Abstract

Background

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a draft guidance document detailing core patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials, including physical function (PF). The objectives of this study were to develop analytic methods and visualizations of patient-reported PF in patients with cancer.

Methods

We applied an estimand framework to a patient-reported tolerability endpoint to develop data summaries cross-sectionally and over time, along with visualizations. We accomplished this through iterative feedback with clinicians, statisticians, and FDA stakeholders using three clinical trial datasets in hematologic malignancies. Graphical approaches were applied to three datasets in hematologic malignancies: (1) patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms enrolled in MPN-RC 111/112 trials completed EORTC QLQ-C30 over 12 months; (2) patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing CAR-T cell therapy or autologous transplant who completed FACT questionnaires over 6 months; and (3) patients with multiple myeloma or amyloidosis who completed the PROMIS-29 questionnaire over 6 months. Zoom polls were administered to two stakeholder groups (clinicians/clinical investigators and patient advocates) to elicit feedback.

Results

Visualizations included stacked bar charts, line plots of arithmetic mean changes from baseline, pie charts, waffle plots, and waterfall plots of PF data. Graphics considered scaled scores and individual items and included delineation of PRO completion rate at each time point. Confidence intervals and reference lines were included as applicable, and colorblind accessible colors were implemented to ensure inclusivity of all visualizations. Data summaries over time reporting “worst” change were difficult to interpret. In terms of stakeholders’ preference, patients preferred stacked bar charts while clinicians equally favored stacked bar charts and line plots; both patients and clinicians preferred waterfall plots to pie charts. Patient feedback highlighted the need for various graphics to convey group level trends and granular individual-patient level information.

Conclusion

Patient-reported PF informs the evaluation of treatment tolerability in cancer trials. Data summaries and visualizations of physical function developed through an iterative process were reviewed favorably by patients, clinicians and FDA stakeholders in this study. Future work to systematically assess accuracy of interpretation of the various analytic and visualization methods is a necessary next step across clinical, regulatory, payer and patient stakeholders.

Trial registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12874-025-02617-y.

Keywords: Physical function, Treatment tolerability, Cancer, Longitudinal analysis, Graphics

Background

Cancer treatment tolerability has been defined as the degree to which symptomatic and non-symptomatic adverse events (AEs) of a cancer drug or regimen affect the ability or desire of the patient to adhere to the dose or intensity of therapy and represents an important clinical outcome in cancer clinical trials in addition to the safety and efficacy of the drug or regimen [1]. Tolerability has historically been informed by safety parameters, including conventional clinician-based assessments such as grading of toxicities and notation of dose reductions and delays. However, a comprehensive understanding of tolerability also necessitates collection of information directly from patients themselves through patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has defined in a draft guidance five core PRO domains for collection on cancer clinical trials which can inform a drug’s effect on the patient and their disease. The core domains include physical function, disease-related symptoms, adverse effects of treatment, role function and overall side effect impact or bother [2]. FDA have also provided a guidance document on technical specifications for submitting PRO data in cancer clinical trials applicable to these core domains [3].

Overall side effect impact and patient-reported treatment related symptoms, particularly information about interference with daily activities, can provide important tolerability information where clinician-reported data may fall short. Symptom improvement due to treatment efficacy will be countered by symptom burden from any symptomatic side effects, and this net effect can be evaluated by a treatment’s impact on physical function. Physical function, the ability to carry out day-to-day activities that require physical effort, [4] is therefore central to characterizing a patient’s treatment experience and daily life. Measuring physical function accurately while a patient is on treatment can be a crucial component to a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s treatment experience and the tolerability of cancer drugs and regimens.

Regulatory reviewers are tasked with evaluating the safety and efficacy of novel treatments. Thus, FDA is interested in how patients tolerate treatment on registrational trials. Importantly, PRO data may also inform early phase trials that are seeking to identify an optimal dose; one that achieves benefit with the least side effect burden. FDA and others in cancer drug development would benefit from a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of patient’s physical function while on therapy. There is a need to develop analytical approaches and visualizations of tolerability information, such as physical function data, that can create a more standard approach to inform various stakeholders in clinical and regulatory settings [5, 6].

