Abstract

Background

Alcohol abuse and dependence represents a most serious health problem worldwide with major social, interpersonal and legal interpolations. Besides benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants are often used for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Anticonvulsants drugs are indicated for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, alone or in combination with benzodiazepine treatments. In spite of the wide use, the exact role of the anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal has not yet bee adequately assessed.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group' Register of Trials (December 2009), PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL (1966 to December 2009), EconLIT (1969 to December 2009). Parallel searches on web sites of health technology assessment and related agencies, and their databases.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effectiveness, safety and overall risk‐benefit of anticonvulsants in comparison with a placebo or other pharmacological treatment. All patients were included regardless of age, gender, nationality, and outpatient or inpatient therapy.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened and extracted data from studies.

Main results

Fifty‐six studies, with a total of 4076 participants, met the inclusion criteria. Comparing anticonvulsants with placebo, no statistically significant differences for the six outcomes considered.

Comparing anticonvulsant versus other drug, 19 outcomes considered, results favour anticonvulsants only in the comparison carbamazepine versus benzodiazepine (oxazepam and lorazepam) for alcohol withdrawal symptoms (CIWA‐Ar score): 3 studies, 262 participants, MD ‐1.04 (‐1.89 to ‐0.20), none of the other comparisons reached statistical significance.

Comparing different anticonvulsants no statistically significant differences in the two outcomes considered.

Comparing anticonvulsants plus other drugs versus other drugs (3 outcomes considered), results from one study, 72 participants, favour paraldehyde plus chloral hydrate versus chlordiazepoxide, for the severe‐life threatening side effects, RR 0.12 (0.03 to 0.44).

Authors' conclusions

Results of this review do not provide sufficient evidence in favour of anticonvulsants for the treatment of AWS. There are some suggestions that carbamazepine may actually be more effective in treating some aspects of alcohol withdrawal when compared to benzodiazepines, the current first‐line regimen for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Anticonvulsants seem to have limited side effects, although adverse effects are not rigorously reported in the analysed trials.

Keywords: Humans, Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium, Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium/drug therapy, Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures, Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures/drug therapy, Anticonvulsants, Anticonvulsants/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal syndrome

There are limited data on anticonvulsants versus placebo for alcohol withdrawal syndrome, while comparisons with other drugs show no clear differences.

This Cochrane review summarizes evidence from forty‐eight randomised controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness and safety of anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. There are limited data comparing anticonvulsants versus placebo and no clear differences between anticonvulsants and other drugs in the rates of therapeutic success. Data on safety outcomes are sparse and fragmented. There is a need for larger, well‐designed studies in this field.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anticonvulsant versus Placebo for alcohol withdrawal.

| Anticonvulsant versus Placebo for alcohol withdrawal | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with alcohol withdrawal Settings: Intervention: Anticonvulsant versus Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Anticonvulsant versus Placebo | |||||

| Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures post treatment ‐ Any Anticonvulsant vs. Placebo | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.31 to 1.2) | 883 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 110 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (34 to 132) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 167 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (52 to 200) | |||||

| Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures post treatment ‐ Phenytoin vs. Placebo | Study population | RR 0.78 (0.35 to 1.77) | 381 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 180 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 (63 to 319) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 176 per 1000 | 137 per 1000 (62 to 312) | |||||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 1.56 (0.74 to 3.31) | 663 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (37 to 165) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 34 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (25 to 113) | |||||

| Dropout ‐ Any Anticonvulsant vs. Placebo | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.5 to 1.34) | 344 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 208 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (104 to 279) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 182 per 1000 | 149 per 1000 (91 to 244) | |||||

| Dropout ‐ Chlormethiazole vs. Placebo | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.22 to 5.11) | 140 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | ||

| 44 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (10 to 225) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 21 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (5 to 107) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealmnt adequate only in 1 on 9 included studies 2 Allcation concealment adequate in 1/4 studies 3 In 3 studies results were not estimable due no adverse events occurred 4 Allocation concealment adequate in 2 on 7 included studies 5 only 3 studies considered

Summary of findings 2. Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs for alcohol withdrawal.

| Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs for alcohol withdrawal | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with alcohol withdrawal Settings: Intervention: Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs | |||||

| Alcohol withdrawal seizures ‐ Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | Study population | RR 0.58 (0.22 to 1.58) | 880 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 27 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 43) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 19 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (4 to 30) | |||||

| Adverse events ‐ Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.45 to 1.12) | 726 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | ||

| 287 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (129 to 321) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 188 per 1000 | 133 per 1000 (85 to 211) | |||||

| Dropout ‐ Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.67 to 1.26) | 1359 (20 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 114 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (76 to 144) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 99 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (66 to 125) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment adequate in 2 on 12 included studies 2 In 5 studies no events and results not estimable 3 Allocation concealment adeqate in 4/14 included studies 4 Allocation concealment adequate in 5 on 20 included studies

Background

Description of the condition

Alcohol abuse and dependence represents a most serious health problem worldwide with major social, interpersonal and legal interpolations. Dependence on alcohol is associated with both physiological symptoms such as tolerance and withdrawal, and behavioural symptoms such as impaired control over drinking (Hasin 1990). Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is a cluster of symptoms that occurs in alcohol‐dependent people after cessation or reduction in alcohol use that has been heavy or prolonged. The clinical presentation varies from mild to serious and the onset of symptoms typically occurs a few hours after the last alcohol intake. The most common manifestations are tremor, restlessness, insomnia, nightmares, paroxysmal sweats, tachycardia, fever, nausea, vomiting, seizures, hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile), increased agitation, tremulousness and delirium. These symptoms involve a wide range of neurotransmitter circuits that are implicated in alcohol tolerance and reflect a homeostatic readjustment of the central nervous system (De Witte 2003; Koob 1997; Nutt 1999; Slawecki 1999). Long‐term alcohol consumption affects brain receptors that undergo adaptive changes in an attempt to maintain normal function. Some of the key changes involve reduced brain gamma‐amino butyric acid (GABA) levels and GABA‐ receptor sensitivity (Dodd 2000; Gilman 1996; Kohl 1998; Petty 1993) and activation of glutamate systems (Tsai 1995), which lead to nervous system hyperactivity in the absence of alcohol. The advances in knowledge of neurobiology and neurochemistry have prompted the use of drugs in the treatment of alcohol dependence and withdrawal that act through these GABA pathways.

Description of the intervention

Besides benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants are often used for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. A meta‐analysis of studies concerning pharmacological therapies of alcohol withdrawal (Mayo‐Smith 1997) has suggested that carbamazepine, an anticonvulsant agent that is widely used in particular in Europe, may have modest beneficial effects on selected signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Carbamazepine may also be considered as adjunctive therapy to benzodiazepines, the classic treatment for alcohol withdrawal.

How the intervention might work

Anticonvulsants drugs are indicated for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, alone or in combination with benzodiazepine treatments. In spite of the wide use, the exact role of the anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal has not yet been adequately assessed. Moreover not all patients may need pharmacological treatment and it is unknown whether different anticonvulsants and different regimens of administration (e.g. symptom‐triggered versus fixed schedule) may have the same merits.

Why it is important to do this review

The need to research non‐benzodiazepines effective in Alcohol Withdrawal is related to the risks of side‐effects and the potential of abuse of benzodiazepine (Leggio 2008).

Since there are several anticonvulsant agents and a large amount of evidence of their use in the management of alcohol withdrawal has been published during the last years, an updated systematic is needed in order to clarify the exact role of anticonvulsants in the management of alcohol withdrawal.

