Abstract

Background

As the share of the older population is set to rise from 8% in 2011 to 16% by 2036 in India, the increasing burden of NCDs and the increasing co-morbidities among the older population need greater policy focus to ensure a healthier aging process. Given the structural shifts in the age structure of the population and decreasing family sizes, contextual factors take an even more important role in shaping the health status of the elderly. Therefore, the present study aims to study the intersectional dynamics of demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and contextual factors on the prevalence of co-morbidities among the older population.

Methods

The data from the Indian Human Development Survey, 2012 (IHDS-II), were used to analyze the prevalence of co-morbidity and its confounding factors in India. Univariate analysis for sample distribution, bivariate analysis for the distribution of disease by different predictors with a chi-square test, and logistic regression analyses were used to assess the adjusted association of multimorbidity with different background variables.

Results

Overall, around 7% of the older population in India suffers from co-morbidities. We observe that the prevalence of co-morbidities is significantly higher among non-poor (People belonging to a non-poor household category based on the consumption quintiles) older females living alone, non-poor older females living jointly, and among non-poor older males living alone. The odds of having comorbidity among female non-poor and living alone are higher as compared to the female poor living alone. When all the co-variates are included in a single model, we observe that older adults living in nuclear families and residing in the North, Central, and Southern regions of India along with other factors discussed above show higher odds of having co-morbidities.

Conclusions

The research findings suggest that directing increased investments towards addressing multiple health issues in the elderly population, with a particular focus on non-poor women and men living alone, could be a more effective strategy in combating multimorbidity among older individuals in India.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Intersectional, Contextual factors, Older population, IHDS

| Text box 1. Contributions to the literature |

|---|

| • The manuscript analyzes the prevalence of comorbidity and its variations among diverse Indian population groups by examining gender roles, economic status, and living arrangements, which are crucial in later life stages. |

| • Gender biases in favour of males diminish as economic status and living arrangements influence comorbidity risks, highlighting the importance of other factors in later-life comorbidity patterns in India. |

| • The research delves into intersectional dynamics, crucial for pinpointing vulnerable groups and shaping tailored health policies, targeted interventions, enhanced care facilities, and robust familial support for India’s aging population, addressing gaps in chronic disease management evidence. |

Introduction

India is at the crossroads of various changes that are vital in shaping the lives of its vast majority of the population. One such important change witnessed since the 1990s is the shift in the epidemiological transition, which indicates a steady increase in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases [1, 2]. The mortality transition began in the 1950s but declined faster from the 1970s through the 1980s in India because of programmatic efforts to improve public health and related technologies. However, India’s typical structure of epidemiological transition shows that the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) has increased in recent decades, while the prevalence of communicable diseases is also relatively high. Data from the SRS 2015-17 revealed that while 58% of deaths among the urban population could be attributed to noncommunicable diseases, communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions also accounted for approximately 19% of all deaths [3].

The double burden of disease not only puts a strain on the already overburdened health system of the country but also diverts significant socioeconomic resources apart from causing immense loss of life. Existing epidemiological studies attribute up to 60% of all deaths in India to NCDs [4], and this number is projected to rise in the coming decades. These rising numbers are mostly attributed to the transition in lifestyle characterized by fewer active hours, prolonged exposure to stress, and unhealthy dietary intake [5–7]. Coupled with the early onset of NCDs, clustering of disease risk factors and the natural deterioration of physical and social health status due to old age, the elderly population in India faces manifold vulnerabilities. The situation is further exacerbated by issues such as the presence of multiple chronic conditions, which, for most of the older population, may remain undiagnosed due to a lack of accessibility and affordability of health care service needs.

As the share of the older population is set to increase from 8% in 2011 to 16% by 2036 in India [8, 9], the increasing burden of NCDs needs greater policy focus to ensure a healthier aging process. However, the epidemic of chronic illnesses cannot be mitigated without realizing the role of the socioeconomic gradient of health in older individuals. Factors such as sex, living arrangement, socioeconomic status, and level of education have been found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of chronic illnesses among older adults [10–12]. In contemporary times, one of the major policy focuses is the well-being of the burgeoning elderly population in India due to the rapid demographic transition. Unlike its western counterparts, aging is a new phenomenon in India and is a greater concern. Previous studies [13] have predicted that India may be at risk of “getting old before getting rich”. Therefore, without proper investigations and understanding of the issues and determinants related to various aspects of elderly individuals, India will be unprepared to ensure the well-being of its increasingly graying population. In addition to increasing numbers, other factors, such as the rise of noncommunicable diseases, the weakening of familial ties and an inadequate social security system, leave a large majority of the older population at a vulnerable position.

Owing to its unique social and cultural predilections, understanding the impacts of changing familial support systems on the well-being of the older population is important. For example, a large majority of those aged 60 years and above generally live with spouses or alone in Western countries [14]; however, co-residence with elderly individuals is both preferred and socially recognized [15]. These familial arrangements were based on the principle of intergenerational transfer of wealth, knowledge and care. However, with the advent of modernization and globalization, a shift in the tendency toward elderly individuals living alone or with spouses only has been witnessed in India [16–20]. Health is considered one of the most important domains for ensuring overall well-being. In India, the thrust of national policies and programs has been aligned with improvements in maternal and neonatal indicators. However, the growing share of NCDs in the overall disease burden as well as the early onset of such illness [21, 22] indicates an undeniable need to address and identify the various issues pertaining to the prevalence of morbidities among the older age group, especially in a resource-constrained setting such as India.

The ample research regarding the health status of older adults indicates an increasing prevalence of comorbidities [23–25]. The presence of two or more chronic diseases or comorbidities is associated with an increase in expenditures on health, often catastrophic in nature, which in turn increases the economic vulnerability of the older population. These deprivations are further exacerbated by various socioeconomic inequalities and poor health-care facilities. Another plausible source of comorbidities among the older population may be the social and cultural setting in India [26, 27]. For example, traditionally, the care of elderly people was looked over by their family; therefore, with the shift in living arrangements, the weakening of kinship structure and increased migration of adult males and females for better educational and employment opportunities have left them vulnerable and lacking a care-giving system [16, 28, 29].

