ABSTRACT

Tailored anesthetic management is crucial for pediatric patients with inborn metabolic disorders like CPT‐1 deficiency and conditions, such as viral myositis. Avoiding inhalational anesthetics and succinylcholine, using glucose infusion, safe anesthetics, and appropriate monitoring are essential to prevent metabolic crises and malignant hyperthermia during surgery, ensuring patient safety.

Keywords: lipid metabolism disorders, malignant hyperthermia, pediatric anesthesia, viral myositis

1. Introduction

Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT‐1) deficiency is a disorder of long‐chain fatty acid oxidation, with an incidence of 1:750,000 to 1:2,000,000 live births based on newborn screening (NBS) programs [1]. More specifically, of the three known isoforms of CPT‐1, CPT‐1A is the only one associated with genetic disease in humans and is expressed in the liver, kidney, lymphocytes, and skin fibroblasts [2]. This disease is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and is not known to result from a de novo mutation. Both parents of an affected child are typically asymptomatic carriers who each possess and pass down one mutated allele [2]. As CPT‐1 plays a vital role in fatty acid processing, beta oxidation is impaired in patients deficient in the enzyme, leaving them at high risk for rhabdomyolysis and hypoketotic hypoglycemia during periods of fasting. In this report, we present a case of a 13‐year‐old male with a history of viral myositis and findings on newborn screening (NBS) indicative of abnormal CPT‐1 enzyme who underwent an emergent scrotal exploration and testicular detorsion for traumatic left testicular torsion. Due to the lack of published guidance on anesthetic management in such overlapping conditions, we will use this report to discuss the challenges, anesthetic management considerations, and precautionary measures that were taken in this case while also highlighting the importance of recognizing red flags in metabolic history in the context of emergent cases.

2. Case History, Examination, and Diagnosis

A 13‐year‐old male patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of left scrotal pain and swelling 1 h after being hit in the lower abdomen by a football. He had a past medical history of viral myositis, autism, and asthma. He also had findings on NBS indicative of an abnormal CPT‐1 enzyme. A detailed clinical history and physical examination with ultrasound were consistent with left testicular torsion, and the patient was scheduled for an emergent scrotal exploration and testicular detorsion under general anesthesia.

3. Management

After flushing the anesthesia machine thoroughly, all the necessary anesthetic precautions were taken by avoiding inhalational anesthetics and succinylcholine. The CO2 absorbent was changed, and induction was achieved with 16 mg of etomidate and 20 mg of rocuronium. Maintenance was achieved with a total of 33.17mcg dexmedetomidine. Additionally, 0.3 mg of glycopyrrolate was used to reduce secretions. The patient was administered a total of 400 mL of 5% dextrose infusion throughout the procedure to prevent fasting‐induced hypoketotic hypoglycemia and rhabdomyolysis. 1.5 mg of neostigmine was used to reverse the neuromuscular blocking agent. After the surgery, the patient emerged from anesthesia, was extubated, and was transferred to the recovery room in stable condition.

4. Outcomes and Follow‐Up

The patient was seen approximately 2 weeks after the surgery for follow‐up with a pediatric urologist, who noted that he was healing well with no signs of side effects attributable to his intraoperative anesthetic regimen.

