Abstract

Early assessment of heart failure during treatment can improve patient prognosis. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), uric acid (UA), pre-albumin (PA), red blood cell distribution width (RDW), and Cystatin C (Cys C) are related to the development of heart failure. This study determined whether these characteristics could serve as combined diagnostic indicators for the prognosis of New York Heart Association classification (NYHA) IV heart failure (IV-HF). Here, the general clinical and cardiac ultrasound data from 193 patients with NYHA IV-HF were collected and followed-up for six months, and their survival status was recorded. Among the patients, 119 (61.66%) survived, whereas 74 (38.34%) were reported dead at the six-month follow-up. Compared to the survival group, the death group had significantly higher age, disease duration, Cys C, UA, BNP, RDW, left ventricular end-systolic diameter, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, and left atrial dimension, and lower PA and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW had significant negative linear correlations with LVEF, while PA had a significant positive linear correlation with LVEF. In addition, high Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW, as well as low PA, are independent risk factors for mortality in patients with IV-HF. The combination of age, disease duration, RDW, and levels of Cys C, UA, BNP, and PA can serve as diagnostic indicators for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-13274-y.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Heart failure, Death, Brain natriuretic peptide

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Cardiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Heart failure impairs ejection functions of the heart, and represents the end stage of various heart diseases1. The development of heart failure is closely related to myocardial injury and change in myocardial structure and function, often due to factors such as myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, hemodynamic overload, and inflammation. Heart failure is a common condition encountered in emergency departments, with acute cases particularly marked by abrupt onset, critical severity, rapid progression, and poor prognosis2. This disease not only drastically decreases patients’ quality of life but also poses a significant threat to their survival3,4. Consequently, it remains an ongoing challenge in medicine. Early continuous monitoring and assessment of the condition during treatment are of paramount clinical importance for improving patient prognosis.

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an important biomarker of the human heart, and thus, has persistently been a focus of clinical research. Currently, it is widely used in clinical practice as an important marker for assessing ventricular contractile status and myocardial function, and utilized for diagnosis, treatment guidance, and prognostic determination of various heart diseases5. Currently, BNP is commonly used in clinical settings to evaluate the severity and prognosis of heart failure6. However, BNP level is affected by body weight, age, and renal function, and some studies indicate that BNP levels do not always correspond with the development of heart failure7–9. Therefore, BNP level has certain limitations in assessing the development of heart failure, thus highlighting the need of more sensitive indicators for evaluation.

Cystatin C (Cys C), uric acid (UA), pre-albumin (PA), and red blood cell distribution width (RDW) are related to the development of heart failure. Cys C shows a strong correlation with both cardiac structure and function as well as BNP levels in patients with systolic heart failure. Moreover, it proved to be a more valuable marker than creatinine and BNP for assessing the severity of heart failure10. Higher UA level is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization due to heart failure11. The decrease in PA levels is closely related to poor prognosis in older patients with chronic heart failure and acts as a biomarker in clinical assessment to guide treatment and improve prognosis12. RDW is significantly higher in patients with acute and chronic heart failure than that in the normal population and may serve as a diagnosis biomarker in the patient population13. The combination of RDW, Cys C, and BNP can serve as a serum biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure14–16. However, there is a lack of relevant studies on whether BNP, Cys C, PA levels, and RDW can serve as combined diagnostic biomarkers for New York Heart Association classification (NYHA) IV heart failure (IV-HF).

Therefore, this study measured the levels of Cys C, PA, RDW, and BNP in patients with NYHA IV-HF and followed-up on their prognosis to determine whether these biomarkers can serve as diagnostic indicators for the prognosis of NYHA IV-HF. The study may provide valuable insights into the relationship between BNP, Cys C, and PA levels and RDW in patients with heart failure. These connections can enhance the understanding of the potential pathophysiological mechanisms of heart failure and may help in developing more accurate diagnostic and prognostic markers.