Living arrangements are hypothesized to be important predictors of the health status of elderly individuals. Living arrangements significantly affect a multitude of individual-level capacities to provide support and individuals’ ability to meet their daily needs according to the resources available to them. Research has shown that elderly individuals who are in co-residence with other family members are associated with lower mortality than those who are living alone [24, 30]. On the other hand, co-residence is often associated with greater dependence on other family members, which increases the physical inability to perform activities of daily living. Similarly, co-residing with the older population may lead to conflicts in decision making along with lifestyle differences, which increase the risk of poor mental and physical health [12, 20, 31]. Therefore, as an increasing number of individuals are expected to survive to older ages, factors such as living arrangements and social support, which affect their health status throughout their life course, also need to be studied. Given the probable transition in the age structure of the population and decreasing family sizes, contextual factors play an important role in shaping the health status of elderly individuals. However, the associations between changes in socioeconomic factors along with lifestyle and contextual factors and morbidity in older people have not been studied extensively. Therefore, the present study aims to fill this gap by exploring the effects of demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle and contextual factors on the prevalence of comorbidities among the older population aged 60 years and above.

Conceptual framework

In the Indian context, very few studies have explored the impact of living arrangements among the older population in India, especially in the context of the prevalence of the comorbid situation, despite its wider policy implications. Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical framework on which the study is based, accounting for the effect of the living arrangements of the elderly as well as other important covariates, such as personal, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Framework of the study

Our main interest lies in the effects of contextual factors on the prevalence of comorbidities among the older population. Earlier studies also highlight the associations between them in the context of developed and developing countries [32, 33]. The effects of contextual factors such as region and place of residence are often considered intrinsic and complex, especially in diverse countries such as India, and therefore need to be untangled to understand the effects of other social determinants of health outcomes among elderly individuals.

Data and methods

Study design

For the analysis of comorbidity incidence and its confounding factors in India, data from the Indian Human Development Survey, 2012 (IHDS-II), were used. The IHDS survey collects information from more than 40 thousand households from 2004 to 2005 and follows the same households from 2011 to 2012. The IHDS survey collected information on socioeconomic status, health, nutrition, learning of children, disease, immunization, fertility, mortality, migration, and health facilities of the country. The IHDS survey is a longitudinal survey and was successfully reinterviewed with approximately 39 thousand households from 2004 to 2005 to 2011–2012 [34, 35]. The survey followed multistage stratified systematic sampling for the selection of villages in rural areas and urban blocks in urban areas. For the detailed sampling design and procedures, see the IHDS website (https://ihds.umd.edu/about/citing-ihds).

Outcome variables

The main outcome variable of this study was comorbidity, which was the condition of having more than one chronic disease at the time of the survey. Chronic disease is defined as a condition that lasts more than a year and demands regular medical attention or a condition that limits activities of daily living or the condition of both (https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm). The survey asked the individual who has a doctor ever diagnosed with a cataract, tuberculosis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, leprosy, cancer, asthma, polio, paralysis, epilepsy, mental illness, or other long-term diseases. The response was entered into three categories, i.e., yes, no, and cured. The main outcome variables of having comorbidity are defined as having more than one disease at the time of the survey by combining the cured and no disease into one category and yes disease into one category. Therefore, the older population reported that they had ever been diagnosed with more than one of the diseases listed above was defined as a comorbid individual.

Covariates

This study included several sociodemographic, lifestyle, household status, and contextual-level factors that determine the prevalence of comorbidities among the older population in India. We also included the intersection of living arrangement, gender, and poverty to examine the prevalence differentials of comorbidities among the older population. The individual ages were categorized into 60–69 years, 70–79 years and 80 years and above. Marital status was categorized as married, never married or other. Similarly, the education of the individual is categorized as no schooling, primary, middle, secondary, higher secondary and above. Compared with Hindu, general caste and higher Consumption tertiles households, Indian populations belonging to certain religions (Muslim), caste (schedule caste and schedule tribe) and economic status (bottom consumption tertiles) have poor health and nutritional outcomes [1, 11, 12]. Therefore, the present study includes these factors as probable predictors of having comorbidities among the older population. The caste groups have been categorized as SC/ST, OBC, other, and religious groups such as Hindu, Muslim, and other. The economic status estimated through consumption tertiles at household level and categorized as bottom, middle and higher. The bottom consumption tertiles categorized as poor and middle and high tertiles grouped as non-poor. The individual chewing of tobacco, smoking of tobacco and alcohol consumption were categorized as never, sometimes, or daily. The living arrangements are categorized as living alone/spouses with no children/sibling, living alone/spouses with children/sibling, and living with children and others. Furthermore, individuals residing in rural and urban areas, along with different statuses and regions, also have very significant differences in health and nutritional status in multicultural countries such as India. The region of residence used as a predictor of comorbidity among the older population in this analysis included rural and urban households and households belonging to six regions, i.e., North (including Delhi, Haryana, Jammu & Kashmir, Rajasthan, Punjab, Himanchal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Chandigarh), Central (including Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh), East (including West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Odisha), West (including Gujarat, Goa, Daman & Diu, Dadar & Nagar Haveli and Maharashtra), South (including Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Pondicherry and Tamil Nadu), Northeast (including Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Sikkim, Nagaland, and Tripura).

Analytical approach

The analytical approach applied for this analysis has been classified into two stages. The first stage comprises the sample distribution of the study population and selected variables. Similarly, the distributions and prevalence rates of different chronic diseases among populations above 60 years of age were also estimated along with confidence intervals. Furthermore, bivariate analysis was carried out to estimate the prevalence of multimorbidity (the copresence of two or more diseases at the time of the survey) and its differences across the selected demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle and contextual factors among the older population. The chi-square test was used to assess whether the differences in comorbidities according to different predictors were statistically significant. The second stage of the statistical analysis for the present study was to test the adjusted associations between comorbidities and their selected predictors through the application of binary logistic regression models. Logistic regression was performed by considering four sets of predictors separately [11, 12] and taking all the predictors into one single model to explain the importance of different background variables for determining the burden of comorbidities among the population aged 60 years and above in India from 2011 to 12. All analyses in the present study were performed with Stata software 13.

