Malaria is a preventable mosquito-borne illness caused by plasmodium parasites. An estimated 263 million cases of malaria and 597,000 deaths from malaria occurred worldwide in 2023.1 Nearly half the global population lives in regions where malaria is endemic, and outbreaks of locally acquired infection can also occur in regions where malaria is not endemic, such as the United States.2 Malaria therefore represents a major global public health challenge. Recent progress in the fight against malaria includes the introduction of malaria vaccines to prevent infection in children residing in regions where malaria is endemic. In addition, malaria-control efforts between 2000 and 2024 have led the World Health Organization (WHO) to certify 18 additional countries as malaria-free.1 However, achievements in combating malaria have been tempered by parasite and vector adaptations. The resulting challenges include a reduction in the reliability of rapid diagnostic tests and the emergence of partial resistance to artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum and insecticide resistance in the mosquito vectors.3 We review the current epidemiologic trends of malaria and the best practices, recent progress, and challenges in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of this deadly infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Malaria is a clinical illness that is inextricably linked to environmental conditions and sociodemographic factors, such as poverty.3,4 Plasmodium species and their vectors are widespread, and persons residing in or traveling to sub-Saharan Africa and malaria-endemic regions in Southeast Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions, and the Americas are at risk for infection. Although six plasmodium species cause malaria, P. falciparum accounted for approximately 97% of malaria cases worldwide in 2023 and is highly endemic in sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 1A). The WHO African region continues to have the highest burden of malaria, with an estimated 94% of the cases of malaria and 95% of the deaths from malaria worldwide during 2023.1 In 2023, P. vivax accounted for approximately 3.5% of the cases of malaria worldwide and was prevalent in South America, South and Southeast Asia, the Western Pacific, and Oceania (Fig. 1B).1 P. vivax is also present in certain areas of Mexico and Central America and is increasingly reported in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa. P. knowlesi is restricted to regions in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia and Malaysia.6 P. malariae and both P. ovale species (P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri) are less prevalent than the other plasmodium species but are widely distributed.7,8

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Malaria Cases in 2022.

Shown in Panel A is the predicted age-standardized prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) malaria per 5-km2 area (corresponding to one pixel) during 2022 among children 2 to 10 years of age. Gray shading indicates areas in which P. falciparum has not been endemic since at least 2000. Lighter gray shading indicates areas with a predicted prevalence of more than 0% and a population density of 5 people or less per 5 km2; these areas are present only in South America. Unshaded areas are those in which there were no cases of P. falciparum malaria during 2022 according to the model output or where P. falciparum has become nonendemic since 2000. Panel B shows the predicted prevalence of P. vivax (Pv) malaria per 5-km2 area (corresponding to one pixel) during 2022 among persons between 1 and 99 years of age. With the exception of several countries in East Africa, the burden of P. vivax malaria in Africa remains poorly measured. Areas in Africa where P. vivax transmission may be possible but there was not sufficient information to generate a prediction are mapped as having a very low prevalence. Gray shading indicates areas in which P. vivax has not been endemic since at least 2000. Darker gray shading indicates areas in which the predicted prevalence was very low. Unshaded areas are those in which there were no cases of P. vivax malaria during 2022 according to the model output or where P. vivax has become nonendemic since 2000. Data were generated with the use of methods and mapping outputs from the Malaria Atlas Project.5

A mean of 2000 cases of primarily P. falciparum malaria occur annually among travelers returning to the United States from regions where the disease is endemic.9 The majority of the cases are associated with a lack of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis in persons who visited friends and relatives in Africa.9 One study showed that the number of imported cases in three jurisdictions along the U.S. southern border increased from 28 cases in 2022 to 68 cases in 2023.10 In 2023, locally acquired mosquito-transmitted malaria occurred in four U.S. states in residents who had not traveled to regions where malaria is endemic.2,11 A rapid public health response that included active case detection, enhanced targeted mosquito surveillance, and control measures limited ongoing transmission.12

