Abstract

Child malnutrition is a critical public health concern in Pakistan, disproportionately affecting socioeconomically disadvantaged households. This study employs Amartya Sen’s entitlement theory and UNICEF’s malnutrition framework 2020 to examine the determinants of child malnutrition, using nationally representative data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Wave 6. Logistic regression analysis on a sample of children aged 6–23 months reveals that parental education remains an important factor. Children of educated parents experience significantly lower malnutrition rates. Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) has been found important as fulfilling the needs of MDD reduces malnutrition risk by 22%. Household’s economic status is a strong protective factor, with affluent households showing a 42% lower risk of child malnutrition. Regional disparities also remain crucial as the children belonging to Balochistan province have significantly higher risks of malnutrition. The study also conducts an in-depth analysis for rural-urban settings, noting stronger effects of MDD in urban areas than rural areas. Findings underscore the need for targeted nutrition policies and improved public health interventions to addressing child malnutrition in Pakistan.

Keywords: Child malnutrition, Dietary diversity, Socioeconomic disparities, Health determinants, Public health, Pakistan

Introduction

The epidemiological and economic literature recognizes that early childhood health can have profound implications for success later in life. Early childhood deficiencies of nutrition and poor health outcomes can lead to lower educational attainments, reduced earnings, decreased productivity and limited participation in the labour market [10, 18, 21, 22, 24, 32]. This creates a vicious cycle that persists over time and across generations, in which children from socioeconomically disadvantaged households experience poorer health outcomes and, consequently, lower incomes in adulthood. Child malnutrition, commonly reflected through the indicators of stunting, wasting and underweight, is one of the most visible expressions of the early childhood deficiencies and continues to be one of the most urgent worldwide public health challenges. According to estimates, 22.3% children under 5 years (148.1 million) suffered from stunting (low height for age), and 6.8% (45 million) experienced wasting (low weight for height) globally in 2022 [83]. Malnutrition is responsible for 45% of child deaths worldwide, primarily in low and middle-income countries [90].

The prevalence of child malnutrition can be attributed to different factors including diet intakes [35], availability of food [49, 61], infectious diseases [39, 62], economic hardships and [42] different socioeconomic conditions of the households [36, 72].

Pakistan is a low-income country situated in South Asia where 40% of children under five suffer from stunted growth, making it the country having the highest rate of stunted children in the region [75, 90]. The issue of malnutrition is deeply intertwined with the country’s broader socioeconomic challenges where low parental education, inadequate access to healthcare services, financial constraints [4, 79], entrenched gender-based inequalities in food distribution within households [2] and traditional care practices [74] can some of the key factors contributing to nutritional deficiencies of the children. The crisis of malnutrition in the country is exacerbated by the prevalence of higher poverty as it limits the access to quality healthcare and availability of sufficient and nutrient food [3, 7, 8, 52]. It leads to deficiencies of important macronutrients and micronutrients among children of poor households [4].

Another important factor influencing nutrient outcomes is diversification of dietary intakes. The WHO recommends consuming a minimum of five out of eight different food groups daily, including breast milk, grains, tubers, legumes, dairy products, flesh foods, eggs, and vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables. Children who meet the minimum dietary diversity (MDD) requirements are less likely to suffer from malnutrition-related conditions [48]. However, only 17.4% of Pakistani children reach this milestone of minimum dietary diversity, far below the global average [85]. The excessive reliance on cereal-based foods, which lack essential proteins and micronutrients, intensifies nutritional deficiencies [74].

Poor hygienic conditions within households and limited access to improved drinking water, and sanitation facilities can also be crucial. These factors increase the risk of infectious diseases such as diarrhea. It reduces the absorption of nutrients and worsens malnutrition [11]. The high incidence of gastrointestinal infections due to poor sanitation and hygiene practices continues to threaten the health of children in Pakistan particularly in the rural areas [63].

The aim of this study is to explore that how socioeconomic disadvantages of the households lead to nutritional deficiencies of their children in the early years of life. More specifically, it intends to investigate the role of different socioeconomic factors and diet intakes for children malnutrition in Pakistan. The study seeks to contribute to existing literature by providing an in-depth and updated analysis, guided by UNICEF’s malnutrition framework 2020 and utilizing the latest comprehensive data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) wave 6. The findings of the study will provide important insights which will be helpful to adopt targeted nutrition policies and interventions in Pakistan. The insights of the study may also prove valuable for designing effective policies in countries with similar contexts and challenges.

Literature review

Child malnutrition is an important public health challenge, particularly in least developed countries of the world. Research studies identified various factors including caloric intake, food shortages [43], infectious diseases and poor environmental conditions as primary and significant causes of child malnutrition [20, 67]. Over time, the focus of scholars shifted towards a broader perspective, recognizing the role of socioeconomic status of the households, parental education and income, environment related factors and policy interventions for nutritional outcomes of the children [35, 78]. This perspective has been formalised in the UNICEF’s conceptual framework on the determinants of maternal and child nutrition, 2020 adopting a more holistic approach to combat maternal and children malnutrition [86].

Socioeconomic status (SES) of households remains crucial determinant of child malnutrition. SES, often operationalized through variety of variables such as parental income, wealth, education and occupation, influences household’s access to food, health-seeking behaviours, and access to sanitation — all of which are crucial for children’s nutritional well-being [89, 91]. Studies affirm that children belonging to households with lower SES experience significantly higher rates of stunting and wasting [1, 15, 81]. Cultural norms and social values can also be important for nutritional outcomes. In patriarchal societies, cultural norms affect within household food distribution, as such norms often favour boys over girls thereby increase the risk of malnutrition among girls [30]. Gender inequality also limits women’s access to education, reduces their decision-making autonomy within households, and weakens their capacity to ensure adequate nutrition for themselves and their children [28].

Studies conducted in the context of Pakistan reveal that disparities of education and health outcomes exist in the country, and different socioeconomic variables including father’s education, mother’s education, household’s economic status and region of residence remain crucial factors to explain these disparities including the disparities of nutritional well-being of the children [6]. Educated mothers are more likely to adopt optimal child-feeding and hygiene practices, improving child nutrition outcomes [2]. SES also remains crucial for children’s social, cognitive and physical development during their early years [9]. Because of prevailing gender norms in Pakistani society, male members often get a preferential treatment, affecting within household food allocation, particularly during food scarcity, worsening the nutritional status of women and girls [74]. Evidence suggests that there are inter-provincial as well as intra-provincial disparities in the country, with rural and remote districts doing worse than urban centers due to limited access to healthcare, safe drinking water, and nutrient food [91].

