Abstract

Viloxazine and dextroamphetamine as newly approved drugs for the medical treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in recent years give new options for the treating of related disorders, including anxiety, and depression. In our research, we conducted an assessment of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with the utilization of these two medications, as documented in the database. By analyzing the adverse drug reaction profiles and combining them with relevant reviews, we aim to help select the drug with the least risk to meet the specific needs of different patients. A retrospective descriptive analysis method was used in this study. The study classified two ADHD medications and extracted adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports for these medications from the World Health Organization-VigiAccess database. Data collected included patient demographic characteristics such as gender and age group, as well as geographic distribution based on global ADR reports. We compared the similarities and differences between the ADRs of the two drugs by calculating the proportion of ADRs reported for each drug. Finally, we also compared the most common general disorders and administration site conditions for various adverse effects. VigiAccess reported a total of 5394 adverse events (AEs) related to these two drugs. The most commonly reported age group was between 18 and 44 years and the three most common types of AEs were: general disease and site of administration conditions (2,548 cases, 20.5%), psychiatric disorders (2,012 cases, 16.1%) and neurologic disorders (1,822 cases, 14.6%). Dextroamphetamine had a significantly higher rate of reported adverse reactions in general disorders and administration site conditions compared to viloxazine. Beyond that there are other differences that exist. Using real-world data from WHO-VigiAccess and FAERS, we identified existing potential adverse reactions associated with viloxazine and dextroamphetamine, providing valuable insights for clinical reference. Although the study benefits from database utilization, its limitation lies in the spontaneous reporting system. Accurate drug safety evaluation requires future enhancements.

Keywords: VigiAccess of the WHO, Spontaneous reporting, Pharmacovigilance, Adverse drug reaction, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Subject terms: Drug delivery, Drug safety

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by developmental inappropriateness and impairments of inattention, motor hyperactivity, and impulsivity, with difficulties usually persisting into adulthood1. It is a diagnostic category in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) and the most recent DSM-51. DSM-5 has updated the diagnostic criteria to include three subtypes: combined presentation (meeting both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity criteria in the past six months), predominantly inattentive presentation (meeting only inattention criteria), and predominantly hyperactive/impulsive presentation (meeting only hyperactivity/impulsivity criteria). Symptoms are categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on their impact2. ADHD usually manifests itself in childhood and can persist into adulthood. Its diagnosis requires a comprehensive process that includes a risk assessment, consideration of symptoms that may mimic those of other disorders, a detailed medical history, physical examination, and identification of comorbidities. Treatment varies in early, middle childhood and adolescence and includes behavioral interventions and medications3.

Currently available drugs have been developed in both stimulant (methylphenidate, amphetamine) and non-stimulant (atomoxetine, guanfacine, clonidine) categories4–6. Stimulant medications such as methylphenidate and amphetamine are commonly prescribed as the primary treatment option for individuals diagnosed with ADHD7. Stimulant medications for psychological conditions come in two varieties: short-acting and long-acting options. The long-acting category encompasses an array of extended-release formulations that may consist of a blend of quick-acting and sustained-release beads. Additionally, it includes the prodrug lisdexamfetamine dimesylate and methylphenidate in an osmotic-release oral system8. All stimulants are sympathomimetic agents with similar chemical composition and physiological effects. They work by stimulating the central nervous system, resulting in elevated levels of norepinephrine and dopamine (DA) in the prefrontal cortex. In addition, they activate adrenergic receptors in the heart and blood vessels, resulting in a mild increase in blood pressure (BP) and resting heart rate (RHR)9, especially with amphetamines. However, no significant serious cardiovascular issues have been reported. In neuropsychiatry, long-term methylphenidate use generally doesn’t cause serious problems, although an increased risk of psychotic episodes was found among amphetamine users. Some gastrointestinal side effects like reduced appetite and stomach pain were reported, but results on ocular abnormalities and growth effects are inconclusive10.

Qelbree, the trademark name for viloxazine, was first synthesized in 1974 and used as an antidepressant in Europe during the 1970 s, with its compound patent being US 3,712,89011. In the 21 st century, its potential for treating ADHD was rediscovered and it was redeveloped by Supernus Pharmaceuticals. On April 2, 2021, the FDA approved Qelbree (viloxazine) extended-release capsules for ADHD in children aged 6–17, marking the first non-stimulant ADHD drug approved by the FDA in a decade. In April 2022, the FDA further approved Qelbree for adult ADHD. As the first new non-stimulant ADHD drug approved by the FDA in recent years12, viloxazine acts as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor11. Its mechanism of action involves increasing serotonin levels in the prefrontal cortex, moderately inhibiting the norepinephrine transporter, and inducing moderate activity in the dopaminergic andnoradrenergic systems, which underlie its clinical efficacy13. Similarly, dextroamphetamine (right-amphetamine) has a long history of use. In 1937, the American company Smith, Kline, and French began synthesizing and promoting dextroamphetamine under the brand name Dexedrine for narcolepsy and ADHD. On March 22, 2022, Xelstrym, a transdermal patch formulation of dextroamphetamine, was FDA-approved, becoming the first and only transdermal patch for ADHD in individuals aged 6 and older14,15. In clinical trials involving young ADHD patients, the patch achieved its primary and secondary efficacy goals. In a previous study, participants applied the d-ATS patch for a duration of nine hours and experienced noticeable enhancements in their Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M. Flynn, and Pelham (SKAMP) scale scores, which assess ADHD symptoms. These improvements were evident two hours’ post-application and continued to be observed up to twelve hours after the patch was worn. This experiment also illustrates that people with ADHD may need symptomatic treatment for different times of the day16.

