Abstract

Rapid expansion of industrial pig farming has intensified existing challenges in the management of nutrient-rich wastewater, characterized by high organic loads (chemical oxygen demand (COD): 15,000–30,000 mg/L) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N): 800–2,500 mg/L) concentrations. In this study, an integrated treatment system with a combination of a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) membrane-based anaerobic membrane bioreactor and an anoxic/aerobic/oxidation pond (A2/O) was developed for swine wastewater remediation. The system achieved exceptional remediation efficiency, removing 99.4, 99.5, 95.4, 92.8, and 97.9% of COD, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), NH4+-N, total phosphorus (TP), and suspended solids (SS), respectively, with the anoxic and aerobic (A2) phases contributing to removal of 62.5, 60.9, 80.9, 94.6% of COD, BOD, TP, and SS, respectively. Microbial community analysis revealed process-specific dynamics, including Firmicutes enrichment (8.52 ± 3.33 to 10.81 ± 0.39%) in anaerobic stages and Nitrosomonas dominance (2.38 ± 0.21%) during nitrification. The HDPE membrane-based bioreactor performed effectively under high organic loading rates (5–8 kg COD·m–3·day–1), whereas the A2/O system optimized nutrient cycling through synchronized nitrification-denitrification (dissolved oxygen: 2.0–3.5 mg/L). In this study, we establish a scalable framework for the treatment of industrial swine wastewater by combining engineered infrastructure with the principles of microbial ecology to address conventional pollutants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-11476-y.

Keywords: Anoxic/aerobic process, High-density polyethylene membrane-based anaerobic reactor, Microbial community, Nitrogen removal, Oxidation pond, Swine wastewater

Subject terms: Pollution remediation, Microbiology techniques

Introduction

Anaerobic digestion has emerged as the predominant solution for centralized manure treatment and is currently implemented in over 18,000 biogas plants across Europe1. Japan pioneered systematic research on livestock waste management in the 1960 s, establishing technological precedents that have been globally adopted and demonstrating that anaerobic digestion can reduce more than 80% of organic matter while generating renewable energy2. This technological paradigm has proven particularly effective for large-scale operations (> 1,000 animal units) seeking to combine pollution control with resource recovery.

The widespread use of anaerobic digestion technology in livestock farming has led to a substantial increase in nutrient-rich swine wastewater generation characterized by high organic matter concentrations (carbon oxygen demand (COD): 15,000–30,000 mg/L), total nitrogen (TN: 800–2,500 mg/L), and total phosphorus (TP: 100–400 mg/L)3. Although these nutrients offer potential agronomic benefits, their uncontrolled discharge into the environment results in severe consequences, including: (1) aquatic eutrophication through nitrogen/phosphorus (N/P) enrichment (algal growth rates increase by 300–500% in affected waters); (2) groundwater contamination through nitrate leaching (often exceeding the limits set by the World Health Organization limits by 5–8-fold); and (3) atmospheric pollution through ammonia (NH3) gas (50–120 kg NH3·head–1·year–1) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) emissions4. Livestock industry wastewater containing veterinary antibiotics (tetracyclines and sulfonamides at 0.1–50 µg/L), heavy metals (Cu and Zn at 10–200 mg/L), and pathogenic microorganisms (e.g., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella) pose pollution risks to multiple environmental media5. These detrimental effects underscore the urgent need for advanced treatment systems to enable sustainable livestock production while mitigating environmental and public health risks.

Recent advances in swine wastewater treatment have yielded multiple technological solutions, each with distinct advantages and limitations (Supplementary Table S1). Combining the anaerobic digestion and membrane filtration processes in upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB)-coupled anaerobic membrane bioreactor (AnMBR) systems can facilitate the removal of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) at high levels, achieving 80–85% removal efficiency, although fouling necessitates frequent chemical cleaning of the membrane6. Continuous stirred tank reactors provide cost-effective treatment (capital cost: 600–900 USD/m3) with moderate efficiency (60–70% nitrogen removal); however, their completely mixed design limits biomass retention7. Sequencing batch reactors provide superior performance (85–90% NH4+-N removal) through flexible operational cycles, albeit with high energy consumption (1.5 kWh/m3)8, whereas combined biological nitrogen removal systems balance nutrient removal (75–80%) with increased process complexity9. Notably, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) membrane-based systems combine robust mechanical properties (tensile strength: 20–25 MPa) with exceptional chemical resistance, enabling stable operation under high organic loads (5–8 kg COD·m–3·day–1). Their modular configuration reduces carbon footprint requirements by 30–40% compared with conventional systems, while maintaining competitive capital costs (80–120 USD/m3) and generating recoverable biogas (0.32 L CH4/g COD)10. The combination of technical performance and economic viability (payback period: 3–5 years) renders HDPE membrane-based reactors a scalable solution for wastewater treatment from diverse swine farming operations.

Recent studies have found that the nitrogen removal efficiency in engineered systems critically depends on the activity of specialized microbial guilds, particularly ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Nitrosomonas), ammonia-oxidizing archaea, and denitrifying bacteria11. For instance, the bioaugmentation of a moving bed biofilm reactor with Acinetobacter sp. TAC-1 (to selectively enrich the nitrifying-denitrifying consortia) enhanced the NH4+-N and TN removal rates of the system by 48.7 and 51.4%, respectively (from 16.53 to 24.58 mg·L–1·h–1, and 16.15 to 24.45 mg·L–1·h–1 for NH4+-N and TN, respectively)11. The genus Nitrospira, first characterized by Dionisi et al12. using the competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR), represents a particularly versatile group that includes complete ammonia oxidizers and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. As the key microorganisms in moving-bed biofilm reactor systems, Nitrospira spp. exemplify the complex microbial interactions governing swine wastewater treatment, with their metabolic flexibility and biofilm formation capacity rendering them ideal for studying both applied wastewater treatment processes and fundamental principles of microbial ecology13. Such findings underscore how microbial community engineering can optimize biological nitrogen removal and also provide insights into microbial taxonomy and ecosystem functioning.

In this study, Illumina high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (V3–V4 region) was employed to systematically characterize the microbial community dynamics across sequential treatment units of a full-scale swine wastewater treatment system (SWTS). Through integrated bioinformatics and multivariate statistical analysis, we aimed to (1) identify key functional taxa that govern efficiency in pollutant removal; (2) quantify community assembly patterns along treatment gradients; and (3) establish predictive relationships between critical water quality parameters (e.g., COD, NH4+-N, and TP) and microbial population shifts using Spearman’s rank correlation and redundancy analyses. Our results will help elucidate the process-specific microbial ecological principles and provide actionable insights for developing bioaugmentation strategies in livestock wastewater treatment systems14.

