Abstract

Previous studies showed that a subset of CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes expressing HLA class I-specific natural killer inhibitory receptors (iNKR) is characterized by the ability to recognize HLA-E and to mediate T cell receptor-dependent killing of different NK cell-susceptible tumor target cells. In this study, we show that this CD8+ T cell subset can also undergo extensive proliferation in mixed lymphocyte cultures in response to allogeneic cells. Analysis of their cytolytic activity revealed a broad specificity against a panel of allogeneic phytohemagglutinin-induced blasts derived from HLA-unmatched donors. On the other hand, autologous and certain allogeneic phytohemagglutinin blasts were resistant to lysis. We used as target cells the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP)-2−/− murine RMA-S cell line cotransfected with β2-microglobulin and HLA-E*01033. On loading these cells with different HLA-E-binding peptides derived either from HLA class I leader sequences or viral proteins, we could show that HLA-E-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes recognized many, but not all, peptides analyzed. These data suggest that these cells may recognize, on allogeneic cells, HLA-E with peptides that are not present in the host of origin. In addition to their ability to proliferate in response to allogeneic stimulation and to lyse, most allogeneic cells may have important implications in transplantation and in antitumor immune responses.

The capability of recognizing allogeneic cells is a well known T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated T lymphocyte function. Whereas TCRα/β+ CD4+ helper cells recognize MHC class II molecules, TCRα/β+ CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) are specific for MHC class I molecules (1). These T cell-mediated responses can be readily analyzed in vitro in mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC). MLC is characterized by a selective proliferation of allo-specific T lymphocytes and by the acquisition of specific cytolytic activity against cells bearing the stimulating alloantigens. Thus far, human alloreactive CTL have been shown to recognize classical HLA class I molecules, i.e., HLA-A, -B, and -C alleles (2). Other HLA class I molecules, including the nonclassical (or Ib) HLA-E, -F, or -G, characterized by a limited polymorphism, have not yet been shown to represent molecular targets for alloreactive CTL. These HLA class Ib molecules, however, may be recognized by HLA class I-specific inhibitory natural killer inhibitory receptors (iNKR). In particular, HLA-E is the specific ligand recognized by the CD94/NKG2A receptor (3, 4). The cell surface expression of HLA-E depends on the availability of peptides common to the leader sequence of various (but not all) HLA class I alleles.

The HLA class I-specific iNKR, including CD94/NKG2A, the Ig-like transcript 2/leukocyte Ig-like receptor (ILT2/LIR1, characterized by a broad specificity for HLA class I molecules), and the killer Ig-like receptors (KIR, recognizing allelic determinants of HLA class I molecules) may also be expressed by certain memory CTL in which they can inhibit TCR-mediated functions (5, 6). In a recent study, we showed that at least some of these CTL isolated from certain donors recognize HLA-E via their TCR and, by this mechanism, they lyse a panel of NK-susceptible tumor cell lines (hereafter referred to as NK-CTL) (7). HLA-E recognition by human CTL has been recently reported by two other groups (8, 9). In addition, evidence of CTL recognizing the nonclassical MHC class I molecule Qa-1 has been previously provided in mice (10).

In the present study, we identified TCRα/β+ alloreactive CTL specific for HLA-E. These cells may undergo extensive proliferation in MLC and lyse the stimulating allogeneic target cells. Also in this case, lysis is the result of TCR-mediated recognition. Different from classical CTL recognizing HLA-A, -B, or -C alleles, MLC-derived HLA-E-specific CTL are characterized by a broad reactivity with most (but not all) allogeneic target cells. These data may have important implications in transplant rejection and in disease as well as in responses against tumors.

Materials and Methods

mAbs and Flow Cytofluorimetric Analysis.

The reactivity of mAbs with cell populations was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence and cytofluorimetric analysis as previously described (11, 12). Leu-2a (IgG1, anti-CD8) and Leu-3a (IgG1, anti-CD4) mAbs were purchased from Becton Dickinson. mAbs anti-TCR pan α/β (IgG2b), anti-TCRVβ16 (IgG1), anti-TCRVβ22 (IgG1), anti-TCRVβ9 (IgG2a), and anti-TCRVβ3 (IgM) were purchased from Immunotech, Marseille. FITC- and phycoerythrin-conjugated antiisotype goat anti-mouse were purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associates. The culture medium used was RPMI medium 1640 (Seromed, Berlin) supplemented with 10% FCS (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), 1% antibiotic mixture (5 mg/ml of penicillin and 5 mg/ml of streptomycin stock solution), and human recombinant IL-2 was kindly provided by Chiron. Ficoll/Hypaque (Histopaque 1077) was purchased from Sigma.

Isolation, Culture, and Cloning of CD8+ T Lymphocytes.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood of normal donors by a Ficoll/Hypaque density gradient, as previously described (12). PBMCs were depleted of CD4+, CD16+, NKp46+, Vδ1+, and Vδ2+ cells by negative selection by using appropriate mAbs and magnetic beads coated with anti-mouse IgG (Dynal, Oslo). MLC were set up as described (13) by culturing CD8+ T cells in round-bottom microwells (105 cells per well) in the presence of irradiated (5,000 rads) allogeneic PBMCs (2 × 105 cells). At day 3, 25 units/ml of IL-2 was added. At day 8, cells were either restimulated or cloned under limiting dilution conditions (13).