Methods

Study design

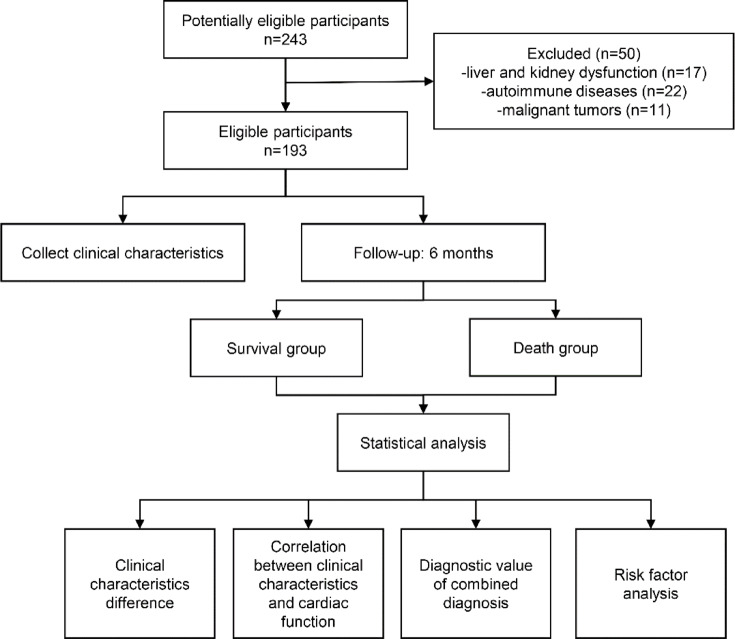

The flowchart of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 243 patients with NYHA IV-HF were included in this retrospective study from the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2020 and January 2024. NYHA IV-HF refers to patients with heart failure who are unable to engage in any physical activity and exhibit symptoms of heart failure even in a resting state, which worsen after any physical activity. All patients were hospitalized at the electronic intensive care unit (EICU). This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Approval No. 2020-R643). Inclusion criteria were the following: NYHA IV-HF caused by various etiologies, including acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary heart disease, valvular heart disease, septic cardiomyopathy, and viral myocarditis. The exclusion criteria were: liver and kidney dysfunction (17 patients), autoimmune diseases (22 patients), and malignant tumors (11 patients). Finally, a total of 193 patients were included in the study. The specific criteria of liver function dysfunction was total bilirubin > 3.0 mg/dL and kidney dysfunction measured by GFR < 30 mL/min. Upon liver dysfunction, PA synthesis is reduced, leading to decreased PA levels. In renal insufficiency, increased permeability of the glomerular filtration membrane may cause the loss of PA via urine, resulting in decreased PA levels. RDW values may be decreased under the condition of renal dysfunction. In patients with renal insufficiency, the excretion of CysC is decreased, which leads to an elevated serum level; moreover, the metabolism of BNP is slowed, which may cause a spurious increase in BNP levels. In addition, in patients with autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation can suppress hepatic PA synthesis, leading to decreased PA, or may stimulate Cys C production in nucleated cells, increasing its level. All patients with heart failure were treated according to the “Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure 2018”17. Treatment was tailored to the specific etiology. Medications were chosen based on factors such as blood pressure, heart rate, renal function, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and comorbidities, and included diuretics, ACEIs, ARBs, ARNI, β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, sodium-dependent glucose transporters 2, and digitalis agents. Non-pharmacological therapies such as IABP, mechanical ventilation, CRRT, and ECMO were also used as appropriate.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the experimental design.

Clinical characteristics

General clinical data were collected from all patients, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol history, disease duration, and past medical history. In addition, fasting venous blood was drawn at the first day of admission to EICU for blood routine examination and to measure Cys C, PA, RDW, and BNP levels. Cardiac ultrasound was used to measure LVEF, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVDd), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVDs), and left atrial dimension (LAD). Blood routine examination was performed by the electrical impedance method using UniCel DxH 800 (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA). Cys C and PA were measured by the latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetry method using Cobas 8000 Automated Biochemical Analyzer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). BNP was measured by rapid immunofluorescence assay using SSJ-2 multi-functional immunoassay analyzer (RELIA, Shanghai, China).