Results

Description of the study sample

Table 1 shows the sample distribution of the present study. The results revealed that 52% of the older population was female and that ~ 60% was aged 60–69 years. However, more than 10% of the population in the study sample is 80 years and older. Approximately 37% of the population was either widowed or separated or divorced. More than half of the older population were illiterate, whereas only 6% had secondary and higher secondary and above. The results also revealed the distribution of the older population on the basis of caste group. Approximately 44% of the older population belonged to the OBC, followed by either general or others (31%) and SC or ST (26%). More than 80% of the older population were Hindu, and over 35% were in the bottom consumption tertile. The living arrangements of the older population show that 50% population is living alone as left behind (living alone or with spouses while their children live somewhere else). However, approximately 4% of the older population in India lived alone or with spouses without children from 2011 to 12. Furthermore, approximately 60% of the older population chew tobacco or gutkha daily, and approximately 36% smoke tobacco. Approximately 5% of the older population drank alcohol daily, and 74% reported that they never had alcohol.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study variables, India, 2011-12

| Sample Distribution | Percentage (%) | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity Status | ||

| No Comorbidity | 93.1 | 20,420 |

| Comorbidity | 6.9 | 1,505 |

| Age | ||

| 60–69 | 60.2 | 13,189 |

| 70–79 | 28.1 | 6,169 |

| 80+ | 11.7 | 2,563 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48.5 | 10,636 |

| Female | 51.5 | 11,289 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 60.3 | 13,213 |

| Widowed | 37.3 | 8,167 |

| Others | 2.5 | 545 |

| Educational Status | ||

| No Schooling | 58.9 | 12,919 |

| Primary | 10.5 | 2,307 |

| Middle | 18.1 | 3,966 |

| Secondary | 6.4 | 1,409 |

| Higher Secondary and above | 6.0 | 1,324 |

| Caste | ||

| SC/ST | 25.7 | 5,641 |

| OBC | 43.5 | 9,530 |

| Others | 30.8 | 6,753 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 84.0 | 18,410 |

| Muslim | 9.7 | 2,133 |

| Others | 6.3 | 1,382 |

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Living Alone/Spouse, No child/sibling | 4.3 | 952 |

| Living Alone/Spouse, child/sibling | 49.6 | 10,880 |

| Living with children and Others | 46.0 | 10,093 |

| Consumption Tertiles | ||

| Bottom | 37.7 | 8,266 |

| Middle | 33.2 | 7,278 |

| Higher | 29.1 | 6,371 |

| Chewing Tobacco | ||

| Never | 33.0 | 2,332 |

| Sometimes | 7.8 | 549 |

| Daily | 59.3 | 4,195 |

| Smoke Tobacco | ||

| Never | 54.0 | 3,824 |

| Sometimes | 10.5 | 745 |

| Daily | 35.5 | 2,510 |

| Alcohol Consumption | ||

| Never | 73.5 | 5,205 |

| Sometimes | 21.1 | 1,493 |

| Daily | 5.4 | 380 |

| Place of Residence | ||

| Rural | 70.4 | 15,443 |

| Urban | 29.6 | 6,482 |

| Region | ||

| North | 14.5 | 3,172 |

| Central | 21.6 | 4,725 |

| East | 21.2 | 4,657 |

| Northeast | 2.7 | 595 |

| West | 14.7 | 3,227 |

| South | 25.3 | 5,549 |

Furthermore, the distribution of the older population aged 60 years and above in the IHDS-2 shows that approximately 70% of the population is living in rural India, whereas only 30% is living in urban India. The regional distribution of the older population also shows a skewed pattern where South India is the top region (25%), followed by Central (21%), East (21%), West (15%), North (14%) and Northeast (3%).

Differences in morbidity prevalence

Table 2 shows the prevalence and proportion of the older population with different diseases in India. Approximately 7% of the older population in India suffers from comorbidities. Among the morbidities, illnesses such as cataracts (6%), blood pressure (11%), diabetes (7%) and asthma (5%) are more common among older adults.

Table 2.

Chronic disease status and prevalence rates among the older population in India, 2011-12

| Morbidities | Sample (n) | Prevalence Per 1000 | Proportion | Standard Error. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Cataract | ||||||

| No | 20,702 | 944 | 94.2 | 0.003 | 93.6 | 94.7 |

| Yes | 1,223 | 56 | 5.8 | 0.003 | 5.3 | 6.4 |

| Tuberculosis | ||||||

| No | 21,761 | 992 | 99.1 | 0.001 | 98.9 | 99.3 |

| Yes | 164 | 7 | 0.9 | 0.001 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Blood Pressure | ||||||

| No | 19,191 | 875 | 88.6 | 0.003 | 88.0 | 89.1 |

| Yes | 2,734 | 125 | 11.4 | 0.003 | 10.9 | 12.0 |

| Heart Morbidity | ||||||

| No | 21,253 | 969 | 97.2 | 0.001 | 97.0 | 97.5 |

| Yes | 672 | 31 | 2.8 | 0.001 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 20,334 | 927 | 93.4 | 0.002 | 92.9 | 93.7 |

| Yes | 1,591 | 73 | 6.6 | 0.002 | 6.3 | 7.1 |

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 21,873 | 998 | 99.8 | 0.000 | 99.7 | 99.8 |

| Yes | 52 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.000 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| No | 20,968 | 956 | 95.3 | 0.003 | 94.8 | 95.8 |

| Yes | 957 | 44 | 4.7 | 0.003 | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| Leprosy | ||||||

| No | 21,892 | 998 | 99.8 | 0.000 | 99.8 | 99.9 |

| Yes | 33 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.000 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Epilepsy | ||||||

| No | 21,836 | 996 | 99.6 | 0.000 | 99.5 | 99.7 |

| Yes | 89 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.000 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Mental Illness | ||||||

| No | 21,813 | 995 | 99.4 | 0.001 | 99.2 | 99.5 |

| Yes | 112 | 5 | 0.6 | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| No Comorbidity | 20,325 | 927 | 93.1 | 0.002 | 92.7 | 93.6 |

| Comorbidity | 1,601 | 73 | 6.9 | 0.002 | 6.4 | 7.3 |

Table 3 shows the prevalence of comorbidities among older adults by background characteristics such as age, sex, social group, and educational status. We observed that, among the socioeconomic characteristics, the prevalence of comorbidities was greater among older adults aged 70–79 years, significantly greater among older adults who had gained education to the secondary level, and belonged to other religious and caste groups. Older adults who belong to higher consumption tertiles and live in urban areas and in the southern region also seem to have a higher prevalence of comorbidities than their counterparts. Other factors, such as those who chew tobacco sometimes also show a significantly greater prevalence of comorbidities, whereas adults who smoke tobacco and consume alcohol do not show any significant variation from their counterparts.

Table 3.