Amplification and Sequencing of TCRVβ Rearrangements and HLA-E Alleles.

RNA samples were extracted by using RNAzol (Cinna/Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX), and oligo(dT)-primed cDNA were prepared by standard techniques. The coding primers Vβ16: 5′-GAC TGT GAC TCT GAG ATG TGA C; Vβ9: 5′-TAT AAA CAG GAC TCT AAG AAA TTT C; Vβ3: 5′-AGA TGT GAA AGT AAC CCA GAG CTC GAG ATA T and Vβ22: 5′-TGG GAC AGG AAG TGA TCT TGC were used in combination with Vβcost: 5′-GTG GGA GAT CTC TGC TTC TGA TCG CTC AAA to specifically amplify the Vβ transcripts (30 cycles PCR: 30 sec, 95°C; 45 sec, 55°C; and 1 min, 72°C). The second and third exons of HLA-E were amplified by using the set of primers HLA-E up: 5′-ACA CCG CAC AGA TTT TCC; HLA-E down: 5′-AGG GTG GCC TCA TGG TC (30 cycles PCR: 30 sec, 95°C; 30 sec, 56°C; and 30 sec, 72°C). All of the amplification products were cloned into pcDNA3.1/V5/His-TOPO vector by using the Eukaryotic-TOPO-TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen). To assign the Vβ rearrangements and the HLA-E alleles, at least 19 independent clones were sequenced by using d-Rhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit and a 377 ABI automatic sequencer (Perkin–Elmer/Applied Biosystems).

Assay for Cytolytic Activity.

Target cells used in these experiments were represented by a panel of PHA blasts derived from HLA-unmatched donors. The murine transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP)-2−/− T cell lymphoma RMA-S cell line, either wild type or transfected with human β2-microglobulin or cotransfected with HLA-E*01033 allele (kindly provided by J. E. Coligan, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD), was also tested. HLA-E+ RMA-S was previously incubated overnight at 37°C either alone or in the presence of the synthetic peptides at the final concentration of 200 μM. The peptides used in these experiments were the following: VMAPRTLVL from HLA-A2 allele leader sequence, VTAPRTVLL from some HLA-B alleles such as B15, VMAPRTLIL from HLA-Cw3 and cytomegalovirus gpUL40 leader sequence, VMAPRALLL from HLA-Cw7 leader sequence, VMAPRTLFL from HLA-G1 leader sequence, SQAPLPCVL from Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) BZLF-1 protein. Cells were tested for cytolytic activity in a 4-hr 51Cr-release assay as previously described (14) in the presence or absence of mAbs. The concentration of the mAbs used for the masking experiments was 10 μg/ml. The effector-to-target cell ratio used in all experiments was 10:1.

Results

Preferential Expansion of CD8+ T Cells Expressing iNKR on MLC Stimulation.

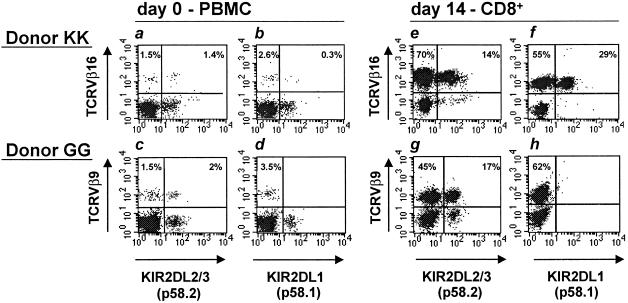

Preliminary studies indicated that iNKR+ CTL could be generated in certain MLC combinations. To analyze in more detail this phenomenon and the nature of proliferating cells, MLC were set up from various donors. Responding cells that had been restimulated in secondary MLC and cultured for an additional 7 days were analyzed for the expression of iNKR and for the preferential expansion of cells expressing given TCRVβ (i.e., two typical phenotypic features of the previously identified NK-CTL) (7). In four of 20 donors analyzed, a large increase in CD8+ T cells expressing iNKR could be detected. Remarkably, in three of these four donors, NK-CTL had previously been identified in peripheral blood (7). MLC-derived CD8+ iNKR+ T cells were characterized by the homogeneous expression of a given TCRVβ (different in different donors). Fig. 1 shows fresh PBMC and MLC-activated CD8+ T cells derived from two representative donors (KK and GG). More than 80% of CD8+ MLC-derived cells from donor KK were characterized by the expression of TCRVβ16. All of such TCRVβ16+ cells expressed both ILT2/LIR1 and CD94/NKG2A (not shown), whereas a fraction expressed the HLA-C specific KIR2D receptors. Notably, TCRVβ16+ cells represented a minor subset (<3%) of freshly isolated PBMC. In donor GG, more than 60% of CD8+ MLC-derived cells expressed TCRVβ9. Also in this case, all TCRVβ9+ cells expressed ILT2/LIR1 and CD94 (not shown), whereas only a fraction expressed KIR2DL2/3 (p58.2). TCRVβ9+ cells were present in small percentages in fresh PBMC (3.5%), and approximately half of these cells expressed KIR2DL2/3 (p58.2). Similarly, a high proportion of MLC-activated iNKR+ CD8+ T cells expressing one single TCRVβ were also observed in two other donors (donor GF expressing TCRVβ22 and donor OG expressing TCRVβ3).

