Summary

Conventional treatments for advanced endometriosis often have limited efficacy due to chemotherapy resistance, recurrence, and metastasis. This study analyzed clinical specimens to investigate the role of NXF1 in endometrial cancer (ECa) progression. Mouse models and molecular biology assays were used to elucidate NXF1’s function and mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. Results showed NXF1 expression was negatively correlated with histological grade and poor patient prognosis. NXF1 inhibited ECa cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion in vitro, and suppressed tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. Mechanistically, NXF1 interferes with the binding of SRSF3 to exon 3 of SP4, preventing the formation of the “cancerous” long SP4 isoform (L-SP4) and promoting the “noncancerous” short SP4 isoform (S-SP4), which lacks the transactivation domain. In conclusion, NXF1 suppresses ECa tumorigenicity and progression through an SRSF3-mediated SP4 alternative splicing mechanism, and could serve as a novel prognostic biomarker for clinical intervention in ECa.

Subject areas: Cancer, Cell biology, Molecular biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

NXF1 inhibits the malignant progression of endometrial cancer

-

•

NXF1 interferes with the binding of SRSF3 to exon 3 of SP4

-

•

NXF1 prevents the formation of the “cancerous” L-SP4 and promotes the “noncancerous” S-SP4

Cancer; Cell biology; Molecular biology.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (ECa) is a clinically heterogeneous disease and has become the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries, as well as the second most common worldwide, largely due to higher rates of cervical cancer in the developing world.1 The incidence of ECa is steadily increasing, primarily driven by population aging and rising obesity rates.2,3 Although the disease often presents with symptoms at an early stage and is frequently diagnosed at stage I,4 awareness among the general population remains low. Unfortunately, if diagnosis is delayed, the prognosis is often poor. The 5-year survival rates for ECa at stages I and II (according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] classification) are approximately 92% and 75%, respectively.5,6 For women diagnosed with advanced ECa (FIGO stages III and IV), the 5-year survival rates range from 57 to 66% and 20–26%, respectively.6 ECa is broadly classified into two subtypes based on histological, clinical, and metabolic features.7 Type 1 carcinoma is the most common subtype, characterized by low-grade, endometrioid, diploid, hormone-receptor-positive tumors. It is typically amenable to surgical treatment and is associated with a good prognosis.8,9 Type 2 ECas are typically estrogen-independent and include the clinically aggressive “serous” and “clear cell” subtypes, which are associated with a higher risk of metastasis and poor prognosis.4,7 While it may seem intuitive to classify ECas into these two types, this classification is far from perfect, as there is significant overlap between type 1 and type 2 tumors.10 It is becoming increasingly clear that ECa encompasses a spectrum of diseases with distinct genetic and molecular characteristics. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop “pre-cancerous” testing methods and effective patient risk stratification strategies for early diagnosis and prevention of ECa.

Alternative splicing is a crucial mechanism of gene regulation that contributes to proteomic diversity. It involves the generation of multiple functionally distinct transcripts from a single gene through the selective removal or retention of exons and/or introns during RNA maturation.11,12 Alternative splicing can occur through various mechanisms, including exon skipping, intron retention, selection of alternative donor and acceptor splice sites, and mutually exclusive splicing.13,14 These variations can influence mRNA stability, localization, and translation. Recent estimates suggest that about 95% of human multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing.15,16 There is substantial evidence that selective splicing plays a key role in producing different protein isoforms that are involved in critical cellular processes, such as cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.11

The serine and arginine-rich (SR) protein family consists of 12 members, each characterized by one or two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and a serine/arginine-rich domain. SR proteins function by interacting with short sequence motifs near splice sites, which act as exonic/intronic splicing enhancers (ESEs/ISEs) or exonic/intronic splicing silencers (ESSs/ISSs). Through these interactions, SR proteins can either stimulate or repress spliceosome assembly.17,18 In most cases, SR family proteins bind to ESE motifs and enhance splicing by recruiting spliceosomes.19 Abnormal expression, activation, or somatic mutations of SR proteins are implicated in the development of various cancers.20 However, the mechanisms underlying the complex roles of SR proteins in splicing remain not fully understood. After extensive processing, mRNA is primarily exported from the nucleus by the nuclear RNA export factor 1 (NXF1/Tap) and its binding partner Nxt1/p15, through nuclear pore complexes.21,22,23 So far, there have been few studies reporting the role of NXF1 in the progression of ECa.

In this study, we investigated the role of NXF1 in regulating SRSF3-mediated splicing events in downstream genes in ECa. NXF1 significantly inhibits the splicing activity of SRSF3 on the downstream gene SP4, thereby influencing tumor progression. We aimed to verify the molecular mechanisms underlying this process through both in vitro and in vivo experiments and explore potential new therapeutic targets or tumor markers that could be identified.

Results

NXF1 low-expression in endometrial cancer is associated with clinicopathological features and prognosis

We found that in the TCGA database, the prognosis of patients was significantly positively correlated with the level of NXF1 gene expression. Lower patient death was observed in ECa patients with high NXF1 levels compared with the patients classified as low NXF1 levels (Figure 1A). Kaplan-Meier survival analyses revealed that patients with NXF1 low-expression were at a higher risk of ECa death than patients with low NXF1 expression (Figure 1B). In contrast, ECa patients with high NXF1 levels had a lower incidence of recurrence (Figure 1C), and their disease-free survival was significantly longer than those with low NXF1 levels (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

NXF1 expression is significantly down-regulated in ECa and associated with favorable prognosis

(A–D) Compared with the ECa patients with a high level of NXF1 expression (the higher 30%), the patients with low NXF1 mRNA expression had higher death rates and relapse rates, shorter DFS and OS from the TCGA ECa specimen cohorts.

(E and F) NXF1 mRNA (E) and NXF1 protein (F) expression levels were detected in normal endometrial tissues and paired ECa tissues (n = 6).

(G) IHC staining of NXF1 in different tumor stages, Scale bars, 100 μm. Data are presented as the means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To investigate the role of NXF1 in ECa, we analyzed NXF1 mRNA and protein levels in fresh-frozen ECa tissue samples (T) and normal endometrial tissue samples (N). NXF1 mRNA and protein levels were frequently down-regulated in ECa tissues compared with normal endometrial tissues (Figures 1E and 1F). An extensive tissue microarray analysis of 70 ECa tissue samples was performed using an IHC assay, lower levels of NXF1 expression were significantly observed in stage II and III ECa s compared with stage I cancers (Figure 1G).

