Wilson grade and but not Knosp grade (p = 0.2697) (Table 5). A lower Knosp-grade tumor still harbors higher risks of residue hidden in the cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery; therefore, the Knosp grade does not correlate significantly with post-operative biochemical remission. We found that regardless of postoperative biochemical remission or intraoperative resection status, the most pivotal predictive factor was preoperative grading of invasion status, especially in tumors with a higher grade of inferior or lateral invasion. Careful interpretation of preoperative MRI, determining the degree of peripheral invasion, especially in tumors with a higher invasion classification and removing as much of the tumor as possible are the key factors associated with favorable outcomes.

Association of tumor size and volume with resection status and biochemical remission

Many studies have reported an association between tumor size and biochemical remission rates, and some studies have reported that patients who achieve remission have tumors of smaller size [3, 6, 11]. In addition, some studies have reported that patients with microadenoma have a higher remission rate [6, 12]. In our study, the remission rate did not differ significantly between patients with microadenoma (< 1 cm) and macroadenoma. However, the patients who achieved remission did have a smaller tumor size (< 1.3 cm; p = 0.017), a result similar to that reported by Samuel et al. [3]. A possible explanation for this finding is that most macroadenomas associated with higher GTR status were of smaller size (mean size, 1.76 ± 0.67 cm), similar to the size of microadenomas. Therefore, we suggest that a full effort to achieve GTR should made in GH-secreting or other functioning tumors, regardless of tumor size. We also observed that a larger tumor size and volume correlated with a poorer chance of biochemical remission if we did not consider the invasion status. Nevertheless, multivariate analysis showed that tumor size and volume were not significantly associated with resection status or biochemical remission. Therefore, even in larger tumors, the probability of achieving complete resection and biochemical remission may not be affected by size if the invasion status is low.

Association of tumor invasion grade with resection status and biochemical remission

The Hardy–Wilson and Knosp grading systems are widely used to classify the level of tumor invasion and to indicate whether GTR can be achieved. A higher level of tumor invasion is considered to impede complete surgical resection and subsequent biochemical remission. Although some studies report that a higher invasion grade is associated with a lower rate of biochemical remission, the results have been inconsistent [2, 3, 7, 22]. Whether the Hardy–Wilson grade can predict biochemical remission remains controversial. Mohammad et al. reported that biochemical remission was independent of Hardy–Wilson grade [4], whereas Campbell et al. and Yildirim et al. found that remission correlated with the Hardy–Wilson grade [6, 22]. Shin et al. and Yildirim et al. found that the Hardy–Wilson grade was a predictor of biochemical remission [3, 6]. In our study, we comprehensively reviewed all classifications and found that the probability of achieving GTR and the rate of biochemical remission decreased with higher Hardy–Wilson grade. We also found that the rates of achieving GTR and biochemical remission correlated with lower inferior or lateral invasion status. Furthermore, when considering the level of suprasellar extension only, there was no statistical significance among Hardy–Wilson grade 0–C. This finding suggests that GTR can be achieved with well-executed endoscopic endonasal surgery even if the tumor extends into the suprasellar space. Although we used the EETSA, which is via the infrasellar space, sphenoid sinus or clivus invasion may indicate a higher degree of tumor invasion and consequently greater difficulty in curing the disease [6]. However, cavernous sinus invasion is still associated with the greatest difficulty in achieving complete tumor removal and ideal hormone control because of the vital structures inside.

Multivariate analysis confirmed that a higher-grade pre-operative Hardy–Wilson classification and GTR achievement were the most pivotal factors correlating with post-operative biochemical remission. Therefore, accomplishing complete resection, particularly in higher grade tumors that invaded inferiorly or laterally may ensure satisfactory biochemical remission. However, in higher Knosp-grade tumors with internal carotid artery encasement, the chance of biochemical remission decreases with neurovascular injuries sustained while performing aggressive resection.