Fig 1.

Surface coexpression of TCRVβ16 (donor KK) or TCRVβ9 (donor GG) with KIR2DL1 (p58.1) or KIR2DL2/3 (p58.2) KIRs. Phenotypic analysis on both donors has been performed at day 0 on PBMC and at day 14 on CD8+ T cells expanded in MLC. Donor KK was characterized, at day 0, by the presence of a small fraction of TCRVβ16+ KIR2DL2/3+ cells (a), whereas KIR2DL1 was hardly detectable on TCRVβ16+ cells (b). At day 14, the TCRVβ16+ cell fraction was significantly expanded (84%) and expressed KIR2DL1 or KIR2DL2/3 (e and f). Notably, KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL2/3 (p58.2) were never coexpressed and TCRVβ16+ cells that were KIR2DL1− and KIR2DL2/3− were in all instances ILT2/LIR1+ and CD94/NKG2A+ (not shown). Donor GG was characterized, at day 0, by the presence of a small fraction of TCRVβ9+ KIR2DL2/3+ cells (c), whereas KIR2DL1 was absent on TCRVβ9+ cells (d). At day 14, the TCRVβ9+ cell population was expanded (62%) and a fraction expressed KIR2DL2/3 but not KIR2DL1 (g and h). It is of note that, also in this case, all TCRVβ9+ cells were ILT2/LIR1+ and CD94+ (not shown).

To analyze the possible monoclonality of these iNKR+ CD8+ MLC-activated populations, we amplified and sequenced the TCRVβ chains expanded in the four donors. All donors displayed a monoclonal expansion that was different in different individuals (for donor KK: Vβ16S1J2S3BC2; for donor GG: Vβ9S1J1S2BC1; for donor GF: Vβ22S1J2S7BC2; for donor OG: Vβ3S1J2S5BC2).

MLC-Derived CD8+ iNKR+ CTL Display a Broad Specificity Against Allogeneic Cells.

MLC-activated cell populations from donors KK and GG were analyzed for their cytolytic activity against PHA blasts derived from the stimulating donors. In all instances, a strong cytolytic activity could be detected. We then analyzed whether iNKR+ T cells were themselves capable of lysing PHA blasts bearing the stimulating alloantigens. To this end, MLC populations were fractionated according to the expression or lack of surface iNKR and cloned under limiting dilution. Clones capable of lysing PHA blasts derived from the stimulating donor were found in both groups. Two representative clones derived from donor GG are shown in Fig. 2a. It is of note that clone GG1 expressing iNKR and TCRVβ9 lysed not only the specific PHA blasts derived from the stimulating donor ST but also those derived from the fully unmatched donor AM (Fig. 2a). On the contrary, clone GG7 (iNKR− TCRVβ9−) lysed the specific PHA blasts only. Thus, a major difference existed between iNKR+ TCRVβ9+ and iNKR− TCRVβ9− alloreactive clones in their ability to lyse PHA blasts from an unmatched donor. Remarkably, also iNKR+ TCRVβ16+ clones derived from donor KK displayed similar behavior (not shown). In view of these results, we analyzed in further detail the MLC-induced iNKR+ CTL populations from donors KK and GG for their ability to lyse PHA blasts derived from a large panel of allogeneic unmatched donors, as well as autologous PHA blasts. Notably, as shown in Table 1, the majority of allogeneic target cells were lysed by both TCRVβ16+ (donor KK) and TCRVβ9+ (donor GG) CTL populations. Moreover, the rare donors that were not lysed by TCRVβ16+ CTL were also resistant to the TCRVβ9+ CTL. Importantly, autologous PHA blasts were resistant to lysis. These data indicate that MLC-activated iNKR+ CTL display a broad reactivity against allogeneic cells. Remarkably, individuals belonging to the group of donors susceptible to lysis differ in terms of HLA-A, -B, or -C alleles.

Fig 2.

MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL display a broad alloreactivity that is TCR mediated and regulated by iNKR. (a) Two representative MLC-derived CTL clones from donor GG are shown. Clone GG1 expressed the iNKR+ TCRVβ9+ phenotype, whereas clone GG7 was iNKR− TCRVβ9−. In this cytolytic assay, target cells were represented by PHA blasts derived from the stimulating donor in MLC (donor ST; haplotype: A1;68 B44;51 Cw1;15) or from the fully unmatched donor AM (haplotype: A3;23 B49;62 Cw10). (b) Clone KK1 (iNKR+ TCRVβ16+) from donor KK was analyzed for its ability to lyse PHA blasts derived from three unmatched donors, either in the absence or in the presence of anti-TCRVβ16 mAb. (c) Three representative TCRVβ16+ clones from donor KK characterized by different iNKR phenotypes were tested for their cytolytic activity against allogeneic PHA blasts expressing the appropriate HLA class I protective alleles. Clones KK3 (KIR2DL2/3+, ILT2/LIR1+, CD94/NKG2A+) and KK6 (KIR2DL1+, ILT2/LIR1+, CD94/NKG2A+) were almost unable to lyse PHA blasts derived from donor AM (Cw10) and CB (Cw2;4) unless mAb specific for the appropriate KIR was added. On the other hand, clone KK1 (KIR2D− ILT2/LIR1+, CD94/NKG2A+) efficiently killed PHA blasts derived from donor CB both in the absence or in the presence of anti-ILT2/LIR1 and/or anti-CD94 mAbs. Fig. 2c also shows that clone KK6 did not lyse PHA blasts from donor AC (Cw2;7) even in the presence of anti-iNKR mAb. This donor belongs to the group of individuals who were resistant to HLA-E-specific CTL. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Cytolitic activity of iNKR+CD8+ T cells against a panel of PHA blasts from unmatched donors

| Donor

|

HLA-class I haplotype

|

% Lysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk GG iNKR+ Vβ9+ | Bulk KK iNKR+ Vβ16+ | ||||

| KK | A2;32 | B44 | Cw7 | 2 | 2 |

| GG | A2;25 | B7;18 | Cw7 | 0 | 2 |

| LM | A3;29 | B35;44 | Cw4;5 | 50 | 53 |

| ST | A1;68 | B44;51 | Cw1;15 | 34 | ND |

| GF | A1;3 | B27;44 | Cw2 | 32 | 40 |

| CB | A26;68 | B27;62 | Cw2;4 | 32 | 80 |

| GB3 | A3;32 | B7;35 | Cw4;7 | ND | 70 |

| RC | A2;29 | B44;51 | Cw7 | 38 | 40 |

| RB | A11;25 | B18;44 | Cw5 | 40 | 48 |

| AM | A3;23 | B49;62 | Cw10 | 78 | 45 |

| AG61 | A2;3 | B5;15 | Cw3;1 | 80 | ND |

| GB1 | A2;11 | B44;51 | Cw1;4 | 55 | 65 |

| GB2 | A3;32 | B7;35 | Cw5;7 | 25 | 78 |

| GB4 | A1;2 | B8;62 | Cw3;7 | ND | 60 |

| AC | A2 | B8;35 | Cw2;7 | 2 | 2 |

| LN | A1;24 | B8;49 | Cw7 | 1 | 1 |

>60% of these populations expressed TCRVβ9 or TCRVβ16, respectively.

Donor LM and donor ST represented the stimulator in MLC of donor KK and GG, respectively.

The Cytolytic Activity of MLC-Derived iNKR+ CTL Is Mediated by TCR and Regulated by iNKR.

We next investigated whether TCR was involved in the recognition of allogeneic PHA blasts by the MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL. As shown in Fig. 2b, the mAb-mediated masking of TCRVβ16 virtually abrogated the cytolytic activity of the representative clone KK1 against PHA blasts derived from different donors. These data suggest that the lysis of different PHA blasts is indeed TCR-mediated. Notably, MLC-derived CTL clones from donor KK and GG express iNKR that may interact with HLA class I molecules expressed by some of the allogeneic target cells analyzed. This possibility was evaluated in experiments in which iNKR+ TCRVβ16+ clones (donor KK) were tested against allogeneic PHA blasts expressing HLA class I molecules recognized by the iNKR. Three representative clones (KK1, KK3, KK6) expressing different iNKR phenotypes are shown in Fig. 2c. All of the clones were ILT2/LIR1+ CD94+. Clone KK3 also expressed KIR2DL2/3 (p58.2), whereas clone KK6 was KIR2DL1+ (p58.1+). It is evident that clones KK3 and KK6 did not lyse allogeneic PHA blasts expressing the relevant (protective) HLA-C alleles unless mAb specific for the appropriate KIR was added. On the other hand, clone KK1, expressing ILT2/LIR1 and CD94 only, was cytolytic both in the absence and in the presence of anti-ILT2/LIR1 and/or anti-CD94 mAbs. Remarkably, this was true for all clones that did not express KIRs. Thus they could kill allogeneic PHA blasts with no substantial interference by ILT2/LIR1 or CD94. A likely explanation for this finding is that these TCRVβ16+ clones expressed low surface density of CD94/NKG2A receptor, insufficient to deliver inhibitory signals capable of down-regulating TCR-mediated signaling. These data provide a convincing explanation for the pattern of cytotoxicity detected by using MLC-derived iNKR+ cell populations. Thus, as shown in Fig. 1, cells lacking KIR (but expressing ILT2/LIR1 and CD94) represented large fractions of the TCRVβ16+ (KK) and TCRVβ9+ (GG) cell populations. Fig. 2c also shows that clone KK6 did not lyse PHA blasts from donor AC even in the presence of anti-iNKR mAbs. Notably, donor AC belongs to the group of individuals who are resistant to lysis from both TCRVβ16+ and TCRVβ9+ CTL.