Comorbidity incidence among the older population in India, 2011-12

| Sample Distribution | No Comorbidity | Comorbidity | Pearson Chi2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 60–69 | 93.6 (12,347) | 6.4 (842) | 11.81** |

| 70–79 | 92.2 (5,688) | 7.8 (481) | |

| 80+ | 92.9 (2,381) | 7.1 (182) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 93.5 (9,940) | 6.6 (696) | 4.6* |

| Female | 92.8 (10,480) | 7.2 (809) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 93.1 (12,301) | 6.9 (912) | 0.58 |

| Widowed | 93.2 (7,613) | 6.8 (554) | |

| Others | 92.8 (506) | 7.2 (39) | |

| Educational Status | |||

| No Schooling | 95.1 (12,288) | 4.9 (630) | 228.8*** |

| Primary | 90.7 (2,093) | 9.3 (214) | |

| Middle | 91.3 (3,621) | 8.7 (345) | |

| Secondary | 87.5 (1,234) | 12.5 (176) | |

| Higher Secondary and above | 89.4 (1,183) | 10.6 (140) | |

| Caste | |||

| SC/ST | 95.8 (5,406) | 4.2 (236) | 113.3*** |

| OBC | 93.3 (8,891) | 6.7 (640) | |

| Others | 90.7 (6,124) | 9.3 (630) | |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | 93.6 (17,227) | 6.4 (1,183) | 83.9*** |

| Muslim | 91 (1,940) | 9.1 (193) | |

| Others | 90.7 (1,253) | 9.3 (129) | |

| Consumption Tertiles | |||

| Bottom | 95.7 (7,909) | 4.3 (357) | 200.8*** |

| Middle | 93.3 (6,789) | 6.7 (489) | |

| Higher | 89.7 (5,711) | 10.4 (660) | |

| Chewing Tobacco | |||

| Never | 95.2 (2,219) | 4.8 (113) | 6.8* |

| Sometimes | 92.5 (507) | 7.5 (41) | |

| Daily | 95.8 (4,020) | 4.2 (175) | |

| Smoke Tobacco | |||

| Never | 94.6 (3,617) | 5.4 (208) | 26.7*** |

| Sometimes | 95.3 (710) | 4.7 (35) | |

| Daily | 96.5 (2,423) | 3.5 (87) | |

| Alcohol Consumption | |||

| Never | 95.5 (4,969) | 4.5 (236) | 0.55 |

| Sometimes | 95.1 (1,420) | 5 (74) | |

| Daily | 94.6 (359) | 5.4 (20) | |

| Living Arrangements | |||

| Living Alone/Spouse, No child/sibling | 92.4 (947) | 7.6 (89) | 4.2* |

| Living Alone/Spouse, child/sibling | 92.7 (9,927) | 7.3 (800) | |

| Living with children and Others | 93.6 (9,451) | 6.4 (712) | |

| Place of Residence | |||

| Rural | 94.8 (14,644) | 5.2 (799) | 224.8*** |

| Urban | 89.1 (5,776) | 10.9 (707) | |

| Region | |||

| North | 95 (3,014) | 5 (158) | 427.8*** |

| Central | 95.2 (4,500) | 4.8 (226) | |

| East | 94.6 (4,407) | 5.4 (250) | |

| Northeast | 97.2 (578) | 2.8 (17) | |

| West | 94.7 (3,055) | 5.3 (172) | |

| South | 87.7 (4,867) | 12.3 (683) |

Among various living arrangements, those who live alone have a higher prevalence of comorbidities than those who live with children and others do, although the difference is not very significant (Table 3). To understand the association between living arrangements and the prevalence of comorbidities among older adults, previous studies have suggested that the association should be viewed in intersection with sex and the economic status of older adults. This is based on the hypothesis that a lack of kinship support and individual economic resources render older adults doubly vulnerable to comorbidities; additionally, the exclusion of females from intergenerational transfers of wealth adds another layer of vulnerability.

Intersectional lens of gender, economic status and living arrangements

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of comorbidities through the intersection of gender, poverty and living arrangements among the older population in India. We observed that the prevalence of comorbidities was significantly greater among nonpoor older females living alone, nonpoor older females living jointly and nonpoor older males living alone. Male poor individuals living together had the lowest comorbidity prevalence, followed by female poor individuals living together. Male living alone (5%) had fewer comorbidities than their female counterparts did (5%). Furthermore, male nonpoor individuals living jointly had a significantly lower prevalence of comorbidities than did their female nonpoor individuals living jointly. Thus, the overall picture of this intersection of gender, economic status and living arrangements clearly shows a demarcation of having greater comorbidity among females, nonpoor individuals and those living alone in the older population.

Fig. 2.

Deciphering comorbidity prevalence through intersection of gender, poverty and living arrangements among older population in India, 2011-12

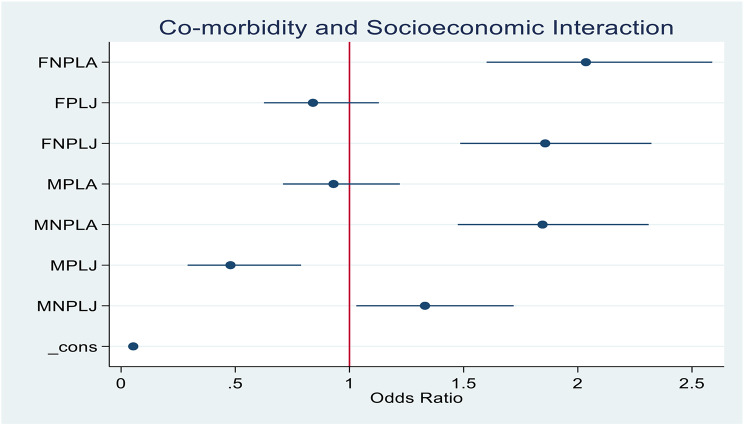

The adjusted analysis of the unequal burden of comorbidities among the subgroups according to sex, economic status and living arrangements also revealed variable results (Fig. 3). The odds of having comorbidities among nonpoor females and those living alone are greater than those among poor females living alone. Similarly, females who are nonpoor living jointly are more likely to have comorbidities than females who are poor living alone. Thus, the findings of the present research suggest the need for multidimensional interventions to avoid the unfair burden of multimorbidity on certain population groups.

Fig. 3.

