Abstract

Proper brain function and overall health critically rely on the bidirectional communications among cells in the central nervous system and between the brain and other organs. These interactions are widely acknowledged to be facilitated by various bioactive molecules present in the extracellular space and biological fluids. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are an important source of the human neurosecretome and have emerged as a novel mechanism for intercellular communication. They act as mediators, transferring active biomolecules between cells. The fine-tuning of intracellular trafficking processes is crucial for generating EVs, which can significantly vary in composition and content, ultimately influencing their fate and function. Increasing interest in the role of EVs in the nervous system homeostasis has spurred greater efforts to gain a deeper understanding of their biology. This review aims to provide a comprehensive comparison of brain-derived small EVs based on their epigenetic cargo, highlighting the importance of EV-encapsulated non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in the intercellular communication in the brain. We comprehensively summarize experimentally confirmed ncRNAs within small EVs derived from neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes across various neuropathological conditions. Finally, through in-silico analysis, we present potential targets (mRNAs and miRNAs), hub genes, and cellular pathways for these ncRNAs, representing their probable effects after delivery to recipient cells. In summary, we provide a detailed and integrated view of the epigenetic landscape of brain-derived small EVs, emphasizing the importance of ncRNAs in brain intercellular communication and pathology, while also offering prognostic insights for future research directions.

Keywords: MiRNAs, LncRNA, CirRNA, Exosomes, Epigenetic, Brain

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny spherical structures enclosed by a phospholipid bilayer membrane, which are released by all eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells into the extracellular space. Under physiological conditions, EVs maintain central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis by facilitating communication between CNS cell populations. In response to CNS injury, EVs mediate stress-dependent responses and regulate tissue damage and repair, thereby influencing neurological disease pathogenesis, development, and recovery [1]. Cell-to-cell communication through secreted vesicles, particularly EVs, is a well-documented process in neurobiology. This form of communication facilitates the transfer of molecular signals over short and long distances within the nervous system, like hormones function across various physiological systems. As such, while the fundamental role of secreted vesicles in cell-to-cell communication is well-established in neurobiology, the broader understanding of their functions across different cell types and biological contexts is still evolving. Secreted vesicles, such as exosomes and microvesicles, carry bioactive molecules that influence cellular functions and interactions. Exosomes, which range from 30 to 150 nm in diameter, are formed as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) through the inward budding of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) within the cell (Fig. 1). These MVBs then fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing exosomes into the extracellular space. Conversely, microvesicles, also known as ectosomes or shedding vesicles, are a larger and very heterogeneous population, varying from 100 to 1000 nm (apart from apoptotic bodies bigger than 1 μm). They are released from the outward budding and fission of the cell's plasma membrane (Fig. 1) [2]. The interaction between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton plays a crucial role in the release and transfer of vesicles into the surrounding tissue (Fig. 1) [3]. The multitude of terms based on function, biogenesis, size, or cell of origin, the diversity of isolation methods and contexts, and the scarcity of validated biomarkers have resulted in numerous misconceptions and sometimes conflicting definitions for EVs in the scientific literature, including terms like supermers, exomers, migrasomes, and oncosomes [4]. In response to this challenge, the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) has called “extracellular vesicle” a generic nomenclature encompassing all kinds of vesicles released by cells. Additionally, the ISEV has published recommendations outlining the minimal requirements for studies focusing on EVs, which are regularly updated [5]. For example, EVs exhibit considerable heterogeneity, especially in cell types where MVBs contain ILVs of diverse sizes and compositions. Consequently, relying solely on features such as size and density as strict criteria for defining EVs is not viable. It is important to be cautious when utilizing isolation procedures and commercially available kits, as well as techniques like electron microscopy, flow cytometry, or nanoparticle tracking, because these methods often struggle to efficiently distinguish between differently sized EVs and membrane-free macromolecular aggregates. Utilizing multiple methods in parallel and employing complementary techniques such as ultracentrifugation, immunoblotting, and mass spectrometry can significantly enhance the quality of a study [6]. On the other hand, inconsistency in the methods used across different studies makes it very difficult to compare their results and decreases the reproducibility of findings.

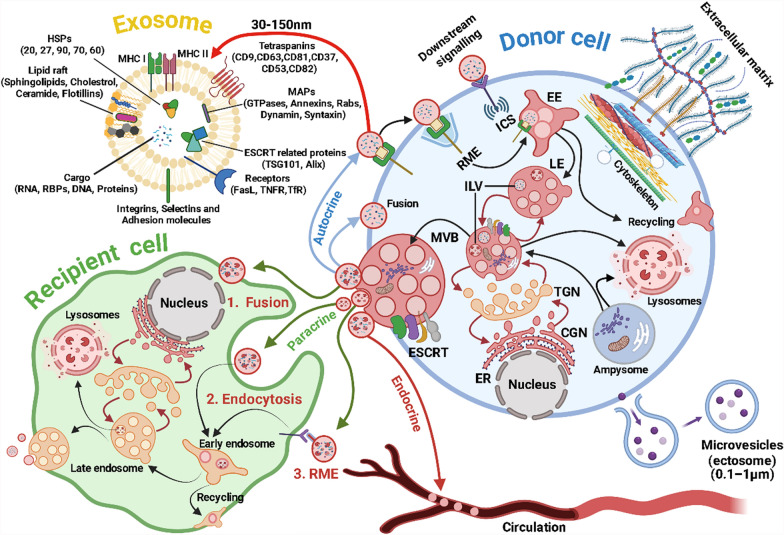

Fig. 1.

Communications between donor and recipient cells via exosomes. EVs released from donor cells can deliver their contents to recipient cells through three main pathways, including paracrine signaling (EVs are delivered to neighboring cells in the vicinity), endocrine signaling (EVs enter the bloodstream and are transferred throughout the body), and autocrine signaling (EVs are taken up by the same donor cell that released them). In each pathway, EVs can be taken up by recipient cells through fusion (directly merging with the plasma membrane of the recipient cell, and releasing contents into the cell), classic endocytosis (engulfed by the recipient cell through formation of vesicles), or receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME). Exosome content can be highly heterogeneous, including a variety of cargos such as nucleic acids and different kinds of proteins. Figure was created using BioRender (BioRender.com) and is used with permission

EVs encompass a wide assortment of molecular cargos comprising proteins, lipids, and various types of nucleic acids, such as DNA, mRNA, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), transfer RNA, ribosomal RNA, small interference RNAs (siRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs). NcRNAs such as miRNAs, circRNAs, siRNAs, and lncRNAs are essential for regulating gene expression and maintaining cellular function. MiRNAs engage in post-transcriptional regulation by binding to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or inhibition of their translation. The siRNAs are vital components of RNA interference, which silence gene expression by degrading mRNA post-transcriptionally. CircRNAs can function as miRNA sponges, modulate transcription, and interact with RNA-binding proteins. LncRNAs participate in various regulatory processes, including chromatin remodeling, transcription, and post-transcriptional modification, thus influencing gene expression at multiple levels. Collectively, these ncRNAs are crucial for genetic regulation and cellular homeostasis [7]. The selective sorting of these cargo molecules into EVs enables them to mirror the physiological condition and source of the originating cell.

Selective ncRNA sorting into EVs is influenced by several mechanisms, including post-transcriptional modifications (e.g., m6A methylation), RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), specific sequence motifs, and cellular stress responses. m6A modifications can enhance ncRNA recognition by RBPs like YTHDF family proteins, facilitating their packaging into EVs. Additionally, tetraspanins, hnRNPs, and AGO2 play crucial roles in sorting miRNAs, while ALIX and endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) complexes regulate RNA loading. These mechanisms impact EV functionality, influencing cell-to-cell communication, immune regulation, and disease progression by ensuring the selective transfer of biologically active ncRNAs to recipient cells [8].

Upon release, EVs can traverse body fluids, reaching specific target cells or tissues, where they transfer their cargos, influencing the function of their recipient cells (through either endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine signaling) (Fig. 1). EVs serve a vast range of functions, encompassing intercellular communication, immune modulation, tissue repair, and the transfer of genetic information. Their influence extends to critical processes such as immune responses, cell signaling, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration [9–11]. EVs in body fluids have gained attention as potential biomarkers for neurological disorders. Compared to existing diagnostic methods such as neuroimaging (MRI, PET scans), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and blood-based biomarkers, EV-based biomarkers offer several advantages, including non-invasive collection, the potential for early detection, and the ability to provide real-time insights into disease progression.

