Abstract

Background

Proton therapy is commonly used for treating hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); however, its feasibility can be challenging to assess in large tumors or those adjacent to critical organs at risk (OARs), which are typically assessed only after planning computed tomography (CT) acquisition. This study aimed to predict proton dose distributions using diagnostic CT (dCT) and diagnostic MRI (dMRI) with a convolutional neural network (CNN), enabling early treatment feasibility assessments.

Methods

Dose distributions and dose-volume histograms (DVHs) were calculated for 118 patients with HCC using intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) and passive proton therapy. A CPU-based CNN model was used to predict DVHs and 3D dose distributions from diagnostic images. Prediction accuracy was evaluated using mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), structural similarity index (SSIM), and gamma passing rate with a 3 mm/3% criterion.

Results

The predicted DVHs and dose distributions showed high agreement with actual values. MAE remained below 3.0%, with passive techniques achieving 1.2–1.8%. MSE was below 0.004 in all cases. PSNR ranged from 24 to 28 dB, and SSIM exceeded 0.94 in most conditions. Gamma passing rates averaged 82–83% for IMPT and 92–93% for passive techniques. The model achieved comparable accuracy when using dMRI and dCT.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that early dose distribution prediction from diagnostic imaging is feasible and accurate using a lightweight CNN model. Despite anatomical variability between diagnostic and planning images, this approach provides timely insights into treatment feasibility, potentially supporting insurance pre-authorization, reducing unnecessary imaging, and optimizing clinical workflows for HCC proton therapy.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Proton therapy, Convolutional neural network, Dose volume histogram, Dose distribution, Diagnostic imaging, Intensity-modulated proton therapy, Passive methods

Background

Advancements in high-precision radiation techniques for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have enabled precise delivery to target volumes while minimizing exposure to healthy tissues. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has been shown to achieve local control rates of over 85% in patients with early-stage HCC [1]. Similarly, proton therapy has revealed superiority in sparing normal liver tissues while delivering a high dose to the tumor, reducing the risk of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) in patients with poor liver function [2, 3]. Radiation therapy is often considered when other standard treatments, such as resection, are not feasible. For example, portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) often limits surgical options, as it can significantly impair liver function and increase the risk of postoperative liver failure. Similarly, patients with advanced comorbidities, such as cirrhosis or severe cardiac conditions, may not tolerate the stress of surgery. These limitations highlight the importance of radiation therapy as a less invasive yet effective alternative for achieving local control in HCC [4, 5].

In radiation therapy for HCC, an effective balance between liver damage and dose distribution is critical for successful treatment. Intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) or passive irradiation with a range compensator and collimator formation are used in proton therapy [6–8] and allow precise targeting of the tumor while minimizing the dose to surrounding liver tissues and critical structures.

However, radiation therapy may not be feasible when large tumors or critical organs at risk (OARs) are near the target, making it impossible to meet dose constraints for the normal liver or other OARs, even with planning computed tomography (CT) imaging. In such cases, patient radiation exposure from planning CT imaging and the staff effort required for treatment planning may become unjustified.

In response to these challenges, we focused on convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Recent advancements in automated treatment planning using CNN have shown promise in addressing the challenges of dose distribution prediction [9, 10]. Algorithms like U-Net and its derivatives have been widely used to predict dose distributions. However, they often require expensive equipment with Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) capabilities [11, 12], which has limited their widespread adoption in many clinical settings.

This study aimed to predict dose distributions using CNNs with a general-purpose central processing unit (CPU) from existing diagnostic CT (dCT) and diagnostic magnetic resonance image (dMRI) taken before the implementation of planning CT. This enables the possibility of executing dose distribution predictions on commonly available terminals, such as those used for electronic medical records, allowing radiation treatment dose distributions to be presented to patients and facilitating decision-making without relying on planning CT. This approach can help reduce unnecessary patient exposure and alleviate the workload of treatment planning staff, positioning it as an application of diagnostic imaging in proton therapy.

Additionally, proton therapy is often associated with high costs and typically requires pre-authorization from insurance providers before treatment can proceed. This approval process can cause significant delays, especially if the dosimetric advantages of proton therapy over photon therapy are not clearly demonstrated in advance. Early prediction of dose distributions using diagnostic imaging could support pre-approval efforts and help avoid delays in initiating treatment, thereby improving the patient care workflow.

Methods

Data acquisition

The study included 118 patients diagnosed with HCC and fewer than three metastases who underwent passive proton therapy between 2021 and 2024. Treatment planning CT images for each patient were acquired using the Aquilion ONE™ system (Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Japan). The prescribed doses were categorized into three groups: 66 [Gy]/10 fractions for the peripheral type, 72.6–76 [Gy]/20–22 fractions for the hilar type, and 74–76 [Gy]/37–38 fractions for the gastrointestinal proximity type in 35, 79, and 4 patients, respectively [13–15].

All treatment plans were designed to ensure that the D90% of the Clinical Target Volume (CTV) was covered by 100% of the prescribed dose. Different treatment planning systems (TPSs) were used for each irradiation type: Eclipse (version 16.0, Varian Medical Systems, Inc.) was used for IMPT, and an in-house developed system, SGI_TPS (version 2.0, Sumitomo Heavy Industries, Ltd.), was used for passive proton therapy planning.

For passive irradiation plans used in actual clinical treatments, a distal margin of 4 mm was applied to ensure adequate dose coverage to the CTV, and a lateral margin of 7.5 mm was added to compensate for smearing effects.