There are various approaches to analyzing and presenting PRO data to patients and clinicians. Graphics of some types of PRO data have been tested among patients and clinicians for preference and accuracy of interpretation [7]. Not surprisingly, these studies identified that a single format may not work for both clinicians and patients and that comprehension was variable. Previous work by Brundage and Snyder included a mixed-methods study to evaluate various data formats [8] and a modified Delphi process to develop evidence-based recommendations for PRO display with stakeholders including survivors/caregivers, oncologists, PRO researchers and other stakeholders [9]. The resulting recommendations aimed to improve accurate and meaningful interpretation of PRO data.

While this previous work has created a helpful starting point, it was not specific to physical function, symptomatic adverse events or any other specific PRO instrument or measurement construct. The core PROs identified in the FDA draft guidance merit further investigation to optimize visualization of physical function from multiple stakeholders. The FDA has spearheaded some of this work in regard to the visualization of patient-reported symptomatic adverse events (AEs), by developing a tool called Project Patient Voice [10], where clinical trial data are presented in multiple formats for use by clinicians and patients. However, the tools have not been tested for interpretability and its approaches have not been expanded to other core outcomes, such as physical function.

Given the relevance of patient-reported physical function data in understanding cancer treatment tolerability, particularly with the advent of multiple novel and often chronically administered therapeutics in hematologic malignancies, [11, 12] we performed an analytic study to develop and test longitudinal graphics of physical function. Our objectives were to develop an estimand framework [13] of patient-reported physical function as a tolerability endpoint and to develop data summaries cross-sectionally and over time with companion visualizations. To that end, we utilized three datasets in hematologic malignancies to ensure the approaches were applicable to patients with rare cancers in small and larger datasets. These included a clinical trial in myeloproliferative neoplasms and two prospective studies: in patients receiving CAR-T or autologous transplant or treatment for multiple myeloma or amyloidosis. Herein we report on the analytic and graphical approaches that were developed as part of an iterative process between clinicians, statisticians and FDA stakeholders, as well as the initial testing of these graphics with patient advocates and additional clinicians and investigators.

Methods

Trial data sets & assessments

We reviewed a published estimand and modified it for a physical function endpoint (Supplemental Table S2) [9]. The estimand framework provides an approach to aligning a clinical trial’s objective with the study endpoints and analysis, and can facilitate analysis and interpretation of PRO results. We applied the estimand framework to three data sources for consistency in calculating physical function data summaries.

Data sources were selected to represent potentially rare diseases and for different tools commonly used to measure physical function. MPN-RC 111/112 enrolled patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms receiving hydroxyurea alone (MPN 111, NCT01259817) or hydroxyurea versus peglyated interferon-alpha (MPN 112, NCT01259856). The data were pooled for analysis as was done in the publication of quality of life results from these studies [14]. In both trials, participants completed EORTC QLQ-C30 (five items within one PF scale) at registration and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months later. As a second data source, we applied the same framework to an observational “financial toxicity” study in patients with multiple myeloma or amyloidosis which collected PROMIS-29 (four items within one PF scale) at registration and 3 and 6 months later. Lastly, the framework was also applied to a study of quality of life among patients receiving CAR-T cell therapy versus stem cell transplant which collected FACT-G questionnaires at baseline, week 2, and months 1–6.

Physical function scales

Patient-reported physical function was measured using three tools across these studies. Within the EORTC QLQ-C30, [15, 16] physical function is scaled from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the best possible physical function score. It is calculated from responses to 5 items, ranging from “Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or a suitcase?” to “Do you need help with eating, dressing, washing yourself or using the toilet?” Response options are on a 4-point scale from “not at all” to “very much”. Within the PROMIS-29 [17], physical function is measured using the PROMIS Short Form Physical Function 4a Scale which includes 4 questions about ability to do chores, go up and down stairs, walk for 15 min, and run errands. Response options are on a 5-point scale ranging from “without any difficulty” to “unable to do.” Physical function score is reported on a T scale and interpreted relative to a mean of 50 (standard deviation of 10) as representing average physical function for a healthy adult in the US population. A higher T score represents better physical functioning. One of the trials also used the FACT-G questionnaire. While the FACT-G Physical Well Being scale (PWS) [18] is not a well-defined physical function measure, it was used as an available data set to evaluate the analytic and visualization methods and does have some items that are related to tolerability. Within the FACT-G, physical well-being is measured on a 0 to 28 scale with 28 representing the best possible physical well-being. It is calculated by summing the responses to 7 items, such as “I have lack of energy” and “Because of my physical condition, I have trouble meeting the needs of my family.” It includes the FACT GP5 item which states “I am bothered by side effects of treatment.” Response options for FACT-G items are on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” See the user manual for each questionnaire for scoring documentation for each questionnaire for proper scoring guidance including missing items.