NXF1 inhibited the malignant phenotype of endometrial carcinoma in vitro and in vivo

To identify the influences of the NXF1 on cancer progression, a construct was generated in which the FLAG tag (six amino acids) was fused to the full-length NXF1 transcript. The Flag-NXF1 lentiviral plasmids was stably expressed in KLE cells, Flag and NXF1 immuno-staining using anti-Flag antibody and anti-NXF1 antibody were detected (Figures 2A and 2B). To indicated the construct was over-expressed in KLE cells and ISH cells, Flag-NXF1 mRNA levels, and the fusion protein levels were determined by qPCR and western blotting (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Stable overexpression of NXF1 suppressed the malignant phenotypes of the ECa cells in vitro and in vivo

(A and B) The Flag-NXF1 lentiviral plasmids was stably expressed in KLE cells. Flag and NXF1 were immunostained using anti-Flag and anti-NXF1 antibodies, respectively.

(C and D) Stable overexpression of NXF1 was measured in KLE and ISH cells by qRT-PCR and western blot.

(E–G) The effects of the stable overexpression of NXF1 on KLE and ISH cell growth (E), colony formation (F), migration, and invasion (G) were determined, Scale bars, 200 μm. (H) Tumor volume and weight at the endpoints of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by the KLE cells stably transfected with LV-NC or LV-NXF1 into nude mice (n = 6 per group).

(I) NOD-SCID mice were treated with via tail vein injection of KLE cells (1 x 106 cells/mouse) stably transfected with LV-NC-Luc or LV-NXF1-Luc. Pulmonary metastasis was detected by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) (n = 5 per group).

(J) Representative images of the extent of metastasis based on H&E staining, Scale bars, 200 μm. Data are presented as the means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

The NXF1-Flag construct was over-expressed in KLE cells and ISH cells, we found that over-expression of NXF1 inhibit cell growth (Figure 2E), cell proliferation (Figure 2F), colony formation (Figure 2G). In order to further verify the role of NXF1 in the progression of ECa, NXF1 expression was silenced in KLE cells and ISH cells. The NXF1 mRNA levels and protein levels were significantly decreased detected by qPCR and western blot (Figures S1A and S1B). In contrast to the overexpression of NXF1, we observe the opposite phenomenon. The silencing of NXF1 significantly increased ECa cell growth, migration and invasion, colony formation in vitro (Figures S1C–S1E).

NXF1 overexpressed cells and control cells were subcutaneously injected into the left and right sides of BALB/c nude mice. As shown in Figure 2H, the in vivo growth was clearly impaired in the NXF1 overexpressed cells compared with ECa cells stably expressing blank vector (NC). The tumors that injected with NC cells were much larger than those injected with NXF1 overexpressed cells. Moreover, the metastatic nodules that developed in mice after tail vein injections with luciferase-tagged NC cells were larger than the nodules in mice injected with cells stably expressing NXF1 (Figures 2I and 2J).

NXF1 is involved in intracellular alternative splicing events

In addition, we used RNA-seq to measure the overexpression of NXF1-mediated genomic changes. Interestingly, we found that after stable overexpression of NXF1, extremely significant variable alternative splicing events occurred in cells, and a large proportion of these alternative splicing events were found to be Exon skipping after analysis (Figures 3A and 3B). Compared with the NC group, there were 5772 differential splicing events (p value < 0.05)for NXF1 overexpression, including 498 alternative 3 splice site (A3SS), 478 alternative 5 splice site (A5SS), 624 mutually exclusive exon, 604 retained intron, and 3568 skipped exon events, indicating that NXF1 plays an important role in pre-mRNA splicing by interacting with splicing regulators. Among these alternative splicing events, the alternative splicing of SP4 gene has aroused our interest and concern (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

NXF1 interacted with SRSF3 to regulate SP4 pre-mRNA alternative splicing

(A) Quantification of NXF1-regulated AS events in each category was measured RNA sequencing. (A3SS/A5SS, alternative 3’/5′ splice sites, MXE, mutually exclusive exons, RI, retained introns, SE, skipped exons).

(B) Changes in PSI values of NXF1-regulated AS events were shown.

(C and D) NXF1 regulated SP4 pre-mRNA splicing and inhibited L-SP4 isoform formation. The Flag-NXF1 lentiviral plasmids was stably expressed in KLE cells, and the levels of L-SP4 and S-SP4 splicing variants were detected.

(E and F) Flag-NXF1 and HA-SRSF3 plasmid were transfected into KLE cells, cellular lysates were treated with 10 mg/mL RNase A (Thermofisher, EN0531) for 1h or no treatment, Flag-NXF1 complexes were co-immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody, then SRSF3 was detected (E), and HA-SRSF3 complexes were co-immunoprecipitated by anti-HA antibody, then NXF1 was detected (F).Data are presented as the means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

SP4 is a general Transcription factor (TF) that binds to and acts through GC base boxes, which are frequently occurring DNA elements present in many promoters and enhancers.24 Transcription factors (TFs) are the confluence points of many physiological processes in a cell. Alterations in the regulation of transcription factors lead to dysregulation of gene expression and contribute to the pathogenesis of most human diseases, including cancer.25 Many oncogenic signaling pathways alter the function of TFS, enabling alterations in gene expression that drive oncogenesis and cancer progression.26,27

These findings suggest that NXF1 may be involved in alternative splicing events in vivo. To verify the correctness of this analysis, we used PCR assay to observe the effect of SP4 pre-mRNA after overexpression of NXF1. Overexpression of NXF1 induces the formation of short SP4 (S-SP4) subtype and inhibits the formation of long SP4 (L-SP4) subtype (Figure 3D). The results are consistent with the data analysis, pre-mRNA of SP4 was spliced.

NXF1 interacts with splicing factor SRSF3

In order to further explore how NXF1 affects the splicing of SP4, we consulted databases and a large number of literature. We found that SRSF3 played a key role in the splicing of SP4 in several papers.28,29 SRSF3 is a member of the SR family of proteins and plays a major role in splicing events of SP4, NXF1 is a key factor of nuclear export protein. To investigate whether the splicing change of SP4 caused by overexpression of NXF1 is related to SRSF3, we constructed a full-length SRSF3 gene expression plasmid labeled with HA.