IMPT plans were created with the same prescribed doses and beam angles as those used for passive irradiation. These plans, generated using line scanning, were robustly optimized using Eclipse’s built-in robust settings, incorporating a 5 mm setup uncertainty and a ± 3.5% range uncertainty.

Next, contours were delineated on dCT and dMRI images acquired within approximately two weeks before or after the planning CT scan. The dCT scans were obtained using an Aquilion One system, and the dMRI scans were acquired using a 1.5-T diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). First, deformable image registration (DIR) was performed using MIM Maestro (version 7.2.9, MIM Software, Inc.) to align the planning CT with the dCT and dMRI. Based on the resulting deformation field, the target structures—Gross Tumor Volume (GTV) and CTV—delineated on the planning CT were automatically transferred to the dCT and dMRI.

The dose distributions used in this study were all calculated on the original planning CT using the clinical treatment planning system. No reoptimization or recalculation was performed on the dCT or dMRI. Instead, only the geometric information derived from the registered contours on the dCT and dMRI was used for model prediction. Synthetic CT images were not generated for MRI.

All contours were then reviewed and, if necessary, manually adjusted by a radiation oncologist. The structures used in this study included the GTV, CTV, normal liver, duodenum, and bile duct. Patient data were divided into 100 training sets and 18 test sets.

Prediction of dose volume histogram and dose distribution using CNN

Overview of the CNN model for DVH

As the initial step in predicting the dose distribution, a 1-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D CNN) was used to predict the DVH. This approach improved the accuracy of the predicted dose distribution by first predicting the DVH and incorporating it into the prediction flow of the dose distribution. Figure 1A illustrates the architecture and inference process of CNN1 used for this purpose.

Fig. 1.

A Workflow of CNN1 Models for Predicting DVH (Inference Phase) The model predicts DVHs from geometric parameters derived from diagnostic images during the inference phase. B Workflow of CNN2 for 3D Dose Distribution Prediction (Inference Phase). CNN2 predicts 3D dose distributions from geometric and predicted DVH data during the inference phase

For each patient, the prescribed dose [Gy] and the regions of interest (ROIs) delineated on the planning CT were used to extract the following ten geometric parameters: prescribed dose, liver segment number (Couinaud classification), major axis length [cm] and volume [cm3] of the GTV, percentage of the liver occupied by the GTV, Dice coefficient between the liver and GTV, Hausdorff distance [cm], mean surface distance [cm] between liver and GTV, and the shortest distances [cm] between the GTV and the duodenum and bile duct. These were used to form the explanatory variable vector (Train_item).

For inference, ten geometric parameters derived from contours on dCT and dMRI were used as Test_item. These were input into the trained CNN1 to predict DVHs for test patients. The network receives one-dimensional Test_item data, reshapes it for convolutional processing, and applies Conv1D and MaxPooling layers for feature extraction. After flattening, the features are passed through dense layers to generate one-dimensional DVH predictions, which are reshaped into their original two-dimensional format. This framework enables clinicians to obtain DVHs by contouring targets and OARs on dCT or dMRI alone, without needing a planning CT.

CNN architecture for DVH

The CNN1 model for DVH prediction consists of an input layer, followed by convolutional and dense layers. The input is a one-dimensional vector of geometric features (e.g., tumor size, organ distances), which is reshaped into a two-dimensional format to allow compatibility with Conv1D operations. Although the input is not image data, reshaping enables the model to apply localized feature transformations across the feature dimension using convolutional layers with a kernel size of 1, preserving positional relationships. Each convolutional layer uses a ReLU activation function, followed by max-pooling to reduce dimensionality and enhance computational efficiency.

The extracted feature maps are then flattened and passed through multiple dense layers with progressively fewer neurons to refine feature representations. Preliminary experiments showed that including Conv1D layers improved both generalization and convergence compared to using only dense layers. The final output layer employs a linear activation function to predict DVH values directly.

The model was implemented using Python with TensorFlow/Keras and trained using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001) with mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. Although not used in the loss calculation, additional evaluation metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE) and the coefficient of determination (R2 score) were monitored during training and validation to assess prediction performance. Of the 100 training patients, 85% were used for training and 15% for validation. The best model was selected based on the lowest validation MSE. No image preprocessing was required, as the model does not use image data. The lightweight 1D CNN architecture enables efficient training and inference on standard CPU-based systems without the need for specialized hardware.

Evaluate the predicted DVH

To evaluate the predicted DVHs for the normal liver, duodenum, and bile duct, dose differences between the predicted and actual DVHs (calculated using the TPS) were measured at 10% intervals across the range from 10 to 100% of the prescription dose. Additionally, clinically important metrics derived from the DVHs, including V30% for the normal liver and D1cc % for the duodenum and bile duct, were compared between the predicted and actual values. The V30 metric represents the proportion of liver volume receiving at least 30 [Gy] and is critical for assessing the risk of RILD. The D1cc metrics for the duodenum and bile duct indicate the maximum dose delivered to the most exposed 1 cm3 volume, providing insight into the potential for radiation-induced toxicity.

