Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the default response for all hospitalized patients who experience a cardiac or respiratory arrest in the United States, unless they have a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in their electronic health record (EHR). A standard DNR order must be requested or agreed on by the patient or their surrogate. Yet clinicians report significant moral distress when performing CPR on some patients, such as when it is unlikely to enhance the patient’s chance of survival.1 Whether it is permissible in these scenarios for clinicians to place a unilateral DNR (UDNR) order, a DNR order that does not require patient or surrogate consent, is a clinical medical ethics controversy that dates to the creation of closed chest CPR.2,3 In observational studies, UDNR orders were placed for 3% of hospitalized critically ill patients receiving vasoactive support and were associated with disproportionate use in vulnerable populations, and documentation of patient or surrogate notification about these orders did not always occur.2,3

Clinicians may make UDNR decisions for a variety of reasons, such as the belief that performing CPR is physiologically futile or “potentially inappropriate,” judging the harms of CPR to outweigh the benefits for the patient. Unilateral DNR decisions in “potentially inappropriate” situations are more controversial because clinician value judgments, rather than medical decision-making alone, may also be involved. In either case, it is broadly accepted that UDNR decisions should be transparently shared with patients or surrogates.

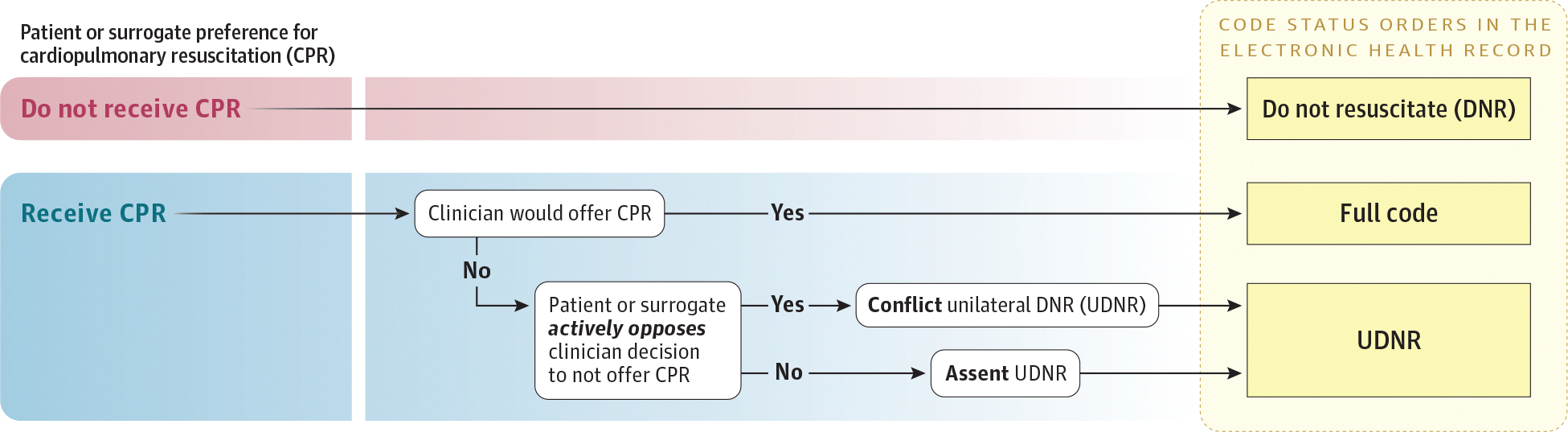

Clinicians often document UDNR decisions by placing a standard DNR order in the EHR, rendering them indistinguishable from DNR orders entered when a patient or surrogate requests to not receive CPR.2,3 We argue this practice is unethical because it obscures the unilateral decision-making by the clinician, ignoring the critical dimension of what the patient or surrogate would have chosen if offered CPR and their response to being informed that CPR would not be offered. We show how considering the patient or surrogate perspective leads to 2 distinct types of UDNR decisions in clinical practice: a more clinically apparent “conflict” UDNR decision and a more covert “assent” UDNR decision (Figure). We argue these UDNR types imply different ethical obligations for clinicians and should be documented transparently and distinctly from standard DNR orders in the EHR.

Figure. Code Status Orders in the Electronic Health Record.

Conflict vs Assent UDNR

A conflict UDNR decision occurs when a clinician makes a UDNR decision despite active opposition expressed by the patient or surrogate. To all parties involved, this scenario is obviously in line with unilateral decision-making because the patient or surrogate clearly disagrees with the clinician’s decision to withhold CPR. Conflict UDNR decisions are restricted in some US states and hospitals, where qualitative data suggest active opposition by the patient or surrogate to the UDNR decision compels clinicians to perform CPR in these scenarios.4

In contrast, assent UDNR decisions can covertly exist in any hospital. An assent UDNR decision occurs when a clinician makes a UDNR decision and the patient or surrogate disagrees with this decision but either does not express disagreement (eg, does not demand CPR) or has a preference to receive CPR but chooses to defer to clinician decision-making. In an assent UDNR decision, clinicians make declarative statements such as “We are not going to perform CPR” and accept the patient’s or surrogate’s lack of dissent as tacit agreement. However, if CPR were offered, the patient or surrogate would have requested CPR to be performed.

Although a patient or surrogate may acquiesce to an assent UDNR decision in the setting of serious illness, they may be less likely to agree to a standard DNR order if the patient’s condition were to improve. In the event of improvement, clinicians have an obligation to assess the patient’s underlying preference for CPR.

Ethical Importance of Documenting and Communicating UDNR Decisions

Current EHR documentation of UDNR decisions is inadequate and inconsistent. There is often limited or missing documentation about the unilateral nature of the clinician’s decision. In addition, documentation regularly lacks descriptions critical to distinguish among the distinct types of UDNR decisions, such as a patient’s or surrogate’s underlying preference for CPR and their response to the UDNR decision.2

Inadequate documentation of UDNR decisions contributes to inconsistencies in patient care. First, during patient hand-offs among clinicians, the new clinician may be unaware the patient or surrogate was previously informed CPR would not be performed due to perceived futility. They may instead believe a DNR decision reflected patient preference. This belief may lead to inconsistent communication about the UDNR decision among clinicians, eroding patient or surrogate trust in the medical team and contributing to conflict.

Second, lack of awareness that a DNR order was a unilateral clinician decision decreases the likelihood that clinicians will reevaluate the DNR order for patients whose clinical condition improves. Failure to reevaluate the DNR order may lead a patient to retain the order throughout their hospital admission, even if the reason the DNR order was unilaterally placed (ie, perceived futility) is no longer accurate and this standard DNR order does not align with the patient’s preferences for care. It is critical for DNR orders to be reevaluated in these situations to ensure patient autonomy is respected for patients who could medically benefit from CPR, prevent harm from withholding CPR, and reduce the risk that other essential care will be withheld.

Third, inadequate documentation of UDNR decisions limits the ability to retrospectively review UDNR order use. Retrospective review is critical to identify and address potentially inappropriate use of UDNR orders (ie, the patient has some chance of medical benefit from CPR), disparities in UDNR order use, and the frequency of conflict associated with these decisions.

Practical Implications for Clinical Practice and EHR Documentation

To overcome the problem of inadequate and inconsistent UDNR order documentation, hospital systems should create and implement a centralized UDNR order in the EHR that is unique from a DNR order. This UDNR order should include specifications within the order that require clinicians to regularly reevaluate this code status if the patient clinically improves and designate whether patient or surrogate disagreement exists with this order. Hospital policies should be updated with clear recommendations for UDNR order use, including the requirement that clinicians notify the patient or surrogate about UDNR decisions.5

Challenges may exist with the creation and implementation of UDNR orders, including adding to the complexity of code status orders that already lack uniformity across hospitals.6,7 Another challenge may be lack of staff awareness about the meaning of UDNR orders and how this differs from a DNR order. Therefore, for UDNR orders to be used, it is essential to train bedside staff about them to ensure they understand their meaning and what actions should be taken if a patient with a UDNR order experiences a cardiac arrest or the patient’s condition unexpectedly improves. Because UDNR orders will increase visibility of UDNR decisions, the possibility to normalize use of UDNR decisions and influence clinicians to more regularly invoke this mechanism exists. This potential challenge must be assessed in retrospective review of UDNR orders and action must be taken to minimize unilateral decision-making and promote shared decision-making among clinicians and patients or surrogates.

Although challenges to implementing UDNR orders may exist, there is evidence this order can be used in practice.2 Detailed UDNR orders are critical to increase transparency about how the DNR decision was made and improve clinician awareness to revisit this order for patients who clinically improve. All health systems in the United States should support the creation and implementation of UDNR orders within the EHR.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr DeMartino reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the work. Dr Parker reported grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01 LM014263) and the Greenwall Foundation during the conduct of the work; and grants from NIH (K08 HL150291) outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Contributor Information

Gina M. Piscitello, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Palliative Research Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Erin S. DeMartino, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; Biomedical Ethics Research Program, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

William F. Parker, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

REFERENCES

- 1.Piscitello GM, Kapania EM, Kanelidis A, Siegler M, Parker WF. The use of slow codes and medically futile codes in practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(2):326–335.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piscitello GM, Tyker A, Schenker Y, Arnold RM, Siegler M, Parker WF. Disparities in unilateral do not resuscitate order use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(8):1012–1022. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson EM, Cadge W, Zollfrank AA, Cremens MC, Courtwright AM. After the DNR: surrogates who persist in requesting cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Hastings Cent Rep. 2017;47(1):10–19. doi: 10.1002/hast.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dzeng E, Colaianni A, Roland M, et al. Influence of institutional culture and policies on do-not-resuscitate decision making at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):812–819. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piscitello GM, Lyons PG, Koch VG, Parker WF, Huber MT. Hospital policy variation in addressing decisions to withhold and withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Chest. 2024;165(4):950–958. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batten JN, Blythe JA, Wieten S, et al. Variation in the design of do not resuscitate orders and other code status options: a multi-institutional qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(8):668–677. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gremmels B, Bagchi S. Resuscitation à la carte: ethical concerns about the practice and theory of partial codes. Chest. 2021;160(3):1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]