Generally, pre-market drug trials are very rigorous, but for these two drugs, especially dextroamphetamine, the research data collected are not sufficient, which suggests that we are not able to fully confirm the safety of the medicines from the pre-market clinical trial data. In addition, given the recent market introduction of these two medications, there is a heightened necessity for safety assessments that leverage extensive real-world data. Consequently, it is crucial to delve deeper into the adverse drug reactions (ADRs) linked to ADHD treatments by analyzing spontaneous reports within pharmacovigilance databases. Notably, for these newly launched drugs, there exists a research gap as no comparative studies have yet been conducted to discern the commonalities and disparities in the ADRs they may induce.

Despite certain constraints, spontaneous reporting systems are a precious asset for gathering actual data on medication and vaccine safety, evaluating therapeutic approaches, and understanding the mechanisms behind adverse drug reactions (ADRs)17. Since their establishment in the 1960 s, these systems have been central to pharmacovigilance, primarily for identifying previously unknown ADRs early on. Moreover, they are also instrumental in uncovering new facets of the relationship between medications and known ADRs18. The Uppsala Monitoring Center (UMC), under the WHO’s International Drug Monitoring Program (PIDM), is responsible for aggregating global safety data. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) is an FDA-administered database that collects reports of adverse events, medication errors, and product quality complaints for drugs and biologics to support post-market safety monitoring.

We queried the VigiAccess and FAERS database for adverse reactions to the two actives and conducted a descriptive study comparing the rates of reported adverse events caused by the two actives.

Methods

Drug sample

Viloxazine and dextroamphetamine have been used in Europe since the 20th century. However, the two ADHD drugs, Qelbree® (viloxazine) and Xelstrym® (dextroamphetamine), have been on the market for less than five years and are not available in China. In 2021, the FDA approved Qelbree, a viloxazine extended-release capsule, for treating ADHD in children aged 6–17. This made it the first non-stimulant ADHD drug approved by the FDA in a decade12. The next year, the FDA approved viloxazine for adult ADHD. Viloxazine works by modulating 5-HT receptors, increasing 5-HT concentration in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), activating 5-HT₂C receptors, blocking 5-HT₂B receptors, inhibiting NE reuptake, and boosting NE and DA levels to improve hyperactivity and attention in ADHD children19. As shown in Table 1, the two drugs differ in their therapeutic scope.

Table 1.

Basic information of two ADHD drugs.

| Drug name | Brand name | Main conditions | First Marketing time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viloxazine | Qelbree | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Anxiety, Autism spectrum disorder | 2021 (Qelbree) |

| Dextroamphetamine | Xelstrym | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Narcolepsy, Depression | 2022 (Xelstrym) |

Data sources

A search was conducted in WHO-VigiAccess on 31 August 2024 for all reported adverse events following the introduction of ADHD medications, and all data collected for both medications were identified by brand name. The data included gender, age group, continent and year of reporting. WHO-VigiAccess can be accessed at https://www.vigiaccess.org. Notably, although Qelbree and Xelstrym have been on the market for only the past five years, their active ingredients—viloxazine and dextroamphetamine—have been in use since the latter half of the 20th century. As a result, the WHO’s VigiAccess database contains initial records of viloxazine from 1976 and dextroamphetamine from 1969. On November 4, 2024, we extracted reports of viloxazine and dextroamphetamine from the FAERS database. Each FAERS report contains administrative and demographic information (including PRIMARYID), information on the report source, patient outcomes, reaction details from case reports, and drug information from case reports. For more details, please refer to the FAERS database: https://fis.fda.gov/extensions/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html.

Launched by the WHO in 2015, VigiAccess allows the public to access VigiBase data. VigiBase, WHO’s global ADR database, comprises individual case reports from PIDM member states. Since the PIDM’s establishment in 1968, VigiAccess can include pre-2015 data thanks to decades of PIDM-submitted ADR reports. Subsequent definitions of data classification are based on the System Organ Classification (SOC) and Preferred Terms (PTs) in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). MedDRA uses reporting terms from several dictionary reports, including the World Health Organization Adverse Reaction Terminology (WHO-ART) et al.20. Therefore, by searching the records of two medications for ADHD and based on MedDRA SOC and PT levels, we identified all individual AEs recorded to characterize the toxicity profile. According to SOC classification, dextroamphetamine had 27 entries and viloxazine had 26 entries, and we selected all entries for analysis. In this study, we focused on PT, the level of information used in the FAERS database and VigiBase database publicly accessible through WHO-VigiAccess. FAERS is a spontaneous ADR reporting database. It contains AE reports, medication errors, and product quality complaints submitted to the FDA. In this study, AE, product quality complaints, and medication errors from reports were encoded using MedDRA terminology. This encoding facilitates signal detection to quantify the association between drugs and reported AEs21.

We used outcome codes to classify outcomes into three severity categories: death, hospitalization, and major events, including life-threatening events, disabilities, and congenital anomalies to examine the results of detected safety signals.

Disproportionality analysis

We utilized two disproportionality analysis methods to identify unusual patterns of adverse event (AE) reporting: The Reporting Odds Ratio (ROR)22 and the Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR)23. Both ROR and PRR calculations are founded on the concept of odds imbalance, a prevalent technique in AE signal detection24.

The ROR is determined to assess the disparity in the likelihood of reporting an AE for a particular medication relative to other medications. The ROR calculation is represented by the following formula:

|

The formula involves categorizing data into four segments: (a) reports linking a particular medication to a specific adverse event (AE), (b) reports of the same medication associated with various other AEs, (c) reports of different medications connected to the same AE, and (d) reports of various medications related to different AEs. For the calculation of the Reporting Odds Ratio (ROR) to be statistically sound, there must be at least five instances of the specific drug and AE combination (a ≥ 5).

The Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR) is an additional metric employed to evaluate the imbalance in AE reporting. Its computation is given by the formula:

|

Like ROR, the PRR also necessitates a minimum of five cases for the specific drug and AE pair (a ≥ 5) to be deemed reliable.

A ROR exceeding 2 (ROR > 2) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a lower bound surpassing 1 (the lower limit of the 95% CI for ROR > 1) are indicators of a significant disproportionality signal, potentially signaling a safety issue. These thresholds help confirm that the observed imbalance is not a result of chance.