5. Discussion

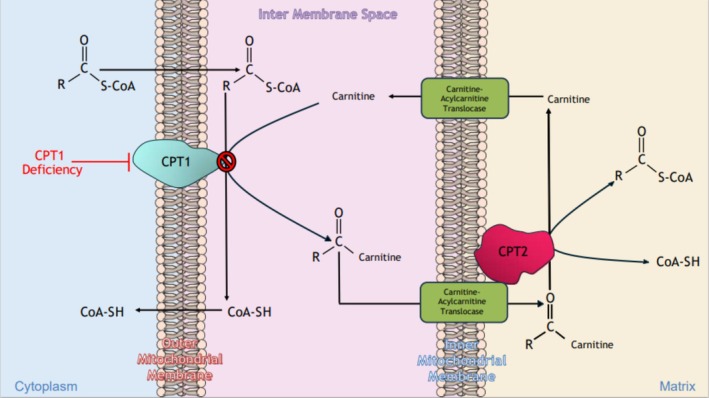

CPT‐1 deficiency is a disorder of long‐chain fatty acid (LCFA) oxidation, where the enzyme defect impairs the body's ability to metabolize fatty acids for energy. Normally, LCFAs are activated to acyl‐CoA by acyl‐CoA synthetases and then transported into the inner mitochondria via a carnitine‐dependent shuttle. This transportation involves the conversion of the acyl‐CoA to fatty acyl‐carnitines by CPT‐1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane. These fatty acyl‐carnitines are then translocated across the inner mitochondrial membrane and subsequently converted back into fatty acyl‐CoAs by CPT‐2 [3]. These acyl‐CoAs can then undergo β‐oxidation, generating NADH, Acetyl‐CoA, and FADH2, which fuel the TCA cycle and electron transport chain for ATP production (Figure 1). However, a defect in CPT‐1 prevents the formation of acyl‐carnitines, blocking LCFAs from entering the mitochondria. During periods of stress or fasting, impaired fatty acid oxidation forces reliance on glucose and glycogen stores. Once these are depleted, the patient becomes susceptible to hypoketotic hypoglycemia and rhabdomyolysis [2]. Therefore, due to the patient's inability to metabolize LCFAs and the body's reliance on glucose and hepatic glycogen stores, it was crucial that the patient remained metabolically “fed” throughout the procedure to avoid a metabolic crisis. This approach was imperative not only to prevent severe hypoglycemia but also to avoid proteolysis, which can occur when glycogen stores and fatty acid metabolism are impaired, and the demand for gluconeogenic precursors, such as amino acids, increases [4]. For this patient, it was critical to administer intravenous glucose during surgery to maintain stable energy levels and prevent these complications, as done in our case with a 400 mL 5% dextrose infusion throughout the procedure. Although CPT‐1 deficiency is rare, it carries significant anesthetic implications, especially in emergent surgical settings where there is limited time for metabolic optimization.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the carnitine shuttle system in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation.CPT‐1 deficiency blocks conversion of acyl‐CoA to acylcarnitine, preventing fatty acid entry into mitochondria.

The patient's history of viral myositis is also an important consideration in anesthetic management. Myositis encompasses a group of disorders characterized by skeletal muscle inflammation and subsequent muscle weakness. Viral myositis, specifically, first described in the 1950s as “myalgias cruris epidemica,” is a benign and self‐limiting phenomenon that falls under this umbrella. It is often associated with influenza viruses in school‐age children and is characterized by lower limb pain, walking difficulties, fever, and elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) [5, 6, 7]. Although the exact mechanism of cellular injury due to acquired inflammatory myopathies is still unknown, both CD8+ T‐cell invasion and expression of major histocompatibility complex class I and II antigen on the sarcolemma have been described in muscle biopsies of patients with acute viral myositis [8, 9]. It is believed that this direct viral invasion of muscle fibers and subsequent immune activation could potentially compromise the integrity of the sarcolemma, make muscle cells more vulnerable to abnormal calcium fluxes, disrupt normal calcium regulation in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and in our patient's case, increase the risk of malignant hyperthermia (MH).

MH is a hypermetabolic condition that can be triggered by certain anesthetic agents, such as inhalational anesthetics and succinylcholine [10]. In select cases, patients at risk for MH may undergo genetic testing or in vitro contracture testing (IVCT), which use skeletal muscle biopsies to help quantify a patient's risk for MH [11]. But given the urgent nature of this patient's case, these tests were unable to be performed prior to the operation. Nonetheless, the patient's metabolic and neuromuscular conditions increased the risk of this potentially fatal reaction. Thus, inhalational anesthetics and succinylcholine were avoided during the procedure, and the anesthesia plan was carefully tailored to minimize any triggers for MH. This approach reflects current guidelines for managing patients with known or suspected risk factors for MH.

Another notable consideration for this patient was that propofol, a widely used, lipid‐based anesthetic, requires functional fatty acid metabolism to be cleared properly from the body. In a patient with a fatty acid oxidation disorder, propofol needs to be avoided and substituted with a more suitable, non‐lipid‐based agent to prevent complications. In this case, anesthesia was induced using etomidate and rocuronium, which are considered safe in patients with metabolic disorders, such as CPT‐1 deficiency and viral myositis. The neuromuscular blocking agent rocuronium was used, as it is generally safer than succinylcholine, which is known to increase the risk of MH. Dexmedetomidine was used for maintenance, providing sedation without the risk of triggering MH. To eliminate potential MH triggers, the anesthesia machine was thoroughly flushed to remove any residual inhalational agents, and the CO2 absorbent was changed to ensure a safe environment free of potentially triggering substances. These precautions were critical in preventing adverse outcomes and ensuring the patient's safety during the procedure.

