SUMMARY

Extraembryonic endoderm stem cells (XENs) resemble the primitive endoderm of blastocyst and provide valuable alternatives for understanding hypoblast development and building stem cell-based embryo models. Here, we report that a chemical cocktail (FGF4, BMP4, IL-6, XAV939, and A83–01) enables the de novo derivation and long-term culture of bovine XENs (bXENs) from blastocysts. Transcriptomic and epigenomic analyses confirm the identity of bXENs and reveal that bXENs resemble the hypoblast lineages of early bovine peri-implantation embryos. Furthermore, we show that bXENs maintain the stemness of expanded embryonic stem cells (EPSCs) and prevent them from undergoing differentiation. The chemical cocktail sustaining bXENs also facilitates the growth of epiblasts in developing pre-implantation embryos. Finally, 3D assembly of bXENs with bovine EPSCs and trophoblast stem cells enables efficient generation of blastoids that resemble blastocysts. bXENs and blastoids established here represent accessible in vitro models for understanding embryogenesis and improving reproductive efficiency in domestic livestock.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Ming et al. report a robust and efficient protocol for the derivation of bovine XENs from blastocysts. Importantly, this study also demonstrates the utility of bovine XENs in elucidating the mechanistic features of bovine pre-implantation development and generating an improved bovine blastoid for the creation of novel assisted reproductive technologies.

INTRODUCTION

During mammalian pre-implantation development, the first lineage differentiation specifies the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE) in the blastocyst; the ICM further differentiates into epiblast and hypoblast (or primitive endoderm). Subsequently, hypoblast or primitive endoderm gives rise to the yolk sac and is critical to support early conceptus development by producing a spectrum of serum proteins, generating early blood cells, and transporting nutrient from the uterus to the embryo.1–3 The development of hypoblast is a very conserved process although its developmental timing varies among mammalian species. In cattle, the hypoblast specifies in day 8 blastocysts, and differentiates into yolk sac during implantation around days 18–23. The involution of yolk sac occurs 40 days postfertilization, which accompanies the formation of the placenta.4–6 Particularly, hypoblast undergoes dynamic lineage development, which is coordinate with a period of rapid growth and elongation of embryo from spheroid form at days 9–11, to elongated form at days 12–14 to a filamentous form at day 16 until implantation,7 when the majority of pregnancy loss occurs.8–10 Proper hypoblast development and function are pivotal for the success of pregnancy; however, our knowledge of hypoblast development, particularly in ruminant species, is limited due to technical and logistic difficulties associated with in vivo experiments and a lack of manipulatable cell culture models. Furthermore, whether and how extraembryonic tissues support the development of pre-implantation epiblast remain largely unknown.

Extraembryonic endoderm stem cells (XENs) are established from the primitive endoderm of early embryos and represent valuable tools for studying hypoblast lineage differentiation and function during embryogenesis.11,12 To date, XENs have been established in multiple species including mice,12,13 pigs,14,15 monkeys,16 and humans.17 Notably, signaling pathways inducing XENs vary extensively among different mammals. Mouse XENs can be captured from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) via retinoic acid and Activin-A,18 while human induced hypoblasts have been converted from naive pluripotent stem cells independent of FGF signaling19 or a chemical cocktail (BMPs, IL-6, FGF4, A83–01, XAV939, PDGF-AA, and retinoic acid).20 In domestic livestock, porcine XENs have been derived from blastocysts using either LIF/FGF2 or LCDM (LIF, CHIR99021, (S)-(+)-dimethindene maleate, and minocycline hydrochloride) condition.14,15 Attempts to establish bovine XENs (bXENs) from blastocysts have identified FGF2 as a facilitator, but the resultant cells could not be maintained in long-term culture with limited characterization.21,22 Thus far, stable bXENs have not been established yet.

In this study, we discovered that a modified chemical cocktail (FGF4, BMP4, IL-6, XAV939, and A83–01) supports de novo derivation and long-term culture of bXENs from blastocysts. We then attempted to use bXENs to model epiblast and hypoblast lineage crosstalk and found that bXENs promote growth and stemness of bovine expanded EPSCs. We further observed that, in the present of the chemical cocktail sustaining bXENs, the growth and progression of epiblasts are facilitated in the developing pre-implantation embryos. Finally, by assembling bXENs with bovine EPSCs (bEPSCs)23 and trophoblast stem cells (bTSCs),24 we developed an improved bovine blastoid protocol and demonstrated that the bovine blastoids assembled from bEPSCs, bTSCs, and bXENs (EPTX-blastoids) more resembles blastocysts compared with those created from bEPSCs and bTSCs (EPT-blastoids),25 in terms of lineage composition, allocation, and transcriptional features.

RESULTS

De novo derivation of bXENs from blastocysts

We have previously shown that a combination of four molecules (FGF2, Activin-A, LIF, and Chir99021) is able to efficiently convert SOX2+ bEPSCs into SOX17+ hypoblast cells.25 Therefore, we first attempted to derive bXENs from day 8 hatched IVF blastocysts using these four factors (4F-XENM). We observed the outgrowths of XEN-like colonies (Figure S1A). Since robust hypoblast markers remain largely unknown in bovine cells, by mining a single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) dataset of bovine day 12 embryo7 we identified a group of genes (CTSV, FETUB, APOA1, APOE, COL4A1, and FN1) that are highly expressed specific to hypoblast lineages, and are regarded as hypoblast markers (Figures S1B and S1C). We found that these bXEN-like cells highly express all identified hypoblast markers, while barely express epiblast (SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG) or trophoblast (CDX2, GATA3, and GATA2) markers (Figure S1D). However, these XENs can only be maintained up to 10 passages, therefore, named as short-term passaged bXENs.

Recently, authentic human hypoblast cells were successfully induced from naive pluripotent stem cells with seven chemical molecules, including BMPs (a pSMAD1/5/9 activator), IL-6 (a pSTAT3 activator), FGF4, A83–01 (a pSMAD2 inhibitor and ALK4/5/7 inhibitor), and XAV939 (a WNT/β-catenin inhibitor and tankyrase inhibitor) along with PDGF-AA and retinoic acid.20 To establish long-term culture of bXENs, we assessed different combinations of these seven factors with 4F-XENM. Our screening showed that neither seven factors nor adding individual or any combinations of seven factors into 4F-XENM medium could establish stable bXENs (Table S1). Surprisingly, we found that a combination of FGF4, BMP4, IL-6, XAV939, and A83–01 (5F-XENM) enables efficient support of the outgrowth of bXEN-like morphological colonies from blastocysts (Figure 1A). The derived bXEN-like colonies maintained stable and self-renewal properties with long-term passages (>30) (Figure 1A), therefore named as long-term passaged bXENs, or bXENs. Further characterization revealed that bXENs maintain stable epithelial morphology of flattened colonies with clearly defined margins (Figure 1A) and a normal diploid number of chromosomes (2N = 60) after long-term in vitro culture (Figure 1B). Immunostaining analysis showed that, similar to hypoblasts of bovine blastocysts, bXENs express SOX17 and GATA6, but neither SOX2 nor CDX2, which is positive in bEPSCs or bTSCs, respectively (Figures 1C and 1D). They also highly expressed all identified novel hypoblast markers (Figure 1E). To distinguish the established XEN cells from definitive endoderm, we analyzed extraembryonic and definitive endoderm markers and found that bXENs highly express extraembryonic markers such as PDGFRA, GATA4, and SOX17, while barely expressing definitive endoderm markers, such as CXCR4 and KIT (Figure S2A).

Figure 1. Derivation and characterization of bXENs.

(A) Representative bright-field image of the outgrowth from day 8 bovine blastocyst contains three morphologically distinct cell types and subsequent derivation and maintenance of bXENs over 30 passages.

(B) Karyotype analysis of bXENs at passage 15.

(C) Immunofluorescence analysis of GATA6 and SOX17 (hypoblast markers), SOX2 (epiblast marker), as well as CDX2 (trophectoderm marker) in day 8 blastocysts. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Immunofluorescence analysis of GATA6, SOX17, SOX2, as well as CDX2 in bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs, separately. Scale bar, 25 μm.

(E) Relative expression of defined lineage marker genes in three stem cell lines.

(F) The small molecules included in each medium recipe (R1-R6).

(G) Relative expression level of hypoblast marker genes in bXENs cultured in different mediums from (F).

(H) Cell number estimated within 3 days following passage.

(I) Morphology of bXENs cultured in XENM with or without A83–01. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Furthermore, we determined the essential small molecules that are required for the maintenance of bXENs. First, A83–01 alone could maintain the stable expansion of bXENs, while the cell proliferation and the marker gene expression were reduced (Figures 1F, 1G, and 1H). Withdrawal of A83–01 from 5F-XENM, bXENs exhibited differentiation and failed to expand into stable cell lines (Figure 1I), suggesting that A83–01 is indispensable in maintaining bXENs. Second, we observed that withdrawal of XAV939 or XAV939 together with IL-6 has a limited impact on the expression of bXEN marker genes (Figure 1G) and cell proliferation (Figure 1H). Third, absence of XAV939 and BMP4 resulted in reduced expression level of hypoblast markers such as FETUB, APOE, and FN1 (Figure 1G). Finally, we showed that BMP4 and FGF4 are two major factors affecting bXEN proliferation (Figure 1H).