Follow-up

All patients were followed up for six months and their survival status was recorded. Based on the survival status, the patients were divided into the death and survival groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the quantitative variables. Data that did or did not follow the normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as median with interquartile range. The differences in clinical parameters between the two groups were compared using the student’s t or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages, and differences were tested using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. The correlation between differential clinical characteristics and cardiac function indicators was analyzed by Spearman correlation analysis. The correlation between differential clinical characteristics and LEVF was analyzed by simple linear regression analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic significance of clinical indicators for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF, and the diagnostic ability was quantified using the area under the ROC curve (AUC). An AUC of 0.7–0.8 was considered acceptable, 0.8–0.9 as good, and > 0.9 as excellent. In this study, clinical parameters with significant differences were selected for the model construction. Two modeling approaches were employed: logistic and LASSO regression analyses. Subsequently, four models were constructed by combining different clinical parameters with logistic and LASSO regression analyses. By comparing the diagnostic performance of these four models, the optimal diagnostic model was identified. The combined diagnostic model 1 (Model 1) was established by the logistic regression analysis of Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW. The combined diagnostic model 2 (Model 2) was established by the logistic regression analysis of age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW. The combined diagnostic model 3 (Model 3) was established by the LASSO regression analysis of Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW. Lastly, the combined diagnostic model 4 (Model 4) was established by LASSO regression analysis of age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW. Variables with significant differences were chosen for univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, which were conducted to identify the risk factors for mortality. Survival analysis was conducted using Logrank regression analysis. Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison corrections were used the p.adjust function in R language (version 3.5.1).

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study population

Among the 193 patients with NYHA IV-HF, 119 (61.66%) survived, while 74 (38.34%) died at follow-up after six months (Tables 1 and 2). Compared to the survival group, the death group had significantly higher age, disease duration, and levels of Cys C, BNP, PA, RDW, and UA. Furthermore, LVDs, LVDd, and LAD were significantly higher and LVEF was significantly lower in the death group than in survival group. However, other clinical characteristics showed no significant difference between the survival and death groups. Additionally, Renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, sodium-dependent glucose transporters 2, and diuretics treatment had no significant change between alive and death groups. Digitalis agents, IABP, mechanical ventilation, CRRT and ECMO treatment were significantly increased in death group.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with NYHA IV-HF.

| Characteristics | Alive (n = 119) | Death (n = 74) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVDs (mm) | 34.00 (30.00, 38.00) | 39.50 (36.00, 42.00) | < 0.001* |

| LVDd (mm) | 43.00 (40.00, 45.00) | 5050 (45.75, 54.00) | < 0.001* |

| LAD (mm) | 28.00 (27.00, 29.00) | 29.00 (27.00, 30.00) | 0.0270* |

| LVEF (%) | 38.00 (32.00, 43.00) | 23.00 (19.00, 28.00) | < 0.001* |

| Renin-angiotensin system inhibitor | 119 | 74 | > 0.999 |

| β-blockers | 119 | 74 | > 0.999 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, | 119 | 74 | > 0.999 |

| Sodium-dependent glucose transporters 2 | 119 | 74 | > 0.999 |

| Diuretics | 119 | 74 | > 0.999 |

| Digitalis agents | 24 | 37 | < 0.001* |

| IABP | 21 | 23 | 0.031* |

| Mechanical ventilation | 17 | 22 | 0.009* |

| CRRT | 11 | 15 | 0.029* |

| ECMO | 5 | 13 | 0.004* |

*P < 0.05; Renin-angiotensin system inhibitor including ACEIs, ARBs, and ARNI.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with NYHA IV-HF.

| Characteristics | Alive (n = 119) | Death (n = 74) | P.adj |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cys C (mg/L) | 1.42 (1.24, 1.58) | 1.86 (1.35, 2.12) | 0.001* |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 465.0 (292.0, 693.0) | 695.3 (536.3, 909.3) | 0.001* |

| PA (g/L) | 0.20 (0.15, 0.24) | 0.15 (0.08, 0.17) | 0.001* |

| RDW (%) | 14.59 (13.74, 15.36) | 16.83 (14.92, 20.23) | 0.001* |

| Age (year) | 47.51 ± 16.01 | 55.39 ± 15.16 | 0.005* |

| UA (µmol/L) | 260.0 (215.0, 321.0) | 297.0 (254.8, 338.0) | 0.005* |

| Disease course (day) | 14.00 (6.00, 23.00) | 18.00 (8.75, 30.00) | 0.044* |

| Red blood cell (×109/L) | 4.20 (3.80, 4.70) | 4.20 (3.88, 4.23) | 0.233 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.90 (1.62, 2.18) | 1.86 (1.35, 2.16) | 0.307 |

| Smoking history [Yes, n (%)] | 44 | 36 | 0.307 |

| Low density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 2.82 (2.45, 3.21) | 2.87 (2.49, 3.37) | 0.307 |

