Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a kidney disease. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) significantly contribute to diabetic nephropathy (DN), although the precise mechanisms involved have not yet been fully understood. The objective of this research was to explore the potential of mitochondrial and ERS genes as pivotal genetic elements in individuals with DN and to elucidate their fundamental molecular mechanisms. The datasets GSE30528 and GSE30122 were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Firstly, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (DN and control samples) were identified by differential expression analysis. Candidate genes were obtained by intersecting the DEGs with mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. The key genes were identified through three machine learning methods, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and expression validation. Subsequently, a nomogram model for DN was constructed. Moreover, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), immune infiltration, molecular regulatory networks of key genes were explored, Later, predicted their drugs. Finally, three key genes (GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1) were identified by expression validation and ROC validation and three key genes were all down-regulated in DN. Meanwhile, RT-qPCR analysis yielded the same results. In addition, the nomogram model of key genes was constructed, and the model had a good prediction effect. GSEA showed that the top 3 most prominent pathways shared by the 3 key genes included oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, and ribosome. Immune cells, including gamma-delta T cells, activated mast cells, and M2 macrophages, exhibited differential infiltration between the DN group and the control group. A total of 23 lncRNAs targeting intersecting miRNAs of three key genes. There were 4 drugs associated with the three key genes. In this research, three key genes (GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1) mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related gene in DN were identified, providing a potential theoretical basis for DN treatment. However, this study still has certain limitations. This study only used a single dataset for analysis and validation, so the results of the study may not fully reflect the diversity of DN patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-11097-5.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Mitochondria, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Key genes, Machine learning

Subject terms: Chronic kidney disease, Bioinformatics

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the main complications of diabetes1relevant data show that with the increase in the global prevalence of diabetes, the number of patients with DN is also gradually increasing2. DN is closely related to the changes in metabolism and hemodynamics of diabetes. When the body remains in a state of hyperglycemia continuously, the chronic vascular inflammation and metabolic disorders caused thereby lead to the progressive deterioration of renal function and eventually result in renal failure3. The main characteristics of DN are the increased filtration of proteins in the urine, increased of serum creatinine and decline in glomerular filtration rate4. Pathological biopsy of the kidneys of patients with diabetic nephropathy can reveal structural changes in the kidneys, including podocyte dysfunction, thickening of the basement membrane, mesangial dilation, glomerular sclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis5. However, the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy has not been fully elucidated so far. In terms of clinical treatment, the current treatment of DN mainly focuses on blood sugar control6reducing the body’s inflammation and regulating the body’s metabolism7while the targeted therapeutic drugs for DN are still lacking8. Therefore, deeper exploration is needed to explore the pathogenesis of DN and study new biomarkers to find new therapeutic methods for DN.

Mitochondria are one of the important organelles existing in eukaryotic cells, which are the main sites for aerobic respiration and provide the necessary energy for cellular activities9. When various acute or chronic injuries occur in the body or organs, it can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction10. Mitochondrial damage can cause metabolic dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation and cell death11all of which are key factors for the progression of DN12. Therefore, studying the key mechanisms of mitochondrial lesions in the progression of diabetic nephropathy and maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis as a therapeutic strategy for DN has broad prospects.

Endoplasmic reticulum(ER) provides a place for the synthesis, folding, and post-translational modification of proteins in cells13. Moderate ER stress is conducive to repairing and stabilizing the intracellular environment. Related studies have indicated that ER stress and homeostasis are associated with the pathogenesis of DN, such as participating in the epithelium-mesenchymal transformation of DN14podocellular apoptosis and calcium homeostasis disorders15etc. But the specific mechanism of action remains unclear. These studies suggest that changes in mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum functions may significantly contribute to the progression of DN. However, the specific mechanisms of their interaction, as well as markers involved in this process, remain unclear.

In recent years, bioinformatics has emerged as a crucial tool for deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying complex diseases, detecting potential biomarkers, and uncovering novel personalized therapeutic approaches16. Researchers extensively utilize bioinformatics to investigate disease mechanisms, facilitate drug discovery, and advance personalized medicine17. In the field of DN research, Geng Xiao-Dong et al. employed bioinformatics analysis to pinpoint key genes associated with diabetic nephropathy18; Peng Yan et al. have revealed the pathophysiological relationship between diabetic nephropathy and periodontitis in the context of aging through bioinformatics19. It can be seen that bioinformatics technology also makes significant contributions in the field of DN diseases.

In summary, based on the transcriptome data of DN, this study obtained key genes associated with mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress through bioinformatics analysis, which seeks to explore the potential molecular mechanisms of key genes in DN, with a view to providing new references for diagnosing and subsequent managing patients with DN patients.

Materials and methods

Source of data

Two sets of transcriptomic data related to DN, namely GSE30528 GSE30122, were gathered from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). In the GSE30528 dataset (sequencing platform: GPL571), renal samples were obtained from 9 individuals with DN and 13 healthy control subjects. GSE30122 (sequencing platform: GPL571) selected human kidney samples from 19 individuals with diabetic nephropathy and 50 healthy controls. The clinical information of the GSE30528 and GSE30122 datasets was shown in Supplementary Tables S1-2. The clinical information in GSE30528 included sample names, tissue sources, species, tissue subregions, and disease states. The clinical information in GSE30122 included sample names, disease states, tissue subregions, and species. Diabetic kidney disease was defined as the presence of diabetes, proteinuria, a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min, histologic changes consistent with DKD, and the absence of underlying causes such as hepatitis, HIV, lupus, or other glomerulonephritis20. Control samples were obtained from healthy living transplant donors. The Mitochondrial Protein Reference Set 3.0 (MitoCarta3.0) database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta) (Supplementary Table S5)21 yielded a total of 1136 mitochondria-related genes (MRGs). The molecular signatures database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) (Supplementary Table S6)22 provided 1406 endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes (ERSGs).

