Abstract

In the course of synthetic work and mass spectrometry (MS) with hydroxy steroids, we observed not only the loss of H2O but prominent 2 and 4 amu losses using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), leading to confusion of the structural assignments. This loss of 2 amu, which we attributed mainly to oxidation of hydroxyls, varied among 44 steroids and sterols analyzed; 36 showed losses of 2n amu in APCI MS analysis (17/22 Δ5 steroids, 17/19 Δ4 steroids, and 2/3 estrogens). With the Δ5 steroids and sterols, the precursor MH+ was either observed as a minor ion or (more frequently) not detected at all, constituting the base peak in 7/22 cases. With heated electrospray ionization (HESI) MS, 2n amu losses were detected (generally weakly) in 9/44 cases but constituted the base peak in 3/9. In general, the sensitivity (base peak intensity) of steroids correlated with conjugation of the of the steroid frame. Δ4 steroids generally performed best on HESI+ (up to a maximum factor of 8-fold), while Δ5 steroids and sterols performed better on APCI+ (up to >137-fold), except for two trihydroxypregnanes. Estrogens did not show a clear trend. Sensitivity generally increased with the use of NH4F as a mobile phase additive in ESI+ (up to a maximum of 7-fold). We conclude that the prominence of 2n amu losses is variable among steroids and sterols but is more commonly an artifact of APCI MS. These m/z losses can constitute dominant ions that impede detection of the precursor MH+ and complicate structural assignments.

Keywords: mass spectrometry, APCI, HESI, steroids, hydroxy steroids, oxidation, ammonium fluoride, artifacts

Introduction

The introduction of electrospray ionization (ESI) technology revolutionized mass spectrometry (MS) in terms of coupling to HPLC and in the generation of mass spectra of intact molecules. The approach is excellent for both positively and negatively charged molecules, but uncharged molecules (e.g., alkanes, retinoids, and sterols) can be problematic. In many cases, atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) MS adds considerable sensitivity, but some artifacts have been reported. These include water and oxygen adducts, demethylation, decarboxylation, and dehydrogenation, some of which were inherent in the electron impact MS of the past. Several examples of problems with APCI have been documented. − Limited reports of oxidation have appeared, e.g., readily oxidizable compounds derived from hair dyes. Very recently, the presence of oxygen addition artifacts has also been noted.

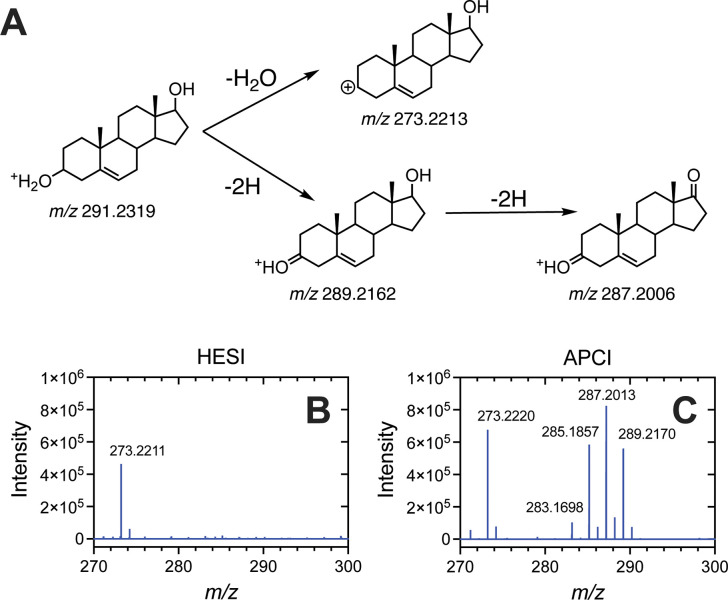

In the course of our work on the synthesis of some sterols, we frequently observed the loss of H2O and esters (acetoxy and formyl groups) in APCI MS. − However, in the synthesis of some other steroids, we often observed products either 2, 4, or (in some cases) up to 6 amu less than expected (generally in terms of the precursor ion, MH+). We have developed reliable derivatization procedures for steroids containing carbonyls and used positive-ion ESI methods successfully for quantification in several cases. ,− However, in the syntheses of (underivatized) steroids, we were often unsure (due to ≥2 amu losses from the MH+ precursor ion in LC-APCI-MS sample analysis, Scheme ) as to the results of simple oxidations and reductions (e.g., NaBH4 and LiAlH4 reduction, Dess–Martin oxidation) and had to turn to 1H and 13C NMR analysis for definitive answers.

1. Complications in Correct Product Ion Characterization in Cases of In-Source Oxidation .

a In this example, the C-20 (red) carbonyl group of pregnenolone is reduced with NaBH4 to yield a +2 amu product. Upon LC-MS analysis, the C-3 (blue) hydroxyl moiety is oxidized to a carbonyl, resulting in a loss of 2 amu and a reduction product that is detected with the same m/z as the starting material (pregnenolone). When the C-3 hydroxyl moiety is instead lost as H2O (i.e., preventing the oxidation to a carbonyl), the +2 amu m/z difference between the starting material and the product is revealed. In this way, the MH+–H2O ions of the starting material and product confirm a successful reaction, while the corresponding MH+ ions are indistinguishable. All molecules are presented in their ionized form. The example ions for 3-acetoxypregnenolone, our synthetic intermediate, are shown above in brackets. Note: NaBH4 reductions yield epimeric alcohols which may separate on reversed phase HPLC, yielding two peaks (diastereomers) bearing identical MH+–2 ions.

We analyzed a number of hydroxy (OH) and keto steroids and sterols using APCI-MS and observed losses of 2 and 4 amu in many cases, as well as −18 (loss of H2O). This phenomenon has apparently not been reported for steroids previously, although LC-APCI-MS analyses of steroid libraries have been presented. , We have now compiled the results of analysis of a series of steroids along with a comparison of fragmentation and sensitivity using heated ESI (HESI) as an alternative approach, employing NH4F to assist ionization.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Most of the steroids (Scheme ) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich-Millipore or Steraloids. Compounds 14 11 and 42 and 41 (FFMAS, follicular fluid meiosis activating sterol, (4β,5α)-4,4-dimethyl-cholestra-8,14,24-trien-3-ol) 10 were synthesized as descrived previously.

2. Structures and Names of Steroids Used in Analysis .

a All steroids are shown in their ionized form (MH+).

17α,20-(OH)2 cholesterol (15) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (a gift from N. Sharifi, Univ. Miami). Etienic acid (29) was converted to its ethyl ester by heating in C2H5OH in the presence of H2SO4 under reflux overnight and then reduced with LiAlH4 or LiAlD4 in (C2H5)2O (2 h, reflux) to give 17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (35). 11-Deoxycorticosterone (19) was reduced to pregn-5-ene-3β,20,21-triol (26) by treatment with NaBH4 or NaBD4 in CH3OH at room temperature (2 h, 23 °C): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 5.27, 4.08, 3.55, 3.34; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 147.5, 124.5, 75.5, 68.1, 64.6, 56.5, 53.1. This 3β,20,21-triol was treated with HIO4 , to yield 17β-formyl-Δ5-androstene-3-ol (37): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.77, 5.37, 2.28, 1.12, 1.01; 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.1, 146.5, 122.6.

UPLC-MS

Steroids (Scheme , dissolved in CH3CN) were injected (10 μL, held at 25 °C) using a Waters Acquity UPLC and separated (flow rate 0.2 mL min–1) using a 2.1 mm × 100 mm (1.7 μm) Acquity BEH octadecylsilane (C18) column (held at 25 °C) with a gradient mobile phase of 0.1% HCO2H dissolved in (A) H2O and (B) CH3CN as follows (expressed as % B, v/v): 0 min, 70%; 0.5 min, 70%; 3 min, 100%; 8 min, 100%; 8.1 min, 70%; 10 min, 70%. For allsterols , this was modified to sample injection in 100% B at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min–1 for 10 min. Column eluates were subjected to APCI ionization (positive ion mode unless noted otherwise) in a Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ XL Orbitrap mass spectrometer in the Vanderbilt Mass Spectrometry Research Core Facility, with a vaporizer temperature of 350 °C, a resolution setting of 60,000, and scanning from m/z 100–800. Data were processed using Xcalibur QualBrowser (Thermo Fisher Scientific) software (version 2.0.7).

HESI analysis was conducted in the same manner as the APCI analysis above with the modification that that ionization was performed using a heated electrospray source (positive-ion mode) with a vaporizer temperature of 300 °C and scanning from m/z 100–500. The linear gradient (flow rate 0.3 mL min–1) was also modified for steroids as follows (expressed as %B, v/v): 0 min, 50%; 0.5 min, 50%; 3 min, 100%; 4.5 min, 100%; 4.6 min, 50%; 6 min, 50%. For oxysterols, the gradient was the same method as with the APCI analysis above, but the flow rate was increased to 0.3 mL min–1. For all sterols, the sample was injected with 100% B at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min–1 for 10 min. For HESI analyses with NH4F, all conditions were kept as described herein with the modification that the mobile phase composition was changed to 0.3 mM NH4F in (A) H2O and (B) CH3OH. For the LC-HESI-MS/MS analyses, the same method was used with the modifications that certain ions identified in the LC-MS run were targeted and fragmented using a collision energy of 35 V.

Results

Initial MS Results

In the course of the synthesis of several hydroxy sterols for other projects, we used APCI MS to verify the results of several reductions and oxidations. ESI proved to be rather insensitive to routinely obtain spectra of sterols, and we employed the general use of APCI+ MS for the analysis of sterols, other steroids, and retinoids. − ,− Several of the spectra of our synthetic derivatives were problematic in deciding whether reactions had been successful (e.g., NaBH4 and LiAlH4 reductions) due to presence of peaks 2 amu lower than expected (i.e., a MH+-2 ion of the product will present with the same m/z as the MH+ ion of the starting material, Scheme ). However, analysis of the MH+–18 ion (loss of H2O) in these samples confirmed a 2 amu m/z increase (alluding to a successful NaBH4 reduction), and a complete reaction was further verified by analysis with TLC and NMR. Due to the dominance and unknown nature of these 2 amu losses, we decided that an investigation into prominence of this effect in the steroid family of molecules was in order.