| White blood cell (×109/L) | 11.90 (10.90, 12.90) | 12.20 (11.10, 13.50) | 0.351 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 6.00 (4.80, 6.90) | 5.60 (4.58, 6.70) | 0.351 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 30.00 (28.00, 32.00) | 31.00 (29.00, 33.00) | 0.359 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 39.00 (37.00, 42.00) | 38.00 (37.00, 41.00) | 0.422 |

| Hyperlipidemia [Yes, n (%)] | 5 | 7 | 0.422 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.00 (38.00, 47.00) | 42.00 (38.00, 45.00) | 0.452 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 116.0 (107.0, 124.0) | 115.0 (104.0, 124.0) | 0.586 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 21.00 (18.00, 23.00) | 20.00 (17.00, 22.00) | 0.619 |

| Diabetes [Yes, n (%)] | 35 | 26 | 0.619 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 69.00 (59.00, 79.00) | 69.00 (63.00, 78.50) | 0.619 |

| HBA1C (%) | 5.80 (5.40, 6.50) | 5.90 (5.50, 6.40) | 0.716 |

| How density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 1.42 (1.25, 1.60) | 1.46 (1.27, 1.60) | 0.744 |

| Gender [Male, n (%)] | 66 | 43 | 0.880 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 137.0 (134.0, 140.0) | 138.0 (134.0, 140.0) | 0.880 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fl.) | 90.00 (87.00, 94.00) | 91.00 (87.00, 93.00) | 0.880 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (g/L) | 335.0 (325.0, 343.0) | 334.5 (326.0, 345.0) | 0.901 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 220.0 (165.0, 265.0) | 229.5 (165.5, 3257.3) | 0.910 |

| Hypertension [Yes, n (%)] | 50 | 32 | 0.910 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.50 (22.00, 24.80) | 23.20 (22.00, 25.10) | 0.910 |

| Drinking history [Yes, n (%)] | 46 | 28 | 0.910 |

*P < 0.05.

Correlation between clinical characteristics and cardiac function

We analyzed the correlation between differential clinical characteristics and cardiac function indicators (Fig. 2A). The results show that Cys C had significant correlation with BNP, PA, and RDW; UA had significant correlation only with BNP; BNP was significantly correlated with Cys C, UA, PA, and RDW; PA was significantly correlated with Cys C, BNP, and RDW; and RDW was significantly correlated with Cys C, BNP, and PA. The results also indicated that Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW had significant correlations with LVDs, LVDd, and LVEF; however, there was no correlation with LAD. We further analyzed the linear correlation between differential clinical characteristics and LVEF (Fig. 2B). The results showed that Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW had a significant negative linear correlation with LVEF, while PA had a significant positive linear correlation with LVEF.

Fig. 2.

Differential clinical characteristics are significantly correlated with cardiac function indicators. A The correlation between differential clinical characteristics and cardiac function indicators was analyzed by Spearman correlation analysis. B The correlation between differential clinical characteristics and LEVF was analyzed by simple linear regression analysis.

Diagnostic value of combined diagnosis in patients who died from heart failure

ROC analysis was performed individually for age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. The results showed that RDW had the best diagnostic performance, followed by Cys C and PA (Fig. 3A). The ROC results of Model 1 (including Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW), Model 2 (including age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW), Model 3 (including Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW), and Model 4 (including age, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW) are shown in Fig. 3B and E. Further, the optimal cut-off values, sensitivities, and specificities are shown in Table 3. The diagnostic effectiveness, measured by the AUC, from highest to lowest, was as follows: Model 2, Model 4, Model 1, and Model 3. Overall, the performance of combined diagnosis was superior to that of each individual diagnosis. The above results indicate that the combination of these biomarkers can improve diagnostic accuracy, with Model 2 showing the best performance. During the 6-month follow-up period, only 34 patients had clear records of survival time among the 74 patients in the death group. Consequently, survival analysis was conducted only on all patients in the survival group and the 34 patients in the deceased group. In the analysis, patients were categorized into two groups based on the cutoff values of each model: those with values below the cutoff were assigned to the low group, and those with values equal to or above the cutoff were assigned to the high group. The results indicated that patients in the high group had significantly shorter survival times compared to those in the low group (Fig. S1). Among the models evaluated, Model 2 and Model 4 demonstrated the most satisfactory predictive performance.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation and validation of the prediction model. A ROC curve of age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. B ROC curve of Model 1 (including Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW) to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. Logistic regression analysis was performed for predictors and associated characteristics. C ROC curve of Model 2 (including age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW) to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. Logistic regression analysis was performed for predictors and associated characteristics. D ROC curve of Model 3 (including Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW) to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. LASSO regression analysis was performed for predictors and associated characteristics. E ROC curve of Model 4 (including age, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW) to diagnose the patients who died from heart failure. LASSO regression analysis was performed for predictors and associated characteristics.