Collectively, we developed a culture condition (5F-XENM) that is effective in supporting de novo derivation and maintenance of bXENs.

Transcriptional and chromatin accessibility features of bXENs

We next explored the transcriptomes of bXENs by RNA-seq analysis. We compared the transcriptomes of bXENs with bEPSCs23 and bTSCs.24 Principal-component analysis (PCA) revealed that bXENs are clustered distinct from bEPSCs in PC1 and bTSCs in PC2, respectively (Figure 2A), indicating the unique identity of three types of bovine stem cells, which is also shown in the correlation analysis (Figure S2B). The identity of bXENs was further confirmed by the expression of representative marker genes of their corresponding blastocyst lineages (PrE, Epi, and TE) in these three types of bovine stem cells (Figure 2B). Of note, bXENs also highly expressed both extraembryonic visceral endoderm (VE) and parietal endoderm (PE) markers (Figure 2B), suggesting their developmental capacity toward VE and PE of the yolk sac. Additionally, we identified signaling pathways that are uniquely enriched in bXENs, including PI3K-Akt, cholesterol metabolism, focal adhesion, TNF, and TGF-β signaling pathways (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, when integrating transcriptomes of bXENs with single-cell transcriptomes of hypoblast lineages of bovine embryos at day 12, 14, 16, and 18,7 we found that bXENs are closely clustered with highly proliferating hypoblasts from spheroid embryos (day 12 and day 14) while distinct from more differentiated hypoblasts of elongated embryos (day 16 and day 18), suggesting that bXENs resemble early hypoblast populations in vivo (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Transcriptomic and chromatin-accessible features of bXENs.

(A) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of transcriptomes of bXEN, bEPSCemb, bEPSCiPS, and bTSC.

(B) Heatmap showing the marker gene expression for PrE, VE, PE, Epi, and TE from each bovine stem cell type.

(C) Heatmap (left panel) showing lineage-specific expressed genes for bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs, as well as the enriched signaling pathways (right panel).

(D) PCA of transcriptomes of bXENs and three major lineages from days 12 to 18 in vivo bovine embryos.

(E) PCA of transcriptomes of XEN and ESC from bovine, mouse, and human. Datasets of bEPSCemb and bEPSCiPS are from Zhao et al., PNAS 202123; datasets of hNESCH1, hNESCH9, hNESCiPS, hPESC, hXEN7F, and hXENGATA6OE are from Okubo et al., Nature 202420; datasets of mESC, mpXEN and mXEN are from Zhong et al., Stem Cell Research 2018.26

(F) Venn diagram (top panel) showing the number of XEN-enriched genes when compared with ESC among three mammalian species, as well as the enriched GO/KEGG (bottom panel) categories from overlapped genes and bovine-specific genes, respectively.

(G) The enrichment of ATAC-seq peaks at annotated promoters (TSS ± 2 kb) (normalized and on average) in bXENs.

(H) Feature distribution of ATAC-seq peaks in bXENs.

(I) The genome browser views showing the ATAC-seq peaks and RNA-seq reads enrichment near APOE and SOX17 in bXENs.

(J) Motif enrichment analysis of ATAC-seq peaks from bXENs.

Additional transcriptomic comparisons of XENs and ESCs among cattle,23 humans,20 and mice26 further confirmed the lineage identity of bXENs (Figure 2E). To investigate the unique transcriptomic features of bXENs, we explored XEN-specific genes compared with ESCs in 3 mammalian species separately and identified 400 genes that are commonly enriched in XENs (Figure S2C). These genes were involved in regulating canonical hypoblast functions, including circulatory system development, cell fate commitment, and embryo development (Figure 2F). Additionally, 274 genes are uniquely in the bovine, mainly involved in manipulating ligand-receptor interaction, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, and steroid hormone biosynthesis (Figure 2F). It is also noteworthy that bovine and human XENs share more common genes than those in comparison with mouse.

We also conducted ATAC-seq analysis to characterize the genome-wide chromatin accessibility of bXENs (Figures 2G and 2H). Our analysis showed that the chromatin accessibilities of hypoblast lineage marker genes are consistent with their expression profiles (e.g., APOE and SOX17) (Figure 2I). We confirmed that canonical hypoblast transcriptional factor (TF) binding motifs are enriched in bXENs, such as GATA6, GATA4, and SOX17 (Figure 2J). In addition, we identified several novel bovine hypoblast TFs including CTCF, BATF, ATF3, FOSL2, KLF5, KLF3, ELF1, JUND, NFY, and HLF (Figure 2J). We further confirmed that their chromatin accessibilities are consistent with their gene expression as well (Figure S2D). Most of them (CTCF, NFYA, NFYC, and JUND) were also highly expressed in the hypoblast cells of a day 12 bovine embryo (Figure S2E). Additionally, we analyzed the definitive endoderm markers against bXEN transcriptional and chromatin accessibility datasets and found that these markers are not active in bXENs (Figures S2F and S2G), further reinforcing their distinct identity from definitive endoderm.

Together, the RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analyses confirmed the molecular identity of bXENs and shed light on the molecular features during the earliest steps of hypoblast development in bovine.