By incorporating ROR and PRR in our assessment, we can methodically appraise the reported imbalances concerning general disorders and administration site conditions associated with two ADHD medications. The findings from this analysis bolster pharmacovigilance initiative focused on improving the safety of pharmaceuticals.

Analysis of statistics

This research employed a retrospective quantitative approach to analyze the adverse reactions associated with two medications. Utilizing Excel, the study conducted a descriptive analysis of individuals experiencing adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The ADR reporting rate for each medication was determined by dividing the count of distinct ADR symptoms by the overall number of ADR reports. The most prevalent ADRs for each drug were identified as the 20 most frequently reported symptoms. The study calculated and compared the ADR symptom reporting rates for each drug in a descriptive manner. At the end of the analysis, the descriptive variables were categorized into frequency counts and percentages and presented in a table. Data from VigiAccess was analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and GraphPad Prism 10 for statistics and graphics. SAS 9.4 was used for FAERS data analysis, as it’s an FDA-recommended tool for FAERS mining. The analysis involved descriptive statistics and inter-group comparisons, with results presented via bar charts, line graphs, and forest plots for clarity.

Results

Description of the cases studied

The initial reports of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) related to viloxazine in Qelbree and dextroamphetamine in Xelstrym were logged in the WHO’s VigiAccess database in 1976 and 1969, respectively. As of 2024, the organization has accumulated a total of 5,394 ADR reports—959 for viloxazine and 4,435 for dextroamphetamine. Out of the 5,394 reports, aside from 399 instances shown in Table 2 where the patient’s sex was not specified, women (2,772) experienced ADRs at a slightly higher rate than men (2,223), resulting in a female-to-male ratio of 1.24:1, indicating a minor difference. When age information was available, the age groups most frequently reported were between 18 and 44 years old. The majority of these adverse events were reported from the Americas, accounting for 56.43% of the cases. Table 2 provides a breakdown of the reporting years for each of the two ADHD medications under investigation.

Table 2.

ADR reporting characteristics of two ADHD medications.

| Characteristics, n(%) | viloxazine | dextroamphetamine |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 959(100) | 4,435(100) |

| Age Group | ||

| 0–27 days | 1(0.1) | 1(0.0) |

| 28 days to 23 months | - | 9(0.2) |

| 2–11 years | 120(12.5) | 317(7.1) |

| 12–17 years | 94(9.8) | 252(5.7) |

| 18–44 years | 178(18.6) | 1,384(31.2) |

| 45–64 years | 145(15.1) | 581(13.1) |

| 65–74 years | 80(8.3) | 97(2.2) |

| ≥ 75 years | 134(14.0) | 23(0.5) |

| Unknown | 207(21.6) | 1,771(39.9) |

| Continent | ||

| Americas | 521(54.3) | 2,523(56.9) |

| Asia | 1(0.1) | 2(0.0) |

| Europe | 437(45.6) | 1,740(39.2) |

| Oceania | - | 170(3.8) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 471(49.1) | 2,301(51.9) |

| Male | 402(41.9) | 1,821(41.1) |

| Unknown | 86(9.0) | 313(7.1) |

Distribution of SOCs of two ADHD medications

Table 3 lists the incidence of adverse reactions in the system organ classes (SOCs) associated with two ADHD medications, with 26 cases linked to viloxazine and 27 to dextroamphetamine. The report shows that viloxazine has a significantly higher incidence of adverse reactions than dextroamphetamine in the SOCs for blood and lymphatic system disorders, ear and labyrinth disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, hepatobiliary disorders, investigations, nervous system disorders, renal and urinary disorders, and skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders. Conversely, dextroamphetamine has significantly higher rates than viloxazine in cardiac disorders, general disorders and administration site conditions, injury poisoning and procedural complications, musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, and product issues. Additionally, dextroamphetamine has a unique SOC for neoplasms (benign, malignant, and unspecified, including cysts and polyps).

Table 3.

Number and reporting rates of ADRs for SOCs for two ADHD medications.

| System organ classes | viloxazine (N = 1,633) |

dextroamphetamine (N = 10,810) |

|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 28(1.7%) | 29(0.3%) |

| Cardiac disorders | 36(2.2%) | 472(4.4%) |

| Congenital familial and genetic disorders | 2(0.1%) | 12(0.1%) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 19(1.2%) | 62(0.6%) |

| Endocrine disorders | 2(0.1%) | 14(0.1%) |

| Eye disorders | 23(1.4%) | 226(2.1%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 205(12.6%) | 771(7.1%) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 205(12.6%) | 2,343(21.7%) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 53(3.2%) | 22(0.2%) |

| Immune system disorders | 4(0.2%) | 57(0.5%) |

| Infections and infestations | 4(0.2%) | 68(0.6%) |

| Injury poisoning and procedural complications | 75(4.6%) | 620(5.7%) |

| Investigations | 84(5.1%) | 406(3.8%) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 38(2.3%) | 254(2.3%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 25(1.5%) | 330(3.1%) |

| Neoplasms benign malignant and unspecified incl cysts and polyps | - | 23(0.2%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 306(18.7%) | 1,516(14.0%) |

| Pregnancy puerperium and perinatal conditions | 2(0.1%) | 15(0.1%) |

| Product issues | 8(0.5%) | 613(5.7%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 278(17.0%) | 1734(16.0%) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 24(1.5%) | 81(0.7%) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 20(1.2%) | 106(1.0%) |

| Respiratory thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 18(1.1%) | 197(1.8%) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 98(6.0%) | 438(4.1%) |

| Social circumstances | 19(1.2%) | 115(1.1%) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 23(1.4%) | 41(0.4%) |

| Vascular disorders | 34(2.1%) | 245(2.3%) |

In the SOC report, the proportion of ADRs for dextroamphetamine that exceeded 10% was found in three categories: general disorders and administration site conditions, nervous system disorders, and psychiatric disorders. Viloxazine also had gastrointestinal disorders in addition to the above three.

