Abstract

This study harnesses machine learning to dissect the complex socioeconomic determinants of depression risk among older adults across five international cohorts (HRS, ELSA, SHARE, CHARLS, MHAS). Evaluating six predictive algorithms, XGBoost demonstrated superior performance in four cohorts (AUC 0.7677–0.8771), while LightGBM excelled in ELSA (AUC 0.9011). SHAP analyses identified self-rated health as the predominant predictor, though key factors varied notably—gender was especially influential in MHAS. Stratified analyses by income and sex revealed marked heterogeneity: wealth, employment, digital inclusion, and marital status exerted greater influence in lower-income groups, with distinct gender-specific patterns. These findings highlight machine learning’s capacity to reveal nuanced, context-dependent risk profiles beyond traditional models, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions that address the diverse vulnerabilities of aging populations, particularly those socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Subject terms: Psychology, Health care, Risk factors, Developing world, Social sciences

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent and debilitating mental disorder that disproportionately affects older adults, with estimates indicating that 10 to 20 percent of individuals aged 60 years and above experience clinically significant depressive symptoms1. This condition not only severely diminishes quality of life but also elevates suicide risk by nearly threefold, imposing substantial burdens on healthcare systems globally. The unique vulnerabilities of aging populations—such as comorbid chronic illnesses, social isolation, and functional decline—amplify the complexity and societal impact of depression in later life. As the global population ages rapidly, mental health challenges among middle-aged and older adults emerge as an urgent, cross-cultural public health crisis requiring targeted research and intervention2.

Concurrently, the world undergoes an unprecedented socioeconomic and demographic transformation characterized by sustained increases in gross domestic product (GDP) and household wealth3,4. These gains progressively alleviate absolute poverty, shifting public health focus toward relative poverty and its implications for health disparities5. The population aged 60 years and older is expected to double to 2.1 billion by 2050, intensifying the urgency to address the mental health needs of this demographic. Within this context of rapid socioeconomic change and accelerated population ageing, the nature and magnitude of risks vary substantially across income groups and between genders, with low income populations, particularly female, facing the most significant and multifaceted challenges, including heightened economic insecurity, limited access to healthcare, and greater social vulnerability6. These disparities underscore the importance of examining income as a key factor in heterogeneity analyses to better understand how socioeconomic status shapes mental health outcomes in aging populations7. Effectively addressing these disparities is essential to ensuring a sustainable future, making it imperative to prioritize the rights, health, and well-being of middle-aged and older adults through interventions tailored to mitigate depression risk across diverse income strata and gender.

Depression arises from a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors, creating multifaceted and dynamic relationships that traditional linear models often struggle to capture. This complexity, characterized by non-linear interactions and interdependencies among variables, highlights the need for advanced analytical methods capable of modeling such intricate patterns more effectively8,9. While conventional epidemiological approaches offer valuable insights, they frequently fall short in addressing the multifactorial and dynamic nature of depression’s determinants. This limitation underscores the need for innovative analytical methods capable of integrating complex, high-dimensional data to uncover subtle and context-specific patterns of risk. Recently, machine learning has emerged as a promising tool for mental health prediction10,11. However, the widespread clinical adoption of many machine learning algorithms remains constrained by their “black-box” nature, which limits interpretability and practical utility12. To overcome these barriers, advanced algorithmic frameworks that provide transparent and interpretable insights are essential to disentangle underlying mechanisms and identify potential heterogeneity in risk factors across diverse populations.

In response, we employ the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework alongside six ensemble learning algorithms(LightGBM, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, XGBoost, and AdaBoost) to construct an interpretable, cross-national predictive model of depressive symptoms in older adults. The SHAP framework provides a principled means to decompose model predictions into contributions from individual features, thereby illuminating complex, non-linear relationships while preserving interpretability. Drawing on cross-sectional data from five multinational aging cohorts, this methodology identifies both universal and culturally specific risk factors, alongside their effect thresholds, across diverse populations. These insights establish a rigorous, evidence-based foundation to inform global strategies aimed at mitigating depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults, with particular focus on income-related disparities and precision-targeted interventions.

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis of variables

The descriptive statistical analysis of key variables across 68,372 participants (depressive symptoms: n = 19,210, 28.10%; non-depressive symptoms: n = 49,162, 71.90%) is summarised in Supplementary Table 1, with country-specific data in Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Table 6. Age distribution showed 26.10% (n = 17,845) aged 50–59, 72.22% (n = 49,380) aged 60–89, and 1.68% (n = 1147) aged ≥90 (P < 0.001). Females (56.20%, n = 38,425) had a higher depressive symptoms risk (66.40%, n = 12,756) than males (43.80%, n = 29,947; 33.60%, n = 6454; P < 0.001). Unmarried individuals made up 32.86% of the sample but 39.86% of the depressive group, in contrast to the married subgroup (67.14% overall; 60.14% of depressive cases). Educational attainment and socioeconomic position were strongly associated with depression. Individuals with less than middle school education represented 53.89% of the total sample but 67.68% of those with depressive symptoms. Lower household wealth and income quartiles showed an increased prevalence of depressive symptoms: the lowest wealth quartile comprised 23.81% overall but accounted for 31.85% of depressive cases; the lowest income quartile (23.12% overall) represented 30.79% of the depressive group. Lifestyle and health-related factors displayed robust gradients. Employed participants (Working, 40.91%) constituted 39.51% of those with depressive symptoms. Never smokers (58.24% overall) and non-drinkers (51.52% overall) accounted for 60.76% and 63.59% of the depressive group, respectively. Strikingly, digital exclusion (54.91% overall) was even more pronounced among those with depressive symptoms (68.76%). These findings highlight significant socioeconomic and health disparities, necessitating targeted interventions.

Evaluation of model performance

We evaluated the performance of six machine learning algorithms—LightGBM, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, XGBoost, and AdaBoost—in predicting depressive symptoms risk among middle-aged and older adults across five international cohorts: the CHARLS, SHARE, HRS, MHAS, ELSA. The ROC plots for each international cohort are shown in Fig. 1, and performance metrics, including area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, precision, recall, and F-score, for internally and externally validated models are detailed in Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Table 9, Supplementary Table 10 and 11. Neural networks, while powerful, are typically better suited for unstructured data and require larger datasets and computational resources. To address class imbalance, we applied SMOTE and also evaluated model robustness on the original unbalanced data; performance metrics including AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for approaches are provided in the Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Table 13, Supplementary Table 14, Supplementary Table 15 and Supplementary Table 16.