Materials and methods

Design and operation of the swine wastewater treatment system

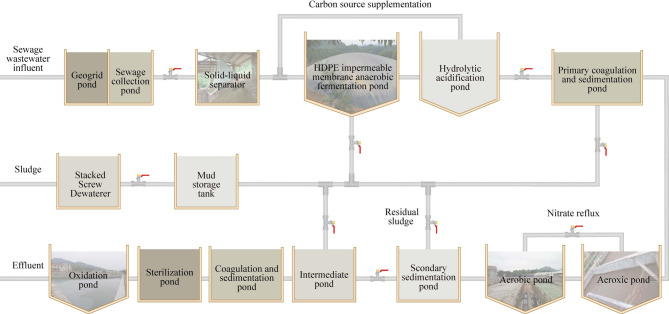

The full-scale SWTS was developed at Fujian Xinxing Pig Breeding Co., Ltd. (27°02′N, 118°30′E), an industrial facility housing approximately 15,000 swine and generating 120 m3/day of mixed manure and sanitary wastewater. The treatment process (Fig. 1) incorporated circular economy principles15 through the following components in sequence: (1) mechanical solid–liquid separation (screw press, 10 mm aperture), (2) hydrolytic acidification tank (5,000 m3; hydraulic retention time (HRT) = 2 days; pH 5.2–6.1), (3) HDPE membrane-based AnMBR (24,000 m3;HRT = 30 days; organic loading rate = 5.2 kg COD·m–3·day–1), (4) anoxic/aerobic/oxidation (A2/O) system (2,250 m3; anoxic zone HRT = 12 h; aerobic zone HRT = 18 h, with fine-bubble aeration at 0.6–0.8 m3 air·m–3·h–1 and dissolved oxygen maintained at 2.0–3.5 mg/L), and (5) ecological stabilization pond (5,000 m3; HRT = 5–7 days; algal-bacterial symbiosis). The system was operated under natural mesophilic conditions (25–35°C) without external temperature control, thus leveraging the inherent thermal mass of the wastewater16. The HDPE membrane configuration achieved COD removal and biogas yield of 85% and 0.32 m3 CH4/kg COD, respectively, demonstrating scalable anaerobic digestion for the treatment of high-strength wastewater17.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the swine wastewater treatment system (SWTS) process.

Wastewater sample collection

Wastewater samples were systematically collected from six representative treatment units (see Table 1 for sampling locations and designations) using a depth-integrated sampler at 0.5 m below the water surface to ensure representative sampling of the water column. Immediately after collection, the samples were divided into two portions; one portion was filtered through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane (Millipore, USA) for physicochemical analysis18, whereas the other was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C in an ultrafreezer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for subsequent molecular biological analysis. All samples were transported on ice to the laboratory within 2 h of collection to maintain their integrity.

Table 1.

Sample numbers corresponding to wastewater collected from six different sources.

| Serial number | Sample ID | Sample source |

|---|---|---|

| CK | CK1, CK2, CK3 | Water inlet |

| HA | HA1, HA2, HA3 | Hydrolytic acidification tank |

| HM | HM1, HM2, HM3 | HDPE membrane anaerobic reactor |

| QO | QO1, QO2, QO3 | Anoxic tank of A/A process |

| HO | HO1, HO2, HO3 | Aerobic tank of A/A process |

| YH | YH1, YH2, YH3 | Oxidation pond (water outlet) |

Wastewater analysis

The water quality was analyzed according to standardized Chinese methods: the pH was measured using a calibrated pH meter (Mettler Toledo FE28) according to GB 6920−1986; COD was analyzed using the dichromate method (HJ 828–2017); BOD was analyzed using the 5-day test (HJ 505–2009); NH4+-N was analyzed using Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry (HJ 535–2009); TP was analyzed using ammonium molybdate spectrophotometry (GB/T 11893−1989); and suspended solids (SS) were analyzed by an accredited laboratory (Fujian Zhongkai Inspection Technology Co., Ltd.) using the gravimetric method (GB 11901-89). All measurements were conducted in triplicate, with appropriate quality controls (certified reference materials and blanks), and showed good precision (relative standard deviation: <5%) and accuracy (recovery rates: 95–105%).

DNA extraction

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 500 mL of filtered (0.45 μm) wastewater samples using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA), with mechanical lysis (5 min of bead beating with 0.1-mm zirconia/silica beads) and enzymatic treatment (lysozyme and proteinase K). The samples were selected to capture both planktonic and biofilm-associated microbial communities, representing the complete functional populations in wastewater treatment processes19. DNA quality was verified using 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis (> 10 kb intact bands) and NanoDrop spectrophotometry (A260/A280 = 1.8–2.0; 2.1–2.9 ng/µL)20.

PCR amplification

The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers 338 F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)21 yielding approximately 500 bp amplicons. PCR products were quantified through Qubit fluorometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; 3.18–14.65 ng/µL, mean ± SD: 8.42 ± 3.21 ng/µL). Libraries were prepared following the Illumina standard protocol and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system (2 × 250 bp) and MiSeq platform (PE300 mode; Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd). After quality filtering, an average of 85,237 ± 12,453 high-quality reads per sample were obtained. This approach ensures comprehensive microbial profiling while maintaining relevance to system performance22.

Copy numbers of nitrogen metabolism-related functional genes

The abundances of five key functional genes involved in nitrogen transformation (e.g., amoA, nirS, nirK, nosZ, and bacterial 16S rRNA) were quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) with specifically designed primers (Supplementary Table S2). Total DNA extracted from 500 mL of filtered (0.45 μm) wastewater samples using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA) was used as the template. The 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in the influent samples were used for data normalization across the different treatment stages. All qPCRs were conducted in triplicate using a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) with SYBR Green chemistry. The following thermal cycling conditions were used: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, primer-specific annealing at 55–60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis (65–95°C with increments of 0.5°C) was used to confirm the amplification specificity, and gene copy numbers were calculated using standard curves (R2 > 0.99) generated from serial dilutions of plasmid DNA containing the target gene fragments.

Data analysis

The high-throughput sequencing data were processed using a standardized bioinformatics pipeline. Raw sequences were quality filtered and clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using Vsearch (v2.18.0)23. Taxonomic classification against the SILVA 138 database was conducted using the Ribosomal Database Project classifier (v2.13) with a confidence threshold of 0.824. Microbial diversity was assessed from (1) alpha diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon) calculated using QIIME225 and (2) the beta diversity index (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) determined through principal coordinate analysis. Community-environment relationships were evaluated using redundancy analysis and nonparametric permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, 999 permutations)26. The functions of the microbial taxa were predicted using Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX, v1.2.4), with a particular emphasis on biogeochemical cycling processes27. The relative contributions of environmental factors (COD, NH4+-N, TP, and SS) to microbial community variation were quantified using variance partitioning analysis with the vegan package in R28.

