Abstract

Background

Ileus, a postoperative complication after colorectal surgery, increases morbidity, costs, and hospital stays. Assessing risk of ileus is crucial, especially with the trend towards early discharge. Prior studies assessed risk of ileus with regression models, the role of deep learning remains unexplored.

Methods

We evaluated the Gated Recurrent Unit with Decay (GRU-D) for real-time ileus risk assessment in 7349 colorectal surgeries across three Mayo Clinic sites with two Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems. The results were compared with atemporal models on a panel of benchmark metrics.

Results

Here we show that despite extreme data sparsity (e.g., 72.2% of labs, 26.9% of vitals lack measurements within 24 h post-surgery), GRU-D demonstrates improved performance by integrating new measurements and exhibits robust transferability. In brute-force transfer, AUROC decreases by no more than 5%, while multi-source instance transfer yields up to a 2.6% improvement in AUROC and an 86% narrower confidence interval. Although atemporal models perform better at certain pre-surgical time points, their performance fluctuates considerably and generally falls short of GRU-D in post-surgical hours.

Conclusions

GRU-D’s dynamic risk assessment capability is crucial in scenarios where clinical follow-up is essential, warranting further research on built-in explainability for clinical integration.

Subject terms: Health services, Prognosis

Plain language summary

A common complication after colorectal surgery is ileus, during which a person is not able to tolerate swallowing food and has digestive problems due to a lack of muscle contractions to move food through the digestive system. It can lead to longer hospital stays and higher costs. Predicting its risk early is important, especially for patients who are planning to go home. We tested a computational model called GRU-D on clinical data obtained from over 7000 surgeries at three Mayo Clinic hospitals. GRU-D worked well across different hospitals and systems and was able to predict risk of ileus after surgery. Future research should focus on making its predictions easier to explain and explore its use in clinical care. Ultimately, it could improve post-operative care for patients.

Ruan et al. evaluated GRU-D for real-time ileus risk after 7349 colorectal surgeries across Mayo Clinic sites. Despite sparse electronic health record (HER) data, GRU-D outperforms static models and is transferable across hospital sites and EHR systems, highlighting its potential for dynamic risk tracking and future clinical integration.

Introduction

Ileus, a temporary lack of the normal muscle contractions of the intestines causing bloating, vomiting, constipation, cramps, and loss of appetite, poses a common challenge following colorectal surgery, contributing to heightened morbidities, increased costs, and prolonged hospital stays1. With an occurrence rate of 10–30% and typically manifesting within 6–8 days post-surgery2, ileus management is crucial due to its impact on both hospitals and patients. For hospitals, the factors involve a payment reform that emphasizes extended care episodes and Medicare penalties on 30 days readmissions, an increasing preference for outpatient surgery to conserve limited hospital resources amid the COVID-19 pandemic3, along with a contentious surge in interest for same-day or next-day discharge4. For patients, ileus is a miserable complication with associated nausea, vomiting, and the need for a nasogastric tube, leading to major discomfort and immobility. If ileus persists beyond several days, patients may require invasive interventions like total parenteral nutrition and central venous catheter placement, making it a serious and burdensome complication5. Efficiently identifying the risk of ileus to enable early intervention stands as a crucial factor in enhancing surgical outcomes. While various studies have discussed the prediction of ileus6–10, predominantly utilizing multivariate logistic regression techniques, there exists a notable gap in research concerning deep learning-based approaches in ileus prediction. This is particularly intriguing given the widespread application of deep learning in tackling other postoperative complications11–13.

We previously benchmarked the Gated Recurrent Unit with Decay (GRU-D), a RNN based architecture proposed by Che et al.14, in making real-time risk assessment of postoperative superficial infection, wound infection, organ space infection, and bleeding12. GRU-D exhibited advantages in automated missing imputation, the flexibility to tailor sampling intervals, and the capacity to update and enhance risk assessment by incorporating newly received measurements. These features position GRU-D as an ideal candidate for risk modeling associated with longitudinal clinical data, a domain often characterized by substantial missingness in data, asynchronous updates, and the need for prompt risk assessment.

The considerable practical values that GRU-D holds underscore the importance of examining its applicability across a variety of real-world contexts. Here we aim to evaluate the feasibility, performance, and transferability of GRU-D in assessing risk of postoperative ileus across two electronic health record (EHR) systems in three separate hospital sites affiliated with Mayo Clinic. This evaluation takes place against the backdrop of the increasing significance of time series data, a prevalent format in clinical settings used to chronicle patient longitudinal information, within the realm of transferability research. Notably, prior research on transferability involving time series data has primarily centered around neurology and cardiology15,16. There exists a substantial dearth of research concerning the transfer learning of time series data related to surgical contexts, with only a limited number of studies being documented 10.48550/arXiv.2102.1230817. Our analysis shows that GRU-D models demonstrate enhanced performance by integrating new measurements, exhibit robust transferability across hospital sites and EHR systems despite the extreme data sparsity of real-world data, and generally outperform logistic regression and random forest models in post-surgical hours. These strengths highlight the need for further research into built-in explainability to support clinical integration.

Methods

CRC surgery samples

The study consists of 7349 colorectal surgery records corresponding to 7103 patients with colorectal surgeries performed at Mayo Clinic Rochester (MR), Arizona (MA), and Florida (MF) hospital sites between 2006 and 2022 as part of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program18. Specifically, due to a transition from Centricity to EPIC system in 2018, data from MR is split into two parts as MR centricity (MRcc) and MR EPIC (MRep). Whereas data from both MA and MF are after 2018 with the EPIC system. The distribution of surgery date by sites and EHR systems are illustrated in Fig. 1. The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board (IRB number: 15-000105). All patients whose data is included in this study gave informed consent for their data to be used for research.

