Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is a common malignant tumor of the digestive tract with a high mortality rate. TFF3 is a secreted protein expressed in various cancers. The aim of the study is to report that inhibiting TFF3 increases the function and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in colorectal tumor tissues.

Methods

The proteomics analysis confirmed the high expression of secreted TFF3 in the supernatant of colorectal cancer cells, and databases were used to analyze the immune infiltration in tumor tissues. qPCR test was used to demonstrate the high levels of secreted TFF3 affecting the function of CD8+ T cells. In vivo experiments were used to observe the effects of TFF3 knockdown on tumor growth and immune cell infiltration. Tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes were sorted for RNA sequencing and mechanism explanation.

Results

Inhibiting the expression of TFF3 in tumor tissues improved immune cell infiltration and enhanced anti-tumor effects. TFF3 knockdown downregulated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues through the AKT/mTOR pathway, which enhanced the function of CD8+ T cells.

Conclusion

Knockdown of TFF3 improved the infiltration of CD8+ T cells and anti-tumor capabilities.

Keywords: TFF3, Immune infiltration, PD-L1

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal tumors worldwide, with a high mortality rate [1]. TFF3 is a member of the trefoil factor family (TFF), which belongs to a secreted protein expressed in various cancers [2]. Studies have reported that TFF3 expression is increased during the development and progression of CRC [3]. For instance, Haijiang Wang et al. proved that high TFF3 expression was significantly associated with multiple clinicopathological parameters and a poorer prognosis [4]. ZhiNan Chen et al. have revealed that elevated TFF3 expression in CRC promotes cancer progression and correlates with poor survival [5].

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells are one of the important components of the tumor microenvironment (TME). The TME contains various immunosuppressive cells, such as regulatory T cells and inhibitory molecules, such as TGF-β and IL-10, that suppress the activity and function of CD8+ T cells [6].

Recently, CAR-T cell therapy has achieved significant progress in hematological malignancies; its application in solid tumors still faces challenges, mainly due to the immunosuppressive microenvironment of solid tumors and the physical barriers of the tumor matrix [7]. This study aims to explore whether TFF3 is associated with immune infiltration in colorectal cancer and to illuminate its mechanism of action.

Material and methods

Tumor-conditioned medium (TCM) and conditional medium (CM) preparation

DLD1 and NCM460 cells were plated on T25 cell culture flask in RMPI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher). The next day, when the cells were 80% confluent, the growth medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS three times and cultured in serum-free medium for 48h [8]. T cells are cultured with a 3:1 ratio of TCM or CM and complete culture medium.

Proteomics and TCGA datasets analysis

Orbitrap Astral was used to identify differentially expressed proteins between CM and TCM. Protein quantification results were statistically analyzed, and differentially expressed proteins were defined as those with significant quantitative differences between the CM and TCM groups (p-value < 0.05, |log2FC|> 1). Immune infiltration data from tumor tissues of colorectal cancer patients was collected from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Patients were divided into high-expression and low-expression groups based on the median FPKM expression levels of TFF3 in all tumor tissues from the TCGA-COAD database to validate the different levels of immune cell infiltration. The expression level of GZMB and PRF1 was compared between the high-expression and low-expression TFF3 groups based on the median FPKM in primary tumor tissues from the TCGA-COAD database.

The culture of primary T cells

PBMCs were isolated from the peripheral blood from healthy donors using lymphocytes separation medium. CD8+ T cells were negatively selected from PBMCs using human T cell isolation kit (BioLegend) and activated by 10 ng/mL rhIL-2 (STEMCELL) and CD3/CD28 (STEMCELL) in the RMPI 1640 medium.

qPCR analysis

qPCR was used to detect the relative expression level of GZMB, PRF1, IFNG, and TNF. The forward primer of GZMB was CCCTGGGAAAACACTCACACA, and the reverse primer was GCACAACTCAATGGTA CTGTCG. The forward primer of PRF1 was GGCTGGACGTGACTCCTAAG, and the reverse primer was CTGGGTGGAGGCGTTGAAG. The forward primer of IFNG was TCGGTAACTGACTTGAATGTCCA, and the reverse primer was TCGCTTCCCTGTTTTAGCTGC. The forward primer of TNF was CCTCTCTCTAATCA GCCCTCTG, and the reverse primer was GAGGACCTGGGAGTAGATGAG.

