Abstract

The p27Kip1 protein is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that blocks cell division in response to antimitogenic cues. p27 expression is reduced in many human cancers, and p27 functions as a tumor suppressor that exhibits haploinsufficiency in mice. Despite the well characterized role of p27 as a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, its mechanism of tumor suppression is unknown. We used Moloney murine leukemia virus to induce lymphomas in p27+/+ and p27−/− mice and observed that lymphomagenesis was accelerated in the p27−/− animals. To identify candidate oncogenes that collaborate with p27 loss, we used a high-throughput strategy to sequence 277 viral insertion sites derived from two distinct sets of p27−/− lymphomas and determined their chromosomal location by comparison with the Celera and public (Ensembl) mouse genome databases. This analysis identified a remarkable number of putative protooncogenes in these lymphomas, which included loci that were novel as well as those that were overrepresented in p27−/− tumors. We found that Myc activations occurred more frequently in p27−/− lymphomas than in p27+/+ tumors. We also characterized insertions within two novel loci: (i) the Jun dimerization protein 2 gene (Jundp2), and (ii) an X-linked locus termed Xpcl1. Each of the loci that we found to be frequently involved in p27−/− lymphomas represents a candidate oncogene collaborating with p27 loss. This study illustrates the power of high-throughput insertion site analysis in cancer gene discovery.

Mutations in genes that regulate the cell cycle are among the most common genetic changes in cancer cells (1). Cell cycle genes that promote cell proliferation are often found as dominant oncogenes that have acquired gain-of-function mutations in cancer cells (e.g., cyclin D1). In contrast, components of the cell cycle machinery that normally inhibit cell division act as tumor suppressors and are frequently inactivated in cancer cells (e.g., p53). The p27 protein is a member of the Cip/Kip family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and mediates cell cycle arrest in response to diverse antimitogenic signals (2). Many human cancers show reduced or absent p27 expression compared with normal tissues, and low p27 expression correlates with poor patient outcome in a range of primary tumors (3–5). Unlike classic tumor suppressors, intragenic mutations leading to homozygous p27 inactivation are very rare in human cancers, and the mechanisms underlying p27 loss in these tumors appear to be primarily posttranscriptional (6). Thus despite a large body of data correlating p27 abundance with tumorigenesis, the lack of mutations within the p27 gene in tumors has made it difficult to unambiguously establish that p27 functions as a tumor suppressor in humans.

In mice, however, p27 clearly functions as a tumor suppressor that exhibits haploinsufficiency. p27 knockout mice exhibit a syndrome of gigantism, pituitary and lymphoid hyperplasia, and female sterility (7–9). Although p27−/− mice develop pituitary adenomas with 100% penetrance, they do not exhibit a widespread cancer syndrome like those found in mice nullizygous for tumor suppressors such as p53 or p19ARF (10, 11). However, p27−/− mice develop tumors at a greater frequency than do p27+/+ animals when challenged with radiation or chemical carcinogens, and p27+/− animals have a tumor frequency intermediate between p27+/+ and p27−/− animals (12). Furthermore, loss of p27 in mice cooperates with deletion of the Pten tumor suppressor in the development of prostate cancer, and this cooperativity also exhibits p27 haploinsufficiency (13). This association of reduced (but not absent) p27 expression with tumor-prone phenotypes in mice supports the idea that reduced p27 expression in human cancers may have similar consequences.

p27 expression does not uniformly correlate with markers of cell proliferation in tumors, and its mechanism of tumor suppression remains unclear. We thus sought to identify oncogenes that collaborate with p27 loss to characterize the transformation pathways involved with p27-associated tumorigenesis. We used Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) to induce lymphomas in p27−/− and p27+/+ mice. M-MuLV is a nonacute retrovirus that induces neoplasms through insertional mutagenesis (14). Proviral integration within host cell DNA activates cellular protooncogenes by placing them under the control of viral transcriptional regulatory elements. The principle advantage of this strategy is that the M-MuLV proviruses serve as molecular tags that allow for identification of activated genes that are usually close to the proviral insertion. Because viral insertions occur randomly within host DNA, common sites of viral insertion in multiple independent tumors indicate strong biologic selection for these specific integrations. Common insertion sites (CIS) are thus extremely likely to harbor protooncogenes.

In a landmark study, Copeland and coworkers combined insertional mutagenesis with functional genomics and reported a large-scale analysis of cloned proviral insertion sites that identified more than 90 candidate cancer genes in leukemias arising in AKXD and BXHD mice (15). M-MuLV has also been used extensively to characterize cooperation between oncogenes in multistep tumorigenesis. For example, M-MuLV infection of Eμ-Myc transgenic mice led to the characterization of several novel oncogenes that cooperate with Myc activation during lymphomagenesis (16, 17). In these experiments, lymphomagenesis was accelerated in the Eμ-Myc mice compared with the wild-type animals, because the Myc transgene provided the first step in a multistep pathway leading to lymphomas.

