Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate baseline carboxyhemoglobin saturation (SpCO) values in smokers and to show the relationship between SpCO and age, years smoking, cigarettes per day, and nicotine dependence. We also analyzed the changes in carboxyhemoglobin in the body during active smoking.

Methods

This prospective cohort study involved 136 outdoor smokers and 60 controls who had never smoked. SpCO, heart rate (HR), and oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) values were recorded with a CO-oximeter device before, during, and two minutes after smoking. Changes during active smoking were analyzed, and all parameters were compared between smoking and non-smoking groups. Age, BMI, years smoking, cigarettes per day, and Fagerström nicotine dependence (FTND) level were correlated with baseline SpCO.

Results

The mean age of smokers was 32.3 years (70.6% male; 22.79% with comorbidities), while the mean age of non-smokers was 36.7 years (38.3% male). The SpCO and HR were significantly higher during (p = 0.006, p < 0.001) and after (p = 0.015, p < 0.001) smoking than the pre-cigarette levels. There was a significant difference between smokers (3.07) and non-smokers (1.77) in terms of baseline SpCO (p < 0.001). Correlation analysis showed that age, years smoking, and nicotine dependence were positively correlated with baseline SpCO. In the ROC analysis, the AUC value for SpCO was 0.705 and the optimal cut-off value was 1.50. In addition, 83% of smokers had a baseline SpCO value below 5%.

Conclusion

In this study, the baseline SpCO values of smokers were found to be approximately 200% higher than those of non-smokers. In addition, SpCO and HR increased during active smoking. However, 83% of smokers had a baseline SpCO below 5% and just 2 (1.47%) smokers had a baseline SpCO value above 9%, suggesting that the intoxication level of 9% in smokers should be reconsidered.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, Carbon monoxide, Poisoning, Carboxyhemoglobin, SpCO

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO)—a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas—is released as a result of incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons and poses a serious danger that is invisible to the naked eye. CO binds to hemoglobin 240 times more than oxygen, causing tissue hypoxia [1]. It is thought that there are around 30,000 − 50,000 emergency room admissions each year due to CO poisoning [2]. This number is expected to be much higher in undeveloped countries. Patients present to the emergency department with nonspecific symptoms such as nausea, headache, dyspnea, weakness, palpitations, and dizziness. Therefore, CO poisoning cases are likely to be missed, especially in crowded emergency departments. Since CO is also an environmental toxin, its diagnosis is also important for other individuals who may be affected by the CO present in the environment.

Diagnosis of CO poisoning used to be routinely performed by emergency clinicians with invasive blood tests. However, the development of the multiwave pulse CO-oximeter has provided a non-invasive, easy, and rapid method. The working principle of these devices is based on the transmission of different wavelengths of light during blood flow, which measures carboxyhemoglobin saturation (SpCO) [3–5]. Comparison of SpCO obtained from CO-oximetry with carboxyhemoglobin obtained from blood sampling has been done in previous studies and its accuracy has been confirmed [6, 7]. The noninvasive and easily applicable nature of the device enables easy screening in emergency departments and has been shown to detect unexpected CO exposures [8].

However, baseline CO levels remain insufficiently investigated. While levels above 2 − 3% are considered to signify CO intoxication in non-smokers, the cut-off value for smokers is currently unclear owing to the variability of baseline SpCO levels due to smoking. Some studies show that the baseline SpCO level in smokers is below 9%. However, current guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still recommend a SpCO level of 9% as the threshold value [8–10].

In this study, we investigated baseline SpCO levels in smokers using a CO-oximetry device. We also recorded dynamic SpCO levels during and after active smoking and examined the relationship of smoking-related carboxyhemoglobin kinetics with time.

Methods

Study design and setting

Following the approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Decision Date: 03.11.2021, Decision Number: 2021/247), this prospective cohort study was conducted between January 2023 and January 2024 on volunteer subjects who were active smokers. The research team, who were waiting in the open smoking area around our hospital, identified and approached people who were about to smoke and briefly informed them about the study. Volunteers underwent measurements just before, during, and two minutes after smoking. Smokers under 18 years of age, indoor smokers, people who refused to participate in the study, and people who did not want to wait after smoking were excluded from the study.