ELISA

We collected the supernatant from NCM460, HT29, and DLD1 cell lines to verify the proteomics results with a human TFF3 ELISA kit (Elabscience). Mouse serum was collected prior to euthanasia and used to detect the levels of TNF and GZMB with ELISA kits (Elabscience). The tumor interstitial fluid was collected for the TFF3 detection.

In vivo antitumor studies

Animal experiments were performed in the Laboratory Animal Center of Peking University First Hospital. Healthy male BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks were used as experimental mice in vivo antitumor studies. Mice were allocated to experimental groups by simple randomization. For the colorectal cancer cell line-based xenograft models, 1 × 106 CT-26 shNC and CT-26 shTFF3 cells in 100ul PBS were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of mice. Starting from the 6th day after subcutaneous injection, tumor volume was measured every 3 days with a caliper by blinded manner and calculated by the following equation: Tumor volume = (length × width2)/2.

On the 24th day, the mice were euthanized, serum was collected for the ELISA, and tumor tissues were isolated to prepare the single-cell suspensions and tumor interstitial fluid (TIF) and fixed with paraformaldehyde.

Solation of tumor interstitial fluid

Tumor-bearing animals were euthanized on day 24; tumors were then briefly rinsed in room temperature saline and blotted on filter paper. The tumors were then put onto nylon filters affixed atop conical tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 106 × g. TIF was then collected from the conical tube [9].

Preparing single-cell suspension

The digestion solution for each tumor tissue was composed of 500 μL of collagenase/hyaluronidase solution (STEMCELL), 750 μL of DNase I solution (STEMCELL), and 3.75 mL of RPMI 1640 medium. A scalpel was used to chop the tumor tissue into small pieces, and the tissue was then placed into the digestion solution and incubated on a 37 °C shaker for 25 min. The 70-μm nylon mesh filter was used for filtration. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was discarded. Ten milliliters of red blood cell lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher) was added to the cell pellet, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min before being centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min.

Flow cytometry of tumor-infiltrating immune cells

The isolated cells were incubated with anti-CD3-APC (BioLegend, #100236), anti-CD4-PE (BioLegend, #100408), anti-CD8-BV421 (BioLegend, #100753), anti-CD49b-PE/Cy7 (BioLegend, #103518), anti-CD11c-BV605 (BioLegend, #117334), anti-CD19-APC/Cy7 (BioLegend, #115530), anti-CD45-BV711 (BioLegend, #103147), anti-CD11b-BV785 (BioLegend, #101243), and 7AAD (BioLegend, #420404) for 30 min on ice. After washing with PBS, cells were resuspended with FACS buffer. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

Immunofluorescence

To detect the infiltration of CD8+ T lymphocytes in tumor tissues, the tumors were embedded and sectioned. These slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated; antigens were retrieved using pH 9.0 Tris–EDTA buffer. Slides were blocked and incubated with rabbit anti-mouse CD8 antibody (Abcam, #217344) overnight at 4 ℃. The slides were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies Goat anti-rabbit Alex Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher, #A-21244) and the nuclear counterstain was DAPI (Thermo Fisher).

RNA sequencing

Tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes were sorted based on kits for mouse CD45 (STEMCELL) selection and CD3 selection (BioLegend), the sorted cells were extracted RNA with TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). Transcriptome profiling was conducted via high-throughput RNA sequencing on the Illumina platform. Raw reads were first subjected to quality control to eliminate residual adapter sequences and low-quality bases. Clean reads were then accurately and rapidly aligned to the reference genome to obtain genomic coordinates; the reference genome version was Mus musculus GRCm39. Gene-level read counts were subsequently quantified as the number of reads mapping within each annotated gene locus from start to stop. Differentially expressed genes were finally identified using DESeq2 package. In differential gene expression analysis, statistically significant differentially expressed genes were identified using established thresholds: p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC|> 1.