Table 3.

Diagnostic value of individual and combined parameters for patients who died from heart failure.

| Characteristics | AUC | Confidence interval | Cut-off value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.658 | 0.580–0.736 | 49.500 | 0.662 | 0.588 |

| Disease course | 0.61 | 0.526–0.693 | 28.500 | 0.284 | 0.958 |

| Cys C | 0.752 | 0.675–0.829 | 1.735 | 0.595 | 0.941 |

| UA | 0.645 | 0.567–0.722 | 261.500 | 0.743 | 0.504 |

| BNP | 0.736 | 0.664–0.807 | 518.000 | 0.784 | 0.588 |

| PA | 0.751 | 0.682–0.819 | 0.185 | 0.878 | 0.563 |

| RDW | 0.772 | 0.696–0.847 | 15.980 | 0.635 | 0.933 |

| Model 1 | 0.897 | 0.847–0.948 | 0.098 | 0.797 | 0.941 |

| Model 2 | 0.907 | 0.858–0.955 | −0.256 | 0.838 | 0.933 |

| Model 3 | 0.897 | 0.846–0.948 | 0.072 | 0.797 | 0.950 |

| Model 4 | 0.902 | 0.853–0.951 | −0.218 | 0.824 | 0.933 |

Risk factor analysis for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that higher age, disease course, Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW, as well as low PA, were risk factors for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF (Table 4). Further, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that high Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW, as well as low PA, were independent risk factors for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of characteristics associated with mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF.

| Characteristics | B | SE | Wals χ2 | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.032 | 0.01 | 10.487 | 0.001 | 1.032 (1.013–1.052) |

| Disease course | 0.02 | 0.01 | 4.272 | 0.039 | 1.02 (1.001–1.040) |

| Cys C | 3.088 | 0.530 | 33.945 | < 0.001 | 21.933 (7.762–61.981) |

| UA | 0.01 | 0.003 | 11.467 | 0.001 | 1.01 (1.004–1.015) |

| BNP | 0.004 | 0.001 | 29.38 | < 0.001 | 1.004 (1.002–1.005) |

| PA | −1.634 | 0.297 | 30.201 | < 0.001 | 0.195 (0.109–0.350) |

| RDW | 0.401 | 0.076 | 27.897 | < 0.001 | 1.494 (1.287–1.734) |

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of characteristics associated with mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF.

| Characteristics | B | SE | Wals χ2 | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.024 | 0.014 | 2.914 | 0.088 | 1.024 (0.997–1.052) |

| Disease course | 0.017 | 0.01 | 3.208 | 0.073 | 1.017 (0.998–1.037) |

| Cys C | 1.992 | 0.62 | 10.312 | 0.001 | 7.334 (2.174–24.745) |

| UA | 0.012 | 0.004 | 8.048 | 0.005 | 1.012 (1.004–1.020) |

| BNP | 0.003 | 0.001 | 10.655 | 0.001 | 1.003 (1.001–1.005) |

| PA | −0.764 | 0.381 | 4.029 | 0.045 | 0.466 (0.221–0.982) |

| RDW | 0.25 | 0.085 | 8.724 | 0.003 | 1.284 (1.088–1.515) |

Discussion

The pathophysiology of heart failure is complex and its prognosis is poor. In patients with NYHA IV-HF, the condition can significantly worsen over time, potentially leading to death. Early identification of the risk level in patients is crucial for improving their prognosis. This study collected data from 193 patients with NYHA IV-HF. Among them, 119 (61.66%) survived, while 74 (38.34%) died at follow-up after six months. Compared to the survival group, the death group had significantly higher age, disease duration, Cys C, UA, BNP, RDW, LVDs, LVDd, and LAD, and lower PA and LVEF. Digitalis agents, IABP, mechanical ventilation, CRRT and ECMO treatment were significantly increased in death group, and the reasons are closely related to the severity of the disease. Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW had a significant negative linear correlation with LVEF, while PA had a significant positive linear correlation with LVEF. The combination of age, disease duration, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW can improve diagnostic accuracy for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF. Survival analysis also showed the same results. In addition, high Cys C, UA, BNP, and RDW, as well as low PA, are independent risk factors for mortality in patients with NYHA IV-HF. This study provides a new method for assessing mortality risk by analyzing the combination of multiple biomarkers, which can effectively improve the diagnostic accuracy of mortality risk in patients with NYHA IV-HF, showing great clinical application potential.