Data collection and processing

Masimo Rad 57 CO-oximeter (Masimo Inc., Irvine, CA) with fingertip sensor was used for the measurements. In all subjects, a single device was placed on the index finger for the duration of the assessment. This model has been used in many previous studies. SpCO, SpO2, and heart rate (HR) were measured before smoking, during (halfway through) smoking, and two minutes after smoking. Age, gender, years smoking, cigarettes per day, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities were also collected. The subjects were also administered the Fagerström nicotine dependence (FTND) test. The 60 subjects who never smoked and were approached outdoors served as the control group and their SpCO, SpO2, and HR were recorded as described above.

Outcomes

Baseline SpCO, HR, and SpO2 values of smokers and non-smokers were compared, while for smokers comparisons were also made across the SpCO, HR, and SpO2 values obtained before, during, and two minutes after smoking. The relationship between baseline SpCO values and age, BMI, years smoking, cigarettes per day, and FTND scores was also investigated.

Statistical analysis

Normality of the numeric data was tested with the Shapiro − Wilk test, and the Mann − Whitney U test was used to compare non-normal variables between two independent groups. To compare numerical variables between two dependent groups, differences between the pairs were calculated, and paired samples t-test and Wilcoxon test was performed for normal and non-normal pair differences, respectively. Pearson chi-squared and Fisher’s exact chi-squared tests were conducted to compare categorical variables between independent groups. Mean ± standard deviation and median (Q1 − Q3) values were given as the descriptive statistics for numerical data. Categorical data were presented as frequencies (n) and percentages. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the relationship between baseline SpCO, HR, and SpO2, and other numerical variables, including age, BMI, years smoking, cigarettes per day, and total FTND score. To determine the effect of smoking status (smoker or non-smoker) as a risk factor for the baseline SpCO > 5%, logistic regression analysis was performed, adjusting for gender and age. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed and area under the ROC curve (AUC) was estimated to examine the performance of SpCO, HR, and SpO2 in discriminating between smokers and non-smokers and to identify a significant cut-off value (p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant). Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.0 software.

Results

Of the 165 smokers that initially agreed to participate in the study, 29 were excluded for various reasons (e.g., not waiting for the post-cigarette SpCO measurement, not smoking the entire cigarette, immediately switching to the second cigarette). As a result, the data pertaining to 136 (69.39%) smokers and 60 (30.61%) non-smoker volunteers (controls) were retained for analysis. Demographic data, including age, sex, and smoking habits, are given in Table 1. While the mean age of smokers was 32.35 ± 11.66 years, the mean age of non-smokers was 36.75 ± 14.80 years, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.027). There were 96 (70.6%) males and 40 (29.4%) females among smokers, and 23 (38.3%) males and 37 (61.7%) females among non-smokers (p < 0.001). For the smokers, the mean number of years smoking and the mean number of cigarettes per day were 13.13 ± 10.97 years and 18.93 ± 10.32, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and smoking habits of smokers and non-smokers

| Variable | Smokers (n = 136) |

Non-smokers (n = 60) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male* | 96 (70.59) | 23 (38.33) | < 0.001 |

| Age [years]# | 32.35 ± 11.66 | 36.75 ± 14.80 | 0.027 |

| Years smoking# | 13.13 ± 10.97 | 0 | - |

| Cigarettes per day# | 18.93 ± 10.32 | 0 | - |

Data given with the *n (%) or #mean ± standard deviation

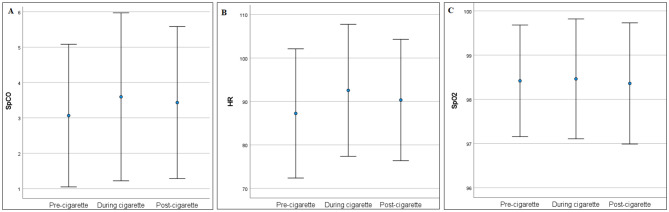

SpCO, HR, and SpO2 measurements were obtained pre-cigarette, during smoking, and two minutes after smoking (post-cigarette) from all smokers (n = 136 for all sessions). The SpCO levels and the HR were significantly higher during the cigarette-smoking session (p = 0.006 and p < 0.001) and post-cigarette session (p = 0.015 and p < 0.001) than in the pre-cigarette session (Table 2; Fig. 1). We also measured SpCO, HR, and SpO2 for the non-smokers. There was a significant difference between smokers and non-smokers in terms of baseline SpCO (p < 0.001), HR (p = 0.002), and SpO2 (p = 0.004). These measurements were significantly higher in smokers than in non-smokers (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Table 2.