Protein interaction analysis

The Genecards database (https://www.genecards.org) was used to screen for genes related to immune infiltration (Relevance score > 35), and the ClueGO plugin in Cytoscape software was used to perform KEGG enrichment analysis on these related genes.

Western blot

To detect the expression level of PD-L1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #60475), P-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology, #4060)/AKT (Abcam, #179463), and P-mTOR (Abcam, #109268)/mTOR (Abcam, #134,903), the mouse tumor tissues were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor. After BCA quantification, the samples were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels, electrophoresed, transferred onto PVDF membranes, blocked with 5% BSA, and incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 ℃. The next day, the membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with a secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, #7074) 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody that avoids interference of heavy and light chains (Cell Signaling Technology, #5127) was used in the Co-IP experiments.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was examined by a Pierce Crosslink Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit (Thermo Fisher). Ten micrograms of TFF3 antibody (Abcam, #108599) and IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, #3900) were combined with Protein A/G Magnetic Beads; the crosslinked antibody to the beads was reacted with DSS for 30 min. The ice-cold IP Lysis/Wash Buffer was added to HT-29 cells and incubated on ice for 5 min with periodic mixing. Cells were centrifuged at ~ 13,000 × g for 10 min. Cell lysate was incubated with antibody-crosslinked beads overnight at 4 °C. The bound antigens were eluted for subsequent analysis.

CEA-CAR construction

The sequence of scFv provided by Genechem Company had the structure of VH-(G4S)3-VL. The CAR contained the CD8α signal peptide, followed by scFv linked in-frame to the hinge domain of the CD8α molecule, the transmembrane region of the CD8α molecule, and the intracellular signaling domains of the CD137 and CD3ζ molecules.

Lentivirus production

The coding sequence of the representative CAR was inserted into the lentiviral vector GV401 (Genechem) and named pLV-CAR. pHelper 1.0 vector (Addgene) and pHelper 2.0 vector (Addgene) were used to package pLV-CAR as a virus in human embryonic kidney 293 T cells.

Flow cytometry of co-culture apoptosis

CEA CAR-T cells were used for co-culture with DLD1 cells at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2. Following 20 h of coculture, Annexin-V and PI apoptosis assay kit (BioLegend, #640932) was used to validate the cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells against DLD1 shNC and shTFF3 colorectal cancer cell line. Apoptosis rate (%) = (early apoptotic cells + late apoptotic cells) / total cell count × 100%.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons between two groups, if the data from both groups follow a normal distribution and have equal variances, the T-test was used for statistical analysis; otherwise, a non-parametric rank sum test was used.

For multiple group comparisons, if the data meet the criteria of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, use ANOVA analysis; otherwise, use non-parametric tests, such as the Kruskal–Wallis H test (* < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001).

