Abstract

Phage Mu DNA transposes to duplex target DNA sites with limited sequence specificity. Here we demonstrate that Mu transposition exhibits a strong target site preference for all single-nucleotide mismatches. This finding has implications for the mechanism of transposition and provides a powerful tool for genomic research. A single mismatch could be detected as a preferred target of Mu transposition in the presence of 300,000-fold excess of nonmismatched sites. We demonstrate the detection of both heterozygous and homozygous mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene and single nucleotide polymorphism in HLA region by Mu transposition mismatch analysis procedure.

Transposons are genetic elements that move from one location in the genome to another. The transposition process involves DNA cleavage at the 3′-ends of the transposon followed by the rejoining of the 3′-OH termini to a new target DNA site (1). These steps are catalyzed by the element-specific transposase proteins. Phage Mu propagates by replicative transposition that is catalyzed by the MuA transposase. Although this reaction is physiologically controlled by a number of regulatory cofactors, the DNA cleavage and joining reactions can be promoted in vitro, by the transposase protein and a DNA fragment with the right end sequence of Mu genome (2–4). Mu can transpose to essentially any DNA sequence. Here we report that Mu displays a dramatic preference for insertion into mismatched DNA sites. This unexpected finding has mechanistic implications for the mode of target DNA recognition by transposons and can be used as a tool for genomic research and diagnostics. It can be used as a tool for detection and mapping of mismatched DNA sites, hence genetic mutations, in the presence of a large excess of nonspecific DNA. As examples, we demonstrate here the application of this finding to the detection of a mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that is responsible for cystic fibrosis (CF), one of the most common genetic diseases, and a polymorphism in the HLA region. The advantages of the Mu transposition mismatch analysis procedure (Mut-Map) will be discussed.

Materials and Methods

Proteins and DNA.

MuA 77–663 was purified essentially as described (5). λ DNA was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). RsaI was from New England Biolabs. λ DNA digested by RsaI was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and was resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) buffer. The oligonucleotides were synthesized at Howard Hughes Medical Institute/Keck Oligonucleotide Synthesis Facility (Yale University) and purified by electrophoresis on a urea-polyacrylamide gel (6). When indicated, oligo DNA was labeled on the 5′-end with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Pharmacia) and [γ-32P]ATP (New England Nuclear). The Mu end DNA fragment was prepared by annealing the two oligonucleotides, MM1138 (5′-TCGGATGAAGCGGCGCACGAAAAACGCGAAAGCGTTTCACGATAAATGCGAAAACA-3′) and MM1141 (5′-TGTTTTCGCATTTATCGTGAAACGCTTTCGCGTTTTTCGTGCGCCGCTTCA-3′). The regular target DNA fragment was prepared by annealing the two oligonucleotides, MM1063 (5′-CGTTCATTAGCACAATCACAGAAGACTAGAATACAACCGCACATAAGATCAGAAGTTAACTAGCACTAGTACTTGC-3′) and MM1064 (5′-GCAAGTACTAGTGCTAGTTAACTTCTGATCTTATGTGCGGTTGTATTCTAGTCTTCTGTGATTGTGCTAATGAACG-3′). The heteroduplex target DNA fragments have the same sequence as the homoduplex target DNA except for the mismatched nucleotides, which are shown in the figures. Human DNA samples were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). The patient DNA was NA11496, the sibling DNA was NA11497, and the normal DNA was NA14511. The primers for amplifying the CFTR gene were MM1482 (5′-TGGTAATAGGACATCTCCAAG-3′) and MM1483 (5′-ACCTTGCTAAAGAAATTCTTGC-3′). The child's DNA was NA14689, the mother's DNA was NA14690, and the father's DNA was NA14691. The primers for amplifying the DPα gene were MM1461 (5′- CGCGGATCCTGTGTCAACTTATGCCGC-3′) and MM1462 (5′- GTGGCTGCAGTGTGGTTGGAACGC-3′). The PCR reaction was performed by using 0.3 μg of DNA, 0.4 μM primers, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 2.5 units of PfuTurbo hotstart DNA polymerase (Stratagene) per 50 μl of reaction. The PCR was run for 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min in a Perkin–Elmer Gene Amp system 9700. The amplified DNA was purified by a spin column (QIAquick PCR purification kit, Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). The concentration of the amplified DNA were ≈200 ng/μl. The 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and DMSO were from Sigma.