Fig. 1. Distribution of colorectal surgery date and time to first ileus diagnosis across site-systems.

a Distribution of colorectal surgery time. b Distribution of time to first ileus diagnosis after colorectal surgery. Blue, yellow, green, purple colors represent colorectal surgery records from MRcc, MRep, MAep, MFep, respectively. MRcc Mayo Rochester Centricity system, MRep Mayo Rochester EPIC system, MAep Mayo Arizona EPIC system, MFep Mayo Florida EPIC system.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the study population

| Hospital site full name | Mayo Clinic Rochester | Mayo Clinic Rochester | Mayo Clinic Arizona | Mayo Clinic Florida | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital site abbreviation | MR | MR | MA | MF | ALL |

| EHR system | Centricity | EPIC | EPIC | EPIC | – |

| Time period | 2006–2018 | 2018–2021 | 2018–2022 | 2020–2022 | |

| Site-system abbreviation | MRcc | MRep | MAep | MFep | – |

| Number of patients | 3535 | 2352 | 898 | 318 | 7103 |

| Number of records | 3598 | 2493 | 932 | 326 | 7349 |

| Age at surgery | 59 [45,71]a | 58 [45,69] | 61 [47,71] | 62 (48,71) | 59 (46,70) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1767 (50%) | 1098 (47%) | 439 (49%) | 147 (46%) | 3451 (49%) |

| Female | 1768 (50%) | 1252 (53%) | 459 (51%) | 171 (54%) | 3650 (51%) |

| Ileus cases | 274 (7.6%) | 475 (19.1%) | 187 (20.1%) | 76 (23.3%) | 1012 (13.8%) |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 3315 (94%) | 2161 (92%) | 818 (91%) | 289 (91%) | 6583 (93%) |

| Non-caucasian | 220 (6%) | 191 (8%) | 80 (9%) | 29 (9%) | 520 (7%) |

| Surgery subtype | |||||

| Laparoscopy, colectomy | 978 (27%) | 530 (21%) | 268 (29%) | 68 (21%) | 1844 (25%) |

| Laparoscopy, colectomy, partial | 634 (18%) | 578 (23%) | 265 (28%) | 87 (27%) | 1564 (21%) |

| Removal of colon | 701 (19%) | 409 (16%) | 120 (13%) | 55 (17%) | 1285 (17%) |

| Removal of colon, partial | 505 (14%) | 460 (18%) | 147(16%) | 69 (21%) | 1181 (16%) |

| Removal of rectum | 255 (7%) | 111 (4%) | 18 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 393 (5%) |

| Othersb | 525 (15%) | 405 (16%) | 124 (13%) | 38 (12%) | 1092 (15%) |

| Surgery time duration, minutes | 188 (136, 256) | 238 (158, 353) | 198 (138, 286) | 236 (185, 319) | 204 (143, 290) |

aData shown as n(%) or median(IQR).

bSee Table S1 for a comprehensive list of subtypes.

Ileus status ascertainment and chart review

The identification of ileus was followed by the application of a standardized Natural Language Processing (NLP) pipeline through the Open Health NLP (OHNLP) infrastructure. Additional details about the NLP methodology can be found in our previous studies19,20. Briefly, the development of the ileus algorithm followed an iterative process, which included corpus annotation, symbolic ruleset prototyping, ruleset refinement, and final evaluation. The validated ileus rulesets were then integrated into the OHNLP Backbone and MedTaggerIE NLP pipeline, which includes a built-in context classifier (e.g., status, subject, and certainty).

Chart review was performed on NLP-ascertained 200 positives and 200 negatives by a clinical informatician, with a surgical physician providing the final decision on any uncertain cases. Among the 200 NLP positives, 3 were identified as false positives: one merely speculating the patient is starting to develop an ileus and another identified as obstruction caused by a malignant duodenum tumor rather than ileus. Among the 200 NLP negatives, 4 were identified as false negatives, mainly due to ambiguous scenarios that are suggestive or likely to be ileus.

Training data and held-out data selection

For surgery records of each site, 30% were randomly selected as held-out. The remaining 70% were conditional-randomly split into six equal-sized chunks, which were then used to create six-fold training data by leaving one chunk out at a time (Table 2). Randomization was performed 100 times to select the one that best matched the characteristics across chunks and sites, aiming to make them similar in terms of the rate of ileus complications, surgery duration, gender, and race.

Table 2.

Training and held-out split

| Site-System | MRcca | MRepb | MFepc | MAepd | ALL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3598 | 2493 | 326 | 932 | 7349 |

| Ileus cases | 274 | 475 | 76 | 187 | 1012 |

| Case (%) | 7.60% | 19.10% | 23.30% | 20.10% | 13.80% |

| Held-out | 1079 | 747 | 97 | 278 | 2201 |

| Cases | 75 | 144 | 25 | 57 | 301 |

| Case (%) | 7.00% | 19.30% | 25.80% | 20.50% | 13.70% |

| Training | 2519 | 1746 | 229 | 654 | 5148 |

| Cases | 199 | 331 | 51 | 130 | 711 |

| Case (%) | 7.90% | 19.00% | 22.30% | 19.90% | 13.80% |

aMayo Rochester Centricity system.

bMayo Rochester EPIC system.

cMayo Florida EPIC system.

dMayo Arizona EPIC system.

Transfer learning naming rules and transfer schemes

Throughout the paper we adhere to the following naming rules for clarity. For each dataset, subscripted MRcc, MRep, MFep, and MAep represent the dataset originated from Mayo Clinic Rochester Centricity, Rochester EPIC, Florida EPIC, and Arizona EPIC system, respectively. Source training () and source held-out () represent data from the training and held-out chunks of source site-system(s), respectively. Target training () and target held-out () represent data from the training and held-out chunks of the target site-system(s), respectively. For example, represents source training dataset from Mayo Clinic Rochester Centricity system. We use function to represent deep learning model to make a distinction from the corresponding dataset it was trained upon. For example, represent models trained from dataset.

For each site-system, the six chunks of training data were used to train six independent models by iteratively leaving one chunk out. The models were named, take MRcc for example, as (an ensemble of six models). We consider five model training scenarios (Take MRep for example), including local learning (i.e., training on and predict ) and four scenarios of transfer learning (transfer from for example) detailed below, according to solution based categorization21.

Brute-force transfer: Directly apply to .

Single-source instance transfer: Combine training data records from MRcc and MRep and apply to .

Parameter transfer: Continuous training of on MRep training data. The models were named , which were then applied to .

Multi-source instance transfer: Train brand new models by combining training data from all sites and then applied to .