Economic shocks can exacerbate the problem of malnutrition by increasing the vulnerability of socioeconomically disadvantaged segments of society. For instance, the recent COVID-19 pandemic disrupted food systems, increased food insecurity, reduced access to healthcare services and essential nutrition, and thereby exacerbating the risks of malnutrition [38, 50]. In Pakistan, assessments indicate a rise in acute malnutrition, particularly in flood-affected regions [84, 92]. During the difficult times caused by the economic shocks, households — particularly those belonging to poor and marginalized segments — had to increase the consumption of starchy staples at the expense of fruits and vegetables, a shift with potentially long-term nutritional consequences for children and pregnant women. It severely affected low-income households, especially those in the informal economy resulting job losses, reducing household food budgets and increasing reliance on suboptimal diets [73].

Dietary diversity is widely acknowledged as an important determinant of children’s nutritional status. Lack of dietary diversity is considered particularly important for micronutrient deficiencies and stunting [33, 51]. The excessive reliance on cereal-based and staple foods, with minimal consumption of fruits, vegetables, and meat are strongly linked to poor nutritional and growth outcomes among children [19, 27, 41]. Evidence suggests that low dietary diversity is a significant correlate of increased incidences of stunting and anemia in low and middle-income countries [68, 94]. Within the Pakistani context, several empirical studies reinforce this link. For instance, Saleem et al. [65] report that low dietary diversity among children under five is a strong predictor of underweight status. Similarly, Akbar et al. [2] notes that maternal dietary diversity is significantly correlated with the nutritional status of children in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. These findings align with nationally representative data showing insufficient intake of nutrient foods such as legumes, dairy, and meats [59].

Environmental factors play a crucial role for food production, food security, and the prevalence of infectious disease—all of which have direct implications for nutritional well-being [55]. Along with different socioeconomic factors, poor environmental conditions further intensify the risk of malnutrition, especially among children. Research shows that the underweight children are more likely to live in households lacking proper sanitation facilities, increasing their exposure to disease [49, 85]. Unhygienic conditions may put children at greater risk of malnutrition [64, 87]. Poor water quality and lack of improved sanitation facilities increase the burden of disease and lead to malnutrition [39, 62]. In the case of Pakistan, inadequate sanitation and hygiene practices contribute to a high incidence of infectious diseases, one of the leading cause of child malnutrition [54]. In rural areas of the country, contaminated water contributes significantly to gastrointestinal infections, which hinders nutrient absorption and results in chronic malnutrition [29, 59].

Policy interventions have become increasingly important for public health [35, 93]. Conditional cash transfer programmes such as those in Latin America [31, 42] have shown that financial assistance helps low-income families to improve access to health care and food security. The issue of child malnutrition is aggravated by economic inequality, poverty, and increased food insecurity, especially in low-income countries [37], highlighting the need of effective public policy. Low coverage of health insurance in the countries like Pakistan increases the out-of-pocket health expenditures which is a burden for low-income households. In such situation, health initiatives of the government and social protection programmes can play pivotal role in addressing malnutrition among the children of low-income families. Such interventions improve child nutrition by increasing household access to healthcare and nutrient food [34, 70, 84]. Empirical studies indicate that cash transfers programmes such as Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) designed to help women belonging to disadvantages sections of Pakistani society have had a positive impact on children’s growth and development [34, 70, 84].

Despite significant efforts to cope with the challenge of child malnutrition, it still remains a significant public health issue globally and particularly in low and middle-income countries such as Pakistan [90]. It is one of the major causes of child deaths globally and works as a formidable barrier to human capital development, poverty reduction, and achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) — zero hunger [13, 82]. In Pakistan, the prevalence of stunting (40.2%) and wasting (17.7%) among children under five remains alarmingly high, reflecting systemic inequalities and developmental failures [59]. While, there has been substantial research on the issue of child malnutrition in Pakistan, the previous studies have hardly used a holistic approach to consider various socioeconomic, environmental, diet-related and policy-related factors as possible determinants of child malnutrition. Moreover, an up-dated and in-depth analysis by utilizing nationally representative data is also rare. This study addresses these gaps by using a nationally representative data of MICS wave 6 for the analysis of determinants of child malnutrition in Pakistan.

Theoretical framework and methodology

Theoretical framework

Theoretical foundations of our study are based on Sen’s entitlement theory [69] which argues that it is not scarcity of the food but flawed mechanism of its distribution that creates starvation, hunger and malnutrition by limiting poor people’s accessibility to food. This perspective is particularly relevant in the context of least developed countries like Pakistan where flawed distribution mechanisms disproportionately affect vulnerable communities. UNICEF’s malnutrition framework 2020 [82] complements this view by suggesting a holistic approach to identify possible determinants of child malnutrition. The framework suggests different factors such as dietary intake, care practices, household food security, sanitation, healthcare access, governance, economic stability, and environmental conditions as important determinants of child malnutrition.

Data

We have used the data of Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Wave 6 (2017–2020) conducted in Pakistan by country’s provincial Bureaus of Statistics with the collaboration of UNICEF [56]. The main purpose of MICS survey is to provide high-quality data on the situation of children and women in least developed countries in order to assess the progress of the countries and regions in terms of various development goals. The survey provides data on various socioeconomic indicators related with households, children, and women including child nutrition, child and maternal mortality, literacy, school attendance, reading and numeracy skills of children, early childhood development, and access to improved sanitation and clean drinking water. The MICS data set used in the study is publicly available and adheres to ethical standards of secondary data dissemination. We have done data cleansing to obtain the comprehensive data of the variables used in our study. For this purpose, we have filtered the data of those respondents for whom the information regarding all of the indicators used in our study is available. The final sample, after applying these filters, consists of 19,380 children from four provinces, and both urban and rural areas of Pakistan.