Fig. 1. ROC curves of machine learning models in internal and external validation for each cohort.

The figure presents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrating the performance of the machine learning models during internal and external validation phases for each cohort. Panels (a–e) correspond to the SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS databases, respectively. The ROC curves plot sensitivity versus 1-specificity, illustrating the discriminative ability of the models to predict the target outcome. The area under the curve (AUC) values indicate the accuracy of the models, with higher AUC representing better predictive performance. This figure provides a comparative visualization of model efficacy across diverse population cohorts.

In CHARLS, XGBoost emerged as the optimal model, achieving an AUC of 0.7677, with an accuracy of 0.6686, precision of 0.5468, recall of 0.6146, and F-score of 0.5787. This outperformed other algorithms, such as Logistic Regression (AUC 0.7471, accuracy 0.6925, F-score 0.6201) and SVM (AUC 0.7511, accuracy 0.6964, F-score 0.6122), indicating XGBoost’s superior ability to capture complex patterns in the Chinese cohort. However, the relatively lower precision (0.5468) suggests potential challenges in identifying true positives, warranting further optimisation.

In SHARE, XGBoost also demonstrated the highest performance, with an AUC of 0.8577, accuracy of 0.7397, precision of 0.7650, recall of 0.7600, and F-score of 0.7625. This marked a substantial improvement over LightGBM (AUC 0.8418, F-score 0.7550) and other algorithms, such as Random Forest (AUC 0.7004, F-score 0.7220), reflecting XGBoost’s robustness in handling the diverse European population data. The high precision and recall indicate a balanced model capable of effectively distinguishing depressed from non-depressed individuals.

In HRS, XGBoost again performed best, recording an AUC of 0.8771, accuracy of 0.7397, precision of 0.8170, recall of 0.7890, and F-score of 0.8030. This outperformed LightGBM (AUC 0.8619, F-score 0.7825) and Logistic Regression (AUC 0.7747, F-score 0.7775), underscoring its efficacy in the US cohort. The high precision (0.8170) suggests strong positive predictive value, though the slightly lower recall (0.7890) indicates room for improvement in identifying all true cases of depressive symptoms.

In MHAS, XGBoost achieved the highest AUC of 0.7782, with an accuracy of 0.7397, precision of 0.7450, recall of 0.7343, and F-score of 0.7397. This surpassed LightGBM (AUC 0.7667, F-score 0.7483) and other models, such as SVM (AUC 0.7493, F-score 0.7447), demonstrating its suitability for the Mexican cohort. However, the moderate performance metrics suggest that cultural or data-specific factors may limit model generalisability, necessitating further refinement.

Conversely, in ELSA, LightGBM outperformed other algorithms, achieving an AUC of 0.9011, with an accuracy of 0.8975, precision of 0.8941, recall of 0.8943, and F-score of 0.8942. This exceeded XGBoost (AUC 0.8997, F-score 0.8902) and Logistic Regression (AUC 0.7641, F-score 0.7533), indicating LightGBM’s superior discriminative and balanced performance in the English cohort. The near-perfect metrics suggest a highly effective model, potentially due to the specific data structure or health system characteristics of ELSA.

Across cohorts, XGBoost consistently demonstrated robust performance in CHARLS, SHARE, HRS, and MHAS, with AUC values ranging from 0.7677 to 0.8771, reflecting its adaptability to diverse ageing populations. LightGBM’s exceptional performance in ELSA (AUC 0.9011) highlights its efficiency in handling the unique features of the English dataset. Other algorithms, such as Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest, and AdaBoost, showed variable performance, with AUCs ranging from 0.6498 to 0.7973, generally inferior to XGBoost and LightGBM. These findings underscore the importance of algorithm selection tailored to cohort-specific characteristics, while the variability in precision and recall across models suggests opportunities for further optimisation, particularly in balancing sensitivity and specificity. Notably, the F1 score of the XGBoost model trained on the CHARLS dataset was modestly lower than those observed in other cohorts, revealing variations in model performance across culturally distinct populations. This discrepancy likely reflects two key factors. First, certain predictors exhibit reduced effectiveness within the Chinese elderly population, as measures such as self-rated health may embody unique cultural interpretations and social contexts that influence their predictive power. Second, although SMOTE was employed to mitigate class imbalance—leading to marked improvements in recall and F1 score—the inherent overlap between positive and negative cases in the feature space may have limited the simultaneous enhancement of precision and recall, ultimately constraining the F1 metric. These observations highlight the complexities involved in applying machine learning models across diverse populations and emphasize the importance of tailoring feature selection and model tuning to cohort-specific characteristics. The findings indicate that the SHAP framework enables model interpretability in all cohorts, providing critical insights into the socioeconomic gradients and multifactorial drivers of depressive symptoms risk.

Sample characteristics

We employ the SHAP method, a unified framework for interpreting machine learning models13,14, to quantify the contribution of individual factors to the prediction of depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults. The SHAP value, derived from cooperative game theory, represents the marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s output, providing both local (individual prediction) and global (overall feature importance) interpretability. We calculate SHAP values using the Python SHAP package, generating feature importance summary plots (Fig. 2a–e), illustrating the directional impact of each feature on the predicted probability of depressive symptoms. Across five longitudinal aging datasets, we identify consistent and divergent patterns in the key determinants of depressive symptoms in descending order.

Fig. 2. SHAP analysis of the best machine learning model prediction in each cohort.

This figure displays the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis results for the top-performing machine learning model in each cohort. Each horizontal row corresponds to an individual feature, and the x-axis represents the SHAP value, which quantifies the impact of that feature on the model’s prediction. Panels (a–e) represent the SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS databases, respectively. Data points are color-coded, with red indicating higher feature values and blue indicating lower values, allowing visualization of the direction and magnitude of feature influence. This analysis provides interpretability by identifying key predictors driving model decisions.