bXENs regulate the development of EPSCs and pre-implantation epiblasts

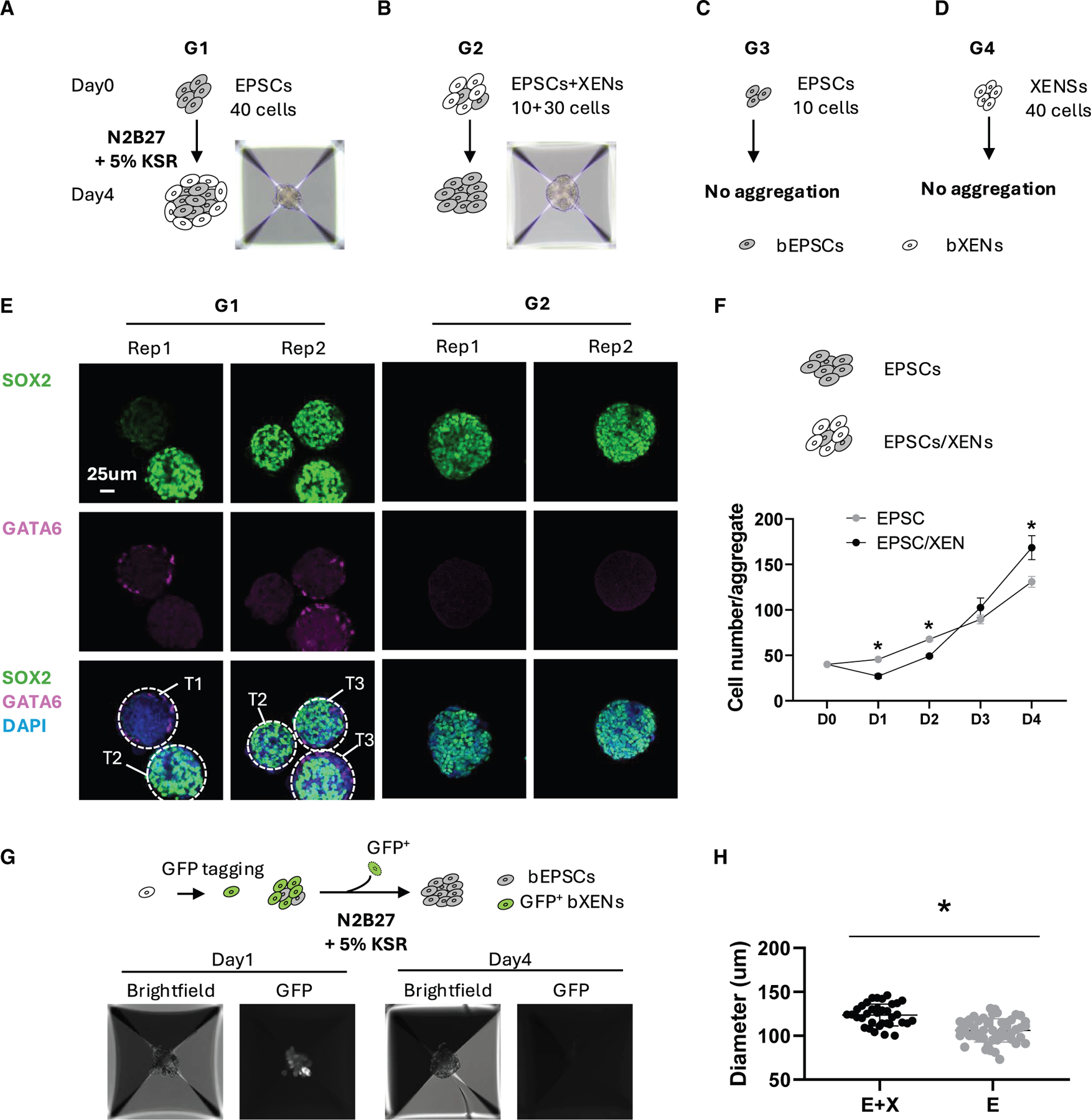

In cattle, the attachment of blastocysts is preceded by a period of rapid growth and elongation, when hypoblast lineages present dynamic changes between spheroid (day 12 and day 14) and elongated (day 16 and day 18) embryos, and have intense communication with both epiblast and TE lineages.7,27 Given that both epiblast and hypoblast specify from ICM and the plasticity of two lineages are largely unknown, here we implemented a 3D co-culture model with bXENs and bEPSCs to examine whether or how hypoblast regulates the development of epiblast during bovine embryogenesis. We mixed different ratio of bEPSC:bXEN cell populations (group 1 [G1]: bEPSCs/bXENs = 40/0; group 2 [G2]: bEPSCs/bXENs = 10/30; group 3 [G3]: bEPSCs/bXENs = 10/0; and group 4 [G4]: bEPSCs/bXENs = 0/40) (Figures 3A–3D). We found that co-cultures in both G1 and G2 can form spherical structures, but not those from G3 and G4 (Figures 3A–3D). Next, we conducted immunofluorescence analysis of SOX2 and GATA6 that are exclusively expressed in bEPSCs and bXENs, respectively. We found that spherical structures organized from bEPSCs alone in G1 largely remain SOX2 positive with GATA6-positive cells located at the peripheral region (Figure 3E). Further quantification showed that aggregates in G1 consist of three types of structures, including T1, SOX2– GATA6+; T2, SOX2+ GATA6–; T3, SOX2+ GATA6+ (Figure 3E). These results indicate a loss of pluripotency and random differentiation of EPSCs to hypoblasts-like cells consistent with previous observations both in humans20,28 and bovines.25 On the contrary, co-culture of bEPSCs with bXENs in G2 resulted in spherical structures with cleaner and smoother periphery region compared with those of G1 (Figures 3E and 3F), suggesting an improved proliferation and survival of aggregates. Further immunostaining analysis showed that all cells in G2 remain SOX2 positive without any detection of GATA6+ cells (Figure 3E), suggesting that the presence of bXENs prevents differentiation of bEPSCs. To rule out the possibility that XENs transdifferentiate into SOX2+ cells, we tagged bXENs with GFP, followed by co-culture. We observed that bXENs are aggregated with bEPSCs on day 1, and all GFP+ bXENs disappear by day 4 (Figure 3G). Additionally, we found that, in the presence of bXENs in G2, bEPSC proliferation is significantly facilitated over those of G1 based on the size of the formed spherical structures (Figure 3H). These results demonstrated that the presence of bXENs and associated communications support the growth and stemness of bEPSCs.

Figure 3. 3D co-culture of bEPSCs and bXENs.

(A–D) Aggregates formed by 40 bEPSC cells (A), a mixture of bEPSCs and bXENs (B), 10 bEPSC cells (C), and 40 bXEN cells (D) cultured in N2B27 medium with 5% KSR.

(E) Immunofluorescence analysis of cell aggregates formed by bEPSCs (G1) or mixture of bEPSCs and bXENs (G2). Green, SOX2; pink, GATA6; blue, DAPI.

(F) Assay to show the proliferative ability of cell aggregates by 40 EPSCs or a combination of 10 EPSCs and 30 XENs from day 0 to day 4.

(G) Aggregates generated by the mixture of 10 bEPSCs and 30 GFP tagged bXENs on day 1 and day 4, respectively.

(H) Diameters of aggregates formed by the mixture of bEPSCs and bXENs (E + X) or by the bEPSCs alone. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 from unpaired t test.

We next evaluated the effects of the molecule cocktail sustaining bXENs on the development of pre-implantation embryos. We treated bovine in vitro cultured embryos with the molecular cocktail sustaining bXENs (BMP4, FGF4, A83–01, XAV939, and IL-6). The experimental treatment was given at different developmental periods—before and after major genome activation or hypoblast specification (exp. 1, days 1–8; exp. 2, days 5–8; exp. 3, days 8–12) (Figure 4A). The subsequent developmental rate and lineage composition and allocation were measured by immunostaining analysis of epiblast marker SOX2, hypoblast marker SOX17, and TE marker CDX2. When treating embryos with the bXEN molecule cocktail from either days 1–8 (exp. 1) or days 5–8 (exp. 2), we found day 8-hatched blastocysts have a significantly increased SOX2+/SOX17+ cell ratio compared with the control group (Figures 4B and 4C). We also noticed that this bXEN molecule cocktail have no impact on early cleavage and trophoblast differentiation until blastocyst (Figure 4D). However, the blastocyst hatching rate decreased dramatically presumably due to the issue of lineage specification within ICM (Figure 4D). Further treating blastocysts with bXEN molecule cocktail during extended culture period from day 8 (exp. 3), we observed that day 12 embryos have a well-defined and condensed SOX2+ spot in the ICM region (Figure 4E), consistent with in vivo day 12 embryos (Figure S3), while ICM structures go through degeneration in the control group (Figure 4E). When calculating the ratio of SOX2+ and SOX17+ cells, we observed significantly higher SOX2+ cells and lower SOX17+ cells in the treated group compared with the control. These results demonstrated that bXEN molecule cocktail could effectively protect epiblasts from differentiation or degeneration during bovine pre-implantation development.

Figure 4. bXENs regulate the development of pre-implantation epiblasts.

(A) Schematic summarizing the experimental treatments. The treatment was given at different developmental period before and after major genome activation or hypoblast specification (exp. 1, days 1–8; exp. 2, days 5–8; exp. 3, days 8–12).

(B) Immunofluorescence analysis of SOX17 (hypoblast marker), SOX2 (epiblast marker), and CDX2 (trophectoderm) in day 8 blastocysts under the treatment in exp.1 and exp. 2. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(C) Ratio of SOX17+ and SOX2+ cells in embryos from exp. 1–3.

(D) Developmental rates of embryos under control or treatments.

(E) Immunofluorescence analysis of SOX17, SOX2, and CDX2 in day 12 embryos under the treatment in exp. 3. Scale bar, 25 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 from unpaired t test.

Taking together, our experiments with both co-culture cell model and IVF embryos provide evidence that XENs or their molecule signaling regulate the development of EPSCs or pre-implantation epiblasts in bovine, respectively.

Generation of bovine blastoids by self-organization of bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs

We have previously reported the successful generation of bovine blastoids by self-assembly of bEPSCs and bTSCs (EPT-blastoids) in tFACL+PD culture conditions.25 However, the blastoids generated by this approach have exhibited lower proportion of hypoblast lineage compared with IVF blastocysts, which may limit their developmental capacity. The establishment of bXENs prompted us to develop an improved bovine blastoid protocol through 3D assembly of bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs. We first aggregated three bovine stem cell types (bEPSC/bXEN/bTSC = 8:8:16) using the culture condition (FGF2, Activin-A, Chir99021, Lif, and PD0325901) as we previously reported.25 We found that this condition can support the formation of blastoids with high efficiency (46.60% ± 3.80%) within 4 days. The resulting blastoids contain a blastocele-like cavity, an outer TE-like layer, and an ICM-like compartment, morphologically equivalent to day 8 blastocysts (Figures 5A–5D and 5E). However, these blastoids lack SOX17+ hypoblasts compared with day 8 IVF blastocysts (Figures 5A and 5D), similar to what we observed in EPT-blastoids (Figure 5C).25

Figure 5. Generation of bovine blastoids by self-organization of bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs.

(A–D) Top panel: illustration of the bovine blastoid formation using different assembly approach. (A) EPTX-blastoids—bEPSC, bTSC, and bXEN aggregation in FACLP medium. (B) EPTX-blastoids—bEPSC, bTSC, and bXEN aggregation in ACL medium. (C) EPT-blastoids—bEPSC and bTSC aggregation in FACLP medium as our previous published. (D) IVF blastocysts control). Bottom panel: phase-contrast and immunofluorescence analysis of blastoids from distinct protocols and blastocysts, as well as the quantification of lineage composition in blastoids and blastocysts. Green, SOX17; blue, SOX2; red, CDX2.

(E) Blastoid formation rate from distinct protocols.

(F) Blastocele diameter measurement of blastoids from distinct protocols and blastocysts.

(G) Inner cell mass (ICM)/embryo ratio measurement of blastoids from distinct protocols and blastocysts.

(H) Joint uniform manifold approximation and projection embedding of 10X Genomics single-nucleus transcriptomes of bovine EPTX-blastoids (green) and bovine day 8 blastocysts (blue).

(I) Major cluster classification based on marker expression.

(J) Dot plot indicating the expression of markers of epiblast, trophectoderm, and hypoblast.