The purpose of this systematic review is to examine the evidence in the effectiveness and safety of anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Results of a previous version of a Cochrane Systematic review (Polycarpou 2005) on anticonvulsants efficacy and safety are not conclusive. New trials have been published and the review needs update.

This review has a parallel one on benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal (Amato 2010) and together they are part of a series of reviews and protocols on the efficacy of pharmacological treatment (Acamprosate GHB, nitrous oxide, magnesium) for alcohol withdrawal (Gillman 2007; Leone 2010; Fox 2003; Tejani 2010).

Objectives

The objectives of this systematic review are:

To evaluate the effectiveness of anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal.

To evaluate the safety of anticonvulsants in the treatment of the alcohol withdrawal symptoms (AWS).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) and Controlled Clinical Trials (CCT) evaluating the efficacy, safety and overall risk‐benefit of anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal.

Types of participants

Alcohol dependent patients diagnosed in accordance with appropriate standardized criteria (e.g., criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV‐R) or ICD) who experienced alcohol withdrawal symptoms regardless of the severity of the withdrawal manifestations. All patients were included regardless of age, gender, nationality, and outpatient or inpatient therapy. The history of previous treatments was considered, but it was not an eligibility criterion.

Types of interventions

‐ Experimental intervention

Anticonvulsants drugs alone or in combination with other drugs

‐ Control Intervention

Placebo; Other pharmacological interventions

Types of comparisons

anticonvulsant versus placebo;

anticonvulsant versus other drugs;

different anticonvulsants between themselves;

anticonvulsant combined with other drugs versus other drugs.

anticonvulsant 1 combined with other drugs versus anticonvulsant 2

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Efficacy outcomes

Alcohol withdrawal seizures as number of subjects experiencing seizures

Alcohol withdrawal delirium as number of subjects experiencing delirium

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms as measured by prespecified scales(as the CIWA‐Ar score)

Global improvement of overall alcohol withdrawal syndrome as measured in pre‐specified scales ( as number of patients with global improvement, global doctors assessment of efficacy, Patients assessment of efficacy)

Craving as measured by prespecified scales

Safety outcomes

Adverse events as number of subjects experiencing at least one adverse event

Severe, life‐threatening adverse events as measured by number of subjects experiencing severe, life threatening adverse events

Acceptability outcomes

Dropout

Dropout due to adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Additional medication needed

Length of stay in intensive therapy

Mortality

Quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Relevant trials were obtained from the following sources:

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group' Register of Trials (December 2009)

PubMed (January 1966– December 2009)

EMBASE (January 1988– December 2009)

CINAHL (January 1982– December 2009)

EconLIT (1969 to December 2009)

We compiled detailed search strategies for each database searched, for detail see Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4

Searching other resources

We also searched:

the reference lists of all relevant papers to identify further studies.

conference proceedings likely to contain trials relevant to the review.

We contacted investigators seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials.All searches included non‐English language literature and studies with English abstracts were assessed for inclusion. When considered likely to meet inclusion criteria, studies were translated.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of all publications, obtained through the search strategy. All potentially eligible studies were obtained as full articles and two authors independently assessed these for inclusion. In doubtful or controversial cases, all identified discrepancies were discussed and reached consensus on all items.

Data extraction and management

Two authors independently extracted data from published sources, where differences in data extracted occurred this was resolved through discussion. Where required additional information was obtained through collaboration with the original authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs and CCTs in this review was performed using four out of the six criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbbok (Higgins 2008). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Review is a two‐part tool, addressing four specific domains (namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data). The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry. This is achieved by answering a pre‐specified question about the adequacy of the study in relation to the entry, such that a judgement of "Yes" indicates low risk of bias, "No" indicates high risk of bias, and "Unclear" indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias. To make these judgments we will use the criteria indicated by the handbook adapted to the addiction field. See Appendix 5 for details.

The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) will be addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessor (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) was considered separately for objective outcomes (e.g. drop out, drop out due to adverse events, seizures, delirium, adverse events) and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, craving, psychiatric symptoms; improvements assessed by doctors and patients).

Incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) was considered for all outcomes except for the drop out from the treatment, which is very often the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes were analysed calculating the Relative risk (RR) for each trial with the uncertainty in each result being expressed by their confidence intervals. Continuous outcomes were analysed calculating the MD or the SMD with 95%CI. In case of missing standard deviation of the differences from baseline to the end of treatment, the standard deviation were imputed using the standard deviation of the mean at the end of treatment for each group.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistically significant heterogeneity among primary outcome studies will be assessed with Chi‐squared (Q) test and I‐squared (Higgins 2008). A significant Q ( P<.05) and I‐squared of at least 50% will be considered as statistical heterogeneity

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plot (plot of the effect estimate from each study against the sample size or effect standard error) was not used to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials, because all the included studies had small sample size and not statistically significant results.

Data synthesis

The outcomes from the individual trials have been combined through meta‐analysis where possible (comparability of intervention and outcomes between trials) using a fixed effect model unless there was significant heterogeneity, in which case a random effect model have been used.

If all arms in a multi‐arm trial are to be included in the meta‐analysis and one treatment arm is to be included in more than one of the treatment comparisons, then we divided the number of events and the number of participants in that arm by the number of treatment comparisons made. This method avoid the multiple use of participants in the pooled estimate of treatment effect while retaining information from each arm of the trial. It compromise the precision of the pooled estimate slightly.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the effect of methodological quality on the results, we first performed a graphical inspection of any effect sorting the results on the forest plots according to risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (subjective outcomes) ; if we found a difference in the results between studies at low, unclear, high risk of bias, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 993 reports from all electronic databases searched excluding duplicate, 899 were excluded on basis of title and abstract; 91 articles were retrieved in full text for more detailed evaluation, 35 of which were excluded, 56 satisfied all the criteria to be included in the review. Three studies are awaiting assessment because we are trying to find the full text. SeeFigure 1 to see the Flow chart showing the identification of included trials.

1.

Flow chart showing identification of studies

Included studies

56 studies met the inclusion criteria, with a total of 4076 participants. For a description of the characteristics of the included studies, see Characteristics of included studies table

Country of origin of the included studies

33 studies were conducted in Europe, 18 in North America, 4 in Australia/New Zealand, and one in Asia.

Number of studies per type of comparison

Anticonvulsant versus placebo (No. = 17 studies, 17 comparisons) (Alldredge 1989; Bjorkqvist 1976; Blanchard 1985; Bonnet 2003; Burroughs 1985a; Chance 1991; Gann 2004; Glatt 1966; Golbert 1967; Koethe 2007; Krupitsky 2007; Lambie 1980; Murphy 1983; Rathlev 1994; Reoux 2001; Sampliner 1974; Stanhope 1989)

Anticonvulsant versus other drug (No. = 32 studies, 36 comparisons) (Agricola 1982; Borg 1986; Borg 1986; Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Burroughs 1985b; Choi 2005; Dencker 1978; Elsing 1996; Elsing 2009; Golbert 1967; Kaim 1972; Kaim 1972; Kalyoncu 1996; Koppi 1987; Kramp 1978; Krupitsky 2007; Lapierre 1983; Longo 2002; Lucht 2003; Madden 1969; Malcolm 1989; Malcolm 2002; Malcolm 2007; Manhem 1985; McGrath 1975; Murphy 1983; Nimmerichter 2002; Radouco‐Thomas 1989; Robinson 1989; Santo 1985; Stuppaeck 1992; Stuppaeck 1998; Thompson 1975; Tubridy 1988)