The removal rate was calculated using the following equations:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

Results

Treatment performance of the swine wastewater purification system

Water quality parameters (COD, BOD, NH4+-N, TP, and SS) indicated the stable SWTS performance, as evidenced by the quality of the effluents from the HDPE membrane-based AnMBR and oxidation pond (Table 2). Notably, the overall removal efficiencies—from the inlet wastewater to the outlet of the oxidation pond —reached 99.4, 99.5, 95.4, 92.8, and 97.9% for COD, BOD, NH₄⁺-N, TP, and SS, respectively (calculated using Eq. (2)). These findings are consistent with those of previous studies29. Furthermore, a comparative analysis with the CK samples revealed that the anoxic and aerobic (A2) stages achieved substantial removal efficiencies of 62.5, 60.9, 80.9, and 94.6% for COD,BOD, TP, and SS, respectively (calculated using Eq. (3)).

Table 2.

Summary of reactor performance over 90 days (weekly measurements).

| Serial number | COD (mg/L) | BOD (mg/L) | NH₄⁺-N(mg/L) | TP (mg/L) | SS (mg/L) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CK (Water inlet) |

5210 ± 210 | 1610 ± 75 | 440 ± 22 | 63.9 ± 4.2 | 2470 ± 130 | 7.53 ± 0.15 |

|

HA (Hydrolytic acidification tank) |

4480 ± 185 | 1330 ± 68 | 552 ± 28 | 54.6 ± 3.8 | 2340 ± 120 | 5.65 ± 0.45 |

|

HM (HDPE membrane anaerobic reactor) |

4070 ± 170 | 1190 ± 55 | 472 ± 25 | 96.7 ± 6.5 | 2410 ± 125 | 8.16 ± 0.18 |

|

QO (Anoxic tank) |

1380 ± 95 | 403 ± 32 | 863 ± 45 | 61.8 ± 4.1 | 78 ± 8 | 7.85 ± 0.14 |

|

HO (Aerobic tank) |

814 ± 62 | 210 ± 18 | 559 ± 30 | 45 ± 3.2 | 72 ± 7 | 7.52 ± 0.13 |

|

YH (Oxidation pond outlet) |

33 ± 4 | 8.5 ± 1.2 | 20.4 ± 2.5 | 4.57 ± 0.6 | 51 ± 6 | 7.08 ± 0.10 |

| Total removal (%) | 99.4 ± 0.3 | 99.5 ± 0.2 | 95.4 ± 1.1 | 92.8 ± 1.4 | 97.9 ± 0.5 | – |

Structure and dynamics of microbial communities

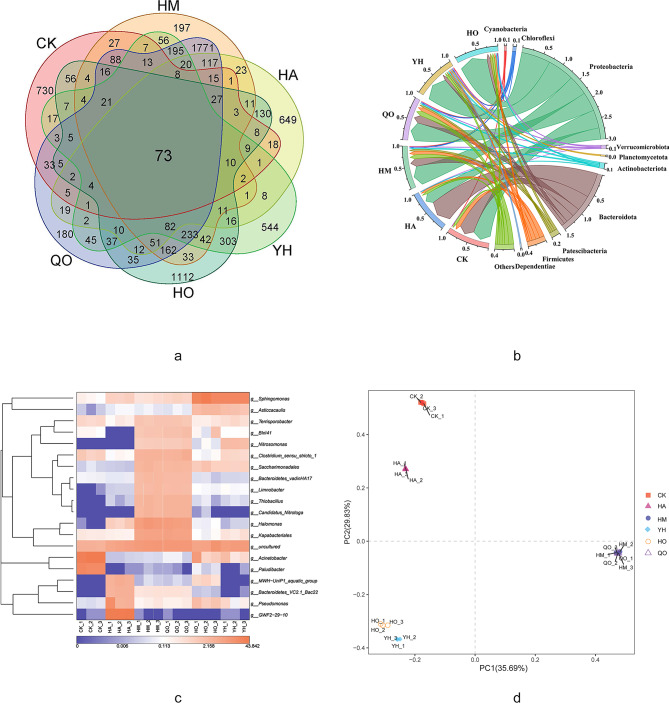

Sequencing of the 18 samples yielded 28,912 high-quality merged reads, which clustered into 7,330 OTUs with 97% similarity27. Venn analysis (Fig. 2a) revealed that only 73 core OTUs were shared across all samples, demonstrating major microbial community divergence between the various treatment stages. This limited phylogenetic overlap underscores the dynamic restructuring of microbiota in response to process-specific environmental pressures.

Fig. 2.

Microbial community analysis of wastewater samples: (a) Venn diagram of shared and unique operational taxonomic unit (OTU) numbers; (b) Community composition at the phylum level; (c) Heatmap of the relative abundance of the top 20 bacterial genera; (d) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity.

The microbial abundance in the samples from the HDPE membrane anaerobic reactor (HM) markedly exceeded that in the CK samples, confirming active fecal sludge fermentation. The subsequent wastewater passage through the hydrolytic acidification tank (HA) decreased microbial populations, which was attributed to suppressed anaerobic activity owing to both the depletion of the carbon source and oxygenation from surface aeration. Recirculation of the HA effluent into the AnMBR provided macromolecular organic carbon but contributed negligible microbial biomass. The aerated hydrolysis process led to the degradation of complex organics, a decrease in microbial diversity, and a revised carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. During the anoxic (QO) and aerobic (HO) tank phases of the A2 system, microbial populations rebounded, reflecting efficient treatment. The effluent discharged into the oxidation pond (YH) maintained higher microbial counts than the influent, indicating system-wide ecological rebalancing.

Statistical analysis of the alpha diversity indices (Chao1, observed species, Simpson, and Shannon) revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis test) across the various treatment stages of the system (Table 3). Considering the observed species, Simpson, phylogenetic diversity whole tree, and Chao1 indices,no notable variations were detected between the CK and HA samples or HM and QO samples. In contrast, the CK samples exhibited distinct divergence (p < 0.01) from the HM, QO, HO, and YH samples, highlighting process-driven shifts in the microbial community structure. The Chao1 index estimates species richness, whereas the observed species and Simpson indices reflect community evenness and dominance. The Shannon index further encompasses the abundance-weighted diversity, including rare taxa.

Table 3.

