Abstract

Exploration of synthetic transformations using high throughput experimentation (HTE) can accelerate the rapid discovery of optimal conditions for organic reactions and improve our understanding of those processes and synthetic route for different applications. The surge in high throughput techniques has been applied to a broad range of methods and target-oriented reaction optimizations across a diverse array of bond-constructions. In this Minireview, we describe HTE based workflows, discuss different transformations that have been evaluated using HTE platforms with a focus on homogeneous catalytic reactions, and highlight challenges reported in the field since 2016. The HTE efforts are grouped by the type of bonds being formed, for instance, carbon-carbon (C-C), carbon-nitrogen (C-N), carbon-halogen or carbon-oxygen (C-X) bonds, as well as photochemical transformations and hydrogenations. The potential of HTE to rapidly guide the optimization of multiple synthetic challenges makes it a very attractive and powerful tool for synthetic organic chemists.

Keywords: High throughput experimentation, high throughput organic synthesis, organometallic synthesis, bond forming reactions, reaction screening

Graphical Abstract

Accelerating organic synthesis: Optimization and diversification of synthetic transformations using high throughput experimentation (HTE) accelerates the drug discovery and development process. This Minireview is an overview of HTE techniques applied to a broad family of reaction classes and different target-oriented synthesis. Recent trends in the type of bonds being formed as well as photochemical and hydrogenation processes have been highlighted. HTE workflows along with the analytical methods used to support them are discussed.

1. Introduction

High throughput experimentation (HTE) has emerged as a powerful tool to guide the rapid discovery of optimal reaction conditions for challenging transformations and even discover new reactivity patterns[1]. In HTE, multiple reactions are performed simultaneously in parallel instead of just one reaction at a time. For instance, a common method is to construct and analyze 96 simultaneous reactions in a single experiment. This provides important information regarding yield, by-product formation, optimal temperature, preferred solvents, and additives to identify the most favorable conditions for a given transformation. With appropriate experimental design, it can also provide insights into reaction mechanisms. The robustness and scope of a reaction can also be probed by rapidly evaluating different substrates in parallel. HTE is typically performed using microscale (millimole to nanomole) quantities[2], thereby reducing the cost and consumption of chemicals needed to generate large datasets. It also reduces significantly the amount of time required for reaction development and optimization of complex transformations where multiple factors can interact to alter reaction outcomes anticipated from one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) investigations. HTE has been used to accelerate the discovery of optimal conditions for target-oriented organic synthesis. It is especially useful for identifying improvements to sluggish or low yielding transformations as well as for identifying and expanding the scope and/or selectivity of a transformation of interest[3]. These data-rich experiments can provide key insights and highly textured knowledge about the reaction space when coupled to different analytical techniques to help identify trends in solvent, catalyst, and competing reactions. The resulting datasets can also be used to inform artificial intelligence and machine learning methods[4], thereby impacting route selection to potentially transform the way chemistry will be done in the future. Table 1 highlights some of areas search where researchers have utilized HTE.

Table 1.

Examples of Chemical Reactivity Challenges That Have Been Addressed by High-throughput Experimentation Between 2016–2020.

|

The advantages of HTE have led to a surge in the number of publications describing this approach (Figure 1). This review focuses on HTE efforts to guide organic synthesis and understand the challenges and potential future areas of development that have been reported between January 2016 to January 2021. Publications describing high throughput discovery strategies[5] such as DNA-encoded libraries[6], PROTACs based HTE[7], biocatalytic transformations[8] in continuous flow synthesis[9], kinetic data acquisition in catalytic transformations[10], or optimization of porous inorganic materials[11] are outside the scope of this review. A recent article[12] has provided insight into high throughput experimentation from an industrial standpoint; however, this overview focuses on the use of HTE tools to develop new methodologies and optimization of key transformations in target oriented synthesis.

Figure 1.

Trends in last two decades in the field of high throughput studies as revealed by Web of Science searches between 1999 – 2019.

1.2. Common Terminologies and Workflow in HTE

Liquid and solid handling robots are commonly used in HTE workflows. These devices are essentially advanced and automated versions of pipettes that can aspirate and dispense the reagent solutions and enable the weighing and transfer of powders/solids, respectively. Some examples include: Quantos QB5, Chemspeed SWING, and Biomek i7. Recipes can be created using computer software based on Excel files that specify the amount of reagent or solvent to be transferred. The reaction solutions are built on the deck of the robot in throughputs ranging from 24 to 6144 reactions. In the absence of robots, manual 8-channel pipettes can also assist in building the reaction wells. The reaction well plate usually contains a range of unique reaction conditions; however, some strategies employ sample replicates to build statistical power and/or mitigate data dropout in the results obtained downstream. Some examples of the reagent well plates available for HTE include tumble-stirrer, magnetic stirrer, and sealed aluminum reaction blocks with 96 or 24 glass vial inserts that can be heated to desired temperature or equipped with LEDs of varying wavelength for high throughput evaluation of photochemical transformations. Experimental design and reaction plate layout are a crucial part of the workflow that the experimentalist must consider prior to initiating the experiment to query a range of variables of interest in the transformation (Figure 2). Multi-variate screens are common, but design of experiment-based workflows are also increasing[13]. Depending on the method chosen for reaction analysis, the reagent solutions can either be diluted, evaporated, extracted, or directly analyzed. Some of the analytical methods used include gas chromatography (GC), gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS), high or ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC/UHPLC), liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS), acoustic droplet ejection (ADE)-open port interface mass spectrometry (ADE-OPI-MS), electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), desorption electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (DESI-MS), UV-vis spectroscopy, super critical fluid chromatography (SFC)-mass spectrometry (SFC-MS), and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS).

Figure 2.

Illustration of a general workflow for a high throughput experiment focused on aryl cross coupling reactions.

The HTE publications summarized in this review have been organized according to the type of bond being formed (C-C, C-N, C-X, hydrogenation, photocatalytic transformation) as indicated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The most widely tested reaction classes in HTE studies reported in the last 5 years (Web of Science search). The size of the bubble represents the number of publications for the indicated reaction type.

2. C-C Bond Forming Reaction

2.1. Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling (Scheme 1a) (S-M coupling)

Scheme 1.

C-C Bond forming reactions commonly explored in HTE.

Suzuki-Miyaura coupling is the most widely performed reaction in the HTE format. In many instances it was used for identifying conditions appropriate for sensitive substrates or labile functional groups. Ichiishi et al.[14] identified novel conditions that tolerated diazirine groups in the synthesis of photoaffinity probes. Cross-coupling reactions with diazirine containing substrates are extremely slow and have low yields because of their thermal instability and as their propensity to act as competing coupling partners. They utilized a fragment-based HTE strategy wherein three starting materials were used along with a diazirine motif, a quinoline halide, and a phenyl boronic acid derivative. The reactions were performed at three different temperatures using four different catalysts, with HPLC being used to monitor product formation efficiency and unreacted diazirine content for these S-M couplings. SPhos Pd G2 at 40°C was identified as the most suitable condition with THF:H2O (4:1) and K3PO4 as base.

Baker and coworkers explored S-M coupling for producing bromodifluoromethyl(arylsulfonyl) analogs via Csp2—CF2CO2Ar bond formation[15]. The reactions were performed using microwave-assisted Ni-, Pd-, Cu-, Fe-based catalysts with different combinations of phosphine ligands. Ni(acac)2, phosphine ligand, and K2CO3 in 1,2- dichloroethane at 120°C gave the best yield of desired product as determined by GC-MS analysis.

The synthesis of Savolitinib was optimized[16] by exploring 96 different combinations of catalyst and solvent. Pd-132 and Pd(OAc)2 were revealed to be the best choice, with Pd(dppf)Cl2 showing lower activity. Higher concentrations of K2CO3 resulted in hydrolysis, whereas primary alcohols resulted in solvolysis. A subsequent 96 well HTE used Pd-132, Pd(OAc)2/t-BuPPh2, and Pd(OAc)2/cataCXium A with 2° and 3° alcohols, four different bases and a solvent:water ratio of either 1:1 or 9:1. Faster reaction rates were observed using K2CO3 or K3PO4 in 1:1 solvent:water mixtures. By monitoring for solvolysis, hydrolysis, and protodehalogenated by-products along with the desired product, it was found that Pd-132 was the most effective catalyst. Further process development with Pd-132 catalyst enabled the synthesis of the drug target at scale with <50 ppm Pd downstream.

A cobalt catalyzed C (sp2)—C(sp3) S-M cross coupling[17] was developed for aryl boronic esters and alkyl bromides. HTE assisted in the choice of cobalt-ligand combination to achieve optimal selectivity and yield in this electrophile derived radical transformation.

Thompson et. al[18] reported a rapid mass spectrometric analysis of 648 unique S-M coupling reactions with 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid and 11 aryl halides. The reaction condition chosen for substrate screening were XPhos Pd G3, DBU and EtOH at different stoichiometries and temperatures (50°C, 100°C, 150°C, and 200°C). Variations in order of reagent additions indicated that hydrolysis of the boronate ester occurred in some cases, thus showing that a particular order of addition to build the reaction plate can be essential for obtaining reliable data. The MS ion count obtained from DESI-MS was used to develop heat maps that identified regions of highly efficient S-M coupling.

Delivery of small quantities of solid reagents (<1mg) is often a challenge in HTE. Wang and coworkers at AbbVie[19] demonstrated a novel approach to efficiently transfer the solids using ChemBeads. Solid reagents adherent to the glass beads by van der Waals forces were transferred to reaction plates where reagent release from the glass bead occurs when it encounters the reaction solvent. This method was shown to reliably deliver 0.5–1 mg of solid efficiently. Transfer of 0.5 μg (nanomole) scale delivery was accomplished for C-C and C-N bond forming reactions.

Further advances in solid handling were validated Bahr and coworkers[20] using the automated commercial powder dispensing platforms provided by Chemspeed and Mettler Toledo. Six different powders were dispensed over 3240 times across three different platforms and a comparison of accuracy, analysis of variance, error distribution and dispense time for dispensing solid ranging from 0.1 mg to 50 mg doses was performed. Overall, the Chemspeed GDU-S SWILE system was favorable for sub-to low mg dispensing of free-flowing or non-cohesive powders. For handling of solid air- and water-sensitive reagents, a solvent disintegrating tablet-based approach[21] containing the solid powder of reagents like catalysts, ligands, and LiAlH4 was prepared and multiple reactions including Suzuki coupling were performed in a high throughput manner.

2.2. Heck Coupling (Scheme 1b)

Rapid analysis methods employing paper-based colorimetric sensors have been motivated by the desire for low cost assays. An organosilane-patterned paper based colorimetric sensor[22] was developed for identifying the conversion of aryl bromides by the detection of bromide ions after C—C bond forming reactions. Transformations evaluated included S-M coupling, Stille coupling, Heck coupling, direct arylation and decarboxylative coupling reactions. 4-bromoanisole and 4’-bromoacetophenone with 16 different ligands (monophosphines, bisphosphines, pyridines, phenanthrolines, L-proline) with Pd(OAc)2 in DMF and four different bases with coupling partners specific to the type of reaction were evaluated in HTE. The reaction mixtures were spotted on the paper sensor, with the extent of color change indicating the degree of conversion. This approach gave good correlations when compared to GC-MS.

Discovery of a novel transformation based on a rational catalytic cycle that was proposed prior to testing was shown by Newmann et al.[23]. An intermolecular carbonyl Heck reaction (Scheme 1b) for the synthesis of ketones from aldehydes and aryl halides was explored by performing multiple parallel reactions. They tested their hypothesis using HTE to evaluate parameters like catalyst, ligand, solvent, additive, and substrate type to identify conditions that were effective in generating even trace amounts of product to inform subsequent rounds of optimization. Ni(COD)2, triphos, and either tetramethylpiperidine or quinuclidine as base were found to give ketone products in high yield when aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes were used.

A robust one-pot Suzuki-Heck relay reaction was demonstrated by Jong and Baker[24], wherein Suzuki coupling was performed to synthesize terminal alkenes, followed by Heck coupling to generate the E isomers with minimum undesired homocoupling by-products using the Pd-Cy*Phine catalytic system.

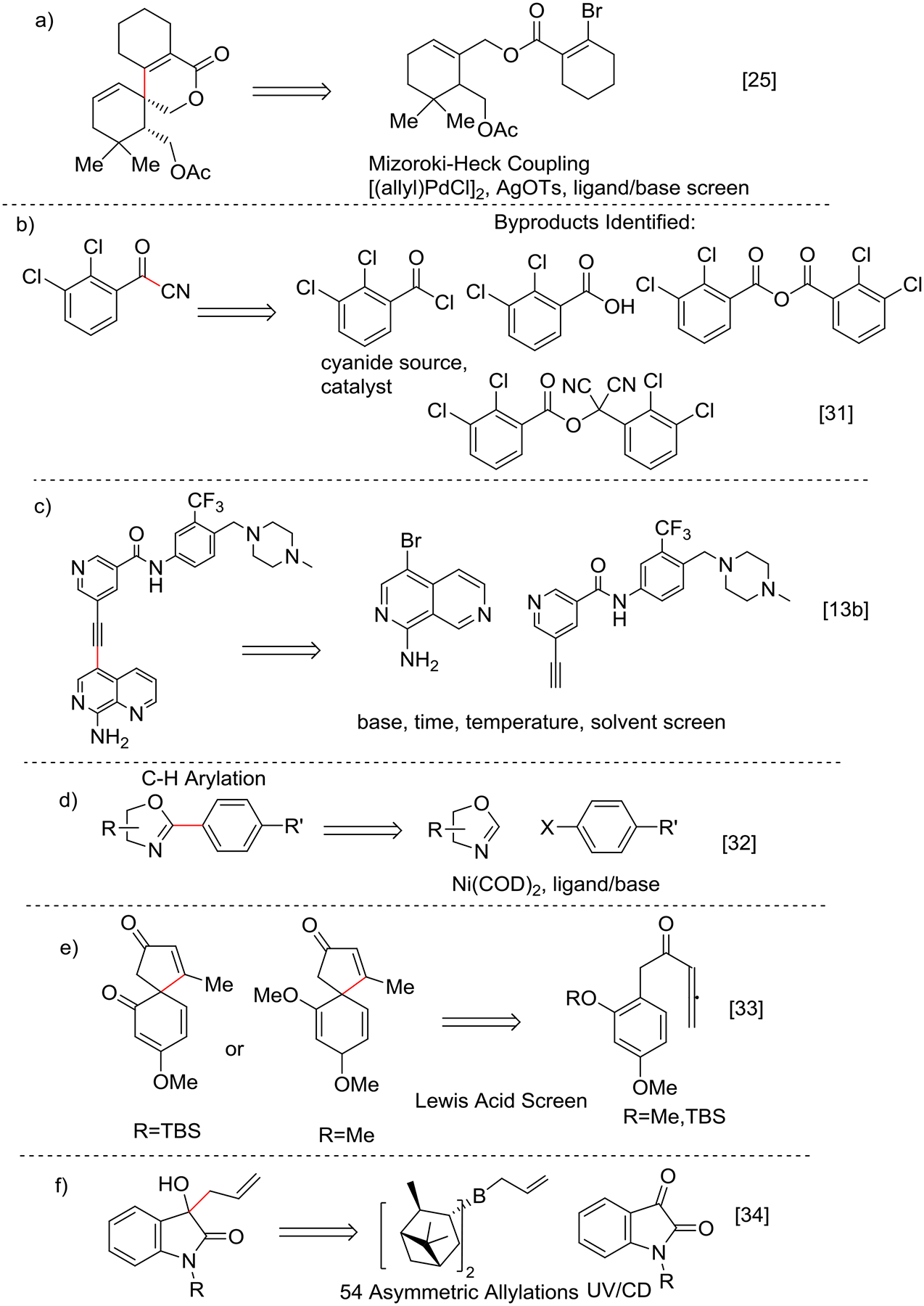

A Mizoroki-Heck approach was similarly used to demonstrate the synthesis of a tricyclic spirolactone by evaluating 24 unique HTE conditions using four ligands and six base combinations to identify optimized conditions for synthesizing the target in high regioselectivity and high yield. [25] (Scheme 2a).

Scheme 2.

C-C Bond forming reactions optimized using HTE.

2.3. Negishi Coupling (Scheme 1c)

In an effort to develop air-stable Negishi coupling catalysts for large scale transformations, Levi and coworkers[26] showed late stage functionalization of a kinase inhibitor via sp3—sp2 reductive cross coupling. After screening 12 ligands and two solvents, less hydrodehalogenated by-product was identified by LC-MS analysis when lower catalyst loadings were used. This effort also identified an effective air- and moisture-stable nickel pre-catalyst, with [Ni(tBuTerpy)(H2O)3]Cl2 and Zn metal in ACN at 90°C providing the most favorable condition. These findings enabled a wider substrate scope search using primary and secondary alkyl halides.

Greshock et. al[27] reported Negishi coupling reactions with 17 bench-stable organozinc pivalates with 18 drug-like electrophiles. Preliminary microscreening revealed successful reaction outcomes using four pre-catalyst systems, including PEPPSI-IPr, XPhos Pd G3, QPhos Pd G3, and NiXantPhos Pd G3. Taking forward the best identified condition that included organozinc pivalate and XPhos Pd G3 in THF at 50°C, an MS-directed high throughput purification using a commercially available platform was performed to isolate 1–2 mg of pure product to support the drug-discovery Tier 1 assay.

Competition between linear versus branched chain products can occur in Negishi coupling, making it imperative to fine tune the reaction conditions for optimal selectivity. Cherney et. al[28] used a HTE pre-catalyst screen for coupling of 2-bromopyridine with acyclic sec-alkyl organozinc reagents to attain highly selective branched to linear (b:l) product ratios of >100:1. A preliminary screen evaluated 12 Pd-precatalysts with 2-bromopyridine and iPrZnBr in THF. Xantphos provided a b:l ratio of 97:1 leading to a subsequent round of HTE. Comparison of Xantphos Pd G3 against EtCPhos Pd G3 and PEPPSI IHept-Cl across 16 diverse pyridyl halides was performed with UPLC analysis.

2.4. Olefin Metathesis (Scheme 1d)

Efforts by Han and coworkers[29] have focused on fluorescence-based screening for cross metathesis and ring closing reactions. This strategy is based on monitoring pyrene excimer intensity in the presence of Z-olefin during metathesis reactions; eximer content is directly proportional to the conversion of the olefin substrate. Their HTE involved a terminal olefin, three internal olefins, and five Grubbs/Hoveyda-Grubbs metathesis catalysts (G-I, G-II, G-III, HG-I, HG-II) in toluene. The conversion of terminal olefin was analyzed by fluorescence and GC. Comparative studies between both analytical techniques gave good correlation.

Fedorov et. al performed an HTE to identify a robust Ru-metathesis catalyst for ethenolysis of maleate esters to acrylate esters using an HTE employing four catalysts, seven solvent conditions, and varying catalyst loadings. GC-FID analysis revealed the optimal choice of catalyst as second generation Hoveyda-Grubbs type catalyst, achieving turnover numbers (TON) approaching 5200[30].

2.5. Nucleophilic Addition

Leitch et. al sought to improve the cyanation of 2,3 dichlorobenzoyl chloride, a problematic step in the synthesis of lamotrigene[31] (Scheme 2b). A qualitative design of experiments (DoE) strategy was used wherein three cyanide sources, five co-solvents and 15 catalysts were evaluated along with different KI equivalencies. Three side products were identified by GC-MS: the carboxylic acid hydrolysis product, the corresponding acid anhydride, and a geminal dicyano species. NaCN was identified as an effective cyanide source, but due to higher homocoupling, CuCN with NEt3 as catalyst, in toluene/ACN as solvent at 100°C was chosen for the further process development.

2.6. Others

Sonogashira couplings (Scheme 2c) to produce an alkynylnaphthyridine anti-cancer agent were performed using HTE in combination with a DoE approach to identify the best temperature, base, solvent, and ligand conditions[13b]. HTE also provided mechanistic insights into the rate determining step, thereby leading to a 10-fold decrease in catalyst loadings in the final telescoped continuous flow synthesis of HSN-608.

Direct C-H bond activation is an important transformation that is increasingly used to reduce the number of steps in multi-step synthetic sequences. In this context, HTE can help identify the scope of C-H activation strategies to help guide synthetic pathway development. For instance, C-H arylation using oxazole and benzoxazole with Ni(COD)2 catalyst[32] has been evaluated using five base/ligands and 42 heteroaryl halides (Scheme 2d). Identification of CBS/SnCl4 as a potent chiral Lewis acid for spirocyclization of electro-rich allenyl ketones was achieved through an HTE campaign using 23 Lewis acids, including CBS, TADDOL, STIEN, PYBOX, and salen motifs, combined with HPLC analysis for yield and SFC analysis for enantiomeric excess[33] (Scheme 2e).

In order to circumvent the time-consuming nature of chiral HPLC or NMR for evaluating asymmetric reactions, UV/Circular Dichroism based methodology was developed to monitor 54 asymmetric allylations of isatin with chiral boron reagents[34] (Scheme 2f). Efforts were also devoted to the analysis of high throughput data obtained from asymmetric reactions to identify the enantiomeric or diastereomeric excess via chemometrics[35], or artificial neural network[36] approaches; these methods are still in early stages of development. For example, a 2D-LC/MS analytical method was developed by Genentech using achiral separation in the 1st dimension and chiral separation in the 2nd dimension to determine the yield and stereoselectivity. Their method achieved a 10-minute run-time directly from samples of crude reaction mixture without co-elution or ion suppression[37].

3. C-N Bond Forming Reaction

C-N bond forming reactions are the second most widely studied transformation in the HTE workflow.

3.1. N-Arylation

Leitch and coworkers[38] have shown the power of HTE by identifying a potent Pd catalyst and ligand combination that enables C-N coupling to form sterically demanding N,N’ diaryl sulfonamides. Initial screens focused on aryl and pyridyl bromides with the same sulfonamide in the presence of multiple palladium sources, phosphine ligands, and carbonate bases. Their results indicated that AdBippyPhos, combined with [Pd(crotyl)Cl]2 as the catalyst at >5mol% loadings, provided the highest conversion using LC-MS area percent as the experimental readout. Lowering the Pd loadings to 1 mol% was achieved by subsequent testing with >300 substrates. Incorporation of 3Å molecular sieves led to the elimination of byproducts arising from dehalogenation, hydroxylation, and etherification. A diverse set of heteroaryl electrophiles and various sulfonamides were also evaluated for the C-N coupling with AdBippyPhos. Heterocyclic cores of furans, azindoles, pyridines, pyrazines, thiazoles, thiophenes, and benzothiazole worked well, however, pyrroles and pyrazoles were less efficient coupling partners.

3.2. Buchwald-Hartwig Amination (Scheme 3a)

Scheme 3.

C-N Bond forming reactions in HTE.

Buchwald-Hartwig amination has been one of the least understood transformations despite wide efforts to improve our mechanistic insights. Sather and Martinot[39] investigated C-N coupling with challenging five membered heteroaromatic electrophiles and piperidine-based nucleophiles that often lead to side reactions like β-hydride elimination and protodehalogenation. Their work employed an initial HTE focused on catalyst identification followed by a scan of catalyst loadings. By monitoring product formation and starting material conversion using LC-MS analysis, a base-promoted unproductive pathway for pyrazole N-N bond breakage was identified. This guided a subsequent focused base and solvent screen for desired product formation, followed by a 33-full factorial DoE with temperature and catalyst loadings as dependent variables. Reaction scope analysis of 48 electrophiles at constant nucleophile and vice versa was performed. Amidation side reactions with ester substrates and incompatibility of alcohols and secondary amides were identified as the most problematic issues impacting the efficiency of these heteroaromatic transformations.

Discovery of novel catalysts is an attractive avenue for C-N coupling that has been reported by Guram[40]. Their workflow for catalyst discovery involved the synthesis of a diverse phosphine ligand library that was then tested in a high throughput manner using GC/LC for yield analysis and qualitative conversions by parallel TLC. Buchwald-Hartwig amination and S-M coupling reactions were evaluated for their ability to attain higher TON, turnover frequency, and selectivity.

3.3. Ullmann Coupling (Scheme 3b)

DNA conjugated aryl iodide was tested against 6300 primary amine building blocks in Ullmann type Cu(I) coupling reactions, where Cu(I) was generated in situ using CuSO4•5H2O and sodium ascorbate[41]. Development of a novel synthetic route using HTE to scout conditions was reported by AstraZeneca[42] for the synthesis of AZD7594. The presence of palladium in the Buchwald-Hartwig amination caused problems downstream for the drug target, leading the authors to investigate Ullmann coupling as an alternative. Different combinations of ligand, solvent, and base were used to test >230 reactions using UPLC-MS analysis. High throughput solubility testing of free base and furate salt was performed in 20 solvents. The Ullmann reaction was evaluated using eight diamine ligands and 12 solvents with CuI, K2CO3 at 100°C. It was identified in the initial experiments that DMF was crucial to obtain complete conversion. These conditions were ultimately deselected due to regulatory considerations. Their solubility studies showed high solubility of starting materials and poor solubility of product in nitrile-based solvents. Subsequent reaction analysis revealed that PrCN and PhCN with diamine ligands gave full conversion to the target.

3.4. SNAr (Scheme 3c)

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution is a widely used medicinal chemistry reaction. In drug discovery campaigns, efforts to identify potent inhibitors by rapid synthesis and evaluation of compound libraries with different functionality is very important. Three SNAr studies[43] have emerged where structural variations and reaction scope using different electrophiles, nucleophiles, solvents, and base conditions have been explored (Scheme 3b). Nelson et. al[43a] performed HTE for identification of reaction conditions for SNAr to synthesize diacylglycerol acyl-transferase 1 (DGAT1) inhibitors. Multiple rounds of HTE were performed to synthesize 43 different substrates with a success rate of 81% for isolated substrates. Variations in base and solvent type were performed for different classes of electrophiles with a fixed set of nucleophiles across a wide range of analogues in a structure-activity relationship.

Thompson et. al[43b] evaluated 3072 unique reactions in NMP using DESI-MS with an analysis time of 3.5 s per reaction in HTE where four different base conditions (DIPEA, NaOtBu, TEA, no base) across eight amines and 12 electrophiles in multiple rounds of HTE. Information derived from the HTE was shown to rapidly translate to reaction conditions in flow.

Cernak et. al[43c] performed multiple rounds of HTE for optimizing a key SNAr step, employing a spiropiperidine and 2-fluoropyridine in a survey with six bases and four solvents on a scale of ~1mg starting material per reaction. CPME with DIPEA at 110°C turned out to be the most favorable condition. A further expansion in HTE was performed with six nucleophiles, six electrophiles, and four conditions split into two rounds with UPLC-MS analysis.

3.5. Sulfonamidation (Scheme 3d)

Development of novel ligands and identifying their substrate scope is an important method for improving catalytic transformations. Biaryl phosphorinanes[44] as ligands, prepared in the absence of Cu, have been developed. These novel ligands have shown excellent performance for sulfonamidation and Pd-catalyzed C-O and C-N coupling with a wide range of electrophiles and nucleophiles. An HTE evaluation was performed in three rounds with eight nucleophiles and 12 electrophiles with two bases (DBU and MTBD) with catalytic Pd2(dba)3, NaOtBu, and varying biarylphosphirnane ligands with Cs2CO3 or with different solvents. Area % product formation determined by LC-MS was used to identify the most promising reaction conditions.

3.6. Earth Abundant Catalytic Transformation

Exploration of earth-abundant catalysts derived from iron or nickel is an important area of catalyst development due to their low cost and minimal toxicity[45]. FeCl2, NiCl2, CoCl2, and Fe(OAc)2 have been studied in high throughput metal catalyzed deoxygenation reactions. Researchers identified an iron phenanthroline catalyst with PhSiH3 for conversion of ortho-nitrostyrenes to indoles[46] (Scheme 3e). Identification of optimal ligands for non-precious metals like Fe, Cu, Ni can be challenging, thereby limiting their utility in everyday workflow. Pharmaceutical N-, O- containing heterocyclic compound libraries to serve as new ligands[47] in cross electrophile screening has been demonstrated.

3.7. Other Transformations

Another important facet where HTE has progressed is identification of chiral catalysts that produce target compound in high ee. An example of this was reported for the case of 42 organocatalysts for aza-Michael addition of cyclic imides to enals to generate highly enantiopure 3-amino aldehydes on the μmol scale[48].

4. Droplet-based Technology: Rapid Analytical Tools

Reactions performed in droplets on the nanomole scale with rapid analysis has been shown, with throughputs of 6144 reactions being analyzed in <3h[49]. The power of this method was demonstrated in HTE studies of N-alkylation[50] and reductive amination reactions[51]. Another example of rapid analysis is acoustic droplet ejection (ADE) technology[52] in a miniaturized manner for synthesis of drug-like moieties using a tandem Fischer indole and Ugi multicomponent reaction (Scheme 3f). Analysis was performed by SFC-MS and TLC-UV-MS. Researchers at Pfizer have also utilized acoustic droplet ejection-open port interface-mass spectrometry (ADE-OPI-MS) for rapid analysis to enhance drug discovery efforts. They showed the ability to directly perform the analyses from multi-well plates with only 1–20 nL of analyte with minimum sample handling and without the need for an internal standard calibration[53]. Ultra-fast screening using MALDI-TOF-MS has been used for profiling nanomole C—N coupling reactions on 1536 plates at a rate of 0.3–0.4 s per sample.[54] A detailed workflow for reaction profiling has been reported[55]. A variation of this approach utilizes self-assembled monolayers for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (SAMDI-MS). Photo-capture via diazirine[56] terminated monolayers enabled analysis of 1920 reactions in ~2.5h. This technique was used to evaluate acyl benzimidazolium salt for conversions to acetophenone derivatives under varying Lewis acids, photocatalysts, and solvents in a 384 spot-format.

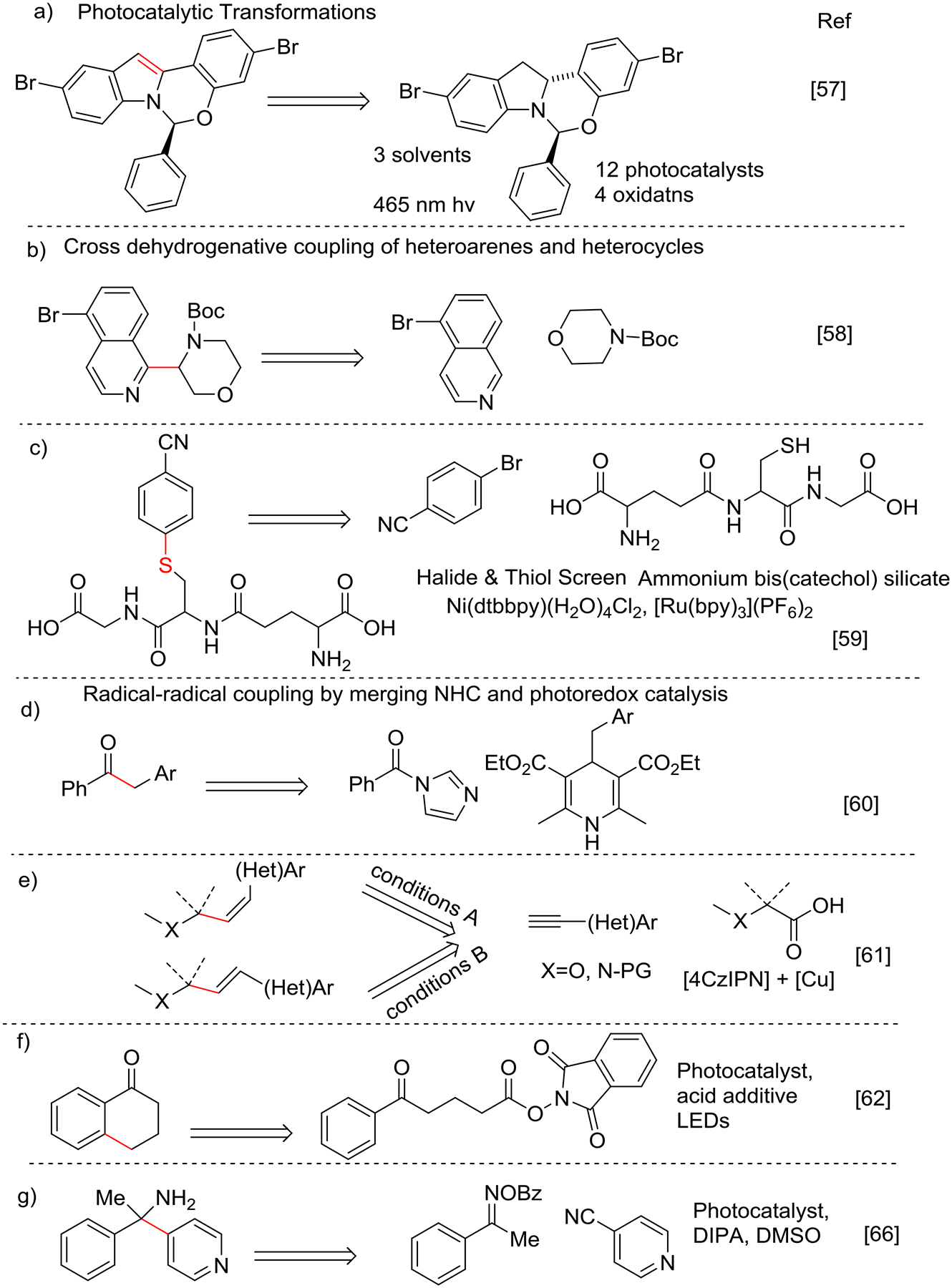

5. Photocatalytic Transformation

5.1. Dehydrogenation/ Dehydrogenative Coupling

Identification of the optimal choice of photocatalyst, wavelength of light, or additives can be a time-consuming aspect of developing photochemical transformations. HTE approaches have been widely used in these cases to accelerate the discovery process.

Knowles and coworkers demonstrated[57] the synthesis of elbasvir on the 100 g scale using a key dehydrogenation step that was challenging due to epimerization at the hemiaminal carbon stereocenter (Scheme 4a). HTE was utilized to identify the best photocatalyst and benign terminal oxidant for this reaction. Catalyst screens included a family of Ru & Ir-based photocatalysts, Eosin, and Rose Bengal, while oxidants included K2S2O8, MeNO2, tBPA, and CBrCl3. [Ir(dFCF3-ppy)2(dtbpy)](PF6) as the photocatalyst with nitromethane and tBPA gave moderate yields without any loss in optical purity.

Scheme 4.

Photocatalytic transformations in HTE

Direct C-H functionalization provides unique reactivity with metallophotoredox systems. Dehydrogenative coupling[58] with a family of amines bearing protective Boc groups and heteroarenes in 768 unique reactions under irradiation with blue and white LED on the nmol scale has been shown. The findings that emerged from these studies were used to guide a fragment-based drug discovery campaign that informed the conditions needed to execute the reaction efficiently in flow (Scheme 4b).

5.2. Radical Coupling via Dual Catalysis

Molander and coworkers have reported a dual catalyst Ni/photocatalyst-based cross coupling reaction between unprotected thiols and aryl halides (Scheme 4c)[59] by performing a Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) reaction using the tripeptide L-glutathione and 4-bromobenzonitrile in presence of Ni, Ru, ammonium bis(catechol) silicate under blue LED excitation. The substrate reactivity scope of the aryl halides was studied using a microscale HTE with 18 complex halides and four thiols including glutathione, pencillamine, thioglucose, and tiopronin. Aryl iodides and bromides were reactive; however, no hits were observed with aryl chloride substrates.

Scheidt and co-workers[60] have demonstrated a dual catalysis approach by merging N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) and photoredox catalysis for the synthesis of ketones from carboxylic acids and Hantzsch ester precursors. A semi-HTE strategy assisted in identification of Hantzsch esters as the primary alkyl radical source. This was followed by an extended survey of three photocatalysts, four bases, four solvents and five azolium radical precursors (Scheme 4d). The HTE results indicated a facile transformation with dimethyltriazolium as NHC precursor and [Ir(dFCF3ppy)2(dtbpy)]PF6 as photocatalyst with Cs2CO3 in CH3CN using a 467 nm LED.

Another example of HTE with dual catalysis employed a Cu catalyst and 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene (4CzIPN) photocatalyst for hydroalkylation of terminal alkynes with carboxylic acid precursors. A screen of two Cu sources, four ligands, three bases, and four solvents led to the identification of optimal conditions to form either E and Z alkenes[61] based on the conditions employed (Scheme 4e).

5.3. Intramolecular Cyclization

Sherwood and coworkers have shown intramolecular Csp2—Csp3 cyclization of N-acyloxyphthalimides by formation of a radical intermediate that undergoes arene cyclization after decarboxylation[62] (Scheme 4f). Upon observing the product with α-tetralone, HTE was used to examine the optimal parameters including solvent, acid additive (BF3•OEt2, TFA), photocatalyst (Ru, Ir, organocatalysts), concentration, and LED wavelength (415 nm, 470 nm, 527 nm, white light) by monitoring the conversion and the ratio of cyclized to uncyclized product with UPLC. Purple LEDs (415 nm) gave good conversion under a wide range of conditions and were selected along with 4CzIPN as the photocatalyst. A wide substrate scope was shown using ketone and non-ketone electron-rich and electron-deficient arenes and heteroarenes.

Generation of stable radicals to instill β-umpolung reactivity by synthesis of diarylmalonates from arylidene malonates and cyanoarenes has also been optimized using an HTE approach[63].

5.4. Other Photochemical Transformations

Non-activated alkyl bromides were coupled to Michael acceptors in a photoredox Giese-type reaction[64]. Reaction optimization was performed by studying the effect of photocatalyst, solvent, base, and varying amounts of radical initiator (Me3Si)3SiH on product and by-product profile. Another study of conjugate addition using photocatalytic methodology was shown for the synthesis of unnatural β-alkyl α-amino acid derivatives via decarboxylative photocatalysis[65]. Photocatalysis was performed with oxime and cyanopyridine precursors (Scheme 4g) to form primary amine products[66]. Four different solvents (acetone, DCE, ACN, DMSO), nine different photocatalysts, and two reductants were used to evaluate 45 unique reactions. DMSO with diisopropylamine and Ir[dF(Me)ppy]2dtbbpyPF6 gave the highest yield by UPLC, although many by-products containing pyridine were observed unless excess 4-cyanopyridine was used.

A standardized multi-use photoreactor has been developed with interchangeable LED lights to perform synthetic reactions, bioconjugation and cellular labelling. Proof of concept was demonstrated by performing C—N, C—C, and dehalogenation reactions in a single reactor array by changing the source of LED. Further, biotinylation for labeling carbonic anhydrase and live-cell labeling was performed using the same photoreactor[67].

6. Asymmetric Hydrogenation

Enantioselective hydrogenation[68] to rapidly identify the choice of ligand and precatalyst combination for N-alkyl α-aryl ketimines containing a furyl group to give the challenging N-alkyl D-enantiomer has been performed in high throughput (Scheme 5a). A screen of asymmetric catalysts including (Rh, Ru, Ir precursors with sulfonated diamine ligand) gave an enantiomeric ratio of 83:13. HTE investigation of Ir based bisphosphine and chiral P,N ligands catalyst gave an enantiomeric ratio of 91:9 when Ir-(S,S)-f-BINAPHANE was used. Analogs including a SF5 bearing moiety, as well as Boc- and Fmoc- protected analogs were synthesized with the identified conditions.

Scheme 5.

Asymmetric Hydrogenation in HTE

Shevlin and coworkers[69] showed the power of HTE to provide mechanistic insights for asymmetric hydrogenation reactions of α,β-unsaturated esters with an air stable nickel catalyst (Scheme 5b). Ni(OAc)2 was combined with 192 chiral phosphine ligands for preliminary investigation of ethyl β-methyl-cinnamate hydrogenation. Ni(OAc)2 with Me-DuPhos in presence of iodide additives in methanol improved the reactivity and enantioselectivity. Given the challenge of isolating a catalytic intermediate, HTE enabled the simultaneous evaluation of varying conditions. This method helped to identify the performance of the catalyst as a function of ratio of multiple precursor components. It was found that a trimetallic nickel species, formed at low concentrations, was the active hydrogenation catalyst; this transient species is likely in equilibrium with other nickel intermediates.

HTE was performed for stereoselective Suzuki-Miyuara cross coupling reactions to generate precursors for the synthesis of α-methyl-β-cyclopropyldihydrocinnamate derivatives[70] (Scheme 5c). (Z)-Enol tosylate and phenyl boronic acid derivatives with 24 ligands in eight different base/solvent combinations were explored. K3PO4 as base in CH3CN/H2O mixtures with Pd(OAc)2 /XPhos or SPhos gave the highest yield of the desired (Z)-coupled product. (Z) product was obtained exclusively with the two starting materials, (E)-enol tosylate and (Z)-enol tosylate. The presence of the hydrogenation-labile cyclopropyl group in the substrate posed a challenge in the next stage of asymmetric hydrogenation. Identification of catalyst, ligand, and solvent for synthesis of (S,R)-α-methyl-β-cyclopropyldihydrocinnamate was achieved in a high throughput manner. (NBD)2RhBF4 and (Me-allyl)2Ru(COD)/HBF4 as catalyst, 24 chiral phosphine ligands, and two solvents including MeOH and 2-MeTHF were evaluated. (Me-allyl)2Ru(COD)/ HBF4 combined with Josiphos J010–1 gave high conversion in MeOH. A further ligand screen was performed with the preferred Ru catalyst produced high yields when Josiphos and JoSPOphos ligands were used.

7. C-X Bond Forming Reactions

7.1. C-B Bond Formation via Miyaura Borylation

Leitch and coworkers utilized HTE capability for optimizing one of the synthetic steps in the development of GSK8175[71], a target containing a benzofuran moiety. Challenges in this synthesis were the presence of a methoxymethyl ether (MOM) protecting group, potential formation of desbromo by-products, and the complexity of the substrate that contained chloro and bromo substituents in the aryl halide analog. HTE for the C—B bond forming reaction employed substrates containing four different protecting groups to circumvent the use of MOM. These included acetate (-OAc), pivalate, tert-butyldimethylsilyl, and 2-tetrahydropyranyl (-OTHP) protecting groups along with 48 different ligands. The protecting groups were well tolerated and even simple monodentate ligands were effective. Although desbromination was seen in every case, diborylation via the chloro substituent was not observed. Owing to the facile conditions for protection and deprotection with OTHP, a follow up screen with monodentate ligands, solvent, and base variations was conducted. It was found that electron rich, less sterically demanding ligands like PPrPh2 and PCyPh2 generally gave better yields.

The synthesis of Verinurad, a potent URAT 1 inhibitor[72], has also been explored by HTE. The traditional method used a lithium-bromine exchange followed by a triisopropyl borate quench under cryogenic conditions that limited its scale up capability. An alternative route of Miyuara borylation was investigated using eight palladium catalyst combinations, six acetate bases, and two solvents. Conditions for high conversion were found using PdCl2(PPh3)2 in the presence of KOAc, CsOAc, or NMe4OAc. Upon investigation of the reaction with KOAc, limited starting material conversions, and poor solubility was encountered. A subsequent screen of acetate, pivalate, and propionate bases showed that a significant increase in the reaction rate occurred using potassium pivalate.

7.2. C-O Bond Forming Reactions

Fier and Maloney[73] have demonstrated a robust Cu-catalyzed synthesis of phenol from aryl halide using a hydroxide surrogate approach. Traditional Cu catalyzed hydroxylation requires harsh conditions, displays poor functional group tolerance, and results in competing N-H and O-H arylation (Scheme 6a). In their approach, a complex aryl halide was chosen to explore the role of ester hydrolysis and epimerization in the transformation. The reaction conditions investigated used different benzaldoximes, ligands, Cu sources and mild bases for phenol formation. Initial screening of 96 reactions with 12 ligands gave high yields with oxamide ligands, but other ligands only gave incomplete conversion. A more extensive screen of 384 unique reactions using 96 novel ligands and four different aryl halide analogs was then performed. No ester hydrolysis or epimerization was observed in this round of HTE. Significant impact on reaction yields with different ligands was observed, thereby highlighting the importance of incorporating novel ligands in the screening approach.

Scheme 6.

C-X bond forming reactions (C-O and C-I)

Stevens et. al[74] have utilized HTE to identify Lewis acids for converting N-acyloxazolidinone intermediates to esters and amides containing an α-stereocenter in a single step with high selectivity (Scheme 6b). Screening of 24 different Lewis acids in methanol and ethanol as the solvent using two different substrates at 65°C for 24 hours was conducted. Common Lewis acids like AlCl3, Al(OTf)3, and FeCl3 were effective in methyl ester formation, but they did not yield the ethyl ester or the bulkier analog. Lanthanide catalysts like Gd(OTf)3, Er(OTf)3, and Yb(OTf)3 gave the desired product with sterically hindered and ethyl ester analogs. Reaction monitoring of 19 lanthanide catalysts with increasing ionic radius revealed that smaller ionic radii (103.2 to 106.2 pm) gave shorter reaction times, such that Yb(OTf)3 was chosen for further development. Robustness of the transformation was demonstrated by expanding the scope of the reaction using different substrates, auxiliaries, alcohols, acyl, and amine components. Overall, the multivariable strategy incorporated in the HTE provided a clear distinction in the performance of different Lewis acid catalysts to enable the synthesis of a pharmaceutically important intermediate.

Asymmetric transformations are particularly challenging in HTE as the analysis can be time consuming using traditional methods. Comprehensive chirality sensing (CCS)[75] has been shown to be a rapid and sustainable alternative that utilizes the formation of stereodynamic ligands with Zn, Al, or Ti that can be recognized by circular dichroism to give fluorescent signals in 96 asymmetric dihydroxylation reactions within 4 minutes [35b]. Evaluation of amine product chirality generated during asymmetric hydrogenation using an EKKO CD plate reader for analysis has been reported. The enantiomeric excess of the amines was determined by developing calibration curves for the reaction of 4-chlorocoumarin with chiral amines[76].

7.3. Ullmann Coupling

Discovery of new ligands for copper catalyzed Ullmann-type coupling reactions was explored using an Abbvie compound library[47b]. Small molecules (54 compounds) with chelating groups that can act as ligands were used at 20 mol% to couple 6-bromoquinoline and m-cresol. A subsequent round of ligand screening identified oxalamide as a lead whose robustness was demonstrated using a wide range of substrates with substituted and heterocyclic analogs of alcohols and aryl bromides.

7.4. C-I / C-Br Bond Forming Reactions

Regioselective functionalization of C—I bond containing moieties has been demonstrated (Scheme 6c) by utilizing tunable 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine metallic bases[77]. Since the site of functionalization can be difficult to predict, an HTE employing four temperatures and six bases was tested for four substrates. Initial screening efforts were directed toward known substrates to validate the methodology, followed by inclusion of heterocyclic precursors of drug like molecules. For instance, in the case of imidazopyrazine, the iodo group was observed at C-(5) with TMPMgCl·LiCl, whereas C-(8) functionalization was observed with TMPZnCl·LiCl at −45°C.

Perfunctionalization of cyclodextrins (α-, β-, and γ-CDs)[78] where the primary alcohol is converted to a chloro or bromo analog has been achieved with the assistance of HTE. A novel acidic hydrolytic quench was developed with automated sampling using LC/MS and DoE based kinetic profiling approach used to develop a better mechanistic understanding. This functionalization resulted in development of a robust process that was run at the 1 kg scale for bromination of γ-cyclodextrin.

8. Summary and Outlook

HTE has emerged as an important tool to assist and accelerate the productivity of the synthetic chemist. A reiterative process of design, execution, data analysis, and hit identification enables rapid exploration of conditions for reaction optimization. Much of the recent effort has focused on C—C and C—N bond forming transformations, although the use of HTE for developing photochemical transformations is also increasing. The time-consuming nature of UPLC-MS and GC-MS analyses serves as a persistent discovery bottleneck, however, these methods are still the most widely used HTE tools. Newer methods of reaction analysis like DESI-MS, ADE-OPI-MS, MALDI-TOF, and colorimetric-based assays are likely to grow in their importance for HTE campaigns.

By adopting the principles of green chemistry to eliminate stoichiometric reagents, exploring renewable and greener solvents, and identifying potent robust catalysts for transformations like amidation and C—H activation[79], HTE will continue to make valuable new contributions to synthesis. In addition, the use of HTE platforms to develop novel transformations or applying known chemistry to bio-renewable feedstocks[80] offers the prospect for minimizing our dependence on petroleum-based raw materials. Late-stage functionalization of pharmacophores in approved drugs and strategies to incorporate -CF3, -F and other bioisosteric functionalities are also potential areas of HTE development[81]. Faster analytical tools that can reliably and rapidly identify complex diastereoselective and regioselective transformations is an area of great need. Although the analysis of enantiomeric excess for chiral transformations has seen some advancement, there is still a need for more widespread and sensitive techniques.

Further developments are likely where HTE becomes integrated with statistical[82] and computational modeling[83] and machine learning[84]. The approach towards multi-step one-pot synthesis can be further utilized for other C-C or C-X reactions including direct or remote C-H activation with 3d transition metals[85]. Finally, with such extensive data rich experimentation, there is a compelling need for robust data management and storage tools with end-to-end integration from solid/liquid dispensing to final reaction outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to express our gratitude for the assistance of David Zwicky from Library of Sciences and Engineering, Purdue University for helping us with our literature search.

Biographies

Professor Thompson earned Bachelor degrees in Chemistry and Biology from the University of Missouri-Columbia and a Ph.D. degree in Organic Chemistry from Colorado State University (1984) for his work with Louis S. Hegedus. After postdoctoral studies with James K. Hurst at the Oregon Health & Sciences University, he joined the Department of Chemical & Biological Sciences there as an Assistant Professor. He moved to the Department of Chemistry at Purdue University in 1994 as an Associate Professor and was promoted to Professor in 2000. He has been recognized as a University Faculty Scholar, a Top Ten Outstanding Teacher in the College of Science at Purdue, and the Head of the Organic Chemistry Division (2003–2010). Prof. Thompson has published over 160 papers and been awarded 9 patents in areas focused on the synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients by telescoped continuous manufacturing methods, development of bioresponsive self-assembling materials for gene and drug delivery, and accelerated protein structure determination by cryoEM using novel materials and sample preparation techniques.

Shruti Biyani obtained her B.Tech (2017) degree from Institute of Chemical Technology. Since 2017, she has been working towards Ph.D. in Chemistry at Purdue University. She is interested in high throughput experimentation and chemical technology for advancing synthetic methodology, telescoped continuous synthesis facilitated by organometallic reagents, and applications of electrochemistry in flow.

Yuta Moriuchi earned his B.S. degree in Chemistry in the Honors College at Purdue University in May 2021. He majored in Biochemistry and minored in Biology. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. degree in Chemistry at the University of California – San Diego. His research interests include drug design, drug development, and pharmaceutical sciences.

References:

- [1].(a) Campos KR, Coleman PJ, Alvarez JC, Dreher SD, Garbaccio RM, Terrett NK, Tillyer RD, Truppo MD, Parmee ER, Science 2019, 363, eaat0805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Troshin K, Hartwig JF, Science 2017, 357, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Buitrago Santanilla A, Regalado EL, Pereira T, Shevlin M, Bateman K, Campeau L-C, Schneeweis J, Berritt S, Shi Z-C, Nantermet P, Liu Y, Helmy R, Welch CJ, Vachal P, Davies IW, Cernak T, Dreher SD, Science 2015, 347, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shevlin M, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Granda JM, Donina L, Dragone V, Long D-L, Cronin L, Nature 2018, 559, 377–381; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Godfrey AG, Michael SG, Sittampalam GS, Zahoranszky-Kohalmi G, Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 1–6; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Eyke NS, Koscher BA, Jensen KF, Trends Chem. 2021. 3, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Isbrandt ES, Sullivan RJ, Newman SG, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 7180–7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kleiner RE, Dumelin CE, Liu DR, Chem Soc Rev 2011, 40, 5707–5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hayhow TG, Borrows REA, Diene CR, Fairley G, Fallan C, Fillery SM, Scott JS, Watson DW, Chem.-Eur. J 2020, 26, 16818–16823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jacques P, Béchet M, Bigan M, Caly D, Chataigné G, Coutte F, Flahaut C, Heuson E, Leclère V, Lecouturier D, Phalip V, Ravallec R, Dhulster P, Froidevaux R, Bioprocess Biosys. Eng 2017, 40, 161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Roberts EJ, Habas SE, Wang L, Ruddy DA, White EA, Baddour FG, Griffin MB, Schaidle JA, Malmstadt N, Brutchey RL, ACS Sustain. Chem. & Eng 2017, 5, 632–639. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hazemann P, Decottignies D, Maury S, Humbert S, Berliet A, Daniel C, Schuurman Y, Catal. Sci. Technol 2020, 10, 7331–7343. [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Clayson IG, Hewitt D, Hutereau M, Pope T, Slater B, Adv. Mater 2020, 32, 2002780; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hormozi Jangi SR, Akhond M, J. Chem. Sci 2020, 132, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- [12].(a) Mennen SM, Alhambra C, Allen CL, Barberis M, Berritt S, Brandt TA, Campbell AD, Castanon J, Cherney AH, Christensen M, Damon DB, Eugenio de Diego J, Garcia-Cerrada S, Garcia-Losada P, Haro R, Janey J, Leitch DC, Li L, Liu F, Lobben PC, MacMillan DWC, Magano J, McInturff E, Monfette S, Post RJ, Schultz D, Sitter BJ, Stevens JM, Strambeanu II, Twilton J, Wang K, Zajac MA, Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1213–1242; [Google Scholar]; (b) Welch CJ, React. Chem. Eng 2019, 4, 1895–1911. [Google Scholar]

- [13].(a) Nunn C, DiPietro A, Hodnett N, Sun P, Wells KM, Org. Process Res. Dev 2018, 22, 54–61; [Google Scholar]; (b) Biyani SA, Qi QQ, Wu JZ, Moriuchi Y, Larocque EA, Sintim HO, Thompson DH, Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 2240–2251. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ichiishi N, Moore KP, Wassermann AM, Wolkenberg SE, Krska SW, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee GM, Loechtefeld R, Menssen R, Bierer DE, Riedl B, Baker RT, Tett. Lett 2016, 57, 5464–5468. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Adlington NK, Agnew LR, Campbell AD, Cox RJ, Dobson A, Barrat CF, Gall MAY, Hicks W, Howell GP, Jawor-Baczynska A, Miller-Potucka L, Pilling M, Shepherd K, Tassone R, Taylor BA, Williams A, J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 4735–4747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ludwig JR, Simmons EM, Wisniewski SR, Chirik PJ, Org. Lett 2021, 23, 625–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jaman Z, Mufti A, Sah S, Avramova L, Thompson DH, Chem.-Eur. J 2018, 24, 9546–9554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].(a) Tu NP, Dombrowski AW, Goshu GM, Vasudevan A, Djuric SW, Wang Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 7987–7991; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Martin MC, Goshu GM, Hartnell JR, Morris CD, Wang Y, Tu NP, Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bahr MN, Morris MA, Tu NP, Nandkeolyar A, Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li T, Xu L, Xing Y, Xu B, Chem. Asian J 2017, 12, 190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Son Y, Lee S, Kim H-S, Eom MS, Han MS, Lee S, Adv. Synth. Catal 2018, 360, 3916–3923. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vandavasi JK, Newman SG, Synlett 2018, 29, 2081–2086. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Das UK, Clément R, Johannes CW, Robins EG, Jong H, Baker RT, Catal. Sci. Technol 2017, 7, 4599–4603. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Annand JR, Riehl PS, Schultz DM, Schindler CS, J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 9071–9079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mennie KM, Vara BA, Levi SM, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Greshock TJ, Moore KP, McClain RT, Bellomo A, Chung CK, Dreher SD, Kutchukian PS, Peng Z, Davies IW, Vachal P, Ellwart M, Manolikakes SM, Knochel P, Nantermet PG, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 13714–13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cherney AH, Hedley SJ, Mennen SM, Tedrow JS, Organometallics 2019, 38, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Noh H, Lim T, Park BY, Han MS, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 1703–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Engl PS, Tsygankov A, Silva JD, Lange JP, Coperet C, Togni A, Fedorov A, Helv. Chim. Acta 2020, 103, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Leitch DC, John MP, Slavin PA, Searle AD, Org. Process Res. Dev 2017, 21, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Larson H, Schultz D, Kalyani D, J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 13092–13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tcyrulnikov S, Curto JM, Gilmartin PH, Kozlowski MC, J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 12207–12212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Thanzeel FY, Balaraman K, Wolf C, Chem.-Eur. J 2019, 25, 11020–11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].(a) Herrera BT, Moor SR, McVeigh M, Roesner EK, Marini F, Anslyn EV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 11151–11160; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pilicer SL, Dragna JM, Garland A, Welch CJ, Anslyn EV, Wolf C, J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 10858–10864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shcherbakova EG, Brega V, Lynch VM, James TD, Anzenbacher P Jr., Chem.-Eur. J 2017, 23, 10222–10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Goyon A, Masui C, Sirois LE, Han C, Yehl P, Gosselin F, Zhang K, Anal. Chem 2020, 92, 15187–15193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Becica J, Hruszkewycz DP, Steves JE, Elward JM, Leitch DC, Dobereiner GE, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 8981–8986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sather AC, Martinot TA, Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1725–1739. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Guram AS, Org. Process Res. Dev 2016, 20, 1754–1764. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lu X, Roberts SE, Franklin GJ, Davie CP, MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1614–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Carter HL, Connor AW, Hart R, McCabe J, McIntyre AC, McMillan AE, Monks NR, Mullen AK, Ronson TO, Steven A, Tomasi S, Yates SD, React. Chem. Eng 2019, 4, 1658–1673. [Google Scholar]

- [43].(a) Chow SY, Nelson A, J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 3591–3593; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jaman Z, Logsdon DL, Szilágyi B, Sobreira TJP, Aremu D, Avramova L, Cooks RG, Thompson DH, ACS Comb. Sci 2020, 22, 184–196; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cernak T, Gesmundo NJ, Dykstra K, Yu Y, Wu Z, Shi ZC, Vachal P, Sperbeck D, He S, Murphy BA, Sonatore L, Williams S, Madeira M, Verras A, Reiter M, Lee CH, Cuff J, Sherer EC, Kuethe J, Goble S, Perrotto N, Pinto S, Shen DM, Nargund R, Balkovec J, DeVita RJ, Dreher SD, J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 3594–3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Laffoon SD, Chan VS, Fickes MG, Kotecki B, Ickes AR, Henle J, Napolitano JG, Franczyk TS, Dunn TB, Barnes DM, Haight AR, Henry RF, Shekhar S, ACS Catal 2019, 9, 11691–11708. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang D, Astruc D, Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46, 816–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shevlin M, Guan XY, Driver TG, ACS Catal 2017, 7, 5518–5522. [Google Scholar]

- [47].(a) Renom-Carrasco M, Lefort L, Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 5038–5060; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chan VS, Krabbe SW, Li C, Sun L, Liu Y, Nett AJ, ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 5748–5753. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Arenas I, Ferrali A, Rodríguez-Escrich C, Bravo F, Pericàs MA, Adv. Synth. Catal 2017, 359, 2414–2424. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wleklinski M, Loren BP, Ferreira CR, Jaman Z, Avramova L, Sobreira TJP, Thompson DH, Cooks RG, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 1647–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Loren BP, Ewan HS, Avramova L, Ferreira CR, Sobreira TJP, Yammine K, Liao H, Cooks RG, Thompson DH, Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Logsdon DL, Li YJ, Sobreira TJP, Ferreira CR, Thompson DH, Cooks RG, Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shaabani S, Xu R, Ahmadianmoghaddam M, Gao L, Stahorsky M, Olechno J, Ellson R, Kossenjans M, Helan V, Dömling A, Green Chem 2019, 21, 225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].DiRico KJ, Hua WY, Liu C, Tucker JW, Ratnayake AS, Flanagan ME, Troutman MD, Noe MC, Zhang H, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 11, 1101–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dong J, Fernández-Fueyo E, Hollmann F, Paul CE, Pesic M, Schmidt S, Wang Y, Younes S, Zhang W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 9238–9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Blincoe WD, Lin S, Dreher SD, Sheng H, Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131434. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bayly AA, McDonald BR, Mrksich M, Scheidt KA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2020, 117, 13261–13266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yayla HG, Peng F, Mangion IK, McLaughlin M, Campeau L-C, Davies IW, DiRocco DA, Knowles RR, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 2066–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Grainger R, Heightman TD, Ley SV, Lima F, Johnson CN, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 2264–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Vara BA, Li X, Berritt S, Walters CR, Petersson EJ, Molander GA, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Davies AV, Fitzpatrick KP, Betori RC, Scheidt KA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 9143–9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mastandrea MM, Canellas S, Caldentey X, Pericas MA, ACS Catal 2020, 10, 6402–6408. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sherwood TC, Xiao H-Y, Bhaskar RG, Simmons EM, Zaretsky S, Rauch MP, Knowles RR, Dhar TGM, J. Med. Chem 2019, 84, 8360–8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Betori RC, Scheidt KA, ACS Catal 2019, 9, 10350–10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].ElMarrouni A, Ritts CB, Balsells J, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 6639–6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Shah AA, Kelly MJ, Perkins JJ, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 2196–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Nicastri MC, Lehnherr D, Lam YH, DiRocco DA, Rovis T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 987–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bissonnette NB, Ryu KA, Reyes-Robles T, Wilhelm S, Tomlinson JH, Crotty KA, Hett EC, Roberts LR, Hazuda DJ, Jared Willis M, Oslund RC, Fadeyi OO, ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 3555–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mazuela J, Antonsson T, Knerr L, Marsden SP, Munday RH, Johansson MJ, Adv. Synth. Catal 2019, 361, 578–584. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Shevlin M, Friedfeld MR, Sheng H, Pierson NA, Hoyt JM, Campeau L-C, Chirik PJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3562–3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Christensen M, Nolting A, Shevlin M, Weisel M, Maligres PE, Lee J, Orr RK, Plummer CW, Tudge MT, Campeau L-C, Ruck RT, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Arrington K, Barcan GA, Calandra NA, Erickson GA, Li L, Liu L, Nilson MG, Strambeanu II, VanGelder KF, Woodard JL, Xie S, Allen CL, Kowalski JA, Leitch DC, J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 4680–4694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ring OT, Campbell AD, Hayter BR, Powell L, Tett. Lett 2020, 61, 151589. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Fier PS, Maloney KM, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 3033–3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Stevens JM, Parra-Rivera AC, Dixon DD, Beutner GL, DelMonte AJ, Frantz DE, Janey JM, Paulson J, Talley MR, J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 14245–14261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Thanzeel FY, Balaraman K, Wolf C, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Pilicer SL, Dragna JM, Garland A, Welch CJ, Anslyn EV, Wolf C, J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 10858–10864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Boga SB, Christensen M, Perrotto N, Krska SW, Dreher S, Tudge MT, Ashley ER, Poirier M, Reibarkh M, Liu Y, Streckfuss E, Campeau L-C, Ruck RT, Davies IW, Vachal P, React. Chem. Eng 2017, 2, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zultanski SL, Kuhl N, Zhong W, Cohen RD, Reibarkh M, Jurica J, Kim J, Weisel L, Ekkati AR, Klapars A, Gauthier DR, McCabe Dunn JM, Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, Ahead of Print.

- [79].Sabatini MT, Boulton LT, Sneddon HF, Sheppard TD, Nature Catal 2019, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ewan HS, Biyani SA, DiDomenico J, Logsdon D, Sobreira TJP, Avramova L, Cooks RG, Thompson DH, ACS Comb. Sci 2020, 22, 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA, Liu H, Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 2432–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].De Jesus Silva J, Ferreira MAB, Fedorov A, Sigman MS, Copéret C, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 6717–6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sezen-Edmonds M, Tabora JE, Cohen BM, Zaretsky S, Simmons EM, Sherwood TC, Ramirez A, Org. Process Res. Dev 2020, 24, 2128–2138. [Google Scholar]

- [84].(a) Singh S, Pareek M, Changotra A, Banerjee S, Bhaskararao B, Balamurugan P, Sunoj RB, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 2020, 117, 1339–1345; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ahneman DT, Estrada JG, Lin SS, Dreher SD, Doyle AG, Science 2018, 360, 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Gandeepan P, Müller T, Zell D, Cera G, Warratz S, Ackermann L, Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 2192–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]