Abstract

Background

The global nursing shortage has intensified the need for effective leadership strategies to enhance nurse performance and retain skilled staff, particularly in high-stress environments like intensive care units Transformational leadership has been recognized as a critical factor in improving nurses’job performance. However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain underexplored. This study investigates the direct impact of transformational leadership on ICU nurses’job performance and examines the mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted. Between October to November 2024, a total of 584 intensive care nurses from China completed the survey, which included standard assessments on transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement, and job performance. Structural equation modeling was employed to analyze the direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on job performance, with psychological empowerment and work engagement as mediators.

Results

The results indicated significant positive correlations among transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement, and job performance (all P < 0.01). Transformational leadership not only directly affected the job performance of intensive care nurses but also influenced it through the partial mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement, with the mediating effects accounting for 24.64% and 21.74% of the total effect, respectively. Additionally, the analysis found that psychological empowerment and work engagement, played a chain mediating role in the relationship between transformational leadership and the job performance, with the mediating effect accounting for 15.94% of the total effect.

Conclusions

This study highlights the association between transformational leadership and ICU nurses’ job performance, both directly and indirectly through psychological empowerment and work engagement. The findings suggest that transformational leadership is related to key psychological and behavioral factors that may support better job performance. Fostering transformational leadership behaviors may serve as a valuable approach for nursing managers to enhance psychological empowerment and engagement among ICU nurses, with potential benefits for patient care outcomes.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03685-7.

Keywords: Transformational leadership, Psychological empowerment, Work engagement, Job performance, Nurses

Introduction

Nurse job performance, a key determinant of healthcare quality, encompasses the efficiency, effectiveness, and outcomes of nurses’ tasks and responsibilities within clinical settings [1]. High job performance in nursing is crucial for ensuring optimal patient care, improving clinical outcomes, and maintaining a supportive work environment [2]. In particular, the job performance of intensive care unit (ICU) nurses is paramount, given the complexity of care and the critical nature of their patients [3]. The demanding environment of ICU requires nurses to demonstrate high levels of clinical expertise, decision-making, and emotional resilience, all of which are essential for delivering high-quality, patient-centered care [3].

Intensive Care Units (ICUs) are specialized hospital departments that provide continuous, intensive treatment for critically ill patients. These units operate through interdisciplinary teamwork among physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and other professionals [4]. While physicians primarily lead medical decision-making, ICU nurses—especially nurse managers—serve as key leaders responsible for coordinating care delivery, managing nursing staff, maintaining workflow efficiency, and providing emotional and professional support [5]. Compared to general ward nurses, ICU nurses receive more advanced clinical training and are expected to uphold a higher level of vigilance and autonomy [5]. In this context, nurse managers are not only operational supervisors but also critical drivers of performance and morale [6]. Their leadership plays a central role in shaping nurses’ perceptions of support, psychological empowerment, and work motivation [6]. Although physicians also hold formal authority, it is typically the nurse manager who acts as the immediate and most influential leader in the daily professional lives of ICU nurses.

However, the global nursing workforce faces significant challenges, most notably the persistent shortage of nurses. The World Health Organization predicts a global nursing shortage of 4.6 million by 2030 without immediate action [7]. In the U.S., an annual addition of 190,000 registered nurses is required from 2022 to 2033 to address the gap [8]. By the end of 2020, China had 4.7 million registered nurses, with a doctor-to-nurse ratio of 1:1.15, well below the international standard of 1:3 [9]. This shortage is particularly pronounced in ICU departments, where the intensity of care and specialized skills required to manage critically ill patients often exceed the availability of qualified nursing staff [10]. The resulting strain on ICU nurses not only increases workload and psychological demands but also challenges their ability to maintain high levels of job performance [3]. Therefore, identifying and strengthening the factors that enhance ICU nurses’ job performance is critical to sustaining care quality and ensuring the operational efficiency of critical care units. Leadership style is a key factor influencing job performance, with transformative leadership emerging as a critical determinant in fostering positive outcomes [11]. According to Yukl et al. [12], leadership styles can be classified into task-oriented, relations-oriented, and change-oriented categories. As Bormann and Rowold emphasized, transformational leadership predominantly aligns with the change-oriented category, as it focuses on articulating a compelling vision, promoting innovation, and driving organizational transformation [13]. However, transformational leadership also contains important relational elements, such as individualized consideration, charisma, and emotional support, which foster trust and strengthen leader–follower bonds [14]. In high-stress environments such as intensive care units (ICUs), these relational dimensions are not merely supplementary but fundamentally essential. Previous studies have shown that transformational leadership positively impacts various outcomes, including job satisfaction [14], quality of patient care [15], and innovative work behavior [16]. However, the specific effects of transformational leadership on ICU nurses’ job performance and its underlying mechanisms remain underexplored. Moreover, psychological empowerment and work engagement are two key psychological resources that significantly impact job performance and engagement [17, 18]. Both constructs have been linked to enhanced motivation and performance at work, yet little research has examined how these variables mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and ICU nurses’ job performance. Therefore, this study aims to explore the intricate relationships and interactive mechanisms among transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement, and ICU nurses’ job performance. By investigating these dynamics, this research seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how effective leadership can enhance nurse performance in high-pressure ICU environments.