Results

TFF3 has a high secretion level in the colorectal tumor conditional medium

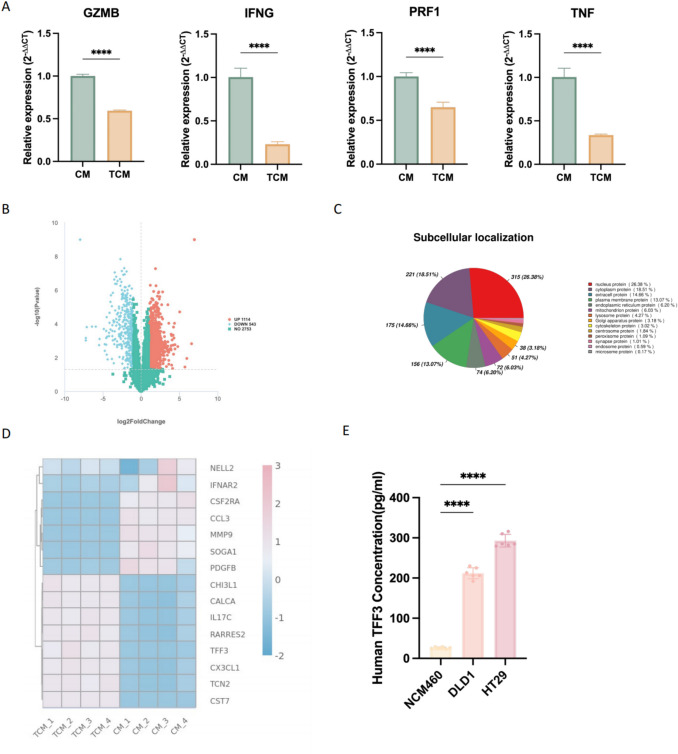

qPCR results showed that the expression levels of GZMB, PRF1, IFNG, and TNF in CD8+ T cells cultured in TCM were all downregulated (Fig. 1A). The differentially expressed proteins between the CM and TCM groups were shown in Fig. 1B; a total of 1114 proteins were upregulated in expression, while 543 proteins were downregulated. The distribution of subcellular localization was shown in Fig. 1C, where only protein with clear localization was presented. TFF3 was one of the most differentially expressed extracellularly secreted proteins (Fig. 1D). An ELISA kit was used to verify the secretion levels of TFF3 in the supernatants of NCM460, HT-29, and DLD1 cell lines; the results showed that the levels of TFF3 in the colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and DLD1 were significantly higher than those in the normal intestinal epithelial NCM460 cells (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

TFF3 has a high secretion level in the colorectal tumor conditional medium. A Gene expression level related to the function of CD8+ T cells (mean ± SD, n = 4). B The differentially expressed proteins between the CM and TCM groups. C Subcellular localization of differentially expressed proteins. D The most differentially expressed extracellular secreted proteins. E. The secretion level of TFF3 (mean ± SD, n = 6)

TFF3 affects the infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells into colorectal tumor

CIBERSORT was used for immune infiltration analysis, with immune cell reference marker gene expression derived from LM22 [10], which consists of gene expression signature data for 22 types of immune cells. Figure 2A showed the immune infiltration in tumor tissues of all patients from the TCGA-COAD database; the correlation of immune cells was shown in Fig. 2B. The immune cell infiltration analysis results showed that in tumor tissues with high expression of TFF3, the infiltration of CD8+ T cells was reduced compared to the low expression group, while the infiltration of Treg cells increased (Fig. 2C). Meanwhile, in the primary tumor tissues, the increased expression of TFF3 was accompanied by a downward trend in the expression of GZMB and PRF1 based on the median FPKM from the TCGA-COAD database (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

TFF3 affects the infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells into colorectal tumor. A The immune infiltration in tumor tissues of all patients from the TCGA-COAD database. B The correlation of immune cells from the TCGA-COAD database. C Analysis of immune cell infiltration in tumor samples with varying levels of TFF3 expression. D The level of GZMB and PRF1 based on the different expression of TFF3. E The secretory level of TFF3 after knockdown (mean ± SD, n = 4). F The expression level of GZMB, TNF, and IFNG after the knockdown of TFF3 (mean ± SD, n = 3)

To investigate the role of TFF3 in tumor growth, we generated DLD1 TFF3 knockdown (shTFF3) cell line via transduction with a lentiviral vector expressing GFP and human TFF3 short hairpin RNA (shRNA). The human TFF3 ELISA kit was used to verify the expression level between the DLD1 shNC and DLD1 shTFF3; accordingly, the TFF3 expression level was significantly decreased in the DLD1 shTFF3 cells (Fig. 2E). We collected the TCM from DLD1 shTFF3 and shNC cells and co-cultured them with CD8+ T cells for 48 h. The qPCR results indicated that the expression levels of GZMB, TNF, and IFNG were increased after the knockdown of TFF3 (Fig. 2F).

