Abstract

Background

Tetraspanins (TSPANs) are a critical family for cell migration, which have been implicated in a variety of activities including cancer. Previous study showed that tetraspanin 9 (TSPAN9) plays an important role in gastric cancer. In this study, we aim to explore the biological functions of TSPAN9 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) and Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) databases were used to analyze TSPAN9 expression, prognostic mutations, somatic copy number alterations (sCNAs), and tumor immune characteristics in 33 tumors. Immunohistochemistry images of TSPAN9 in HCC tissues were obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter database. The proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities of HCC cells were assessed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8), wound healing, and Transwell assays.

Results

TSPAN9 was deregulated in various tumor types, and its expression was lower in HCC tissues than that of normal liver tissues (P<0.05). Moreover, TSPAN9 expression had a correlation with the prognosis of tumor patients, and HCC patients with low TSPAN9 expression showed a poor prognosis (Log-rank P<0.05). In addition, we detected that TSPAN9 was significantly decreased in HCC cells (P<0.01). As compared to the control cells, overexpression of TSPAN9 in HCC cells significantly reduced cell proliferation, slowed the wound healing rate, and inhibited the invasive and migration ability (all P<0.05). TCGA database analysis revealed a relationship between the expression of TSPAN9 and epithelium-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) factors.

Conclusions

Downregulated expression of TSPAN9 indicates a poor prognosis of HCC patients. TSPAN9 can inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), tetraspanin 9 (TSPAN9), prognosis, proliferation, metastasis

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Downregulated expression of tetraspanin 9 (TSPAN9) indicates a poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. TSPAN9 can inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells.

What is known and what is new?

• Tetraspanins are a critical family for cell migration, which have been implicated in a variety of activities including cancer. Previous study showed that TSPAN9 plays an important role in gastric cancer.

• We detected that TSPAN9 was significantly decreased in HCC cells. As compared to the control cells, overexpression of TSPAN9 in HCC cells significantly reduced cell proliferation, slowed the wound healing rate, and inhibited the invasive and migration ability. We also found a relationship between the expression of TSPAN9 and epithelium-mesenchymal transformation factors.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Our findings will not only contribute to understanding the mechanism of TSPAN9 in HCC metastasis, but also provide new targets for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a prevalent malignant tumor of the digestive system. HCC accounts for approximately 7.8% of all cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). According to recent reports, Guangxi is an area with high HCC incidence rate in China, with HCC mortality ranking first among all cancer deaths in the region, accounting for approximately 25.8% of all malignancies (2). However, the precise pathogenic mechanism of HCC remains not fully understood, and there is still a lack of effective molecular markers for early diagnosis and prognosis prediction of disease progression (3,4). Additionally, HCC often has an insidious onset and high malignancy, with most patients already in the intermediate or advanced stages at the time of diagnosis. The high invasiveness, metastasis, recurrence rate, and short survival time of HCC have been persistent clinical challenges and focal points (5,6). Therefore, the biomarker search for effective early diagnosis and prognosis of HCC will provide new insights for targeted therapies and personalized treatment.

Malignant metastasis of HCC represents a serious medical issue, particularly in the advanced stages of the disease. Metastasis, the process by which tumor cells spread to other parts of the body beyond the primary tumor site, is especially prevalent in HCC and significantly impacts the prognosis and life quality of patients (7,8). Scientists have identified various proteins and molecular pathways that play crucial roles in determining the aggressiveness and metastatic potential of the tumor (9,10). The tetraspanins (TSPANs; also known as TM4SF) superfamily comprises a series of membrane proteins with similar structures, defined by their four transmembrane domains, and has been implicated in various cellular processes (11). These proteins interact with multiple other membrane proteins (such as integrins, growth factor receptors, and other transmembrane proteins) by forming a complex network, termed the “tetraspanin web”. This interaction regulates intracellular signaling, cellular structural stability, cell adhesion, migration, and other biological processes (12-14). Studies have shown that TSPANs can indirectly regulate metastasis by mediating cell interactions in the immune system via exosomes (15,16). Several TSPANs, potential targets for tumor therapy, have demonstrated promising effects in preclinical models of tumor progression and metastasis (17).

