Background

This systematic review investigates experimental and repurposed antiviral molecules for epidemic-potential arboviruses, including dengue (DENV), Zika (ZIKV), chikungunya (CHIKV), West Nile (WNV), and Usutu (USUV) viruses. Arboviral diseases pose a growing public health concern, exacerbated by climate change and increased global travel. Despite the absence of approved antiviral therapies for most arboviruses, numerous in vitro, in vivo and in human studies have evaluated candidate molecules targeting the different stages of viral replication. Methods: Our methods adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Pubmed, Embase, and Cochrane Library trials were searched. Studies published until March 2024 were included. After abstract review and duplication removal, full-text articles were obtained for further review, reviewed by two independent reviewers, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Results: Our analysis, based on 185 studies, highlights the antiviral role of molecules such as nucleoside analogs, protease inhibitors, and immune-modulators. No studies conducted in humans have been reported to demonstrate the antiviral efficacy of any molecule. Favipiravir, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir demonstrated viremia reduction and symptoms improvement in vitro and in vivo experiments. Cholesterol-lowering agents, such as atorvastatin and ezetimibe, showed promise in disrupting viral assembly. Montelukast and doxycycline exhibited anti-inflammatory effects, contributing to improved clinical outcomes. The cytokine modulation profiles varied, with notable reductions in pro-inflammatory markers in certain studies. Conclusions: Currently, there are no studies in humans demonstrating effective treatments against arboviral infections. Although some molecules have shown efficacy in reducing viral titters, further clinical evaluation of promising candidates and the exploration of combination therapies targeting viral replication and host immune-response are needed.

Keywords: Antiviral treatment, Antiviral therapy, Arbovirus, Arboviruses, West nile, WNV, Dengue, DENV

1. Introduction

Arboviral human diseases are a group of several viral disease transmitted by arthropods (especially mosquitoes) that includes the following viruses: Zika (ZIKV), West Nile Virus (WNV), Dengue (DENV), Chikungunya (CHIKV), and Usutu (USUV) [1]. These emerging diseases have a global distribution and significantly influence public health. Autochthonous transmission of Zika has been recorded in 87 countries [2], and dengue incidence is estimated at 390 million cases [3]. The incidence of arboviral diseases is increasing, with a growing number of cases occurring in non-endemic countries due to increased migration, international travel and the expansion of vectors into areas where they were previously absent [4]. Climate change facilitates the proliferation of vectors in climatic regions that were previously exposed only to imported cases and not to endemic circulation, making these areas ecologically suitable for vector reproduction [5]. For this reason, managing arboviral diseases requires a "One Health" approach, which involves understanding the transmission dynamics of infectious agents because of ecological changes and adopting health policies that include combating climate change [6].

Clinical manifestations can range from mild to severe, including symptoms such as fever, skin rash, and muscle or joint pain. In more serious cases, these infections may lead to significant neurological complications, such as encephalitis [7].

For instance, viruses like WNV, ZIKV and CHIKV are known to cause neuroinvasive disease, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, presenting as meningitis or encephalitis, both of which can result in long-term neurological deficits [8]. WNV neuroinvasive diseases (WNND) is one of the most frequent neurological disease caused by arboviruses and its incidence is rising in Europe as experimented in Italy in 2018 season (577 human cases of WNV infection, 230 WNND and 42 WNV-attributed deaths) [9]. Arboviral diseases can lead to permanent disability or death [10]. One of the most severe clinical manifestations of arbovirus infections, such as dengue, is the development of hemorrhagic fever accompanied by severe thrombocytopenia and spontaneous bleeding in internal organs.

[11] This condition, historically known as Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF), is frequently marked by increased vascular permeability, leading to plasma leakage and hypovolemia, which can result in a shock syndrome (also formerly known as Dengue Shock Syndrome, DSS) and may be fatal. These two clinical conditions (DHF and DSS) are currently combined into the more current definition of “severe dengue” [12].

Currently, no specific treatment is approved for human arboviral diseases. Vaccines are commercially available only for certain arboviral diseases, with the most well-known example being the vaccine against yellow fever (YF) or against Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE), and Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV). However, these diseases are not discussed in this review. More recently, two vaccines have been approved for CHIKV and DENV. The first vaccine against Chikungunya virus, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2023 and represents a milestone in the fight against a mosquito-borne viral disease for which, until then, there was no licensed vaccine option. The vaccine is based on a recombinant platform and contains live attenuated virus designed to stimulate an effective immune response after a single dose [13].

Regarding DENV alive attenuated tetravalent vaccine against DENV was licensed in 2015 and is recommended for individuals in high transmission areas with a confirmed previous infection [14]. Finally, the FDA has recently approved a new vaccine for active prophylaxis against DENV for travelers aged four and older [15].

Other vaccines for arboviral diseases such as, Zika virus or West Nile Virus are still under development or have not yet been approved.

Disease management primarily focuses on symptoms treatment and mosquito bite prevention.Given the lack of effective treatments and the increasing incidence of arboviral diseases, it is crucial to intensify research efforts to develop new therapeutic approaches. This review aims to investigate experimental pharmacological treatments conducted through in vitro or in vivo experiments on a group of epidemic-prone arboviral diseases (defined as having an R0 > 2 [16] and present on at least three continents), assessing their potential and treatment efficacy [[17], [18], [19]].

2. Materials and methods

Our methods adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [20]. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (Registration ID: CRD42024542194) on May 1, 2024, and last modified on May 13, 2024.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

We included articles on potential chemical and pharmacological compounds for arboviral diseases. We considered randomised clinical trials (RCTs), prospective studies, retrospective studies, case series, or case reports published in peer-reviewed medical journals regarding antiviral treatment for arboviral infections with epidemic potential (R0 >2) and presence in at least three continents [21] and with an R0 >2. We included studies analysing the antiviral potential of DENV, ZIKV, CHIKV, WNV, and USUV. We considered studies analysing the antiviral potential in silico, in vitro, and in vivo of dengue (R0 = 4.74), Zika virus (R0 = 3.02), chikungunya (R0 = 2.55) [19], West Nile virus and Usutu virus (R0 extremely variable due to the presence of intermediate hosts (birds)) [17,18]. Preclinical analyses, including in vitro and in vivo studies, assessing experimental novel drugs or repurposed old drugs, were also considered. We excluded non-English articles, pre-prints, reviews, short communications, letters to the editor, conference articles, viewpoints, commentaries, or other non-peer-reviewed analysis.

2.2. Information sources and search strategy

We searched PubMed and Cochrane Controlled Trials (last accessed March 2024) with assistance from a professional medical librarian. Search terms included combinations of "zika," "dengue," "chikungunya," "west nile," "usutu," and "antiviral treatment," "antiviral agents," or "antiviral therapy." The search was limited to titles and abstracts without a time window.

2.3. Selection and data collection

A team of six resident doctors and professors in infectious and tropical diseases at the University of Brescia decided on the inclusion criteria. Another team member independently reviewed rejected manuscripts. No automated tools were used. A molecular biology expert guided the inclusion and evaluation of studies, particularly focusing on in vivo and in vitro research.

2.4. Data items

Through preliminary analysis, we excluded articles regarding the pharmacological class of phytopharmaceuticals or compounds originating from traditional medicine due to a lack of proven data on safety and clinical efficacy. We excluded in vivo experiments conducted on non-wild type mice, except mice AG126 because it is a vertebrate model for studying the mosquito vector competence for the major arboviruses of medical importance. We excluded articles not available in full text and finally extracted the following data from the included articles through full text analysis. For each selected article, we collected the study type (in silico, in vitro, in vivo, in human, or a combination), arbovirus and strain, cell cultures, animal species, animal tissues, molecules tested (repurposed or experimental), mechanism of action, route of administration, dose, administration timing, adverse drug reactions, and descriptive outcomes (efficacy, mortality rate, reduction in viral titters, laboratory techniques). Cytokine kinetics analysis was included if possible.

2.5. Synthesis methods

Results were collected in tables by arbovirus type, aggregated by study type (in vitro, in vivo, humans), and tested molecules. For in vitro studies, each molecule was listed with its effect on viral titter and cytokine kinetics. For in vivo or human studies, each molecule was listed with its effect on viral load, clinical effects, preventive or therapeutic use, and cytokine kinetics. Only a descriptive prevalence analysis was conducted due to the heterogeneity of the articles. Percentage calculations considered the number of available data items. No statistical heterogeneity or sensitivity analyses were performed.