BIOLOGY OF PLASMODIUM

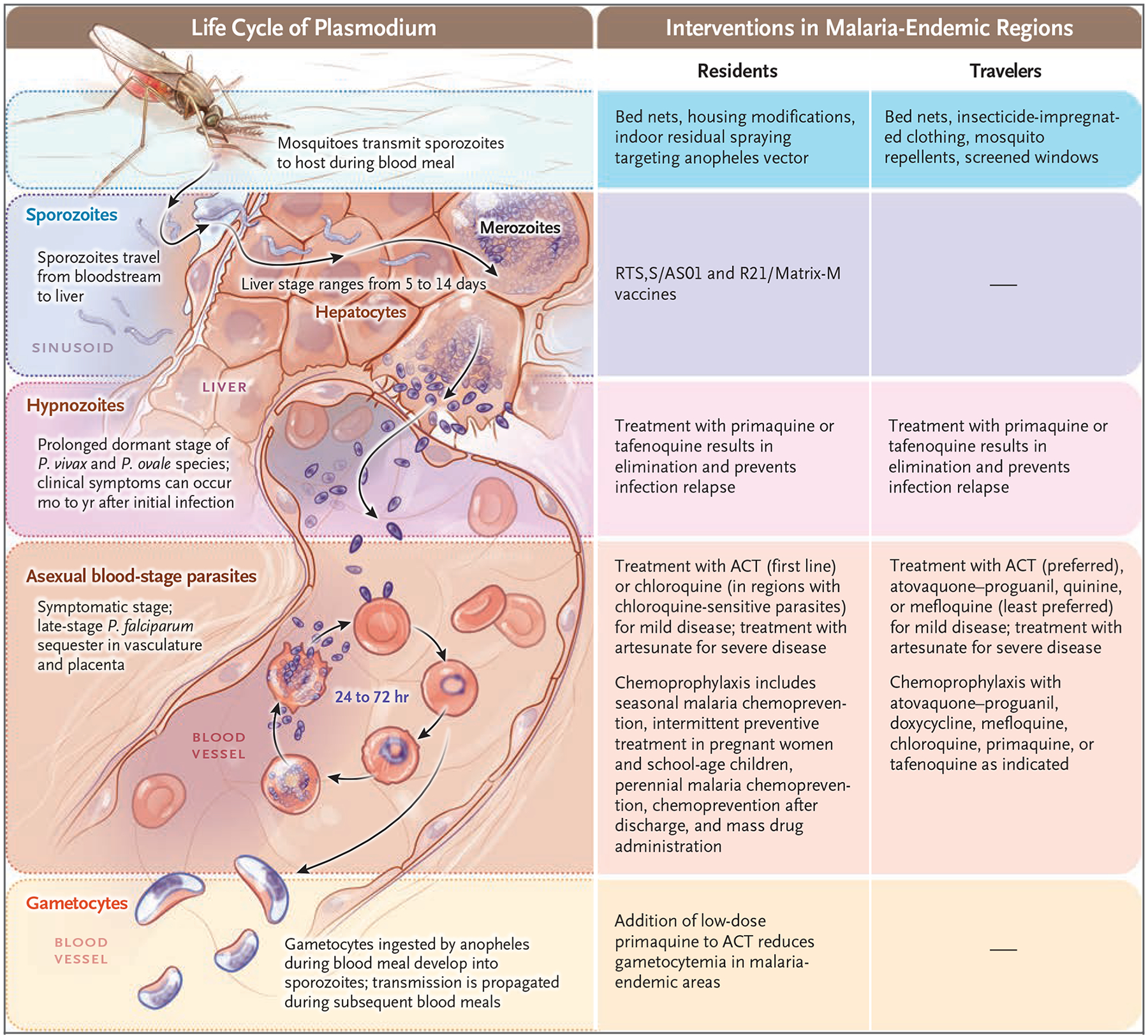

During a bite by a plasmodium-infected anopheles mosquito, invasive sporozoites, which have a tropism for the liver, are inoculated and infect hepatocytes (Fig. 2).13 During this clinically silent, preerythrocytic liver stage, the parasite undergoes massive replication to generate merozoites, which enter the bloodstream and invade erythrocytes. These intraerythrocytic asexual-stage parasites can cause the classic clinical manifestations of malaria. A small percentage of intraerythrocytic parasites become gametocytes, which do not cause symptoms. Gametocytes that are ingested by an anopheles mosquito during a blood meal develop into sporozoites, and transmission is propagated by the mosquito during subsequent blood meals.14 Plasmodium parasites can also be spread through blood donations, shared contaminated needles and syringes, bone marrow and organ transplantation, and in rare cases, congenitally or during childbirth.15–18

Figure 2. Plasmodium Life Cycle and Interventions.

Shown are major stages of the Plasmodium life cycle and an overview of interventions at each stage for residents of and travelers to regions where malaria is endemic. Housing modifications include putting screens on windows and doors and draining standing water. Monoclonal antibodies that target sporozoites and prevent infection of liver cells are in development. Perennial malaria chemoprevention was previously known as intermittent preventive treatment in infants. ACT denotes artemisinin-based combination therapy.

P. vivax and P. ovale species have a prolonged dormant liver stage (the hypnozoite stage), and clinical symptoms may not occur until months or years after the initial infection.19,20 Despite the absence of a hypnozoite stage, P. malariae can cause symptoms months to years after exposure.21 P. knowlesi is the primary agent of zoonotic malaria in humans, and locally acquired infections are limited to areas where humans live near the reservoir host (e.g., long-tailed and pig-tailed macaques).22,23 Other zoonotic plasmodium species with simian host reservoirs, such as P. brasilianum, P. simium, and P. cynomolgi, can occasionally infect humans and cause malaria.24,25

DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS

Plasmodium infection can lead to asymptomatic parasitemia or result in mild clinical symptoms (uncomplicated malaria) or severe disease. Patients with malaria typically present with chills and fever, which may be accompanied by headache; altered mentation; abdominal pain, diarrhea, or both; and other nonspecific symptoms. Abnormal results of laboratory tests include leukocytosis or leukopenia, elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, and an elevated creatinine level; anemia and thrombocytopenia are also common and help differentiate malaria from other infectious diseases.26 In high-transmission areas, repeated bouts of malaria within months after treatment are common in children.27 Although clinical immunity increases with repeated exposure to plasmodium organisms, sterilizing immunity does not occur.28

SEVERE MALARIA

Severe P. falciparum malaria is defined by the presence of one or more of the clinical and laboratory features shown in Table 1; similar criteria are used to define severe malaria due to other plasmodium parasites. Children and pregnant women living in regions where malaria is endemic and nonimmune travelers to such areas are at greater risk for severe illness and death.1 The clinical presentation of severe malaria differs according to age, with pulmonary edema being more common among adults and seizures and severe anemia being more common among children.32 P. falciparum infection causes the majority of severe cases; the virulence of this parasite is due to its capacity to generate high parasitemia and sequester in the microvasculature, resulting in impaired organ function and severe anemia. Acute kidney injury during severe malaria is common, is associated with higher mortality than severe cases without acute kidney injury, and may be underrecognized in children.31,33,34 P. knowlesi infection is also associated with severe disease, with high parasitemia and mortality.22,35,36 P. ovale species and P. malariae rarely cause severe disease, whereas P. vivax may occasionally be associated with severe disease and has been found to accumulate in the bone marrow and spleen.37–40

Table 1.

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Severe Plasmodium falciparum Malaria.*

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Impaired consciousness | A Glasgow coma score of <11 (range, 3 to 15; lower scores indicate lower levels of consciousness) in adults or a Blantyre coma score of <3 (range, 0 to 5; lower scores indicate lower levels of consciousness) in children |

| Multiple convulsions | More than two seizures within a 24-hr period |

| Prostration | Inability to sit, stand, or walk without assistance |

| Clinically significant bleeding | Recurrent or prolonged bleeding from the nose, gums, or venipuncture sites; hematemesis; or melena |

| Shock or circulatory collapse | A systolic blood pressure of <80 mm Hg (<70 mm Hg in children), plus evidence of impaired perfusion (cool extremities or prolonged capillary refill) |

| Laboratory and radiologic findings | |

| Acidosis | A base deficit of >8 meq/liter, a plasma bicarbonate level of <15 mmol/liter, or a venous plasma lactate level of ≥5 mmol/liter |

| Anemia | A hemoglobin level of <7 g/dl or a hematocrit of <20% (≤5 g/dl or ≤15%, respectively, in children <12 yr of age) plus a parasite density of >10,000/μl |

| Hypoglycemia | A plasma or serum glucose level of <40 mg/dl (<2.2 mmol/liter) |

| Parasitemia† | >10% (≥5% in nonimmune travelers) |

| Jaundice | A plasma or serum bilirubin level of >50 μmol/liter (3 mg/dl) plus a parasite density of >100,000/μl |

| Renal impairment‡ | A plasma or serum creatinine level of >3 mg/dl or a blood urea level of >20 mmol/liter |

| Pulmonary edema | Confirmed edema on radiologic examination or an oxygen saturation of <92% while breathing ambient air with a respiratory rate of >30 breaths/min |

A diagnosis of severe P. falciparum malaria is based on the presence of one or more of the indicated criteria.29 Severe P. vivax malaria is defined according to the same criteria as for severe P. falciparum malaria but with no parasite density thresholds. Severe P. knowlesi malaria is defined according to the same criteria as for severe P. falciparum malaria but with a parasite density of more than 20,000 per microliter in patients with jaundice. Severe malaria due to P. ovale or P. malariae is rare and is defined according to the same criteria as for severe P. falciparum malaria but with no parasite density thresholds.