Tetraspanin 9 (TSPAN9; formerly known as NET-5), an important member of the TSPAN superfamily, is primarily distributed in TSPAN-enriched microdomains of membrane receptors and signaling proteins in megakaryocytes, platelets, and hematopoietic cells. It has been found that TSPAN9 is involved in cell migration, intercellular signaling, immune responses, tumor progression, and metastasis (18). Our previous study indicates that the AL139383.1-hsa-miR-9-5p axis is an upstream non-coding RNA (ncRNA)-related pathway most associated with TSPAN9 in HCC. Low expression of TSPAN9 in HCC is associated with high levels of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (19). However, the specific role of TSPAN9 in HCC has not been explored.

To further explore the biological functions of TSPAN9 in HCC, we performed quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8), wound healing, and Transwell assay to measure the effects of TSPAN9 overexpression on the proliferation and metastasis of liver cancer cells. Moreover, we analyzed the correlation between TSPAN9 expression with HCC progression and prognosis. Our research will not only contribute to understanding the mechanism of TSPAN9 in HCC metastasis, but also provide new targets for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC. We present this article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-2025-174/rc).

Methods

Bioinformatics analyses

The bioinformatics analyses of TSPAN9 in different tumors were conducted according to the previous study (20). Briefly, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data were downloaded from the online website University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC XENA; https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/), and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). The differential expression of TSPAN9 was analyzed in 33 tumors by the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/). The correlation between TSPAN9 expression and survival in pan-cancer (http://dna00.bio.kyutech.ac.jp/PrognoScan/index.html) was analyzed. The prognostic value of TSPAN9 expression in HCC was analyzed using Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/). Immunohistochemical images of TSPAN9 protein levels were obtained through an online Human Protein Atlas (HPA; http://www.proteinatlas.org/) database. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Cell lines and culturing

Human normal liver immortal cells THLE-3 and liver cancer cells (HepG2, SK-Hep-1, Huh-7, and MHCC-97H) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, El Paso, TX, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; OriCell, Guangzhou, China) was used to culture the cells. The cells were placed in an incubator for culturing at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2.

Plasmid and cell transfection

The overexpression plasmid for TSPAN9 was synthesized into GV658-puro vector by Genechem (Shanghai, China). The plasmids were transiently transfected using the Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and the efficiency was observed under a fluorescence microscope.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen) to synthesize cDNA. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed using TB Green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Tli RNaseH Plus) kit from Takara (Beijing, China). TSPAN9 primer sequences for qRT-PCR were as follows: F: 5'-GGTCATTGCCATAGGCACCAT-3', R: 5'-CCACGTTGTTCTCGGTGTG-3'. E-cadherin (CDH1) primer sequences for qRT-PCR were F: 5'-CTTCTGCTGATCCTGTCTGATG-3', R: 5'-TGCTGTGAAGGGAGATGTATTG-3'. N-cadherin (CDH2) primer sequences for qRT-PCR were F: 5'-GACAGTTCCTGAGGGATCAAAG-3', R: 5'-CGATTCTGACCTCAACATCCC-3'. Catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) primer sequences for qRT-PCR were F: 5'-ACTACCACAGCTCCTTCTCT-3', R: 5'-AAATCCCTGTTCCCACTCATAC-3'. Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) primer sequences for qRT-PCR were F: 5'-CAGCTTGATACCTGTGAATGGG-3', R: 5'-TATCTGTGGTCGTGTGGGACT-3'. GAPDH were used as internal controls, with primer sequences as follows: F: 5'-CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT-3', R: 5'-GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT-3'.

CCK-8 assay

Cell proliferation was measured using CCK-8 from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. After cell treatment for 12, 24, 48, and 72 h, CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. The optical density (OD) value at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader to calculate cell proliferation.