Different anticonvulsants between themselves (No.= 10 studies, 11 comparisons) (Flygering 1984; Golbert 1967; Kaim 1972; Krupitsky 2007; Krupitsky 2007; Mariani 2006; Ritola 1981; Rosenthal 1998; Schik 2005; Seifert 2004; Teijeiro 1975)

Anticonvulsant combined with other drug versus other drug (No. = 6 studies, 7 comparisons) (Balldin 1986; Golbert 1967; Lucht 2003; Myrick 2000; Spies 1996; Spies 1996; Rothstein 1973)

Anticonvulanst combined with other drug vs different anticonvulsant (No=1 study) (Croissant 2009)

For a more detailed information about the comparisons considered in the studies, see Additional Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

1. Comparisons Anticonvulsants versus placebo.

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant) | Control |

| Alldredge 1989 | Phenytoin | Placebo |

| Bjorkvist 1976 | Carbamazepine (34) | Placebo |

| Blanchard 1985 | Phenobarbital | Placebo |

| Bonnet 2003 | Gabapentin | Placebo |

| Burroughs 1985 a | Chlormethiazole | Placebo |

| Chance 1991 | Phenytoin | Placebo |

| Gann 2004 | Chlormethiazole | Placebo |

| Glatt 1966 | Chlormethiazole | Placebo |

| Golbert 1967 | Promazine | Placebo |

| Koethe 2007 | Oxcarbazepine | Placebo |

| Krupitsky 2007 | Topiramate | Placebo |

| Lambie 1980 | Valproate | Placebo |

| Murphy 1983 | Chlormethiazole | Placebo |

| Rathlev 1994 | Phenytoin | Placebo |

| Reoux 2001 | Divalproex | Placebo |

| Sampliner 1974 | Phenytoin | Placebo |

| Stanhope 1989 | Carbamazepine | Placebo |

2. Comparisons Anticonvulsants versus Other.

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant) | Control (Other) |

| Borg 1986 | Amobarbital | Oxazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Borg 1986 | Amobarbital | Melperone (antipsychotic) |

| Kramp 1978 | Barbital | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Agricola 1982 | Carbamazepine | Tiapride (antipsychotic) |

| Kalyoncu 1996 | Carbamazepine | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Malcom 1989 | Carbamazepine | Oxazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Malcom 2002 | Carbamazepine | Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Stuppaeck 1992 | Carbamazepine | Oxazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Burroughs 1985 a | Chlormethiazole | Bromocriptine (dopamine agonist) |

| Burroughs 1985 a | Chlormethiazole | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Burroughs 1985 b | Chlormethiazole | Bromocriptine (dopamine agonist) |

| Burroughs 1985 b | Chlormethiazole | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Dencker 1978 | Chlormethiazole | Piracetam (CNS stimulant) |

| Elsing 1996 | Chlormethiazole | GHB (gamma‐Hydroxybutyric acid) |

| Elsing 2009 | Chlormethiazole | GHB (gamma‐Hydroxybutyric acid) |

| Lapierre 1983 | Chlormethiazole | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Lucht 2003 | Chlormethiazole | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Madden 1969 | Chlormethiazole | Trifluoperazine (antipsychotic) |

| Manhem 1985 | Chlormethiazole | Clonidine (adrenergic agonist) |

| McGrath 1975 | Chlormethiazole | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Murphy 1983 | Chlormethiazole | Tiapride (antipsychotic) |

| Nimmerichter 2002 | Chlormethiazole | GHB (gamma‐Hydroxybutyric acid) |

| Robinson 1989 | Chlormethiazole | Clonidine (adrenergic agonist) |

| Tubridy 1988 | Chlormethiazole | Alprazolam (benzodiazepine) |

| Longo 2002 | Depakote | Chlordiazepoxide or Loranzepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Malcom 2007 | Gabapentin | Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Koppi 1987 | Meprobamate | Caroverine (spasmolytic) |

| Kaim 1972 | Paraldehyde | Perhenazine (antipsychotic) |

| Kaim 1972 | Paraldehyde | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Thompson 1975 | Paraldehyde | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Golbert 1967 a | Promazine | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Raduco‐Thomas 1989 | Tetrabamate | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Santo 1985 | Tetrabamate | Tiapride (Antipsychotic) |

| Choi 2005 | Topiramate | Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Krupitsky 2007 | Topiramate | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant) | Control |

| Stuppaeck 1998 | Vigabatrin | Oxazepam (benzodiazepine) |

3. Comparisons Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2.

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant 1) | Control (Anticonvulsant 2) |

| Flygering 1984 | Carbamazepine | Barbital |

| Scik 2005 | Carbamazepine | Oxcarbazepine |

| Mariani 2006 | Chlormethiazole | Phenobarbital |

| Ritola 1981 | Chlormethiazole | Carbamazepine |

| Seifert 2004 | Chlormethiazole | Carbamazepine |

| Teijeiro 1975 | Heminiurine | Phenobarbital+ Ferbamate (tranquillizes) |

| Kaim 1972 | Paraldehyde | Pentobarbital |

| Golbert 1967 b | Promazine | Paraldehyde and Chloral hydrate (sedative) |

| Krupitsky 2007 | Topiramate | Memantine |

| Krupitsky 2007 | Topiramate | Lamotrigine |

| Rosenthal 1998 | Valproate | Phenobarbital |

4. Anticonvulsant + Other versus Other.

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant+Other) | Control |

| Balldin 1986 | Carbamazepine +Chlorprothixen (antipsychotic) | Clonidine (adrenergic agonist) |

| Lucht 2003 | Carbamazepine+Tiapride (antipsychotic) | Diazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Spies 1996 | Chlormethiazole+Haloperidol (antipsychotic) | Clonidine (adrenergic agonist)+fFunitrazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Spies 1996 | Chlormethiazole+Haloperidol (antipsychotic) | Funitrazepam (benzodiazepine)+ Haloperidol (antipsychotic) |

| Rothstein 1973 | Diphenylhydantoin | Tiamine (antipsychotic)+ Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

| Myrick 2000 | Divalproex+Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) | Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) |

| Golbert 1967 | Paraldehyde and Chloral hydrate (sedative) | Chlordiazepoxide (benzodiazepine) |

5. Comparison Anticonvulsant 1 + Other versus Anticonvulsant 2.

| Author | Treatment (Anticonvulsant 1+other) | Control (Anticonvulsant 2) |

| Croissant 2009 | Oxcarbazepine + Tiapride (antipsychotic) | Chlormethiazole |

Excluded studies

35 studies did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this review. The grounds for exclusion were: type of intervention not in the inclusion criteria: 13 studies; study design not in the inclusion criteria: 12 studies; type of outcomes measures not in the inclusion criteria: 6 studies; duplicate publication: 2 studies, outcome measures presented in a way not suitable for meta‐analysis: 2 studies. SeeExcluded studies Table

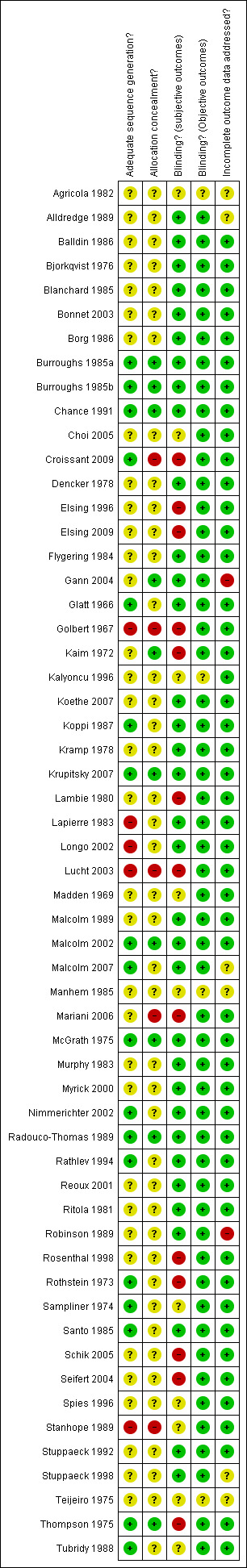

Risk of bias in included studies

All the studies were randomised controlled trials.

