Abstract

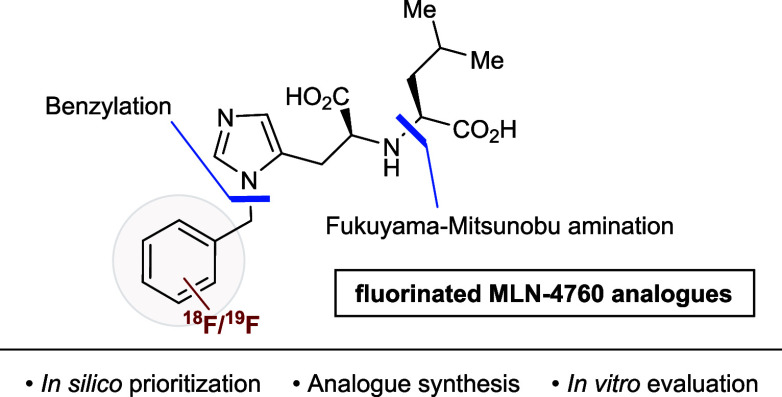

The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is pivotal as the cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus responsible for COVID-19. This study presents a novel synthetic route for four analogues of MLN-4760, a known inhibitor of ACE2, guided by in silico docking predictions. These synthetic advances enabled in vitro pIC50 assays confirming the inhibitory potency of the synthesized analogues. Lastly, this route was applied to the synthesis of novel 18F-labeled ACE2 inhibitors for PET imaging applications.

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic due to the rapid global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), resulting in a significant global health and economic crisis. SARS-CoV-2 infects host cells by binding of the spike protein to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a zinc–metalloprotease expressed in various organs, including the lungs, heart, kidneys, and intestines. ACE2 is considered a potential biomarker for disease progression and severity in COVID-19, but the extent to which its expression level relates to infection remains unclear. Clinical studies on hospitalized patients have suggested a positive correlation between plasma ACE2 levels and the severity of COVID-19 infection, while ACE2 deficiency may also worsen long COVID-19 symptoms, especially in patients with underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease.

Current ACE2 detection methods include immunohistochemistry and serological testing, but these do not allow for dynamic visualization and assessment of ACE2 biodistribution. Molecular imaging, particularly noninvasive positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, offers a high-sensitivity alternative to quantitatively monitor ACE2 expression. Various studies have illustrated the value of PET imaging with ACE2 radiotracers prepared by derivatization of the ACE2-targeting peptide DX600 with radiometal chelators, including [67Ga]HBED-CC-DX600, [68Ga]NOTA-PEP4, [68Ga]HZ20, [64Cu]HZ20, and [18F]AlF-DX600-BCH (Figure A). These tracers display significant accumulation in ACE2-expressing tissues, and attenuation of signal in organs affected by COVID-19. High uptake in tissues such as the nasal mucosa and kidneys were observed, contrasting to lower accumulation of radiotracer in the lungs and heart, in line with known ACE2 expression patterns. ,

1.

(A) Peptide-derived ACE2 PET radiotracers. (B) Established synthesis of MLN-4760. (C) Synthesis of diversified fluorinated MLN-4760 analogues (this work).

Despite these advances, the development of new-generation radiotracers with improved properties, such as higher affinity for the ACE2 receptor (IC50(DX600) = 113.6 nM) as well as reduced bone uptake, remains highly desirable. With the aim to develop a novel ACE2 PET radiotracer, analogues of the potent small molecule ACE2 inhibitor MLN-4760 ((S,S)-2-(1-carboxy-2-(3-(3,5-dichlorobenzyl)-3H-imidazol-4-yl)-ethylamino)-4-methylpentanoic acid) (IC50 = 0.44 nM) were selected as possible candidates for investigation (Figure B). The original synthesis of MLN-4760 reported by Dales et al. proved suboptimal for radiotracer design. First, the early stage installation of a benzyl group, which is an ideal site for radiolabeling with the PET radioisotopes of fluorine-18 or carbon-11, would demand a multistep synthesis of precursors and reference standards for every candidate radiotracer under consideration. This imposes a significant bottleneck in the tracer discovery process, where multiple labeling strategies are envisaged, requiring the synthesis of multiple classes of labeling precursors. Furthermore, an unselective reductive amination step requires preparative HPLC separation and purification of diastereomers. With these challenges in mind, our aim was to develop a novel divergent route to analogues of MLN-4760 to inform future ACE2 radiotracer development (Figure C).