Through co-IP experiment, we further confirmed that NXF1 can interact with SRSF3 (Figures 3E and 3F). Considering that SRSF3 is an RNA splicing factor and RNA-binding protein, we further investigated whether SRSF3 could still interact with NXF1 in the case of RNase treatment, and the results showed that the interaction between NXF1 and SRSF3 was independent of RNA.

To determine which regions or residues of SRSF3 interact with NXF1, a series of SRSF3-HA mutants were constructed based on the recognized SRSF3 domain, includes an RRM domain and an RS domain (Figure 4A). These mutants and NXF1-Flag co-expressed in HEK293T cells. We demonstrated that all of the mutants can interact with NXF1 (Figures 4B and 4C). we speculate that NXF1 binds to the linked sequence between the two domains of SRSF3, but not to both domains. Next, we predicted that the amino acid 221 (Aspartic acid) of NXF1 played a key role in spatial conformation based on the protein quaternary structure model, when combined with Amino acids at positions 86 and 90 of SRSF3 (Figure 4D). A study showed that the amino acids at positions 86, 88, and 90 of the mutated SRSF3 abolished the binding of SRSF3 to NXF1.30 Therefore, we constructed a mutant of SRSF3 (RRRmut: R86A, R88A and R90A). When we mutate the key amino acid sites 86, 88, and 90 of SRSF3, NXF1 no longer binds to SRSF3 (Figures 4E and 4F). Moreover, we mutated the 221 Aspartic acids (D) to alanine (A), and further Co-IP experiments confirmed that Aspartic acid at the 221st position of NXF1 protein played A key role in the resulting process with SRSF3. When the Aspartic acid was mutated into alanine, the binding ability of NXF1 and SRSF3 was significantly weakened (Figures 4G and 4H). To verify whether the binding site was effective in vivo, We stably knocked down the expression of NXF1 in ECa cells, then stably overexpressed wt-NXF1 or NXF1-D221A mutant, and finally conducted subcutaneous tumorigenesis experiments. The results indicate that compared with the control group overexpressing empty plasmids, overexpressed wt-NXF1 and NXF1-D221A mutant were able to inhibit ECa growth. However, compared with the NXF1-D221A mutant group, overexpressed wt-NXF1 has a more significant inhibitory effect. These results preliminarily indicate that the binding site was effective in vivo (Figure 4I).

Figure 4.

NXF1 interacted with the linkage sequence between two structural domains of RRM and RS in SRSF3

Wild-type (WT) SRSF3 and mutated plasmids expressing different functional domains.

(B and C) KLE cells were co-transfected with Flag-NXF1 plasmids and mutated SRSF3 plasmids with HA-tagged forms. Co-IP assays were performed with anti-Flag or anti-HA antibodies, followed by immunoblotting.

(D) Molecular docking analysis of NXF1 with SRSF3.

(E and F) Plasmids expressing WT Flag-NXF1 and mutated HA-SRSF3 (RRRmut: Arg 86 Ala, Arg 88 Ala, Arg 90 Ala) were transfected into KLE cells, and interactions between NXF1 and SRSF3 mutant were analyzed by western blotting after Co-IP assays.

(G and H) Plasmids expressing WT HA-SRSF3 and mutated Flag-NXF1 (Asp 221 Ala) were transfected into KLE cells, and interactions between SRSF3 and NXF1 mutant were analyzed by western blotting after Co-IP assays.

(I) KLE cells were stably knocked down the expression of NXF1 in ECa cells, then stably overexpressed wt-NXF1 or NXF1-D221A mutant, and finally conducted subcutaneous tumorigenesis experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

NXF1 inhibit endometrial cancer tumor progression through SRSF3

In order to further verify the role of SRSF3 in the progression of ECa, SRSF3 expression was silenced in ECa cells. The SRSF3 protein levels were significantly decreased detected by western blot (Figure S2A). The silencing of SRSF3 significantly increased ECa cell growth, migration and invasion in vitro (Figures S2B and S2C). To determine whether NXF1 affects the cancer progression of ECa cells through SRSF3, Flag-NXF1 and HA-SRSF3 were co-transfected into ECa cells (Figure 5A). Overexpression of SRSF3 completely reversed the inhibition of ECa cell growth, colony formation, migration, and invasion mediated by NXF1 overexpression (Figures 5B–5D), suggesting that NXF1 stimulates tumor progression in ECa primarily through SRSF3.

Figure 5.

NXF1 antagonized the SRSF3-induced aggressive phenotype of the ECa cells

Flag-NXF1, HA-SRSF3, or Flag-NXF1 plasmid together with the HA-SRSF3 plasmid were transfected in KLE and ISH cells, and the indicated protein expression (A), cell growth (B), colony formation (C), migration, and invasion (D) were determined, Scale bars, 200 μm. Data are presented as the means ± SD.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

NXF1 weakens the binding of SRSF3 to SP4 Exon 3 and the inclusion of SP4 Exon 3

To investigate whether inhibition of ECa progression by NXF1 via SRSF3 is related to the regulation of SP4 shearing events by SRSF3, we conducted further experiments. We used RNA-seq to measure the PCR products of SP4 following the overexpression of NXF1 in ECa cells. We found that NXF1 inhibits the inclusion of exon 3 of TF SP4 to promote short SP4 splicing variant formation (we termed S-SP4) and suppress long SP4 splicing variant formation without exon 3 (we termed L-SP4). The skipping of exon 3 of SP4 was confirmed by targeted RNA-seq when NXF1 expression was knocked out (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

NXF1 inhibited the binding of SRSF3 to exon 3 of SP4

(A) NXF1 inhibited the inclusion of SP4 exon 3 (E3) using RNA-seq analysis.

(B)The cellular nuclear extracts were affinity-purified using the indicated biotin-labeled RNAs, and SRSF3 and NXF1 in purified complexes were detected.

(C) KLE cells were transfected with the Flag-NXF1 vector, RNA affinity purification was performed using the indicated biotin-labeled RNAs, and SRSF3 was detected.

(D) Flag-NXF1 vector at the indicated doses was transfected into KLE cells, RNA affinity purification was performed using biotin-labeled RNA E3 (848–866), and SRSF3 was detected.

(E) KLE cells were cotransfected with the indicated SRSF3-HA mutants, RNA affinity purification was performed using biotin-labeled RNA E3 (848–866), and HA- SRSF3 was detected.