Table 1 below provides the frequency distribution of the data used in the study with definition of the variables.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution

| VARIABLES | Full Sample | Rural Sample | Urban Sample | Variable Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malnutrition | No | 54.02% | 52.45% | 58.53% | The dependent variable of the study is malnutrition, defined according to the WHO standards for assessing child malnutrition. The WHO classifies malnutrition into three categories: stunting, underweight and wasting. Stunting is defined as low height-for-age and children are considered as stunted if their height-for-age z score falls below − 2 standard deviations from the median height-for-age. Underweight is defined as weight-for-age and child is termed as underweight if his/her weight-for-age z score is less than − 2 standard deviations from the median weight-for-age. Wasting is defined in terms of low weight-for-height where children are classified to be stunted if their weight-for-height is less than − 2 standard deviations from the median weight-for-height. We have operationalized the variable of malnutrition as binary category dummy variable, coded as 1 if child exhibits any one of the three forms of malnutrition, and 0 if the child does not suffer from any of them. |

| Yes | 45.98% | 47.55% | 41.47% | ||

| Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) | No | 82.61% | 83.49% | 80.08% | Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) is a binary variable indicating whether a child consumes at least five out of eight WHO-defined food groups daily, including breast milk, grains, tubers, legumes, dairy products, flesh foods, eggs, and vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables. |

| Yes | 17.39% | 16.51% | 19.92% | ||

| Child’s gender | Female | 48.70% | 48.68% | 48.77% | Child gender as a binary category dummy variable. Child gender is considered due to the potential disparities in nutrition and healthcare access between boys and girls. |

| Male | 51.30% | 51.32% | 51.23% | ||

| Child’s age | 6–12 | 38.73% | 38.94% | 38.14% | Child age is categorized into three groups—early infancy (6–12 months), middle infancy (12–18 months), and late infancy (19–23 months)—reflecting the crucial transition in feeding practices. |

| 12–18 | 38.70% | 38.51% | 39.25% | ||

| 19–23 | 22.56% | 22.55% | 22.61% | ||

| Mother’s education | No Education | 58.03% | 64.74% | 38.77% | Mother’s education is categorized into three levels: no education, less than secondary education, and secondary or higher education. |

| Less than Secondary | 21.56% | 20.59% | 24.35% | ||

| Secondary | 20.41% | 14.66% | 36.88% | ||

| Father’s education | No Education | 32.22% | 36.01% | 21.35% | Father’s education is categorized into three levels: no education, less than secondary education, and secondary or higher education. |

| Less than secondary | 29.01% | 29.38% | 27.98% | ||

| Secondary | 38.77% | 34.62% | 50.67% | ||

| Household’s economic status | Poor | 47.37% | 58.05% | 16.76% | Household economic status is assessed through the wealth index constructed by MICS, using variety of indicators such as asset ownership, and dwelling characteristics. Households are placed in five different quintiles on the basis of their wealth index score. We have classified households as poor if they fall in first or second quintile, middle class if they belong to third quintile, and rich if they fall in fourth or fifth quintile. |

| Middle | 20.15% | 21.27% | 16.94% | ||

| Rich | 32.48% | 20.68% | 66.29% | ||

| Smoking | Yes | 81.53% | 81.65% | 81.18% | Coded as 1 if some family member in the household smokes and 0 otherwise. |

| No | 18.47% | 18.35% | 18.82% | ||

| Access to water | No | 8.30% | 9.53% | 4.75% | Household access to clean drinking water has been operationalized by following UNDP’s definition and coded as 1 in case household has access to clean drinking water; coded as 0 otherwise. |

| Yes | 91.70% | 90.47% | 95.25% | ||

| Access to improved sanitation | No | 38.32% | 44.28% | 21.23% | Operationalized by following UNDP’s definition and coded as 1 in case household has access to improved sanitation; coded as 0 otherwise. |

| Yes | 61.68% | 55.72% | 78.77% | ||

| Social protection | No | 74.22% | 72.16% | 80.11% | Social protection has been coded as 1 if the household receives any financial assistance from any governmental or non-governmental organization, or is covered by health insurance; coded as 0 otherwise. |

| Yes | 25.78% | 27.84% | 19.89% | ||

| Region of residence | Balochistan | 15.50% | 16.01% | 14.03% | The region of residence variable represents the four provinces, allowing for an analysis of provincial differences. |

| Punjab | 43.31% | 42.88% | 44.52% | ||

| Sindh | 17.00% | 13.02% | 28.40% | ||

| KPK | 24.20% | 28.09% | 13.05% | ||

| Area of residence | Rural | 74.15% | The variable distinguishes between urban and rural settings, recognizing the potential rural-urban disparities. | ||

| Urban | 25.85% | ||||

| N | 19,380 | 14,369 | 5011 | ||

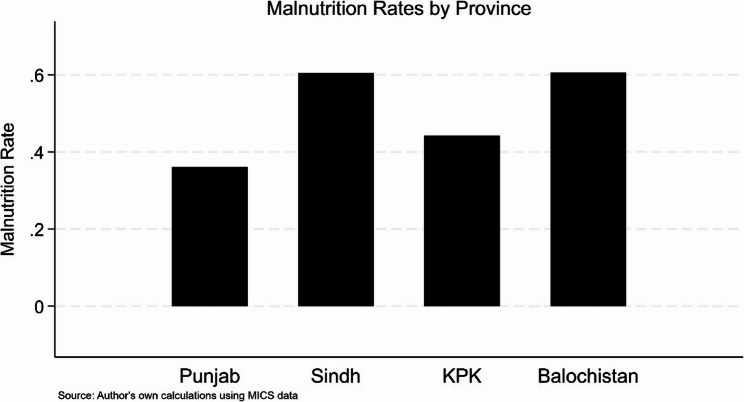

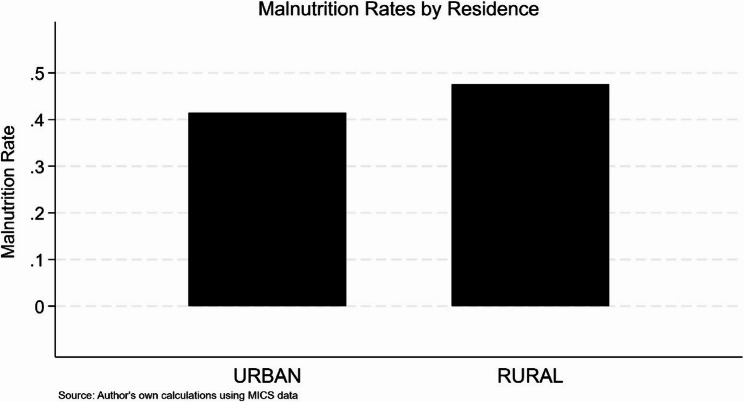

The statistics provided in the Table 1 show that our data set consists of 19,380 observations out of which 14,369 are for rural areas whereas 5011 are for urban areas. About 46% children are malnourished; 48% in rural and 41% in urban areas. The majority of the children do not meet the recommendations of the WHO regarding MDD. The food intake of only 17% children is as per recommendations of the WHO which is even lower in the case of children residing in the rural areas. Majority of the mothers (58%) do not have any formal education with even a higher proportion (65%) in the case of rural areas. Sufficiently higher number of households fall in the category of poor (47%). We have also constructed four graphs to further understand the issue of malnutrition. The prevalence of malnutrition across provinces, and rural/urban areas have been shown in the Figs. 1 and 2 respectively whereas Figs. 3 and 4 shows that how parental education and phenomenon of malnutrition are correlated (see Appendix A1).