To begin our studies, we formulated a set of 31 potential analogues of MLN-4760 for initial in silico evaluation (Figure S1.3). Such screening would guide our selection of the identity and position of the radiolabel (fluorine-18 or carbon-11), and allow us to prioritize the synthesis of a subset of analogues for in vitro studies. Computational docking and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) methods were employed sequentially to predict binding affinity changes and pIC50 values for each candidate. After validation of the docking model using literature pIC50 data for MLN-4760 analogues with an ACE2 crystal structure (PDB 1R4L), 14 fluorinated analogues were carried forward for RBFE analysis, which better accounts for interactions and dynamic processes (Table S1.2). Applying this protocol to these 14 compounds yielded predicted pIC50 values, which were corrected using linear regression between the known and experimentally determined pIC50 for MLN-4760 analogues. This enabled us to shortlist four fluorinated candidates for synthesis (Figure ). With this information in hand, we next focused our attention on the synthesis of these four MLN-4760 analogues (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4, selecting the 4-fluorobenzyl analogue (S,S)-1 as the representative model compound.

2.

Structural analogues of MLN-4760 ((S,S)-1–(S,S)-4) selected as potential ACE2 inhibitors and their predicted IC50 values.

Early attempts applied the original synthetic method for MLN-4760 disclosed by Dales et al.; in our hands, the key reductive amination step delivered a low yield of the desired product (31%) (Table S2.1). Additionally, the process resulted in a mixture of diastereomers (57:43 d.r., determined by 1H NMR), which required separation by silica gel column chromatography and preparative HPLC to isolate (S,S)-1 in sufficient purity (Scheme S2.1). These difficulties prompted us to modify the synthesis. With the aim to improve the yield and stereoselectivity of the key C–N bond forming step, we opted for the Fukuyama-Mitsunobu reaction based on its well-documented stereospecific SN2 mechanism. Furthermore, we envisaged that resequencing the amination and benzylation steps would facilitate analogue generation from a single common intermediate via late-stage benzylation, thus reducing synthetic burden and expediting access to analogues (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4.

