Abstract

Background

Stroke is associated with vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin B1 (VitB1); however, large-scale data supporting the association between VitB1 and stroke risk are lacking. In this study, we aimed to investigate the correlation between VitB1 intake and stroke risk in U.S. adults.

Methods

This retrospective study examined American adults using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). We analyzed data collected from eight NHANES conducted between 2003 and 2018, focusing on 15,381 participants aged ≥ 60 years. After excluding participants with missing information, the study comprised 11,724 individuals. All data were analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression methods, restricted cubic spline, and sensitivity analyses.

Results

A total of 11,724 people were investigated in this survey. Dietary VitB1 levels were higher in the non-stroke group than in the stroke group (p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that VitB1 intake (as a continuous variable) and stroke risk exhibited an inverse association, with odds ratios (ORs) of 0.71 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61, 0.82) and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.61, 0.84) in the crude model and Model 1, respectively. According to the fully adjusted model, each unit increase in VitB1 intake was linked to a 37% reduction in stroke risk (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.83); that is, the greater the VitB1 intake, the lower the stroke risk.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that lower dietary VitB1 intake was associated with an increased risk of stroke in older individuals, highlighting the potential importance of adequate dietary thiamine intake in stroke prevention strategies for the aging population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12883-025-04333-y.

Keywords: Stroke, Vitamin B1, NHANES, Cross-sectional study

Background

Stroke is the second most common cause of death worldwide [1]. The economic burden of stroke-related disability is high and grows rapidly in lower-middle-income countries [2]. Stroke is projected to cost over $891 billion annually in direct expenditure (i.e., medical treatment and rehabilitation) and consequent indirect expenses (i.e., loss of production capacity) [3]. Therefore, stroke imposes a substantial economic burden on society and represents a critical challenge for humans. These findings indicate an urgent need for practical solutions to relieve the burden of stroke to save lives and enhance brain health, quality of life and socioeconomic productivity globally.

Vitamin B1 (VitB1) is a micronutrient that maintains normal cellular function and is a cofactor for many enzymes in human metabolic processes [4, 5]. Similarly, it is significant in sustaining the function of nerve membranes and synthesizing neurotransmitters [4]. In addition, VitB1 has antioxidant effects, reduces oxidative stress, and helps protect nerve cells [6].

VitB1 is not produced in the body; however, it is predominantly absorbed from food, with only small amounts stored in the body [7]. Therefore, the human body is extremely prone to VitB1 deficiency [8]. Decreased VitB1 intake may cause significant clinical symptoms, particularly in the neurological and cardiovascular systems [9]. Multiple previous studies have demonstrated that Wernicke's encephalopathy and Korsakoff's psychosis are central nervous system manifestations associated with VitB1 deficiency [10, 11]. A cross-sectional study reported that blood VitB1 levels were positively associated with cognitive function in older Chinese adults without dementia [12]. In addition, previous studies have revealed an association between VitB1 intake and glucose metabolism dysfunction in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Moreover, a previous study mentioned that high-dose VitB1 intake may improve vascular complications of the disease [13]. VitB1 supplementation may be able to reverse cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, myocardial infarction, and psychiatric disorders [14]. Reduced dietary VitB1 intake may cause disturbances in the metabolism of lipids and sugars in the body. Physiopathological changes in metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance, enhanced oxidative stress, and inflammatory response activation, predispose individuals to atherosclerosis and increase stroke risk [15]. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between dietary VitB1 intake and increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular mortality [16]. A retrospective cohort study of 119 patients with stroke revealed that patients with acute stroke had low plasma VitB1 levels [17]. Thus, VitB1 intake may be associated with stroke risk; however, large-scale population-based surveys examining the association between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk are lacking. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the relationship between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2003 and 2018.

Methods

Study population

The NHANES is a large-scale sample survey administered by the U.S.A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is stratified and multistage, with the primary purpose of collecting data on the nutritional and health status of children and adults in the U.S.A. This survey was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) ethics review committee. All individuals who participated in the survey provided informed consent. All the data were extracted from the NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