Transposition Reactions.

The reactions (15 μl) for Fig. 1 contained a 150 nM Mu end DNA fragment, a 75 nM target DNA fragment, 400 nM MuA77–663, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, 15% DMSO, 10 mM CHAPS, 10 mM MgCl2, and 156 mM NaCl. The reactions (10 μl) for Figs. 2 and 3 contained 100 nM Mu DNA fragment, 100 nM target DNA fragment for Fig. 2, or specified amount of target DNA fragment (see Fig. 3 legend), 350 nM MuA77–663, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, 10% DMSO, 10 mM CHAPS, 10 mM MgCl2, and 280 mM NaCl. Reactions were carried out at 30°C for 30 min. For the experiments in Figs. 4 and 5, transpososomes were preformed in reaction mixture containing 100 nM labeled Mu DNA fragment, 400 nM MuA77–663, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, 15% DMSO, 10 mM CHAPS, and 156 mM NaCl. Reactions were carried out at 30°C for 30 min. Then the reaction mixture was split into aliquots and the target DNA and MgCl2 was added. The final reaction mixture contained 20 nM labeled Mu DNA fragment, 1.3 μl of the amplified DNA (≈260 ng) as a target DNA, 80 nM MuA77–663, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, 10% DMSO, 10 mM CHAPS, 10 mM MgCl2, and 300 mM NaCl. Reactions were carried out at 30°C for 5 min.

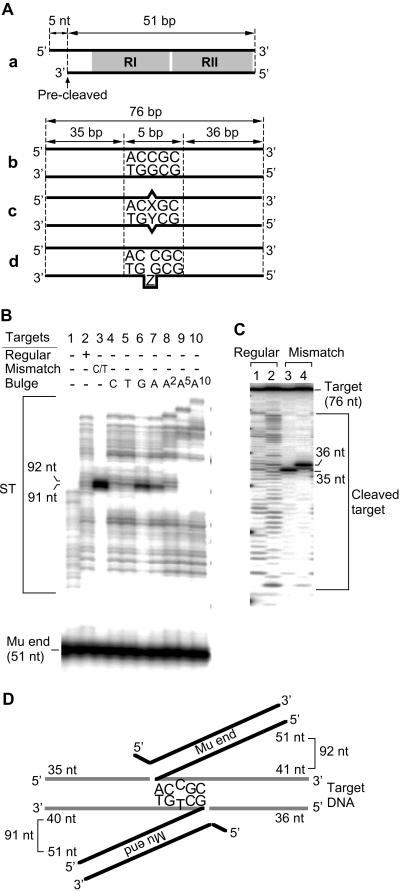

Fig 1.

ST with the mismatch target DNA. (Aa) The Mu end DNA fragment contained the first 51 bp of the Mu R end sequence, including the RI and RII MuA-binding sites (shaded). This substrate DNA is “precleaved” and is capable of undergoing ST without further processing. (Ab) The standard target DNA fragment (76 bp). (Ac) The mismatch target DNA fragment, identical to b except for mismatch bases (X and Y). (Ad) The bulge target DNA fragment, identical to b except for bulged bases (Z). (B) Effect of mismatch or bulge in the target DNA on the ST products. The Mu end DNA fragment was labeled at the 5′-end of the strand to be transferred. Two dominant bands in lane 3 correspond to 91 and 92 nt. (C) The location of the target cleavage site on the mismatch containing DNA. Reactions were carried out with regular (lanes 1 and 2) or mismatch target DNA (lanes 3 and 4) labeled at either the 5′-end of top (lanes 1 and 3) or bottom strand (lanes 2 and 4). The predominant bands in lanes 3 and 4 correspond to 35 and 36 nt, respectively. (D) Schematic ST product with mismatch bases centered in the 5-bp targeted sequence. The Mu end DNA is shown as dark lines and target DNA as gray lines.