2.6. Bias and certainty assessment

A descriptive analysis was conducted due to the heterogeneity of the articles. No methods to assess risk of bias or certainty in the evidence were used.

2.7. Study strengths and limitations

The findings of this systematic review should be seen in light of some limitations. At first, the heterogeneity of the studies restricted our review to a descriptive analysis. For this reason, it was not possible to conduct statistical analysis. Moreover, the cytokines levels were described only as increased, reduced or unchanged, without describing the entity of the variation, due to the wide heterogeneity in the methods of quantification and in the reference levels used. Finally, the selected studies were those that reported significant efficacy results.

Notwithstanding, our work has some strengths. Foremost, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first review systematically diving into the treatment of emerging arboviruses. Moreover, we recorded any additional information regarding laboratory (e.g., type of system used for analysis) and clinical (e.g., symptoms or histopathological findings) features that might prove useful for future studies. To identify possible therapeutic targets, the protective or deleterious role of the markers presented could be further investigated.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and search results

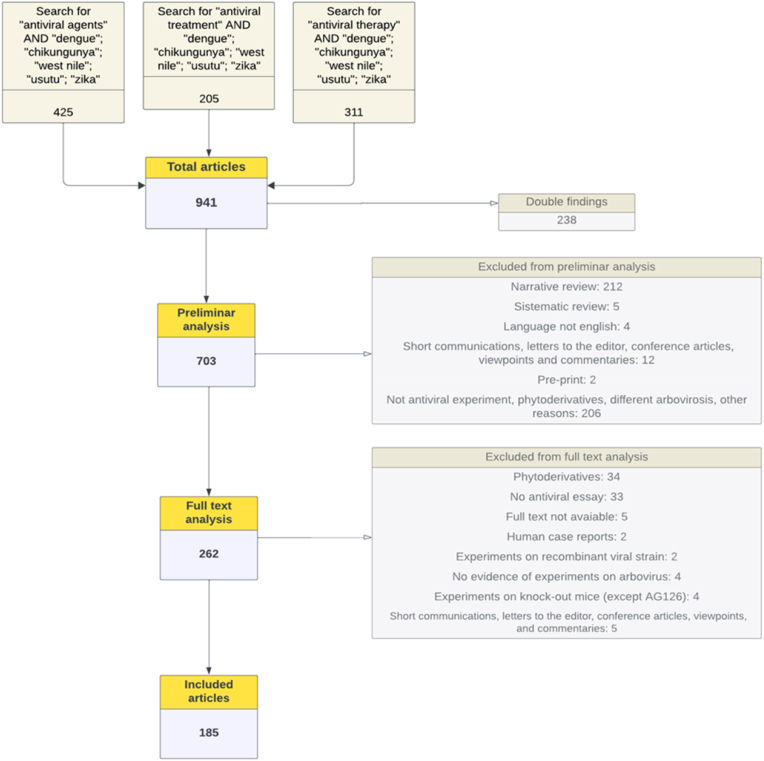

A total of 941 papers were identified through our search. We excluded 238 duplicate articles. A further 441 analyses were removed because the type of publication did not meet our inclusion criteria (most of these excluded articles were narrative reviews) or because the article did not describe an experiment regarding the efficacy of a chemical compound in the treatment of an arbovirosis in vivo, in vitro, or in humans, or finally because the compound described was a phytoderivative.

The remaining 262 articles were assessed for eligibility by a full-text analysis. The full-text analysis in this systematic review was conducted across two separate databases, with one focusing on experiments conducted in vivo or in humans, and the other on in vitro experiments. Consequently, some articles were excluded from one database for not meeting the inclusion criteria but included in the other. As a result, 77 articles were entirely excluded, while 12 articles had mixed outcomes—certain experiments within them were included (e.g., the in vivo part), while others were excluded (e.g., the in vitro part). The exclusion reasons, as previously stated, include non-conformity with study design criteria, data involving phytoderivatives, or the absence of actual experiments conducted on arbovirosis. Additional exclusions occurred due to the unavailability of the full text or because in vivo experiments were conducted on non-wild-type mice (with the exception of AG129, for reasons explained previously in the article). Finally, 185 studies were included as shown in the following flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the analysis of articles; a final number of 185 articles were included though preliminary and full text analysis.

The 185 included studies were analysed, and the experiments reported in each study were grouped by the arbovirus investigated in the experiment. A number of 60 articles included experiments about more than one arbovirosis. We decided to present the results by aggregating the data for each individual arbovirosis to provide a coherent overview aligned with each pathology. By structuring the analysis in this way, we aim to offer a more focused and systematic perspective on how each arbovirosis responds to different treatments. None of the included articles addressed experiments on USUV.

Finally, it was assessed whether the experiments included a cytokine profile study before and after the administration of the molecules. A cytokine profile analysis was conducted in 31 experiments, most of which focused on DENV (20 experiments).

3.2. DENV experimental and repurposed therapies

We included 99 articles about molecules with hypothetical effects against DENV, primarily in vitro (67/99, 67.6 %) or a combination of in vitro and in vivo (15/99, 15.1 %). In vitro experiments were predominantly conducted in Vero cells (21/94, 22.3 %) and Huh7 cells (20/94, 21.2 %) or multiple cell lines (34/94, 36.1 %). In vivo studies used mouse models, particularly AG129 mice (12/16, 75 %), with blood samples considered in most cases (10/16, 62.5 %). Most tested drugs were experimental (93/121, 76.8 %) or repurposed (5/27, 18.5 %) antivirals, antibiotics, or chemotherapies. Molecules tested were primarily viral replication inhibitors (50/121, 41.3 %) or viral entry inhibitors (25/121, 20.6 %) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and typology of articles about dengue virus (DENV), with cell culture or animal models utilized. Molecules tested were collected by typology, repurposed or experimental.

| Articles, n (%)a | 99 (100) |

| In vitro, n (%) | 68 (68.6) |

| In vivo, n (%) | 1 (1) |

| In vitro and in silico, n (%) | 11 (11.1) |

| In silico, n (%) | 4 (4) |

| In vitro and in vivo, n (%) | 15 (15.1) |

| Cell cultures, n (%) | 95 (100) |

| Vero cells, n (%) | 21 (22.1) |

| Huh7, n (%) | 21 (22.1) |

| BHK-21, n (%) | 10 (10.5) |

| Combination of more than 1 cell culture, n (%) | 34 (35.7) |

| Others, n (%) | 9 (9.4) |

| Animal models, n (%) | 16 (100) |

| Mice | 14 (100) |

| AG129, n (%) | 12 (75) |

| C57BL/6J, n (%) | 1 (6.3) |

| BALB, n (%) | 1 (6.3) |

| ICR, n (%) | 2 (12.5) |

| Tissue, n (%) | 16 (100) |

| Blood, n (%) | 5 (31.3) |

| Blood and other tissues, n (%) | 5 (31.3) |

| Brain, n (%) | 2 (12.5) |

| Spleen, n (%) | 1 (6.3) |

| Others, n (%) | 3 (18.8) |

| Molecules tested, n (%) | 120 (100) |

| Viral replication inhibitors, n (%) | 50 (41.6) |

| Viral entry inhibitors, n (%) | 25 (20.8) |

| Viral protease inhibitors, n (%) | 14 (11.6) |

| Viral capside inhibitors, n (%) | 6 (4.9) |

| Immunomodulant, n (%) | 15 (12.5) |

| Others, n (%) | 7 (5.8) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 3 (2.5) |

| Repurposed, n (%) Experimental, n (%) |

27 (22.4) 93 (77.6) |

| Known antivirals, n (%) | 5 (18.5) |

| Known antibiotics, n (%) | 4 (14.8) |

| Known agents used in tropical medicine, n (%) | 1 (3.7) |

| Chemotherapy or antitumoral, n (%) | 4 (14.8) |

| Others, n (%) | 13 (48.1) |

| Serotype, n (%) | |

| DENV2, n (%) | 62 (62.6) |

| Combination of DENV2 AND another serotype, n (%) | 22 (22.2) |

| Others, n (%) | 15 (15.2) |

a single study can test more than one model.