To determine whether statistically significant differences exist between predicted and actual values, paired two-tailed t-tests were performed for each dose point at 10% intervals and for clinical indices. The t-test was selected because it is a standard statistical method for comparing means of paired samples under the assumption that the differences follow a normal distribution. A p-value threshold of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Overview of the CNN model for dose distribution

In the next step, the input for CNN2 was created by concatenating Train_item with Train_DVH, which includes DVH data for the three ROIs. Using the RT_dose data in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format from the treatment plans derived by the TPS, the intensity and position information of the dose distribution were obtained. These were defined as Train_dose. CNN2 was constructed using both the concatenated input of Train_item and Train_DVH, and the corresponding Train_dose as explanatory data. By inputting the Test_item from the test group and the predicted DVH by CNN1, a 3D dose distribution (predicted dose) that corresponds to the predicted DVH was generated. The architecture of CNN2 is shown in Fig. 1B.

Using CNN1 and CNN2, this study derives the dose distribution from the positional information of contours obtained from images. Therefore, it enables the prediction of dose distribution and DVH from dCT and dMRI, regardless of image signal values, allowing for treatment feasibility assessment.

CNN architecture for dose distribution

In the next step, a second model, CNN2, was constructed to predict three-dimensional dose distributions. During training, a combined input vector was created by concatenating Train_item with the DVH data of the three OARs (Train_DVH). RT_dose data in DICOM format, which contains the spatial dose information calculated by the TPS, was extracted and reshaped to form the target output (Train_dose). To reduce computational load, the RT_dose data was downsampled by a factor of 4 in each spatial dimension (x, y, z) using trilinear interpolation. This resulted in a lower-resolution dose matrix that preserved the overall dose distribution pattern while significantly improving processing efficiency. CNN2 was trained using the combined input of Train_item and Train_DVH, along with the corresponding Train_dose.

During inference, Test_item and the predicted DVH from CNN1 were concatenated to form the input to CNN2. This combined input was reshaped and processed through a sequence of Conv1D and MaxPooling1D layers for feature extraction. The features were then passed through dense layers, and the final output was reshaped into a three-dimensional format representing the predicted dose distribution.

By utilizing CNN1 and CNN2 together, the system enables DVH and dose distribution predictions using only the positional information of contours from dCT or dMRI, without requiring actual planning CT images. This architecture facilitates real-time feasibility assessments in clinical settings.

Evaluate the predicted dose distribution

We predicted the dose distributions for the patients in the test group using CNN1 and CNN2. To evaluate the accuracy of these predictions, the predicted and actual dose distributions were compared using the cumulative dose projection (CDP). CDP represents the sum of dose distributions across the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, providing a comprehensive visualization of the dose distribution. The MAE, MSE, peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) [16, 17], and structural similarity index (SSIM) [18] were calculated for each CDP. The formulas for MAE and MSE are defined as follows:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where N is the total number of pixels in the dose distribution map, is the actual dose distribution and is the predicted dose distribution.

The formulas for calculating PSNR and SSIM are shown in Eqs. (3) and (4):

| 3 |

| 4 |

Here, “MAX” represents the maximum value of the dose distribution (normalized to 1). are the mean values of the actual dose distribution image arrayxand the predicted dose distribution image array , respectively. are the variances of and , respectively, and is the covariance. C1 and C2 are stabilization constants.

In addition to these quantitative image similarity metrics, we performed a 3D gamma analysis to evaluate the spatial and dosimetric agreement between the predicted and actual dose distributions. The gamma analysis was performed using the 3%/3 mm criteria with a 10% dose threshold.

By incorporating the results of the 3D gamma analysis alongside MAE, MSE, PSNR, and SSIM, we achieved a comprehensive and multidimensional evaluation of the predicted dose distributions. MAE and MSE respectively quantify the absolute and squared differences between the predicted and actual values, while PSNR and SSIM provide insights into the perceptual and structural fidelity of the predicted images. The gamma analysis adds a clinically relevant perspective by evaluating spatial agreement within acceptable tolerances. Collectively, these metrics offer a robust and well-rounded assessment of the prediction performance of CNN1 and CNN2 in reproducing clinically realistic dose distributions.

Results

Predicted DVH

Figure 2 presents the average DVHs predicted from each imaging modality using IMPT and passive proton techniques across all test patients. The solid lines represent the actual DVHs, and the dashed lines represent the predicted DVHs. Error bars visually represent inter-patient variability. Visually, the predicted DVHs closely matched the actual measurements. Tables 1 compare the predicted and calculated dose differences at D1cc %, and normal liver V30% for all test patients. The tables summarize the mean values, standard deviations, and p-values for the predicted indicators. IMPT and Passive predicted from dCT are denoted as dCT_IMPT and dCT_Passive, respectively, while those predicted from dMRI are referred to as dMRI_IMPT and dMRI_Passive.

Fig. 2.

Average DVHs for the normal liver, duodenum, and bile duct across all test patients, predicted from both dCT and dMRI using IMPT and passive proton techniques. The solid lines represent the actual DVHs, and the dashed lines represent the predicted DVHs. The DVHs show good agreement, confirming that the predicted values visually match the true values closely

Table 1.