Cys C is a cysteine proteinase inhibitor that is not significantly correlated with factors such as sex, age, or acute reactions, and has stable levels in the body18,19. Cys C has strong collagen fiber degradation activity; when serum Cys C levels increase, the breakdown of collagen in the body decreases while its production increases, leading to accumulation around myocardial cells. This results in myocardial cell remodeling, reduced myocardial compliance, and ultimately, damage to heart function20. Serum Cys C levels are significantly higher in patients with heart failure compared to those with normal heart function or mild heart failure, and they increase with the worsening of heart failure severity. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-calculated eGFR is an independent predictor of mortality in these patients and is more accurate than the value obtained from the CKD-EPI formula21. However, the eGFR calculated using the CKD-EPI/Cys C equation improves the mortality risk stratification based on the CKD-EPI formula22. UA is the final product of purine metabolism in the human body and closely associated with the incidence and progression of heart failure23. Higher UA level is related to the increased risk of heart failure and related all-cause mortality24,25. PA is closely related to the overall nutritional status of patients and plays a role in immune modulation during stress, infection, and inflammatory responses26,27. Heart failure leads to malabsorption, liver dysfunction, and insufficient synthesis of prealbumin, while renal dysfunction causes increased urinary protein excretion, increased secretion of systemic inflammatory factors, and stress responses, further decreasing serum PA levels28,29. RDW reflects the uniformity of red blood cell size. An increased RDW indicates greater variation in red blood cell size, often associated with increased production of ineffective or abnormal red blood cells. RDW is strongly associated with systemic inflammation and is a prognostic marker for atrial fibrillation recurrence, heart failure, and cardiovascular diseases30,31. RDW is a useful laboratory indicator for early diagnosis of diabetes complicated by heart failure and is positively correlated with inpatient mortality32,33. RDW is an independent predictor of the risk of rehospitalization, as well as short-term, medium-term, and long-term mortality in heart failure34,35. RDW levels can also serve as an indicator of disease severity in heart failure, with higher RDW levels indicating more severe disease and greater risk of death. These studies suggested that Cys C, UA, PA, and RDW levels are significantly changed during the development of heart failure, which contribute to the diagnosis and prognosis of the condition. Similarly, this study found that Cys C, UA, PA, and RDW were significantly different between surviving patients and those succumbed to NYHA IV-HF, suggesting them as independent risk factors for mortality in these patients.

Currently, BNP level is commonly used in clinical practice to assess the severity and prognosis of heart failure6. However, its use has certain limitations7–9. Some studies have used BNP in combination with other biomarkers to predict the prognosis of heart failure14,36–38. Research indicates that the combination of BNP, the estimated plasma volume status (ePVS), hydration status assessed by bioimpedance vector analysis (BIVA), and the blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio (BUN/Cr) can effectively account for 40% of the mortality risk in patients with heart failure, which is significantly higher than that achieved by individual predictors39. The above study indirectly suggests that combined prediction can better assess the prognosis of patients with heart failure. Unlike the above study, the research participants of this study were patients with NYHA IV-HF, not AHF and CHF. Therefore, the selected key diagnostic indicators are also different. This study aimed to analyze various biomarkers and baseline characteristics (including age, disease duration, BNP, Cys C, UA, PA, and RDW) to evaluate whether their combination can serve as an effective diagnostic indicator for the risk of death in patients with NYHA IV-HF. The results show that the selected combination of biomarkers demonstrates excellent diagnostic performance in identifying the risk of death in NYHA IV-HF, outperforming BNP alone. This approach will not only aid clinicians in developing personalized treatment plans but also provide a strong basis for the follow-up management of patients.