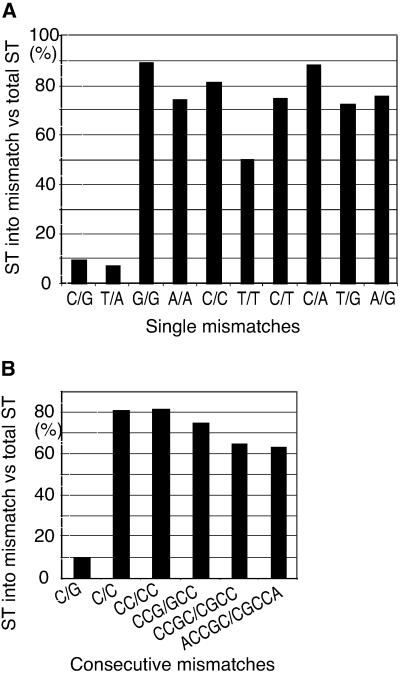

Fig 2.

Efficiency of various mismatch targets. (A) Percentage of the radioactive intensity for the mismatch-targeted products to total radioactive intensity of ST products (60–120 nt). (B) Percentage of the ST products targeted to consecutive mismatches. Consecutive mismatches were made by changing adjacent bases in the bottom strand to the same base as on the top strand.

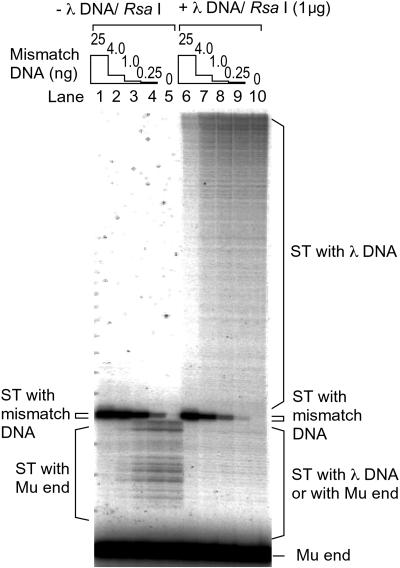

Fig 3.

Detection of mismatch DNA in the presence of a large excess of nonmismatch DNA. Target DNA was titrated from 25 to 0.25 ng in the absence or presence of 1 μg of λ DNA digested by RsaI.

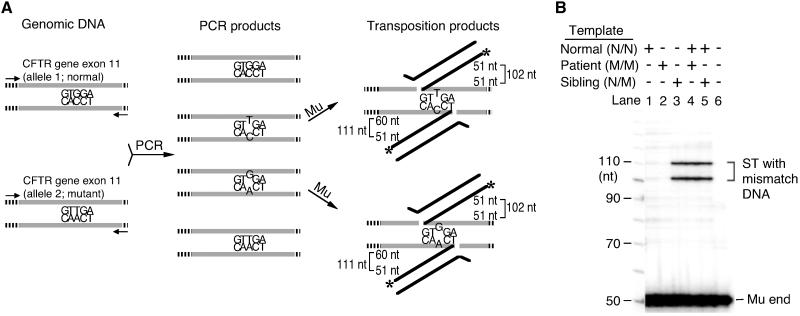

Fig 4.

Detection of homozygous and heterozygous mutations in the CFTR gene by Mut-Map. (A) Schematic diagram of mutation detection in the CFTR gene. The human genome harbors two alleles of CFTR gene. The normal CFTR gene has a GGA codon, which codes G542 (Left). The DNA from the patient we used has a homozygous nonsense mutation (M/M, GGA to TGA) at this locus. The DNA from the sibling of the patient has a heterozygous mutation (N/M) at the same position. When the DNA with the heterozygous mutation is used as a template for PCR, the PCR product will have two kinds of mismatch DNA after the amplification reaches a plateau (Center). For the detection of the homozygous mutation, PCR by using the patient DNA (M/M) mixed with normal DNA (N/N) as a template will produce the mismatch DNA. Those mismatch DNAs will be targeted by Mu to generate 102- and 111-nt ST products (Right). Gray lines are exon 11. Zebra lines are adjacent introns. Black lines are Mu end DNA. Small arrows are primers for PCR. Asterisks are labeled positions. (B) Autoradiograph of transposition reaction products with the CFTR gene as the target. The template DNA used for PCR are indicated at the top.