We found that M-MuLV-induced lymphomagenesis was greatly accelerated in p27-null mice compared with wild-type animals. We analyzed known M-MuLV targets and found that integrations leading to activation of Myc-related genes occurred more often in p27-null animals, thus identifying Myc activation as an event that may cooperate with p27 loss in lymphomagenesis. To identify additional p27-complementing oncogenes, we performed a large-scale analysis in which 277 insertion sites derived from two independent panels of p27-null lymphomas were sequenced and compared with the mouse genome databases. This analysis reveals a remarkable number of CIS within this group of lymphomas and illustrates the power of high-throughput insertional mutagenesis using the mouse genome sequence in cancer gene discovery. Several of the CIS we identified were overrepresented in the p27-null tumors. Two of these sites were analyzed in further detail: (i) Jundp2, and (ii) an X-linked locus termed Xpcl1 (X-linked p27-complementing locus 1. To our knowledge, this is the first report that Jundp2 functions as a protooncogene.

Materials and Methods

M-MuLV Infection of p27+/+ and p27−/− Mice.

For panel one lymphomas, mice +/− for the p27 gene were generated as previously described in C57Bl6 and 129 strains (9). Crosses between inbred F0 p27+/− parental mice were performed to generate F1 C57/B6J × 129/Sv hybrid littermates that were p27+/+, p27±, or p27−/−. Newborn pups were injected i.p. with M-MuLV (1 × 107 pfu) [Dusty Miller, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC)] and genotyped as described (9). Panel two lymphomas were generated in a similar fashion as described (18). Animals were followed for the development of tumors and euthanized when they developed signs of morbidity. At necropsy, tumor tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen.

DNA Isolation and Southern Analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen M-MuLV-generated tumors and Southern blots prepared (17). Southern blots were then hybridized to [α-32P]-labeled probes generated by random priming. Final wash steps were performed in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS at 60°C. Probe and primer sequences (where applicable) are available on request.

Insertion Site Cloning and Sequencing.

Inverse PCR (I-PCR): I-PCR was performed as previously described (15, 17). I-PCR primers: SacI, KpnI, and HhaI I-PCR; AB827, AB946, and AB949; 5′ SacII I-PCR, SacII5 (5′-CCGTTAAACAGGGAACTAGGGT), AB827, AB949; 3′ SacII I-PCR, SacII3 (5′-CTCCCAATGAGTGCCGGGCCGA), AB946, and AB947 (5′-AGTGATTGACTACCCGTCAGCG-3′) (15, 17). PCR products were subcloned by using Topo cloning (Invitrogen). All sequencing was performed in the FHCRC automated sequencing shared resource.

Splinkerette Method.

For panel two proviral flanking sequences, tumor DNA was digested with Sau3AI, ligated to a Splinkerette adapter, and amplified by three PCR steps by using long-terminal repeat (LTR) and Splinkerette-specific primers, which are available on request (19). The resulting PCR fragments were sequenced and blasted against mouse genome databases.

Real-Time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). Triplicate 50-μl reactions containing 5 μl of tumor or control thymic cDNA, 25 μl of ×2 Taqman Universal Master mix, probe (0.1 μM final concentration), and primers (0.2 μM final concentration) for Jundp2, Fos, AI464896 expressed sequence tag (EST), and mouse Gapdh were prepared. Samples were cycled in 96-well plates per manufacturer's instructions and data analyzed by using sds Software (Applied Biosystems). The expression levels for Jundp2, Fos, and AI464896 EST were normalized to Gapdh expression. Probe and primer sequences are available on request.

Immunoperoxidase Staining of Frozen Tumor Sections.

Six-micrometer sections of frozen tumor samples were prepared, and then immunocytochemistry was performed by using antibodies to CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD45R/B220 (PharMingen clones L3T4, Ly-2, 17A2, and RA3–6B2, respectively). Slides were fixed in 10% normal buffered formalin 10 min and then incubated in the following solutions: PBS, 5 min; 100% methanol, 5 min; acetone, 3 min; and PBS ×3 for 10 min. Slides were blocked in 2% normal goat serum for 10 min followed by incubation in 1° Ab for 1 hr and then 2° Ab for 30 min (all incubations were performed at 25°C). Signals were then visualized by using the ABC elite kit (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories).

Xpcl1 Genomic Cloning.

A mouse genomic lambdaDash II (Stratagene) DNA was obtained from P. Soriano (FHCRC). The phage were grown in ER1647, and nylon replica filters were generated and hybridized to an Xpcl1 probe. Positive plaques were isolated, purified, and subcloned into pBluescript and sequenced by using T7 and SP6 primers.

Results

M-MuLV-Induced Lymphomagenesis Is Accelerated in p27−/− Animals.