(F) KLE cells were cotransfected with the indicated SRSF3-HA mut1 together with the Flag-NXF1 vector, RNA affinity purification was performed using biotin-labeled RNA E3 (848–866), and HA- SRSF3 was detected.

(G) KLE cells were cotransfected with the indicated SRSF3-HA RRRmut together with the Flag-NXF1 vector, RNA affinity purification was performed using biotin-labeled RNA E3 (848–866), and HA- SRSF3 was detected.

(H) The NXF1 was transfected into KLE cells for 48 h, the CLIP assay was performed using an anti-SRSF3 antibody. Data are presented as the means ± SD.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Spanning the predicted SRSF3-binding motif in SP4 exon3 (SP4E3), 5-biotin-labeled RNA spanning the predicted SRSF3-binding motif in SP4 exon3 (SP4E3mut) was synthesized, and the C mutation on this sequence was turned into G (SP4E3mut), the first 20 bases of SP4 exon3 were synthesized as a negative control. We performed RNA affinity chromatography using these 5-biotinlabeled RNA probes and found that SRSF3 strongly bound to the SP4 E3 RNA probe but not the negative control RNA probe (Figure 6B). The mutation of SRSF3- bound sites completely abrogated the binding of SRSF3 to the SP4 E3 RNA probe. However, NXF1 itself did not directly bind to these SP4 exon 3 RNA probes, indicating that NXF1 does not directly recognize and bind to SP4 exon 3 (Figure 6B). Taken together, our data indicate that SRSF3 binds to SP4 exon 3 but NXF1 does not. Further studies showed that NXF1 overexpression significantly induced the binding of SRSF3 to SP4E3, but did not induce the binding of SRSF3 to SP4E3mut (Figure 6C). In addition, the binding of SRSF3 to SP4 exon 3 was weakened in a dose-dependent manner with NXF1 (Figure 6D). As expected, the RRM domain (mut1) of SRSF3 was able to bind to SP4E3, while the RS domain (mut2) was not (Figure 6E). NXF1 significantly weakened the binding of SRSF3 mut1 to SP4E3, indicating that the RRM domain of SRSF3 binding to SP4E3 is influenced by NXF1(Figure 6F). Next, we mutated the arginine-enriched sequence RRR in SRSF3, and NXF1 could not weaken the binding of SRSF3 of RRRmut to SP4E3, which proved that NXF1 regulated the shear events of SRSF3 to SP4 mainly by RRM motif (Figure 6G). To further investigate the inhibitory effect of NXF1 on SRSF3 binding to SP4 mRNA, we performed UV crosslink IP (CLIP) experiments. Our findings revealed that NXF1 significantly inhibited the binding of SRSF3 to exon 3 of SP4 (Figure 6H).

NXF1 inhibit SRSF3-Dependent inclusion of Exon 3 of SP4

Considering that NXF1 inhibiting the binding and recognition of SRSF3 to SP4 exon 3, we further investigated the effect of NXF1 on SP4 pre-mRNA splicing. Silencing of NXF1 enhances the inclusion of SP4 exon 3, thereby reducing the formation of S-SP4 and enhancing the formation of L-SP4 (Figure 7A). In addition, NXF1 did not change the total SP4 mRNA level (Figures S3A and S3B). Similar results were obtained in silenced SRSF3 cells (Figures 7B and S3C). Next, we studied the splicing of SP4 pre-mRNA in clinical tumor tissue samples. Compared with the adjacent non-tumor tissue, the level of S-SP4 mRNA in tumor tissue was significantly decreased, while the level of L-SP4 mRNA was significantly increased (Figure 7C). In clinical tissue samples, L-SP4 was negatively correlated with NXF1, while S-SP4 was positively correlated with NXF1 level (Figure 7D). There was no change in the total SP4 mRNA level in clinical tissue samples (Figure S3D). The overexpression of SRSF3 weakens the reduction in the inclusion of SP4 exon 3 caused by the overexpression of NXF1 (Figure 7E). In addition, NXF1 and SRSF3 did not change the total SP4 mRNA level (Figure S3E). Thus, we concluded that NXF1 inhibited the formation of L-SP4 and promoted the formation of S-SP4 by inhibiting the SRSF3-dependent exon 3 inclusion of SP4.

Figure 7.

NXF1 inhibits the inclusion of exon 3 of SP4

(A) KLE cells were transfected with two anti-NXF1 siRNAs, and levels of L-SP4 and S-SP4 splicing variants were detected.

(B) KLE cells were transfected with two anti-SRSF3 siRNAs, and levels of L-SP4 and S-SP4 splicing variants were detected.

(C) Levels of L-SP4 and S-SP4 splicing variants were detected between normal endometrial tissues and paired ECa tissues.

(D)The relationships of NXF1 mRNA levels with L-SP4 (upper panel) and S-SP4 (low panel) mRNA levels were analyzed in clinical tissue samples.

(E) Flag-NXF1, HA-SRSF3, or Flag-NXF1 plasmid together with the HA-SRSF3 plasmid were transfected in KLE cells, and levels of L-SP4 and S-SP4 splicing variants were detected. Data are presented as the means ± SD.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

NXF1 inhibit endometrial cancer malignant progression mainly through L-SP4

To determine the role of L-SP4 and S-SP4 in the progression of ECa, we restored the expression of L-SP4 or S-SP4, which is resistant to anti- SP4 siRNA, in SP4-knock down ECa cells (Figure S4A). In ECa cells KLE and ISH, silencing SP4 inhibit cell growth, colony formation, migration, and invasion (Figures S4B–S4D). This phenomenon can be reversed by the over-expression of L-SP4, but S-SP4 cannot reverse this phenomenon (Figures S4B–S4D). It was suggested that SP4 containing exon 3 could produce carcinogenic function, while S-SP4 did not. In order to the functional consequences of these isoforms on downstream gene expression, We have selected several important genes in the sequencing data of overexpression of NXF1 and performed qPCR after overexpression of L-SP4 and S-SP4 (Figures S4E and S4F).Compared with the control group, L-SP4 can significantly upregulate the expression of CXCR4, PTGS2, FOS, and BMP2, while S-P4 cannot (Figure S4F).