Binary logistic regression for Deciphering comorbidity prevalence through intersection of gender, poverty and living arrangements among older population in India, 2011-12

Adjusted associations of sociodemographic, lifestyle, and contextual factors with morbidity incidence in India

Table 4 shows the odds ratios of comorbidity incidence among older adults in India according to various background variables. Models 1 and 2 show the odds ratios of comorbidity incidence by demographic and socioeconomic covariates, respectively. The results indicate that demographic characteristics such as increased age and being female are associated with increased odds of suffering from comorbidities. Moreover, among socioeconomic characteristics, the level of education is significantly positively associated with increased odds of comorbidities. In other words, older adults with a secondary education level and above are 3 times more likely to have comorbidities than their counterparts with no schooling. Similarly, older adults from economically better-off families are two times more likely to have comorbidities than their poorer counterparts are. In terms of lifestyle factors such as chewing or smoking tobacco and consuming alcohol, only the latter had slightly greater odds of comorbidities (Model 3). In terms of contextual factors, belonging to left-behind families, residing in urban areas and living in southern regions is associated with higher odds of having comorbidities among older adults (Model 4). However, when all the covariates are included in a single model, we observe that older adults living in nuclear families and residing in North, Central and Southern India, along with the other factors discussed above, are more likely to have comorbidities (Model 5).

Table 4.

Covariates of comorbidities among the older population according to their background characteristics in India, 2011-12

| Predictors | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic/Socioeconomic Factors | Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | Model V | ||||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||

| 60–69 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 70–79 | 1.30 | 0.000 | 1.16–1.46 | 1.25 | 0.000 | 1.11–1.41 | |||||||||

| 80+ | 1.34 | 0.001 | 1.14–1.59 | 1.19 | 0.051 | 1-1.42 | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.59 | 0.000 | 1.41–1.8 | 1.20 | 0.007 | 1.05–1.37 | |||||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||||||||

| Currently Married | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Widowed | 1.02 | 0.702 | 0.9–1.16 | 1.24 | 0.027 | 1.03–1.5 | |||||||||

| Others | 1.07 | 0.708 | 0.76–1.49 | 1.28 | 0.193 | 0.88–1.84 | |||||||||

| Educational Status | |||||||||||||||

| No Schooling | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Primary | 2.43 | 0.000 | 2.07–2.85 | 1.77 | 0.000 | 1.5–2.09 | |||||||||

| Middle | 2.30 | 0.000 | 2.01–2.65 | 1.50 | 0.000 | 1.29–1.74 | |||||||||

| Secondary | 3.31 | 0.000 | 2.75–3.98 | 1.84 | 0.000 | 1.5–2.26 | |||||||||

| Higher Secondary and above | 3.17 | 0.000 | 2.62–3.84 | 1.61 | 0.000 | 1.29-2 | |||||||||

| Socioeconomic Factors | |||||||||||||||

| Caste | |||||||||||||||

| SC/ST | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| OBC | 1.57 | 0.000 | 1.34–1.83 | 1.07 | 0.397 | 0.91–1.26 | |||||||||

| Others | 1.77 | 0.000 | 1.51–2.07 | 1.42 | 0.000 | 1.21–1.68 | |||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

| Hindu | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Muslim | 1.37 | 0.000 | 1.18–1.6 | 1.47 | 0.000 | 1.25–1.73 | |||||||||

| Others | 1.76 | 0.000 | 1.49–2.08 | 1.54 | 0.000 | 1.29–1.84 | |||||||||

| Consumption Tertiles | |||||||||||||||

| Bottom | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Middle | 1.48 | 0.000 | 1.28–1.71 | 1.37 | 0.000 | 1.18–1.6 | |||||||||

| Higher | 2.15 | 0.000 | 1.88–2.47 | 1.92 | 0.000 | 1.65–2.23 | |||||||||

| Living Arrangements | |||||||||||||||

| Joint (Living with children and Others) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| Left behind (Living Alone/Spouse, child/sibling) | 1.09 | 0.46 | 0.86–1.38 | 1.25 | 0.114 | 0.95–1.66 | |||||||||

| Nuclear (Living Alone/Spouse, No child/sibling) | 1.06 | 0.26 | 0.96–1.18 | 1.35 | 0.001 | 1.13–1.62 | |||||||||

| Lifestyle Factors | |||||||||||||||

| Chewing Tobacco | |||||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chewing | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.57–0.78 | 0.95 | 0.553 | 0.81–1.12 | |||||||||

| Smoke Tobacco | |||||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Smoke | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.37–0.55 | 0.61 | 0.000 | 0.5–0.75 | |||||||||

| Alcohol Consumption | |||||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Drinks | 1.05 | 0.67 | 0.84–1.32 | 1.03 | 0.781 | 0.81–1.32 | |||||||||

| Contextual Factors | |||||||||||||||

| Place of Residence | |||||||||||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Urban | 2.03 | 0.000 | 1.83–2.25 | 1.47 | 0.000 | 1.31–1.65 | |||||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| North | 1.00 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| Central | 0.91 | 0.335 | 0.76–1.1 | 1.17 | 0.112 | 0.96–1.42 | |||||||||

| East | 0.94 | 0.554 | 0.78–1.14 | 1.14 | 0.189 | 0.94–1.39 | |||||||||

| Northeast | 0.47 | 0.001 | 0.3–0.73 | 0.44 | 0.000 | 0.28–0.69 | |||||||||

| West | 0.92 | 0.442 | 0.76–1.13 | 0.94 | 0.560 | 0.77–1.16 | |||||||||

| South | 2.51 | 0.000 | 2.18–2.89 | 2.78 | 0.000 | 2.39–3.23 | |||||||||

Discussion and conclusion

The study revealed that the comorbidity prevalence increased substantially when the intersectionality of sex, economic status, and living arrangement were taken into consideration. The complex interplay of different socioeconomic, demographic, lifestyle, and contextual factors responsible for considerable variation in comorbidities among the older population was evident from this study. Research conducted in Ghana under similar circumstances emphasizes that women, irrespective of whether they reside in urban or rural areas, are particularly susceptible to chronic diseases and comorbidities compared to men [36]. The associations between comorbidities and individual- or household-level predictors, such as age and sex, revealed a greater burden of comorbidities among females than among their male counterparts. This holds true when controlling for other household, lifestyle, and contextual factors in the analysis [37–39]. The greater burden of morbidities and comorbidities among the female older population can be explained through two alternative hypotheses. The first is the lower level of health care-seeking behavior among females, which again is compounded by the unequal burden of gender roles prevailing in society [39]. The second hypothesis of higher morbidity and comorbidity prevalence among older females is that they tend to report higher morbidity due to their experiences and psychological perceptions of life and health [40, 41]. The prevalent non-communicable disease (NCD) morbidities among both genders included hypertension, depression, gastrointestinal issues, and diabetes, with minimal variations between the sexes. The most significant disparity 11% in magnitude was observed in physical-mental multimorbidity within the 75 + age group [42].