Differential gene expression analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using the psych package (v 2.1.6)23 to understand the distribution of samples between DN and controls. The DEGs between DN and normal samples in GSE30528 dataset were identified by the limma package (v 3.58.1)24. The screening conditions was p < 0.05 & |log2 Fold Change|>0.5. The ggplot2 package (v 3.4.1)25 was used to plot the DEG volcano plot and mark the ten most significantly up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs. The ComplexHeatmap package (version 2.14.0)26 was utilized to generate a heatmap visualization.

Identification and functional enrichment analysis of potential candidate genes

The ggvenn package (v 0.1.9)27 was used to identify candidate genes by intersecting DEGs, MRGs, and ERSGs. The clusterProfiler package (v 4.2.2)28 was applied for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)29–31 enrichment analyses were performed on the candidate genes, with an adjusted p-value (adj.p) of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Building a network of protein-protein interactions (PPI)

The candidate genes were input into the interacting genes (STRING) database (https://string-db.org/) (confidence ≥ 0.4) to identify interacting genes, and their PPI network was constructed and graphically displayed using Cytoscape (v 3.10.0)32.

Machine learning

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) achieved feature sparsity through L1 regularization, excelled in handling high-dimensional linear data, and rapidly screened candidate genes with significant linear associations from thousands of genes33. Support Vector Machine Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE), based on nonlinear kernel functions, was sensitive to the nonlinear associations between genes and diseases, further performed deep ranking of candidate genes, and optimized feature subsets. As an unsupervised feature validation algorithm34Boruta evaluated the importance of real features by generating “shadow features”, effectively filtered random noise and false-positive results, and ensured the biological authenticity of the selected genes35. Genes retained by taking the intersection of the results from the three algorithms simultaneously met the requirements of linear correlation, nonlinear predictive performance, and noise resistance. This approach avoided the bias of a single algorithm, enhanced the biological significance of the feature set and the generalization ability of the model through multi-method consensus, and ultimately improved the accuracy and stability of disease diagnosis or mechanistic research. Therefore, these three algorithms were selected for further screening of candidate genes. LASSO regression was performed on the candidate genes with the glmnet package (v 4.1.8)36and feature genes 1 were obtained. Feature genes 2 were obtained using the caret package (v 6.0.94)37 the Support Vector Machine Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) algorithm on the candidate genes. The Boruta package (v 8.0.0)35was utilized to perform Boruta detection on the candidate genes, and Feature genes 3 were obtained. The Venn diagram was generated using the ggvenn package (v 0.1.9)27 and the overlapping genes from the three algorithms were selected as candidate feature genes.

Expression validation and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

In GSE30528 and GSE30122, genes with consistent expression trends and significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups were obtained by Wilcoxon test for subsequent analysis. Then, ROC curves of each characterized gene was plotted using the pROC package (v 1.18.0)38 in GSE30528 and GSE30122, and genes demonstrating an area under the curve (AUC) value above 0.7 were classified as key genes.

Nomogram construction and evaluation

The nomogram of key genes were constructed using the rms package (v 6.5-0)39ROC (AUC > 0.6) were generated by the pROC package (v 1.18.0)38decision curves (probability threshold < 0)were plotted using the ggDCA package (v 1.2)40The rms package (v 6.5-0)39 calibrate function (P > 0.05) was used to plot calibration curves to assess the accuracy of the nomogram.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

To further elucidate the biological roles and signaling pathways of key genes involved in DN progression, the “c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt” were obtained from the MSigDB to serve as background gene set. In GSE30528, the correlation coefficients (p < 0.05) between key Genes and other genes were calculated and ranked using the psych package (v 2.1.6)23then GSEA was performed using the enrichplot package (v 1.18.3)41 (adj.p < 0.05, |Normalized Enrichment Score (NES)| > 1 ).

Immune infiltration analysis

PCA using the psych package (v 2.1.6)23 to understand the two sample distributions in GSE30528 dataset. Proportion of 22 immune cells infiltrated between DN and controls was analyzed using the immunedeconv package (v 2.1.0)42. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the differences (p < 0.05) in immune infiltrating cells between DN and controls. The psych package (v 2.1.6)23 was employed to perform Spearman correlation analysis, assessing differential immune cells and their associations with key genes and other immune cells.

Analysis of key gene expression in single cells

The single-cell dataset GSE131882 of DN was obtained from the Renal Disease Single-Cell Sequencing Database (http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/), and a package of bubble plots was used to demonstrate the expression of each key gene across cellular subpopulations. Bubble diagram showing expression of key genes in various cell subpopulations.

Characterization of clinical features

Correlation of key genes with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and serum creatinine (SCR) based on clinical characterization of renal diseases in the Nephroseq v5 database (http://v5.nephroseq.org) analyzed using the psych package(v 2.1.6)23.

Construction of molecular regulatory networks

The miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) and TargetScan (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) were utilized to forecast miRNAs that target the key genes, and the predicted miRNAs were intersected to find common miRNAs. The StarBase (https://rnasysu.com/encori/) was utilized to predict lncRNAs that target the common miRNAs (clipExpNum > 20). The network depicting lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions was established utilizing ggsankey package.(v 0.0.9)43.

Drug prediction analysis

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database database (CTD, https://ctdbase.org/) was applied to obtain medications potentially targeting the key genes (Reference Count > = 2). Ultimately, a network depicting drug-key genes interactions was established utilizing ggsankey package(v 0.0.9)43.