PRO results were categorized as “improved,” “maintained” and “declined” in selected visualizations. For cross-sectional visualizations, “improved” was defined as a ≥ 10-point improvement from baseline at a fixed timepoint (e.g., 6 months) on the QLQ-C30 and the PROMIS-29. “Declined” was defined as a ≥ 10-point decline from baseline for each questionnaire [19, 20]. “Maintained” was defined as changes not meeting the criteria for improvement or decline. For categorizing patients within visualizations, a patient was considered as “improved” if all scores during the observation period (e.g., first 6 months) were ≥ 10-points improved from baseline, “declined” if any score during the observation period was a ≥ 10-point decline from baseline, and otherwise considered as “maintained”.

Iterative feedback

Within an iterative feedback phase, a small team of health outcomes researchers generated potential graphical representations of patient-generated data based on graphics previously recommended for the display of toxicity information [21–23], patient-reported outcomes [24], graphics suggested during the 6th Annual FDA Clinical Outcomes Assessment in Cancer Clinical Trials Workshop [25] graphics related to display of patient-reported symptomatic adverse events [8, 26, 27] and graphics from Project Patient Voice, [8] as well as their own experience graphing traditional clinical outcomes in clinical trials. Potential graphical representations were presented to US FDA stakeholders during monthly videoconferences and iterative feedback was used to refine final representations.

Structured feedback on graphics was also collected from two Zoom polls of health outcomes researchers and patient advocates in the National Clinical Trials Network Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The zoom poll included 6 questions that asked respondents to select between pairs of graphical representations. Respondents could select preference for one, the other, none or both. Responses to the survey were anonymous and deemed IRB exempt. Brief discussion followed completion of the zoom poll.

Statistical analysis

Completion rate for each trial was defined as the number of patients who completed the PRO assessment over the number of patients expected to complete the PRO assessment, consistent with the definition proposed by the Setting International Standard in Analyzing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints [28]. Zoom poll results were described within each cohort of respondents using descriptive statistics.

Results

Datasets

The MPN-RC trials accrued a total of 269 patients from 2011–2016 and has been previously reported. [10] The financial toxicity study accrued a total of 116 patients from 2019 to 2021. The CAR-T Quality of Life study accrued a total of 67 patients from 2018 to 2020. Completion rates in these studies ranged from 70.8–100%.

A representative table of PRO Completion from the MPN-RC study is shown in the appendix (Supplemental Table S1). Such a table is important to account for each participant on the trial, whether they are expected or not expected to complete PROs and when PROs were completed. This table also displays intercurrent events such as deaths, progression and discontinuations due to adverse events or other reasons which excluded patients from consideration in point estimates per our selected estimand (Supplemental Table S2).

Longitudinal graphics of physical function

Stacked bar charts

The stacked bar chart is a concise but comprehensive graphical method that can be used to display scale data such as physical function domain results (Fig. 1, Panel A) or response distribution to individual items (Fig. 1, Panel B). These bar charts represent the distribution of change from baseline scores or responses among all patients who completed the survey at each time point. Bar charts representing all patients who were expected to respond were also produced; however, interpreting such bar charts was difficult because the height of the bars was impacted by the proportion of patients who did not complete surveys. To display continuous scales (Fig. 1A), meaningful categorization (e.g. improved, maintained, declined) was needed. Since the original nature of the score was continuous (0 to 100 scale), categorizing patients as “improved,” “maintained” or “declined” may be arbitrary and can potentially misclassify patients into the wrong health state. When using stacked bar charts, categories should be clearly defined and justified.

Fig. 1.

Stacked Bar Charts. A Change in a physical function scale. B Change in individual physical function items

Individual items responses (Fig. 1B) are easier to display in a stacked bar chart because responses are already categorized. Here the physical function tasks being queried in each item have been ordered from top of the figure to bottom to represent least impairment (ex. difficulty completing a strenuous activity) to most impairment in physical function (ex. difficulty with eating, dressing and washing). Display of the individual items can help to communicate more tangible impairments to patients and clinicians to aide in interpretation of bar charts based on scale scores only.

In bar charts, the “declined” category appears at the bottom to allow for visual inspection of changes over time most easily in the proportion of patients in this category. An alternative visualization would be to split the “declined” category below the axis and “improved/stable” above the y-axis (as in Supplemental Figure S1).