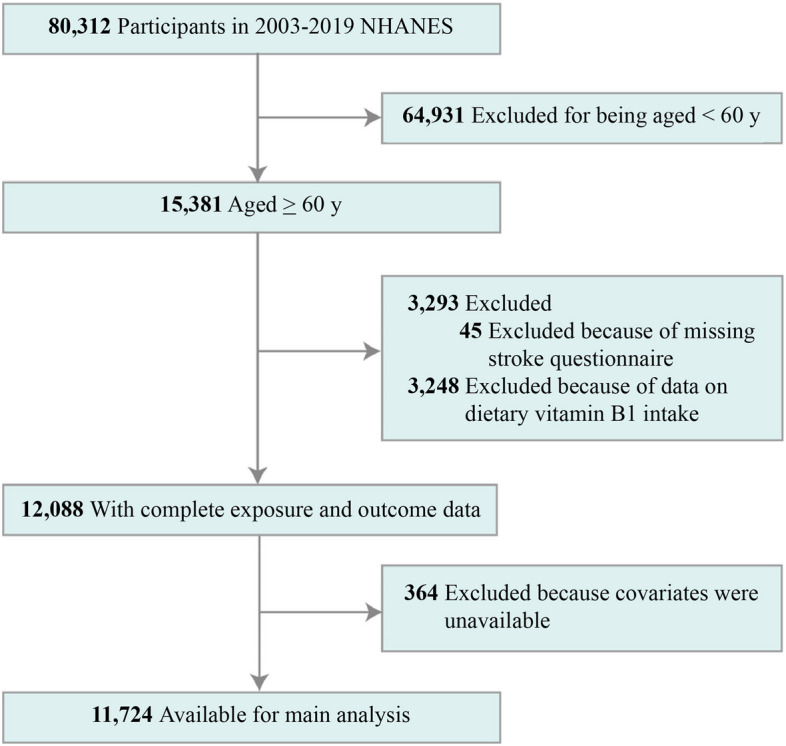

For this survey, we analyzed information from eight cycles of NHANES conducted between 2003 and 2018, focusing on a total of 15,381 participants aged ≥ 60 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) absence of a stroke questionnaire (n = 45), 2) absence of data on dietary VitB1 intake (n = 3,248), and 3) absence of other covariates (n = 364). Finally, 11,724 participants were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting the selection of study participants. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Assessment of dietary VitB1 intake

The NHANES involved the estimation of dietary VitB1 intake through dietary recall interviews. Trained investigators collected data from mobile examination centers (MECs). The first data collection was conducted onsite at the MEC, and the second data collection was conducted over the phone after 3–10 days. The U.S.A Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Database for Dietary Studies was used to estimate dietary VitB1 intake, providing information on the vitamin content in different foods [18]. In this study, the average dietary VitB1 intake was determined based on the results of two interviews.

Definition of stroke

Stroke status was assessed through personal self-reported survey information using the Medical Condition Questionnaire. Participants were asked whether their doctors had ever made them aware of their stroke experience. Those who answered definitively were classified into the stroke group, and those who refuted were classified into the non-stroke group. Notably, stroke events in the NHANES databank were identified using the questionnaire but not through medical imaging or clinical diagnosis, which means that we were unsuccessful in distinguishing between hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes.

Covariates

According to previous studies [19, 20], we incorporated covariates related to stroke risk factors, including sex, age, race, marital status (married or unmarried), education level (≤ high school or > high school), smoking status, physical activity (sustained for a minimum of 10 min/week), body mass index (BMI) [weight (in kg) divided by height (in m2)], and alcohol intake. Additionally, comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary heart disease (CHD), were considered. Smoking status was classified as current smokers (> 100 cigarettes in a lifetime and currently smoking), former smokers (> 100 cigarettes in a lifetime but not presently smoking), or never smokers (< 100 cigarettes in a lifetime). Diabetes mellitus referred to a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (%) ≥ 6.5, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or the use of diabetes medications or insulin [21]. Participants were classified as having hypertension if their mean systolic blood pressure was > 130 mmHg, mean diastolic blood pressure was > 80 mmHg (mean of three measurements), or they were taking antihypertensive medications [22]. Participants were categorized as having hyperlipidemia if they fulfilled any of the following criteria: triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL, total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein ≥ 130 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein ≤ 40 mg/dL for men or ≤ 50 mg/dL for women, or self-reported use of cholesterol-lowering medications [23]. Coronary artery disease was diagnosed using self-reports on the Medical Condition Questionnaire [24].

Statistical analyses

The NHANES involves a stratified multistage design; thus, all analyses included sample weights. To ensure accuracy of the results, we used the subsample weights of the second-day meals of the eight cycles as the study weight. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs) and were compared using t-tests. Qualitative variables are presented as case numbers (n) and percentages (%) and were compared using a weighted chi-square test. Dietary VitB1 intake was analyzed as continuous and categorical variables. VitB1 categorical variables were grouped by quartiles of intake, Q1: < 25%, Q2: ≥ 25%–50%, Q3: ≥ 50%–75%, and Q4: ≥ 75%, taking the first quartile group (Q1) as the reference. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to analyze the relationship between VitB1 intake and stroke risk. Three multivariate logistic regression models were used for the analysis. Model 1 was adjusted for demographic characteristics (sex, age, and race). Model 2 was adjusted for marital status, education level, physical activity, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, diabetes, hypertension, CHD, and hyperlipidemia and included Model 1 variables. Subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, ethnicity, and BMI, as well as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, CHD, and hyperlipidemia statuses were conducted to evaluate the heterogeneity between VitB1 intake and stroke incidence among the different subgroups. Similarly, an interaction analysis was performed, and p < 0.05 for interaction indicated the presence of an interaction effect. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis (three nodes, 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles) was used to evaluate the nonlinear correlation between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk. The number of nodes was determined based on the minimum values of the Akaike Information Criteria. For the nonlinear p-value, the likelihood ratio test was applied by comparing the log-likelihood values of different RCS models, and the p-value was calculated using the chi-square test. The overall p-value was determined using the Wald test, which is based on the estimated values of the model parameters and the standard error to construct the Wald statistic and finally determine its p-value. A nonlinear p-value < 0.05 indicated that the relationship between the variable and outcome was not simply linear and that there was a nonlinear association. To investigate the robustness of the findings, we performed sensitivity analyses, restricting the analyses to participants without stroke at baseline and excluding those with stroke during the first year of follow-up.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2, CRAN Team, Vienna, Australia). Bilateral p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 11,724 participants (mean age: 69.8 years) were enrolled in the survey, representing 56.1 million noninstitutionalized U.S.A residents, of whom 982 (7.3%) had stroke (Table 1). The sex distribution was relatively even in the study, comprising 5740 (45.2%) men and 5984 (54.8%) women. Participants were categorized into stroke and non-stroke groups. The participants in the stroke group were more likely to be older, non-Hispanic white (77.7%), less educated (58.6%), and less physically active (52.7%) than those in the non-stroke group. Most participants in the stroke group had higher current smoking rates (14.6% vs. 10.6%) and were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or CHD than those in the non-stroke group. In addition, dietary VitB1 levels were higher in the non-stroke group than in the stroke group (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the NHANES study participants aged ≥ 60 years between 2003 and 2018a