However, challenges remain in standardizing EV isolation and characterization to ensure reproducibility and clinical applicability. While CSF biomarkers (e.g., tau and amyloid-beta [Aβ] in Alzheimer’s disease [AD]) are highly specific, they require invasive lumbar punctures. In contrast, serum or plasma-derived EVs offer a minimally invasive alternative but may suffer from contamination with non-brain-derived EVs. Additionally, neuroimaging techniques provide structural and functional insights but lack molecular specificity, making EV-derived biomarkers a potentially complementary tool rather than a replacement [12]. For example, EV-mediated downstream intercellular signaling has been implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), AD, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS) [13–17]. Identifying crucial biomarkers for these conditions is paramount, as it can aid in developing disease-modifying treatments and enhance diagnostic accuracy. Given their diverse components, EVs present promising candidates for biomarker studies related to neuropathological conditions. A thorough analysis of the molecular cargos, particularly ncRNAs, carried by EVs can offer valuable insights into the state of disease responses to drugs and assist in identifying potential biomarkers [18]. Moreover, EVs hold great promise in drug delivery, as they can be engineered to transport specific cargos and precisely target recipient cells [19]. The blood–brain barrier (BBB) acts as a gatekeeper, preventing approximately 98% of therapeutic drugs from entering the CNS. Exosomes can cross the BBB through mechanisms like receptor-mediated transcytosis, adsorptive-mediated transcytosis, and inflammation-driven permeability changes. This ability makes them valuable for intercellular communication, biomarker transport, and potential therapeutic applications in neurological diseases. Their role in drug delivery is being explored, as they can carry molecules across the BBB to target brain disorders. Additionally, brain-derived exosomes may influence immune responses and disease progression by signaling to peripheral cells and transferring ncRNAs [19, 20]. This emerging field has opened up exciting possibilities for advancing diagnostics and therapeutic interventions. Moreover, under pathological conditions, the ncRNA cargos of brain-derived EVs (BDEVs) can profoundly affect neuronal and glial cell function, contributing to disease progression and offering potential therapeutic targets [20].

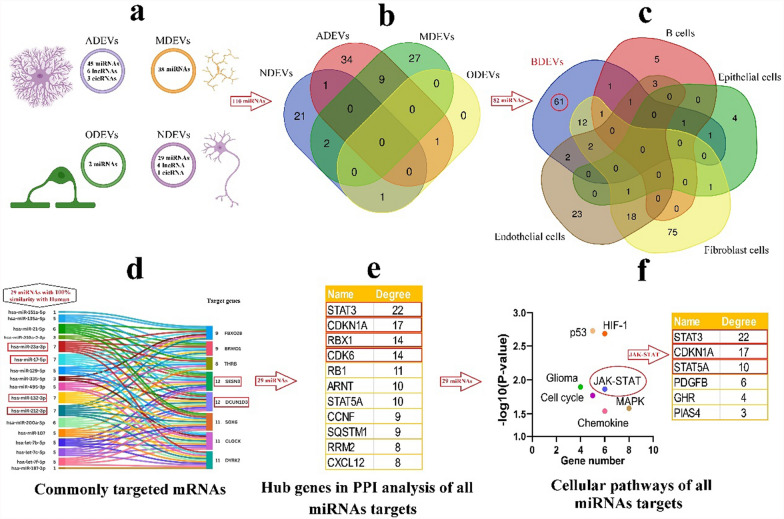

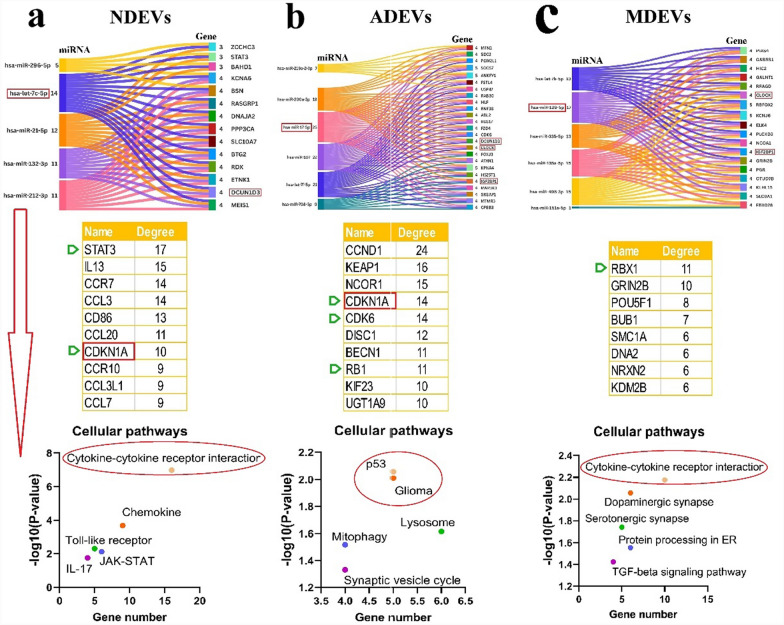

BDEVs can be categorized into four main groups based on their cellular origin: neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles (NDEVs), astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (ADEVs), microglia-derived extracellular vesicles (MDEVs), and oligodendrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (ODEVs). In this review, we aim to review experimentally validated cell-specific BDEVs and their enriched ncRNAs from various perspectives. During the purification process, larger EVs often remain in the final sample, leading to a mixed population of vesicles, despite a higher concentration of smaller EVs. We carefully use the term “small EVs (sEVs)” instead of “exosomes” in sections of the article where the study's methods cannot precisely identify the enrichment of such sEVs. However, we focus on the ncRNA cargos of sEV-enriched fractions, confirmed with specific protein markers, and collect these data for future evaluations. Subsequently, we use in silico analysis to predict the essential molecular targets associated with these ncRNAs to clarify how they may influence or contribute to pathological conditions.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We employed specific MeSH terms, including “extracellular vesicles” and “exosomes”, “non-coding RNAs”, “nerve cells”, “neurons”, “neuroglia cells”, “astrocytes”, “microglia”, “oligodendrocytes”, and “glioma” as search keywords in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 2014 to June 2024. The objective was to acquire relevant articles on nerve/neuroglia cell-derived EVs/exosomes and their ncRNA contents. We merged the titles obtained from the search databases according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Our review criteria included the following: original articles written in English that focused on EVs/exosomes associated with the CNS and evaluated their ncRNA content. We excluded reviews or other classifications apart from original articles and articles that lacked ncRNA function analysis or did not assess cell-specific EVs or related neuropathologic conditions. After eliminating duplicate articles and thoroughly scanning the remaining ones, we selectively chose articles in which ncRNAs were recognized for their roles in neurological disorders (based on abstract content). Subsequently, we read all full-text manuscripts and excluded those not meeting the inclusion criteria. During the reading process, we extracted the following information from the articles: observed changes in ncRNA expression, relevant disease, type of functional analysis, biological mechanism, source of EVs, and the method used to extract EVs. However, we could not conduct a meta-analysis due to the limited number of studies providing an exact mechanism of action for each ncRNA and the resulting low statistical power (power analysis is conducted using the G*Power 3.1.97 software). For instance, most studies focus on different aspects of ncRNA function, such as their role in gene regulation or involvement in cellular pathways. Variability in experimental methods, such as differences in EV extraction methods, RNA sequencing techniques, or cell models, may hinder comparison between studies.

In silico analysis

After selecting and compiling experimentally confirmed ncRNAs, we evaluated the functions of human miRNAs, animal miRNAs with 100% sequence similarity to human miRNAs, as well as human lncRNAs and circRNAs with confirmed available sequences, using the following bioinformatic tools. CircAtlas 3.0 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/circatlas) was used to predict the miRNA targets of circRNAs, utilizing TargetScan, miRanda, and Pita algorithms [21]. LncRNA and miRNA interactions were evaluated using the NPInter v4 database (http://bigdata.ibp.ac.cn/npinter), which compiles ncRNA interactions from CLIP-seq, PARIS, CLASH, ChIRP-seq, and GRID-seq experimentally validated data [22]. The MEINTURNET database (http://userver.bio.uniroma1.it/apps/mienturnet/) was used to predict miRNA gene targets, applying a significance threshold of P < 0.05 [23]. To identify cellular pathways influenced by miRNAs, the gene targets of miRNAs were submitted to the Enrichr database (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/), leveraging real experimental data. Pathways with significant enrichment (P < 0.05) were identified and analyzed [24]. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks for the gene targets of miRNAs were constructed using the STRING 12 database (https://string-db.org/) based on experimentally validated data. The resulting networks were downloaded and further analyzed with Cytoscape v3.10.1. Our analysis focuses on a curated set of experimentally verified ncRNAs rather than an unbiased, transcriptome-wide dataset. We acknowledge that our findings do not capture the entire range of EV-associated ncRNAs but instead provide insights into those validated in the existing literature. Rather than strictly categorizing ncRNAs as cell-type-specific, we identify them as enriched in certain cell types while acknowledging that they are not exclusively expressed in a single type. Moreover, we cross-referenced our findings with publicly available EV-ncRNA datasets to verify whether the identified miRNAs have been reported across multiple cell types. The EVmiRNA database (https://guolab.wchscu.cn/EVmiRNA/) was used to determine whether BDEV miRNAs overlapped with those reported in other cell-derived EVs. This database presents a detailed compilation of EV-associated miRNAs from various cell types and tissues.