In these and all graphical representations, the number of patients completing surveys, the number of patients expected to complete surveys, and the completion rate (PRO Completed/PRO Expected) at each time point are displayed. Such accounting is important to communicate the population included in the visualization and delineate patterns of missing data.

In bar charts and other applicable representations, the color palette was selected to be compliant with the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) and to be colorblind accessible. Contrasting colors as opposed to shades were chosen to be easy to discriminate. Reddish/orange colors were typically selected to represent unfavorable categories (ex. “declined” group in scales) while colors in the blue/green range represent more favorable outcomes (ex. “not at all” response in individual items). Color palettes were consistent with those currently employed in FDA’s Project Patient Voice. Palettes were tested using the colorblind R package, which allows you to simulate what figures would look like to a person who has a color-vision deficiency [29].

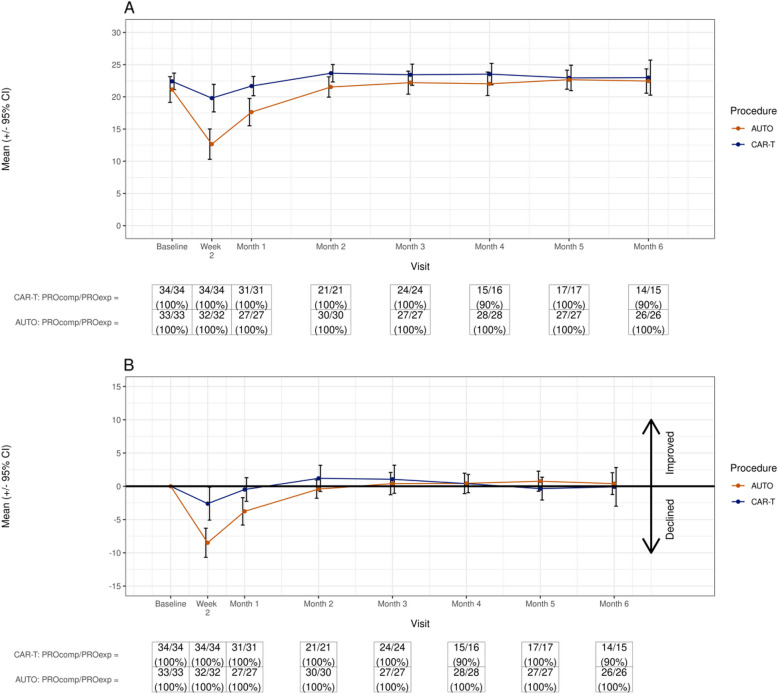

Line plots

The line plot depicts a readily comprehensible trajectory of physical function that can identify temporal patterns at the group level with arithmetic (raw) means of scale scores in each group (Fig. 2A) or highlight changes from baseline zeroed scores (Fig. 2B). Differences can be identified with confidence intervals and reference lines, and arrows to signify directionality of declines or improvements. Questionnaire completion information is included for each timepoint. While simple depiction of trajectory is the strength of this graphic, it does not communicate the individual patient experience.

Fig. 2.

Line Plots. A Change in a physical function scale (raw mean). B Change in physical function scale (raw mean with change from baseline)

Stacked bar chart & line plot combination

Interpretation of trajectories together with responses to single items may help more concretely elucidate what may be driving patterns of physical function and other PROs reflecting tolerability. In Fig. 3, a dip in FACT-G Total Score is more pronounced in patients receiving autologous transplant than CAR-T, and in both groups tracks with responses to the FACT GP5 question. Similar analysis can be completed with physical function scales, as shown in Supplemental Figure S2 in which a line plot of responses over time to QLQ-C30 physical function scale is shown along with responses to the question “Have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or suitcase?” These plots allow the viewer to integrate the pattern in the scaled scores with the pattern in individual item responses. This achieves increased granularity and an understanding of features that might be driving group-level changes.

Fig. 3.