Allocation

The sequence generation was adequate in 17 studies, unclear in 34 and inadequate in 5 studies; the allocation concealment was adequate in 9 studies, unclear in 42 and inadequate in 5 studies

Blinding

Blinding for subjective outcomes was adequate in 33 studies, it was unclear in 10 and inadequate in 13

Blinding for objective outcomes was adequate in 52 studies and unclear in 4 studies

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data were addressed in 48 studies, it was unclear in 6 studies and were not addressed in 2 studies.

See Included studies Table and Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias across the studies.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

With a graphical inspection of the forest plots sorting studies according to the risk of bias, we didn't find any systematic difference in the results between studies at high risk of bias and studies at low or unclear risk of bias. So sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias was not performed

Effects of interventions

We only performed meta‐analysis for the studies that had directly comparable interventions and used exactly the same rating scales for continuous outcome measures or had the same binary outcomes. The rest of the data retrieved from the studies (single comparison data) were not synthesized quantitatively. The following results refer to the cases where quantitative synthesis was performed.

The Results are split into four sections referring to the four main comparisons:

Anticonvulsant versus Placebo,

Anticonvulsant versus Other Drug,

Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2,

(Anticonvulsant + Other drug) versus Other Drug.

(Anticonvlusant 1 + other drug) versus Anticonvulsant 2

The outcomes are categorized as primary efficacy outcomes and secondary efficacy outcomes, according to the protocol. We dived them according to efficacy, safety and acceptability.

We decided to not consider separately the comparison between anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines because this is due in the parallel review (Amato 2010) on benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal

For a summary of results of some important outcomes see Summary of findings table 1 and Summary of findings table 2

Comparison 1 Anticonvulsant versus placebo:

Efficacy

1.1 Alcohol withdrawal seizures

1.1.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus placebo, 9 studies (Alldredge 1989; Bonnet 2003; Chance 1991; Koethe 2007; Lambie 1980; Murphy 1983; Rathlev 1994; Sampliner 1974; Stanhope 1989), 883 participants, RR 0.61 (0.31 to 1.20), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.1 or Figure 4

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, Outcome 1 Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures post treatment.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, outcome: 1.1 Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures post treatment.

1.1.2 Phenytoin versus placebo, 4 studies, (Alldredge 1989; Chance 1991; Rathlev 1994; Sampliner 1974), 381 participants, RR 0.78 (0.35 to 1.77), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.1 or Figure 4

Safety

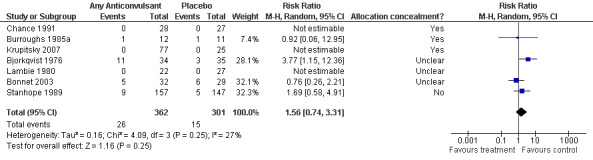

1.2 Adverse events as number of participants with at least one adverse event

7 studies (Bjorkqvist 1976; Bonnet 2003; Burroughs 1985b; Chance 1991; Krupitsky 2007; Lambie 1980; Stanhope 1989), 516 participants, RR 1.56 (0.74, 3.31), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.2 or Figure 5

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, outcome: 1.4 Adverse events (N. of patients with at least one adverse event).

Acceptability

1.3 Dropout

1.5.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus placebo , 7 studies (Bjorkqvist 1976; Blanchard 1985; Bonnet 2003; Burroughs 1985a; Gann 2004; Glatt 1966; Reoux 2001), 344 participants, RR 0.82 (0.50 to 1.34), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.3 or Figure 6

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, Outcome 3 Dropout.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, outcome: 1.5 Dropout.

1.1.2 Chlormethiazole versus placebo , 3 studies (Burroughs 1985a; Gann 2004; Glatt 1966), 140 participants, RR 1.05 (0.22 to 5.11), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.3 or Figure 6

1.4 Dropout due to adverse events

8 studies (Bjorkqvist 1976; Blanchard 1985; Bonnet 2003; Burroughs 1985a; Chance 1991; Koethe 2007; Lambie 1980; Stanhope 1989), 623 participants, 0.67 (0.13, 3.36), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 1.4 or Figure 7

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, Outcome 4 Dropout due to adverse events.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anticonvulsant versus Placebo, outcome: 1.6 Dropout due to adverse events

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other:

Efficacy

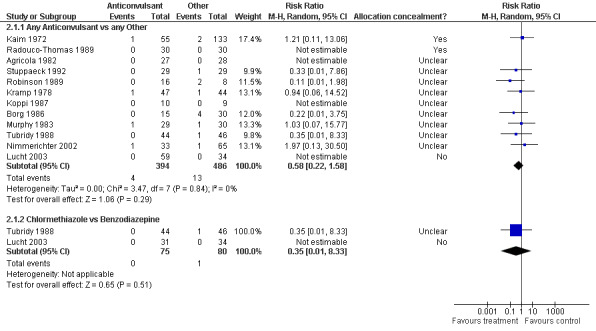

2.1 Alcohol withdrawal seizures

2.1.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 12 studies (Agricola 1982; Borg 1986; Kaim 1972; Koppi 1987; Kramp 1978; Lucht 2003; Murphy 1983; Nimmerichter 2002;Radouco‐Thomas 1989 ;Robinson 1989; Stuppaeck 1992; Tubridy 1988), 880 participants, RR 0.58 (0.22 to 1.58), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.1 or Figure 8

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 1 Alcohol withdrawal seizures.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.1 Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures

2.1.2 Chlormethiazole versus Benzodiazepine, 2 studies (Lucht 2003; Tubridy 1988), 155 participants, RR 0.35 (0.01 to 8.33), the result is not statistically significant, see or Figure 8

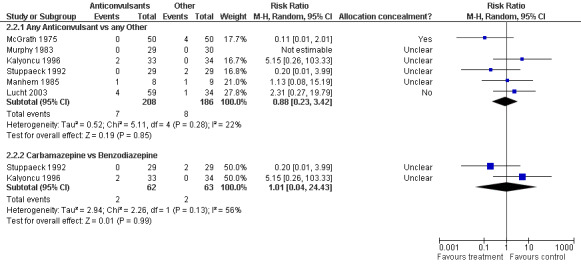

2.2 Alcohol withdrawal delirium

2.2.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 6 studies (Kalyoncu 1996; Lucht 2003; Manhem 1985;McGrath 1975; Murphy 1983; Stuppaeck 1992; ), 394 participants, RR 0.88 (0.23, 3.42), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.2 or Figure 9

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 2 Alcohol withdrawal delirium.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.2 Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium

2.2.2 Carbamazepine versus Benzodiazepine, 2 studies (Kalyoncu 1996; Stuppaeck 1992), 125 participants, RR 1.01 (0.04 to 24.43), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.2 or Figure 9

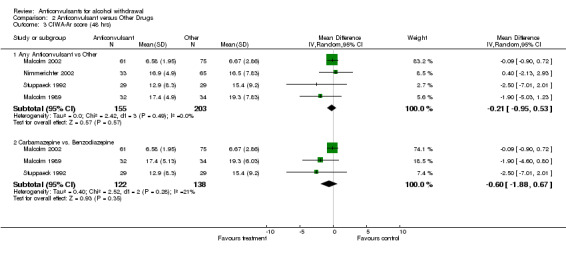

2.3 CIWA‐Ar score at 48 hours

2.3.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 4 studies (Malcolm 1989; Malcolm 2002; Nimmerichter 2002; Stuppaeck 1992), 358 participants, MD ‐0.21 (‐0.95 to 0.53), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.3

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 3 CIWA‐Ar score (48 hrs).