| Characteristic | No. (%) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (N = 11,724) | Stroke | |||

| Yes (N = 982) | No (N = 10,742) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 69.8 (0.1) | 72.7 (0.3) | 69.6 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age group, years | < 0.001 | |||

| ≥ 80 | 2,156 (15.5) | 271 (28.3) | 1,885 (14.5) | |

| 70–79 | 3,741 (31.6) | 342 (36.2) | 3,399 (31.2) | |

| 60–69 | 5,827 (52.9) | 369 (35.5) | 5,458 (54.3) | |

| Sex | 0.70 | |||

| Female | 5,984 (54.8) | 472 (55.7) | 5,512 (54.7) | |

| Male | 5,740 (45.2) | 510 (44.3) | 5,230 (45.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.04 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 6,243 (79.8) | 547 (77.7) | 5,696 (80.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2,370 (8.4) | 232 (11.0) | 2,138 (8.2) | |

| Mexican American | 1,488 (4.0) | 94 (3.4) | 1,394 (4.1) | |

| Other Race | 1,623 (7.8) | 109 (7.9) | 1,514 (7.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.21 | |||

| < 25 | 2,937 (25.3) | 255 (25.7) | 2,682 (25.3) | |

| 25–29.9 | 4,308 (36.1) | 337 (32.6) | 3,971 (36.4) | |

| ≥ 30 | 4,479 (38.6) | 390 (41.8) | 4,089 (38.3) | |

| Marital | 0.55 | |||

| Married | 10,892 (94.4) | 914 (95.0) | 9,978 (94.4) | |

| Unmarried | 832 (5.6) | 68 (5.0) | 764 (5.6) | |

| Education | < 0.001 | |||

| > High school | 5,427 (56.0) | 368 (41.4) | 5,059 (57.2) | |

| ≤ High school | 6,297 (44.0) | 614 (58.6) | 5,683 (42.8) | |

| Physical activity | < 0.001 | |||

| Active | 6,671 (63.8) | 420 (47.3) | 6,251 (65.1) | |

| Inactive | 5,053 (36.2) | 562 (52.7) | 4,491 (34.9) | |

| Smoking status | 0.002 | |||

| Former | 4,656 (40.8) | 440 (44.0) | 4,216 (40.5) | |

| Never | 5,628 (48.4) | 392 (41.4) | 5,236 (48.9) | |

| Now | 1,440 (10.9) | 150 (14.6) | 1,290 (10.6) | |

| Diabetes | 3,774 (26.6) | 438 (42.3) | 3,336 (25.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 9,331 (76.8) | 878 (88.4) | 8,453 (75.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 9,649 (84.1) | 855 (88.6) | 8,794 (83.7) | 0.004 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,224 (10.8) | 206 (22.1) | 10,18 (9.9) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol intake, mean (SD), g/day | 6.4 (0.3) | 3.6 (0.5) | 6.6 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Energy intake, mean (SD), kcal/day | 1,857.1 (11.2) | 1685.7 (28.3) | 1870.6 (11.4) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B1 intake, mean (SD), mg/day | 1.5 (0.01) | 1.4 (0.03) | 1.5 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, SD Standard deviation

aAll estimates accounted for sampling weights, and all percentages were weighted

Continuous variables were compared through the t-test. Categorical variables were compared through the c2 test

Relationship between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke

To further explore the correlation between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk, we subsequently performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. According to the univariate analysis, stroke risk was strongly associated with age, education level, physical activity, alcohol intake, VitB1 intake, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and CHD. Among these variables, VitB1 intake (as continuous and categorical variables) was negatively correlated with stroke risk (both p < 0.05) (Additional File 1). In the multivariate analyses, three multivariate logistic regression models were developed: crude model, unadjusted; Model 1, adjusted for age, sex, and race; and Model 2, adjusted for all covariates. When VitB1 intake was used as a continuous variable, it was negatively associated with stroke risk. In the crude model and Model 1, the odds ratios (ORs) were 0.71 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61, 0.82) and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.61,0.84), respectively (Table 2). This result remained robust in Model 2 (OR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64, 0.89). Subsequently, all participants were divided into four groups based on their VitB1 intake (Q1–Q4), where Q1 was the lowest intake group, and Q4 was the highest intake group. In the crude model, the risk ratios and 95% CIs for stroke in Groups Q2, Q3, and Q4 compared with those in Q1 were 0.72 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.92), 0.61 (95% CI: 0.46, 0.81), and 0.58 (95% CI: 0.45, 0.73), respectively. This demonstrates a decreasing trend in stroke risk with increasing VitB1 intake in the crude model. This association remained stable in Models 1 and 2. In Model 2, VitB1 intake was significantly negatively associated with stroke risk, with an OR of 0.63 (95% CI: 0.48, 0.83). Thus, in Model 2, for each unit increase in VitB1 intake, stroke risk was reduced by 37% (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.83); that is, the higher the VitB1 intake, the lower the stroke risk.