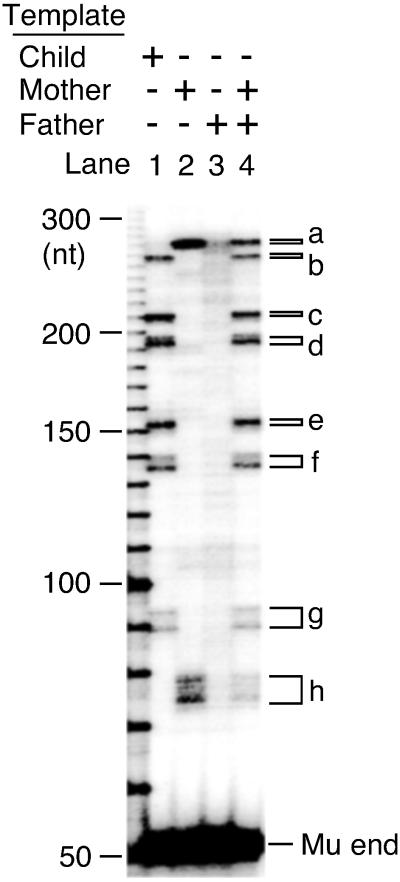

Fig 5.

Detection of a polymorphism in HLA region by Mu transposition mismatch analysis procedure. DPα gene in HLA region was amplified and the preferred transposition sites were compared among the family members. The template DNA used for PCR are indicated at the top. Distinct ST products (a–h).

The reaction products were recovered by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Approximately one-tenth of recovered DNA was used for analysis by 6% urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (6). The radioactivity was visualized by autoradiography by using a Fuji BAS 2000 PhosphorImager. Quantification of the bands was performed by using IMAGE GAUGE V3.0 (Fuji).

Results

Mu Targets Mismatch DNA.

We examined the effects of DNA distortion on Mu transposition target recognition by testing the ability of short DNA fragments that contained mismatch base pairs to function as transposition targets. We used the simplified in vitro reaction conditions with a precleaved form of Mu end DNA fragment containing two transposase-binding sites. The Mu end DNA was labeled at the 5′-end of the 51-nucleotide precleaved strand that is to be joined to the target DNA (Fig. 1Aa). When 76-bp DNA without a mismatch (Fig. 1Ab) was used as the target, the length of the resulting recombinant fragments was randomly distributed from 68 to 115 bp (Fig. 1B, lane 2). This indicated that the Mu DNA was transferred to sites throughout the target DNA, except at the 5′-terminal 12 nt and 3′-terminal 17 nt. When the target DNA contained a mismatch, insertions to the normal duplex sites were suppressed and nearly 90% of the strand transfer (ST) products were either 91- or 92-nt long (Fig. 1B, lane 3). The observed size of the reaction products matched that of the two fragments that would result from Mu insertion with the mismatch located at the center of the 5-nt target sequence (see Fig. 1D). To confirm this, the target DNA was labeled at the 5′-end of either strand and the size of the resulting products was examined. When nonmismatch DNA was used, the size of the DNA fragment released by formation of the recombinant strand was distributed from 12 to 60 nt without strong preference (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 2). When mismatch DNA was used, this released product was mainly found at 35 nt when the top strand as drawn in Fig. 1Ac was labeled (Fig. 1C, lane 3) and 36 nt when the bottom strand was labeled (Fig. 1C, lane 4). Taken together, we conclude that the preferential ST to the mismatch-containing DNA occurred with the mismatch nucleotide at the center of the target sequence (Fig. 1D).