2.3.2 Carbamazepine versus Benzodiazepine, 3 studies (Malcolm 1989; Malcolm 2002; Stuppaeck 1992), 260 participants MD ‐0.60 (‐1.88 to 0.67), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.3

2.4 CIWA‐Ar score at the end of treatment

2.4.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 4 studies (Malcolm 1989; Malcolm 2002; Nimmerichter 2002; Stuppaeck 1992), 358 participants, MD ‐0.73 (‐1.76 to 0.31), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.4

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 4 CIWA‐Ar score (end of treatment).

2.4.2 Carbamazepine versus Benzodiazepine , 3 studies (Malcolm 1989; Malcolm 2002; Stuppaeck 1992), 260 participants MD ‐1.04 (‐1.89 to ‐0.20), the result is statistically significant in favour of carbamazepine, see Analysis 2.4

2.5 Global Doctor’s Assessment of Efficacy

2 studies (Kramp 1978; Tubridy 1988), 181 participants, RR 0.97 (0.88 to 1.08), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.5

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 5 Global Doctor's Assessment of Efficacy.

Safety

2.6 Adverse events as number of participants with at least one adverse event

2.6.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other (Agricola 1982;Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b;Elsing 2009; Krupitsky 2007; Lapierre 1983; Longo 2002; Lucht 2003; Nimmerichter 2002; Radouco‐Thomas 1989 ;Robinson 1989; Santo 1985; Stuppaeck 1992; Tubridy 1988), 14 studies, 726 participants, RR 0.71(0.45 to 1.12), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.6 or Figure 10

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 6 Adverse events.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.14 Adverse events (number of patient with at least one adverse event)

2.6.2 Chlormethiazole versus Benzodiazepine , (Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Lapierre 1983; Lucht 2003; Tubridy 1988), 5 studies, 235 participants, RR 0.75 (0.35 to 1.59), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.6 or Figure 10

2.7 Severe, life‐treating adverse events

2.17.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 12 studies (Agricola 1982; Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Dencker 1978;Elsing 2009; Koppi 1987; Krupitsky 2007; Lapierre 1983; Radouco‐Thomas 1989; Santo 1985; Thompson 1975; Tubridy 1988), 578 participants, RR 2.38 (0.33 to 17.24), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.7 or Figure 11

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 7 Severe, life‐treatening adverse events.

11.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.15 Severe, life‐treating adverse events

2.7.2 Chlormethiazole versus Benzodiazepine , (Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Lapierre 1983; Tubridy 1988), 4 studies, 170 participants, RR 0.69 (95% CI, 0.09 to 5.33), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.7 or Figure 11

Acceptability

2.8 Dropout

2.8.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 20 studies (Agricola 1982; Borg 1986; Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Dencker 1978; Elsing 2009; Kaim 1972; Kalyoncu 1996; Koppi 1987; Kramp 1978; Lucht 2003; Manhem 1985;McGrath 1975; Murphy 1983; Nimmerichter 2002; Radouco‐Thomas 1989 ;Robinson 1989; Santo 1985; Stuppaeck 1992; Tubridy 1988), 1359 participants, RR 0.92 (0.67, 1.26), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.8 or Figure 12

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 8 Dropout.

12.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.18 Dropout.

2.8.2 Chlormethiazole versus Benzodiazepine, 5 studies (Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Lucht 2003;McGrath 1975; Tubridy 1988), 311 participants, RR 0.68 (0.37, 1.24), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.8 or Figure 12

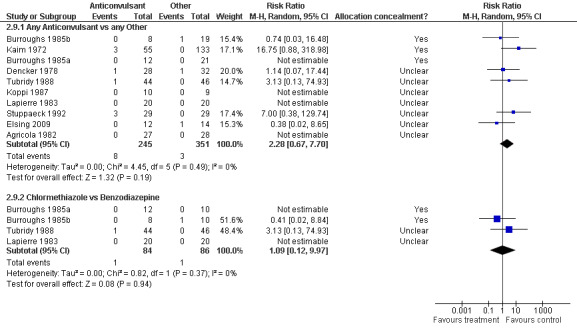

2.9 Dropout due to adverse events

2.9.1 Any Anticonvulsants versus any Other , 10 studies (Agricola 1982; Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Dencker 1978; Elsing 2009; Kaim 1972; Koppi 1987; Lapierre 1983; Stuppaeck 1992; Tubridy 1988), 596 participants, RR 2.28 (0.67 to 7.70), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.9 or Figure 13

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs, Outcome 9 Dropout due to adverse events.

13.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Anticonvulsant versus Other, outcome: 2.19 Dropout due to adverse events.

2.9.2 Chlormethiazole versus Benzodiazepine, 4 studies (Burroughs 1985a; Burroughs 1985b; Lapierre 1983; Tubridy 1988), 170 participants, RR 1.09 (0.12 to 9.97), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 2.9 or Figure 13

Comparison 3 Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2:

Safety

3.1 Adverse events as number of participants with at least one adverse event

3.1.1 Carbamazepine versus Chlormethiazole , 2 studies (Lucht 2003; Ritola 1981), 121 participants, RR 3.12 (0.50 to 19.27), the result is not statistically significant

3.1.2 Carbamazepine versus Barbital , 1 study (Flygering 1984), 61 participants, RR 1.81 (0.70 to 4.68), the result is not statistically significant

3.1.3 Carbamazepine versus Oxcarbazepine , 1 study (Schik 2005), 29 participants, the result is not estimable because there were no side effects in both groups

3.1.4 Chlormethiazole versus Pentobarbital , 1 study (Mariani 2006), 27 participants, RR 2.80 (0.12 to 63.20), the result is not statistically significant

See Analysis 3.1 or Figure 14

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 1 Adverse events.

14.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2, outcome: 3.1 Adverse events (number of patients with at least one adverse event).

Acceptability

3.2 Dropout

3.2.1 Carbamazepine versus Chlormethiazole , 2 studies (Lucht 2003; Ritola 1981), 121 participants, RR 0.51 (0.08 to 3.11), the result is not statistically significant

3.2.2 Carbamazepine versus Barbital , 1 study (Flygering 1984), 60 participants, RR 0.94 (0.34 to 2.57), the result is not statistically significant

3.2.3 Carbamazepine versus Oxcarbazepine , 1 study (Schik 2005), 29 participants, RR 3.20 (0.14 to 72.62), the result is not statistically significant

3.2.4 Pentobarbital versus Paraldehyde , 1 study (Kaim 1972), 96 participants, RR 0.37 (0.03 to 3.97), the result is not statistically significant

3.1.4 Chlormethiazole versus Pentobarbital , 1 study (Mariani 2006), 27 participants, RR 1.39 (0.28 to 7.05), the result is not statistically significant

See Analysis 3.2 or Figure 15

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 2 Dropout.