Line plot of FACT-G total score over stacked bar chart of responses to FACT-GP5 item (“I am bothered by side effects of treatment”) in patients receiving autologous stem cell transplant versus CAR-T cell therapy

Pie charts and waffle plots

Pie charts offer a familiar and easily interpretable representation of statistics to patients and clinicians. In Fig. 4, physical function T score is depicted at a single pre-defined timepoint of 6 months to give a sense of how a patient who remained on the cancer therapy for 6 months might be functioning at that time point. The cubes in the waffle are scaled and numbers representing the percent in each category of “improved,” “maintained” or “declined” further clarify that in this study, most patients had maintained their physical function at 6 months on treatment. In an alternate approach, waffle plots and pie charts can depict a data summary of physical function percent over a certain time frame (Supplemental Figure S3). While this plot seemingly describes data in a succinct fashion, defining the categories of “improved” and “declined” over several intervening points is not straightforward and may pose challenges to interpretation of the plot (e.g., “improvement” requires improvement at all observed time points, while “decline” only requires a single observation of worsening).

Fig. 4.

Waffle plot (A) and Pie Chart (B) of Physical Function T-score from PROMIS physical function questionnaire from single arm study of patients receiving treatment for multiple myeloma and amyloidosis

Waterfall plot

A waterfall plot depicts individual patient trajectories as each line represents a single patient’s experience. It is easy to appreciate in the waterfall plot (Fig. 5) that while most patients had stable physical function, few experienced a large improvement and a fair number of patients on this study, particularly in the hydroxyurea arm, experienced a worsening of physical function after six months on therapy. This plot is a combination of response plus magnitude, providing the group level proportions (e.g., percentage in each category of improvement, stable, and worsening) but also showing the granular experience of individual patients. It is advantageous for detail it can provide on each patient. However, comparison between arms may be difficult to the eye on larger studies with more subtle differences.

Fig. 5.

Waterfall plot of change in physical function at 6 months on hydroxyurea or pegylated-interferon at 6 months

Stakeholder feedback: clinicians and clinical investigators

Structured feedback on graphics was collected from health outcomes researchers in the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (Alliance). Respondents from the Health Outcomes Committee (17 meeting participants) largely identified as clinicians (36%) but also included clinical or translational researchers (27%), statisticians (5%), Alliance or other administrators (14%), industry representatives (5%) and a patient advocate (5%). This group demonstrated a preference toward the pie chart (38%) as opposed to the waffle plot (33%) though a substantial number indicated they liked them equally (24%) and some indicated they disliked both (5%). When shown line plots, the group preferred group mean changes from baseline (44%) over group means over time (28%), with some preferring to see both options (28%) and no one indicating a dislike for both. Respondents demonstrated a slight preference toward the line plot (42%) over the stacked bar chart (37%), but many indicated liking both equally (16%) while a minority disliked both (5%). When asked which data was preferred for representation in the pie chart– a longitudinal data summary over 6 months versus a cross-sectional summary at 6 months– there was a substantial preference for the longitudinal approach (47%) over the cross-sectional measure at 6 months (18%), with a substantial number of respondents indicating they like them both equally (35%) and no one disliking them both. When shown the waterfall plot displaying cross sectional physical function scale data at 6 months compared to a pie chart displaying similar data, there was a preference toward the waterfall plot (60% waterfall plot, 25% pie chart, 10% liked equally, 5% disliked both).

Stakeholder feedback: patient advocates

Feedback on these graphics was additionally collected from patient advocates in the NCTN Alliance Patient Advocate Committee. 14 meeting participants were patient advocates (90%) with a few 10% other categories. This group demonstrated a preference toward the pie chart (54%) as opposed to the waffle plot (15%) though a substantial proportion indicated they liked them equally (23%) and few disliked both (8%). When shown line plots, the group preferred seeing both the group mean changes from baseline and the group means over time (46%) and an equal number preferred the group means over time (15%) and group mean changes from baseline (15%). A substantial amount indicated they disliked both (23%). Respondents demonstrated a preference toward the stacked bar chart (58%) over the line plot (17%), but many indicated liking both equally (17%) while a minority disliked both (8%). When asked which data was preferred for representation in the pie chart– a longitudinal -data summary over 6 months versus a cross-sectional summary at 6 months– there was an equal preference between cross sectional measure at 6 months (33%), the longitudinal approach (33%), and liking them both equally (33%), and no one disliking them both. When shown the waterfall plot displaying cross sectional physical function scale data at 6 months compared to a pie chart displaying similar data, there was a preference toward the waterfall plot (57% waterfall plot, 36% pie chart,7% liked equally, 0% disliked both).

Patient advocate and clinician/clinical investigator preferences are summarized in Supplemental Table S3. Additional qualitative feedback from the patient advocates was collected during a discussion following the Zoom poll; comments from the patient advocates on these graphics is described in Supplemental Table S4.