The limitations of this study are mainly reflected in the small sample size and the lack of support from larger-scale clinical data. Owing to the small sample size, we constructed multiple prediction models on the same experimental set for analysis and found the best prediction model. Therefore, we did not have extra samples as validation sets for cross or external validation. Furthermore, the absence of multi-center data may lead to insufficient representativeness of the study results, limiting their applicability in broader clinical settings, and may also increase the risk of bias, affecting the credibility and generalizability of the conclusions. Additionally, the design of this study did not include a complete set of outcome measures, which may impact the external validity of the results. Furthermore, the patients were followed-up six months after discharge. However, the majority of the deceased patients’ families refused to disclose the exact time of death; thus, the specific time of death remains unknown. Therefore, Cox regression could not be used for analysis in this study. Finally, although we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of biomarkers in patients with heart failure, potential batch variations in the data could affect the reliability of the results.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the clinical characteristics and biomarkers of patients with class IV heart failure, proposing a new integrated assessment model to provide a basis for early identification of patients at risk of death. The results suggest that the combination of age, disease duration, Cys C, UA, BNP, PA, and RDW can effectively improve the diagnostic accuracy of death risk. Although the sample size of this study is relatively small and lacks clinical validation, our findings provide important evidence for the early identification of and intervention for patients with heart failure. Future work should focus on validating the applicability of these biomarkers in different populations and exploring the implementation of individualized intervention strategies to improve the prognosis of heart failure.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- Cys C