Clinical implications of treating GH adenomas based on invasiveness status

Our results show that GH adenomas with high-grade invasiveness hindered complete resection and that achieving GTR always increased the risk of unnecessary vascular and neurological injuries. However, several previous studies report that treatment with the somatostatin receptor ligand (SRL) effectively normalized GH and IGF-1, improved clinical symptoms and quality of life, and reduced tumor volume in 62.9–81% of patients [28–33]. Advances in SRL therapy now provide more convenient application, a longer duration, and greater tumor shrinkage with similar safety concerns [34]. In a subtotal resection case, SRLs proved therapeutic in both tumor size reduction and biochemical remission (Fig. 5). Pretreatment with SRLs before surgery has been demonstrated to improve surgical cure rates in patients with GH-secreting pituitary macroadenomas [35], and T2 hypointense adenomas have been shown to respond more dramatically to SRL treatment [36–39]. In our patient who chose to avoid surgery (Fig. 6), a significant treatment response was evident in this T2 hypointense GH adenoma. In such cases, pre-operative SRL can reduce tumor size and invasion grade, thus promoting a better post-operative result than surgery alone. In higher grade GH adenomas, preoperative medications may not only reduce the tumor size but also lower the invasiveness, thereby facilitating surgical procedures and promising similar outcomes to lower grade tumors. In summary, for pure intrasellar tumors or those with lower invasiveness, aggressive GTR should be attempted during surgery. However, for high-grade invasive tumors, preoperative SRL treatment may be a feasible approach to achieving GTR and biochemical remission. Studies with a prospective design enrolling more cases are warranted to elucidate the value of preoperative SRL treatment with respect to the degree of resection and postoperative hormone relief.

Fig. 5.

A higher-grade GH adenoma. A patient underwent STR with residual tumor mainly abutting the right cavernous sinus. B The tumor shrank significantly after SRL treatment

Fig. 6.

Axial T2-weighted image showing a GH adenoma with low signal (A, arrow); Tumor shrank in size significantly from before (B) to after SRL treatment (C)

Study limitations

In the early period of this study, we performed traditional EETSA, which may not have accomplished satisfactory GTR. With the aid of great improvements in EETSA techniques and instrumentation, more complete resection can be performed to increase the likelihood of post-operative biochemical remission. Further studies using EETSA to resect GH or other functioning pituitary adenomas should be conducted. The effect of pre-operative SRL treatment on surgical results remain unclear. A large-scale prospective study is warranted to elucidate the effects of pre-operative SRL, especially for high-grade invasive adenomas.

Conclusions

Pituitary GH adenomas exert systemic effects, and EETSA remains the best treatment for biochemical remission. We found that achieving GTR was associated with biochemical remission and was influenced by invasion status, especially in tumors with higher-grade invasion. Biochemical remission was strongly associated with invasion status and resection status rather than tumor size and volume. Aggressive resection of low-grade and pretreated high-grade tumors promises favorable outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University to support the research and we received a grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Abbreviations

- GH

Growth hormone

- IGF-1

Insulinlike growth factor 1

- EETSA

Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach

- GTR

Gross total resection

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SRL

Somatostatin receptor ligand

Author contributions

T.W.C. and C.C.T. wrote the main manuscript text, Y.C.H., P.W.H., C.C.C. and C.C.L. collected the data, T.W.C. and Y.C.W. did the analysis and prepared the tables and figures, C.C.C. and C.C.L. supervised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG1L0051, CMRPG1L0052, CMRPG1N0071, CMRPG1N0072, Cheng Chi Lee), and the funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB No. 202401326B0). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of their data in the manuscript.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chi-Cheng Chuang and Cheng-Chi Lee contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chi-Cheng Chuang, Email: ccc2915@cgmh.org.tw.