EV biogenesis and release

Detecting and classifying EVs is challenging. However, EVs can be categorized into distinct subtypes based on their origin and composition. Exosomes and microvesicles (also known as ectosomes or shedding vesicles) are the most extensively studied EV subtypes. Exosomes are persistently released from all cells and display a notable enrichment of protein markers like tetraspanins, heat shock proteins, and ESCRT-related components (Fig. 1). Among them, tetraspanins are crucial in organizing membrane microdomains known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains by forming clusters and interacting with various transmembrane and cytosolic signaling proteins [25]. The ESCRT is a conserved protein complex present from yeasts to mammals, consisting of approximately 20 proteins grouped into four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) along with associated proteins (vacuolar protein sorting 4-A, vesicle trafficking 1, and ALG-2-interacting protein X). While ESCRT-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms play roles in protein trafficking to exosomes and exosome biogenesis, a complete understanding of these processes remains elusive. Specifically, the ESCRT-0 complex recognizes and captures ubiquitinated proteins on the endosomal membrane. ESCRT-I and -II complexes deform the membrane into buds containing the captured cargo, and ESCRT-III is responsible for vesicle scission (Fig. 1). Different members of the ESCRT machinery have been implicated in exosome biogenesis and secretion in various cell types [26]. The tumor suppressor protein p53 and its transcriptional target, tumor suppressor-activated pathway 6, have also been described to regulate exosome secretion, potentially linked to the ESCRT-III component charged multivesicular body protein 1 A [27]. This highlights the potential connections between signaling pathways and exosome biogenesis. Overall, the intricate involvement of the ESCRT machinery and associated proteins in exosome biogenesis underlines the complexity of this process, which still requires further exploration to unravel its precise mechanisms.

Resource, extraction, and tracking of sEVs

EVs can be derived from various sources, including tissues, cell culture supernatants, and biofluids like blood, saliva, urine, tears, mucus, CSF, and breast milk [28]. While in vitro studies using tissue and cell supernatant samples are less complicated, biofluids containing a complex mixture of EVs originating from various cell types are more accessible in human studies (Fig. 2). However, working with body fluid samples presents challenges due to the larger starting volumes, leading to dilution issues and low EV yield and purity. This challenge intensifies when isolating cell-type-specific EVs or specific EV subpopulations from biofluids. Therefore, an effective and clinically applicable EV isolation method should address the sensitivity to individual EV subpopulations, purity, throughput, reproducibility, standardization, scalability, and external validity across various clinical settings and samples [29].

Fig. 2.

Different methodologies and experiments can be integrated to comprehensively characterize exosomes. The cellular origin of EVs extracted from biological fluids can be determined through bioinformatic and computational analyses, by labeling them in individual cells before release or sorting them according to unique signatures during or after extraction. The signature of cell-specific EVs can be validated in vitro in cultures of primary cells or cell lines. Figure was created using BioRender (BioRender.com) and is used with permission

There is a wide range of established isolation methods, including ultracentrifugation, density gradient ultracentrifugation, size exclusion chromatography, immunoprecipitation via beads, field-flow fractionation, tangential flow filtration, nanofluidic deterministic lateral displacement, and acoustic trapping technology [30]. Identifying the specific organ source of EVs is complex due to the lack of unique and exclusive markers for each organ. Although no single marker is exclusive to any particular organ-derived EVs (organ-to-organ cross-talk), some markers may still provide clues about the tissue of origin. In the context of brain-derived sEVs, proteins such as growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43), neuroligin 3 (NLGN3), amphiphysin 1, neural cell adhesion molecule, L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM), glutamate aspartate transporter 1 (GLAST-1), and myelin oligodendrocytes glycoprotein (MOG) could be tentatively employed to identify neurons, astrocytes, or oligodendrocytes, respectively [1] (Fig. 2). While these markers are useful for identifying specific cellular origins of sEVs, they may not capture all potential cell types or pathological conditions from which EVs may be derived. Researchers can make educated guesses about the likely source by comparing the protein composition of sEVs to known cell-specific markers [31]. In this regard, markers such as aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) have not yet been evaluated in ADEVs. Moreover, it is recommended that other myelin-related proteins, myelin basic protein (MBP), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), and proteolipid protein (PLP) also be used in parallel with MOG to better characterize ODEVs. Identifying specific markers for MDEVs is indeed challenging, as they share many markers with other myeloid cells, complicating their distinct identification. However, the presence of transmembrane protein 119 (TMEM119) alongside Iba1 (ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1) in sEVs offers a promising strategy for considering these vesicles as MDEVs. These two markers are associated with microglial cells, which are key myeloid cells in the brain, suggesting that their co-presence in sEVs could be a valuable indication of microglial origin. While these are key markers for glial cells, they should be used in conjunction with other markers for more precise identification of EV cellular sources in some contexts.

Moreover, sEVs carry various types of RNAs, and some of them may be specific to certain cells. By analyzing the RNA content of sEVs, researchers can also infer their tissue origin or cellular origin [32]. In experimental settings, sEVs can be labeled with isotopes specific to a particular cell or tissue, allowing for tracking the sEVs and identifying their origins (Fig. 2) [33]. Computational methods, such as machine learning algorithms, can be applied to large datasets of sEV profiles to identify patterns associated with specific organs and help predict the most likely tissue source (Fig. 2) [34]. Additionally, utilizing tetraspanin-based pH-sensitive fluorescent reporters for live imaging enables quantification of the fusion rate between MVBs and the plasma membrane at the single-cell level (Fig. 2) [35].

It is important to recognize that identifying the exact cellular source of sEVs in complex biological samples like blood remains challenging. Multiple factors, such as the physiological state and the presence of numerous cell types, can influence the composition of sEVs. In vitro experiments conducted under various culture conditions or with the application of specific cellular stressors significantly influence the composition and release of EVs. This variation complicates the identification of reliable and unique markers for determining their cellular origins, particularly in complex biological samples. For example, changes in the microenvironment, such as nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, or inflammation, can alter the types of EVs released and their molecular cargo. This underscores the importance of selecting specific markers that are stable under the given experimental conditions. In some cases, using specific stressors or manipulating cell cultures to mimic disease conditions can provide more accurate insights into the biological roles of EVs and the cell types they derive from. To further enhance the standardization of research in this field, the EV-TRACK platform has been introduced. This platform aims to facilitate a more systematic reporting of EV biology and methodology, contributing to a clearer and more consistent understanding of this dynamic study area [36]. As research in this field progresses, new techniques and technologies may improve our ability to discern the origin of sEVs more accurately.

Synaptic vesicles and EVs in neuron communications

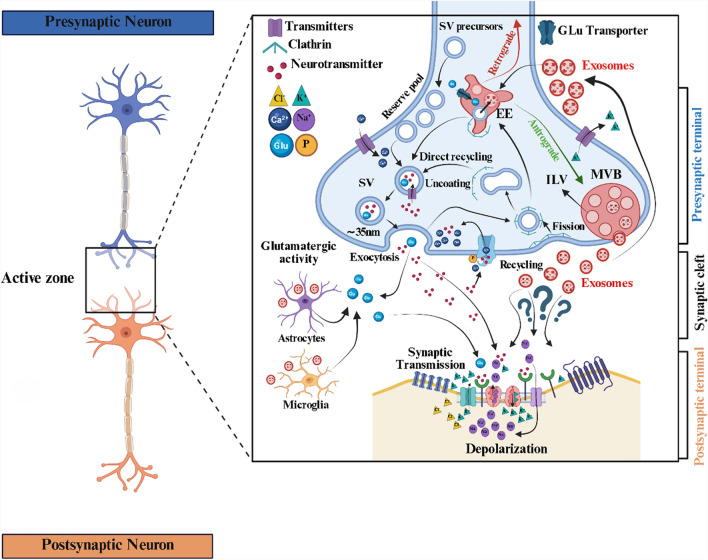

Both synaptic vesicles (about 40–50 nm) and neuron-derived exosomes (about 30–100 nm) are membrane-bound vesicles falling in the EVs category, involved in cellular communication in the synaptic cleft. Still, they differ in formation, cargo content, and function (Fig. 3). Synaptic vesicles are specific to neurons, formed within the nerve terminals (synaptic boutons), and primarily associated with the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft during synaptic transmission. The discovery of various RNAs, including ncRNAs, within synaptic vesicles adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of neuronal communication. While synaptic vesicles are traditionally associated with the release of neurotransmitters, the presence of RNA suggests a potential role in the transfer of genetic information between neurons during synaptic transmission [37]. The process of neurotransmission mediated by synaptic vesicles is fundamental for communication between neurons and is essential for various brain functions, including learning, memory, cognition, and behavior. Any disruption in the release, recycling, or reuptake of neurotransmitters via synaptic vesicles can lead to neurological disorders and synaptic dysregulation. NDEVs, on the other hand, originate from the endosomal system of neurons and can influence various cell types within the brain and beyond (Fig. 3) [38]. Calcium influx and the excitability of glutamatergic synapses can influence the release of NDEVs from well-differentiated neurons [39]. Isolating NDEVs through GAP43 (growth-associated protein 43) and NLGN3 immunocapture provides a robust, novel platform for biomarker development in AD. By this method, a study revealed elevated levels of p181-Tau, Aβ42, and neurogranin in NDEVs of AD patients [40]. The interactions of NDEVs with synaptic vesicles remain unknown, but understanding these interactions is crucial for deciphering the brain's complex workings and their impact on overall neurological health.

Fig. 3.