In SHARE, the 15 features include self-rated health, gender, chronic disease status, educational attainment, household income quartile, marital status, alcohol consumption, IADL limitations, household wealth quartile, work status, digital exclusion, smoking status, physical activity, ADL limitations, and age in descending order.

In MHAS, the top 15 features include gender, chronic disease status, ADL limitations, age, work status, alcohol consumption, marital status, self-rated health, educational attainment, digital exclusion, household income quartile, household wealth quartile, physical activity, smoking status, and IADL limitations in descending order.

In ELSA, the 15 features include self-rated health, gender, marital status, work status, chronic disease status, household income quartile, educational attainment, household wealth quartile, age, digital exclusion, smoking status, physical activity, IADL limitations, ADL limitations, and alcohol consumption in descending order.

In HRS, the 15 features include self-rated health, marital status, age, chronic disease status, educational attainment, gender, household income quartile, ADL limitations, digital exclusion, household wealth quartile, work status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and IADL limitations in descending order.

In CHARLS, the 15 features include self-rated health, gender, IADL limitations, age, chronic disease status, ADL limitations, household wealth quartile, work status, physical activity, educational attainment, marital status, digital exclusion, household income quartile, alcohol consumption, and smoking status in descending order.

While self-rated health, chronic disease status, functional limitations (ADL and IADL), and socioeconomic factors (income, wealth, education) consistently emerge as important predictors across datasets, the relative importance of demographic factors (age, gender, marital status) and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, digital exclusion) varies. This variation highlights the potential influence of cultural and contextual factors on the determinants of depressive symptoms in later life.

Importance of characteristics

Figure 3 presents SHAP-derived feature contribution scores across cohorts, revealing distinct hierarchies of depressive symptoms risk determinants among middle-aged and older adults. Notably, self-rated health (shlt) emerges as the strongest predictor in SHARE (SHAP: +0.77), ELSA ( + 0.63), HRS ( + 0.81), and CHARLS ( + 0.50), underscoring its central role in shaping depression risk. In contrast, gender (ragender) dominates in MHAS ( + 0.31), highlighting regional and cultural differences. Other features such as age (agey) show minimal contributions in SHARE ( + 0.05), instrumental activities of daily living (iadl) in MHAS ( + 0.04), physical activity (actx) in ELSA ( + 0.10) and HRS ( + 0.13), and digital exclusion in CHARLS ( + 0.05), reflecting cohort-specific variations in risk factor importance. These differences emphasize the influence of socioeconomic and cultural contexts on the prioritization of depression determinants15,16.

Fig. 3. Feature importance values predicted by the best machine learning model for each cohort.

This figure illustrates the relative importance of features as determined by the best-performing machine learning model within each cohort. Panels (a–e) correspond to the SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS databases, respectively. Feature importance scores reflect the contribution of each variable to the predictive accuracy of the model. The figure highlights the most influential predictors across different cohorts, offering insights into cohort-specific factors that significantly affect the outcome. This comparative analysis aids in understanding variable relevance and potential heterogeneity among populations.

Building on this, the dominant role of self-rated health likely reflects its integrative function as a nexus between objective health status and psychosocial factors that collectively influence depressive symptoms. Poor self-rated health not only signals the presence of chronic diseases and functional impairments (ADL/IADL limitations) but also captures individuals’ subjective appraisal of their overall well-being, which shapes behavioral responses and coping strategies17. This appraisal can exacerbate or mitigate risk by influencing lifestyle factors such as physical activity18, social engagement19, and healthcare utilization20. Furthermore, self-rated health mediates the impact of socioeconomic disadvantages by modulating how individuals perceive and respond to stressors such as financial hardship, work instability, and digital exclusion21,22. In this way, it acts as a pivotal intermediary that amplifies the effects of secondary risk factors, creating a cascading pathway toward depressive symptoms. The variation observed in MHAS, where gender supersedes self-rated health as the leading predictor, underscores how cultural norms and gender roles can reshape these pathways, highlighting the necessity of contextualizing depression risk within socio-cultural frameworks23. Together, these findings position self-rated health not merely as a predictor but as a dynamic construct that interlinks biological, psychological, and social determinants of mental health across diverse populations.

Heterogeneity analysis

To explore income-related heterogeneity in predicting depressive symptoms risk among middle-aged and older adults across multiple cohorts, we stratify participants by household income quartiles (itot_quartile) using SHAP values. We categorize income into high (≥75th percentile), middle (25th–75th percentile), and low (≤25th percentile) groups and calculate the average contribution of each feature to model predictions within these strata. The analysis focuses on the top 15 most influential features per cohort, allowing us to examine how feature importance varies by income level and to capture nuanced differences in predictive patterns24. Figure 4 presents these stratified results alongside sample sizes for each subgroup. Notably, gender differences in feature importance also emerge across income strata. Stratified analyses reveal both consistent and divergent patterns of feature importance across the five datasets.

Fig. 4. Income heterogeneity of the sample across income levels in each cohort.

This figure depicts the distribution and heterogeneity of income levels within the sample populations of each cohort. Panels (a–e) represent the SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS databases, respectively. The figure shows how income varies across different subgroups within each cohort, revealing patterns of economic diversity and stratification. This visualization helps to contextualize the socioeconomic background of participants and assess how income disparities may influence study outcomes or model predictions.

In SHARE, self-rated health (shlt) consistently ranks as the strongest predictor across all income groups, with slightly higher importance in low-income (+0.79) and high-income (+0.76) households compared to middle-income (+0.76). Conversely, age (agey) remains the least influential feature regardless of income. Secondary factors such as household wealth (atotb_quartile), smoking (smoke), and ADL limitations (adl) gain prominence in lower-income groups, suggesting that material deprivation and functional impairments disproportionately affect depressive symptoms risk among economically disadvantaged individuals.

In MHAS, gender (ragender) dominates as the top predictor across income levels, with the highest contribution in low-income (+0.34) and high-income (+0.30) groups, and slightly lower in middle-income (+0.29). Functional limitations measured by ADL (adl), work status (work), and alcohol consumption (drink) are more influential in the low-income group, highlighting the compounded vulnerabilities faced by this population segment. IADL limitations (iadl) consistently exhibit minimal influence across income strata.