GRU-D model architectures

The basic architecture of the GRU-D model (https://github.com/PeterChe1990/GRU-D) was proposed by ref. 14, by incorporating into the regular GRU model a missing decay mechanism as shown below.

| 1 |

where is the missing value indicator for feature d at timestep t. takes value 1 when is observed, or 0 otherwise, in which case the function resorts to weighted sum of the last observed value and empirical mean calculated from the training data for the dth feature. Furthermore, the weighting factor is determined by

| 2 |

where is a trainable weights matrix and is the time interval from the last observation to the current timestep. When is large (i.e., the last observation is far away from current timestep), is small, results in smaller weights on the last observed value , and higher weights on the empirical mean (i.e., decay to mean).

For each timestep of each patient, sigmoid activation function is applied to the hidden output to generate a predicted probability (0–1) of developing ileus within 30 days after surgery. is evaluated against the true class label (), i.e., whether or not the patient actually developed ileus within 30 days of surgery. Specifically, the loss function is as follow

| 3 |

where N is the number of training samples in a batch. is the weights for sample i (minor group inverse weighted). is the maximum allowed timesteps (i.e., the timesteps before ileus onset, if any) for sample i. is the observed outcome. is the predicted probability for sample i at timestep t.

Competing models

The performance of GRU-D model was compared with atemporal logistic regression with lasso regularization (Logit) (R package glmnet) and atemporal random forest (RF) (R package randomForestSRC). For both models, we implemented unlimited time last value carry forward to fill in the missing values. The remaining missing values were imputed with RF adaptive tree imputation22 with three iterations. Specifically, the imputation for training and held-out data from different sites were implemented separately. Separate models were trained at integer days (i.e., −4, −3 … 13, 14) and used to make predictions at corresponding time points. Features with missing proportions greater than 0.2 were removed from analysis. For the Logit model, the default configurations (alpha=1, lambda=100) were adopted. For the RF model, the number of trees were set to 100 with a minimum of 10 terminal nodes.

Input features and feature selection

We included features that appeared in all four site-systems (Table S1). Notably, for the GRU-D model no exclusion of features by missing proportion was performed, to respect real world scenarios where data availability may vary across sites.

We meticulously reviewed each feature to classify it as continuous or categorical. To support transfer learning, we manually established a biologically meaningful mapping from Centricity to EPIC categories for each categorical feature, resulting in a semi-homogeneous transfer learning setup. For example, we mapped the 29 fine-grained “Diet” categories in the Centricity system to the 3 corresponding categories (“Nothing by mouth”, “Diet 50”, and “Diet 100”) in the EPIC system.

Categorical features underwent one hot encoding (i.e., each category is represented by a vector with a single “1” and “0’s” in all other positions, ensuring that the model treats categories without implying any order between them.) based on categories presented across all four site-systems, while continuous features were z-score normalized using mean and standard deviation values calculated from the source training data. During parameter transfer learning, we updated the mean and standard deviation values with corresponding values from the target training data, if available. To avoid extreme values, the z-score values were hard clamped to between −5 and 5 before being fed into the machine learning models.

Sampling scheme of dynamic and static features

Dynamic features were sampled at a 4-h interval from 4 days before surgery to up to 14 days after surgery, using the last measurement in the past 4 h, or marked as missing if no value was spotted. A maximum of 14 days follow-up allows the model to detect 99% of ileus cases and generates 109 timesteps for each feature of each patient. Static features were replicated across timesteps. Age is converted to within range 0–1 by dividing by 100. Surgery time duration is hourly based. Surgery subtypes are one-hot encoded into 14 categories.

Statistics and reproducibility

Evaluation metrics

We evaluated established metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), average precision (weighted average precision across all sensitivity levels), and the F-score (calculated at the optimal threshold that maximizes the geometric mean of sensitivity and specificity). Additionally, we explored two clinically focused metrics: flag rate (the proportion of monitored patients to achieve 60% sensitivity on all remaining ileus cases within 30-days after surgery) and 24-h ileus (the number of true ileus cases in the predicted 3rd and 4th risk quartiles that were actually observed within the next 24 h). For comparability between GRU-D and atemporal models, the clinical utility-related metrics were evaluated exclusively on integer days (−96 h, −72 h,…, 24 h, 48 h…). Patients who had already developed ileus complications before the specific timestep of interest were removed, thus eliminating confounding effects from prior occurrences of the complication.

We examined two approaches for assessing metrics in our study. Taking AUROC as an example, the first approach, termed last-timestep analysis (AUROClast), evaluates the predicted probability at the final timestep before ileus onset (or the 109th timestep if no ileus) against ileus outcome. This approach is specifically designed to benchmark the transferability of GRU-D models using all available information. The second approach, termed timestep-specific analysis (AUROCt), involves evaluating the predicted probability at a particular timestep t against ileus outcome, while excluding patients with ileus diagnosed prior to that timestep. For each evaluation metric, the confidence interval (CI) is based on the six models obtained through the six-fold training data.

Permutation feature importance

The permutation feature importance test is performed by randomly rearranging the sample IDs of a given feature in the target dataset. For each of the six models (obtained from the six-fold training data), five permutations were executed, resulting in a total of 30 permutations for each feature at every timestep. The AUROCt was assessed both before and after the permutation. The mean discrepancy in AUROCt across all timesteps (calculated as before permutation minus after permutation) was used to gauge the model’s reliance on the specific feature.