Real-Time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

To validate that important genes are expressed in clinical samples, RT-qPCR analysis was performed. Specifically, a cumulative total of 10 blood samples (5 DN and 5 normal)44were acquired from the clinic in the Kunming Medical University’s first affiliated hospital. The clinical information of the samples was presented in Supplementary Table S3. All participants were given informed consent. The study had the approval of the Primary Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University ethics committee (approval number: Ethical Review L No. 83 (2025)). The experiment was carried out using the Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR kit from Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The sequences of all primers are available in Supplementary Table S4. The qPCR assay was performed with CFX96 Connect Real-time Quantitative Fluorescence PCR Instrument (Bio-Rad, USA) (pre-denaturation at 95℃ for 1 min, denaturation at 95℃ for 20s, annealing at 55℃ for 20s, extension at 72℃ for 30s, a total of 40 cycles). The 2-ΔΔCT method was used for relative quantification of mRNAs. The results from the RT-qPCR were exported to Excel, and then imported into Graphpad Prism 10 (https://www.graphpad.com/) for statistical analysis and visualization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R programming language (version 4.3.1). Significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of candidate genes

To evaluate the status of samples in GSE30528, PCA was performed, and the results showed that the samples from the DN and normal groups were clearly separated (Fig. 1a). Then, a total of 1,906 DEGs were then identified from GSE30528 between the DN and control groups. In comparison to the control samples, the DN samples had 729 up-regulated genes such as LTF, C3, LUM, and IGLC1 and 1177 down-regulated genes such as LOX, PRKAR2B, NPHS1, and TNNI2 (p < 0.05 & |log2 FC| > 0.5) (Fig. 1b-c). The overlap between 1,906 DEGs, 1,136 MRGs, and 1406 ERSGs was taken to obtain seven candidate genes for subsequent studies (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

(a) Central tendency and variability of two sets of data. (b, c) The volcano map and heat map of DEGs. (d) The Venn diagram of 7 candidate genes obtained by overlapping DEGs, MRGs, and ERSGs.

Functional analysis of candidate genes

GO analysis revealed that seven candidate genes were associated with 272 GO signaling pathways, comprising 10 cellular constituents, 31 molecular functions, and 231 biological processes, demonstrating notable enrichment of 10 GO enrichment analyses such as apoptotic mitochondrial changes, mitochondrial transport, negative regulation of mitochondrion organization, and so on (adj.p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). KEGG enrichment analysis identified 11 pathways, including alzheimer disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, apoptosis, and so on (adj.p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, the interactions of the 7 candidate genes at the protein level were analyzed. Five of the genes were shown to have interactions at the protein level, with the PPI network containing 5 nodes and 4 edges. VDAC1 was found to interact with PPIF and TSPO at the protein level, and PMAIP1 was found to interact with BID at the protein level (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

(a) The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis network diagram. (b) The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis pathways diagram. (c) The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of 7 candidate genes at the protein level.

Identification of biomarker key genes

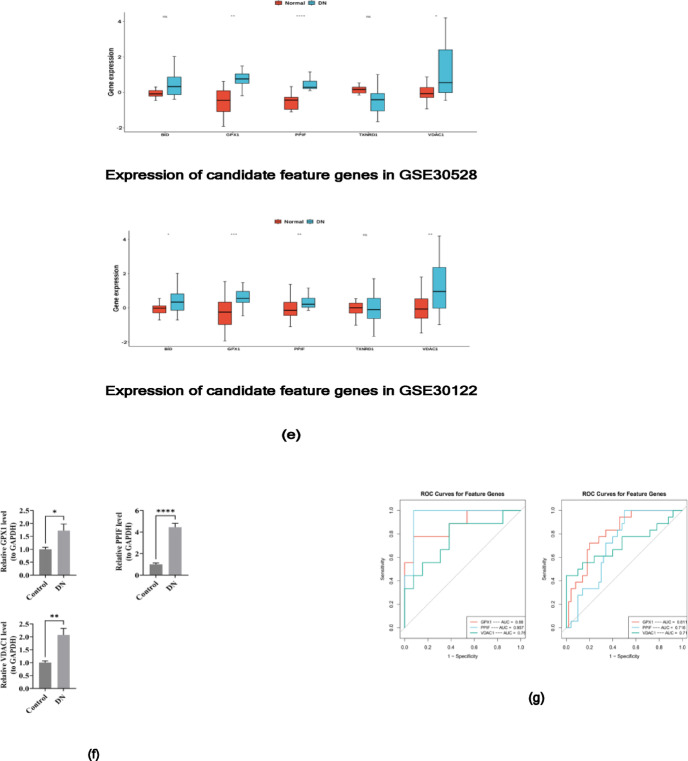

To obtain key genes associated with DN diagnosis, candidate genes were screened using each of the three machine learning algorithms. LASSO regression analysis shown that when the log(lambda.min) value was − 4.6154, the regression coefficients of 5 genes were not zero. Thus, these 5 genes were selected as the characteristic genes including VDAC1, PPIF, GPX1, TXNRD1, and BID(Fig. 3a). SVM-RFE analysis was conducted, and the results showed that the highest accuracy was achieved when the number of variables was 6. Therefore, these 6 genes were selected as the feature genes 2 including VDAC1, PPIF, GPX1, TXNRD1, BID, and TSPO (Fig. 3b). 6 feature genes 3 were obtained using the Boruta analysis (Fig. 3c). Then, by intersecting the characteristic genes obtained from the above three algorithms, and five candidate feature genes were obtained, including VDAC1, PPIF, GPX1, TXNRD1, BID (Fig. 3d). In order to understand the distinctions in the expression of candidate characterized genes in GSE30528 and GSE30122, three genes (GPX1, PPIF, and VDAC1) with significant differences in expression and consistent trends between the DN and control groups were obtained by Wilcoxon test, and three key genes were all down-regulated in DN (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3e). Consistent results were achieved through RT-qPCR analysis(Fig. 3f). Next, the ROC curves of the three genes were plotted, and the AUC values of the three genes in GSE30528 and GSE30122 were all exceeding 0.7, which were defined as the key genes (GPX1, PPIF, and VDAC1) to be used as the subsequent analyses (Fig. 3g).

Fig. 3.