15.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2, outcome: 3.2 Dropout.

Comparison 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other drug) versus Other Drug:

Efficacy

4.1Alcohol withdrawal delirium

3 studies (Golbert 1967; Lucht 2003; Rothstein 1973), 311 participants, RR 0.79 (0.18 to 3.52), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 4.1 or Figure 16

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other, Outcome 1 Alcohol withdrawal delirium.

16.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other, outcome: 4.1 Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium post treatment.

Safety

4.2 Severe, life‐threatening adverse events

1 study, (Golbert 1967; ), 49 participants, RR 0.13 (0.02 to 0.89), the result is statistically significant in favour of the association Paraldehyde+ chloral hydrate in respect of chlordiazepoxide, see Analysis 4.2

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other, Outcome 2 Severe, life‐threatening adverse events.

Acceptability

4.3 Dropout

Three studies (Golbert 1967; Lucht 2003; Spies 1996), 267 participants, RR 0.56 (0.18 to 1.72), the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 4.3 or Figure 17

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other, Outcome 3 Dropout.

17.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other, outcome: 4.3 Dropout.

Comparison 5 (Anticonvulsant 1 + Other drug) versus Anticonvulsant 2

Efficacy

1 study( Croissant 2009), 56 participants, compared Oxcarbaxepine plus Tiapride versus Chlormethiazole. No alcohol withdrawal seizures or delirium happened in both groups. See Analysis 5.1 and Analysis 5.2

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 1 alcohol withdrawal seizures.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 2 alcohol withdrawal delirium.

Safety

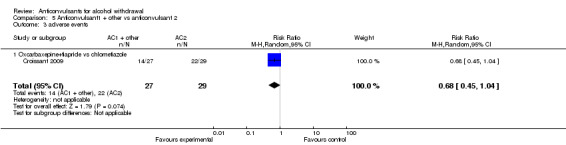

5.3. Adverse events

1 study (Croissant 2009) 56 participants, compared Oxcarbaxepine plus Tiapride versus Chlormethiazole, RR 0.68 (0.45 to 1.04) , the result is not statistically significant, see Analysis 5.3

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 3 adverse events.

5.4Severe, life‐threatening adverse events

1 study ( Croissant 2009), 56 participants, compared Oxcarbaxepine plus Tiapride versus Chlormethiazole. No severe adverse events happened in both groups.Analysis 5.4

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 4 severe, life threatening adverse events.

Acceptability

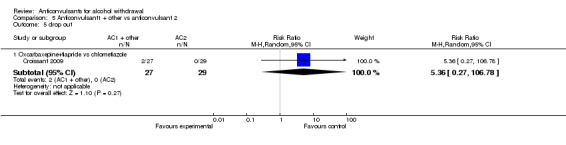

5.5 Drop out

1 study (Croissant 2009) 56 participants, compared Oxcarbaxepine plus Tiapride versus Chlormethiazole, RR 5.36 (0.27 to 106.78) the result is not statistically significant. See Analysis 5.5

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2, Outcome 5 drop out.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Fifty‐six studies, with a total of 4076 participants, met the inclusion criteria for this review. However, despite the considerable number of randomised controlled trials, the large variety of outcomes and rating scales considerably limited a quantitative synthesis of data. A large chunk of information could not be synthesized.

‐ No statistically significant differences were found in the four outcomes considered in the comparisons of anticonvulsants versus placebo. Anticonvulsant showed a potentially protective benefit against seizures. The adverse events were non‐significantly more common among the anticonvulsant‐treated patients, but the discontinuations due to adverse events tended to be more common in the placebo‐group. None of these trends, however, reached statistical significance.

‐ For the anticonvulsant versus other drug, results favour anticonvulsants only in one of the nine outcomes considered: comparing carbamazepine with benzodiazepine (oxazepam and lorazepam), results favour carbamazepine for alcohol withdrawal symptoms rated with CIWA‐Ar score. None of the other comparisons reached statistical significance. This can suggests that anticonvulsants and specifically carbamazepine may actually be more effective in treating some aspects of alcohol withdrawal when compared to benzodiazepines, the current first‐line regimen for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. The incidence of seizures tended to be more common among the participants that were treated with other drugs (e.g. benzodiazepines) than anticonvulsants, but delirium tremens favoured the other‐treatment participants. Adverse events showed a potentially better profile for the anticonvulsants.

‐ Comparing different anticonvulsants (2 outcomes considered), when carbamazepine was compared to Chlormethiazole the incidence of adverse events tended to be more common among the carbamazepine‐treated participants, whereas withdrawals tended to be more common among the Chlormethiazole participants. When carbamazepine was compared to barbital, the side effects were not statistically significant but more common among the carbamazepine patients, and no difference was found regarding the withdrawals between the compared drugs. Out of eleven studies comparing different anticonvulsant agents, no participant died during the treatment period.

‐ Comparing anticonvulsants plus other drugs versus other drugs (3 outcomes considered), results favour paraldehyde plus chloral hydrate versus chlordiazepoxide, for the severe‐life threatening side effects, but only one study, with four arms, and 72 participants was included in this comparison.

‐ Comparing anticonvulsant plus other drug versus another anticonvulsant, no significant difference were found in all the outcome considered (seizures, delirium, adverse events and drop out). But only one study with 56 participants, which compared oxcarbazepine plus Tiapride versus Chlormethiazolewas included in this comparison.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our review has some important limitations. First, most studies involve a very small sample size and have been conducted in different years, and in diverse patient populations.

Another potential limitation is the unavoidable grouping of drugs. All anticonvulsants were analysed together compared to the other drugs. Differences between specific anticonvulsant agents could not be seen, because of the limited number of studies comparing different anticonvulsants between themselves. Other drugs included a large variety of medicines such as benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, hypnotics, etc. These drugs do not belong to the same class and do not share the same mechanism of action. The grouping of all these drugs together, could have led to the loss of possibly important between‐drugs differences concerning effectiveness or safety. While we made an effort to address drug‐specific comparisons as well, these data are definitely more limited and even more inconclusive. It was also not possible to examine dose‐response effects, since participants were not treated with even similar doses of various anticonvulsants across RCTs. Moreover, data on side effects should be interpreted cautiously, as they were derived from participants with different co‐morbidity. Many trials tended to exclude participants in severe, medical conditions such as hepatic, heart or lung disease. However, these participants may be more sensitive to various adverse events of anticonvulsants or comparator drugs.

Quality of the evidence

Although randomisation was an inclusion criterion, indicating a degree of methodological quality for these studies, many of them are quite old, the mode of randomisation is not described, allocation of concealment is often unclear and information on follow‐up is frequently missing. On the other hand, this makes the meta‐analysis potentially more useful, since small trends that could not reach statistical significance due to the small number of participants in these trials, could now be revealed after the data synthesis. Also highlighting reporting deficits is important for improving future research.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Results of this review do not provide sufficient evidence in favour of anticonvulsants for the treatment of AWS. Anticonvulsants seem to have limited side effects, although adverse effects are not rigorously reported in the analysed trials.

Implications for research.