Among in vitro studies ribavirin significantly reduced DENV-infected cell viral titters in 5 experiments [22,23], often in combination with other compounds [24]. Other molecules that significantly reduced in vitro viral titer were mycophenolic acid [25,26] bortezomib [27] micafungin [28], montelukast [29], atorvastatin and ezetimibe [30] and doxorubicin derivatives [31,32]. Interestingly, macrolide antibiotics produced by certain bacteria of the Streptomyces genus, such as ascomycin [33] and anisomycin [34] have resulted in a significant reduction of viral titer in in vitro experiments. We must note that most of the experiments conducted in vitro involve experimental molecules not previously known in the scientific literature and specifically designed for the study in question. Among these, the largest class comprises nucleic acid analogs, which have shown efficacy in reducing viral titer in several studies. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vitro experiments about dengue virus (DENV).

| Class of molecules tested in vitro | Number of experiments: 115 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 21 (24,1) [22] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [24] [46] [47] [48] [49] |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 22 (25,3) [50] [51] [52] [53] [35] [54] [33] [30] [55] [56] [22] [57] [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] [27] |

| Immune system modulators, n (%) | 8 (9,2) [66] [67] [68] [69] [70] [71] [72] [73] |

| Peptides and derivatives (inhibition or interaction with viral proteins), n (%) | 15 (17,2) [74] [75] [76] [77] [78] [79] [80] [81] [82] [83] [84] [85] [86] [87] [88] |

| Inhibitors/activators of cellular signalling pathway, n (%) | 6 (6,9) [89] [31] [90] [91] [92] [26] |

| Metabolism modulators (metabolic antagonists and inhibitors), n (%) | 6 (6,9) [31] [29] [93] [26] [25] |

| Antimicrobial, antifungal agents and antiparasitic agents, n (%) | 4 (4,6) [28] [81] [94] [95] |

| Modulators of cellular function and microenvironment, n (%) | 8 (9,2) [31] [96] [97] [98] [34] [81] |

| Antitumor and chemotherapeutic agents, n (%) | 7 (8) [99] [100] [101] [31] [102] [32] |

| Hormonal and receptor modulators, n (%) | 2 (2,3) [77] [103] |

| Inhibitors of structural and lipid protein, n (%) | 5 (5,7) [24] [104] [105] |

| Inhibitors of bacterial or viral replications, n (%) | 2 (2,3) [106] [107] |

| Miscellaneous or combined substance, n (%) | 9 (10,3) [108] [109] [110] [111] [96] [112] [113] [114] [115] |

In vivo studies confirmed the viremia-reducing effect of ezetimibe and atorvastatin [30] and the efficacy of CM10-18 and ribavirin combinations [24]. Similarly, the antiviral effect of montelukast [29] bortezomib [27] and micafungin [28] was confirmed in in vivo experiments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vivo experiments about dengue virus (DENV).

| Class of molecules tested in vivo | Number of experiments: 19 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 6 (31,5) [24] [45] [61] [37] [46] |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 2 (10,5) [114] [61] |

| Immune system modulators, n (%) | 1 (5,3) [116] |

| Peptides and derivatives (inhibition or interaction with viral proteins), n (%) | 2 (10,5) [74] [92] |

| Inhibitors/activators of cellular signalling pathway, n (%) | 2 (10,5) [29] [43] |

| Antimicrobial, antifungal agents and antiparasitic agents, n (%) | 1 (5,3) [28] |

| Inhibitors of structural and lipid proteins, n (%) | 1 (5,3) [30] |

| Inhibitors of bacterial or viral replications, n (%) | 2 (10,5) [106] [107] |

| Miscellaneous or combined substance, n (%) | 2 (10,5) [109] [108] |

Molecules targeting DENV were among the most studied in all articles (99/185), with experiments frequently conducted in vitro, often involving combinations of multiple cell cultures. All animal experiments were conducted on mice (predominantly the AG129 strain) and all molecules tested apart three (PI-88 [108]; Compound 3 and 4 [114]; Ezetemibe and atorvastatin [30]) showed a positive effect on viral decrease. Among the most studied drugs that showed positive results in reducing viral replication both in vitro and in vivo were cholesterol-lowering agents [30] and ribavirin [24]. Only 8 studies in vivo investigated the effects of the molecule tested on the inflammatory profile, all of them described a decrease in inflammatory cytokines tested.

3.3. CHIKV experimental and repurposed therapies

We included 36 articles about molecules with hypothetical effects against on CHIKV, primarily in vitro (25/36, 69.4 %) or a combination of in vitro and in silico (6/36, 16.7 %). No study was conducted on a human population. In vitro experiments were predominantly conducted in Vero cells (13/35, 37.1 %) or multiple cell lines (10/35, 28.6 %). In vivo studies used mouse models, particularly C57BL/6J mice (2/5, 40 %), with blood samples considered in most cases (3/5, 60 %). Most tested drugs were experimental (29/49, 59.2 %) or repurposed (9/20, 45 %) antivirals or antibiotics. Molecules tested were primarily viral replication inhibitors (21/49, 42.9 %) or viral entry inhibitors (12/49, 24.5 %) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number and typology of articles about chikungunya virus (CHIKV), with cell culture or animal models utilized. Molecules tested were collected by typology, repurposed or experimental.

| Articles, n (%) a | 36 (100) |

| In vitro, n (%) | 25 (69.4) |

| In vivo, n (%) | 1 (2.8) |

| In vitro and in silico, n (%) | 6 (16.7) |

| In vitro and in vivo, n (%) | 3 (8.3) |

| In vitro, in silico and in vivo, n (%) | 1 (2.8) |

| Cell cultures, n (%) | 29 (100) |

| Vero cells, n (%) | 13 (37.1) |

| Huh7, n (%) | 2 (5.7) |

| BHK-21, n (%) | 4 (11.4) |

| Combination of more than 1 cell culture, n (%) | 10 (28.6) |

| Mice models, n (%) | 16 (100) |

| Mice, n (%) | 5 (100) |

| AG129, n (%) | 1 (20) |

| C57BL/6J, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Tissue, n (%) | 5 (100) |

| Blood, n (%) | 3 (60) |

| Blood and other tissues, n (%) | 2 (40) |

| Molecules tested, n (%) | 49 (100) |

| Viral replication inhibitors, n (%) | 21 (42.9) |

| Viral entry inhibitors, n (%) | 12 (24.5) |

| Viral protease inhibitors, n (%) | 7 (14.3) |

| Immunomodulant, n (%) | 2 (4.1) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 5 (10.2) |

| Repurposed, n (%) | 20 (40.8) |

| Experimental, n (%) | 29 (59.2) |

| Known antivirals, n (%) | 9 (45) |

| Known antibiotics, n (%) | 3 (15) |

| Known agents used in tropical medicine, n (%) | 2 (10) |

| Others, n (%) | 6 (30) |

a single study can test more than one model.

In vitro studies showed favipiravir significantly reduced CHIKV-infected cell viral titres and affected cytokine regulation (e.g., IL-6, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and RANTES) [117,118]. Ribavirin and hydroxychloroquine showed dose-dependent effects on viral titres. 119 120 117 (Table 5) In vivo studies confirmed the viremia-reducing effect of favipiravir and doxycycline's anti-inflammatory effects [119]. (Table 6)

Table 5.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vitro experiments about chikungunya virus (CHIKV).

| Class of molecules tested in vitro | Number of experiments: 38 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 7 (18,4) [121] [122] [123] [124] [125] |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 10 (26,3) [126] [118] [117] [119] [120] [127] [128] [129] |

| Immune system modulators, n (%) | 4 (10,5) [130] [67] [131] [132] |

| Peptides and derivatives (inhibition or interaction with viral proteins), n (%) | 5 (13,1) [133] [134] [135] [107] [46] |

| Inhibitors/activators of cellular signalling pathway, n (%) | 4 (10,5) [136] [120] [137] [138] |

| Metabolism modulators (metabolic antagonists and inhibitors), n (%) | 2 (5,3) [139] [130] |

| Antimicrobial, antifungal agents and antiparasitic agents, n (%) | 3 (7,9) [119] [137] |

| Modulators of cellular function and microenvironment, n (%) | 2 (5,3) [140] [141] |

| Antitumor and chemotherapeutic agents, n (%) | 1 (2,6) [142] |

Table 6.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vivo experiments about chikungunya virus (CHIKV).

| Class of molecules tested in vivo | Number of experiments: 5 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 1 (20) 67 |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 4 (80) 119,118,143,118 |

| Inhibitors/activators of cellular signalling pathway, n (%) | 1 (20) 136 |

Molecules targeting CHIKV were studied in 36 articles (36/185), with experiments frequently conducted in vitro, often involving Vero cell cultures. All animal experiments were conducted on mice. All studied molecules showed positive results in reducing viral replication both in vitro and in vivo, the most frequently studied were favipiravir, doxycycline and ribavirin. 2/6 studies investigated the effects on inflammatory profile with promising results (Derivatives of geldanamycin [136]; doxycycline and ribavirin) [119].