Background

Transformational leadership and job performance

Leadership is widely acknowledged as a critical determinant of organizational outcomes, especially in healthcare, where its impact extends to both employee performance and patient care [19]. The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory emphasizes the importance of high-quality leader-member relationships in enhancing job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and overall performance [20]. Various positive leadership styles—such as inclusive leadership, servant leadership, humble leadership, and more recently, engaging leadership—have been shown to positively influence employees’ work engagement and job performance. These styles generally emphasize trust, support, collaboration, and empowerment in the leader–follower relationship [21–24]. Among them, transformational leadership is particularly distinguished by its capacity to inspire, intellectually stimulate, and individually consider followers, thereby motivating them to exceed expectations and realize their full potential [25]. Compared to other leadership styles that often focus on mutual exchange, service to others (e.g., servant leadership), or shared decision-making (e.g., inclusive leadership), transformational leadership offers a more proactive and visionary approach, aligning followers’ goals with organizational vision and fostering deep psychological empowerment [25]. Transformational leaders cultivate strong individualized relationships, reduce hierarchical distance, and place a strong emphasis on both emotional and professional development of staff [26]. Previous studies have demonstrated that transformational leadership enhances various employee behaviors, including voice behavior [27], innovation [16], and organizational commitment [28]. When employees feel valued, empowered, and supported by their leaders, they are more likely to exert greater effort toward achieving organizational goals, which, in turn, improves overall job performance [28]. While much of the existing literature has explored the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance in commercial environments, less attention has been paid to its application in healthcare, particularly among ICU nurses [29, 30]. Establishing a strong leader-follower relationship through reciprocal interactions between nursing leaders and ICU nurses is vital for fostering engagement and improving job performance in this high-stress, high-stakes context. Based on these considerations, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Transformational leadership positively predicts intensive care nurses’ job performance.

The potential mediating role of psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment refers to individuals’ perception of their work as meaningful, their belief in their competence, and their sense of control over work-related outcomes [31]. According to self-determination theory, fostering a positive organizational environment can significantly enhance employees’ psychological empowerment [32]. When leaders exhibit supportive behaviors and foster respect and equity, they strengthen leader-subordinate interactions, boosting employees’ sense of belonging and empowerment [32]. Studies indicate that leadership styles like inclusive and servant leadership positively correlate with psychological empowerment [22, 23]. Additionally, Psychological empowerment has also been linked to job performance through the lens of intrinsic motivation theory, which posits that individuals’ proactive behaviors are primarily driven by internal motivations [33]. Amabile and colleagues highlighted that higher autonomy and control in one’s work increase the likelihood of innovative and proactive behaviors, leading to improved performance outcomes [34]. Arshadi’s research also emphasizes the role of psychological empowerment in enhancing ICU nurses’ clinical competency, further demonstrating its importance in high-stress healthcare settings [35].

Building on these insights, this study hypothesizes that transformational leadership styles adopted by nursing managers can enhance ICU nurses’ psychological empowerment. This, in turn, enables nurses to confidently manage the complexities of critical care environments, ultimately improving job performance. Based on this discussion, Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

Psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and intensive care nurses’ job performance.

The potential mediating role of work engagement

Work engagement refers to a positive, work-related psychological state characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [17]. As leaders occupy pivotal roles within organizations, their actions in task delegation, performance evaluation, and feedback provision significantly influence employees’ work engagement [36]. Research has shown that humble leadership fosters a sense of personal growth and purpose in employees by inspiring intrinsic motivation through sincere learning attitudes and tailored work arrangements [37]. Similarly, authentic leadership creates a high-trust environment, enabling employees to leverage their strengths, adopt a more positive mindset, and enhance their engagement [38].

Additionally, studies have shown that employees’work engagement is positively correlated with organizational expected behaviors [39]. This connection arises because engaged employees are more committed to their roles, aligning their efforts with organizational goals [40]. In the context of ICU nurses, who face high-stakes, complex environments, this study hypothesizes that transformational leadership by nursing managers can cultivate a positive, inclusive, and empowering atmosphere. This, in turn, is likely to boost their work engagement, motivating them to fulfill their duties proactively and enhance their job performance. Based on the above discussion, this study proposes Hypothesis 3:

Work engagement mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and intensive care nurses’ job performance.

The relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement

Psychological empowerment and work engagement share a focus on enhancing employees’ intrinsic motivation and active involvement in their roles. However, psychological empowerment emphasizes the perception of control, meaning, and competence at work, while work engagement highlights the emotional and motivational activation through vigor, dedication, and absorption [17, 18]. Juyumay’s research revealed a significant positive correlation between psychological empowerment and work engagement, indicating that higher levels of empowerment enhance engagement [41]. Meng’s empirical findings further support the predictive role of psychological empowerment in promoting work engagement [42]. Through the above literature review, we found that transformational leadership has a close relationship with psychological empowerment. Psychological empowerment influences work engagement, and work engagement, in turn, predicts job performance. Based on this, we propose Hypothesis 4:

Psychological empowerment and work engagement play a serial mediating role in the relationship between transformational leadership of nursing managers and the job performance of ICU nurses.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a cross-sectional design and was conducted in adherence to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (see Supplementary File 1).