In ELSA, self-rated health (shlt) is the predominant predictor across income groups, with the strongest effect in high-income households (+0.78), followed by middle (+0.64) and low-income (+0.49) groups. Gender (ragender) and household wealth (atotb_quartile) show increased importance in lower-income households, indicating that socioeconomic disadvantage amplifies the impact of these factors. Physical activity (actx) consistently ranks among the least important features.

In HRS, self-rated health (shlt) again emerges as the most critical predictor, with the highest importance in high-income (+0.86) and middle-income (+0.81) groups, and slightly lower in low-income (+0.76) households. Marital status (mstath), gender (ragender), digital exclusion (internet), household income (itot_quartile), age (agey), and work status (work) are more salient in lower-income groups, underscoring the multifaceted nature of socioeconomic influences on depressive symptoms risk. Physical activity (actx) remains consistently less influential.

Finally, in CHARLS, self-rated health (shlt) maintains its leading role with nearly equal contributions across income groups (all approximate +0.50). Digital exclusion (internet) is the least important feature regardless of income. Work status (work), household wealth (atotb_quartile), and marital status (mstath) have relatively greater influence in the low-income group, emphasizing socioeconomic vulnerabilities beyond income alone.

These findings collectively demonstrate that the relationship between socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms risk is complex and multifactorial. While self-rated health consistently dominates as a predictor, the relative influence of wealth, employment, functional limitations, and digital inclusion varies significantly by income level and cohort context. This heterogeneity highlights that vulnerability to depressive symptoms extends beyond income, involving an interplay of material, social, and behavioral factors25. Consequently, targeted interventions must be tailored to address the specific socioeconomic vulnerabilities most relevant to each population subgroup rather than applying uniform strategies. A comprehensive assessment of mental health risk requires considering a multidimensional spectrum of disadvantage—including household wealth, employment status, digital access, and social factors such as marital status—across income strata. Understanding how these factors interact with health behaviors over the life course and their underlying causal pathways is essential for developing effective, context-sensitive prevention and intervention strategies to reduce depressive symptoms risk.

To elucidate gender-specific patterns in depressive symptoms risk, we conduct a stratified analysis using the best-performing machine learning models across multiple cohorts. Given well-established sex and gender differences in depression prevalence and risk factors, examining heterogeneity by gender is essential to identify distinct determinants that may inform tailored intervention. Using SHAP values, we compare the relative contributions of the top 15 predictive features separately for females and males within each cohort, revealing gender-specific variations in biological, socioeconomic, and behavioral influences. The relevant structures are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Gender heterogeneity of the sample across income levels in each cohort.

This figure presents the gender distribution across different income levels within each cohort sample. Panels (a–e) correspond to the SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS databases, respectively. The figure illustrates variations in gender representation within income strata, highlighting potential gender-related socioeconomic differences. Understanding gender heterogeneity is critical for interpreting model results and ensuring that predictive models account for demographic diversity.

In SHARE, self-rated health (shlt) emerges as the most influential predictor for both females (+0.74) and males (+0.81), with a slightly greater effect in males. Chronic disease status (chronic) and educational attainment (raeducl) contribute similarly across sexes. Functional limitations (IADL) and lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption (drink) and smoking (smoke) show modest gender differences, with smoking more relevant in males (+0.13) than females (+0.08). Marital status (mstath) and household wealth (atob_quartile) show slightly higher importance in females.

In MHAS, chronic disease (chronic) ranks highest among females (+0.31). ADL limitations (adl) and age (agey) rank highly in both sexes but exert greater influence in females. Work status (work), alcohol consumption (drink), and marital status (mstath) weigh more heavily in males, while self-rated health (shlt) contributes marginally more in males (+0.18) than females (+0.15). Digital exclusion (internet) shows slightly higher importance in females.

In ELSA, self-rated health (shlt) is a dominant predictor for both females (+0.61) and males (+0.67). Marital status (mstath) and work status (work) contribute more in males, whereas chronic disease (chronic) carries greater weight in females. Socioeconomic factors such as household income (iot_quartile) and wealth (atob_quartile) maintain comparable importance across sexes. Lifestyle factors including smoking (smoke) and physical activity (actx) show minimal gender variation.

In HRS, self-rated health (shlt) dominates for both females (+0.84) and males (+0.77), with marital status (mstath) and age (agey) also highly influential. Chronic disease (chronic), educational attainment (raeducl), and digital exclusion (internet) contribute similarly across sexes, while work status (work) and smoking (smoke) weigh more in males.

Finally, in CHARLS, self-rated health (shlt) leads for both females (+0.49) and males (+0.52). Functional limitations (IADL and ADL) maintain similar importance across sexes, though work status (work) is more relevant in females. Socioeconomic factors such as education (raeducl) and household wealth (atob_quartile) show modest gender differences, with smoking and digital exclusion (internet) contributing least in both groups.

These gender-stratified analyses demonstrate that self-rated health consistently ranks as the primary predictor of depressive symptoms risk across sexes, while the importance of functional limitations, socioeconomic factors, and lifestyle behaviors varies. These nuanced gender differences underscore the necessity of gender-sensitive approaches in depression risk assessment and intervention design.

This study employs SHAP values within a machine learning framework to elucidate depressive symptoms risk among middle-aged and older adults, advancing beyond conventional regression-based approaches26,27. By stratifying data by household income and gender using SHAP’s cohort method, the analysis reveals differential contributions of predictors, including self-rated health (shlt), household wealth (atotb_quartile), and digital exclusion (internet), across income groups in SHARE, ELSA, HRS, and CHARLS datasets. This approach captures non-linear relationships and interactions, offering granularity absent in traditional models. Unlike prior studies that applied feature importance without SHAP28,29, the current methodology provides interpretable insights into how socioeconomic context modulates predictor influence.

Self-rated health consistently emerged as the dominant predictor across all income strata, aligning with findings from multiple cohorts30,31. This relationship operates through several key mechanisms. Poor self-rated health creates a psychological framework where individuals interpret their circumstances more negatively, amplifying the impact of stressors like financial difficulties and social isolation32,33. Additionally, those reporting poor self-rated health often reduce physical activity and social engagement, behaviors that independently contribute to depressive symptoms34. The cognitive aspect is particularly important - self-rated health functions as a comprehensive assessment that integrates both physical symptoms and emotional well-being, creating a feedback cycle where negative health perceptions worsen mood and vice versa35,36. However, secondary factors, including household wealth, work status, and digital exclusion, exhibited pronounced influence in lower-income households, particularly in HRS and CHARLS. These results extend the work of Church et al. by identifying specific socioeconomic vulnerabilities, such as material deprivation and limited digital access, that amplify depressive symptoms risk in economically disadvantaged groups37.