Cell migration and invasion detection

The ability of cell migration and invasion was detected by wound healing and Transwell assay, which were conducted by the previous published methods (21).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 28.0 and GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. Quantitative data were described as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and pairwise comparisons were performed using the t-test. Survival analysis was performed using the Log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Pan-cancer analysis of TSPAN9

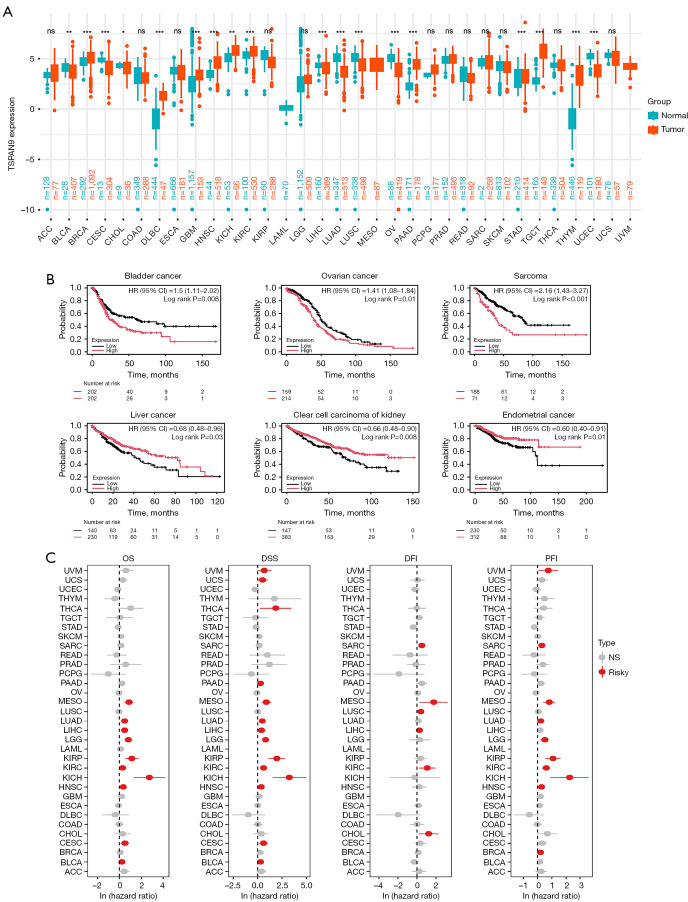

Analysis of TSPAN9 expression in pan-cancer tissues was conducted from TCGA and GTEx databases. As shown in Figure 1A, TSPAN9 exhibited significant high expression in 9 tumors (breast invasive carcinoma—BRCA, lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B cell lymphoma—DLBC, glioblastoma—GBM, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma—HNSC, kidney chromophobe—KICH, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma—KIRC, pancreatic adenocarcinoma—PAAD, testicular germ cell tumor—TGCT, and thymoma—THYM) and low expression in 8 tumors (bladder urothelial carcinoma—BLCA, cervical squamous cell carcinoma—CESC, cholangiocarcinoma—CHOL, liver hepatocellular carcinoma—LIHC, lung adenocarcinoma—LUAD, lung squamous cell carcinoma—LUSC, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma—OV, and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma—UCEC). The association between TSPAN9 expression and prognosis of patients in various tumors was assessed using Kaplan-Meier Plotter. High TSPAN9 expression correlated with poor prognosis in bladder cancer, ovarian cancer, and sarcoma, while low expression was related to poor prognosis in liver cancer, renal clear cell carcinoma, and endometrial carcinoma (Figure 1B). Univariate Cox analysis of TSPAN9 expression in 33 tumors revealed that high TSPAN9 expression posed a risk for mesothelioma (MESO) and KIRC (all hazard ratios >1, all P<0.05, Figure 1C). These findings indicate dysregulated TSPAN9 expression in tumor tissues, with implications for prognosis of tumor patients.

Figure 1.

The expression level and prognostic value of TSPAN9 in 33 tumors. (A) The expression of TSPAN9 in pan-cancer was analyzed according to TCGA and GTEx database. (B) Relationship between TSPAN9 expression and tumor prognosis. (C) Prognostic value of TSPAN9 in pan-cancer based on TCGA database. ns, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; CI, confidence interval; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; DFI, disease-free interval; DLBC, lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B cell lymphoma; DSS, disease-specific survival; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; KICH, kidney chromophobe; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MESO, mesothelioma; NS, not significant; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; OS, overall survival; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PFI, progression-free interval; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumor; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; THYM, thymoma; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma; UVM, uveal melanoma.