The study also revealed that widowed individuals and others are more likely to report comorbidities than their currently married counterparts [43]. The social norms and acceptance of marriage lead to many new roles and practices that help individuals engage in social support systems to cope with adversity and misfortune them from illness and health shocks. Widowhood, separation, and even not being married at older ages make them feel loneliness, discrimination and isolation, which surely have lasting impacts on their quality of life and cardiovascular health [44, 45]. Loneliness is more common among widows, women with a lower educational status, and women in the bottom wealth quintile [45–49]. The Indian tradition and culture of the household is such that married women are expected to nurture the family, which must provide the means of sustenance. However, as they grow older, they become more dependent on others for nutrition, health, and social and economic support [50].

Despite having a historically strong familial support system for the older population, the country also registers more frequent reporting of neglect and abuse [51, 52]. Thus, there is a greater chance of the older population being in distress to mental health and well-being, which leads to the onset of other chronic morbidities [48, 53].

Furthermore, the study revealed a positive association between education and comorbidities among older people in India. This is because education mostly results in higher wealth or income. The strong association of having comorbidities with a higher level of economic status is also true [59]. The lifestyles adopted by rich people are mostly sedentary, which is one of the prime reasons for the development of comorbidities. The association of comorbidities with economic status is inconsistent, and conclusions based on self-reports are questionable [54–58]. The more educated population tends to have more health concerns and reports more accurately than uneducated or less educated older population. The economic affluency coming along side better education also had better reporting of different diseases and mostly diagnosed one [55, 57, 59, 60]. Similarly, the results also revealed considerable differences in the likelihood of comorbidities among older people across caste and religion statuses [12, 38, 39, 61, 62]. Similarly, the living arrangements of the older population have emerged as predictors of comorbidities in multicultural countries such as India [63, 64].

The empirical evidence for known probable risk factors for chronic diseases, such as the consumption of tobacco and alcohol, is also important for predicting comorbidities among older individuals in India [65]. A study has estimated that tobacco alone contributes to approximately 6% of the total burden of disease in India [66]. India has the highest oral cancer burden worldwide [67]. The study revealed that older people who never smoked or chewed tobacco had significantly lower odds of comorbidities than did those who chewed or smoked or smoked tobacco. The higher prevalence of tobacco consumption among poorer and less educated older people has changed significantly [68, 69]. Therefore, there is a need for policy interventions that address abstinence from tobacco consumption in general and among older people in particular.

Moreover, at the contextual level, factors such as place of residence and region of residence also significantly differ in terms of comorbidity prevalence among the older population in India. Compared with their rural counterparts, urban areas are more likely to have comorbidities. The lower chances of comorbidity among the older population residing in rural India are in fine tune with earlier evidence [70–72]. Compared with the other Indian regions, the South Indian region has greater odds of having comorbidities among the older population. The difference in comorbidity prevalence by contextual factors can be explained by the fact that there might be a lower reporting of morbidity in some areas and regions because of the inequitable distribution of health care services in scarce resource settings [73]. However, the future research endeavors should prioritize investigating factors contributing to regional differences in comorbidity prevalence, delving deeper into aspects like environmental exposures, dietary patterns, and healthcare-seeking behaviors. These factors could offer valuable insights into the disparities noted in South India and urban regions. Furthermore, Intersectional analysis highlighted that nonpoor females and those living alone face higher odds of comorbidities compared to poor females living alone. Contrasting with their economically disadvantaged counterparts, poor-income females displayed lower odds of comorbidities. The research underscores the intricate interplay of sociocultural factors in Indian society, highlighting the need for nuanced strategies to combat the heightened prevalence of comorbidities among the elderly population in the country.

With a focus on the intricate challenges at hand, the government has implemented the National Program for the prevention and control of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases in India. This initiative underscores the significance of early detection and prompt treatment of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), alongside efforts to enhance healthcare infrastructure and capacity building. The establishment of NCD cells at various levels, including state, district, and Community Health Centers, is a pivotal step towards addressing specific NCDs nationwide [74]. Moreover, the government has also implemented the National Program for the Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) in accordance with the National Policy on Older Person and the United National Convention on the Rights of Older and Disabled People by comprehensively focusing on the access to and availability of health care services in general and NCD care services in particular. While there is a positive governmental intent to address health issues among the elderly in India, there remains a scarcity of initiatives that offer focused interventions for vulnerable.

The findings suggest the expansion of health care infrastructure, such as physical and manpower, for timely diagnosis and treatment, with special consideration of certain socioeconomic and contextual factors for need-based care and treatments. The increased odds of older nonpoor females living alone and nonpoor females living jointly can be targeted with increased intensity for the care and treatment of comorbidities, along with their male counterparts.

Finally, the empirical advancements of this study have several limitations. The study considered self-reported morbidities, which are strongly associated with literacy and economic status. There are high chances that individuals may misclassify their diseases. However, self-reports of diseases are adequate and are the most commonly used indicators of health and disease prevalence in India [75, 76]. We have not used biomarkers and anthropometric information to measure the height and weight of the adults due to several caveats, such as missing information and inconsistency in the reporting of the data. Similarly, the study is based on cross-sectional data, and self-reported morbidities which limits the ability to make causal inferences. However, this study can be used as a basis for future studies exploring the reasons for comorbidity prevalence among certain sociodemographic and contextual groups of populations in countries such as India.

Conclusion

The research highlights the multifaceted factors impacting comorbidity levels among elderly individuals in India. Significant influences include sex, economic status, and living arrangements, with older women, especially those living alone, showing heightened vulnerability to chronic diseases. Social and marital status, education, and economic well-being play crucial roles in shaping disease reporting accuracy and comorbidity prevalence. Tobacco and alcohol use are identified as key predictors of comorbidities, with disparities linked to socioeconomic status. Regional variations underscore the necessity for targeted interventions addressing lifestyle and healthcare-seeking behaviors. While government initiatives focus on enhancing healthcare access and NCD care for the elderly, addressing the intricate determinants of comorbidity prevalence is vital for improving healthcare delivery and outcomes in India.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank IHDS for making the data available for this research in the public domain. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous referees and the editors for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Abbreviations

- IHDS

India Human Development Survey

- NCDs

Non Communicable Diseases

- NPCDCS

National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes Cardiovascular disease, and Stroke

- CHC

Community Health centre

- NPHCE

National Program for the Health care of the Elderly

- OBC

Other Backward Class

- ST

Scheduled Tribe

- SC

Scheduled Caste

Author contributions

KN and PKP conceptualized, analysis and finalized the manuscript. KN and PKP has done final proofreading and editing.