(K) Percentage of three cell types in blastoid and blastocyst. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

It has been shown that FGF2 could bias the cell fate of ICM toward PrE.25,29,30 As we integrated XENs, the FGF2 is not necessary for the blastoid induction anymore. Also, MEK inhibitor PD0325901 inhibits hypoblast specification from ICM,29,31 which might be the reason for the vanished hypoblasts. Therefore, we withdrew both FGF2 and PD0325901 from the culture conditions, and found that the modified medium, ACL (Activin-A, Chir99021, Lif) supported the idea that the formed blastoids morphologically resemble day 8 IVF blastocysts (Figure 5B). The efficiency of blastoid formation from three bovine stem cell types - bEPSCs, bTSCs, and bXENs (EPTX-blastoid) reached 40.84% ± 4.76% within 4 days. Importantly, EPTX-blastoids had a similar proportion of hypoblast and a slightly higher ratio of epiblast population compared with day 8 blastocysts, with the majority of hypoblast cells surrounding epiblasts (Figures 5B and 5D). Additionally, the blastocele size and ICM/blastocele ratio of EPTX-blastoids were also equivalent to day 8 IVF blastocysts (Figures 5F and 5G). Thus, the bovine EPTX-blastoid model established here more closely resembles blastocysts compared with the EPT-blastoids.25

To determine the transcriptional states of EPTX-blastoids, we performed single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) analysis of EPTX-blastoids using the 10X Genomics low-throughput (up to 1,000 cells) platform. To ensure precise comparison, we also generated snRNA-seq datasets of bovine day 8 IVF blastocysts using the same 10X Genomics platform. Joint uniform manifold approximation and projection analysis revealed overall that cells from the EPTX-blastoid cluster well with blastocyst-derived cells (Figure 5H). We annotated three major cell clusters from blastocysts representing three blastocyst lineages, including: cluster 1, highly expressed SOX2, VIM, SLIT2, NNAT, CDH2, and NANOG as epiblasts; cluster 2, highly expressed GATA6, HDAC1, HDAC8, HNF4A, PDGFRA, and RUNX1 as hypoblasts; and cluster 3, highly expressed DAB2, GATA2/3, KRT8, SFN, TEAD4, and TFAP2C as TE cells (Figures 5I and 5J). Of note, in the blastocyst, the defined epiblast cells still expressed hypoblast markers, and vice versa (Figure 5J), suggesting that the segregation of epiblast and hypoblast within ICM has not completed yet.32 The marker gene expression had the same patterns in all three annotated lineages from both EPTX-blastoids and blastocysts, such as GATA2 (TE markers), PDGFRA (HYPO markers), and SLIT2 (EPI markers), indicating that EPTX-blastoids transcriptionally resemble blastocysts (Figure S4A). The comparative clustering analysis of EPTX-blastoids and blastocyst cells showed that EPTX-blastoids have a lower hypoblast cell population and higher epiblast population compared with the blastocysts (Figure 5K). This confounding factor in single-cell gene expression analysis may constitute the difference of lineage composition from immunostaining analysis. Additionally, we performed GO analysis of genes specifically enriched in each of three lineages of EPTX-blastoids. We found that genes specific to epiblasts are involved in regulating nervous system development, cell junction organization, and stem cell population maintenance; genes upregulated in hypoblasts regulate cell morphogenesis and cell fate commitment; and, finally, genes highly expressed in TE cells are involved in manipulating the lipid biosynthetic process, actin cytoskeleton organization, and cell migration (Figure S4B). Intriguingly, it was shown that most of the lineage-specific genes in epiblast and hypoblast lineages are TFs or TF cofactors, unveiling the lineage-specific functions of those critical TFs during lineage specification within ICM and further differentiation events (Figure S4B).

Together, we developed an efficient and robust protocol to generate bovine EPTX-blastoids that more closely resemble blastocysts than EPT-blastoids25 in terms of lineage composition, allocation, and transcriptional features.

DISCUSSION

The hypoblast and its derivatives play a vital role in supporting and patterning the embryo33; however, owing to applicable approaches associated with in vivo experiments, knowledge of hypoblast lineage segregation and development remains largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated that a chemical cocktail (FGF4, BMP4, IL-6, XAV939, and A83–01) enables de novo derivation and maintenance of stable bXENs from IVF blastocysts. Hypoblast lineage segregation and development is a conserved progress, while signaling to specify and sustain the hypoblast is divergent among mammalian species. In mice, XENs do not require FGF signaling and can be maintained in the presence of retinoic acid and Activin-A.18 In humans, hypoblast induction requires FGF signaling19 and can be induced from naive pluripotent stem cells using a chemical cocktail (BMPs, IL-6, FGF4, A83–01, XAV939, PDGF-AA, and retinoic acid).20 In domestic livestock, porcine XENs can be derived from blastocysts using either LIF/FGF2 or LCDM (LIF, CHIR99021, (S)-(+)-dimethindene maleate, and minocycline hydrochloride).14,15 Of note, LCDM is reported to maintain both bovine iPSCs34 and TSCs.24 Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated that FGF2 is a key factor maintaining bovine primitive endoderm cells.6,22 In the presence of FGF2, bEPSCs could also efficiently convert hypoblast-like cells.25 In this study, we show that bXEN cells can be induced in the presence of FGF2; however, they are only capable of short-term self-renewal. Instead, a modification of human hypoblast induction conditions by removing retinoic acid supports long-term culture of bXENs. The bXENs established in this study fill a gap and add a reliable stem cell model for understanding embryogenesis of an ungulate species.

Furthermore, we have demonstrated the role of bXENs or bXEN molecule cocktail in regulating EPSCs or pre-implantation epiblast development, respectively. Our observation that the bXEN molecule cocktail promotes epiblast development is particularly interesting. Although the underling molecular mechanism remains unknown, combining the evidence that bXENs promote the growth and stemness of EPSCs, an in vitro counterpart of epiblasts, we speculate that the role of this XEN molecule cocktail in promoting epiblast development can be attributed to either a direct impact of their targeted signaling pathways on epiblast development, or an indirect cascade ex vivo, where the bXEN molecule cocktail targeted hypoblast signaling promoting epiblast development through cell-cell communication. Additionally, the lineage plasticity that is demonstrated in both human35 and mouse36 maybe also be attributed to this, but remains largely uncharacterized within bovine embryos. Together, our findings indicate the role of the hypoblast in regulating epiblast development in a ruminant species. This has also been most recently highlighted in both mouse and humans using in vitro experimental models.20,28,36 In humans, the existence of hypoblasts can facilitate ESCs in generating a pro-amniotic-like cavity, which recapitulates the anterior-posterior pattern and mimics several aspects of the post-implantation embryo.20,28 In mouse, primitive endoderm stem cells support the lineage plasticity and the PrE alone is sufficient to regenerate a complete blastocyst and continue post-implantation development. Unlike many other mammalian species, ruminant species undergo a unique conceptus elongation process before implantation. During this phase, dramatic proliferation and differentiation of trophoblast and hypoblast lineages occurs, while the germ layer differentiation from epiblasts is only observed until day 16,7 which may constitute limited developmental potential of bXENs compared with humans and mouse. Thus, the bXEN model established here mirrors the physiological lineage interaction between hypoblast and epiblast during bovine conceptus elongation.

A final contribution of this study is the development of an improved blastoid protocol by self-organization of bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs. In our previous study, bovine EPT-blastoids assembled from bEPSCs and bTSCs have a lower proportion of hypoblast lineages compared with the IVF blastocysts,25 which may compromise their developmental potential. Instead, with the integration of bXENs, we have shown that EPTX-blastoids established here more closely resemble bovine blastocysts compared with the first generation of bovine blastoids (EPT-blastoids) in terms of morphology, lineage composition and allocation, and transcriptional features. So far, most of the established blastoid models from other species, especially human, are self-organized from naive ESCs or EPSCs,37–39 which raises concern that the differentiated TE-like lineage transcriptionally resembles amniotic ectoderm.40 By utilizing the assembly approach with authentic TSCs could eliminate this concern. Strikingly, embryo-like structures have been generated through assembling mouse ESCs, TSCs, and XENs in vitro, which recapitulate the developmental characteristics of mouse embryos up to day 8.5,41,42 demonstrating that blastoids derived by an assembling approach with three lineages possess higher developmental potential. This is significant in large mammals, particularly for domestic livestock, as blastoid technology established here, upon further optimization and in vivo function testing, could lead to the development of novel artificial reproductive technologies for cattle breeding.

In summary, our work establishes authentic bXENs and developed an improved bovine blastoid technology. We have also shown the valuable of bXENs in modeling cell-cell communications, thus filling a significant knowledge gap in the study of bovine embryogenesis when most pregnancy failure occurs.

Limitations of the study

We thoroughly characterized the established bXENs with regard to their cellular, molecular, and functionality properties. However, the contribution capacity of bXENs to chimeras in vivo remains unexplored in this study due to the significant challenges in conducting such experiments in large mammals such as cattle. Also, hypoblast lineage development and the marker genes for characterization in ruminant species remain largely unknown, which limits characterization of bXEN in vivo differentiation. Furthermore, although we have demonstrated the role of bXENs and the bXEN molecule cocktail in regulating bEPSCs and bovine pre-implantation epiblast development, respectively, the underling molecular mechanisms how hypoblast and epiblast lineages interact to ensure proper embryo development remain largely unknown. bXENs established here represent a valuable tool to study peri-implantation lineage crosstalk. Finally, despite the fact that the newly developed EPTX-blastoids more closely resemble blastocysts in terms of morphology and transcriptome compared with EPT-blastoids,25 the assessment of the developmental potential of bovine blastoids warrants future studies.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Zongliang Jiang (z.jiang1@ufl.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The raw FASTQ files and normalized read accounts per gene are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession numbers GSE283042 and GSE283048. This paper analyzes publicly available data. The accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

STAR★METHODS

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Animal care and use

Bovine peri-implantation embryos were collected from non-lactating, 3-year-old crossbreed (Bos taurus x Bos indicus) cows housed at the University of Florida Beef Teaching Unit. The experiments were conducted under animal use protocol (202300000191) approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Florida. All cows were housed in open pasture, and under constant care of the farm staff.