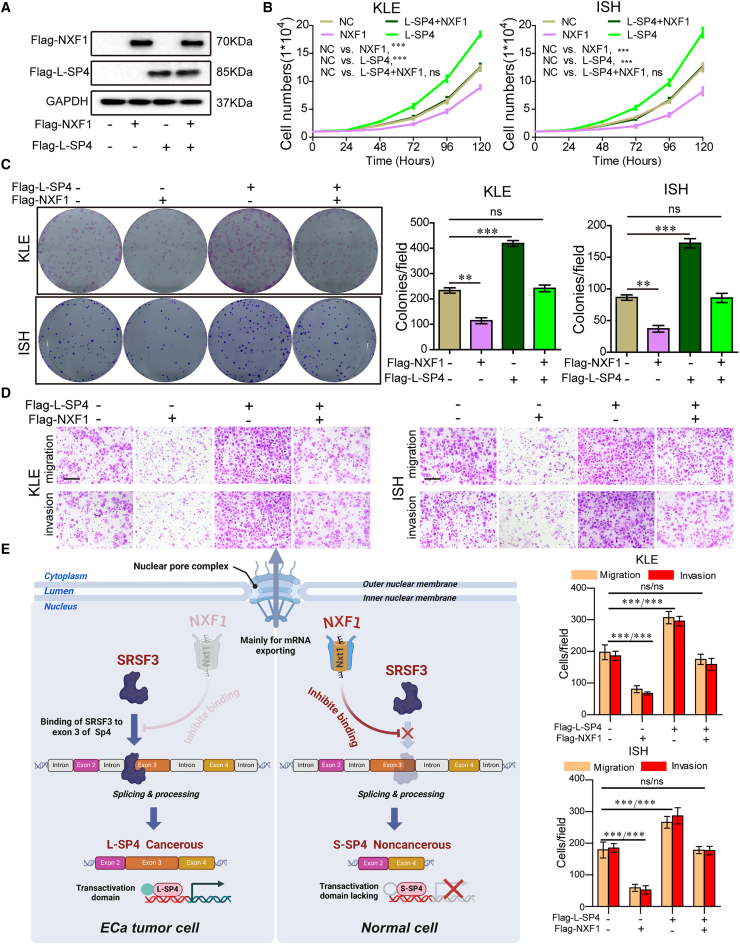

Next, we investigated whether NXF1 inhibited tumor progression primarily through L-SP4. Flag-NXF1 and Flag-L-SP4 were co-transfected (Figure 8A). Overexpression of L-SP4 completely increased cell growth, colony formation, migration and invasion induced by overexpression of NXF1 (Figures 8B–8D). Therefore, these results suggest that NXF1 mainly changes the splicing of SP4 through its interaction with SRSF3, thereby inhibiting malignant progression (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

NXF1 antagonized the L-SP4-induced aggressive phenotype of the ECa cells

(A–D) Flag-NXF1, Flag-L-SP4, or Flag-NXF1 plasmid together with the Flag-L-SP4 plasmid were transfected in KLE and ISH cells, and the indicated protein expression (A), cell growth (B), colony formation (C), migration, and invasion (D) were determined, Scale bars, 200 μm

(E) A regulatory model of NXF1 on malignant progression proposed in this study. Data are presented as the means ± SD.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

Alternative RNA splicing is a crucial mechanism of post-transcriptional gene regulation, with approximately 95% of human genes expressing multiple isoforms.31,32 This process contributes to the diversity and complexity of the human proteome, which plays a critical role in regulating organ and tissue development.12,31 However, recent studies have shown that splicing patterns in tumors are often altered and closely linked to tumor progression.19,32 Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests that cancer molecular subtypes are closely associated with splicing dysfunctions related to cell survival.33 These findings have sparked increasing interest in cancer therapies targeting splicing regulatory proteins or specific splicing events that drive key tumorigenic changes.

Currently, the widely accepted mechanism is that most RNA export depends on the Trex complex and NXF1, a key component of the canonical export pathway.34,35 Studies have shown that NXF1 is not only essential for RNA nuclear export but also plays a role in regulating RNA splicing. In mice, intronic intracisternal A particles (IAPs) can induce alternative splicing and other RNA processing events.36 However, NXF1 and certain alleles suppress IAP-induced alternative processing.36

In this study, we reveal that the interaction between NXF1 and the splicing factor SRSF3 prevents SRSF3 from binding to exon 3 of the transcription factor SP4, ultimately leading to exon 3 exclusion. This exclusion results in the upregulation of the long SP4 isoform (L-SP4 protein) and the downregulation of the short SP4 isoform (S-SP4 peptide). Katahira et al. found that NXF1 has a weak intrinsic affinity for RNA.35,37 Furthermore, Viphakone et al. could not identify any specific sequence that binds directly to NXF1 using cross-linking immunoprecipitation (CLIP).35,38 Consistent with these findings, our research shows that NXF1 does not bind to the RNA probe of exon 3 in SP4, indicating that NXF1 cannot directly recognize or bind to exon 3 of SP4.

In recent years, the identification of transcription factors driving solid tumor progression has significantly expanded.25 Protein-level alterations in these transcription factors can cause abnormal changes in downstream effectors, disrupting cellular homeostasis.39,40 For example, MYC is a key transcription factor frequently upregulated in various cancers.41,42 Similarly, the specificity protein (SP) family —comprising SP1, SP2, SP3, and SP4— is often overexpressed in several human cancers.43,44 In nine cancer cell lines derived from six different tumor types, SP4 knockdown significantly inhibited cell growth and migration while inducing apoptosis, suggesting that SP4 functions as an oncogene.45 Our findings reveal that SP4 pre-mRNA undergoes alternative splicing to produce two variants: L-SP4 and S-SP4. As a transcriptional regulator, L-SP4 promotes tumor progression in ECa, whereas S-SP4 lacks this cancer-promoting role. Understanding how L-SP4 drives the malignant progression of ECa through transcriptional regulation will be the focus of our future research.

In summary, we found that NXF1 inhibits ECa progression by blocking SRSF3-mediated splicing of SP4, promoting the formation of the “cancerous” L-SP4 isoform and inhibiting the production of the “non-cancerous” S-SP4 isoform. ECa patients with low NXF1 expression exhibit more aggressive clinicopathological features and have a worse prognosis. Our research contributes to a deeper understanding of the role of alternative splicing dysregulation in the progression of ECa, highlighting its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention.