Differences in parasitemia thresholds according to malaria immunity status have been suggested.29,30

Acute kidney injury is underrecognized in children. Use of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria should be considered to assess the level of renal impairment.31

PREGNANCY AND MALARIA

Women living in regions where malaria is endemic are at risk for the infection during pregnancy. Malaria during pregnancy is associated with a high risk of severe maternal disease, maternal and fetal death, and poor pregnancy outcomes.41 During pregnancy, the adherence of P. falciparum parasites to placental chondroitin sulfate A induces placental inflammation and dysregulated placental angiogenesis, which may result in placental insufficiency, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.42 The risk of placental malaria can be reduced with the use of chemoprophylaxis, which is a standard practice in some regions where malaria is endemic.29

DIAGNOSIS

Patients with malaria often present with nonspecific symptoms, which leads to a delay in diagnosis and treatment that is associated with untoward consequences.43 Thus, a high suspicion for malaria must be maintained in patients who present with current or recent fever and a history of travel to a region in which malaria is endemic. Malaria can also occur without exposure to a region where the disease is endemic; for example, locally acquired cases have been reported in the United States. According to an advisory issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a diagnosis of malaria in the United States should be considered in any person with fever of unknown origin, regardless of international travel history, particularly if the person has been to areas with recent cases of locally acquired malaria.12

LABORATORY-BASED DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

If malaria is suspected, a laboratory-based assessment for the presence of plasmodium infection is needed without delay. Diagnostic tests are used to identify the infecting species, assess parasitemia as a marker of disease severity, and monitor the response to antimalarial therapy. Microscopy of Giemsa-stained thick and thin peripheral-blood smears is the standard method of diagnosis and facilitates the identification of plasmodium species and quantification of parasitemia. Counts of only asexual-stage parasites that cause disease (i.e., not gametocytes) should be obtained as an indicator of the total parasitemia. The accurate identification of plasmodium species with the use of microscopy requires a high level of training, and in some cases it is not possible to distinguish species on the basis of morphologic characteristics.44

In contrast to microscopy, rapid diagnostic testing requires minimal training. Rapid diagnostic tests are used to assess blood samples for the presence of plasmodium proteins, most commonly P. falciparum–specific histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2). Rapid diagnostic tests have a sensitivity similar to that of microscopy for the detection of P. falciparum but a lower sensitivity for the detection of other plasmodium species.45

After a malaria diagnosis has been made on the basis of microscopy or rapid diagnostic testing, parasite species can be confirmed by means of polymerase-chain-reaction assay, which has limited availability in underresourced areas but is often available in highly resourced health care systems. Nucleic acid–based tests are not used in the diagnosis of clinical disease. However, they are highly sensitive for the detection of parasites in patients with low parasitemia, which can inform malaria control and elimination programs.46 Serologic tests for the detection of plasmodium antigens cannot be used to distinguish active infection from past infection. Thus, serologic tests have no role in the diagnosis of acute infection, but they may play a role in epidemiologic studies.

CHALLENGE — ACCURACY AND SENSITIVITY OF RAPID DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

A reduction in the sensitivity of rapid diagnostic tests due to genetic deletions in P. falciparum has emerged as a major concern, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately 80% of the rapid diagnostic tests used in Africa exclusively target the HRP2 antigen, yet P. falciparum parasites with deletions in genes encoding HRP2 have emerged, which can result in false negative tests.1,47,48 Other limitations of rapid diagnostic tests include persistent positivity after treatment, which precludes the use of this diagnostic tool in monitoring the therapeutic response; inability to quantify the parasite burden; challenges with the identification of species in infections due to plasmodium parasites other than P. falciparum and those due to more than one plasmodium species; and low reliability for the detection of P. knowlesi infection.49

TREATMENT

Most approaches to the treatment of malaria include combination therapy because of the risk of drug resistance. Drug resistance should be suspected if there is a delay in parasite clearance from the blood after the initiation of treatment.29

MILD MALARIA

Most P. falciparum infections are resistant to chloroquine and should be treated with artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). Artemisinin derivatives (artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin) are highly potent and have very short half-lives. ACTs include one artemisinin derivative plus a second, longer-acting antimalarial agent (such as lumefantrine, amodiaquine, piperaquine, mefloquine, or pyronaridine), often in coformulations.29 Artemether–lumefantrine is the most widely used antimalarial combination therapy worldwide. Alternative therapies for chloroquine-resistant plasmodium infection include other ACTs, atovaquone–proguanil, quinine, and mefloquine; mefloquine is used as a second-line therapy because of its associated gastrointestinal and neuropsychiatric side effects (Table 2). The use of chloroquine is restricted to only a few regions where P. falciparum is still sensitive to chloroquine, such as the Middle East and parts of Central America and the Caribbean.

Table 2.

Malaria Treatment and Relapse Prevention.*

| Indication and Drug | Dose | Frequency | Adverse Reactions† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment of mild malaria | |||||||

| Chloroquine resistance or unknown resistance | |||||||

| Artemether-lumefantrine‡ | Adults: four tablets (20 mg artemether and 120 mg lumefantrine per tablet) Children 5 to <15 kg: one tablet Children 15 to <25 kg: two tablets Children 25 to <35 kg: three tablets Children ≥35 kg: four tablets |

Adults and children: One dose at baseline and 8 hr on day 1 and one dose twice per day on days 2 and 3 | Headache (56%) Anorexia (40%) Dizziness (39%) Asthenia (38%) |

||||

| Atovaquone-proguanil§ | Adults: four adult tablets (250 mg atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil per tablet) Children 5 to <8 kg: two pediatric tablets (62.5 mg atovaquone and 25 mg proguanil per tablet) Children 8 to <10 kg: three pediatric tablets Children 10 to <20 kg: one adult tablet Children 20 to <30 kg: two adult tablets Children 30 to <40 kg: three adults tablets Children ≥40 kg: four adult tablets |

Adults and children: one dose per day for 3 days | Abdominal pain (17%) Nausea or vomiting (12%) Headache (10%) |

||||

| Quinine plus doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin¶ | Quinine: adults, 542 mg base (650 mg salt); children, 8.3 mg base/kg (10 mg salt/kg) Doxycycline: adults, 100 mg; children, 22 mg/kg Tetracycline: adults, 250 mg; children, 25 mg/kg/day Clindamycin: adults and children, 20 mg/kg/day |

Quinine: adults and children, one dose orally three times per day for 3–7 days Doxycycline: adults and children, one dose orally twice per day for 7 days Tetracycline: adults, one dose orally four times per day for 7 days; children, one dose orally per day (divided into four equal doses) for 7 days Clindamycin: adults and children, one dose orally per day (divided into three equal doses) for 7 days |

Quinine: cinchonism (e.g., headache, vision disturbances, sweating) Doxycycline: esophageal ulcers (<1%), photosensitivity (>10%), diarrhea (5%) Tetracycline: photosensitivity, abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting Clindamycin: diarrhea |

||||

| Mefloquine‖ | Adults: 684 mg base (750 mg salt) Children: 13.7 mg base/kg (15 mg salt/kg) |