All the cells (EPSCs, TSCs, and XENs) used in this study were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

METHOD DETAILS

Bovine IVF embryo production

The IVF embryos used in this study were produced as previously described.53 Briefly, bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from selected follicles of slaughterhouse ovaries. BO-IVM medium (IVF Bioscience) was used for oocyte in vitro maturation. IVF was performed using cryopreserved semen from a Holstein bull with proven fertility. Embryos were then washed and cultured in BO-IVC medium (IVF Bioscience) at 38.5°C with 6% CO2. Day 8 hatched blastocysts were collected and were processed for bXENs derivation. For post-hatching culture from day 8 until day 12, embryos were transferred into extended culture medium containing DMEM: F12 (Gibco) and Neurobasal medium (Gibco) (1:1), 1x N2-supplement (Gibco), 1x B27-supplement (Gibco), 1x NEAA (Gibco), 1x GlutaMAX (Gibco), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 10 μM/mL ROCK inhibitor (Tocris, 1254), 20 ng/mL ActivinA (Pe-protech, 100–18B). For the treatment group, 25 ng/mL FGF4 (sigma, F8424), 10 ng/mL BMP4 (R&D SYSTEMS, 314-BP-050/CF), 1μM XAV939 (sigma, X3004–5MG), 3μM A83–01 (sigma SML0788–25MG), 10 ng/mL IL-6 (sigma, SRP3096) were added.

Bovine in vivo embryo collection

Cows were synchronized as we previously described.7 Bovine peri-implantation embryos were collected 12 days after artificial insemination. Embryos were recovered by standard non-surgical flush.

Derivation and culture of bXENs

ICMs were isolated from day 8 blastocysts by microsurgery and were placed in separate wells of a 24-well plate that was seeded with mitomycin C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells. To derive bXENS, the ICMs were initially cultured in pre-bXENMS containing DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 1x N2-supplement, 1x B27-supplement, 1x NEAA, 1x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20 ng/mL bFGF (Peprotech, 100–18B), 20 ng/mL ActivinA. After three days, when all the ICMs attach and form outgrowth, change the medium to bXENMS containing DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 0.5x N2-supplement, 0.5x B27-supplement, 0.5x NEAA, 0.5x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1mM NaPy (Sigma, s8636), 10 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid (Sigma, A92902), 1x ITS-X (Gibco, 51500–056), 0.1% FBS, 0.5% KSR, 20 ng/mL LIF (Peprotech, 300–05), 1 μM Chir99021 (Sigma, SML-1046), 10 ng/mL bFGF, 10 ng/mL ActivinA.

To derive bXEN, the ICMs were cultured in 5F-XENM containing DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 1x N2-supplement, 1x B27-supplement, 1x NEAA, 1x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 25 ng/mL FGF4, 10 ng/mL BMP4, 1 μM XAV939, 3 μM A83–01, 10 ng/mL IL-6. To promote the proliferation of hypoblast, 0.1% KSR, 0.1% BSA (MP biomedicals), 20 ng/mL ActivinA, and 10 ng/mL PDGF (R&D SYSTEMS, BT220–010/CF) were also added during the derivation of bXEN and were optional for bXENs maintenance. All the cells were cultured at 38.5°C and 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every other day. On day 7 or 8, outgrowths were dissociated by TrypLE (Gibco, 12605–010) for 5–7 min at 38.5°C and passaged. For optimal survival rate, 10 μM Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 was added to the culture medium during first 24 h. Once established, both bXENS and bXEN were passaged every 3–5 days at a 1:5 split ratio using TrypLE. Each well of cells was dissociated by 0.5 mL TrypLE for 5 min at 38.5°C, the same volume of DMEM/F12 with 1% BSA was used to neutralize. bXENs could be cryopreserved by CELLBANKER 2 (ZENOGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bovine EPSCs culture

Bovine EPSCs were maintained in bEPSC culture medium (3i+LAF)23: mTeSR base (STEMCELL, 85850), 1% BSA,10 ng/ml LIF, 20 ng/ml Activin A, 0.3 μM WH-4–023, 1 μM Chir99021, 5 μM IWRI, 50 μg/mL Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C). bEPSCs were passaged every 2 days at a 1:6 split ratio using TrypLE. Each well of cells was dissociated by 0.5 mL TrypLE for 5 min at 38.5°C, the same volume of bXEN medium was used to neutralize TrypLE, ROCK inhibitor is necessary for each passage. bEPSCs could be cryopreserved by CELLBANKER 2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bovine TSCs culture

Bovine TSCs were derived and cultured in LCDM24 (hLIF, CHIR99021, DiM and MiH) media (DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 0.5x N2-supplement, 0.5x B27-supplement, 1x NEAA, 1x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% BSA (MP biomedicals), 10 ng/mL LIF, 3 μM CHIR99021, 2 μM Dimethinedene maleate (DiM) (Tocris, 1425) and 2 μM Minocycline hydrochloride (MiH) (Santa cruz, sc-203339). bTSCs were passaged every 4 days at a 1:4 split ratio using Accutase (Gibco, A1110501). Each well of bTSCs was dissociated by 1mL Accutase for 5 min at 38.5°C, the same volume of bTSCs medium was used to dilute Accutase for neutralizing the reaction. bTSCs were cryopreserved by CELLBANKER 1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of GFP-tagged bXENs

The pLenti CMV GFP Puro plasmid (Addgene #17448) was packaged into lentivirus in 293T cells using JetPrime reagent (Polyplus, 101000015) following manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h incubation, the medium was collected and concentrated using the Lenti-X Concentrator (Takara, 631231). Then the GFP-lentiviruses were transfected into bXENs with 5 μg/ml polybrene (sigma, TR-1003-G). 1 μg/mL of puromycin (sigma, P8833) was added to the culture medium 2–3 days after transfection. Drug-resistant colonies with GFP signaling were manually picked and further expanded.

Blastoid formation

For EPTX-blastoid formation, bEPSCs, bTSCs, and bXENs were dissociated into single cells by treating with TrypLE for 3 min, 7 min, and 15 min, respectively, followed by neutralizing with the same volume of their culture medium. After centrifugation at 300 x g for 5 min, cells were resuspended in their normal culture media with ROCK inhibitor. Single-cell dissociation was made by gentle but constant pipetting until no visible cell clumps exist. To deplete iMEF cells, cells of three cell lines were filtered through passing 40mm cell strainers (Corning) separately and placed in precoated 6 well plates (Corning) with 0.1% gelatin and incubated for 35 min at 38.5°C. Cells were then collected and stained with 1x trypan blue and manually counted in a Neubauer chamber. Current protocol is optimized for 8 bEPSCs, 8 bXENs and 16 bTSCs per well in a 1200 well Aggrewell 400 microwell culture plate (Stemcell technologies) for 9,600, 9,600, and 19,200 of each cell type per well. Each well was precoated with 500 mL of Anti-Adherence Rinsing Solution (Stemcell technologies) and spun for 5 min at 1500 x g. Wells were rinsed with 1 mL of PBS just before aggregation. The cells for one well were mixed and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min, followed by resuspension with 1 mL ACL medium (DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 1x N2-supplement, 1x B27-supplement, 1x NEAA, 1x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5x ITS-X, 20 ng/mL LIF, 10 ng/mL ActivinA, 1 μM Chir99021, supplemented with 1x CEPT cocktail54 (50 nM chroman-1 (C, Tocris), 5 μM emricasan (E, Selleckchem), 0.7 μM trans-ISRIB (T, Tocris), and 1 x polyamine supplement (P, Thermo)). To ensure even distribution of the cells within each microwell, cells were gently mixed by pipetting with a P200 pipette. The plate was first placed in incubator for 8 min to allow the cells to settle down, then centrifuged at 700 x g for 3 min and put back to incubator. Half of the medium was changed daily, the blastoids showed up from day 2 and could be collected on day 3 or day 4.

Bovine EPSCs and XENs co-culture

bEPSCs and bXENs were dissociated into single cells and depleted feeder cells as described above. A combination of bEPSCs and/or bXENs (Treatment 1: 10 bEPSCs and 30 bXENs; Treatment 2: 40 bEPSCs; Treatment 3: 10 bEPSCs; Treatment 4: 40 bXENs) were seeded in each well of a 1200 well Aggrewell 400 microwell culture plate. We’ve also conducted a separate experiment to examine the association between the starting cell number of bEPSCs (1, 5, 10, 20, and 40) and their aggregate formation efficiency. Each well was precoated with 500 mL of Anti-Adherence Rinsing Solution, spun for 5 min at 1500 x g, and rinsed with 1mL of PBS before seeding. The co-cultured cells were mixed and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min, followed by resuspension with 1 mL N2B27 medium (DMEM: F12 and Neurobasal medium (1:1), 1x N2-supplement, 1x B27-supplement, 1x NEAA, 1x GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) with 5% KSR and 10 μM Y27632 before seeding into the plate. To ensure even distribution of the cells within each microwell, cells were gently mixed by pipetting with a P200 pipette. The plate was first placed in incubator for 8 min to allow the cells to settle down, then centrifuged at 700 x g for 3 min and put back to incubator. Half of the medium was changed daily, and the aggregation structures were cultured until day 4.