Cystatin C

- UA

Uric acid

- PA

Pre-albumin

- LVDd

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

- IV-HF

IV Heart failure

- RDW

Red blood cell distribution width

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- LAD

Left atrial dimension

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- LVDs

Left ventricular end-systolic diameter

Author contributions

YM and HC participated in the design of the study, clinical sample collection, and statistical analysis; YD, YG, and YA participated in clinical sample collection and bioinformatics analyses; YM wrote the draft manuscript; and HC revised the final draft of the manuscript. All authors agreed to the publication of the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Peking union medical foundation-Ruiyi Emergency Medical Research Fund (No. 22222012010) and the Medical Science Research Project of Hebei (No. 20211690).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the published article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was obtained with the approval of the ethics committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Approval No. 2020-R643) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University waived the need for informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Heidenreich, P. A. et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation145, e876–e894 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang, S. et al. Burden and Temporal trends of valvular heart disease-Related heart failure from 1990 to 2019 and projection up to 2030 in group of 20 countries: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Am. Heart Assoc.13, e036462 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, Y. et al. Psychosomatic mechanisms of heart failure symptoms on quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A multi-centre cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs.33, 1839–1848 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao, Y. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the chronic heart failure Health-related quality of life questionnaire (CHFQOLQ-20). Sci. Rep.14, 24713 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otsuka, Y. et al. BNP level predicts bleeding event in patients with heart failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Open. Heart. 10, e002489 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrannini, G. et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations, testing and associations with worsening heart failure events. ESC Heart Fail.11, 759–771 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rus, M. et al. B-Type natriuretic Peptide-A paradox in the diagnosis of acute heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in obese patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 14, 808 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsutsui, H. et al. Natriuretic peptides: role in the diagnosis and management of heart failure: A scientific statement from the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology, heart failure society of America and Japanese heart failure society. J. Card Fail.29, 787–804 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthelot, E. et al. Setting the optimal threshold of NT-proBNP and BNP for the diagnosis of heart failure in patients over 75 years. ESC Heart Fail.11, 3232–3241 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge, J. et al. Correlation between Cystatin C and the severity of cardiac dysfunction in patients with systolic heart failure. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. 16, 2419–2426 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, L., Chang, Y., Li, F. & Yin, Y. Relationship between serum uric acid levels and uric acid Lowering therapy with the prognosis of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.11, 1403242 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi, L. et al. Application of blood pre-albumin and NT-pro BNP levels in evaluating prognosis of elderly chronic heart failure patients. Exp. Ther. Med.20, 1337–1342 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang, H. N. N. et al. Assessing red blood cell distribution width in Vietnamese heart failure patients: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 19, e0301319 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, R. & Gao, C. Clinical value of combined plasma brain natriuretic peptide and serum Cystatin C measurement on the prediction of heart failure in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res.56, e12910 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasoe, S., Kubozono, T., Ojima, S., Miyata, M. & Ohishi, M. Combined assessment of the red cell distribution width and B-type natriuretic peptide: A more useful prognostic marker of cardiovascular mortality in heart failure patients. Intern. Med.57, 1681–1688 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A RS: Red cell distribution width and serum BNP level correlation in diabetic patients with cardiac failure: A Cross - Sectional study. J Clin. Diagn. Res.8, Fc01–03. (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chinese guidelines for the. Diagnosis and treatment of heart failure 2018. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 46, 760–789 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ding, L., Liu, Z. & Wang, J. Role of Cystatin C in urogenital malignancy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1082871 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lalmanach, G. et al. Human Cystatin C in fibrotic diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta. 565, 120016 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Calvo, J. I., Morales Rull, J. L. & Ruiz Ruiz, F. J. [Cystatin C: a protein for heart failure]. Med. Clin. (Barc). 136, 158–162 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scicchitano, P. et al. The prognostic impact of estimated creatinine clearance by bioelectrical impedance analysis in heart failure: comparison of different eGFR formulas. Biomedicines9, 1307 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheang, I. et al. Cystatin C-based CKD-EPI estimated glomerular filtration rate equations as a better strategy for mortality stratification in acute heart failure: A STROBE-compliant prospective observational study. Med. (Baltim).99, e22996 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin, M. J., Zou, S. B. & Zhu, B. X. Effect of Dapagliflozin on uric acid in patients with chronic heart failure and hyperuricemia. World J. Clin. Cases. 12, 3468–3475 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin, S., Xiang, M., Gao, L., Cheng, X. & Zhang, D. Uric acid is a biomarker for heart failure, but not therapeutic target: result from a comprehensive meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail.11, 78–90 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, Z., Yuan, J., Hu, E. & Wei, D. Relation of serum uric acid levels to readmission and mortality in patients with heart failure. Sci. Rep.13, 18495 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan, L. et al. Serum Pre-Albumin predicts the clinical outcome in metastatic Castration-Resistant prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone. J. Cancer. 8, 3448–3455 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lourenço, P. et al. Does pre-albumin predict in-hospital mortality in heart failure? Int. J. Cardiol.166, 758–760 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, X. et al. The impact of urinary albumin-creatinine ratio and glomerular filtration rate on long-term mortality in patients with heart failure: the National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2018. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis.34, 1477–1487 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao, S. & Wang, X. Relationship between enteral nutrition and serum levels of inflammatory factors and cardiac function in elderly patients with heart failure: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim).100, e25891 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García-Escobar, A. et al. Red blood cell distribution width is a biomarker of red cell dysfunction associated with high systemic inflammation and a prognostic marker in heart failure and cardiovascular disease: A potential predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev.31, 437–449 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Targoński, R., Sadowski, J., Starek-Stelmaszczyk, M., Targoński, R. & Rynkiewicz, A. Prognostic significance of red cell distribution width and its relation to increased pulmonary pressure and inflammation in acute heart failure. Cardiol. J.27, 394–403 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, K. et al. Association between red blood cell distribution width and In-Hospital mortality among congestive heart failure patients with diabetes among patients in the intensive care unit: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care Res. Pract.2024, 9562200 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pang, J., Qian, L. Y., Lv, P. & Che, X. R. Application of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and red blood cell distribution width in diabetes mellitus complicated with heart failure. World J. Diabetes. 15, 1226–1233 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, L. et al. Prognostic value of RDW alone and in combination with NT-proBNP in patients with heart failure. Clin. Cardiol.45, 802–813 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu, F., Wu, H., Jin, X., Kong, C. & Zhao, W. Association of red cell distribution width with the risk of 3-month readmission in patients with heart failure: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10, 1123905 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu, D. & Zhou, J. The relationship between peripheral blood soluble ST2, BNP levels, cardiac function, and prognosis in patients with heart failure. Am. J. Transl Res.15, 2878–2884 (2023). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan, A., Shah, M. H., Khan, S., Shamim, U. & Arshad, S. Serum uric acid level in the severity of congestive heart failure (CHF). Pak J. Med. Sci.33, 330–334 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang, H. J. et al. Usefulness of red blood cell distribution width to predict heart failure hospitalization in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int. Heart J.59, 779–785 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massari, F. et al. Multiparametric approach to congestion for predicting long-term survival in heart failure. J. Cardiol.75, 47–52 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the published article.