Participants and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted among intensive care unit (ICU) nurses recruited from four comprehensive hospitals located in northern China, using convenience sampling. Eligible participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) possession of a valid nurse certification and registration; (2) a minimum of one year of independent clinical experience in the ICU; and (3) willingness to provide informed consent and participate voluntarily in the survey. Nurses who were on leave or engaged in external studies were excluded. The sample size was calculated using the formula N = 4Uα2S2/δ2 [43], where S = 0.53 was derived from the pre-survey, the allowable error δ was set to 0.1, and α was set to 0.05. Substituting these values, N = 4 × 1.962 × 0.512/0.12 ≈432. To account for sampling errors and potential invalid responses, a total of 600 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding 16 unqualified responses, 584 valid results were included in the final analysis. Furthermore, previous research indicates that a sample size of ≥ 200 is generally deemed sufficient for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis [44, 45]. Accordingly, the sample size in this study satisfies the fundamental requirements for model validation.

Data collection

Under the supervision of well-trained research assistants, participants provided data on socio-demographics, transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement, and job performance. Before the survey, researchers coordinated with the nursing management departments of each hospital to obtain consent and finalize details regarding the survey’s timing, location, and participant numbers. During the investigation, the researchers explained the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study to the participants, ensuring their privacy. After obtaining the signed informed consent forms from the participants, the researchers proceeded to distribute and collect the questionnaires. The data collection period was from October to November 2024.

Measurements

Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership was measured using the Transformational Leadership Questionnaire (TLQ) developed by Li, which was adapted from Bass and Avolio’s original transformational leadership framework to better suit the Chinese cultural and organizational context [46]. The scale comprises four dimensions: Morale Modeling (demonstrating ethical behavior and acting as a role model), Charisma (building trust and respect through interpersonal influence), Visionary (articulating a compelling vision and motivating followers), and Individualized Consideration (attending to individual needs and supporting staff development). The TLQ uses a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 to 5 represent “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” respectively, with total scores ranging from 26 to 130. Higher scores indicate a higher level of transformational leadership as perceived by nurses. This scale demonstrates high reliability and validity within the context of Chinese culture. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.981.

Psychological empowerment

The Psychological Empowerment Questionnaire (PEQ) was developed by Spreitzer and translated and revised by Li to align with the Chinese cultural context [47]. It is divided into four dimensions: Self-efficacy, Meaning of Work, Autonomy, and Work Impact. The questionnaire includes 12 items, such as “The work I do is very meaningful to me,” “My work is very important to me,” and “I am very confident in my ability to do my job well.” The PEQ uses a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 to 5 represent “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” respectively. The total score ranges from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher level of psychological empowerment. This scale demonstrates high reliability and validity within the Chinese cultural context. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.976.

Work engagement

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) was developed by Schaufeli and translated and revised by Zhang to fit the Chinese cultural context [48]. It comprises three dimensions: Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption. The scale includes 16 items, such as “I feel full of energy when working,” “I am in a very cheerful mood while working,” and “I find the work I do to be very meaningful.” The UWES uses a 7-point Likert scale, where 0 to 6 represent “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” respectively. The total score ranges from 0 to 96, with higher scores indicating higher levels of work engagement among nurses. This scale demonstrates high reliability and validity within the Chinese cultural context. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.944.

Job performance

The Nurse Job Performance Scale, developed by Wang, comprises 14 items across three dimensions: work coordination, work enthusiasm, and work involvement [49]. Examples of items include, “I work collaboratively with colleagues (doctors, nurses, and support staff),” “I actively request to participate in the rescue of critically ill patients,” and “I am willing to take on tasks outside of work and devote extra time and effort to work.” Responses are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). Higher scores reflect greater levels of job performance. In this study, the scale demonstrated excellent reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.952.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior (Approval No. HUSOM2023-478).This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, informed consent was obtained from the nursing management departments of the participating hospitals. The purpose and significance of the study were thoroughly explained to all participants to ensure their understanding of the research. On this basis, informed consent was obtained from all participants, who voluntarily signed the consent form.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis of the collected data was conducted using SPSS version 27.0 and AMOS version 25.0. First, descriptive statistical methods were applied to analyze the general characteristics of the participants. Second, normality tests were performed on continuous variables. If the continuous variables followed a normal distribution, Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among them; otherwise, Spearman correlation analysis was applied. Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement in the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance.

To assess the goodness-of-fit of the hypothesized model, the following criteria were used: Chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). A model fit was considered acceptable if χ2/df < 5, GFI > 0.90, AGFI > 0.90, CFI > 0.90, IFI > 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and SRMR < 0.05 [45, 50].