Karyotyping assay

bXENs were incubated with 1 mL KaryoMAX colcemid solution (Gibco, 15212012) at 38.5°C for 4–5 h. Cells were then dissociated using 1 mL Trypsin (Gibco, 25200–056) at 38.5°C and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS solution and centrifuged at 400 x g for 2 min. The supernatant was aspirated and 500 mL 0.56% KCI was added to resuspend the cells. The cells were incubated for 15 min, then centrifuged at 400 x g for 2 min 1 mL cold fresh Carnoy’s fixative (3:1 methanol: acetic acid) was added to resuspend the cells, followed by a 10 min incubation on ice. After centrifuge, 200 mL Carnoy’s fixative was added to resuspend the cells. Cells were dropped on the clean slides and air dried and soaked in a solution (1:25 of Giemsa stain (Sigma, GS500): deionized water) for 9 min. Slides were rinsed with deionized water and air dried. The images were taken by Leica DM6B at 1000x magnification under oil immersion.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells, blastoids, and blastocysts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature, and then rinsed in wash buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% polyvinyl pyrrolidone in PBS) three times. Following fixation, cells were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min and then rinsed with wash buffer. Samples were then transferred to blocking buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, 0.1 M glycine, 10% donkey serum) for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used in this experiment include anti-SOX2 (Biogenex, an833), anti-CDX2 (Biogenex, MU392A; 1:100), anti-GATA6 (R&D SYSTEMS, AF1700; 1:100), and anti-SOX17 (R&D SYSTEMS, AF1924; 1:100). For secondary antibody incubation, the cells were incubated with Fluor 488- or 555- or 647-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Followed by DAPI staining (Invitrogen, D1306) for 15 min. The images were taken with a fluorescence confocal microscope (Leica).

QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacture’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BIO-RAD). The qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (BIORAD) with specific primers (Table S2). Data was analyzed using the BIO-RAD software provided with the instrument. The relative gene expression values were calculated using the ΔΔCT method and normalized to internal control beta-actin.

RNA-seq library preparation and data analysis

Total RNA of bXENs was extracted using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). The RNA-seq libraries were generated using the Smart-seq2 v4 kit with minor modifications from the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, individual cells were lysed, and mRNA was captured and amplified with the Smart-seq2 v4 kit (Clontech). After AMPure XP beads purification, the high-quality amplified RNAs were subject to library preparation using Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) and multiplexed by Nextera XT Indexes (Illumina). The concentration of sequencing libraries was determined using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies) and KAPA Library Quantification Kits (KAPA Biosystems). The size of sequencing libraries was determined using the Agilent D5000 ScreenTape with Tapestation 4200 system (Agilent). Pooled indexed libraries were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X platform with 150-bp pair-end reads.

Multiplexed sequencing reads that passed filters were trimmed to remove low-quality reads and adaptors by Trim Galore (version 0.6.7) (-q 25 –length 20 –max_n 3 –stringency 3). The quality of reads after filtering was assessed by FastQC, followed by alignment to the bovine genome (ARS-UCD1.3) by HISAT2 (version 2.2.1) with default parameters. The output SAM files were converted to BAM files and sorted using SAMtools6 (version 1.14). Read counts of all samples were quantified using featureCounts (version 2.0.1) with the bovine genome as a reference and were adjusted to provide counts per million (CPM) mapped reads. Principal component analysis and cluster analysis were performed with R (a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using edgeR in R. Genes were considered differentially expressed when they provided a false discovery rate of <0.05 and fold change >2. ClusterProfiler was used to reveal the Gene Ontology and KEGG pathways in R.

ATAC-seq library preparation and data analysis

The ATAC-seq libraries from fresh cells were prepared as previously described.53 Shortly, cells were lysed on ice, then incubated with the Tn5 transposase (TDE1, Illumina) and tagmentation buffer. Tagmentated DNA was purified using MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). The ATAC-seq libraries were amplified by Illumina TrueSeq primers and multiplexed by index primers. Finally, high quality indexed libraries were pooled together and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq platform with 150-bp paired-end reads.

The ATACseq analysis followed our established analysis pipeline.53 All quality assessed ATAC-seq reads were aligned to the bovine reference genome using Bowtie 2.3 with following options: –very-sensitive -X 2000 –no-mixed –no-discordant. Alignments resulted from PCR duplicates or locations in mitochondria were excluded. Only unique alignments within each sample were retained for subsequent analysis. ATAC-seq peaks were called separately for each sample by MACS2 with following options: –keep-dup all – nolambda –nomodel. The ATAC-seq bigwig files were generated using bamcoverage from deeptools. The ATAC-seq signals were normalized in the Integrative Genome Viewer genome browser. The enrichment of transcriptional factor motifs in peaks was evaluated using HOMER (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/motif/).

Single nuclei isolation and snRNA-seq library preparation

The snRNA-seq libraries from frozen blastoids and day 8 blastocysts were prepared using Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit (10x Genomics, PN-1000493) with minor modifications from the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, frozen blastoids and day 8 blastocysts were transferred to pre-chilled sample dissociation tube and were dissociated with pestle within lysis buffer, then the tube was incubated on ice for 7 min. Then the dissociated sample was pipetted onto assembled nuclei isolation column and centrifuged 16,000 x rcf for 20 s. After being washed with debris removal buffer and wash buffer, the nuclei pellet was resuspended in 50 μL resuspension buffer and performed cell counting. Nucleus were loaded into a 10x Genomics Chromium Chip following manufacturer instruction (10x Genomics, Chromium Next GEM Single Cel 3′ Reagent Kit v3.1 Dual Index) and sequenced with an Illumina Novaseq 6000 System (Novogene).

snRNA-seq data analysis

To analyze 10X Genomics single-cell data, the base call files (BCL) were transferred to FASTQ files by using CellRanger (v.7.1.0) mkfastq with default parameters, followed by aligning to the most recent bovine reference genome downloaded from Ensembl database (UCD1.3), then the doublets were detected and removed from single cells by using Scrublet (0.2.3) with default parameters. The generated count matrices from all the samples were integrated by R package Seurat (4.3.0) utilizing canonical correlation analysis (CCA) with default parameters (https://satijalab.org/seurat/archive/v2.4/immune_alignment.html). The data was scaled for linear dimension reduction and non-linear reduction using principal component analysis (PCA) and UMAP, respectively. The following clustering and visualization were performed by using the Seurat standard workflow with the parameters ‘‘dim = 1:10’’ in ‘‘FindNeighbors’’ function and ‘‘resolution = 0.5’’ in ‘‘FindClusters’’ function. The function ‘‘FindAllMarkers’’ in Seurat was used to identify differentially expressed genes in each defined cluster. The cutoff value to define the differentially expressed genes was p.adjust value < 0.05, and fold change >0.25. The UMAP plots and bubble plots with marker genes were generated using ‘‘CellDimPlot’’ and ‘‘GroupHeatmap’’ functions in R package SCP (0.4.0) (https://github.com/zhanghao-njmu/SCP), respectively. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis were performed using R package clusterProfiler (4.6.1).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) unless otherwise stated. Two-tailed unpaired or paired t-tests were used to determine the significance of differences between the means of two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons was used to determine the significance of differences among means of more than two groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of sequencing data were performed in R. Genes with |fold change| >2 and p value <0.05 were identified as significant DEGs. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis were performed using R package clusterProfiler (4.6.1). The value of p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115707.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Anti- SOX17 | R&D SYSTEMS | Cat. No. AF1924 |

| Anti- GATA6 | R&D SYSTEMS | Cat. No. AF1700 |

| Anti- SOX2 | Biogenex | Cat. No. AN833 |

| Anti- CDX2 | Biogenex | Cat. No. AM3920324 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 anti-rabbit antibody | Invitrogen | Cat. No. A31573; RRID: AB_2536183 |

| Alexa Fluor 555 anti-mouse antibody | Invitrogen | Cat. No. A31570; RRID: AB_2536180 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-goat antibody | Invitrogen | Cat. No. A32814; RRID: AB_2762838 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| Recombinant human LIF | Peprotech | Cat. No. 300–05 |

| CHIR99021 | Sigma | Cat. No. SML-1046 |

| Dimethinedene maleate | Tocris | Cat. No. 14–251-0 |

| Minocycline hydrochloride | Santa cruz | Cat. No. sc-203339 |

| Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium- Ethanolamine (ITS-X) | Gibco | Cat. No. 51500056 |