3.4. WNV experimental and repurposed therapies

We included 30 articles about molecules with hypothetical effects against WNV, primarily in vitro (27/30, 90 %). No study was conducted on a human population. In vitro experiments used multiple cell lines (15/29, 51.7 %) or Vero cells (10/29, 34.4 %). Most tested drugs were experimental (29/35, 82.8 %). Among the repurposed drugs, known antivirals (3/6, 50 %) were the most tested. Molecules tested were primarily viral replication inhibitors (25/35, 71.4 %) or viral protease inhibitors (5/35, 14.3 %) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Number and typology of articles about west nile virus (WNV), with cell culture or animal models utilized. Molecules tested were collected by typology, repurposed or experimental.

| Articles, n (%) a | 36 (100) |

| In vitro, n (%) | 27 (90) |

| In silico, n (%) | 1 (3.3) |

| In vitro and in silico, n (%) | 1(3.3) |

| In vitro and in vivo, n (%) | 1 (3.3) |

| Cell cultures, n (%) | 29 (100) |

| Vero cells, n (%) | 10 (34.4) |

| Huh7, n (%) | 1 (3.4) |

| BHK-21, n (%) | 3 (11.1) |

| Combination of more than 1 cell culture, n (%) | 15 (51.7 |

| Mice models, n (%) | 1 (100) |

| Mice, n (%) | 1 (100) |

| BALB, n (%) | 1 (100) |

| Tissue, n (%) | 1 (100) |

| Blood, n (%) | 1 (100) |

| Molecules tested, n (%) | 35 (100) |

| Viral replication inhibitors, n (%) | 25 (71.4) |

| Viral entry inhibitors, n (%) | 3 (8.6) |

| Viral protease inhibitors, n (%) | 5 (14.3) |

| Immunomodulant, n (%) | 2 (5.7) |

| Repurposed, n (%) | 6 (17,1) |

| Experimental, n (%) | 29 (82.8) |

| Known antivirals, n (%) | 3 (50) |

| Others, n (%) | 3 (50) |

a single study can test more than one model.

In vitro studies showed favipiravir reduced WNV viral titters [144], as did ribavirin and umifenovir. 145 146 Repurposed drugs like heparin [108] mycophenolic acid [25], raloxifene hydrochloride and quinestrol also reduced viral titters [103] (Table 8). Only one in vivo study explored C2′-methylated nucleosides, showing reduced viremia and symptoms at 50 mg/kg/day [147]. (Table 9)

Table 8.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vitro experiments about west nile virus (WNV).

| Class of molecules tested in vitro | Number of experiments: 32 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 9 (28,1) [145] [45] [148] [147] [149] [51] [42] |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 10 (31,3) [150] [151] [146] [25] [59] [111] [144] [90] [53] [86] |

| Peptides and derivatives (inhibition or interaction with viral proteins), n (%) | 13 (40,6) [108] [111] [152] [153] [73] [154] [155] [103] [62] [115] [54] [92] |

Table 9.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vivo experiments about west nile virus (WNV).

| Class of molecules tested in vivo | Number of experiments: 1 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 1 (100) 147 |

Molecules targeting WNV were studied in 30 articles (30/185), with experiments frequently conducted in vitro, often involving Vero cell cultures and most of them were experimental molecules. All animal experiments were conducted on mice and all molecules tested showed a positive effect on viral decrease. Among the most studied drugs that showed positive results in reducing viral replication were ribavirin conducted in vitro and only a study was conducted in vivo [147] with positive results, both reducing viremia and symptoms.

3.5. ZIKV experimental and repurposed therapies

We included 69 articles about molecules with hypothetical effects against ZIKV, primarily in vitro (50/69, 72.5 %) or a combination of in vitro and in vivo (8/69, 11.6 %). In vitro experiments used multiple cell lines (27/65, 41.5 %) or Vero cells (18/65, 27.7 %). In vivo studies used mouse models, particularly AG129 mice (6/9, 66.7 %), with blood samples considered in most cases (8/11, 72.7 %). Most tested drugs were experimental (52/77, 67.5 %) or repurposed (9/25, 36 %) antivirals. Molecules tested were primarily viral replication inhibitors (42/77, 54.5 %) or viral entry inhibitors (10/77, 13 %) (Table 10).

Table 10.

Number and typology of articles about zika virus (ZIKV), with cell culture or animal models utilized. Molecules tested were collected by typology, repurposed or experimental.

| Articles, n (%) a | 69 (100) |

| In vitro, n (%) | 50 (72.5) |

| In vivo, n (%) | 3 (4.3) |

| In vitro and in silico, n (%) | 7 (10.1) |

| In silico, n (%) | 1 (1.4) |

| In vitro and in vivo, n (%) | 8 (11.6) |

| Cell cultures, n (%) | 65 (100) |

| Vero cells, n (%) | 18 (27.7) |

| Huh7, n (%) | 9 (13.8) |

| BHK-21, n (%) | 3 (4.6) |

| Combination of more than 1 cell culture, n (%) | 27 (41.5) |

| Others, n (%) | 8 (12.3) |

| Animal models, n (%) | 11 (100) |

| Rhesus macaco, n (%) | 2 (18.2) |

| Mice, n (%) | 9 (81.8) |

| AG129, n (%) | 6 (66.7) |

| C57BL/6J, n (%) | 2 (22.2) |

| Others, n (%) | 1 (11.1) |

| Tissue, n (%) | 11 (100) |

| Blood, n (%) | 2 (18.2) |

| Blood and other tissues, n (%) | 6 (54.4) |

| Brain, n (%) | 2 (18.2) |

| Others, n (%) | 1 (9.1) |

| Molecules tested, n (%) | 77 (100) |

| Viral replication inhibitors, n (%) | 42 (54.5) |

| Viral entry inhibitors, n (%) | 10 (13.0) |

| Viral protease inhibitors, n (%) | 5 (6.5) |

| Immunomodulant, n (%) | 3 (3.9) |

| Others, n (%) | 10 (12.9) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 7 (9) |

| Repurposed, n (%) | 25 (32.5) |

| Experimental, n (%) | 52 (67.5) |

| Known antivirals, n (%) | 9 (36) |

| Known antibiotics, n (%) | 1 (4) |

| Known agents used in tropical medicine, n (%) | 2 (8) |

| Others, n (%) | 13 (52) |

a single study can test more than one model.

In vitro studies showed favipiravir reduced ZIKV viral titters with dose-dependent effects 156 157 even in association with IFN [23]. Ribavirin also reduced viral titters. 156 23.Some drugs affected cytokine expression, including YM201636 158, chromeno derivatives 67 109, and defective interfering particles of influenza A virus [159]. (Table 11) In vivo studies confirmed favipiravir's viremia-reducing effect [160] and sofosbuvir's ability to reduce ZIKV neuroinvasion in rhesus macaques [161]. Other drugs showed efficacy in preventing congenital Zika syndrome (AH-D162), reducing viral replication in foetal tissues (CH223191 [163]; sEVSRVG [164]), or blocking vertical transmission (Z2 Compound [165]). (Table 12)

Table 11.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vitro experiments about zika virus (ZIKV.

| Class of molecules tested in vitro | Number of experiments: 72 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 14 (19,4) [156] [157] [166] [167] [168] [169] [170] [171] [172] [39] [173] [38] |

| Enzyme inhibitors (proteasome, polymerase, other viral proteins), n (%) | 12 (16,7) [63] [174] [101] [86], [175] [100] [53] [42] [51] [176] [177] |

| Immune system modulators, n (%) | 4 (5,5) [178] [16867,109] |

| Peptides and derivatives (inhibition or interaction with viral proteins), n (%) | 3 (4,2) [92], [179] [139] |

| Inhibitors/activators of cellular signalling pathway, n (%) | 4 (5,5) [90] [180] [158] [34] |

| Antimicrobial, antifungal agents and antiparasitic agents, n (%) | 3 (4,2) [34] [181] [182] |

| Antitumor and chemotherapeutic agents, n (%) | 4 (5,5) [55] [178] [183] [184] |

| Hormonal and receptor modulators, n (%) | 2 (2,8) [163] [103] |

| Inhibitors of structural and lipid protein, n (%) | 6 (8,3) [185] [186] [187] [165] [188] |

| Inhibitors of bacterial or viral replications, n (%) | 8 (11,1) [70] [84] [33] [159], [189] [146] [107] [190] |

| Miscellaneous or combined substance, n (%) | 12 (16,7) [154], [168], [191] [178] [97], [192] [50] [164] [52] [193] [30] |

Table 12.