Table 2.

Association between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke among study participants

| Characteristic | Crude modela | Model 1b | Model 2c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval (CI)) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| VitB1, mg/day | 0.71 (0.61, 0.82) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.61, 0.84) | < 0.001 | 0.75 (0.64, 0.89) | < 0.001 |

| VitB1 (mg/day, quartile) | ||||||

| Quartile 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Quartile 2 | 0.72 (0.56,0.92) | 0.01 | 0.73 (0.56, 0.93) | 0.01 | 0.75 (0.58, 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Quartile 3 | 0.61 (0.46,0.81) | < 0.001 | 0.61 (0.46, 0.81) | < 0.001 | 0.67 (0.49, 0.90) | 0.01 |

| Quartile 4 | 0.58 (0.45,0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.46, 0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.48, 0.83) | 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

Abbreviation: OR odds ratio, BMI body mass index, VitB1 vitamin B1

aUnadjusted

bAdjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity

cAdjusted for marital status, education level, alcohol intake, smoking status, BMI, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, and variables from Model 1

Dose–response association between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke

We performed RCS analyses using Model 2 to further illustrate the linear or nonlinear association between VitB1 intake and stroke (Fig. 2). The results demonstrated a negative association between VitB1 intake and stroke risk, with a dose‒response relationship, suggesting that stroke risk decreased with increasing VitB1 intake (p overall < 0.001, p nonlinearity = 0.23).

Fig. 2.

Association between dietary vitamin B1 intake and stroke in the restricted cubic spline analysis

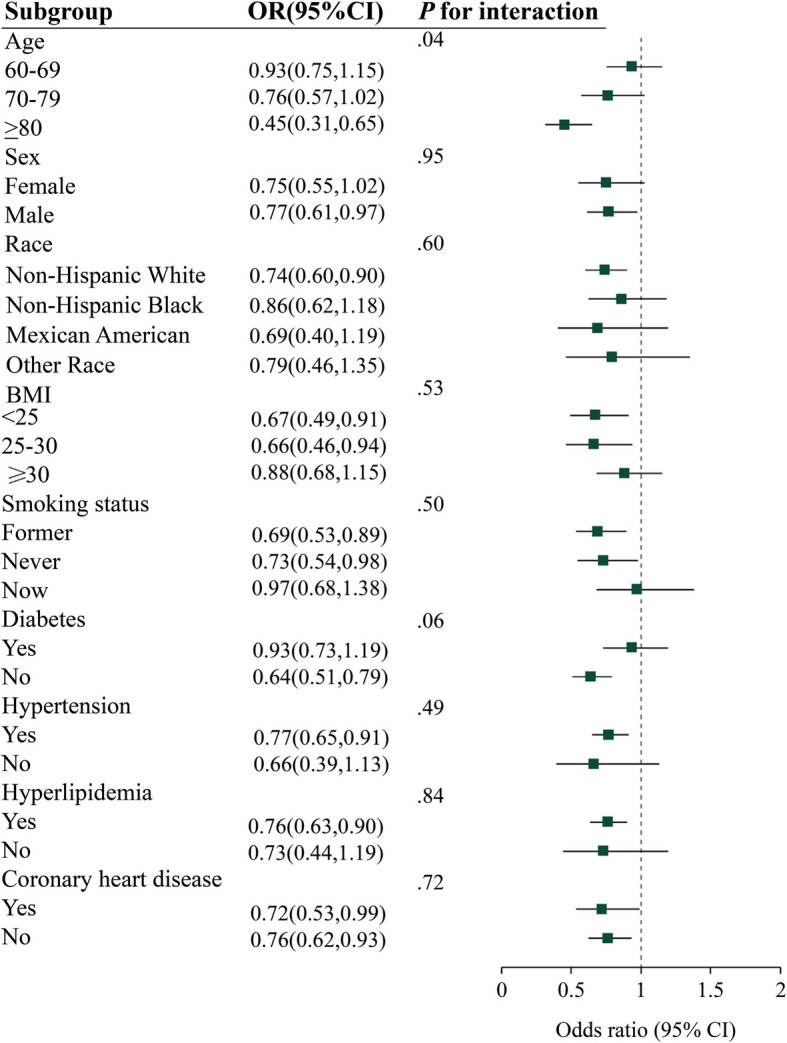

Subgroup analysis

Furthermore, we conducted subgroup analyses stratified by sex, age, race, and BMI, as well as smoking status, diabetes mellitus status, hypertension status, CHD status, and hyperlipidemia status, to explore potential correlations between VitB1 intake and stroke risk in different populations (Fig. 3). A negative correlation between VitB1 intake and stroke risk was observed among those aged ≥ 80 years or older, those who were male, those who were non-Hispanic white, those with a BMI of < 25 and 25–30 kg/m2, those who were former smokers, those with hypertensive disease, those with hyperlipidemia, those without CHD, and those without diabetes mellitus; however, no correlation was observed among the other subgroups of the stratified populations. Nevertheless, interaction tests revealed an interaction p-value of 0.04 in the age subgroup, indicating that the association between VitB1 and stroke is more pronounced in participants aged ≥ 80 years. No significant interactions were observed among the other subgroups, indicating no significant dependence of other covariates on this negative correlation.