SpCO, HR and SpO2 levels of smokers in pre-cigarette, during cigarette and post-cigarette

| Variables | Pre-cigarette (I) |

During cigarette (II) |

Post-cigarette (III) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-II | I-III | ||||

| SpCO | 3.07 ± 2.02 | 3.60 ± 2.37 | 3.43 ± 2.15 | 0.006 | 0.015 |

| HR | 87.26 ± 14.87 | 92.57 ± 15.19 | 90.35 ± 13.96 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| SpO2 | 98.42 ± 1.26 | 98.46 ± 1.35 | 98.36 ± 1.37 | 0.595 | 0.506 |

Data given with the mean ± standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Error-bars for pre-cigarette, during cigarette, post-cigarette A) SpCO, B) HR and C) SpO2 levels for smokers (Circle represents mean and bars represent 1 standard deviation)

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline spco, HR and SpO2 levels between smokers and non-smokers

| Variables | Smokers (n = 136) |

Non-smokers (n = 60) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCO | 3.07 ± 2.02 | 1.77 ± 1.32 | < 0.001 |

| HR | 87.26 ± 14.87 | 80.83 ± 14.58 | 0.002 |

| SpO2 | 98.42 ± 1.26 | 97.62 ± 1.86 | 0.004 |

Data given with the mean ± standard deviation

Fig. 2.

Error-bars for SpCO, HR and SpO2 for smokers and non-smokers (Circle represents mean and bars represent 1 standard deviation)

Mean total score on the FTND test was 4.19 ± 2.92 for the smokers. There were 47 (34.56%) smokers with very low, 28 (20.59%) with low, 16 (11.76%) with moderate, 25 (18.38) with high, and 20 (14.71%) with very high nicotine dependence (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for the Fagerström nicotine dependence test

| FTND test | Descriptive statistics | |

|---|---|---|

| Total score* | 4.19 ± 2.92 | |

| Very low dependence | 47 (34.56) | |

| Categories# | Low dependence | 28 (20.59) |

| Moderate dependence | 16 (11.76) | |

| High dependence | 25 (18.38) | |

| Very high dependence | 20 (14.71) | |

Data presented with *mean ± standard deviation, or #n (%)

Mean BMI of the smokers was 25.44 ± 3.83 kg/m2 and 31 (22.79%) individuals in this group had at least one comorbidity. Correlation analyses indicated a positive relationship between baseline SpCO and age (r = 0.242, p = 0.005), years smoking (r = 0.260, p = 0.002), and total FTND score (r = 0.173, p = 0.044), indicating that older age, longer smoking duration, and greater nicotine dependency were associated with higher baseline SpCO levels for the smokers. Correlations between baseline SpCO and BMI (r = 0.119, p = 0.166) and baseline SpCO and number of cigarettes smoked daily (r = 0.073, p = 0.400) were not significant. There was a negative correlation between HR and age (r=-0.329, p < 0.001), and between HR and years smoking (r=-0.335, p < 0.001), indicating that older age and longer smoking duration were associated with lower baseline HR for the smokers (Table 5).

Table 5.

SpCO, HR and SpO2 correlation with smoking habits and demographics of the smokers

| Variables | SpCO | HR | SpO2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | |

| Age | 0.242 | 0.005 | -0.329 | < 0.001 | 0.154 | 0.074 |

| BMI | 0.119 | 0.166 | -0.129 | 0.135 | -0.138 | 0.110 |

| Years smoking | 0.260 | 0.002 | -0.335 | < 0.001 | 0.182 | 0.034 |

| Cigarettes per day | 0.073 | 0.400 | 0.023 | 0.793 | -0.056 | 0.514 |

| FTND-total score | 0.173 | 0.044 | -0.033 | 0.706 | -0.022 | 0.797 |

FTND: Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, r: Correlation coefficient