Cheng-Chi Lee, Email: yumex86@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Abreu A, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of acromegaly: a focus on comorbidities. Pituitary. 2016;19(4):448–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo-Castro M, et al. Predictive model of surgical remission in acromegaly: age, presurgical GH levels and Knosp grade as the best predictors of surgical remission. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(1):183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin SS, et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach for growth hormone secreting pituitary adenomas: outcomes in 53 patients using 2010 consensus criteria for remission. Pituitary. 2013;16(4):435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taghvaei M, et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach to the growth Hormone-Secreting pituitary adenomas: endocrinologic outcome in 68 patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;117:e259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofstetter CP, et al. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(4):E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yildirim AE, et al. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal treatment for acromegaly: 2010 consensus criteria for remission and predictors of outcomes. Turk Neurosurg. 2014;24(6):906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jane JA Jr., et al. Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for acromegaly: remission using modern criteria, complications, and predictors of outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):2732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies BM, et al. Assessing size of pituitary adenomas: a comparison of qualitative and quantitative methods on MR. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2016;158(4):677–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatzellis E, et al. Aggressive pituitary tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101(2):87–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardinal T, et al. Postoperative GH and degree of reduction in IGF-1 predicts postoperative hormonal remission in acromegaly. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 743052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardinal T, et al. Impact of tumor characteristics and pre- and postoperative hormone levels on hormonal remission following endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery in patients with acromegaly. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;48(6):E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Y, CD, Wang Y, Mai RK, Zhu ZF. Surgical management of growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas: a retrospective analysis of 33 patients. Medicine. 2020;2020(99):19-e19855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Shen SC, et al. Long-Term effects of intracapsular debulking and adjuvant somatostatin analogs for growth Hormone-Secreting pituitary macroadenoma: 10 years of experience in a single Institute. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:e41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almeida JP, et al. Reoperation for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas: report on an endonasal endoscopic series with a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2018;129(2):404–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yano S, et al. Intraoperative scoring system to predict postoperative remission in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2017;105:375–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briceno V, et al. Efficacy of transsphenoidal surgery in achieving biochemical cure of growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas among patients with cavernous sinus invasion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Res. 2017;39(5):387–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babu H, et al. Long-term endocrine outcomes following endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for acromegaly and associated prognostic factors. Neurosurgery. 2017;81(2):357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knosp E, et al. Pituitary adenomas with invasion of the cavernous sinus space: a magnetic resonance imaging classification compared with surgical findings. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(4):610–7. discussion 617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy J. Transphenoidal microsurgery of the normal and pathological pituitary. Clin Neurosurg. 1969;16:185–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giustina A, et al. A consensus on criteria for cure of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(7):3141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giustina A, et al. Consensus on criteria for acromegaly diagnosis and remission. Pituitary. 2023. 10.1007/s11102-023-01360-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell PG, et al. Outcomes after a purely endoscopic transsphenoidal resection of growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(4):E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirvani M, Motiei-Langroudi R. Transsphenoidal surgery for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas in 130 patients. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(1):125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holdaway IM, Rajasoorya RC, Gamble GD. Factors influencing mortality in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy J, Vezina JL. Transsphenoidal neurosurgery of intracranial neoplasm. Adv Neurol. 1976;15:261–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CC, et al. Prediction of long-term post-operative testosterone replacement requirement based on the pre-operative tumor volume and testosterone level in pituitary macroadenoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang CC, et al. Different volumetric measurement methods for pituitary adenomas and their crucial clinical significance. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caron PJ, et al. Tumor shrinkage with lanreotide autogel 120 mg as primary therapy in acromegaly: results of a prospective multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(4):1282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caron PJ, et al. Effects of lanreotide autogel primary therapy on symptoms and quality-of-life in acromegaly: data from the PRIMARYS study. Pituitary. 2016;19(2):149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caron PJ, et al. Glucose and lipid levels with Lanreotide autogel 120 mg in treatment-naive patients with acromegaly: data from the PRIMARYS study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(4):541–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colao A, Auriemma RS, Pivonello R. The effects of somatostatin analogue therapy on pituitary tumor volume in patients with acromegaly. Pituitary. 2016;19(2):210–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biagetti B, et al. Real-world evidence of effectiveness and safety of Pasireotide in the treatment of acromegaly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2025;26(1):97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleseriu M, et al. A systematic literature review to evaluate extended dosing intervals in the pharmacological management of acromegaly. Pituitary. 2023;26(1):9–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gadelha MR, Wildemberg LE, Kasuki L. The future of somatostatin receptor ligands in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao ZG, et al. Preoperative Lanreotide treatment in acromegalic patients with macroadenomas increases short-term postoperative cure rates: a prospective, randomised trial. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(4):661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagiwara A, et al. Comparison of growth hormone-producing and non-growth hormone-producing pituitary adenomas: imaging characteristics and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 2003;228(2):533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heck A, et al. Intensity of pituitary adenoma on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging predicts the response to octreotide treatment in newly diagnosed acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(1):72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Potorac I, Beckers A, Bonneville JF. T2-weighted MRI signal intensity as a predictor of hormonal and tumoral responses to somatostatin receptor ligands in acromegaly: a perspective. Pituitary. 2017;20(1):116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potorac I, et al. Pituitary MRI characteristics in 297 acromegaly patients based on T2-weighted sequences. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(2):169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.