Results

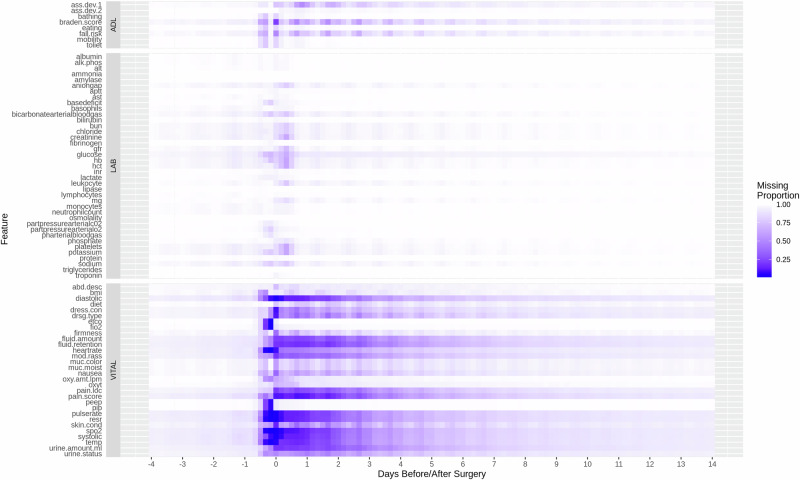

Feature sparsity of real-world data

We visualized the missing proportion of selected features (Labs, Vitals, ADL (Assisted Living Status)) in Fig. 2, and CCS codes presence rate in Supplementary Fig. 1. The EHR data from the studied hospital sites are predominantly sparse across multiple modalities throughout the follow-up period from 4 days before to 14 days after surgery. From surgery completion (i.e., index date) to within 24 h after surgery, there are on average 72.2% labs, 26.9% vitals, and 49.3% ADL lacking a measurement. With a 4-h interval-based time grid, the average missing proportions throughout follow-up are 98.7%, 84%, 95.8% for the three modalities, respectively. Notably, in adhering to a realistic approach regarding data availability, no feature was eliminated based on its missing proportion in the assessment of GRU-D models. Consequently, the extent of data sparsity depicted in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1 reflects the input consumed by the GRU-D models.

Fig. 2. Missing proportion of selected features.

X-axis represents time points from 4 days before surgery to 14 days after surgerys at a 4-h interval. Point 0 on the x-axis represents surgery end time. White tiles represent features that are completely missing.

Predictive performance within individual hospital site-system

We evaluated AUROC, average precision, flag rate, and 24-h ileus for GRU-D and competing models trained independently on each of the four hospital site-systems. The daily performances from the index date to 10 days post-surgery are shown in Supplementary Data 1. We made three major observations. First, GRU-D models consistently achieved the best performance 4–5 days post-surgery on all benchmark metrics across all site-systems. Specifically, GRU-D models were able to decrease flag rate to ~30% by the 4th day post-surgery, remarkably outperforming competing models. Moreover, in two sites with EPIC system (MFep, MAep), GRU-D excelled in detecting 24-h ileus throughout the whole follow-up period, with continuous improvement in both AUROC and flag rate over time. Second, Logit models show superior performance in the Rochester site (MRcc, MRep) from the index date to 3–4 days post-surgery. However, the performance declined after 5 days and faced convergence issues when ileus cases were limited. Third, RF models exhibited strong performance at specific time points on certain datasets but were inconsistent overall. Performance peaks were not sustained across varying conditions, highlighting limited generalizability.

Transferability of GRU-D across hospital sites and EHR systems

In this section, we demonstrate the transferability of GRU-D using two approaches: last-timestep analysis and real-time surveillance. The former primarily serves as a benchmark strategy by assessing model transferability under ideal conditions where the model utilizes all available information up to ileus onset or the end of follow-up. The latter emphasizes the model’s performance in real-world postoperative surveillance.

GRU-D transferability based on last-timestep analysis

Through the last-timestep approach, we assessed multi-source instance transfer, single-source instance transfer, parameter transfer, and brute-force transfer against local learning across the four site-systems, leading to the following observations.

Multi-source instance transfer with data source indicator has overall the best performance (Tables 3–5ALL (w)ds). The improvement in AUROClast over local learning ranges from a minimum of 0.4% (Table 3MRep 0.935 vs ALL (w)ds 0.939) and a maximum of 2.6% (Table 4MFep 0.883 vs ALL (w)ds 0.906). Multi-source instance transfer remarkably reduces CI width. For example, for the EPIC site (MFep) with the smallest training sample size (Table 2, n = 226), the CI of AUROClast reduced 86%, from 0.042 on local learning to 0.006 (Table 4). Similarly, the CI of AvgPreclast reduced 56% from 0.071 on local learning to 0.031.

Table 3.

Centricity to EPIC transferability within Mayo Rochester (MR) site

| Training Source data () | MRcca | MRepb | MRcc + MRep (w/o)dsc | MRcc + MRep (w)dsd | MRep (MRcc)e | MRcc (MRep)f | ALL (w/o)ds | ALL (w)ds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target data ()g | AUROClast | 0.882, 0.022 | 0.935, 0.006 | 0.925, 0.01 | 0.929, 0.002 | 0.929, 0.013 | 0.907, 0.014 | 0.935, 0.006 | 0.939, 0.003 |

| AvgPreclast | 0.601, 0.056 | 0.704, 0.038 | 0.683, 0.028 | 0.707, 0.024 | 0.691, 0.040 | 0.642, 0.035 | 0.709, 0.032 | 0.72, 0.028 | |

| F-scorelast | 0.643, 0.047 | 0.73, 0.009 | 0.7, 0.023 | 0.709, 0.009 | 0.728, 0.022 | 0.679, 0.026 | 0.737, 0.014 | 0.736, 0.014 | |

| Target data () h | AUROClast’ | 0.886,0.009 | 0.888, 0.011 | 0.882, 0.018 | 0.883, 0.016 | 0.9, 0.009 | 0.89, 0.01 | 0.89, 0.012 | 0.893, 0.009 |

| AvgPreclast | 0.369, 0.016 | 0.395, 0.018 | 0.331, 0.043 | 0.358, 0.041 | 0.393, 0.018 | 0.342, 0.038 | 0.372, 0.024 | 0.366, 0.05 | |

| F-scorelast | 0.432, 0.014 | 0.463, 0.03 | 0.411, 0.048 | 0.428, 0.034 | 0.465, 0.031 | 0.403 0.032 | 0.446, 0.033 | 0.438, 0.032 |

Bold fonts indicate the best performing model.

Italic fonts represent training source and target data.

Data shown as metric, error margin of 95% CI (n = 1079, 747 independent surgery records for , , respectively).

aMayo Rochester Centricity system.

bMayo Rochester EPIC system.

cInstance transfer without data source indicator.

dInstance transfer with data source indicator.

eParameter transfer from Centricity to EPIC.

fParameter transfer from EPIC to Centricity.

gTarget dataset is the held-out data from Mayo Rochester EPIC system.

hTarget dataset is the held-out data from Mayo Rochester Centricity system.