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); OR, odds ratio. Forest plot showing the association between dietary vitamin B1 intake and stroke for various subgroups of participants aged ≥ 60 years in the 2003 to 2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to exclude participants who already had a stroke at the start of follow-up and those who had a stroke within the first year of follow-up. Additional File 2 presents the baseline characteristics of study participants included in the sensitivity analyses. According to the sensitivity analyses, dietary VitB1 intake (as continuous and categorical variables) was inversely correlated with stroke risk (Additional File 3). In Model 2, VitB1 intake as a continuous variable was negatively correlated with stroke risk (OR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.63, 0.89). When VitB1 was used as a categorical variable, compared with the lowest quartile, the highest quartile was significantly negatively correlated with stroke risk (OR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.83). Therefore, the findings of the sensitivity analysis were correlated with the results of the primary analysis, implying that the study’s findings are stable and reliable.

Discussion

In this survey, we examined the relationship between VitB1 intake and stroke risk in an American population aged ≥ 60 years. Our findings showed a strong negative correlation between VitB1 intake and stroke risk. RCS analysis revealed a linear relationship between VitB1 and stroke risk. Subgroup analyses revealed no interactions between VitB1 and stroke risk and sex, age, race, BMI, smoking status, diabetes status, hypertension status, CHD status, or hyperlipidemia status. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed to ensure the reliability of the findings. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population-based, large-scale survey to investigate the association between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk.

The most common central nervous system complication of VitB1 deficiency is Wernicke's encephalopathy [25]; however, its association with stroke has been poorly studied and reported. Recent evidence emphasizes the importance of nutritional supplementation in stroke rehabilitation, particularly in ameliorating malnutrition and supporting recovery [26]. Malnutrition is common in patients with stroke and is associated with functional impairment, increased complications and prolonged hospitalization [27]. Nutritional interventions, including supplementation with specific vitamins and minerals, have been shown to improve rehabilitation outcomes by enhancing neuroplasticity, reducing oxidative stress, and supporting energy metabolism [26]. An animal study showed that vitamin B supplementation was effective in promoting functional stroke recovery [28]. VitB1 is required for carbohydrate metabolism and energy production, which are critical for neuronal repair and recovery after stroke [17]. A retrospective cohort study involving 119 patients with stroke revealed that 63% had VitB1 deficiency. The authors speculated that low or low-to-normal plasma VitB1 levels are a risk factor for stroke and that oral administration of VitB1 is an effective means of increasing plasma VitB1 levels, which is critical to the nutritional needs of post-stroke rehabilitation [17]. Future studies should focus on randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of targeted nutritional interventions, including VitB1 supplementation, in stroke rehabilitation. These studies will provide more definitive evidence and inform clinical guidelines for nutritional support. Feng et al. [29] investigated the association between VitB1 deficiency and post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) in a prospective cohort survey. The findings of this investigation demonstrated that VitB1 deficiency was associated with PSCI. Additionally, by analyzing the original data, we found that the proportion of patients with stroke with VitB1 deficiency was as high as 45% (82 of 182), suggesting that VitB1 deficiency was related to stroke. Similarly, stroke symptoms have been reported in patients with thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia, and VitB1 supplementation significantly improves stroke symptoms, suggesting that VitB1 and the occurrence of stroke have a close pathological basis [30]. A large community prospective cohort study in Japan revealed that VitB1 intake was not correlated with stroke-related risk of death; however, the study did not determine whether it was associated with stroke incidence [16]. Consequently, large cohort surveys are required to further investigate the relationship between VitB1 and stroke risk.

The effects of hospitalization on physical functioning, particularly balance and coordination, have been investigated in previous studies [31, 32]. Older adults are inherently prone to VitB1 deficiency owing to physical decline, and hospitalization usually implies that they have poor health and may have multiple underlying diseases or have undergone surgery, compromising the metabolism, absorption, and utilization of VitB1 [31]. In addition, neurological dysfunction induced by VitB1 deficiency may cause decreased balance and coordination, increase the risk of accidents such as falls, prolong hospitalization, and affect the quality of life after hospital discharge [32].

Additionally, a few subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the effects of VitB1 intake in different populations. The relationship between VitB1 and stroke risk was more prominent in people aged ≥ 80 years. This may be because this age group (≥ 80 years) is at great risk of malnutrition and comorbidities, which increase their susceptibility to VitB1 deficiency [33]. A systematic assessment of micronutrient intake in community-dwelling older individuals showed that inadequate thiamine intake in this population is primarily attributable to absorption and utilization factors [34]. Subgroup analyses stratified by sex showed that an increased stroke risk owing to inadequate VitB1 intake was more likely to occur in the male population. A meta-analysis by Borg et al. revealed that men were more likely to be deficient in thiamine intake than women, leading to an increased stroke risk [34]. In our sensitivity analysis, participants who had a stroke at the start of follow-up and within the first year were excluded to investigate the association between VitB1 intake and stroke in the general population, and the results were consistent with the findings of the primary analysis.