No statistically significant difference was found between smokers with and without comorbidities in terms of baseline SpCO (p = 0.448), HR (p = 0.072), and SpO2 (p = 0.972) levels. (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of baseline SpCO, HR and SpO2 levels between those with and without comorbidities

| Variables | Without comorbidity (n = 105) |

With comorbidity (n = 31) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCO | 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 0.448 |

| HR | 88.50 ± 15.10 | 83.03 ± 13.44 | 0.072 |

| SpO2 | 99.00 (98.00–99.00) | 99.00 (98.00–99.00) | 0.972 |

Data presented with mean ± standard deviation or median (Q1-Q3)

We also performed ROC curve analysis to assess the effectiveness of SpCO, HR, and SpO2 (measured at baseline for smokers) in discriminating between smokers and non-smokers. The AUC for SpCO was 0.705, which was statistically significant, and the optimal cut-off value was 1.50. The AUC values for HR and SpO2 were also statistically significant but lower (Table 7; Fig. 3).

Table 7.

ROC curve analysis results for the spco, HR and SpO2

| Variables | AUC | p-value | cut-off value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCO | 0.705 | < 0.001 | 1.50 | 0.809 | 0.467 |

| HR | 0.637 | 0.002 | 79.50 | 0.721 | 0.533 |

| SpO2 | 0.627 | 0.004 | 98.50 | 0.522 | 0.700 |

AUC: Area under the ROC curve

Fig. 3.

ROC curves for the SpCO, HR and SpO2 in discriminating between smokers and non-smokers

We found that 113 (83.09%) of the smokers had SpCO ≤ 5%, and 134 (98.53%) had SpCO ≤ 9%. There was a significant difference between smokers and non-smokers in terms of proportions with SpCO ≤ 5%, but not for SpCO ≤ 9% (Table 8).

Table 8.

Comparison of smokers and non-smokers in terms of baseline SpCO groups

| Baseline SpCO | Controls | Smokers | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 5% | 57 (95.00) | 113 (83.09) | 0.023 |

| > 5% | 3 (5.00) | 23 (16.91) | |

| ≤ 9% | 60 (100.00) | 134 (98.53) | 1.000 |

| > 9% | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.47) |

We performed binary logistic regression analysis to predict baseline SpCO category (≤ 5% / >5%) by taking an indicator of smoking as an independent variable and adjusting for age and gender (Omnibus test for the model: p = 0.043, Hosmer − Lemeshow test: p = 0.672). According to the obtained findings, smokers were 4.596 times more likely to have baseline SpCO levels above 5% than non-smokers (OR = 4.596, p = 0.023). Gender (p = 0.846) and age (p = 0.133) did not emerge as significant predictors of baseline SpCO (Table 9).

Table 9.

Results of the logistic regression analysis for predicting baseline SpCO groups

| Variables | p-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Smoking status (RC: Non-smokers) | 0.023 | 4.596 | 1.237 | 17.071 |

| Gender (RC: Female) | 0.846 | 1.095 | 0.441 | 2.717 |

| Age | 0.133 | 1.024 | 0.993 | 1.057 |

RC: Reference category, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Dependent variable: SpCO groups (category (≤ 5% /> 5%)

Independent variable: Smoking status (smoker/non-smoker), gender (male/female) and age (years)

p-value for the model: p = 0.043 for the Omnibus test, p = 0.672 for the Hosmer & Lemeshow test

Discussion

We believe that this prospective cohort study conducted on healthy volunteer subjects provides important information on the effect of smoking on carboxyhemoglobin levels. The study provides information about the baseline SpCO values of smokers, while also offering insight into the carboxyhemoglobin changes that occur in the human body during smoking.

CO enters the human body through respiration. The amount of CO absorbed is directly related to the CO concentration in the inhaled air, the amount of ventilation per minute, and the duration of exposure. Inhaled CO binds to iron molecules in hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome C [11]. CO toxicity can present in a variety of forms, ranging from mild symptoms to coma. The illness severity is related to the degree of CO exposure and comorbidities [12]. It should be kept in mind that delayed neurologic sequelae may occur in addition to acute effects. Cigarette smoke is also an important source of CO as it contains about 3.5% CO [13].

In the present study, SpCO and HR values were found to be significantly higher during smoking and two minutes after smoking than before smoking, suggesting that carboxyhemoglobin levels in the blood increase during and after smoking. The increase in HR may be explained by the activation of the sympathetic system due to stress in metabolism and tissue hypoxia. Similarly, in a study conducted on 85 smokers, Schimmel et al. showed that SpCO levels increased during and after smoking [14]. Some older studies with a limited number of subjects have also presented results supporting those obtained in the present study [15, 16].

