Abstract

Background

Assessment of glucose uptake by PET imaging under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (HEC) is an insightful tool for quantification of insulin resistance, a hallmark of diabetes and an area of interest in drug development. To enable the use of the method in metabolic trials, the repeatability of dynamic whole-body PET/MRI assessments of the tissue-specific glucose uptake and the total body glucose utilisation were investigated. The study included participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and overweight/obesity, for two repeated examinations in standardised conditions. All participants signed informed consent, and the study plan was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (#2020-04140). After an overnight fast, HEC was established and a series of [18F]FDG-PET/MRI scans were performed. Total body glucose utilisation (M-value) was calculated for the duration of the scan and the tissue-specific metabolic rates of glucose uptake (MRGlu) were calculated using Patlak model. The repeatability was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results

Repeatability was assessed in per protocol set of 12 participants (PPS, defined by a consistent HEC) and in full analysis set (FAS n = 16). The measured M-values and tissue MRGlu demonstrated varying levels of insulin resistance. M-value ICC was 0.95 (95% CI 0.86–0.99) for PPS, indicating excellent repeatability. Tissue-specific MRGlu repeatability was excellent for skeletal muscle (ICC 0.94), and good to at least fair for SAT, VAT, myocardium, and brain. The FAS had lower, but at least fair repeatability, emphasising the importance of standardisation in metabolic assessments.

Conclusion

Dynamic [18F]FDG-PET/MRI provides quantitative information on tissue-specific insulin sensitivity during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp with a reliability comparable to total body glucose utilisation assessment. The method has potential to add value in monitoring and evaluating T2DM treatment effects on glucose uptake and insulin resistance in interventional trials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13550-025-01298-4.

Keywords: T2DM, Insulin resistance, FDG, PET/MRI, Repeatability

Introduction

The loss of insulin sensitivity and altered glucose metabolism are important components of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and its development. Insulin stimulates tissues to take up glucose, however this sensitivity is gradually lost in the development of insulin resistance [1]. The assessment of tissue-specific insulin sensitivity is therefore important for understanding the underlying pathophysiologic processes of insulin resistance in T2DM and can be a powerful tool for characterizing responses to therapeutic interventions.

The present reference standard for measuring insulin sensitivity is the M-value determination during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (HEC), which through infusion of insulin and glucose, determines the rate of total body glucose disposal at a predetermined steady-state plasma glucose level [2, 3]. Imaging by PET using the glucose analogue fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) during HEC allows for quantification of insulin sensitivity by assessing both the insulin-mediated tissue specific glucose uptake, and the whole-body glucose disposal [4].

Previous studies have shown clear differences in the insulin induced glucose uptake between T2DM and healthy controls in several organs using [18F]FDG-PET and clamp (PET-HEC) [5, 6], but also reported large variances within the T2DM population, demonstrating the heterogeneity of the disease [7, 8]. Furthermore, impaired glucose uptake in the skeletal muscle and adipose tissues, and elevated glucose uptake in the brain under HEC have been shown to be associated with the whole-body insulin resistance, advocating the importance of assessing tissue-specific metabolic alterations and their contribution to T2DM development and treatment effects [8–10].

Recently, dynamic whole-body PET/MRI imaging protocols have been introduced [11] and shown to be feasible for simultaneous assessment of glucose metabolism by combining measurements of tissue-specific insulin-mediated [18F]FDG influx rates (Ki) and derived glucose uptake values, with accurate measurements of tissue depot volumes by MRI [8, 9]. To use these as quantitative imaging biomarkers in interventional clinical trials, assessment of the performance of the method under study conditions is warranted. This typically includes repeatability (test–retest variability) and reproducibility (site to site) assessments. Repeatability refers to variability of the quantitative imaging biomarker when repeated measurements on same participant are acquired on the same experimental unit under identical or nearly identical conditions [12]. Test–retest studies of [18F]FDG standard uptake value (SUV) parameters in oncology patients have shown to have acceptable repeatability and reproducibility with estimated within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) of 9–11% when using the same scanner type and consistency of the protocol parameters and standardised patient preparation and procedures [13, 14].

Total body insulin sensitivity measured as M-value or glucose infusion rate (GIR) in HEC can vary across healthy individuals and T2DM patients. The repeatability of HEC endpoints is subject to variation from different sources, both biological day-to-day variation, and operator-dependent factors. Depending on the method and the population; the intra-individual CV for total body insulin sensitivity measurements have been estimated between 5 and 15% [15, 16]. We hypothesised that the experimental setup during the PET/MRI assessment may introduce additional variability to HEC and should hence be further studied. Furthermore, repeatable total body glucose utilisation values form a basis for evaluating potential additional variation to the tissue specific measurements by PET. The repeatability of tissue insulin sensitivity using a whole-body dynamic PET/MRI assessment has not been reported.

To guide future clinical trials evaluating diabetes drugs that may be able to reverse T2DM-related alterations in tissue-specific insulin sensitivity, the present method study aimed to determine method related variability and repeatability in whole-body glucose uptake and uptake rate in selected tissues by using combined PET/MRI during HEC.