Econometric model and estimations

Given the binary nature of the dependent variable, the study employs a logistic regression model to investigate the prevalence of child malnutrition as a function of different socioeconomic, diet related, and environment related factors. The general model specification is as follows:

|

MalNui represents the malnutrition status of child i, Xij denotes the set of explanatory variables, βi are the estimated coefficients, and εi is the error term. The specific form of our econometric model is as given:

|

This equation models the log odds of child malnutrition, where MalNu, MDD, ChGen, ChAge, EduMot, EduFat, HES, Smok, Wat, Sani, SocPro, Reg, and Area represents malnutrition, minimum dietary diversity, child’s gender, child’s age, mother’s education, father’s education, household's economic status, exposure to smoking within household premises, access to safe drinking water, access to improved sanitation facilities, availability of social protection programmes, region of residence(province), and area of residence respectively.

For robustness, the model has been estimated for full sample and separately for rural and urban samples. Multiple diagnostic tests have been performed to ensure the reliability of the findings. The goodness of fit of the model has been assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, while the discriminatory power of the model has been assessed by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and its area under curve (AUC). The model is considered as good fit if the p-value of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test is insignificant. A higher value (closer to 1) of AUC indicates that the better performance of the model. The effectiveness of the model in predicting outcomes with accuracy has been tested through Classification Performance test. The value of the test shows that to what extent the used model is accurate in the prediction. The Link test has been utilized to verify that the model does not suffer from the specification problems. An insignificant p-value of the test is termed as an indication that the model is well specified.

Results

The results of our logistic regression have been presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Logistic regression

| VARIABLES | Full Sample | Rural Sample | Urban Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odd Ratio | Coefficient | Odd Ratio | Coefficient | Odd Ratio | Coefficient | ||

| Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) | No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.779*** | −0.250*** | 0.802*** | −0.220*** | 0.725*** | −0.322*** | |

| Child’s gender | Female | Reference | |||||

| Male | 1.386*** | 0.326*** | 1.411*** | 0.345*** | 1.315*** | 0.274*** | |

| Child’s age | 6–12 | Reference | |||||

| 12–18 | 1.371*** | 0.315*** | 1.365*** | 0.311*** | 1.403*** | 0.338*** | |

| 19–23 | 1.854*** | 0.617*** | 1.878*** | 0.630*** | 1.775*** | 0.574*** | |

| Mother’s education | No Education | Reference | |||||

| Less than Secondary | 0.871*** | −0.138*** | 0.872*** | −0.137*** | 0.876 | −0.132 | |

| Secondary | 0.729*** | −0.316*** | 0.695*** | −0.364*** | 0.794*** | −0.231*** | |

| Father’s education | No Education | Reference | |||||

| Less than secondary | 0.883*** | −0.125*** | 0.875*** | −0.134*** | 0.928 | −0.0746 | |

| Secondary | 0.799*** | −0.225*** | 0.782*** | −0.245*** | 0.849* | −0.164* | |

| Household’s economic status | Poor | Reference | |||||

| Middle | 0.700*** | −0.357*** | 0.697*** | −0.361*** | 0.711*** | −0.341*** | |

| Rich | 0.583*** | −0.539*** | 0.613*** | −0.489*** | 0.530*** | −0.635*** | |

| Smoking | Yes | Reference | |||||

| No | 0.960 | −0.0411 | 0.952 | −0.0492 | 0.979 | −0.0210 | |

| Access of water | No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.982 | −0.0184 | 1.025 | 0.0244 | 0.742** | −0.298** | |

| Access of improved sanitation | No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.840*** | −0.175*** | 0.849*** | −0.164*** | 0.842** | −0.172** | |

| Social protection | No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 0.986 | −0.0139 | 0.978 | −0.0227 | 0.981 | −0.0194 | |

| Region of residence | Balochistan | Reference | |||||

| Punjab | 0.397*** | −0.923*** | 0.389*** | −0.944*** | 0.422*** | −0.863*** | |

| Sindh | 1.003 | 0.00268 | 1.110 | 0.104 | 0.909 | −0.0958 | |

| KPK | 0.557*** | −0.586*** | 0.533*** | −0.629*** | 0.710*** | −0.342*** | |

| Area of residence | Rural | Reference | |||||

| Urban | 0.957 | −0.0438 | |||||

| Constant | 1.890*** | 0.637*** | 1.746*** | 0.558*** | 2.421*** | 0.884*** | |

| N | 19,380 | 19,380 | 14,369 | 14,369 | 5,011 | 5,011 | |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow P Value | 0.3639 | 0.2365 | 0.7957 | ||||

| ROC Curve AUC | 0.6766 | 0.6839 | 0.6709 | ||||

| Classification Performance | 62.85 | 62.91 | 63.90 | ||||

| Link Test P Value | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.486 | ||||

***p < 0.01

**p < 0.05

*p < 0.1

The results of the logistic regression, presented in Table 2, provide important insights into the determinants of child malnutrition. The findings have been presented for the full sample as well as for the rural and urban sub-samples. Children who meet the minimum dietary diversity threshold have a significantly lower risk of malnutrition than those who do not. In the full sample, compliance with the MDD was associated with a 22% reduction in the risk of malnutrition (OR = 0.779, p < 0.01). The effect is stronger in urban areas, where meeting the requirements of MDD reduces the risk of malnutrition by 28% (OR = 0.725, p < 0.01) compared to 20% in rural areas (OR = 0.802, p < 0.01).