Table 5.

EPIC transferability from Mayo Rochester (MR) to Mayo Arizona (MA) site

| Training Source data (STr) | MR a | MAb | MR + MA (w/o)dsc | MR + MA (w)dsd | MA(MR)e | ALL (w/o)ds | ALL (w)ds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target data () f | AUROClast | 0.889, 0.013 | 0.894, 0.013 | 0.896, 0.011 | 0.894, 0.01 | 0.896, 0.005 | 0.903, 0.006 | 0.911, 0.009 |

| AvgPreclast | 0.624, 0.017 | 0.657, 0.022 | 0.650, 0.048 | 0.67, 0.029 | 0.646, 0.023 | 0.692, 0.02 | 0.675, 0.024 | |

| F-scorelast | 0.726, 0.027 | 0.723, 0.013 | 0.708, 0.018 | 0.726, 0.019 | 0.722, 0.034 | 0.726, 0.019 | 0.716, 0.02 |

Bold fonts indicate the best performing model.

Italic fonts represent training source and target data.

Data shown as metric, error margin of 95% CI (n = 278 independent surgery records).

aMayo Rochester EPIC system.

bMayo Arizona EPIC system.

cInstance transfer without data source indicator.

dInstance transfer with data source indicator.

eParameter transfer.

fTarget dataset is the held-out data from Mayo Arizona EPIC system.

Table 4.

EPIC transferability from Mayo Rochester (MR) to Mayo Florida (MF) site

| Training Source data (STr) | MRa | MFb | MR + MF (w/o)dsc | MR + MF (w)dsd | MF(MR)e | ALL (w/o)ds | ALL (w)ds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target data () f | AUROClast | 0.904, 0.007 | 0.883, 0.042 | 0.903, 0.005, | 0.899, 0.01 | 0.906, 0.009 | 0.895, 0.01 | 0.906, 0.006 |

| AvgPreclast | 0.652, 0.026 | 0.652, 0.071 | 0.635, 0.015 | 0.668, 0.032 | 0.657, 0.024 | 0.648, 0.045 | 0.691, 0.031 | |

| F-scorelast | 0.804, 0.022 | 0.745, 0.064 | 0.813, 0.014 | 0.777, 0.022 | 0.807, 0.02 | 0.792, 0.033 | 0.815, 0.015 |

Bold fonts indicate the best performing model.

Italic fonts represent training source and target data.

Data shown as metric, error margin of 95% CI (n = 97 independent surgery records).

aMayo Rochester EPIC system.

bMayo Florida EPIC system.

cInstance transfer without data source indicator.

dInstance transfer with data source indicator.

eParameter transfer.

fTarget dataset is the held-out data from Mayo Florida EPIC system.

Parameter and instance transfer perform similarly. For models trained on only two data sources, parameter transfers (Table 3MRep(MRcc), Table 4MFep(MRep), Table 5MAep(MRep)) perform similarly as their single-source instance transfer counterparts, regardless of data source indicator (e.g., Table 3MRcc + MRep (w)(w/o)ds). The major benefit over local learning was seeing for the EPIC site (MFep) with a small training sample size (Table 4).

Brute-force transfer outperforms local learning in specific scenarios. Among all brute-force transfers, we see up to 5% decrease in AUROClast (Table 2MRep source to MRep target (0.935) vs MRcc target (0.888)). Whereas the performance of AvgPreclast and F-scorelast depends predominantly on the target dataset (Table 2MRep source to MRep target (AvgPreclast 0.704) vs MRcc target (AvgPreclast 0.395)). While brute-force transfer is poorer than instance or parameter transfer under most circumstances (Tables 3–5), it outperforms local learning in scenarios including (1) the outcome prevalence in the local dataset is low. For example, models trained with MRep training data have significantly better AvgPreclast (0.395) and F-scorelast (0.463) in predicting MRcc target than MRcc local learning (Table 4 AvgPreclast 0.369, CI(0.353,0.385); F-scorelast 0.432, CI(0.418,0.446)). (2) The local dataset has a small sample size. For example, models trained with MRep training data have higher AUROClast and F-scorelast and remarkably narrower CI width than MFep local learning (Table 4MRep vs MFep on MFep target).

Negative transfer was only observed when transfer from Centricity to EPIC system (Table 3MRcc + MRep, MRep(MRcc) vs MRep on MRep target). Compared to local learning with EPIC data only, the performance of AUROClast, AvgPreclast, and F-scorelast decreased remarkably after incorporating training data from the Centricity system, regardless of transferring strategy. On the other hand, no notable negative transfer was observed when transfer from EPIC to Centricity (Table 3MRcc + MRep vs MRcc on MRcc target) or from EPIC to EPIC (Tables 4 and 5).

Instance or parameter transfer between hospital sites both using the EPIC system generally brings marginal improvement over local learnings (Tables 4 and 5).

GRU-D transferability on real-time surveillance

Being a dynamic time series model, GRU-D inherently provides risk predictions at each timestep during the follow-up period. Hence, evaluating the model’s transferability at the timestep level is essential. Here we made the following major observations.

Multi-source instance transfer outperformed local learning in AUROC, average precision, flag rate, and 24-h ileus prediction across all three EPIC systems (Figs. 3–5), both before and after the index date, with statistically significant improvements observed at multiple continuous follow-up time points. Additionally, it showed marginally better performance compared to single-source instance transfer and parameter transfer (Supplementary Figs. 2–4), although the differences were less pronounced.

Fig. 4. Multi-source instance transfer versus local learning on predicting MFep held-out.

ALL w(ds): train models on with data source indicator; Local: train models on . Solid and hollow purple circles represent GRU-D models. Solid and hollow blue triangles represent Logit models. Solid green circles represent the overall number of remaining cases. Hollow green circles represent the cases that occurred in the next 24 h. Error bars represent 95% CI obtained from six-fold models. n = 97 independent surgery records. Flag rate the lower the better. MFep Mayo Florida EPIC system.

Fig. 3. Multi-source instance transfer versus local learning on predicting MRep held-out.