Methods

Study participants

The study was performed in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki [17]. The study plan was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (decision number 2020-04140). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The study included males and females with both previously diagnosed T2DM and overweight/obesity (Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 25.0 and ≤ 38.0 kg/m2). Diagnosed T2DM was verified by subject interview, and approved medication were limited to diet and exercise alone or stable metformin doses for at least 3 months prior to screening. Further inclusion criteria were age 50–70 years, fasting P-glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and ≤ 11 mmol/L, HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol and ≤ 70 mmol/mol at the time of screening visit (Visit 1).

Study protocol

Participants who qualified for the study during screening (Visit 1) returned to the clinic twice for overnight stay followed by HEC—PET/MRI (Visit 2 and Visit 3). The participants were asked to maintain their normal dietary habits at least 3 days prior to Visit 2 and Visit 3. The participants arrived in the clinic in the afternoon on the day before the HEC-PET/MRI, had a standardised evening meal, and fasted overnight (> 10 h) at the clinic. No exercise, consumption of alcohol, caffeine or energy drinks was allowed. Adverse events, vital signs, and physical examinations were recorded. Venous blood samples for the analysis of clinical chemistry, haematology, and metabolic status were analysed by routine analytical methods. Lean body mass was determined by a bioelectrical impedance analysis using the InnerScan® V Segmental Body Composition Monitor (Model BC-545N, Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp

Study protocol of HEC—PET/MRI is summarised in Fig. 1. HEC was started in the morning on overnight-fasted participants with a protocol modified from the hyperinsulinemic clamp method [3]. Two indwelling venous catheters were inserted intravenously: one in a vein of one arm for parallel infusion of glucose and insulin, and the other used for blood sampling, and the arm was placed on a heating pad to obtain arterialised venous blood.

Fig. 1.

Study protocol. HEC is started after overnight fast with fixed insulin infusion (56 mU/m2/min) and variable glucose infusion to stabilise blood glucose to 5.5 mmol/L. HEC and blood sampling is continued throughout the PET/MRI imaging protocol. PET imaging is started at [18F]FDG bolus injection and imaging of thorax for blood input, followed by five whole body PET and simultaneous MR scans. Data is combined for a dynamic dataset and modelled using combined image derived and blood sample data in Patlak model to quantify metabolic rate of glucose uptake in tissues. Total body glucose utilisation (M-value) is calculated from the time of the PET/MRI scan

HEC was initiated by a priming dose (4 min 360 ml/h, 3 min 240 ml/h) of intravenous infusion of insulin (Actrapid 100 IU/ml, Novo Nordisk), followed by a constant infusion rate at 120 ml/h, resulting in 56 mU/m2 /min of insulin infusion. The personalised insulin solution was prepared containing albumin (Albumin Baxalta). The plasma glucose level was kept at a physiological target level (5.5 mmol/L ± 0.5 mmol/L) by infusing with a glucose 200 mg/ml (20%) infusion solution and monitored by frequent (5 min) plasma glucose measurements (HemoCue® Glucose 201 + System (HemoCue AB, Ängelholm, Sweden). Plasma glucose and glucose infusion rates were recorded throughout the clamp. Deviations from the plasma glucose steady state during HEC, were assessed calculating the fraction of plasma glucose measurements that were in-range during each PET/MRI and HEC session. In-range plasma glucose was defined as between 5.0 and 6.0 mmol/L.

During the clamp, the participants were instructed to limit muscle activity (avoid talking and moving), with exception to voiding before positioning in the scanner. After stabile euglycemia was reached, the participant was positioned in the PET/MR supine and arms down, supported and lightly fixed to avoid movement, on continuous infusion using an MR compatible infusion system.

PET/MRI imaging

An integrated PET/MRI system (Signa PET/MRI; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wis, USA) was used for image acquisition. On average 2 h 18 min ± 26 min after clamp start, [18F]FDG was injected (4.07 ± 0.17 MBq/kg) as an intravenous bolus and flushed with saline. Ten-minute dynamic acquisition of the thorax was done at start of bolus. Whole-body imaging from head to toe, with 30 s acquisition of 10 overlapping bed positions was acquired and repeated further 4 times. Between each whole-body series, blood samples were taken, and glucose infusion rate (GIR) was adjusted if necessary.

PET acquisition was performed in listmode in three-dimensional time-of-flight mode. Images were reconstructed with VUE Point FXs, iterations/subsets: 3/28, matrix 128 × 128 pixels and resulting voxel size 4.69 × 4.69 × 2.78 mm, dynamic thorax scan frames: 1 × 10 s, 8 × 5 s, 4 × 10 s, 2 × 15 s, 3 × 20 s, 2 × 30 s, and 6 × 60 s. Corrections for attenuation, decay, scatter, randoms and normalisation were performed as recommended by the manufacturer.