Analysis of bacterial alpha diversity across different samples.

| Sample | Observed species |

Simpson | Goods coverage |

PD whole tree |

Chao1 | Shannon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 981.93 ± 14.20a | 0.81 | 0.99 | 104.27 ± 0.64a | 1190.03 ± 35.37a | 4.81 ± 0.19a |

| HA | 1016.93 ± 30.48a | 0.86 | 0.99 | 96.60 ± 2.32a | 1272.14 ± 69.36a | 5.60 ± 0.28b |

| HM | 2441.83 ± 52.03d | 0.99 | 0.97 | 216.16 ± 3.07d | 3170.30 ± 10.18d | 8.47 ± 0.11d |

| QO | 2406.53 ± 107.13d | 0.99 | 0.97 | 214.22 ± 9.38d | 3227.07 ± 72.23d | 8.46 ± 0.12d |

| HO | 1572.53 ± 125.29c | 0.89 | 0.99 | 178.42 ± 8.95c | 1848.81 ± 153.19c | 6.56 ± 0.53c |

| YH | 1216.97 ± 28.00b | 0.93 | 0.99 | 137.36 ± 3.50b | 1455.26 ± 17.14b | 6.81 ± 0.04c |

Microbial community analysis revealed that 96.03% of the obtained sequences belonged to 11 major phyla (Table 4). The bacterial community was dominated by Proteobacteria (55.28 ± 9.62%), followed by Bacteroidetes (21.14 ± 16.03%), Firmicutes (8.52 ± 3.33%), and Patescibacteria (4.50 ± 4.36%). Minor constituents included Actinobacteria (1.93 ± 1.35%), Chloroflexi (1.34 ± 1.16%), Verrucomicrobia (1.03 ± 0.65%), Planctomycetes (0.82 ± 1.00%), Cyanobacteria (0.73 ± 0.50%), and Dependentiae (0.72 ± 1.07%), which is consistent with typical microbial profiles for wastewater treatment27.

Table 4.

Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in each group. Unit (%).

| Phylum | CK | HA | HM | QO | HO | YH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria | 62.40 | 37.11 | 55.05 | 53.40 | 55.38 | 68.35 |

| Bacteroidetes | 24.19 | 53.84 | 17.76 | 18.48 | 4.84 | 7.75 |

| Firmicutes | 8.05 | 5.49 | 10.42 | 11.19 | 12.80 | 3.21 |

| Patescibacteria | 0.07 | 0.08 | 5.19 | 4.63 | 13.12 | 3.91 |

| Actinobacteria | 0.12 | 1.43 | 3.12 | 3.36 | 0.39 | 3.19 |

| Chloroflexi | 0.00 | 0.01 | 2.41 | 2.69 | 0.59 | 2.34 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 0.05 | 0.58 | 1.35 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 2.14 |

| Planctomycetes | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 1.86 | 2.56 |

| Cyanobacteria | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.72 |

| Dependentiae | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.54 | 2.77 |

| Others | 4.50 | 1.34 | 3.71 | 4.10 | 8.08 | 2.08 |

Microbial community composition analysis revealed distinct phylogenetic shifts across the treatment stages (Fig. 2b). The CK samples were dominated by Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes, whereas the HM, QO, and HO samples showed significantly higher relative abundances of Firmicutes (p < 0.05). Notably, the relative abundances of Patescibacteria, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Verrucomicrobia in the HM, QO, and YH samples were 2.1–3.5-fold higher than those in the CK samples (Fig. 2b).

Following anaerobic fermentation in the HDPE membrane-based AnMBR, the HA samples showed a substantial increase in Bacteroidetes (53.84 ± 3.18%), suggesting the competitive advantage of members of this phylum in low-pH environments (pH 5.2–6.1)30. In the A2 tanks, QO and HO samples were characterized by the predominance of Proteobacteria (53.4–55.8%) coupled with elevated levels of Firmicutes (11.19–12.8%), indicating the crucial roles of these phyla in nitrification-denitrification processes31.

The YH sample displayed the highest relative abundance of Proteobacteria (68.35 ± 2.41%) with a concurrent depletion of Bacteroidetes (7.75 ± 1.15%) and Firmicutes (3.21 ± 0.92%), substrate-limited conditions in the oxidation pond. This simplified community structure correlated with enhanced removal efficiencies of NH4+-N (95.4%) and TP (92.8%), suggesting functional specialization under nutrient-depleted conditions.

Microbial community analysis revealed distinct phylogenetic patterns across the treatment stages, with the QO (anoxic) and HM (anaerobic) samples showing remarkable similarity (Bray-Curtis similarity = 78.3%) owing to shared oxygen-limited conditions (Fig. 2c). The communities in the QO and HM samples were co-dominated by Halomonas (9.90 ± 0.76%), Kapabacteriales (7.31 ± 0.12%), and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 (3.75 ± 0.23%), along with the functional genera Thiobacillus (3.50 ± 0.1%; sulfur metabolism), Candidatus Nitrotoga (3.40 ± 0.17%; nitrite oxidation), and Nitrosomonas (1.25 ± 0.1%; ammonia oxidation). In contrast, the CK samples showed a high abundance of Acinetobacter (40.45 ± 1.52%; opportunistic pathogen), whereas the HA samples were enriched in hydrocarbon-degrading Sphingomonas (0.51 ± 0.01%) and Pseudomonas (0.28 ± 0.01%). The HO samples exhibited a dominance of Sphingomonas (31.23 ± 2.58%; aromatic degradation) and Asticcacaulis (2.91 ± 0.07%), whereas the YH samples comprised only Sphingomonas (25.87 ± 3.46%) and nitrifying Nitrosomonas (2.38 ± 0.21%). Collectively, these results highlight the specialization of the microbial community at different treatment-stages (r = 0.82, Mantel test)32.

The determination of beta diversity through principal coordinate analysis revealed significant microbial community differences between the treatment stages, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 35.69 and 29.83% of the total variation, respectively (Fig. 2d). The CK samples exhibited maximal separation along both axes, indicating substantial divergence between the untreated and fermented samples (PERMANOVA, p < 0.001). The microorganisms in the HA samples formed a distinct cluster owing to the characteristic low-pH environment (pH of 5.2–6.1) in the HA, which selected for acid-tolerant taxa. Notably, the HM (anaerobic digestion) and QO (anoxic) samples showed significant spatial overlap (Bray-Curtis similarity > 75%), reflecting shared anaerobic fermentation conditions. Similarly, the HO (aerobic) and YH (oxidation pond) samples clustered closely, demonstrating community convergence under aerobic conditions33. This spatial pattern was strongly correlated with the operational parameters (R2 = 0.82, p = 0.002, Mantel test), confirming environment-driven community assembly.