Knockdown of TFF3 increases the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in vivo

To confirm whether inhibiting TFF3 in vivo increased the infiltration of CD8+ T cells and enhanced anti-tumor efficacy, we generated CT-26 TFF3 knockdown (shTFF3) cell line via transduction with a lentiviral vector expressing GFP and mouse TFF3 short hairpin RNA (shRNA). From the tumor growth curve, it could be seen that the tumor volume significantly decreased in the group with TFF3 knockdown compared to the shNC group (Fig. 3A–B). Prior to euthanasia, tumor interstitial fluid was harvested for ELISA, which revealed a marked reduction in TFF3 secretion from shTFF3 tumors relative to controls (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of TFF3 restricted tumor growth. A Tumor growth curve of CT-26 inoculated with control (shNC) or shTFF3 tumor cells (mean ± SEM, n = 6). B The tumor was excised from the mice at the time of euthanasia. C The concentration of TFF3 from tumor interstitial fluid (n = 3). D The infiltration of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the mice tumor. E Flow cytometry analysis of the immune infiltration (n = 5). F The secretory level of TNF and GZMB in mouse serum (mean ± SD, n = 4)

The fresh tumor tissues were digested into the single-cell suspensions to detect immune cell infiltration through flow cytometry analysis. There was an increase in the infiltration of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3D–E); additionally, the shTFF3 group exhibited significantly expanded populations of CD11b⁺ and CD19⁺ cells compared with controls in tumor tissues (Fig. 3E). The ELISA tests showed that the serological TNF and GZMB were significantly increased in the shTFF3 tumor-bearing mice compared with the control tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 3F). These findings have supported the role of TFF3 in inducing immune infiltration in vivo.

For fresh tumor tissues, they were also used to sort tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes for RNA sequencing (Fig. 4A). The differential gene expression analysis within T cells revealed heightened expression of CD8A, CD4, TNFRSF18, IFNG, CD247, and PRF1 (Fig. 4C); these genes were closely related to the function of T lymphocytes. KEGG enrichment analysis showed the potentially related pathways (Fig. 4D), such as the T cell receptor signaling pathway, PD-L1 expression, and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of TFF3 increases the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in vivo. A Schematic diagram for RNA-seq of tumor cells and T cells sorted from CT-26 tumors formed by shNC and shTFF3 tumor cells. B Detection of CD8+ T cells in tumors with immunofluorescence. Scale bars represent 50 µm (mean ± SD, n = 3). C Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes for TIL-T. D KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes for TIL-T

We proceeded with immunofluorescence experiments to investigate whether there was an increase in CD8+ T cell infiltration in CT-26 shTFF3 tumor tissues. The results showed that the knockdown of TFF3 led to an increase in CD8+ T cell infiltration (Fig. 4B).

Knockdown of TFF3 reduces the expression level of PD-L1 on tumor

We used Genecards database to screen for genes related to immune infiltration (Relevance score > 35). The ClueGO plugin in Cytoscape software performed KEGG enrichment analysis on these related genes (Fig. 5A). Combined with the results from the above RNA-seq, we decided to focus primarily on the PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of TFF3 reduces the expression level of PD-L1 on tumor. A The KEGG enrichment analysis on immune infiltration-related genes was performed by the Cytoscape software. B The expression level of PD-L1 in tumor tissues (mean ± SD, n = 3). C Genes participated in the PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer

The WB result illuminated that the expression level of PD-L1 in tumor tissues decreased after the knockdown of TFF3 (Fig. 5B). Cytoscape software was used to show all genes participating in the PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer (Fig. 5C).