Regarding socioeconomic pathways, our findings suggest multiple mechanisms at work, with notable gender differences. Financial strain directly limits access to healthcare and creates chronic stress from uncertainty about meeting basic needs38,39. Female, particularly in medium-income households, often face compounded challenges due to economic instability, which exacerbates gender-specific vulnerabilities such as role conflict and increased caregiving burdens40,41. Beyond material constraints, lower socioeconomic status reduces social capital and community resources, leading to isolation and reduced coping mechanisms, effects that disproportionately impact female42. In contrast, high-income groups showed greater sensitivity to self-rated health, suggesting subjective health perceptions dominate when material needs are met, consistent with findings on life satisfaction’s varying impact43,44.

In the MHAS dataset, gender (ragender) was the strongest predictor, with a larger effect in medium-income households (+0.38) compared to high (+0.34) and low-income (+0.33) groups. This income-mediated gender effect diverges from studies treating gender as a uniform risk factor45, highlighting how economic instability in medium-income households exacerbates gender-specific vulnerabilities. Female in medium-income households face particular challenges - they often lack both the financial security of higher-income families and the community support networks common in lower-income areas46. This creates a “squeezed middle” effect where traditional gender roles persist but economic pressures intensify, leading to role conflict and stress47. These findings underscore the limitations of universal predictive models and advocate for interventions tailored to gender and socioeconomic status, aligning with gender-stratified analyses in prior CHARLS research48,49.

Discussion

Compared to prior research, this study’s integration of SHAP-based income stratification reveals patterns overlooked by traditional models. For instance, while Lo et al. 50 identified broad socioeconomic determinants, they did not explore income-level variations or interactions with health behaviors like smoking, which were more influential in lower-income groups in SHARE and MHAS. Similarly, Montorsi et al. 51 used SHAP to identify old adults conditions and education as predictors but did not stratify by income, limiting its ability to capture socioeconomic heterogeneity. Our current approach enhances model interpretability, offering actionable insights for policymakers through a multidimensional prevention strategy integrating economic, social, and technological interventions. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to elucidate causal pathways, building on the retrospective cohort approach. These efforts would advance the current findings, fostering a comprehensive understanding of socioeconomic influences on depressive symptoms risk in middle-aged and older adults. This study underscores the necessity of context-specific strategies targeting the unique vulnerabilities of different income groups, paving the way for equitable and effective depressive symptoms risk interventions.

Nevertheless, a comprehensive interpretation of these findings necessitates an acknowledgement of the study’s inherent constraints. This study has three main limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference and the ability to track changes in depressive symptoms over time; longitudinal studies with repeated measures are needed to clarify trajectories and mechanisms. Second, the analysis includes only fifteen individual-level variables, with limited justification for their selection, while important contextual factors such as healthcare access, insurance, family dynamics, and social policies are not considered due to data unavailability and lack of standardization across countries. Third, differences in social security systems and policy frameworks across nations, such as between China and others, hinder harmonization of structural variables, restricting comprehensive multinational comparisons. Future research would benefit from addressing these gaps by incorporating more comprehensive contextual data and adopting longitudinal designs to enhance the understanding of depression risk among aging populations.

Ultimately, the insights derived from this investigation underscore a critical pathway forward for precision public health. In summary, this study leverages advanced machine learning techniques across five multinational aging cohorts to robustly predict depressive symptoms risk and elucidate its complex socioeconomic determinants. Our findings demonstrate the superior performance of ensemble algorithms, particularly XGBoost and LightGBM, while the SHAP framework provides transparent interpretability, revealing self-rated health as a universal and dominant predictor alongside cohort- and income-specific variations. The stratified analyses underscore the heterogeneity of depression risk profiles shaped by income and gender, highlighting the critical need for tailored, context-sensitive interventions that address multifaceted vulnerabilities in aging populations. Collectively, these results advance the precision public health agenda by offering actionable insights to inform equitable depression prevention strategies globally, emphasizing the importance of integrating socioeconomic, behavioral, and health factors in predictive modeling.

Methods

Study participants

In this population-based, cross-national cohort study, we utilised cross-sectional data from five cohorts comprising adults aged 50 years and older across 16 countries: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS, Wave 14), English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA, Wave 8), Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, Wave 7), China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS, Wave 4), and Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS, Wave 5). The primary study population included participants aged 50 years and older, with the following exclusion criteria applied: (1) participants lacking data on depressive symptoms symptom variables; (2) individuals with more than 20% missing data in individual variables; and (3) participants not reporting any chronic conditions in the respective wave. Chronic conditions were self-reported physician-diagnosed diseases, encompassing stroke, hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease, heart disease, dyslipidemia, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, gastric disorders, mental disorders, arthritis, rheumatoid diseases, respiratory conditions, memory disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and cataracts. Following these exclusions, the final sample comprised 68,372 participants: 16,045 from HRS, 7864 from ELSA, 13,927 from SHARE, 15,963 from CHARLS, and 14,573 from MHAS. This harmonised approach ensures a robust representation of middle-aged and older adults across diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of depressive symptoms risk determinants.

Variables and definitions

Drawing on existing literature52–54, our candidate variables encompassed: (1) demographic characteristics, including age (agey), gender (ragender), marital status (mstath), education level (raeducl), household total wealth (atotb_quartile), household total income (itot_quartile), and employment status (work); (2) lifestyle factors, such as smoking (smoke), drinking (drink), physical activity (actx), and digital exclusion (internet); and (3) health status indicators, comprising self-rated health (shlt), activities of daily living (ADL) assessed across items (adl), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) assessed across items (iadl), and all chronic diseases reported in each cohort’s survey data (chronic), defined as self-reported physician-diagnosed conditions.