Results of gender are interesting, with male children are more likely to be stunted than female children. Overall, boys have a 38% higher risk of malnourishment (OR = 1.386, p < 0.01), a pattern that is consistent across rural (OR = 1.411, p < 0.01) and urban settings (OR = 1.315, p < 0.01). Another important predictor is age, with older children (19–23 months) having an 85.4% higher risk of malnutrition than children aged 6–12 months (OR = 1.854, p < 0.01), reflecting an increased vulnerability as children move into supplementary feeding. Parental education plays a crucial role in reducing malnutrition risk, with maternal education showing a stronger protective effect than paternal education. Children whose mothers have secondary education experience a 20.6% lower likelihood of malnutrition (OR = 0.794, p < 0.01), with the effect slightly stronger in rural areas (OR = 0.695, p < 0.01) than urban areas (OR = 0.794, p < 0.01). Similarly, higher paternal education is linked to improved child nutrition, particularly in urban households (OR = 0.849, p < 0.05 for secondary education). Household economic status emerges as a key predictor of malnutrition, with children from wealthier households significantly less likely to be malnourished. Compared to children from poor households, those from middle-income families have 30% lower odds of malnutrition (OR = 0.700, p < 0.01), while children from wealthy households experience a 41.7% reduction (OR = 0.583, p < 0.01). The protective effect of wealth is more pronounced in urban areas (OR = 0.530, p < 0.01), probably due to better healthcare services. Access to improved sanitation is associated with a 16–18% reduction in malnutrition risk (OR = 0.840, p < 0.01 overall), with similar effects observed in both rural (OR = 0.849) and urban (OR = 0.842) settings. However, access to improved water sources does not show a statistically significant association with malnutrition in the full or rural samples. Interestingly, a significant association is only found in urban areas (OR = 0.742, p < 0.01), suggesting that access to clean water may be more impactful in dense urban settings. Regional disparities in child malnutrition are evident, with children in Punjab (OR = 0.397, p < 0.01) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) (OR = 0.557, p < 0.01) significantly less likely to be malnourished compared to those in Balochistan. In contrast, no significant difference is observed between Sindh (OR = 1.003) and Balochistan, highlighting persistent challenges in these regions.

The p-value of The Hosmer–Lemeshow test is 0.36399 which confirms a good fit for model. The reported p-value is above 0.05 suggesting no significant difference between observed and predicted values. The ROC-AUC value of 0.6766, indicate that the model has a good ability to differentiate between malnourished and non-malnourished children. The classification accuracy of the model remains reasonably good with a value of 62.85%. The Link test p-value (0.997) indicates that our model is well specified and does not have any problem of misspecification.

Discussion

This study highlights the critical role of parental education, MDD, household’s economic status, their region of residence and access to improved sanitation facilities for child malnutrition in Pakistan. Achieving MDD is strongly associated with a reduced risk of malnutrition. Our findings are consistent with previous studies [12]; [44, 55, 91], showing that dietary diversity is a powerful predictor of child’s growth and nutrition [46]. However, our study further refined these findings by showing that the effect is particularly stronger in urban areas than rural areas. This can be attributed to improved food availability, better information and greater access to nutrition programmes in urban settings [49].

Our findings show that male children are more likely to be malnourished than female children. While, existing literature has highlighted the role of cultural norms and social values due to which girls may be at greater risk of malnourishment particularly in the less developed regions and countries of the world [17, 58]. The findings of our study are in line with some of the existing studies [45] which indicate that increased risk of malnutrition in boys may be due to biological vulnerability, which makes them more susceptible to infections and nutritional deficiencies [80, 88]. Another key determinant is age, with older children (19–23 months) having almost a doubled risk of malnutrition compared to younger children (6–12 months). This is in line with the findings of Na et al. [53] who argue that the transition from breastfeeding to supplementary feeding often exposes children to insufficient nutrition and increases their vulnerability to undernutrition. These results suggest that targeted nutrition interventions should focus on improving complementary feeding practices in older children, especially in rural settings where dietary choices may be limited.

The nutritional performance of children is strongly influenced by parental education, particularly that of the mother [14]. Our research shows that the risk of malnutrition is reduced by 28% for children whose mothers have completed secondary education, with a slightly stronger protective effect in rural areas. It can be due to the reason that mothers with higher educational attainment are more likely to use health services and adopt healthier feeding patterns [66]. Moreover, although it plays a smaller role, father’s education also remains important. These results are in line with the findings of Djemai et al. [26], which report that father’s education benefits children’s nutrition by increasing food security and household income. Interestingly, our research shows that the impact of maternal education varies slightly between rural and urban settings. Although previous research has highlighted the importance of maternal education in reducing child malnutrition, our results show that the impact is more pronounced in rural areas. This may be due to the reason that maternal awareness is more important in rural areas, where access to health and nutrition services is more limited [71].

The economic status of the household has a major impact on child malnutrition; children from richer households are far less likely to be malnourished. Our research shows that children from middle-class families are 30% less likely, while children from high-income families are 42% less likely to be malnourished. These results support the view that improved access to health care, higher household income and better quality food contribute to children’s nutritional and overall well-being [5]. Although economic status is a well-established predictor of child malnutrition, its impact is more pronounced in urban settings.

In line with previous research showing that access to improved sanitation is strongly correlated with reduced risk of malnutrition [39], our results indicate that children with access to improved sanitation are 16% less likely to be malnourished. However, contrary to some previous research, there is no statistically significant correlation between malnutrition and access to improved water [25]. The risk of child malnutrition varies considerably between regions; children belonging to the provinces of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have significantly lower risks than children of Balochistan, a relatively less developed province of the country. The findings are consistent with Khaliq et al. [47], which highlighted Balochistan’s continuing struggle in the areas of maternal education, access to healthcare and food security. Our findings add to our knowledge of existing regional inequalities in the country [6, 60], highlighting the need for targeted interventions in less developed regions.