MR attenuation correction scans were performed during each PET acquisition following unmodifiable settings: two-point Dixon sequence TE 1.67 ms, TR 4.05 ms, flip angle 5°, reconstructed voxel size 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.6 mm., and was done in free breathing, except end-expiration breath hold in the thoracic scan.

Blood radioactivity samples

Arterialised venous samples were collected for radioactivity measurement after the thoracic and each of the whole-body PET scans (n = 6 samples). Samples were weighed and radioactivity were measured with a cross-calibrated gamma counter as whole blood and plasma radioactivity.

M-value calculation

Total M-values were calculated using the method by DeFronzo et al. [3] for the entire PET/MRI imaging session (lasting on average 67 min), for both whole-body mass and lean body mass, and applying space correction factor. First, M-values were calculated for the sample time intervals in which underlying parameters were measured (plasma glucose, glucose infusion rate). Subsequently the total M-values were derived by proportionally weighing the M-values from the shorter time intervals.

Image analysis

Image data was analysed by using PMOD software v4.204 (PMOD Technologies LLC, Zurich, Switzerland). Analysis details are provided in Supplement. In short, whole-body dynamic datasets were created by merging the five whole-body PET images onto a timeseries with decay correction. Plasma input curves were prepared combining the image derived and the gamma counted whole blood and plasma activity data. Automatic tissue segmentations were created using the simultaneously acquired MR images [18] and manual segmentations were drawn in PMOD. The metabolic rate of glucose uptake (MRGlu) of each tissue segment were calculated using the Patlak model [19] in PMOD PKIN, using the formula:

where LC was the tissue specific lumped constant, and 1.04 (g/cm3) was used for tissue density. The used lumped constants were: 1.16 for the muscle [20], 1.14 for both adipose tissues [21], 0.65 for the brain [22] and 1 for the rest of the tissues [23, 24].

Statistical methods

Sample size was calculated prior the study. Assuming the ICC is expected at 0.85, under a 5% two-sided type I error rate, a sample of 16 completed study participants will have approximately 90% power to detect an ICC statistically greater than 0.4 (usually considered as a criterion for moderate agreement).

The test–retest repeatability of the measured parameters was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and the two-sided 95% confidence intervals of ICC point estimates. The ICC method used was the ICC 2,1 (two-way random effect, absolute agreement, single measurement model, with the parameter as the dependent variable and with subject and visit as random effects). The lower limits of the 95% confidence intervals were interpreted according to the following repeatability category scale [20, 21]: < 0.4: poor; 0.4–0.59: fair; 0.6–0.74: good; and ≥ 0.75: excellent reliability of the repeatability. Intra-individual CV% was additionally assessed for comparisons in literature, and linear regressions were calculated to evaluate associations.

All descriptive summaries and statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 or later (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), except linear regressions which were calculated using R version 4.2.3. All repeatability testing was performed with a two-sided test using a significance level of 5%. All confidence intervals were two-sided 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Participants

18 participants were included in the study, of which 16 participants (Full analysis population FAS) completed both imaging sessions, and two discontinued due to inability to follow the study protocol. Furthermore, 12 participants were included in the per-protocol set (PPS), which consisted of 4 female and 8 male participants, average age 65 years, BMI 30.7 (Table 1). The exclusion of four participants from the PPS was based on a larger difference than expected (> 100% difference between the two visits) in their plasma insulin levels during the clamp, due to technical issue in the preparation of the personal insulin solutions on either visit (Supplement Fig. 1). Both analysis sets (FAS n = 16 and PPS n = 12) were studied for repeatability.

Table 1.

Demographics, baseline characteristics, glucose and insulin (per protocol set PPS and full analysis set FAS)

| Parameter | PPS | FAS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | N (female/male) | 12 (4/8) | 16 (5/11) |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 64.7 (3.4) | 65.4 (3.2) |

| Median (Min, Max) | 64.5 (59, 70) | 66.0 (59, 70) | |

| Weight (kg) | Mean (SD) | 94.4 (13.0) | 92.9 (11.8) |

| Median (Min, Max) | 93.1 (79, 126) | 91.6 (79, 126) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | Mean (SD) | 30.7 (3.8) | 30.5 (3.9) |

| Median (Min, Max) | 29.8 (25, 37) | 29.8 (25, 37) | |

| Lean body weight (kg) | Mean (SD) | 62.0 (12.2) | 61.6 (11.0) |

| Median (Min, Max) | 64.5 (44, 79) | 64.5 (44, 79) | |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | Visit 2 Mean (SD) | 7.4 (1.0) | 7.3 (0.9) |

| Visit 3 Mean (SD) | 7.6 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.4) | |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | Visit 2 Mean (SD) | 13.2 (6.7) | 12.7 (6.3) |

| Visit 3 Mean (SD) | 13.2 (6.3) | 13.5 (5.5) | |

| Glucose during M-value determination (mmol/L) | Visit 2 Mean (SD) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.3) |

| Visit 3 Mean (SD) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.3) | |

| Insulin during M-value determination (mU/L) | Visit 2 Mean (SD) | 149.2 (39.7) | 139.8 (43.8) |

| Visit 3 Mean (SD) | 158.8 (37.0) | 149.3 (44.3) |

All participants had T2DM, 12 also had hypertension, and 9 had hyperlipidemia diagnosis. Metformin (n = 14) was discontinued for the morning of the imaging study.