Most common ADRs of two ADHD drugs

Table 4 outlines the 20 most frequently documented adverse drug reactions (ADRs) for two ADHD medications, utilizing preferred terms classified under respective System Organ Classes (SOCs). Shared ADRs between the two drugs encompassed nausea, headache, somnolence, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, dizziness, agitation, irritability, drug ineffective and decreased appetite. dextroamphetamine had a markedly higher incidence of reports concerning the drug ineffective in comparison to its counterpart. Notably, viloxazine led with the highest number of nausea-related ADR reports. The majority of the top 20 ADRs were generally mild and self-resolving. Nonetheless, certain events stood out as being of particular interest, including seizure, hepatitis, alanine aminotransferase increased, and some drugs use problems (drug ineffective, therapeutic response unexpected, and product substitution issue).

Table 4.

Top 20 ADRs of ADHD drugs.

| Viloxazine (N = 2,199) |

Dextroamphetamine (N = 15,572) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADR | Report rate% | ADR | Report rate% | |

| Nausea | 4.27 | Drug ineffective | 4.84 | |

| Vomiting | 3.96 | Therapeutic response unexpected | 4.3 | |

| Headache | 3.64 | Headache | 3.08 | |

| Somnolence | 2.91 | Depressed mood | 1.96 | |

| Fatigue | 2.46 | Fatigue | 1.86 | |

| Insomnia | 2.27 | Product substitution issue | 1.75 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 2 | Insomnia | 1.74 | |

| Migraine | 1.86 | Nausea | 1.68 | |

| Confusional state | 1.68 | Palpitations | 1.67 | |

| Seizure | 1.55 | Disturbance in attention | 1.64 | |

| Hepatitis | 1.46 | Anxiety | 1.43 | |

| Anxiety | 1.27 | Dizziness | 1.35 | |

| Withdrawal syndrome | 1.05 | Somnolence | 1.16 | |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1.05 | Decreased appetite | 1.15 | |

| Dizziness | 1.05 | Irritability | 1.13 | |

| Rash | 1.05 | Feeling abnormal | 1.03 | |

| Agitation | 1 | Restlessness | 0.94 | |

| Irritability | 1 | Dry mouth | 0.9 | |

| Drug ineffective | 0.95 | Aggression | 0.83 | |

| Decreased appetite | 0.95 | Agitation | 0.8 | |

Serious AEs of two ADHD medications

Utilizing the WHO-VigiAccess database, we are able to identify significant adverse events associated with ADHD medications. This includes events that are life-threatening events, disability, and birth defects. The recorded rates of these serious adverse reactions for viloxazine and dextroamphetamine are 0.23% and 0.29%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The outcomes detailing ADR events linked to ADHD medications are categorized at the preferred terms level, which encompass critical incidents such as life-threatening conditions, disabilities, and birth defects.

Similarities and differences in common ADRs to two ADHD medications

Upon examining the top 20 ADRs reported for each ADHD medication within the SOCs, a total of 99 identical signals were identified at the PT level for ADHD-related ADRs. These common signals have been compiled and organized in Table 5 for clarity and further analysis. Among the SOCs, the categories with the highest number of adverse signals were those related to nervous system disorders and psychiatric disorders. The top five reports of nervous system disorders were dystonia, tremor, dizziness, seizure, somnolence. The top five reports of psychiatric disorders were anger, completed suicide, suicidal ideation, mood swings, agitation. The third was general disorders and administration site conditions, and the top five reports were feeling abnormal, adverse event, pain, withdrawal syndrome, drug interaction.

Table 5.

Similarities in common ADRs to two ADHD drugs.

| System organ classes | ADRs | Signal N |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac disorders | Extrasystoles, Palpitations, Cardiac arrest, Tachycardia, Cardiac disorder | 5 |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | Tinnitus, Hyperacusis, Vertigo | 3 |

| Eye disorders | Vision blurred, Mydriasis, Photophobia, Visual impairment | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Nausea, Abdominal pain, Dysphagia, Diarrhea, Dyspepsia, Gastrointestinal disorder, Dry mouth, Vomiting, Constipation, Abdominal distension, Abdominal pain upper, Retching | 11 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Feeling abnormal, Adverse event, Pain, Withdrawal syndrome, Drug interaction, Condition aggravated, Malaise, Drug ineffective, Fatigue, Asthenia, Crying, Chest pain | 12 |

| Immune system disorders | Hypersensitivity | 1 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | Overdose, Wrong technique in product usage process, Product dose omission issue, Product use in unapproved indication, Off label use, Fall, Product use issue | 7 |

| Investigations | Blood pressure increased, Alanine aminotransferase increased, Weight decreased, Aspartate aminotransferase increased, Heart rate increased | 5 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | Decreased appetite, Dehydration | 2 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Myalgia, Muscle spasms, Muscle twitching, Rhabdomyolysis, Musculoskeletal stiffness, Back pain | 6 |

| Nervous system disorders | Dystonia, Tremor, Dizziness, Seizure, Somnolence, Psychomotor hyperactivity, Headache, Loss of consciousness, Speech disorder, Paraesthesia, Disturbance in attention, Migraine, Lethargy | 13 |

| Product issues | Product physical issue, Product availability issue | 2 |

| Psychiatric disorders | Anger, Completed suicide, Suicidal ideation, Mood swings, Agitation, Insomnia, Anxiety, Panic attack, Aggression, Depression, Sleep disorder, Irritability, Confusional state | 13 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | Urinary incontinence | 1 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | Erectile dysfunction | 1 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | Dyspnoea | 1 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | Rash erythematous,Erythema,Pruritus,Rash,Hyperhidrosis,Eczema,Urticaria | 7 |

| Social circumstances | Loss of personal independence in daily activities, Impaired work ability | 2 |

| Vascular disorders | Raynaud’s phenomenon, Hypertension, Hypotension | 3 |

Compare the top 20 adverse reactions reported for each ADHD medication in the SOCs, and it is found that the two ADHD medications have varying incidence rates of ADRs in 17 areas, including cardiac disorders, ocular diseases, and gastrointestinal disorders (Table 6). The number of distinctive symptoms for viloxazine and dextroamphetamine was 88 and 96, respectively.