Our findings show that dietary diversity has a stronger protective effect in urban areas compared to rural settings. This difference can be attributed to better food accessibility in urban areas [23]. Additionally, urban mothers tend to have higher awareness of nutrition due to exposure to media, education, and healthcare services, enabling them to make informed dietary choices [40]. The presence of stronger public health infrastructure also reinforces the effectiveness of dietary diversity in urban regions, as nutritional guidance and intervention programmes are more readily available [57]. However, rural households often experience limited food diversity, influenced by seasonal agricultural constraints and lower purchasing power [76]. Future policies should focus on improving nutrition education, food accessibility, and local dietary interventions in rural areas to close the gap. While access to improved water is generally associated with better health outcomes [77], it has not been found statistically significant in our case. Similarly, the role of social protection programmes has not been found statistically significant to reduce child malnutrition which may be due to limited coverage, and insufficient funds available for such programmes [16]. Absence of effective mechanism for disbursement of funds as well as inadequate amounts of the funds may prevent these programmes from effectively addressing structural food security challenges in vulnerable households. This highlights the need for effective designing and implementation of such programmes.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The study reinforces the notion that nutritional deficiencies of children are broadly shaped by the socioeconomic disadvantages of their households. Children belonging to socioeconomically disadvantaged households —characterized by low parental education, limited financial resources, and poor living conditions— and those residing in least developed regions of the country are more likely to suffer from malnutrition. It is an indication of persistent structural inequalities in the society, due to which a vicious cycle is created, that persists over time and across generations. As a result of it, children from socioeconomically disadvantaged households experience poorer health outcomes and, consequently, lower incomes in their adulthood. Effective public policies are needed to eliminate these inequalities. Ensuring access to education, particularly for girls, and provision of equal economic opportunities for all sections of the society can be used as important and effective policy tools for this purpose. Equal distribution of infrastructure and public services for all segments of the society must also be ensured. Minimum dietary diversity, something that is often out of reach for the economically disadvantaged, can also be ensured by bringing improvements in the living standards of the people through effective policies. Awareness campaigns may also be helpful in this regard.

Addressing the issue of regional disparities is also crucial to cope with the challenge of malnutrition as such disparities translate into the differences of nutritional and health outcomes of the children across provinces. Special attention must be given to uplift the living standards of poor people residing in the least developed regions of the country. Social protection programmes are generally considered important for the betterment of marginalized communities and disadvantaged section of the society. However, our findings show that such programmes fail to have any significant effect to address the challenges of child malnutrition in Pakistan. This highlights the need of effective designing and implementations of these programmes in the country.

While, our study provides important insights and relevant policy suggestion to combat child malnutrition, it has certain limitations. One such limitation stems from the use of cross-sectional data due to non-availability of some comprehensive and reliable longitudinal data which can be more useful to establish causal inferences. Moreover, our analysis could not include some potentially important factors—such as feeding and caregiving practices, intra-household food distribution, and the mother’s role in household decision-making—primarily due to data constraints.

Appendix

Authors’ contributions

The idea of the paper was mutually conceived by Shahla Akram, Feroz Zahid and Zahid Pervaiz. Review of the relevant literature was jointly conducted by Shahla Akram and Feroz Zahid. Shahla Akram did the data cleansing whereas data analysis was done by Shahla Akram and Zahid Pervaiz. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by Shahla Akram and Feroz Zahid which was reviewed and improved by Zahid Pervaiz. The revisions suggested by the reviewers were handled by Shahla Akram, Rong Wang, Sajjad Ahmad Jan, Feroz Zahid and Zahid Pervaiz through mutual discussions. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data used in the study is publicly available and can be assessed at https://mics.unicef.org/surveys.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Addae HY, Sulemana M, Yakubu T, Atosona A, Tahiru R, Azupogo F. Low birth weight, household socio-economic status, water and sanitation are associated with stunting and wasting among children aged 6–23 months: results from a national survey in Ghana. PLoS One. 2024;19(3):e0297698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbar M, Asif AM, Hussain F. Does maternal empowerment improve dietary diversity of children? Evidence from Pakistan demographic and health survey 2017–18. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2022;37(6):3297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akeredolu JO. Nigeria: the role of nutrition as central to public health’s focus on prenatal care, childhood growth and development. Int J Community Res. 2021;10(1):20–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtar S. Malnutrition in South Asia—a critical reappraisal. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(14):2320–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akombi BJ, Agho KE, Hall JJ, Wali N, Renzaho AM, Merom D. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akram S, Pervaiz Z. Assessing inequality of opportunities for child well-being in Pakistan. Child Indic Res. 2025;18(2):525–42. 10.1007/s12187-024-10205-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akram S, Pervaiz Z, Jan SA. Do circumstances matter for earnings?? An empirical evidence fromhousehold level survey in Punjab (Pakistan). J Contemp Issues Bus Government. 2021;27(1):298–310. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akram S, Pervaiz Z, Jan SA, Saeed Khan K. Cross-district analysis of income inequality and education inequality in Punjab (Pakistan). Int J Manage. 2021;12(2):561–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akram S, Zahid F, Pervaiz Z. Socioeconomic determinants of early childhood development: evidence from Pakistan. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43(1):70. 10.1186/s41043-024-00569-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alderman H, Hoddinott J, Kinsey B. Long term consequences of early childhood malnutrition. Oxf Econ Pap. 2006;58(3):450–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali A. Current status of malnutrition and stunting in Pakistani children: what needs to be done?? J Am Coll Nutr. 2021;40(2):180–92. 10.1080/07315724.2020.1750504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arimond M, Ruel MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. J Nutr. 2004;134(10):2579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atukunda P, Eide WB, Kardel KR, Iversen PO, Westerberg AC. Unlocking the potential for achievement of the UN sustainable development goal 2–‘Zero Hunger’–in africa: targets, strategies, synergies and challenges. Food Nutr Res. 2021;65:27686. 10.29219/fnr.v29265.27686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bawa SG, Haldeman L. Fathers nutrition knowledge and child feeding practices associated with childhood overweight and obesity: a scoping review of literature from 2000 to 2023. Glob Pediatr Health. 2024;11:2333794X241263199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belayneh M, Loha E, Lindtjørn B. Seasonal variation of household food insecurity and household dietary diversity on wasting and stunting among young children in a drought prone area in South Ethiopia: a cohort study. Ecol Food Nutr. 2021;60(1):44–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belete GY. Impacts of social protection programmes on children’s resources and wellbeing: evidence from Ethiopia. Child Indic Res. 2021;14(2):681–712. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhalotra S, Rawlings SB. Intergenerational persistence in health in developing countries: the penalty of gender inequality? J Public Econ. 2011;95(3–4):286–99. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LC, Andersen CT, DiGirolamo AM, Lu C, McCoy DC, Fink G, Shawar YR, Shiffman J. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):77–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonis-Profumo G, Stacey N, Brimblecombe J. Maternal diets matter for children’s dietary quality: seasonal dietary diversity and animal-source foods consumption in rural Timor-Leste. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(1):e13071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calder PC, Jackson AA. Undernutrition, infection and immune function. Nutr Res Rev. 2000;13(1):3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient. Am Econ Rev. 2002;92(5):1308–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Case A, Fertig A, Paxson C. The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. J Health Econ. 2005;24(2):365–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Codjoe SNA, Okutu D, Abu M. Urban household characteristics and dietary diversity: an analysis of food security in Accra, Ghana. Food Nutr Bull. 2016;37(2):202–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currie J, Almond D. Human capital development before age five. In: Handbook of labor economics, vol. 4. Elsevier; 2011. p. 1315–486. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dearden KA, Schott W, Crookston BT, Humphries DL, Penny ME, Behrman JR, Determinants YL, Woldehanna CoCGPTSCLTDJELFSGPHAGELSMAST. Children with access to improved sanitation but not improved water are at lower risk of stunting compared to children without access: a cohort study in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Djemai E, Renard Y, Samson A-L. Mothers and fathers: education, co-residence, and child health. J Popul Econ. 2023;36(4):2609–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erokhin V, Diao L, Gao T, Andrei J-V, Ivolga A, Zong Y. The supply of calories, proteins, and fats in low-income countries: a four-decade retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FAO. Country gender spotlight– Pakistan. 2023. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a6770583-2d73-4a53-a97f-25d1301df40e/content.