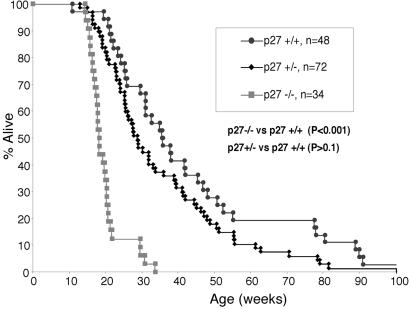

We infected neonatal p27−/−, p27±, and p27+/+ pups with M-MuLV. Mice were killed when moribund, and tissue was banked for molecular and biochemical studies. Lymphomagenesis was significantly accelerated in p27−/− animals (median survival 18 weeks) compared with p27+/+ mice (median survival 35 weeks) (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). The p27+/− mice had a survival curve that was moderately accelerated compared with p27+/+ mice, but this did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.1). Immunophenotypic and histologic analyses demonstrated that lymphomas were almost exclusively of T cell origin. The lymphomas included CD4+CD8+, CD4+CD8−, CD4−CD8+, and CD4−CD8− immunophenotypes. There were no significant differences in the frequency of lymphoma immunophenotypes between the p27−/− and p27+/+ groups (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Acceleration of lymphomagenesis in p27−/− mice infected with M-MuLV. (A) Survival of p27−/−, p27+/−, and p27−p27+/+ mice is plotted against weeks after infection with M-MuLV.

Increased Frequency of Myc Activations in p27−/− Lymphomas.

We screened 25 p27−/− and 25 p27+/+ lymphoma DNAs by Southern blotting for involvement of previously defined M-MuLV CIS. A M-MuLV U3 LTR probe demonstrated that the lymphomas contained between 2 and 12 clonal viral insertions, and the number of insertions did not vary significantly between the p27−/− and p27+/+ groups (data not shown). We then determined the frequency of insertions within several known CIS in these lymphomas. Pim1 and Gfi1 insertions occurred with similar frequencies in p27−/− and p27+/+ mice (Table 1). Neither the total number of viral insertions per tumor nor the frequency of CIS such as Gfi1 and Pim1 was increased in the p27−/− lymphomas, indicating that p27 loss does not accelerate lymphomagenesis by increasing the total number of viral insertions in target cells. In contrast, insertional activation of Myc occurred more frequently in p27−/− compared with p27+/+ mice (Table 1; P = 0.0031). This overrepresentation of Myc activation in p27−/− lymphomas strongly suggests that Myc cooperates with p27 loss. In support of this idea, synergism between Myc activation and p27 loss was also observed in independent models of Myc-associated lymphomagenesis by Martins and Berns, who observed acceleration of T and B cell lymphomas when p27−/− animals were crossed with strains containing H2K-Myc and Eμ-Myc transgenes, respectively (19).

Table 1.

Involvement of M-MuLV insertion sites in p27-null and p27 wild-type lymphomas by Southern analysis

| Locus | p27-null tumors | p27 wild-type tumors | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myc | 14/25 (56%) | 4/25 (16%) | 0.0031 |

| Pim1 | 7/25 (28%) | 6/25 (24%) | – |

| Gfi1 | 1/25 (4%) | 2/25 (8%) | – |

| Jundp2 | 7/25 (28%) | 2/25 (8%) | 0.058 |

| Xpcl1 | 7/25 (28%) | 1/25 (4%) | 0.0224 |

Includes Myc, Nmyc1, and Pvt1 loci.

Identification of Putative p27-Complementing Oncogenes by High-Throughput Insertion Site Analyses.

To identify novel oncogenic loci in the p27−/− tumors, we applied large-scale sequencing of genomic DNA adjacent to proviruses. The lymphomas used for this analysis were obtained from two independent panels of p27−/− lymphomas. Panel one consisted of the 25 p27−/− lymphomas described above, whereas panel two was composed of 45 p27−/− M-MuLV-induced lymphomas described by Martins and Berns (18). The two panels differed somewhat with regard to strain background, tumor latency, and surface markers. More importantly, however, the panels were quite similar in that in both lymphoma cohorts, p27 loss resulted in acceleration of M-MuLV-induced lymphomagenesis, as well as a high frequency of Myc activations. The insertion site sequences were obtained by I-PCR for panel one lymphomas and by an alternative PCR strategy (Splinkerette; see Materials and Methods) for panel two lymphomas. After the sequence tags were obtained, they were mapped by using both the Celera and public (Ensembl) mouse genome databases.

We sequenced a total of 277 insertion sites from these 70 p27−/− lymphomas. A complete list of these insertion sites is provided in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. We used the chromosomal location of these sites to identify candidate CIS (clones that fell within ≈100 kb of one another were considered to represent a CIS). The 21 CIS revealed by this analysis are presented in Table 2. The combination of the two tumor panels led to an increase in the number of CIS identified, as well as an increased frequency of insertions within sites identified in both panels. Remarkably, 35% (96/277) of all insertion sites represented putative CIS, indicating that a surprisingly large proportion of the viral insertions in these lymphomas may have contributed to their neoplastic progression.

Table 2.