TSPAN9 expression was related with mutations, somatic copy number alterations (sCNAs) and immunity in different tumors

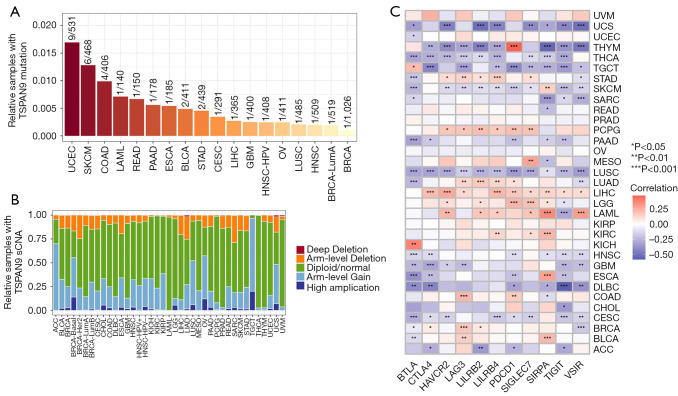

To investigate the impact of TSPAN9 expression in tumors, we initially examined the association between TSPAN9 expression, mutations, and sCNA in 33 tumors through the TIMER database. Diploid status, arm-level gain, and arm-level deletion were identified as prevalent mutation types among various cancers, collectively representing a substantial proportion. Among the tumors analyzed, UCEC, skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), and acute myeloid leukemia (LAML) exhibited the highest mutation frequencies (Figure 2A,2B).

Figure 2.

Association analysis of TSPAN9 expression with tumor mutations, somatic copy number changes, and immunity in pan-cancer. (A) Percentage of TSPAN9 mutation samples. (B) Somatic copy number changes in the tumor immune assessment resource database. (C) Correlation analysis between immune checkpoint genes and TSPAN9 expression. ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DLBC, lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B cell lymphoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; KICH, kidney chromophobe; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LILRB2, leukocyte immunoglobulin like receptor B2; LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin like receptor B4; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MESO, mesothelioma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PDCD1, programmed cell death 1; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SIGLEC7, sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 7; SIRPA, signal regulatory protein alpha; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; sCNA, somatic copy number alteration; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumor; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; THYM, thymoma; TIGIT, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma; UVM, uveal melanoma; VSIR, V-set immunoregulatory receptor.

Subsequently, we assessed eleven common immune checkpoint genes for their relationship with TSPAN9 expression. Our findings revealed a positive correlation between TSPAN9 expression levels and several immune checkpoint genes in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), LIHC, brain lower grade glioma (LGG), and LAML tumors (Figure 2C). These results suggest a potential involvement of TSPAN9 expression in tumor pathogenesis through its influence on tumor mutations, sCNAs, or immune responses.

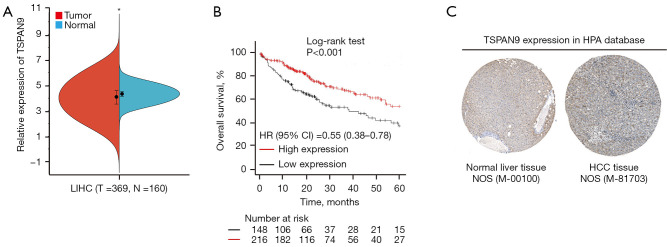

Expression of TSPAN9 in HCC and its prognostic significance

The analysis of TSPAN9 expression in HCC tissues was conducted based on TCGA and GTEx databases. Results demonstrated a significant reduction in TSPAN9 mRNA expression in HCC tissues compared to normal liver tissues (P<0.05, Figure 3A). Survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter database revealed a higher survival probability in the TSPAN9 high-expression group compared to the TSPAN9 low-expression group (Figure 3B). Further examination of TSPAN9 expression in normal liver tissues and HCC tissues in the HPA database indicated markedly higher specific staining of TSPAN9 protein in normal tissues than in HCC tissues (Figure 3C). These findings further support that TSPAN9 is down-regulated in HCC tissues and impacts the prognosis of HCC patients.

Figure 3.