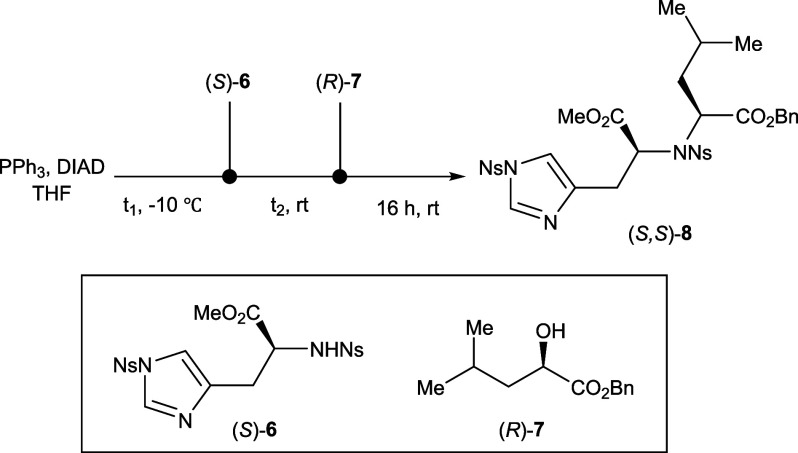

A synthesis of (S,S)-1 with a route featuring a key Fukuyama-Mitsunobu amination was therefore initiated (Scheme ). Starting with the histidine derivative (S)-5, 2-nitrobenzenesulfonyl (Ns) groups were first installed at both the N1-position and primary amine with 2-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (NsCl) in the presence of triethylamine in dichloromethane, affording doubly Ns-protected intermediate (S)-6 in 76% yield. The Ns group served as a protecting and activating group for the Fukuyama-Mitsunobu amination. This reaction, involving the di-Ns-protected histidine derivative (S)-6 and benzyl (R)-2-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoate ((R)-7), was carefully optimized with key reaction parameters investigated (Table ). Preliminary investigation demonstrated that diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD) as an activator in THF at room temperature could be effective (Scheme S2.2). Optimization of both the number of equivalents of (R)-7 and the time at which each reagent is added revealed that sequential addition of (S)-6 and (R)-7 to a stirred mixture of DIAD and PPh3 in THF after a delay of 1 and 2 h, respectively, led to the highest yields of (S,S)-8 (Table , entry 6). The Fukuyama-Mitsunobu amination was thus performed under these optimized conditions, resulting in the formation of the histidine-leucine derivative (S,S)-8 with a 55% yield and >20:1 d.r. (determined by 1H NMR) for the desired diastereomer (Scheme b). Subsequent benzylation of (S,S)-di-Ns-protected 8 did not yield the desired product, likely due to the presence of the electron-withdrawing Ns group (Scheme S2.3). The Ns groups were therefore cleaved using thiophenol (PhSH), successfully producing the histidine-leucine derivative (S,S)-9 in 70% yield (Scheme c). In advance of N3-benzylation and to avoid formation of the undesired N1-regioisomer, Boc groups were installed at the N1-position of the imidazole and at the Leu-derived secondary amine (Scheme d). This crude material was carried forward for benzylation with 4-fluorobenzyl alcohol (10) in the presence of trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride. Subsequent in situ one-pot deprotection of the Boc groups with HCl yielded (S,S)-11 in 43% yield and >20:1 d.r. (determined by 1H NMR) (Scheme e). Basic hydrolysis with NaOH finally yielded (S,S)-1 in 48% yield (Scheme f).

1. Synthesis of Fluorinated MLN-4760 Analogues (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4 .

a Reagents and conditions: (a) Et3N (3.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h, then NsCl (2.2 equiv), rt, 18 h, 76%; (b) PPh3 (1.0 equiv), DIAD (1.0 equiv), THF, −10 °C, 1 h, then (S)-6 (1.5 equiv), THF, rt, 2 h, then (R)-7 (1.0 equiv), THF, rt, 16 h, 55%, >20:1 d.r.; (c) PhSH (2.2 equiv), K2CO3 (3.0 equiv), DMF, rt, 1 h, 70%, >20:1 d.r.; (d) (S,S)-9 (1.1 equiv), Boc2O (2.2 equiv), DIPEA (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h, isolated as crude, then (e) (CF3SO2)2O (1.0 equiv), 10, 12–14 (1.0 equiv), DIPEA (1.5 equiv), −78 °C to rt, 24 h, then HCl (4.0 M in dioxane, 1.1 equiv), rt, 1 h, (S,S)-11 (43%, >20:1 d.r.), (S,S)-15 (47%, >20:1 d.r.), (S,S)-16 (46%, >20:1 d.r.), (S,S)-17 (41%, >20:1 d.r.); (f) NaOH (3.0 equiv), MeOH/H2O, rt, 1 h, work up with HCl (1 M), rt, 30 min, then preparative HPLC purification, (S,S)-1 (48%), (S,S)-2 (44%), (S,S)-3 (44%), (S,S)-4 (49%).

1. Optimization of the Fukuyama–Mitsunobu Amination .

| entry | ( S )-6 loading | t 1 / h | t 2 / h | yield of ( S , S )-8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 equiv | 0 | 0 | traces |

| 2 | 1.0 equiv | 0 | 1 | 12% |

| 3 | 1.0 equiv | 0 | 2 | 21% |

| 4 | 1.0 equiv | 1 | 2 | 35% |

| 5 | 1.5 equiv | 0 | 2 | 42% |

| 6 | 1.5 equiv | 1 | 2 | 55% |

PPh3 = 1.0 equiv, DIAD = 1.0 equiv, (R)-7 = 1.0 equiv.

Yields determined by quantitative 19F NMR spectroscopy with 4-fluoroanisole as internal standard.