A standard threshold value must be determined for the CO-oximetry test to be interpreted and used correctly. Currently, no standard threshold has been established. While the exposure limit for SpCO in non-smokers has been set at > 2–3%, some studies have shown that smokers generally have SpCO levels below 9% [8]. In studies conducted, the average COHb levels in active smokers were found to be around 4.45%, while in non-smokers, this rate was 1.6% [17]. In our study, baseline SpCO and HR values of smokers were significantly higher than those of non-smokers (smokers: SpCO = 3.07, nonsmokers: SpCO = 1.77, p < 0.001). In the ROC analysis, the AUC value for SpCO was 0.705, while the optimal cut-off value was 1.5. This was expected, given that smoking causes a chronic increase in the metabolic carboxyhemoglobin levels, leading to an increase in baseline SpCO. Over time, it causes tachycardia due to changes in vascular and pulmonary structures, which explains the difference in HR. However, it should be noted that, although the 9% limit of CO intoxication for smokers is typically cited in the literature, 98.5% of smokers in this study had a baseline SpCO below 9% and 83.1% had a baseline SpCO below 5%. These findings suggest that the 9% intoxication threshold for smokers should be re-examined and additional studies are needed. It is suggested that with SpCO values in the 5 − 9% range should be examined in the clinic more carefully to assess their presenting symptoms and level of CO intoxication. Schimmel et al. also raised this issue and reported similar findings [14].

Correlation analysis showed that older age, longer smoking duration, and greater nicotine dependence were associated with higher baseline SpCO levels for smokers. However, BMI and number of cigarettes smoked per day were not significantly associated with their baseline SpCO values. Schimmel et al. showed that there was no significant correlation between pre-cigarette SpCO and age, years smoking, number of cigarettes smoked per day, or number of cigarettes smoked on the day of measurement. However, recent smoking was closely associated with baseline SpCO [14]. On the other hand, Roth et al. showed that the number of cigarettes smoked per day was an independent predictor of baseline SpCO [7].

In this study, cardiopulmonary diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, COPD, coronary artery disease, and heart failure were present in 22.7% of smokers. However, there was no statistically significant difference in baseline SpCO, HR, and SpO2 between smokers with and without comorbidities. Several authors cautioned that SpCO may be elevated in asthma and COPD, but the link between specific conditions and increased carboxyhemoglobin levels is insufficiently investigated [18, 19].

Limitations

As our study participants were recruited via convenience sampling, although the aim was to assess the typical smoking population, our subjects appeared to be healthier and younger. There was a notable difference between smokers and the control group in terms of gender. Moreover, the information on smoking habits was self-reported and may be inaccurate. Obviously, obtaining carboxyhemoglobin values via blood gas analysis would provide more reliable results, but since this is an invasive procedure, CO-oximetry was preferred. Longer observation of post-smoking SpCO values would provide more accurate information about the kinetics of smoking-induced carboxyhemoglobin, but the subjects’ unwillingness to wait after smoking led us to limit this period to two minutes. Since the assumptions were not met, confounding effects could not be adequately addressed by performing multivariate linear regression analysis for the numerical variables. We believe that additional multicenter studies with larger samples are needed to more accurately determine baseline SpCO in smokers.

Conclusion

The ability to use CO-oximetry as a screening tool for suspected CO poisoning in a larger population is certainly an advantage over blood gas analysis. However, the results obtained in this study suggest that the threshold value for smokers should be reconsidered, because 83.1% of smokers had a baseline SpCO below 5%. In smokers, baseline SpCO was associated with age, years of smoking, and FTND level. In addition, SpCO values considerably increased during active smoking, and the baseline SpCO values of smokers were approximately 200% higher than those of non-smokers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Deniz Sığırlı from Bursa Uludağ University for her help in the statistical analysis of our article.