MLC-Derived iNKR+ CTL Recognize HLA-E Molecules.

The expression of iNKR together with the monoclonality and the apparent independence on HLA-A, -B, and -C recognition for their cytolytic activity suggested that MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL could be related to the recently described NK-CTL (7). Because we showed that the molecular basis of the cytolytic activity of NK-CTL is represented by the TCR-mediated recognition of HLA-E, we investigated whether MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL lysed allogeneic PHA blasts by the same molecular mechanisms. Regarding the TCR specificity, the recognition of HLA-E molecules could explain why these cells lysed PHA blasts derived from donors with different HLA-A, -B, and -C haplotypes.

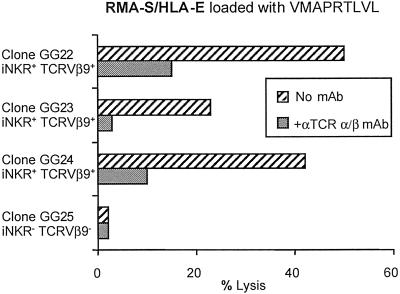

To investigate whether HLA-E was indeed the molecular target of the MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL, these cells were tested for their ability to lyse HLA-E+ cell transfectants. Thus, the TAP-2−/− RMA-S lymphoma cell line, either untransfected or stably transfected with human β2-microglobulin alone, or cotransfected with the HLA-E*01033 allele, was tested as target in a cytolytic assay. HLA-E-transfected RMA-S were loaded with the VMAPRTLVL peptide (derived from the HLA-A2 leader sequence) known to bind and stabilize HLA-E molecules or with the control irrelevant peptide EADPTGHSY (derived from MAGE-1). Fig. 3 shows the cytolytic activity of three iNKR+ TCRVβ9+ clones derived from donor GG (GG22, GG23, GG24). Only HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with the relevant peptide expressed HLA-E on their surface and were lysed. Moreover, mAb-mediated blocking of TCR resulted in a sharp inhibition of the lysis. Clone GG25 (iNKR− TCRVβ9−) shown as control, did not lyse HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with the relevant peptide. Taken together, these data further support the notion of an identity between MLC-derived iNKR+ cells and the previously described NK-CTL.

Fig 3.

MLC-derived iNKR+ CTL recognize HLA-E+ on cell transfectants. Lysis of HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with the HLA-A2 leader sequence-derived peptide (VMAPRTLVL) by representative iNKR+ TCRVβ9+ clones is shown. The three clones GG22, GG23, and GG24 were derived from donor GG. Inhibition of lysis was obtained in the presence of the anti-TCR pan α/β mAb. Clone GG25 iNKR− TCRVβ9− shown as control, did not lyse HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with VMAPRTLVL peptide. Similar results were obtained in four independent experiments.

Alloreactive iNKR+ CTL Display Specificity for HLA-E-Bound Peptides.

As illustrated above, PHA blasts from the majority of unmatched donors were killed by MLC-derived HLA-E-specific CTL. However, PHA blasts from a small group of donors (including autologous PHA blasts) were resistant to lysis. HLA-E molecules are characterized by a limited polymorphism (15) and are known to bind a relatively small number of peptides, including those derived from the leader sequence of different HLA class I alleles (3) as well as several peptides derived from viral proteins (16–18). Both the HLA-E polymorphism and the ability of the TCR to recognize different HLA-E-bound peptides could represent the molecular basis responsible for the different susceptibility to the lysis of the two groups of donors.

To investigate the possible role of the HLA-E polymorphism, we performed HLA-E typing of susceptible (AM and CB) or resistant (LN and AC) PHA blasts. To this end, we amplified from these representative donors the second and third HLA-E exons and sequenced the derived products. No correlation between HLA-E polymorphism and susceptibility to alloreactive iNKR+ CTL-mediated lysis was observed (data not shown). These data rule out the possibility that HLA-E polymorphism may be responsible for the susceptibility.