To confirm the configuration of the product obtained via this new synthetic route, we compared NMR spectroscopic data for 1H, 19F and 13C nuclei and HPLC retention time for (S,S)-1 with previously synthesized (S,S)-1 (vide supra). These data were contrasted to that of diastereomer (S,R)-1, which was prepared applying the same route as (S,S)-1, using (S)-7 in place of (R)-7 in the Fukuyama-Mitsunobu amination. This allowed for verification of the structure and stereochemistry of (S,S)-1 (Figures S2.1–S2.5). The synthesis of MLN-4760 analogues (S,S)-2–(S,S)-4 was achieved using this new synthetic route (Scheme ). From common intermediate (S,S)-9, the tandem di-Boc-protection-benzylation step was carried out with fluorinated benzyl alcohols 12–14, providing intermediates (S,S)-15–(S,S)-17 in moderate yields (41–47%, >20:1 d.r, determined by 1H NMR). The final basic hydrolysis step (vide supra) yielded the desired analogues (S,S)-2–(S,S)-4 as pure diastereomers with yields ranging from 44–49%.

With PET imaging in mind, this synthetic route was also applied to the preparation of model pinacol boronic ester (S,S)-18 that we surmised could be a suitable precursor to (S,S)-[18F]1 applying copper-mediated radiofluorination. Starting from intermediate (S,S)-9, N3-selective benzylation with 4-bromobenzyl alcohol and subsequent Miyaura borylation provided (S,S)-18 (13% over two steps, >20:1 d.r.) (Scheme S2.4). Applying the protocol established in our laboratory for the copper-mediated 18F-fluorination of aryl pinacol boronic esters, , (S,S)-[18F]11 was successfully obtained in radiochemical yield (RCY) of 24% ± 7% (n = 2), as determined by radio-HPLC analysis of the crude reaction (Scheme A (i)). Subsequent basic hydrolysis of the ester protecting groups resulted in full conversion of (S,S)-[18F]11, and formation of (S,S)-[18F]1 (average RCY = 18%, over two steps) (Scheme A (ii)). The pinacol boronic ester precursor to (S,S)-[18F]3 was prepared analogously ((S,S)-19, Scheme S2.5). Subjecting this material to copper-mediated 18F-fluorination followed by in situ deprotection furnished (S,S)-[18F]3 in 8% RCY over two steps (Scheme B).

2. Radiolabeling of MLN-4760 Analogues (A) Radiosynthesis of (S,S)-[ 18 F]1; (B) Radiosynthesis of (S,S)-[ 18 F]3 .

a Radiochemical yields (RCY) determined by radio-HPLC analysis of crude reaction mixtures. Reagents and conditions: (i) (S,S)-18 (5 μmol) or (S,S)-19 (10 μmol), [18F]KF.K222 (5–20 MBq), Cu(OTf)2py4 (2 equiv), DMI (0.3 mL), purged with air (20 mL), then 120 °C, 20 min; RCY [(S,S)- [18F]11] = 24% ± 7% (n = 2), RCY [(S,S)- [18F]16] = 9% ± 3% (n = 2) (ii) NaOH (aq., 1 M, 0.1 mL), 65 °C, 20 min, then HCl (aq., 1 M, 0.1 mL); RCY [(S,S)- [18F]1] (over two steps) = 18% ± 8% (n = 2). RCY [(S,S)-[18F]3] (over two steps) = 8% ± 3% (n = 2).

Having validated our radiosynthetic approach to (S,S)-[18F]1 and with various fluorinated MLN-4760 analogues in hand, we next looked to evaluate the inhibitory activity of the analogues using a commercially available ACE2 inhibition assay kit (Table ) (Figure ). Due to differences in assay conditions compared to those used in the literature, the pIC50 of MLN-4760 was first remeasured, yielding a lower experimental pIC50 (pICexp 50) value of 8.19 compared to the reported literature value of 9.36. Consequently, the pIC50 values of the tested compounds were evaluated relative to our experimentally measured value for MLN-4760 in order to identify lead candidates for radiolabeling. In line with observations made for MLN-4760, the stereochemistry of the compounds significantly affected their inhibitory effects; compound (S,S)-1 (pICexp 50 = 6.69 ± 0.05) was indeed markedly more potent than (S,R)-1 (pICexp 50 = 4.39 ± 0.04) with a difference of 2 orders of magnitude, suggesting configuration-dependent binding between ACE2 and MLN-4760 analogues. 3,5-Disubstituted benzyl compounds (S,S)-2, (S,S)-3, and (S,S)-4 had pIC50 values similar to MLN-4760 (pICexp 50 = 7.54 ± 0.06) when subjected to the assay, with (S,S)-3 (pICexp 50 = 7.61 ± 0.09) being the most effective ACE2 inhibitor compared to para-substituted (S,S)-1. The difference between the in vitro pICexp 50 for MLN-4760 and the pICexp 50 values of (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4 aligned with the difference in the in silico predicted pIC50 (pICpr 50) of MLN-4760 and pICpr 50 values of (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4. Specifically, these pIC50 differences for all 3,5-disubstituted benzyl analogues (S,S)-2, (S,S)-3, and (S,S)-4 were smaller than for the para-substituted benzyl analogue (S,S)-1, providing support for the pICpr 50 values (Table ). Consequently, compounds (S,S)-2, (S,S)-3 and (S,S)-4, with pIC50 values in the same range as MLN-4760, emerge as priority targets for future ACE2 PET radioligand development.