The role of brain-derived exosomes in the synaptic cleft. EVs, such as exosomes, exert various functions within the synaptic cleft, facilitating intercellular communication and potentially impacting synaptic function. They participate in the transmission of signaling molecules, clearance of neurotoxic proteins, modulation of neuroinflammatory responses, and regulation of synaptic development and plasticity. However, their confirmation remains elusive, as depicted by question marks in this illustration. Figure was created using BioRender (BioRender.com) and is used with permission

EVs in glial cell communications

Glial cells are involved in neuroinflammation and synaptic homeostasis and are essential for maintaining the physiological function of the CNS. Glial cell membranes play a vital role in brain homeostasis by providing ion channels (such as gap junction hemichannels, volume-regulated anion channels, and bestrophin-1), receptors (for neurotransmitters and cytokines), and transporters (like glutamate, glutamate/aspartate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid transporters) [41]. These components are involved in gliotransmission and the regulation of neuronal activity. Numerous studies have indicated that interactions between neurons and glial cells are closely associated with neurological diseases and could potentially be targeted for therapeutic interventions [42]. Therefore, communication between neurons and glial cells is essential for maintaining proper brain function and homeostasis. Recent research has demonstrated that glial cells release EVs carrying various bioactive molecules that travel through the extracellular space and are taken up by neighboring cells, including neurons [43]. The transfer of EVs between neurons and glial cells allows for the exchange of information and signaling molecules. These neuron-glia interactions via EVs have been implicated in various physiological processes, including synaptic plasticity, immune responses, and neuroprotection. Dysregulation of these interactions may also contribute to the pathogenesis of neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases.

EV-derived ncRNAs and their epigenetic function

Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and aberrant expression of ncRNAs, have been validated as active contributors to neurological disorders and promoters of disease progression [44]. EVs, including exosomes or sEVs, contribute significantly to intercellular communication, and their cargos, including ncRNAs, can indeed influence epigenetic regulation in recipient cells [45]. The analysis of exosomal ncRNAs has emerged as an innovative and non-invasive strategy for predicting disease progression [46]. The ncRNAs have been implicated in the development of several neurodegenerative disorders via epigenetic modifications [47]. The ncRNA cargo within circulating sEVs, along with free-circulating ncRNAs, functions as valuable biomarkers for a range of diseases and contributes significantly to critical biological processes, including immune regulation, antigen presentation, and cell-to-cell communication [48]. The miRNA-mediated gene silencing can profoundly affect cellular processes and contribute to epigenetic regulation. The miRNAs encapsulated in sEVs exhibit enhanced stability, allowing them to travel long distances in body fluids without degradation by extracellular nucleases. EVs may also carry proteins or molecules involved in epigenetic modifications. For example, they might transport DNA methyltransferases, histone modifiers, or other regulators of epigenetic processes. Moreover, post-transcriptional modifications may contribute to RNA sorting in EVs [49]. The content of EVs, beyond their quantity, displays distinctions between case and control studies. For example, sequencing of the EV-derived miRNAs from MS patients and healthy controls has revealed diverse signature biomarkers, allowing the differentiation of MS patients and those in different stages of the disease. For instance, nine miRNAs (−15b-5p, −23a-3p, −223-3p, −374a-5p, −30b-5p, −433-3p, −485-3p, −342-3p, −432-5p) have been identified to distinguish relapsing–remitting from progressive conditions [50]. Recently, scientists introduced an updated online database called exoRBase 2.0 (http://www.exoRBase.org), which is a repository of EV-derived ncRNAs such as lncRNAs (n = 15,645) and circRNAs (n = 79,084) from diverse human body fluids (∼1000 human blood, urine, CSF, and bile samples) analyzed by RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) method [51]. Unfortunately, this database only provides one brain sample (solid organ), and most data originate from blood samples linked to immune-related disorders. To expand data applicability beyond exoRBase 2.0, we propose integrating multiple databases such as EVAtlas, Vesiclepedia, and miRandola, which include EV-derived ncRNAs from various biofluids. Additionally, incorporating tissue-specific EV datasets (e.g., CSF, urine, tumor-derived EVs) and validating findings using GEO or TCGA transcriptomic data can enhance biological relevance. Experimental approaches like RT-qPCR, RNA-seq, and Nano-flow cytometry can further confirm bioinformatic predictions. Cross-species comparisons with animal models may also help validate evolutionary conservation and translational significance, ensuring a more comprehensive analysis of EV-derived ncRNAs.

NDEVs

Isolating EVs from the brains of human subjects, especially those with chronic neurological disease, is quite difficult due to the restriction on performing brain biopsies (except brain tumors). Available data are usually derived from postmortem samples (a rather small sample size) in which extensive cell damage has already occurred [52]. Neuroscience research has therefore focused on isolating and evaluating NDEVs, which are easily accessible by plasma or serum sampling. This is performed by first extracting total EVs, usually via differential ultracentrifugation, confirmation through assays including western blotting for transpanins, and then enriching for neuronal-specific markers like L1CAM, tubulin beta 3 class III (TUBB3), synaptosomal-associated protein, and GluR2/3 (glutamate receptor AMPA R2/3), using well-known antibodies [38, 53, 54]. L1CAM (or CD171), a transmembrane cell adhesion molecule involved in neuronal development, is frequently used among the various markers studied. However, its application as a marker for isolating NDEVs from liquid biopsies has been debated, with some evidence questioning its reliability [55]. Attention should also be paid to NDEVs extracted from the brain regions where adult neurogenesis occurs. For example, ongoing neurogenesis (if indeed taking place) and the presence of neuronal stem cells (NSCs) in the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles and the sub-granular zone of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus of the adult brain may lead to the extraction of polymorph EVs that can interfere with other EVs [56]. Recent studies focusing on the NSC-derived EVs show that enriched ncRNAs within them contribute to gene regulation in recipient cells, with lower immunogenicity and virtually no possibility of malignant transformation [57]. Therefore, this group of EVs may serve as a safer and more effective therapeutic strategy for neuropathologic conditions. As a new approach, future studies aiming to confirm the neuronal origin of EVs could enrich for at least two ncRNAs, miRNA-9 and miRNA-451a (notable brain-enriched miRNAs), or specific neuronal proteins (TUBB3 and L1CAM) to ensure the accurate selection of NDEVs [58].

miRNAs in NDEVs

Among all ncRNAs, miRNAs have been more extensively investigated. A recent study has confirmed that miRNA-132-3p and miRNA-212-3p exhibit a significant reduction in L1CAM-captured human plasma EVs derived from AD patients (n = 5), in comparison to high pathological controls (n = 5) and cognitively intact, pathology-free controls (n = 5) [58]. In contrast, two other NDEV-associated miRNAs, miR-451a and miR-9-5p, showed no substantial differences in expression levels. Additionally, miRNA-132-3p and miRNA-212-3p are highly enriched in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived human neurons, further supporting their potential role in neuronal function and disease pathology [58]. In AD, interestingly, tau protein has been detected in EVs from conditioned media of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons, as well as CSF and plasma of patients [59]. Furthermore, NSCs in the SVZ of neonatal CD-1 mice actively generate and release EVs that are highly enriched with specific miRNAs, including members of the miR-9 family, Let-7 family, miR-181 family, miR-26a-2, miR-6236, and miR-5112 [60]. When taken up by microglia, these EVs function as non-canonical microglial morphogens, influencing microglial development, activation, and function. Moreover, these miRNA-enriched EVs have been linked to the regulation of neurodevelopmental processes and are increasingly recognized for their potential contributions to neurodevelopmental disorders [60]. Furthermore, miRNA-124-3p has been identified as a NDEV-associated miRNA that can be transferred to astrocytes, where it plays a crucial role in regulating extracellular glutamate homeostasis. By modulating the expression of glutamate transporter-1 (GLT1), miR-124-3p contributes to synaptic activity and excitatory neurotransmission, ultimately maintaining neuronal function. Importantly, studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in miRNA-124-3p levels in the SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS, suggesting its involvement in disease pathology. The downregulation of miRNA-124-3p in ALS may lead to impairment of GLT1-mediated glutamate clearance, exacerbating excitotoxicity and contributing to neurodegeneration [61].

Moreover, studies utilizing sEVs reporter mice (CD63-GFPf/f) have provided valuable insights into the selective enrichment of specific miRNAs in neurons and NDEVs [62]. Several miRNAs, including miR-124-3p, Let-7c-5p, miR-149-3p, and miR-125b-5p, are abundantly expressed in neurons and their secreted EVs, indicating a potential role in intracellular and extracellular regulatory processes. Additionally, certain miRNAs, such as miR-7004-5p, miR-7666-5p, miR-296-5p, and miR-3109-5p, exhibit selective enrichment in NDEVs, suggesting their specific involvement in intercellular communication and signaling pathways unique to the extracellular environment [62]. Additionally, other miRNAs, including miR-669m-5p, members of the miR-466 family, miR-297a-5p, and miR-3082-5p, are found to be significantly enriched within NDEVs, further emphasizing the existence of distinct miRNA signatures associated with neuronal sEV-mediated signaling [62].

Among these miRNAs, miR-124-3p has been shown to modulate astrocytic function upon uptake. Specifically, miR-124-3p enhances the expression of GLT1 by suppressing inhibitory regulatory factors, thereby promoting efficient glutamate clearance from the extracellular space. This mechanism is crucial for maintaining synaptic homeostasis and preventing excitotoxicity, which is implicated in various neurodegenerative disorders [62]. Interestingly, elevated levels of miRNA-21a-5p in NDEVs have been associated with neuroinflammatory responses in the mouse brain, particularly following traumatic brain injury (TBI) [63]. This miRNA mediates neuron-to-microglia communication and contributes to the activation of microglial cells in response to neuronal damage [63]. Mechanistically, miRNA-21a-5p is transferred from injured neurons to microglia via NDEVs. miRNA-21a-5p enhances microglial activation by modulating TLR7 (Toll-like receptor 7) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and IL-1β. This cascade exacerbates neuroinflammation and may contribute to secondary injury processes in TBI [63].