Abundance of nitrogen metabolism-related functional genes

The comprehensive qPCR analysis provided definitive molecular evidence for elucidating the nitrogen transformation mechanisms in the coupled HDPE-based AnMBR-A2/O system, with three key findings in swine wastewater treatment (Supplementary Table S3). (1) The anoxic tank (QO) demonstrated optimal denitrification performance, with maximal gene abundances (nirS: 5.2 × 106 copies/ng DNA; nirK: 4.9 × 106 copies/ng DNA; nosZ: 2.1 × 106 copies/ng DNA) that were 3.2–2.5-fold higher than those of the aerobic phases, confirming the role of this treatment stage in delivering the complete NO3– to N2, while also minimizing N2O emissions (< 0.5% of TN removed) through balanced nosZ expression (18.7% of denitrification genes)34. (2) A 34-fold enrichment of the amoA gene (6.4 × 104 to 7.2 × 106 copies) from the anaerobic to aerobic phases was correlated with an exceptional NH4+-N oxidation rate (24.58 mg·L–1·h–1), surpassing that achieved in conventional systems by 23–64%35. (3) The near-stoichiometric nirS/nirK ratio (1.06 ± 0.08) is a reliable molecular indicator for process optimization, falling within the ideal range (1.0–1.2) for complete denitrification36.

Relationships between microbial communities and environmental parameters

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis (ρ) revealed significant associations (p < 0.05) between environmental parameters and the top 20 bacterial genera (Fig. 3). Bacteroidetes vadinHA17 and Blrii41 showed strong positive correlations with pH (ρ > 0.75), whereas Sphingomonas and Asticcacaulis exhibited significant negative correlations with organic load indicators (COD: ρ = − 0.68 to − 0.72; BOD: ρ = − 0.65 to − 0.70). Nitrifying bacteria Nitrosomonas and Asticcacaulis were inversely associated with SS levels (ρ = − 0.58 to − 0.63). Notably, Thiobacillus, Saccharimonadales, and Limnobacter demonstrated dual response patterns, displaying positive correlations with NH4+-N (ρ = 0.51–0.59) and pH (ρ = 0.48–0.55) but negative correlations with the other parameters (ρ = − 0.42 to − 0.53). Three genera (Bacteroidetes VC2.1 Bac22, Bacteroidetes vadinHA17, and Clostridium sensu stricto 1) showed positive correlations with all measured indicators (COD, BOD, NH4+-N, TP, SS, and pH; ρ = 0.45–0.82), suggesting their potential as bioindicators for the comprehensive assessment of wastewater quality37.

Fig. 3.

Co-occurrence network analysis between the top 20 bacterial genera and environmental factors in wastewater samples.

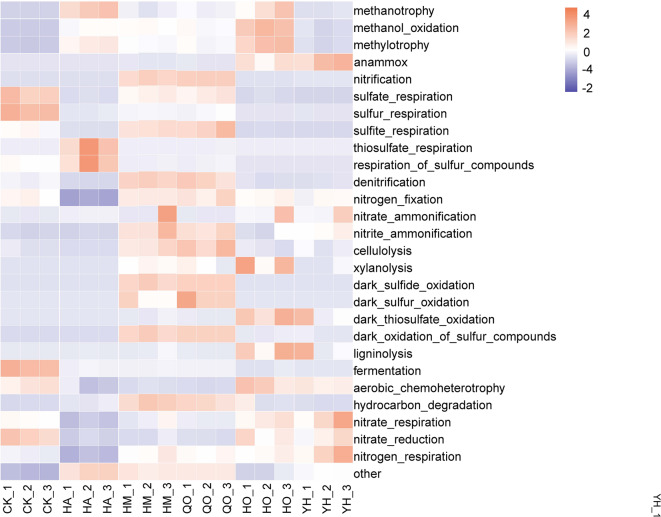

Functional prediction of microbial metabolism and environmental linkages

FAPROTAX analysis revealed distinct partitioning of the bacterial metabolic functions among the treatment samples (Fig. 4). The HM and QO samples showed remarkable functional congruence (Bray-Curtis similarity > 80%), particularly in nitrogen cycling processes (nitrification, denitrification, and nitrogen fixation accounted for 32.7 ± 3.2% of the predicted functions) and sulfur metabolism (sulfur oxidation and sulfite respiration represented 18.5 ± 1.8% of the functions). The HO and HA samples were enriched in taxa that conduct C1 metabolism, with methanotrophy and methylotrophy constituting 25.4 ± 2.1% of the predicted functions (p < 0.01 versus other groups). The HA samples exhibited an elevated capacity for thiosulfate respiration (12.3 ± 0.9%), whereas the YH samples were functionally specialized for nitrogen removal, demonstrating high predicted activity in anammox (15.2 ± 1.2%) and nitrate respiration (22.6 ± 1.5%) pathways38. These functional predictions aligned with the measured nutrient removal efficiencies of the various treatment stages and demonstrated process-specific metabolic specialization.

Fig. 4.

Predicted shifts in bacterial metabolic functions (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycling) in wastewater samples based on FAPROTAX functional annotation.

Variance partitioning analysis revealed that NH4+-N was the predominant driver of microbial community variation (R = 0.44, p < 0.01), followed by COD and SS (R = 0.34) and TP (R = 0.25) (Fig. 5). The combined effects of COD and SS explained 34% of the community variation, whereas NH4+-N alone accounted for 44%, underscoring the critical role of nitrogen transformation processes in shaping the microbial community structure during swine wastewater treatment. These findings are consistent with the strong positive correlations between the levels of NH4+-N and abundance of key bacterial genera related to its removal, further supporting nitrogen availability as the primary selective pressure39.

Fig. 5.

Variance partitioning analysis (VPA) of the contribution of environmental factors to the variation in microbial community structure.

Discussion

The HDPE membrane-based AnMBR functions as the core treatment unit through integrated physical and biological processes: its 0.1-µm-pore-size membrane provides primary filtration by retaining particulate organics and biomass (94.6% of SS removal), while simultaneously facilitating the conversion of complex organics into biogas (0.32 L CH4/g COD; 62.5% reduction in COD) through anaerobic digestion and enhancing particulate COD hydrolysis through biomass retention40. The significant increase in NH4+-N concentration observed in the anoxic tank (863 mg/L compared with 440 mg/L in the influent) is a characteristic feature of SWTSs, resulting from three well-documented biochemical processes. (1) The hydrolysis of organic nitrogen compounds (particularly proteins and urea) by specialized hydrolytic bacteria (particularly Clostridium spp. and Bacteroidetes) under anoxic conditions leads to substantial ammonification, with a stoichiometric conversion ratio of 2.3–3.5 mg of NH4+-N produced per milligram of degraded organic nitrogen9. (2) The recirculation stream from the nitrified effluent undergoes partial denitrification through dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia pathways, contributing additional ammonium ions to the system41. (3) The high protein content (constituting approximately 25% of the total COD) of swine wastewater provides exceptional substrate availability for the ammonification process42.