Adults: one dose of 684 mg base orally at baseline and one dose of 456 mg base (500 mg salt) at 6–12 h Children: one dose of 13.7 mg base/kg orally at baseline and one dose of 9.1 mg base/kg (10 mg salt/kg) at 6–12 hr |

Vomiting (3%) Neuropsychiatric effects Dizziness |

||||

| Chloroquine sensitivity | |||||||

| Chloroquine | Adults: 600 mg base (1000 mg salt) Children: 10 mg base/kg (16.7 mg salt/kg) |

Adults: one dose of 600 mg base orally at baseline and one dose of 300 mg base (500 mg salt) at 6, 24, and 48 hr Children: one dose of 10 mg base/kg orally at baseline and one dose of 5 mg base/kg (8.3 mg salt/kg) orally at 6, 24, and 48 hr |

Vision disturbances Nausea or vomiting Pruritus |

||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Adults: 620 mg base (800 mg salt) Children: 10 mg base/kg (12.9 mg salt/kg) |

Adults: one dose of 620 mg base orally at baseline and one dose of 310 mg base (400 mg salt) at 6, 24, and 48 hr Children: one dose of 10 mg base/kg orally at baseline and one dose of 5 mg base/kg (6.5 mg salt/kg) at 6, 24, and 48 hr |

QT prolongation Neuropsychiatric effects Abnormal results of liver-function tests |

||||

| Prevention of relapse due to P. vivax or P. ovale species ** | |||||||

| Primaquine†† | Adults: 30 mg base Children: 0.5 mg base/kg |

Adults and children: one dose orally once per day for 14 days | Hemolytic anemia in G6PD deficiency Nausea Vomiting |

||||

| Tafenoquine‡‡ | Patients ≥16 yr of age: 300 mg | Patients ≥16 yr of age: one dose orally | Hemolytic anemia in G6PD deficiency (<1%) Diarrhea (18%) Headache (15%) Reversible vortex keratopathy (21–93%) |

||||

| Treatment of severe malaria | |||||||

| Artesunate§§ | Patients <20 kg: 3 mg/kg Patients ≥20 kg: 2.4 mg/kg |

All patients: one dose intravenously at baseline and 12 and 24 hr (minimum of three doses)¶¶ | Acute renal failure (8.9%) Jaundice (2.3%) Hemoglobinuria (6.7%) |

||||

Information in the table is adapted from a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.50 G6PD denotes glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Shown are adverse reactions included in the product label approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For select drugs, the percentage of patients with adverse reactions has not been defined by the FDA.

Artemether–lumefantrine should be administered with food in order to increase absorption and may be used during all trimesters of pregnancy. Other artemisinin-based combination therapies recommended by the World Health Organization include artesunate–amodiaquine, artesunate–mefloquine, dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, artesunate plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, and artesunate–pyronaridine.

Atovaquone–proguanil therapy is contraindicated in pregnant women, infants weighing less than 5 kg, and women who are breast-feeding infants weighing less than 5 kg unless no other treatment options are available.

The use of doxycycline or tetracycline is preferred over clindamycin treatment because of greater efficacy. Treatment with clindamycin is preferred for pregnant women and children younger than 8 years of age; treatment with doxycycline or tetracycline is not recommended in these populations unless no other options exist and the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks.

The use of mefloquine is not recommended if other options are available or in patients with a history of neuropsychiatric conditions. Mefloquine treatment is not recommended for plasmodium infections acquired in Southeast Asia owing to drug resistance.

Treatment with primaquine or tafenoquine is contraindicated during pregnancy; either drug can be given after delivery and during lactation if the mother and neonate have a normal G6PD level and no contraindications. To prevent relapse during pregnancy, chloroquine should be administered at a dose of 300 mg base (500 mg salt) weekly until delivery.

The indicated doses and frequency of primaquine therapy are for patients with a normal G6PD level (≥70% G6PD activity). The World Health Organization recommends a total dose of 7 mg per kilogram (given as 0.5 mg per kilogram per day for 14 days or 1 mg per kilogram per day for 7 days) for the prevention of relapse in patients with uncomplicated P. vivax or P. ovale malaria. For patients with an intermediate G6PD level (30–70%), treatment at a dose of 45 mg base orally once weekly for 8 weeks may be considered with close monitoring for hemolysis; as an alternative, chloroquine chemoprophylaxis (at a dose of 300 mg base orally once weekly) can be administered for 1 year after acute disease.

Tafenoquine (brand name, Krintafel) can be used only in patients who received chloroquine for treatment during the acute phase of disease and in patients who are at least 16 years of age. A normal result of a G6PD quantitative test is needed before the administration of treatment.

A full oral antimalarial regimen should be completed after initial therapy. If intravenous artesunate is not readily available, oral or parenteral treatment should be administered until intravenous artesunate is available. Patients should be monitored for delayed hemolysis for 4 weeks after the initiation of intravenous artesunate treatment.50

Parasitemia should be assessed 4 hours after the third dose. If the patient is receiving oral therapy and parasitemia is ≤1%, a full course of oral therapy should be completed. If the patient is unable to take oral medication or if parasitemia is >1%, intravenous artesunate should be continued daily for up to 6 more days, followed by completion of a full course of oral therapy.

In contrast to P. falciparum, P. vivax is generally sensitive to chloroquine and can be treated with chloroquine or ACT.29 Chloroquine-resistant P. vivax parasites are present in a few geographic locations, such as Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, and in rare cases have been reported in other regions where ACT is now first-line therapy.51 P. ovale species, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi can be treated with ACT or chloroquine.29 In areas where chloroquine resistance in any plasmodium species is present, ACT should be used if the species cannot be determined with certainty.

SEVERE MALARIA

Regardless of the infecting plasmodium species, the administration of parenteral artesunate is urgently indicated for patients with severe malaria, including those who are pregnant or lactating.29,52 At least three doses of intravenous artesunate are administered initially. When the asexual-stage parasitemia is 1% or less and oral antimalarial treatment does not result in unacceptable side effects, a full course of oral treatment is subsequently administered, in accordance with guidance for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria.53 If intravenous access is delayed, oral antimalarial agents should be administered during the interim period. In regions where malaria is endemic, patients can be treated with intramuscular artesunate, rectal artesunate, intramuscular artemether, or intramuscular quinine, with expedited follow-up care at a referral center for the administration of intravenous artesunate.