Although the mechanisms underlying the correlation between dietary VitB1 and stroke risk are unknown, we proposed several hypotheses. First, VitB1 is a crucial coenzyme in carbohydrate metabolism and plays an essential role in the structure and function of neuronal and glial cell membranes [35, 36]. Therefore, VitB1 is important for normal brain function. Maintaining the normal function of nerve cells in the brain requires substantial energy; however, the brain does not readily store energy [37]. VitB1 largely contributes to carbohydrate metabolism and provides energy to nerve cells [4]. Therefore, VitB1 deficiency is associated with decreased glucose metabolism in the central nervous system [29], disrupting cellular homeostasis and ultimately leading to neuronal death [38]. Similarly, when nerve cells have energy supply disorders owing to VitB1 deficiency, they initiate glycolysis to meet their own high-energy needs, causing an increase in intracellular glycolytic metabolites [39, 40]. A meta-analysis of seven prospective cohort studies showed that glycolytic metabolites were associated with increased stroke risk (hazard ration: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.14) [40]. Further stratified analysis of stroke subtypes revealed that this association was particularly pronounced in patients with ischemic stroke, with a 13% increased risk for ischemic stroke per 1-SD increase in metabolites [40]. Moreover, excessive glycolysis fails to meet cellular energy requirements and leads to lactic acidosis and reactive oxygen species production, resulting in brain damage and an increased stroke risk [41]. Second, chronic VitB1 deficiency may alter endothelial cell function in the central nervous system [29]. A previous study revealed that VitB1 inhibits the proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells and ameliorates endothelial dysfunction, which is critical for atherosclerotic plaque formation [42]. A recent investigation demonstrated that VitB1, in the form of its coenzyme thiamine pyrophosphate, antagonizes P2Y6R activity and thus has an anti-atherosclerotic effect [43]. P2Y6R deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis and reduces plaque formation and aortic lipid deposition [43]. Another study revealed that after the routine use of VitB1, hemodynamic and endothelial functions were significantly improved, and vascular resistance was reduced, thereby slowing the development and progression of atherosclerosis, which is particularly crucial for preventing stroke risk [42, 44, 45]. Finally, VitB1 also has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and oxygen radical scavenging properties; therefore, VitB1 deficiency can expose cells to oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage and death and contributing to the development of stroke [4, 46]. Lukienko et al. [47] studied the antioxidant effects of VitB1 in rat liver microsomes and found that VitB1 prevented the production of several harmful substances that promote oxidative stress. Therefore, we speculate that the effect of insufficient VitB1 intake on stroke may be induced by different factors, the most important of which is atherosclerosis.

Metabolic disorders encompass various abnormalities in metabolic processes, including dysregulation in blood glucose, lipids, and blood pressure. From a physiological perspective, glucose metabolism disorders, such as diabetes or insulin resistance, significantly increase the level of oxidative stress, damaging the vascular endothelium, affecting the normal function of blood vessels, and altering the metabolic pathway and efficiency of VitB1 utilization in the body, which indirectly affect stroke risk. Therefore, when interpreting the results of this study regarding the relationship between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk, considering the influence of metabolic disorders as a confounding factor is essential. Future studies should investigate the specific mechanisms by which metabolic disorders affect metabolism and the effects of dietary VitB1 to provide more precise guidance for clinical practice. Similarly, confounding factors should be more rigorously designed and controlled in relevant epidemiologic studies to improve the accuracy and reliability of the results.

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively explore the association between dietary VitB1 intake and stroke risk in a large, nationally representative cohort of older adults in the United States. Our research employed a representative sample of the US population aged ≥ 60 years, providing robust epidemiological evidence of the protective role of VitB1 intake against stroke risk. Our findings not only reveal a robust linear negative association between VitB1 intake and stroke risk but also demonstrate the consistency of this relationship across diverse subgroups and in sensitivity analyses. By integrating epidemiological evidence with potential biological mechanisms, our study provides new insights into the preventive role of dietary VitB1 in stroke among the older individuals, highlighting an important and previously underexplored aspect of nutritional epidemiology.

This study has some limitations. First, because NHANES is a cross-sectional survey with inherent limitations, identifying confounders in the non-measured data was impossible. Second, VitB1 intake was estimated for a certain period through interviews based on the dietary structure table, which was subject to bias in recall and estimation and was not representative of long-term intake. We suggest that follow-up studies adopt more precise dietary assessment methods, such as combining multiple 24-h dietary review methods, food frequency questionnaires, or the use of biomarkers, to facilitate the assessment of dietary VitB1 intake. Third, the findings do not allow the establishment of causality; therefore, further prospective cohort studies are required for clarity. Fourth, because stroke events in the NHANES databank were obtained via questionnaires and were not determined through medical imaging or diagnosis, we could not discriminate between hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes. Fifth, although we attempted to account for hospitalization, the NHANES database does not directly include hospitalization as a variable, limiting the potential for a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of this factor. We are aware of the shortcomings of the analysis of this factor and hope to use this study as a basis for further improvement to accurately reveal the associations between VitB1 deficiency, hospitalization, homeostasis, and other health-related challenges in older adults and provide a more valuable reference for research in this area. Finally, our investigation was restricted to the American population. Although the design of this study considered age groups and multiple ethnicities, diets in different locations may significantly influence differences in VitB1 intake; thus, the applicability of these findings to other populations requires further investigation.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that lower dietary VitB1 intake was associated with a greater risk of stroke in older individuals. These findings suggest that inadequate thiamine intake may be an underrecognized risk factor for stroke in the older population. Given the biological plausibility and clinical relevance, future prospective studies should confirm these findings and explore the role of dietary interventions or supplementation in stroke prevention, particularly in populations at risk of vitamin B1 deficiency.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1. Weighted univariate analysis for stroke. Univariate analysis of the risk factors associated with stroke in NHANES included participants aged ≥60 years from 2003 to 2018