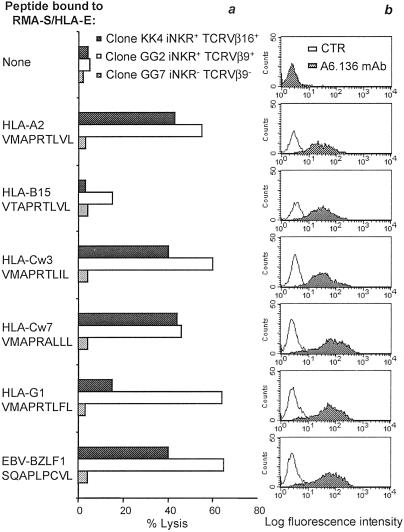

We next investigated whether different HLA-E-binding peptides could be recognized by HLA-E-specific CTL derived from donors KK and GG. To this end, we analyzed five different peptides derived from the leader sequence of the following HLA class I molecules: HLA-A2, -B15, -Cw3, -Cw7, and -G1. A peptide derived from the EBV BZLF-1 protein, which has been shown to bind HLA-E (18), was also tested. Fig. 4a shows that the HLA-E-specific CTL clones KK4 and GG2 lyse HLA-E+ cell transfectants that had been loaded with some (but not all) peptides analyzed. Thus, both KK4 and GG2 recognized HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with peptides derived from HLA-A2, -Cw3, -Cw7, but not -B15. On the other hand, GG2 but not KK4 clone lysed HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with HLA-G1-derived peptide. Remarkably, both clones lysed cells pulsed with the EBV BZLF-1 peptide. It is worth noting that all of the tested peptides, used at saturating concentrations (200 μM), were able to bind to HLA-E and to allow its surface expression at comparable levels (Fig. 4b). Thus, despite a similar expression of HLA-E/peptide complexes, only some were recognized. Although not shown, mAb-mediated masking experiments indicated that anti-TCRα/β mAb sharply inhibited the cytolytic activity against peptide-pulsed HLA-E+ RMA-S target cells. Taken together, these data indicate that the TCR expressed by HLA-E specific CTL, although characterized by an unusually broad reactivity, still display specificity for certain peptides. Fig. 4a also shows an informative control represented by the TCRVβ9− iNKR− alloreactive CTL clone GG7: this clone did not lyse any of the cell transfectants analyzed.

Fig 4.

Specificity of alloreactive NK-CTL for HLA-E-bound peptides. In these experiments the TAP-2−/− murine RMA-S cells transfected with human β2-microglobulin and HLA-E*01033 were incubated in the absence or in the presence of the indicated peptides. (a) Cytolytic activity mediated by two representative HLA-E-specific CTL clones isolated from donors KK (KK4: iNKR+ TCRVβ16+) and GG (GG2: iNKR+ TCRVβ9+). One representative iNKR− TCRVβ9− alloreactive CTL clone derived from donor GG (GG7) is shown as control. Similar results were obtained in three indipendent experiments. (b) Expression of HLA-E molecules on the surface of HLA-E+ RMA-S pulsed with the indicated peptides. Cells were stained with the anti-pan HLA class I A6.136 mAb.

Discussion

Our present study provides evidence for a novel type of human alloreactive CTL that undergo proliferation on allogeneic stimulation in MLC. These CTL express TCRα/β specific for the nonclassical HLA-E molecules and display one or more inhibitory NK receptor for HLA class I molecules (iNKR). Remarkably, these cells are characterized by the capability of lysing a broad panel of PHA blasts derived from different allogeneic donors, in a TCR-dependent fashion. On the other hand, they kill neither autologous nor a small group of allogeneic PHA blasts. This implies the existence of some degree of specificity related to HLA-E recognition. Indeed, we show that these CTL can distinguish among different HLA-E/peptide complexes, because they can kill HLA-E+ cell transfectants only when loaded with appropriate peptides.

Alloreactive CTL are usually directed against HLA-A, -B, and, less frequently, -C alleles. In view of the high degree of polymorphism of these classical HLA class I molecules, typical alloreactive CTL clones are usually highly specific for a given HLA class I allele (2). The present identification of alloreactive CTL specific for the poorly polymorphic HLA-E molecules discloses a novel scenario with important implications in transplantation and, possibly, in immune-mediated diseases. In this context, in HLA-E transgenic mice, HLA-E has been shown to behave as a strong transplantation antigen, thus indicating that, at least in this animal model, HLA-E may be responsible for transplant rejection similarly to classical HLA class I molecules (19). The potential involvement of HLA-E-specific CTL in transplantation is also suggested by the finding that these cells proliferate in MLC, overgrowing conventional alloreactive CTL. This occurs in MLC against irradiated PBMC derived from most donors analyzed. On the other hand, no HLA-E-specific CTL expansion was observed in MLC by using, as stimulating cells, PBMC derived from some donors. Remarkably, these donors corresponded to those not susceptible to lysis by HLA-E-specific CTL (see Table 1). It is possible that the preferential expansion in MLC of HLA-E specific CTL may be facilitated by the expression of KIR protecting these cells from apoptotic cell death, as supported by previous reports (20, 21).

The surface expression of iNKR together with a given TCRVβ rearrangement (different in different individuals) suggested that HLA-E-specific CTL could be identical to the recently identified NK-CTL (7). NK-CTL, characterized by the iNKR expression and by the ability to lyse different NK-susceptible tumor target cells, were described several years ago; however, no information was available on the molecular mechanisms mediating their function (22). Their ability to lyse different tumor target cells in an NK-like fashion was found to be independent of the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCR), or NKG2D, or 2B4, i.e., the receptors that are known to be involved in the NK-mediated cytolysis (not shown). Thus, although NK-CTL expressed NKG2D and 2B4 (whereas they lacked NCR), their cytolytic activity was not mediated by these receptors but was the result of the TCR-mediated recognition of HLA-E (7). Our present data provide evidence that NK-CTL and HLA-E-specific alloreactive CTL represent the same cell population. These cells are capable of discriminating between autologous and allogeneic cells and, among allogeneic cells, to specifically lyse PHA blasts or B-EBV cell lines from most, but not all, individuals. In addition, in line with their identity with NK-CTL, the HLA-E-specific CTL also displayed cytolytic activity against various NK susceptible tumor cell lines of different histotype.

