Abstract

Photoactive CrIII complexes are typically based on polypyridine coordination environments, exhibit red luminescence, and are good photo-oxidants but have modest photoreducing properties. We report new CrIII complexes with anionic chelate ligands that enable color-tunable near-infrared luminescence and red-light-driven photoreduction reactions involving elementary steps that are endergonic up to 0.5 eV. Improving the metal–ligand bond covalency rather than more established approaches such as optimizing ligand field strength and coordination geometry is the underlying molecular design concept to achieve this favorable behavior. Our analysis suggests an intricate interplay between productive but slow endergonic photoinduced electron transfer and energy-wasting charge recombination rooted in cage escape effects, which could be generally important for photocatalysis. Our work also suggests the occurrence of doublet–doublet annihilation, a process that seems to have been largely neglected in current research on photoactive CrIII complexes but which could provide a mechanistic entry point into the widely used process of photochemical upconversion, typically based on triplet–triplet annihilation. Overall, this work conceptually advances the current state of the art of photoactive CrIII complexes in terms of molecular design, luminescence, and photoredox behavior. More generally, it informs photochemistry in terms of elucidating the limits of light-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency and the value of long-lived excited states in complexes of earth-abundant transition metals.

Introduction

Research on molecular coordination complexes for luminescence and photoinduced electron and energy transfer has focused on second- and third-row transition metals for decades, but the first-row transition metal CrIII was recognized as an interesting alternative, nearly 50 years ago. With the recent surge of interest in replacing rare and precious metal elements with more abundant ones, CrIII complexes have experienced a revival that was initiated by the development of the so-called molecular rubies, which are made of new, bite-angle-optimized variants of the well-known polypyridine family of chelate ligands. , Molecular rubies exhibit greatly improved photoluminescence properties and extended excited state lifetimes, but their 6-fold pyridine ligand environments are analogous to those used in some of the early CrIII examples. This limitation in molecular design limits the photophysical and photochemical properties, exemplified by the finding that most CrIII polypyridines luminesce in a narrow wavelength range between 720 and 780 nm and that most of them are strong photo-oxidants but weak photoreductants. ,

We have shown that a fundamentally different molecular design based on anionic ligands allows for near-infrared (NIR) CrIII luminescence beyond 1000 nm and drastically altered electronic structures that are promising for photochemical applications. Our approach was conceptually different from the previous strategies because it focused on tuning the metal–ligand bond covalency rather than on maximizing the ligand field strength. Several subsequent studies adopted our conceptual approach and reported CrIII complexes emitting in the near-infrared spectral region, many with better properties than we originally reported. − Recent work on complexes with other first-row transition metals has provided further evidence for the importance of metal–ligand bond covalency in the molecular design of photoactive complexes. ,

It now seems clear that both design approaches, the traditional approach of creating strong ligand fields and the less conventional approach of optimizing metal–ligand bond covalency, have their inherent limitations. The two approaches are in principle complementary and would ideally be applied simultaneously, but the molecular design factors that affect the ligand field strength usually also affect the metal–ligand bond covalency, and vice versa. Consequently, it is very difficult to optimize everything at once, but we reasoned that work in this direction likely needs to explore a larger chemical space than the well-established polypyridine coordination environments for CrIII. For other first-row transition metals, the evolution to carbene and isocyanide ligands has led to conceptual advances that would have been very difficult to achieve with polypyridines, for example with Cr0, MnIV, , FeII/III, , CoIII, and NiII. ,

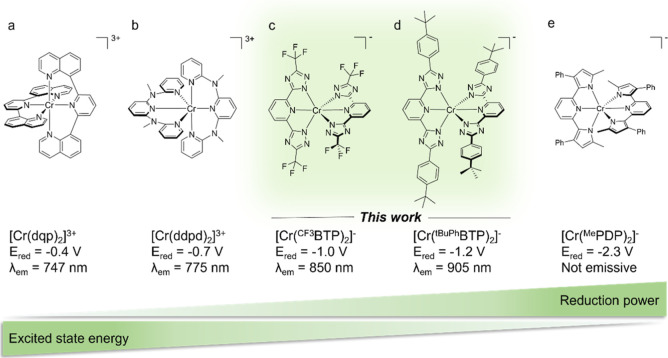

With this in mind and with an eye toward more exploratory and perhaps drastic changes in the electronic structures and properties of photoactive CrIII complexes, we identified the tridentate bis (1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)pyridine (RBTP) ligand framework as potentially interesting (Figure c,d). − Compared to benchmark molecular rubies (Figure a,b), , our CrIII complexes exhibit emissions with band maxima (λem) in the near-infrared spectral region beyond 800 nm, and they are significantly more electron-rich, as manifested by their one-electron reduction potentials (E red) comparable to that of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine). Our [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− complexes in Figure c,d represent an attempt to explore uncharted territory between the electron-deficient, strongly red-emissive molecular rubies (Figure a,b) and the very electron-rich but nonluminescent CrIII complexes (Figure e).

1.

Molecular structures and key electrochemical and photophysical properties of relevant published and new CrIII complexes. The electron-deficient and strongly red luminescent (a) [Cr(dqp)2]3+ and (b) [Cr(ddpd)2]3+, for which ligand field strength and optimized coordination geometry were key design criteria. The new electron-rich near-infrared luminescent [Cr(RBTP)2]− complexes (c,d), with greater metal–ligand bond covalency as a key molecular design concept (R = CF3 or tBuPh). Nonluminescent [Cr(MePDP)2]− complex (e). E red is the electrochemical potential for one-electron reduction in V vs SCE, λem is the emission band maximum in solution at room temperature.

Our molecular design allows for color-tunable near-infrared luminescence at room temperature due to a balance between ligand field strength and metal–ligand bond covalency and also provides access to an unusual photochemistry for CrIII complexes, where photoreduction reactions become possible instead of the more commonly studied photo-oxidations. ,− This molecular design also represents a compromise between lowered excited state energies and consequent accelerated (nonradiative) excited state decay, a common dilemma in photophysics. , The compromise achieved here makes photoinduced electron transfer steps that are endergonic up to 0.5 eV kinetically competitive with the inherent excited state decay, allowing us to explore and extend the current kinetic and thermodynamic limits of CrIII photochemistry. Based on the results obtained, we gain insight into the trade-offs between slow, endergonic, and fast, exergonic photoinduced electron transfer elementary steps, allowing us to discuss generally relevant design concepts for photochemistry to optimize the interplay between energy-storing and energy-wasting processes. We also observe evidence of second-order processes that arise from either doublet–doublet annihilation or excited-state disproportionation. These possibilities have been largely overlooked in modern CrIII photophysics and photochemistry, possibly due to the electrostatic repulsion between the highly charged CrIII complexes typically studied. While these processes are currently energy-wasting, they hold the potential to be harnessed for efficient light conversion in the future.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Aspects of Anionic Complexes with a High Metal–Ligand Binding Covalency

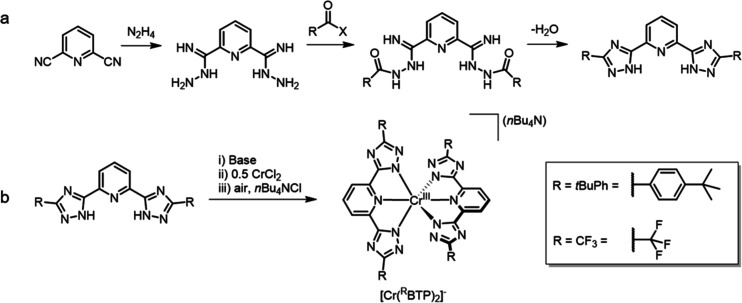

The RBTP ligands were synthesized through straightforward multistep procedures (Figure a). − The reaction between pyridine-2,6-dicarbonitrile and hydrazine yielded a bis(carboximidhydrazide), which then underwent amide coupling in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid, 4-tert-butylbenzoyl chloride, or 4-tert-butylbenzoic acid. Subsequent dehydration and cyclization at high temperatures produced trifluoromethyl (CF3BTP) and (tert-butyl)phenyl ( tBuPhBTP) derivatives, respectively. The CrIII complexes (hereby abbreviated as [Cr(RBTP)2]−) were prepared by first deprotonating the BTP ligands, followed by chelation of CrII and oxidation under air. The direct use of CrIII salts (i.e., CrCl3·3THF) proved ineffective. Cation exchange with tetra-n-butylammonium (nBu4N+) ensured solubility of the complexes in organic solvents such as DCM and MeCN, yielding (nBu4N)[Cr(CF3BTP)2] and (nBu4N)[Cr( tBuPhBTP)2] (Figure b).

2.

(a) Synthesis of the bis(1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)pyridine (RBTP) ligands, where R is either a (tert-butyl)phenyl (tBuPh) or a trifluoromethyl (CF3) group. X = Cl or OH in the case of R = tBuPh, and X = OH in the case of R = CF3. (b) Synthesis of the [Cr(RBTP)2]− complexes.

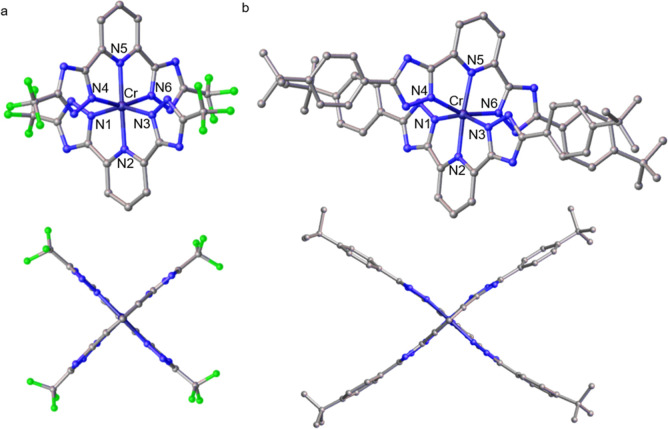

The single-crystal X-ray structures of [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (Figure a) and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (Figure b) confirm a distorted octahedral coordination geometry. For [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−, the average bond distance between the metal and the coordinating nitrogen atoms is 2.029 Å, with the CrIII–N bonds of the anionic triazole groups being almost the same length as the axial CrIII–N bonds of the pyridine units. On the other hand, for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, the average bond distance between CrIII and the anionic triazole groups is 2.047 Å, which is 0.04 Å longer than the axial CrIII–N bonds of the pyridine units. This difference is evident in the computed parameter Δ (eq S1), which accounts for the average deviation in ligand–metal bond lengths. Δ is only 1.8 × 10–5 for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− but it increases to 2.8 × 10–4 in [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−. For comparison, the Cr–N bond distances in [Cr(bpy)3]3+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) and [Cr(NH3)6]3+ lie in the range of 2.04–2.05 Å and 2.06 Å, respectively, and the Δ parameters of these complexes are 5.6 × 10–5 and 2.8 × 10–5. An even more pronounced distortion from the ideal octahedral geometry is observed when considering the bond angles. The angles formed between the pyridine nitrogen (N5), the metal center, and the triazole nitrogen (N4) of the same ligand are 77.4° for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and 77.8° for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−. When the triazole nitrogens from the two different coordinated ligands are considered (N3 instead of N4), the N5–CrIII–N3 angle measures around 102° for both complexes. These values deviate significantly from the ideal angle found in the nearly perfectly octahedrally shaped [Cr(NH3)6]3+ complex (89.7°). Closer similarities are observed in [Cr(tpy)2]3+ (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine), where the chelate angle between adjacent pyridines and the metal center falls within the 77.4–79.59° range. , The distortion from the ideal 90° cis bond angles is captured by the parameter Σ (eq S2), which is approximately 107° for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−, 114° for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, and 122° for [Cr(tpy)2]3+, but only 18° for [Cr(NH3)6]3+ and 67° for [Cr(bpy)3]3+ (see Table S3).

3.

Solid-state X-ray crystal structure of (a) [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and (b) [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− viewed from two different angles. Disordered atoms, hydrogen atoms, and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity.

The distorted geometries of our new complexes are furthermore reflected in the octahedral distortion parameter Θ (eq S3), which is equal to 357° and 369° for the CF3 and the tBuPh derivatives, respectively, falling within the typical range for bis(tridentate) complexes. For example, [Cr(tpy)2]3+ shows a Θ value of 370° (see Supporting Information for further details). By contrast, [Cr(dqp)2]3+ and [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ exhibit lower Θ values of 105° and 122°, respectively, due to the greater flexibility of the ligands that allows for an improved octahedral symmetry. Monodentate complexes, which display the least distorted geometries, usually exhibit Θ values in the range of 50–75°. The N2–Cr–N5 angles of [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, which involve the apical pyridine nitrogens, are 178° and 174°, respectively, both close to the ideal linear arrangement. The dihedral angle between the planes of the two ligands in [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− is close to 90°. [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− exhibits deviations of up to 8% from a perfect right angle, and the ligands do not lie in perfectly defined planes, corroborating a more distorted geometry. Notably, the cross-shaped structure of both complexes provides limited shielding of the central CrIII ion despite the steric bulk of the ligands.

Shifting the Luminescence from the Red to the Near-Infrared Range and Fine-Tuning the Energy of the Photoactive Excited State

For CrIII in coordination environments that can be approximated as octahedral and in strong ligand fields, the lowest electronically excited state is one in which an electron spin has been flipped, but the orbital occupancy is otherwise the same as in the ground state. The energy of this spin-flip excited state is independent of the ligand field strength, and therefore, conventional molecular design concepts are insufficient to tune CrIII luminescence over a significant wavelength range. , The concept of chelate bite angle optimization is highly successful in counteracting unwanted nonradiative relaxation of the emissive spin-flip excited state (in large part due to avoided thermal population of higher excited states from which nonradiative deactivation can easily occur), ,,,− but to directly influence the radiative spin-flip transition, it is less effective than changing the metal–ligand bond covalency. , A more drastic change than optimizing the coordination geometry of a polypyridine environment is therefore needed, even if this comes at the cost of a lower luminescence quantum yield. A classic approach to enhancing the metal–ligand bond covalency is to introduce anionic ligands, which we achieved here by using deprotonated triazole units integrated into a tridentate chelate ligand.

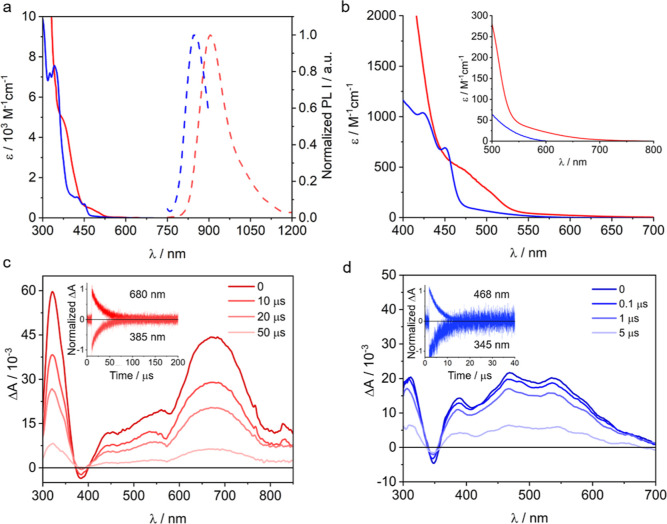

Further tuning of the electronic properties then is possible by varying the ligand’s chemical substituents: the inductive electron-withdrawing effect of CF3 leads to a blue shift in both absorption and emission bands compared to the more conjugated tert-butylphenyl (tBuPh) substituent. Both complexes absorb only weakly in the visible range, and the strongest bands are due to ligand-centered (LC) transitions occurring in the UV range (Figure a,b, solid traces). [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (red traces) shows an absorption band centered at 498 nm with a strong MC character according to DFT calculations and a band centered at 422 nm with mixed LC, charge-transfer (CT), and MC character. Similarly, [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (blue traces) has absorption bands between 425 and 452 that have a strong MC character. In the spectrum of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− a tailing of the absorption up to 700 nm is furthermore detectable (inset of Figure b), which is likely attributable to spin-forbidden LC transitions.

4.

(a) UV–vis absorption (solid traces) and emission (dashed traces) spectra of (nBu4N)[Cr(CF3BTP)2] (blue, λex = 350 nm) and (nBu4N)[Cr( tBuPhBTP)2] (red, λex = 300 nm). (b) Magnification of the absorption spectra between 400 and 800 nm. (c) Transient UV–vis absorption spectra at different delay times for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (40 μM, laser pump pulses at 355 nm, 30 mJ/pulse, and integration time of 1.5 μs). Inset: decay of the excited-state absorption (ESA) at 680 nm and recovery of the ground state bleach (GSB) at 385 nm. (d) Transient UV–vis absorption spectra at different delay times for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (40 μM, laser pump pulses at 355 nm, 30 mJ/pulse, integration time of 1.5 μs). Inset: decay of the ESA at 468 nm and recovery of the GSB at 345 nm. All measurements were performed in deoxygenated acetonitrile at room temperature.

Both complexes emit in the near-infrared (NIR) range in solution at room temperature (Figure a, dashed traces), with [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− displaying a maximum emission at 850 nm, while [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− emits at 905 nm, in both cases attributable to phosphorescence from the 2E and 2T1 states. Since it is difficult to assess the real nature of the emissive state, we will refer to both of them from now on. Moreover, the emission bandwidth (full width at half-maximum, fwhm, of 1900 cm–1) is atypical of spin-flip transitions, suggesting state mixing also with the ligand, as observed for other CrIII complexes with strong metal–ligand bond covalency. , Due to these comparably broad 2E/2T1 → 4A2 emission bands, the energy of the emissive doublet excited states can be underestimated if computed at the maxima. Therefore, we estimated the 2E/2T1 energies from the point on the short wavelength side of the emission spectra at which the intensity corresponds to 10% of the intensity reached at the maxima. This analysis yields 780 nm (corresponding to an energy of 1.59 eV for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−) and 820 nm (1.50 eV for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−), respectively. At 77 K, the luminescence of both complexes is blue-shifted by about 20–30 nm relative to 298 K (Figure S17), as reported earlier for other chromium(III) complexes. Technical limitations precluded the determination of the photoluminescence quantum yield of [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−, whereas for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− we determined a photoluminescence quantum yield of (0.10 ± 0.01)% in deoxygenated acetonitrile at room temperature (see Supporting Information for further details). For both complexes, the excitation spectra monitoring the NIR photoluminescence closely resemble the UV–vis absorption spectra (Figures S15 and S16), indicating near-unitary efficiency of photoactive state population upon absorption across all investigated wavelengths.

Evidently, the different chemical substituents on the triazole units have a substantial effect on the electron density at the CrIII center. This is noteworthy given previous findings that triazoles can exhibit a somewhat “insulating” character with respect to long-range electron transfer and can influence charge-transfer dynamics. , This opens up possibilities for exploring a broad range of other substitution patterns to fine-tune the properties of near-infrared emissive CrIII complexes, akin to strategies previously employed for photoactive complexes based on precious metals. −

Transient UV–vis absorption spectroscopy with nanosecond time resolution in deoxygenated acetonitrile revealed excited state absorptions (ESAs) over the entire visible range for both complexes, which were attributed to electronic transitions originating from the luminescent 2E/2T1 excited state (Figure c,d). For [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, an ESA band maximum at 680 nm and a ground state bleaching (GSB) at 385 nm are the most prominent spectral features (Figure c), while for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− an ESA band at 468 nm and a GSB at 345 nm are prominent (Figure d). Monitoring these ESA and GSB signals as a function of time yields excited state lifetimes of 23 μs for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and 5 μs for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−.

Balancing the Ligand Field Strength and the Metal–Ligand Bond Covalency

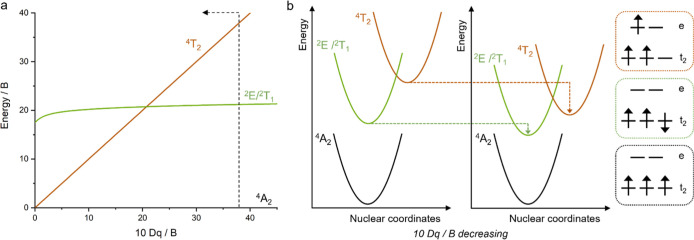

The electronic structures of octahedral d-metal complexes can be rationalized by the interplay between the ligand field strength (described by the ligand field parameter 10 Dq) and the metal–ligand bond covalency (captured by the Racah B parameter). The Tanabe–Sugano diagrams illustrate that interplay for all d-electron configurations, and the relevant d3 case for CrIII is shown in Figure a. Some of the best CrIII red luminophores based on coordination geometry optimized polypyridines have 10 Dq values near 25,000 cm–1 and B values around 660 cm–1, leading to a 10 Dq/B ratio near 38 in the specific case of [Cr(dqp)2]3+ (dqp = 2,6-bis(8′-quinolinyl)pyridine). The deprotonated triazoles of our RBTP chelates are π-donor ligands and are therefore expected to lead to a decrease in the 10 Dq value compared to polypyridine ligands. This in turn is expected to result in an energetic stabilization of the metal-centered 4T2 state (brown line in Figure a), which arises from an electronic transition from a t2 to an e orbital (Figure b, exemplary microstates on the far right), whereas the spin-flip 2E/2T1 excited state is expected to remain relatively unaffected by the decrease in 10 Dq.

5.

(a) Simplified Tanabe–Sugano diagram for an octahedral d3 configuration, with the 2E/2T1 spin-flip excited states (green) and the ligand field-dependent 4T2 excited state (brown) included, while all other states are not shown. The dashed vertical line represents the case of [Cr(dqp)2]3+, for which 10 Dq/B = 38. (b) Resulting shift of the potential energy surfaces of the states involved upon decreasing the 10 Dq/B ratio in the presence of π-donor anionic (deprotonated) triazole ligand units. The potential energy surfaces and some relevant microstates are marked in black (4A2, ground state), green (2E, spin-flip state), and brown (4T2, metal-centered state).

The Racah B parameter, which reflects the repulsion between individual d-electrons, decreases in the presence of ligands that form strong covalent bonds, such as amides, carbazolates, pyrrolates, and deprotonated triazoles. The resulting delocalization of d-electron density from the metal-based orbitals toward the ligands is known as the nephelauxetic effect and is characterized by the nephelauxetic parameter β, which is the ratio of the Racah B parameter of a given complex and the B value of the free Cr3+ ion in the gas phase. A decrease of the Racah B parameter can explain why the 2E photoluminescence red shifts by 1100–1800 cm–1 for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− with respect to a benchmark molecular ruby. Based on 2E energies of 12,820 cm–1 (780 nm) and 12,200 cm–1 (820 nm), and assuming a C/B ratio of 4.0 as in many textbooks (C is a second Racah parameter), we obtain B parameters of 660 and 630 cm–1 for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, respectively. However, the assumption of C/B = 4.0 seems somewhat ambiguous in light of recent studies on CoIII complexes, which have found C/B ratios that are considerably higher. The bottom line is that the resulting estimates of the Racah B parameters for our CrIII complexes are subject to considerable uncertainty. The resulting nephelauxetic parameters β are 0.69 and 0.66 for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, respectively. These values are lower than those of the champion polypyridine complex [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ (ddpd = N,N′-dimethyl-N,N′-dipyridine-2-yl-2,6-diamine), for which β = 0.80, indicating the expected greater degree of covalency with the deprotonated triazolate ligands.

Accurate determination of the 10 Dq values in our complexes is likewise challenging due to CT absorption bands that mask the weaker MC transitions and due to the admixture of CT character to some of our MC excited states (see above). Based on the DFT calculations mentioned above, the absorption band at 498 nm observed for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (Figure a,b) has a strong MC character and is therefore tentatively attributed to the 4A2 → 4T2 transition, which then implies a 10 Dq value of about 20,100 cm–1. Proceeding analogously for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−, we obtain a 10 Dq value of about 22,100 cm–1, based on the absorption band at 452 nm (Figure a).

The resulting 10 Dq/B ratios are 32 for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and 33 for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−, but these ratios only represent rather rough estimates, since both the determination of 10 Dq and B are subject to the limitations described above. Our 10 Dq/B estimates are substantially lower than that reported for [Cr(dqp)2]3+ (dashed vertical line in Figure a and Table ), suggesting stabilization of the 4T2 excited state in addition to stabilization of the luminescent 2E state. A smaller energy gap between 2E and 4T2 may also contribute to the lower luminescence quantum yield in our [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− complex (0.1%) compared to [Cr(dqp)2]3+ (5.2%), in addition to the smaller energy gap between the 2E excited state and the 4A2 ground state.

1. Ligand Field Parameters (10 Dq), Racah Parameters (B) and Nephelauxetic Parameters (β) for Several Photoactive CrIII Complexes.

| complex | 10 Dq/cm–1 | B/cm–1 | 10 Dq/B | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cr(dpc)2]+ | 19,200 | 550 | 35 | 0.64 |

| [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ | 22,900 | 760 | 30 | 0.80 |

| [Cr(dqp)2]3+ | 24,937 | 660 | 38 | 0.69 |

| [Cr(NH3)6]3+ | 21,600 | 670 | 32 | 0.70 |

| [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− | 22,100 | 660 | 33 | 0.69 |

| [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− | 20,080 | 630 | 32 | 0.66 |

From refs and .

From ref .

From ref .

From ref .

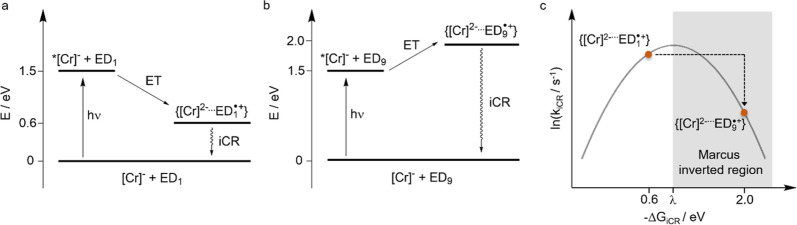

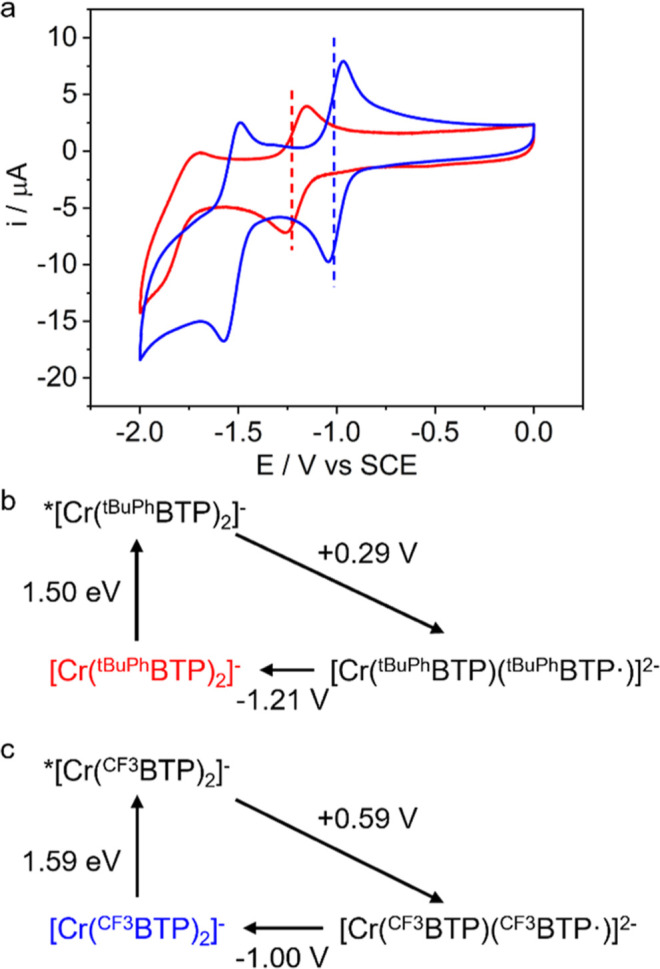

Setting the Basis for Photoreduction Reactions

Based on cyclic voltammetry, [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− is reduced at a potential of −1.21 V vs SCE, while the more electron-deficient [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− is reduced already at −1.00 V vs SCE and also exhibits a second reduction wave centered at −1.53 V vs SCE (Figure ). The observed trend in reduction potentials is compatible with a ligand-centered reduction in both cases, as previously reported for [Cr(MePDP)2]− (MePDP = 2,6-bis(5-methyl-3-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine, Figure e) and several CrIII polypyridines. ,, The reduction potentials of our anionic [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− complexes are significantly more negative than those reported for tricationic CrIII complexes such as [Cr(dqp)2]3+ (−0.4 V) and [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ (−0.7 V), , suggesting that our complexes could potentially facilitate a wider range of reduction reactions after reductive 2E/2T1 excited state quenching by an electron donor.

6.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (red) and [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (blue), recorded from 0.5 mM solutions in Ar-flushed acetonitrile in the presence of 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as a supporting electrolyte. Scan rate: 0.2 V/s. Working electrode: glassy carbon. Counter electrode: silver wire. Reference electrode: KCl saturated calomel (SCE). (b,c) Latimer diagrams including the ground states and the photoactive 2E/2T1 excited states of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and [Cr(CF3BTP)2]−.

Based on 2E/2T1 excited-state energies of 1.50 and 1.59 eV, we estimate excited-state reduction potentials of +0.29 V vs SCE for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and +0.59 V vs SCE for [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (Figure b,c), which are significantly lower than those of the aforementioned tricationic CrIII complexes. For comparison, [Cr(dqp)2]3+ has a reduction potential of +1.26 V vs SCE in the 2E/2T1 excited state, whereas for [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ the respective potential is +0.87 V vs SCE. CrIII polypyridine photooxidants usually undergo reduction at the ligand while the Cr center relaxes back to a quartet state. , In other words, the reduction is coupled to a reverse spin-flip relative to the initial excitation. This reverse spin-flip may contribute to the overall reorganization energy involved in the electron transfer process. In the case of our complexes, the metal–ligand bond exhibits significantly greater covalency compared with polypyridines, which makes it more challenging to distinguish between metal-centered and ligand-based reductions.

The excited-state potentials of our complexes fall below the threshold typically considered favorable for reductive quenching by aliphatic amine donors. However, the 2E/2T1 lifetimes of our complexes are significantly longer than the typical excited-state lifetimes of d6 metal-based complexes or organic photooxidants. − Therefore, kinetic factors can outweigh thermodynamic ones, as demonstrated by the analysis in the following section.

Exploring the Thermodynamic and Kinetic Limits of Reductive Excited-State Quenching

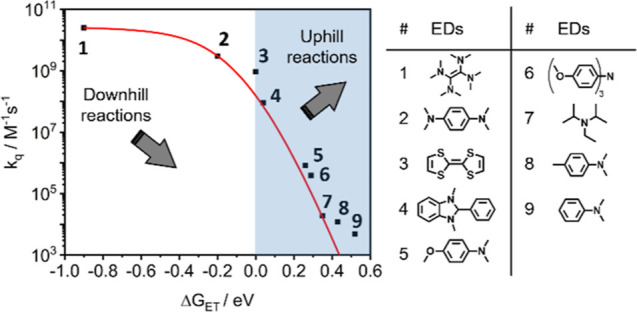

The [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− complex is a stronger photo-oxidant and better electron acceptor than [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, yet we chose to focus on [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− for reductive excited state quenching experiments with different electron donors because the one-electron reduced form of this complex will provide more driving force in reductive photocatalysis than [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− (Figure c,d). We performed 2E/2T1 excited state quenching experiments with 9 different electron donors (EDs) with oxidation potentials ranging from −0.61 to +0.81 V (Figure ), covering a range of reaction free energies for photoinduced electron transfer (ΔG ET) with 2E/2T1-excited [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− between −0.90 and +0.52 eV. Either the transient absorption decay at 680 nm (Figure c) or the corrected emission intensity was used as an observable. Rate constants for bimolecular excited state quenching (k q) were determined for Stern–Volmer analyses and covered a range from 2.5 × 1010 to 4.8 × 103 M–1 s–1 (Figure ).

7.

Rate constants for bimolecular electron transfer (k q) from selected electron donors (EDs, table on the right) to photoexcited [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (black squares) as a function of the reaction free energy (ΔG ET). The red line describes the trend obtained by fitting the data with the empirical Rehm–Weller equation (Supporting Information). The best fit was obtained with a diffusion constant k d of 3.0 × 1010 M–1 s–1, a parameter m accounting for the dissociation of the CrIII–ED encounter complex of 0.025, and a free activation energy ΔG ET (0) of 0.23 eV in acetonitrile at the point where ΔG ET = 0.

Typical Rehm–Weller behavior is observed, and the dependence of k q on ΔG ET can be described empirically by ,

| 1 |

where k d is the diffusion rate constant, k B is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature (298 K). m is an empirical factor that accounts for the rate at which the encounter complex (formed between the excited state of the CrIII complex and the electron donor) dissociates before electron transfer occurs. The activation energy, ΔG ET , is given by

| 2 |

Here, ΔG ET‡(0) represents the free energy of activation when ΔG ET = 0. Our experimental data are best fit with k d = 3 × 1010 M–1 s–1 and ΔG ET‡ = 0.23 eV using m = 0.025 (red trace in Figure ). Based on Marcus theory for electron transfer, the ΔG ET‡ value of 0.23 eV translates into a reorganization energy of 0.92 eV (eq S14) for the photoinduced electron transfer reaction considered here. This is a typical value for reactions of this type. −

The most important finding of our 2E/2T1 excited-state quenching experiments and Rehm–Weller analysis is that [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− enables photoinduced electron transfer reactions that are endergonic up to 0.52 eV. In fact, most of the explored electron donors lead to uphill electron transfer (blue shaded area in Figure ). This favorable behavior is largely due to the comparatively long 2E/2T1 excited state lifetime (23 μs, Figure c) of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, which is more than an order of magnitude longer than for common transition metal-based photosensitizers. ,, The behavior observed here is reminiscent of recent studies conducted in a more synthetically oriented context, where elementary reaction steps that were thermodynamically uphill by 0.3 eV were described as “unforeseen energy-transfer-based transformations”. , Here, we observe electron transfer processes that are nearly twice as energetically uphill despite the fact that electron transfer processes are usually associated with larger activation barriers due to higher reorganization energies compared to energy transfer processes. Under the straightforward condition that the excited-state lifetime is sufficiently long to accommodate relatively slow electron transfer rates on the order of 104 M–1 s–1, this behavior aligns with expectations based on the original Rehm–Weller studies and photochemistry textbooks. , The endergonic region of photoinduced electron transfer reactions is usually less in focus, as most investigators aim to maximize the excited state quenching by achieving high k q values. However, this focus neglects the importance of cage escape, i.e., the process in which the geminate radical pair formed immediately after the photoreaction ([Cr]2–/ED1 •+ in Figure a) dissociates, leading to separately dissolved primary oxidation and reduction products. The efficiency of cage escape governs the overall photoreaction quantum yield and therefore represents an important reaction design factor that seems currently yet underappreciated. The cage escape quantum yield depends on many different factors, among which the reaction free energy for charge recombination (ΔG iCR) can be important. ,−

8.

(a) Energy level diagram for the exergonic (ΔG ET = −0.9 eV) photoinduced electron transfer (ET) from tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE, ED1) to the excited state of the photocatalyst (*[Cr]−) and following in-cage charge recombination (iCR) in the encounter complex; (b) energy level diagram for the endergonic (ΔG ET = +0.5 eV) photoinduced electron transfer from N,N-dimethylaniline (DMA, ED9). The free energy of the charge recombination is still negative (−2.0 eV), but with a higher absolute value than the previous case (−0.6 eV); (c) classical Marcus parabola describing the driving-force dependence of the rate constant for in-cage charge recombination (k iCR). The unwanted back electron transfer from the reduced photocatalyst [Cr]2– to ED9•+ occurs in the inverted regime further away from the maximum of the parabola, and therefore can be slower than the respective back electron transfer from [Cr]2– to ED1•+ . For simplicity, short symbols representing the reduced complex are shown, but the reduction is ligand-based, as displayed in the Latimer diagram in Figure b,c.

Fast downhill photoinduced electron transfer reactions are more likely to provide geminate radical pairs, for which ΔG iCR falls into the normal or activationless regime of the Marcus theory for electron transfer than for slower uphill photoinduced electron transfer. For instance, electron donor 1 (Figure ) reacts with k q = 2.5 × 1010 M–1 s–1 and yields a geminate radical pair (abbreviated as [Cr]2–···ED1 •+ in Figure a) that stores approximately 0.6 eV. Assuming that the reorganization energy associated with in-cage charge recombination is of similar magnitude as the reorganization energy for photoinduced charge separation (0.92 eV, see above), this implies rapid charge recombination near the top of the Marcus parabola. When instead considering electron donor 9 (Figure ), the resulting geminate radical pair (abbreviated as [Cr]2–···ED9 •+ in Figure b) stores 2.0 eV and as such likely falls into the Marcus inverted region (Figure c), for which slower in-cage charge recombination is expected. − Consequently, we expect a trade-off between efficient initial photoinduced electron transfer and efficient in-cage charge recombination. In other words, the reactions providing the fastest excited state quenching are not necessarily the most productive ones in the overall picture.

Unfortunately, an in-depth analysis of this important interplay with our complexes is tricky due to several inherent challenges. First and foremost, many of the investigated electron donors (Figure ) do not have characteristic UV–vis absorption bands in their one-electron oxidized forms, which makes their detection by transient absorption tricky and cage escape quantum yield measurements very difficult. Also, the reduced form of the photocatalyst (Figure S20) exhibits weak features in the sensitivity range of the detector, and its most prominent peaks overlap with the intense transient absorption signal of the doublet excited state (Figure c). The CrIII 2E/2T1 ESA bands mask nearly the entire visible spectral range (Figure c), and unless photoreactions with very high k q values are monitored, it is therefore very difficult to observe the primary [Cr]2– reduction products, especially when cage escape quantum yields are modest. Nonetheless, the considerations summarized in Figure seem valid and might represent an underappreciated aspect in current research on photoredox catalysis. The results presented in the next section offer indirect support for the validity of the arguments presented in Figure .

Exploiting Uphill Reductive Excited-State Quenching for Thermodynamically Challenging Photocatalysis

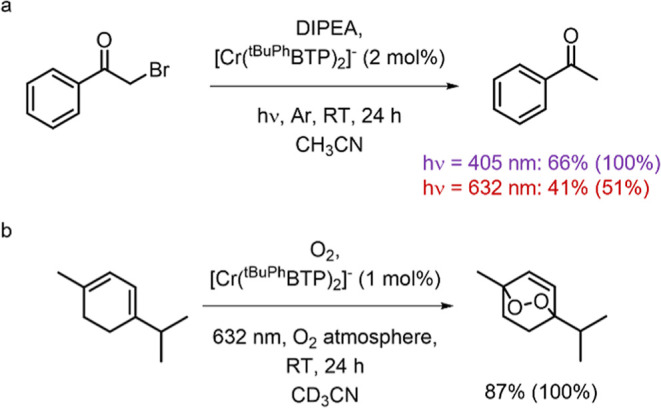

Tertiary amines are widely used as electron donors in photoredox catalysis with noble metal-based or organic photocatalysts to generate a strongly reducing species after an initial photoinduced electron transfer step. , With photoactive CrIII complexes, this strategy is comparatively little explored because their one-electron reduced forms are usually very modest reducing agents. However, the molecular design of our [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and [Cr(CF3BTP)2]− complexes (Figure ) is such that one can expect reducing power comparable to those reachable with many RuII polypyridine complexes. ,, Against this background and the results obtained from the previous section, we explored a benchmark photoreduction reaction and a singlet-oxygen-based photoreaction (Figure ).

9.

(a) Photocatalytic reductive debromination of α-bromoacetophenone upon irradiation with either a 405 or 632 nm LED and (b) oxidation of α-terpinene by singlet oxygen following irradiation at 632 nm in the presence of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−. The product yields (and the substrate conversions reported in parentheses) were determined by HPLC measurements (using suitable calibration curves) in the case of (a) or by 1H NMR spectroscopy referred to an internal standard for (b).

As a first proof-of-concept experiment, we chose the debromination of α-bromoacetophenone (E red = −0.86 V, Figure a), which has been shown to efficiently occur upon reductive quenching of RuII complexes , and inefficiently when using [Cr(dqp)2]3+. Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, number 7 in Figure ) was chosen as an electron donor (E ED+/ED = +0.64 V vs SCE), implying endergonic 2E/2T1 excited-state quenching (Figure ) and a scenario likely resembling that of ED9 in Figure b. We used a DIPEA concentration of 800 mM to enable fast hydrogen atom transfer in the final product-forming elementary reaction step and to ensure a 24% efficiency of the 2E/2T1 excited-state quenching.

Continuous irradiation with an LED at 405 nm, where the [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− complex has a molar extinction coefficient ε of 2800 M–1 cm–1, led to a 66% product yield after 24 h and an overall photoreaction quantum yield (ΦR, see Supporting Information) equal to roughly 1% (Table ). Under these conditions, more than 99% of the incident 405 nm light is absorbed by the CrIII complex. The obtained ΦR value is 30 times higher than that obtained with the [Cr(dqp)2]3+ photocatalyst in the presence of N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine (DMT) as an electron donor. [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− is a weaker photooxidant and therefore undergoes less efficient 2E/2T1 excited state quenching than [Cr(dqp)2]3+, which displays a quenching efficiency of essentially 100%, suggesting that a higher cage escape quantum yield for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− is responsible for the greater overall photoreaction quantum yield (ΦR) obtained for the new complex. These findings are in line with the discussion in the previous section, according to which endergonic initial photoinduced electron transfer can provide better overall photoreactivity (Figure c). In the specific cases considered here, ΔG ET = −0.54 eV and k q = 9.8 × 109 M–1 s–1 for the reaction between [Cr(dqp)2]3+ and DMT, whereas for the [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−/DIPEA couple ΔG ET = +0.35 eV and k q = 1.9 × 104 M–1 s–1. The in-cage charge recombination between the photoreduced [Cr(dqp)2]2+ and the oxidized electron donor, DMT•+, is less exergonic (ΔG iCR = −1.1 eV) than that between [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]2– and DIPEA•+ (ΔG iCR = −1.8 eV). It is therefore plausible that in-cage charge recombination in the [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]2–/DIPEA•+ pair is less kinetically favored due to the Marcus inverted region effect (Figure c), ,− thereby increasing the cage escape quantum yield and enhancing the overall reaction efficiency of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− relative to [Cr(dqp)2]3+.

2. Comparison Between the Photoproduct Yields and the Overall Photoreaction Quantum Yields (ΦR) for the Photoreduction of α-Bromoacetophenone to Acetophenone (Figure a) With [Cr(dqp)2]3+ and [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− as Photocatalysts.

| photocatalyst | λex/nm | time/h | photoproduct yield/% | ΦR/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cr(dqp)2]3+ | 415 | 6 | <10 | 0.03 |

| [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− | 405 | 24 | 66 | 1 |

| [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− | 632 | 24 | 41 | 0.13 |

100 mM N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine (DMT) was used as an electron donor (ED8) in this specific case. At this DMT concentration, the quenching efficiency is 1. λex denotes the excitation wavelength.

The photoreaction in Figure a can also occur in the absence of a photocatalyst, as recently reported, leading in our case to a product yield of 42%. This reaction resulting from direct excitation of the reagent proceeds through a different mechanism and therefore does not affect our conceptual findings above. In the presence of 2 mol % of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, more than 99% of the incident 405 nm LED light is absorbed by the CrIII complex (Figure S41); hence, the reaction channel involving direct excitation of the reagent is unimportant under these conditions.

Photostability tests of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− were performed upon continuous irradiation at 405 nm under air-equilibrated or inert conditions (see Supporting Information for further details). In both cases, the photodegradation quantum yield resulted in being around 2.5 × 10–4 %, indicating resistance to singlet oxygen and good stability under inert conditions. For comparison, RuII and IrIII complexes have been reported to exhibit significantly higher photodegradation quantum yields under comparable conditions.

Improving the Light-to-Chemical Energy Conversion Efficiency by Using Red Excitation

Photons absorbed at 405 nm (3.06 eV) promote [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− to higher electronically excited states, which rapidly relax to the long-lived 2E/2T1 state with nearly unit efficiency. ,, Since the 2E/2T1 excited state has an energy of only about 1.50 eV, the excess energy of 1.56 eV is lost through nonradiative channels and therefore cannot be exploited for photochemical reactions. In other words, when using 405 nm excitation, the maximum light-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency is below 50% (≤1.50 eV/3.06 eV). This is a common challenge with CrIII-based photocatalysts, because they absorb mostly in the blue but very weakly in the red spectral range due to the spin-forbidden nature of the 4A2 → 2E/2T1 transitions. This is particularly relevant for first-row transition metal complexes, which do not display elevated spin–orbit coupling. ,, Although photocatalysis driven by red light is generally on the rise, ,− little research has been carried out with photoactive CrIII complexes in this regard.

At 632 nm (1.96 eV), the [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− complex absorbs with ε = 13 M–1 cm–1, roughly 200 times weaker than at 405 nm. Despite this, the debromination of α-bromoacetophenone proceeded successfully, achieving 51% substrate conversion and 41% product yield after 24 h of continuous irradiation at 632 nm. The control experiment (performed in the absence of CrIII complex) resulted in 40% conversion and a much lower yield (19%). The quantum yield of the photoreaction in the presence of the [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− photocatalyst was 0.13%, still superior to the value obtained for [Cr(dqp)2]3+ (Table ), but lower than the one observed under 405 nm excitation (∼1%). The finding of an approximately 7-fold lower total quantum yield (ΦR) of the photoreaction after red excitation compared to blue excitation could have various causes and is difficult to narrow down here. One possibility is better cage escape when more energetic excitation is used, and this aspect probably deserves further attention with other systems that provide the necessary spectroscopic handles to measure this directly.

As a second red-light-driven photoreaction, we investigated the oxidation of α-terpinene to ascaridole (Figure b) mediated by singlet oxygen. In acetonitrile at room temperature, singlet oxygen quenches the 2E/2T1 excited state of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− with a rate constant of 5.3 × 107 M–1 s–1 and an efficiency of 67% (Supporting Information). The singlet oxygen quantum yield is 70% according to actinometry, closely matching the quenching efficiency and thus indicating that singlet oxygen formation is the main reaction channel. The 1O2 generation quantum yield determined for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− is comparable to that of [Cr(ddpd)2]3+, despite the steric hindrance introduced by the (tert-butyl)-phenyl substituents. This seems noteworthy because recent work found that sterically demanding coordination spheres can protect photoactive CrIII from oxygen quenching. The crystal structure of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (Figure b) reveals sufficient space for oxygen to closely approach the metal center, enabling effective quenching of the spin-flip excited state of CrIII. Upon irradiation of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− at 632 nm, α-terpinene was oxidized to ascaridole with a conversion of 25.9% and a yield of 20.5% in air-equilibrated solution and a quantitative conversion and a yield of 87% in an oxygen atmosphere after 24 h.

The light-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency achieved here with respect to 1O2 formation seems to be thought-provoking from a fundamental conceptual perspective: 632 nm (1.96 eV) photons can in principle be converted with 70% efficiency into a photoproduct (1O2) storing 0.96 eV, implying that even under the seemingly favorable conditions of red light excitation, only about 34% of the photon energy can ultimately be exploited for 1O2 formation. For comparison purposes, methylene blue, a widely used molecule for the generation of singlet oxygen, exhibits a quantum yield of 52% for Dexter energy transfer to O2 in acetonitrile. Upon excitation at the maximum absorption wavelength (664 nm or 1.91 eV), methylene blue converts only 26% of the photon energy.

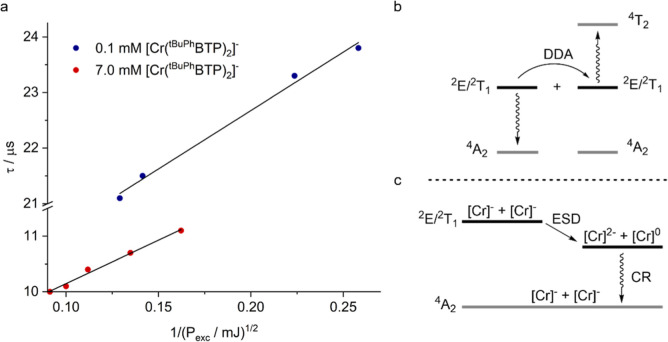

Doublet–Doublet Annihilation and Excited-State Disproportionation: Underappreciated Processes?

In the course of our basic photophysical experiments with [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]−, we found up to a 20% difference in the 2E/2T1 excited state lifetimes, depending on the exact measurement conditions. This prompted us to explore the dependency of the 2E/2T1 excited state lifetime as a function of the excitation energy (P exc) deposited by pulses of ca. 10 ns duration. In a first series of experiments, a 0.1 mM solution of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− was excited at 355 nm, and 2E/2T1 lifetimes increased from 21 to 24 μs when decreasing P exc from 60 to 15 mJ (blue circles in Figure a). In a second series of experiments, we used a 7.0 mM solution of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− and excited the CrIII complex at 532 nm by using the frequency-doubled (instead of the frequency-tripled) output of the same laser. This 7.0 mM solution has the same absorbance (0.4) at 532 nm as the 0.1 mM solution at 355 nm. In the more concentrated solution, the 2E/2T1 excited state lifetimes are lower by a factor of 2 at equal excitation pulse energy, and they further decrease when P exc is increased (red circles in Figure a). For both solutions, we found an inversely proportional relationship between the 2E/2T1 lifetime and the square root of the excitation pulse energy (solid lines in Figure a). This inversely proportional relationship can be interpreted in terms of a deactivation process of the 2E/2T1 excited state that becomes more important with increasing excitation power (Supporting Information, Section 13), and the fact that the square root of P exc (and not simply P exc) is relevant suggests a biphotonic process involving two 2E/2T1 excited CrIII species. Higher initial CrIII concentrations are likely helpful in reaching the regime where these biphotonic processes become important, hence the marked difference between the 2E/2T1 lifetimes determined from solutions with 0.1 mM and 7.0 mM concentrations.

10.

(a) Dependence of the lifetime of the 2E/2T1 excited state of [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− (τ) in Ar-flushed acetonitrile at 25 °C on the excitation pulse energy (Pexc) in mJ, displayed here in the form of its reciprocal square root. The duration of the excitation pulses was approximately 10 ns. The red circles were obtained from a 7.0 mM solution that was excited at 532 nm, whereas the blue circles were recorded from a 0.1 mM solution that was excited at 355 nm. Both solutions had equal absorbance (0.4) at the respective excitation wavelength. The 2E/2T1 lifetime was detected by monitoring the disappearance of the excited-state absorption at 680 nm. The solid black lines are linear regression fits to the experimental data. (b,c) Possible bimolecular processes affecting the 2E/2T1 lifetime: (b) doublet–doublet annihilation (DDA) and (c) excited-state disproportionation (ESD) followed by charge recombination (CR) to the quartet ground state. For simplicity and for consistency with Figure , short symbols representing the reduced and oxidized complex are shown in (c), as ESD could in principle involve both metal-centered and ligand-based redox events; see also Figure b,c.

The observations made for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− in Figure point toward a second-order reaction reminiscent of triplet–triplet annihilation. − Doublet–-doublet annihilation (DDA) has in fact been reported for other CrIII complexes more than 40 years ago (Figure b), , but has remained largely unexplored since then. As noted earlier, in addition to doublet–doublet annihilation, there could also be excited-state disproportionation (ESD, Figure c), where two 2E/2T1-excited CrIII complexes undergo electron transfer to form a one-electron oxidized and a one-electron reduced complex. A third possibility would be aggregation-induced quenching processes, though such behavior is more typical for complexes with other coordination numbers and geometries and for more planar molecular structures, − or for ion pairs. , Based on the reduction potential of −1.21 V vs SCE for [Cr( tBuPhBTP)2]− in the electronic ground state (Figure b), the energy stored in its 2E/2T1 excited state (1.50 eV) and assuming a (ground state) oxidation potential at +1.3 V vs SCE (Figure S19), the reaction free energy for the ESD process is −0.5 eV.

This analysis leaves both ESD and DDA as viable pathways for the behavior observed in Figure a, and at present, it is unclear which one dominates. However, it seems clear that the second-order excited-state quenching process observed by us here can potentially affect photocatalysis when high concentrations and excitation power densities are used. Furthermore, it is conceivable that in favorable cases the higher excited states generated by DDA can be exploited photochemically, although this would likely require further aggregation with substrate molecules to enable sufficiently fast reactions. ,, Ultimately, we cannot exclude the possibility that these processes influence the mechanism of the photoreductions we reported, although this remains a speculative consideration.

Conclusions

The majority of recent work on photoactive CrIII complexes has focused on polypyridine coordination environments and pursued a molecular design strategy aimed at obtaining strong ligand fields to optimize luminescence quantum yields and excited state lifetimes. ,,,,− Our research consolidates a complementary molecular design strategy aimed at optimizing the covalency of the metal–ligand bond and creating more electron-rich CrIII complexes that emit in the near-infrared rather than the red spectral region and are suitable for photochemical reductions in addition to photooxidation reactions. In terms of metal coordination properties, our triazole-based ligands more closely resemble previously studied carbazole, , isoindole, , pyrrole, and triazole ligand systems for CrIII than traditional polypyridines. ,

The photoactive spin-flip excited states of our new CrIII complexes have lifetimes on the order of 5–30 μs, which permits reductive excited state quenching with weak electron donors in elementary reaction steps that are endergonic up to 0.5 eV (around 50 kJ/mol). In principle, this opens the door to red (or even near-infrared) light-driven photocatalysis of endergonic reactions relevant to solar energy conversion and artificial photosynthesis, , and simple proof-of-concept reactions have been successfully performed.

In a wider context, our study addresses a perhaps underappreciated aspect of photoredox catalysis, namely, the extent to which fast excited-state quenching caused by strongly exergonic initial photochemical reaction steps is indeed desirable to optimize the overall reaction quantum yield. Fast exergonic initial photoinduced electron transfer can go hand in hand with fast reverse (energy-wasting) electron transfer elementary steps, resulting in low cage escape quantum yields, whereas slower endergonic photoinduced electron transfer offers the possibility of reaching the Marcus inverted regime for unwanted charge recombination, thereby slowing unwanted energy dissipation and potentially improving overall photoreaction quantum yields. It follows that there must be an optimal thermodynamic constellation between photoinduced forward and thermal reverse electron transfer that optimizes the ratio between energy-storing and energy-wasting reaction rates (Figure ), similar to traditional work in donor-sensitizer-acceptor compounds aimed at mimicking the primary events of natural photosynthesis. , In our case, we achieved a higher overall photoreaction quantum yield based on an initial photoinduced electron transfer step that is endergonic by 0.35 eV than for the same reaction triggered by −0.54 eV exergonic initial photoinduced electron transfer between a different donor/acceptor pair. We anticipate that the intricate interplay between excited state quenching and optimized cage escape quantum yields can be more broadly exploited to improve the reaction quantum yield in photocatalysis.

Our finding of concentration- and excitation-power-dependent 2E/2T1 excited state lifetimes points to doublet–doublet annihilation as a relevant process triggered by photoactive CrIII complexes, which might deserve more attention in future work. Doublet-triplet energy transfer has recently been successfully exploited for upconversion processes, ,− and it seems conceivable that photoreactions involving two doublet excited states could also provide an entry point to conceptually new and useful photochemistry.

Overall, our study illustrates the critical interplay between the molecular design of photoactive transition complexes and the advancement of a fundamental understanding of elementary photochemical reaction steps.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding by the University of Basel and by the Swiss National Science Foundation through grant number 200020_207329 is acknowledged.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c08541.

Additional experimental details, materials, and methods, including equipment details, synthesis and characterization of ligand precursors and complexes, single crystal X-ray data, NMR and HR-ESI mass spectra, photophysical and electrochemical characterization, singlet oxygen generation quantum yield, Stern–Volmer experiment, photocatalytic experiments, and mathematical derivation of the lifetime dependency on the excitation pulse energy (PDF)

University of Basel. Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 200020_207329).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Kirk A. D., Porter G. B.. Luminescence of Chromium(III) Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. 1980;84:887–891. doi: 10.1021/j100445a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S., Grabolle M., Förster C., Kreitner C., Resch-Genger U., Heinze K.. [Cr(ddpd)2]3+: A Molecular, Water-Soluble, Highly NIR-Emissive Ruby Analogue. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:11572–11576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S., Dorn M., Förster C., Bauer M., Seitz M., Heinze K.. Understanding and exploiting long-lived near-infrared emission of a molecular ruby. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018;359:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann W. R., Heinze K.. Charge-Transfer and Spin-Flip States: Thriving as Complements. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202213207. doi: 10.1002/anie.202213207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpone N., Jamieson M. A., Henry M. S., Hoffman M. Z., Bolletta F., Maestri M.. Excited-State Behavior of Polypyridyl Complexes of Chromium(III) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:2907–2916. doi: 10.1021/ja00505a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N., Jiménez J. R., Pfund B., Prescimone A., Piguet C., Wenger O. S.. A Near-Infrared-II Emissive Chromium(III) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60:23722–23728. doi: 10.1002/anie.202106398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürgin T. H., Glaser F., Wenger O. S.. Shedding Light on the Oxidizing Properties of Spin-Flip Excited States in a CrIII Polypyridine Complex and Their Use in Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:14181–14194. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c04465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicka N., Craze C. J., Horton P. N., Coles S. J., Richards E., Pope S. J. A.. Long-lived, near-IR emission from Cr(III) under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:5733–5736. doi: 10.1039/D2CC01434C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Yang Q., He J., Zou W., Liao K., Chang X., Zou C., Lu W.. The energy gap Law for NIR-Phosphorescent Cr(III) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2023;52:2561–2565. doi: 10.1039/D2DT02872G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L., Boden P., Naumann R., Förster C., Niedner-Schatteburg G., Heinze K.. The overlooked NIR luminescence of Cr(ppy)3 . Chem. Commun. 2022;58:3701–3704. doi: 10.1039/D2CC00680D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C. B., Braun J. D., Lozada I. B., Kunnus K., Biasin E., Kolodziej C., Burda C., Cordones A. A., Gaffney K. J., Herbert D. E.. Reduction of Electron Repulsion in Highly Covalent Fe-Amido Complexes Counteracts the Impact of a Weak Ligand Field on Excited-State Ordering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:20645–20656. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N., Yaltseva P., Wenger O. S.. The Nephelauxetic Effect Becomes an Important Design Factor for Photoactive First-Row Transition Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202303864. doi: 10.1002/anie.202303864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N., Wegeberg C., Häussinger D., Prescimone A., Wenger O. S.. Photoredox-active Cr(0) luminophores featuring photophysical properties competitive with Ru(II) and Os(II) Complexes. Nat. Chem. 2023;15:1730–1736. doi: 10.1038/s41557-023-01297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. P., Reber C., Colmer H. E., Jackson T. A., Forshaw A. P., Smith J. M., Kinney R. A., Telser J.. Near-infrared 2Eg → 4A2g and visible LMCT luminescence from a molecular bis-(tris(carbene)borate) manganese(IV) complex. Can. J. Chem. 2017;95:547–552. doi: 10.1139/cjc-2016-0607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul N., Asempa E., Valdez-Moreira J. A., Smith J. M., Jakubikova E., Hammarström L.. Enter MnIV-NHC: A Dark Photooxidant with a Long-Lived Charge-Transfer Excited State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:24619–24629. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c08588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Persson P., Sundström V., Wärnmark K.. Fe N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes as Promising Photosensitizers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:1477–1485. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær K. S., Kaul N., Prakash O., Chábera P., Rosemann N. W., Honarfar A., Gordivska O., Fredin L. A., Bergquist K. E., Häggström L., Ericsson T., Lindh L., Yartsev A., Styring S., Huang P., Uhlig J., Bendix J., Strand D., Sundström V., Persson P., Lomoth R., Wärnmark K.. Luminescence and reactivity of a charge-transfer excited iron complex with nanosecond lifetime. Science. 2019;363:249–253. doi: 10.1126/science.aau7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N., Pfund B., Wegeberg C., Prescimone A., Wenger O. S.. Cobalt(III) Carbene Complex with an Electronic Excited-State Structure Similar to Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:9859–9873. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c02592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting S. I., Garakyaraghi S., Taliaferro C. M., Shields B. J., Scholes G. D., Castellano F. N., Doyle A. G.. 3d-d Excited States of Ni(II) Complexes Relevant to Photoredox Catalysis: Spectroscopic Identification and Mechanistic Implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:5800–5810. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c00781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Sinha N., Pfund B., Prescimone A., Wenger O. S.. Molecular Design Principles to Elongate the Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer Excited-State Lifetimes of Square-Planar Nickel(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:21948–21960. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c08838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden M. T., Yufit D. S., Williams J. A. G.. Luminescent bis-tridentate iridium(III) complexes: Overcoming the undesirable reactivity of trans-disposed metallated rings using-N^N^N–-coordinating bis(1,2,4-triazolyl)pyridine ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2022;532:120737. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Garah M., Sinn S., Dianat A., Santana-Bonilla A., Gutierrez R., De Cola L., Cuniberti G., Ciesielski A., Samorì P.. Discrete Polygonal supramolecular architectures of isocytosine-based Pt(II) complexes at the solution/graphite Interface. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11163–11166. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05087E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mydlak M., Mauro M., Polo F., Felicetti M., Leonhardt J., Diener G., De Cola L., Strassert C. A.. Controlling Aggregation in Highly Emissive Pt(II) Complexes Bearing Tridentate Dianionic N^N^N Ligands. Synthesis, Photophysics, and Electroluminescence. Chem. Mater. 2011;23:3659–3667. doi: 10.1021/cm2010902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. R., Doistau B., Cruz C. M., Besnard C., Cuerva J. M., Campaña A. G., Piguet C.. Chiral Molecular Ruby [Cr(dqp)2]3+ with Long-Lived Circularly Polarized Luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13244–13252. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b06524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda A. S., Petersen J. L., Milsmann C.. Redox Chemistry of Bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine Chromium and Molybdenum Complexes: An Experimental and Density Functional Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2018;57:1919–1934. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morselli G., Reber C., Wenger O. S.. Molecular Design Principles for Photoactive Transition Metal Complexes: A Guide for “Photo-Motivated” Chemists. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025;147:11608–11624. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5c02096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittel S., Neuner J., Grenz J. M., Förster C., Naumann R., Heinze K.. Gram-Scale Photocatalysis with a Stable and RecyclableChromium(III) Photocatalyst in Acetonitrile and in Water. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2025;367:e202500075. doi: 10.1002/adsc.202500075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson S. M., Shores M. P., Ferreira E. M.. Photooxidizing Chromium Catalysts for Promoting Radical Cation Cycloadditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:6506–6510. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins R. F., Fatur S. M., Shepard S. G., Stevenson S. M., Boston D. J., Ferreira E. M., Damrauer N. H., Rappé A. K., Shores M. P.. Uncovering the Roles of Oxygen in Cr(III) Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5451–5464. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar J. V., Kober E. M., Sullivan B. P., Meyer T. J.. Application of the energy gap law to the decay of charge-transfer excited states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:630–632. doi: 10.1021/ja00366a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J. M., Yun Y. J., Jamhawi A. M., Peccati F., Jiménez-Osés G., Ayitou A. J. L.. Doublet Spin State Mediated Photoluminescence Upconversion in Organic Radical Donor-Triplet Acceptor Dyads. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025;147:1017–1027. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c14303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketkaew R., Tantirungrotechai Y., Harding P., Chastanet G., Guionneau P., Marchivie M., Harding D. J.. OctaDist: a tool for calculating distortion parameters in spin crossover and coordination complexes. Dalton Trans. 2021;50:1086–1096. doi: 10.1039/D0DT03988H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser A., Mäder M., Robinson W. T., Murugesan R., Ferguson J.. Electronic and Molecular Structure of [Cr(bpy)3]3+ (bpy = 2,2′-Bipyridine) Inorg. Chem. 1987;26:1331–1338. doi: 10.1021/ic00255a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond K. N., Meek D. W., Ibers J. A., James A.. The Structure of Hexaamminechromium(III) Pentachlorocuprate(II), [Cr(NH3)6] [CuCl5] Inorg. Chem. 1968;7:1111–1117. doi: 10.1021/ic50064a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constable E. C., Housecroft C. E., Neuburger M., Schönle J., Zampese J. A.. The surprising lability of bis(2,2′:6′,2″- terpyridine)chromium(III) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:7227–7235. doi: 10.1039/C4DT00200H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe W. A., Bird P. H., Jamieson M. A., Serpone N.. Interligand Pockets in Polypyridyl Complexes. The Crystal and Molecular Structure of the Cr(2,2′,2″-terpyridine)2 3+ Ion. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1979:798–800. doi: 10.1039/c39790000798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich S., Strähle J.. Zur Struktur Des Pentaazadienidions [Tol-N = N-N-N = N-Tol]−. Synthese und Kristallstruktur von Cs2(18-Krone-6)(TolN5tol)2 und (NH4)[Cr(NH3)6(H2O)4](TolN5tol)4 . Z. Naturforsch., B: J. Chem. Sci. 1993;48:1574–1580. doi: 10.1515/znb-1993-1116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L., Wang C., Förster C., Resch-Genger U., Heinze K.. Bulky ligands protect molecular ruby from oxygen quenching. Dalton Trans. 2022;51:17664–17670. doi: 10.1039/D2DT02950B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe Y., Sugano S.. On the Absorption Spectra of Complex Ions II. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1954;9:766–779. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.9.766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenauer F., Wang C., Förster C., Boden P., Ugur N., Báez-Cruz R., Kalmbach J., Carrella L. M., Rentschler E., Ramanan C., Niedner-Schatteburg G., Gerhards M., Seitz M., Resch-Genger U., Heinze K.. Strongly Red-Emissive Molecular Ruby [Cr(bpmp)2]3+ Surpasses [Ru(bpy)3]2+ . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:11843–11855. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c05971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann W. R., Moll J., Heinze K.. Spin-flip luminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022;21:1309–1331. doi: 10.1007/s43630-022-00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. R., Poncet M., Míguez-Lago S., Grass S., Lacour J., Besnard C., Cuerva J. M., Campaña A. G., Piguet C.. Bright Long-Lived Circularly Polarized Luminescence in Chiral Chromium(III) Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60:10095–10102. doi: 10.1002/anie.202101158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. W., Auty A. J., Wu G., Persson P., Appleby M. V., Chekulaev D., Rice C. R., Weinstein J. A., Elliott P. I. P., Scattergood P. A.. Direct Determination of the Rate of Intersystem Crossing in a Near-IR Luminescent Cr(III) Triazolyl Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:12081–12092. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c01543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann W. R., Ramanan C., Naumann R., Heinze K.. Molecular ruby: exploring the excited state landscape. Dalton Trans. 2022;51:6519–6525. doi: 10.1039/D2DT00569G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiling S., Wang C., Förster C., Reichenauer F., Kalmbach J., Boden P., Harris J. P., Carrella L. M., Rentschler E., Resch-Genger U., Reber C., Seitz M., Gerhards M., Heinze K.. Luminescence and Light-Driven Energy and Electron Transfer from an Exceptionally Long-Lived Excited State of a Non-Innocent Chromium(III) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:18075–18085. doi: 10.1002/anie.201909325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., He J., Zou W., Chang X., Yang Q., Lu W.. Circularly polarized near-infrared phosphorescence of chiral chromium(III) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2023;59:1781–1784. doi: 10.1039/D2CC06548G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zedler L., Müller C., Wintergerst P., Mengele A. K., Rau S., Dietzek-Ivanšić B.. Influence of the Linker Chemistry on the Photoinduced Charge-Transfer Dynamics of Hetero-Dinuclear Photocatalysts. Chem. - Eur. J. 2022;28:e202200490. doi: 10.1002/chem.202200490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C., Bold S., Chavarot-Kerlidou M., Dietzek-Ivanšić B.. Photoinduced electron transfer in triazole-bridged donor-acceptor dyads - A critical perspective. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022;472:214764. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo A., Monti F., Mazzanti A., Matteucci E., Armaroli N., Sambri L., Baschieri A.. 4-Phenyl-1,2,3-triazoles as Versatile Ligands for Cationic Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022;61:8509–8520. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c00567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scattergood P. A., Sinopoli A., Elliott P. I. P.. Photophysics and photochemistry of 1,2,3-triazole-based Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;350:136–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ching H. Y. V., Wang X., He M., Perujo Holland N., Guillot R., Slim C., Griveau S., Bertrand H. C., Policar C., Bedioui F., Fontecave M.. Rhenium Complexes Based on 2-Pyridyl-1,2,3-triazole Ligands: A New Class of CO2 Reduction Catalysts. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:2966–2976. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. V., Skelton B. W., Raiteri P., Massi M.. Photophysical and photochemical studies of tricarbonyl rhenium(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes containing azide and triazolate ligands. New J. Chem. 2016;40:5797–5807. doi: 10.1039/C5NJ03301B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarranton J. T., McCusker J. K.. Ligand-Field Spectroscopy of Co(III) Complexes and the Development of a Spectrochemical Series for Low-Spin d6 Charge-Transfer Chromophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:12488–12500. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c04945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough C. C., Sproules S., Weyhermüller T., DeBeer S., Wieghardt K.. Electronic and molecular structures of the members of the electron transfer series [Cr(tbpy)3]n (n = 3+, 2+, 1+, 0): an X-ray absorption spectroscopic and density functional theoretical study. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:12446–12462. doi: 10.1021/ic201123x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough C. C., Lancaster K. M., Debeer S., Weyhermüller T., Sproules S., Wieghardt K.. Experimental Fingerprints for Redox-Active Terpyridine in [Cr(tpy)2](PF6)n (n = 3–0), and the Remarkable Electronic Structure of [Cr(tpy)2]1‑ . Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:3718–3732. doi: 10.1021/ic2027219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrin Y., Odobel F.. Sacrificial electron donor reagents for solar fuel production. C. R. Chim. 2017;20:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2015.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicewicz D. A., Nguyen T. M.. Recent Applications of Organic Dyes as Photoredox Catalysts in Organic Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2014;4:355–360. doi: 10.1021/cs400956a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speckmeier E., Fischer T. G., Zeitler K.. A Toolbox Approach to Construct Broadly Applicable Metal-Free Catalysts for Photoredox Chemistry: Deliberate Tuning of Redox Potentials and Importance of Halogens in Donor-Acceptor Cyanoarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:15353–15365. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari D. P., König B.. Synthetic applications of eosin Y in photoredox catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:6688–6699. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzani V., Bolletta F., Scandola F.. Vertical and ″Nonvertical” Energy Transfer Processes. A General Classical Treatment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2152–2163. doi: 10.1021/ja00527a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm D., Weller A.. Kinetics of Fluorescence Quenching by Electron and H-Atom Transfer. Isr. J. Chem. 1970;8:259–271. doi: 10.1002/ijch.197000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara P. F., Meyer T. J., Ratner M. A.. Contemporary Issues in Electron Transfer Research. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:13148–13168. doi: 10.1021/jp9605663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J. R., Gray H. B.. Long-Range Electron Tunneling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:2930–2939. doi: 10.1021/ja500215j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss-Petermann M., Wenger O. S.. Electron Transfer Rate Maxima at Large Donor-Acceptor Distances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1349–1358. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalti, M. ; Credi, A. ; Prodi, L. ; Gandolfi, M. T. . Handbook of Photochemistry, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prier C. K., Rankic D. A., MacMillan D. W. C.. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:5322–5363. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieth-Kalthoff F., Henkel C., Teders M., Kahnt A., Knolle W., Gómez-Suárez A., Dirian K., Alex W., Bergander K., Daniliuc C. G., Abel B., Guldi D. M., Glorius F.. Discovery of Unforeseen Energy-Transfer-Based Transformations Using a Combined Screening Approach. Chem. 2019;5:2183–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teders M., Henkel C., Anhäuser L., Strieth-Kalthoff F., Gómez-Suárez A., Kleinmans R., Kahnt A., Rentmeister A., Guldi D., Glorius F.. The energy-transfer-enabled biocompatible disulfide-ene reaction. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:981–988. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaiano, J. C. Photochemistry Essentials; ACS Publications, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Li H., Bürgin T. H., Wenger O. S.. Cage Escape Governs Photoredox Reaction Rates and Quantum Yields. Nat. Chem. 2024;16:1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/s41557-024-01482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin M. J., Dickenson J. C., Ripak A., Deetz A. M., McCarthy J. S., Meyer G. J., Troian-Gautier L.. Factors that Impact Photochemical Cage Escape Yields. Chem. Rev. 2024;124:7379–7464. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould I. R., Ege D., Moser J. E., Farid S.. Efficiencies of Photoinduced Electron-Transfer Reactions: Role of the Marcus Inverted Region in Return Electron Transfer within Geminate Radical-Ion Pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4290–4301. doi: 10.1021/ja00167a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gould I. R., Moser J. E., Ege D., Farid S.. Effect of Molecular Dimension on the Rate of Return Electron Transfer within Photoproduced Geminate Radical Ion Pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1991–1993. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gould I. R., Moser J. E., Armitage B., Farid S., Goodman J. L., Herman M. S.. Electron-Transfer Reactions in the Marcus Inverted Region. Charge Recombination versus Charge Shift Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:1917–1919. doi: 10.1021/ja00187a077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell T. U.. The forgotten reagent of potoredox catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2022;51:13176–13188. doi: 10.1039/D2DT01491B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott E. D., Burnett N. L., Swierk J. R.. Mechanistic and kinetic studies of visible light photoredox reactions. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2023;4:031312. doi: 10.1063/5.0156850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teegardin K., Day J. I., Chan J., Weaver J.. Advances in Photocatalysis: A Microreview of Visible Light Mediated Ruthenium and Iridium Catalyzed Organic Transformations. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016;20:1156–1163. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. D., Murphy J. A.. Recent advances in visible light-activated radical coupling reactions triggered by (i) ruthenium, (ii) iridium and (iii) organic photoredox agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:9540–9685. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00311A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Shen J., Qu C., Shao T., Cao S., Yin Y., Zhao X., Jiang Z.. Enantioselective Chemodivergent Three-Component Radical Tandem Reactions through Asymmetric Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:20141–20148. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c08883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S., Mochizuki S., Tanaka T.. Photocatalytic Reduction of Phenacyl Halides by 9,10-Dihydro-10-methylacridine. Control between the Reductive and Oxidative Quenching Pathways of Tris(bipyrldine)ruthenium Complex Utilizing an Acid Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:722. doi: 10.1021/j100365a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Lam T.-L., Liu Y., Tang Z., Che C.-M.. Photoinduced Hydroarylation and Cyclization of Alkenes with Luminescent Platinum(II) Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60:1383–1389. doi: 10.1002/anie.202011841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chen J., Chen J., Luo Y., Xia Y.. Solvent as photoreductant for dehalogenation of α-haloketones under catalyst-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022;98:153835. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid L., Kerzig C., Prescimone A., Wenger O. S.. Photostable Ruthenium(II) Isocyanoborato Luminophores and Their Use in Energy Transfer and Photoredox Catalysis. JACS Au. 2021;1:819–832. doi: 10.1021/jacsau.1c00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauben J. N., Dillman K. L., Beck W. F., Mc Cusker J. K.. Vibrational coherence in the excited state dynamics of Cr(acac)3: probing the reaction coordinate for ultrafast intersystem crossing. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:405–410. doi: 10.1039/c0sc00262c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juban E. A., McCusker J. K.. Ultrafast Dynamics of 2E State Formation in Cr(acac)3 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6857–6865. doi: 10.1021/ja042153i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büldt L. A., Wenger O. S.. Chromium Complexes for Luminescence, Solar Cells, Photoredox Catalysis, Upconversion, and Phototriggered NO Release. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:7359–7367. doi: 10.1039/C7SC03372A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z. L., Zhang H. J., Cheng Y., Liu J., Ai Y., Li Y., Feng Z., Zhang Q., Gong S., Chen Y., Yao C. J., Zhu Y. Y., Xu L. J., Zhong Y. W.. Recent progress on photoactive nonprecious transition-metal complexes. Sci. China: Chem. 2025;68:46–95. doi: 10.1007/s11426-024-2345-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koseki S., Matsunaga N., Asada T., Schmidt M. W., Gordon M. S.. Spin-Orbit Coupling Constants in Atoms and Ions of Transition Elements: Comparison of Effective Core Potentials, Model Core Potentials, and All-Electron Methods. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2019;123:2325–2339. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b09218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser F., Wenger O. S.. Red Light-Based Dual Photoredox Strategy Resembling the Z-Scheme of Natural Photosynthesis. JACS Au. 2022;2:1488–1503. doi: 10.1021/jacsau.2c00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]