Comparison of Predicted and Actual Dose Metrics (D1cc and V30) for All Test Patients

| dCT | dMRI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1cc [%] | V30 [%] | D1cc [%] | V30 [%] | ||

| IMPT | Normal liver | − 4.54 | 0.58 | − 4.58 | 0.57 |

| SD | 4.67 | 1.71 | 5.20 | 2.09 | |

| p-Value | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.31 | |

| Duodenum | − 1.64 | − 0.67 | |||

| SD | 2.97 | 2.26 | |||

| p-Value | 0.03 | 0.29 | |||

| Bile duct | − 1.01 | 0.12 | |||

| SD | 5.57 | 3.93 | |||

| p-Value | 0.45 | 0.92 | |||

| D1cc [%] | V30 [%] | D1cc [%] | V30 [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive | Normal liver | − 2.21 | 1.05 | − 1.37 | − 0.12 |

| SD | 2.97 | 1.56 | 2.18 | 2.16 | |

| p-Value | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.83 | |

| Duodenum | 1.05 | − 0.82 | |||

| SD | 9.84 | 2.69 | |||

| p-Value | 0.48 | 0.22 | |||

| Bile duct | − 1.98 | − 0.12 | |||

| SD | 3.29 | 2.90 | |||

| p-Value | 0.03 | 0.87 |

Mean differences, standard deviations, and p-values for D1cc [%] (duodenum and bile duct) and V30 [%] (normal liver) between predicted and actual DVHs across all imaging modalities and proton therapy techniques

For dCT_IMPT for the normal liver, the maximum difference was 1.84 ± 2.75% at the 100% dose, with an average difference of 2% and a standard deviation of 3%. For the duodenum, the maximum difference was 0.38 ± 2.60% at the 10% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 3%. For the bile duct, the maximum difference was 0.95 ± 3.31% at a 30% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 3% above 40%. The D1cc % ranged from -1.28% to -4.51% (standard deviation, 4.29–5.76%).

For dCT_Passive, the maximum difference in the normal liver was 0.17 ± 2.40% at the 40% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 3%. For the duodenum, the maximum difference was 1.21 ± 4.24% at the 10% dose, with an average difference within 2% and a standard deviation within 2% above 20%. For the bile duct, the maximum difference was 0.69 ± 5.02% at the 20% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 2% above 30%. The D1cc % ranged from 1.05% to -2.21% (standard deviation, 2.97–9.84%).

For dMRI_IMPT, the normal liver showed a maximum difference of 0.38 ± 2.25% at the 100% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 3%. For the duodenum, the maximum difference was 0.31 ± 1.15% at the 60% dose, with an average difference within 1% and a standard deviation within 2%. For the bile duct, the maximum difference was 1.04 ± 4.89% at the 20% dose, with an average difference within 2% and a standard deviation within 3% above 70%. The D1cc % ranged from 0.12% to − 4.58% (standard deviation, 2.26–5.20%).

For dMRI_Passive, the normal liver exhibited a maximum difference of 0.16 ± 2.47% at the 100% dose, with an average difference within 1% across all doses and a standard deviation within 3%. For the duodenum, the maximum difference was 1.38 ± 4.39% at the 10% dose, with an average difference within 2% and a standard deviation greater than 2% above 20%. For the bile duct, the maximum difference was 1.13 ± 4.36% at the 20% dose, with an average difference under 2% and a standard deviation above 30%. The D1cc % ranged from − 0.12% to − 1.37% (standard deviation, 2.18–2.90%).

The DVHs predicted based on contours delineated on dCT and dMRI showed no significant differences in the average DVH differences at 10% dose intervals or in the normal liver V30% when compared to those derived from planning CT for both IMPT and passive proton therapy techniques. However, significant p-values (≤ 0.05) were observed in the D1cc % dose differences for some OARs.

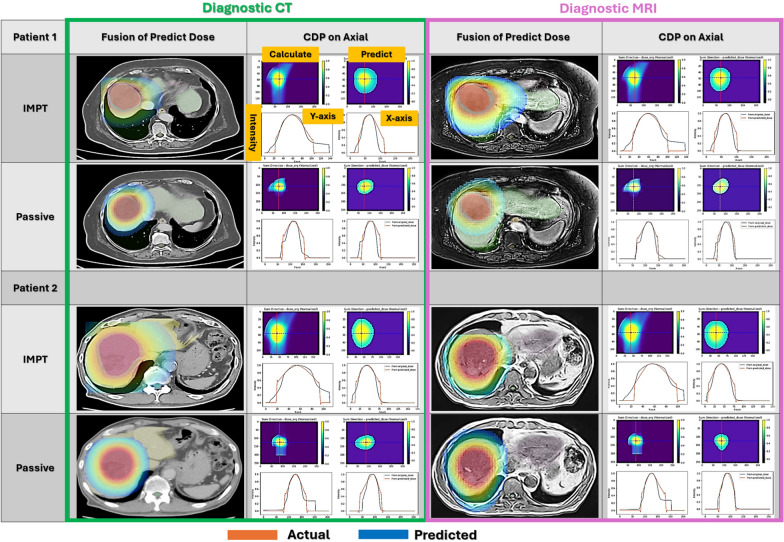

Predicted dose

The comparison of dose distributions was performed using CDP, calculated in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, by comparing the predicted and calculated values. Figure 3 displays the three-dimensional dose distributions of IMPT and passive proton therapy predicted from contours on both dCT and dMRI, along with the CDP in the axial plane. The fused images of the predicted dose distributions demonstrate that the targets are well covered across all combinations of dCT and dMRI, as well as IMPT and passive proton therapy. In the axial CDP calculated from both the predicted and calculated dose distributions, signal values along the same lines on both the X- and Y-axes were observed to be generally consistent.

Fig. 3.