Patients with severe malaria need intensive care. Close evaluation of fluid status and the need for blood transfusions, empirical antibiotic therapy, or both should be conducted.29,54–56 Unconscious patients with malaria should undergo a lumbar puncture to rule out meningitis; this procedure has been shown to be safe in patients with cerebral malaria.57 Brain swelling associated with cerebral malaria is linked with high mortality; adjunctive therapy for this complication is under investigation.58 The administration of acetaminophen as a renal protective agent is safe in patients with severe disease, and early evidence suggests that acetaminophen may be associated with improved renal function.59 Adjunctive therapies such as exchange transfusion have not been shown to provide benefit to patients with severe malaria.60

Delayed hemolysis is an uncommon complication that can occur after the administration of intravenous artesunate, particularly in patients with high parasitemia.61,62 Weekly laboratory monitoring of hemoglobin and hemolytic markers for 4 weeks after the administration of intravenous artesunate is recommended.53 In rare cases, delayed hemolysis has been associated with the use of oral ACT.63

CHALLENGE — ARTEMISININ RESISTANCE

In addition to the long-standing presence of chloroquine resistance among malaria parasites, artemisinin resistance has emerged as another threat to successful antimalarial treatment. Partial resistance to artemisinin manifests as a delay in P. falciparum clearance from the blood after treatment with a drug containing an artemisinin derivative. This phenomenon was first observed nearly 20 years ago in Southeast Asia and is now present in multiple countries in East Africa, including Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.64,65 Partial resistance to artemisinin in P. falciparum is associated principally with mutations in the propeller domains of the parasite gene kelch13.66–68 Reduced susceptibility to partner drugs can also decrease the efficacy of ACT against malaria parasites.69,70

The WHO recommends the use of multiple first-line therapies as part of the response to drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa.71 Other approaches include the use of triple ACTs (artemisinin plus two partner drugs), continued development of non–artemisinin-based combination therapies, and improvement of current ACT regimens.72–74 If parasite clearance is delayed or there is concern about resistance to ACT because of recent travel to a malaria-endemic area where plasmodium parasites with partial resistance to artemisinin are present, the use of antimalarial drugs other than ACT agents should be considered if available. The WHO recommends the use of parenteral artesunate and parenteral quinine in patients with severe malaria in areas with established artemisinin resistance.29

CHALLENGE — PREVENTION OF RELAPSE

Patients with malaria due to P. vivax or P. ovale species are at risk for relapse of infection because hypnozoite-stage parasites are not killed by standard antimalarial agents. Treatment with an 8-aminoquinoline (primaquine or tafenoquine) is needed to eliminate hypnozoites and prevent a relapse (Table 2). Among primaquine doses, a total dose of 7 mg per kilogram of body weight is associated with the highest efficacy in preventing relapse.75 Primaquine is administered at a dose of 30 mg base per day for 14 days.30 According to the WHO, a 7-day course of primaquine at a higher daily dose of 1.0 mg per kilogram per day is efficacious and may improve adherence to treatment but should be given only to patients with at least 70% glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity. Higher total doses of primaquine, whether given over 7 or 14 days, are more beneficial in areas with a high risk of relapse.29 A single dose of tafenoquine prevents relapse after treatment of malaria with chloroquine and is noninferior to primaquine.76,77 However, tafenoquine is less efficacious if ACT is used initially to treat malaria; in this scenario, primaquine should be used to prevent relapse.78

Both primaquine and tafenoquine can cause hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency, so a quantitative G6PD test must be performed before either agent is administered. Tafenoquine therapy is contraindicated in patients with mild-to-moderate G6PD deficiency; a lower dose of primaquine (0.75 mg per kilogram given once weekly for 8 weeks) and close monitoring for hemolysis is recommended in such patients.29 The administration of 8-aminoquinolines to prevent relapse is an underused approach in some regions where malaria is endemic owing to the lack of a widely available and reliable point-of-care G6PD test.

PREVENTION AND CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS IN TRAVELERS

Malaria is a common illness among international travelers who visit regions where the disease is endemic, with more than 30,000 cases worldwide reported annually to the GeoSentinel network.79 A detailed travel itinerary, current medications, pregnancy status, and allergy history should be reviewed with travelers to regions in which malaria is endemic. Travelers should be counseled to avoid mosquito bites through use of bed nets, protective clothing, vector-control devices, and mosquito repellents such as DEET (N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide), picaridin, and IR3535 (ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate).

The selection of an antimalarial chemoprophylaxis regimen for persons traveling to regions where malaria is endemic is based on the seasonality and intensity of transmission, plasmodium species, drug-sensitivity pattern, antimalarial side-effect profile, and patient preference regarding the frequency of dosing. Each antimalarial chemoprophylaxis regimen has specific dosing schedules, contraindications, and adverse-event profiles (Table 3). Chemoprophylaxis is initiated before travel and continued for 1 to 4 weeks upon return. Antimalarial agents for the prevention of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum infection include atovaquone–proguanil, doxycycline, and mefloquine. The 8-aminoquinolines primaquine and tafenoquine can be used for chemoprophylaxis in patients with normal G6PD activity. These agents are also ideal for malaria prevention in regions where P. vivax is endemic because they prevent infection due to blood-stage parasites and kill hypnozoites. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine can be used as chemoprophylaxis in regions with chloroquine-sensitive plasmodium parasites. If the plasmodium antimalarial resistance profile is uncertain, chemoprophylaxis that is indicated for chloroquine-resistant parasites should be used. Drug costs and availability should be addressed before departure to improve adherence and lower the risk of imported malaria on return.81

Table 3.

Chemoprophylaxis Regimens for Travelers to Malaria-Endemic Regions.*

| Drug | Dose | Frequency of Administration | Adverse Events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Travel | During Travel | After Travel | |||

| Atovaquone–proguanil | 250 mg atovaquone, 100 mg proguanil | Once daily for 1–2 days | Once daily | Once daily for 7 days | Nausea or vomiting (12%) |

| Doxycycline | 100 mg | Once daily for 1–2 days | Once daily | Once daily for 30 days | Esophageal ulcers (<1%), photosensitivity (>10%) |

| Primaquine† | 30 mg base | Once daily for 1–2 days | Once daily | Once daily for 7 days | G6PD deficiency-associated anemia |

| Chloroquine‡ | 300 mg base | Once weekly for 1–2 wk | Once weekly | Once weekly for 4 wk | Nausea or vomiting |

| Mefloquine‡§ | 228 mg base | Once weekly for 1–2 wk | Once weekly | Once weekly for 4 wk | Neuropsychiatric conditions (14%) |

| Tafenoquine¶ | 200 mg | Once daily for 3 days | Once weekly | Once during wk after return | G6PD deficiency–associated anemia |

Information in the table is adapted from the report by Chen et al.80

Primaquine can be used for prevention in regions where more than 90% of malaria cases are attributable to P. vivax. Primaquine may also be used as presumptive antirelapse therapy to clear hypnozoites in travelers returning from areas where P. vivax or P. ovale species are endemic.

Chloroquine and mefloquine may be used as chemoprophylaxis during all trimesters of pregnancy.

Patients who receive a prescription for mefloquine should be counseled to discontinue the drug and use an alternative medication if psychiatric or neurologic symptoms occur. An FDA black-box warning exists for mefloquine owing to rare reports of persistent dizziness after the use of the drug.