Limitations of the study

Although we have investigated the role of NXF1 in the progression of ECa, there remains room for further research. ECa presents relatively typical clinical symptoms in its early stages, such as postmenopausal bleeding and intermenstrual bleeding, prompting patients to undergo corresponding examinations and treatments. As a result, advanced-stage ECa cases are relatively rare in clinical practice. This also led to a limited number of advanced cases collected in this study, and we will further gather relevant cases for analysis in subsequent research. In future studies, we plan to further explore the downstream roles of L-SP4 and S-SP4 in specific signaling pathways of ECa. Additionally, we intend to conduct in vivo targeting experiments, such as using exosome-packaged targeting sequences, to validate the effectiveness of the binding site between NXF1 and SRSF3. These efforts will further confirm the critical role of NXF1 in the progression of ECa.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Prof. Rui Duan (duanrui@sina.com).

Materials availability

Reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

-

•

The deposited data of this study are presented in key resources table. The data of the RNA-seq (SRA code PRJNA1130042) was deposited to the NIH SRA database. All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Hubei Natural Science Foundation (no. 2025AFB424), the Jingmen Central Hospital Doctoral Research Start-up Project Fund (N.M.), the Jingmen City Key Science and Technology Project (no. 2024YFZD052), and the Outstanding Young and Middle-aged Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Program of Colleges and Universities in Hubei Province (no. T201819).

Author contributions

N.M., R.D., and C.J.S. were responsible for conceiving the project and designing the experiments. X.Q.Y and N.M. wrote the manuscript. N.M., X.Q.Y, H.T., J.Z.W., S.B.Z., Z.B.X., J.Y., Q.Z., and C.G.H. conducted the in vitro and in vivo cell experiments; L.J.L. provided statistical support and analyzed the IHC data.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| NXF1 antibody | Proteintech | Cat No. 10328-1-AP; RRID:AB_2236500 |

| HRP-conjugated Affinipure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG | Proteintech | Cat No. SA00001-2; RRID:AB_2722564 |

| Anti-DDDDK tag antibody | Abcam | ab1162; RRID:AB_298215 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) | Abcam | ab150077; RRID:AB_298215 |

| SRSF3 Antibody | Abcam | ab198291; RRID:AB_3678796 |

| Anti-HA tag antibody | Abcam | ab9110; RRID:AB_307019 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) HRP | Proteintech | Cat No. SA00001-1; RRID:AB_2722565 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) HRP | Proteintech | Cat No. SA00001-2; RRID:AB_2722564 |

| GAPDH Antibody | Proteintech | Cat No. 10494-1-AP; RRID:AB_2263076 |

| Bacterial and virus | ||

| DH5-alpha competent E. coli | This paper | NA |

| NXF1-lentiviruses | This paper | NA |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Lipofectamine™ 2000 | Invitrogen™ | 11668019 |

| DAPI Staining Solution | Abcam | ab228549 |

| Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 13778030 |

| Co-IP lysis buffer | Beyotime | P0038 |

| protein A/G plus agarose beads | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | SC-2003 |

| 50× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | 524632 |

| Streptavidin-Agarose beads | Sigma-Aldrich | S1638 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ClonExpress MultiS One Step Cloning Kit | Vazyme | C113-01 |

| Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit | Beyotime | P0027 |

| PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit | Takara | RR037B |

| SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II kit | Takara | RR820A |

| Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 | Vazyme | C214 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNAseq data | NIH SRA public database | PRJNA1130042 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| KLE cells | ATCC | CRL-1622 |

| ISH cells | Procell | CL-0283 |

| HEK293T cells | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| Experimental models: Animal | ||

| BALB/c null mice | Medical Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong Province | NA |

| NOD-SCID mice | Medical Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong Province | NA |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software, LLC | V8 |

| IVIS 200 imaging system | IVIS 200 imaging Software | NA |

| Ensembl gene annotation v.90 | Ensembl gene annotation Software | V9 |

| rMATS program | rMATS program Software | NA |

| rmats2 sashimi-plot | https://github.com/Xinglab/rmats2sashimiplot | NA |

| Rosetta Version 3.5 | Rosetta Version Software | V3.5 |

| PyMOL5 | PyMOL5 Software | V5 |

| Oligonucleotides and Primers were seed in Table S1 | This paper | NA |

Expreimental model and participant details

Animal breeding and treatments

All experiments were carried out in accordance with The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jingmen Central Hospital affiliated to Jingchu University of Technology(Study approval number: 2024-03-007). For the in vivo tumor growth assay, 8 × 106 control or NXF1 stable expressing KLE cells were subcutaneously injected into the left and right flanks of each four week old BALB/c null female mice (n = 6). After 4 weeks, the tumors were stripped, photographed and weighed. For the in vivo metastasis assay, control or NXF1 stable expressing KLE cells were labeled using the Luciferase lentivirus system. 4 × 106 KLE-Luc-NC or KLE-Luc-NXF1 cells were injected into the tail veins of four week old NOD-SCID female mice (n = 5). After 4 weeks, the mice were monitored for lung metastases using the IVIS 200 imaging system.

Method details

Tissue samples, immuno-histochemistry and cell culture

Tissue microarray chip containing 70 ECa tissues was purchased from Alenabio (Xi’an, China). ECa tissues and paired adjacent normal tissues were collected from ECa patients at the Jingmen People’s Hospital. For immuno-histochemistry, after dewaxing, the chip was treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. After blocked using a standard labeled streptavidin biotin kit (DAKO, Germany), the chip was incubated with NXF1 antibody at 4 °C, overnight. The next day, the chip was stained using DAKO liquid 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride after incubated using goat anti-rabbit antibody for 2 h at room temperature. KLE cells (American type culture collection, ATCC) and ISH cells (ATCC) were cultured in Ham’s F12 nutrient medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. The HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Plasmid constructs, transfection, and stable overexpression

According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the constructs (NXF1-Flag and SRSF3-HA) were cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector using ClonExpress MultiS One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, C113-01). NXF1 and SRSF3 mutation vectors were constructed using Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme, C214). Plasmid construction primers are listed in the Table S1. Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) was used to transfect plasmid constructs into ECa cells. The siRNAs were transfected into ECa cells using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). psPAX2, pMD2.G and pCDH-NXF1 plasmids were transfected together into HEK293T cells to produce NXF1-lentiviruses. KLE and ISH cells were transfected using an overexpression NXF1 or empty lentivirus. After 48 h, transfected cells were screened using 2 μg/mL polybrene.