- 29.Farooq R, Khan H, Khan MA, Aslam M. Socioeconomic and demographic factors determining the underweight prevalence among children under-five in Punjab. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fielding-Singh P. Dining with dad: fathers’ influences on family food practices. Appetite. 2017;117:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiszbein A, Schady NR. Conditional cash transfers: reducing present and future poverty. World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flores M, Wolfe BL. Childhood health conditions and lifetime labor market outcomes. Am J Health Econ. 2022;8(4):506–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geda NR, Feng CX, Henry CJ, Lepnurm R, Janzen B, Whiting SJ. Multiple anthropometric and nutritional deficiencies in young children in Ethiopia: a multi-level analysis based on a nationally representative data. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gitter SR, Manley J, Bernstein J, Winters P. Do agricultural support and cash transfer programmes improve nutritional status? J Int Dev. 2022;34(1):203–35. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haddad L, Achadi E, Bendech MA, Ahuja A, Bhatia K, Bhutta Z, Blössner M, Borghi E, Colecraft E, De Onis M. The global nutrition report 2014: actions and accountability to accelerate the world’s progress on nutrition. J Nutr. 2015;145(4):663–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris J, Nisbett N. The basic determinants of malnutrition: resources, structures, ideas and power. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2020;10(12):817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Head JR, Chanthavilay P, Catton H, Vongsitthi A, Khamphouxay K, Simphaly N. Changes in household food security, access to health services and income in Northern Lao PDR during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e055935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huizar MI, Arena R, Laddu DR. The global food syndemic: the impact of food insecurity, malnutrition and obesity on the healthspan amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;64:105–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humphrey JH. Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):1032–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam MM. The use of mass media by mothers and its association with their children’s early development: comparison between urban and rural areas. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayawardena NS, Dewasiri NJ. Food acquisition and consumption issues of South Asian countries: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. FIIB Business Review, 0(0). 2023:23197145231194113. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145231194113 10.1177/23197145231194113.

- 42.Jehan K, Sidney K, Smith H, De Costa A. Improving access to maternity services: an overview of cash transfer and voucher schemes in South Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(39):142–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jelliffe DB. The assessment of the nutritional status of the community (with special reference to field surveys in developing regions of the world). 1966.Geneva: World Health Organization. (WHO monograph series no 53, 271). 10.5555/19671407742. [PubMed]

- 44.Jones AD, Shrinivas A, Bezner-Kerr R. Farm production diversity is associated with greater household dietary diversity in Malawi: findings from nationally representative data. Food Policy. 2014;46:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kandala N-B, Madungu TP, Emina JB, Nzita KP, Cappuccio FP. Malnutrition among children under the age of five in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): does geographic location matter? BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kansal S, Raj A, Smita K, Worsley A, Rathi N. How do adolescents classify foods as healthy and unhealthy? A qualitative inquiry from rural India. J Nutr Sci. 2023;12:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khaliq A, Wraith D, Miller Y, Nambiar-Mann S. Prevalence, trends, and socioeconomic determinants of coexisting forms of malnutrition amongst children under five years of age in Pakistan. Nutrients. 2021;13(12):4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khaliq A, Nambiar S, Miller Y, Wraith D. Adherence to complementary feeding indicators and their associations with coexisting forms of malnutrition in children aged between 6 to 23.9 months of age. J Public Health. 2023. 10.1007/s10389-023-02054-5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar R, Mahmood T, Naeem N, Khan SA, Hanif M, Pongpanich S. Minimum dietary diversity and associated determinants among children aged 6–23 months in Pakistan. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCann J, Sinno L, Ramadhan E, Assefa N, Berhane HY, Madzorera I, Fawzi W. COVID-19 disruptions of food systems and nutrition services in Ethiopia: evidence of the impacts and policy responses. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millanzi WC, Herman PZ, Ambrose BA. Feeding practices, dietary adequacy, and dietary diversities among caregivers with under-five children: a descriptive cross-section study in Dodoma region, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0283036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muonde M, Olorunsogo TO, Ogugua JO, Maduka CP, Omotayo O. Global nutrition challenges: A public health review of dietary risks and interventions. World J Adv Res Reviews. 2024;21(1):1467–78. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Na M, Aguayo VM, Arimond M, Stewart CP. Risk factors of poor complementary feeding practices in Pakistani children aged 6–23 months: a multilevel analysis of the demographic and health survey 2012–2013. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadeem M, Anwar M, Adil S, Syed W, Al-Rawi MBA, Iqbal A. The association between water, sanitation, hygiene, and child underweight in Punjab, Pakistan: an application of population attributable fraction. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024. 10.2147/JMDH.S461986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ngure FM, Reid BM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MN, Pelto G, Stoltzfus RJ. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: making the links. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1308(1):118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nutrition Strategy 2020–2030. In: UNICEF New York, NY.

- 57.Onwujekwe O, Mbachu CO, Ajaero C, Uzochukwu B, Agwu P, Onuh J, Orjiakor CT, Odii A, Mirzoev T. Analysis of equity and social inclusiveness of National urban development policies and strategies through the lenses of health and nutrition. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pathirana NL, Zorbas C, Khadka S, Pokhrel HP, Paudyal N, Dharmakeerthi N, Backholer K, Sethi V. Addressing systemic exclusion and gender norms to improve nutritional outcomes for adolescent girls in South Asia. BMJ. 2025;388:e080360. 10.1136/bmj-2024-080360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.PDHS. National Institute of Population Study (NIPS)[Pakistan] and ICF International. PakistanDemographic and Health Survey (2017-8). Islamabad, Pakistan, and Cleverton, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF International. 2018.