ALL w(ds): train models on with data source indicator; Local: train models on . Solid and hollow purple circles represent GRU-D models. Solid and hollow blue triangles represent Logit models. Solid green circles represent the overall number of remaining cases. Hollow green circles represent the cases that occurred in the next 24 h. Error bars represent 95% CI obtained from six-fold models. n = 747 independent surgery records. Flag rate the lower the better. MRep Mayo Rochester EPIC system.

Fig. 5. Multi-source instance transfer versus local learning on predicting MAep held-out.

ALL w(ds): train models on with data source indicator; Local: train models on . Solid and hollow purple circles represent GRU-D models. Solid and hollow blue triangles represent Logit models. Solid green circles represent the overall number of remaining cases. Hollow green circles represent the cases that occurred in the next 24 h. Error bars represent 95% CI obtained from six-fold models. n = 278 independent surgery records. Flag rate the lower the better. MAep Mayo Arizona EPIC system.

Brute-force transfer is generally suboptimal for transfers between Centricity and EPIC after the index date (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, brute-force transfers from the large-sample-size EPIC site (MRep) typically outperform local learning at EPIC sites (MFep, MAep) that have smaller sample sizes (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7).

With only two data sources, parameter transfer achieves performance nearly identical to single-source instance transfer (Supplementary Figs. 2–4) throughout the follow-up period, while being less demanding on GPU memory usage.

The model performance is predominantly determined by the prediction task, whereas the training data plays a very limited role. This is evident from the observation that when the models trained with Centricity training data (MRcc) are brute-force transferred to EPIC target (MRep), they exhibit significantly better performance than being applied locally (i.e., to MRcc target) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The marginal improvements in traditional metrics such as AUROC, precision, and F1-score may have a less pronounced impact on clinically oriented metrics like 24-h ileus prediction, which exhibit relatively minor fluctuations across different learning strategies.

Transferability of atemporal models

We assessed the transferability of Logit and RF models in multi-source instance transfer, single-source instance transfer, and brute-force transfer compared to local learning. In comparison to GRU-D models, they exhibit the following transferability characteristics. First, both Logit and RF models benefit from multi-source or single-source instance transfer, but these improvements are inconsistent across different follow-up time points. For example, at one EPIC site (MAep), Logit models with multi-source instance transfer performed significantly worse 2–3 days post-index date compared to local learning but showed no such disadvantage at other time points (Fig. 5). Second, both Logit and RF models are less suitable for brute-force transfer across hospital sites and EHR systems compared to GRU-D models. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8, brute-force transfer using Logit models from Centricity to EPIC results in a notable performance drop after the index date. Finally, RF models exhibit similar characteristics to Logit models but display slightly less variability across follow-up time points (Supplementary Figs. 9–11).

Model explainability

Explainability of GRU-D models

To investigate the explainability of GRU-D models in local learning settings and the impact of transfer learning on explainability, we conducted permutation feature importance tests on selected scenarios described below. For transfers between Centricity and EPIC systems within a single hospital site (i.e., MRcc and MRep), we examined two scenarios: brute-force transfer (Scenario a, Supplementary Fig. 12a) and instance transfer (Scenario b, Supplementary Fig. 12b). Similarly, for transfers between hospital sites both using the EPIC system (i.e., MRep and MAep), we analyzed two scenarios: brute-force transfer (Scenario c, Supplementary Fig. 13a) and instance transfer (Scenario d, Supplementary Fig. 13b).

In all scenarios, we identified a generally consistent set of features with top significance, including surgery duration, pain location, pain score, pulse rate, dressing type, skin condition, and surgery type. Comparing Scenarios a and b, as well as Scenarios c and d, revealed that the target dataset, rather than the transfer learning strategy, plays a pivotal role in determining the importance of input features. For instance, within the same target dataset, the feature importance patterns of cross-EHR system brute-force transfer (Supplementary Fig. 12a) and instance transfer (Supplementary Fig. 12b) are strikingly similar. A similar observation was made when transferring EPIC system data between hospital sites (Supplementary Fig. 13a vs. 13b), demonstrating robust transferability in the explainability of GRU-D models.

On the other hand, different target datasets can yield different importance patterns on certain features, even when using the same model. For example, in Scenario a (Supplementary Fig. 12a), features such as dressing type, urine status, and skin condition exhibit varying levels of importance between the two target datasets (MRcc and MRep). This suggests that the contributions of input features to ileus outcomes are dataset-specific.

Explainability of Logit models

We analyzed the regression coefficients of Logit models across the follow-up period. In both local learning and instance transfer settings, the overall direction and relative magnitude of the top contributing factors remained generally stable. Notably, there is a transition in the primary contributing factors over time. For example, key factors such as surgery type, hospital site, ileus medication, and smoking status were most influential 4, 3, and 2 days before the index date. This focus shifted to skin condition and surgery type 1 day before the index date, and further transitioned to pain location, dressing type, assisted living status, urine condition, and muscle color on and after the index date (i.e., immediately following surgery).

ICD diagnosis date versus ICD post date

In clinical practice, there is often a delay of 1–4 days before the ICD diagnosis date becomes available in the EHR system. As a result, the ICD post date is more readily accessible for integration into risk models. To evaluate the impact, we trained models using multi-source instance transfer and incorporated dynamic ICD diagnosis date, dynamic ICD post date, and static ICD post date (i.e., use whatever ICD code available 4 days before surgery and replicated through follow-up) as predictors for predicting the held-out data from all sites. In our analysis, we found no notable performance differences during the first 8 days post-surgery; however, beyond this period, the dynamic ICD diagnosis date showed a slight advantage over the other two date types in terms of AUROC and flag rate (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Discussion

Over the past decade, extensive research has revolved around the integration of AI into healthcare, but only a handful of AI tools have undergone thorough validation, and even fewer have been put into clinical practice23–26. An important part of this challenge lies in the lack of clinical utility and transferability research with large scale clinical data. Here we demonstrated GRU-D’s capability for dynamic postoperative ileus risk modeling at multiple time points of follow-up in separate hospital sites and different EHR systems. We further provided compelling evidence of GRU-D’s robust transferability across hospital sites and EHR systems, which is generally superior to competing atemporal models. Our findings align with the transferability of RNN-based RETAIN models in predicting heart failure across hospitals27, which however, only reported static risk prediction. These outcomes support the potential applicability of such models in improving clinical predictive tasks across diverse healthcare environments.