Although a significant number of trends has emerged, most of these were small and the data for most outcomes did not reach statistical significance; the need for further studies should be carefully evaluated on the basis of these findings. If these studies are going to be carried out, they should be limited to few important efficacy and safety measures such as the severity of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, the incidence of seizures and delirium tremens, side effects, withdrawals and mortality. In the case of continuous outcomes the same rating scale (e.g. CIWA‐Ar) should preferably be used, in order to have more comparable information across studies and to be able to estimate the real effect of all these agents.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 January 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | new studies founded |

| 7 January 2010 | New search has been performed | substantially updated; authors changed |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 3, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 March 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 13 April 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review is a substantial update of a previous version (Polycarpou 2005). The authors of the first version are not yet interested in updating this review that for that change the authorship.

Acknowledgements

We thank the author of the first version of the review that did an excellent work that was very helpful for this update and Zuzana Mitrova for providing helpful assistance during all the process

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

Free text: (((alcohol*) AND (withdraw* or detox* or abstinen* or abstain*)) AND (anticonvulsant*)))

Appendix 2. PubMed search strategy

Alcohol‐related disorders [mesh]

((alcohol*) and (disorder* or withdr* or abstinen* or abstain* or detox* or neuropathy)) [tiab]

Alcohol‐Induced Disorders, Nervous System [mesh]

1 or 2 or 3

ANTICONVULSANTS [Mesh]

anticonvulsant* [tiab]

(ACTH or carbamazepine or clorazepate or clobazam or clonazepam or chlordiazepoxide or divalproex or ethosuximide or ethosuccimide or ethotoin or felbamate or fosphenytoin or gabapentin or lignocaine or lamotrigine or Levetiracetam or lidocaine or hydantoins or levetiracetam or mephobarbital or methsuximide or oxcarbazepine or paraldehyde or phenacemide or phenytoin or pregabalin or primidone or succinimide or tiagabine or topiramate or valproate or vigabatrin or zonisamide) [tw]

5 or 6 or 7

randomized controlled trial[pt]

controlled clinical trial[pt]

random*[tiab]

placebo[tiab]

drug therapy[mesh]

trial[tiab]

groups[tiab]

9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15

animals [mesh]

humans [mesh]

animals NOT (17 and 18)

16 NOT 19

4 AND 8 AND 20

Anticonvulsants/adverse effects [mesh] or Anticonvulsants/poisoning [mesh] or anticonvulsants/toxicity [mesh] or Anticonvulsants/contraindications [mesh]

adverse effects [subheadings]

Drug toxicity [mesh]

“adverse effect*”[tiab]

“side effect* [tiab]

serious or safety or surveillance or adverse or toxicity or complication or tolerability [tiab]

22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27

4 AND 8 AND 28

29 NOT 19

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

exp alcohol withdrawal

exp withdrawal syndrome

((alcohol*) and (disorder* or withdr* or abstinen* or abstain* or detox* or neuropathy)).ti,ab

1 or 2 or 3

exp anticonvulsive agent/

(ACTH or carbamazepine or clorazepate or clobazam or clonazepam or chlordiazepoxide or divalproex or ethosuximide or ethosuccimide or ethotoin or felbamate or fosphenytoin or gabapentin or lignocaine or lamotrigine or Levetiracetam or lidocaine or hydantoins or levetiracetam or methsuximide or oxcarbazepine or paraldehyde or phenacemide or phenytoin or pregabalin or primidone or succinimide or tiagabine or topiramate or valproate or vigabatrin or zonisamide)

5 or 6

random*.ti,ab

placebo. Ti,ab

(singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab

crossover*.ti,ab

exp randomized controlled trial/

exp double blind procedure/

exp single blind procedure/

exp triple blind procedure/

exp crossover procedure/

exp Latin square design/

exp placebos/

exp multicenter study/

8/19

4 AND 7 AND 20

limit 21 to human

Appendix 4. CINAHL search strategy

MESH alcohol related disorders

MESH alcohol withdrawal delirium

TX ((alcohol*) and (disorder* or withdr* or abstinen* or abstain* or detox* or neuropathy))

1 or 2 or 3

MH ANTICONVULSANTS

MH Dipotassium

Valproic acid:ME

TX Acetazolamide or carbamazepine or Chlormethiazole or Clorazepate or Clorazepate or divalproex or or Ethosuximide or felbamate or fosphenytoin or gabapentin or lamotrigine or Levetiracetam or Metaclazepam or lidocaine or mephobarbital or lignocaine or methsuximide or oxcarbazepine or paraldehyde or pentobarbital or phenytoin or primidone or tiagabine or topiramate or valproate or vigabatrin or zonisamide

5 or 6 or 7 or 8

MH Random Assignment/

MH Clinical Trials/

TW random*

TW placebo*

TW group*

TW (singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) and (mask* or blind*)

MH crossover design

TW crossover*

TW allocate*

TW assign*

10/19 OR

4 and 9 and 20

Appendix 5. Criteria for risk of bias in RCTs and CCTs

| Item | Judgment | Description | |

| 1 | Was the method of randomization adequate? | Yes | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization |

| No | The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as: odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; hospital or clinic record number; alternation; judgement of the clinician; results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; availability of the intervention | ||

| Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. | ||

| 2 | Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Yes | Investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomization); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| No | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments because one of the following method was used: open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | ||

| Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement | ||

| 3/4 |

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? (blinding of patients, provider, outcome assessor) Objective outcomes Subjective outcomes |

Yes | Blinding of participants, providers and outcome assessor and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; Either participants or providers were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias. No blinding, but the objective outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| No | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken; Either participants or outcome assessor were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others likely to introduce bias |

||

| Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; | ||

| 5 |

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? For all outcomes except retention in treatment or drop out |

Yes | No missing outcome data; Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods All randomized patients are reported/analyzed in the group they were allocated to by randomization irrespective of non‐compliance and co‐interventions (intention to treat) |

| No | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomization; |

||

| Unclear | Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (e.g. number randomized not stated, no reasons for missing data provided; number of drop out not reported for each group); |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anticonvulsant versus Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Alcohol Withdrawal Seizures post treatment | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs. Placebo | 9 | 883 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.31, 1.20] |

| 1.2 Phenytoin vs. Placebo | 4 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.35, 1.77] |

| 2 Adverse events | 7 | 663 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.74, 3.31] |

| 3 Dropout | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs. Placebo | 7 | 344 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.50, 1.34] |

| 3.2 Chlormethiazole vs. Placebo | 3 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.22, 5.11] |

| 4 Dropout due to adverse events | 8 | 649 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.13, 3.36] |

Comparison 2. Anticonvulsant versus Other Drugs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Alcohol withdrawal seizures | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 12 | 880 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.22, 1.58] |

| 1.2 Chlormethiazole vs Benzodiazepine | 2 | 155 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.01, 8.33] |

| 2 Alcohol withdrawal delirium | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 6 | 394 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.23, 3.42] |

| 2.2 Carbamazepine vs Benzodiazepine | 2 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.04, 24.43] |

| 3 CIWA‐Ar score (48 hrs) | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs Other | 4 | 358 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.21 [‐0.95, 0.53] |

| 3.2 Carbamazepine vs. Benzodiazepine | 3 | 260 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.88, 0.67] |

| 4 CIWA‐Ar score (end of treatment) | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 4 | 358 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.73 [‐1.76, 0.31] |

| 4.2 Carbamazepine vs Benzodiazepine | 3 | 260 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.04 [‐1.89, ‐0.20] |

| 5 Global Doctor's Assessment of Efficacy | 2 | 181 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.88, 1.08] |

| 6 Adverse events | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 14 | 726 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.45, 1.12] |

| 6.2 Chlormethiazole vs Benzodiazepine | 5 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.35, 1.59] |

| 7 Severe, life‐treatening adverse events | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs anyOther | 12 | 578 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.38 [0.33, 17.24] |

| 7.2 Chlormethiazole vs. Benzodiazepine | 4 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.09, 5.33] |

| 8 Dropout | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 20 | 1359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.67, 1.26] |

| 8.2 Chlormethiazole vs Benzodiazepine | 5 | 311 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.37, 1.24] |

| 9 Dropout due to adverse events | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Any Anticonvulsant vs any Other | 10 | 596 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.28 [0.67, 7.70] |

| 9.2 Chlormethiazole vs Benzodiazepine | 4 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.12, 9.97] |