CISs identified in p27-null lymphomas

|

|

Site no.

|

No. tumors

|

Chr

|

Celera annotation | Ensembl annotation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location, Mb | mCG no. | Gene description | Location, Mb | ENSMUSG no. | Gene description | ||||

| Clusters involving known proviral integration sites | 1 | 2 | 2 | 22.663–22.664 | 18747 | Notch1 | 26.754–26.755 | 26923 | Notch1 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 115.320–115.401 | 14557 | Rasgrp1 | 118.271–118.353 | 27347 | Rasgrp1 | |

| 3 | 20 | 5 | 100.520–100.577 | 19138 | Gfi1/Evi5 | 105.372–105.428 | 29275 | Gfi1/Evi5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 10 | 17.868–17.987 | 2825 | Myb | 21.003–21.130 | 19982 | Myb | |

| 5 | 3 | 12 | 9.894–9.895 | 19753 | NMyc1 | 13.030–13.031 | 37169 | Nmyc1 | |

| 6 | 20 | 15 | 56.913–57.145 | 1625 | Myc/Pvt1 | 62.430–62.663 | 22346 | Myc/Pvt1 | |

| 7 | 2 | 17 | 22.055–22.060 | 21141 | Pim1 | 28.704–28.708 | 24014 | Pim1 | |

| Clusters involving known or putative genes | 8 | 5 | 2 | 26.789–26.854 | 19005 | Unknown | 30.971–31.038 | 26859 | Unknown |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 161.340–161.374 | 5444 | Pkig | 164.575–164.608 | 35268 | Pkig | |

| 5448 | TDE1 homologue | 17707 | TDE1 homologue | ||||||

| 10 | 2 | 3 | 86.406–86.409 | 5011 | Rorc | 94.722–94.723 | 28150 | Rorc | |

| 11 | 2 | 4 | 130.357–130.361 | 20817 | veg homologue | 131.234–131.238 | 37543 | veg homologue | |

| 12 | 2 | 7 | 49.367–49.409 | 13842 | Igf1r | 57.651–57.693 | 05533 | Igf1r | |

| 13840 | Pyr.-Carboxylate peptidase | 30553 | Pyr.-carboxylate peptidase | ||||||

| 13 | 4 | 10 | 17.749–17.832 | 2824 | SH-3 Domain protein | 20.885–20.968 | 37571 | SH-3 domain protein | |

| 14 | 5 | 12 | 75.414–75.511 | 5743 | Jundp2 | 80.242–80.339 | 34271 | Jundp2 | |

| 15 | 2 | 19 | 32.634–32.650 | 49335 | Unknown | 38.507–38.522 | 24999 | Unknown | |

| Clusters between known or putative genes | 16 | 2 | 3 | 46.819–46.820 | 1650 | KIAA1816 homologue | 52.521–52.522 | 37078 | KIAA1816 homologue |

| 1648 | Foxo1 | 37068 | Foxo1 | ||||||

| 17 | 2 | 6 | 125.033–125.034 | 13072 | Tpi | 128.163–128.164 | 37997 | Unknown | |

| 13058 | Calm2 | 30349 | 40S ribosomal protein | ||||||

| 18 | 5 | 7 | 94.633–94.642 | 51745 | Rras2 | 103.790–103.797 | 38142 | Rras2 | |

| 2291 | Copb1 | 30754 | Copb1 | ||||||

| 19 | 2 | 9 | 67.173–67.175 | 16396 | Tcf12 | 72.772–72.775 | 32228 | Tcf12 | |

| 130222 | Ub. carboxy extension protein | 38657 | Ribosomal protein L40e | ||||||

| 20 | 2 | 11 | 76.252–76.253 | 1336 | Diphthamide DPH2 protein | 75.809–75.811 | 38268 | Diphthamide DPH2 protein | |

| 1330 | Replication protein A subunit | 00751 | Replication protein A subunit | ||||||

| 21 | 4 | X | 27.438–27.440 | 14311 | Pou transcription factor | 38.350–38.354 | 36050 | Repeat family 3 gene | |

| 50918 | Gpc3 | 31120 | Gpc3 | ||||||

Pyr., pyrrolidone; Ub., ubiquitin.

Chromosome.

Celera annotation based on the Celera Mouse Genome Database (CMGD Release 12).

Ensembl annotation based on the Public Mouse Genome Assembly (Ver. 6.3a.1). Both the Celera and Ensembl annotations include megabase (Mb) location, gene number, and annotated gene description.

For clusters falling between genes (sites 16–21), the nearest annotated genes on either side of the cluster are shown.

We identified three classes of CIS. The first class represented insertions near or within known M-MuLV protooncogene targets and includes Notch1, Rasgrp1, Gfi1/Evi5, Myb, NMyc1, Myc/Pvt1, and Pim1 loci (sites 1–7; Table 2) (17, 20–24). This group of insertions contained the most commonly identified sites and comprised over half of all sequence tags found within CIS (55/96, 58%).

The next most frequent group of CIS (24/96, 25%) overlapped with either known or predicted genes that have not been previously identified as CIS (sites 8–15; Table 2). Examples include Jundp2 and a novel SH3 domain-containing protein. The final class of insertions fell between annotated genes (20–200 kb distance). These insertions comprised ≈18% of all CIS identified (17/96, sites 16–22; Table 2).