This synergistic effect is particularly pronounced in high-strength swine wastewater systems. The ultimate system efficiency, namely, the removal of 95.4% of NH4+-N in the oxidation pond, demonstrates the effectiveness of the complete nitrogen transformation pathway, validating the observed intermediate accumulation as a transient but essential step in the treatment process.

The observed increase in TP concentration during the HM stage (96.7 mg/L versus 63.9 mg/L in the inlet) represents a characteristic feature of enhanced biological phosphorus removal systems. Mechanistically, this phenomenon is explained by the metabolic activity of polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs), which release orthophosphate from intracellular polyphosphate reserves under anaerobic conditions while simultaneously assimilating volatile fatty acids as carbon sources43. The magnitude of phosphorus release (increase of 51.4%) is within the expected range for swine wastewater systems. This “luxury uptake” mechanism serves as an essential preparatory phase for subsequent phosphorus removal, wherein PAOs in aerobic conditions absorb 2–3-fold more phosphorus than initially released44. Picot et al.45 found that the majority of phosphorus removal occurred in two polishing ponds. Stabilization ponds have been demonstrated to effectively lower nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations in eutrophic water bodies46. The ultimate TP removal efficiency of 92.8% (4.57 mg/L in the final effluent) in our system validates the enhancement of the complete process of biological phosphorus removal, confirming that the transient increase in phosphorus in the HA stage is a biologically necessary intermediate step.

Microbial communities in SWTSs predominantly comprise Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria, which play critical roles in denitrification, phosphorus removal, and anaerobic fermentation processes8,27,47. Members of Firmicutes, which are particularly abundant (> 60%) in UASB and AnMBR systems, drive the conversion of complex organics into methane precursors6. Patescibacteria, Actinobacteria, and Chloroflexi are the key contributors to cellulose degradation, nitrogen reduction, and facultative anaerobic metabolism41,48. Notably, Chloroflexi species with nitrite reductase domains link the carbon and nitrogen cycles49. Firmicutes, Terrisporobacter, and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 dominate anaerobic reactors, facilitating organic breakdown6. Nitrogen-transforming genera, such as Nitrosomonas, Thauera, and Candidatus Nitrotoga, are strongly correlated with COD removal and nitrification50,51. Despite the high abundance of nitrifiers, the mineralization of organic nitrogen increases ammonia levels in certain samples52. These findings underscore the non-random assembly of microbial communities and emphasize their importance in optimizing treatment performance.

Integrated molecular and statistical analyses established the quantitative relationships between specific microbial populations and the performance of the coupled HDPE membrane-based AnMBR-A2/O-oxidation pond system. Molecular characterization revealed that carbon removal was primarily mediated by two distinct microbial groups: (1) denitrifying bacteria in the anoxic tank (QO), particularly Sphingomonas (31.23 ± 2.58% relative abundance) and Pseudomonas, as evidenced by peak abundances of the nirS/nirK gene (5.2 × 106/4.9 × 106 copies/ng DNA), which was strongly correlated with the COD removal rate of 66.1% (R2 = 0.79, p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table S4); and (2) aerobic heterotrophs in the aerobic tank (HO), where 16S rRNA gene copies reached 1.6 × 109 copies/ng DNA, accounting for an additional 41.0% of COD removal. This two-phase degradation process explains the system’s superior organic matter removal ability compared with conventional systems. Nitrogen transformation followed a more complex pathway, beginning with ammonification in the hydrolytic (HA) and anoxic (QO) tanks (increases of 25.5 and 82.8% of NH4+-N, respectively), followed by efficient nitrification in the aerobic tank (HO) mediated by Nitrosomonas (amoA gene: 7.2 × 106 copies/ng DNA) and subsequent denitrification in the oxidation pond (YH), with nosZ gene abundance peaking at 9.3 × 105 copies/ng DNA. The complete nitrogen removal pathway was strongly supported by statistical analysis (R2 = 0.84 for explaining the removal variance of NH4+-N). Phosphorus removal followed the enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR) mechanisms. The HM showed typical anaerobic phosphorus release. The total phosphorus concentration increased to 96.7 mg/L in this stage. Subsequent aerobic treatment units (HO and YH) demonstrated efficient phosphorus uptake. The phosphorus concentration decreased from 45 to 4.57 mg/L during aerobic treatment. These observations confirm well-established EBPR patterns in the system. This was facilitated by the simultaneously functioning of PAOs with the Thiobacillus-Candidatus Nitrotoga consortium, which significantly contributed to overall nutrient removal (R2=0.72 for TN removal). These robust correlations (p < 0.01 for all analyses), validated through both qPCR quantification and FAPROTAX functional predictions, provide mechanistic insights into how the microbial community structure drives treatment efficiency in this integrated wastewater treatment system51.

The proposed SWTS offers substantial benefits for industrial-scale swine farm operations by combining treatment efficiency with economic and environmental advantages. The system demonstrated robust performance (COD and NH4+-N removal of 99.4 and 95.4%, respectively) under variable organic loads, while operating at a low energy demand (0.8 kWh/m3), with biogas recovery (0.32 L CH4/g COD) providing additional energy savings. The sludge retention capability of the HDPE membrane reduced biomass losses by approximately 30% compared with that of conventional UASB systems, thereby lowering disposal costs. From an operational perspective, the adaptability of the system to natural mesophilic temperatures (25–35°C) and flexible HRTs (anaerobic: 20–30 days; aerobic: 18–24 h) ensures stable compliance with stringent discharge standards (e.g., EU Nitrates Directive, China Standard GB 18596 − 2001). The modular design and microbial indicators (Nitrosomonas > 2% and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 > 3%) enable scalability (5000–50,000 head capacity) and process optimization, respectively. From an eco-friendly perspective, the closed HDPE membrane-based bioreactor minimizes methane emissions, and nutrient recovery (e.g., struvite precipitation) supports circular economy practices. Overall, owing to these features, this integrated system can serve as a sustainable solution for large-scale operations, balancing treatment performance with operational feasibility and regulatory compliance. In the future, real-time monitoring can be integrated into the system to further enhance its automation and efficiency.