Results

Participant characteristics

Among the 600 participants surveyed, 584 completed the questionnaire effectively, resulting in a valid response rate of 97.33%. The participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 52 years (31.09 ± 6.54 years). 86.5% were female (n = 505), and 13.5% were male (n = 79). Over 60% of the nurses were married (n = 357), and 78.9% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (n = 461). Detailed demographic data of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of ICU nurses (N = 584)

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 79 | 13.5 |

| Female | 505 | 86.5 | |

| Age(years) | <30 | 278 | 47.6 |

| 30 ~ 40 | 235 | 40.2 | |

| >40 | 71 | 12.2 | |

| Work experience (years) | 1–5 | 280 | 47.9 |

| 6–10 | 176 | 30.1 | |

| >10 | 128 | 21.9 | |

| Marital status | Single | 227 | 38.9 |

| Married | 357 | 61.1 | |

| Education level | Junior college or below | 60 | 10.3 |

| Bachelor’s | 461 | 78.9 | |

| Master’s or above | 63 | 10.8 | |

| Professional title | Nurse | 153 | 26.2 |

| Nurse practitioner | 197 | 33.7 | |

| Nurse-in-charge | 209 | 35.8 | |

| Associate professor of nursing or above | 25 | 4.3 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | <5000 | 110 | 18.8 |

| 5000 ~ 8000 | 244 | 41.8 | |

| >8000 | 230 | 39.4 | |

Descriptive statistics and correlations of transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement and job performance

The range, mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients of each variable are presented in Table 2. The average score for transformational leadership was (3.22 ± 0.64), while the average score for psychological empowerment was (3.47 ± 0.53). The mean score for work engagement was (3.79 ± 0.48), and the mean score for job performance was (3.92 ± 0.47). Normality tests indicated that all data followed a normal distribution.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis (r)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Range | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.22 ± 0.64 | |||||||||||||||||

| Morale Modeling | 0.372** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.34 ± 0.56 | ||||||||||||||||

| Charisma | 0.253** | 0.706** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.17 ± 0.71 | |||||||||||||||

| Visionary | 0.654** | 0.654** | 0.754** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 2.85 ± 0.63 | ||||||||||||||

| IC | 0.598** | 0.630** | 0.748** | 0.749** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.52 ± 0.66 | |||||||||||||

| PE | 0.792** | 0.684** | 0.674** | 0.689** | 0.652** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.47 ± 0.53 | ||||||||||||

| SE | 0.405** | 0.381** | 0.361** | 0.361** | 0.346** | 0.518** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.51 ± 0.46 | |||||||||||

| MW | 0.712** | 0.696** | 0.676** | 0.690** | 0.651** | 0.465** | 0.493** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.43 ± 0.49 | ||||||||||

| Autonomy | 0.643** | 0.631** | 0.627** | 0.635** | 0.606** | 0.326** | 0.544** | 0.895** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.46 ± 0.52 | |||||||||

| WIT | 0.565** | 0.567** | 0.590** | 0.624** | 0.591** | 0.387** | 0.415** | 0.852** | 0.846** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.48 ± 0.65 | ||||||||

| WE | 0.332** | 0.335** | 0.224** | 0.327** | 0.258** | 0.314** | 0.369** | 0.726** | 0.667** | 0.654** | 1 | 0 ~ 6 | 3.79 ± 0.48 | |||||||

| Vigor | 0.427** | 0.405** | 0.457** | 0.478** | 0.446** | 0.558** | 0.313** | 0.562** | 0.500** | 0.522** | 0.502** | 1 | 0 ~ 6 | 4.24 ± 0.56 | ||||||

| Dedication | 0.442** | 0.424** | 0.493** | 0.527** | 0.481** | 0.551** | 0.291** | 0.557** | 0.499** | 0.501** | 0.540** | 0.876** | 1 | 0 ~ 6 | 3.57 ± 0.43 | |||||

| Absorption | 0.447** | 0.450** | 0.491** | 0.527** | 0.472** | 0.544** | 0.268** | 0.546** | 0.498** | 0.498** | 0.538** | 0.808** | 0.905** | 1 | 0 ~ 6 | 3.56 ± 0.45 | ||||

| JP | 0.254** | 0.890** | 0.865** | 0.833** | 0.823** | 0.212** | 0.426** | 0.780** | 0.713** | 0.662** | 0.452** | 0.494** | 0.527** | 0.534** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.92 ± 0.47 | |||

| WC | 0.524** | 0.488** | 0.537** | 0.548** | 0.553** | 0.638** | 0.452** | 0.623** | 0.610** | 0.591** | 0.591** | 0.641** | 0.627** | 0.625** | 0.595** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 4.43 ± 0.36 | ||

| Work enthusiasm | 0.522** | 0.518** | 0.578** | 0.582** | 0.548** | 0.622** | 0.435** | 0.620** | 0.580** | 0.562** | 0.615** | 0.665** | 0.664** | 0.661** | 0.619** | 0.878** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.80 ± 0.54 | |

| WI | 0.541** | 0.538** | 0.568** | 0.569** | 0.541** | 0.625** | 0.480** | 0.620** | 0.589** | 0.560** | 0.618** | 0.637** | 0.633** | 0.636** | 0.626** | 0.820** | 0.887** | 1 | 1 ~ 5 | 3.53 ± 0.51 |

Abbreviations: TL transformational leadership; IC, Individualized Consideration; PE, Psychological empowerment; SE, Self-efficacy; MW, Meaning of Work; WIT, Work Impact; WE, Work engagement; JP, Job performance; WC, Work coordination; WI, Work involvement;

**P < 0.01

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations among the variables. Transformational leadership was positively associated with psychological empowerment, work engagement and job performance (r = 0.792, 0.332, 0.254; all P < 0.01). Psychological empowerment showed significant positive correlations with work engagement and job performance (r = 0.314, 0.212; both P < 0.01). Additionally, work engagement was significantly positively correlated with job performance (r = 0.452, P < 0.01). Detailed correlation coefficients for the selected variables are presented in Table 2.