Discussion

Physical function is a key outcome in the measurement of treatment tolerability in patients with cancer receiving anticancer therapies. In this study, we evaluated three clinical trial datasets of patients with hematologic malignancies who completed a variety of questionnaires relating to tolerability of cancer treatment. We focused on two well defined physical function scales and tolerability elements from a general PRO measure over time and developed graphical representations of this data with iterative feedback from clinicians, statisticians and stakeholders. We then presented the graphics to an external group of clinicians, clinical investigators and patient advocates for additional preliminary feedback. To our knowledge, this report represents the first effort to develop systematic, longitudinal, graphical representations of physical function over time in patients receiving treatment for cancer for use by multiple stakeholders including patients, clinicians, clinical trialists and regulators. We used relatively small clinical trials of less common hematologic malignancies because data in such cases should be used to its maximum potential. The visualization techniques demonstrated here can be easily applied to larger datasets of clinical trials for more common diseases.

A variety of graphics were developed to convey different information. Visualizations and summaries of PRO data should be based on the research objective of interest using the estimand framework. Stacked bar charts can demonstrate between group comparisons of physical function scale data or frequency of responses to individual items. Visualizations, such as stacked bar charts, that rely on categorizing data from scales require a"threshold"change which requires a rationale for its selection. Line plots demonstrate an intuitive visualization of trajectory of physical function as compared between study arms over time. Selection of an appropriate visualization should consider the format of the underlying data and whether it is appropriate to calculate a mean. Pie charts and waffle plots demonstrate cross sectional data on physical function to depict proportions of patients with improved, maintained or declined physical function at a given timepoint. Waterfall plots demonstrate individual patient trajectories at high granularity, offering a view into how each study participant’s physical function fared on treatment, while also providing group level data in a visualization that is familiar to most clinicians. Every analysis of PRO data should include a table related to attrition and completion rate. For this purpose, example completion tables were generated in this study. These tables could be further enhanced by including granular reasons for missing PRO data which were not available in the datasets in this study.

In gathering feedback on the variety of plots generated, consideration to the intended audience matters as patients preferred plots that were at times less preferred by clinicians or investigators, and thus a host of different representations for different audiences may be needed. Patients and patient advocates are, not unexpectedly, a heterogeneous group among themselves. Some favor less detail and some more. Some would like their physicians to convey this information to them, while some appreciate the ability to evaluate the data themselves. As has been done with Project Patient Voice, an approach for patients and clinicians that displays a variety of graphics and can go from simplest to most complex appears optimal.

The limitations of this study include the restricted scope of the qualitative feedback. However, we did include patients and clinicians as a first step in development of these visualizations. Additionally, the application of these methods to clinical trial datasets in less common diseases could be viewed as a limitation and these methods should be tested in additional datasets. The graphics developed here provide the basis for further work to test the accuracy of interpretation more formally by different stakeholders through formal quantitative and qualitative feedback. To enable statisticians, regulators, and clinicians to easily use these graphics with PRO datasets from cancer patients in clinical trials or practice, we have developed an R package. It is available at https://duecklab.github.io/

Conclusions

A range of analytic methods and visualizations of PF were developed through an iterative process in this study. Feedback on graphics from patients, clinicians and FDA stakeholders was favorable. These approaches can be used as an important starting point for the field to build upon with a goal to improve our evaluation of treatment tolerability in cancer clinical trials.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- PF

Physical Function

- AEs

Adverse Events

- PROs

Patient-reported outcomes

- ADA

Americans with Disability Act

- NCTN

National Clinical Trials Network

- Alliance

Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Authors’ contributions

GT, VB, PGK, and ACD conceived and designed the analysis. RH, JM, RM, SS, and RW contributed study data. ACD, BNN, and GT performed the analysis and created the visualizations. GT, BNN, VB, TYC, MF, MM, PGK, and ACD participated in iterative feedback sessions. GT, BNN, and ACD wrote the initial draft of the paper. Finally, GT, BNN, VB, TYC, MF, RH, MJ, JM, RM, MM, JR, SS, RW, PGK, and ACD critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Oncology Center of Excellence, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award [Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation, U01FD005938] totaling $167,314 with 100 percent funded by FDA/HHS. It has also been supported by United States National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants P01CA108671 (PI R. Hoffman) and P30CA015083 (PI C. Willman).