Moreover, whole-transcriptome analysis of serum L1CAM-captured EVs has identified significant alterations in the expression profiles of non-coding RNAs in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This study revealed 11 dysregulated miRNAs, with the majority exhibiting downregulation compared to typically developing children of the same age group [64]. The most significantly altered miRNA was PC-5p-139289_26, which was absent in control samples from neurotypical children, indicating a possible ASD-specific regulatory function. Additionally, three other miRNAs (PC-3p-275123_15, PC-3p-38497_124, and PC-5p-149427_24) exhibited increased expression levels in ASD cases. In contrast, seven miRNAs, including hsa-miRNA-193a-5p, showed notable downregulation [64]. Further functional investigations are necessary to determine their specific contributions to ASD, which may ultimately pave the way for novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

In addition, miR-98 expression in the penumbra region remains elevated on the first day but significantly declines by the third day following ischemic stroke in rats, suggesting its role as an endogenous protective factor post-ischemia [65]. Overexpression of miR-98 inhibits platelet-activating factor receptor-mediated microglial phagocytosis, thereby reducing neuronal death. Additionally, after ischemic stroke, neurons secret EVs carrying miR-98 to microglia, protecting stressed but viable neurons from microglial phagocytosis [65].

The anti-inflammatory effects of hiPSC (human-induced pluripotent stem cell)-derived NSC-derived EVs (hNSC-EVs) on LPS-stimulated microglia are significantly reduced when protein pentraxin 3 (PTX3) or miR-21-5p levels are decreased in the EVs [66]. These findings suggest that hNSC-EVs can effectively modulate proinflammatory human microglia into a non-inflammatory phenotype, highlighting their potential for treating neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, the involvement of PTX3 and miR-21-5p in this process opens new possibilities for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of hNSC-EVs by overexpressing these factors [66].

Another study revealed that NDEVs facilitate functional recovery in a mouse model of spinal cord injury (SCI) by inhibiting M1 microglia and A1 astrocyte activation. MiRNA profiling identified miR-124-3p as the most abundant miRNA in these sEVs, with MYH9 identified as its downstream target. Furthermore, the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway is involved in the alterations of microglial dynamics caused by sEVs miR-124-3p [67] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies on neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles (NDEVs) and their non-coding RNA cargos in neuropathologic conditions

| ncRNA cargo | EV source (ncRNA detection method) | Proposed biological function (selection reason) | Functional evaluation | EV extraction method | Disease relation (~ FC) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-132-3p | L1CAM-captured human plasma and hiPSCs-derived neurons (microarray with qRT-PCR validation) | Potential diagnostic and theragnostic value (preliminary studies and confirmed group differences) | NC | UCF | AD (9-FC↓) | [58] |

| miR-212-3p | AD (4-FC↓) | |||||

| miR-9-5p | AD (unchanged) | |||||

| miR-451a | AD (unchanged) | |||||

| miR-181 family (a-1) | Primary CD-1 mice neonatal SVZ neural stem cells (small RNA sequencing) | A non-canonical microglial morphogen (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | Taken up by microglia, in silico, and gain/loss-of-function analysis (for Let-7 family) | DGUC | NDDs (NC↑) | [60] |

| mir-6236 | ||||||

| mir-5112 | ||||||

| miR-26a-3p | ||||||

| miR-9 family (−2) | ||||||

| Let7-family (c-3p) | ||||||

| miR-124-3p | Primary SOD193A mouse neurons (TaqMan® qRT-PCR) | Regulates extracellular glutamate levels and GLT1 expression (prior literature) | Taken up by astrocytes, gain-of-function, and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis | UCF | ALS (0.6-FC↓) | [61] |

| miR-7004-5p | Primary CD63-GFPf/+ mouse neurons (microarray with TaqMan® qRT-PCR validation) | miR-124-3p up-regulates the GLT1 expression by inhibiting factors (significantly abundant in neurons and confirmed group differences) | Taken up by astrocytes, gain/loss-of-function and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis (for 124-3p) | UCF | NGDs (56-FC↑) | [62] |

| miR-7666-5p | NGDs (45-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-296-5p | NGDs (32-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-3109-5p | NGDs (18-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-669m-5p | NGDs (2195-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-466f | NGDs (1260-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-297a-5p | NGDs (1024-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-3082-5p | NGDs (512-FC↑) | |||||

| Let7c-5p | NGDs (4390-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-124-3p | NGDs (4705-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-149-3p | NGDs (2896-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-125b-5p | NGDs (1176-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-21a-5p | Primary mouse neurons (miRNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | Neuroinflammatory, activating microglia (significantly abundant, colocalized with MAP2-expressing neurons) | Taken up by microglia | UCF | TBI (2.8-FC↑) | [63] |

| PC-5p-139289_26 | L1CAM-captured human serum (microarray and small RNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | A predictive biomarker involved in neuron-mediated glycosylation changes (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | In silico analysis | DGUC | ASD (11-FC↑) | [64] |

| PC-3p-275123_15 | ASD (12-FC↑) | |||||

| PC-5p-149427_24 | ASD (13-FC↑) | |||||

| PC-3p-38497_124 | ASD (20-FC↑) | |||||

| lncRNA-ENST000532430 | ASD (NC↑) | |||||

| lncRNA-CAND1.11 | ASD (NC↑) | |||||

| lncRNA-EPS15L1 | ASD (NC↑) | |||||

| miR-98 | Primary rat neurons (qRT-PCR) | Targets PAFR and prevents neuron phagocytosis (prior literature) | Taken up by microglia, and gain/loss-of-function | UCF | AIS (2-FC↓) | [65] |

| miR-21a-5p | hiPSCs-derived neurons (qRT-PCR) | Anti-inflammatory effects (prior literature) | Taken up by microglia, and loss-of-function | UCF (Kit) | NGDs (NC↓) | [66] |

| miR-124-3p | Primary mouse neurons (qRT-PCR) | Promotes functional recovery by targeting MYH9 (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | Taken up by microglia/astrocytes, and gain/loss-of-function and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis | UCF (Kit) | SCI (NC↓) | [67] |

| lncRNA-POU3F3 | L1CAM-captured human plasma (microarray with qRT-PCR validation) | Combined with β-glucocerebrosidase activity (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | NC | Microbeads | PD (2-FC↑) | [68] |

| CircOGDH | Plasma-derived and primary mouse neurons (RNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | A potential therapeutic target for ischemia (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | Loss-of-function, 3′-UTR luciferase, in-silico, and protein interaction analysis | UCF | AIS (54-FC↑) | [69] |

UCF, Ultracentrifugation; DGUC, Differential gradient ultracentrifugation; hiPSC, human-induced pluripotent stem cell; NDDs, Neurodevelopmental Diseases; NGDs, Neurodegenerative Diseases; AD, Alzheimer's disease; TBI, Traumatic brain injury; ASD, Autism spectrum disorder; PD, Parkinson's disease; AIS, Acute ischemic stroke; SCI, Spinal cord injury; FC, Fold change compared to control; NC, Not clarified, were included in the bioinformatics analysis as they exhibited 100% similarity with human sequences

LncRNAs and circRNAs in NDEVs

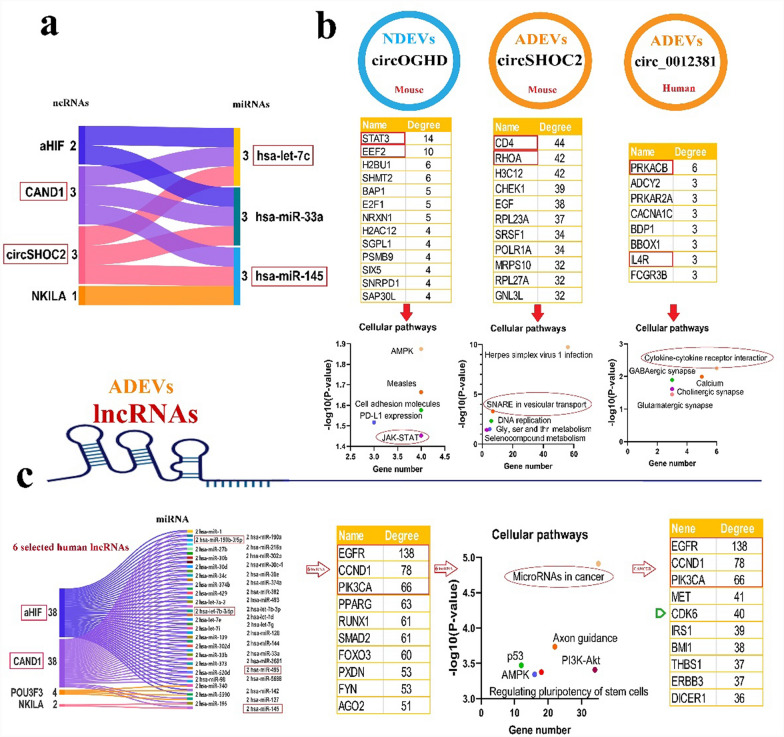

Analysis of serum L1CAM-captured EVs from ASD patients has identified 1745 differentially expressed lncRNAs compared to age-matched, typically developing children, with most showing downregulation [64]. Remarkably, ENST00000532430, CAND1.11, and EPS15L1 exhibit the most significant expression changes, indicating their potential role in ASD-related molecular mechanisms [64]. A study reported elevated levels of lncRNA-POU3F3 and α-synuclein in L1CAM sEVs, along with reduced glucocerebrosidase (GCase) activity in PD patients compared to controls [68]. These biomarkers showed significant variations based on gender, Hoehn-Yahr (H-Y) stage, and UPDRS-III scores. Importantly, lncRNA-POU3F3 levels in L1CAM sEVs exhibited a strong positive correlation with α-synuclein and a negative correlation with GCase activity in PD patients. Furthermore, L1CAM sEVs, lncRNA-POU3F3 levels, and GCase activity were significantly associated with PD severity, including motor and cognitive impairments. The combined assessment of lncRNA-POU3F3 and α-synuclein levels in L1CAM sEVs, along with GCase activity, effectively distinguished PD patients from healthy controls [68]. Moreover, the neuronal-derived CircOGDH (circular RNA derived from oxoglutarate dehydrogenase) has been identified to be highly expressed in plasma EVs of patients following acute ischemic stroke compared to individuals without cerebrovascular diseases. The interaction between CircOGDH and miRNA-5112 resulted in increased expression of the alpha4 (IV) chain of collagen IV, contributing to neuronal damage. Notably, knockdown of CircOGDH led to a significant improvement in neuronal cell viability under ischemic conditions [69] (Table 1).