| PD0325901 | Axon Medchem | Cat. No. 1408 |

| Recombinant Human FGF-basic | Peprotech | Cat. No. 100–18B |

| Recombinant Human/Murine/Rat Activin A | Prepotech | Cat. No. 120–14p |

| Emricasan | Selleckchem | Cat. No. 50–136-5234 |

| Polyamine supplement 5mL | Sigma | Cat. No. P8483 |

| trans-ISRIB,10mg | Tocris | Cat. No. 5284 |

| Chroman 1 (HY15392), 5mg | Medchemexpress | Cat. No. 502029121 |

| mTeSR™ 1 | STEMCELL | Cat. No. 85850 |

| WH-4–023 | Tocris | Cat. No. 5413 |

| endo-IWR 1 | Sigma | Cat. No. I0161 |

| XAV-939 | Sigma | Cat. No. X3004 |

| L-Ascorbic acid 2-phosphate | Sigma | Cat. No. A92902 |

| FGF4 | sigma | Cat. No. F8424 |

| BMP4 | R&D SYSTEMS | Cat. No. 314-BP-050/CF |

| IL-6 | Sigma | Cat. No. SRP3096 |

| A83–01 | Sigma | Cat. No. SML0788 |

| Knockout™ SR | Gibco | Cat. No. 10828–028 |

| PDGF | R&D SYSTEMS | Cat. No. BT220–010/CF |

| DMEM | Gibco | Cat. No. 11995–040 |

| FBS | Gibco | Cat. No. 26140–079 |

| Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (1X), no calcium, no magnesium (DPBS) | Sigma | Cat. No. D8537 |

| Y-27632 | Tocris | Cat. No. 1254 |

| DMEM/F12 medium | HyClone | Cat. No. SH30023.01 |

| Neurobasal medium | Gibco | Cat. No. 21103–049 |

| N2 supplement (100X) | Gibco | Cat. No. 17502–048 |

| B27 supplement (50X) | Gibco | Cat. No. 17504044 |

| MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (100X) | Gibco | Cat. No. 11140–050 |

| GlutaMAX™ Supplement (100X) | Gibco | Cat. No. 35050061 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol (55mM) | Gibco | Cat. No. 21985023 |

| Accutase | Gibco | Cat. No. A1110501 |

| Tn5 transposase | illumina | Cat. No. 20034197 |

| BSA | MP Biomedicals | Cat. No. 0219989950 |

| TrypLE_ Express | Gibco | Cat. No. 12605–010 |

|

| ||

| Critical commercial assays | ||

|

| ||

| KaryoMax colcemid solution | Gibco | Cat. No. 15212012 |

| Feeder removal MicroBeads, mouse | Miltenybiotec | Cat. No. 130–095-531 |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| bXENs RNAseq, ATACseq | This paper | GEO: GSE283042 |

| bTSCs RNAseq | Wang et al.24 | GEO: GSE220923 |

| bEPSCs RNAseq | Zhao et al.23 | GEO: GSE129760 |

| D12-D18 elongation scRNAseq | Scatolin et al.7 | GEO: GSE234335 |

| hXENs, hNESCs, hPESCs RNAseq | Okubo et al.20 | GEO: GSE131747 |

| mXENs, mESCs RNAseq | Zhong et al.26 | GEO: GSE106158 |

| Blastocyst snRNAseq | This paper | GEO: GSE283048 |

| EPTX-Blastoid snRNAseq | This paper | GEO: GSE283048 |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| CellRanger (v.7.1.0) | 10x Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cellgene-pression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger |

| Seurat (v.4.3.0) | Satija et al.43 | https://github.com/satijalab/seurat |

| SCP (v.0.4.0) | N/A | https://github.com/zhanghao-njmu/SCP |

| clusterProfiler (v.4.6.1) | Yu et al.44 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html |

| HISAT2 (v.2.2.1) | Kim et al.45 | http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/ |

| EdgeR (v.4.2.1) | Robinson et al.46 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html |

| bowtie2 (v. 2.5.1) | Langmead and Salzberg47 | https://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| IGV | Robinson et al.48 | https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/ |

| HOMER | Heinz et al.49 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/motif/ |

| Trim Galore (v.0.6.7) | N/A | http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/ |

| featureCounts (v.2.0.1) | Liao et al.50 | https://subread.sourceforge.net/featureCounts.html |

| MACS2 (v. 2.2.9.1) | Zhang et al.51 | https://pypi.org/project/MACS2/ |

| SAMtools (v.1.17) | Danecek et al.52 | https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| GraphPad Prism 8 | N/A | N/A |

| R 4.4.1 | N/A | N/A |

| BioRender | N/A | https://app.biorender.com/ |

|

| ||

| Other | ||

|

| ||

| AggreWell 400 | STEMCELL | Cat. No. 34415 |

| Anti-Adherence Rinsing | STEMCELL | Cat. No. 07010 |

| CELLBANKER 1 | AMSBIO | Cat. No. 11910 |

| CELLBANKER 2 | AMSBIO | Cat. No. 11914 |

| Smart-seq2 v4 kit | Takara Bio | Cat. No. 634897 |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit | illumina | Cat. No. 15032350 |

| Nextera XT Indexes | illumina | Cat. No. 15052163 |

| Chromium Controller & Next GEM Accessory Kit | 10X Genomics | Cat. No. 000204 |

| Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit | 10X Genomics | Cat. No. PN-1000494 |

| Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit | 10X Genomics | Cat. No. 1000127 |

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ Kit v3.1 | 10X Genomics | Cat. No. 1000269 |

Highlights.

Robust and efficient generation of bXENs from blastocyst

bXENs exhibit key molecular and cellular features of primitive endoderm progenitors