Class of molecules used in experiments used in in vivo experiments about zika virus (ZIKV.

| Class of molecules tested in vivo | Number of experiments: 11 |

|---|---|

| Nucleosides or nucleotide analogs (viral replication inhibitors), n (%) | 4 (36,4) [160], [161], [173] [171] |

| Immune system modulators, n (%) | 1 (9,1) [109] |

| Hormonal and receptor modulators, n (%) | 1 (9,1) [163] |

| Antimicrobial, antifungal agents and antiparasitic agents, n (%) | 1 (5,3) [28] |

| Inhibitors of structural and lipid proteins, n (%) | 1 (9,1) [33,165] |

| Inhibitors of bacterial or viral replications, n (%) | 1 (9,1) [33] |

| Miscellaneous or combined substance, n (%) | 2 (18,2) [164] [162] |

Molecules targeting ZIKV were studied in 69 articles (69/185), with experiments mostly conducted in vitro, often involving Vero cell cultures and most of them were experimental molecules. Among animal models for in vivo experiments, in two of them rhesus macaco was used (favipiravir [160]; sofosbuvir [161],). Among the most studied drugs that showed positive results in reducing viral replication were ribavirin [156] conducted in vitro and favipiravir [156] and anisomycin [34](both in vivo and in vitro). Very few data are available regarding effects on the inflammatory profile of repurposing or novel molecules used for ZIKV in vitro or in vivo.

4. Discussion

This review identified articles in the literature that dealt with innovative and repurposed approaches for the antiviral treatment of viruses such as DENV, WNV, CHIKV and ZIKV, exploiting preclinical in vitro and in vivo studies. Most of the available literature is focused on experimental molecules investigated through in vitro studies. Among the experiments conducted in vivo, the most frequently used animal models have been mice. Repurposed drugs were used the most, probably due to the already known generic antiviral effect. In the preliminary research, in human studies were also included of which the only one concerning balapiravir in a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial proved to be ineffective in the treatment of dengue fever [49].

4.1. Molecules with relevant antiviral effect on several arboviruses

Several drugs have shown efficacy in the treatment of multiple arboviruses, suggesting potential use as broad-spectrum antivirals. Among the most investigated classes of drugs that have obtained interesting results in more than one virus are nucleoside analogs that act as inhibitors of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), the most highly conserved protein in all known RNA viruses, by inducing viral replication errors.

Favipiravir, a novel broad-spectrum antiviral drug against RNA viruses, showed a significant reduction in viremia in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies for WNV, ZIKV and CHIKV. Favipiravir inhibits the RdRp and is approved for the treatment of seasonal and pandemic influenza. The action of favipiravir as antiviral is induction of genomic mutations and termination of viral RNA synthesis by acting as a nucleoside analogue. This process leads to a loss of infectivity or the production of nonviable virions, thereby further inhibiting viral replication and propagation [194]. Toxicity studies indicate that favipiravir has a relatively high safety margin, except for a teratogenic risk in pregnant rats [195]. Adverse effects are moderate diarrhoea, asymptomatic increase of transaminases, and uncommonly decreased neutrophil counts [196]. In six studies, favipiravir was effective in reducing viral titre in in vitro experiments and in three studies it was effective in reducing viral titre in vivo models and in attenuating clinical symptoms of infection. In the study conducted by Best K et al., for instance, favipiravir decreased the peak viremia of ZIKV and shortened the time to negativity in a macaque population [160]. A limitation of the study was that the drug had no effect when administered two days after infection, highlighting how difficult it is in clinical practice to treat an infection as it develops in the human body. Another study by Julander et al., demonstrated the efficacy of favipiravir against CHIKV. However, this effectiveness depends on the viral clade under study and the timing of drug administration [118]. The timing of administration was also confirmed as important in the study by Abdelnabi R et al., in which if administered within 3 days of infection, favipiravir reduced the clinical signs of arthropathy in a population of mice [143]. On the contrary, it had no effect on chronic CHIKV arthritis. Although it has some limitations due to the nature of the drug, favipiravir proves to be the most interesting drug in the experimental treatment of arboviruses.

Ribavirin (RBV), another nucleoside analogue, displays broad antiviral activity against several RNA and DNA viruses through several mechanisms. RBV, in combination with pegylated interferon, has been one of the therapeutic options for the treatment of HCV infection until the advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) [197]. The exact mechanism of RBV against hepatitis C virus (HCV) remains unclear. The most straightforward possible mechanism of action would be that RBV acts as an inhibitor of the viral polymerase [198] but a mechanism of induced mutagenesis in the virion genome cannot be excluded [199]. Since HCV belongs to the Flaviviridae family, it is plausible that this mechanism also plays a role in viruses such as DENV. Another mechanism observed in HCV is the inhibition of the host enzyme inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), resulting in GTP depletion and the direct inhibition of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [200]. IMPDH enzyme is also crucial in DENV replication [201]. The final proposed mechanism of action is its immunomodulatory effect, the induction of interferon-stimulated genes and the strengthening of the adaptive antiviral immune response [197]. RBV has a remarkable toxicity profile and significant adverse effects, particularly haemolytic anaemia, which complicates its clinical use [202]. RBV was tested in 12 in vitro experiments and in 3 in vivo experiments, frequently in combination with other molecules. According to Yeo KL et al. RBV, as well as brequinar, decreases the viral load of DENV in vitro and causes ISRE activation (interferon-stimulated response element, i.e. the expression of interferon with antiviral activity). This antiviral activity is independent of the possible combination of RBV with the administration of IFNb itself [22]. The study conducted by Rothan HA et al., the combination doxycycline + RBV significantly reduced the viral titre of CHIKV in the blood of infected mice, showing greater efficacy than single treatment with doxycycline or RBV. The combination demonstrated a synergistic action, acting on both viral replication (primary effect of RBV) and virus entry into cells (primary effect of doxycycline) [119]. In addition, toxicity tests showed no significant toxicity data for RBV even at high doses (50 mg/kg) and it is likely that combining RBV with other substances is the key to increasing efficacy even while decreasing the adverse effects that are dose-dependent [203].

Doxycycline, a well-known antibiotic widely used in clinical practice, has also proven to have antiviral effects based on his anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties mitigating symptoms associated with viral infections and on direct effect on viral biology, leading to the inhibition of viral entry and viral replication suggesting a multifaceted therapeutic approach against viruses [204], [205]. Doxycycline showed immunomodulatory activity by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mouse models, improving clinical outcomes in acute CHIKV infections [119]. The antiviral properties of doxycycline were also confirmed in some other in vitro studies such reported by Chong Teoh T et al. in which doxycycline effectively binds to the active site of Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease, inhibiting its catalytic activity, which is crucial for viral replication [206]. Furthermore, in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Fredeking T.M. et al., it was observed that the doxycycline-treated group exhibited a 46 % lower mortality rate compared to the untreated group. This demonstrated that doxycycline may provide clinical benefits to dengue patients at high risk of complications, potentially mediated through its effect on reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine levels [207].

Cholesterol-lowering drugs such as atorvastatin and ezetimibe, in monotherapy or in combination showed an indirect antiviral effect by reducing plasma lipids, which represent an essential structural component of lipid rafts and host cell membranes and necessary for the assembly of viral particles. In vitro results show that both drugs significantly reduce cellular infection in a dose-dependent manner, with synergistic effects against DENV 2 and additive effects against DENV4 and ZIKV [30]. In AG129 mouse models infected with DENV 2, both drugs in monotherapy improved survival and reduced clinical signs, whereas the combination of the two showed no additional benefit on mortality rate [30]. The combination of atorvastatin and ezetimibe exploits complementary mechanisms: the former inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis, while the latter blocks its absorption. The lack of a synergistic effect on mortality rate in vivo is probably due to the complex mechanisms of intracellular cholesterol synthesis that compensate for the activity of the drugs. However, the hypothesis that cholesterol-lowering drugs such as lovastatin, may interfere with the virion assembly phases rather than the replication phase, has already been put forward in the literature in the past by in vitro studies [208]. In contrast to other antiviral drugs, cholesterol-lowering drugs have the advantage of having a broad safety profile, although generally well-tolerated, they can present various safety concerns, particularly related to liver and muscle health [209]. However, these drugs are widely used in clinical practice so a possible experimental use in arboviruses seems reasonable.