Two visits of HEC—PET/MRI were spaced 7 days apart (median, range 5–23 days). Fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels were similar between the two visits (Table 1).

HEC parameters

M-value was determined from the time during the PET/MRI scan which on average lasted 67 min, and on average participants spent 2 h:16 min in HEC before each imaging session and blood sample collection for M-value calculation started. The duration in clamp before the M-value determination, as well as the duration of imaging was longer on visit 2 compared to visit 3 (Supplement Table 1).

Time intervals for M-value calculations were on average 8 min, between the whole-body scans, but ranged between 3 and 21 min, due to varying adjustment times and limited access to blood sampling during the imaging protocol. Intervals were then proportionally weighed in calculation of M-value, covering the whole imaging time.

The stability of HEC (variability of glucose during clamp) was evaluated calculating the fraction of plasma glucose measurements that were in-range during each PET/MRI imaging session (level-in-target between 5–6 mmol/L). The fraction of glucose samples in target range was 0.87 (0.15) on visit 2 and 0.88 (0.22), on visit 3 (PPS).

Repeatability of total body glucose utilisation M-value

In the per protocol set (PPS) the mean M-values were 24.52 µmol/kg/min on the visit 2, and 25.94 µmol/kg/min on the visit 3, ranging between 7.90 and 52.7 µmol/kg/min. The ICC point estimate was 0.95 (95% CI 0.86–0.99), which indicates an excellent reliability for the repeatability. (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Total body glucose utilisation M-value per body weight, M-value per lean body weight (LBW) (µmol/kg/min), metabolic rate of glucose uptake in tissues (MRGlu, µmol/100 g/min); the mean (SD) value on visit 2 and visit 3 and corresponding ICC and intra-individual CV% for the PPS population (n = 12)

| Parameter | Mean (SD) V2 PPS |

Mean (SD) V3 PPS |

ICC | 95% CI | Intra-individual CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-value (µmol/kg/min) | 24.52 (13.64) | 25.94 (15.27) | 0.95 | (0.86–0.99) | 8.25 |

| LBW M-value (µmol/kg/min) | 36.48 (17.95) | 38.75 (21.31) | 0.94 | (0.81–0.98) | 7.54 |

| MRGlu (µmol/100 g/min) | |||||

| Quadriceps left | 4.17 (3.18) | 4.35 (3.26) | 0.94 | (0.83–0.98) | 13.00 |

| Quadriceps right | 3.97 (2.87) | 4.17 (2.92) | 0.95 | (0.86–0.98) | 13.67 |

| SAT | 0.66 (0.29) | 0.71 (0.35) | 0.88 | (0.65–0.96) | 13.84 |

| VAT | 0.93 (0.48) | 0.92 (0.59) | 0.85 | (0.59–0.95) | 15.16 |

| Myocardium | 34.42 (11.11) | 34.27 (12.24) | 0.90 | (0.70–0.97) | 9.48 |

| Brain | 18.80 (3.56) | 19.31 (3.27) | 0.79 | (0.46–0.93) | 5.74 |

| Liver | 2.55 (0.41) | 2.36 (0.46) | 0.66 | (0.22–0.88) | 8.48 |

Fig. 2.

Total body glucose utilisation (M-value) on Visits 2 and 3 (ICC = 0.95 (95% CI 0.86–0.99, PPS)

When adjusted to lean body mass, the M-values for the PPS population were 36.48 µmol/kg/min and 38.75 µmol/kg/min, and the estimated ICC 0.94 (0.81–0.98) also indicating excellent repeatability.

The corresponding M-values for the FAS which included four participants with large difference on plasma insulin on the two visits, were 21.81 µmol/kg/min and 24.17 µmol/kg/min, respectively, and ICC were 0.84 (95% CI 0.63–0.94), indicating a good repeatability (Supplement Table 2). The variation on M-value was mainly due to the differences on the insulin level, as shown by calculating M/I for FAS population (dividing the M-value with corresponding mean plasma insulin), the linear regression between the values from two visits improved from 0.732 to 0.892 (Supplement Fig. 2, Supplement Table 3).