For CIS that were near or within genes (classes 1 and 2), it is likely that the indicated genes are the targets of the integrations, although not all of the predicted genes have been experimentally determined to represent bona fide genes. For CIS that fell between genes (class 3), the target is less clear, particularly because proviruses in this class are quite distant from the closest mapped genes. In all cases, however, the putative targets must be validated by direct examination of mRNA in tumors containing the relevant viral insertions.

Identification of Jundp2 as a Protooncogene That Is Frequently Activated in p27−/− Lymphomas.

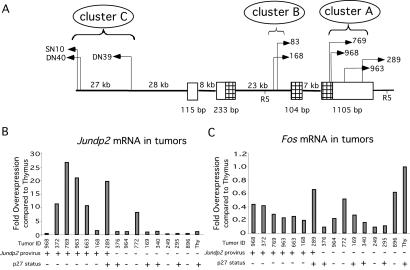

Site 14 (Table 2) represented insertions within and flanking Jundp2. Jundp2 is a member of the AP-1 family of b-zip transcription factors and was first cloned through its physical interaction with the Jun protein (24). More recently, Jundp2 overexpression was found to attenuate p53-dependent apoptosis in response to UV irradiation (25). Because Jundp2's known biologic activities suggested a link to tumorigenesis, site 14 was chosen for further analysis. By using a Jundp2-specific probe, we detected proviral rearrangements in a total of seven p27−/− and two p27+/+ lymphomas (Table 1). We have mapped the location of these insertions within Jundp2 by using the Celera database in combination with Southern blotting and grouped them into three clusters (A, B, and C; Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2, the proviral insertions in this locus included integrations within (clusters A and B) and flanking (cluster C) Jundp2.

Fig 2.

Jundp2 is a target for retroviral insertion in M-MuLV-induced lymphomas. (A) Genomic structure of the Jundp2 locus. The position and orientation of sequenced viral insertions (arrows) are shown (see text). Boxes denote the four Jundp2 exons (coding regions are hatched), and EcoRV sites are indicated (R5). (B) Expression of Jundp2 mRNA in M-MuLV-induced tumors and normal thymus (Thy). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using a first exon Jundp2 probe. (C) Expression of Fos mRNA in M-MuLV-induced tumors as determined by quantitative real-time PCR.

We next examined each cluster for evidence of Jundp2 activation. For clusters A and B, quantitative real-time PCR analysis using a Jundp2 exon 1 probe revealed that five of seven panel one lymphomas with Jundp2 insertions contained increased amounts of Jundp2 mRNA compared with lymphomas without Jundp2 insertions. In contrast, these same tumors did not exhibit increased expression of Fos, the closest linked gene to Jundp2 (Fig. 2C). Thus the insertions within the Jundp2 locus did not lead to generalized increased expression of all nearby genes but specifically enhanced Jundp2 expression. Two p27-null tumors with Jundp2 insertions did not show increased Jundp2 mRNA levels (tumors 968 and 168). In the case of tumor 168, the viral insertion occurred downstream of the exon 1 probe sequence used for measuring mRNA expression, and the truncated transcript does not contain the first exon (see below). Southern analysis revealed that the rearranged Jundp2 band for 968 was subclonal, thus the low levels of Jundp2 mRNA in this tumor may result from this subclone being underrepresented in this tumor sample.

We next characterized Jundp2 transcripts in two tumors (tumors 168 and 83) with integrations within cluster B to determine whether these insertions also caused Jundp2 activation. The location and orientation of these proviruses suggested that they might activate Jundp2 through promoter insertion, in which transcription initiates within the viral LTR and then splices to Jundp2 exons. Indeed, by using a directed PCR strategy, we cloned chimeric transcripts from cDNA derived from tumors 168 and 83 (data not shown). In each case, the transcript initiated in the LTR and spliced into Jundp2 exon 3 and 4 sequences. Finally, we examined Jundp2 expression by Northern blot in the three panel two lymphomas that contained cluster C insertions. The viruses in these lymphomas are all oriented in the opposite transcriptional orientation from Jundp2, suggesting a mechanism of activation by enhancement of the Jundp2 promoter. Each of these lymphomas showed overexpression of Jundp2 mRNA (data not shown). Thus, our studies revealed that insertions within each of the three clusters (A, B, and C) led to overexpression of Jundp2 mRNA.

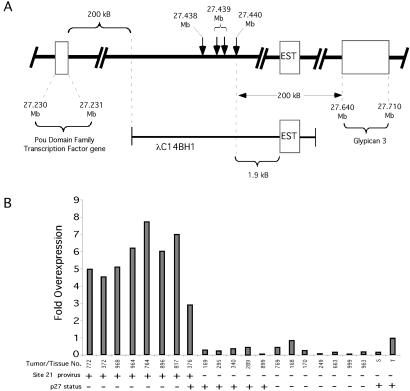

Site 21 Represents a Tightly Clustered X-Linked CIS That Is Enriched in p27−/− Lymphomas.