Immunofluorescence staining

After seeded on the glass cover slips for 24 h, treated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After permeablized by 0.1% Titon X-100 for 10 min, the cells were blocked by 3% BSA for 2 h. And then these cells were incubated with anti-Flag (1:1000) or Anti-NXF1 antibody (1:1000) overnight. Next, these cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary IgG antibodies for 2 h and the nucleus was stained by DAPI for 10 min. Finally, the immunofluorescence images were recorded by a confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Western blotting

Cells samples or Tissue samples were lysed using SDS lysis buffer (beyotime). Then, protein extract samples were separated by 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE and then electroblotted onto a PVDF blot. The blots were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, respectively. After washing three times with 0.1%PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20), the blots were incubated with corresponding secondary antibody at room temperature for 2h. After washing three times with 0.1%PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20), the blots were detected using Supersignal West Pico (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primary antibodies used were listed in the Table S1.

Cell growth and colony formation assays

For the cell growth assay, 1 × 104 treated ECa cells were seeded in 24-well plates, and counted at 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h. For the colony formation assays, treated ECa cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured in F12 medium containing 10% FBS for 9 days. After fixed in methanol for 20 min, the cells were stained with crystal violet solution.

Migration and invasion assays

Cell migration (without Matrigel) and invasion (coated with Matrigel) were examined using Transwell chambers with 8 μm inserts. A total of 8 × 104 KLE or ISH cells inserts and cultured at 37 °C in the top chambers without serum for 12 h and 16 h, respectively. The chambers were stained with 0.05% crystal violet (Sigma) and counted under phase-contrast microscopy.

RNA-seq and analysis

The control and NXF1-overexpressing groups were carried out in KLE cell line. Treated KLE cell RNA were extracted using Trizol. RNA-seq was performed by Novogene using an Illumina Novaseq6000. The 6 GB clean data per sample were collected for RNA-seq. Hg38 assembly was used for the read alignment. The Ensembl gene annotation v.90 was used to obtain gene annotation. Alternative splicing events were analyzed using the rMATS program on hisat2 output bam file. The rmats2 sashimi-plot (https://github.com/Xinglab/rmats2sashimiplot) was used to analyze the alternative splicing events. The raw transcriptome sequencing data of all the samples involved in this study have been uploaded to the SRA public database with accession number PRJNA1130042.

Rosetta docking

As previously described,46 the Rosetta docking was performed. The protein-protein docking was performed using the Rosetta Version 3.5. According to the docking prepack protocol, the structures from PDB of the docking partners were prepacked. PyMOL5 was used to illustrate the structures.

CO-IP

Treated ECa cells were lysed in Co-IP lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Co-IP was performed using anti-FLAG/anti-HA antibodies and protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz) to extract the complexes. The complexes were separated and were detected by western blotting.

RNA affinity purification

The 5′biotin-labeled SP4 EI3 RNAs were synthesized by Genscript company (Nanjing, China). Treated cells grown at 80% confluency were lysed in IP lysis buffer (beyotime) adding 50× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich & Roche). Nuclear pellets were extracted using Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (beyotime). In addition, 1 nmol biotin-labeled SP4 EI3 RNAs was bound with 40 μL Streptavidin-Agarose beads (Sigma) to produce RNA-immobilized beads. Then, Nuclear lysates were incubated with the RNA-immobilized beads at 4°C for 1 h while rotating. After protein and RNA binding, proteins were eluded with using SDS lysis buffer (Beyotime). The samples were separated and detected by Western blotting.

UV-crosslinking IP

The UV-crosslinking IP was carried out according to established protocols.47 Following UV exposure on ice at 100 mJ/cm2, the treated cells were broken down using a lysis buffer. Following a quick ultrasound treatment on ice, DNase was added to the cell lysate for a 10-min incubation. After diluting the supernatant to 1 mL with lysis buffer, 1 mg of the supernatant was incubated with anti-SRSF3 or immunoglobulin G (IgG) for IP in the presence of protein A/G plus agarose beads (SC-2003; Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Following three comprehensive washes, 10% of the samples served as IP controls, and the other 90% were treated with proteinase K at 65 °C for 30 min. Using the TRIzol method, RNA was extracted from the samples, reverse transcribed, and quantified by qPCR.

qRT-PCR, RT-PCR and SP4 splicing assays

The total RNA of tissue and cell samples was prepared using the TRIzol buffer (Invitrogen). The PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit was used to synthesize cDNA. The SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit was used to perform quantitative real-time PCR. In addition, the two SP4 splicing variants was detected using RT-PCR. The primers qRT-PCR and RT-PCR were provided in the Table S1.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data was reported as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t test between the two groups was used to analyze the data. The Kaplan-Meier curve with log rank test was used for survival analysis. Graphical Pad Prism 8.0 software was used for statistical analysis.(∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ns = no statistical significance).

Published: July 22, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113113.

Contributor Information

Nan Meng, Email: mengnanjm@126.com.

Chunjie Su, Email: 19986580855@163.com.