Repeatability of glucose uptake in tissues

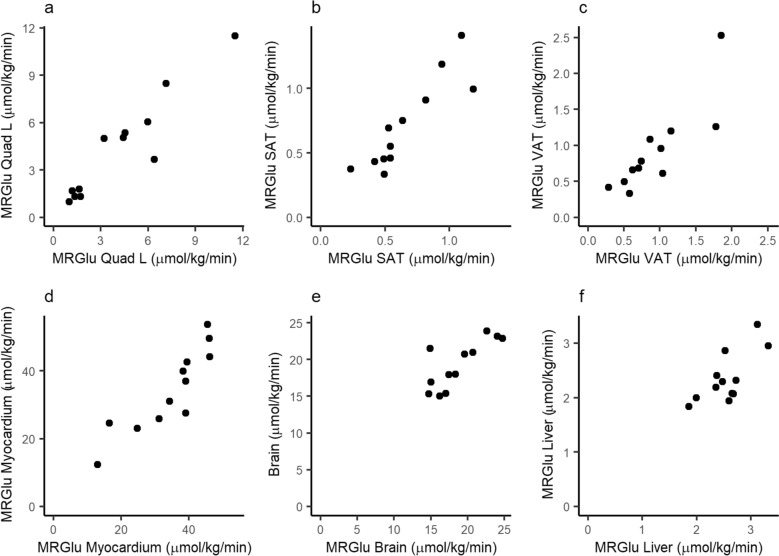

The mean MRGlu values of the two visits and, and respective ICC and its 95% CI, as well as intra-individual CV% are shown in Table 2 and individual results in Fig. 3 for PPS population, and in Supplement for FAS (Supplement Table 2, Supplement Fig. 3). Correlations are presented in Supplement Tables 4 for PPS and Supplement Table 5 for FAS.

Fig. 3.

The metabolic rate of glucose uptake (MRGlu) in tissues on two visits. Visit 2 on x-axis and Visit 3 on y-axis, PPS (ICC; 95% CI) a Quadriceps muscle (0.94: 0.83–0.98), b Subcutaneous adipose tissue (0.88; 0.65–0.96) c Visceral adipose tissue (0.85; 0.59–0.95) d Myocardium (0.90; 0.70–0.97) e Brain (0.79; 0.46–0.93) f Liver (0.66; 0.22–0.88)

Repeatability of the tissue-specific glucose uptake rates between the two visits was excellent in the measurement of MRGlu in the skeletal muscle (left quadricep) with ICC 0.94 (95% CI 0.83–0.98) for the PPS. The corresponding repeatability for FAS population was ICC 0.78 (95% CI 0.50–0.91). Both the left and the right quadriceps femoris were assessed on average 4.17 and 4.35 µmol/100 g/min for left quadricep and 3.97 and 4.17 µmol/100 g/min for right, on visits 2 and 3, respectively, with similar repeatability and good correlation (r2 = 0.983, p < 0.0001). MRGlu in quadricep muscle correlated with M-value (r2 = 0.855, p < 0.0001) (Supplement Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Associations of different tissues MRGlu (at Visit 3, PPS). Linear regression a MRGlu SAT versus MRGlu muscle (Quad L) r2 = 0.78, p < 0.00001 b MRGlu VAT versus MRGlu Quad L r2 = 0.72, p < 0.00001, c MRGlu Brain versus MRGlu Quad L r2 = 0.00, p = 0.95, d MRGlu Liver versus MRGlu Quad L r2 = 0.02, p = 0.49, e MRGlu Myocardium versus MRGlu Quad L r2 = 0.45 p = 0.0003, f MRGlu VAT versus MRGlu SAT r2 = 0.81 p < 0.00001

Glucose uptake rate in adipose tissues was 0.66 and 0.71 µmol/100 g/min in SAT and 0.93 and 0.92 µmol/100 g/min in VAT on visits 2 and 3, respectively (PPS). Repeatability was good for SAT (ICC 0.88; 95% CI 0.65–0.96), and at least fair for VAT (ICC 0.85; 95% CI 0.59–0.95). Adipose tissue MRGlu correlated with muscle MRGlu (Fig. 4), as well as with M-value (Supplement Table 4).

Myocardium had the highest glucose uptake per volume with 34.42 (11.11) µmol/100 g/min and 34.27 (12.24) µmol/100 g/min on visits 2 and 3 (PPS), respectively. Repeatability was good, with ICC 0.90 (95% CI 0.70–0.97). MRGlu in myocardium correlated with M-value, as well as with MRGlu in muscle and adipose tissue.

Repeatability of MRGlu in brain for PPS was at least fair with ICC 0.79 (95% CI 0.46–0.93), and similar also when including the participants with a large difference on the plasma insulin levels between two visits (FAS population, Supplement Table 2). MRGlu in brain (PPS) was 18.80 (3.56) µmol/100 g/min and 19.31 (3.27) µmol/100 g/min on visits 2 and 3, respectively. No clear association with M-value or other tissue MRGlu was observed.

For the liver MRGlu, the ICC was estimate was similar in PPS and FAS populations, with high variability of the confidence limit, ICC 0.66 (95% CI 0.22–0.88) for PPS and 0.68 (95% CI 0.32–0.87) for FAS. The intra individual CV% was however 8.5 and 9.58%, respectively. Liver MRGlu was 2.55 (0.41) µmol/100 g/min and 2.36 (0.46) on visits 2 and 3, respectively, and did not correlate with muscle MRGlu or M-value.