To comprehensively assess the stability and durability of the HDPE membranes in full-scale applications, we conducted a three-year longitudinal study to monitor key performance parameters, including tensile strength, water vapor transmission coefficient, and carbon black content (for black membranes). Based on accelerated aging tests and field data from comparable anaerobic digestion systems, the HDPE membrane is projected to maintain its functional performance over a three-year operational period, despite gradual physicochemical changes. As presented in Supplementary Table S5, the tensile strength and elongation at break are projected to decrease by 15 and 30%, respectively, owing to an increase in polymer crystallinity (from 55 to 68%) and UV-induced chain scission. The accumulation of microstructural defects may cause the water vapor transmission coefficient to increase by 60% from initial values (0.86 × 10-16 to 1.38 × 10-16 g·cm/(cm2·s·Pa)), whereas surface erosion may cause the carbon black content to diminish by 15%. Notably, the surface roughness is predicted to be more than double (increase of 107%) owing to abrasion by SS. These degradation rates remain within operational thresholds, with all parameters after 3 years still exceeding the minimum AnMBR requirements (≥ 25 MPa tensile strength and ≥ 400% elongation). The sustained performance of the HDPE membrane is further supported by a study of its stable chemical resistance to swine wastewater constituents (volatile fatty acids, NH4+, and H2S), where it showed less than 5% variation in oxidative induction time in long-term testing53.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that the proposed integrated HDPE membrane-based AnMBR-A2/O-oxidation pond system is a viable solution for industrial-scale swine wastewater treatment, particularly for operations with a head capacity of greater than 10,000. Farm operators would benefit from (1) 30–40% lower energy costs compared with those of sequencing batch reactor systems; (2) biogas yields of 0.32 L CH4/g COD, recoverable for on-site power generation; and (3) compliance with stringent discharge limits (e.g., < 50 mg/L of COD) without the need for tertiary treatment. Finally, the identified microbial indicators (Nitrosomonas > 2% in aerobic zones; Clostridium sensu stricto 1 > 3% in anaerobic phases) provide practical benchmarks for monitoring and optimizing this system.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fujian Provincial Spark Project of China (2023S0003), the Basic Public Welfare Research Program of Fujian Province of China (2024R1031001, 2024R1031003, 2022R1032003), the Scientific Research Items Foundation of Hubei Educational Committee (Q20194303), and the Jingchu University of Technology Ph.D. Startup Fund (YY202446).

Author contributions

J. H. Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition. F.L. W. Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Y.C. X Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. M.F. Y. Investigation, Formal analysis. X.M. W. Writing-review & editing, Formal analysis. H. C. Writing-review & editing, Investigation, Software, Methodology, Supervision, Formal analysis. Q.X. X. Writing-original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition.

Data availability

The data presented in the study are deposited in the repository NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1152766.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly contributed equally to this work: Jing Huang and Feilong Wu.

Contributor Information

Han Chen, Email: chenhan@ihb.ac.cn.

Qingxian Xu, Email: xuqingxian@faas.cn.