Tafenoquine (brand name, Arakoda) is approved by the FDA for use as malaria chemoprophylaxis. Once weekly administration should begin 7 days after the last loading dose.

PREVENTIVE MEASURES IN MALARIA-ENDEMIC REGIONS

On the basis of recent trends, the 2030 targets of the WHO global technical strategy for reducing global malaria mortality and morbidity will not be achieved.3 In response, new strategies that address the root causes of malaria, such as poverty, climate change, and drug and insecticide resistance, have been developed. The hope is that a broad-based platform supported by close working relationships with all interested stake-holders will facilitate the achievement of newly established goals to reduce transmission and disease.3

VECTOR CONTROL

Insecticide-treated bed nets are used for the prevention and control of malaria in children and adults living in areas with malaria transmission. Indoor residual spraying of WHO-prequalified insecticides can be an effective intervention when the chemicals in the spray are tailored to local vector-susceptibility patterns and the use of spraying is sustained. Additional investigational approaches to vector control include the introduction of genetically modified mosquitoes and the use of endectocides and toxic-sugar baits that attract mosquitoes.

CHALLENGE — VECTOR ADAPTATIONS TO INSECTICIDES

Resistance to insecticides, particularly pyrethroid-based agents in insecticide-treated bed nets, is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, with resistance to pyrethroids, organochlorines, carbamates, and organophosphates present at multiple sites.1 The use of bed nets that are treated with multiple chemical classes of insecticides is now recommended, and these bed nets are being deployed in areas with known resistance to insecticides.29 Other challenges include a lack of effective outdoor strategies to target biting mosquitoes and problematic changes in mosquito behavior, which include shifts in biting times that reduce the efficacy of indoor residual spraying and insecticide-treated bed nets.82 A recent systematic review suggests that 20% of the mosquito bites in Africa occur when persons are not lying in bed.83 In addition, the geographic distribution of anopheles mosquitoes that are highly adept at transmitting both P. falciparum and P. vivax (i.e., Anopheles stephensi) has increased.84–86

CHALLENGE — HUMAN AND ZOONOTIC RESERVOIRS

One of the biggest challenges to malaria control and elimination programs is asymptomatic infection, which represents the bulk of infections worldwide and serves as a major reservoir for ongoing transmission.27,87,88 In special circumstances, the use of mass drug administration to eliminate the reservoir of infection in humans can be considered in regions in which malaria is endemic; however, the reduction in malaria transmission is often not sustained after mass drug administration is discontinued.29,89 P. knowlesi has a simian reservoir, which presents unique challenges that will require new control interventions to achieve eradication.23

CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS

Prevention of infection in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and children younger than 5 years of age in areas where malaria is endemic is a cornerstone of malaria-control programs. School-age children have more recently been identified as a vulnerable population and may also benefit from chemoprophylaxis in certain settings.88,90 The administration of chemoprophylaxis is dependent on local transmission characteristics and national guidelines. Current programs recommended by the WHO include seasonal malaria chemoprevention, perennial malaria chemoprevention (previously known as intermittent preventive treatment in infants), intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women and school-age children, malaria chemoprevention after discharge from the hospital, and mass drug administration strategies to reduce the burden of disease, transmission, or both.29

Strategies to interrupt transmission in low transmission settings include killing gametocytes with the administration of primaquine at a single low dose (0.25 mg per kilogram) with an ACT for nonpregnant adults and children who are 1 month of age or older with P. falciparum malaria.29,91 To decrease transmission, single-dose primaquine therapy is also recommended in areas with malaria parasites that have partial resistance to artemisinin.29

PROGRESS — MALARIA VACCINES AND MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES

In 2024, malaria vaccinations were introduced into routine child immunization schedules in a handful of African countries.92 Malaria vaccines approved by the WHO for use in children residing in regions with moderate-to-high transmission include RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M. These recombinant circumsporozoite protein–based subunit vaccines target preerythrocytic-stage parasites (sporozoites) in order to prevent infection with blood-stage parasites and provide partial protection against severe disease.93,94 Vaccines targeting malaria parasites in other stages of the life cycle are under development.

Monoclonal antibodies that target the circumsporozoite protein are being developed to prevent P. falciparum malaria in regions where infection due to this species is endemic.95 Monoclonal antibodies can rapidly provide a reliable level of protective antibodies, and subcutaneous administration would facilitate broader use of this approach.

Combining preventive measures such as vaccination with seasonal chemoprevention has been shown to increase protective efficacy.96 The best strategies for reducing the transmission and burden of malaria in a given region are those that are tailored to the local ecology and transmission dynamics, drug-resistance profiles in plasmodium parasites, and insecticide-resistance patterns in anopheles mosquitoes. These strategies must be driven by input from scientists in countries where malaria is endemic and the populations at risk to ensure their feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

Exciting progress has been made in the fight against malaria, with the development of vaccines and an increase in the number of countries that are now free of malaria. Yet malaria remains a formidable global health challenge.84 Continued investment in malaria-control programs, health care access, and research to discover new interventions may allow a future in which malaria no longer poses a threat to human health.

KEY POINTS.

MALARIA

Malaria remains a major threat to human health worldwide.

Malaria necessitates a prompt laboratory-based diagnosis and expedited treatment.

Microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests are the most widely used tools for the diagnosis of malaria. The accuracy of rapid diagnostic tests has decreased because of mutations in the gene encoding the target plasmodium protein.

Vaccines to prevent malaria have been approved for use in children in regions of endemicity.

Artemisinin-based combination therapy is the standard treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. However, partial resistance to artemisinin has emerged in Africa.

Challenges to vector control include insecticide resistance, changes in feeding behavior, and geographic expansion of vector species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Barbara H. McGovern for critical review of an earlier version of the manuscript and Jennifer Rozier (Malaria Atlas Project) for assistance with an earlier version of Figure 1.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.World malaria report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization, December 11, 2024 (https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn D, Drennon M, Broussard K, et al. Outbreak of locally acquired mosquito-transmitted (autochthonous) malaria — Florida and Texas, May–July 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72: 973–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Malaria Programme operational strategy 2024–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2024. (https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376518/9789240090149-eng.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villena OC, Arab A, Lippi CA, Ryan SJ, Johnson LR. Influence of environmental, geographic, socio-demographic, and epidemiological factors on presence of malaria at the community level in two continents. Sci Rep 2024;14:16734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss AM, Dzianach PA, Saddler A, et al. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria, 2000–22: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet 2025:S0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobin RJ, Harrison LE, Tully MK, et al. Updating estimates of Plasmodium knowlesi malaria risk in response to changing land use patterns across Southeast Asia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024;18(1):e0011570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawadak J, Dongang Nana RR, Singh V. Global trend of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale spp. malaria infections in the last two decades (2000–2020): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors 2021;14:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahittikorn A, Masangkay FR, Kotepui KU, Milanez GJ, Kotepui M. Comparison of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri infections by a meta-analysis approach. Sci Rep 2021;11:6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mace KE, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Malaria surveillance — United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell CL, Kennar A, Vasquez Y, et al. Notes from the field: increases in imported malaria cases — three southern U.S. border jurisdictions, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:417–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duwell M, DeVita T, Torpey D, et al. Notes from the field: locally acquired mosquito-transmitted (autochthonous) Plasmodium falciparum malaria — National Capital Region, Maryland, August 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1123–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locally acquired malaria cases identified in the United States. June 26, 2023 (https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00494.asp#print).