- 60.Pervaiz Z, Akram S, Ahmad Jan S. Social exclusion in Pakistan: an ethnographic and regional perspective. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 2021;41(11/12):1183–94. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prasad R, Shukla A, Galhotra A. Feeding practices and nutritional status of children (6–23 months) in an urban area of Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023;12(10):2366–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prendergast AJ, Humphrey JH. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2014;34(4):250–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rahmat ZS, Zubair A, Abdi I, Humayun N, Arshad F, Essar MY. The rise of diarrheal illnesses in the children of Pakistan amidst COVID-19: a narrative review. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(1):e1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sahiledengle B, Petrucka P, Kumie A, Mwanri L, Beressa G, Atlaw D, Tekalegn Y, Zenbaba D, Desta F, Agho KE. Association between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and child undernutrition in Ethiopia: a hierarchical approach. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saleem J, Zakar R, Bukhari GMJ, Fatima A, Fischer F. Developmental delay and its predictors among children under five years of age with uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition: a cross-sectional study in rural Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarwar A, Jadoon AK, Chaudhry MA, Latif A, Javaid MF. How important is parental education for child nutrition: analyzing the relative significance of mothers’ and fathers’ education. Int J Soc Econ. 2024;51(10):1209–25. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scrimshaw NS, SanGiovanni JP. Synergism of nutrition, infection, and immunity: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):S464–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seid A, Dugassa Fufa D, Weldeyohannes M, Tadesse Z, Fenta SL, Bitew ZW, Dessie G. Inadequate dietary diversity during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal anemia and low birth weight in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11(7):3706–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sen A. The food problem: theory and policy. Third World Q. 1982;4(3):447–59. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shabbar S. Impact of cash transfer on food accessibility and calorie-intake in Pakistan. J Dev Eff. 2024;16(4):386–407. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shahid M, Cao Y, Ahmed F, Raza S, Guo J, Malik NI, Rauf U, Qureshi MG, Saheed R, Maryam R. Does mothers’ awareness of health and nutrition matter? A case study of child malnutrition in marginalized rural community of punjab, Pakistan. Front Public Health. 2022a;10:792164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shahid M, Cao Y, Shahzad M, Saheed R, Rauf U, Qureshi MG, Hasnat A, Bibi A, Ahmed F. Socio-economic and environmental determinants of malnutrition in under three children: evidence from PDHS-2018. Children (Basel). 2022b;9(3):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shahzad MA, Razzaq A, Wang L, Zhou Y, Qin S. Impact of COVID-19 on dietary diversity and food security in Pakistan: a comprehensive analysis. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024;110:104642. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheikh S, Barolia R, Habib A, Azam I, Qureshi R, Iqbal R. If the food is finished after my brother eats then we (girls) sleep hungry. Food insecurity and dietary diversity among slum-dwelling adolescent girls and boys in Pakistan: a mixed methods study. Appetite. 2024;195:107212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shekar M, Dell’aira C. New data exposes alarming child malnutrition trends. 2023. Retrieved 3 March from https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/new-data-exposes-alarming-child-malnutrition-trends.

- 76.Sibhatu KT, Qaim M. Rural food security, subsistence agriculture, and seasonality. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Singh PK, Kumar U, Kumar I, Dwivedi A, Singh P, Mishra S, Seth CS, Sharma RK. Critical review on toxic contaminants in surface water ecosystem: sources, monitoring, and its impact on human health. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;31(45):56428–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Strauss J, Thomas D. Health, nutrition, and economic development. J Econ Lit. 1998;36(2):766–817. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Syeda B, Agho K, Wilson L, Maheshwari GK, Raza MQ. Relationship between breastfeeding duration and undernutrition conditions among children aged 0–3 years in Pakistan. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2021;8(1):10–7. 10.1016/j.ijpam.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A, Wells J, Khara T, Dolan C, Briend A, Myatt M, Garenne M, Sear R. Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12):e004030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toma TM, Andargie KT, Alula RA, Kebede BM, Gujo MM. Factors associated with wasting and stunting among children aged 06–59 months in South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2023;9(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.UNICEF. Nutrition, for Every Child: UNICEF. 2020.

- 83.UNICEF. 2023. data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/.

- 84.UNICEF. Building synergies between child nutrition and social protection to address malnutrition and poverty. 2023. https://www.unicef.org/media/151141/file/Building%20synergies%20between%20child%20nutrition%20and%20social%20protection%20to%20address%20malnutrition%20and%20poverty.pdf.

- 85.UNICEF. Improving maternal, infant and young child nutrition expands opportunities for every child to reach his or her full potential. 2023. Retrieved 05, March from https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/child-nutrition/.

- 86.UNICEF. UNICEF conceptual framework on the determinants of maternal and child nutrition. In: UNICEF New York, NY. 2021.

- 87.Wagstaff A, Bustreo F, Bryce J, Claeson M. Child health: reaching the poor. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):726–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Boys are more stunted than girls in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang T, Akram S, Hassan MU, Khurram F, Shahzad MF. The role of child development and socioeconomic factors in child obesity in Pakistan. Acta Psychol. 2025;255:104966. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.WHO. Malnutrition. 2024. Retrieved 1 March from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition.

- 91.Xing L, Akram S, Hassan MU, Khurram H, Shaheryar H, Shahzad MF. The impact of household resilience and dietary diversity on child malnutrition. Health Soc Care Commun. 2025;2025(1):6553434. 10.1155/hsc/6553434. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yasmin F, Asghar MS, Sahito AM, Savul S, Afridi MSI, Ahmed MJ, Shah SMI, Siddiqui SA, Nauman H, Khattak AK. Dietary and lifestyle changes among Pakistani adults during COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide cross-sectional analysis. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(6):3209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yngve A, Oshaug A, Margetts B, Tseng M, Hughes R, Cannon G. World food summits: what for, and what value? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(2):151–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zeinalabedini M, Zamani B, Nasli-Esfahani E, Azadbakht L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of dietary diversity with undernutrition in school-aged children. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study is publicly available and can be assessed at https://mics.unicef.org/surveys.