Sofosbuvir is another nucleoside analogue (uridine nucleotide) that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of ZIKV, DENV and HCV. Sofosbuvir is particularly relevant for ZIKV due to its efficacy in preventing neuroinvasion in non-human primate models (macaques) as found in the study by Medina et al., Although the decrease in ZIKV viral load after administration of the drug was not relevant, it showed significant neuroprotective effects, improving brain development and attenuating behavioural and cognitive deficits [161]. Specifically, it was found that ventricular volumes were normalised, when we know that the typical structural alteration in ZIKV microcephaly is ventriculomegaly [210]. However, the small sample size of this study limits the generalisability of the results and underlines the need for further studies with larger samples and different viral strains.

Finally, antiviral activity of 2′-C-methylated nucleosides as competitive inhibitors of RdRp has been broadly studied in arbovirus. Acting as a competitive inhibitor of NS5 polymerase of DENV, 2′-C-methylcytidine also proved to be a good drug against DENV in mouse models, reducing viral load and increasing survival. Compared to other nucleoside analogs, 2′-C-methylcytidine shows potent inhibition of NS5 RNA polymerase and remarkable cross-serotype antiviral activity on the four serotypes of DENV. In addition, the toxicity studies conducted showed a good safety profile [43].

4.2. Repurposed molecules with a specific antiviral effect on a single arboviruses

Montelukast is a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTD4) primarily used in the management of asthma and allergic rhinitis. The action of montelukast as an antiviral has recently been under study. In in vitro and in vivo studies, Montelukast has been shown to disrupt viral infectivity, prevent adhesion and internalisation of the ZIKV virion into the host cell. In addiction it irreversibly compromises virion integrity [211]. Furthermore, it has been hypothesised that montelukast interferes with viral replicon formation and blocks the NS2B-NS3 protease of DENV and ZIKV [212]. It appears that the antiviral action of montelukast also includes an anti-inflammatory action. According to studies conducted against Sars-CoV-2, because of LTD4 blockage, montelukast decrease nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) pathway activation and release of the proinflammatory mediators (i.e., IL-6, -8, and -10; TNF-a; and MCP-1). It is a widely well-tolerated drug in clinical practice. Rare adverse effects are headache, asthma and upper respiratory tract infection [213]. Montelukast proved effective in improving survival, reducing viremia and alleviating systemic symptoms of DENV in mouse models. In addition, it resulted in reduced levels of TNF, IL-6 and IFN-γ, which correlated with inhibition of viral replication and reduction of ‘cytokine storm’, a key component in the pathophysiology of DENV viral infection [29]. The same drug has been used in ZIKV infections as in the in vitro and in vivo study by Chen Y et al. [211] In addition, montelukast blocks vertical transmission in ZIKV infection leading to a neuroprotective effect and decreasing mortality. 211 214 An open-label, parallel, randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Ahmad A et al., analysed the effect of montelukast administration on 200 patients. This study is not included in the systematic reviewbecause it did not fit in the search terms but it is interesting because it demonstrated that montelukast per os reduced the absolute risk and relative risk of Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS) in DENV infection [[214], [215]].

Micafungin is an echinocandin antifungal agent primarily used for the treatment and prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections, particularly those caused by Candida and Aspergillus spp. It has a fair toxicity profile, especially in critically ill patients, leading to liver damage [216]. In the study by Kim et al., micafungin treatment reduced DENV viremia, inflammatory cytokine levels, and viral loads in several tissues and improved survival rates by up to 40 % in a lethal mouse model [28]. These results also seem to be confirmed by Chen YC et al. which emphasises the antiviral action of micafungin in the early stages of viral infection, in binding and entry of the virus into cells [217].The studies on montelukast and micafungin are interesting because they offer a different perspective on antiviral treatment, acting on the structural assembly of the virion and its entry into the cell, rather than on the replication stages. The study and testing of drugs that act at multiple levels on the infection is crucial in the field of virology. Combination therapy is a cornerstone of personalised treatment of viral infections as it makes it possible to reduce the adverse effects of individual drugs by lowering doses and acting on different drug targets [218].

HSP-90 (Heat Shock Protein 90) is an essential chaperone protein involved in regulating the folding, stability, and activity of numerous proteins, many of which play critical roles in cell signalling, stress response, and viral replication. HSP90 facilitates the interaction between viral proteins and cell replication complexes and may modulate innate immunity by suppressing the antiviral response [219]. A study by Rathore et al., evaluating the use of some HSP-90 inhibitors called geldanamycin analogs (HS-10 and SNX-2112), showed dramatic reductions in CHIKV viral titters and reduced inflammation in a mouse model of severe infection and myopathy [136]. This study demonstrates the importance of studying the mechanisms of interaction between virus and host and how the identification of new targets is crucial for the development of new therapeutic approaches.

4.3. Effects on cytokines and the inflammatory profile

Modulation of the inflammatory response is a key point in the treatment of arbovirus infections. One of the key mechanisms is the stimulation of the innate immune response mediated by IFN types I and III. For example, the increase in Interferon-Stimulated Response Element (ISRE) determined by ribavirin and brequinar reported in the study by Yeo KL et al. increases Type I and Type III interferons (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-λ) resulting in inhibition of viral replication [22]. The cytokine profile was evaluated by a few experiments. In most of them the drugs resulted in an up-regulation of IFN-α and IFN-β (type 1 interferons), key elements in the innate response [220]. Furthermore, some evidence points to IFN-α playing a protective role against the chronic post-CHIKV infections [221]. Among the other cytokines that have been analysed the most, we find IL6 and TNFa, proinflammatory cytokines. Both cytokines were analysed with ambiguous results. In half of the experiments, there was downregulation of cytokine expression. These apparently contradictory results probably reflect the complex role of these two cytokines in mounting an efficient immune response and, at the same time, being markers of infection severity [222]. Probably, the reduction of these cytokines, has a greater effect on the risk of chronicity of arbovirus disease, as illustrated by Hoarau JJ et al. who showed that these two cytokines have a direct effect on the chronicity of CHIKV disease [223]. For this reason, the contradictory effect of some drugs, which are effective in reducing the viral titre or in symptomatic resolution but upregulate these cytokines, is probably to be considered insignificant in the acute phases of the disease.

5. Conclusions

This review has highlighted the multitude of information regarding antiviral treatments for arboviruses with epidemic potential. Several experimental compounds or molecules already in use, in particular nucleoside analogs and immune modulators, have demonstrated efficacy in vitro and in vivo, but there is only one clinical phase study in human.

The absence of approved therapies for arboviruses such as ZIKV, DENV, CHIKV and WNV poses a significant challenge, especially in regions of high vulnerability. Many compounds studied, such as favipiravir and ribavirin, have shown promising antiviral activity, but suffer from limitations related to toxicity or efficacy in advanced stages of infection. Some drugs widely used in clinical practice, such as doxycycline, montelukast and cholesterol-lowering drugs have proved effective in reducing viremia and clinical signs of infection. It would be plausible to further study their antiviral effect.