6. Conclusion

This case highlights the anesthetic challenges posed by the intersection of rare metabolic and neuromuscular disorders in urgent pediatric surgery. The patient's history of CPT‐1 deficiency and viral myositis served as critical flags, underscoring the importance of thorough chart review and preoperative risk assessment, particularly in emergency settings. Anesthetic management requires careful agent selection, preoperative machine preparation, and intraoperative metabolic support. While the precise viral etiology of this patient's myositis was unknown, the anesthesia team elected to err on the side of caution given the shared features of muscle injury in viral myositis and the pathophysiology of MH, which contributed to a safe outcome. Further research into the cellular mechanisms of acute viral myositis in patients with pediatrics, particularly regarding SR dysfunction and calcium homeostasis, may help guide anesthetic decision‐making in future emergency settings. Overall, this case illustrates the need for heightened vigilance when caring for patients with medically complex pediatric patients and supports the development of decision‐support tools that incorporate red flag indicators for metabolic disease and increased MH susceptibility.

Author Contributions

Samuel Grant Volpe: conceptualization, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Aariya Srinivasan: conceptualization, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Sabry Ayad: conceptualization, supervision, visualization, writing – review and editing.

Consent

Written informed consent was acquired from the patient whose case details are written in the study to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Volpe S. G., Srinivasan A., and Ayad S., ““Testicular Torsion in a Child With CPT‐1 Deficiency and History of Viral Myositis: Anesthesia Considerations”,” Clinical Case Reports 13, no. 8 (2025): e70766, 10.1002/ccr3.70766.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this report's findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Lindner M., Hoffmann G. F., and Matern D., “Newborn Screening for Disorders of Fatty‐Acid Oxidation: Experience and Recommendations From an Expert Meeting,” Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 33, no. 5 (2010): 521–526, 10.1007/s10545-010-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee K., Pritchard A., and Ahmad A., “Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A Deficiency,” in GeneReviews, ed. Adam M. P., Feldman J., Mirzaa G. M., Pagon R. A., Wallace S. E., and Amemiya A. (University of Washington, Seattle, 2005), 1993–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adeva‐Andany M. M., Carneiro‐Freire N., Seco‐Filgueira M., Fernández‐Fernández C., and Mouriño‐Bayolo D., “Mitochondrial β‐Oxidation of Saturated Fatty Acids in Humans,” Mitochondrion 46 (2019): 73–90, 10.1016/j.mito.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonnefont J. P., Demaugre F., Prip‐Buus C., et al., “Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase Deficiencies,” Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 68, no. 4 (1999): 424–440, 10.1006/mgme.1999.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arrab R., Benchehab Y., Alaammari I., and Dini N., “Benign Acute Myositis in Children: A Case Series,” Cureus 16, no. 11 (2024): e73303, 10.7759/cureus.73303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Majava E., Renko M., and Kuitunen I., “Benign Acute Childhood Myositis: A Scoping Review of Clinical Presentation and Viral Etiology,” European Journal of Pediatrics 183, no. 11 (2024): 4641–4647, 10.1007/s00431-024-05786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crum‐Cianflone N. F., “Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral Myositis,” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21, no. 3 (2008): 473–494, 10.1128/CMR.00001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pancheri E., Lanzafame M., Zamò A., et al., “Benign Acute Viral Myositis in African Migrants: A Clinical, Serological, and Pathological Study,” Muscle & Nerve 60, no. 5 (2019): 586–590, 10.1002/mus.26679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aschman T., Schneider J., Greuel S., et al., “Association Between SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection and Immune‐Mediated Myopathy in Patients Who Have Died,” JAMA Neurology 78, no. 8 (2021): 948–960, 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenberg H., Pollock N., Schiemann A., Bulger T., and Stowell K., “Malignant Hyperthermia: A Review,” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 10 (2015): 93, 10.1186/s13023-015-0310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang L., Motley R., Daly C. L., Diggle C. P., Hopkins P. M., and Shaw M. A., “An Association Between OXPHOS‐Related Gene Expression and Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptibility in Human Skeletal Muscle Biopsies,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 6 (2024): 3489, 10.3390/ijms25063489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this report's findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.