Table 6.

Differences in common ADRs to two ADHD drugs.

| System organ classes | Viloxazine | Dextroamphetamine |

|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders |

Thrombocytopenia, Neutropenia, Bone marrow failure, Leukopenia, Eosinophilia, Agranulocytosis, Lymphadenopathy |

|

| Cardiac disorders | Supraventricular tachycardia |

Coronary artery dissection, Cardiomyopathy, Cardio-respiratory arrest, Angina pectoris, Myocardial infarction, Bradycardia, Arrhythmia |

| Endocrine disorders | Hyperprolactinemia | |

| Eye disorders | Blindness transient, Eye movement disorder |

Ocular discomfort, Eye pain, Diplopia, Dry eye |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Gastroesophageal reflux disease | Swollen tongue, Flatulence, Coeliac disease, Glossodynia, Abdominal discomfort, Colitis ischaemic, Stomatitis |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Chills, Feeling hot, Pyrexia, Drug effect less than expected, Drug withdrawal syndrome, Therapy non-responder, Therapeutic product effect incomplete, Adverse drug reaction | Rebound effect, Therapeutic response decreased, Therapeutic response unexpected, Application site pain, Feeling jittery, Therapeutic product effect decreased, Unevaluable event, Chest discomfort |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | Hepatitis, Hepatocellular injury, Cholestasis, Hepatitis cholestatic, Jaundice, Hepatic function abnormal | |

| Immune system disorders | Drug hypersensitivity | |

| Infections and infestations | Viral infection | Nasopharyngitis |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | Contraindicated product administered, Product communication issue, Ligament sprain, Lower limb fracture, Product use complaint, Product dose omission in error | Intentional product use issue, Toxicity to various agents, Accidental overdose, Inappropriate schedule of product administration, Intentional overdose, Product administration error, Incorrect dose administered, Wrong product administered, Intentional product misuse, Road traffic accident, Product dispensing error, Product administered at inappropriate site, Medication error |

| Investigations | Blood glucose decreased, Amphetamines positive, Drug level increased, Urine amphetamine positive, Blood alkaline phosphatase increased, Gamma-glutamyltransferase increased, Prothrombin level decreased | Body temperature increased, Blood creative phosphokinase increased, Weight increased |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | Hypoglycaemia, Hyponatraemia | Increased appetite |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Torticollis | Muscle tightness, Neck pain, Arthralgia, Joint stiffness, Muscle rigidity, Pain in extremity, Muscular weakness, Trismus |

| Nervous system disorders | Coma, Myoclonus, Generalized tonic-clonic seizure, Epilepsy, Dyskinesia, Toxic encephalopathy, Balance disorder | Hypoesthesia, Amnesia, Sedation, Mental impairment, Serotonin syndrome, Memory impairment, Hypersomnia |

| Product issues | Product taste abnormal, Product substitution issue, Product complaint, Product formulation issue, Product adhesion issue, Product color issue, Product quality issue, Product solubility abnormal | |

| Psychiatric disorders | Affect lability, Hallucination, Abnormal behaviour, Middle insomnia, Mania, Emotional disorder, Nightmare | Tic, Bruxism, Psychotic disorder, Restlessness, Apathy, Depressed mood, Nervousness |

| Renal and urinary disorders | Polyuria, Acute kidney injury, Urinary retention | Pollakiuria21 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | Galactorrhoea, Erection increased, Gynaecomastia | Heavy menstrual bleeding |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | Epistaxis, Respiratory disorder | Respiratory arrest, Oropharyngeal pain, Hyperventilation, Cough, Sleep apnoea syndrome |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | Skin irritation, Purpura, Photosensitivity reaction, Rash morbilliform, Rash maculo-papular, Skin odour abnormal, Dermatitis exfoliative generalised, Skin lesion, Dermatitis bullous, Erythema multiforme | Acne, Rash pruritic, Skin discolouration, Alopecia, Dry skin, Dermatitis |

| Social circumstances | Inability to afford medication, Insurance issue, Physical assault, Bedridden | Impaired driving ability, Educational problem |

| Surgical and medical procedures | Therapy change, Self-medication, Therapy interrupted, Therapy cessation | |

| Vascular disorders | Haematoma, Orthostatic hypotension | Flushing, Pallor, Peripheral coldness, Hot flush, Cyanosis |

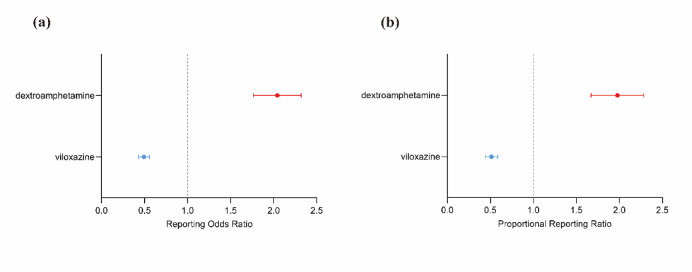

Shared and unique general ADRs of two ADHD medications

By observing and comparing the SOC distributions of viloxazine and dextroamphetamine, it was found that general disorders and administration site conditions were the most common AEs among the two ADHD medications. To further compare the two medications, general disorders and administration site conditions were analyzed disproportionately. We used the ROR and PRR methods (Table 7). Figure 2 shows that by disproportionality analysis. The results suggest that dextroamphetamine is more likely to cause general disorders and administration site conditions than viloxazine.

Table 7.