As global temperatures continue to rise and vectors expand geographically, the incidence of arbovirus infections is set to increase. It is therefore crucial to adopt an integrated multidisciplinary approach to improve clinical management, involving virologists, immunologists and infectious disease specialists. Furthermore, efforts must be intensified to develop effective therapies that can prevent progression to severe forms and treatments aimed at modulating the immune response. This work helps outline future opportunities for the development of safer and more effective antiviral therapies that can address not only viral replication, but also the deleterious immunological effects associated with these infections.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jacopo Logiudice: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Giorgio Tiecco: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alessandro Pavesi: Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Francesca Bertoni: Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Roberta Gerami: Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Isabella Zanella: Visualization, Validation. Anna Artese: Visualization, Validation. Francesco Castelli: Visualization, Validation. L.R. Tomasoni: Visualization, Validation. B. Rossi: Visualization, Validation. D. Lelli: Visualization, Validation. S. Canziani: Visualization, Validation. A. Russo: Visualization, Validation. G. Di Donato: Visualization, Validation. Eugenia Quiros-Roldan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is funded by the Next Generation EU Program under PNRR (M6/C2 Call 2023). Project Code: PNRR-POC-2023-12377826.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Handling editor:Patricia Schlagenhauf

Contributor Information

SPARROW group:

Francesco Castelli, Lina Rachele Tomasoni, Benedetta Rossi, Davide Lelli, Sabrina Canziani, Alessandro Russo, and Guido Di Donato

References

- 1.Kraemer M.U.G., Reiner R.C.J., Brady O.J., et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat Microbiol. 2019 May;4(5):854–863. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wimalasiri-Yapa B.M.C.R., Yapa H.E., Huang X., et al. Zika virus and arthritis/arthralgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Viruses. 2020 Oct;12(10) doi: 10.3390/v12101137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . new edition. World Health Organization; 2009. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44188 [Internet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu-Helmersson J., Quam M., Wilder-Smith A., et al. Climate change and aedes vectors: 21St century projections for dengue transmission in Europe. EBioMedicine. 2016 May;7:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan S.J., Carlson C.J., Mordecai E.A., et al. Global expansion and redistribution of Aedes-borne virus transmission risk with climate change. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019 Mar;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laing G., Vigilato M.A.N., Cleaveland S., et al. One health for neglected tropical diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2021 Jan;115(2):182–184. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bampali M., Konstantinidis K., Kellis E.E., et al. West nile disease symptoms and comorbidities: a systematic review and analysis of cases. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022 Sep;7(9) doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7090236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salimi H., Cain M.D., Klein R.S. vol. 13. Springer New York LLC; 2016. Encephalitic arboviruses: emergence, clinical presentation, and neuropathogenesis; pp. 514–534. (Neurotherapeutics). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaldo N., Graziano E., Peghin M., et al. Neuroinvasive west nile infection with an unusual clinical presentation: a single-center case series. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2020;5 doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5030138. Switzerland. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.N Sirisena P.D.N., Mahilkar S., Sharma C., et al. Concurrent dengue infections: Epidemiology & clinical implications. Indian J Med Res. 2021 May;154(5):669–679. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1219_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srichaikul T., Nimmannitya S. Haematology in dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000 Jun;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dengue and severe dengue. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from:

- 13.Bavarian Nordic Receives U.S FDA approval of chikungunya. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/02/14/3026914/0/en/Bavarian-Nordic-Receives-U-S-FDA-Approval-of-Chikungunya-Vaccine-for-Persons-Aged-12-and-Older.html [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from:

- 14.Thomas S.J., Yoon I.K. A review of dengvaxia®: development to deployment. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(10):2295–2314. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1658503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman D.O. A new dengue vaccine (TAK-003) now WHO recommended in endemic areas; what about travellers? J Travel Med. 2023 Nov;30(7) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taad132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamater P.L., Street E.J., Leslie T.F., et al. Complexity of the basic reproduction number (R0) - volume 25, number 1—January 2019 - emerging infectious diseases journal - CDC. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet] 2019 Jan 1;25(1):1–4. doi: 10.3201/EID2501.171901. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/25/1/17-1901_article [cited 2025 Feb 21] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng Y., Tjaden N.B., Jaeschke A., et al. Evaluating the risk for usutu virus circulation in Europe: comparison of environmental niche models and epidemiological models. Int J Health Geogr [Internet] 2018 Oct 12;17(1) doi: 10.1186/S12942-018-0155-7. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/30314528/ [cited 2025 Feb 20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogels C.B.F., Hartemink N., Koenraadt C.J.M. Modelling west nile virus transmission risk in Europe: effect of temperature and mosquito biotypes on the basic reproduction number. Sci Rep. 2017 Dec 1;7(1) doi: 10.1038/S41598-017-05185-4. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/28694450/ [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y., Lillepold K., Semenza J.C., et al. Reviewing estimates of the basic reproduction number for dengue, zika and chikungunya across global climate zones. Environ Res [Internet] 2020 Mar 1;182 doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2020.109114. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/31927301/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29 doi: 10.1136/BMJ.N71. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/33782057/ [cited 2025 Feb 17];372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Arbovirus Initiative Preparing for the next pandemic by tackling mosquito-borne viruses with epidemic and pandemic potential. https://www.who.int/publications/b/70262 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 20]. Available from:

- 22.Yeo K.L., Chen Y.L., Xu H.Y., et al. Synergistic suppression of dengue virus replication using a combination of nucleoside analogs and nucleoside synthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Apr 1;59(4):2086–2093. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04779-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pires de Mello C.P., Drusano G.L., Rodriquez J.L., et al. Antiviral effects of clinically-relevant Interferon-α and ribavirin regimens against dengue virus in the hollow fiber infection model (HFIM) Viruses. 2018 Jun;10(6) doi: 10.3390/v10060317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang J., Schul W., Butters T.D., et al. Combination of α-glucosidase inhibitor and ribavirin for the treatment of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2011 Jan;89(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diamond M.S., Zachariah M., Harris E. Mycophenolic acid inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing replication of viral RNA. Virology. 2002 Dec;304(2):211–221. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu J.J.H., Yang P.L. c-Src protein kinase inhibitors block assembly and maturation of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Feb;104(9):3520–3525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611681104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choy M.M., Zhang S.L., Costa V.V., et al. Proteasome inhibition suppresses dengue virus egress in antibody dependent infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015 Nov;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J., Park S.J., Park J., et al. Identification of a direct-acting antiviral agent targeting RNA helicase via a graphene oxide nanobiosensor. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021 Jun;13(22):25715–25726. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c04641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S.J., Kim J., Kang S., et al. Discovery of direct-acting antiviral agents with a graphene-based fluorescent nanosensor. Sci Adv. 2020 May;6(22) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz8201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osuna-Ramos J.F., Farfan-Morales C.N., Cordero-Rivera C.D., et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs as potential antivirals: a repurposing approach against flavivirus infections. Viruses. 2023 Jun;15(7) doi: 10.3390/v15071465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Punekar M., Kasabe B., Patil P., et al. A transcriptomics-based bioinformatics approach for identification and in vitro screening of FDA-approved drugs for repurposing against dengue Virus-2. Viruses. 2022 Sep;14(10) doi: 10.3390/v14102150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayala-Nuñez N.V., Jarupathirun P., Kaptein S.J.F., et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection is inhibited by SA-17, a doxorubicin derivative. Antiviral Res. 2013 Oct;100(1):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou L., Zhou J., Chen T., et al. Identification of ascomycin against zika virus infection through screening of natural product library. Antiviral Res. 2021 Dec;196 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quintana V.M., Selisko B., Brunetti J.E., et al. Antiviral activity of the natural alkaloid Anisomycin against dengue and zika viruses. Antiviral Res. 2020 Apr;176 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasquez D.M., Park J.G., Ávila-Pérez G., et al. Identification of inhibitors of ZIKV replication. 2020 Sep 1. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/32961956/ Viruses [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Martinez-Gualda B., Pu S.Y., Froeyen M., et al. Structure-activity relationship study of the pyridine moiety of isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines as antiviral agents targeting cyclin G-associated kinase. Bioorg Med Chem [Internet] 2020 Jan 1;28(1) doi: 10.1016/J.BMC.2019.115188. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/31757682/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zandi K., Bassit L., Amblard F., et al. Nucleoside analogs with selective antiviral activity against dengue fever and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet] 2019;63(7) doi: 10.1128/AAC.00397-19. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/31061163/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soto-Acosta R., Jung E., Qiu L., et al. 4,7-Disubstituted 7 H-Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and their analogs as antiviral agents against zika virus. Molecules. 2021 Jul 1;26(13) doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES26133779. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/34206327/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMillan R.E., Lo M.K., Zhang X.Q., et al. Enhanced broad spectrum in vitro antiviral efficacy of 3-F-4-MeO-Bn, 3-CN, and 4-CN derivatives of lipid remdesivir nucleoside monophosphate prodrugs. Antiviral Res [Internet] 2023 Nov 1;219 doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2023.105718. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/37758067/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Burghgraeve T., Selisko B., Kaptein S., et al. 3’,5’Di-O-trityluridine inhibits in vitro flavivirus replication. Antiviral Res. 2013;98(2):242–247. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2013.01.011. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/23470860/ [Internet] [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez-Gualda B., Saul S., Froeyen M., et al. Discovery of 3-phenyl- and 3-N-piperidinyl-isothiazolo[4,3-b]pyridines as highly potent inhibitors of cyclin G-associated kinase. Eur J Med Chem [Internet] 2021 Mar 5;213 doi: 10.1016/J.EJMECH.2021.113158. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/33497888/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vicenti I., Martina M.G., Boccuto A., et al. System-oriented optimization of multi-target 2,6-diaminopurine derivatives: easily accessible broad-spectrum antivirals active against flaviviruses, influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Med Chem [Internet] 2021 Nov 15;224 doi: 10.1016/J.EJMECH.2021.113683. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/34273661/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J.C., Tseng C.K., Wu Y.H., et al. Characterization of the activity of 2’-C-methylcytidine against dengue virus replication. Antiviral Res. 2015;116:1–9. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2015.01.002. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/25614455/ [Internet] 07 aug 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latour D.R., Jekle A., Javanbakht H., et al. Biochemical characterization of the inhibition of the dengue virus RNA polymerase by beta-d-2’-ethynyl-7-deaza-adenosine triphosphate. Antiviral Res [Internet] 2010 Aug;87(2):213–222. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2010.05.003. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/20470829/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin Z., Chen Y.L., Schul W., et al. An adenosine nucleoside inhibitor of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet] 2009 Dec 1;106(48):20435–20439. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0907010106. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/19918064/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y.L., Yin Z., Lakshminarayana S.B., et al. Inhibition of dengue virus by an ester prodrug of an adenosine analog. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet] 2010 Aug 1;54(8):3255–3261. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00397-10. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/20516277/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niyomrattanakit P., Chen Y.L., Dong H., et al. Inhibition of dengue virus polymerase by blocking of the RNA tunnel. J Virol [Internet] 2010 Jun;84(11):5678–5686. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02451-09. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/20237086/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin C., Yu J., Hussain M., et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel 7-deazapurine nucleoside derivatives as potential anti-dengue virus agents. Antiviral Res [Internet] 2018 Jan 1;149:95–105. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2017.11.005. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/29129706/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen N.M., Tran C.N.B., Phung L.K., et al. A randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial of balapiravir, a polymerase inhibitor, in adult dengue patients. J Infect Dis [Internet] 2013 May 1;207(9):1442–1450. doi: 10.1093/INFDIS/JIS470. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/22807519/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruan J., Rothan H.A., Zhong Y., et al. A small molecule inhibitor of ER-to-cytosol protein dislocation exhibits anti-dengue and anti-zika virus activity. Sci Rep. 2019 Dec 1;9(1) doi: 10.1038/S41598-019-47532-7. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/31358863/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uemura K., Nobori H., Sato A., et al. 5-Hydroxymethyltubercidin exhibits potent antiviral activity against flaviviruses and coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. iScience. 2021 Oct 22;24(10) doi: 10.1016/J.ISCI.2021.103120. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/34541466/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haack P.A., Harmrolfs K., Bader C.D., et al. Thiamyxins: structure and biosynthesis of myxobacterial RNA-virus inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2022 Dec 23;61(52) doi: 10.1002/ANIE.202212946. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/36208117/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sáez-Álvarez Y., De Oya N.J., Del Águila C., et al. Novel nonnucleoside inhibitors of zika virus polymerase identified through the screening of an open library of antikinetoplastid compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021 Sep 1;65(9) doi: 10.1128/AAC.00894-21. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/34152807/ [Internet] [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brai A., Fazi R., Tintori C., et al. Human DDX3 protein is a valuable target to develop broad spectrum antiviral agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet] 2016 May 10;113(19):5388–5393. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1522987113. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/27118832/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang C.F., Gopula B., Liang J.J., et al. Novel AR-12 derivatives, P12-23 and P12-34, inhibit flavivirus replication by blocking host de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018 Dec 1;7(1) doi: 10.1038/S41426-018-0191-1. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/30459406/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Constant D.A., Mateo R., Nagamine C.M., et al. Targeting intramolecular proteinase NS2B/3 cleavages for trans-dominant inhibition of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Oct 2;115(40):10136–10141. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1805195115. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/30228122/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kühl N., Lang J., Leuthold M.M., et al. Discovery of potent benzoxaborole inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main and dengue virus proteases. Eur J Med Chem [Internet] 2022 Oct 5;240 doi: 10.1016/J.EJMECH.2022.114585. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/35863275/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCormack C.P., Goethals O., Goeyvaerts N., et al. Modelling the impact of JNJ-1802, a first-in-class dengue inhibitor blocking the NS3-NS4B interaction, on in-vitro DENV-2 dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol [Internet] 2023 Dec 1;19(12) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PCBI.1011662. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/38055683/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu B., Mason P., Wang L., et al. Antiviral profiles of novel iminocyclitol compounds against bovine viral diarrhea virus, west nile virus, dengue virus and hepatitis B virus. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2007;18(1):49–59. doi: 10.1177/095632020701800105. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/17354651/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liang P.H., Cheng W.C., Lee Y.L., et al. Novel five-membered iminocyclitol derivatives as selective and potent glycosidase inhibitors: new structures for antivirals and osteoarthritis. Chembiochem [Internet] 2006 Jan;7(1):165–173. doi: 10.1002/CBIC.200500321. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/16397876/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaptein S.J.F., Goethals O., Kiemel D., et al. A pan-serotype dengue virus inhibitor targeting the NS3-NS4B interaction. Nature. 2021 Oct 21;598(7881):504–509. doi: 10.1038/S41586-021-03990-6. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/34616043/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riva V., Garbelli A., Brai A., et al. Unique domain for a unique target: selective inhibitors of host cell DDX3X to fight emerging viruses. J Med Chem [Internet] 2020 Sep 10;63(17):9876–9887. doi: 10.1021/ACS.JMEDCHEM.0C01039. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/32787106/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zephyr J., Rao D.N., Johnson C., et al. Allosteric quinoxaline-based inhibitors of the flavivirus NS2B/NS3 protease. Bioorg Chem [Internet] 2023 Feb 1;131 doi: 10.1016/J.BIOORG.2022.106269. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/36446201/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li L., Basavannacharya C., Chan K.W.K., et al. Structure-guided discovery of a novel non-peptide inhibitor of dengue virus NS2B-NS3 protease. Chem Biol Drug Des [Internet] 2015 Sep 1;86(3):255–264. doi: 10.1111/CBDD.12500. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/25533891/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lim S.P., Noble C.G., Seh C.C., et al. Potent allosteric dengue virus NS5 polymerase inhibitors: mechanism of action and resistance profiling. PLoS Pathog. 2016 Aug 1;12(8) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PPAT.1005737. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/27500641/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho V., Yong H.Y., Chevrier M., et al. RIG-I activation by a designer short RNA ligand protects human immune cells against dengue virus infection without causing cytotoxicity. J Virol [Internet] 2019 Jul 15;93(14) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00102-19. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/31043531/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pryke K.M., Abraham J., Sali T.M., et al. A novel agonist of the TRIF pathway induces a cellular state refractory to replication of zika, chikungunya, and dengue. Viruses mBio. 2017 May 1;8(3) doi: 10.1128/MBIO.00452-17. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/28465426/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Recalde-Reyes D.P., Rodríguez-Salazar C.A., Castaño-Osorio J.C., et al. PD1 CD44 antiviral peptide as an inhibitor of the protein-protein interaction in dengue virus invasion. Peptides (NY) 2022 Jul 1;153 doi: 10.1016/J.PEPTIDES.2022.170797. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/35378215/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie P.W., Xie Y., Zhang X.J., et al. Inhibition of dengue virus 2 replication by artificial micrornas targeting the conserved regions. Nucleic Acid Ther [Internet] 2013 Aug 1;23(4):244–252. doi: 10.1089/NAT.2012.0405. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/23651254/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin M.H., Li D., Tang B., et al. Defective interfering particles with broad-acting antiviral activity for dengue, zika, yellow fever, respiratory syncytial and SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Dec 21;10(6) doi: 10.1128/SPECTRUM.03949-22. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/36445148/ [cited 2025 Feb 3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alhoot M.A., Wang S.M., Sekaran S.D. Inhibition of dengue virus entry and multiplication into monocytes using RNA interference. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2011 Nov;5(11) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0001410. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.unibs.it/22140591/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]