All eight types of mismatched base pairs were efficiently used as target (Fig. 2A). A T/T mismatch, which was somewhat less strongly preferred compared to others, was still highly preferred over nonmismatch sites. We also examined targets having multiple nucleotide mismatches (bubbles) up to 5 nt (Fig. 2B). Dinucleotide mismatches were used as well as single mismatches. Larger bubbles were also preferentially targeted; although the efficiency of targeting did not improve with the bubble size. The exact target locations were clustered around the bubble (data not shown). Not all unusual DNA structures were strongly preferred as a transposition target. When the target DNA contained a single-nucleotide bulge as opposed to a mismatch, the bulge sites were not used as preferred targets, except for a moderate preference for a G- or A-bulge site. Instead, a weak insertion preference approximately one helical turn away from the bulge resulted in the products of 80, 81, 102, and 103 nt (Fig. 1B, lanes 4–7). Larger bulge sites were not preferred (Fig. 1B, lanes 8–10).

Because Mu transposase specifically targets mismatched nucleotides during recombination in vitro, it may be useful for detection and mapping of mutations. To evaluate the usefulness of Mut-Map as a general mutation detection method, we needed to know the selectivity for a mismatched target site in the presence of a large excess of duplex target sites of heterogeneous sequence. To investigate the limit of detection of a mismatch site by selective Mu transposition, mismatched DNA target was titrated in the presence and absence of an excess amount of λ DNA as a nonmismatch random DNA. In the absence of the λ DNA, decreasing the amount of mismatch DNA caused an increase in use of the Mu end DNA itself as a target, although the products that used the mismatch site were still clearly detectable (Fig. 3, lanes 1–5). Addition of λ DNA caused only a modest decrease in the mismatch-targeted events (Fig. 3, lanes 6–10). Transposition to a mismatched site on a 76-nt fragment could be detected in the presence of a 300,000-fold excess of nonmismatch sites (Fig. 3, lane 9).

Detection of Genomic Variations by Mu Transposition.

Next we tested genomic DNA from a CF patient who has a homozygous mutation in CFTR gene and her sibling who has heterozygous mutation to see whether the mutation was detectable by Mut-Map. Exon 11 of the CFTR gene was amplified by PCR by using genomic DNA from a normal individual (N/N), the sibling (N/M), and the patient (M/M) as templates. Only when the sample DNA contained both the wild-type and mutant sequence, will mismatch DNA be generated by denaturing-annealing steps during PCR (Fig. 4A). When the normal or the patient DNA was amplified and used as the target, no dominant ST product was detected (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2). When the sibling DNA was used, the dominant ST products were found at the 102- and 111-nt positions (Fig. 4B, lane 3), revealing that, as expected, mismatch DNA was generated during PCR and that ST targeted this mismatch. When the amplified DNA from the mixture of normal and patient DNA was used, the dominant ST products were found at the same positions as expected (Fig. 4B, lane 4). Homozygous mutations can be distinguished from heterozygous mutations by the requirement for coamplification with the nonmutant sequence. Similar experiments by using a mutant k-ras gene demonstrated the general applicability of this method for polymorphism detection and mapping (data not shown).

To investigate the capability of detection of unknown mutations, the HLA region, which is known to be highly polymorphic, was tested. DPα, one of the genes in HLA region, was amplified and the preferred transposition sites were compared between the family members. Each family member (child, mother, and father) exhibited a distinct pattern, showing that they have different heterozygous polymorphisms in the DPα gene (Fig. 5, lanes 1–3). When DNA amplified from both mother's and father's DNA was used as the target, bands specific to the child (Fig. 5 a–g) were evident as well as bands specific to the mother (Fig. 5 a and h). This result shows that the preferable sites in child's DNA are actually mismatch sites that arise from multiallelic differences between the parents and that this method can reliably detect multiple mismatches simultaneously.