Data availability

The authors will make deidentified clinical trial data available upon reasonable request. Inquiries can be sent to duecklab@mayo.edu.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All trials were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at each site and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. This study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Mayo Clinic IRB deemed secondary analysis of clinical trial data and anonymous Zoom polling of stakeholder preferences as exempt (IRB# 22–010586).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Friends of Cancer Research. Broadening the Definition of Tolerability in Cancer Clinical Trials to Better Measure the Patient Experience. 2018. Website: https://friendsofcancerresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/Comparative-Tolerability-Whitepaper_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 2.U.S Food and Drug Administration. Core Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials. 2021. Website: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/core-patient-reported-outcomes-cancer-clinical-trials. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Submitting Patient-Reported Outcome Data in Cancer Clinical Trials. 2023. Website: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/submitting-patient-reported-outcome-data-cancer-clinical-trials. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 4.U.S Food and Drug Association. 6th Annual Clinical Outcome Assessment in Cancer Clinical Trials Workshop. In Proceedings of the FDA Public Workshop. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-meetings-conferences-and-workshops/fda-public-workshop-6th-annual-clinical-outcome-assessment-cancer-clinical-trials-workshop-07212021. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 5.Major A, Dueck AC, Thanarajasingam GT. Beyond maximum grade: advancing the measurement and analysis of adverse events in malignant haematology trials in the modern era. Lancet Haematol. 2025;12(6):e451–62. 10.1016/s2352-3026(25)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatnagar V, Dueck AC, Efficace F, et al. Beyond maximum grade: using patient-generated data to inform tolerability of treatments for haematological malignancies. Lancet Haematol. 2025;12(6):e463–9. 10.1016/s2352-3026(25)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder C, Brundage M, Smith KC, Bantug ET, Tolbert EE, Little E, Blackford AL, Aaronson NK, Ganz PA, Garg R, Fisch M, Hoffman V, Reeve BB, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Stovall E, Zachary M. Testing Ways to Display Patient-Reported Outcomes Data for Patients and Clinicians. Washington (DC): Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); 2018. PMID: 37315167. [PubMed]

- 8.Brundage MD, Smith KC, Little EA, Bantug ET, Snyder CF; PRO Data Presentation Stakeholder Advisory Board. Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2457–72. 10.1007/s11136-015-0974-y. Epub 2015 May 27. PMID: 26012839; PMCID: PMC4891942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Snyder C, Smith K, Holzner B, Rivera YM, Bantug E, Brundage M; PRO Data Presentation Delphi Panel. Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(2):345–356. 10.1007/s11136-018-2020-3. Epub 2018 Oct 10. PMID: 30306533; PMCID: PMC636386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Association. (2023, March 17). Project Patient Voice. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-patient-voice

- 11.Thanarajasingam GT, Major A, Bhatnagar V, et al. Beyond maximum grade: introduction to The Lancet Haematology Adverse Events Reporting Series. Lancet Haematol. 2025;12(6):e403–6. 10.1016/s2352-3026(25)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bröckelmann PJ, Scheffer Cliff ER, Iacoboni G, et al. Beyond maximum grade: tolerability of immunotherapies, cellular therapies, and targeted agents in haematological malignancies. The Lancet Haematology. 2025;12(6):e470–81. 10.1016/S2352-3026(25)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiero MH, Pe M, Weinstock C, King-Kallimanis BL, Komo S, Klepin HD, Gray SW, Bottomley A, Kluetz PG, Sridhara R. Demystifying the estimand framework: a case study using patient-reported outcomes in oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):e488–94. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30319-3. (PMID: 33002444). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazza GL, Mead-Harvey C, Mascarenhas J, Yacoub A, Kosiorek HE, Hoffman R, Dueck AC, Mesa RA; Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research Consortium (MPN-RC) 111 and 112 trial teams. Symptom burden and quality of life in patients with high-risk essential thrombocythaemia and polycythaemia vera receiving hydroxyurea or pegylated interferon alfa-2a: a post-hoc analysis of the MPN-RC 111 and 112 trials. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(1):e38-e48. 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00343-4. PMID: 34971581; PMCID: PMC9098160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (3rd Edition). Published by: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels 2001.