Analysis of disproportionality focusing on adverse events related to general disorders and conditions at the administration site.

| ROR (95% CI) | PRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Viloxazine | 0.49(0.43–0.56) | 0.55(0.43–0.56) |

| Dextroamphetamine | 2.00(1.79–2.34) | 1.81(1.79–2.33) |

Fig. 2.

Disproportionality analyses of viloxazine and dextroamphetamine related to general disorders and conditions compared to all other drugs in the WHO VigiBase. Dashed lines on reported odds point estimates indicate 95% confidence intervals. a is the reporting odds ratio (ROR), b is the proportional reporting ratio (PRR).

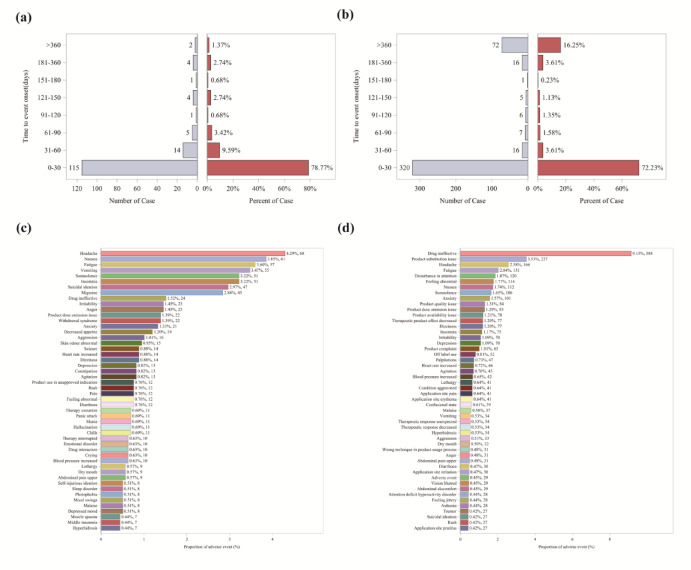

Time to event report distribution of AE reports and top 50 PTs by frequency for adverse events recorded in the FAERS database

Data on viloxazine and dextroamphetamine were extracted from the FAERS database for the period from the first quarter of 2004 to the third quarter of 2024. A total of 561 patients (1,584 adverse events) were identified for viloxazine, and 1,927 patients (6,427 adverse events) for dextroamphetamine.

An analysis was conducted on the time from the start of medication use to the first Adverse Event (AE) report, with results presented in Fig. 3(a, b). It was found that the majority of AE reports related to viloxazine occurred within the first month of use (n = 115), with a significant decrease in reports thereafter. In contrast, for dextroamphetamine, while there was a high incidence of reports within the first month (n = 320), a notable number of adverse event reports also emerged after one year of use (n = 72). Among these 72 dextroamphetamine-related AEs, the most prominent types were drug ineffective (14 cases, 0.7%), product complaint (8 cases, 0.4%), and product substitution issue (7 cases, 0.3%). The top 50 PTs by frequency for AEs from the FAERS database were also collected, as presented in Fig. 3(c, d). Results showed that the most frequently reported AEs associated with viloxazine were headache (4.29%), nausea (3.85%), fatigue (3.6%), vomiting (3.47%), suicidal ideation (3.22%), and insomnia (3.22%). For dextroamphetamine-related AEs, the most common were drug ineffectiveness (9.15%), product substitution issues (3.53%), headache (2.58%), fatigue (2.04%), and disturbance in attention (1.87%). This insight can enhance the understanding and management of the safety issues linked to the two drugs, enabling timely treatment modification to reduce adverse reactions and improve therapeutic outcomes.

Fig. 3.

a, b are the time of occurrence of adverse events associated with viloxazine and dextroamphetamine, respectively. c, d are the top 50 PTs of viloxazine and dextroamphetamine in the FAERS database sorted by frequency of AEs, respectively.

Discussion

Spontaneous reporting systems (SRS) are an integral part of pharmacovigilance to address the safety of potential adverse events (AE) that may not be fully captured in clinical trials because of their limited scope, stringent participant criteria, small sample sizes, and short observation periods, and often do not reflect the diversity of patients and conditions in daily practice25. The SRS is crucial for identifying safety signals and is a primary source for drug safety signal research, drawing from databases such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), the Eudra Vigilance Data Analysis System (EVDAS) and the WHO’s VigiBase®26. WHO-VigiAccess, managed by Sweden’s UMC, is a global pharmaco-vigilance tool with data from over 100 member centers16. FAERS, the FDA’s database, focuses on post-marketing surveillance, collecting US-originated adverse event and medication error data. Both are key for ADR monitoring. The objective of this research is to assess the adverse events associated with ADHD medications that have been reported after they have been marketed, utilizing data from the two database.

The data retrieved from WHO - VigiAccess reveals that approximately 55% of the AEs linked to two ADHD medications originated from the American Continents, which places this region at the top of the regional rankings. This elevated prevalence may potentially be connected to a higher frequency of use of these two medications in the American Continents compared to other regions like Europe1. The data for Asia is close to zero, probably because neither drug is sold in China. No data are available for Africa, even though ADHD prevalence is not low in this region, which may be related to lower material living conditions27,28. In terms of ADHD prevalence, it is estimated to be around 5% in the pediatric and adolescent population, with no notable variations observed across different countries worldwide29,30. This suggests a relatively consistent impact of ADHD on youth irrespective of geographic location. Furthermore, recent research indicates that it is misleading to claim that approximately 50% of children with ADHD will no longer exhibit the condition in adulthood. Instead, the symptoms often vary over time, spanning from childhood through young adulthood. While it is common for individuals to experience occasional periods without symptoms, a significant majority—90%—of those with ADHD, as observed in the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study, continue to manifest some lingering symptoms into early adulthood31. When age data is available and excluding those reports where age is unspecified, the age groups that exhibit the highest reporting rates are predominantly between 18 and 44 years old, which supports the notion of ADHD’s persistence into adult life. AEs are slightly more frequently reported in females compared to males, yet this difference does not reach statistical significance.