Author contributions

SK: Data collection, conceived and designed the study, paper write-up.TA: Statistic analyses, discussion and proofreading.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research has not received any specific support from any funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. Ethics Committee approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Balikesir University (Date: 03.11.2021; Issue: 2021/247). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Megas IF, Beier JP, Grieb G. The history of carbon monoxide intoxication. Med (Kaunas). 2021;57(5):400. 10.3390/medicina57050400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chenoweth JA, Albertson TE, Greer MR. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(3):657–72. 10.1016/j.ccc.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikkanen H, Skolnik A. Diagnosis and management of carbon monoxide poisoning in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13(2):1–14. quiz 14. PMID: 22164402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bledsoe BE, Nowicki K, Creel JH Jr, Carrison D, Severance HW. Use of pulse co-oximetry as a screening and monitoring tool in mass carbon monoxide poisoning. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010 Jan-Mar;14(1):131–3. 10.3109/10903120903349853. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Roth D, Hubmann N, Havel C, Herkner H, Schreiber W, Laggner A. Victim of carbon monoxide poisoning identified by carbon monoxide oximetry. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(6):640–2. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker SJ, Curry J, Redford D, Morgan S. Measurement of carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin by pulse oximetry: a human volunteer study. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(5):892–7. 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00008. Erratum in: Anesthesiology. 2007;107(5):863. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Roth D, Herkner H, Schreiber W, Hubmann N, Gamper G, Laggner AN, Havel C. Accuracy of noninvasive multiwave pulse oximetry compared with carboxyhemoglobin from blood gas analysis in unselected emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1):74–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suner S, Partridge R, Sucov A, Valente J, Chee K, Hughes A, Jay G. Non-invasive pulse CO-oximetry screening in the emergency department identifies occult carbon monoxide toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2008;34(4):441–50. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical guidance for carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning after a disasters 2014. Available at: http://emergency.cdc.gov/disasters/co_guidance.asp

- 10.Neilsen BK, Aloi J, Sharma A. Acute carbon monoxide poisoning secondary to cigarette smoking in a 40-Year-Old man: A case report. Am J Addict. 2019;28(5):413–5. 10.1111/ajad.12939. Epub 2019 Jul 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forbes WHSF, Roughton FJW. The rate of carbon monoxide uptake by normal men. Am J Physiol. 1945;143:594–608. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aubard Y, Magne I. Carbon monoxide poisoning in pregnancy. BJOG. 2000;107(7):833–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajdos P, Conso F, Korach JM, Chevret S, Raphael JC, Pasteyer J, Elkharrat D, Lanata E, Geronimi JL, Chastang C. Incidence and causes of carbon monoxide intoxication: results of an epidemiologic survey in a French department. Arch Environ Health. 1991 Nov-Dec;46(6):373–6. 10.1080/00039896.1991.9934405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schimmel J, George N, Schwarz J, Yousif S, Suner S, Hack JB. Carboxyhemoglobin levels induced by cigarette smoking outdoors in smokers. J Med Toxicol. 2018;14(1):68–73. 10.1007/s13181-017-0645-1. Epub 2017 Dec 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronow WS, Rokaw SN. Carboxyhemoglobin caused by smoking Nonnicotine cigarettes. Effects in angina pectoris. Circulation. 1971;44(5):782–8. 10.1161/01.cir.44.5.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolova-Djokić L, Milosević S, Skrbić R, Salabat R, Voronov G, Igić R. Pulse carboxyhemoglobin-oximetry and cigarette smoking. J BUON. 2011 Jan-Mar;16(1):170–3. [PubMed]

- 17.Osakue NO, Okonkwo CW, Onah EC, Onyenekwe CC, Osakue NE, Njoku CM, Ehiaghe FA, Obi CU, Ihim AC, Onyenekwe AJ. Evaluation of blood levels of carbon monoxide in smokers in Nnewi metropolis. Int J Res Innov Appl Sci (IJRIAS) 2024;9(7):706–10. 10.51584/IJRIAS.2024.907059

- 18.Naples R, Laskowski D, McCarthy K, Mattox E, Comhair SA, Erzurum SC. Carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin in asthma. Lung. 2015;193(2):183–7. 10.1007/s00408-015-9686-x. Epub 2015 Feb 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasuda H, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, Ebihara S, Sasaki T, Okinaga S, Inoue D, Asada M, Nemoto M, Sasaki H. Increased arterial carboxyhemoglobin concentrations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(11):1246–51. 10.1164/rccm.200407-914OC. Epub 2005 Mar 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.