Comparison 3. Anticonvulsant 1 versus Anticonvulsant 2.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adverse events | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Carbamazepine vs. Chlormethiazole | 2 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.12 [0.50, 19.27] |

| 1.2 Carbamazepine vs. Barbital | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.81 [0.70, 4.68] |

| 1.3 Carbamazepine vs Oxcarbazepine | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.4 Chlormethiazole vs. Pentobarbital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.8 [0.12, 63.20] |

| 2 Dropout | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Carbamazepine vs. Chlormethiazole | 2 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.08, 3.11] |

| 2.2 Carbamazepine vs. Barbital | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.34, 2.57] |

| 2.3 Carbamazepine vs Oxcarbazepine | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.2 [0.14, 72.62] |

| 2.4 Pentobarbital vs. Paraldehyde | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.03, 3.97] |

| 2.5 Chlormethiazole vs. Pentobarbital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.28, 7.05] |

Comparison 4. (Anticonvulsant + Other) versus Other.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Alcohol withdrawal delirium | 3 | 311 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.18, 3.52] |

| 2 Severe, life‐threatening adverse events | 1 | 49 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.02, 0.89] |

| 3 Dropout | 3 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.18, 1.72] |

Comparison 5. Anticonvulsant1 + other vs anticonvulsant 2.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 alcohol withdrawal seizures | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.1 Oxcarbaxepine+tiapride vs chlometiazole | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 alcohol withdrawal delirium | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.1 Oxcarbaxepine+tiapride vs chlometiazole | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 adverse events | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.45, 1.04] |

| 3.1 Oxcarbaxepine+tiapride vs chlometiazole | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.45, 1.04] |

| 4 severe, life threatening adverse events | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.1 Oxcarbaxepine+tiapride vs chlometiazole | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 drop out | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Oxcarbaxepine+tiapride vs chlometiazole | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.36 [0.27, 106.78] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Agricola 1982.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | No. = 60; age = 20‐64 years (mean: 44.28) Inclusion criteria: alcoholic hospitalised patients with a severe withdrawal syndrome proceeding delirium tremens. Exclusion criteria: severe heart, liver or kidney diseases; use of psychotropic drugs; addicted or chronic abusers of other gender = 53 males; 7 females |

|

| Interventions | Group A (30) carbamazepine 200mg tid (no. = 30); Group B (30) Tiapride 200mg tid | |

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms; overall evaluation of the clinical condition; assessment of therapeutic effectiveness both by the doctor and the patient; blood pressure and heart rate; SGOT, SGPT; tolerability; seizures | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding? Objective outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes except withdrawal | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Alldredge 1989.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | No. = 90; gender = 85 males, 5 females; age = 30.3‐50.9. Inclusion criteria: patients admitted to the Emergency Department for a recent seizure occurred in the setting of acute withdrawal from alcohol. Exclusion criteria: history of seizures unrelated to alcohol use, severe head trauma, sedative or anticonvulsant use within 14 days, stimulant drug use within 3 days, significant electrolyte abnormalities, second‐or third‐degree atrioventricular heart block, bradycardia, or known hypersensitivity to hydantoin derivatives. |

|

| Interventions | Group A (45) diphenylhydantoin sodium 1000mg intravenously over 20 minutes; Group B (45) equivalent volume of 0.9% sodium chloride | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy : Seizure Recurrence; | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "patients were randomly assigned to receive either diphenylhydantoin sodium injection or infusion of an equivalent volume of 0.9% sodium chloride" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | "patients were randomly assigned to receive either diphenylhydantoin sodium injection or infusion of an equivalent volume of 0.9% sodium chloride" |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | study described as "double blind placebo controlled trial". "Both diphenylhydantoin and sodium chloride had an identical appearance" For patients with recurrent seizures, the treating physician could request that the study code be broken and subsequent treatment administered. Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Blinding? Objective outcomes | Low risk | study described as "double blind placebo controlled trial". "Both diphenylhydantoin and sodium chloride had an identical appearance" For patients with recurrent seizures, the treating physician could request that the study code be broken and subsequent treatment administered. Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes except withdrawal | Unclear risk | "Ninety eligible patients completed the study between October 1982 and June 1988" COMMENT: it is not reported if more than 90 patients were randomised during the study period but they did not complete the study |

Balldin 1986.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | No. = 38; Age = 28‐57 Inclusion criteria: Patients alcohol dependent (DMS‐III) Exclusion Criteria: somatic diseases; psychotic symptoms; use of alcohol together with sedatives and anxiolytics. |

|

| Interventions | Group A chlorprothixene 50mg x 3 daily+ Carbamazepin 200mg x 2 daily; Group B clonidine 300ìg x 2 daily | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: Psychiatric rating CPRS; mood: (pleasantness‐unpleasantness) and somatic symptoms (including symptoms in the abstinence situation but also side‐effects from the medication) (self‐rating scales developed by Sjoberg and Persson & Sjoberg were used) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "patients were treated either with alpha2 agonist clonidine or chlorprothixene" COMMENT: it was not stated if the study was randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | "patients were treated either with alpha2 agonist clonidine or chlorprothixene" COMMENT: it was not state if the study was randomised |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | "the design was double blind and double dummy". Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Blinding? Objective outcomes | Low risk | "the design was double blind and double dummy". Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes except withdrawal | Low risk | "two patients in the chlorprothixene group were excluded from day two and four in the clonidine group ". reason fro drop out given |

Bjorkqvist 1976.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | No. = 105; Gender: all male.; age 20‐60 years Inclusion criteria: out‐patients volunteers who sought treatment for alcohol withdrawal symptoms at five clinics; drinking for at least three days; cooperative; not in need of hospitalisation. Exclusion criteria: heart, liver, renal insufficiency; antihypertensive treatment; chronic narcotics; use of drugs |

|

| Interventions | Group A (34) carbamazepine; Group B (35) placebo | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: Symptoms related to abstinence; evaluation of the patient's global feelings; | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly allocated to two treatments" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly allocated to two treatments" |

| Blinding? subjective outcomes | Low risk | "a double blind technique was used". Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Blinding? Objective outcomes | Low risk | "a double blind technique was used". Blinding of outcomes assessor: it was not stated if the outcome assessor was blind, but because the outcomes were recorded during the treatment we judged that they were assessed by the blind personnel who gave the treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes except withdrawal | Low risk | 18 patients dropped out from the carbamazepine group and 18 from the the placebo group. Reason fro drop out given |

Blanchard 1985.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | No. = 38; Gender:29 males/9 females; Age: 38 years; Inclusion criteria: Hospitalized patients for alcohol withdrawal symptoms; severity score for AWS minimum of 2. |

|

| Interventions | Group A Atrium 300 mg; Group B (18) placebo | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy: Evaluation of global efficacy; Safety: side effects | |

| Notes | Study in French | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |