Abstract

This study presents an Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled Deep Learning Monitoring (IoT-E-DLM) model for real-time Athletic Performance (AP) tracking and feedback in collegiate sports. The proposed work integrates advanced wearable sensor technologies with a hybrid neural network combining Temporal Convolutional Networks, Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (TCN + BiLSTM) + Attention mechanisms. It is designed to overcome key challenges in processing heterogeneous, high-frequency sensor data and delivering low-latency, sport-specific feedback. The system deployed edge computing for real-time local processing and cloud setup for high-complexity analytics, achieving a balance between responsiveness and accuracy. Extensive research was tested with 147 student-athletes across numerous sports, including track and field, basketball, soccer, and swimming, over 12 months at Shangqiu University. The proposed model achieved a prediction accuracy of 93.45% with an average processing latency of 12.34 ms, outperforming conventional and state-of-the-art approaches. The system also demonstrated efficient resource usage (CPU: 68.34%, GPU: 72.56%), high data capture reliability (98.37%), and precise temporal synchronization. These results confirm the model’s effectiveness in enabling real-time performance monitoring and feedback delivery, establishing a robust groundwork for future developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven sports analytics.

Keywords: Internet of things, Edge computing, Deep learning, Athletic performance monitoring, Long short-term memory, Accuracy, Sports

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Environmental social sciences, Engineering

Introduction

The exponential development in wearable sensor technologies and Internet of Things (IoT) devices has transformed the monitoring of Athletic Performance (AP), generating unprecedented volumes of real-time data across diverse sports disciplines1,2. In collegiate athletics, where performance optimization and injury prevention are critical, traditional monitoring methods frequently fail to provide timely, actionable insights3. Although manual observation and periodic tests are the standard methods, these methods lack the precision and immediacy required for effective training adaptation and performance enhancement4,5.

When dealing with data collected by athletic training, real-time monitoring still recollects numerous significant deficiencies:

-

i.

The heterogeneous features of multi-sensor data streams make current methods unsuitable for integrating all different data modalities; instead, each is treated individually6,7.

-

ii.

Traditional analysis methods fail to manage the temporal complexity of AP, which, in nature, is intrinsic to high-intensity activities.

-

iii.

Data processing and analysis delays render the feedback less applicable to real-time Decision-Making Systems (DMS).

-

iv.

Most current systems are not flexible enough to cover different sports disciplines with consistent AP8–10.

These limitations motivate proposed research to develop an integrated solution that effectively addresses these challenges.

The motivation for this originates from three key observations:

The increasing availability of high-fidelity sensor data in collegiate sports;

Edge computing capability advancements that can support real-time processing;

The emergence of modern Deep Learning (DL) capable of managing complex temporal data.

With increasing demand from collegiate sports for real-time, exact AP metrics, innovative solutions that efficiently process and analyze multi-modal sensor data become even more required.

The main challenge addressed in this research is twofold: first, the lack of a unified system capable of fusing heterogeneous, multi-modal sensor streams in real-time athletic environments; and second, the limitations of existing learning models in extracting multi-scale temporal patterns and context-aware features from such complex data. Existing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), or Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) -based models either process short-range dependencies or lack directional and interpretive depth. To this end, we propose a hybrid Temporal Convolutional Network, Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (TCN + BiLSTM) + Attention mechanism that jointly captures fine-grained temporal dependencies and dynamically emphasizes critical features to improve performance prediction accuracy and responsiveness.

While prior studies have applied Reinforcement Learning (RL) for policy optimization and CNN for spatial pattern recognition in athletic monitoring, these methods frequently face critical limitations. RL-based systems typically lack transparency and require significant exploration time, making them less suitable for real-time applications. CNN-based models, though effective for static activity recognition, challenge to capture long-range temporal dependencies intrinsic to athletic motion dynamics. Moreover, many existing systems are either narrowly tailored to specific sports or lack integration between edge processing and cloud analytics. In contrast, the proposed model introduces a hybrid Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled Deep Learning Monitoring (IoT-E-DLM) model that integrates multi-scale TCN, bidirectional BiLSTM, and a feature-focused Attention mechanism. This design enables accurate, interpretable, and low-latency performance monitoring across diverse sports scenarios, presents generalizability and real-time feedback capability — key strengths that distinguish this model from previous efforts.

Development of a scalable IoT model that effectively manages heterogeneous, high-frequency multi-modal sensor data through the integration of edge computing for real-time responsiveness and cloud computing for complex analytics.

Design of a hybrid Deep Learning (DL) model combining Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), and an Attention mechanism, which jointly overcomes the limitations of existing CNN + RL by capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies, bidirectional context, and interpretable feature relevance.

Implementation of a robust and adaptive preprocessing pipeline that ensures synchronization, data integrity, and efficient Feature Extraction (FE) from diverse sensor streams, enabling generalization across multiple sports.

Extensive validation across four distinct sports disciplines (Track and Field, Basketball, Soccer, and Swimming) using real-world data from 147 collegiate athletes, demonstrating superior predictive performance and cross-domain applicability.

This recommended model’s experimental results demonstrate significant improvements over existing methods, achieving 93.45% accuracy in AP prediction with an average processing latency of 12.34 ms. The system has been successfully deployed across multiple sports facilities, demonstrating its practical applicability and scalability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents a comprehensive review of related work in IoT-based AP monitoring and DL applications. Section 3 details the system and the proposed hybrid DL. Section 4 describes the implementation features. Section 5 presents the Experimental setup, evaluation results, and comparative analysis. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the paper with insights into future research directions.

Literature review

The integration of IoT + DL has significantly advanced real-time AP monitoring. Recent studies have explored numerous methods to enhance sports data collection, processing, and feedback mechanisms.

Below is a review of ten notable works in this domain:

Tang et al.11 addressed the limitations of traditional monitoring systems by proposing an IoT-optimized approach that combines edge computing with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). Their system utilizes a Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) optimized within the IoT to achieve efficient motion recognition and real-time feedback. Experimental results demonstrated significant improvements in response time, data processing accuracy, and energy efficiency, particularly in complex track and field events.

Sidik et al.12 explored the application of IoT in sports performance analysis, focusing on real-time data processing and intelligent systems. They discussed the integration of wearable sensors and data analytics to provide athletes and coaches with immediate insights into improving training effectiveness while reducing injury risks. The study also highlighted challenges related to data security and the requirement for strong real-time processing capabilities.

Raman et al.13 discuss the transformative effect of IoT in sports and fitness, focusing on wearables, sensors, and data analytics for collecting and analyzing real-time data. Such integration of technologies supports athletes and coaches in enhancing training methods, reducing injuries, and optimizing performance.

On the other hand, Chao et al.14 investigated the application of RL using IoT devices to establish the optimal coaching policy in basketball. They aimed to improve player movement and health by fusing IoT health sensors with Deep Q-Networks (DQN). The model achieved 95% accuracy in predicting optimal moves, thereby reducing the risk of injury by up to 60%. This resulted in a considerable improvement in the performance and efficiency of the players.

To monitor and analyze the behavior of sports trainers15, have developed an IoT-based system combined with Deep Neural Networks (DNN). Their system processes data collected from multiple sensors to provide insights into training methods and effectiveness, thereby improving the quality of sports training through advanced data analysis.

Li et al.16 discussed designing an IoT-assisted model for physical education focusing on network virtualization and monitoring.

The system attempts to improve efficiency and effectiveness in physical education training by using IoT technologies to monitor and measure real-time performance parameters. Schulthess et al.17 have presented ‘Skilog,’ a compact, energy-efficient Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) for real-time performance analysis and biofeedback during ski jumping. The system measures foot pressures at multiple points and provides real-time feedback to athletes using an optimized XGBoost that has achieved 92.7% of the center of mass prediction accuracy.

Johnson et al.18 proposed a method to predict ground reaction forces and moments using wearable sensor accelerations and a CNN. Their method affords predictions close to real-time, enabling on-field assessment without the requirement of laboratory-based equipment, thus increasing the ecological validity of athlete monitoring. The study19 used DL to predict on-field 3-D knee joint moments in athletes to create an early warning system for athlete workload exposure and knee injury risk. Their work showed the possibility of DL for on-field injury assessment, closing the gap between lab-based analyses and real-world applications.

Jha et al.20 discussed the application of video analytics in elite soccer, presenting real-time video analytics algorithms and the requirement for distributed computing. Their work highlights the role of video data in performance evaluation and the need for efficient computing resources to process large datasets in real-time.

While the reviewed studies demonstrate notable progress in IoT-based athletic monitoring—ranging from RL for coaching policy optimization11–14, CNN-based biomechanical analysis18,19, to smart sensor integration for real-time feedback12–17—they also reveal persistent gaps. Many models either focus on narrow sport-specific use cases or rely on learning networks that lack robust temporal modelling capabilities across modalities. RL systems frequently experience high computational costs and suffer from poor interpretability, making them less practical for real-time feedback in dynamic environments. CNNs are limited in capturing long-range temporal dependencies inherent to athletic movements, while several DNN + IoT lack generalizability across varied physical activities. Furthermore, few systems effectively leverage edge-cloud synergy for balancing real-time responsiveness with high-volume computation.

These limitations collectively motivate the development of the proposed IoT-E-DLM model. By integrating Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) for multi-scale temporal extraction, Bidirectional LSTMs (BiLSTMs) for contextual learning, and an Attention mechanism for relevance-aware prediction, the model proposals enhanced temporal sensitivity and interpretability. Coupled with an edge-cloud model and validated across four distinct sports, the proposed solution addresses the limitations of prior methods and advances the field of real-time Athletic Performance (AP) monitoring.

Proposed methodology

The proposed IoT-E-DLM model is designed as a comprehensive system that enables real-time monitoring and feedback of AP by a securely integrated combination of sensing hardware, communication setup, and DL algorithms. At its core, the system leverages a layered network composed of distributed IoT sensors, edge computing units, and cloud-based analytics, all working in unison to acquire, transmit, process, and interpret multi-modal performance data. The methodological proposal incorporates advanced neural modelling techniques for extracting meaningful temporal patterns from complex time-series inputs, alongside system-level mechanisms for efficient data handling and responsive feedback delivery. The following sections describe each component of the proposed methodology in detail, including system architecture, sensor integration, communication protocols, cloud infrastructure, and the DL model that drives performance prediction and analysis.

System architecture

The proposed IoT-E-DLM for AP monitoring has four layers that work harmoniously to deliver real-time insights and feedback. Figure 1 shows the overall proposed model, integrating advanced sensing technologies, edge computing, cloud analytics, and specialized feedback mechanisms tailored for collegiate sports. The architecture of the proposed model starts with the athlete community, which involves a type of sporting activity and its corresponding performance metrics. This layer is a heterogeneous mix of wearable sensors judiciously selected for the different disciplines in sports. The WSN includes motion tracking sensors to capture biomechanical parameters, physiological sensors to monitor vital signs and biometrics, and environmental sensors to measure ambient conditions. Sports-specific sensors are also integrated into equipment to capture specialized metrics relevant to AP. Together, these sensors provide all the data collection required for training sessions and competitive events.

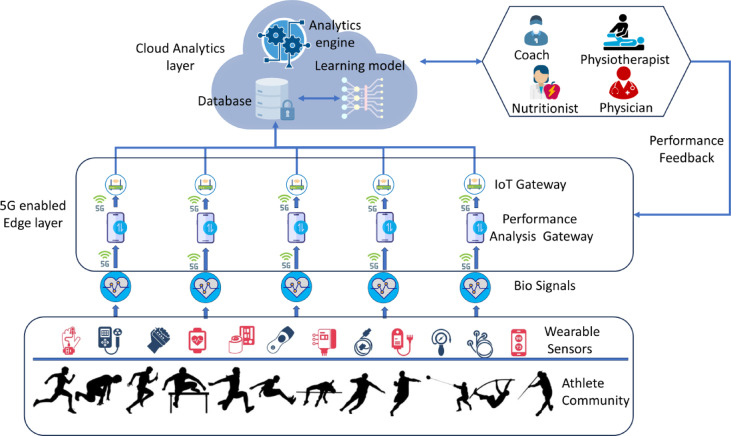

Fig. 1.

Proposed IoT-E-DLM.

The EC layer uses 5G technology for minimum data transmission and processing latency. Hence, multiple IoT gateways are spread over the training facilities and complemented with a Performance Analysis Gateway for preliminary data processing and filtering. This edge layer aggregates and analyzes data in real time, allowing the possibility of edge-based caching for immediate feedback capabilities. The application of 5G provides high-bandwidth, low-latency communication required for real-time AP monitoring and feedback delivery. The cloud analytics layer is the cognitive center of the system and houses the core computation and analytical elements. Long-term storage is handled by a highly secure database that enables historical analysis of each AP. On top of this layer, advanced learning models predict AP and identify patterns in different athletic parameters. The analytics engine transforms complex performance metrics, while the integrated visualization and reporting modules convert raw data into actionable, predictable insights. This layer is designed with a focus on scalability and security to provide reliable AP analysis for multiple teams and athletic programs.

The model concludes with a comprehensive feedback system that connects several AP ecosystem stakeholders through a sophisticated mobile application interface. The customized mobile application, serving as the primary user interface, provides real-time access to the system’s performance metrics, analytics, and feedback mechanisms. This enables coaches to view the real-time results of their planned training regulations and physiotherapists to access biomechanical data for injury prevention. Nutritionists use metabolic and performance data to optimize dietary recommendations, while team physicians monitor health parameters in order to oversee medical management. The mobile platform allows role-based access control, meaning stakeholders see only information relevant to their responsibilities, and it assures data privacy and security. This application provides interactive dashboards that propose real-time monitoring, historical trend analysis, and immediate communication among team members. This integrated mobile-first method ensures all parties involved can have instant, secure access to information relevant to their specific role in athlete development and performance optimization, no matter where they may be.

Components

The functionality of the proposed IoT-E-DLM model relies on a coordinated ensemble of interconnected components that operate across sensing, transmission, and computation layers. These components include an assortment of wearable and equipment-integrated IoT sensors for capturing biomechanical, physiological, and environmental data; wireless communication protocols to ensure timely and secure data transfer; and a robust cloud setup to support high-throughput analytics and storage. Each element plays a critical role in ensuring real-time monitoring, low-latency feedback, and system scalability. The following section presents a detailed account of these system components, their configurations, and their integration within the broader monitoring model.

IoT sensors

The new system utilizes an array of IoT sensors specifically selected to capture all the various features of AP. Grouping is based on their measurement domains, and these groups are combined to provide a holistic view of AP metrics.

The core of motion analysis is Inertial Measurement Units (IMU), each containing tri-axial accelerometers (± 16 g), gyroscopes (± 2000°/s), and magnetometers. The latter are used in sampling frequencies of up to 1000 Hz, allowing accurate tracking of very fast AP. The accelerometers will measure linear acceleration on three axes, while the gyroscopes will measure angular velocity, which is significant when analyzing rotational movements, such as gymnastics and diving. Magnetometers provide a precise location reference by measuring magnetic field strength, critical for maintaining accurate motion tracking, particularly during prolonged training sessions.

The physiological monitoring system has optical heart rate sensors, which achieve a 100 Hz sampling rate for real-time cardiovascular monitoring with an accuracy of ± 1 BPM. The sensors here are based on photoplethysmography (PPG) and use dual-wavelength LED configurations (green 525 nm, infrared 940 nm) to ensure accurate readings across numerous skin tones and motion artifacts. Additionally, electrical conductance differs with Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) sensors at 50 Hz to track athlete stress and exertion.

In spatial tracking, the system uses dual-frequency Global Positioning System (GPS) modules in the L1/L2 bands with integrated Real-time Kinematic Positioning (RTK) positioning to achieve centimetre-level accuracy at 10 Hz update rates. Ultra-wideband (UWB) ranging sensors operating in the 6.5–8 GHz frequency band are added to enhance indoor positioning in complicated training environments.

Force measurement. Force measurements use load cells and pressure sensors on training equipment and surfaces. The load cells have a 0–2000 N measurement range with 0.1% full-scale accuracy, while the pressure mapping arrays make distributed force measurements at 100 Hz with 1 kPa resolution. The sensors are most important in analyzing weight training and jump performance.

Data acquisition from these sensors is hierarchical. At the lowest level, sensor-specific microcontrollers deal with raw data acquisition and preliminary filtering. Each sensor node has a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M4F processor operating at 120 MHz, incorporating digital signal processing. Signal conditioning includes anti-aliasing filters at the hardware level and digital Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters implemented in real time. Preliminary processing using embedded algorithms—optimized for resource-constrained environments—is applied to the filtered data.

The system has a strong synchronization protocol using Precision Time Protocol (PTP) with sub-microsecond accuracy to ensure the temporal alignment of the data streams from multiple sensors. The data packets are structured according to a custom protocol that embeds timestamps, sensor IDs, and Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) for error detection. The packet structure optimizes bandwidth usage while preserving data integrity; typical packet sizes run from 20 to 64 bytes, depending on the sensor type.

The power management is integrated with a combination of energy-harvesting technologies and rechargeable lithium-polymer batteries within the sensors. Advanced power management algorithms dynamically control sampling rates and transmission intervals based on sensed activity levels to achieve up to 12 h of operation under typical usage conditions.

The sensor data is first checked at the stage of acquisition itself, where range checking, trend analysis, and consistency verification are performed. If any abnormal readings are recorded, it flags them for further analysis, but the original data is always retained for possible post-processing. This multi-level data acquisition method ensures robust and reliable performance monitoring while optimizing system resources and Energy Consumption (EC). Table 1 presents details of the sensors used in this work.

Table 1.

Technical specifications of IoT sensors used in the AP monitoring System.

| Sensor | Parameters Measured | Specifications | Sampling Rate | Resolution/Accuracy | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMU | Linear Acceleration | ± 16 g range | 1000 Hz | 16-bit (0.002 g) | Motion Analysis, Impact Forces |

| Angular Velocity | ± 2000°/s | 1000 Hz | 16-bit (0.07°/s) | Rotational Movement | |

| Magnetic Field | ± 4900 µT | 100 Hz | 14-bit (0.6 µT) | Orientation Tracking | |

| Heart Rate Monitor | Pulse Rate | 30–240 BPM | 100 Hz | ± 1 BPM | Cardiovascular Load |

| Blood Oxygen | 70–100% SpO2 | 1 Hz | ± 2% | Oxygen Utilization | |

| GPS Module | Position | L1/L2 bands | 10 Hz | ± 1 cm (RTK mode) | Spatial Tracking |

| Velocity | 0–500 km/h | 10 Hz | ± 0.05 m/s | Speed Analysis | |

| Force Sensors | Ground Reaction Force | 0–2000 N | 1000 Hz | ± 0.1% F.S. | Impact Analysis |

| Pressure Distribution | 0-1000 kPa | 100 Hz | 1 kPa | Weight Distribution | |

| GSR Sensor | Skin Conductance | 0.1–100 µS | 50 Hz | 0.01 µS | Stress Monitoring |

| UWB Beacon | Indoor Position | 6.5–8 GHz | 200 Hz | ± 10 cm | Indoor Tracking |

Communication protocols

The multi-layered communication model employs numerous wireless technologies to ensure good data transmission from sensors to the cloud infrastructure. The architecture is designed to minimize power consumption while maintaining low latency and high reliability in dynamic sports environments.

The primary short-range communication protocol at the sensor level is Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE 5.2), operating in the 2.4 GHz ISM band. BLE uses connection-oriented channels. Adaptive Frequency Hopping (AFH) with 40 channels, 2 MHz spacing, provides good interference resilience in high-interference RF environments. The protocol operates a modified Connection Interval (CI) from 7.5 ms to 4 seconds, which is dynamically adjusted based on data priority and sensor type. Critical motion sensors have shorter CIs of 7.5–20 ms, while physiological monitors can operate at much longer intervals of 100–1000 ms to optimize power consumption.

The system’s communication is based on Wi-Fi 6 (IEEE 802.11ax) for medium-range communication, operating on the 2.4 and 5 GHz bands. Implementation is based on Wi-Fi 6’s Target Wake Time (TWT) feature, which allows for scheduling exact communication windows to reduce power consumption and channel contention. Multi-user MIMO (MU-MIMO) enables simultaneous data streams from multiple sensors, achieving an aggregate throughput of up to 1.2 Gbps within the training facility.

The integration of the 5G network operates on both Sub-6 GHz (FR1) and mmWave (FR2) bands, based on 3 GPP Release 16 specifications. The system uses network slicing to create virtual networks dedicated to different types of data: Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication (URLLC) slice for critical real-time data (latency < 1 ms) and enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) slice for high-throughput sensor data streams. The Physical Layer uses adaptive modulation and coding schemes, selecting dynamically between Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (QPSK), 16- Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM), and 64-QAM, depending on the channel conditions. Data integrity is ensured through Forward Error Correction using Low-Density Parity Check (LDPC) codes with coding rates from 1/2 to 7/8.

The Data Link Layer (DLL) implements an irregular Automatic Repeat reQuest (ARQ) protocol optimized for real-time sports applications. The implemented protocol utilizes a dynamically adjusted sliding window mechanism with window sizes ranging from 4 to 64 packets, depending on the channel quality indicators. Channel utilization efficiency, in terms of frame aggregation techniques, merges multiple sensor readings into a single transmission unit.

The Transport Layer combines Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)/User Datagram Protocol (UDP) with a hybrid method: the time-critical data uses UDP, and the non-real-time data uses TCP with modified congestion control algorithms tuned for wireless environments. System Quality of Service (QoS) is provided by a practice QoS model having four levels of priorities:

Priority 0: Critical motion and impact data (Latency < 5 ms).

Priority 1: Real-time physiological data (Latency < 20 ms).

Priority 2: Position and tracking data (Latency < 50 ms).

Priority 3: Environmental and contextual data (Latency < 100 ms).

These latency thresholds are based on the real-time demands of various sensor classes and are supported by prior literature. The < 5 ms requirement (Priority 0) for high-frequency motion sensors aligns with biomechanical systems designed for real-time force feedback17,18. The < 20 ms range (Priority 1) matches physiological monitoring delays seen in fatigue and exertion tracking11,21. Tracking sensors in team sports operate effectively under < 50 ms (Priority 2) thresholds20,22, and ambient condition measurements can tolerate up to < 100 ms latency (Priority 3)10,23.

Table 2 provides a detailed overview of each protocol layer’s communication parameters and performance metrics.

Table 2.

Communication protocol parameters and performance Specifications.

| Protocol Layer | Technology | Operating Parameters | Performance Metrics | Power Consumption | Security Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Range (PAN) | BLE 5.2 | Frequency: 2.4 GHz | Range: 50 m | Active: 3.5 mA | 128-bit AES |

| Channels: 40 (2 MHz) | Latency: 3–6 ms | Sleep: 1 µA | Pairing Authentication | ||

| TX Power: 0 to + 8 dBm | Throughput: 2 Mbps | ECDH Key Exchange | |||

| Medium-Range (LAN) | Wi-Fi 6 | 2.4/5 GHz Dual-Band | Range: 100 m | Active: 120 mA | WPA3 Enterprise |

| Channel Width: 20/40/80 MHz | Latency: 5–10 ms | Sleep: 5µA | 256-bit Encryption | ||

| MU-MIMO 8 × 8 | Throughput: 1.2 Gbps | PMK Caching | |||

| Wide-Range (WAN) | 5G NR | FR1: Sub-6 GHz | Range: 500 m | Active: 250 mA | 3GPP Security |

| FR2: 24–40 GHz | Latency: <1 ms | Sleep: 10 µA | Network Slicing | ||

| Bandwidth: 100 MHz | Throughput: 10 Gbps | IMSI Protection | |||

| Data Link Layer | Custom | Window Size: 4–64 packets | Frame Loss: <0.1% | Processing: 15 mA | CRC-32 |

| Frame Size: 128–1500 B | Retransmission Rate: <5% | Frame Encryption | |||

| Transport Layer | TCP/UDP | Buffer Size: 64 KB | Jitter: <2 ms | Processing: 10 mA | TLS 1.3 |

| Hybrid | Window Scale: 1–14 | Packet Loss: <0.01% | Certificate-based |

Cloud infrastructure

The AP monitoring system is deployed on top of the Google Cloud Platform using a distributed cloud model, as shown in Fig. 2. It contains three essential layers: data ingestion, processing, and storage; each is tailored to suit the specific needs of real-time AP monitoring. In the ingestion layer, the architectural design is based on stream-based architecture through a publisher-subscriber model24. The system resolves the buffering issue by processing an incoming sensor data stream and handling bursts efficiently during intensive training periods. The implementation provides a sustained event throughput of 1 M per second with a dynamic buffer, adjusting the size to varying data rates from concurrent training sessions.

Fig. 2.

Cloud Model.

The processing layer is designed with two paths: real-time and analytical processing. The real-time processing pipeline, developed using Apache Beam running on Cloud Dataflow, ensures that processing latencies are maintained below 100 ms. This is achieved using a sophisticated windowing operation using a 10-second window. Sliding windows with 2 s. Triggers to provide constant metrics updates. DL inference capabilities are combined with advanced statistical analysis via BigQuery Machine Learning (ML) on the analytical processing path. The Artificial Intelligence (AI) Platform deployment leverages Tesla T4 GPUs to attain inference times consistently below 20 ms, while complex time-series analysis is managed with BigQuery ML using custom SQL extensions.

The storage infrastructure is based on a multi-tier method with three main components. First comes Cloud Spanner as a real-time database, which runs in a configuration with 3–15 nodes, each having 4vCPU and 32 GB memory; this provides latencies of less than 10 ms for reads and less than 15 ms for writes while providing an ability of 100,000 operations per second with automatic sharding. Long-term data storage is based on Cloud Storage, present petabyte-scale capacity, multi-region replication, and automated lifecycle management across storage tiers25. BigQuery provides data warehouse functionality, which handles complex analytical queries across historical performance data.

Scaling management is fetched with the help of Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaling by applying a predictive scaling mechanism relying on ML trained on past usage patterns; this way, proactive resource allocation can be tested most appropriately at times of competition and high-intensity training26. The set-up promises 99.99% availability thanks to comprehensive reliability mechanisms, including regional failover systems with automated Domain Name System (DNS) updates and consistent hashing for load distribution. Circuit breakers stop cascade failures; regular snapshot backups ensure data persistence and recovery capabilities.

Proposed TCN + BiLSTM + attention mechanism for AP prediction

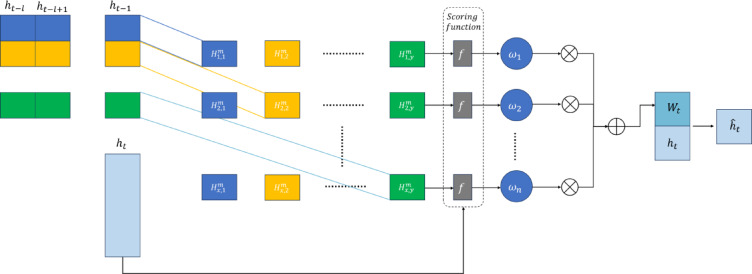

The proposed model (Fig. 3) combines the strengths of Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks, and an Attention mechanism to analyze time-series data generated by IoT sensors. In this hybrid architecture, the main challenge is related to the complexity of multi-dimensional, sequential data that requires capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies and contextual relationships with attention to the most critical features for prediction. This section introduces the architecture with formal definitions of its components, including parameters and notations. The input to the model is denoted as X, a matrix of size T×D, where T is the number of time steps in the sequence, and D is the number of input features. Features are physiological, biomechanical, and environmental metrics captured by IoT sensors, including accelerometers, heart rate monitors, and GPS devices. The pre-processed data is input into the model for uniformity and temporal alignment.

Fig. 3.

Proposed Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) + Attention Mechanism.

The first part of the model is the TCN, which processes the input data to extract temporal features at multiple scales. In order to preserve the time ordering of the input sequence, the TCN uses fundamental and expanded convolution operations while exponentially increasing the size of the receptive field. The kernel size ‘k’ controls the temporal window of the convolution filters; different values, such as  ,

, are used in parallel layers to capture short- and long-term patterns. This is because the dilation factor ‘d’, controlling spacing between elements in the convolution operation, allows dependencies from numerous temporal ranges to be captured without increasing the computational complexity. Each of the TCN layers generates feature maps

are used in parallel layers to capture short- and long-term patterns. This is because the dilation factor ‘d’, controlling spacing between elements in the convolution operation, allows dependencies from numerous temporal ranges to be captured without increasing the computational complexity. Each of the TCN layers generates feature maps  , where

, where  denotes the number of filters in the lth layer. All outputs of parallel layers are concatenated to develop a unified feature as

denotes the number of filters in the lth layer. All outputs of parallel layers are concatenated to develop a unified feature as  . Its dimension is

. Its dimension is , where

, where  denotes the total number of feature maps that are concatenated from the layers.

denotes the total number of feature maps that are concatenated from the layers.

The output from the Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) is input into the Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), which processes the data in a forward and backward temporal direction to extract bidirectional dependencies. Each unit in Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory contains forward and backward LSTM layers that produce hidden states for each time step in a sequence. The forward hidden state at time step  , denoted

, denoted  , depends on inputs from time steps 1 through

, depends on inputs from time steps 1 through  , while the backward hidden state depends on inputs from time steps 'T' through 't'. These hidden states are concatenated to form a comprehensive representation,

, while the backward hidden state depends on inputs from time steps 'T' through 't'. These hidden states are concatenated to form a comprehensive representation,  , which has dimensions

, which has dimensions  , where 'H' is the dimensionality of the hidden states in each LSTM direction. This bidirectional processing allows for learning temporal relations spanning past and future contexts, which is critical for capturing trends and anomalies in the AP data27.

, where 'H' is the dimensionality of the hidden states in each LSTM direction. This bidirectional processing allows for learning temporal relations spanning past and future contexts, which is critical for capturing trends and anomalies in the AP data27.

An Attention mechanism is applied to the output of BiLSTM to make the model more interpretable and practical. The Attention mechanism computes a set of weights, ' ', for each time step 't', which quantifies the importance of that time step in making the final prediction. These weights are derived using a trainable scoring function that assesses the importance of the features at each time step. The Attention mechanism generates a weighted feature representation,

', for each time step 't', which quantifies the importance of that time step in making the final prediction. These weights are derived using a trainable scoring function that assesses the importance of the features at each time step. The Attention mechanism generates a weighted feature representation,  , by summing up the output of BiLSTM concerning these weights. This would allow the model to emphasize the most critical segments of the sequence and concentrate on the most informative patterns, such as unpredicted changes in motion or physiological parameters indicative of fatigue or injury.

, by summing up the output of BiLSTM concerning these weights. This would allow the model to emphasize the most critical segments of the sequence and concentrate on the most informative patterns, such as unpredicted changes in motion or physiological parameters indicative of fatigue or injury.

The attention-weighted features are then passed through a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer that down-samples the temporal dimension by averaging the features across all time steps (Fig. 4). Thus, the resultant vector  , is a fixed-size representation of the sequence, where the dimensions are related to the number of features retained after pooling. Dropout regularization is applied to

, is a fixed-size representation of the sequence, where the dimensions are related to the number of features retained after pooling. Dropout regularization is applied to  , to prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating a fraction of the neurons during training. The finally processed features, therefore, are passed through the fully connected output layer, parameterized by a weight matrix

, to prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating a fraction of the neurons during training. The finally processed features, therefore, are passed through the fully connected output layer, parameterized by a weight matrix  and a bias term

and a bias term  . Depending on the predictions’requirements, the output layer uses either a SoftMax activation function for classification tasks or a linear activation function for regression tasks.

. Depending on the predictions’requirements, the output layer uses either a SoftMax activation function for classification tasks or a linear activation function for regression tasks.

Fig. 4.

TCN Network Model.

Table 3 provides the notations used in this study:

Table 3.

Notations with description.

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

|

Input time-series matrix with  time steps and time steps and  sensor features sensor features |

|

Number of time steps in each input sequence |

| D | Number of input features (e.g., sensor channels) |

|

Kernel size used in temporal convolutions |

|

Dilation factor in dilated convolutions |

|

Number of convolutional filters in the  -th TCN branch -th TCN branch |

|

Total number of TCN output feature maps (sum across all branches) |

|

Output feature representation from the TCN module |

|

Output from BiLSTM containing forward and backward contextual features |

| H | Hidden dimension of LSTM in each direction |

|

Forward and backward hidden states at time 't' |

|

Concatenated BiLSTM hidden state at time 't' |

|

Attention alignment score at time step 't' |

|

Normalized attention weight at time step 't' |

|

Context vector computed as the attention-weighted sum of hidden states |

|

Concatenated attention and hidden feature at time step 't' |

|

Final attention-enhanced hidden representation at time 't' |

|

Attention-refined sequence of hidden representations |

|

Output vector after Global Average Pooling (GAP) |

|

Mean squared error loss for prediction accuracy. |

|

Loss for encouraging temporal consistency across outputs |

|

Attention supervision loss for pattern alignment |

|

Total composite loss function |

|

Weighting coefficients for loss terms (satisfying   ) ) |

Temporal convolutional network (TCN) module

-

A.

The Temporal Convolutional Network Module (TCN): Fig. 4 illustrates the TCN module, a component of the proposed model tasked with extracting temporal dependencies and features from multi-dimensional time-series data. TCNs use causal and dilated convolutions to handle sequential data and ensure temporal causality with exponentially growing receptive fields. The TCN will assume input

and generate its representation

and generate its representation  serving as input for the following layers.

serving as input for the following layers. -

B.

Input and Output

The input to the TCN is the time-series data  , where:

, where:

is the number of time steps.

is the number of time steps. is the number of features.

is the number of features.

The output of the TCN is a transformed representation  , where

, where  is the total number of feature maps generated by the module. Causal convolution ensures that the output at time step

is the total number of feature maps generated by the module. Causal convolution ensures that the output at time step  depends only on the current and past inputs, preserving the temporal causality of the data. For a 1D input sequence

depends only on the current and past inputs, preserving the temporal causality of the data. For a 1D input sequence  with length

with length  , the output of a causal convolution at time

, the output of a causal convolution at time  is given by, EQU (1)

is given by, EQU (1)

|

1 |

Where,

is the kernel size.

is the kernel size. is the

is the  -th filter coefficient.

-th filter coefficient.The index

enumerates the filter taps from the most recent (

enumerates the filter taps from the most recent ( ) to the oldest (

) to the oldest ( ), and it does not represent a time variable.

), and it does not represent a time variable.Instead, it defines the relative offset within the convolution window applied at each time step

.

.

-

C.

Dilated Convolution.

Dilated convolution expands the receptive field of the network without increasing the number of parameters, allowing the model to capture long-term dependencies efficiently.

For a dilation factor, the dilated convolution at time  is defined as, EQU (2)

is defined as, EQU (2)

|

2 |

Where:

is the dilation factor, which determines the spacing between consecutive elements of the input,

is the dilation factor, which determines the spacing between consecutive elements of the input, is the kernel size,

is the kernel size, and

and  are as defined earlier.

are as defined earlier.

When  , the dilated convolution reduces to a standard convolution. As

, the dilated convolution reduces to a standard convolution. As  increases exponentially across layers, the receptive field grows proportionally, enabling the model to capture both short-term and long-term temporal dependencies.

increases exponentially across layers, the receptive field grows proportionally, enabling the model to capture both short-term and long-term temporal dependencies.

-

D.

Parallel Convolutional Layers

To capture multi-scale temporal features, the TCN includes parallel convolutional layers with varying kernel sizes  (e.g.,

(e.g.,  ). Let

). Let  represent the output of the

represent the output of the  -th convolutional layer.

-th convolutional layer.

The transformation for the  -th layer is expressed as, EQU (3)

-th layer is expressed as, EQU (3)

|

3 |

Where:

is the output of the

is the output of the  -th layer at time

-th layer at time  ,

, is a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU),

is a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU), is the

is the  -th filter coefficient for the

-th filter coefficient for the  -th layer,

-th layer, is the bias term for the

is the bias term for the  -th layer,

-th layer, is the number of filters in the

is the number of filters in the  -th layer.

-th layer.

The outputs of the parallel layers are concatenated along the feature dimension to produce the final representation, EQU (4)

|

4 |

Where,

is the number of parallel convolutional layers.

is the number of parallel convolutional layers.

To maintain the temporal length of the output  equal to the input length, zero-padding is applied at the beginning of the sequence. The sum of padding depends on the kernel size

equal to the input length, zero-padding is applied at the beginning of the sequence. The sum of padding depends on the kernel size  and dilation factor

and dilation factor  , ensuring that the output aligns temporally with the input. Residual connections are incorporated to stabilize training and help gradient flow in deeper networks.

, ensuring that the output aligns temporally with the input. Residual connections are incorporated to stabilize training and help gradient flow in deeper networks.

For each layer  , the residual connection adds the input

, the residual connection adds the input  to the output

to the output  , EQU (5).

, EQU (5).

|

5 |

Where,

is the final output of the

is the final output of the  -th layer with residual connections.

-th layer with residual connections.

Bidirectional long Short-Term memory (BiLSTM)

The Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) (Fig. 5) is designed to process the temporally rich representation generated by the TCN and capture bidirectional dependencies in the time-series data. While the TCN excels at capturing multi-scale temporal patterns, the BiLSTM complements it by modelling sequential data in forward and backward directions, thereby enhancing the contextual understanding of the data. This section formally describes the BiLSTM and its mathematical formulation.

Fig. 5.

BiLSTM Model.

The input to the BiLSTM (Fig. 6) is the output of the TCN, denoted as  , where

, where  is the number of time steps and

is the number of time steps and  is the number of feature maps from the TCN module. The output of the BiLSTM is a contextualized representation

is the number of feature maps from the TCN module. The output of the BiLSTM is a contextualized representation  , where

, where  is the dimensionality of the hidden state in each direction (Forward and Backward). This output captures past and future dependencies for every step.

is the dimensionality of the hidden state in each direction (Forward and Backward). This output captures past and future dependencies for every step.

Fig. 6.

Attention mechanism.

The BiLSTM consists of two LSTMs:

A forward LSTM, which processes the input sequence from the first to the last time step (

to

to  ).

).A backward LSTM, which processes the input sequence in reverse, from the last to the first time step

to 1

to 1 .

.

For each time step  , the forward and backward hidden states are concatenated to produce the final hidden state.

, the forward and backward hidden states are concatenated to produce the final hidden state.  .

.

The forward LSTM computes the hidden state  at time

at time  based on the current input

based on the current input  and the previous hidden state

and the previous hidden state  , EQU (6)

, EQU (6)

|

6 |

Where:

is the cell state at time

is the cell state at time  in the forward LSTM,

in the forward LSTM, is the forward LSTM function.

is the forward LSTM function.

Similarly, the backward LSTM computes the hidden state  at time

at time  based on the current input

based on the current input  and the next hidden state

and the next hidden state  , EQU (7)

, EQU (7)

|

7 |

Where:

is the cell state at time

is the cell state at time  in the backward LSTM,

in the backward LSTM, It is the backward LSTM function.

It is the backward LSTM function.

Hidden state concatenation

The forward and backward hidden states are concatenated to produce the final hidden representation  for each time step, EQU (8).

for each time step, EQU (8).

|

8 |

Output representation

The output of the BiLSTM module,  , is a matrix containing the concatenated hidden states for all time steps, EQU (9).

, is a matrix containing the concatenated hidden states for all time steps, EQU (9).

|

9 |

In the BiLSTM, each LSTM unit still retains its gating mechanisms, which control data flow into or out of the network. The gates include the Forget Gate (FG), Input Gate (IG), and Output Gate (OG), which work in cooperation with each other to control the cell state  and hidden state

and hidden state  at each time step.

at each time step.

Forget Gate (FG): The FG determines which portion of the preceding cell state,

, to remember or to forget, EQU (10).

, to remember or to forget, EQU (10).

|

10 |

-

2

Input Gate (IG): The IG decides which new data is added to the cell state, EQU (11) and EQU (12).

|

11 |

|

12 |

-

3

Cell State Update: Update cell state by adding the retained data from the FG to the new information from the input gate, EQU (13).

|

13 |

-

4

Output Gate: The OG determines whether the state of the cell is visible at the current time step, EQU (14).

|

14 |

-

E

Hidden State: The hidden state is computed as, EQU (15)

|

15 |

In these equations:

,

,  are the learnable weight matrices and biases,

are the learnable weight matrices and biases, denotes the sigmoid activation function,

denotes the sigmoid activation function, is the element-wise multiplication,

is the element-wise multiplication, is the input at time step

is the input at time step  ,

, ,

,  are the hidden and cell states from the previous time step.

are the hidden and cell states from the previous time step.

Attention mechanism

The attention mechanism is an essential component of the proposed model, enabling the model to dynamically focus on the most relevant features and time steps within the BiLSTM output. The attention mechanism prioritizes critical temporal features by assigning adaptive weights to different sequence components, enhancing interpretability and predictive accuracy. The input to the attention mechanism is the sequence of hidden states generated by the BiLSTM, denoted as  , where

, where  represents the hidden state at time step

represents the hidden state at time step  , and

, and  is the dimensionality of the hidden states. To capture local temporal features,

is the dimensionality of the hidden states. To capture local temporal features,  as 1-D convolutional filters, each with a length

as 1-D convolutional filters, each with a length  , are applied to the hidden state sequence. This convolutional transformation generates a feature matrix

, are applied to the hidden state sequence. This convolutional transformation generates a feature matrix  , where

, where  is the reduced temporal dimension, and

is the reduced temporal dimension, and  is the number of convolutional filters.

is the number of convolutional filters.

The operation can be formally written as EQU (16).

|

16 |

Where,

is the learnable parameter of the convolutional filters.

is the learnable parameter of the convolutional filters.

To quantify the relevance of each row  in

in  concerning the current BiLSTM hidden state

concerning the current BiLSTM hidden state  , a scoring function

, a scoring function  is used. This function computes alignment scores

is used. This function computes alignment scores  , which reflects the importance of the local feature

, which reflects the importance of the local feature  to the prediction at time

to the prediction at time  . The scoring function is defined as EQU (17)

. The scoring function is defined as EQU (17)

|

17 |

Where:

: A trainable vector projecting the compatibility score into a scalar.

: A trainable vector projecting the compatibility score into a scalar. : A weight matrix transforming the convolutional features

: A weight matrix transforming the convolutional features  .

. : A weight matrix transforming the hidden state

: A weight matrix transforming the hidden state  .

. : A trainable bias vector.

: A trainable bias vector. A hyperbolic tangent activation function.

A hyperbolic tangent activation function.

The alignment scores  are normalized using the SoftMax function to produce attention weights

are normalized using the SoftMax function to produce attention weights  , EQU (18).

, EQU (18).

|

18 |

These weights  represent the relative importance of each local feature for the current hidden state

represent the relative importance of each local feature for the current hidden state  . Using the normalized weights

. Using the normalized weights  , the attention mechanism computes a weighted sum of the rows of

, the attention mechanism computes a weighted sum of the rows of  , resulting in a context vector

, resulting in a context vector  , EQU (19).

, EQU (19).

|

19 |

Where,

encapsulates the most relevant temporal features for the current time step

encapsulates the most relevant temporal features for the current time step  .

.

The context vector  is concatenated with the current hidden state

is concatenated with the current hidden state  to form an augmented vector, EQU (20)

to form an augmented vector, EQU (20)

|

20 |

The augmented vector  is then passed through a Fully Connected (FC) layer to generate the final attention-enhanced hidden state

is then passed through a Fully Connected (FC) layer to generate the final attention-enhanced hidden state  , EQU (21)

, EQU (21)

|

21 |

where:

is a trainable weight matrix,

is a trainable weight matrix, It is a trainable bias vector.

It is a trainable bias vector.

The attention mechanism operates over all time steps  , producing a sequence of enhanced hidden states

, producing a sequence of enhanced hidden states  .

.

This sequence can be formally represented as EQU (22)

|

22 |

Where,

The attention module’s final output encapsulates the temporal and feature-level importance of the entire sequence.

The attention module’s final output encapsulates the temporal and feature-level importance of the entire sequence.

Feedback mechanism

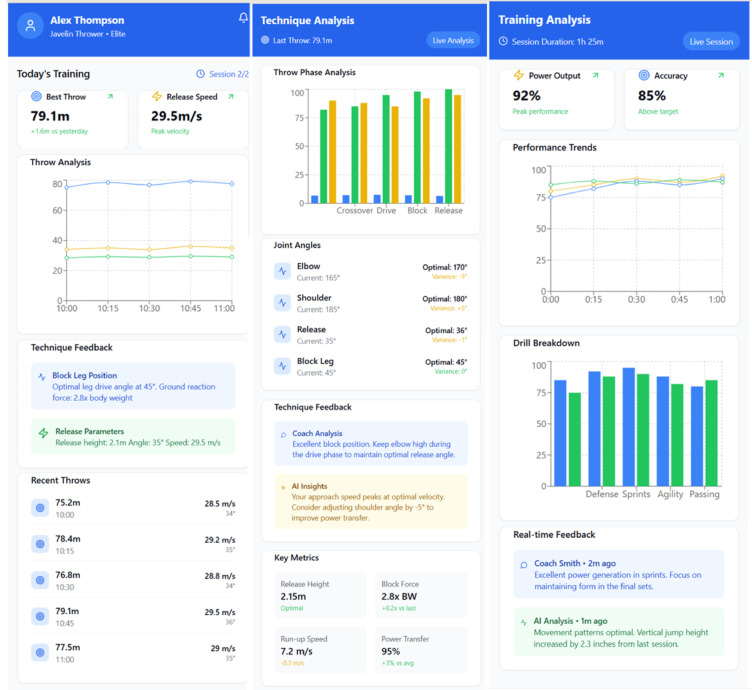

The analysis from the proposed TCN + BiLSTM + Attention Mechanism is presented visually as an App for individual athletes and their sports. Figure 7 shows the snapshots of the app interface for a javelin thrower, demonstrating how complex AP analytics are transformed into an intuitive, user-friendly dashboard. The visualization integrates real-time AP metrics, technique analysis, and AI-driven visions processed by IoT-E-DLM into a comprehensive feedback system. The dashboard interface, exemplified by the javelin throw analysis, presents multiple analytical views derived from the model’s output. The athlete’s performance metrics are continuously monitored and displayed through interactive visualizations, including throw phase analysis, joint angle measurements, and performance trends. The system provides detailed technical feedback by translating the model’s DL analysis into actionable insights, as shown in the technique feedback section, where specific joint angles and movement parameters are compared against optimal values. The real-time analysis capabilities of the TCN + BiLSTM + Attention Mechanism are reflected in the live session tracking, where performance metrics such as throw distance (79.1 m) and release speed (29.5 m/s) are instantaneously processed and displayed. The model’s temporal pattern recognition enables detailed phase-wise analysis of each throw, while the attention mechanism highlights key technical features requiring focus, delivered through coach and AI-generated visions.

Fig. 7.

Snapshot of the app interface.

Model implementation

Implementing the proposed IoT-E-DLM monitoring system requires careful consideration of data collection, preprocessing, and model training trials. This section outlines the methodical approach for implementing the system in real-world collegiate sports applications.

A. Ethics Statement: This study was tested in full compliance with institutional and national ethical standards governing human subjects research. Before the initiation of data collection, the research protocol received formal approval from the Ethics Committee of the College of Physical Education, Shangqiu University, Shangqiu, Henan, 476,000, China. The procedures followed in this study conformed to the principles outlined in the declaration of Shangqiu University and adhered to all applicable guidelines and regulatory models concerning research involving human participants.

Data collection

The data collection process was conducted across three major University sports facilities in Shangqiu, Henan, 476,000, China, from September 2023 to August 2024. The study involved 147 student-athletes from Shangqiu University athletics programs, including track and field (n = 42), basketball (n = 31), soccer (n = 38), and swimming (n = 36). The collection protocol was approved by the university’s institutional review board (IRB-2023-0892), and informed consent was attained from all participating athletes following the Shangqiu University, China Research Ethics Committee guidelines. Data collection was performed using the IoT sensor network described in Sect. 3.2.1, with sensors strategically positioned to capture comprehensive performance metrics.

The collected data encompasses three primary classes:

Physiological Parameters: Heart rate variability was recorded continuously at 100 Hz using optical sensors, while electrodermal activity was sampled at 50 Hz. Blood oxygen saturation levels were monitored at 1 Hz intervals during training sessions. These measurements showed athletes’ cardiovascular responses and autonomic nervous system activity during numerous training intensities.

Biomechanical Metrics: Motion data was captured using IMUs sampling at 1000 Hz, recording tri-axial accelerations, angular velocities, and magnetic field measurements. Force plates integrated into the Shangqiu University, Shangqiu, Henan, 476,000, China, collected ground reaction forces at 1000 Hz during jumping, landing, and cutting maneuvers. Global Positioning System (GPS) modules operating at 10 Hz tracked spatial positioning during outdoor activities at Shangqiu University’s Olympic-standard training facilities.

Environmental Conditions: Ambient temperature (range: 12.3 °C to 34.8 °C), humidity (range: 45–92%), and barometric pressure (range: 998.2 to 1015.7 hPa) were recorded at 0.1 Hz to account for environmental factors affecting performance. Indoor training facilities were equipped with Ultra-Wideband (UWB) beacons providing positioning data at 200 Hz for precise movement tracking.

The data collection set-up implemented a robust synchronization protocol ensuring temporal alignment across all sensor streams. A custom-developed mobile application facilitated real-time monitoring of sensor connectivity and data quality.

This acquisition process generated 2.73 TB of raw sensor data consisting of:

Training Sessions: 3,482 individual sessions with a duration between 45 and 180 min. Competition Events: 247 events with complete sensor coverage. Recovery Periods: 1,043 monitored recovery sessions. Baseline Measurements: 438 controlled baseline assessment sessions.

Automated quality checks validated data in real time, which flagged anomalous readings for investigation. The system data capture success rate was 98.37%, with the primary sources of data loss being temporary sensor disconnections (1.12%), equipment failures during training transitions (0.38%), and environmental interference (0.13%).

Preliminary data validation was performed at each facility, at the edge computing node, before sending the data to the cloud infrastructure hosted at the Hangzhou Data Center (The Largest Data Center in the World). The validation process included range checking, sensor drift detection, and signal quality assessment, with automated alerts generated for any deviations from recognized quality thresholds. The edge nodes maintained an average processing latency of 12.4 ms for real-time data validation.

Dataset description

The dataset, collected from the Shangqiu University sports facilities, is a multivariate data stream classified by sport type, training phase, and measurement parameters. Data for each athlete was anonymized and assigned a unique identifier. Timestamps were synchronized using the Network Time Protocol (NTP), with all sensor streams having a maximum offset of ± 0.5 ms.

The raw dataset consists of 2.73 TB of time-series data, divided into four main types depending on the collection scenarios. The training data constitutes 67.4% (1.84 TB) of the whole dataset and was collected during regular training sessions of everyday activities. The data contains continuous streams from all sensor types with a temporal resolution ranging from 1 to 1000 Hz, depending on the sensor type. Training sessions were coded for intensity level, with 23.7% described as light intensity, 45.2% as moderate intensity, and 31.1% as high intensity according to the coaches’ perception and zones of heart rate.

Competition Data represents 18.2% (497 GB) of the dataset, collected during intercollegiate competitions and formal evaluation events. This subset includes high-frequency sampling across all sensors with additional event markers for specific performance milestones. Recovery Data constitutes 9.3% (254 GB) of the dataset, focusing on post-training and post-competition recovery periods. The data primarily consists of physiological parameters and minimal motion metrics. Baseline Data comprises 5.1% (139 GB) of the data collected during standardized assessment protocols. This subset references normal performance parameters and includes controlled movement patterns.

The track and field dataset encompasses 896 training sessions from 42 athletes, with an average session duration of 127.3 min. The primary metrics include sprint velocity, stride parameters, and ground reaction forces, captured at a mean sampling rate of 947.3 Hz for motion capture. Basketball data consists of 873 training sessions from 31 athletes, averaging 98.6 min per session. These sessions focused on jump height, acceleration patterns, and court positioning metrics, sampled at 832.7 Hz for motion capture.

Soccer training data includes 892 sessions from 38 athletes, averaging 112.4 min. The data emphasizes running patterns, kick force, and team positioning, collected at a mean sampling rate of 891.5 Hz for motion capture. Swimming data comprises 821 training sessions from 36 athletes, averaging 104.8 min per session, focusing on stroke rate, body rotation, and velocity profiles, with motion capture sampling at 784.2 Hz.

The data structure maintains consistent formatting for each sport class while accommodating sport-specific parameters. The temporal alignment of multi-sensor data streams was maintained by timestamp synchronization, with a maximum temporal disparity of 0.8 ms between any two sensor streams. Data quality metrics across the entire dataset indicate an average signal-to-noise ratio of 42.3 dB, with missing data points accounting for 1.63% of the total dataset, primarily during equipment adjustments. Sensor drift was maintained below 0.15% per hour, and cross-sensor temporal alignment achieved 99.92% accuracy.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing phase of the collected data involved multiple stages of cleaning, normalization, and transformation to ensure data quality and compatibility with the deep learning models. The preprocessing pipeline was implemented using Python 3.9 with NumPy and Pandas libraries, executing on the cloud infrastructure described in Sect. 3.2.3. Initial data cleaning addressed missing values and outliers across all sensor streams. Missing values, accounting for 1.63% of the raw data, were handled using forward fill for gaps shorter than 100 ms and linear interpolation for gaps between 100 and 500 ms. Gaps exceeding 500 ms were flagged, and the corresponding sequences were excluded from the training dataset to maintain data integrity. Outlier detection employed a modified z-score method with a sliding window of 1 Sec, where values exceeding 3.5 standard deviations from the local mean were identified and processed using a Savitzky-Golay filter with a window length of 11 samples and a polynomial order of 3.

Signal normalization was performed independently for each sensor type to account for different measurement scales and units. Accelerometer data was normalized to gravitational units (g), while angular velocities were converted to radians per second. Physiological signals underwent min-max normalization within individual training sessions to preserve relative changes while maintaining interpretability. GPS coordinates were transformed into relative distances from session starting points, and all temporal measurements were standardized to a ms resolution. Temporal alignment of multi-sensor data streams requires precise synchronization. A reference time series was established using the highest frequency sensor (IMU at 1000 Hz), and all other data streams were resampled to match this frequency using cubic spline interpolation—the resampling process maintained signal features while ensuring consistent temporal resolution across all measurements. Cross-correlation analysis between synchronized streams showed an average temporal alignment error of less than 0.8 ms.

Feature engineering focused on extracting relevant performance indicators from the raw sensor data. For motion analysis, this work computed jerk (rate of acceleration change), power metrics (combining force and velocity), and stability indices (based on the center of mass movements). Physiological data processing included heart rate variability metrics (RMSSD, pNN50) and training load indicators (TRIMP scores). These engineered features were validated against domain expertise provided by the coaching staff at Shangqiu University, China. The pre-processed data was segmented into fixed-length windows of 10 Sec, with 50% overlap, chosen based on preliminary analysis of typical motion patterns in the target sports. Each window contained 10,000 samples per sensor channel (1000 Hz), ensuring sufficient temporal context for the deep learning models while maintaining computational feasibility. Window boundaries were adjusted to avoid splitting significant motion events, identified through acceleration magnitude thresholds.

Data augmentation techniques were applied to increase the robustness of the models and deal with class imbalance in the activity recognition tasks. These included random scaling (± 10% amplitude variation), temporal shifting (± 100 ms), and additive Gaussian noise (SNR = 20 dB). The parameters for augmentation were tuned using cross-validation so as not to overfit while trusting the physical probability of the augmented signals.

The final preprocessing step was data serialization and optimization for storage. All processed windows were stored in HDF5 format, with each file containing multiple data channels and associated metadata. Optimized for fast random access during model training, the storage structure achieved a 4:1 compression ratio using GZIP encoding with read speeds suitable for a GPU-based training pipeline.

The entire preprocessing pipeline was automated and deployed to the cloud infrastructure, where it processed incoming streams in near real-time, with a maximum latency of 1.5 s. Quality control metrics were continuously monitored, and automated alerts were generated for any anomalies in the preprocessing results to ensure data quality consistency throughout the study period.

Training the proposed model

The proposed TCN + BiLSTM + Attention mechanism is trained using the PyTorch version 1.12.0 on the high-performance computing HPC cluster at Shangqiu University, China. The setup was equipped with NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPUs with 80 GB VRAM each, enabling large-scale time-series datasets collected in numerous sports activities to be processed efficiently. The model followed the specifications described in Sect. 3.4. Hyperparameter optimization was done through systematic grid search coupled with cross-validation. The TCN component employed three parallel branches with kernel sizes of 5, 7, and 9, and the dilation rates followed an exponential progression across layers  . The BiLSTM consisted of 256 hidden units in each direction, while the attention mechanism used 8 attention heads with a key dimension of 64.

. The BiLSTM consisted of 256 hidden units in each direction, while the attention mechanism used 8 attention heads with a key dimension of 64.

Training was conducted in phases to ensure convergence and generalization. The model parameters were initialized using initialization for convolutional layers and orthogonal initialization for recurrent layers. The Adam optimizer, configured with an initial learning rate of 3 × 10−4 was used for optimization. The learning rate was adjusted dynamically through a cosine annealing schedule with warm restarts every 10 epochs. Gradient clipping was applied with a maximum norm of 1.0 to address exploding gradients. Each training batch consisted of 64 sequences containing 10,000 timesteps spanning multiple sensor channels. Gradually, accumulation accommodated memory constraints, where gradients were accumulated over four mini-batches before updating model parameters.

The loss function was a weighted combination of multiple objectives, EQU (23)

|

23 |

Where:

: Mean squared error, penalizing prediction errors for performance metrics.

: Mean squared error, penalizing prediction errors for performance metrics. : Temporal consistency loss, encouraging smooth and coherent predictions across timesteps.

: Temporal consistency loss, encouraging smooth and coherent predictions across timesteps. : Supervised attention mechanism loss, aligning attention weights with key data patterns.

: Supervised attention mechanism loss, aligning attention weights with key data patterns.

The weighting coefficients were determined through ablation studies with  , and

, and  .

.

The model exhibited convergence after 157 epochs, with early stopping implemented based on validation loss, using a patience of 15 epochs. The training process consumed approximately 218 h of GPU time, processing 2.73 TB of pre-processed data. Regular checkpoints were saved every five epochs, and the best-performing model was selected based on validation metrics.

To ensure robust evaluation, 5-fold cross-validation was employed, stratified by athlete and sport type. The final model performance was assessed on a held-out test set comprising  of the total data, which had not been used during training or validation. Performance metrics were computed independently for each sport category to account for discipline-specific features and requirements.

of the total data, which had not been used during training or validation. Performance metrics were computed independently for each sport category to account for discipline-specific features and requirements.

Several regularization techniques were incorporated to prevent overfitting. Dropout layers were inserted after each key component, with dropout rates of  , and 0.1 for the TCN, BiLSTM, and Attention mechanism. Moreover, L2 regularization was applied with a weight decay coefficient of

, and 0.1 for the TCN, BiLSTM, and Attention mechanism. Moreover, L2 regularization was applied with a weight decay coefficient of  . Dynamic data augmentation techniques described in Sect. 4.3 were applied during training to improve the generalization abilities of the model.

. Dynamic data augmentation techniques described in Sect. 4.3 were applied during training to improve the generalization abilities of the model.

The training was closely monitored using TensorBoard to track metrics, including training and validation losses, attention weight distributions, and gradient norms. Learning rate schedules were adjusted to ensure optimal convergence based on the trends observed in validation, thereby preventing local minima (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for TCN + BiLSTM + Attention mechanism Training.

| Component | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Network Parameters | ||

| TCN | Kernel Sizes | [5, 7, 9] |

| Dilation Rates | [1, 2, 4, 8] | |

| Number of Filters | 64 per branch | |

| Dropout Rate | 0.2 | |

| BiLSTM | Hidden Units | 256 (each direction) |

| Number of Layers | 2 | |

| Dropout Rate | 0.3 | |

| Attention | Number of Heads | 8 |

| Key Dimension | 64 | |

| Dropout Rate | 0.1 | |

| Training Parameters | ||

| Optimization | Optimizer | Adam |

| Initial Learning Rate | 3 × 10^−4 | |

| Weight Decay | 1 × 10^−5 | |

| Gradient Clip Norm | 1.0 | |

| Training Process | Batch Size | 64 |

| Gradient Accumulation Steps | 4 | |

| Number of Epochs | 157 | |

| Early Stopping Patience | 15 | |

| Loss Function | MSE Weight ( ) ) |

0.6 |

Temporal Weight ( ) ) |

0.3 | |

Attention Weight ( ) ) |

0.1 | |

| Data Processing | Sequence Length | 10,000 timesteps |

| Sampling Rate | 1000 Hz | |

| Window Overlap | 50% | |

| Model Settings | Random Seed | 42 |

| Cross-validation Folds | 5 | |

| Test Set Ratio | 0.2 | |

Experimental setup

The proposed IoT-E-DLM is implemented and evaluated on a complete computing setup at the Shangqiu University Sports Centre. Primary computation is performed on a high-performance computing cluster composed of 4 NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPUs, each with 80 GB VRAM, connected by NVLink with 600GB/s bi-directional bandwidth. The computing nodes have dual AMD EPYC 7763 processors, 512 GB DDR4-3200 ECC memory, and a 4 TB NVMe SSD array in a RAID 0 configuration.

The training facilities were deployed with edge computing nodes using the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin Developer Kits, equipped with 32 GB LPDDR5 memory and 64 GB eMMC 5.1 storage. The cloud set-up used Google Cloud Platform’s N2 machine series with 32 vCPUs and 128 GB memory for each instance, running in the East Asia region and supplemented with NVIDIA T4 GPUs for model inference.

The software stack included Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, PyTorch 1.12.0, CUDA Toolkit 11.7, and Python 3.9.7, with PostgreSQL 13.4 as the database backend. Real-time data acquisition was performed by custom C + + firmware optimized for low latency, connected via a dedicated 5G network set-up with 1 Gbps bandwidth and a maximum latency of 10 ms. Environmental conditions were maintained at 20 °C (± 1 °C) and relative humidity of 45% (± 5%) using redundant power supplies to ensure uninterrupted operation.

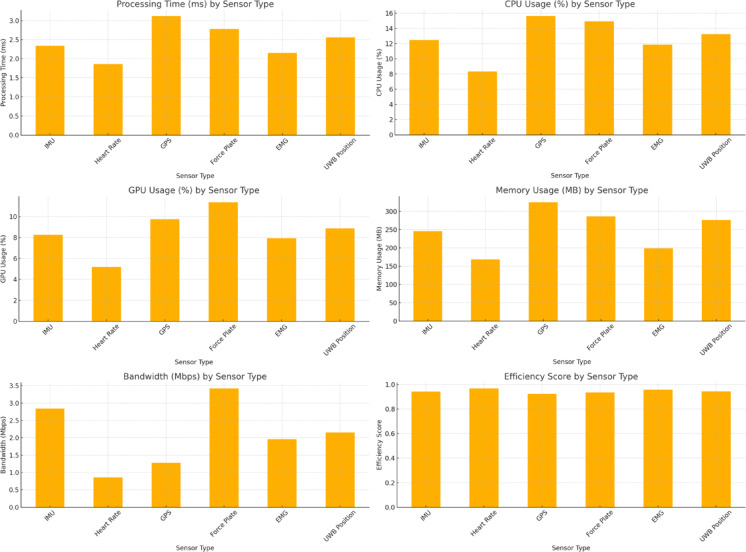

System performance metric definitions

This section defines the core performance metrics used to evaluate the IoT-E-DLM model, which quantify prediction accuracy, temporal precision, system efficiency, and computational overhead.

Total System Latency: Total system latency

refers to the end-to-end delay incurred during a complete processing cycle from data acquisition at the edge node to inference and feedback delivery after cloud-based analytics. This metric accounts for edge processing, network transmission, and cloud inference time, EQU (24).

refers to the end-to-end delay incurred during a complete processing cycle from data acquisition at the edge node to inference and feedback delivery after cloud-based analytics. This metric accounts for edge processing, network transmission, and cloud inference time, EQU (24).

|

Where.

: Latency for edge-side preprocessing and lightweight inference.

: Latency for edge-side preprocessing and lightweight inference. : Latency from transmitting data between the edge and the cloud.

: Latency from transmitting data between the edge and the cloud. Latency for executing the deep learning model in the cloud.

Latency for executing the deep learning model in the cloud.

-

2.

Prediction Accuracy: Accuracy quantifies the proportion of correct predictions for categorical outcomes, such as activity recognition or classification of athletic phases. It is relevant in applications where binary or multi-class outcomes are derived from sensor signals, EQU (25).

|

Where:

: Total number of test samples.

: Total number of test samples. : Predicted and ground-truth labels.

: Predicted and ground-truth labels. : Indicator function (1 if true, 0 otherwise).

: Indicator function (1 if true, 0 otherwise).

-

3.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): MAE measures the average magnitude of prediction errors without considering direction. It is used to evaluate regression performance for continuous variables such as velocity, joint angles, or heart rate, EQU (26).

|

-

4.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): RMSE emphasizes larger errors by squaring the deviations before averaging. It is suitable for penalizing high-variance deviations in predicted biomechanical or physiological parameters, EQU (27).

|

-

5.

Coefficient of Determination

: The

: The  metric indicates how well predicted values approximate the actual data distribution. An