Site 21 was isolated from 4 p27−/− lymphomas (three panel one lymphomas and one panel two lymphoma) (Table 2). All of these insertions fell within 3 kb of one another. Because such tight clustering is usually indicative of a nearby protooncogene, we analyzed site 21 in more detail.

By using a site 21-specific probe, we detected rearrangements in 28% (7/25) of the panel one p27−/− lymphomas versus 4% (1/25) of the panel one p27+/+ lymphomas (Table 1). The difference in frequency of involvement between the p27−/− and p27+/+ lymphomas was statistically significant (P = 0.022), suggesting that this locus cooperates with p27 loss.

We used the Celera database to assemble a genomic map of the site 21 insertion region (Fig. 3A). This region falls within the mouse X chromosome and is highly syntenic with human Xq26. No known oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes have been mapped in this region. The positions of the four insertions that were sequenced are indicated. These insertions fell in a region relatively underrepresented by known genes. However, there are gaps remaining in the Celera sequence. The nearest known gene is Gpc3, which falls ≈200 kb 3′ to the insertion cluster. There is also a hypothetical POU domain transcription factor gene ≈200 kb 5′ of the insertion cluster. However, there does not appear to be a human X-chromosomal homologue of this predicted gene, and its functional status is unknown.

Fig 3.

Xpcl1 is a CIS in p27−/− lymphomas and linked to a novel thymic EST. (A) Genomic map of the Xpcl1 locus and closest Celera annotated genes. The relative position of the Xpcl1 genomic clone and the sequences identical to the mouse AI464896 EST are shown (EST; see text). (B) Overexpression of mRNA homologous to the AI464896 EST as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. S, spleen; T, thymus.

Because this region of the X chromosome is incompletely sequenced, we obtained an ≈20-kb DNA fragment covering this locus from a mouse genomic library. A region of this clone was found to contain a sequence identical to a 505-bp expressed sequence tag (National Center for Biotechnology Information accession no. AI464896) derived from a mouse thymus library (Fig. 3A). Quantitative PCR showed that all panel one lymphomas with this insertion site contained elevated levels of the AI464896 transcript, demonstrating that the viral insertions activated AI464896 expression (Fig. 3B). However, AI464896 does not contain an ORF. Three possible explanations are: (i) this insertionally activated EST may function as a noncoding RNA; (ii) this transcript may not be the true target of the insertion cluster; or (iii) it may represent only a partial cDNA. We have designated this locus Xpcl1 (X-linked p27-complementing locus 1) until the insertional target within this region is unambiguously identified.

Discussion

We used proviral tagging in p27−/− mice to identify protooncogenes that cooperate with p27 loss during multistep lymphomagenesis. By screening insertion site sequences from two distinct panels of M-MuLV-induced lymphomas in p27−/− mice against the Celera and public mouse genome databases, we were able to identify a larger number of CIS than were found in each panel individually. Several of these common sites appear to be novel and enriched in p27−/− versus p27+/+ lymphomas. These sites likely harbor genes that on gain or loss of function collaborate with p27 loss.

Multiple studies have suggested that the ability of Myc to abrogate p27 function is a critical mechanism involved with Myc-induced transformation (26–29). We were thus surprised to find not only that Myc activations occur in p27−/− lymphomas, but they were found more frequently in the p27−/− group. This strong selection for Myc insertional activation in lymphomas lacking p27 indicates that p27 “override” is not the primary mechanism of Myc function in lymphomagenesis. In agreement with this result, Martins and Berns have studied in detail the synergy between Myc activation and p27 loss and found strong cooperation between these two events in T and B cell transgenic Myc models in addition to M-MuLV-induced lymphomas (18). Thus the cooperation between Myc and p27 loss is not unique to M-MuLV-induced lymphomagenesis, but rather is a common feature of p27-associated lymphomas and perhaps other cancers.

We have identified Jundp2 as a target for insertional activation in lymphomas. Although insertions within Jundp2 are enriched in p27−/− lymphomas, Jundp2 activations are not restricted to this group of lymphomas. Several lines of evidence support the identification of Jundp2 as the target gene of the insertions within this region of chromosome 12: (i) most insertions fell directly within Jundp2; (ii) Jundp2-associated insertions were associated with overexpressed Jundp2 mRNA; and (iii) expression of the nearby Fos gene was unaffected. Many of the integrations caused truncation of the Jundp2 protein, although in those cases the b-zip region of the protein was left intact. It is possible that these tumor-specific truncated Jundp2 alleles are selected because they are more potent transforming proteins. However, the fact that many of the lymphomas contained insertions that leave the Jundp2 coding sequence intact indicates that truncation is not required for the oncogenic activity of Jundp2. We found one tumor (772, Fig. 2B) with elevated Jundp2 expression but without a Jundp2-associated provirus. In this case, it is likely that either a Jundp2-associated provirus was outside of the region encompassed by the Southern analysis presented in Fig. 2 (e.g., in cluster C) or it is also possible that Jundp2 expression was elevated in this lymphoma by a mechanism other then insertional activation.