To investigate the determinants of depressive symptoms risk among middle-aged and older adults and examine their economic heterogeneity, we employed a binary outcome variable, depressive symptoms risk (Depressive symptoms), defined as the presence (Yes = 1) or absence (No = 0) of risk. This was assessed using cohort-specific, validated depressive symptom scales across five international cohorts—CHARLS, SHARE, HRS, MHAS, and ELSA. Specifically, depressive symptoms risk was defined as follows: CESD-8 scores ≥ 3 for HRS and ELSA; CESD-10 scores ≥ 10 for CHARLS; Euro-D scale scores ≥ 4 for SHARE; and CESD-9 scores ≥ 5 for MHAS. Scores below these thresholds indicated no depressive symptoms risk (No = 0).The robust correlation between EURO-D and CESD, as established in prior literature55, underpins the comparability of these measures, ensuring the harmonised binary classification despite scale variations. These thresholds, grounded in psychometric validation, facilitate a consistent assessment of depressive symptoms prevalence, enabling cross-cohort analysis of its socioeconomic determinants.

We harmonised key variables across five cohorts to ensure consistency for depressive symptoms risk prediction (Supplementary Table 17). Reference to existing literature on the method of setting depression thresholds for multi country cohorts56–59. Due to these fundamental differences in scoring methods, the cutoff thresholds for depressive symptoms naturally differ. Independent variables included age (50 ≤ age < 60 = 1, 60 ≤ age < 90 = 2, age ≥ 90 = 3), gender (Female = 0, Male = 1), marital status (Not married/other = 0, Married = 1), education (Less than middle school = 1, High school = 2, Higher education = 3), household wealth and income (quartiles, lowest = 4, highest = 1), and employment status (Unemployed = 1, Retired = 2, Working = 3), with minor adaptations for cohort-specific contexts. Lifestyle factors (smoking, drinking, physical activity) and health status indicators were standardised, including self-rated health (Poor = 1, Fair = 2, Good/Very Good = 3). Activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were each consolidated into a single binary variable, with difficulty in any task coded as 1 and no difficulty as 0, harmonised across cohorts despite minor variations in item phrasing. The chronic disease count was derived from self-reported data, categorising no chronic diseases as 1, one chronic disease as 2, and two or more chronic diseases as 3, ensuring consistency despite differences in reporting formats. Digital exclusion was dichotomised as None = 0 and Exists = 1, based on internet or email use frequency, with slight temporal variations58.

Data preprocessing

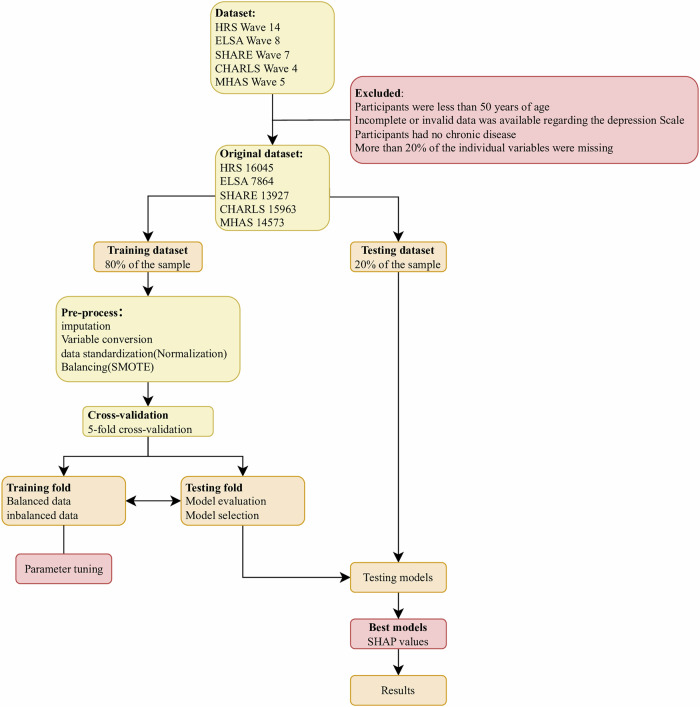

The workflow for data preprocessing and model development is illustrated in Fig. 6. Feature engineering was a critical step prior to model training, aimed at enhancing model robustness and generalizability by systematically transforming raw data into representations more amenable to learning. This process encompassed data cleaning, feature selection, and feature transformation. Specifically, redundant and irrelevant variables were identified and excluded to mitigate overfitting and reduce the curse of dimensionality, thereby improving predictive performance across cohorts. In selecting variables for the depressive symptoms risk prediction models, we leveraged existing literature alongside data availability from five publicly accessible aging cohorts to ensure cross-cohort comparability. Variable definitions were carefully harmonized to reflect cohort-specific nuances while maintaining scientific consistency. Following the isolation of the test set, variables were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: missing data exceeding 20% of participants, zero variance, or lack of statistical significance in univariate analyses. Ultimately, 15 features were retained for model development.

Fig. 6. Flowchart of the combined prediction study in each cohort.

This figure illustrates the step-by-step flowchart of the study design used to develop and validate the combined and overall prediction models across multiple cohorts. It details the data preprocessing, feature selection, model training, internal validation, and external validation processes applied to each cohort dataset. The flowchart highlights the integration of five cohort databases (SHARE, MHAS, ELSA, HRS, CHARLS) and the sequential steps to ensure robust machine learning model development and evaluation. This visual guide provides a comprehensive overview of the methodology, ensuring reproducibility and clarity of the study workflow.

To ensure consistency across cohorts, feature construction involved standardization and recoding of variables according to predefined criteria. To address missing data, we implemented a multiple imputation approach, which minimises potential bias that could arise from excluding participants with incomplete records, ensuring a more representative sample and preserving statistical power. Additionally, the distribution of depressed patients in our dataset exhibited significant imbalance, potentially compromising the performance of classification models60. To rectify this, we employed the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), a widely validated oversampling method61, to generate synthetic instances of the minority class (depressive symptoms), thereby achieving a balanced distribution. This approach, extensively applied in handling imbalanced datasets, enhances model sensitivity and predictive accuracy for depressive symptoms risk across diverse populations62.

Predictive model development and evaluation

For each cohort, the dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%). We employed six machine learning algorithms—LightGBM, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, XGBoost, and AdaBoost—to develop these models, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of predictive performance.