Knocking down TFF3 inhibits the AKT/mTOR pathway

As shown in Fig. 5C, the AKT/mTOR pathway regulates the expression of PD-L1. We then examined the changes in the AKT/mTOR pathway; the grayscale value of p-Akt/Akt and p-mTOR/mTOR revealed the mechanism by which knocking down TFF3 led to the downregulation of PD-L1 expression (Fig. 6A–B) [11]. The results of Co-IP showed that both proteins were present in the precipitated complex that demonstrated an interaction between TFF3 and AKT (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Knocking down TFF3 inhibits the AKT/mTOR pathway. A The expression level of p-AKT/AKT (mean ± SD, n = 3). B The expression level of p-mTOR/mTOR (mean ± SD, n = 3). C Validation of the interaction between TFF3 and AKT by Co-IP. D The construction of CEA-CAR. E The apoptosis rates of DLD1 shTFF3 and DLD1 shNC cancer cell lines (mean ± SD, n = 7)

The construction of CEA-CAR was shown in Fig. 6D. The apoptosis flow cytometry results showed that CAR-T cells exhibit more significant cytotoxicity against DLD1 shTFF3 compared with the DLD1 shNC cancer cell lines (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

As one of the most common malignant tumors, more than 2 million individuals are diagnosed with colorectal cancer each year worldwide [12]. CD8+ T cells recognize abnormal antigens on the surface of tumor cells and directly kill tumor cells through cytotoxic effects. They release cytotoxic molecules such as perforin and granzymes, which directly induce apoptosis in tumor cells [13]. CD8+ T cells are one of the main targets of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. By blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, the activity of CD8+ T cells could be restored, enhancing their ability to kill tumor cells [14].

The trefoil factor family consists of three disulfide-rich peptides (TFF1, TFF2, TFF3) that are abundantly secreted in the gastrointestinal tract, where they regulate gut homeostasis [15]. They also have the therapeutic potential to treat a variety of gastrointestinal disorders associated with mucosal damage [16]. TFF3, as one of the most differentially expressed secreted proteins in TCM and CM, has not been previously reported for its effects and mechanisms on immune cell infiltration. This study found that knocking down TFF3 resulted in an upregulation of GZMB, TNF, and IFNG, which were related to the function of CD8+ T cells.

GZMB and PRF1 are important effector molecules of CD8+ T cells, primarily involved in cytotoxic functions. They assist in mediating the cell-mediated immune response against cancer cells upon their release [17]. TNF and IFN-γ were secreted by CD8+ T cells to enhance cytotoxic function. TNF induces the necrosis or apoptosis of cancer cells, while IFN-γ promotes the death of infected or cancer cells by activating intracellular apoptotic pathways [18]. Meanwhile, multicolor flow cytometry in mice revealed that the infiltration of macrophages marked by CD11b and B cells marked by CD19 in tumor tissues also increased in addition to CD8+ T cells.

The AKT/mTOR signaling pathway has extensive regulatory roles within cells, affecting a variety of cellular functions. It regulates cell survival, cell growth, and cell cycle progression [19]. The activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway promotes the expression of PD-L1. Studies have shown that the oncogenic activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer can regulate the expression of PD-L1, thereby promoting tumor immune evasion [20]. Furthermore, TGF-β1 upregulates the expression of PD-L1 by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in fibroblasts [21]. Our experiments suggest an interaction between TFF3 and AKT; however, determining whether this association reflects direct binding or is indirectly mediated by intermediate cofactors will require further assays, such as pull-down, surface plasmon resonance experiments.

A study has shown that TFF3 promotes the proliferation and migration of gastric mucosal epithelial cells and maintains the integrity of the mucosal epithelium after injury by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [22]. Although TFF3 plays an important role in cell repair and regeneration, it promotes the growth and spread of cancer cells under certain pathological conditions. A recent mechanistic study revealed that CD147 knockout in colorectal cancer cell lines entirely abrogates TFF3-induced proliferation, migration, and invasion [5]; the authors proposed that targeting the TFF3-CD147 axis represents a novel therapeutic strategy to counteract TFF3-driven colorectal cancer progression. Peter E. Lobie et al. demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of TFF3 sensitizes lung adenocarcinoma cells to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) [23].