Mediating effect analysis

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to examine the mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement in the relationship between Transformational leadership and job performance. Model fit indices were evaluated to assess the adequacy of the model’s alignment with the data. The results indicated that the model fit was acceptable (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Model-fitting standards and fit indices of the final model

| χ 2 /df | GFI | AGFI | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-fitting standard | < 5 | > 0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | ≤ 0.08 | < 0.05 |

| Model-fitting index | 3.96 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

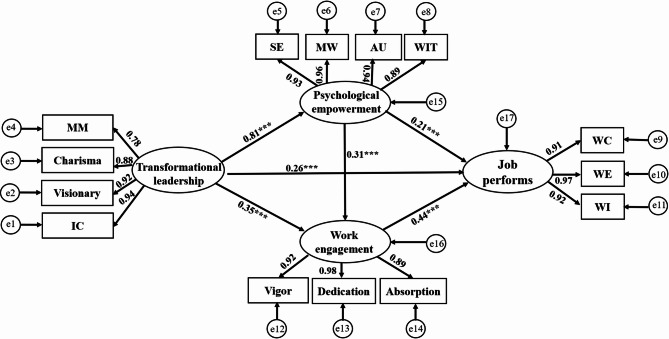

The mediation analysis demonstrated that transformational leadership significantly and positively predict ICU nurses’ psychological empowerment (β = 0.81, t = 12.44, P < 0.001), work engagement (β = 0.35, t = 5.12, P < 0.001), and job performance (β = 0.26, t = 4.63, P < 0.001). Psychological empowerment exerted a significant positive direct effect on work engagement (β = 0.31, t = 4.42, P < 0.001) and job performance (β = 0.21, t = 3.89, P < 0.001). Moreover, work engagement was a significant predictor of job performance (β = 0.44, t = 11.81, P < 0.001; see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement in the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance. Abbreviations: MM, Morale Modeling; IC, Individualized Consideration; SE, Self-efficacy; MW, Meaning of Work; AU, Autonomy; WIT, Work Impact; WC, Work coordination; WE, Working enthusiasm; WI, Work involvement; ***P < 0.001

To investigate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through mediators, a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using percentile bootstrapping and bias-corrected percentile bootstrapping with 5000 bootstrap samples. Following the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes [51], the significance of the indirect effect was determined based on the upper and lower bounds of the CI. The analysis revealed that psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance. Similarly, work engagement also mediates this relationship. Furthermore, psychological empowerment and work engagement together form a chain mediation effect linking transformational leadership to job performance (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Bootstrap analysis of the mediating model

| Effect | Path | Standardized β | SE | The size of effect | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| IndA1 | TL→PE→JP | 0.17 | 0.05 | 24.64% | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| IndA2 | TL→WE→JP | 0.15 | 0.03 | 21.74% | 0.09 | 0.23 |

| IndA3 | TL→PE→WE→JP | 0.11 | 0.03 | 15.94% | 0.06 | 0.17 |

| Direct | TL→JP | 0.26 | ||||

| Total | TL→JP | 0.69 | ||||

Abbreviations: TL, Transformational leadership; PE, Psychological empowerment; JP, Job performs; WE, Work engagement

Discussion

This study investigated the influence of transformational leadership on the job performance of intensive care nurses, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement. The findings provide valuable insights into factors affecting the job performance of intensive care nurses. First, transformational leadership exhibited by nursing managers significantly enhances nurses’ job performance. Second, mediation analysis revealed that psychological empowerment and work engagement independently mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and job performance. Finally, psychological empowerment and work engagement together form a chain mediation mechanism linking transformational leadership to the job performance of ICU nurses.

Effect of transformational leadership on job performance

In this research, the job performance score was marginally higher compared to the findings reported by Yu et al. [1]. This discrepancy could be explained by differences in the characteristics of the study populations. Specifically, our study concentrated exclusively on ICU nurses, while Yu et al.‘s research included clinical nurses working in general wards. Since the ICU serves as the hospital’s primary unit for managing critically ill patients, nurses in this setting frequently encounter patients with more severe conditions. This demands the execution of highly complex and intensive nursing tasks, as well as the ability to remain vigilant and adapt to rapidly changing circumstances [52]. Such a demanding and intricate work environment may contribute to the elevated job performance observed among ICU nurses.