MS Fragmentation

We examined a series of 44 sterols and other steroids (Scheme , mainly hydroxy) on hand from synthetic work and commercial sources using APCI-MS and HESI-MS, which have been reported to be more useful than standard ESI MS for steroids. , Lists of ions and fragments of the tested steroids and sterols are presented in Table , and mass spectra are presented in the Supporting Information (Supporting Figures S1–S44). As expected, the MS spectra of most of these compounds were dominated by MH+-18n ions (i.e., loss of n × H2O). However, prominent MH+-2 and MH+-4 ions were often observed (Figure ).

1. APCI and HESI Analyses of the Steroids .

| Ion

assignment |

APCI |

HESI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid, calc. MH+ | Theoretical m/z | Assignment | Prominent ions, m/z | Intensity | Prominent ions, m/z | Intensity | |

| Estrogens | |||||||

| 1 | 17β-Estradiol, m/z 273.1849 | 272.1776 | M+ | ND | 272.1766 | 1.5 × 104 | |

| 271.1693 | MH+-2 | 271.1695 | 3.2 × 104 | ND | |||

| 255.1743 | MH+-H2O | 255.1745 | 4.1 × 104 | 255.1735 | 9.2 × 104 | ||

| 2 | Estrone, m/z 271.1693 | 271.1693 | MH+-H2O | 271.1699 | 3.2 × 104 | 271.1684 | 1.7 × 105 |

| 3 | Estriol, m/z 289.1798 | 288.1725 | M+ | ND | 288.1713 | 1.9 × 104 | |

| 287.1642 | MH+-2 | 287.1653 | 2.5 × 105 | ND | |||

| 285.1485 | MH+-4 | 285.1487 | 2.0 × 104 | ND | |||

| 271.1693 | MH+-H2O | 271.1693 | 1.3 × 104 | ND | |||

| 269.1536 | MH+-H2O-2 | 269.1537 | 3.6 × 104 | ND | |||

| Androgens | |||||||

| 4 | Androstenedione, m/z 287.2006 | 287.2006 | MH+ | 287.2010 | 1.10 × 107 | 287.2009 | 2.4 × 107 |

| 285.1849 | MH+-2 | 285.1855 | 1.9 × 106 | ND | |||

| 283.1693 | MH+-4 | 283.1697 | 2.8 × 105 | ND | |||

| 5 | Testosterone, m/z 289.2162 | 289.2162 | MH+ | 289.2170 | 1.6 × 107 | 289.2160 | 2.3 × 107 |

| 287.2006 | MH+-2 | 287.2016 | 2.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 285.1849 | MH+-4 | 285.1859 | 7.8 × 105 | ND | |||

| 271.2056 | MH+-H2O | 271.2064 | 1.4 × 106 | ND | |||

| 6 | 6β-OH testosterone, m/z 305.2111 | 305.2111 | MH+ | 305.2113 | 3.2 × 105 | 305.2119 | 2.5 × 106 |

| 303.1955 | MH+-2 | 303.1956 | 2.3 × 105 | ND | |||

| 301.1798 | MH+-4 | 301.1799 | 1.0 × 105 | ND | |||

| 287.2006 | MH+-H2O | 287.2007 | 2.9 × 105 | ND | |||

| 269.1900 | MH+-2H2O | 269.1900 | 4.2 × 104 | ND | |||

| 7 | 5α-Dihydrotestosterone, m/z 291.2319 | 291.2319 | MH+ | 291.2326 | 2.0 × 105 | 291.2325 | 6.8 × 105 |

| 273.2213 | MH+-H2O | 273.2219 | 7.2 × 104 | 273.2217 | 5.3 × 104 | ||

| 255.2107 | MH+-2H2O | 255.2110 | 2.1 × 104 | ND | |||

| 8 | 19-Nortestosterone, m/z 275.2006 | 275.2006 | MH+ | 275.2011 | 1.2 × 107 | 275.2010 | 1.6 × 107 |

| 273.1849 | MH+-2 | 273.1856 | 7.2 × 105 | ND | |||

| 257.1900 | MH+-H2O | 257.1905 | 8.6 × 105 | 257.1902 | 1.7 × 105 | ||

| 9 | 19-Norandrostenedione, m/z 273.1849 | 273.1849 | MH+ | 273.1852 | 1.1 × 107 | 273.1849 | 2.2 × 107 |

| 271.1693 | MH+-2 | 271.1697 | 6.0 × 105 | ND | |||

| 255.1743 | MH+-H2O | 255.1746 | 2.3 × 105 | ND | |||

| 10 | 19-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1955 | MH | 303.1953 | 3.7 × 106 | 303.1959 | 1.2 × 107 |

| 11 | 11β-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1955 | MH+ | 303.1966 | 1.7 × 107 | 303.1959 | 1.3 × 107 |

| 301.1798 | MH+-2 | 301.1811 | 1.9 × 106 | ND | |||

| 285.1849 | MH+-H2O | 285.1859 | 2.0 × 106 | 285.1850 | 1.6 × 105 | ||

| 267.1743 | MH+-2H2O | 267.1752 | 5.7 × 105 | 267.1743 | 5.0 × 104 | ||

| 32 | Androstadieneone, m/z 271.2056 | 271.2056 | MH+ | 271.2061 | 7.0 × 106 | 271.2057 | 8.9 × 106 |

| 269.1900 | MH+-2 | 269.1907 | 3.7 × 105 | ND | |||

| 33 | Androstadienol, m/z 273.2213 | 273.2213 | MH+ | ND | ND | ||

| 271.2056 | MH+-2 | 271.2057 | 6.4 × 105 | 271.2054 | 5.9 × 104 | ||

| 255.2107 | MH+-H2O | 255.2108 | 1.6 × 106 | 255.2106 | 6.4 × 105 | ||

| Sterols | |||||||

| 12 | Cholesterol, m/z 387.3621 | 385.3465 | MH+-2 | 385.3452 | 6.5 × 105 | ND | |

| 383.3308 | MH+-4 | 383.3296 | 1.1 × 106 | ND | |||

| 369.3516 | MH+-H2O | 369.3505 | 7.7 × 106 | 369.3519 | 2.6 × 105 | ||

| 13 | 22(R)-OH cholesterol, m/z 403.3571 | 401.3414 | MH+-2 | 401.3414 | 2.8 × 105 | ND | |

| 399.3258 | MH+-4 | 399.3259 | 1.2 × 106 | ND | |||

| 397.3101 | MH+-6 | 397.3103 | 1.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 385.3465 | MH+-H2O | 385.3469 | 2.4 × 106 | 385.3466 | 9.4 × 104 | ||

| 367.3359 | MH+-2H2O | 367.3362 | 2.6 × 106 | 367.3361 | 1.2 × 105 | ||

| 14 | 20(R)-,22(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 401.3414 | MH+-H2O | 401.3415 | 4.5 × 105 | 401.3415 | 6.5 × 104 |

| 399.3258 | MH+-H2O-2 | 399.3258 | 4.5 × 105 | ND | |||

| 397.3101 | MH+-H2O-4 | 397.3102 | 4.5 × 105 | ND | |||

| 383.3308 | MH+-2H2O | 383.3310 | 3.3 × 106 | 383.3313 | 3.4 × 105 | ||

| 365.3203 | MH+-3H2O | 365.3205 | 3.5 × 105 | 365.3203 | 1.4 × 104 | ||

| 15 | 17(R)-,20(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 401.3414 | MH+-H2O | 401.3416 | 6.0 × 105 | 401.3413 | 1.2 × 105 |

| 399.3258 | MH+-H2O-2 | 399.3258 | 2.8 × 105 | ND | |||

| 397.3101 | MH+-H2O-4 | 397.3102 | 2.2 × 105 | ND | |||

| 383.3308 | MH+-2H2O | 383.3311 | 2.7 × 106 | 383.3308 | 9.3 × 105 | ||

| 365.3203 | MH+-3H2O | 365.3206 | 1.2 × 106 | 365.3203 | 6.1 × 104 | ||

| 40 | 24,25-Dihydrolanosterol, m/z 429.4091 | 425.3778 | MH+-4 | 425.3772 | 2.3 × 104 | ND | |

| 411.3985 | MH+-H2O | 411.3975 | 3.6 × 106 | ND | |||

| 41 | 14-CDO dihydrolanosterol, m/z 444.3946 | 444.3946 | MH+ | 444.3930 | 6.8 × 105 | 444.3824 | 1.1 × 104 |

| 426.3841 | MH+-H2O | 426.3824 | 2.6 × 106 | 426.3843 | 1.9 × 104 | ||

| 42 | FF-MAS, m/z 413.3778 | 413.3778 | MH+ | 413.3768 | 2.0 × 106 | ND | |

| 395.3672 | MH+-H2O | 395.3665 | 1.6 × 105 | ND | |||

| 43 | β-Sitosterol, m/z 415.3934 | 413.3778 | MH+-2 | 413.3770 | 5.1 × 105 | ND | |

| 411.3621 | MH+-4 | 411.3613 | 4.3 × 105 | ND | |||

| 397.3829 | MH+-H2O | 397.3823 | 4.6 × 106 | ND | |||

| 44 | Ergosterol, m/z 397.3465 | 379.3359 | MH+-H2O | 379.3356 | 2.0 × 104 | ND | |

| Pregnenolone derivatives (Δ5) | |||||||

| 16 | Pregnenolone, m/z 317.2475 | 317.2475 | MH+ | ND | 317.2473 | 9.4 × 104 | |

| 315.2319 | MH+-2 | 315.2320 | 1.5 × 106 | ND | |||

| 313.2162 | MH+-4 | 313.2164 | 1.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 311.2006 | MH+-6 | 311.2008 | 3.2 × 105 | ND | |||

| 299.2369 | MH+-H2O | 299.2372 | 4.9 × 105 | 299.2369 | 8.1 × 105 | ||

| 17 | 3-OAc pregnenolone, m/z 359.2581 | 357.2424 | MH+-2 | 357.2429 | 4.1 × 105 | 357.2421 | 7.3 × 105 |

| 299.2369 | MH+-OAc | 299.2282 | 3.2 × 104 | 299.2280 | 1.5 × 104 | ||

| 297.2213 | MH+-OAc-2 | 297.2218 | 2.6 × 106 | 297.2211 | 6.1 × 105 | ||

| 18 | Dehydroepiandosterone (DHEA), m/z 289.2162 | 289.2162 | MH+ | 289.2165 | 7.0 × 104 | 289.2166 | 3.5 × 104 |

| 287.2006 | MH+-2 | 287.2009 | 1.1 × 106 | ND | |||

| 285.1849 | MH+-4 | 285.1853 | 6.4 × 105 | ND | |||

| 271.2056 | MH+-H2O | 271.2060 | 6.7 × 105 | 271.2061 | 3.9 × 105 | ||

| 31 | 17α-OH pregnenolone, m/z 333.2424 | 331.2268 | MH+-2 | 331.2274 | 3.7 × 104 | ND | |

| 329.2111 | MH+-4 | 329.2115 | 1.2 × 104 | ND | |||

| 315.2319 | MH+-H2O | 315.2292 | 3.5 × 104 | ND | |||

| 313.2162 | MH+-H2O-2 | 313.2169 | 1.3 × 105 | ND | |||

| 311.2006 | MH+-H2O-4 | 311.2011 | 1.0 × 105 | ND | |||

| 297.2213 | MH+-2H2O | 297.2217 | 1.6 × 104 | ND | |||

| Progesterone derivatives (Δ4) | |||||||

| 22 | Algestone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2217 | MH+ | 347.2221 | 7.5 × 106 | 347.2222 | 7.7 × 106 |

| 345.2060 | MH+-2 | 345.2066 | 5.9 × 105 | 345.2068 | 4.1 × 104 | ||

| 23 | 11-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2268 | MH+ | 331.2270 | 3.0 × 107 | 331.2267 | 1.9 × 107 |

| 329.2111 | MH+-2 | 329.2117 | 3.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 313.2162 | MH+-H2O | 313.2166 | 4.0 × 106 | 313.2162 | 2.8 × 105 | ||

| 24 | 17α-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2268 | MH+ | 331.2275 | 1.3 × 107 | 331.2272 | 3.4 × 107 |

| 329.2111 | MH+-2 | 329.2122 | 5.2 × 105 | ND | |||

| 313.2162 | MH+-H2O | 313.2171 | 3.4 × 106 | 313.2162 | 1.5 × 105 | ||

| 311.2006 | MH+-H2O-2 | 311.2015 | 1.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 39 | Progesterone, m/z 315.2319 | 315.2319 | MH+ | 315.2328 | 2.0 × 107 | 315.2327 | 4.0 × 107 |

| 313.2162 | MH+-2 | 313.2176 | 3.2 × 106 | ND | |||

| 311.2006 | MH+-4 | 311.2020 | 6.9 × 105 | ND | |||

| Glucocorticoid | |||||||

| 25 | Hydrocortisone, m/z 363.2166 | 363.2166 | MH+ | 363.2168 | 4.0 × 106 | 363.2172 | 1.3 × 107 |

| 361.2010 | MH+-2 | 361.2012 | 1.1 × 105 | 361.2015 | 4.5 × 105 | ||

| MH+-H2O | 345.2062 | 1.4 × 105 | 345.2061 | 4.2 × 104 | |||

| Mineralocorticoid derivatives | |||||||

| 19 | 21-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2268 | MH+ | 331.2269 | 1.3 × 107 | 331.2273 | 2.0 × 107 |

| 329.2111 | MH+-2 | 329.2113 | 2.0 × 106 | 329.2119 | 6.5 × 105 | ||

| 327.1955 | MH+-4 | 327.1957 | 1.3 × 106 | ND | |||

| 325.1798 | MH+-6 | 325.1801 | 7.8 × 105 | ND | |||

| 313.2162 | MH+-H2O | 313.2164 | 1.4 × 106 | 313.2166 | 1.4 × 104 | ||

| 20 | 21-OAc progesterone, m/z 373.2373 | 373.2373 | MH+ | 373.2374 | 1.3 × 107 | 373.2378 | 3.9 × 107 |

| 313.2162 | MH+-OAc | 313.2165 | 4.1 × 106 | 313.2164 | 8.6 × 104 | ||

| 311.2006 | MH+-OAc-2 | 311.2009 | 9.1 × 105 | ND | |||

| 21 | Aldosterone, m/z 361.2010 | 343.1904 | MH+-H2O | 343.1911 | 7.7 × 106 | 343.1906 | 9.1 × 106 |

| 341.1747 | MH+-H2O-2 | 341.1755 | 2.4 × 105 | ND | |||

| 325.1798 | MH+-2H2O | 325.1805 | 2.6 × 105 | 325.1798 | 1.0 × 105 | ||

| 26 | 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 335.2581 | 333.2424 | MH+-2 | ND | 333.2432 | 3.5 × 105 | |

| 317.2475 | MH+-H2O | 317.2476 | 1.5 × 104 | 317.2480 | 2.3 × 104 | ||

| 299.2369 | MH+-2H2O | 299.2373 | 7.5 × 104 | 299.2373 | 1.0 × 105 | ||

| 281.2264 | MH+-3H2O | 281.2267 | 1.2 × 105 | 281.2269 | 1.9 × 105 | ||

| 27 | [3,20-d 2] 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 337.2706 | 334.2487 | MH+-3 | ND | 334.2488 | 4.4 × 105 | |

| 319.2601 | MH+-H2O | 319.2600 | 1.4 × 104 | 319.2600 | 2.8 × 104 | ||

| 301.2495 | MH+-2H2O | 301.2495 | 1.0 × 105 | 301.2497 | 2.0 × 105 | ||

| 283.2389 | MH+-3H2O | 283.2390 | 1.9 × 105 | 283.2390 | 2.8 × 105 | ||

| 38 | Corticosterone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2217 | MH+ | 347.2222 | 2.0 × 106 | 347.2223 | 6.0 × 106 |

| 345.2060 | MH+-2 | 345.2067 | 2.1 × 105 | 345.2065 | 2.2 × 104 | ||

| 343.1904 | MH+-4 | 343.1908 | 7.8 × 104 | ND | |||

| 329.2111 | MH+-H2O | 329.2116 | 1.3 × 105 | 329.2114 | 4.2 × 104 | ||

| 311.2006 | MH+-2H2O | 311.2010 | 8.4 × 104 | 311.2070 | 1.4 × 104 | ||

| Miscellaneous steroids | |||||||

| 28 | 3-Keto-4-etiocholenic acid, m/z 317.2111 | 317.2111 | MH+ | 317.2114 | 7.8 × 106 | 317.2119 | 2.2 × 107 |

| 315.1955 | MH+-2 | 315.1960 | 4.1 × 105 | ND | |||

| 29 | Etienic acid, m/z 319.2268 | 317.2111 | MH+-2 | 317.2109 | 2.8 × 104 | ND | |

| 315.1955 | MH+-4 | 315.1952 | 2.8 × 104 | ND | |||

| 301.2162 | MH+-H2O | 301.2162 | 3.3 × 105 | 301.2162 | 2.2 × 105 | ||

| 299.2006 | MH+-H2O-2 | 299.2005 | 1.4 × 104 | ND | |||

| 30 | 24-Bisnor-5-cholenic acid-3β-ol, m/z 347.2581 | 345.2424 | MH+-2 | 345.2429 | 1.8 × 104 | ND | |

| 329.2475 | MH+-H2O | 329.2480 | 8.5 × 105 | 329.2477 | 4.8 × 105 | ||

| 327.2319 | MH+-H2O-2 | 327.2322 | 2.7 × 104 | ND | |||

| 34 | Androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol, m/z 291.2319 | 289.2162 | MH+-2 | 289.2162 | 5.6 × 105 | ND | |

| 287.2006 | MH+-4 | 287.2006 | 8.3 × 105 | ND | |||

| 285.1849 | MH+-6 | 285.1849 | 5.9 × 105 | ND | |||

| 273.2213 | MH+-H2O | 273.2213 | 6.8 × 105 | 273.2211 | 4.6 × 105 | ||

| 271.2056 | MH+-H2O-2 | 271.2055 | 5.7 × 104 | ND | |||

| 255.2107 | MH+-2H2O | 255.2108 | 3.1 × 105 | 255.2105 | 1.1 × 105 | ||

| 35 | 17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 305.2475 | 303.2319 | MH+-2 | 303.2318 | 2.3 × 105 | 303.2320 | 2.8 × 105 |

| 301.2162 | MH+-4 | 301.2162 | 1.8 × 105 | ND | |||

| 287.2369 | MH+-H2O | 287.2370 | 1.8 × 105 | 287.2372 | 5.9 × 105 | ||

| 269.2264 | MH+-2H2O | 269.2264 | 8.1 × 105 | 269.2265 | 5.4 × 105 | ||

| 36 | d2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 307.2601 | 305.2444 | MH+-2 | 305.2450 | 1.6 × 105 | ND | |

| 302.2225 | MH+-5 | 302.2231 | 7.1 × 104 | ND | |||

| 289.2495 | MH+-H2O | 289.2501 | 3.1 × 105 | 289.2497 | 3.0 × 105 | ||

| 271.2389 | MH+-2H2O | 271.2395 | 2.5 × 105 | 271.2390 | 5.2 × 104 | ||

| 37 | 17β-Formyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 303.2319 | 303.2319 | MH+ | 303.2326 | 2.0 × 105 | ND | |

| 301.2162 | MH+-2 | 301.2170 | 2.0 × 106 | 301.2166 | 1.9 × 106 | ||

| 299.2006 | MH+-5 | 299.2014 | 5.4 × 105 | ND | |||

| 285.2213 | MH+-H2O | 285.2220 | 7.4 × 105 | 285.2216 | 1.2 × 106 | ||

Values recorded in plain text were determined at 100 μM steroid concentration, while values in bold text were determined at 500 μM (injection volume 10 μL, i.e., 1 or 5 nmol). ND: not detected (response <1 × 104).