(a) LASSO regression coefficient path diagram and LASSO regression regularized path graph: LASSO regression analysis selected 5 feature genes (1) (b) SVM-RFE algorithm selected 6 characteristic genes (2) The ordinate represented the accuracy of cross-validation, which was used to measure the prediction accuracy of the model after cross-validation under different numbers of variables (with “Variables” on the abscissa). (c) Boruta analysis screened 6 feature genes (3) (d) The Venn diagram of 5 candidate feature genes obtained by overlapping the above three algorithms. (e) Three genes (GPX1, PPIF, and VDAC1) were obtained by Wilcoxon test. (f) The results of RT-qPCR analysis showed the same results. (g) The ROC curves of the three genes in GSE30528 (left) and GSE30122 (right). An asterisk (*) was usually leveraged to indicate that p < 0.05, two asterisks (**) represented p < 0.01, three asterisks (***) signified p < 0.001, and four asterisks (****) denoted p < 0.0001. The “ns” was leveraged to represent no significant difference.

Construction of nomogram and functional analysis of key genes

To identify the key genes that predict the probability of developing DN and the associated pathways involved. Constructing the nomogram model of key genes (Fig. 4a). The value of the AUC of the ROC curve was 0.974 and 0.778 in GSE30528, and GSE96804 respectively (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figure S1a), and the DCA indicated that the nomogram model benefited from higher values than individual key genes (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Figure S1b), and the slope of the calibration curve was close to 1 (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Figure S1c), and the Number high risk curve was very closed to standard of the clinical impact curves (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Figure S1d), which were all indicative of the model’s good predictive effect. GSEA showed TOP5 pathway results with significant enrichment of 3 key genes, e.g., the gene GPX1 plays a role in pathways such as ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation, and glutathione metabolism (NES| > 1, p < 0.05). The gene PPIF was significantly enriched in ribosome, glutathione metabolism, and butanoate Metabolism pathways. The gene VDAC1 was significantly enriched in the pathways of fatty acid metabolism, and propanoate Metabolism (Fig. 4f-h). In addition, the top 3 most prominent pathways shared by the 3 key genes include oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, and ribosome (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

(a) The nomogram model of key genes. (b) ROC curve of the nomogram. (c) The decision curve of a nomogram. (d) Calibration curve of the nomogram. (e) The Number of high risk curve and the clinical impact curves. (f–h) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of (f) GPX1, (g) PPIF and (h) VDAC1.

Table 1.

GSEA enrichment analysis.

| pathways |

|---|

| kegg_oxidative_phosphorylation |

| kegg_parkinsons_disease |

| kegg_glutathione_metabolism |

| kegg_glycolysis_gluconeogenesis |

| kegg_citrate_cycle_tca_cycle |

| kegg_valine_leucine_and_isoleucine_degradation |

| kegg_porphyrin_and_chlorophyll_metabolism |

| kegg_fatty_acid_metabolism |

| kegg_peroxisome |

| kegg_butanoate_metabolism |

| kegg_tryptophan_metabolism |

| kegg_lysosome |

| kegg_dilated_cardiomyopathy |

| kegg_arginine_and_proline_metabolism |

| kegg_metabolism_of_xenobiotics_by_cytochrome_p450 |

| kegg_propanoate_metabolism |

| kegg_proximal_tubule_bicarbonate_reclamation |

| kegg_alanine_aspartate_and_glutamate_metabolism |

| kegg_glycine_serine_and_threonine_metabolism |

| kegg_pentose_phosphate_pathway |

| kegg_tyrosine_metabolism |

Immune infiltration analysis

To comprehend the immune cell infiltration differences in control versus DN samples. PCA showed that some of the samples in the DN group and the control group were similar, but not all of them could be fully distinguished by principal components (Fig. 5a). The CIBERSORT algorithm was employed to calculate the infiltration score of 22 immune cells in the GSE30528 samples. It was found that the top 3 cells with the highest proportion of immune cells in the control group were rested natural killer cells, e.g., and in the DN group the top 3 cells were gamma delta T cells, e.g.(Fig. 5b). In addition, the DN and control groups differed significantly (p < 0.05) in activated mast cells, M2 macrophages, and gamma-delta T cells (Fig. 5c). Then, Spearman’s analysis revealed positive correlations between gamma delta T cells and M2 macrophages, and between activated mast cells and M2 macrophages, suggesting that they may act synergistically in certain biological processes (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, GPX1 showed significant positive correlation with plasma B cells, gamma delta T cells, activated mast cells, M2 macrophages; PPIF showed significant negative correlation with gamma delta T cells, CD4 + naive T cells, activated mast cells, M2 macrophages; VDAC1 demonstrated significant positive correlation with CD4 + naive T cells, activated mast cells (p < 0.05, |correlation (cor)| > 0.3) (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5.

(a) Principal component analysis (PCA) of infiltrating immune cell scores between the DN and the control group. (b) Immune cell infiltration in DN and control group. (c) Difference of immune cells between DN and control group. (d) Heat map of correlation between differential immune cells. (e) Correlation between key genes and differential immune cells. An asterisk (*) was usually leveraged to indicate that p < 0.05, two asterisks (**) represented p < 0.01, three asterisks (***) signified p < 0.001, and four asterisks (****) denoted p < 0.0001. The “ns” was leveraged to represent no significant difference.

Analysis of key gene expression in single cells

Single-cell annotated t-SNE maps of DN revealed that various cell types have similar gene expression patterns in the high-dimensional space and show tight clustering in the low-dimensional space. And there were significant gene expression differences between different cell types (Fig. 6a). In addition, VDAC1 may have a more stable expression level in different cell subpopulations, and the expression of PPIF was more homogeneous in all cell subpopulations. GPX1 showed significantly high expression in Leukocyte (LEUK), indicating that GPX1 could potentially play a significant role in LEUK (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

(a) Cell annotation tSNE diagram of GSE131882. (b) Bubble map of key gene expression in each cell subpopulation.

Characterization of clinical features

According to the findings, there was a substantial positive association between GPX1 and SCR and a significant negative correlation between GPX1 and GFR(Fig. 7a); PPIF showed a significant negative correlation with GFR and a significant positive correlation between PPIF and SCR (Fig. 7b); and VDAC1 showed a significant negative correlation with GFR (p < 0.05, |correlation (cor)| > 0.3) (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

(a–c) Correlation analysis of key genes with glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine.