Additional file 2. Baseline characteristics of participants enrolled in the sensitivity analysis. The data records the baseline characteristics of participants in the sensitivity analysis

Additional file 3. Logistic regression analysis on the association between vitamin B1 intake and stroke in the sensitivity analysis. Logistic regression analysis on the association between vitamin B1 intake and stroke in the sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore how the level of vitamin B1 intake is related to the risk of stroke

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- VitB1

Vitamin B1

- MECs

Mobile examination centers

- BMI

Body mass index

- RCS

Restricted cubic spline

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- PSCI

Poststroke cognitive impairment

- Q

Quartile

- SD

Standard deviation

- IQR

Median and interquartile range

- CI

Confidence intervals

- OR

Odds ratio

Authors’ contributions

SZ was involved in conception and design of the study, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting of a significant portion of the manuscript and figures. ZC was responsible for acquisition and analysis of data and drafting of a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. LY was involved drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures. JC was responsible for acquisition and analysis of data. ZY revised the article. MY was involved in study conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Young and Middle-aged Teacher Education Research Project of Fujian Province (https://www.fjmu.edu.cn/) under Grant number JAT210093 to Shitu Zhuo. The funder had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NHANES repository, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This survey was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The NHANES protocol was approved by the NCHS ethics review committee (approval no. 98–12, 2005–06, 2011–17, 2018–01). All individuals who participated in the survey provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, Martins S, Sacco RL, Hacke W, et al. World Stroke Organization (WSO): global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:18–29. 10.1177/17474930211065917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:795–820. 10.1016/1474-4422(21)00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Feigin VL, Owolabi MO, World Stroke Organization–Lancet Neurology Commission Stroke Collaboration Group. Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: a world Stroke Organization-Lancet Neurology Commission. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:1160–206. 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mrowicka M, Mrowicki J, Dragan G, Majsterek I. The importance of thiamine (vitamin B1) in humans. Biosci Rep. 2023;43:BSR20230374. 10.1042/20230374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Qin J, Liu D, Wang Y, Shen X, Yang N, et al. Reduced thiamine binding is a novel mechanism for TPK deficiency disorder. Mol Genet Genomics. 2019;294:409–16. 10.1007/s00438-018-1517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sambon M, Wins P, Bettendorff L. Neuroprotective effects of thiamine and precursors with higher bioavailability: focus on Benfotiamine and dibenzoylthiamine. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22: 5418. 10.3390/ijms22115418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettendorff L. Synthetic thioesters of thiamine: promising tools for slowing progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24: 11296. 10.3390/ijms241411296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrs C, Lonsdale D. Hiding in plain sight: modern thiamine deficiency. Cells. 2021;10:2595. 10.3390/cells10102595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerns JC, Gutierrez JL. Thiamin. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:395–7. 10.3945/an.116.013979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE. Wernicke-Korsakoff-syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:507–16. 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott M, Werneke U. Wernicke’s encephalopathy — from basic science to clinical practice. Part 1: understanding the role of thiamine. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10: 2045125320978106. 10.1177/2045125320978106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J, Pan X, Fei G, Wang C, Zhao L, Sang S, et al. Correlation of thiamine metabolite levels with cognitive function in the non-demented elderly. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31:676–84. 10.1007/s12264-015-1563-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luong KVQ, Nguyen LTH. The impact of thiamine treatment in the diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4:153–60. 10.4021/jocmr890w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duc HN, Oh H, Yoon IM, Kim MS. Association between levels of thiamine intake, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and depression in Korea: a national cross-sectional study. J Nutr Sci. 2021;10: e31. 10.1017/jns.2021.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spence JD. Metabolic vitamin B12 deficiency: a missed opportunity to prevent dementia and stroke. Nutr Res. 2016;36:109–16. 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang C, Eshak ES, Shirai K, Tamakoshi A, Iso H. Associations of dietary intakes of vitamins B 1 and B 3 with risk of mortality from CVD among Japanese men and women: the Japan collaborative cohort study. Br J Nutr. 2023;129:1213–20. 10.1017/S0007114522001209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehsanian R, Anderson S, Schneider B, Kennedy D, Mansourian V. Prevalence of low plasma vitamin B1 in the stroke population admitted to acute inpatient rehabilitation. Nutrients. 2020;12:1034. 10.3390/nu12041034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanton CA, Moshfegh AJ, Baer DJ, Kretsch MJ. The USDA automated multiple-pass method accurately estimates group total energy and nutrient intake. J Nutr. 2006;136:2594–9. 10.1093/jn/136.10.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroll ME, Green J, Beral V, Sudlow CLM, Brown A, Kirichek O, et al. Adiposity and ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: prospective study in women and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;87:1473–81. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh NS, Chatterjee A, Díaz I, Merkler AE, Murthy SB, Iadecola C, et al. Trends in active cigarette smoking among stroke survivors in the United States, 1999 to 2018. Stroke. 2020;51:1656–61. 10.1161/.120.029084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1021–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2017;324:2018;71:1269. 10.1161/.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kammerlander AA, Mayrhofer T, Ferencik M, Pagidipati NJ, Karady J, Ginsburg GS, et al. Association of metabolic phenotypes with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in patients with stable chest pain. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:1038–45. 10.2337/dc20-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L, Shi Y, Kong C, Zhang J, Chen S. Dietary inflammatory index and its association with the prevalence of coronary heart disease among 45,306 US adults. Nutrients. 2022;14:4553. 10.3390/nu14214553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:442–55. 10.1016/1474-4422(07)70104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko SH, Shin YI. Nutritional supplementation in stroke rehabilitation: a narrative review. Brain Neurorehabil. 2022;15:e3. 10.12786/bn.2022.15.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honaga K, Mori N, Akimoto T, Tsujikawa M, Kawakami M, Okamoto T, et al. Investigation of the effect of nutritional supplementation with whey protein and vitamin D on muscle mass and muscle quality in subacute post-stroke rehabilitation patients: a randomized, single-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2022;14:685. 10.3390/nu14030685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jadavji NM, Emmerson JT, MacFarlane AJ, Willmore WG, Smith PD. B-vitamin and choline supplementation increases neuroplasticity and recovery after stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;103:89–100. 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng L, He W, Huang G, Lin S, Yuan C, Cheng H, et al. Reduced thiamine is a predictor for cognitive impairment of cerebral infarction. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01709. 10.1002/brb3.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elavarasi A, Haq TM, Thahira T, Bineesh C, Kancharla LB. Acute ischemic stroke due to multiple bee stings_a delayed complication. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23:135–6. 10.4103/aian.AIAN_118_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Keeffe ST, Tormey WP, Glasgow R, Lavan JN. Thiamine deficiency in hospitalized elderly patients. Gerontology. 1994;40:18–24. 10.1159/000213570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mates E, Alluri D, Artis T, Riddle MS. A retrospective case series of thiamine deficiency in non-alcoholic hospitalized veterans: an important cause of delirium and falling? J Clin Med. 2021;10:1449. 10.3390/jcm10071449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DC, Chu J, Satz W, Silbergleit R. Low plasma thiamine levels in elder patients admitted through the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1156–9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ter Borg S, Verlaan S, Hemsworth J, Mijnarends DM, Schols JMGA, Luiking YC, et al. Micronutrient intakes and potential inadequacies of community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1195–206. 10.1017/0007114515000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bâ A. Metabolic and structural role of thiamine in nervous tissues. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:923–31. 10.1007/s10571-008-9297-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng Y, Yong Y, Yang G, Ding H, Fan Z, Tang Y, et al. Autophagy alleviates neurodegeneration caused by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. J Neurochem. 2013;126:805–18. 10.1111/jnc.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonvento G, Bolaños JP. Astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation shapes brain activity. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1546–64. 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie J, Kittur FS, Li PA, Hung CY. Rethinking the necessity of low glucose intervention for cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:1397–403. 10.4103/1673-5374.330592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo S, Wehbe A, Syed S, Wills M, Guan L, Lv S, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism and potential effects on endoplasmic reticulum stress in stroke. Aging Dis. 2023;14:450–67. 10.14336/.2022.0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vojinovic D, Kalaoja M, Trompet S, Fischer K, Shipley MJ, Li S, et al. Association of circulating metabolites in plasma or serum and risk of stroke: meta-analysis from 7 prospective cohorts. Neurology. 2021;96:e1110–23. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo S, Cosky E, Li F, Guan L, Ji Y, Wei W, et al. An inhibitory and beneficial effect of chlorpromazine and promethazine (C + P) on hyperglycolysis through HIF-1α regulation in ischemic stroke. Brain Res. 2021;1763: 147463. 10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avena R, Arora S, Carmody BJ, Cosby K, Sidawy AN. Thiamine (vitamin B1) protects against glucose- and insulin-mediated proliferation of human infragenicular arterial smooth muscle cells. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:37–43. 10.1007/s100169910007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Zhou M, Li H, Dai C, Yin L, Liu C, et al. Macrophage P2Y6 receptor deletion attenuates atherosclerosis by limiting foam cell formation through phospholipase Cβ/store-operated calcium entry/calreticulin/scavenger receptor A pathways. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:268–83. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora S, Lidor A, Abularrage CJ, Weiswasser JM, Nylen E, Kellicut D, et al. Thiamine (vitamin B1) improves endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in the presence of hyperglycemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 2006;20:653–8. 10.1007/s10016-006-9055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen H, Niu X, Zhao R, Wang Q, Sun N, Ma L, et al. Association of vitamin B1 with cardiovascular diseases, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US adults. Front Nutr. 2023;10: 1175961. 10.3389/fnut.2023.1175961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kartal B, Palabiyik B. Thiamine leads to oxidative stress resistance via regulation of the glucose metabolism. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-Le-Grand). 2019;65:73–7. 10.14715/cmb/2019.65.1.13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lukienko PI, Mel’nichenko NG, Zverinskii IV, Zabrodskaya SV. Antioxidant properties of thiamine. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2000;130:874–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Weighted univariate analysis for stroke. Univariate analysis of the risk factors associated with stroke in NHANES included participants aged ≥60 years from 2003 to 2018

Additional file 2. Baseline characteristics of participants enrolled in the sensitivity analysis. The data records the baseline characteristics of participants in the sensitivity analysis

Additional file 3. Logistic regression analysis on the association between vitamin B1 intake and stroke in the sensitivity analysis. Logistic regression analysis on the association between vitamin B1 intake and stroke in the sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore how the level of vitamin B1 intake is related to the risk of stroke

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NHANES repository, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.