AEs with a reported rate ≥ 1% are usually considered common AEs32. Therefore, serious adverse events, including life-threatening events, disability, and birth defects, were uncommon with both ADHD medications. Common ADRs for both drugs were nausea, headache, somnolence, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, dizziness, agitation, irritability, drug ineffectiveness, and decreased appetite. The majority of the top 20 most commonly reported AEs were self-limiting minor events.

According to WHO-VigiAccess data and signal analysis, viloxazine, a new non-stimulant ADHD drug, has ADRs exceeding 10% in nervous system disorders and psychiatric disorders. psychiatric AEs like suicidal ideation, anxiety, and mood swings may stem from its 5-HT regulation, as 5-HT dysfunction is linked to emotional and behavioral issues33. Neurological AEs such as headaches and seizures are also common. viloxazine’s inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake likely causes alertness and sleep pattern fluctuations11,34. Additionally, it has notable gastrointestinal AEs, including nausea and vomiting, suggesting caution in prescribing it to patients with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions11. A case-control study using electronic health records examined patients aged 16–35 admitted to McLean Hospital for event psychosis or mania between 2005 and 2019. Among 1,374 cases and 2,748 controls, past-month dextroamphetamine use was tied to increased psychosis/mania odds, with a dose-response relationship observed. High doses (> 30 mg dextroamphetamine-equivalent) were associated with a 5.28 times higher risk. This highlights the need for caution in prescribing high-dose amphetamines and regular screening for psychosis/mania symptoms35.

By integrating data from the FAERS and VigiAccess databases and analyzing it at the PT level, we’ve identified the five most frequently reported ADRs for viloxazine as headache, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting, which are known common AEs listed in viloxazine’s packaging insert. It is advisable for physicians to monitor patients’ heart rate and blood pressure before initiating treatment, after dose escalation, and on a regular basis2. As for dextroamphetamine, the ADRs identified from the data include drug ineffectiveness, product substitution issues, headache, and fatigue. Moreover, the Time to Event Report distribution of AE reports from the FAERS database indicates that, compared to viloxazine, dextroamphetamine necessitates longer-term monitoring in real-world use. This is because, in addition to the high incidence of adverse effects in the first month after dextroamphetamine use (n = 320), the incidence of adverse effects after one year was significant (n = 72).

WHO-VigiAccess primarily uses the WHO-ART coding system, ensuring global applicability while incorporating MedDRA. It focuses on global ADR signal detection using PRR and ROR. FAERS mainly uses MedDRA to precisely describe AE details and severity36. WHO-VigiAccess is publicly accessible for free queries, while FAERS requires obtaining data files from the FDA website for analysis with professional tools. Using both databases enhances data completeness and study authenticity. It promotes information sharing among regulatory agencies, supports drug development, and aids clinical decision-making by providing comprehensive evidence. However, discrepancies may arise due to differences in data collection, coding, and analysis methods, necessitating data integration and validation.

The main limitations of disproportionate analyses of events reported in publicly accessible pharmacovigilance databases are the voluntary reporting and bias of the databases, the lack of causality assessment and the incompleteness of the data. Such databases are not designed to support nuanced findings that would allow reliable conclusions to be drawn about specific risk populations. In addition, because the WHO’s VigiAccess database is cumulative, ADRs for each year are not available.The number of ADRs collected varies widely when drugs are marketed at different times, and it is not possible to compare signaling differences across all target inhibitors at the same time; therefore, further data mining would not be possible. In this study, we collected the number of ADR cases and PT cases in the past years to compare the ADR reporting rate of different drugs to avoid the effect of the time of drug introduction. The results of the study were limited to the relative outcomes of two newly introduced drugs.

Conclusions

Qelbree (viloxazine) and Xelstrym (dextroamphetamine) are new ADHD treatments that also show potential for managing anxiety and depression. Viloxazine’s common AEs mainly focus on psychiatric, neurological, and gastrointestinal issues, such as suicidal ideation, nausea, headaches, and insomnia. Dextroamphetamine’s AEs are mainly reflected in general disorders and administration site conditions and psychiatric disorders. When prescribing these medications, clinicians should take into account the patient’s age, sex, and medical history. As adolescents are the main users of viloxazine, their growth and development must be carefully monitored. Patients with a history of mental illness are at a higher risk of experiencing severe psychiatric AEs and require closer supervision. Looking ahead, these two drugs are expected to provide safer and more effective treatment options for children and adolescents with ADHD through optimized clinical strategies and more precise individualized treatment plans, thereby promoting the healthy growth and improving the quality of life for this special group.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals and organizations that provided support for this study, including the financial sponsors and technical assistance that participated in this study. The authors declare that they have received financial support for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Projects of the Science and Technology of Taicang City - Basic Research Program (Grant No. TC2021TCYL14).

Author contributions

L.W. collected the database from WHO-VigiAccess. Q.K. performed statistical analysis of the data from WHO-VigiAccess and wrote the manuscript. Y.L. participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript and planned the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