Evaluating the clinical utility of GRU-D is essential for understanding its impact on patient care and clinical workflows. In this context, the flag rate, representing the proportion of patients to be monitored to cover 60% of all remaining ileus cases, and the ability to detect ileus in the next 24 h provide intuitive benchmarks for assessing whether healthcare resources are being utilized efficiently. While on the index date no model dominates across all site-systems. GRU-D noticeably excels in flag rate and 24-h ileus detection by the 4th day post-surgery—corresponding to the typical hospital stay covered by most insurance plans. These findings indicate that GRU-D provides a distinct advantage over atemporal models, especially in the post-insurance period, by prioritizing patients for additional monitoring prior to discharge. This is particularly valuable given the current reliance on clinician judgment as the primary method for preventing the premature discharge of at-risk patients. Furthermore, GRU-D may help mitigate the influence of non-clinical factors, such as insurance type28–30, on postoperative length of stay. Integrating GRU-D into continuous postoperative surveillance, along with efficiently allocated healthcare resources such as nursing, staffing, and medical devices, has the potential to improve monitoring effectiveness and reduce the burden on hospital wards.

We note feature sparsity as a major challenge for transferability of time series models for several reasons. (1) Hospitals may vary in their documentation of surgery-related features depending on equipment, regulations, and EHR configurations. (2) Some features—like PEEP, peak inspiratory pressure, fraction of inspired oxygen, and heart rate—are typically recorded during surgery and are only documented post-surgery under specific conditions (e.g., when additional patient care is needed). (3) Other features, such as fall risk, Braden score, and many lab tests, are recorded at periodic but inconsistent intervals, making it challenging to maintain uniform data. Consequently, excluding features due to absence in certain sites or treating conditionally recorded features as static may undermine model generalizability. GRU-D demonstrates strength in this real-world scenario, handling variable data availability effectively and minimizing the need for extensive feature engineering that undermines transferability of time series models.

Despite the extreme sparsity in the input feature space, brute-force transfer maintained remarkably consistent performance across EHR systems and hospital sites, with reasonable stability in the explanation of feature importance. This leads to two insights: (1) The ground truth behind input features, informative missing, and ileus outcome is embedded within each local dataset, which the GRU-D architecture has managed to capture to a certain degree. (2) The contribution of each feature to the outcome is dataset-specific and less relevant to the model training process. Whereas the minor variations in how the model explains certain features suggest that incorporating data from other instances enables the model to find a more effective pathway to predict outcomes.

In essence, instance or parameter transfers offer a relatively slight advantage over local learning or brute-force transfer on improving evaluation metrics. However, they notably outperform in terms of reducing CI width, particularly when training data is extremely limited. This leads to predictions that are more precise and therefore more confident for supporting interventions. Furthermore, these findings underscore the ability of GRU-D to effectively handle small datasets with remarkably sparse features. They also imply that for hospitals with restricted patient access, employing multi-fold cross-validation and averaging the results presents a feasible strategy for applying GRU-D in post-operative surveillance, despite greater variance.

In light of the widespread transition to the EPIC system among hospital systems nationwide31,32, we evaluated the transferability from Centricity to EPIC to determine whether incorporating historical data could enhance predictive performance. In both instance and parameter transfer learning approaches, we observed mild negative transfer when integrating Centricity data into EPIC data, but not vice versa. This outcome may be attributed to: (1) differences in feature distribution caused by the non-overlapping colorectal surgery periods, and (2) variations in how data is recorded across EHR systems, with Centricity exhibiting notably more lab measurements but fewer vital signs compared to EPIC. These findings highlight the challenges of leveraging historical data from different EHR platforms, which may require careful consideration of data compatibility and system-specific characteristics in predictive modeling.

Experiments of mutual brutal transfer between the Centricity and EPIC systems reveal that the model performance is primarily influenced by the difficulty of the prediction task, specifically the case prevalence, despite our efforts to address case imbalance through inverse weighting. In contrast, the contribution of the training data and transferring strategy is comparatively less important. It is anticipatable that for cohorts with extremely rare cases, even the implementation of intricately designed transferring approaches may result in limited improvements in performance. This highlights the challenge of effectively leveraging transfer learning in situations where the target task involves highly uncommon outcomes.

Aligned with our previous findings on superficial infections and bleeding12, Logit and RF models excel at specific moments before or immediately after the index date. Intriguingly, during most of the postoperative hours, when more current measurements are available, their advantage does not persist and instead exhibits a high level of instability. This counterintuitive performance leads to the following hypotheses: (1) The relatively simple logical structure of static models is insufficient to handle the complexity of features in postoperative hours. (2) Temporal information plays a crucial role in determining outcomes, which is not captured by static models. (3) The healthcare system’s reliance on a similar static modeling strategy for triggering complication alerts (e.g., bleeding determined algorithmically through hemoglobin levels) may influence results. Despite these observations, we do not dismiss the potential superiority of static models under certain conditions. However, the feasibility of constructing and managing multiple static models deserves further discussion if dynamic risk update is a crucial component.

In conclusion, the GRU-D based longitudinal deep learning architecture demonstrated robust transferability across different EHR systems and hospital sites, even with the highly sparse input feature space typical of real-world EHR data. Its ability to update risk assessments by incorporating new measurements makes GRU-D particularly useful in scenarios where clinical follow-up is crucial. Further research on enhancing built-in explainability for meaningful intervention is essential and highly valuable for its integration into clinical practice.

In this study, we focused on transferability across EHR systems and hospital sites, but did not evaluate data inequality or distribution differences among racial/ethnic minorities and underserved groups. Our previous studies20,33 showed that EHR systems significantly affect the structure and format of clinical data due to built-in documentation features like templates, copy-paste, auto-documentation, and transcription. Changes in clinical and billing practices further contribute to this heterogeneity. For postoperative complications (e.g., abscess, anemia, wound infection), we observed high syntactic variation and moderate differences in semantic type and frequency across document sections20. Similar patterns may affect ileus documentation, especially after EPIC migration. A follow-up study is needed to examine this and ensure data quality and transparency.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering grant (R01 EB019403) and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Established Investigator Award (RR230020).