Expression and prognostic value of TSPAN9 in hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Analysis of TSPAN9 gene expression difference between HCC tissue and normal liver tissue. (B) The relationship between TSPAN9 expression and overall survival of HCC patients. (C) Expression of TSPAN9 protein in normal liver tissue (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000011105-TSPAN9/tissue/liver#img) and HCC tissue (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000011105-TSPAN9/cancer/liver+cancer#img) by immunohistochemical method in the HPA database (photographs downloaded when the scale bar at 200 µm). *, P<0.05. CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HPA, Human Protein Atlas; HR, hazard ratio; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; N, normal; NOS, not otherwise specified; T, tumor; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9.

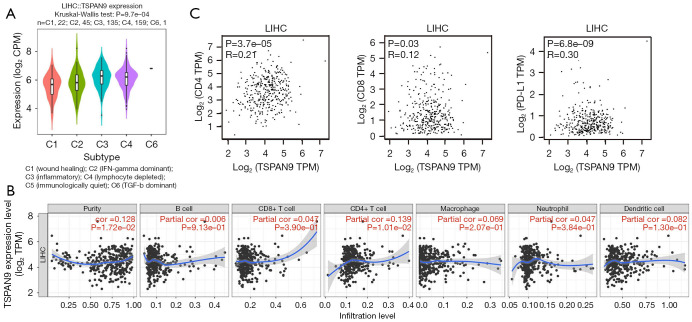

Correlation between TSPAN9 expression and HCC immunity

TSPAN9 expression in different immune subtypes of HCC was examined from TISIDB database, including six distinct immune subtypes: C1 (wound healing), C2 [interferon (IFN)-gamma dominant], C3 (inflammatory), C4 (lymphocyte depleted), C5 (immunologically quiet), and C6 [transforming growth factor (TGF)-b dominant]. Notably, TSPAN9 exhibits high expression in subtype C3 and low expression in subtype C1 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, an investigation into the correlation between TSPAN9 expression and six common immune cell types was conducted using the TIMER database. Figure 4B demonstrates a significant positive correlation between TSPAN9 expression and CD4+ T cells (P<0.05). Because the relationship between TSPAN9 expression and CD4+ T cells was the highest, we further detected the expression correlation between TSPAN9 with CD4, CD8, and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) using the GEPIA website. As shown in Figure 4C, the expression of TSPAN9 was positively correlated with PD-L1 (R=0.30, P<0.01). These results suggest that TSPAN9 may play a role in HCC immunity.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis of TSPAN9 expression with immune subtypes and immune cells. (A) Expression analysis of TSPAN9 in different immune subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. (B) The correlation between six common immune cells and TSPAN9 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. (C) GEPIA database was used to analyze the correlation between TSPAN9 expression and common immune checkpoints. CPM, counts per million; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; IFN, interferon; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; TGF, transforming growth factor; TPM, transcripts per million; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9.