- 13.Vaughan AM, Kappe SHI. Malaria parasite liver infection and exoerythrocytic biology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017;7(6):a025486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joice R, Nilsson SK, Montgomery J, et al. Plasmodium falciparum transmission stages accumulate in the human bone marrow. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:244re5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosso F, Agudelo Rojas OL, Suarez Gil CC, et al. Transmission of malaria from donors to solid organ transplant recipients: a case report and literature review. Transpl Infect Dis 2021;23(4):e13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stubbs LA, Price M, Noland D, et al. Transfusion-transmitted malaria: two pediatric cases from the United States and their relevance in an increasingly globalized world. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2021;10:1092–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmadpour E, Foroutan-Rad M, Majidiani H, et al. Transfusion-transmitted malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danwang C, Bigna JJ, Nzalie RNT, Robert A. Epidemiology of clinical congenital and neonatal malaria in endemic settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J 2020;19:312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Commons RJ, Simpson JA, Watson J, White NJ, Price RN. Estimating the proportion of Plasmodium vivax recurrences caused by relapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020;103:1094–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stadler E, Cromer D, Mehra S, et al. Population heterogeneity in Plasmodium vivax relapse risk. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022;16(12):e0010990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Culleton R, Pain A, Snounou G. Plasmodium malariae: the persisting mysteries of a persistent parasite. Trends Parasitol 2023;39:113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajahram GS, Cooper DJ, William T, Grigg MJ, Anstey NM, Barber BE. Deaths from Plasmodium knowlesi malaria: case series and systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:1703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fornace KM, Zorello Laporta G, Vythilingham I, et al. Simian malaria: a narrative review on emergence, epidemiology and threat to global malaria elimination. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23(12):e520–e532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasil P, Zalis MG, de Pina-Costa A, et al. Outbreak of human malaria caused by Plasmodium simium in the Atlantic Forest in Rio de Janeiro: a molecular epidemiological investigation. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5(10):e1038–e1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imwong M, Madmanee W, Suwannasin K, et al. Asymptomatic natural human infections with the simian malaria parasites Plasmodium cynomolgi and Plasmodium knowlesi. J Infect Dis 2019;219:695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor SM, Molyneux ME, Simel DL, Meshnick SR, Juliano JJ. Does this patient have malaria? JAMA 2010;304:2048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin J, Kajubi R, Wang K, et al. Persistent and multiclonal malaria parasite dynamics despite extended artemether-lumefantrine treatment in children. Nat Commun 2024;15:3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Arinaitwe E, Jagannathan P, et al. Quantification of anti-parasite and anti-disease immunity to malaria as a function of age and exposure. Elife 2018;7:e35832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO guidelines for malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization, November 30, 2024 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of malaria: guidelines for clinicians (United States) (https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/clinicians1.html#severe).

- 31.Batte A, Berrens Z, Murphy K, et al. Malaria-associated acute kidney injury in African children: prevalence, pathophysiology, impact, and management challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2021;14:235–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dondorp AM, Lee SJ, Faiz MA, et al. The relationship between age and the manifestations of and mortality associated with severe malaria. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsoulis O, Georgiadou A, Cunning-ton AJ. Immunopathology of acute kidney injury in severe malaria. Front Immunol 2021;12:651739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawkes MT, Leligdowicz A, Batte A, et al. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury in malaria and non-malarial febrile illness: a prospective cohort study. Pathogens 2022;11:436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu TH, Rosli N, Mohamad DSA, et al. A comparison of the clinical, laboratory and epidemiological features of two divergent subpopulations of Plasmodium knowlesi. Sci Rep 2021;11:20117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo CK-F, Plewes K, Sharma S, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi infection in traveler returning to Canada from the Philippines, 2023. Emerg Infect Dis 2023;29:2177–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Severity and mortality of severe Plasmodium ovale infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15(6):e0235014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Global prevalence and mortality of severe Plasmodium malariae infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J 2020;19:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva-Filho JL, Dos-Santos JC, Judice C, et al. Total parasite biomass but not peripheral parasitaemia is associated with endothelial and haematological perturbations in Plasmodium vivax patients. Elife 2021;10:e71351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kho S, Qotrunnada L, Leonardo L, et al. Evaluation of splenic accumulation and colocalization of immature reticulocytes and Plasmodium vivax in asymptomatic malaria: a prospective human splenectomy study. PLoS Med 2021;18(5):e1003632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gore-Langton GR, Cano J, Simpson H, et al. Global estimates of pregnancies at risk of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infection in 2020 and changes in risk patterns since 2000. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022;2(11):e0001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chua CLL, Khoo SKM, Ong JLE, Ramireddi GK, Yeo TW, Teo A. Malaria in pregnancy: from placental infection to its abnormal development and damage. Front Microbiol 2021;12:777343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman-Yassen AE, Mony VK, Arguin PM, Daily JP. Higher rates of misdiagnosis in pediatric patients versus adults hospitalized with imported malaria. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016;32:227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coutrier FN, Tirta YK, Cotter C, et al. Laboratory challenges of Plasmodium species identification in Aceh Province, Indonesia, a malaria elimination setting with newly discovered P. knowlesi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12(11):e0006924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kavanaugh MJ, Azzam SE, Rockabrand DM. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests: literary review and recommendation for a quality assurance, quality control algorithm. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girma S, Cheaveau J, Mohon AN, et al. Prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of asymptomatic malaria based on ultrasensitive diagnostics: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gendrot M, Fawaz R, Dormoi J, Madamet M, Pradines B. Genetic diversity and deletion of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 and 3: a threat to diagnosis of P. falciparum malaria. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019;25:580–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beshir KB, Parr JB, Cunningham J, Cheng Q, Rogier E. Screening strategies and laboratory assays to support Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein deletion surveillance: where we are and what is needed. Malar J 2022;21:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foster D, Cox-Singh J, Mohamad DS, Krishna S, Chin PP, Singh B. Evaluation of three rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of human infections with Plasmodium knowlesi. Malar J 2014;13:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Appendix A: malaria in the United States: treatment tables. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 14, 2024 (https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/hcp/clinical-guidance/malaria-treatment-tables.html). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferreira MU, Nobrega de Sousa T, Rangel GW, et al. Monitoring Plasmodium vivax resistance to antimalarials: persisting challenges and future directions. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2021;15:9–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1647–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of severe malaria. March 27, 2024 (https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/hcp/clinical-guidance/treatment-of-severe-malaria.html).