Data were extracted from VigiBase, the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database. All data may be accessible at www.vigiaccess.org, after detailed request to the Uppsala Monitoring Center (Sweden), following privacy requirements. For more information on the process to be granted access and use of these data, please refer to their dedicated website: www.who-umc.org.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lijun Wang and Qingyang Kong have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Castaldelli-Maia, J. M. & Bhugra, D. Analysis of global prevalence of mental and substance use disorders within countries: focus on sociodemographic characteristics and income levels. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 34, 6–15. 10.1080/09540261.2022.2040450 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connor, L., Carbone, S., Gobbo, A., Gamble, H. & Faraone, S. V. Pediatric attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): 2022 updates on Pharmacological management. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol.16, 799–812. 10.1080/17512433.2023.2249414 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajaprakash, M. & Leppert, M. L. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr. Rev.43, 135–147. 10.1542/pir.2020-000612 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechler, K., Banaschewski, T., Hohmann, S. & Häge, A. Evidence-based Pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol. Ther.230, 107940. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107940 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, L. et al. ADHD pharmacotherapy and mortality in individuals with ADHD. Jama331, 850–860. 10.1001/jama.2024.0851 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang, L. & Sareen, R. Retrospective analysis of adverse events associated with non-stimulant ADHD medications reported to the united States food and drug administration. Psychiatry Res.300, 113861. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113861 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalrymple, R. A., McKenna Maxwell, L., Russell, S. & Duthie, J. NICE guideline review: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management (NG87). Archives Disease Child. Educ. Pract. Ed.105, 289–293. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-316928 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López, F. A. & Leroux, J. R. Long-acting stimulants for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a focus on extended-release formulations and the prodrug Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate to address continuing clinical challenges. Atten. Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders. 5, 249–265. 10.1007/s12402-013-0106-x (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olfson, M. et al. Stimulants and cardiovascular events in youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 51, 147–156. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.11.008 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanda, A. et al. Adverse effects of stimulant interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A comprehensive systematic review. Cureus15, e45995–e45995. 10.7759/cureus.45995 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Findling, R. L. et al. Viloxazine in the management of CNS disorders: A historical overview and current status. CNS Drugs. 35, 643–653. 10.1007/s40263-021-00825-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorman, W. J. Viloxazine (Qelbree™) < i > a nonstimulant Extended-Release capsule for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Addict. Nurs.33, 114–115. 10.1097/jan.0000000000000459 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaa, T. ADHD and relative risk of accidents in road traffic: a meta-analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev.62, 415–425. 10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.003 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeves, S. G. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry62, S187–S188, doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2023.09.109 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutler, A. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of dextroamphetamine transdermal system for the treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: results from a pivotal phase 2 study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol.32, 89–97. 10.1089/cap.2021.0107 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Childress, A. & Vaughn, N. A critical review of the dextroamphetamine transdermal system for the treatment of ADHD in adults and pediatric patients. Expert Rev. Neurother.24, 457–464. 10.1080/14737175.2024.2329306 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazell, L. & Shakir, S. A. W. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions - A systematic review. Drug Saf.29, 385–396. 10.2165/00002018-200629050-00003 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srba, J., Descikova, V. & Vlcek, J. Adverse drug reactions: analysis of spontaneous reporting system in Europe in 2007–2009. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.68, 1057–1063. 10.1007/s00228-012-1219-4 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, B. & He, X. Viloxazine,a new approved drug for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Chin. J. New. Drugs. 31, 836–839. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-3734.2022.09.003 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sultana, J., Scondotto, G., Cutroneo, P. M., Morgante, F. & Trifirò, G. Intravitreal Anti-VEGF drugs and signals of dementia and Parkinson-Like events: analysis of the vigibase database of spontaneous reports. Front. Pharmacol.11, 9. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00315 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman, K. B., Dimbil, M., Tatonetti, N. P. & Kyle, R. F. A pharmacovigilance signaling system based on FDA regulatory action and Post-Marketing adverse event reports. Drug Saf.39, 561–575. 10.1007/s40264-016-0409-x (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothman, K. J., Lanes, S. & Sacks, S. T. The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.13, 519–523. 10.1002/pds.1001 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans, S. J., Waller, P. C. & Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.10, 483–486. 10.1002/pds.677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Puijenbroek, E., Diemont, W. & van Grootheest, K. Application of quantitative signal detection in the Dutch spontaneous reporting system for adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf.26, 293–301. 10.2165/00002018-200326050-00001 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew, E. G. Y. et al. Exome sequencing in Asian populations identifies rare deficient < italic > SMPD1 alleles that increase risk of parkinson’s disease. MedRxiv10.1101/2023.08.03.23293387 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel, U. et al. Investigating overlap in signals from EVDAS, FAERS, and VigiBase®. Drug Saf.43, 351–362. 10.1007/s40264-019-00899-y (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bantjes, J. et al. The mental health of university students in South africa: results of the National student survey. J. Affect. Disord.321, 217–226. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.044 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayano, G., Yohannes, K. & Abraha, M. Epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents in africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 1910.1186/s12991-020-00271-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J. & Rohde, L. A. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 164, 942–948. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polanczyk, G. V., Willcutt, E. G., Salum, G. A., Kieling, C. & Rohde, L. A. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol.43, 434–442. 10.1093/ije/dyt261 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibley, M. H. et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am. J. Psychiatry. 179, 142–151. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, C., Borrego, M. E., Roberts, M. H. & Raisch, D. W. Comparison of post-marketing surveillance approaches regarding infections related to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi’s) used in treatment of autoimmune diseases. Exp. Opin. Drug Saf.18, 733–744. 10.1080/14740338.2019.1630063 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasser, A. et al. Evaluating the likelihood to be helped or harmed after treatment with viloxazine extended-release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Clin. Pract.75, e14330. 10.1111/ijcp.14330 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, S. et al. Analysis of risk signals for viloxazine in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder based on the FAERS database. J. Affect. Disord. 382, 274–281. 10.1016/j.jad.2025.04.087 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moran, L. V. et al. Risk of incident psychosis and mania with prescription amphetamines. Am. J. Psychiatry. 181, 901–909. 10.1176/appi.ajp.20230329 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo, M., Shu, Y., Chen, G., Li, J. & Li, F. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) events for niraparib. Sci. Rep.12, 20601. 10.1038/s41598-022-23726-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data were extracted from VigiBase, the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database. All data may be accessible at www.vigiaccess.org, after detailed request to the Uppsala Monitoring Center (Sweden), following privacy requirements. For more information on the process to be granted access and use of these data, please refer to their dedicated website: www.who-umc.org.