ADEVs

Astrocytes are fundamental to neural function in health and disease. Within neuron-astrocyte networks, their perisynaptic processes act as sensors, responding to neurotransmitters and gliotransmitters through volume transmission. Astrocytes also support neural functions in the CNS and mediate inflammatory responses from microglia. Growing evidence highlights their role in maintaining brain homeostasis in response to pro-inflammatory factors in infectious and neurodegenerative diseases [70]. However, the precise mechanisms of transcellular communication remain unclear. Transcellular communication plays a crucial role in diffuse signaling, where receptor activation is not strictly localized, yet can exert substantial effects on overall brain function. This process modulates neural activity by clearing glutamate and releasing gliotransmitters [70]. Additionally, these processes contribute to regulating the volume of the extracellular space and synaptic coverage [71].

There is a growing understanding of EVs as signal vehicles in the CNS, serving as a mode of non-synaptic communication [72]. ADEVs released into the bloodstream hold the potential as markers for stress-induced diseases and CNS disorders. As noted above, despite their promise as biomarkers, challenges exist in accurately categorizing sEVs and determining their source, which impacts their function [73]. Recent research has identified GFAP-positive EVs from astrocytomas in the blood, which may offer the potential for glioma sub-classification [74]. ADEVs, found in peripheral organs during neuroinflammatory conditions or after brain focal radiation, may serve as biomarkers for various pathological conditions and contribute to brain-to-periphery signaling by targeting peripheral organs [75].

miRNAs in ADEVs

EVs associated with astrocytes are central to the regulation of neuronal morphology, function, ion homeostasis, and inflammatory response. Dysregulation of ADEVs is implicated in various CNS diseases. A study examining the orbitofrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia (SCZ) (n = 29), bipolar disorder (BD) (n = 26), and unaffected controls (n = 25) revealed a significant increase in miR-223 that targets glutamate receptors. Noteworthy, the miR-223 expression was inversely correlated with its target genes, including glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA-type subunit 2B (GRIN2B) and glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA-type subunit 2 (GRIA2), suggesting its potential role in inhibiting glutamatergic signaling in psychiatric disorders [76]. Further analyses demonstrated that miR-223 is highly expressed in astrocytes and is actively secreted via EVs, with its expression modulated by antipsychotic drugs [76]. Functional studies revealed that adding miR-223-enriched astrocytic EVs to neuronal cultures led to a significant increase in miR-223 levels, accompanied by a marked reduction in GRIN2B and GRIA2 expression, reinforcing its regulatory role in glutamate receptor signaling. These findings highlight miR-223 as a key astrocytic-derived miRNA that may contribute to synaptic dysfunction in SCZ and BD, particularly in individuals with a history of psychosis [76].

ADEVs play a crucial role in the intercellular transfer of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-targeting miRNAs and facilitate communication between astrocytes and metastatic tumor cells [77]. Importantly, studies have shown that selectively depleting PTEN-targeting miRNAs in astrocytes or inhibiting ADEV secretion restores PTEN expression and effectively suppresses brain metastasis in vivo, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway [77]. Further investigations have identified miR-19a, a microRNA highly enriched in astrocytic EVs, as a key regulator of PTEN expression in brain tumor cells. The uptake of miR-19a-containing astrocytic EVs by metastatic cancer cells leads to PTEN downregulation, thereby enhancing tumor cell survival, proliferation, and colonization within the brain [77]. Studies have demonstrated that the astrocyte expressing the stress-regulated enzyme Aldolase C (Aldo C) releases EVs that are subsequently taken up by hippocampal neurons. Interestingly, the Aldo C-containing EVs exhibit a higher ability to reduce dendritic complexity of developing hippocampal neurons compared to EVs from control astrocytes [78]. Bioinformatics and biochemical analyses further revealed that the elevated Aldo C levels correlate with increased miRNA-26a-5p content in astrocytes and their secreted EVs. Notably, neurons transfected with a miRNA-26a-5p mimic showed reduced expression of proteins involved in neuronal morphogenesis and exhibited morphological changes similar to those induced by Aldo C-containing EVs [78]. These findings highlight that ADEVs loaded with miRNA-26a-5p regulate neuronal morphology and synaptic transmission through specific molecular targets.

Other studies have shown that ADEVs released in response to inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α exhibit a significantly altered miRNA profile. Importantly, these ADEVs are enriched with miRNA-125a-5p and miRNA-16-5p, which target neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 3 and its downstream effector B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), critical for neurotrophic signaling [79]. The downregulation of these targets in neurons correlates with reduced dendritic growth, decreased dendritic complexity, and diminished neuronal excitability, as evidenced by lower spike rates and burst activity. However, blocking miRNA-125a-5p and miRNA-16-5p prevented these adverse effects, preserving dendritic architecture and neuronal firing patterns [79]. A recent study also indicates that pathogenic ADEVs derived from SOD1G93A astrocytes reduce motor neuron (MN) survival, neurite length, and neurite branching. Among the dysregulated miRNAs in astrocyte EVs, miRNA-155-5p plays a pivotal role in the neurotoxicity, likely through its effects on inflammatory pathways and neuronal survival mechanisms [80]. In another study, ADEVs exhibit significant alterations in their miRNA cargos following astrocyte exposure to brain extracts from TBI mice, with over 20 miRNAs being upregulated. Among them, miRNA-873a-5p has been identified as a key regulator of astrocyte-microglia interactions. Further analysis confirmed that miRNA-873a-5p attenuates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and improves neurological deficits post-TBI by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of miRNA-873a-5p in modulating neuroinflammation and promoting recovery in TBI patients [81]. Furthermore, ADEVs enriched with miR-200a-3p prevent cell death in 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP⁺)-treated SH-SY5Y cells and glutamate-treated hippocampal neurons through down-regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4), reinforcing its role in mitigating neurotoxicity in in vitro PD models [82]. miRNA target analysis and reporter assays confirmed that miR-200a-3p directly targets MKK4 by binding to two distinct sites on the 3′-UTR of Map2k4/MKK4 mRNA. Treatment with a miR-200a-3p mimic effectively suppressed MKK4 mRNA and protein expression, leading to reduced cell death in MPP-treated SH-SY5Y cells and glutamate-treated hippocampal neuron cultures [82].

The regulatory role of ADEVs in modulating neuronal autophagy has been extensively investigated. To model ischemic injury, the mouse hippocampal neuronal cell line (HT-22) was cultured under oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) conditions. Remarkably, ADEVs facilitate the transfer of miRNA-190b, which plays a neuroprotective role by inhibiting OGD-induced apoptosis and autophagy in neuronal cells [83]. Mechanistically, miRNA-190b exerts its protective effects by targeting autophagy-related 7 (ATG7), a key regulator of the autophagic process. By suppressing ATG7, ADEV-loaded miR-190b effectively reduces autophagy activation in response to ischemic stress, thereby preventing excessive neuronal cell death. These findings highlight the potential therapeutic significance of ADEVs in modulating neuronal survival pathways and suggest that miRNA-190b could serve as a promising target for neuroprotection in ischemic brain injury (IBI) [83]. Moreover, ADEVs play a neuroprotective role by transporting miRNA-17-5p, which has been shown to mitigate hypoxic-ischemic brain injury (HIBI) in neonatal rats. In in vivo and in vitro models, ADEVs enriched with miR-17-5p improved neurobehavioral performance and decreased cerebral infarct size, neuronal apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Mechanistically, miR-17-5p binds to BCL2-interacting protein 2 (BNIP2) mRNA, leading to its downregulation in OGD cells, thereby enhancing neuronal survival. Furthermore, overexpression of miR-17-5p in H19-7 hippocampal neurons significantly increased cell viability and reduced OGD-induced apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Conversely, BNIP2 overexpression reversed these protective effects. These findings highlight the miR-17-5p/BNIP2 axis as a potential therapeutic target for mitigating HIBI [84].