Funding

Not applicable. The paper is an independent work of the authors.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The present study uses the dataset available in the public domain as part of the authors’ independent research work. The ethical approval to use the data granted by the University of Maryland and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi. Thus, there is no need to seek separate ethical clearance for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arokiasamy P. India’s escalating burden of noncommunicable diseases. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(12):e1262–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalaiselvi S, Shewade HD, Chinnakali P. Rising burden of Non-Communicable diseases in India. Are we ready for the NCD challenge?? Indian J Rural Heal Care. 2013;1:176–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the States of India, 1990–2016 in the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2017;390:2437–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nethan S, Sinha D, Mehrotra R. Non communicable disease risk factors and their trends in India. Asian Pac J cancer Prev (APJCP). 2017;18(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Castelli WP. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Am J Med. 1984;76(2):4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study. 2019. Accessed from; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- 7.GBD Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and National age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Population Reference Bureau. India’s aging population. Washington, DC.

- 9.National Commission on Population Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2019). Population Projections for India and States, 2011–2036. Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections, (2012).

- 10.Singh L, Goel R, Rai RK, Singh PK. Socioeconomic inequality in functional deficiencies and chronic diseases among older Indian adults: a sex-stratified cross-sectional decomposition analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e022787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Pandey A, Ladusingh L. Socioeconomic correlates of gender differential in poor health status among older adults in India. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(7):879–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh PK, Singh L, Dubey R, Singh S, Mehrotra R. Socioeconomic determinants of chronic health diseases among older Indian adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional multilevel study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028426. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goli S, Pandey A. Is India getting old before getting rich: beyond demographic assessment, in Anand, S., Kumar, I. and Srivastava, A, editors, Challenges of the Twenty First Century – A Trans-disciplinary Perspective, Macmillan Advance Research Series. (2010), New Delhi.

- 14.Palloni A. Living arrangements of older persons, In United Nations, editor, Living Arrangements of Older Persons: Critical Issues and Policy Responses. New York: Population Bulletin of the United Nations, Special Issue Nos. 42/43, United Nations, (2001), pp. 54 – 110. Google Scholar.

- 15.Sibai AM, Beydoun MA, Tohme RA. Living arrangements of ever-married older Lebanese women: is living with married children advantageous? J Cross-Cult Gerontol. 2009;24:5–17. 10.1007/s10823-008-9057-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Z, Falkingham J, Liu X, Vlachantoni A. Changes in living arrangements and mortality among older people in China. SSM-population Health. 2017;3:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu D, Liu G, Vlosky D, Zeng Y. Factors associated with place of death among the Chinese oldest old. J Appl Gerontol. 2007a;26(1):34–57. [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu D, Dupre M, Liu G. Characteristics of the institutionalized and community-residing oldest-old in China. Social Sci Med. 2007b;64(4):871–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lysack C, Neufeld S, Macneil S, Lichtenberg P. At risk in old age: elderly men who live alone. Clin Gerontologist. 2001;24(3):77–91. [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L. Living arrangements and subjective well-being among the Chinese elderly. Open J Social Sci. 2015;3:150–61. [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indrayan A. Forecasting vascular disease cases and associated mortality in India. Burd Disease India: Backgr Papers. 2005;197–218.

- 22.Siegel KR, Patel SA, Ali MK. Noncommunicable diseases in South Asia: contemporary perspectives. Br Med Bull. 2014;111(1):31–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, van den Bos GA. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya. Multiple chronic diseases and comorbidities among older adults in India: New insights from LASI Pilot Survey, 2010. (2013), Available at SSRN 2307650.

- 25.Anushree KN, Mishra PS. Prevalence of multi morbidities among older adults in India: evidence from National sample survey organization, 2017-18. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2022;15:101025. 10.1016/j.cegh.2022.101025. ISSN 2213–3984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paul A, Verma RK. Does living arrangement affect work status, morbidity, and treatment seeking of the elderly population?? A study of South Indian States. SAGE Open. 2016;6(3). 10.1177/2158244016659528.

- 27.Williams DR, Purdie-Vaughns V. Social and behavioral interventions to improve health and reduce disparities in health. Population health: behavioral and social science insights. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health; 2015. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, Holland A, Brasure M, Lohr KN, Harden E, Tant E, Wallace I. & M. Viswanathan health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review, evidence report/technology assessment: number 199. Rockville. MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falkingham J, Qin M, Vlachantoni A, Evandrou M. Children’s migration and lifestyle-related chronic disease among older parents ‘left behind’in India. SSM-population Health. 2017;3:352–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lund R, Due P, Modvig J, Holstein BE, Damsgaard MT, Andersen PK. Cohabitation and marital status as predictors of mortality—an eight year follow-up study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(4):673–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, Qian Z. Social support and self-reported quality of life China’s oldest old. In Healthy longevity in China. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008, pp. 357–376.

- 32.Jung SW, Lee KJ, Lee HS, Kim GH, Lee JG, Lee JH, Kim JJ. Relationship of activities outside work to sleep and depression/anxiety disorders in Korean workers: the 4th Korean working condition survey. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2017;11:29:51. 10.1186/s40557-017-0206-8. PMID: 29046812; PMCID: PMC5637281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunes BP, Chiavegatto Filho ADP, Pati S, Cruz Teixeira DS, Flores TR, Camargo-Figuera FA, Munhoz TN, Thume E, Facchini LA, Batista R. RContextual and individual inequalities of Multimorbidity in Brazilian adults: a cross-sectional national-based study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015885. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai S, Vanneman R, National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. India human development survey (IHDS). Interuniversity Consortium Political Social Res [distributor]. 2005;2018–08–08. 10.3886/ICPSR22626.v12.