Predicted dose distribution maps for two test patients. These three-dimensional dose distributions were predicted using IMPT and passive irradiation techniques on dCT and dMRI. The CDPs were calculated by integrating dose distributions across the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. The true and predicted values are compared on the X and Y axes at the marked lines in the images

The mean values and standard deviations of MAE, MSE, PSNR, and SSIM derived from the CDPs for all test patients are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluation metrics for predicted dose distribution maps

| dMRI_IMPT | dCT_IMPT | dMRI_Passive | dCT_Passive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE [%] | Axial | Average | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| SD | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Sagittal | Average | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | |

| SD | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Coronal | Average | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

| SD | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | ||

| MSE [%] | Axial | Average | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| SD | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| Sagittal | Average | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| SD | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| Coronal | Average | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| SD | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| PSNR [dB] | Axial | Average | 25.798 | 25.744 | 27.265 | 26.972 |

| SD | 2.055 | 2.086 | 2.003 | 1.925 | ||

| Sagittal | Average | 26.346 | 26.814 | 26.200 | 27.742 | |

| SD | 2.644 | 1.946 | 2.409 | 2.547 | ||

| Coronal | Average | 24.190 | 24.870 | 25.812 | 25.978 | |

| SD | 1.657 | 1.592 | 1.920 | 2.499 | ||

| SSIM (unitless) | Axial | Average | 0.920 | 0.919 | 0.957 | 0.955 |

| SD | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.012 | ||

| Sagittal | Average | 0.937 | 0.940 | 0.954 | 0.959 | |

| SD | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.017 | ||

| Coronal | Average | 0.898 | 0.902 | 0.945 | 0.943 | |

| SD | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.024 |

CDPs in the axial, sagittal, and coronal directions were calculated from the dose distributions predicted for each irradiation type based on the dCT and dMR images of all patients. To evaluate consistency from the CDPs, MAE [%], MSE [%], PSNR [dB], and SSIM (unitless) were calculated, and their mean values and standard deviations are shown

The MAE remained below 3.0% across all results. In particular, for passive proton therapy, the MAE ranged from 1.2 to 1.8%, demonstrating highly consistent reproducibility.

The MSE was generally below 0.004, which is comparable to values reported in previous studies using deep learning for dose distribution prediction and is considered clinically acceptable based on expert evaluations [19]. For IMPT, the highest MSE was observed in the coronal direction for both dMRI- and dCT-based predictions. The sagittal direction for dMRI_IMPT also showed slightly higher standard deviation, suggesting greater inter-patient variability in that plane.

The PSNR in this study ranged from 24 to 28 dB. While a PSNR above 30 dB is typically considered ideal for general image fidelity, PSNR values in the 25–30 dB range have been observed in studies generating clinically relevant maps for proton radiotherapy. For instance, in deep learning-based generation of relative stopping power maps from cone-beam CT for proton radiotherapy, a mean PSNR of 26.80 ± 1.48 dB has been reported, suggesting clinical utility within this range [20]. Similarly, for MRI-based treatment planning using deep learning-based synthetic CT generation for liver proton radiotherapy, an average PSNR of 22.65 ± 3.63 dB was reported, with subsequent dosimetric validation demonstrating high gamma analysis passing rates and small dose-volume histogram differences, indicating clinical acceptability even at these PSNR values [21]. These findings suggest that PSNR values in the 25–30 dB range can be considered clinically acceptable within the context of radiotherapy planning. Passive proton therapy yielded the highest PSNR values across all views, demonstrating strong resemblance to the original dose distributions. In contrast, for IMPT, the dose distributions predicted from both dCT and dMRI tended to show slightly lower PSNR values in the coronal direction, indicating a slight decline in reproducibility.

Based on the SSIM results, passive proton therapy demonstrated high structural similarity across all directions, with all values exceeding 0.94, indicating excellent structural reproducibility. In contrast, IMPT showed a slightly lower trend overall, though all SSIM values still exceeded 0.89, with the coronal direction suggesting slightly reduced structural reproducibility.

The 3D gamma analysis also demonstrated consistently favorable passing rates in passive proton therapy. The results are shown in Fig. 4. The mean ± standard deviation of the gamma passing rates across all test patients were 82.39 ± 5.63% for IMPT_dCT, 83.04 ± 5.92% for IMPT_dMRI, 92.96 ± 3.10% for Passive_dCT, and 92.02 ± 3.60% for Passive_dMRI. Passive proton therapy consistently demonstrated higher passing rates with smaller variability, further supporting the robustness of the predictions. In contrast, IMPT results were approximately 10% lower than those for passive techniques.

Fig. 4.

Gamma passing rates (3 mm/3%) for predicted dose distributions across all test patients. The mean ± standard deviation were 82.39 ± 5.63% for IMPT_dCT, 83.04 ± 5.92% for IMPT_dMRI, 92.96 ± 3.10% for Passive_dCT, and 92.02 ± 3.60% for Passive_dMRI

On the other hand, the entire process—from automatic contouring to DVH prediction and dose distribution completion—can be accomplished in approximately 30 min. This means that by simply delineating contours on existing images, the predicted dose distribution can be presented to the patient within 30 min, allowing for a timely assessment of treatment feasibility.

Discussion

In this study, a 1D CNN model in two steps was developed based on contours from two modality images, existing DVH, and dose distributions. The process involved predicting the DVH and dose distribution. We envisioned this model to assist oncologists during initial consultations, using a standard CPU-based PC for displaying medical records. While 2D or higher-dimensional CNNs may enhance prediction accuracy, they require longer computation times and expensive PCs equipped with GPUs [22]. This was the reason for adopting the 1D CNN model.