Although CAR-T therapy has achieved good efficacy in hematological tumors, the efficacy of CAR-T cells for solid tumors remains unsatisfactory; the tumor microenvironment interferes with and inhibits the effector function of immune cells [24]. Solid tumors are characterized by a densely woven extracellular matrix and a chaotic, poorly perfused vasculature that collectively construct formidable physical barriers, severely limiting CAR-T cell penetration into the tumor parenchyma [25]. Some studies have shown that the inhibitor of TFF3 named AMPC inhibited tumor growth [2, 26]. Our study demonstrated that inhibiting TFF3 enhances CD8⁺ T cell infiltration and augments their effector function within the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, the TFF3 inhibitors combined with CAR-T therapy potentially promote the infiltration of CAR-T cells and restrict the growth of tumor.

Regarding safety, given that TFF3 plays a crucial role in the protection and repair of the gastrointestinal mucosa, systemic inhibition of TFF3 may potentially compromise intestinal barrier function. For example, TFF3 maintains the intestinal barrier by regulating tight junction proteins such as Claudin-1, ZO-1, and Occludin [27]. Inhibition of TFF3 may affect the expression and distribution of these proteins, leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction. Therefore, prior to systemic administration of TFF3 inhibitors, it is essential to elucidate pharmacokinetic properties and establish a dosage gradient, while monitoring gastrointestinal responses in real time.

Our findings underscore the clinical relevance of TFF3 as a potential therapeutic target in colorectal cancer immunotherapy. TFF3 blockade is expected to amplify CD8⁺ T cell infiltration within the tumor microenvironment, thereby bolstering antitumor immunity. By enhancing CD8⁺ T cell recruitment, TFF3 inhibition could synergize with immune-checkpoint inhibitors or CAR-T cell therapies, extending clinical benefit to a wider spectrum of patients. The tumor microenvironment is a complex system comprising diverse cell types and signaling pathways28. Modulation of a single factor (such as TFF3) may be insufficient to completely alter the immunosuppressive state of the tumor, necessitating the integration of other therapeutic strategies. In addition, the findings derived from animal models and in vitro systems must ultimately be corroborated through rigorously designed clinical trials to establish their therapeutic efficacy in human colorectal cancer patients.

Conclusions

TFF3 knockdown downregulated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues through the AKT/mTOR pathway that enhanced the function and infiltration of CD8+ T cells. TFF3 knockdown markedly increased the apoptotic rate of colorectal cancer cells upon co-culture with CAR-T cells. In the future, inhibition of TFF3 while administering CAR-T therapy may enhance the anti-tumor effects of T cells in solid tumors.

Author contribution

Xiaoxue Pan performed the and analyzed the most experiments and wrote the original draft. Jichang Li performed the statistical analyses. Jing Zhu, Xin Wang and Yucun Liu provided technical guidance for the experiment. Shanwen Chen acquired funding support, provided methodological guidance for the experiment and edited the manuscript. Pengyuan Wang provided methodological guidance for the experiment and supervised the project.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(32370837); Beijing Nova Program (20230484244); Peking University Clinical Scientist Training Program (BMU2023PYJH001), supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”; and the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Scientific and Technological Achievements Transformation Incubation Guidance Fund Project of Peking University First Hospital) (2023CX04).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shanwen Chen, Email: shanwen@pku.edu.cn.