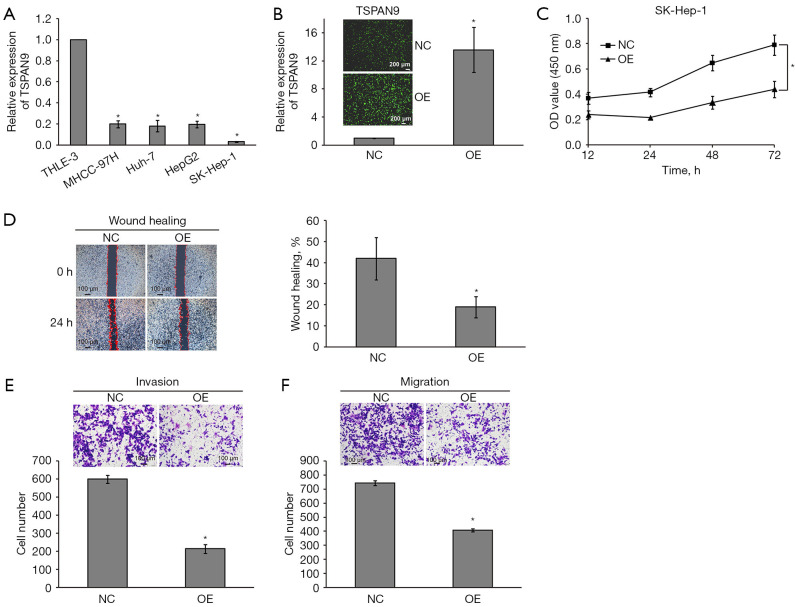

Biological functions of TSPAN9 in liver cancer cells

To investigate the roles of TSPAN9 in HCC progression, we overexpressed (OE) TSPAN9 in liver cancer cells. We firstly assessed TSPAN9 expression in several liver cancer cell lines. Figure 5A illustrates that TSPAN9 expression was lower in all four liver cancer cell lines compared to the normal liver THLE-3 cells, with the lowest expression observed in SK-Hep-1 cells. Subsequently, we conducted TSPAN9 overexpression in SK-Hep-1 cells and validated through qRT-PCR (Figure 5B). Following TSPAN9 overexpression, CCK-8 assay confirmed a significant decrease in cell proliferative activity in the TSPAN9 OE group compared to the negative control (NC) group (Figure 5C). The migration and invasion capacities of liver cancer cells were assessed by wound healing and Transwell assays. As shown in Figure 5D, SK-Hep-1-OE cells exhibited a slower scratch closure rate compared to SK-Hep-1-NC cells, indicating a significant decrease in cell migration ability after TSPAN9 overexpression (P<0.05). Consistent results were obtained in Transwell assays, SK-Hep-1-OE cells showed a notably reduced number of cells penetrating the chamber compared to SK-Hep-1-NC cells (Figure 5E,5F). These results imply that TSPAN9 can inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of liver cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Effects of upregulation of TSPAN9 on proliferation, invasion and migration of HCC cells. (A) qRT-PCR was used to detect the expression of TSPAN9 in human HCC cells. (B) The overexpression efficiency of TSPAN9 in HCC cells detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. (C) The effects of upregulation of TSPAN9 on the proliferation of HCC cells were detected by CCK-8. (D) Wound healing test showed that cell migration ability decreased after upregulation of TSPAN9. (E,F) Transwell assay showed that cell invasion and migration ability decreased after upregulation of TSPAN9 by crystal violet staining. *, P<0.05. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NC, negative control; OD, optical density; OE, overexpressed; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9.

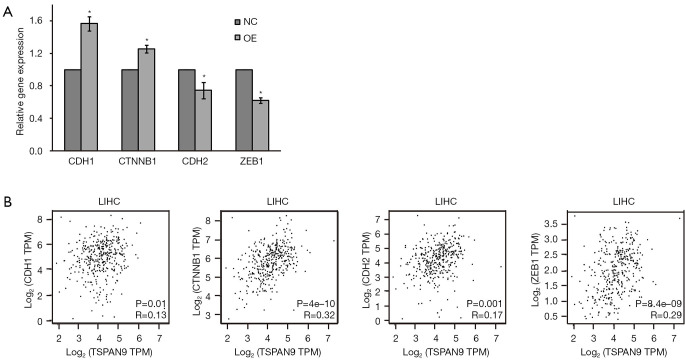

TSPAN9 expression was correlated with epithelium-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) factors in HCC

Due to the critical role of EMT in HCC progression (22), we performed correlation analysis between TSPAN9 and EMT factors. As shown in Figure 6A, we firstly detected the expression of EMT factors in liver cancer cells, and found that TSPAN9 overexpression increased the expression of epithelium factors (CDH1 and CTNNB1), while decreased the expression of mesenchymal factors (CDH2 and ZEB1). GEPIA database further revealed a significant association between TSPAN9 and the expression of EMT factors in HCC (all P<0.05, Figure 6B). These results suggest that TSPAN9 may play a role in HCC metastasis through EMT process.

Figure 6.

Correlation between TSPAN9 expression and EMT factors. (A) qRT-PCR was used to detect the expression of EMT factors after TSPAN9 overexpression in HCC cells. *, P<0.05 as compared with NC group. (B) Relationship between TSPAN9 expression and EMT factors in HCC tissues through GEPIA database. CDH1, E-cadherin; CDH2, N-cadherin; CTNNB1, catenin beta 1; EMT, epithelium-mesenchymal transformation; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; NC, negative control; OE, overexpressed; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; TPM, transcripts per million; TSPAN9, tetraspanin 9; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1.