Ensemble learning harnesses the collective strength of multiple algorithms to enhance predictive accuracy and robustness. Our approach integrates six complementary machine learning methods: LightGBM, a highly efficient gradient boosting framework; Logistic Regression, a classical probabilistic model; Support Vector Machine(SVM), which delineates optimal decision boundaries; Random Forest, an aggregation of decision trees; XGBoost, an optimized gradient boosting implementation; and AdaBoost, which iteratively emphasizes difficult cases to improve classification.

Model parameters were iteratively optimised, with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves serving as the primary criterion for selecting optimal parameter values, thereby ensuring local optima in model performance. The final parameter combinations for each algorithm were determined through a 5-fold cross-validation strategy coupled with grid search, enhancing robustness and generalisability. Subsequently, the trained models were validated on the respective testing sets, and performance was assessed using a suite of evaluation metrics: ROC curve area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, recall, F1-score, and precision, with each metric ranging from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate superior model performance. To further elucidate the determinants of depressive symptoms risk, we applied SHAP value analysis to interpret and visualise the contributions of predictive features in the optimal model for each cohort, facilitating a transparent understanding of their impact on depressive symptoms risk. Hyperparameter settings for the optimal model in each of the five surveys are shown in Supplementary Table 18. And the samples selection process for the cross-sectional data are as follows in Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71874059).

Author contributions

C.L. was responsible for software development, contributed to drafting the original manuscript, and participated in manuscript review and editing. S.W.W. oversaw the conceptualization and design of the study, co-drafted the original manuscript, and contributed to manuscript revision and editing. Z.Y.L. performed the formal statistical analysis and assisted with critical review and editing of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the underlying data reported in the manuscript and verified its accuracy. They collectively contributed to the interpretation of results and were involved in manuscript writing.

Data availability

Deidentified individual participant data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Quantitative analysis and modelling was performed in Python v3.11.7 and made use of the following packages: numpy, pandas, sklearn, imblearn,lightgbm, XGBoost, matplotlib,shap. Code will be made available upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Can Lu, Shenwei Wan.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41746-025-01905-7.