Discussion

T2DM (Type 2 diabetes mellitus) continues to be an increasing global health issue with heterogenous disease characteristic, risk of complications and response to treatment [7]. Insulin regulates glucose homeostasis and metabolism by stimulating glucose uptake in tissues by translocating glucose transporter GLUT4 onto the cell membrane, whereas impaired insulin sensitivity in muscle, liver and adipose tissue are recognised as key components in progression of T2DM [1]. Tissue specific insulin sensitivity and resistance can be quantified by measuring glucose uptake by using glucose analogue [18F]FDG under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (HEC), and these techniques in combination have been shown to prove valuable insights for understanding tissue metabolism in relation to obesity, diabetes, exercise, and bariatric surgery [4–6, 8, 9]. Changes in muscle, adipose tissue and brain glucose metabolism can impact and contribute selectively on the pathophysiology of metabolic disease and therapy. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previously published studies that evaluate the repeatability of tissue insulin sensitivity using a whole-body dynamic [18F]FDG assessment. In this study we assessed the repeatability of the HEC-PET/MRI method.

We here report that the measurement of total body insulin induced glucose utilisation, ie whole-body M-values derived from HEC acquired at the same time as the PET/MRI scan, were repeatable in participants with T2DM, measured twice in identical conditions, one week apart. ICC of M-value was 0.95 (95% CI 0.86–0.99, PPS), indicating excellent repeatability. Also lean body adjusted M-value had excellent repeatability, with a reliability comparable to previously reported standard HEC derived M-value assessments.

On the measurement of tissue-specific insulin sensitivity during HEC, [18F]FDG-PET/MRI provided information with a reliability comparable to M-value on several tissues. The glucose uptake rates (MRGlu) had excellent repeatability on readouts from the skeletal muscle (left and right quadriceps femoris) with lower 95% confidence limit of ICC ≥ 0.75. Muscle glucose uptake also showed correlation with M-value, as has also been reported previously [8]. The repeatability of MRGlu in SAT, VAT, myocardium and brain was good to at least fair (lower 95% confidence limit of ICC ranged between 0.42 and 0.87).

Comparisons between previous studies for M-value repeatability can be challenging due to differences in experimental setups, in particular differences in insulin infusion concentrations used in the clamp, and also due to different methods used for assessing repeatability. Since this study was designed for participants with T2DM, a higher concentration of insulin was selected in order to reach steady state within two hours. This can lead to slightly higher M-values than seen in literature, however, the heterogeneity of T2DM population also plays a role in defining an average for this population. In the two previously published studies with the same method, the M-value (adjusted for lean body mass) was 7.17 mg/kg/min (Johansson et al. [9]), and 5.12 mg/kg/min (Boersma et al. [8]). Converting the units, the values in our study equal to 6.57 mg/kg/min and 6.97 mg/kg/min, for PPS visit 2 and 3, respectively. On repeatability of glucose disposal, studies on nondiabetic participants and rather small numbers of participants have reported intra-individual CV of 10.3 ± 8.5% in M-value [15] and for glucose infusion rate (GIR) between the three measurements CV 5.8 (2.6, 22.0)% [25]. In another study with healthy participants, GIR adjusted by fat-free mass had r ~ 0.70, and reported a CV % of ~ 14.7% [26]. In our study the CV % for M-value was 8.25% (PPS, n = 12). When including the participants with a large variation in their insulin levels on the visits (FAS), the intra-individual CV was 17.62% (n = 16). We assumed to see some additional protocol-related variation, however, we conclude that the repeatability in this experimental setting is particularly good and within range of other outpatient settings.

Initiating and stabilising HEC especially for participants with T2DM without prior knowledge of their total body insulin resistance can be challenging when performed with manual adjustments of the clamp. In our study, we also saw a wide range of insulin sensitivity between the participants, as can be expected on relatively newly-onset T2DM with only diet/exercise or metformin as treatment. The duration of the clamp was shorter in the second imaging visit, as the setup of the clamp with previous knowledge of the GIR helped to stabilise the clamp slightly faster. This small difference on the duration and the stability of establishing the clamp could explain some difference observed between the two visits. Potentially, further improvement could be expected if prior calculations of participants individual GIR need were performed before the procedure, such as calculating PREDIM-index [27, 28], or performing an automated clamp, provided that experimental setup can be performed in a MRI safe way [29].

Performing quantifiable and comparable glucose metabolism studies using PET and [18F]FDG requires careful standardisation of the study procedures, due to both the biological variance of metabolic processes, and the technical aspects. We noticed larger than expected variation in plasma insulin levels between the two visits on four participants, caused by a technical issue during insulin preparation. M-values can be compensated to the variation in plasma insulin levels by dividing M-value over the individual’s mean plasma insulin (M/I). The M/I in FAS population had indeed lower variation, showing that the differences between the two clamps explain the poorer repeatability of the FAS readouts. The imaging readouts however cannot be normalised to the respective insulin values, since glucose uptake dependence on the insulin level varies between different tissues. The repeatability was calculated nevertheless for both populations. These results emphasise the need for strict standardisation of the preparations in the clamp procedure.