Karin and coworkers have reported that Jundp2 expression is induced by UV-C irradiation, and that Jundp2 represses p53 transcription by binding to an atypical AP-1 site in the p53 promoter (25). It is thus tempting to speculate that insertionally activated Jundp2 promotes lymphomagenesis by disabling p53. However, we have no data that directly support this idea. We examined p53 expression in panel one p27−/− lymphomas and were unable to detect p53 protein in those tumors, so we could not determine whether p53 abundance was affected by Jundp2 overexpression (data not shown). We also overexpressed Jundp2 in primary p27+/+ or p27−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts and did not observe phenotypes suggestive of p53 loss, including the ability to form colonies and insensitivity to Myc-induced apoptosis (H.C.H. and B.E.C., unpublished results). Thus the mechanism through which Jundp2 promotes tumorigenesis remains unknown.

Xpcl1 is an X-linked locus that we found to be enriched in p27−/− lymphomas. Integrations within this locus are tightly clustered, strongly suggesting a common target gene. We have identified a candidate transcript corresponding to a mouse EST sequence that is encoded near the insertion sites and overexpressed in all lymphomas containing Xpcl1 insertions. There is significant sequence conservation between the murine Xpcl1 locus and the syntenic human Xq26 region, and sequences homologous to AI464896 and the cloned insertion sites are present in the human Xq26 region (data not shown). However, expressed human transcripts homologous to AI464896 have not been reported in sequence databases. Because Xpcl1 is located within the X chromosome, it is also possible that these insertions could inactivate a tumor suppressor gene in a single step. However, there are no data currently to support the idea that a tumor suppressor resides within the Xpcl1 locus.

The availability of the completed mouse genome has greatly facilitated the process of cancer gene discovery by insertional mutagenesis. The power of this technique is demonstrated by the large number of previously unrecognized CIS found within the p27−/− lymphomas. We arbitrarily defined a region as a putative CIS if two or more independent insertions occurred within a ≈100-kb span of DNA. This restriction may omit true CIS that activate a common target gene over greater distances or falsely include clustered insertions that occurred randomly. This analysis also revealed that a surprisingly high percentage of integrations fell within CIS that included both well-characterized and novel loci. Two distinct mouse genome databases are now available: the Celera and the public databases. As shown in Table 2, the data that we have obtained from these two resources have been quite similar thus far. However, as these databases improve in both coverage and annotation, it is likely that each may have unique advantages for analyzing large sets of insertion site data.

Although the frequency with which sites were sequenced largely reflected the frequency of involvement detected by Southern blotting, this was not always the case. For example, the Pim1 locus was a common target in p27−/− tumors (Table 1) but was found only twice among the 277 sequence tags (Table 3). The likelihood of identifying specific insertion sites by the PCR methods we used in this study may thus be influenced by other factors such as the presence of repetitive sequences, restriction site location, etc. Therefore, some CIS may be underrepresented in the collection of insertion site sequences. Using multiple techniques to obtain insertion sites, such as the two methods we describe, may increase the total number of CIS identified by overcoming technical barriers associated with any single method.

We have compared the frequency of site involvement that we observed in p27−/− mice with the utilization of insertion sites observed in related screens in different genetic backgrounds. This series includes approximately 2,000 cloned insertion sites from M-MuLV-induced lymphomas from BXH2, AKXD, Eμ-Myc; Pim1−/−; Pim-2−/−, and Cdkn2a−/− mouse strains (18, 30, 31). The sites that we identified corresponding to previously known insertion sites (Table 2, sites 1–7) were also found frequently in these other screens (e.g., Myc, Gfi1, and Rasgrp1). Several of the novel loci that we have described in Table 2 (sites 8–21) were also cloned frequently in these screens, indicating that they are not likely to be specifically enriched in the p27−/− background (e.g., site 13, SH3 domain protein). In contrast, other CIS that we have identified were found only rarely or not at all in these other genetic backgrounds, further supporting the idea that they are specifically selected for in the p27−/− background. Clones corresponding to Jundp2 and Xpcl1 loci were each found only once among the 2,000 sites. Similarly, several other sites listed in Table 2 were found only once or not at all in the larger insertion site collection (sites 8, 10–12, 15, 16, 19, and 20; Table 2). Each of these loci thus represents a potential oncogene that collaborates with p27 loss in lymphomagenesis. However, as the activated genes within these loci are identified, their activity in the setting of p27 loss must be individually tested.

Finally, although we have focused on CIS that are enriched in p27-null lymphomas as being the most likely genes that cooperate with p27 loss, it is important to realize that CIS found in other backgrounds, as well as p27-null lymphomas, may also cooperate with p27 loss. Perhaps in these other genetic backgrounds, it is the p27 pathway that has been mutated. Thus by comparing the CIS involved in diverse genetic backgrounds, a defined set of common pathways may be revealed that are involved in the genesis of a large number of cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dusty Miller (FHCRC) for providing M-MuLV reagents and expertise and James Roberts (FHCRC) for advice and support. We also thank Ami Aronheim for providing Jundp2 antibody. B.E.C. is a W. M. Keck Distinguished Young Scholar in Medical Research. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA84069 (B.E.C.) and Department of Defense Grant DAMD17-98-1-8308 (B.E.C.), National Institutes of Health Training Grant CA80416-05 (H.C.H.), and the Praxis XXI and Gulbenkian Foundations (C.P.M.). H.C.H is an E. Donnall Thomas Scholar of the Jose Carreras Foundation.