Discussion

Whatever the mechanism behind the preferential use of mismatch target sites for Mu transposition, the Mut-Map reported here offers a number of advantages over other existing methods for detecting single nucleotide mismatches in complex sequences. Methods that depend on mismatch selective DNA-binding proteins lack easy mapping capabilities. Methods based on conformation-dependent DNA electrophoretic mobility difference induced by small sequence changes, such as single-strand conformation polymorphism and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis are widely used (7, 8). They, however, are unable to show the location of mutations, and also DNA length limitations and the need for optimization for individual experiments make them cumbersome (9). Other methods that use chemicals or RNases as cleavage agents at heteroduplex sites either can detect only a subset of mutations, involve hazardous materials, or require multiple steps (10, 11). Another method, by using T4 endonuclease VII as heteroduplex-cleaving enzyme, has the possible advantage of simplicity (12, 13) but may not have the sensitivity of the method described here.

The Mut-Map is both simple and highly sensitive and offers the unique advantage of the ability to tag the mismatch sites with the Mu DNA sequence. Use of labeled Mu DNA eliminates the need for labeling individual target DNA samples. Further, the Mu end sequence can be used as a primer site for PCR amplification of the transposon-tagged DNA. One can make use of this feature in a variety of ways, for example, in devising strategies for analysis of a large target region or a large number of separate regions from a single transposition reaction. After a few rounds of amplification of an expansive target region (or even without initial amplification), the transposition step can be carried out and the products used for a second round of amplification by using one Mu end primer and a primer specific to each subregion of interest. This also eliminates the need for the labeled Mu DNA and avoids the ambiguity of the possible mismatch location caused by the detection of both halves of the cleaved products. Another utility of the Mu end primer would be the convenient sequencing of the reaction products. Not only is the location of the mutation deduced from the fragment size, but the nature of the mutations can be immediately identified by sequencing with a Mu end primer (14). These features will be especially useful for bulk detection and identification of single-nucleotide polymorphism. Finally, bulk isolation of DNA containing mutations would be possible, e.g., by using biotin-labeled Mu end DNA.

The high specificity for mismatch target sites exhibited by Mu transposition is unexpected. There is no obvious physiological reason that the transposition reaction should be directed to mismatch DNA sites. This specificity must reflect the unique deformed structure assumed by the target DNA when it is captured by the transposon-transposase complex. That transposition to nonmismatch sites appears to be suppressed when mismatch sites are available suggests that the transposon–transposase complex samples a large number of potential target sites before ST. It remains to be investigated whether transposons other than Mu also exhibit similar types of selectivity for mismatched DNA sites.

In summary, the Mut-Map can be used as a simple and convenient mutation analysis and genetic diagnosis tool. It can detect all single-nucleotide and short substitution mutations with high sensitivity by a single-step reaction in combination with standard PCR procedures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Greene, Bob Craigie, and Tania Baker for careful reading of the manuscript. This work was in part supported by the fund from the National Institutes of Health Intramural Aids Targeted Antiviral Program.

Abbreviations

CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

ST, strand transfer

CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

References

- 1.Mizuuchi K. (1992) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61, 1011-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savilahti H., Rice, P. A. & Mizuuchi, K. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 4893-4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuuchi M. & Mizuuchi, K. (1989) Cell 58, 399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craigie R. & Mizuuchi, K. (1986) Cell 45, 793-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker T. A., Mizuuchi, M., Savilahti, H. & Mizuuchi, K. (1993) Cell 74, 723-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sambrook J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T., (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 7.Orita M., Suzuki, Y., Sekiya, T. & Hayashi, K. (1989) Genomics 5, 874-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer S. G. & Lerman, L. S. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80, 1579-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotton R. G. H., Edkins, E. & Forrest, S., (1998) Mutation Detection: A Practical Approach (IRL, Oxford).

- 10.Myers R. M., Lerman, L. S. & Maniatis, T. (1985) Science 229, 242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotton R. G., Rodrigues, N. R. & Campbell, R. D. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 4397-4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youil R., Kemper, B. W. & Cotton, R. G. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 87-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mashal R. D., Koontz, J. & Sklar, J. (1995) Nat. Genet. 9, 177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi T., Mizuuchi, M., Robinson, E. A., Appella, E., O'Dea, M. H., Gellert, M. & Mizuuchi, K. (1987) Nucleic Acids Res. 15, 771-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]