However, handling large-volume 3D images such as CT and MRI can potentially degrade PC performance, so it is essential to minimize the dataset size as much as possible [23]. Therefore, we successfully predicted dose distributions without using full 3D image data by relying solely on geometric parameters such as tumor size and the distances between the target and nearby OARs, which were extracted from contour information. Furthermore, the RT_Dose, a three-dimensional array used as ground truth, was downsampled to one-fourth of its original size in each dimension. Although this reduction could potentially compromise the accuracy required for clinical use, our results demonstrated visually and quantitatively that sufficient accuracy was maintained.

Additionally, we found that predicting the DVH first and then using it to guide dose distribution prediction resulted in smaller errors for both the DVH and the final dose distribution, compared to the approach of directly predicting the dose distribution and deriving the DVH afterward.

Based on Fig. 2 and Table 1, comparisons between the ground truth and the DVHs of OARs predicted from contours delineated on dCT and dMRI for both IMPT and passive methods showed no statistically significant differences across the dose range from 10 to 100% of the prescription dose. However, for D1cc, the mean error ranged from − 4.5% to + 1.0% across all cases, with large variations in standard deviation, resulting in statistically significant differences. These discrepancies are thought to arise in small high-dose regions exceeding the prescription dose, which are known to be random in nature and difficult to predict accurately [24]. Nguyen et al. conducted a study using a GPU-based U-Net deep learning model to predict dose distributions for prostate cancer IMRT plans from organ contour information. Their results showed that agreement in the peak dose areas was poorer compared to other dose regions [25].

Moreover, an error of < 5% in D1cc is unlikely to pose a significant issue when making clinical decisions about whether to proceed with treatment. However, achieving closer agreement may be possible by incorporating information that strongly influences low-dose distributions—such as beam angles—as well as treatment planning factors that vary based on the tumor location, including smearing, proximal/distal margins, and internal target volume (ITV) expansions [26, 27].

Next, we discussed the prediction accuracy of dose distributions using MAE, MSE, PSNR, and SSIM across irradiation techniques (IMPT and passive proton therapy) and imaging modalities (dMRI and dCT).

The MAE values ranged from 1.2% to 3.0% across all directions, with the smallest error observed in the sagittal direction for dCT_Passive (1.2%) and the largest in the coronal direction for dMRI_IMPT (3.0%). Considering that the acceptable range of dose measurement error in radiotherapy quality assurance is generally within ± 3%, these values suggest favorable prediction accuracy [28].

For MSE, values ranged from 0.002 ± 0.001 to 0.004 ± 0.002, with the best results observed for dCT_IMPT and dCT_Passive in the axial and sagittal directions. These ranges are considered highly favorable for similarity evaluations within the imaging field, indicating high prediction accuracy across all irradiation types. Huai-Wen Zhang et al. conducted dose distribution predictions for liver SBRT, reporting MSE values ranging from 0.0004 to 0.008 compared to the ground truth, which is nearly equivalent to the results obtained in this study [29].

PSNR is a quantitative metric used to evaluate image reproducibility, with a clinically acceptable accuracy generally considered to fall within the range of 25–30 dB [30]. The PSNR results in this study ranged from 24 to 28 dB, confirming that the predicted dose distributions achieved a clinically sufficient level of reproducibility. Passive proton therapy exhibited the highest PSNR across all directions, indicating the most accurate prediction performance. In contrast, IMPT showed a slight decrease in PSNR in the coronal direction, which may be attributed to the characteristics of the spot or line scanning technique. IMPT generates complex dose distributions through energy modulation, leading to steeper dose gradients and increased local variations. Consequently, minor reductions in reproducibility between the predicted and reference dose distributions may occur. Conversely, passive proton therapy employs fixed-port irradiation, resulting in fewer low-dose regions and a more uniform dose distribution. This characteristic likely contributes to consistently higher PSNR values.

SSIM values were also high, ranging from 0.898 to 0.959. Passive techniques achieved the highest SSIM scores (0.943–0.959), indicating excellent structural similarity to the reference dose distribution. IMPT followed with values ranging from 0.898 to 0.940, which also indicates a high degree of similarity. While SSIM values between 0.85 and 0.90 are considered to reflect good agreement, some localized visual deviations may still be observed [31, 32]. These localized deviations were primarily observed in regions with steep dose gradients or near the boundaries between high-dose and low-dose areas, particularly in IMPT plans. These findings aligns with the PSNR results and supports a similar interpretation.

In addition to the quantitative similarity metrics, the 3D gamma analysis provided further validation of the prediction accuracy from a clinically oriented perspective. The mean ± standard deviation of the gamma passing rates were 82.39 ± 5.63% for IMPT_dCT, 83.04 ± 5.92% for IMPT_dMRI, 92.96 ± 3.10% for Passive_dCT, and 92.02 ± 3.60% for Passive_dMRI. These results reinforce the trends observed in MAE, MSE, PSNR, and SSIM, where passive proton therapy consistently outperformed IMPT in terms of accuracy and reproducibility.

The lower gamma passing rates observed in IMPT predictions, particularly in the coronal direction, correspond to the increased MSE and reduced PSNR and SSIM values in the same planes. Although few studies have reported gamma analysis using the same line-scanning technique as ours, Chou et al. demonstrated very high gamma passing rates under the 3 mm/3% criterion, while under the more stringent 2 mm/2% condition, values ranged from 80 to 100%. This supports the notion that when OARs are included in the irradiated area, the inherent complexity of scanning techniques—characterized by sharp dose gradients and heterogeneous modulation—can lead to spatial discrepancies [33]. Similarly, in our IMPT prediction results, it is considered that accurate prediction around steep dose gradients near OARs was particularly challenging. In contrast, the dose distributions generated by passive scattering techniques, which use boluses and collimators, involve less spatial complexity than IMPT. As a result, they demonstrated higher gamma passing rates, reduced prediction errors, and superior values across all evaluation metrics.