2. In Vitro ACE2 Inhibition Study for MLN-4760 Analogues ((S,S)-1–(S,S)-4) and Comparison to In Silico Predictions .

| compound | pICpr 50 | pICpr‑MLN 50 – pICpr 50 | pICexp 50 | pICexp‑MLN 50 – pICexp 50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLN-4760 | 8.19 | 0.00 | 7.54 ± 0.06 | 0.00 |

| (S,S)-1 | 7.14 | 1.05 | 6.69 ± 0.05 | 0.85 |

| (S,R)-1 | n.d.i | n.d. | 4.39 ± 0.04 | 3.15 |

| (S,S)-2 | 7.94 | 0.25 | 7.18 ± 0.04 | 0.36 |

| (S,S)-3 | 7.99 | 0.20 | 7.61 ± 0.09 | –0.07 |

| (S,S)-4 | 8.88 | –0.69 | 7.27 ± 0.05 | 0.27 |

pIC50 determined using Abcam ACE2 inhibitor screening kit. n.d., not determined. pICpr 50, predicted pIC50, pICpr‑MLN 50, predicted MLN-4760 pIC50, pICexp 50, experimental pIC50, pICexp‑MLN 50, experimental MLN-4760 pIC50.

3.

Inhibitory activity of MLN-4760 and analogues (S,S)-1–(S,S)-4, (S,R)-1.

This work aimed toward the discovery of highly potent and selective candidates for ACE2 PET imaging - a biomarker implicated in various diseases, including COVID-19. First, in silico screening of a panel of analogues of lead compound MLN-4760 identified promising radiotracer candidates. This was followed by the development of a novel synthetic approach to these MLN-4760 analogues using para-fluorobenzyl containing model target (S,S)-1 and leveraging the Fukuyama-Mitsunobu reaction and late-stage benzylation as key steps. This approach offered improved yield and control over diastereoselectivity compared to existing synthetic routes, accelerating the synthesis of four fluorinated MLN-4760 analogues. The same route was applied to the preparation of model pinacol boronic ester precursor (S,S)-18, which was converted into (S,S)-[18F]1 upon copper-mediated radiofluorination. (S,S)-[18F]3 was prepared in the same way. Finally, evaluation of the potency of our collection of fluorinated MLN-4760 analogues via in vitro IC50 assays confirmed their ACE2 inhibitory activity. Compounds (S,S)-2, (S,S)-3 and (S,S)-4 stand out as prime candidates for future PET imaging studies. Further investigation into their radiosynthesis and evaluation as ACE2 PET radiotracers is ongoing in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) (Agreement 832994), Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) (EP/V013041/1; EP/R005397/1), Cancer Research UK through the Oxford Institute for Radiation Oncology, Medical Research Council (MRC) (MR/R01695X/1). We gratefully acknowledge Dr Yanyan Zhao (Molecular Imaging Chemistry Laboratory, University of Cambridge) for training and support with inhibition assay experiments. We gratefully acknowledge the group of Prof Christopher J. Schofield (Chemistry Research Laboratory, University of Oxford) for generously sharing their HPLC equipment, as well as Dr Matthew Tredwell (Wales Research and Diagnostic PET imaging centre, Cardiff University, University Hospital of Wales; School of Chemistry, Cardiff University) for providing access to radiochemistry facilities. F.A. was supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203312). The views expressed are those of the author (F.A.) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.5c00918.