Author contributions

X.R.: Data analysis, manuscript writing. S.F.: NLP-related analysis. H.J. and K.M.: Chart review. K.M. and C.T.: Expert opinion from a clinician’s perspective. S.G. and P.W.: Data curation. C.S. and H.L.: Expert opinion on cohort selection and data analysis, project coordination.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks George Ramsay and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The data used in this study contain sensitive patient information and, therefore, are not publicly available. Access to the data is restricted to protect patient privacy and confidentiality. Researchers interested in accessing the data for academic purposes may contact the corresponding author for more information on the terms and conditions for data access. The source data for Figs. 2–5 and S1–S14 is available in Github: (https://github.com/ruanxiaoyang-UT/ileus-figures-source-data).

Code availability

The code for GRU-D model is publicly available at https://github.com/PeterChe1990/GRU-D.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-025-01053-9.

References

- 1.Harnsberger, C. R., Maykel, J. A. & Alavi, K. Postoperative Ileus. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg.32, 166–170 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venara, A. et al. Postoperative ileus: pathophysiology, incidence, and prevention. J. Visc. Surg.153, 439–446 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shariq, O. A. et al. Performance of general surgical procedures in outpatient settings before and after onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open6, e231198 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenna, N. P. et al. Is same-day and next-day discharge after laparoscopic colectomy reasonable in select patients? Dis. Colon Rectum63, 1427–1435 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckey, A., Livingston, E. & Taché, Y. Mechanisms and treatment of postoperative ileus. Arch. Surg.138, 206–214 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin, Z., Li, Y., Wu, J., Zheng, H. & Yang, C. Nomogram for prediction of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal resection. BMC Cancer22, 1–11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garfinkle, R. et al. Prediction model and web-based risk calculator for postoperative ileus after loop ileostomy closure. Br. J. Surg.106, 1676–1684 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugawara, K. et al. Perioperative factors predicting prolonged postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery. J. Gastrointest. Surg.22, 508–515 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rencuzogullari, A., Benlice, C., Costedio, M., Remzi, F. H. & Gorgun, E. Nomogram-derived prediction of postoperative ileus after colectomy: an assessment from nationwide procedure-targeted cohort. Am. Surg.10.1177/000313481708300620 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, D.-D. et al. Prediction of prolonged postoperative ileus after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a scoring system obtained from a prospective study. Medicine94, e2242 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvind, V., Kim, J. S., Oermann, E. K., Kaji, D. & Cho, S. K. Predicting surgical complications in adult patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion using machine learning. Neurospine15, 329–337 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruan, X. et al. Real-time risk prediction of colorectal surgery-related post-surgical complications using GRU-D model. J. Biomed. Inform.135, 104202 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer, A. et al. Machine learning for real-time prediction of complications in critical care: a retrospective study. Lancet Respir. Med.6, 905–914 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Che, Z., Purushotham, S., Cho, K., Sontag, D. & Liu, Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Sci. Rep.8, 6085 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebbehoj, A., Thunbo, M. Ø, Andersen, O. E., Glindtvad, M. V. & Hulman, A. Transfer learning for non-image data in clinical research: a scoping review. PLOS Digit. Health1, e0000014 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber, M., Auch, M., Doblander, C., Mandl, P. & Jacobsen, H.-A. Transfer learning with time series data: a systematic mapping study. IEEE Access9, 165409–165432 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, H., Lundberg, S. M., Erion, G., Kim, J. H. & Lee, S.-I. Forecasting adverse surgical events using self-supervised transfer learning for physiological signals. npj Digit. Med.4, 167 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birkmeyer, J. D. et al. Blueprint for a new American College of Surgeons: national surgical quality improvement program. J. Am. Coll. Surg.207, 777–782 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen, A. et al. Desiderata for delivering NLP to accelerate healthcare AI advancement and a Mayo Clinic NLP-as-a-service implementation. npj Digit. Med.2, 1–7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu, S. et al. Assessment of data quality variability across two EHR systems through a case study of post-surgical complications. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl. Sci. Proc.2022, 196–205 (2022). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson, A. Transfer Learning with Time Series Prediction: Review (2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4214809.

- 22.Ishwaran, H., Kogalur, U. B., Blackstone, E. H. & Lauer, M. S. Random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat.2, 841–860 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajwa, J., Munir, U., Nori, A. & Williams, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc. J.8, e188–e194 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med.25, 44–56 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly, C. J., Karthikesalingam, A., Suleyman, M., Corrado, G. & King, D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med.17, 195 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panch, T., Mattie, H. & Celi, L. A. The ‘inconvenient truth’ about AI in healthcare. npj Digit. Med.2, 77 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmy, L. et al. A study of generalizability of recurrent neural network-based predictive models for heart failure onset risk using a large and heterogeneous EHR data set. J. Biomed. Inform.84, 11–16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Englum, B. R. et al. Association between insurance status and hospital length of stay following trauma. Am. Surg.82, 281–288 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dosselman, L. J. et al. Impact of insurance provider on postoperative hospital length of stay after spine surgery. World Neurosurg.156, e351–e358 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon, R. C. et al. Association of insurance type with inpatient surgery 30-day complications and costs. J. Surg. Res.282, 22–33 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chishtie, J. et al. Use of epic electronic health record system for health care research: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res.25, e51003 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmgren, A. J. & Apathy, N. C. Trends in US Hospital Electronic Health Record Vendor Market Concentration, 2012-2021. J. Gen. Intern. Med.38, 1765–1767 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu, S. et al. Assessment of the impact of EHR heterogeneity for clinical research through a case study of silent brain infarction. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak.20, 60 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study contain sensitive patient information and, therefore, are not publicly available. Access to the data is restricted to protect patient privacy and confidentiality. Researchers interested in accessing the data for academic purposes may contact the corresponding author for more information on the terms and conditions for data access. The source data for Figs. 2–5 and S1–S14 is available in Github: (https://github.com/ruanxiaoyang-UT/ileus-figures-source-data).

The code for GRU-D model is publicly available at https://github.com/PeterChe1990/GRU-D.