Although the prediction performance for IMPT was lower than that for passive techniques, considering the accurate DVH prediction results, voxel-wise error metrics (MAE, MSE), perceptual similarity measures (PSNR, SSIM), and spatial agreement evaluations (gamma analysis), we conclude that both IMPT and passive techniques achieved sufficiently high prediction accuracy based on diagnostic imaging to support clinical decision-making regarding treatment feasibility.

Therefore, we consider that real-time dose distribution estimation can be performed at the time of a patient’s initial consultation by using existing dCT or dMRI, without the need for planning CT, and on commonly used PCs such as those for electronic medical records. Such early prediction can support the clinical decision-making in challenging cases where the feasibility of proton therapy is uncertain due to trade-offs with adjacent OARs. It also has the potential to reduce the burden on treatment planning staff. Additionally, since proton therapy is costly and often requires pre-authorization from insurance providers, providing early dosimetric evidence may help streamline approval processes and avoid delays in treatment initiation.

However, it should be noted that abdominal anatomy can vary due to factors such as respiratory motion and air pockets. Because our predictions are based on pre-treatment diagnostic images, discrepancies may arise between the predicted and actual dose distributions at the time of planning. Still, our system is intended as an early triage tool—not a replacement for planning CT. If predictions indicate clinical feasibility, proceeding with planning CT becomes reasonable. If not, alternative treatments may be considered without unnecessary imaging. Thus, despite some anatomical uncertainty, our approach offers practical value in guiding timely and informed treatment decisions.

Conclusions

This study proposed a method for predicting proton therapy dose distributions for HCC based on diagnostic imaging obtained prior to planning CT. By using a lightweight, CPU-based CNN, the model enables real-time predictions of both DVHs and 3D dose distributions during the initial consultation. The predicted results demonstrated high agreement with reference plans, with consistently favorable values across MAE, MSE, PSNR, and SSIM metrics. Furthermore, 3D gamma analysis confirmed the spatial and dosimetric validity of the predicted dose distributions.

Importantly, the model achieved comparable accuracy when using dMRI and dCT. This approach can help identify clinically feasible cases without requiring immediate planning CT acquisition, potentially reducing unnecessary radiation exposure and planning workload. Moreover, early dose prediction can support insurance pre-authorization by providing preliminary dosimetric evidence, thereby helping to avoid treatment delays.

Although the current model does not incorporate beam angles or irradiation geometry, future integration of these parameters—as well as patient-specific anatomical variations—may further enhance prediction accuracy, particularly for complex delivery techniques like IMPT.

In the future, expanding this approach to other cancer types, leveraging improvements in diagnostic imaging, and incorporating emerging machine learning techniques may further broaden its clinical utility. These findings underscore the potential for diagnostic image–based dose prediction models to support clinical decision-making and streamline the radiotherapy workflow.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgments.

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CNN

Convolutional neural networks

- CT

Computed tomography

- dMRI

Diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging

- VMAT

Volumetric modulated arc therapy

- IMPT

Intensity-modulated proton therapy

- DVH

Dose-volume histogram

- MAE

Mean absolute error

- MSE

Mean squared error

- PSNR

Peak signal-to-noise ratio

- SSIM

Structural similarity index

- DICOM

Digital imaging and communications in medicine

Author contributions

TR: Writing, Review and Editing, Software Development, Data curation Contouring, Formal analysis, and Visualization. TT: Review and Editing, Patient Selection, Contouring, and Dose Distribution Creation.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Proposal No. 21K07741).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study is a retrospective analysis of radiotherapy outcomes using existing patient data. Ethical approval for the use of these data was granted by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center Hospital, Japan (Approval No. 2020-272, dated 12 October 2020). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant institutional guidelines."

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for the use of personal data and images in this publication. The patient(s) were fully informed about the purpose of the study, the intended use of their data and images, and their rights to privacy. The consent form is retained by the corresponding author and is available upon request, should it be necessary for legal or ethical purposes. Additionally, this information can be referenced on the National Cancer Center Hospital East website: https://www.ncc.go.jp/jp/ncce/index.html.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Takeda A, Sanuki N, Tsurugi Y, Iwabuchi S, Matsunaga K, Ebinuma H, et al. Phase 2 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and optional transarterial chemoembolization for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to resection and radiofrequency ablation. Cancer. 2016;13:2041–9. 10.1002/cncr.30008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong TS, Wo JY, Yeap BY, Ben-Josef E, McDonnell EI, Blaszkowsky LS, et al. Multi-institutional phase II study of high-dose hypofractionated proton beam therapy in patients with localized, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:460–8. 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu-Lun T, Takei H, Lizumi T, Okumura T, Sekino Y, Numajiri H, et al. Capacity of proton beams in preserving normal liver tissue during proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Radiat Res. 2020;62:133–41. 10.1093/jrr/rraa098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korean Liver Cancer Study Group, National Cancer Center Korea. Practice guidelines for management of hepatocellular carcinoma 2009. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:391–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson AB III, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Abrams RP, Alberts MJ, Saenz AS, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: hepatobiliary cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:563–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalogeridi MA, Zygogianni A, Kyrgias G, Kouvaris J, Chatziioannou S, Kelekis N, et al. Role of radiotherapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:101–12. 10.4254/wjh.v7.i1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakayama H, Sugahara S, Tokita M, Fukuda K, Mizumoto M, Abei M, et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: the University of Tsukuba experience. Cancer. 2009;115:5499–506. 10.1002/cncr.24619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukumitsu N, Sugahara S, Nakayama H, Fukuda K, Mizumoto M, Abei M, et al. A prospective study of hypofractionated proton beam therapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:831–6. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer; 2015. p. 234–41. 10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