LncRNAs in ADEVs and glioma-derived extracellular vesicles (GDEVs)

ADEVs enriched with NF-κB interacting long non-coding RNA (NKILA) exert a neuroprotective effect. This protection is facilitated by the interaction between the lncRNA NKILA and miRNA-195, which typically suppresses autophagy by targeting the nod-like receptor X1 (NLRX1). The regulatory crosstalk within the NKILA/miRNA-195/NLRX1 axis significantly influences cellular response mechanisms, thereby contributing to neuronal protection following TBI [85]. In the glioma microenvironment, considerable evidence shows active communication between tumor cells and their surroundings via sEVs, influencing key glioma characteristics [86]. For example, Bian and colleagues uncovered a key mechanism by which GDEVs drive astrocyte activation. They found that GDEVs transport lncRNA activated by transforming growth factor beta (lnc-ATB) to astrocytes, facilitating malignant cell invasion and migration. Importantly, lnc-ATB downregulates miR-204-3p in an Argonaute 2-dependent manner. This suppression leads to astrocyte activation, which, in turn, enhances the migratory and invasive potential of glioma cells. These findings highlight the crucial role of lncRNA-ATB in shaping the glioma microenvironment through sEV-mediated intercellular communication, providing new insights into glioma progression and potential therapeutic targets [87].

Furthermore, Dai et al. discovered that GDEVs overexpressing lncRNA AHIF, which is the natural antisense transcript of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), contribute to glioblastoma progression and resistance to radiation therapy. Further biochemical analysis revealed that the lncRNA AHIF regulates factors linked to migration and angiogenesis in sEV, highlighting its involvement in tumor development and adaptation to hypoxic conditions [88]. Similarly, Qiu et al. reported that sEVs enriched with lncRNA-AHIF are significantly upregulated in the serum of patients with endometriosis. Their findings suggest that this lncRNA plays a crucial role in promoting angiogenesis, a key process associated with the progression of endometriosis [89].

Other studies have highlighted the crucial roles of lncRNA colon cancer-associated transcript 2 (lncRNA-CCAT2) and lncRNA POU Class 3 Homeobox 3 (lncRNA-POU3F3) in glioma-associated angiogenesis. GDEVs can transfer lncRNA-CCAT2 to endothelial cells, where it promotes angiogenesis by activating vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ). Functional studies further demonstrated that lncRNA-CCAT2 overexpression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) upregulates VEGFA and TGFβ, increases Bcl-2 expression, and inhibits Bax and caspase-3, thereby reducing apoptosis. Conversely, downregulation of lncRNA-CCAT2 has the opposite effect [90]. Similarly, GDEVs facilitate angiogenesis by transferring lncRNA-POU3F3 to endothelial cells. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) can efficiently internalize exosomes derived from A172 cells (A172-Exo), resulting in a significantly higher level of lncRNA-POU3F3 compared to cells treated with shA172-Exo. Functionally, A172-Exo exhibited better activity in enhancing HBMEC migration, proliferation, and tubular-like structure formation in vitro, as well as arteriole formation in vivo [91]. These findings underscore the critical role of GDEV lncRNAs in modulating the tumor microenvironment and promoting angiogenesis.

Moreover, lncRNA sequencing in murine astrocytes identified sEV lncRNA 4933431K23Rik (lncRNA 49Rik) as a key regulator in mitigating TBI-induced microglial activation both in vitro and in vivo, ultimately improving cognitive function [92]. Integrated miRNA and mRNA sequencing, along with binding prediction analysis, demonstrated that the sEV lncRNA 49Rik upregulates E2F7 and TFAP2C expression by sponging miR-10a-5p. As transcription factors, E2F7 and TFAP2C further modulate Smad7 expression in microglia. Adeno-associated virus-mediated overexpression of Cx3cr1-Smad7 in microglia effectively suppressed neuroinflammation and alleviated cognitive impairment following TBI [92]. Mechanistically, overexpressed Smad7 directly binds with IκBα, inhibiting its ubiquitination and preventing NF-κB signaling activation [92]. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of lncRNA 49Rik in sEVs in modulating neuroinflammatory responses and mitigating cognitive impairment following TBI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies that specifically evaluated ADEVs and GDEVs as well as their non-coding RNA cargos in neuropathologic conditions

| ncRNA cargo | EV source (ncRNA detection) | Proposed biological function (selection reason) | Functional evaluation | EV extraction method | Disease relation (~ FC) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-223-3p | Primary mouse cortical astrocytes (NanoString with TaqMan® qRT-PCR validation) | Targets glutamate receptors (significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by neurons, gain-of-function analysis | UCF | SCZ and BD (8-FC↑) | [76] |

| miR-19a | Primary mouse astrocytes (TaqMan® qRT-PCR) | Decreases PTEN expression (prior literature, significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by tumor cells, in silico, and gain-of-function analysis | UCF | Brain cancer (3.5-FC↑) | [77] |

| miR-26a-5p | Primary rat astrocytes (TaqMan® qRT-PCR) | Regulates astrocytic enzyme Aldolase C (prior literature, significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by neurons, in silico, and gain/loss-of-function analysis | UCF | NGDs (50-FC↑) | [78] |

| miR-23a | Primary rat astrocytes (microarray with TaqMan® qRT-PCR validation) | Increased by IL-1β; 125a-5p and 16-5p target NTKR3 and its downstream effector Bcl2 (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | Taken up by neurons, in silico, gain/loss-of-function, and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis (for 125a-5p and 16-5p) | UCF | NID (unchanged) | [79] |

| miR-16-5p | NID (2-FC↑) | |||||

| Let7f-3/5p | NID (3-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-100 | NID (2.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-125a-5p | NID (3.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-125b-5p | NID (2-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-23a | Increased by TNFα; 125a-5p and 16-5p targeted NTKR3 and Bcl2 (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | NID (unchanged) | ||||

| miR-16-5p | NID (2-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-145 | NID (3.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-107-3/5p | NID (2.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-23a | Increased by ATP (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | NID (unchanged) | ||||

| miR-532-5p | NID (2.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-544-3p | NID (4.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-21a-5p | NID (2.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-598-5p | NID (3.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-501-5p | NID (2.5-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-155-5p | Primary SOD1G93A rat astrocytes (qRT-PCR) | Contributes to motor neuron death (prior literature, significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by motor neurons, in silico, and loss-of-function analysis | UCF | ALS (3.5-FC↑) | [80] |

| miR-582-3p | ALS (2-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-873a-5p | Primary mouse astrocytes (microarray) | Inhibits NF-κB pathway (preliminary studies and confirmed group differences) | Taken up by microglia, in silico, and gain-of-function analysis | UCF | TBI (0.5–1.5-FC↑) | [81] |

| miR-1224-5p | NC | NC | ||||

| miR-708-5p | ||||||

| miR-383-5p | ||||||

| miR-218-2-3p | ||||||

| miR-551b-3p | ||||||

| miR-873a-3p | ||||||

| miR-219a-2-3p | ||||||

| miR-128-1-5p | ||||||

| miR-128-3p | ||||||

| miR-124-3/5p | ||||||

| miR-544-5p | ||||||

| miR-7240-5p | ||||||

| miR-137-3/5p | ||||||

| miR-138-5p | ||||||

| miR-7055-3p | ||||||

| miR-382-3p | ||||||

| miR-3099-5p | ||||||

| miR-200a-3p | Primary mouse astrocytes (small RNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | Decreased by MPP, prevents apoptosis via down-regulation of MKK4 (significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by SH-SY5Y cells and neurons, in silico, and gain/loss-of-function and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis | UCF | PD (1.79-FC↓) | [82] |

| miR-150-5p | Expression affected by MPP | NC | PD (1-FC↓) | |||

| miR-138-5p | PD (1-FC↓) | |||||

| miR-222-3p | PD (2.27-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-423-3p | PD (2.17-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-182-5p | PD (2.07-FC↑) | |||||

| miR-190b-5p | Inhibits oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced autophagy and neuronal apoptosis by targeting Atg7 (prior literature) | Taken up by HT-22 cells and hippocampal neurons, gain/loss-of-function and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis | UCF | IBI (3-FC↑) | [83] | |

| miR-17-5p | Primary rat cortical astrocytes (qRT-PCR) | Reduces neuronal oxidative stress by suppressing BNIP-2 expression (prior literature) | Taken up by H19-7 cells, injected into the HIBD rat model, gain/loss-of-function, 3′-UTR luciferase, and RNase treatment analysis | UCF | HIBD (2-FC↑) | [84] |

| lncRNA-NKILA | Human brain astrocytes (qRT-PCR) | Alleviates injury by binding to miR-195 and upregulating NLRX1 (prior literature) | Taken up by neurons, gain/loss-of-function, 3′-UTR luciferase, and RIP analysis | UCF | TBI (NC↓) | [85] |

| lncRNA-ATB | HGCL (A172 and U251) (qRT-PCR) | Suppresses miR-204-3p in an Ago2-dependent manner (prior literature) | Taken up by astrocytes, gain-of-function, 3′-UTR luciferase, and RIP analysis | UCF (Kit) | Glioma (2.5/4.5-FC↑) | [87] |

| lncRNA-aHIF | HGCL (U87-MG, U251-MG, A172 and T98G) (qRT-PCR) | Promotes radioresistance by targeting HIF-1α (prior literature) | Gain/loss-of-function analysis | UCF (Kit) | Glioma (NC↑) | [88] |