Discussion

HCC is a highly malignant tumor with a relatively high potential for metastasis. HCC cells undergo significant behavioral changes during metastasis, such as uncontrolled proliferation and enhanced migration and invasion capabilities. The high invasiveness and metastatic rate of HCC pose significant challenges for its treatment and management (23). Surgery is a common treatment for HCC patients, but it is less effective for postoperative recurrence and inoperable patients (24). Most HCC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, leading to significantly reduced survival rates. In recent years, immunotherapy represented by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has promoted the systemic treatment of HCC (25). Developing targeted drugs for these biological processes is urgent to improve HCC treatment outcomes and patient survival rates.

Existing studies have shown that TSPAN9, as a member of the TSPAN superfamily, plays roles in various tumors, especially gastric cancer and osteosarcoma (26,27). A study indicates that increased TSPAN9 expression can inhibit gastric cancer cell migration in collaboration with proteins like EMILIN1, partially mediated through the ERK1/2 pathway (28). In osteosarcoma, TSPAN9 promotes cancer metastasis via pathways such as FAK-Ras-ERK1/2 (27), suggesting that TSPAN9 may act as a tumor suppressor in some contexts. In this study, we conducted pan-cancer analysis and found that TSPAN9 expression was deregulated in 17 types of tumors, which may be related with mutations, and sCNAs. Moreover, TSPAN9 was found downregulated in HCC tissues, and HCC patients with low expression of TSPAN9 had a poorer prognosis than that of high TSPAN9 expression group. Further biological functions of TSPAN9 in HCC were detected by overexpressing TSPAN9 in liver cancer cells. The cell results show that overexpression of TSPAN9 can significantly inhibit cell proliferation and metastasis, consistent with above previous studies. Combining bioinformatics analyses with the biological function experiments, we speculate that TSPAN9 may act as a tumor suppressor in HCC by reducing cell proliferation and metastasis.

In our previous study, the AL139383.1/hsa-miR-9-5p axis was identified as a potential pathway to regulate the expression of TSPAN9, and low TSPAN9 expression was associated with high levels of CTLA-4 in HCC (19). CTLA-4 helps tumors evade immune system attacks by inhibiting T cell activity, and anti-CTLA-4 can improve treatment and prognosis in HCC patients (29,30). This study also explored the relationship between TSPAN9 expression and HCC immunity. We elucidated that nine of the common 11 immune checkpoint genes were correlated with TSPAN9 expression in HCC, including CTLA-4 and PD-L1. Furthermore, TSPAN9 expression showed significant relationship with immune cells, especially CD4+ T cells. These results further support TSPAN9 as a potential immune biomarker for HCC treatment.

However, there are some limitations in this study, as it primarily focuses on cell proliferation and metastasis to explore TSPAN9’s functional roles in HCC. Further research is needed to understand how TSPAN9 regulates malignant behavior in HCC and its interactions with cellular pathways through TSPAN9 knockdown methodology in vivo and in vitro.

Conclusions

Bioinformatics analyses indicate that TSPAN9 is downregulated in HCC tissues and low expression of TSPAN9 is a risk factor for HCC prognosis. Biological functions suggest that TSPAN9 can inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells. Our study supports that TSPAN9 has the potential to become a novel biomarker for HCC progression and prognosis.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-2025-174/rc

Funding: This work was supported by the Key Science and Technology Research and Development Program Project of Guangxi (No. AB22035017), and College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (No. 202210601040).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-2025-174/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-2025-174/dss