- 10.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016. p. 770–8. 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

- 11.Liu Y, Chen Z, Wang J, Wang X, Qu B, Ma L, et al. Dose prediction using a three-dimensional convolutional neural network for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with tomotherapy. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 752007. 10.3389/fonc.2021.752007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kearney V, Chan JW, Haaf S, Descovich M, Solberg TD. Dosenet: a volumetric dose prediction algorithm using 3d fully-convolutional neural networks. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63: 235022. 10.1088/1361-6560/aaef74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizumoto M, Okumura T, Hashimoto T, Fukuda K, Oshiro Y, Fukumitsu N, et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison of three treatment protocols. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:1039–45. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizumoto M, Tokuuye K, Sugahara S, Nakayama H, Fukumitsu N, Ohara K, et al. Proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma adjacent to the porta hepatis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:462–7. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawashima M, Furuse J, Nishio T, Konishi M, Ishii H, Kinoshita T, et al. Phase II study of radiotherapy employing proton beam for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1839–46. 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robeson SM, Willmott CJ. Decomposition of the mean absolute error (MAE) into systematic and unsystematic components. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0279774. 10.1371/journal.pone.02797746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanabe Y, Ishida T. Quantification of the accuracy limits of image registration using peak signal-to-noise ratio. Radiol Phys Technol. 2017;10:91–4. 10.1007/s12194-016-0372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma C, Wang R, Zhou S, Wang M, Yue H, Zhang Y, et al. The structural similarity index for IMRT quality assurance: radiomics-based error classification. Med Phys. 2021;48:80–93. 10.1002/mp.14559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen D, Long T, Jia X, Lu W, Gu X, Iqbal Z, et al. A feasibility study for predicting optimal radiation therapy dose distributions of prostate cancer patients from patient anatomy using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1076. 10.1038/s41598-018-37741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harms J, Lei Y, Wang T, McDonald M, Ghavidel B, Stokes W, et al. Cone-beam CT-derived relative stopping power map generation via deep learning for proton radiotherapy. Med Phys. 2020;47:4416–27. 10.1002/mp.14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Lei Y, Wang Y, Wang T, Ren L, Lin L, et al. MRI-based treatment planning for proton radiotherapy: dosimetric validation of a deep learning-based liver synthetic CT generation method. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64: 145015. 10.1088/1361-6560/ab25bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahiner B, Pezeshk A, Hadjiiski LM, Wang X, Drukker K, Cha KH, et al. Deep learning in medical imaging and radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2019;46:e1–36. 10.1002/mp.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y, Liu Y, Chen H, Yang X, Ma K, Zheng Y, et al. Lenas: learning-based neural architecture search and ensemble for 3-D radiotherapy dose prediction. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2024. 10.1109/TCYB.2024.3390769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn SH, Kim E, Kim C, Cheon W, Kim M, Lee SB, et al. Deep learning method for prediction of patient-specific dose distribution in breast cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2021;16: 154. 10.1186/s13014-021-01864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen D, Long T, Jia X, Lu W, Gu X, Iqbal Z, et al. A feasibility study for predicting optimal radiation therapy dose distributions of prostate cancer patients from patient anatomy using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–10. 10.1038/s41598-018-37741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai X, Zhang J, Wang B, Wang S, Xiang Y, Hou Q. Sharp loss: a new loss function for radiotherapy dose prediction based on fully convolutional networks. Biomed Eng Online. 2021;20: 101. 10.1186/s12938-021-00937-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamsi A, Asgharnezhad H, Mohammadi P, Soofi R. An uncertainty-aware loss function for training neural networks with calibrated predictions. Mach Learn Comput Vis Pattern Recognit. 2021. 10.48550/arXiv.2110.03260. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraass B, Doppke K, Hunt M, Kutcher G, Starkschall G, Stern R, et al. American association of physicists in medicine radiation therapy committee task group 53: quality assurance for clinical radiotherapy treatment planning. Med Phys. 1998;25:1773–829. 10.1118/1.598373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang HW, Wang YH, Hu B, Pang HW. Uninvolved liver dose prediction in stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver cancer based on the neural network method. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;16(10):4146–56. 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i10.4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobako M. Image compression guidelines for digital documents. JIIMA Standardization Committee, Vice Chair (JIS). Available from: https://www.jiima.or.jp/pdf/5_JIIMA_guideline.pdf.

- 31.Wang Z, Bovik AC, Sheikh HR, Simoncelli EP. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13:600–12. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1284395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Maruyama S. Properties of the SSIM metric in medical image assessment: correspondence between measurements and the spatial frequency spectrum. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2023;46:1131–41. 10.1007/s13246-023-01280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou CY, Huang HC, Lee SH, Hsu SM. Dosimetric evaluation and clinical application of collimated apertures with proton beam line scanning in stereotactic radiotherapy. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2025. 10.1002/acm2.70128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.