bXENs regulate the development of bEPSCs and pre-implantation epiblasts

Generation of bovine blastoids by assembly of bXENs, bEPSCs, and bTSCs

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD102533) and Genus plc.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Z.J and H.M are co-inventors on US provisional patent application 63/734,491 relating to bXENs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moerkamp AT, Paca A, Goumans MJ, Kunath T, Kruithof BPT, and Kruithof-de Julio M (2013). Extraembryonic endoderm cells as a model of endoderm development. Dev. Growth Differ 55, 301–308. 10.1111/dgd.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton GJ, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Skepper JN, and Jauniaux E (2002). Uterine glands provide histiotrophic nutrition for the human fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 87, 2954–2959. 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton GJ, Hempstock J, and Jauniaux E (2001). Nutrition of the human fetus during the first trimester–a review. Placenta 22, S70–S77. 10.1053/plac.2001.0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assis Neto AC, Pereira FTV, Santos TC, Ambrosio CE, Leiser R, and Miglino MA (2010). Morpho-physical recording of bovine conceptus (Bos indicus) and placenta from days 20 to 70 of pregnancy. Reprod. Domest. Anim 45, 760–772. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assis Neto AC, Santos ECC, Pereira FTV, and Miglino MA (2009). Initial development of bovine placentation (Bos indicus) from the point of view of the allantois and amnion. Anat. Histol. Embryol 38, 341–347. 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2009.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbot NC, Caperna TJ, Powell AM, Ealy AD, Blomberg LA, and Garrett WM (2005). Isolation and characterization of a bovine visceral endoderm cell line derived from a parthenogenetic blastocyst. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim 41, 130–141. 10.1290/040901.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scatolin GN, Ming H, Wang Y, Iyyappan R, Gutierrez-Castillo E, Zhu L, Sagheer M, Song C, Bondioli K, and Jiang Z (2024). Single-cell transcriptional landscapes of bovine peri-implantation development. iScience 27, 109605. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.109605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunne LD, Diskin MG, and Sreenan JM (2000). Embryo and foetal loss in beef heifers between day 14 of gestation and full term. Anim. Reprod. Sci 58, 39–44. 10.1016/s0378-4320(99)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henricks DM, Lamond DR, Hill JR, and Dickey JF (1971). Plasma progesterone concentrations before mating and in early pregnancy in the beef heifer. J. Anim. Sci 33, 450–454. 10.2527/jas1971.332450x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diskin MG, and Sreenan JM (1980). Fertilization and embryonic mortality rates in beef heifers after artificial insemination. J. Reprod. Fertil 59, 463–468. 10.1530/jrf.0.0590463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossant J (2008). Stem cells and early lineage development. Cell 132, 527–531. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunath T, Arnaud D, Uy GD, Okamoto I, Chureau C, Yamanaka Y, Heard E, Gardner RL, Avner P, and Rossant J (2005). Imprinted X-inactivation in extra-embryonic endoderm cell lines from mouse blastocysts. Development 132, 1649–1661. 10.1242/dev.01715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohinata Y, Endo TA, Sugishita H, Watanabe T, Iizuka Y, Kawamoto Y, Saraya A, Kumon M, Koseki Y, Kondo T, et al. (2022). Establishment of mouse stem cells that can recapitulate the developmental potential of primitive endoderm. Science 375, 574–578. 10.1126/science.aay3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park CH, Jeoung YH, Uh KJ, Park KE, Bridge J, Powell A, Li J, Pence L, Zhang L, Liu T, et al. (2021). Extraembryonic Endoderm (XEN) Cells Capable of Contributing to Embryonic Chimeras Established from Pig Embryos. Stem Cell Rep 16, 212–223. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang ML, Jin Y, Zhao LH, Zhang J, Zhou M, Li MS, Yin ZB, Wang ZX, Zhao LX, Li XH, and Li RF (2021). Derivation of Porcine Extra-Embryonic Endoderm Cell Lines Reveals Distinct Signaling Pathway and Multipotency States. Int. J. Mol. Sci 22, 12918. 10.3390/ijms222312918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Y, Zhang E, Yu L, Ci B, Sakurai M, Guo L, Zhang X, Lin S, Takii S, Liu L, et al. (2023). Dissecting embryonic and extraembryonic lineage crosstalk with stem cell co-culture. Cell 186, 5859–5875.e24. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linneberg-Agerholm M, Wong YF, Romero Herrera JA, Monteiro RS, Anderson KGV, and Brickman JM (2019). Naive human pluripotent stem cells respond to Wnt, Nodal and LIF signalling to produce expandable naive extra-embryonic endoderm. Development 146, dev180620. 10.1242/dev.180620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho LTY, Wamaitha SE, Tsai IJ, Artus J, Sherwood RI, Pedersen RA, Hadjantonakis AK, and Niakan KK (2012). Conversion from mouse embryonic to extra-embryonic endoderm stem cells reveals distinct differentiation capacities of pluripotent stem cell states. Development 139, 2866–2877. 10.1242/dev.078519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dattani A, Corujo-Simon E, Radley A, Heydari T, Taheriabkenar Y, Carlisle F, Lin S, Liddle C, Mill J, Zandstra PW, et al. (2024). Naive pluripotent stem cell-based models capture FGF-dependent human hypoblast lineage specification. Cell Stem Cell 31, 1058–1071.e5. 10.1016/j.stem.2024.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okubo T, Rivron N, Kabata M, Masaki H, Kishimoto K, Semi K, Nakajima-Koyama M, Kunitomi H, Kaswandy B, Sato H, et al. (2024). Hypoblast from human pluripotent stem cells regulates epiblast development. Nature 626, 357–366. 10.1038/s41586-023-06871-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang QE, Fields SD, Zhang K, Ozawa M, Johnson SE, and Ealy AD (2011). Fibroblast growth factor 2 promotes primitive endoderm development in bovine blastocyst outgrowths. Biol. Reprod 85, 946–953. 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MK, Clark CC, and McCoski SR (2020). Technical note: improving the efficiency of generating bovine extraembryonic endoderm cells. J. Anim. Sci 98, skaa222. 10.1093/jas/skaa222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao L, Gao X, Zheng Y, Wang Z, Zhao G, Ren J, Zhang J, Wu J, Wu B, Chen Y, et al. (2021). Establishment of bovine expanded potential stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018505118. 10.1073/pnas.2018505118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Ming H, Yu L, Li J, Zhu L, Sun HX, Pinzon-Arteaga CA, Wu J, and Jiang Z (2023). Establishment of bovine trophoblast stem cells. Cell Rep 42, 112439. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinzon-Arteaga CA, Wang Y, Wei Y, Ribeiro Orsi AE, Li L, Scatolin G, Liu L, Sakurai M, Ye J, Hao M, et al. (2023). Bovine blastocyst-like structures derived from stem cell cultures. Cell Stem Cell 30, 611–616.e7. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong Y, Choi T, Kim M, Jung KH, Chai YG, and Binas B (2018). Isolation of primitive mouse extraembryonic endoderm (pXEN) stem cell lines. Stem Cell Res 30, 100–112. 10.1016/j.scr.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer TE, Forde N, and Lonergan P (2016). Insights into conceptus elongation and establishment of pregnancy in ruminants. Reprod. Fertil. Dev 29, 84–100. 10.1071/RD16359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weatherbee BAT, Gantner CW, Iwamoto-Stohl LK, Daza RM, Hamazaki N, Shendure J, and Zernicka-Goetz M (2023). Pluripotent stem cell-derived model of the post-implantation human embryo. Nature 622, 584–593. 10.1038/s41586-023-06368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuijk EW, van Tol LTA, Van de Velde H, Wubbolts R, Welling M, Geijsen N, and Roelen BAJ (2012). The roles of FGF and MAP kinase signaling in the segregation of the epiblast and hypoblast cell lineages in bovine and human embryos. Development 139, 871–882. 10.1242/dev.071688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossant J, and Tam PPL (2017). New Insights into Early Human Development: Lessons for Stem Cell Derivation and Differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 20, 18–28. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canizo JR, Ynsaurralde Rivolta AE, Vazquez Echegaray C, Suvá M, Alberio V, Aller JF, Guberman AS, Salamone DF, Alberio RH, and Alberio R (2019). A dose-dependent response to MEK inhibition determines hypoblast fate in bovine embryos. BMC Dev. Biol 19, 13. 10.1186/s12861-019-0193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ming H, Zhang M, Rajput S, Logsdon D, Zhu L, Schoolcraft WB, Krisher RL, Jiang Z, and Yuan Y (2024). In vitro culture alters cell lineage composition and cellular metabolism of bovine blastocystdagger. Biol. Reprod 111, 11–27. 10.1093/biolre/ioae031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross C, and Boroviak TE (2020). Origin and function of the yolk sac in primate embryogenesis. Nat. Commun 11, 3760. 10.1038/s41467-020-17575-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang J, Wang H, Zhang Y, Wang J, Liu F, Han X, Lu Z, Li C, Li Z, Gao Y, et al. (2021). LCDM medium supports the derivation of bovine extended pluripotent stem cells with embryonic and extraembryonic potency in bovine-mouse chimeras from iPSCs and bovine fetal fibroblasts. FEBS J 288, 4394–4411. 10.1111/febs.15744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo G, Stirparo GG, Strawbridge SE, Spindlow D, Yang J, Clarke J, Dattani A, Yanagida A, Li MA, Myers S, et al. (2021). Human naive epiblast cells possess unrestricted lineage potential. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1040–1056.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linneberg-Agerholm M, Sell AC, Redo-Riveiro A, Perera M, Proks M, Knudsen TE, Barral A, Manzanares M, and Brickman JM (2024). The primitive endoderm supports lineage plasticity to enable regulative development. Cell 187, 4010–4029.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Tan JP, Schröder J, Aberkane A, Ouyang JF, Mohenska M, Lim SM, Sun YBY, Chen J, Sun G, et al. (2021). Modelling human blastocysts by reprogramming fibroblasts into iBlastoids. Nature 591, 627–632. 10.1038/s41586-021-03372-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu L, Wei Y, Duan J, Schmitz DA, Sakurai M, Wang L, Wang K, Zhao S, Hon GC, and Wu J (2021). Blastocyst-like structures generated from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature 591, 620–626. 10.1038/s41586-021-03356-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kagawa H, Javali A, Khoei HH, Sommer TM, Sestini G, Novatchkova M, Scholte Op Reimer Y, Castel G, Bruneau A, Maenhoudt N, et al. (2022). Human blastoids model blastocyst development and implantation. Nature 601, 600–605. 10.1038/s41586-021-04267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao C, Reyes AP, Schell JP, Weltner J, M. Ortega N, Zheng Y, Björklund K, Rossant J, Fu J, Petropoulos S, and Lanner F (2021). Reprogrammed blastoids contain amnion-like cells but not trophectoderm. Preprint at bioRxiv. 10.1101/2021.05.07.442980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amadei G, Handford CE, Qiu C, De Jonghe J, Greenfeld H, Tran M, Martin BK, Chen DY, Aguilera-Castrejon A, Hanna JH, et al. (2022). Embryo model completes gastrulation to neurulation and organogenesis. Nature 610, 143–153. 10.1038/s41586-022-05246-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau KYC, Rubinstein H, Gantner CW, Hadas R, Amadei G, Stelzer Y, and Zernicka-Goetz M (2022). Mouse embryo model derived exclusively from embryonic stem cells undergoes neurulation and heart development. Cell Stem Cell 29, 1445–1458.e8. 10.1016/j.stem.2022.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM 3rd, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, and Satija R (2019). Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, and He QY (2012). clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287. 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, and Salzberg SL (2019). Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol 37, 907–915. 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, and Smyth GK (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. 10.1093/bio-informatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langmead B, and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, and Mesirov JP (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol 29, 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, and Glass CK (2010). Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao Y, Smyth GK, and Shi W (2014). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, and Liu XS (2008). Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9, R137. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, and Li H (2021). Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10, giab008. 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ming H, Sun J, Pasquariello R, Gatenby L, Herrick JR, Yuan Y, Pinto CR, Bondioli KR, Krisher RL, and Jiang Z (2021). The landscape of accessible chromatin in bovine oocytes and early embryos. Epigenetics 16, 300–312. 10.1080/15592294.2020.1795602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Y, Tristan CA, Chen L, Jovanovic VM, Malley C, Chu PH, Ryu S, Deng T, Ormanoglu P, Tao D, et al. (2021). A versatile polypharmacology platform promotes cytoprotection and viability of human pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat. Methods 18, 528–541. 10.1038/s41592-021-01126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw FASTQ files and normalized read accounts per gene are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession numbers GSE283042 and GSE283048. This paper analyzes publicly available data. The accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.