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. 10.3322/caac.21834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Z, Li Q, Yu J, et al. Analysis of the epidemiological characteristics and disease burden of malignant tumors in Guangxi, 2019. Chinese Journal of Oncology Prevention and Treatment 2024;16:66-75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang SY, Danpanichkul P, Agopian V, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: updates on epidemiology, surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Mol Hepatol 2025;31:S228-54. 10.3350/cmh.2024.0824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solhi R, Pourhamzeh M, Zarrabi A, et al. Novel biomarkers for monitoring and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int 2024;24:428 . 10.1186/s12935-024-03600-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Marco L, Romanzi A, Pivetti A, et al. Suppressing, stimulating and/or inhibiting: The evolving management of HCC patient after liver transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2025;207:104607 . 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kanwal F, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance - utilization, barriers and the impact of changing aetiology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;20:797-809. 10.1038/s41575-023-00818-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castaneda M, den Hollander P, Kuburich NA, et al. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol 2022;87:17-31. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesh K, Massagué J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat Med 2021;27:34-44. 10.1038/s41591-020-01195-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Q, Sun H, Mei L, et al. Ribosomal proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma: mysterious but promising. Cell Biosci 2024;14:133 . 10.1186/s13578-024-01316-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal H, Parwani S, Kaur J. Deciphering the nexus between long non-coding RNAs and endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatocellular carcinoma: biomarker discovery and therapeutic horizons. Cell Death Discov 2024;10:451 . 10.1038/s41420-024-02200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mrozowska M, Górnicki T, Olbromski M, et al. New insights into the role of tetraspanin 6, 7, and 8 in physiology and pathology. Cancer Med 2024;13:e7390 . 10.1002/cam4.7390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:801-11. 10.1038/nrm1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X, Zhang J, Huang Y. Tetraspanins in cell migration. Cell Adh Migr 2015;9:406-15. 10.1080/19336918.2015.1005465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Du FH, Wang RX, et al. TSPAN6 reinforces the malignant progression of glioblastoma via interacting with CDK5RAP3 and regulating STAT3 signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci 2024;20:2440-53. 10.7150/ijbs.85984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang H, Huang Z, Wang M, et al. Research progress of migrasomes: from genesis to formation, physiology to pathology. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024;12:1420413 . 10.3389/fcell.2024.1420413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dharan R, Sorkin R. Tetraspanin proteins in membrane remodeling processes. J Cell Sci 2024;137:jcs261532 . 10.1242/jcs.261532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Song Q, Shang K, et al. Tspan protein family: focusing on the occurrence, progression, and treatment of cancer. Cell Death Discov 2024;10:187 . 10.1038/s41420-024-01961-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dash S, Wu CC, Wu CC, et al. Extracellular Vesicle Membrane Protein Profiling and Targeted Mass Spectrometry Unveil CD59 and Tetraspanin 9 as Novel Plasma Biomarkers for Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;15:177 . 10.3390/cancers15010177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan S, Song X, Zhang C, et al. hsa-miR-9-5p-Mediated TSPAN9 Downregulation Is Positively Related to Both Poor Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prognosis and the Tumor Immune Infiltration. J Immunol Res 2022;2022:9051229 . 10.1155/2022/9051229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu HM, Huang YY, Xu YQ, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit B56ε in pan-cancer and its role and mechanism in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024;16:475-92. 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i2.475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang T, Zhang R, Zhang Z, et al. REXO2 up-regulation is positively correlated with poor prognosis and tumor immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol 2024;130:111740 . 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, He Y, Wang J, et al. Re-exploration of immunotherapy targeting EMT of hepatocellular carcinoma: Starting from the NF-κB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2024;174:116566 . 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Li H, Zhuo J, et al. Impact of immunosuppressants on tumor pulmonary metastasis: new insight into transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Med 2024;21:1033-49. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2024.0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Choi HW, Kim JS, et al. Update on Resection Strategies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Narrative Review. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:4093 . 10.3390/cancers16234093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krupa K, Fudalej M, Cencelewicz-Lesikow A, et al. Current Treatment Methods in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:4059 . 10.3390/cancers16234059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng Y, Cai S, Shen J, et al. Tetraspanins: Novel Molecular Regulators of Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol 2021;11:702510 . 10.3389/fonc.2021.702510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shao S, Piao L, Wang J, et al. Tspan9 Induces EMT and Promotes Osteosarcoma Metastasis via Activating FAK-Ras-ERK1/2 Pathway. Front Oncol 2022;12:774988 . 10.3389/fonc.2022.774988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi Y, Lv J, Liu S, et al. TSPAN9 and EMILIN1 synergistically inhibit the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells by increasing TSPAN9 expression. BMC Cancer 2019;19:630 . 10.1186/s12885-019-5810-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavelescu LA, Enache RM, Roşu OA, et al. Predictive Biomarkers and Resistance Mechanisms of Checkpoint Inhibitors in Malignant Solid Tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:9659 . 10.3390/ijms25179659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hao L, Li S, Ye F, et al. The current status and future of targeted-immune combination for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol 2024;15:1418965 . 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1418965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]