Construction of molecular regulatory and drug prediction networks

The overlap of miRNAs targeted by the predictions from the miRWalk and TargetScan databases in a total of 62 in GPX1, PPIF predicted overlapping target 137 miRNAs and a total of 34 overlapping target miRNAs were predicted in VDAC1. Then, prediction of lncRNAs for intersecting miRNAs in the StarBase (https://rnasysu.com/encori/) database, with a total of 23 lncRNAs predicted. Finally, a network diagram of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA was constructed (such as RMRP -hsa-miR-766-5p-VDAC1) (Fig. 8a). To further develop a good strategy for the treatment of DN, a drug-gene network was constructed (Fig. 8b). GPX1 predicted 14 drugs, PPIF predicted 23 drugs, and VDAC1 predicted 21 drugs, for a total of 27 drugs. There were 6 drugs common to the two genes GPX1 and PPIF; 4 drugs common to the two genes GPX1 and VDAC1; 13 drugs common to the two genes PPIF and VDAC1; and 4 drugs common to the three genes drugs, namely menadione, glibenclamide, hydrogen peroxide, and METHYL METHANESULFONATE.

Fig. 8.

(a) lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network. (b) Network map of drugs and key genes.

Discussion

As a critical complication of diabetes mellitus (DM), the pathogenesis of DN is not clear at present, and its related treatment is limited to symptomatic treatment when renal function deteriorates, but no drugs have been developed for managing diabetic nephropathy8. To investigate the key genes linked to endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress in the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy, three key genes, GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1, were screened through bioinformatics analysis in this study.

An essential antioxidant enzyme in the body’s antioxidant defense system is glutathione peroxidase (GPX), Glutathione peroxidase-1(GPX1) is one of the most common. It is universally expressed in all tissues, and it can catalyze the REDOX reaction of glutathione with peroxides such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide radicals and so on. Reducing peroxides to water and oxygen to remove harmful organic hydroperoxides and protect cells from oxidative stress damage45,46. Current studies believe that oxidative stress is one of the main pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, and the onset and development of kidney disease is closely linked to the reduced expression of GPX147. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase F (PPIF) is a gene encoding mitochondrial matrix protein (cyclophilin D), and the protein cyclophilin D (CypD) is a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore48it is involved in regulating the death of neurons, fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes49. Relevant studies have shown that CypD may be involved in inflammatory signal transduction, tissue inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction. PPI has a complex role in diabetic nephropathy and is closely associated with disease occurrence50. Voltage-dependent anion channel-1 (VDAC1) is a multifunctional protein that forms channel proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane51regulating energy metabolism and material circulation in the cytoplasm and maintaining mitochondrial stability, while also playing a role in cell apoptosis52. VDAC1 is associated with various diseases. Relevant studies have confirmed its overexpression in Parkinson’s disease, cancer, autoimmune diseases such as lupus and so on52–56. Currently, there are also studies suggesting that genes related to VDAC1 is strongly linked to immune cell infiltration in diabetic nephropathy57. Our research results demonstrated that DN patients had down-regulated expression of three genes, which reconfirmed the previous studies and further supported the significant role of mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of DN. Based on these three important genes, we created a nomogram model. This findings indicated that this model could accurately identify the illness risk of DN patients and had a strong predictive power. According to these findings, GPX1, PPIF, and VDAC1 may be useful biomarkers for the early identification of diabetic nephropathy and may provide valuable information for clinicians to help formulate personalized treatment plans, thereby improving clinical patient management. In addition, the construction of the nomogram model provides a simple and effective tool for clinical practice, which is of great significance for the future monitoring and management of DN, promoting the development of research and clinical application in this field.

To comprehend the roles of these three key genes and their related pathways, the first three most significant pathways shared by the three key genes were obtained through enrichment analysis, including oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism, and ribosome.

The oxidative phosphorylation signaling pathway is involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, transferring electrons through a series of electron transfer reactions while producing reactive oxygen species required for homeostasis signaling58,59. Dysfunction of this pathway is strongly associated with many biological changes and the onset and development of diseases, such as obesity and aging, as well as pathology of all organ systems, including cardiovascular disease60,61. Oxidative phosphorylation has been shown to promote vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease patients62. Glutathione (GSH), a tripeptide composed of glutamic acid, cysteine, and glycine, acts as a vital antioxidant in the body, capable of neutralizing reactive oxygen species and playing a key role in preserving cellular redox balance63. Changes in the catabolism of GSH can lead to the occurrence and development of diseases. The pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson’s disease and neurodegenerative diseases is closely related to the reduction of GSH64while the increase of GSH and oxidized GSH is believed to be associated with the growth of cancer cells and the aging of the kidneys65,66. The ribosome is a large macromolecular ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex composed of ribonucleic acid (RNA) and ribosomal proteins (RP)67capable of translating the genetic code on mRNA into the amino acid sequence on polypeptide chains, and it is the main site of protein synthesis within cells (with the function of synthesizing cellular proteins), which is crucial for the growth and development of organisms68. When ribosome function is impaired, protein homeostasis is disrupted, which can lead to cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and other diseases69. These results suggest that GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1 may influence the development of diabetic nephropathy (DN) by participating in oxidative phosphorylation, glutathione metabolism and ribosome pathways. Although further verification is still needed, these findings help us understand how diabetic nephropathy develops from the perspective of pathogenesis and provide potential biomarkers and therapeutic directions for clinical practice. To improve the incidence and progression of diabetic nephropathy, future studies can investigate intervention options that target these important pathways.