Acquiring glucose uptake data using a whole-body dynamic protocol on PET/MRI hybrid scanners is a recently developed method. Used together with the HEC procedure it offers the advantage of producing kinetic readouts of all tissues in only one scan, using a conventional PET/MRI scanner. Over the course of one hour, raw data from tissues is collected from 30 s of image acquisition per bed position, repeated for a total of five timepoints. Despite the substantially lower amount of acquired signal in the whole-body protocol compared to a standard, one station dynamic scan, the method performs well due to improved technology (time-of-flight PET) and the kinetic analysis using combined image and blood sample derived data for modelling. Previous work has shown that the data can be used for modelling even in pixelwise analyses for parametric mapping, facilitating “imiomics” [30] approaches for glucose metabolism studies. Here we report the regional analysis of the tissues of interest in order to minimise the effect of modelling error in areas of low signal, especially in SAT. Noisy data of parametric map could result in under- or overestimation of uptake rates. The results presented here are comparable to previously reported glucose uptake rates in tissues [5, 6, 8, 9].

The repeatability of MRGlu in the liver had highest variance on the ICC estimate CI than other measured tissues but showed small CV%. We used the Patlak method of irreversible kinetics also for liver, assuming that the prolonged HEC would shunt glucose outflux, however, in participants with T2DM some endogenous glucose production (EGP) could still be remaining and account for the observed variability. This limitation could be overcome with measuring urinary component at late timepoint and calculating the compensation for the EGP [2].

We can assume that the repeatability results presented here can be extrapolated to other HEC—PET imaging protocols and the M-values derived in an imaging setting, when standardisation of study participants is performed adequately. The advantage of a dynamic whole-body PET/MRI protocol is that it allows kinetic readouts of several tissues on the same imaging session with a potential to combine with additional MRI readouts such as body composition and ectopic fat, which are important parameters when investigating metabolic changes.

Conclusions

Dynamic [18F]FDG-PET/MRI combined with hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp provides selective information on tissue-specific insulin sensitivity with a good repeatability. The whole-body M-values derived from HEC as well as the skeletal muscle glucose uptake indicated an excellent repeatability of the measurements in participants with T2DM. The method has potential to provide benefits in monitoring and evaluating T2DM treatment effects in interventional trials.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Uppsala University PET/MRI imaging team and CTC study team for performing the imaging and HEC; David Lassiter, Linnea Eriksson and Joakim Englund from CTC for data processing and statistical analysis, and Anna Prejner from Antaros Medical for image handling.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CV

Coefficient of variation

- EGP

Endogenous glucose production

- FAS

Full analysis set

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- GIR

Glucose infusion rate

- HEC

Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- LC

Lumped constant

- LBW

Lean body weight

- M/I

Ratio of M-value and insulin

- MRGlu

Metabolic rate of glucose uptake

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- P

Plasma

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PPS

Per protocol set

- SAT

Subcutaneus adipose tissue

- SUV

Standard uptake value

- T2DM

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- VAT

Visceral adipose tissue

Author contributions

The study conception and design: IL, HL, FS, SE, HH, SP, JK. SS. ML, TC, ZM. LJ. Clinical investigation: HL, FS; Software and validation: SE, AK, JK, IL; Analysis: IL, SE, HH, AK. IL wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors commented on versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was a collaboration between the sponsor Antaros Medical AB, Sweden, and Eli Lilly and company, United States, provider of funding for the study.

Availability of data and materials

The analysed datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Etikprövningsmyndigheten, Uppsala, Sweden), Drn 2020-04140, including radiation safety authority (drn SSM2020-5219). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained.