| lncRNA-CCAT2 | HGCL(U87-MG, U251-MG, A172 and T98G) (qRT-PCR) | Promotes angiogenesis via activation of VEGFA and TGFβ (prior literature) | Taken up by HUVECs, gain/loss-of-function analysis | UCF | Glioma (9-FC↑) | [90] |

| lncRNA-POU3F3 | HGCL(U87-MG, U251-MG, A172 and T98G) (qRT-PCR) | Regulates glioma angiogenesis (prior literature) | Taken up by HBMECs, gain/loss-of-function analysis | UCF | Glioma (6.5-FC↑) | [91] |

| lncRNA-49Rik | Primary mouse astrocytes (RNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | Up-regulates E2F7 and TFAP2C expression by sponging miR-10a-5p (significantly abundant, with confirmed group differences) | Taken up by microglia, gain/loss-of-function, and 3′-UTR luciferase | UCF (Kit) | TBI (5-FC↑) | [92] |

| circSHOC2 | Primary mouse astrocytes (qRT-PCR) | Suppresses apoptosis by acting on the miR-7670-3p/SIRT1 axis (prior literature) | Taken up by neurons, gain/loss-of-function, and 3′-UTR luciferase, and RIP analysis | UCF | IBI (2.5-FC↑) | [93] |

| circRNA-ATP8B4 | U-251MG cells (qRT-PCR) | Promotes radioresistance by sponging miR-766 (prior literature) | In silico analysis | UCF | Glioma (2.5-FC↑) | [94] |

| circ_0012381 | HGCL(U87-MG, U251-MG) (RNA-seq with qRT-PCR validation) | Induces M2 polarization by sponging miR-340-5p to increase ARG1 expression (significantly abundant, confirmed group differences) | Taken up by microglia, gain/loss-of-function, in silico, and 3′-UTR luciferase analysis | UCF (Kit) | Glioma (2.5-FC↑) | [95] |

UCF, Ultracentrifugation; DGUC, Differential gradient ultracentrifugation; NGDs, Neurodegenerative Diseases; PD, Parkinson's disease; TBI, Traumatic brain injury; ALS, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; HGCL, Human glioma cell lines; SCZ, Schizophrenia; BD, Bipolar disorder; NID, Neuroinflammatory diseases; IBI, Ischemic brain injury; ~ FC, approximately Fold change expression compared to control; HIBD, Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Damage; NC, Not clarified, The highlighted wells were included in the bioinformatics analysis as they exhibited 100% similarity with human sequences

circRNAs in ADEVs

A recent study reported that circSHOC2, a circRNA derived from ischemic-preconditioned ADEVs, acts as a neuroprotective agent in ischemic stroke by inhibiting neuronal autophagy [93]. SHOC2 protein plays a key role in modulating the ERK1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) pathway by forming a holophosphatase complex that activates RAF (rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma) protein. In an in vitro oxygen–glucose deprivation model and an in vivo mouse middle cerebral artery occlusion model, delivery of circSHOC2-enriched EVs improved cellular viability, reduced infarct volume, and alleviated neurobehavioral deficits. Further analysis revealed that the sEV circSHOC2 could be transferred to neurons, inhibiting apoptosis and promoting autophagy by sponging miRNA-7670-3p, increasing sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) levels. Notably, these protective effects were specific to ischemic conditions rather than normal physiological states [93]. In a separate study, another circRNA, circRNA-ATPase phospholipid transporting 8 B4 (circRNA-ATP8B4), was found in radioresistant GDEVs and contributed to glioma radioresistance by acting as a competitive endogenous RNA for miRNA-766. The circRNA-ATP8B4 is transferred from radioresistant EVs to normal glioma U251 cells, where it functions as a miR-766 sponge, ultimately promoting cell survival under radiation exposure [94]. These findings highlight the significant role of sEV circRNAs in neuroprotection and glioma adaptation under pathological stress conditions.

Moreover, radiation-exposed GDEVs significantly promote M2 microglia polarization, which, in turn, enhances the proliferation of irradiated glioblastoma cells [95]. The circ_0012381 is significantly upregulated in irradiated glioblastoma cells and transferred to microglia via sEVs. Within microglia, circ_0012381 facilitates M2 polarization by sponging miR-340-5p, leading to increased ARG1 expression. These M2-polarized microglia exhibit reduced phagocytic activity and support glioblastoma cell growth through the CCL2/CCR2 signaling axis. Importantly, compared to radiotherapy alone, combined inhibition of sEV release significantly suppressed glioblastoma growth in a zebrafish model [95] (Table 2).

MDEVs and their ncRNA content

Microglia, immune cells in the CNS, play pivotal roles in the onset and progression of neuropathologic conditions. Microglia manifest two primary polarized forms: pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2. The M1 microglia express, among other inflammatory mediators, IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α, while the M2 phenotype microglia release IL-4, IL-10, and TGFβ. Recent studies suggest that the activation state of microglia shapes the composition of MDEVs, regulating neuronal function, activating other cells, and controlling cell differentiation [96, 97]. In neuropathologic conditions, microglia, with a dual protective-detrimental role, utilize EVs to modulate various brain cells, including resident, infiltrating, and tumor cells, through long-range diffusion in the CNS. MDEVs carry proteins typically found in late endosomes, strongly suggesting that they originate from sEVs. Furthermore, MDEVs display major histocompatibility complex class II molecules, transpanins, Flotillin 1, and monocyte/macrophage marker CD14, which is often used for characterization [98].

miRNAs in MDEVs

A recent study demonstrated significant alterations of miRNA-124-3p levels in MDEVs at different stages (acute, sub-acute, and chronic) following repetitive mild TBI [99]. In a mouse model of TBI, intravenously injected microglial sEVs were selectively taken up by neurons in the injured brain. Notably, miR-124-3p was successfully transferred from these sEVs into hippocampal neurons, where it alleviated neurodegeneration through modulation of the Rela/Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) signaling pathway. Additionally, in vitro studies further confirmed the protective effects of microglial EVs enriched with miRNA-124-3p. Neurons subjected to repetitive scratch injuries exhibited reduced neurodegeneration when treated with these sEVs. Mechanistically, miRNA-124-3p targets RelA, a transcription factor known to inhibit ApoE. Since ApoE plays a crucial role in promoting the breakdown of amyloid-beta (Aβ), its upregulation following miR-124-3p intervention leads to reduced Aβ accumulation and associated neurotoxicity [99].

Moreover, increased levels of miRNA-155 were detected in MDEVs following heat stroke, suggesting a critical role of miRNA-155 in mediating neuronal response to thermal stress. Upon transfer into neurons, these miRNA-155-enriched EVs induce neuronal autophagy by directly targeting Ras homolog enriched in the brain (Rheb), a key activator of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway [100]. By suppressing Rheb expression, miRNA-155 effectively inhibits the mTORC1 activity, which is a central regulator of cell growth, survival, and autophagy. This disruption of mTORC1 signaling results in excessive autophagy activation, leading to neuronal stress and potential neurodegeneration [100].

Recent transcriptional analysis of MDEVs derived from LPS-activated microglia identified a significant upregulation of miRNA-615-5p. miRNA-615-5p specifically binds to the 3′UTR of myelin regulatory factor (MYRF), a crucial transcription factor responsible for regulating myelination in oligodendrocyte lineage cells [101]. Mechanistically, EVs released from activated microglia facilitate the transfer of miRNA-615-5p into oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). After internalization, miRNA-615-5p directly targets MYRF, resulting in inhibition of OPC differentiation and maturation [101].

Research has identified that ethanol exposure triggers neuroimmune pathology by promoting the release of let-7b/high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) complexes within MDEVs [102]. These EVs facilitate the transfer of let-7b/HMGB1 to neighboring neurons, contributing to hippocampal neurodegeneration. This highlights a potential link between chronic alcohol consumption and neuroinflammation, which may be critically involved in the progression of alcohol-related brain damage and the pathology of alcoholism [102].

Inflammatory microglia release EVs enriched with miR-146a-5p, which regulates key synaptic proteins [103]. This microglia-enriched miRNA, absent in hippocampal neurons, suppresses presynaptic synaptotagmin-1 (Syt1) and postsynaptic neuroligin-1 (Nlg1) in neurons, impairing synaptic stability. Blocking EV–neuron interaction or using EVs depleted of active miR-146a-5p prevents this effect, highlighting the role of miR-146a-5p in neuroinflammation and synaptic dysfunction [103]. Moreover, miR-146a-5p transferred via MDEVs reduces the frequency and amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic currents while decreasing dendritic spine density [104]. Additionally, overexpression of miR-146a-5p in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) suppresses neurogenesis and reduces excitatory neuron activity by directly targeting Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4). Conversely, downregulation of miR-146a-5p restores adult neurogenesis in the DG and alleviates depression-like behaviors in rats. Interestingly, circRNA ANKS1B functions as a miRNA sponge, sequestering miR-146a-5p and modulating KLF4 expression, thereby regulating neurogenesis and depression-like behaviors [104].

MDEVs also transmit signals to cancer cells, altering glioma metabolism by reducing lactate, nitric oxide, and glutamate (Glu) release [105]. Additionally, MDEVs influence Glu homeostasis by upregulating the expression of Glu transporter Glt-1 in astrocytes. These effects are primarily driven by miR-124 contained within MDEVs. In vivo studies demonstrate that MDEVs significantly reduce tumor mass and prolong survival in glioma-bearing mice, with miR-124 playing a crucial role in these therapeutic effects [105].