References

- 1.Li, S. et al. Uncovering the heterogeneous effects of depression on suicide risk conditioned by linguistic features: A double machine learning approach. Comput. Hum. Behav.152, 108080 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirico, A. et al. Exploring the Psychological Nexus of Virtual and Augmented Reality on Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Rapid Review. Behav. Sci.14, 31 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu Hatab, A., Cavinato, M. E. R., Lindemer, A. & Lagerkvist, C.-J. Urban sprawl, food security and agricultural systems in developing countries: A systematic review of the literature. Cities94, 129–142 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tu, W.-J., Zeng, X. & Liu, Q. Aging tsunami coming: the main finding from China’s seventh national population census. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.34, 1159–1163 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelsen, A. et al. Environmental Income and Rural Livelihoods: A Global-Comparative Analysis. World Dev.64, S12–S28 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liou, L. et al. Assessing calibration and bias of a deployed machine learning malnutrition prediction model within a large healthcare system. Npj Digit. Med.7, 149 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuaid, R. J., Cox, S. M. L., Ogunlana, A. & Jaworska, N. The burden of loneliness: Implications of the social determinants of health during COVID-19. Psychiatry Res.296, 113648 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma, R. et al. Association between composite dietary antioxidant index and coronary heart disease among US adults: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health23, 2426 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen, M. K. et al. Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. Neuropsychopharmacology44, 1328–1334 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce, D. W., Kormilitzin, A., Smith, K. A. & Cipriani, A. Explainable artificial intelligence for mental health through transparency and interpretability for understandability. Npj Digit. Med.6, 6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, T., Schoene, A. M., Ji, S. & Ananiadou, S. Natural language processing applied to mental illness detection: a narrative review. Npj Digit. Med.5, 46 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, Y. et al. An interpretable machine learning framework for measuring urban perceptions from panoramic street view images. iScience26, 106132 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nohara, Y., Matsumoto, K., Soejima, H. & Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed.214, 106584 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodríguez-Pérez, R. & Bajorath, J. Interpretation of Compound Activity Predictions from Complex Machine Learning Models Using Local Approximations and Shapley Values. J. Med. Chem.63, 8761–8777 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenya, R., Jiang, Y., Sampene, A. K. & Zhu, J. Food security in sub-Sahara Africa: Exploring the nexus between nutrition, innovation, circular economy, and climate change. J. Clean. Prod.438, 140805 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, X. et al. What is the potential to improve food security by restructuring crops in Northwest China?. J. Clean. Prod.378, 134620 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian, L. M. et al. Poorer self-rated health is associated with elevated inflammatory markers among older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology36, 1495–1504 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Angel, V. et al. Digital health tools for the passive monitoring of depression: a systematic review of methods. Npj Digit. Med.5, 3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chancellor, S. & De Choudhury, M. Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: a critical review. Npj Digit. Med.3, 43 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong, S. O. K., Pedron, S., Abdelmalak, N., Laxy, M. & Stephan, A.-J. An umbrella review of effectiveness and efficacy trials for app-based health interventions. Npj Digit. Med.6, 233 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailis, D. S., Segall, A., Mahon, M. J., Chipperfield, J. G. & Dunn, E. M. Perceived control in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral resources for health. Soc. Sci. Med.52, 1661–1676 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mäntyselkä, P. T. Chronic Pain and Poor Self-rated Health. JAMA290, 2435 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emmelin, M. et al. Self-rated ill-health strengthens the effect of biomedical risk factors in predicting stroke, especially for men – an incident case referent study. J. Hypertens.21, 887–896 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feigin, V. L. et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet383, 245–255 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuijpers, P. et al. Psychotherapy for Depression Across Different Age Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry77, 694 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, X., Ge, T., Dong, Q. & Jiang, Q. Social participation, psychological resilience and depression among widowed older adults in China. BMC Geriatr.23, 454 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang, S. et al. Research on grandchild care and depression of chinese older adults based on CHARLS2018: the mediating role of intergenerational support from children. BMC Public Health22, 137 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, M. R. et al. Using Machine Learning to Classify Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder Based on Treatment Seeking Status. EClinicalMedicine12, 70–78 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu, Y. & Ma, X. Using machine learning models to identify the risk of depression in middle-aged and older adults with frequent and infrequent nicotine use: A cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord.367, 554–561 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clifton, S. et al. STI Risk Perception in the British Population and How It Relates to Sexual Behaviour and STI Healthcare Use: Findings From a Cross-sectional Survey (Natsal-3). EClinicalMedicine2–3, 29–36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handing, E. P., Strobl, C., Jiao, Y., Feliciano, L. & Aichele, S. Predictors of depression among middle-aged and older men and women in Europe: A machine learning approach. Lancet Reg. Health - Eur.18, 100391 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Litwin, H. Social Networks and Self-Rated Health: A Cross-Cultural Examination Among Older Israelis. J. Aging Health18, 335–358 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao, T. J. et al. Internet-based and mobile-based cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Npj Digit. Med.6, 80 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinillos-Franco, S. & Kawachi, I. The relationship between social capital and self-rated health: A gendered analysis of 17 European countries. Soc. Sci. Med.219, 30–35 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan, M., Davis, C. G., Dubouloz, C.-J., Kessler, D. & Kubina, L.-A. Participation and Well-Being Poststroke: Evidence of Reciprocal Effects. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.95, 262–268 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye, C.-J. et al. Mendelian randomization evidence for the causal effect of mental well-being on healthy aging. Nat. Hum. Behav.8, 1798–1809 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Church, J. A., et al. Associations between biomarkers of environmental enteric dysfunction and oral rotavirus vaccine immunogenicity in rural Zimbabwean infants. eClinicalMedicine41, 101173 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arsandaux, J., Michel, G., Tournier, M., Tzourio, C. & Galéra, C. Is self-esteem associated with self-rated health among French college students? A longitudinal epidemiological study: the i-Share cohort. BMJ Open9, e024500 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zavras, D., Tsiantou, V., Pavi, E., Mylona, K. & Kyriopoulos, J. Impact of economic crisis and other demographic and socio-economic factors on self-rated health in Greece. Eur. J. Public Health23, 206–210 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cialani, C. & Mortazavi, R. The effect of objective income and perceived economic resources on self-rated health. Int. J. Equity Health19, 196 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prus, S. G. & Gee, E. Gender Differences in the Influence of Economic, Lifestyle, and Psychosocial Factors on Later-life Health. Can. J. Public Health94, 306–309 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poortinga, W. Do health behaviors mediate the association between social capital and health?. Prev. Med.43, 488–493 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inaba, Y., Wada, Y., Ichida, Y. & Nishikawa, M. Which part of community social capital is related to life satisfaction and self-rated health? A multilevel analysis based on a nationwide mail survey in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med.142, 169–182 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knöchelmann, A., Seifert, N., Günther, S., Moor, I. & Richter, M. Income and housing satisfaction and their association with self-rated health in different life stages. A fixed effects analysis using a German panel study. BMJ Open10, e034294 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao, L. et al. Determinants of Visual Impairment Among Chinese Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Risk Prediction Model Using Machine Learning Algorithms. JMIR Aging7, e59810–e59810 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng, H. Rising U.S. income inequality, gender and individual self-rated health, 1972–2004. Soc. Sci. Med.69, 1333–1342 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kopp, M., Skrabski, Á, Réthelyi, J., Kawachi, I. & Adler, N. E. Self-Rated Health, Subjective Social Status, and Middle-Aged Mortality in a Changing Society. Behav. Med.30, 65–72 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu, X., Yao, Y. & Jin, Y. Digital exclusion and functional dependence in older people: Findings from five longitudinal cohort studies. eClinicalMedicine54, 101708 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan, R. et al. Association between internet exclusion and depressive symptoms among older adults: panel data analysis of five longitudinal cohort studies. eClinicalMedicine75, 102767 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo, C.-H. et al. Race, ethnicity, community-level socioeconomic factors, and risk of COVID-19 in the United States and the United Kingdom. eClinicalMedicine38, 101029 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montorsi, C., Fusco, A., Van Kerm, P. & Bordas, S. P. A. Predicting depression in old age: Combining life course data with machine learning. Econ. Hum. Biol.52, 101331 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Dowrick, C. & Arroll, B. Psychological Treatment of Depression in Primary Care: Recent Developments. Curr. Psychiatry Rep.21, 129 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garin, N. et al. Global Multimorbidity Patterns: A Cross-Sectional, Population-Based, Multi-Country Study. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.71, 205–214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gelaye, B., Rondon, M. B., Araya, R. & Williams, M. A. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry3, 973–982 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Courtin, E., Knapp, M., Grundy, E. & Avendano-Pabon, M. Are different measures of depressive symptoms in old age comparable? An analysis of the CES-D and Euro-D scales in 13 countries. Int. J. METHODS Psychiatr. Res.24, 287–304 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akbaraly, T. N. et al. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged Adults. Diabetes Care32, 499–504 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukumori, N. et al. Association between hand-grip strength and depressive symptoms: Locomotive Syndrome and Health Outcomes in Aizu Cohort Study (LOHAS). Age Ageing44, 592–598 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehta, K. M., Yaffe, K. & Covinsky, K. E. Cognitive Impairment, Depressive Symptoms, and Functional Decline in Older People. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.50, 1045–1050 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y. et al. Digital exclusion and cognitive impairment in older people: findings from five longitudinal studies. BMC Geriatr.24, 406 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi, J. et al. National and subnational trends in cancer burden in China, 2005–20: an analysis of national mortality surveillance data. Lancet Public Health8, e943–e955 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barua, S., Islam, Md, M., Yao, X. & Murase, K. MWMOTE-Majority Weighted Minority Oversampling Technique for Imbalanced Data Set Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng.26, 405–425 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dablain, D., Krawczyk, B. & Chawla, N. V. DeepSMOTE: Fusing Deep Learning and SMOTE for Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst.34, 6390–6404 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified individual participant data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Quantitative analysis and modelling was performed in Python v3.11.7 and made use of the following packages: numpy, pandas, sklearn, imblearn,lightgbm, XGBoost, matplotlib,shap. Code will be made available upon reasonable request.