Pengyuan Wang, Email: pengyuan_wang@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Biller LH, Schrag D (2021) Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA 325(7):669–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo H, Tan YQ, Huang X et al (2023) Small molecule inhibition of TFF3 overcomes tamoxifen resistance and enhances taxane efficacy in ER+ mammary carcinoma. Cancer Lett 579:216443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yio X, Zhang JY, Babyatsky M et al (2005) Trefoil factor family-3 is associated with aggressive behavior of colon cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis 22(2):157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusufu A, Shayimu P, Tuerdi R et al (2019) TFF3 and TFF1 expression levels are elevated in colorectal cancer and promote the malignant behavior of colon cancer by activating the EMT process. Int J Oncol 55(4):789–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui HY, Wang SJ, Song F et al (2021) CD147 receptor is essential for TFF3-mediated signaling regulating colorectal cancer progression. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6(1):268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thepmalee C, Panya A, Sujjitjoon J et al (2020) Suppression of TGF-β and IL-10 receptors on self-differentiated dendritic cells by short-hairpin RNAs enhanced activation of effector T-cells against cholangiocarcinoma cells. Hum Vaccin Immunother 16(10):2318–2327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maalej KM, Merhi M, Inchakalody VP et al (2023) CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol Cancer 22(1):20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu C, Qiao W, Li X et al (2024) Tumor-secreted FGF21 acts as an immune suppressor by rewiring cholesterol metabolism of CD8+T cells. Cell Metab 36(3):630-647.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan MR, Danai LV, Lewis CA et al (2019) Quantification of microenvironmental metabolites in murine cancers reveals determinants of tumor nutrient availability. eLife 8:e44235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR et al (2015) Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 12(5):453–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Chen W, Xu ZP et al (2019) PD-L1 distribution and perspective for cancer immunotherapy-blockade, knockdown, or inhibition. Front Immunol 10:2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leowattana W, Leowattana P, Leowattana T (2023) Systemic treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 29(10):1569–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philip M, Schietinger A (2022) CD8+ T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 22(4):209–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dersh D, Hollý J, Yewdell JW (2021) A few good peptides: MHC class I-based cancer immunosurveillance and immunoevasion. Nat Rev Immunol 21(2):116–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braga Emidio N, Meli R, Tran HNT et al (2021) Chemical synthesis of TFF3 reveals novel mechanistic insights and a gut-stable metabolite. J Med Chem 64(13):9484–9495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braga Emidio N, Brierley SM, Schroeder CI et al (2020) Structure, function, and therapeutic potential of the trefoil factor family in the gastrointestinal tract. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 3(4):583–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen SP, Brunet M, Martin SJ (2010) Granzymes in cancer and immunity. Cell Death Differ 17(4):616–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St. Paul M, Ohashi PS (2020) The roles of CD8+ T cell subsets in antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol 30(9):695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaviano A, Foo ASC, Lam HY et al (2023) PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol Cancer 22(1):138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lastwika KJ, Wilson W, Li QK et al (2016) Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 76(2):227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Qi Y, Xia J et al (2024) The role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in mediating PD-L1 upregulation during fibroblast transdifferentiation. Int Immunopharmacol 142(Pt B):113186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Z, Liu H, Yang Z et al (2014) Intestinal trefoil factor activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway to protect gastric mucosal epithelium from damage. Int J Oncol 45(3):1123–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S, Tan YQ, Zhang X et al (2025) TFF3 drives Hippo dependent EGFR-TKI resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 44(11):753–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G, Rui W, Zhao X et al (2021) Enhancing CAR-T cell efficacy in solid tumors by targeting the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol Immunol 18(5):1085–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Zhang L, Dunmall LC et al (2024) The dilemmas and possible solutions for CAR-T cell therapy application in solid tumors. Cancer Lett 591:216871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng F, Wang X, Chiou YS et al (2022) Trefoil factor 3 promotes pancreatic carcinoma progression via WNT pathway activation mediated by enhanced WNT ligand expression. Cell Death Dis 13(3):265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin N, Xu LF, Sun M (2013) The protective effect of trefoil factor 3 on the intestinal tight junction barrier is mediated by toll-like receptor 2 via a PI3K/Akt dependent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 440(1):143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natu J, Nagaraju GP (2023) Gemcitabine effects on tumor microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: special focus on resistance mechanisms and metronomic therapies. Cancer Lett 573:216382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request to corresponding author.