In addition to oxidative stress, most scholars believe that inflammation is also one of the main pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy70. Therefore, in order to fully understand the dysregulated immune cells in DN, the two groups’ variations in immune infiltrating cells were compared using the Wilcoxon test and the CIBERSORT algorithm, then we obtain differential immune cells. These include T cell gamma delta, Macrophage M2 and activated Mast cell activated. Additionally, we also analysed how the expression of three key genes correlated with immune cells. The findings demonstrated a positively correlation between GPX1 and activated mast cells, M2 macrophages, and γδ T cells. PPIF had a negative correlation with γδ T cells, activated mast cells and M2 macrophages. VDAC1 was found to correlate positively with CD4 + naïve T cells and activated mast cells. Current research suggests that mast cells, M2-type macrophages, T cells and other inflammatory cells are involved in the chronic inflammation and interstitial fibrosis processes of various kidney diseases71. The above research supports our results and indicates that these three genes are related to mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic nephropathy. Whether targeting key genes for treatment can achieve anti-inflammatory effects by regulating immune cells still needs further exploration. We believe that this has broad research prospects in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy.

In order to explore the upstream non-coding RNAs associated with key genes, we used several multiple online databases to constructed a lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulation network, and predicted a total of 23 lncrnas. In the exploration of potential drugs targeting key gene therapy DN, as shown in the pharmacogene network diagram, there are four drugs predicted by these three key genes, namely menadione, glibenclamide, hydrogen peroxide, and Methyl Methanesulfonate.

Menadione is a polycyclic aromatic ketone, a naphthoquinone compound, a synthetic form of vitamin K3, which can be used as a superoxygen-generating agent to enter cells and produce reactive oxygen species72. Menadiquinone can inhibit lipogenesis73inhibit bacterial growth74,75and also can inhibit tumor development and progression76,77. According to relevant studies, it is speculated that menadiquinone can delay the deterioration of renal function and slow down the progression of diabetic nephropathy, so it can be used as a new direction for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Glibenclamide is an oral hypoglycemic agent that lowers blood sugar levels by promoting insulin release from the pancreas, is commonly used in the treatment of diabetes, and is also an anti-inflammatory factor78 that may reduce nerve damage79gouty arthritis, and heart attacks80. The use of glibenclamide can slow the damage of kidney function caused by hyperglycemia, and when combined with vitamins or calcitriol, it can prevent or reduce the damage of kidney tissue caused by diabetes81,82. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a key reactive oxygen species (ROS), is extensively involved in intracellular physiological processes and holds significant importance in the biomedical field83. Relevant studies have shown that it can act as the first messenger to transmit pro-inflammatory signals between cells, thereby participating in the body’s inflammatory response84. The occurrence of inflammation is one of the main causes of renal structural damage in diabetic nephropathy60. If anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to target the inflammatory response, renal function damage can be reduced, which is also a treatment strategy for diabetic nephropathy. METHYL METHANESULFONATE (MMS) is a kind of alkylating agent that can damage DNA, which mainly methylates nitrogen and oxygen atoms on purine bases, leading to DNA double strand break and point mutation. This property is of great significance in studying the mechanism of DNA damage, gene variation and the onset and development of related diseases. The results indicate that exploring the therapeutic strategy of DN from the perspective of DNA damage may be a new therapeutic direction.

In order to verify the expression of key genes in clinical specimens, we conducted RT-qPCR analysis, the results of RT-qPCR analysis were consistent with those obtained by previous analysis, indicating that the three key genes GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1 may provide reference value for the diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy.

Although this study has made important progress in DN research, there are still some shortcomings. Firstly, this study mainly relies on a single dataset of the GEO database. The sample size we adopted was limited, and only 10 blood samples were used, which made the results of the study possibly not fully reflect the diversity of DN patients. Further experimental verification through cell models or experimental animals is needed. Second, the analytical results of this study have not been verified in an independent large-scale sample, and there is a lack of further experimental and clinical validation support. In addition, although some key genes and network relationships have been screened by various analytical methods, the specific biological functions and mechanisms of these results still need to be further explored through subsequent functional experiments. Finally, this study failed to take into account the possible influence of environmental factors and other epigenetic factors, which may also significantly contribute to the onset and progression of DN. Therefore, future research should integrate large-scale samples from various sources to enhance the universality and reliability of research results, thereby ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the patient population with diabetic nephropathy (DN). Meanwhile, the biological functions of these genes can be further explored through animal models or cell experiments. On this basis, by using gene knockout or overexpression techniques and combining multi-omics data, the potential mechanisms by which these genes contribute to diabetic nephropathy can be deeply analyzed. This can provide a more solid theoretical basis for clinical application.

Conclusions

In this study, three key genes that might be related to DN, namely GPX1, PPIF and VDAC1, were successfully identified by using bioinformatics analysis and machine learning techniques. These three key genes may provide a new theoretical basis for the early detection and treatment of diabetic nephropathy, and may also serve as potential therapeutic targets to offer new research directions for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy, thereby promoting further research and clinical application in this field. However, we must admit that this study is limited. The results obtained from the analysis of a single dataset may have biases or overfitting, thereby misleading our research results. This study still needs to be further deepened.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the patients who contributed samples to this study, as well as the individuals and organizations that provided valuable advice and assistance throughout the research. Their dedication and cooperation were instrumental to the success of this study.

Author contributions

LT was responsible for the conception and design of the research, as well as the completion of the first draft and revision of the manuscript. LL was responsible for collecting data from the database and organizing it. SZJ was responsible for data analysis and constructing relevant data models. ZHJ was responsible for software development and proofreading the manuscript. HGY was responsible for validation and visualization. TZ was responsible for creating charts and figures. CD was responsible for sample collection. LJ supervised the entire project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Teaching Quality Project (No.: 2022JXD209), the “Famous Doctors” special program for high-level talents in Yunnan Province (No.: RLMY20200022), Scientific Research Fund of Education Department of Yunnan Province (No.: 2022J0269), Postgraduate Innovation fund of Kunming Medical University (No.: 2022S221), Postgraduate Innovation fund of Kunming Medical University (No.: 2023S260), and Scientific Research Fund project of Education Department of Yunnan Province (No.: 2025J0781).