Consistent with the findings of Davis et al. [53], our study confirmed that transformational leadership significantly predicts ICU nurses’ job performance, supporting Hypothesis 1. Effective leadership is essential in the high-stakes ICU environment, where nurses face intense stress and complex patient needs [54]. In this study, transformational leadership—conceptualized through four key dimensions: morale modeling, charisma, visionary leadership, and individualized consideration—played a crucial role in enhancing nurses’ motivation and performance [26]. Specifically, morale modeling promotes ethical standards and sets behavioral expectations, reinforcing nurses’ professional identity and sense of responsibility [21]. Charisma strengthens interpersonal trust and respect, encouraging team cohesion and mutual support. Visionary leadership inspires nurses with a clear direction and shared goals, which increases their psychological empowerment and belief in their value to the organization [21]. Individualized consideration fosters a supportive environment by recognizing nurses’ unique needs, enhancing their engagement and commitment [55]. These dimensions create the psychosocial conditions necessary for ICU nurses to feel empowered and engaged in their work, which ultimately improves their job performance.

Mediation through psychological empowerment

The results revealed that participants’ levels of psychological empowerment were consistent with those reported in previous studies [56, 57], indicating that ICU nurses generally exhibit stronger autonomy, sense of meaning, self-efficacy, and engagement in their nursing duties. Additionally, the current analysis demonstrated that transformational leadership by nursing managers not only directly enhances nurses’ job performance but also indirectly exerts its effects by strengthening nurses’ psychological empowerment, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2.

In prior research, psychological empowerment has often been identified as a protective factor for job performance [17]. When nurses experience psychological empowerment, they are more likely to perceive their work as meaningful and believe in their ability to complete tasks effectively [56]. This intrinsic motivation and improved self-efficacy ignite nurses’ enthusiasm and engagement, ultimately boosting their job performance [56]. When nursing managers adopt transformational leadership behaviors—actively listening to nurses’ opinions and suggestions, respecting and trusting their abilities and potential—nurses feel valued and recognized [25].

This sense of appreciation enhances their confidence in their own abilities, making them more autonomous and decisive in executing nursing tasks. Empowered by such confidence, nurses can fully leverage their professional knowledge and skills to deliver high-quality care, thereby further improving job performance.

Mediation through work engagement

The results indicated that participants’ work engagement levels were moderate, consistent with the findings of Kato et al. [58]., suggesting that ICU nurses demonstrate a certain degree of enthusiasm and involvement in their nursing duties, though there is room for further improvement. Additionally, the analysis confirmed that transformational leadership by nursing managers not only directly enhances nurses’ job performance but also indirectly influences it through the partial mediating role of work engagement, supporting Hypothesis 3.

Work engagement, as a psychological state, serves as a crucial link in translating transformational leadership behaviors into improved performance [18]. The nature of ICU nursing demands sustained psychological investment and high focus on complex tasks [35]. Transformational leadership, through supportive behaviors and intellectual stimulation, enhances nurses’ sense of meaning and responsibility, enabling them to tackle challenges with greater energy [25]. In this context, work engagement reflects nurses’ psychological energy and acts as an intermediary mechanism connecting leadership to performance. Transformational leaders’ motivational and individualized care fosters a sense of support and recognition, increasing nurses’ focus and enthusiasm for their work [59]. This psychological boost drives nurses to fully commit to their tasks, exhibiting high levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption, which significantly enhances job performance.

Serial mediation of psychological empowerment and work engagement

This study also revealed that psychological empowerment influences ICU nurses’ work engagement, consistent with findings from other cross-cultural studies [60]. Furthermore, we identified a sequential mediating role of psychological empowerment and work engagement in the relationship between transformational leadership and ICU nurses’ job performance, supporting Hypothesis 4.

Transformational leadership, through behaviors such as inspiring vision and individualized care, fulfills nurses’ psychological needs for meaning, competence, autonomy, and impact, significantly enhancing their sense of psychological empowerment [28]. In the ICU, a complex work environment centered on patient safety, nurses face high-intensity tasks and decision-making pressures [61]. Psychological empowerment strengthens their recognition of their abilities and professional value, fostering confidence and proactivity when addressing complex challenges [41]. This intrinsic psychological motivation is particularly critical in the ICU, where it directly affects nurses’ capacity to handle high-risk tasks and manage stress. Empowered nurses are more likely to perceive their work as meaningful and important, which drives higher levels of vigor, focus, and dedication [62]. This engagement not only improves the quality of care but also enhances team collaboration, enabling more effective.

Limitations and future research

This study provides meaningful insights for designing interventions aimed at improving ICU nurses’ job performance. However, several limitations should be acknowledged to guide the interpretation and future research.

First, all data were collected at a single point in time, which limits the ability to infer temporal or causal relationships among the variables. While the mediation model proposes a directional pathway from transformational leadership to job performance via psychological empowerment and work engagement, the cross-sectional design precludes any definitive conclusions about process or causality. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs is needed to validate the temporal sequence and underlying mechanisms. Second, all variables were measured through self-reported questionnaires, which may introduce common method bias. Although we conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) to mitigate such bias to some extent, more robust procedures such as Harman’s single-factor test or the use of marker variables could be applied in future studies. Additionally, the possibility of social desirability bias cannot be excluded, particularly in hierarchical healthcare settings where nurses may feel compelled to respond in socially acceptable ways. Third, the study did not include or control for several potentially important confounding variables, such as shift type, length of ICU service, nurse-to-patient ratio, or departmental workload. These factors could influence both job performance and psychological constructs. We acknowledge this limitation and recommend future studies to collect and adjust for such contextual and demographic variables.