- 54.Kalkman LC, Hänscheid T, Krishna S, Grobusch MP. Fluid therapy for severe malaria. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22(6):e160–e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishioka H, Plewes K, Pattnaik R, et al. Associations between restrictive fluid management and renal function and tissue perfusion in adults with severe falciparum malaria: a prospective observational study. J Infect Dis 2020;221:285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ippolito MM, Kabuya J-BB, Hauser M, et al. Whole blood transfusion for severe malarial anemia in a high Plasmodium falciparum transmission setting. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:1893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moxon CA, Zhao L, Li C, et al. Safety of lumbar puncture in comatose children with clinical features of cerebral malaria. Neurology 2016;87:2355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seydel KB, Kampondeni SD, Valim C, et al. Brain swelling and death in children with cerebral malaria. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1126–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plewes K, Kingston HWF, Ghose A, et al. Acetaminophen as a renoprotective adjunctive treatment in patients with severe and moderately severe falciparum malaria: a randomized, controlled, open-label trial. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:991–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varo R, Crowley VM, Sitoe A, et al. Adjunctive therapy for severe malaria: a review and critical appraisal. Malar J 2018;17:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaita S, Madsalae K, Charoensakulchai S, et al. Post-artesunate delayed hemolysis: a review of current evidence. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023;8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abanyie F, Ng J, Tan KR. Post-artesunate delayed hemolysis in patients with severe malaria in the United States — April 2019 through July 2021. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76(3):e857–e863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurth F, Lingscheid T, Steiner F, et al. Hemolysis after oral artemisinin combination therapy for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:1381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Conrad MD, Asua V, Garg S, et al. Evolution of partial resistance to artemisinins in malaria parasites in Uganda. N Engl J Med 2023;389:722–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Straimer J, Gandhi P, Renner KC, Schmitt EK. High prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum K13 mutations in Rwanda is associated with slow parasite clearance after treatment with artemether-lumefantrine. J Infect Dis 2022;225:1411–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mbengue A, Bhattacharjee S, Pandharkar T, et al. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 2015;520:683–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mihreteab S, Platon L, Berhane A, et al. Increasing prevalence of artemisinin-resistant HRP2-negative malaria in Eritrea. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ward KE, Fidock DA, Bridgford JL. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Curr Opin Microbiol 2022;69:102193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, et al. Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:952–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ehrlich HY, Bei AK, Weinberger DM, Warren JL, Parikh S. Mapping partner drug resistance to guide antimalarial combination therapy policies in sub-Saharan Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118(29):e2100685118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.World Health Organization Global Malaria Programme. Multiple first-line therapies as part of the response to antimalarial drug resistance: an implementation guide. November 20, 2024 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240103603).

- 72.Whalen ME, Kajubi R, Goodwin J, et al. The impact of extended treatment with artemether-lumefantrine on antimalarial exposure and reinfection risks in Ugandan children with uncomplicated malaria: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76:443–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenthal PJ, Asua V, Bailey J, et al. The emergence of artemisinin partial resistance in Africa: how do we respond? Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:e591–e600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Pluijm RW, Tripura R, Hoglund RM, et al. Triple artemisinin-based combination therapies versus artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a multicentre, open-label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2020;395:1345–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Commons RJ, Rajasekhar M, Edler P, et al. Effect of primaquine dose on the risk of recurrence in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:172–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Llanos-Cuentas A, Lacerda MVG, Hien TT, et al. Tafenoquine versus primaquine to prevent relapse of Plasmodium vivax malaria. N Engl J Med 2019;380:229–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lacerda MVG, Llanos-Cuentas A, Krudsood S, et al. Single-dose tafenoquine to prevent relapse of Plasmodium vivax malaria. N Engl J Med 2019;380:215–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sutanto I, Soebandrio A, Ekawati LL, et al. Tafenoquine co-administered with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the radical cure of Plasmodium vivax malaria (INSPECTOR): a randomised, placebo-controlled, efficacy and safety study. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23:1153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Angelo KM, Libman M, Caumes E, et al. Malaria after international travel: a GeoSentinel analysis, 2003–2016. Malar J 2017;16:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen V, Daily JP. Tafenoquine: the new kid on the block. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2019;32:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walz EJ, Volkman HR, Adedimeji AA, et al. Barriers to malaria prevention in US-based travellers visiting friends and relatives abroad: a qualitative study of West African immigrant travellers. J Travel Med 2019;26:tay163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sangbakembi-Ngounou C, Costantini C, Longo-Pendy NM, et al. Diurnal biting of malaria mosquitoes in the Central African Republic indicates residual transmission may be “out of control.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(21):e2104282119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sherrard-Smith E, Skarp JE, Beale AD, et al. Mosquito feeding behavior and how it influences residual malaria transmission across Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:15086–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carlson CJ, Bannon E, Mendenhall E, Newfield T, Bansal S. Rapid range shifts in African Anopheles mosquitoes over the last century. Biol Lett 2023;19:20220365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou G, Zhong D, Yewhalaw D, Yan G. Anopheles stephensi ecology and control in Africa. Trends Parasitol 2024;40:102–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Eryani SM, Irish SR, Carter TE, et al. Public health impact of the spread of Anopheles stephensi in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region countries in Horn of Africa and Yemen: need for integrated vector surveillance and control. Malar J 2023;22:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heinemann M, Phillips RO, Vinnemeier CD, Rolling CC, Tannich E, Rolling T. High prevalence of asymptomatic malaria infections in adults, Ashanti Region, Ghana, 2018. Malar J 2020;19:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Markwalter CF, Lapp Z, Abel L, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection in humans and mosquitoes influence natural anopheline biting behavior and transmission. Nat Commun 2024;15:4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shah MP, Hwang J, Choi L, Lindblade KA, Kachur SP, Desai M. Mass drug administration for malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; 9: CD008846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cohee LM, Opondo C, Clarke SE, et al. Preventive malaria treatment among school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8(12):e1499–e1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tine RC, Sylla K, Faye BT, et al. Safety and efficacy of adding a single low dose of primaquine to the treatment of adult patients with plasmodium falciparum malaria in Senegal, to reduce gametocyte carriage: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:535–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Venkatesan P. Routine malaria vaccinations start in Africa. Lancet Microbe 2024;5(6):e519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Olotu A, Fegan G, Wambua J, et al. Four-year efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E and its interaction with malaria exposure. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Datoo MS, Dicko A, Tinto H, et al. Safety and efficacy of malaria vaccine candidate R21/Matrix-M in African children: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2024;403:533–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Preston AC, et al. Subcutaneous administration of a monoclonal antibody to prevent malaria. N Engl J Med 2024;390:1549–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dicko A, Ouedraogo J-B, Zongo I, et al. Seasonal vaccination with RTS,S/AS01E vaccine with or without seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children up to the age of 5 years in Burkina Faso and Mali: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]