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GEO repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), The Mitochondrial Protein Reference Set 3.0 (MitoCarta3.0) repository (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta), and The molecular signatures database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All participants gave informed consent. We ensure that all experimental methods are carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Matoba, K. et al. Unraveling the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 3393 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guariguata, L. et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.103, 137–149 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan, X. et al. Mitophagy regulates kidney diseases. Kidney Dis. (Basel). 10, 573–587 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elwakiel, A., Mathew, A. & Isermann, B. The role of Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria-associated membranes in diabetic kidney disease. Cardiovascular. Res.119, 2875–2883 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung, P. H., Hsu, Y. C., Chen, T. H. & Lin, C. L. Recent advances in diabetic kidney diseases: from kidney injury to kidney fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 11857 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psyllaki, A. & Tziomalos, K. New perspectives in the management of diabetic nephropathy. World J. Diabetes. 15, 1086–1090 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuen, B. L. et al. Estimated lifetime cardiovascular, kidney, and mortality benefits of combination treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal MRA compared with conventional care in patients with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. Circulation149, 450–462 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habiba, U. E., Khan, N., Greene, D. L., Shamim, S. & Umer, A. The therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells in diabetic kidney disease. J. Mol. Med. (Berl). 102, 537–570 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhargava, P. & Schnellmann, R. G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.13, 629–646 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, X., Agborbesong, E. & Li, X. The role of mitochondria in acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease and its therapeutic potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 11253 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachdeva, K. et al. Environmental exposures and asthma development: autophagy, mitophagy, and cellular senescence. Front. Immunol.10, 2787 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opazo-Ríos, L. et al. Lipotoxicity and diabetic nephropathy: novel mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 2632 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi, Z. & Chen, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. Autophagy: Biology Diseases: Basic. Science 167–177 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhang, R., Bian, C., Gao, J. & Ren, H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic kidney disease: adaptation and apoptosis after three UPR pathways. Apoptosis28, 977–996 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, M. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis: A potential target for diabetic nephropathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1182848 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min, S., Lee, B. & Yoon, S. Deep learning in bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform.18, 851–869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raslan, M. A., Raslan, S. A., Shehata, E. M. & Mahmoud, A. S. Sabri, N. A. Advances in the applications of bioinformatics and chemoinformatics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 16, 1050 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geng, X. et al. Identification of key genes and pathways in diabetic nephropathy by bioinformatics analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 10, 972–984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan, P., Ke, B. & Fang, X. Bioinformatics reveals the pathophysiological relationship between diabetic nephropathy and periodontitis in the context of aging. Heliyon10, e24872 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woroniecka, K. I. et al. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes60, 2354–2369 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, B. et al. Comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial dysfunction and necroptosis in intracranial aneurysms from the perspective of predictive, preventative, and personalized medicine. Apoptosis28, 1452–1468 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su, J. et al. Identification of Endoplasmic reticulum stress-related biomarkers of diabetes nephropathy based on bioinformatics and machine learning. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1206154 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robles-Jimenez, L. E. et al. Worldwide traceability of antibiotic residues from livestock in wastewater and soil: A systematic review. Anim. (Basel). 12, 60 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustavsson, E. K., Zhang, D., Reynolds, R. H., Garcia-Ruiz, S. & Ryten, M. ggtranscript: An R package for the visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using ggplot2. Bioinformatics 38, 3844–3846 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics32, 2847–2849 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao, W., Ding, J., Li, Y., Huang, R. & Wang, B. Inhibition of cell survival and invasion by Tanshinone IIA via FTH1: A key therapeutic target and biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med.24, 521 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (Camb). 2, 100141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res.53, D672–D677 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.28, 1947–1951 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. K. E. G. G. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13, 2498–2504 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarringhalam, K., Degras, D., Brockel, C. & Ziemek, D. Robust phenotype prediction from gene expression data using differential shrinkage of co-regulated genes. Sci. Rep.8, 1237 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan, S. et al. Identifying potential targets for preventing cancer progression through the PLA2G1B Recombinant protein using bioinformatics and machine learning methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.276, 133918 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou, H., Xin, Y. & Li, S. A diabetes prediction model based on Boruta feature selection and ensemble learning. BMC Bioinform.24, 224 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engebretsen, S. & Bohlin, J. Statistical predictions with Glmnet. Clin. Epigenetics. 11, 123 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feretzakis, G. et al. IOS Press,. Using machine learning for predicting the hospitalization of emergency department patients. in Advances in Informatics, Management and Technology in Healthcare 405–408 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform.12, 77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu, J. et al. A nomogram for predicting prognosis of patients with cervical cerclage. Heliyon9, e21147 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Mak.26, 565–574 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, L. et al. Cuproptosis related genes associated with Jab1 shapes tumor microenvironment and Pharmacological profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Front. Immunol.13, 989286 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merotto, L., Sturm, G., Dietrich, A., List, M. & Finotello, F. Making mouse transcriptomics Deconvolution accessible with immunedeconv. Bioinform Adv.4, vbae032 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong, T., Jiang, Y., Saldivia, L. E. & Agard, C. Using Sankey diagrams to visualize drag and drop action sequences in technology-enhanced items. Behav. Res.54, 117–132 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai, Y., Deng, L. & Yao, J. Analysis and identification of ferroptosis-related diagnostic markers in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Med56, 2397572 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Liu, C., Yan, Q., Gao, C., Lin, L. & Wei, J. Study on antioxidant effect of Recombinant glutathione peroxidase 1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.170, 503–513 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Handy, D. E. & Loscalzo, J. The role of glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease. Free Radic Biol. Med.188, 146–161 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begum, F. & Lakshmanan, K. Association of mnsod, CAT, and GPx1 gene polymorphism with risk of diabetic nephropathy in South Indian patients: A case–control study. Biochemical Genetics 1–16 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Protasoni, M. et al. Cyclophilin D plays a critical role in the survival of senescent cells. EMBO J.43, 5972–6000 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, X., Hogan, S. P., Molkentin, J. D. & Zimmermann, N. Cyclophilin D regulates necrosis, but not apoptosis, of murine eosinophils. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.310, G609–G617 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jang, H. S., Noh, M. R., Ha, L., Kim, J. & Padanilam, B. J. Proximal tubule Cyclophilin D mediates kidney fibrogenesis in obstructive nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol.321, F431–F442 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCommis, K. S. & Baines, C. P. The role of VDAC in cell death: friend or foe? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1818, 1444–1450 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ham, S. J. et al. Decision between mitophagy and apoptosis by parkin via VDAC1 ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 4281–4291 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allon, I. et al. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 expression in oral malignant and premalignant lesions. Diagnostics (Basel). 13, 1225 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arif, T., Vasilkovsky, L., Refaely, Y. & Konson, A. Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Silencing VDAC1 expression by SiRNA inhibits cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth in vivo. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 8, 493 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shoshan-Barmatz, V., Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A. & Verma, A. VDAC1 at the intersection of cell metabolism, apoptosis, and diseases. Biomolecules10, 1485 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yan, J., Liu, W., Feng, F. & Chen, L. VDAC oligomer pores: A mechanism in disease triggered by MtDNA release. Cell. Biol. Int.44, 2178–2181 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin, J. et al. Identification and validation of voltage-dependent anion channel 1‐related genes and immune cell infiltration in diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 15, 87–105 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nolfi-Donegan, D., Braganza, A. & Shiva, S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol.37, 101674 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wculek, S. K. et al. Oxidative phosphorylation selectively orchestrates tissue macrophage homeostasis. Immunity56, 516–530e9 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhanabalan, K., Huisamen, B. & Lochner, A. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and mitophagy in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion: effects of chloroquine. Cardiovasc. J. Afr.31, 169–179 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Čolak, E. & Pap, D. The role of oxidative stress in the development of obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders. J. Med. Biochem.40, 1–9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi, J. et al. Oxidative phosphorylation promotes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Cell. Death Dis.13, 229 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guan, X. Glutathione and glutathione disulfide – their biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Med. Chem. Res.32, 1972–1994 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu, G., Lupton, J. R., Turner, N. D., Fang, Y. Z. & Yang, S. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J. Nutr.134, 489–492 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiao, Y. & Meierhofer, D. Glutathione metabolism in renal cell carcinoma progression and implications for therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 3672 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahn, E. et al. Glutathione is an aging-related metabolic signature in the mouse kidney. Aging (Albany NY). 13, 21009–21028 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baßler, J. & Hurt, E. Eukaryotic ribosome assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem.88, 281–306 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindahl, L. Ribosome structural changes dynamically affect ribosome function. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 11186 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGirr, T., Onar, O. & Jafarnejad, S. M. Dysregulated ribosome quality control in human diseases. FEBS J.292, 936–959 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jin, Q. et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy: role of polyphenols. Front. Immunol.14, 1185317 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu, Z. et al. Inflammation-activated CXCL16 pathway contributes to tubulointerstitial injury in mouse diabetic nephropathy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39, 1022–1033 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Monteiro, J. P. et al. A biophysical approach to menadione membrane interactions: relevance for menadione-induced mitochondria dysfunction and related deleterious/therapeutic effects. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr.1828, 1899–1908 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Funk, M. I., Conde, M. A., Piwien-Pilipuk, G. & Uranga, R. M. Novel antiadipogenic effect of menadione in 3T3-L1 cells. Chemico-Biol. Interact.343, 109491 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee, M. H. et al. Inhibitory effects of menadione on helicobacter pylori growth and helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation via NF-κB Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 1169 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schlievert, P. M. et al. Menaquinone analogs inhibit growth of bacterial pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.57, 5432–5437 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kishore, C., Sundaram, S. & Karunagaran, D. Vitamin K3 (menadione) suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal-transition and Wnt signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Chemico-Biol. Interact.309, 108725 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Teixeira, J. et al. Disruption of mitochondrial function as mechanism for anti-cancer activity of a novel mitochondriotropic menadione derivative. Toxicology393, 123–139 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carvalho, A. M. et al. Glyburide, a NLRP3 inhibitor, decreases inflammatory response and is a candidate to reduce pathology in leishmania Braziliensis infection. J. Invest. Dermatol.140, 246–249e2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu, F., Shen, G., Su, Z., He, Z. & Yuan, L. Glibenclamide ameliorates the disrupted blood–brain barrier in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage by inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Brain Behav.9, e01254 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cao, N. et al. Glibenclamide alleviates β adrenergic receptor activation-induced cardiac inflammation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43, 1243–1250 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.ElKhooly, I. A., El-Bassossy, H. M., Mohammed, H. O., Atwa, A. M. & Hassan, N. A. Vitamin B1 and calcitriol enhance Glibenclamide suppression of diabetic nephropathy: role of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB/TNF-α/Nrf2/α-SMA trajectories. Life Sci.357, 123046 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atia, T. et al. Vitamin D supplementation could enhance the effectiveness of Glibenclamide in treating diabetes and preventing diabetic nephropathy: A biochemical, histological and immunohistochemical study. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med.27, 2515690X221116403 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang, K., Yao, T., Xue, J., Guo, Y. & Xu, X. A novel fluorescent probe for the detection of hydrogen peroxide. Biosens. (Basel). 13, 658 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gunawardena, D., Raju, R. & Münch, G. Hydrogen peroxide mediates pro-inflammatory cell-to-cell signaling: A new therapeutic target for inflammation? Neural Regen Res.14, 1430–1437 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GEO repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), The Mitochondrial Protein Reference Set 3.0 (MitoCarta3.0) repository (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta), and The molecular signatures database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp).