Abstract

This study evaluated the in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of puerarin (PUE) and β-lactoglobulin (β-lg). The results of the in vitro antioxidant assay revealed that the DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging rates of the PUE/β-lg complex were generally superior to those of free PUE within the tested experimental concentration range. The in vivo antioxidant activity assay, using Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) as a model organism, showed that the PUE/β-lg complex significantly increased the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and reduced glutathione (GSH) content in C. elegans, and also increased the mean lifespan of C. elegans under oxidative and thermal stress conditions. Transcriptomic analysis showed that the PUE/β-lg complex regulated the mRNA expression levels of genes associated with the activation of various signaling pathways, such as the longevity regulation pathway, insulin signaling pathway, and GSH metabolism. Overall, this study demonstrated the potential of the PUE/β-lg complex as an antioxidant, which can lead to its development into food products or pharmaceuticals.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Biological techniques

Introduction

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a commonly used model organism in scientific studies, primarily due to its short life cycle, transparent body, and hermaphroditism and self-fertilization1. About 60–80% of the C. elegans genes are homologous to human genes and about 42–45% of human disease genes have homologs in the C. elegans genome. Also, due to its short lifespan, observable changes, and ability to increase its lifespan up to 10-fold, C. elegans is a useful model to study the effect of antioxidants on aging2. Therefore, currently, C. elegans is widely used in aging studies, especially in the study of aging-associated signaling pathways and transcription factors that regulate aging-related processes. The mechanisms regulating the lifespan of C. elegans involve multiple key signaling pathways, among which the insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway, mTOR pathway, AMPK pathway, autophagy pathway and heat shock protein response pathway have been thoroughly studied3–7. The IIS pathway is an important pathway in the regulation of the lifespan of nematodes. A study found that inhibiting the insulin-like receptor can extend the lifespan of nematodes. The pathway involves multiple transcription factors and signaling proteins, such as DAF-16 (a FOXO transcription factor), which plays an important role in regulating antioxidant activities, development, and aging8.

Puerarin (PUE) is a kind of isoflavonoid isolated from Pueraria lobata root, which has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, cholesterol-lowering, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, apoptosis-inhibiting, cell proliferation and differentiation-promoting, and cellular damage prevention or minimizing effects9–11. However, PUE has the drawbacks of poor water solubility and low bioavailability. Although it has been pointed out that macromolecule embedding technology can significantly increase the water solubility and use of PUE. Chen et al. prepared a complex of casein with flaxseed oil, which improved the oxidative stability of flaxseed oil12. Additionally, the antioxidant properties of gallic acid were improved by combining it with α-lactalbumin13. Wang et al. combined PUE with casein micelles and focused on evaluating their in vitro antioxidant activity as well as their in vitro release14. Zhong et al. prepared PUE complexes with isolated whey proteins and evaluated the stability, emulsification, and storage properties of the emulsion system15. Among various macromolecules, β-lactoglobulin (β-lg) is considered a good carrier due to its high affinity for small-molecule hydrophobic ligands, as well as its good nutritional value16,17.

Polyphenols, which are generally categorized into phenolic acids, flavonoids, and non-flavonoids, usually have good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In antioxidant studies performed in C. elegans models, a variety of active compounds may activate related signaling pathways associated with aging, and one class of chemicals may be involved in regulating multiple pathways. A reported study claimed that free and bound polyphenols in sugarcane tips were effective in increasing nematode survival and antioxidant enzyme activity18. Also, the phenolic compound paeonol was reported to promote longevity and fitness in C. elegans by activating the DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/Nrf2 transcription factors19. Populin (2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl β-D-glucopyranoside 6-benzoate) or apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) were found to extend C. elegans lifespan by regulating AAK-2/AMPK, DAF-16/FOXO, and SKN-1/Nrf220. In addition, ellagic acid was shown to increase stress resistance through the IIS pathway in C. elegans21.

However, few in vivo studies on small-molecule complexes with antioxidant activities have been reported. Therefore, in this study, the antioxidant activity of the PUE/β-lg complex in vivo was preliminarily investigated using transcriptomics approaches in a C. elegans model.

Results

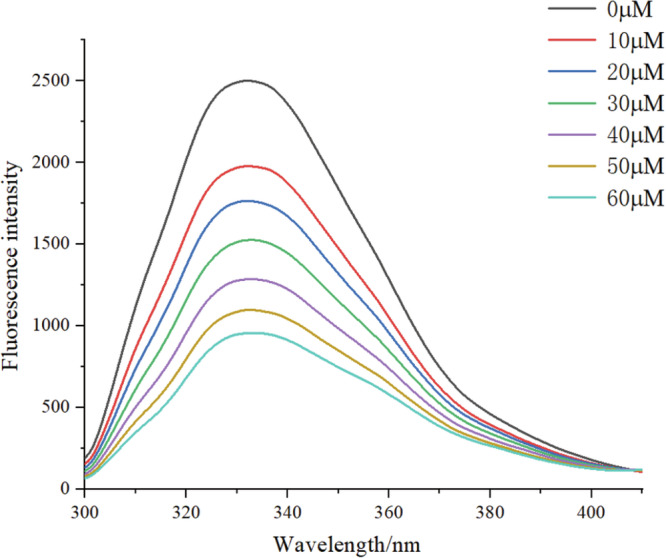

Fluorescence burst analysis of β-lg by PUE

As shown in Fig. 1, the maximum fluorescence emission peak of β-lg was at 332 nm, and, at the same concentration of β-lg, the fluorescence intensity showed a steady decrease with the increase of PUE concentration at the same concentration of β-lg, while the peak shape was unchanged, indicating that PUE and β-lg bound to each other and effectively quenched the endogenous fluorescence. The results also revealed that the maximum absorption peak was red-shifted by 2 nm, indicating that the fluorescence property of β-lg changed after the addition of PUE, and the protein polarity was increased, and the surface hydrophobicity was reduced22. Thus, fluorescence spectroscopy analyses demonstrated that PUE can bind to β-lg.

Fig. 1.

The fluorescence quenching of β–lg by PUE at different concentrations at 25 °C.

Molecular docking analysis

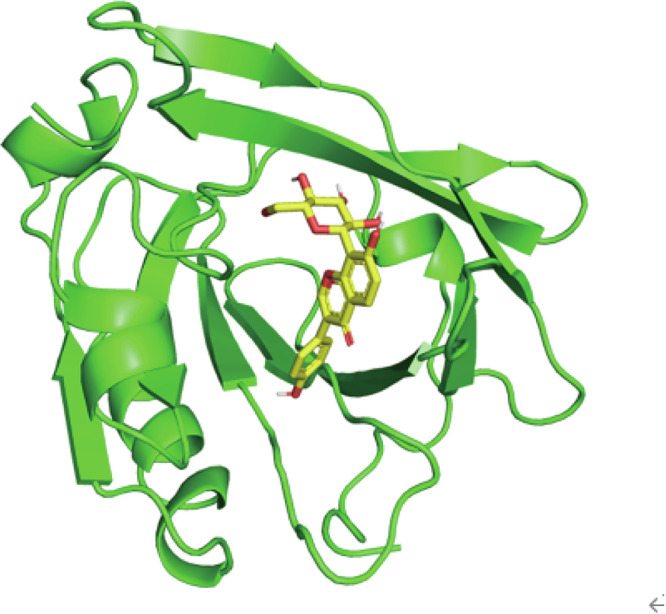

The binding between PUE and β-lg was simulated using AutoDock Vina. Molecular docking analysis revealed that PUE and β-lg bind with a minimum energy of −7.3 kcal/mol, and, as shown in Fig. 2, PUE is embedded in the hydrophobic cavity of β-lg, forming interactions with the surrounding amino acids, which is conducive to the formation of stable complexes. The planar two-dimensional (2D) diagram of the interaction between PUE and β-lg, shown in Fig. 3, reveals that the interaction force between PUE and β-lg consists of multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic forces. Six amino acids of β-lg, namely Leu39, Lys60, Asn90, Glu108, Ser116, and Leu117, form a cavity tightly wrapped around the PUE molecule, which generates a hydrophobic force, reducing water interference and favoring the formation of a stable complex. In addition, PUE formed five hydrogen bonds with Pro38, Lys69, Asn88, and Met107 of β-lg with bond lengths of 2.96, 2.88, 2.99, 2.97, and 2.95 Angstroms (Å), respectively. The formation of short hydrogen bonds promoted the formation of a stable complex between PUE and β-lg. Similarly, vanillic acid similarly formed short hydrogen bonds with Met107 and Lys69 when bound to β-lg23. Additionally, curcumin formed hydrophobic interactions with Pro38, Leu39, Val41, Leu58, Lys69, Ile71, Ile84, Asn88, Asn90, Met107, Glu108, Asn109, Ser116, and Leu117 upon binding to β-lg24.

Fig. 2. The structure of the complex between PUE and β-lg.

The yellow stick-like parts represent PUE, and the green lines represent β-lg.

Fig. 3.

Interactions between PUE and β-lg,  represents the ligand–bond,

represents the ligand–bond,  represents the non-ligand bond,

represents the non-ligand bond,  represents hydrogen bonds and their distances,

represents hydrogen bonds and their distances,  represents non-ligand residues involved in hydrophobic interactions,

represents non-ligand residues involved in hydrophobic interactions,  represents the corresponding atoms involved in hydrophobic interactions.

represents the corresponding atoms involved in hydrophobic interactions.

Assays of DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging rates

The most important factor affecting the oxidative stability of systemic complex emulsions is the content of phenolic hydroxyl groups, and polyphenols with a high content of phenolic hydroxyl groups usually have a higher free radical scavenging ability25. The energetic scavenging rates of DPPH and ABTS radicals by PUE and the PUE/β-lg complex are shown in Fig. 4, in which the horizontal coordinate shows the concentration of PUE. The β-lg at 0.5 mg/mL had some DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging ability with scavenging rates of 23.76 and 13.76%, respectively. The DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging rates of the complex increased with the concentration of PUE. After the combination of the two, the DPPH radical scavenging rate of the complex was always higher than the sum of the two scavenging rates. When the concentration of PUE was greater than 0.5 mM, the ABTS radical scavenging rate of the complex was less than the sum of PUE and β-lg. Overall, the free radical scavenging rate of the complex was better in the experimental concentration range, a possible reason for this is that the binding increases the solubility of PUE and favors the reaction of PUE with free radicals26. An increase in free radical scavenging ability has been reported for chlorogenic acid in combination with β-lg27.

Fig. 4. Radical scavenging activities of PUE and PUE/β-lg complex.

A The DPPH radical scavenging rate of PUE and the PUE/β-lg complex. B The ABTS radical scavenging rate of PUE and the PUE/β-lg complex. Different letters above each column indicate a significant difference between groups (p < 0.05).

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activities in C. elegans

As shown in Fig. 5, SOD activity and GSH level were increased to different degrees with different dose combinations. Groups 2 to 6 increased SOD activity by 1.27, 1.38, 1.30, 1.72, and 1.38 fold and GSH level by 1.12, 1.43, 1.28, 1.78, and 1.59 fold, respectively. The results in Fig. 5 also reveal that within the range of the concentration combinations in this experiment, the SOD activity and GSH level were higher in C. elegans treated with Group 5. Therefore, group 5 (50 μM PUE/β-lg complex) was selected as the treatment group for subsequent experimental analysis. A previous study showed that black wolfberry anthocyanins also significantly increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes in C. elegans28. β-lg contains many bioactive peptides that can be released by enzymatic protein hydrolysis in vivo or in vitro. Once released, these peptides play important roles in human health, including antihypertensive, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities, which may be the reason for the increase of the SOD activity and GSH content29.

Fig. 5. Effects on SOD activitiy and GSH content in each group.

The different letters in each set of columns indicate a significant difference between the two groups, p < 0.05.

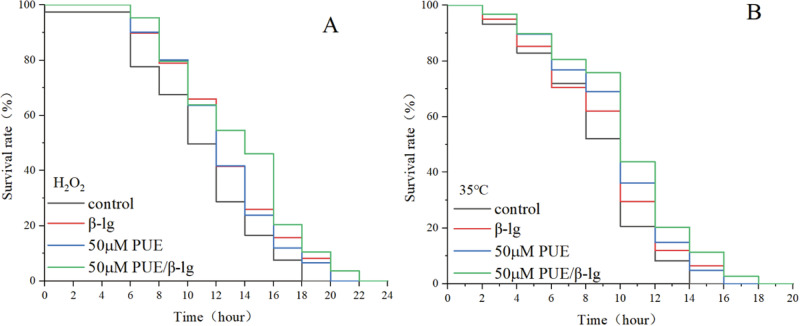

PUE and its complexes extended the lifespan of C. elegans under stress

C. elegans were subjected to oxidative or thermal stress, and the lifespan of C. elegans treated with different combinations of treatments was measured to determine whether the stress resistance of C. elegans could be enhanced. As shown in Fig. 6A, B, compared with the control group, all treatment groups were able to extend the lifespan of C. elegans under stress conditions. Among them, the PUE/β - lg complex treatment group had the most significant lifespan-extending effect. As shown in Table 1, under oxidative stress conditions, at 16 h, the survival rates of each group were 16.56, 25.85, and 23.84%, while the survival rate of the 50 μM PUE/β - lg complex treatment group reached 46.05%. As shown in Table 2, under heat stress conditions, at 18 h, the survival rates of all other groups were 0%, while the 50 μM PUE/β - lg complex treatment group still had 2.65% of C.elegans surviving. The results showed that under H2O2-induced oxidative stress, the average lifespan of the control group was 11.85 ± 1.23 h, while that of the groups treated with each combination was 13.51 ± 1.31, 13.35 ± 1.78, and 14.48 ± 1.12 h, which represented an extension of the lifespan by 14.03, 12.67, and 22.16%, respectively, relative to the control group. In addition, under heat stress conditions, the average lifespan of the control group was 9.57 ± 1.20 h, while that of the groups treated with each combination was 10.21 ± 0.98, 10.76 ± 1.39, and 11.42 ± 1.76 h, which represented an extension of the lifespan by 6.67, 12.3, and 19.2%, respectively, compared to the control group. The results revealed that the 50 μM PUE/β-lg complex had the optimal lifespan extension effect on C. elegans under oxidative or thermal stress conditions.

Fig. 6. Survival of C. elegans under oxidative and heat stress conditions.

A The survival rate of C. elegans under H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress. B The survival rate of C. elegans under heat stress.

Table 1.

Effect of oxidative stress on the lifespan of C. elegans in groups subjected to oxidative stress

| Group | Maximum life span (h) | Mean lifespan (h) (±SEM) | Number of worms | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 18 | 11.85 ± 1.23a | 157 | |

| β-lg | 20 | 13.51 ± 1.31b | 147 | <0.05 |

| 50 μM PUE | 20 | 13.35 ± 1.78b | 151 | <0.05 |

| 50 μM PUE/β-lg | 22 | 14.48 ± 1.26c | 151 | <0.001 |

Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of heat stress on the lifespan of C. elegans in groups subjected to heat stress

| Group | Maximum life span | Mean lifespan (h) (±SEM) | Number of worms | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 14 | 9.57 ± 1.20a | 146 | |

| β-lg | 16 | 10.21 ± 0.98b | 142 | <0.05 |

| 50 μM PUE | 16 | 10.76 ± 1.39b | 155 | <0.05 |

| 50 μM PUE/β-lg | 18 | 11.42 ± 1.76b | 128 | <0.05 |

Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

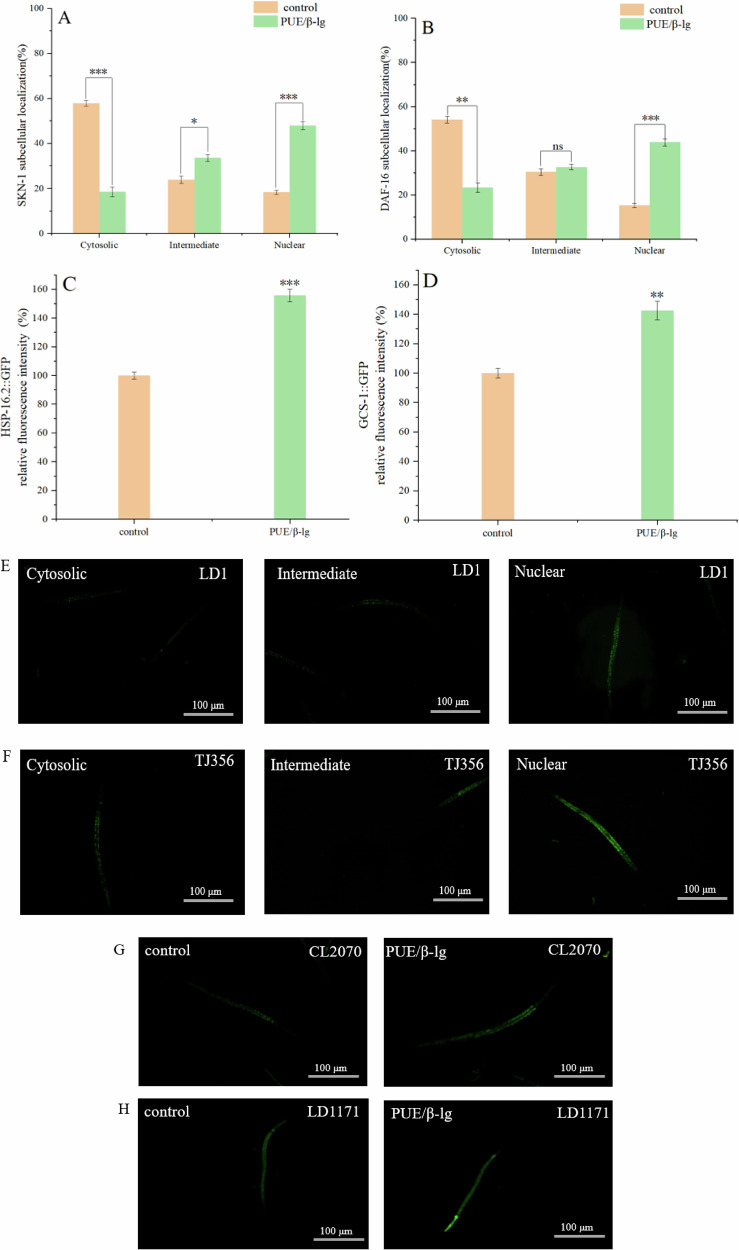

The effect of PUE/β-lg on C. elegans fluorescent mutants

In the PUE/β-lg complex treatment group, the percentage of SKN-1::GFP in the nucleus increased by 29.6% (Fig. 7A). A previous study suggested that paeonol can increase the antioxidant stress resistance of C. elegans by promoting skn-1 nucleation19. This is consistent with the finding that the PUE/β-lg complex can improve the survival rate of C. elegans under oxidative stress, as mentioned above. In the PUE/β-lg complex treatment group, the percentage of DAF-16::GFP in the nucleus increased by 28.5% (Fig. 7B). DAF-16 is an important transcription factor in the insulin pathway, associated with longevity. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis results indicate enrichment in the insulin signaling pathway and the longevity regulating pathway in worms. Similarly, under the PUE/β-lg complex treatment, the fluorescence intensity of HSP-16.2::GFP and GCS-1::GFP increased by 55.69 and 42.51%, respectively (Fig. 7C, D). These results indicate that the PUE/β - lg complex increases the protein expression levels of HSP - 16.2::GFP and GCS - 1::GFP. The gene hsp - 16.2 is associated with the stress response of nematodes. The stress experiments in this paper indicated that the PUE/β - lg complex can increase the survival rate of nematodes under stress conditions. The gene gcs - 1 is related to the metabolism of glutathione (GSH). The previous determination of glutathione content showed that the PUE/β - lg complex can enhance the GSH content in nematodes. Subsequent KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results showed enrichment in the GSH metabolism pathway. This finding is consistent with the trend of transcriptomic and antioxidant enzyme activity analyses in this study, suggesting that the PUE/β-lg complex may regulate the lifespan of C. elegans by enhancing antioxidant defense and regulating the insulin signaling pathway.

Fig. 7. Effects of different treatments on fluorescence mutants.

A Proportion of nuclear translocation of SKN-1::GFP. B Proportion of nuclear translocation of DAF-16::GFP. C Fluorescence intensity of HSP-16.2::GFP. D Fluorescence intensity of GCS-1::GFP. E Representative fluorescence images of SKN-1::GFP distribution in LD1 strains: cytosolic, intermediate, and nuclear. F Representative fluorescence images of DAF-16::GFP distribution in TJ356 strains: cytosolic, intermediate, and nuclear. G The fluorescent images and quantification of HSP-16.2::GFP expression in the CL2070 strain. H The fluorescent images and quantification of GCS-1::GFP expression in the LD1171 strain. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Sequencing sample quality control and alignment to reference transcriptome

The expression levels of the transcripts were quantitatively analyzed using the RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) expression quantification software30. The DEGs were selected based on the criteria of |log2FC| > 1 and P < 0.05 between the control group and the PUE/β-lg complex group. The volcano map of DEGs is shown in Fig. 8, and 412 genes were found to be statistically significantly differentially expressed in the PUE/β-lg complex treatment group compared to the control group, including 239 significantly upregulated genes and 173 significantly downregulated genes.

Fig. 8.

Volcano plot was generated to visualize the significant DEGs in the PUE/β-lg vs. Control group, where red dots represent upregulated genes and blue dots represent downregulated genes.

Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using the GOatools software, in which P < 0.05 indicated that the enriched GO functions were significant, and the top 20 enrichment results are displayed according to the degree of significance.

As shown in Fig. 9A, the GO functional enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were mainly involved in the regulation of neuronal action potential, negative regulation of potassium ion transport, regulation of nerve impulses, phospholipase hydrolase activity, the phospholipase C-activating dopamine receptor signaling pathway, negative regulation of 3’-UTR-mediated mRNA stabilization, and the p38MAPK pathway. The p38MAPK signaling pathway is one of the major signaling pathways regulating innate immunity in C. elegans31. For example, it has been reported that spikenard polysaccharides enhanced pathogen resistance in radiation-damaged C. elegans through the intestinal p38MAPK-SKN-1/AFT-7 pathway and stress response32. After GO functional annotation and enrichment analysis of DEGs using the GO database, the DEGs were classified according to biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions. The GO functional annotation (Fig. 9B) showed that the enriched biological processes were mainly related to catalytic activity, binding, molecular transducer activity, molecular function regulators, and ATP-dependent activities. Enriched cellular components mainly included protein-containing complex and cellular anatomical entities. Enriched molecular functions included cellular process, metabolic process, bioregulation, response to stimuli, multicellular organismal process.

Fig. 9. Functional annotation and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on GO and KEGGpathways.

A GO functional annotation and B enrichment analysis of DEGs. C KEGG pathway functional annotation and D enrichment analysis of DEGs. Under the premise of p adjust <0.05, the top 20 enriched pathways were selected. The size of the circle represents the number of genes enriched in the pathways, with larger circles indicating more genes. The color of the circle represents the P value, with a redder color indicating a P-adjust value closer to 0, which represents higher statistical significance.

To further conduct KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs, the 30 pathways with the highest enrichment level were extracted. The results in Fig. 9D reveal that a large number of genes are mainly enriched in the two major categories of Organismal Systems and Human Diseases. Notably, the DEGs in the treated groups were enriched in the longevity-regulated pathway, suggesting that the PUE/β-lg complex can influence C. elegans lifespan. In addition, DEGs were also significantly enriched in GSH metabolism, which is consistent with the previous finding that the complex was able to increase the activity of enzymes involved in GSH metabolism in C. elegans. It is also noteworthy that the DEGs were significantly enriched in thyroid hormone synthesis, insulin signaling pathway, and atherosclerosis. The insulin signaling pathway likewise serves as one of the major signaling pathways regulating innate immunity in C. elegans33. Rosavin has been shown to prolong nematode growth by activating the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway34. According to KEGG pathway functional annotation, human diseases are mainly associated with infectious disease bacteria and cancer. Biological systems are mainly related to Excretory system, Immune system, Development and regeneration, Endocrine system, Environmental adaptation, Nervous system, Sensory system, Aging, Circulatory system, and Digestive system. Cellular processes are mainly related to Cell growth and death. Environmental information processing is related to signal transduction. Genetic information is associated with protein processing, translation and folding, sorting, and degradation. Metabolism is associated with the biodegradation and metabolism of antibiotics and other amino acids.

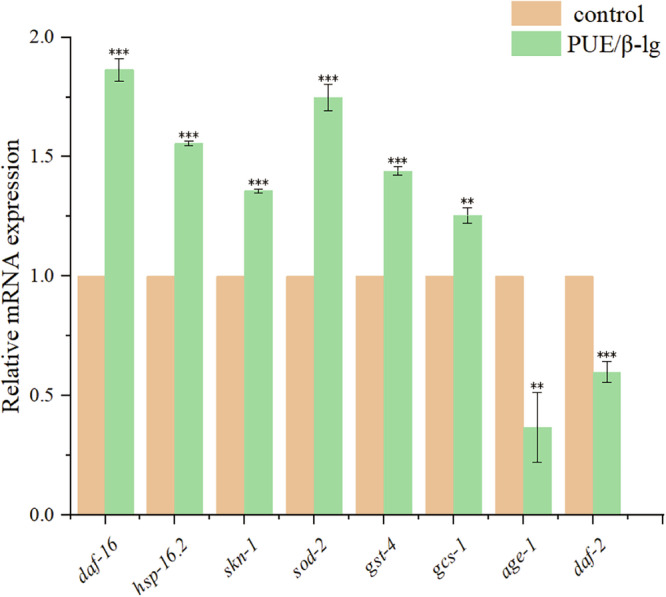

Validation of DEGs by qRT-PCR analysis

In order to verify the reliability and accuracy of the RNA-seq data, genes that were significantly differentially expressed compared to the control group were selected for further validation. Primers for these selected DEGs were synthesized with reference to the optimal primer sequences in the qPrimer DB-qPCR Primer database for use in quantitative analysis, and the results are shown in Fig. 10 In the RNA-seq data the expression levels of daf-16, hsp-16.2, skn-1, sod-2 and gcs-1 in the group treated with 50 μM PUE/β-lg complex were upregulated by 1.29-, 1.20-, 1.13-, 1.22- and 1.34-fold, respectively, and those of age-1 and daf-2 were downregulated by 0.45- and 0.62-fold, respectively. The verification of the expression levels of the above six genes by qRT-PCR revealed that daf-16, hsp-16.2, skn-1, sod-2 and gcs-1 were upregulated by 1.84-, 1.55-, 1.74-, 1.44- and 1.25-fold, respectively, while age-1 and daf-2 were downregulated by 0.64- and 0.41-fold, respectively, which were basically consistent with the RNA-seq results. Among these genes, daf-2 is an upstream gene of the insulin signaling pathway, and its downregulation indicates that the insulin pathway is inhibited. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs revealed that there were a large number of insulin pathway genes enriched. It has been reported that Lactobacillus plantarum dy-1-fermented barley extract, when fed to C. elegans, resulted in a significant reduction of daf-2 expression levels in C. elegans, reduced lipid deposition in C. elegans on a high-sugar diet, and mitigated the adverse effects of a high-sugar diet on the developmental, longevity, and locomotor behaviors of C. elegans35. It has also been reported that inhibition of daf-2 activates daf-16 and promotes the movement of daf-16 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, which broadly regulates the expression levels of downstream genes related to stress resistance, detoxification, and metabolism36. In the previous study, 50 μM PUE/β-lg improved the resistance to oxidative stress and heat stress in C. elegans36. Moreover, downregulation of the age-1 gene also contributes to the extension of C. elegans lifespan, and reduced age-1/PI3K signaling allows daf-16 to direct Duchenne larvae to stagnate and prolong the lifespan of adult animals37. As one of the heat shock proteins, hsp-16.2 is thermally stimulated to synthesize such proteins to protect itself when an organism is exposed to high temperatures. Activation of hsp-16.2 is beneficial to increasing the resistance of C. elegans to heat stress, consistent with the previous results. In addition, luteolin, which has been reported to inhibit the toxicity of Aβ in C. elegans, increases the expression level of hsp-16.2 by promoting the translocation of the transcription factor daf-16 into the nucleus and reduces the level of lipofuscin through its antioxidant activity and participates in the regulation of sterol metabolism pathways38. skn-1 enhances the resistance to oxidative stress and also prolongs the lifespan of C. elegans, and notably, the DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor (another major regulator of growth, metabolism, and senescence) activates the function of skn-139. In addition, VPRKL(Se)M can prevent Aβ-induced proteotoxicity by activating skn-140. Activation of gst-4 and gcs-1 promotes the activity of enzymes involved in GSH metabolism, and the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs are enriched in GSH metabolism41. The main role of sod-2 is to encode an intra-mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, and it has been reported that its expression is significantly increased by photoactivation of chrysin and sea buckthorn berry polysaccharide extracts42,43.

Fig. 10. Validation of RNA-seq DEGs by qRT-PCR gene expression analysis.

Statistical significance at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test.

Discussion

In the present study, fluorescence spectroscopy analysis and molecular docking analysis demonstrated that PUE and β-lg can bind through hydrophobic forces. The DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging rates of the PUE/β-lg complex were overall superior to those of PUE. Feeding PUE/β-lg to C. elegans increased the SOD activity and GSH levels in C. elegans, as well as the average lifespan of this nematode under the stressful conditions. In addition, transcriptomic data indicated that PUE/β-lg also regulated p38 MAPK, drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, GSH metabolism, insulin pathway, and longevity regulating pathway-worm to regulate C. elegans physiological functions. In addition, the regulatory effect of PUE/β - lg on C. elegans physiological functions was further confirmed by measuring the expression of relevant differential genes. Moreover, it was further confirmed that PUE/β-lg regulates the physiological functions of C. elegans by regulating the expression of genes related to the insulin signaling pathway, heat shock protein genes, and oxidative stress-related genes.

Methods

Materials

Puerarin (≥98%) and β-lactoglobulin (≥95%) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and hydrogen peroxide (>30%, w/w) were purchased from Shanghai Dingguo Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Both 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) were purchased from Beijing Biotopped Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The nematode strains used in this study were purchased from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and included N2 (wild-type, Bristol), TJ356 (zIs356IV [daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]), LD1 (ldIs7[skn-1b/c::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]), CL2070 (dvIs70 [hsp-16.2p::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]), and LD1171 (ldIs3 [gcs-1p::GFP + rol-6(su1006)]).

Fluorescence spectroscopy analysis

The fluorescence spectroscopy analyses were performed using a previously described method with slight modifications44. A certain amount of β-lg was dissolved in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) solution, aliquoted as a stock masterbatch solution of 5 mg/mL, and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C overnight to ensure full hydration. Also, a certain amount of PUE was dissolved in anhydrous ethanol. In the experiment, 1 mL of β-lg stock solution was mixed with 9 mL of PBS to dilute it to 0.5 mg/mL, and then different volumes of the PUE ethanol solution were mixed with the appropriate amount of ethanol to obtain the final addition volume of 60 μL. The total volume of ethanol in the complex was less than 5% (V/V), and it would have no effect on the structure of the proteins. The final concentrations of PUE were as follows: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 μM. Then, the complexes were heated in a water bath at 25 °C for 30 min. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded in the range of 300–410 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer with an excitation wavelength of 280 nm and excitation and emission slits of 5 nm.

Molecular docking

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of β-lg (PDB ID: 3NPO) was obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RSCB) Protein Data Bank (PDB) database, and the 3D structure of PUE (PubChem ID: 5281807) was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) PubChem Small Molecule Database, and the small molecule was downloaded and then converted to the PDB format using OpenBabel45. Before the start of docking, β-lg was dehydrogenated and converted to pdbqt format using the Autodock tools software. For PUE, hydrogenation was also performed, the twist key was set and converted to pdbqt format. With β-lg as the receptor and PUE as the ligand, the docking box size was set to 50 × 40 × 40 Å, the center coordinates were x = −14.744, y = 4.172, and z = 3.461, and the docking interval was set to 1 Å. Twenty dockings were performed during the docking process. The docking type was semi-flexible docking, and the default settings were used for the remaining parameters. Autodock Vina was used for conformational search during docking, using the lowest energy conformation as the optimal conformation46. The Pymol software package was used to draw the docking 3D map, and Ligplot+ was used to analyze the interaction forces47.

Measurement of the DPPH radical scavenging rate

A 2 mL aliquot of sample solution (β-lg at 0.5 mg/mL and PUE at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25 mM) was added to 2 mL of a 5 × 10−5 mol/L DPPH ethanol solution, shaken well, and then allowed to stand at room temperature and in the dark for 20 min. The absorbance value of the supernatant was measured at 517 nm and was recorded as A1; an equal volume of ethanol was substituted for the DPPH solution, and was recorded as A2; an equal volume of water was substituted for the sample solution, and was zeroed out. An equal volume of water was used to replace the sample solution as A0, and an equal volume of a mixture of water and ethanol was used to zero the DPPH radical scavenging rate48. The DPPH radical scavenging rate was calculated as follows:

| 1 |

Measurement of the ABTS radical scavenging rate

The ABTS radical solution was prepared by mixing 7 mM ABTS solution and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate solution in equal volume and incubated in the dark conditions for 12–16 h. The ABTS radical solution was diluted with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) until the absorbance at 734 nm reached 0.7 ± 0.02. This absorbance value was denoted as A0, and then the solution was ready for use. Take 60 μL of complex solution (β-lg at 0.5 mg/mL and PUE at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25 mM), add 3 mL of ABTS dilution, and react for 6 min at room temperature to determine the absorbance value A at 734 nm49. The scavenging rate was calculated using the following formula:

| 2 |

Synchronization and culture of C. elegans

C. elegans in the spawning stage were washed from the nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plate seeded with live E. coli OP50 and placed into a 1.5-mL centrifuge tube with M9 medium. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and nematodes were washed three times with M9 medium to remove bacteria adhering to the nematodes. Then, after adding 1 mL of C. elegans suspension into a centrifuge tube, the suspension was rapidly and vigorously shaken for 15 min until the worm bodies were completely lysed, and the tube was centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 1 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was resuspended in M9 medium and washed and centrifuged four times. Subsequently, the supernatant was removed, and the precipitate was resuspended in 1 mL of M9 medium, and the suspension was mixed well. Then, we waited for the C. elegans to hatch to become larvae for subsequent use. The liquid culture method described by Solis et al.50. was used, as follows: After adding 300 μL of S-complete medium into each well (where different dosing groups were set), the 24-well plates were placed in a constant-temperature incubator at 20 °C for static incubation. Then, C. elegans synchronized to the L4 stage were picked and added into S-complete medium added with FudR (150 μM), the inactivated E. coli OP50 (65 °C for 30 min), about 300 worms were added per well, and the time of picking C. elegans was set as day 0. The plates were sealed and placed into an incubator at 20 °C for incubation.

Antioxidant enzyme activity assays

Six feeding groups of C. elegans worms were set up as shown in Table 3, using the same volume of A and B mixed before feeding. PUE was dissolved in DMSO, and β-lg was dissolved in PBS solution. The concentrations in the table are final concentrations. After 3 days of treatment, the C. elegans in the medium of each treatment group were rinsed with saline and collected in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes. The C. elegans to be tested were washed repeatedly several times with saline, either by natural sedimentation of the C. elegans for 5–10 min or by centrifugation using a centrifuge at a low speed for 1 min to settle the worms. Subsequently, the supernatant was aspirated in order to remove the impurities, 1 mL of pre-cooled saline at 4 °C was added to the tube, and then the worms were placed on ice to crush them with a homogenizer. The homogenate was passed through a strainer and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected and transferred to a new centrifuge tube and stored at 4 °C. Afterwards, the total protein content of the supernatant was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, and the SOD activity and glutathione (GSH) content were determined using commercial kits following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the best combination was selected for subsequent experiments.

Table 3.

Combination of feeding C. elegans

| Groups | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | DMSO | PBS |

| Group 2 | DMSO | 15 μg/mL β-lg |

| Group 3 | 50 μM PUE | PBS |

| Group 4 | 100 μM PUE | PBS |

| Group 5 | 50 μM PUE | 15 μg/mL β-lg |

| Group 6 | 100 μM PUE | 15 μg/mL β-lg |

Oxidative stress resistance assays

C. elegans were cultured until the 7th day of adulthood, and the worms from different treatment groups were collected and washed three times with M9 medium to remove adherent bacteria, and then transferred to 96-well plates containing 100 μL of M9 medium with H2O2 at a final concentration of 1 mmol/L in each well, and then plates were left to stand in the dark at room temperature. The survival was recorded every 2 h until all worms died.

Heat stress resistance assays

C. elegans were cultured until the 7th day of adulthood, and the worms from different treatment groups were collected and washed three times with M9 medium to remove adherent bacteria, then transferred to 96-well plates with M9 medium (preheated at 25 °C for 2 h in advance), and the worms were placed in an incubator at a constant temperature of 35 °C to continuously undergo heat stress. The survival was recorded every 2 h until all C. elegans died.

Fluorescence analysis of transgenic strains

Four different C. elegans strains, namely LD1, CL2070, TJ356, and LD1171, were used to determine the expression levels of SKN-1, HSP-16.2, DAF-16, GCS-1 proteins. The transgenic and fluorescently-labeled mutant C. elegans were cultured and stimulated by administering drugs. After that, C. elegans in the young adult stage were collected, washed three times with M9 medium to remove impurities, and then anesthetized with NaN₃, and then imaged by fluorescence microscopy after placing the C. elegans worms under an orthogonal fluorescence microscope. Subsequently, the fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software to determine the protein expression levels.

Transcriptome sequencing

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis was performed by Shanghai Meiji Bio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was extracted and evaluated for quality. Then, after mRNA enrichment and fragmentation, cDNA was synthesized, subjected to adapter ligation and purification. Then, cDNA fragments of 400–500 bp were selected to prepare the cDNA libraries. Sequencing libraries were subsequently sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Hidradenitis elegans cryptic rod C. elegans genomic data were used as reference. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the following criteria: |log2FC| > 1 and p < 0.05.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from worms from the different treatment groups. cDNA was synthesized using the Tiangen FastKing RT (with gDNAase) kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The qRT-PCR gene expression analysis was performed on a QuantStudio™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) using the SuperReal PreMix Plus (SYBR Green) kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). The results were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method with act-1 as the internal reference gene51.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For multiple comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank test, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Education Department of Hubei Province (Q20234303) and the Key Project of Jingmen City, Key Technology and Application of Pueraria Enzyme (2023YFZD017).

Author contributions

B.M.: Data curation; Project administration; Methodology; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft. Y.M.: Methodology; Investigation and data curation; Formal analysis. Y.X.: Methodology; data curation. D.Z.: Resources; Formal analysis; Writing—review and editing. R.L.: Resources; Writing—Review and Editing. Y.H. and F.L.: Conceptualization; Resources; Supervision; Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data on which the findings of this study are based can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rong Li, Email: lirong2022@jcut.edu.cn.

Yechuan Huang, Email: hyc2005@sina.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41538-025-00534-4.

References

- 1.Zhuang, J. J. & Hunter, C. P. RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans: uptake, mechanism, and regulation. Parasitology139, 560–573 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, S. S. Whole genome RNAi screens for increased longevity: important new insights but not the whole story. Exp. Gerontol.41, 968–973 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A. & Tabtiang, R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature366, 461–464 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong, J.-H. et al. A new AMPK isoform mediates glucose-restriction induced longevity non-cell autonomously by promoting membrane fluidity. Nat. Commun.14, 288 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vellai, T. et al. Genetics: influence of TOR kinase on lifespan in C. elegans. Nature426, 620–620 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melendez, A. et al. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science301, 1387–1391 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu, A.-L., Murphy, C. T. & Kenyon, C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science300, 1142–1145 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapierre, L. R. & Hansen, M. Lessons from C. elegans: signaling pathways for longevity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab.23, 637–644 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou, Y.-X., Zhang, H. & Peng, C. Puerarin: a review of pharmacological effects. Phytother. Res.28, 961–975 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong, K. H., Li, G. Q., Li, K. M., Razmovski-Naumovski, V. & Chan, K. Kudzu root: traditional uses and potential medicinal benefits in diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol.134, 584–607 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, Z., Lam, T.-N. & Zuo, Z. Radix puerariae: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J. Clin. Pharmacol.53, 787–811 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, F. et al. Inhibition of lipid oxidation in nanoemulsions and filled microgels fortified with omega-3 fatty acids using casein as a natural antioxidant. Food Hydrocoll.63, 240–248 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, X. Y. et al. Covalent complexation and functional evaluation of (-)-epigallocatechin gallate and α-lactalbumin. Food Chem.150, 341–347 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, Y., Yang, M., Qin, J. & Wa, W. Interactions between puerarin/daidzein and micellar casein.J. Food Biochem.46, e14048 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong, Y. J. et al. Fabrication of oil-in-water emulsions with whey protein isolate-puerarin composites: environmental stability and interfacial behavior. Foods10, 705 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieserling, H. et al. Protein-phenolic interactions and reactions: discrepancies, challenges, and opportunities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.23, 70015 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomas, M. et al. Recent progress in promoting the bioavailability of polyphenols in plant-based foods, Critical Rev. Food Sci. Nutrition. 10.1080/10408398.2024.2336051. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Huang, Q. et al. A comparative evaluation of the composition and antioxidant activity of free and bound polyphenols in sugarcane tips. Food Chem.463, 141510 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, R. et al. Paeonol promotes longevity and fitness in Caenorhabditis elegans through activating the DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/Nrf2 transcription factors. Biomed. Pharmacother.173, 116368 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng, Y. et al. Transient inhibition of mitochondrial function by chrysin and apigenin prolong longevity via mitohormesis in C.elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med.203, 24–33 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai, S. et al. Ellagic acid increases stress resistance via insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Molecules 27, 6168 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Tang, S. Y. et al. Mildly preheating induced conformational changes of soy protein isolates contributed to the binding interaction with blueberry anthocyanins for stabilization. Food Hydrocoll.155, 110209 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, R. & Jia, W. Deciphering the competitive binding interaction of β-lactoglobulin with benzaldehyde and vanillic acid via high-spatial-resolution multi-spectroscopic. Food Hydrocoll.141, 108724 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu, J. et al. A joint experimental and theoretical investigation of the binding mechanism between zein and folic acid in an ethanol-water solution. Int. J. Food Prop.27, 729–749 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng, Y. et al. Molecular mechanisms and applications of polyphenol-protein complexes with antioxidant properties: a review. Antioxidants12, 1577 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solghi, S. Emam-Djomeh, Z. Fathi M. & Farahani, F. The encapsulation of curcumin by whey protein: assessment of the stability and bioactivity. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43.

- 27.Liu, J. et al. Ultrasound-assisted assembly of β-lactoglobulin and chlorogenic acid for non covalent nanocomplex: fabrication, characterization and potential biological function. Ultrason. Sonochem.86, 106025 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, Q., Zheng, B., Li, T. & Liu, R. H. Black goji berry anthocyanins extend lifespan and enhance the antioxidant defenses in Caenorhabditis elegans via the JNK-1 and DAF-16/FOXO pathways. J. Sci. Food Agric.105, 2282–2293 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez-Ledesma, B., Recio, I. & Amigo, L. β-lactoglobulin as source of bioactive peptides. Amino Acids35, 257–265 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. Bmc Bioinforma.12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chikka, M. R., Anbalagan, C., Dvorak, K., Dombeck, K. & Prahlad, V. The mitochondria-regulated immune pathway activated in the C. elegans intestine is neuroprotective. Cell Rep.16, 2399–2414 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, M. et al. Acanthopanax senticosus polysaccharide enhances the pathogen resistance of radiation-damaged Caenorhabditis elegans through intestinal p38 MAPK-SKN-1/ATF-7 pathway and stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 5034 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Panowski, S. H. & Dillin, A. Signals of youth: endocrine regulation of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab.20, 259–264 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, L. et al. Rosavin extends lifespan via the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans, Naunyn-Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol.397, 5275–5287 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, J. Y. et al. Barley protein LFBEP-C1 from lactiplantibacillus plantarum dy-1 fermented barley extracts by inhibiting lipid accumulation in a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Biomed. Environ. Sci.37, 377–386 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang, M. et al. H3K9me1/2 methylation limits the lifespan of daf-2 mutants in C. elegans. Elife11, e74812 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Gami, M. S., Iser, W. B., Hanselman, K. B. & Wolkow, C. A. Activated AKT/PKB signaling in C. elegans uncouples temporally distinct outputs of DAF-2/insulin-like signaling. BMC Dev. Biol.6, 45–45 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao, Y. et al. Luteolin promotes pathogen resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans via DAF-2/DAF-16 insulin-like signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol.115, 109679 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tullet, J. M. A. et al. The SKN-1/Nrf2 transcription factor can protect against oxidative stress and increase lifespan in C. elegans by distinct mechanisms. Aging Cell16, 1191–1194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen, M. et al. SKN-1 is indispensable for protection against Aß-induced proteotoxicity by a selenopeptide derived from Cordyceps militaris. Redox Biol.70, 103065 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Helmcke, K. J. & Aschner, M. Hormetic effect of methylmercury on Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.248, 156–164 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimakova, P. et al. Photoactivated hypericin increases the expression of SOD-2 and makes MCF-7 cells resistant to photodynamic therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother.85, 749–755 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, X. et al. Seabuckthorn berry polysaccharide extracts protect against acetaminophen induced hepatotoxicity in mice via activating the Nrf-2/HO-1-SOD-2 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine38, 90–97 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, Z. et al. Probing the mechanism of interaction between capsaicin and myofibrillar proteins through multispectral, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation methods. Food Chem.-X18, 100734 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform.3, 33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. Software news and update autodock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.31, 455–461 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model.51, 2778–2786 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mensor, L. L. et al. Screening of Brazilian plant extracts for antioxidant activity by the use of DPPH free radical method. Phytother. Res. PTR15, 127–130 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rice-Evans, C. A., Miller, N. J. & Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med.20, 933–956 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solis, G. M. & Petrascheck, M. Measuring Caenorhabditis elegans life span in 96-well microtiter plates. J. Vis. Exp.10.3791/2496. (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data on which the findings of this study are based can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.