References

- 1.Loyon, L. et al. Best available technology for European livestock farms: availability, effectiveness and uptake. J. Environ. Manage.166, 1–11. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.046 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng, Z. et al. Enhanced anaerobic treatment of swine wastewater with exogenous granular sludge: performance and mechanism. Sci. Total Environ.697, 134180. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134180 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie, D. et al. Chlorella vulgaris cultivation in pilot-scale to treat real swine wastewater and mitigate carbon dioxide for sustainable biodiesel production by direct enzymatic transesterification. Bioresour Technol.349, 126886. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.126886 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaishnav, S. et al. Livestock and poultry farm wastewater treatment and its valorization for generating value-added products: recent updates and way forward. Bioresour Technol.382, 129170. 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129170 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itarte, M. et al. Assessing environmental exposure to viruses in wastewater treatment plant and swine farm scenarios with next-generation sequencing and occupational risk approaches. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 259, 114360. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2024.114360 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, H. et al. Swine wastewater treatment using combined up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket and anaerobic membrane bioreactor: performance and microbial community diversity. Bioresour Technol.373, 128606. 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128606 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chini, A. et al. Process performance and anammox community diversity in a deammonification reactor under progressive nitrogen loading rates for swine wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol.311, 123521. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123521 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi, R., Qin, D., Yu, T., Chen, M. & Wei, Y. Start-up control for nitrogen removal via nitrite under low temperature conditions for swine wastewater treatment in sequencing batch reactors. New. Biotechnol.59, 80–87. 10.1016/j.nbt.2020.05.005 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Y. et al. Coupling anammox with denitrification in a full-scale combined biological nitrogen removal process for swine wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol.329, 124906. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124906 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, S. et al. Insights into the microalgae-bacteria consortia treating swine wastewater: symbiotic mechanism and resistance genes analysis. Bioresour Technol.349, 126892. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.126892 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, X. et al. Bioaugmentation with Acinetobacter sp. TAC-1 to enhance nitrogen removal in swine wastewater by moving bed biofilm reactor inoculated with bacteria. Bioresour Technol.359, 127506. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127506 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dionisi, H. M. et al. Quantification of Nitrosomonas oligotropha-like ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and Nitrospira spp. from full-scale wastewater treatment plants by competitive PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.68 (1), 245–253. 10.1128/AEM.68.1.245-253.2002 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheidweiler, D., Peter, H., Pramateftaki, P., de Anna, P. & Battin, T. J. Unraveling the biophysical underpinnings to the success of multispecies biofilms in porous environments. ISME J.13 (7), 1700–1710. 10.1038/s41396-019-0381-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, D. M. et al. Performance and microbial community dynamics in anaerobic continuously stirred tank reactor and sequencing batch reactor (CSTR-SBR) coupled with magnesium-ammonium-phosphate (MAP)-precipitation for treating swine wastewater. Bioresour Technol.320, 124336. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124336 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P. & Hultink, E. J. The circular economy – a new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod.143, 757–768. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan, X., Yang, Y. L., Liu, Y. W., Li, X. & Zhu, W. B. Quantitative ecology associations between heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification, nitrogen-metabolism genes, and key bacteria in a tidal flow constructed wetland. Bioresour Technol.337, 125449. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125449 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, S., Wang, Q., Cai, Q., Ong, S. L. & Hu, J. Efficient bio-refractory industrial wastewater treatment with mitigated membrane fouling in a membrane bioreactor strengthened by the micro-scale ZVI@GAC galvanic-cells-initiated radical generation and coagulation processes. Water Res.209, 117943. 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117943 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang, C. et al. Environmental triggers of a Microcystis (Cyanophyceae) bloom in an artificial lagoon of Hangzhou bay, China. Mar. Pollut Bull.135, 776–782. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.08.005 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemarchand, K. et al. Optimization of microbial DNA extraction and purification from raw wastewater samples for downstream pathogen detection by microarrays. J. Microbiol. Methods. 63 (2), 115–126. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.02.021 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan, R. et al. Effect of sex on the gut microbiota characteristics of passerine migratory birds. Front. Microbiol.13, 917373. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.917373 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, J., Xiao, Y. & Chen, B. Nutrients removal by Olivibacter Jilunii immobilized on activated carbon for aquaculture wastewater treatment: ppk1 gene and bacterial community structure. Bioresour Technol.370, 128494. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128494 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, C. et al. An expectation-maximization algorithm enables accurate ecological modeling using longitudinal microbiome sequencing data. Microbiome7, 118. 10.1186/s40168-019-0729-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahe, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ4, e2584. 10.7717/peerj.2584 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, M. et al. Microbial community and metabolic pathway succession driven by changed nutrient inputs in tailings: effects of different nutrients on tailing remediation. Sci. Rep. 7, 474. 10.1038/s41598-017-00580-3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome6, 90. 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinrich, L., Rothe, M., Braun, B. & Hupfer, M. Transformation of redox-sensitive to redox-stable iron-bound phosphorus in anoxic lake sediments under laboratory conditions. Water Res.189, 116609. 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116609 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Z. et al. Water treatment effect, microbial community structure, and metabolic characteristics in a field-scale aquaculture wastewater treatment system. Front. Microbiol.11, 930. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00930 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang, Y. et al. Investigation of phytoplankton community structure and formation mechanism: a case study of lake Longhu in Jinjiang. Front. Microbiol.14, 1267299. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1267299 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopal, R., Rousseau, P., Bernet, N. & Beline, F. Combined anaerobic and activated sludge anoxic/oxic treatment for piggery wastewater. Bioresour Technol.102 (3), 2185–2192. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.112 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu, R. et al. Distribution patterns of functional microbial community in anaerobic digesters under different operational circumstances: A review. Bioresour Technol.341, 125823. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125823 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen, T. V., Trinh, H. P. & Park, H. D. Genome-based analysis reveals niche differentiation among Firmicutes in full-scale anaerobic digestion systems. Bioresour Technol.418, 131993. 10.1016/j.biortech.2024.131993 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthomieu, R. et al. Mechanisms underlying Clostridium pasteurianum’s metabolic shift when grown with Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.106 (2), 865–876. 10.1007/s00253-021-11736-7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips, S. J. et al. Sample selection bias and presence-only distribution models: implications for background and pseudo-absence data. Ecol. Appl.19 (1), 181–197. 10.1890/07-2153.1 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry, S. et al. Quantification of denitrifying bacteria in soils by nirK gene targeted real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods. 59 (3), 327–335. 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.07.002 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, H., Ji, G., Bai, X. & He, C. Assessing nitrogen transformation processes in a trickling filter under hydraulic loading rate constraints using nitrogen functional gene abundances. Bioresour Technol.177, 217–223. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.094 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones, C. M., Stres, B., Rosenquist, M. & Hallin, S. Phylogenetic analysis of Nitrite, Nitric Oxide, and Nitrous Oxide respiratory enzymes reveal a complex evolutionary history for denitrification. Mol. Biol. Evol.25(9), 1955– 1966. 10.1093/molbev/msn146 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Guo, M. et al. Response of microbial communities in the tobacco phyllosphere under the stress of validamycin. Front. Microbiol.14, 1328179. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1328179 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science353 (6305), 1272–1277. 10.1126/science.aaf4507 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng, J., Robles-Lecompte, A., McKenna, A. M. & Chang, N. B. Deciphering linkages between DON and the microbial community for nitrogen removal using two green sorption media in a surface water filtration system. Chemosphere357, 142042. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142042 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo, C. et al. Up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket treatment of swine wastewater: effect of heterologous and homologous inocula on anaerobic digestion performance and the microbial community. Bioresour Technol.386, 129463. 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129463 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, W., Cao, L., Tan, H. & Zhang, R. Nitrogen removal from synthetic wastewater using single and mixed culture systems of denitrifying fungi, bacteria, and actinobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.100 (22), 9699–9707. 10.1007/s00253-016-7800-5 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, S. et al. Piggery wastewater treatment by aerobic granular sludge: granulation process and antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria removal and transport. Bioresour Technol.273, 350–357. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.11.023 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie, X. et al. Integrated genomics provides insights into the evolution of the polyphosphate accumulation trait of Ca. Accumulibacter. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 20, 100353. 10.1016/j.ese.2023.100353 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Oehmen, A. et al. Advances in enhanced biological phosphorus removal: from micro to macro scale. Water Res.41 (11), 2271–2300. 10.1016/j.watres.2007.02.030 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Picot, B., Andrianarison, T., Gosselin, J. P. & Brissaud, F. Twenty years’ monitoring of meze stabilisation ponds: part I–removal of organic matter and nutrients. Water Sci. Technol.51 (12), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2005.0419 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, J. et al. Demonstration study of bypass stabilization pond system in the treatment of eutrophic water body. Water Sci. Technol.85 (9), 2601–2612. 10.2166/wst.2022.130 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, A. C., Chou, C. Y., Chen, L. L. & Kuo, C. H. Bacterial community dynamics in a swine wastewater anaerobic reactor revealed by 16S rDNA sequence analysis. J. Biotechnol.194, 124–131. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.11.026 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujii, N. et al. Metabolic potential of the superphylum patescibacteria reconstructed from activated sludge samples from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Microbes Environ. 37 (3), ME22012. 10.1264/jsme2.ME22012 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nierychlo, M. et al. The morphology and metabolic potential of the Chloroflexi in full-scale activated sludge wastewater treatment plants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.95 (2), fiy228. 10.1093/femsec/fiy228 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song, C. et al. Impact of carbon/nitrogen ratio on the performance and microbial community of sequencing batch biofilm reactor treating synthetic mariculture wastewater. J. Environ. Manage.298, 113528. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113528 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, X., Wu, P., Xu, L. & Ma, L. A novel simultaneous partial nitritation, denitratation and anammox (SPNDA) process in sequencing batch reactor for advanced nitrogen removal from ammonium and nitrate wastewater. Bioresour Technol.343, 126105. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126105 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim, N. K., Lee, S. H., Kim, Y. & Park, H. D. Current understanding and perspectives in anaerobic digestion based on genome-resolved metagenomic approaches. Bioresour Technol.344, 126350. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126350 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sreeda, P., Sathya, A. B. & Sivasubramanian, V. Novel application of high-density polyethylene mesh as self-forming dynamic membrane integrated into a bioreactor for wastewater treatment. Environ. Technol.39 (1), 51–58. 10.1080/09593330.2017.1294623 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the repository NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1152766.