Although our present data indicate that HLA-E-specific CTL are characterized by the expression of iNKR, it should be noted that iNKR+ CTL specific for classical HLA class I alleles have been described (23–27). Thus, the iNKR+ TCR α/β+ surface phenotype does not necessarily correspond to HLA-E-specific CTL.

An obvious question is the molecular basis of the ability to discriminate between HLA-E molecules expressed by different allogeneic target cells because only some were recognized and lysed. HLA-E is characterized by a limited polymorphism and binds a limited number of peptides. Both HLA-E polymorphism and the ability to recognize different HLA-E-bound peptides could explain the phenomenon. The HLA-E polymorphism involves few amino acidic positions (28). The analysis of this polymorphism revealed no differences between donors susceptible and donors resistant to HLA-E-specific alloreactive CTL clones. We then investigated whether HLA-E-specific alloreactive CTL clones could discriminate among different peptides, all capable of inducing the surface expression of HLA-E in cell transfectants. These experiments clearly indicated that different peptides that are bound to the same HLA-E molecule may be differentially recognized by alloreactive CTL. This occurred for peptides derived from the leader sequence of different HLA class I alleles. For example, peptides from HLA-A2, -Cw3, and -Cw7 were recognized by HLA-E-specific CTL, whereas HLA-B15-derived peptide was not. The pattern of peptide recognition was similar, but not identical, for the HLA-E-specific CTL isolated from donors KK and GG. Thus, the HLA-G1-derived peptide was clearly recognized only by one of the two donors analyzed. Remarkably, HLA-E-specific CTL from both individuals recognized two viral peptides bound to HLA-E. One is the VMAPRTLIL peptide corresponding to the cytomegalovirus gpUL40 protein and identical to the peptide derived from the leader sequence of HLA-Cw3 (17). The other is represented by the EBV BZLF-1 peptide (SQAPLPCVL) that is rather different from the HLA class I leader sequence-derived peptides (18). It is conceivable that other, still undefined, viral peptides may bind to HLA-E and be recognized by CTL. Identification of such viral peptides is important for a better understanding of the functional role of HLA-E-specific CTL. Indeed, viral infections may offer the key to explaining how HLA-E-specific CTL are generated in vivo. Thus, they could be the result of a chronic antigen-driven stimulation, possibly reflecting the recognition of an HLA-E-bound peptide derived from a persistent virus. In this context, HLA-E-specific CTL may play a relevant role in the defense against viruses that induce the down-regulation of HLA class Ia molecules, which represents a mechanism of escape from conventional CTL. Assuming that HLA-E-specific CTL are indeed generated in response to certain viral infections that can supply HLA-E-binding peptides (e.g., EBV and cytomegalovirus), it is conceivable that their broad alloreactivity may represent a “side product,” reflecting the crossreactivity between viral and HLA class I-derived peptides.

However, why does HLA-E-specific CTL fail to lyse autologous PHA blasts, even after mAb-mediated masking of their iNKR? A likely explanation is that the set of self peptides bound to HLA-E may have induced negative selection or anergy of T cells specific for these HLA-E/self peptide complexes. Remarkably, the set of HLA-E-binding self peptides (including those derived from the HLA class I leader sequence) could differ in different individuals, even when they share one or more HLA class I alleles. This may reflect a polymorphism of the TAP heterodimer and/or differences in the affinity of self peptides for HLA-E. Although it remains to be determined whether HLA-E may be responsible for thymic selection in humans, the nonclassical MHC-class I molecules have been shown to operate thymic selection in mice (29).

Importantly, our data have major implications for transplantation. Thus, it is conceivable that HLA-E-specific CTL that undergo extensive proliferation in vitro in MLC and are capable of killing a large panel of allogeneic cells may be involved in graft rejection, in case the donor does not express the HLA class I epitopes recognized by the KIR of the recipient. On the other hand, the development of host disease could involve HLA-E-specific CTL when the recipient does not express the HLA class I epitopes recognized by the KIR of the donor (30). In conclusion, both their broad reactivity and their independence from classical HLA class I molecules render HLA-E-specific-CTL highly responsive to allogeneic stimulation, thus providing new clues for a better understanding of alloreactivity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniela Pende for help and advice and Rosa Bellomo and Sara Moretti for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants awarded by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC), Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), Ministero della Sanità, and Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST), MURST 5%–Centre National de la Recherche Biotechnology Program 95/95, and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Progetto Finalizzato Biotecnologie.