Lastly, Lastly, the sample was drawn from a limited number of comprehensive hospitals in northern China using convenience sampling, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, although the measurement tools (e.g., TLQ, PEQ, UWES) used in this study have been translated and validated in the Chinese context, their cultural specificity may limit the applicability of the results to other cultural or linguistic settings. Future research should further assess the cross-cultural equivalence of these instruments to support broader international generalization.

Conclusion

Amidst a global nursing shortage and increasing healthcare demands, improving nurses’ job performance remains essential. This study found that transformational leadership by nursing managers is associated with intensive care nurses’ job performance, both directly and indirectly through psychological empowerment and work engagement. These findings provide valuable insights for developing targeted strategies and may inform nursing management practices aimed at supporting team performance and potentially enhancing patient care outcomes in intensive care settings. However, future research should test these associations using longitudinal or intervention designs to establish temporal relationships and evaluate the effectiveness of such strategies.

Implications for nursing management

This study offers several practical implications for nursing management. First, the findings underscore the importance of fostering transformational leadership behaviors among nurse managers, as such leadership styles are positively associated with ICU nurses’ job performance. Second, given the partial mediating roles of psychological empowerment and work engagement, nursing administrators should prioritize strategies that enhance nurses’ sense of autonomy, competence, and meaningfulness at work. Third, interventions such as leadership training programs, empowerment workshops, and engagement-promoting initiatives could be integrated into organizational development plans to strengthen these mediators. Fourth, by cultivating a supportive leadership climate, nurse leaders can indirectly boost job performance through improved psychological states and motivational engagement. Lastly, these insights are particularly valuable in high-stress environments like intensive care units, where performance is critical to patient outcomes. Therefore, nursing management should consider transformational leadership as a strategic tool to improve staff performance, satisfaction, and retention, ultimately contributing to higher quality of care.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors particularly acknowledge the staff who helped collect dates and coordinate this survey and all participants who took part in this survey.

Author contributions

Qian Huang, Lina Wang, Jie Liu and Chaoran Chen, designed the content of this study, Haitao Huang and Qian Huang wrote the main manuscript text. Qian Huang and Haishan Tang participated in data analysis and made adjustments to the format of the manuscript. The manuscript was examined by all the authors, and all authors are responsible for the content and have approved this final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Tackling Project (RKX202402028); (2) Soft Science Project of the Henan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (242400410523).

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior (Approval No. HUSOM2023-478). This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, informed consent was obtained from the nursing management departments of the participating hospitals. The purpose and significance of the study were thoroughly explained to all participants to ensure their understanding of the research. On this basis, informed consent was obtained from all participants, who voluntarily signed the consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jie Liu, Email: 603838964@qq.com.

Chaoran Chen, Email: kfccr@126.com.

References

- 1.Yu JF, et al. Professional identity and emotional labour affect the relationship between perceived organisational justice and job performance among Chinese hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(5):1252–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, et al. Nurses’ colleague solidarity and job performance: mediating effect of positive emotion and turnover intention. Saf Health Work. 2023;14(3):309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Ajarmeh DO, et al. Nurse-nurse collaboration and performance among nurses in intensive care units. Nurs Crit Care. 2022;27(6):747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusaro MV, Becker C, Scurlock C. Evaluating Tele-ICU implementation based on observed and predicted ICU mortality: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(4):501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabbard ER, et al. Clinical nurse specialist: A critical member of the ICU team. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(6):e634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams AMN, Chamberlain D, Giles TM. Understanding how nurse managers see their role in supporting ICU nurse well-being-A case study. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(7):1512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(WHO), W.H.O. State of the world’s nursing 2020: investing in education, jobs and leadership. 2020; Available from: https://www.who.int/china/publications-detail/9789240003279

- 8.STATISTICS USBOL. Occupational Outlook Handbook, Registered Nurses. 2023 [cited 2024; Available from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm

- 9.PRC. N.H.C.o.t. National Nursing Development Plan (2021–2025). 2022; Available from: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-05/09/content_5689354.htm

- 10.Xu G, Zeng X, Wu X. Global prevalence of turnover intention among intensive care nurses: A meta-analysis. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(2):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scully NJ. Leadership in nursing: the importance of recognising inherent values and attributes to secure a positive future for the profession. Collegian. 2015;22(4):439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yukl G, Gordon A, Taber T. A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: integrating a half century of behavior research. J Leadersh Organizational Stud. 2002;9(1):15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bormann K, Rowold J. Construct proliferation in leadership style research: Reviewing pro and contra arguments. Organizational Psychology Review, 8 (2–3), 149–173. 2018.