Computational data and procedures; preparation and characterization of products and intermediates; radiochemistry data and protocols; in vitro study data and protocols; and NMR spectra for novel compounds (PDF)

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published on July 21, 2025. The author affiliation list was updated. The corrected version was reposted on July 23, 2025.

References

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M.. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Goldsmith J. A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S.. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L.. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X., Zhong W., Hao P.. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Basu A., Sarkar A., Maulik U.. Molecular docking study of potential phytochemicals and their effects on the complex of SARS-CoV2 spike protein and human ACE2. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):17699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Hikmet F., Méar L., Edvinsson Å., Micke P., Uhlén M., Lindskog C.. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020;16(7):e9610. doi: 10.15252/msb.20209610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M. L. C., Lely A. T., Navis G. J. V., van Goor H.. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q.. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kragstrup T. W., Singh H. S., Grundberg I., Nielsen A. L.-L., Rivellese F., Mehta A., Goldberg M. B., Filbin M. R., Qvist P., Bibby B. M.. Plasma ACE2 predicts outcome of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b García-Ayllón M. S., Moreno-Pérez O., García-Arriaza J., Ramos-Rincón J. M., Cortés-Gómez M. Á., Brinkmalm G., Andrés M., León-Ramírez J. M., Boix V., Gil J.. Plasma ACE2 species are differentially altered in COVID-19 patients. FASEB J. 2021;35(8):e21745. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100051R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Haga S., Nagata N., Okamura T., Yamamoto N., Sata T., Yamamoto N., Sasazuki T., Ishizaka Y.. TACE antagonists blocking ACE2 shedding caused by the spike protein of SARS-CoV are candidate antiviral compounds. Antiviral Res. 2010;85(3):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pedrosa M. A., Valenzuela R., Garrido-Gil P., Labandeira C. M., Navarro G., Franco R., Labandeira-Garcia J. L., Rodriguez-Perez A. I.. Experimental data using candesartan and captopril indicate no double-edged sword effect in COVID-19. Clin. Sci. 2021;135(3):465–481. doi: 10.1042/CS20201511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhang J., Xu J., Zhou S., Wang C., Wang X., Zhang W., Ning K., Pan Y., Liu T., Zhao J.. The characteristics of 527 discharged COVID-19 patients undergoing long-term follow-up in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;104:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Lei C., Qian K., Li T., Zhang S., Fu W., Ding M., Hu S.. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):2070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16048-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Monteil V., Kwon H., Prado P., Hagelkrüys A., Wimmer R. A., Stahl M., Leopoldi A., Garreta E., Del Pozo C. H., Prosper F.. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181(4):905–913.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Davidson A. M., Wysocki J., Batlle D.. Interaction of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronavirus with ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme)-2 as their main receptor: therapeutic implications. Hypertension. 2020;76(5):1339–1349. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Maza M. D. C., Úbeda M., Delgado P., Horndler L., Llamas M. A., van Santen H. M., Alarcón B., Abia D., García-Bermejo L., Serrano-Villar S., Bastolla U., Fresno M.. ACE2 Serum Levels as Predictor of Infectability and Outcome in COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022;23(13):836516. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.836516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cojocaru E., Cojocaru C., Vlad C.-E., Eva L.. Role of the Renin-Angiotensin System in long COVID’s cardiovascular injuries. Biomedicines. 2023;11(7):2004. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11072004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guedj E., Campion J., Dudouet P., Kaphan E., Bregeon F., Tissot-Dupont H., Guis S., Barthelemy F., Habert P., Ceccaldi M.. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2021;48(9):2823–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Khazaal S., Harb J., Rima M., Annweiler C., Wu Y., Cao Z., Abi Khattar Z., Legros C., Kovacic H., Fajloun Z.. The pathophysiology of long COVID throughout the renin-angiotensin system. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2903. doi: 10.3390/molecules27092903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F.. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Int. Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhang Z., Li L., Li M., Wang X.. The SARS-CoV-2 host cell receptor ACE2 correlates positively with immunotherapy response and is a potential protective factor for cancer progression. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020;18:2438–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rotondi M., Coperchini F., Ricci G., Denegri M., Croce L., Ngnitejeu S., Villani L., Magri F., Latrofa F., Chiovato L.. Detection of SARS-COV-2 receptor ACE-2 mRNA in thyroid cells: a clue for COVID-19-related subacute thyroiditis. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2021;44(5):1085–1090. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01436-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shi A. C., Ren P.. SARS-CoV-2 serology testing: Progress and challenges. J. Immunol. Methods. 2021;494:113060. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2021.113060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sluimer J., Gasc J., Hamming I., Van Goor H., Michaud A., Van Den Akker L., Jütten B., Cleutjens J., Bijnens A., Corvol P.. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and activity in human carotid atherosclerotic lesions. J. Pathol. 2008;215(3):273–279. doi: 10.1002/path.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Parker M. F., Blecha J., Rosenberg O., Ohliger M., Flavell R. R., Wilson D. M.. Cyclic 68Ga-labeled peptides for specific detection of human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Nucl. Med. 2021;62(11):1631–1637. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.261768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier F., Zlatopolskiy B. D., Neumaier B.. Nuclear medicine in times of COVID-19: how radiopharmaceuticals could help to fight the current and future pandemics. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(12):1247. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Z., Zhao C., Li C., Liu S., Ding J., He C., Liu J., Dong B., Yang Z., Liu Q.. Molecular PET/CT mapping of rhACE2 distribution and quantification in organs to aid in SARS-CoV-2 targeted therapy. J. Med. Virol. 2023;95(11):e29221. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu H., Zhang H., Zhou N., Ding J., Jiang J., Liu T., Liu Z., Wang F., Zhang Q., Zhang Z.. Molecular PET/CT profiling of ACE2 expression in vivo: implications for infection and outcome from SARS-CoV-2. Adv. Sci. 2021;8(16):2100965. doi: 10.1002/advs.202100965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ding J., Zhang Q., Jiang J., Zhou N., Yu Z., Wang Z., Meng X., Daggumati L., Liu T., Wang F.. Preclinical Evaluation and Pilot Clinical Study of 18F-Labeled Inhibitor Peptide for Noninvasive Positron Emission Tomography Mapping of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023;7(6):1758–1769. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.3c00337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Beyer D., Vaccarin C., Deupi X., Mapanao A. K., Cohrs S., Sozzi-Guo F., Grundler P. V., van der Meulen N. P., Wang J., Tanriver M.. A tool for nuclear imaging of the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor: molecular model and preclinical development of ACE2-selective radiopeptides. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging Res. 2023;13(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13550-023-00979-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ren F., Jiang H., Shi L., Zhang L., Li X., Lu Q., Li Q.. 68Ga-cyc-DX600 PET/CT in ACE2-targeted tumor imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imag. Res. 2023;50(7):2056–2067. doi: 10.1007/s00259-023-06159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales N. A., Gould A. E., Brown J. A., Calderwood E. F., Guan B., Minor C. A., Gavin J. M., Hales P., Kaushik V. K., Stewart M.. Substrate-based design of the first class of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(40):11852–11853. doi: 10.1021/ja0277226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Rong J., Haider A., Jeppesen T. E., Josephson L., Liang S. H.. Radiochemistry for positron emission tomography. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3257. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36377-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Halder R., Ritter T.. 18F-Fluorination: Challenge and Opportunity for Organic Chemists. J. Org. Chem. 2021;86(20):13873–13884. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towler P., Staker B., Prasad S. G., Menon S., Tang J., Parsons T., Ryan D., Fisher M., Williams D., Dales N. A., Patane M. A., Pantoliano M. W.. ACE2 X-Ray Structures Reveal a Large Hinge-bending Motion Important for Inhibitor Binding and Catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(17):17996–18007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fukuyama T., Jow C.-K., Cheung M.. 2-and 4-Nitrobenzenesulfonamides: Exceptionally versatile means for preparation of secondary amines and protection of amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36(36):6373–6374. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(95)01316-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yang L., Chiu K.. Solid phase synthesis of Fmoc N-methyl amino acids: application of the Fukuyama amine synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(42):7307–7310. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01774-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kan T., Kobayashi H., Fukuyama T.. Efficient synthesis of medium-sized cyclic amines by means of 2-nitrobenzenesulfonamide. Synlett. 2002;2002(5):697–699. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Amssoms K., Augustyns K., Yamani A., Zhang M., Haemers A.. An efficient synthesis of orthogonally protected spermidine. Synth. Commun. 2002;32(3):319–328. doi: 10.1081/SCC-120002114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Guisado C., Waterhouse J. E., Price W. S., Jorgensen M. R., Miller A. D.. The facile preparation of primary and secondary aminesvia an improved Fukuyama–Mitsunobu procedure. Application to the synthesis of a lung-targeted gene delivery agent. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3(6):1049–1057. doi: 10.1039/B418168A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan T., Fukuyama T.. Ns strategies: a highly versatile synthetic method for amines. Chem. Commun. 2004;35(4):353–359. doi: 10.1039/b311203a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hodges J. C.. Regiospecific synthesis of 3-substituted L-histidines. Synthesis. 1987;1987(1):20–24. doi: 10.1055/s-1987-27828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Van Den Berge E., Robiette R.. Development of a regioselective N-methylation of (benz)imidazoles providing the more sterically hindered isomer. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78(23):12220–12223. doi: 10.1021/jo401978b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tredwell M., Preshlock S. M., Taylor N. J., Gruber S., Huiban M., Passchier J., Mercier J., Genicot C., Gouverneur V.. A General Copper-Mediated Nucleophilic 18F-Fluorination of Arenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53(30):7751–7755. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mossine A. V., Brooks A. F., Makaravage K. J., Miller J. M., Ichiishi N., Sanford M. S., Scott P. J. H.. Synthesis of [18F]Arenes via the Copper-Mediated [18F]Fluorination of Boronic Acids. Org. Lett. 2015;17(23):5780–5783. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Preshlock S., Calderwood S., Verhoog S., Tredwell M., Huiban M., Hienzsch A., Gruber S., Wilson T. C., Taylor N. J., Cailly T., Schedler M., Collier T. L., Passchier J., Smits R., Mollitor J., Hoepping A., Mueller M., Genicot C., Mercier J., Gouverneur V.. Enhanced copper-mediated 18F-fluorination of aryl boronic esters provides eight radiotracers for PET applications. Chem. Commun. 2016;52(54):8361–8364. doi: 10.1039/C6CC03295H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Taylor N. J., Emer E., Preshlock S., Schedler M., Tredwell M., Verhoog S., Mercier J., Genicot C., Gouverneur V.. Derisking the Cu-Mediated 18F-Fluorination of Heterocyclic Positron Emission Tomography Radioligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139(24):8267–8276. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wilson T. C., Xavier M.-A., Knight J., Verhoog S., Torres J. B., Mosley M., Hopkins S. L., Wallington S., Allen P. D., Kersemans V., Hueting R., Smart S., Gouverneur V., Cornelissen B.. PET Imaging of PARP Expression Using 18F-Olaparib. J. Nucl. Med. 2019;60(4):504–510. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.213223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wright J. S., Kaur T., Preshlock S., Tanzey S. S., Winton W. P., Sharninghausen L. S., Wiesner N., Brooks A. F., Sanford M. S., Scott P. J. H.. Copper-mediated late-stage radiofluorination: five years of impact on preclinical and clinical PET imaging. Clin. Transl. Imaging. 2020;8:167–206. doi: 10.1007/s40336-020-00368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Chen Z., Destro G., Guibbal F., Chan C. Y., Cornelissen B., Gouverneur V.. Copper-Mediated Radiosynthesis of [18F]Rucaparib. Org. Lett. 2021;23(18):7290–7294. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During the preparation of this manuscript, the following studies on radiofluorinated derivatives of MLN-4760 were disclosed.; a Zhou P., Ning K., Xue S., Li Q., Li D., Haijun Yang H., Liang Z., Li R., Yang J., Li X., Zhang L.. An ACE2 PET imaging agent derived from 18F/Cl exchange of MLN-4760 under phase transfer catalysis. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2024;9:83. doi: 10.1186/s41181-024-00316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J., Beyer D., Vaccarin C., He Y., Tanriver M., Benoit R., Deupi X., Mu L., Bode J. W., Schibli R., Müller C.. Development of radiofluorinated MLN-4760 derivatives for PET imaging of the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor ACE2. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2024;52:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s00259-024-06831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.