1.

Mass spectra of four molecules showing strong 2n amu losses (2-electron oxidations, n= 1, 2, or 3). (A) 22(R)-OH cholesterol (13), (B) 6β-OH testosterone (6), (C) pregnenolone (16), and (D) dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, 18). The exact m/z value of the MH+ precursor ion is indicated above each panel. The major ions detected are printed on each panel (note: the MH+ ion is not always detected).

In the cases of 22(R)-OH cholesterol (13, Figure A), pregnenolone (16, Figure C), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, 18, Figure D) the MH+ ion was either absent or present in very low abundance (near baseline level). With 6β-OH testosterone (6, Figure B) the MH+ ion was the base peak, though a strong prevalence of MH+-2 and MH+-4 ions was observed. Interestingly, in the case of the six Δ5 steroids and sterols (i.e., C-3 hydroxy; pregnenolone and DHEA), a 2n-electron oxidation was the base peak rather than the generally dominant MH+-H2O (−18 amu) ion (Supporting Information, compounds 16, 17, 18, 31, 34, and 37). (This includes the possibility of a 2n-electron oxidation occurring in combination with the loss of a water or acetoxy group, i.e., [MH+–H2O– 2n] ions). In most (5/6) cases, the base peak was a single 2n-electron oxidation (i.e., n = 1), with the exception of androst-5-ene-3β-ol (34, n = 2). A 2n-electron oxidation was also the base peak for the estrogen estriol (3, n = 1). In cases where multiple hydroxyl groups are present in the molecule, the base peak may be the loss of n × H2O (e.g., a value of n = 2 was observed as the base peak of 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (13), Table , Supporting Information). Of the 44 steroids and sterols analyzed, 36 showed some form of a 2n amu loss in APCI MS analysis (17/22 Δ5 steroids, 17/19 Δ4 steroids, and 2/3 estrogens) (Table ).

In the case of a deuterated steroid (35 and 36), the prevalence of a MH+-5 ion (loss of 2H from one site and H + D from another, Figure A) provided further evidence that the observed MH+-2n ions were products of carbinol oxidation, i.e., the loss of deuterium was only possible at one site.

2.

Comparison of the APCI mass spectra d 0-(35) and d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (36). (A) Scheme illustrating the products of the oxidation of the 3β-OH group followed by the 17β-OH group of d 0- (upper) and d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (lower). The exact m/z values are displayed under each molecule. Mass spectra of 100 μM standards of (B) d 0-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (35) and (C) d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (36) are shown (1 nmol injected), with the most prominent ions labeled. Ions colored red result from the loss of deuterium.

In the case of d 0-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (35), the dominant ions were MH+-2, MH+-4, and MH+-6 (Figure B) as we observed with other steroids (Figure , Supporting Information). When carbon C-17 was deuterated (d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, 36, Figure A), the distribution shifted to MH+-2, MH+-5, and MH+-7 (Figure C). We did not observe any 3 or 5 amu losses in nondeuterated steroids.

In HESI-MS analysis of the same steroid library, 2n electron oxidations were less prevalent (Figure , Supporting Information).

3.

Comparison of HESI and APCI MS spectra of androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol (34). (A) Scheme illustrating the products of the loss of the 3β-OH group (−18 amu, upper) or two sequential oxidations of the 3β-OH and 17β-OH groups (−2 amu, lower) of androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol (34). The exact m/z values are displayed under each molecule. (B) HESI and (C) APCI MS spectra of a 100 μM standard of androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol (34), with the most prominent ions labeled.

However, the losses were detected (generally weakly) in 9 of the 44 analyzed steroids and sterols (Supporting Information, compounds 17, 19, 22, 25, 26, 27, 35, 37, and 38) and constituted the base peak in 3 of those (26, 27, and 37). In an example case of a typical APCI vs HESI MS comparison, androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol (34) HESI-MS analysis yielded two dominant ions, MH+-18 and MH+-36 (both losses of n × H2O), with the former ion being the base peak (Figure B). Conversely, when the same sample was analyzed via APCI-MS, a series of MH+-2n ions was generated in addition to the MH+-18 ion (which was similar in intensity to the HESI-MS analyzed sample), with the MH+-4 ion being the base peak (Figure A). Neither ionization method revealed the MH+ ion. APCI MS frequently generated more ions, generally as −2 amu losses, than the same steroid subjected to HESI MS (Supporting Information).

Alternative Mechanism for Ion Generation

A recent report of LC-ESI MS studies of the sesquiterpene artemisinic acid identified MH+-2 ions in chromatograms but attributed the origin to a mechanism involving the loss of allylic hydride (i.e., MH+-2H = M+-H). To determine whether such a mechanism might also generate the MH+-2 ions we report primarily in APCI analyses of Δ5 steroids, we reasoned that reduction of the Δ5 bond and thus elimination of the allylic site should reveal the contribution of allylic hydride loss to artifactual ion generation. We selected dehydroepiandrosterone (18), a Δ5 steroid with dominant MH+-2n ions (Table , Figure ), for this experiment and subjected the molecule to hydrogenation using palladium-on-carbon as a catalyst to yield allo-DHEA. LC-APCI-MS analysis of the crude sample revealed the starting material (DHEA) and product (allo-DHEA) (Supporting Figure S45). As previously reported, the MH+-2n ions of DHEA were dominant with only a weak MH+ ion (m/z 289) detected (Figure ). When the Δ5 bond was reduced (to yield allo-DHEA), the ion distribution shifted in the direction of MH+-(n × H2O) and MH+ ions, where the MH+ ion (sparsely detected for DHEA) appeared at ∼20% relative intensity and the MH+-(n × H2O) ions (n = 1, 2) were observed at ∼95% and ∼90% relative intensity, respectively (roughly ∼50% and ∼20%, respectively, for DHEA). However, in allo-DHEA the base peak was still a MH+-2n ion, as had been shown for DHEA. Further efforts were made to assess the requirement for protons from the HPLC mobile phase in generating MH+-2n ions (carbinol oxidation vs hydride loss) using deuterated ionization salts (ND4OAc, DCO2D), although the data were inconclusive.

Further efforts to characterize the MH+-2 ions were conducted by using targeted LC-MS/MS fragmentation analysis. Compound 37 was selected as a molecule that demonstrated prominent MH+-2 ions in both APCI+ and HESI+ MS (Supporting Figure S37) and was subjected to both APCI+ and HESI+ MS/MS analysis targeting the MH+ ion (m/z 303), the MH+-2 ion (m/z 301), and the MH+-H2O ion (m/z 285). As previously observed, the MH+-2 ion was dominant, and subsequent fragmentation of that ion revealed identical product ions with both APCI+ and HESI+, which were MH+-(n × H2O)-2 ions (Supporting Figure S46). APCI+ and HESI+ MS/MS analysis of the MH+-2 ion yielded nearly identical m/z spectra, suggesting they correspond to the same structure in both ionization methods. The MH+-H2O ion (m/z 285) observed in the untargeted analysis (Supporting Figure S37) was not detected as a fragment ion in the targeted run, and the base peak was the MH+-H2O-2 ion (m/z 283) that was detected near the baseline level in the untargeted approach (Supporting Information, Figure S37). Oxidation of the C-3 carbinol of 37 (detected as a MH+-2 ion) eliminates the only hydroxyl moiety in the structure (Scheme ) that might protonate and leave (as H2O), yet a MH+-H2O-2 ion was detected as the base peak in the targeted run. To assess the necessity of free hydroxyl moieties for the generation of MH+-H2O ions, APCI-MS/MS fragmentation of progesterone (39, a Δ4 steroid with C-3 and C-20 ketones) was conducted. MS/MS fragmentation of the precursor ion (m/z 315, the base peak in the untargeted run) yielded product ions of MH+-(n × H2O), and a base peak was observed where n = 1 (m/z 297, Supporting Figure S46), an ion that was not detected in the untargeted run (Supporting Figure S39). Formation of the MH+-H2O ion was thus not observed to be dependent on the presence of a carbinol in the molecular structure.

MS Sensitivity

In addition to a difference in ions generated by each ionization method (Table , Figure , Supporting Information), we also predictably observed differences in overall detection sensitivity. We compared the sensitivity of APCI and HESI with all 44 steroids in Table (mass spectra are available in the Supporting Information) using a conventional mobile phase of 0.1% HCO2H in H2O/CH3CN (see Experimental Section).

2. Comparison of APCI and ESI .

| APCI |

HESI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid, calc. MH+ | Base peak, m/z | Intensity | Base peak, m/z | Intensity | Ratio HESI/APCI | |

| Estrogens | ||||||

| 1 | 17β-Estradiol, m/z 273.1849 | 255.1745 | 4.1 × 104 | 255.1735 | 9.2 × 104 | 2.2 |

| 2 | Estrone, m/z 271.1693 | 271.1699 | 3.2 × 104 | 271.1684 | 1.7 × 105 | 5.3 |

| 3 | Estriol, m/z 289.1798 | 287.1653 | 2.5 × 105 | 288.1713 | 1.9 × 104 | 0.08 |

| Androgens | ||||||

| 4 | Androstenedione, m/z 287.2006 | 287.2010 | 1.1 × 107 | 287.2009 | 2.4 × 107 | 2.2 |

| 5 | Testosterone, m/z 289.2162 | 289.2170 | 1.6 × 107 | 289.2160 | 2.3 × 107 | 1.4 |

| 6 | 6β-OH testosterone, m/z 305.2111 | 305.2113 | 3.2 × 105 | 305.2119 | 2.5 × 106 | 7.8 |

| 7 | 5α-Dihydrotestosterone, m/z 291.2319 | 291.2326 | 2.0 × 105 | 291.2325 | 6.8 × 105 | 3.4 |

| 8 | 19-Nortestosterone, m/z 275.2006 | 275.2011 | 1.2 × 107 | 275.2010 | 1.6 × 107 | 1.3 |

| 9 | 19-Norandrostenedione, m/z 273.1849 | 273.1852 | 1.1 × 107 | 273.1849 | 2.2 × 107 | 2.0 |

| 10 | 19-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1953 | 3.7 × 106 | 303.1959 | 1.2 × 107 | 3.2 |

| 11 | 11β-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1966 | 1.7 × 107 | 303.1959 | 1.3 × 107 | 0.8 |

| 32 | Androstadieneone, m/z 271.2056 | 271.2061 | 7.0 × 106 | 271.2057 | 8.9 × 106 | 1.3 |

| 33 | Androstadienol, m/z 273.2213 | 255.2108 | 1.6 × 106 | 255.2106 | 6.4 × 105 | 0.4 |

| Sterols | ||||||

| 12 | Cholesterol, m/z 387.3621 | 369.3505 | 7.7 × 106 | 369.3519 | 2.6 × 105 | 0.03 |

| 13 | 22(R)-OH cholesterol, m/z 403.3571 | 367.3362 | 2.6 × 106 | 367.3361 | 1.2 × 105 | 0.05 |

| 14 | 20(R)-,22(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 383.3310 | 3.3 × 106 | 383.3313 | 3.4 × 105 | 0.1 |

| 15 | 17(R)-,20(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 383.3311 | 2.7 × 106 | 383.3308 | 9.3 × 105 | 0.3 |

| 40 | 24,25-Dihydrolanosterol, m/z 429.4091 | 411.3975 | 3.6 × 106 | ND | N/A | |

| 41 | 14-CDO dihydrolanosterol, m/z 444.3946 | 426.3824 | 2.6 × 106 | 426.3843 | 1.9 × 104 | 0.007 |

| 42 | FF-MAS, m/z 413.3778 | 413.3768 | 2.0 × 106 | ND | N/A | |

| 43 | β-Sitosterol, m/z 415.3934 | 397.3823 | 4.6 × 106 | ND | N/A | |

| 44 | Ergosterol, m/z 397.3465 | 379.3356 | 2.0 × 104 | ND | N/A | |

| Pregnenolone derivatives | ||||||

| 16 | Pregnenolone, m/z 317.2475 | 315.2320 | 1.5 × 106 | 299.2369 | 8.1 × 105 | 0.5 |

| 17 | 3-OAc pregnenolone, m/z 359.2581 | 297.2218 | 2.6 × 106 | 357.2421 | 7.3 × 105 | 0.3 |

| 18 | Dehydroepiandosterone, m/z 289.2162 | 287.2009 | 1.1 × 106 | 271.2061 | 3.9 × 105 | 0.4 |

| 31 | 17α-OH pregnenolone, m/z 331.2268 | 313.2169 | 1.3 × 105 | ND | N/A | |

| Progesterone derivatives | ||||||

| 22 | Algestone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2221 | 7.5 × 106 | 347.2222 | 7.7 × 106 | 1.0 |

| 23 | 11-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2270 | 3.0 × 107 | 331.2267 | 1.9 × 107 | 0.6 |

| 24 | 17α-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2275 | 1.3 × 107 | 331.2272 | 3.4 × 107 | 2.6 |

| 39 | Progesterone, m/z 315.2319 | 315.2328 | 2.0 × 107 | 315.2327 | 4.0 × 107 | 2.0 |

| Glucocorticoid | ||||||

| 25 | Hydrocortisone, m/z 363.2166 | 363.2168 | 4.0 × 106 | 363.2172 | 1.3 × 107 | 3.3 |

| Mineralocorticoid derivatives | ||||||

| 19 | 21-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2269 | 1.3 × 107 | 331.2273 | 2.0 × 107 | 1.5 |

| 20 | 21-OAc progesterone, m/z 373.2373 | 373.2374 | 1.3 × 107 | 373.2378 | 3.9 × 107 | 3.0 |

| 21 | Aldosterone, m/z 361.2010 | 343.1911 | 7.7 × 106 | 343.1906 | 9.1 × 106 | 1.2 |

| 26 | 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 335.2581 | 281.2267 | 1.2 × 105 | 333.2432 | 3.5 × 105 | 2.9 |

| 27 | [3,20-d 2] 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 337.2706 | 283.2390 | 1.9 × 105 | 334.2488 | 4.4 × 105 | 2.3 |

| 38 | Corticosterone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2222 | 2.0 × 106 | 347.2223 | 6.0 × 106 | 3.0 |

| Miscellaneous steroids | ||||||

| 28 | 3-Keto-4-etiocholenic acid, m/z 317.2111 | 317.2114 | 7.8 × 106 | 317.2119 | 2.2 × 107 | 2.8 |

| 29 | Etienic acid, m/z 319.2268 | 301.2162 | 3.3 × 105 | 301.2162 | 2.2 × 105 | 0.7 |

| 30 | 24-Bisnor-5-cholenic acid-3β-ol, m/z 347.2581 | 329.2480 | 8.5 × 105 | 329.2477 | 4.8 × 105 | 0.6 |

| 34 | Androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol, m/z 291.2319 | 287.2006 | 8.3 × 105 | 273.2211 | 4.6 × 105 | 0.6 |

| 35 | 17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 305.2475 | 269.2264 | 8.1 × 105 | 287.2372 | 5.9 × 105 | 0.7 |

| 36 | d2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 307.2601 | 289.2501 | 3.1 × 105 | 289.2497 | 3.0 × 105 | 1.0 |

| 37 | 17β-Formyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 303.2319 | 301.2170 | 2.0 × 106 | 301.2166 | 1.9 × 106 | 1.0 |

Values recorded in plain text were determined at 100 μM steroid concentration, while values in bold text were determined at 500 μM (i.e., 10 μL injected = 1 or 5 nmol). Differences in steroid concentration were accounted for, where appropriate, in the calculation of the intensity ratio. ND: not detected (response <1 × 104). N/A: cannot compute signal ratio, as one ionization method did not yield a detectable signal.

In general, the difference of the base peak intensity between APCI and HESI for the 44 tested compounds uncommonly exceeded 3-fold. The major exceptions to this were sterols (12–15) and pregnenolone derivatives (Δ5 steroids, 16–18, 31), which generally demonstrated a pronounced advantage of APCI-MS over HESI-MS (Table ). For the tested sterols, the effect was a minimum of a 3.3-fold increase in sensitivity with APCI MS, but was 30-fold for cholesterol (12) and 137-fold for 14-CDO dihydrolanosterol (41), and several sterols were only detectable with APCI-MS (40, 42–44) (Table ). For pregnenolone derivatives, the advantage of APCI was >2-fold (17-OH pregnenolone (31) was not detected using a conventional HESI method). For glucocorticoids (25) and mineralocorticoids or trihydroxypregnanes (19–21, 25–27, 38), HESI was generally preferable, giving base peak intensities 1.0–3.3-fold higher than those of APCI-MS. For derivatives of androstenedione (4–11, 32, 33) and progesterone (22–24, 39) (all almost exclusively Δ4 steroids), HESI was again generally preferred, with base peak intensities 0.6–3.4-fold those of APCI, with the main exceptions being a 7.8-fold increase in signal observed with 6β-OH testosterone (6) and a 2.5-fold decrease in signal with androstadienol (33, the lone Δ5 steroid). For the remaining “miscellaneous” steroids (28–30, 34–37), the majority of which are Δ5 steroids, there was minimal difference between the methods with base peak intensities being 1.0–1.7-fold those of APCI, the exception being 3-keto-4-etiocholenic acid (28), the lone Δ4 steroid, with a 2.8-fold advantage of HESI.

Effect of NH4F

The analysis of steroids via HESI-MS has been reported to be enhanced by the use of NH4F as a mobile phase additive in both positive and negative ion modes. − Accordingly, we also analyzed our library of 44 steroids and sterols with HESI MS and the addition of 0.3 mM NH4F to the mobile phase. For most of the tested steroids, the intensity of the base peak increased in the presence of NH4F, but rarely >4-fold (Table ). Increases of 1.2–4.0-fold were observed for Δ4 steroids (androgens (4–11, 32, 33), progesterone derivatives (22–24, 39), and a “miscellaneous” steroid (28)), 1.7–4.8-fold for glucocorticoids (25) and mineralocorticoids or trihydroxypregnanes (19–21, 25–27, 38), and 1.5–5.1-fold for oxysterols (13–15, 41) while the precursor sterols (12, 40, 42–44) were not detected. One outlier was androstadieneone (32), with a 7-fold sensitivity increase with the NH4F mobile phase. The pregnenolone derivatives (16–18, 31, and the “miscellaneous” steroids 29–30, 34–37) presented an interesting exception to this rule, generally showing lower base peak intensity, i.e., 0.1–0.9-fold that of the formic acid mobile phase, except 17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (35) (2.9-fold increase).

3. Comparison of Mobile Phase Additives in HESI + .

| HCO2H |

0.3

mM NH4F |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid, calc. MH+ | Base peak, m/z | Intensity | Base peak, m/z | Intensity | Ratio NH4F/HCOOH | |

| Estrogens | ||||||

| 1 | 17β-Estradiol, m/z 273.1849 | 255.1735 | 9.2 × 104 | 255.1737 | 1.6 × 104 | 0.2 |

| 2 | Estrone, m/z 271.1693 | 271.1684 | 1.7 × 105 | 288.1952* | 1.9 × 105 | 1.1 |

| 3 | Estriol, m/z 289.1798 | 288.1713 | 1.9 × 104 | 306.2064* | 3.4 × 105 | 18 |

| Androgens | ||||||

| 4 | Androstenedione, m/z 287.2006 | 287.2009 | 2.4 × 107 | 287.1989 | 4.8 × 107 | 2.0 |

| 5 | Testosterone, m/z 289.2162 | 289.2160 | 2.3 × 107 | 289.2148 | 6.6 × 107 | 2.9 |

| 6 | 6β-OH testosterone, m/z 305.2111 | 305.2119 | 2.5 × 106 | 305.2101 | 1.0 × 107 | 4.0 |

| 7 | 5α-Dihydrotestosterone, m/z 291.2319 | 291.2325 | 6.8 × 105 | 291.2307 | 8.0 × 105 | 1.2 |

| 8 | 19-Nortestosterone, m/z 275.2006 | 275.2010 | 1.6 × 107 | 275.1990 | 4.3 × 107 | 2.7 |

| 9 | 19-Norandrostenedione, m/z 273.1849 | 273.1849 | 2.2 × 107 | 273.1837 | 4.0 × 107 | 1.8 |

| 10 | 19-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1959 | 1.2 × 107 | 303.1937 | 3.8 × 107 | 3.2 |

| 11 | 11β-OH androstenedione, m/z 303.1955 | 303.1959 | 1.3 × 107 | 303.1940 | 4.4 × 107 | 3.4 |

| 32 | Androstadieneone, m/z 271.2056 | 271.2057 | 8.9 × 106 | 271.2046 | 6.2 × 107 | 7.0 |

| 33 | Androstadienol, m/z 273.2213 | 255.2106 | 6.4 × 105 | 273.2205 | 2.0 × 106 | 3.1 |

| Sterols | ||||||

| 12 | Cholesterol, m/z 387.3621 | 369.3519 | 2.6 × 105 | ND | N/A | |

| 13 | 22(R)-OH cholesterol, m/z 403.3571 | 367.3361 | 1.2 × 105 | 385.3447 | 5.6 × 105 | 4.7 |

| 14 | 20(R)-,22(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 383.3313 | 3.4 × 105 | 383.3297 | 5.2 × 105 | 1.5 |

| 15 | 17(R)-,20(R)-(OH)2 cholesterol, m/z 419.3520 | 383.3308 | 9.3 × 105 | 365.3188 | 4.7 × 106 | 5.1 |

| 40 | 24,25-Dihydrolanosterol, m/z 429.4091 | ND | ND | N/A | ||

| 41 | 14-CDO dihydrolanosterol, m/z 444.3946 | 426.3843 | 1.9 × 104 | 426.3834 | 7.6 × 104 | 4.0 |

| 42 | FF-MAS, m/z 413.3778 | ND | 395.3663 | 7.2 × 104 | N/A | |

| 43 | β-Sitosterol, m/z 415.3934 | ND | ND | N/A | ||

| 44 | Ergosterol, m/z 397.3465 | ND | ND | N/A | ||

| Pregnenolone derivatives | ||||||

| 16 | Pregnenolone, m/z 317.2475 | 299.2369 | 8.1 × 105 | 317.2459 | 1.0 × 105 | 0.1 |

| 17 | 3-OAc pregnenolone, m/z 359.2581 | 357.2421 | 7.3 × 105 | ND | N/A | |

| 18 | Dehydroepiandosterone, m/z 289.2162 | 271.2061 | 3.9 × 105 | 289.2142 | 4.2 × 104 | 0.1 |

| 31 | 17α-OH pregnenolone, m/z 331.2268 | ND | ND | N/A | ||

| Progesterone derivatives | ||||||

| 22 | Algestone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2222 | 7.7 × 106 | 347.2194 | 3.1 × 107 | 4.0 |

| 23 | 11-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2267 | 1.9 × 107 | 331.2254 | 6.8 × 107 | 3.6 |

| 24 | 17α-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2272 | 3.4 × 107 | 331.2256 | 8.9 × 107 | 2.6 |

| 39 | Progesterone, m/z 315.2319 | 315.2327 | 4.0 × 107 | 315.2305 | 1.1 × 108 | 2.8 |

| Glucocorticoid | ||||||

| 25 | Hydrocortisone, m/z 363.2166 | 363.2172 | 1.3 × 107 | 363.2143 | 4.6 × 107 | 3.5 |

| Mineralocorticoid derivatives | ||||||

| 19 | 21-OH progesterone, m/z 331.2268 | 331.2273 | 2.0 × 107 | 331.2258 | 5.9 × 107 | 3.0 |

| 20 | 21-OAc progesterone, m/z 373.2373 | 373.2378 | 3.9 × 107 | 373.2351 | 1.1 × 108 | 2.8 |

| 21 | Aldosterone, m/z 361.2010 | 343.1906 | 9.1 × 106 | 343.1887 | 2.1 × 107 | 2.3 |

| 26 | 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 335.2581 | 333.2432 | 3.5 × 105 | 333.2405 | 6.0 × 105 | 1.7 |

| 27 | [3,20-d 2] 3β-OH-preg-5-ene-20,21-diol, m/z 337.2706 | 334.2488 | 4.4 × 105 | 301.2481 | 2.1 × 106 | 4.8 |

| 38 | Corticosterone, m/z 347.2217 | 347.2223 | 6.0 × 106 | 347.2207 | 2.9 × 107 | 4.8 |

| Miscellaneous steroids | ||||||

| 28 | 3-Keto-4-etiocholenic acid, m/z 317.2111 | 317.2119 | 2.2 × 107 | 317.2100 | 7.5 × 107 | 3.4 |

| 29 | Etienic acid, m/z 319.2268 | 301.2162 | 2.2 × 105 | 317.2098 | 9.7 × 104 | 0.4 |

| 30 | 24-Bisnor-5-cholenic acid-3β-ol, m/z 347.2581 | 329.2477 | 4.8 × 105 | 329.2458 | 7.7 × 104 | 0.2 |

| 34 | Androst-5-ene-3β,17-diol, m/z 291.2319 | 273.2211 | 4.6 × 105 | 291.2306 | 2.0 × 105 | 0.4 |

| 35 | 17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 305.2475 | 287.2372 | 5.9 × 105 | 269.2256 | 1.7 × 106 | 2.9 |

| 36 | d2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 307.2601 | 289.2497 | 3.0 × 105 | 289.2480 | 1.7 × 104 | 0.06 |

| 37 | 17β-Formyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, m/z 303.2319 | 301.2166 | 1.9 × 106 | 285.2201 | 1.8 × 106 | 0.9 |

Values recorded in plain text were determined at 100 μM steroid concentration, while values in bolded text were determined at 500 μM (i.e., 10 μL injected = 1 or 5 nmol). Ions denoted with an asterisk (*) are NH4 + adducts. ND: not detected (response <1 × 104). N/A: not applicable.

The use of ESI– MS has been reported to increase the detection sensitivity of estrogens and acidic steroids. − For estrogen analysis, the use of a basic mobile phase (e.g., supplemented with NH4OH) can facilitate deprotonation of the phenolic hydroxyl moiety for ESI– analysis, though significant ESI–sensitivity gains have been reported using NH4F. − We tested whether the NH4F (0.3 mM) mobile phase facilitated HESI– analysis of estrogens (1–3) and three acidic steroids (28–30) and observed mixed results. The ratio of base peak intensity (HESI– /HESI+, both conducted in the NH4F (0.3 mM) mobile phase) was 77 (1), 10 (2), and 0.8 (3) for the estrogens and 0.4 (28), 66 (29), and 95 (30) for three analyzed carboxy-steroids (Supporting Figures S48–S53). HESI– was optimal for two estrogens (1 and 2) and two carboxy-steroids (29 and 30) but was roughly equally sensitive for one molecule in each class (3 and 28), though the effect was observed to vary >100-fold among the three molecules in each class.

Discussion

A variety of MS-based approaches have been used in the detection and quantification of steroids and sterols over the past 60 years. Early work predating the advent of electrospray ESI-MS employed electron impact GC-MS, ,, while more recent methods utilize ESI or APCI (MS) approaches, in many cases involving a tandem (MS/MS) approach. Recently, HESI MS has been reported to be more useful than standard ESI MS for steroids. , Some investigators have instead relied on chemical derivatization to increase sensitivity (i.e., dansyl chloride or hydroxylamine), while others have found that careful selection of the mobile phase additive (i.e., NH4OH, NH4F, or NH4OAc) can give comparable or enhanced sensitivity relative to chemical derivatization. In our own experience, steroid/sterol sensitivity has been significantly enhanced with chemical (dansyl) derivatization, ,, which is practical with a subset of steroids (those bearing carbonyl moieties).

We compared the detection sensitivity of 44 steroids using both APCI+ and ESI+ MS approaches (Table ). Δ4 steroids generally performed best on ESI+ (up to a maximum factor of 7.8-fold), while Δ5 steroids and sterols generally performed better on APCI+ (up to a maximum factor of >137-fold), except for two trihydroxypregnanes (26, 27). Estrogens did not show a clear trend, demonstrating either minimal difference or substantial preference for APCI (by a factor of 0.2–14-fold). We, like others, observed a general increase in sensitivity with the use of NH4F as a mobile phase additive for ESI+ MS, with the exception of some Δ5 steroids (Table ), as well as gains in ESI– MS for some estrogens and acidic steroids (1, 2, 29, 30). −

While we did not compare the effect of this mobile phase on APCI-MS, another group has reported significant sensitivity increases with a very high NH4F concentration (1 M) in an SFC-APCI MS approach. These higher concentrations were necessary in APCI MS analyses, but lower concentrations were optimal in the ESI MS approach (1 mM). This level compares to LC-ESI MS approaches, where a similarly lower additive concentration (6 mM) has been used (in our own approach we used 0.3 mM). We cannot exclude the possibility that the sensitivity gain from the NH4F additive would increase at higher concentrations.

While we often observed that APCI generated more ions than HESI (generally as 2n or 18n amu losses, Figure ), the sensitivity advantage of HESI over APCI that was observed for many steroids is not inherently due to this effect (i.e., that HESI generated fewer more intense ions while APCI generated more ions with lower intensity, thus “diluting” the signal). Rather, examples with the mineralocorticoids (e.g., corticosterone (38), Table ) often revealed the same base peak generated from both methods with roughly the same ions but with an increase in base peak signal in HESI MS analysis. Further, the trend was maintained by summing the intensities of the ions in Table (generating a figure for the total ion intensity) for each method, confirming the effect.