Abbreviations

CIS, common insertion sites

M-MuLV, Moloney murine leukemia virus

FHCRC, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

I-PCR, inverse PCR

EST, expressed sequence tag

LTR, long-terminal repeat

References

- 1.Sherr C. J. (1996) Science 274, 1672-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherr C. J. & Roberts, J. M. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1501-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clurman B. E. & Porter, P. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15158-15160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd R. V., Erickson, L. A., Jin, L., Kulig, E., Qian, X., Cheville, J. C. & Scheithauer, B. W. (1999) Am. J. Pathol. 154, 313-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slingerland J. & Pagano, M. (2000) J. Cell Physiol. 183, 10-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponce-Castaneda M. V., Lee, M. H., Latres, E., Polyak, K., Lacombe, L., Montgomery, K., Mathew, S., Krauter, K., Sheinfeld, J., Massague, J., et al. (1995) Cancer Res. 55, 1211-1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiyokawa H., Kineman, R. D., Manova-Todorova, K. O., Soares, V. C., Hoffman, E. S., Ono, M., Khanam, D., Hayday, A. C., Frohman, L. A. & Koff, A. (1996) Cell 85, 721-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakayama K., Ishida, N., Shirane, M., Inomata, A., Inoue, T., Shishido, N., Horii, I. & Loh, D. Y. (1996) Cell 85, 707-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fero M. L., Rivkin, M., Tasch, M., Porter, P., Carow, C. E., Firpo, E., Polyak, K., Tsai, L. H., Broudy, V., Perlmutter, R. M., et al. (1996) Cell 85, 733-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donehower L. A., Harvey, M., Slagle, B. L., McArthur, M. J., Montgomery, C. A., Jr., Butel, J. S. & Bradley, A. (1992) Nature (London) 356, 215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano M., Lee, H., Chin, L., Cordon-Cardo, C., Beach, D. & DePinho, R. A. (1996) Cell 85, 27-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fero M. L., Randel, E., Gurley, K. E., Roberts, J. M. & Kemp, C. J. (1998) Nature (London) 396, 177-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Cristofano A., De Acetis, M., Koff, A., Cordon-Cardo, C. & Pandolfi, P. P. (2001) Nat. Genet. 27, 222-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonkers J. & Berns, A. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1287, 29-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Shen, H., Himmel, K. L., Dupuy, A. J., Largaespada, D. A., Nakamura, T., Shaughnessy, J. D., Jr., Jenkins, N. A. & Copeland, N. G. (1999) Nat. Genet. 23, 348-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Lohuizen M., Verbeek, S., Scheijen, B., Wientjens, E., van der Gulden, H. & Berns, A. (1991) Cell 65, 737-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheijen B., Jonkers, J., Acton, D. & Berns, A. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins, C. P. & Berns, A. (2002) EMBO J. 21, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mikkers, H., Allen, J., Knipscheer, P., Romeyn, L., Vink, E. & Berns, A. (2002) Nat. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Yanagawa S., Lee, J. S., Kakimi, K., Matsuda, Y., Honjo, T. & Ishimoto, A. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 9786-9791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen-Ong G. L., Potter, M., Mushinski, J. F., Lavu, S. & Reddy, E. P. (1984) Science 226, 1077-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran L. M., Adams, J. M., Dunn, A. R. & Cory, S. (1984) Cell 37, 113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Lohuizen M., Breuer, M. & Berns, A. (1989) EMBO J. 8, 133-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronheim A., Zandi, E., Hennemann, H., Elledge, S. J. & Karin, M. (1997) Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 3094-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piu F., Aronheim, A., Katz, S. & Karin, M. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 3012-3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouchard C., Thieke, K., Maier, A., Saffrich, R., Hanley-Hyde, J., Ansorge, W., Reed, S., Sicinski, P., Bartek, J. & Eilers, M. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5321-5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Roger I., Kim, S. H., Griffiths, B., Sewing, A. & Land, H. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5310-5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Hagan R. C., Ohh, M., David, G., de Alboran, I. M., Alt, F. W., Kaelin, W. G., Jr. & DePinho, R. A. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2185-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W., Shen, J., Wu, M., Arsura, M., FitzGerald, M., Suldan, Z., Kim, D. W., Hofmann, C. S., Pianetti, S., Romieu-Mourez, R., et al. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1688-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki, T., Shen, H., Akagi, K., Morse, H. C., Jenkins, N. A. & Copeland, N. G. (2002) Nat. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Lund, A. H., Turner, G., Trubetskoy, A., Verhoeven, E., Wientjens, E., Hulsman, D., Russell, R., DePinho, R. A., Lenz, J. & van Lohuizen, M. (2002) Nat. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.