Rui Duan, Email: duanrui@sina.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M., Parkin D.M., Forman D., Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wise M.R., Jordan V., Lagas A., Showell M., Wong N., Lensen S., Farquhar C.M. Obesity and endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in premenopausal women: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;214:689.e1–689.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanderson P.A., Critchley H.O.D., Williams A.R.W., Arends M.J., Saunders P.T.K. New concepts for an old problem: the diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2017;23:232–254. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amant F., Moerman P., Neven P., Timmerman D., Van Limbergen E., Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creasman W.T., Odicino F., Maisonneuve P., Quinn M.A., Beller U., Benedet J.L., Heintz A.P.M., Ngan H.Y.S., Pecorelli S. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2006;95:S105–S143. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murali R., Soslow R.A., Weigelt B. Classification of endometrial carcinoma: more than two types. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e268–e278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokhman J.V. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 1983;15:10–17. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marx A., Chan J.K.C., Coindre J.M., Detterbeck F., Girard N., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Kurrer M.O., Marom E.M., Moreira A.L., et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Thymus: Continuity and Changes. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015;10:1383–1395. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer S.M., Powell M.E., Mileshkin L., Katsaros D., Bessette P., Haie-Meder C., Ottevanger P.B., Ledermann J.A., Khaw P., Colombo A., et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): final results of an international, open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:295–309. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30079-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAlpine J., Leon-Castillo A., Bosse T. The rise of a novel classification system for endometrial carcinoma; integration of molecular subclasses. J. Pathol. 2018;244:538–549. doi: 10.1002/path.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen M., Manley J.L. Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:741–754. doi: 10.1038/nrm2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baralle F.E., Giudice J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:437–451. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keren H., Lev-Maor G., Ast G. Alternative splicing and evolution: diversification, exon definition and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:345–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsen T.W., Graveley B.R. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature. 2010;463:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature08909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black D.L. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahl M.C., Will Cl Fau - Lührmann R., Lührmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Z., Fu X.D. Regulation of splicing by SR proteins and SR protein-specific kinases. Chromosoma. 2013;122:191–207. doi: 10.1007/s00412-013-0407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krecic A.M., Swanson M.S. hnRNP complexes: composition, structure, and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:363–371. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X., Wan X., Huang T., Zeng C., Sastry N., Wu B., James C.D., Horbinski C., Nakano I., Zhang W., et al. SRSF3-Regulated RNA Alternative Splicing Promotes Glioblastoma Tumorigenicity by Affecting Multiple Cellular Processes. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5288–5301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbanski L.M., Leclair N., Anczuków O. Alternative-splicing defects in cancer: Splicing regulators and their downstream targets, guiding the way to novel cancer therapeutics. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2018;9 doi: 10.1002/wrna.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen B.R. Nuclear RNA export pathways. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:4181–4187. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4181-4187.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler A., Hurt E. Exporting RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:761–773. doi: 10.1038/nrm2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ElMaghraby M.F., Andersen P.R., Pühringer F., Hohmann U., Meixner K., Lendl T., Tirian L., Brennecke J. A Heterochromatin-Specific RNA Export Pathway Facilitates piRNA Production. Cell. 2019;178:964–979.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safe S., Abbruzzese J., Abdelrahim M., Hedrick E. Specificity Protein Transcription Factors and Cancer: Opportunities for Drug Development. Cancer Prev. Res. 2018;11:371–382. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushweller J.H. Targeting transcription factors in cancer - from undruggable to reality. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:611–624. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee T.I., Young R.A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell. 2013;152:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papavassiliou K.A., Papavassiliou A.G. Transcription Factor Drug Targets. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016;117:2693–2696. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao W., Adhikari S., Dahal U., Chen Y.S., Hao Y.J., Sun B.F., Sun H.Y., Li A., Ping X.L., Lai W.Y., et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell. 2016;61:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng N., Chen M., Chen D., Chen X.H., Wang J.Z., Zhu S., He Y.T., Zhang X.L., Lu R.X., Yan G.R. Small Protein Hidden in lncRNA LOC90024 Promotes “Cancerous” RNA Splicing and Tumorigenesis. Adv. Sci. 2020;7 doi: 10.1002/advs.201903233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hargous Y., Hautbergue G.M., Tintaru A.M., Skrisovska L., Golovanov A.P., Stevenin J., Lian L.Y., Wilson S.A., Allain F.H.T. Molecular basis of RNA recognition and TAP binding by the SR proteins SRp20 and 9G8. EMBO J. 2006;25:5126–5137. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim M.S., Pinto S.M., Getnet D., Nirujogi R.S., Manda S.S., Chaerkady R., Madugundu A.K., Kelkar D.S., Isserlin R., Jain S., et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature. 2014;509:575–581. doi: 10.1038/nature13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu X., Harvey S.E., Zheng R., Lyu J., Grzeskowiak C.L., Powell E., Piwnica-Worms H., Scott K.L., Cheng C. The RNA-binding protein AKAP8 suppresses tumor metastasis by antagonizing EMT-associated alternative splicing. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:486. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S.C.W., Abdel-Wahab O. Therapeutic targeting of splicing in cancer. Nat. Med. 2016;22:976–986. doi: 10.1038/nm.4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carmody S.R., Wente S.R. mRNA nuclear export at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1933–1937. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuckerman B., Ron M., Mikl M., Segal E., Ulitsky I. Gene Architecture and Sequence Composition Underpin Selective Dependency of Nuclear Export of Long RNAs on NXF1 and the TREX Complex. Mol. Cell. 2020;79:251–267.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Concepcion D., Ross K.D., Hutt K.R., Yeo G.W., Hamilton B.A. Nxf1 natural variant E610G is a semi-dominant suppressor of IAP-induced RNA processing defects. PLoS Genet. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katahira J., Strässer K., Podtelejnikov A., Mann M., Jung J.U., Hurt E. The Mex67p-mediated nuclear mRNA export pathway is conserved from yeast to human. EMBO J. 1999;18:2593–2609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viphakone N., Sudbery I., Griffith L., Heath C.G., Sims D., Wilson S.A. Co-transcriptional Loading of RNA Export Factors Shapes the Human Transcriptome. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:310–323.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajagopal C., Lankadasari M.B., Aranjani J.M., Harikumar K.B. Targeting oncogenic transcription factors by polyphenols: A novel approach for cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;130:273–291. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brivanlou A.H., Darnell J.E., Jr. Signal transduction and the control of gene expression. Science. 2002;295:813–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1066355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang C.V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rickman D.S., Schulte J.H., Eilers M. The Expanding World of N-MYC-Driven Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:150–163. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safe S., Abdelrahim M. Sp transcription factor family and its role in cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:2438–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vizcaíno C., Mansilla S., Portugal J. Sp1 transcription factor: A long-standing target in cancer chemotherapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;152:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim C.K., He P., Bialkowska A.B., Yang V.W. SP and KLF Transcription Factors in Digestive Physiology and Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1845–1875. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding Y.H., Fan S.B., Li S., Feng B.Y., Gao N., Ye K., He S.M., Dong M.Q. Increasing the Depth of Mass-Spectrometry-Based Structural Analysis of Protein Complexes through the Use of Multiple Cross-Linkers. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:4461–4469. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao X., Tan F., Cao X., Cao Z., Li B., Shen Z., Tian Y. PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells during atherosclerosis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2020;52:9–17. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmz135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The deposited data of this study are presented in key resources table. The data of the RNA-seq (SRA code PRJNA1130042) was deposited to the NIH SRA database. All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.