In the course of our sterol analysis with APCI MS, we previously observed 2n amu losses but did not give much attention to the matter. In fact, this phenomenon was evidently present in some of our earlier APCI work with OH-androgens to varying degrees, e.g., 6β-OH testosterone. We did not, however, see any evidence for this phenomenon for 1β-OH testosterone using a time-of-flight instrument (200 °C). More recently, discordance in structural assignments between NMR and m/z spectra in our synthetic work with oxysterols caused us to consider this phenomenon more seriously, in that dominant 2n amu losses on NaBH4-treated sterols were initially mistaken as the precursor ion MH+ of the starting material (rather than MH+-2 of the product), causing ambiguity as to whether the reduction (which had supposedly gone to completion, per the NMR spectrum) was successful (Scheme ).

A total of 36 of the 44 tested sterols showed losses of 2n amu in APCI MS analysis (17/22 Δ5 steroids, 17/19 Δ4 steroids, and 2/3 estrogens). These losses were prominent ions in most cases but were especially dominant in the Δ5 steroids and sterols, in which the precursor MH+ was either observed as a minor ion or (more frequently) not detected at all, constituting the base peak in 7/22 cases (Figure ). These results compare to HESI MS, in which 2n amu losses were detected (generally weakly) in 9/44 cases but constituted the base peak in 3/9 of those. The nature of these losses was confirmed via the analysis of a deuterated steroid. When d 0-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (35) was deuterated (d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol, 36, Figure A), the prominent ion distribution shifted from MH+-2, MH+-4, and MH+-6 (d 0, Figure B) to MH+-2, MH+-5, and MH+-7 (d 2, Figure C). The presence of MH+-3 or MH+-5 ions was rarely observed in our APCI analysis of steroids, except for with deuterated steroids. The prominence of the MH+-5 ion in d 2-17β-OH methyl-Δ5-androstene-3β-ol (36) confirmed that 2-electron oxidations observed in APCI MS analysis can be attributed to carbinol oxidations, in that deuterium could only be lost at C-17, and the dominance of the MH+-2 ion may suggest that a single 2-electron oxidation may be most prevalent at C-3, potentially owing to the increased stability of a C-3 ketone over an C-20 aldehyde.

One interesting observation was that some steroids showed 2n and 18n amu losses exceeding the number of available hydroxyl groups (i.e., that n > the number of −OH groups) suggesting that not every 2n loss could be explained by carbinol oxidation. Particularly interesting cases are the Δ4 steroids, some of which lack any available hydroxyl moiety (i.e., 4, 28, 32, 39) but show 2n losses. While these losses are generally minor peaks (maximum of 5–18% of the base peak intensity), they might be rationalized via a mechanism involving the loss of allylic hydride and thus generating a carbocation as has been suggested recently. In addition to a mechanism of carbinol oxidation and subsequent protonation of the carbonyl, the loss of allylic hydride presents an alternative mechanistic route to a positively charged ion detected as M+-H (mathematically equivalent to MH+-2H).

Our attempts to distinguish between the contributions of either mechanism began with reduction of the Δ5 bond of DHEA (to yield allo-DHEA), with the rationale being that if the formation of MH+-2n ions was dependent on the loss of allylic hydride, then elimination of the allylic site (via saturation of the Δ5 bond) should prevent the formation of MH+-2n ions. If such a mechanism was not present in our analyses, then allo-DHEA and DHEA would be expected to show very similar ion distributions (different m/z values, but similar patterns of MH+-2n and MH+-(n × H2O) ions). We observed that the ion distribution (of allo-DHEA) shifted in the direction of MH+-(n × H2O) and revealed the MH+ ion (relative to DHEA), and that the base peak was still a MH+-2n ion (Supporting Figure S45). As reduction of the Δ5 bond did not preclude the formation of MH+-2n ions but significantly shifted the ion distribution toward alternative ionization mechanisms (generation of MH+-(n × H2O) and MH+ ions), a mechanism involving loss of allylic hydride is likely present in addition to carbinol oxidation in the generation of MH+-2n ions in our APCI analyses, i.e., the relative contribution of the allylic hydride mechanism to ionization in DHEA was diverted to alternative ionization mechanisms in allo-DHEA, detected as a significant increase in the proportion of MH+-(n × H2O) ions observed. Given the retained prominence of the MH+-2n ions, we consider that the contribution of an allylic hydride loss mechanism is likely minor in relation to the carbinol oxidation mechanism. We again note the presence of several steroids (i.e., 4, 28, 32, 39) in our analysis that did not have any carbinol moieties in their structures but still demonstrated significant MH+-2n ions, an ion which is perhaps best rationalized via a loss of allylic hydride mechanism.

Further efforts to characterize the MH+-2 ions were conducted using targeted LC-MS/MS fragmentation analysis of compound 37, which demonstrated prominent MH+-2 ions in untargeted analyses in both APCI+ and HESI+ MS (Supporting Figure S37). MS/MS fragmentation of the MH+-2 ion revealed identical MH+-(n × H2O)-2 product ions in both techniques (Supporting Figure S46), suggesting the precursor MH+-2 ion is the same. However, if the route to the MH+-2 precursor ion was a carbinol oxidation mechanism, the loss of H2O from this ion in the MS/MS fragmentation spectrum is initially difficult to rationalize, as no carbinol is left in the molecule to protonate and leave (as H2O) to generate this ion. We considered progesterone (39), which lacks a carbinol moiety, and collected MS/MS spectra of the precursor MH+ ion, which revealed a product ion (base peak) of MH+-H2O in the MS/MS fragmentation spectrum (Supporting Figure S46). Thus, the generation of MH+-(n × H2O) ions is not dependent on the availability of hydroxyl moieties in the molecular structure, and the observation of a MH+-H2O-2 product ion in the fragmentation MS/MS spectrum of 37 does not contradict our carbinol oxidation mechanism, i.e., a MH+-2 precursor ion resulting from carbinol oxidation of 37 could still lose H2O to generate product ions of MH+-H2O-2 (as we observed) without bearing a carbinol.

In total, we consider that carbinol oxidation is likely a dominant mechanism in the generation of MH+-2 ions, with a minor contribution of allylic hydride loss.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the analysis of Δ4 steroids was generally optimal with HESI+ MS, while APCI+ MS was often advantageous for Δ5 steroids, with some exceptions. The sensitivity difference rarely exceeded 3-fold in either direction, though sensitivity on HESI+ could often be enhanced with the use of NH4F as a mobile phase additive (though rarely by a factor >4-fold). The detection of sterols (also Δ5 structures), however, was substantially improved with APCI+ MS, though analyses with APCI+ often generated additional ions (generally −2n amu losses) that dominated the m/z spectrum. While 2n amu losses were also observed in HESI+ analysis (in 9/44 steroids/sterols), they were most prominent (and problematic) in APCI+ analyses (36/44 steroids/sterols). We attribute these losses largely to a carbinol oxidation mechanism, although we provide evidence that loss of allylic hydride is an alternative mechanism, likely minor in contribution, that is also capable of generating these ions. These artifacts may complicate accurate structure assignment, particularly when the precursor ion MH+ is observed as a minor or absent ion. In the case of dominant 2n amu losses, the MH+-18n (loss of n × H2O) ion generally provides a reliable point of reference for structure determination.

Taken together, we present a general guide for conducting LC-MS analyses of the steroid family of molecules, guided by two main properties: (i) Δ5 vs Δ4 conjugation and (ii) steroid vs sterol. A steroid of Δ4 conjugation was generally most sensitively analyzed by HESI-MS complemented by a NH4F (0.3 mM) mobile phase additive, while one of Δ5 conjugation was generally optimal via APCI-MS (though the advantage was frequently ≤2-fold). Given that APCI-MS typically generates a pattern of MH+-2n ions that is not frequently observed in HESI-MS, the latter method is suitable for structure elucidation with a minimal loss of sensitivity, which may be necessary in steroid synthesis. Note that the HESI-MS of Δ5 steroids should generally exclude the NH4F mobile phase additive, which frequently compromised the sensitivity. For sterols (all of Δ5 conjugation), APCI-MS was a general necessity, in that many sterols were not detected by HESI-MS, although this effect was much less pronounced with some oxysterols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Tateishi for obtaining preliminary APCI+ spectra for some of the steroids and NMR spectra. We also thank M. W. Calcutt, S. Chetyrkin, and B. Hachey of the Vanderbilt University Mass Spectrometry Core for technical assistance and K. Trisler for assistance in the preparation of parts of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant R35 GM151905 (to F.P.G.). This material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. 1937963 (K.D.M.).

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jasms.5c00099.

APCI and HESI UPLC chromatograms and spectra of all analyzed steroids (PDF)

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Whitehouse C. M., Dreyer R. N., Yamashita M., Fenn J. B.. Electrospray Interface for Liquid Chromatographs and Mass Spectrometers. Anal. Chem. 1985;57(3):675–679. doi: 10.1021/ac00280a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwemer T., Rüger C. P., Sklorz M., Zimmermann R.. Gas Chromatography Coupled to Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry for Improvement of Data Reliability. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(24):11957–11961. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzikiewicz H., Djerassi C.. Mass Spectrometry in Structural and Stereochemical Problems. I. Steroid Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962;84(8):1430–1439. doi: 10.1021/ja00867a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K., Ochiai N., Higashi N., Dunkle M., Sasamoto K., Tienpont B., David F., Sandra P.. Gas Chromatography with Soft Ionization Mass Spectrometry for the Characterization of Natural Products. LCGC Eur. 2013;26(10):548–546. [Google Scholar]

- Barricklow J., Ryder T. F., Furlong M. T.. Quantitative Interference by Cysteine and N-Acetylcysteine Metabolites During the LC-MS/MS Bioanalysis of a Small Molecule. Drug Metab. Lett. 2009;3(3):181–190. doi: 10.2174/187231209789352148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Eberlin M. N., Corilo Y. E., Liu D. Q., Yin H.. Dimerization of Ionized 4-(Methylmercapto)-phenol During ESI, APCI and APPI Mass Spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009;44(9):1389–1394. doi: 10.1002/jms.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrton S. T., Jones R., Douce D. S., Morris M. R., Cooks R. G.. Uncatalyzed, Regioselective Oxidation of Saturated Hydrocarbons in an Ambient Corona Discharge. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57(3):769–773. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz C., Madry M. M., Kraemer T., Baumgartner M. R.. LC-MS-MS Analysis of Δ9-THC, CBN and CBD in Hair: Investigation of Artifacts. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2022;46(5):504–511. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkab056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Neta P., Yang X., Garraffo H. M., Bukhari T. H., Liu Y., Stein S. E.. Molecular Oxygen (O2) Artifacts in Tandem Mass Spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025;36(1):85–90. doi: 10.1021/jasms.4c00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty K. D., Sullivan M. E., Tateishi Y., Hargrove T. Y., Lepesheva G. I., Guengerich F. P.. Processive Kinetics in the Three-Step Lanosterol 14α-Demethylation Reaction Catalyzed by Human Cytochrome P450 51A1. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;299(7):104841. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty K. D., Liu L., Tateishi Y., Wapshott-Stehli H. L., Guengerich F. P.. The Multistep Oxidation of Cholesterol to Pregnenolone by Human Cytochrome P450 11A1 is Highly Processive. J. Biol. Chem. 2024;300(1):105495. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty K. D., Tateishi Y., Hargrove T. Y., Lepesheva G. I., Guengerich F. P.. Oxygen-18 Labeling Reveals a Mixed Fe-O Mechanism in the Last Step of Cytochrome P450 51 Sterol 14α-Demethylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024;63(9):e20231771. doi: 10.1002/anie.202317711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Guengerich F. P.. Dansylation of Unactivated Alcohols for Improved Mass Spectral Sensitivity and Application to Analysis of Cytochrome P450 Oxidation Products in Tissue Extracts. Anal. Chem. 2010;82(18):7706–7712. doi: 10.1021/ac1015497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto F. K., Guengerich F. P.. Mechanism of the Third Oxidative Step in the Conversion of Androgens to Estrogens by Cytochrome P450 19A1 Steroid Aromatase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(42):15016–15025. doi: 10.1021/ja508185d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P., McCarty K. D., Chapman J. G., Tateishi Y.. Stepwise Binding of Inhibitors to Human Cytochrome P450 17A1 and Rapid Kinetics of Inhibition of Androgen Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297(2):100969. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P., Tateishi Y., McCarty K. D., Liu L.. Steroid 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-Lyase (Cytochrome P450 17A1) Methods Enzymol. 2023;689:39–63. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieser, L. F. ; Fieser, M. . Reagents for Organic Synthesis, Vol. 1; Wiley: New York, NY, 1967; pp 581–595, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Dess D. B., Martin J. C.. Readily Accessible 12-I-5 Oxidant for the Conversion of Primary and Secondary Alcohols to Aldehydes and Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48(22):4155–4156. doi: 10.1021/jo00170a070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Saiki K., Watanabe F.. Characteristics of Mass Fragmentation of Steroids by Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization-Mass Spectrometry. Biol. Pharmaceut. Bull. 1993;16(11):1175–1178. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.-C., Kim H.-Y.. Determination of Steroids by Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1997;8(9):1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(97)00122-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers A., Ringold H. J.. Steroids. CXI. Studies in Nitro Steroids. Part 3. The Synthesis of 21-Nitroprogesterone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81(14):3710–3712. doi: 10.1021/ja01523a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miescher K., Hunziker F., Wettstein A.. 47. Über Steroide. Homologe der Keimdrüsenhormone II. 20-Nor-progesteron. Helv. Chem. Acta. 1940;23:400–404. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19400230149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauser J. A., Guengerich F. P.. Cytochrome P450 3A4-catalyzed Testosterone 6β-Hydroxylation: Stereochemistry, Kinetic Deuterium Isotope Effects, and Rate-Limiting Steps. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(20):19496–19506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkyo R., Guengerich F. P.. Cytochrome P450 7A1 Cholesterol 7α-Hydroxylation: Individual Reaction Steps in the Catalytic Cycle and Rate-Limiting Ferric Iron Reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(6):4632–4643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkyo R., Xu L., Tallman K. A., Cheng Q., Porter N. A., Guengerich F. P.. Conversion of 7-Dehydrocholesterol to 7-Ketocholesterol is Catalyzed by Human Cytochrome P450 7A1 and Occurs by Direct Oxidation Without an Epoxide Intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(38):33021–3308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramlinger V. M., Nagy L. D., Fujiwara R., Johnson K. M., Phan T. T., Xiao Y., Enright J. M., Toomey M. B., Corbo J. C., Guengerich F. P.. Human Cytochrome P450 27C1 Catalyzes 3,4-Desaturation of Retinoids. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(9):1304–1312. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. M., Phan T. T. N., Albertolle M. E., Guengerich F. P.. Human Mitochondrial Cytochrome P450 27C1 is Localized in Skin and Preferentially Desaturates trans-Retinol to 3,4-Dehydroretinol. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292(33):13672–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.773937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass S. M., Tateishi Y., Guengerich F. P., Wang H. J.. 3,4-Desaturation of Retinoic Acids by Cytochrome P450 27C1 Prevents P450-Mediated Catabolism. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023;743:109669. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2023.109669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass S. M., Guengerich F. P.. Cellular Retinoid-Binding Proteins Transfer Retinoids to Human Cytochrome P450 27C1 for Desaturation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297(4):101142. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi Y., McCarty K. D., Martin M. V., Yoshimoto F. K., Guengerich F. P.. Roles of Ferric Peroxide Anion Intermediates (Fe3+O2 –, Compound 0) in Cytochrome P450 19A1 Steroid Aromatization and a Cytochrome P450 2B4 Secosteroid Oxidation Model. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024;63(33):e202406542. doi: 10.1002/anie.202406542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi J. L., Zahra P., Vine J. H., Whittem T.. Determination of Testosterone Esters in the Hair of Male Greyhound Dogs using Liquid Chromatography–High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Drug Testing Anal. 2018;10(3):460–473. doi: 10.1002/dta.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Gardinali P. R.. Comparison of Multiple API Techniques for the Simultaneous Detection of Microconstituents in Water by On-Line SPE-LC-MS/MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2012;47(10):1255–1268. doi: 10.1002/jms.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela K., Arman H. D., Yoshimoto F. K.. Synthesis of [3,3-2H2]-Dihydroartemisinic Acid to Measure the Rate of Nonenzymatic Conversion of Dihydroartemisinic Acid to Artemisinin. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83(1):66–78. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comin M. J., Elhalem E., Rodriguez J. B.. Cerium Ammonium Nitrate: A New Catalyst for Regioselective Protection of Glycols. Tetrahedron. 2004;60(51):11851–11860. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2004.09.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parr M. K., Wüst B., Teubel J., Joseph J. F.. Splitless Hyphenation of SFC with MS by APCI, APPI, and ESI Exemplified by Steroids as Model Compounds. J. Chromatogr. B. 2018;1091:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden J. R., Ames D. M.. Assessment of Ammonium Fluoride as a Mobile Phase Additive for Sensitivity Gains in Electrospray Ionization. Anal. Sci. Advances. 2023;4(11–12):347–354. doi: 10.1002/ansa.202300031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer L., Shaheen F., Gilligan L. C., Storbeck K. H., Hawley J. M., Keevil B. G., Arlt W., Taylor A. E.. Multi-steroid Profiling by UHPLC-MS/MS with Post-column Infusion of Ammonium Fluoride. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2022;1209:123413. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2022.123413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue S. W., Winchell A. J., Kaucher A. V., Lieberman R. A., Gilles C. T., Pyra M. N., Heffron R., Hou X., Coombs R. W., Nanda K., Davis N. L., Kourtis A. P., Herbeck J. T., Baeten J. M., Lingappa J. R., Erikson D. W.. Simultaneous Quantitation of Multiple Contraceptive Hormones in Human Serum by LC-MS/MS. Contraception. 2018;97(4):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen L. J., Wu F. C., Keevil B. G.. A Rapid Direct Assay for the Routine Measurement of Oestradiol and Oestrone by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2014;51(3):360–367. doi: 10.1177/0004563213501478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannulu N. S., Cole R. B.. Novel Fragmentation Pathways of Anionic Adducts of Steroids Formed by Electrospray Anion Attachment Involving Regioselective Attachment, Regiospecific Decompositions, Charge-Induced Pathways, and Ion–Dipole Complex Intermediates. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(9):1558–1568. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0422-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djerassi C., Wilson J. M., Budzikiewicz H., Chamberlin J. W.. Mass Spectrometry in Structural and Stereochemical Problems. XIV. Steroids with One or Two Aromatic Rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962;84(23):4544–4552. doi: 10.1021/ja00882a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. H., Buchanan B. G., Engelmore R. S., Duffield A. M., Yeo A., Feigenbaum E. A., Lederberg J., Djerassi C.. Applications of Artificial Intelligence for Chemical Inference. VIII. Approach to the Computer Interpretation of the High Resolution Mass Spectra of Complex Molecules. Structure Elucidation of Estrogenic Steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94(17):5962–5971. doi: 10.1021/ja00772a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabi K., Sleno L.. Estradiol, Estrone and Ethinyl Estradiol Metabolism Studied by High Resolution LC-MS/MS Using Stable Isotope Labeling and Trapping of Reactive Metabolites. Metabolites. 2022;12(10):931. doi: 10.3390/metabo12100931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitku J., Horackova L., Kolatorova L., Duskova M., Skodova T., Simkova M.. Derivatized versus Non-derivatized LC-MS/MS Techniques for the Analysis of Estrogens and Estrogen-Like Endocrine Disruptors in Human Plasma. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety. 2023;260:115083. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häkkinen M. R., Murtola T., Voutilainen R., Poutanen M., Linnanen T., Koskivuori J., Lakka T., Jääskeläinen J., Auriola S.. Simultaneous analysis by LC-MS/MS of 22 ketosteroids with hydroxylamine derivatization and underivatized estradiol from human plasma, serum and prostate tissue. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 2019;164:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauser J. A., Voehler M., Tseng L. H., Schefer A. B., Godejohann M., Guengerich F. P.. Testosterone 1β-hydroxylation by human cytochrome P450 3A4. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271(19):3962–3969. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.