- 14.Boamah SA, et al. Effect of transformational leadership on job satisfaction and patient safety outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(2):180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alanazi NH, Alshamlani Y, Baker OG. The association between nurse managers’ transformational leadership and quality of patient care: A systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2023;70(2):175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korku C, Kaya S. Relationship between authentic leadership, transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: mediating role of innovation climate. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2023;29(3):1128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asfour BY, et al. A relationship between management commitment, psychological empowerment, and job performance among employees in higher educational institutions in palestine: multi-Wave survey. J Psychol. 2024;159(2):132–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhang N, et al. Effects of role overload, work engagement and perceived organisational support on nurses’ job performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(4):901–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady Germain P, Cummings GG. The influence of nursing leadership on nurse performance: a systematic literature review. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(4):425–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karacay G, Rofcanin Y, Kabasakal H. Relative leader–member exchange perceptions and employee outcomes in service sector: the role of self-construal in feeling relative deprivation. Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2023;34(9):1808–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakker AB, et al. Daily transformational leadership: A source of inspiration for follower performance? Eur Manag J. 2023;41(5):700–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younas A, et al. Inclusive leadership and voice behavior: the role of psychological empowerment. J Soc Psychol. 2023;163(2):174–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saleem S, et al. Servant leadership and performance of public hospitals: trust in the leader and psychological empowerment of nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(5):1206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahmadani VG et al. Engaging leadership and its implication for work engagement and job outcomes at the individual and team level: A Multi-Level longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Abdul Salam H, et al. Transformational leadership and predictors of resilience among registered nurses: a cross-sectional survey in an underserved area. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Thawabiya A, et al. Leadership styles and transformational leadership skills among nurse leaders in qatar, a cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2023;10(6):3440–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G, et al. Transformational leadership and teachers’ voice behaviour: A moderated mediation model of group voice climate and team psychological safety. Educational Management Administration & Leadership; 2023. p. 17411432221143452.

- 28.Uslu Sahan F, Terzioglu F. Transformational leadership practices of nurse managers: the effects on the organizational commitment and job satisfaction of staff nurses. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl), 2022. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Thompson G, et al. The impact of transformational leadership and interactional justice on follower performance and organizational commitment in a business context. J Gen Manage. 2021;46(4):274–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alwali J, Alwali W. The relationship between emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and performance: a test of the mediating role of job satisfaction. Volume 43. Leadership & Organization Development Journal; 2022. pp. 928–52. 6.

- 31.Wang X, et al. Exploring the influence of the spiritual climate on psychological empowerment among nurses in china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagné M, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organizational Behav. 2005;26(4):331–62. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, et al. Locus of control, psychological empowerment and intrinsic motivation relation to performance. J Managerial Psychol. 2015;30(4):422–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amabile TM, et al. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad Manag J. 1996;39(5):1154–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arshadi Bostanabad M, et al. Clinical competency and psychological empowerment among ICU nurses caring for COVID-19 patients: A cross-sectional survey study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(7):2488–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James AH, et al. Nursing and values-based leadership: A literature review. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):916–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, et al. Leader humility and employees’ creative performance: the role of intrinsic motivation and work engagement. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1278755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bamford M, Wong CA, Laschinger H. The influence of authentic leadership and areas of worklife on work engagement of registered nurses. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2013;21(3):529–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludwig TD, Frazier CB. Employee engagement and organizational behavior management. J Organizational Behav Manage. 2012;32(1):75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slåtten T, Lien G, Mutonyi BR. Precursors and outcomes of work engagement among nursing professionals-a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juyumaya J. How psychological empowerment impacts task performance: the mediation role of work engagement and moderating role of age. Front Psychol. 2022;13:889936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng Q, Sun F. The impact of psychological empowerment on work engagement among university faculty members in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:983–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ni P, Chen J, Liu N. The sample size Estimation in quantitative nursing research. Chin J Nurs. 2010;45(4):378e80. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iacobucci D. Structural equations modeling: fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J Consumer Psychol. 2010;20(1):90–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; 2023.

- 46.Li-Chaoping S-K. The structure and measurement of transformational leadership in China. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2005;37(06):803. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li-Chaoping X, Shi-Kan C-X. Psychological empowerment: measurement and its effect on employees’ work attitude in China. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2006;38(01):99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Can Y. The Chinese version of Utrecht work engagement scale: an examination of reliability and validity. Chinese journal of clinical psychology; 2005.

- 49.Wang LT, Bao H, Wang L, Qian HC, Zhang Y. The development and application of nurse job performance scale. Chin J Practical Nurs. 2015;31:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abd-El-Fattah SM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications and programming. J Appl Quant Methods. 2010;5(2):365–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salameh B, et al. Alarm fatigue and perceived stress among critical care nurses in the intensive care units: Palestinian perspectives. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis AT. Transformational Leadership: Exploring Its Impact on Job Satisfaction, Job Performance, and Employee Empowerment. 2023.

- 54.Heinen M, et al. An integrative review of leadership competencies and attributes in advanced nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(11):2378–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu Q, et al. Head nurse ethical competence and transformational leadership: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khoshmehr Z, et al. Moral courage and psychological empowerment among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng L, Jin Y, Guo J. Mediating and/or moderating roles of psychological empowerment. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kato Y et al. Antecedents and outcomes of work engagement among psychiatric nurses in Japan. Healthc (Basel), 2023. 11(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Masood M, Afsar B. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior among nursing staff. Nurs Inq, 2017. 24(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Ginsburg L, et al. Measuring work engagement, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior among health care aides. Gerontologist. 2016;56(2):e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bae SH. Intensive care nurse staffing and nurse outcomes: A systematic review. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(6):457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu R, et al. The mediating role of psychological empowerment in perceptions of decent work and work immersion among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int Nurs Rev. 2024;71(3):595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.