Competing interests

Employments at the time of study: Iina Laitinen, Simon Ekström, Henrik Haraldsson, Stefan Pierrou, Alexander Korenyushkin, Joel Kullberg and Lars Johansson by Antaros Medical AB, Mölndal, Sweden; Helena Litorp and Folke Sjöroos by Clinical Trial Consultants CTC, Uppsala, Sweden; Sudeepti Southekal, Ming Lu, Tamer Coskun and Zvonko Milicevic by Eli Lilly and company.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.James DE, Stockli J, Birnbaum MJ. The aetiology and molecular landscape of insulin resistance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:751–71. 10.1038/s41580-021-00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gastaldelli A. Measuring and estimating insulin resistance in clinical and research settings. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30:1549–63. 10.1002/oby.23503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–23. 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuutila P, Knuuti J, Ruotsalainen U, Koivisto VA, Eronen E, Teräs M, et al. Insulin resistance is localized to skeletal but not heart muscle in type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:E756–62. 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.5.E756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh HE, van Vliet S, Meyer GA, Laforest R, Gropler RJ, Klein S, et al. Heterogeneity in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake among different muscle groups in healthy lean people and people with obesity. Diabetologia. 2021;64:1158–68. 10.1007/s00125-021-05383-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh HE, van Vliet S, Pietka TA, Meyer GA, Razani B, Laforest R, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolic function and insulin sensitivity in people with obesity. Diabetes. 2021;70:2225–36. 10.2337/db21-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Karajamaki A, Martinell M, Dorkhan M, Carlsson A, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:361–9. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boersma GJ, Johansson E, Pereira MJ, Heurling K, Skrtic S, Lau J, et al. Altered glucose uptake in muscle, visceral adipose tissue, and brain predict whole-body insulin resistance and may contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes: a combined PET/MR study. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50:627–39. 10.1055/a-0643-4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson E, Lubberink M, Heurling K, Eriksson JW, Skrtic S, Ahlstrom H, et al. Whole-body imaging of tissue-specific insulin sensitivity and body composition by using an integrated PET/MR system: a feasibility study. Radiology. 2018;286:271–8. 10.1148/radiol.2017162949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebelos E, Immonen H, Bucci M, Hannukainen JC, Nummenmaa L, Honka MJ, et al. Brain glucose uptake is associated with endogenous glucose production in obese patients before and after bariatric surgery and predicts metabolic outcome at follow-up. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:218–26. 10.1111/dom.13501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakatsanis NA, Lodge MA, Tahari AK, Zhou Y, Wahl RL, Rahmim A. Dynamic whole-body PET parametric imaging: I. Concept, acquisition protocol optimization and clinical application. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:7391–418. 10.1088/0031-9155/58/20/7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raunig DL, McShane LM, Pennello G, Gatsonis C, Carson PL, Voyvodic JT, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: a review of statistical methods for technical performance assessment. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;24:27–67. 10.1177/0962280214537344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurland BF, Peterson LM, Shields AT, Lee JH, Byrd DW, Novakova-Jiresova A, et al. Test-retest reproducibility of (18)F-FDG PET/CT uptake in cancer patients within a qualified and calibrated local network. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:608–14. 10.2967/jnumed.118.209544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang EP, Wang XF, Choudhury KR, McShane LM, Gönen M, Ye J, et al. Meta-analysis of the technical performance of an imaging procedure: guidelines and statistical methodology. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;24:141–74. 10.1177/0962280214537394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le DS, Brookshire T, Krakoff J, Bunt JC. Repeatability and reproducibility of the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and the tracer dilution technique in a controlled inpatient setting. Metabolism. 2009;58:304–10. 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mather KJ, Hunt AE, Steinberg HO, Paradisi G, Hook G, Katz A, et al. Repeatability characteristics of simple indices of insulin resistance: implications for research applications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5457–64. 10.1210/jcem.86.11.7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association TWM. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. www.wma.net; 2013. [PubMed]

- 18.Ekstrom S, Pilia M, Kullberg J, Ahlstrom H, Strand R, Malmberg F. Faster dense deformable image registration by utilizing both CPU and GPU. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2021;8: 014002. 10.1117/1.JMI.8.1.014002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:1–7. 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peltoniemi P, Lönnroth P, Laine H, Oikonen V, Tolvanen T, Grönroos T, et al. Lumped constant for [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose in skeletal muscles of obese and nonobese humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E1122–30. 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virtanen KA, Peltoniemi P, Marjamäki P, Asola M, Strindberg L, Parkkola R, et al. Human adipose tissue glucose uptake determined using [(18)F]-fluoro-deoxy-glucose ([(18)F]FDG) and PET in combination with microdialysis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2171–9. 10.1007/s001250100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu HM, Bergsneider M, Glenn TC, Yeh E, Hovda DA, Phelps ME, et al. Measurement of the global lumped constant for 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose in normal human brain using [15O]water and 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography imaging. A method with validation based on multiple methodologies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2003;5:32–41. 10.1016/s1536-1632(02)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng CK, Soufer R, McNulty PH. Effect of hyperinsulinemia on myocardial fluorine-18-FDG uptake. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalliokoski T, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA, Iozzo P, Bucci M, Svedstrom E, et al. Pancreatic glucose uptake in vivo in men with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1909–14. 10.1210/jc.2006-2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soop M, Nygren J, Brismar K, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O. The hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic glucose clamp: reproducibility and metabolic effects of prolonged insulin infusion in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond). 2000;98:367–74. 10.1042/cs0980367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokemark L, Froden A, Attvall S, Wikstrand J, Fagerberg B. The euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp examination: variability and reproducibility. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2000;60:27–36. 10.1080/00365510050185010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tura A, Chemello G, Szendroedi J, Gobl C, Faerch K, Vrbikova J, et al. Prediction of clamp-derived insulin sensitivity from the oral glucose insulin sensitivity index. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1135–41. 10.1007/s00125-018-4568-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebelos E, Honka MJ. PREDIM index: a useful tool for the application of the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44:631–4. 10.1007/s40618-020-01352-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heise T, Zijlstra E, Nosek L, Heckermann S, Plum-Morschel L, Forst T. Euglycaemic glucose clamp: what it can and cannot do, and how to do it. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:962–72. 10.1111/dom.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strand R, Malmberg F, Johansson L, Lind L, Sundbom M, Ahlstrom H, et al. A concept for holistic whole body MRI data analysis. Imiomics PLoS One. 2017;12: e0169966. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analysed datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.