- 16.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. (PMID: 8433390). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PROMIS Scoring Manuals, PROMIS Profile (Adult) Scoring Manual. Available at http://www.healthmeasures.net/promis-scoring-manuals. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 18.FACIT.org, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General Scoring Manual. Available at http://www.facit.org/measures/fact-g. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 19.Coon CD, Schlichting M, Zhang X. Interpreting Within-Patient Changes on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC13. Patient. 2022;15(6):691–702. 10.1007/s40271-022-00584-w. Epub 2022 Jun 30. PMID: 35771392; PMCID: PMC9585005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bingham CO, Butanis AL, Orbai AM, Jones M, Ruffing V, Lyddiatt A, Schrandt MS, Bykerk VP, Cook KF, Bartlett SJ. Patients and clinicians define symptom levels and meaningful change for PROMIS pain interference and fatigue in RA using bookmarking. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(9):4306–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab014. (PMID:33471127;PMCID:PMC8633670). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanarajasingam G, Atherton PJ, Novotny PJ, Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Grothey A. Longitudinal adverse event assessment in oncology clinical trials: the Toxicity over Time (ToxT) analysis of Alliance trials NCCTG N9741 and 979254. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(5):663–70. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00038-3. Epub 2016 Apr 12. PMID: 27083333; PMCID: PMC4910515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Thanarajasingam G, Leonard JP, Witzig TE, Habermann TM, Blum KA, Bartlett NL, Flowers CR, Pitcher BN, Jung SH, Atherton PJ, Tan A, Novotny PJ, Dueck AC. Longitudinal Toxicity over Time (ToxT) analysis to evaluate tolerability: a case study of lenalidomide in the CALGB 50401 (Alliance) trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e490–7. 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30067-3. (PMID:32470440;PMCID:PMC7457391). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thanarajasingam G, Minasian LM, Baron F, Cavalli F, De Claro RA, Dueck AC, El-Galaly TC, Everest N, Geissler J, Gisselbrecht C, Gribben J, Horowitz M, Ivy SP, Jacobson CA, Keating A, Kluetz PG, Krauss A, Kwong YL, Little RF, Mahon FX, Matasar MJ, Mateos MV, McCullough K, Miller RS, Mohty M, Moreau P, Morton LM, Nagai S, Rule S, Sloan J, Sonneveld P, Thompson CA, Tzogani K, van Leeuwen FE, Velikova G, Villa D, Wingard JR, Wintrich S, Seymour JF, Habermann TM. Beyond maximum grade: modernising the assessment and reporting of adverse events in haematological malignancies. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e563-e598. 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30051-6. Epub 2018 Jun 18. Erratum in: Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(3):e121. PMID: 29907552; PMCID: PMC6261436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Snyder C, Smith K, Holzner B, Rivera YM, Bantug E, Brundage M; PRO Data Presentation Delphi Panel. Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(2):345–356. 10.1007/s11136-018-2020-3. Epub 2018 Oct 10. PMID: 30306533; PMCID: PMC6363861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Public Workshop: 6th Annual Clinical Outcome Assessment in Cancer Clinical Trials Workshop. 2021. Website: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-meetings-conferences-and-workshops/fda-public-workshop-6th-annual-clinical-outcome-assessment-cancer-clinical-trials-workshop-07212021. Accessed 11 July 2025.

- 26.Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Ravi V, Attia S, Deshpande HA, Gupta AA, Milhem MM, Conry RM, Movva S, Pishvaian MJ, Riedel RF, Sabagh T, Tap WD, Horvat N, Basch E, Schwartz LH, Maki RG, Agaram NP, Lefkowitz RA, Mazaheri Y, Yamashita R, Wright JJ, Dueck AC, Schwartz GK. Sorafenib for Advanced and Refractory Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2417–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805052. (PMID:30575484;PMCID:PMC6447029). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basch E, Becker C, Rogak LJ, Schrag D, Reeve BB, Spears P, Smith ML, Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Schwartz GK, Bennett AV, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS, Sloan JA, Bruner DW, Schwab G, Atkinson TM, Thanarajasingam G, Bertagnolli MM, Dueck AC. Composite grading algorithm for the National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Clin Trials. 2021;18(1):104–114. 10.1177/1740774520975120. Epub 2020 Dec 1. PMID: 33258687; PMCID: PMC7878323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Setting International Standards in Analysing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints. Website: https://www.sisaqol-imi.org/

- 29.McWhite C, Wilke C (2024). _colorblindr: Simulate colorblindness in R figures_. R package version 0.1.0, URL https://github.com/clauswilke/colorblindr.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make deidentified clinical trial data available upon reasonable request. Inquiries can be sent to duecklab@mayo.edu.