Abbreviations

iNKR, natural killer inhibitory receptors

MLC, mixed lymphocytes culture

KIR, killer Ig-like receptors

TCR, T cell receptor

CTL, cytolytic T lymphocytes

PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

EBV, Epstein–Barr virus

References

- 1.Rock K. L. & Goldberg, A. L. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 739-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerottini J. C. & Brunner, K. T. (1974) Adv. Immunol. 18, 67-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braud V. M., Allan, D. S., O'Callaghan, C. A., Soderstrom, K., D'Andrea, A., Ogg, G. S., Lazetic, S., Young, N. T., Bell, J. I., Phillips, J. H., et al. (1998) Nature (London) 391, 795-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee N., Llano, M., Carretero, M., Ishitani, A., Navarro, F., Lopez-Botet, M. & Geraghty, D. E. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5199-5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mingari M. C., Ponte, M., Vitale, C., Maggi, E., Romagnani, S., Demarest, J., Pantaleo, G., Fauci, A. S. & Moretta, L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 12433-12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mingari M. C., Moretta, A. & Moretta, L. (1998) Immunol. Today 19, 153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietra G., Romagnani, C., Falco, M., Vitale, M., Castriconi, R., Pende, D., Millo, E., Anfossi, S., Biassoni, R., Moretta, L. & Mingari, M. C. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 3687-3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J., Goldstein, I., Glickman-Nir, E., Jiang, H. & Chess, L. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 3800-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia P., Llano, M., de Heredia, A. B., Willberg, C. B., Caparros, E., Aparicio, P., Braud, V. M. & Lopez-Botet, M. (2002) Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 936-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang H., Ware, R., Stall, A., Flaherty, L., Chess, L. & Pernis, B. (1995) Immunity 2, 185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moretta A., Bottino, C., Vitale, M., Pende, D., Cantoni, C., Mingari, M. C., Biassoni, R. & Moretta, L. (2001) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 197-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mingari M. C., Cambiaggi, A., Vitale, C., Schiavetti, F., Bellomo, R. & Poggi, A. (1996) Int. Immunol. 8, 203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moretta A., Pantaleo, G., Moretta, L., Mingari, M. C. & Cerottini, J. C. (1983) J. Exp. Med. 158, 571-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poggi A, Biassoni, R., Pella, N., Paolieri, F., Bellomo, R., Bertolini, A., Moretta, L. & Mingari, M. C. (1990) J. Exp. Med. 172, 1409-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braud V. M., Allan, D. S. & McMichael, A. J. (1999) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11, 100-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck S. & Barrell, B. G. (1998) Nature (London) 331, 269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomasec P., Braud, V. M., Rickards, C., Powell, M. B., McSharry, B. P., Gadola, S., Cerundolo, V., Borysiewicz, L. K., McMichael, A. J. & Wilkinson, G. W. G. (2000) Science 287, 1031-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulbrecht M., Modrow, S., Srivastava, R., Peterson, P. E. & Weiss, E. H. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 4375-4385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacasova R., Martinozzi, S., Boulouis, H. J., Ulbrecht, M., Vieville, J. C., Sigaux, F., Weiss, E. H. & Pla, M. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 5190-5196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ugolini S., Arpin, C., Anfossi, N., Walzer, T., Cambiaggi, A., Forster, R., Lipp, M., Toes, R. E., Melief, C. J., Marvel, J. & Vivier, E. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 430-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young N. T. & Uhrberg, M. (2002) Trends Immunol. 23, 71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mingari M. C., Vitale, C., Cambiaggi, A., Schiavetti, F., Melioli, G., Ferrini, S. & Poggi, A. (1995) Int. Immunol. 7, 697-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda H., Lethé, B., Lehmann, F., Van Baren, N., Baurain, J. F., De Smet, C., Chambost, H., Vitale, M., Moretta, A., Boon, T. & Coulie, P. G. (1997) Immunity 6, 199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speiser D. E., Valmori, D., Rimoldi, D., Pittet, M. J., Lienard, D., Cerundolo, V., MacDonald, H. R., Cerottini, J. C. & Romero, P. (1999) Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 1990-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra N., Guillard, M., Angevin, E., Echchakir, H., Escudier, B., Moretta, A., Chouaib, S. & Caignard, A. (2000) Blood 95, 2883-2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gati A., Guerra, N., Giron-Michel, J., Azzarone, B., Angevin, E., Moretta, A., Chouaib, S. & Caignard, A. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 3240-3244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vely F., Peyrat, M., Couedel, C., Morcet, J., Halary, F., Davodeau, F., Romagne, F., Scotet, E., Saulquin, X., Houssaint, E., et al. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 2487-2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geraghty D. E., Stockschleader, M., Ishitani, A. & Hansen, J. A. (1992) Hum. Immunol. 33, 174-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madelon M. M., Gould, D. S., Carroll, J., Vugmeyster, Y. & Ploegh, H. L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7437-7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggeri L., Capanni, M., Urbani, E., Perruccio, K., Shlomchik, W. D., Tosti, A., Posati, S., Rogaia, D., Frassoni, F., Aversa, F., et al. (2002) Science 295, 2097-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]