- 35.Desai S, Vanneman R, National Council of Applied Economic Research. India human development Survey-II (IHDS-II). Interuniversity Consortium Political Social Res. 2012. 10.3886/ICPSR36151.v6. [distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shane D, Burns LE, Best S, Amoatey. Exploring the Intersectionality of Place and Gender Among Older Adults in Ghana: An Examination of Women’s Disability Disadvantage, Innovation in Aging. 2024;8(4):igad134. 10.1093/geroni/igad134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Olivares DEV, Chambi FRV, Chañi EMM, Craig WJ, Pacheco SOS, Pacheco FJ. Risk factors for chronic diseases and Multimorbidity in a primary care context of central Argentina: a web-based interactive and cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017; 10.3390/ijerph14030251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krishnan MN, Zachariah G, Venugopal K, Mohanan PP, Harikrishnan S, Sanjay G, Jeyaseelan L, Thankappan KR. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and its risk factors in Kerala, South India: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kowal P, Williams S, Jiang Y. Aging, health, and chronic conditions in China and India: results from the multinational study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). In: Aging in Asia: findings from new and emerging data initiatives. 2012.

- 40.Arber S, Cooper H. Gender differences in health in later life: the new paradox? Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonough P, Walters V, Strohschein L. Chronic stress and the social patterning of women’s health in Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54(5):767– 82. 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00108-3. PMID: 11999492. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Sharma SK, Nambiar D, Ghosh A. Sex differences in non-communicable disease Multimorbidity among adults aged 45 years or older in India. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e067994. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067994. PMID: 36972971; PMCID: PMC10069553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaz M, Kalliath PC, Mani. Nagaraja, Deepika, Kiran, Pretesh Rohan, Garady, Lavanya, Kasthuri, Arvind, Sambashivaiah, Sucharita. Social and Cultural Insights into Healthy Aging: A Qualitative Study from the South Indian City of Bengaluru, India. Indian Journal of Public Health. Jan–Mar 2024;68(1):31–37. 10.4103/ijph.ijph_846_23 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Gorman BK, Read JG. Gender disparities in adult health: an examination of three measures of morbidity. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD, Women KLD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:836–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agarwal A, Lubet A, Mitgang E, Mohanty S, Bloom DE. Population Aging in India: Facts, Issues, and Options. IZA Discussion Paper. 2016;10162. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=283421210.2139/ssrn.2834212

- 47.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perkins JM, Lee HY, James KS, Juhwan OH, Krishna A, Heo J, Lee JK, Subramanian SV. Marital status, widowhood duration, gender and health outcomes: a cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeon GS, Choi K, Cho SI. Impact of living alone on depressive symptoms in older Korean widows. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlassoff C. Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:47–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sebastian D, Sekher TV. Abuse and neglect of elderly in Indian families: findings of elder abuse screening test in Kerala. J Indian Acad Geriatr. 2010;2:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shankardass MK, Rajan SI Abuse and neglect of the elderly in India. Springer., Smith RS. (1999). Fraud and financial abuse of older persons. Australian Institute of Criminology. 2018;132.

- 53.ISEC, UNFPA, & IEG. Older women in India: economic, social and health concerns. India: New Delhi; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya., Jain K, Multi-Morbidity. Functional limitations, and Self-Rated health among older adults in India: Cross-Sectional analysis of LASI pilot survey, 2010. SAGE Open. 2015;5(1). 10.1177/2158244015571640.

- 55.Basu S, King AC. Disability and chronic disease among older adults in India: detecting vulnerable populations through the WHO SAGE study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1620–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Subramanian SV, Corsi DJ, Subramanyam MA, Smith GD. Jumping the gun: the problematic discourse on socioeconomic status and cardiovascular health in India. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1410–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhan N, Millett C, Subramanian SV, Dias A, Alam D, Williams J, Dhillon PK. Socioeconomic patterning of chronic conditions and behavioral risk factors in rural South Asia: a multisite cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health. 2017;62:1019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geldsetzer P, Manne-Goehler J, Theilmann M, Davies JI, Awasthi A, Vollmer S, Jaacks LM, Barnighausen T, Atun R. Diabetes and hypertension in India: a nationally representative study of 1.3 million adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talukdar B. Prevalence of Multimorbidity (chronic NCDS) and associated determinants among elderly in India. Demogr India. 2017;69–76.

- 60.Mini GK, Thankappan KR, Pattern TKR. Pattern, correlates and implications of noncommunicable disease Multimorbidity among older adults in selected Indian States: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Jana A, Chattopadhyay A. Prevalence and potential determinants of chronic disease among elderly in India: Rural–urban perspectives. PLoS One. 2022;11;17(3):e0264937. 10.1371/journal.pone.0264937. PMID: 35275937; PMCID: PMC8916671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Dey S, Nambiar D, Lakshmi JK, Sheikh K, Reddy KS. Health of the Elderly in India: Challenges of Access and Affordability. Aging in Asia: Findings From New and Emerging Data Initiatives. National Academies Press (US), (2012); Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109208/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [PubMed]

- 63.Agrawal S. Effect of living arrangement on the health status of elderly in India: findings from a National cross sectional survey. Asian Popul Stud. 2012;8:87–101. - PMC – PubMed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samanta T, Chen F, Vanneman R. Living arrangements and health of older adults in India. The journals of gerontology. Ser B. 2015;70:937–47. 10.1093/geronb/gbu164. - DOI – PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu F, Guo Y, Chatterji S, Zheng Y, Naidoo N, Jiang Y, Biritwum R, Yawson A, Minicuci N, Salinas-Rodriguez A, Manrique-Espinoza B, Maximova T, Peltzer K, Phaswanamafuya N, Snodgrass JJ, Thiele E, Ng N, Kowal P. Common risk factors for chronic noncommunicable diseases among older adults in China, Ghana, Mexico, India, Russia and South Africa: the study on global aging and adult health (SAGE) wave 1. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ICMR, & PHFI India: health of the Nation’s States: the India state-level disease burden initiative. New Delhi, India, (2017).

- 67.Gupta B, Johnson NW, Kumar N. Global epidemiology of head and neck cancers: A continuing challenge. Oncology. 2016;91:13–23. 10.1159/000446117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rani M, Bonu S, Jha P, Nguyen SN, Jamjoum L. Tobacco use in India: prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a National cross sectional household survey. Tob Control. 2003;12:e4–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhan N, Karan A, Srivastava S, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV, Millet C. Have socioeconomic inequalities in tobacco use in India increased over time? Trends from the National sample surveys (2000–2012). Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:1711–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anchala R, Kannuri NK, Pant H, Khan H, Franco OH, Di Angelantonio E, Prabhakaran D. Hypertension in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar R, Singh MC, Singh MC, Ahlawat SK, Thakur JS, Srivastava A, Sharma MK, Malhotra P, Bali HK, Kumari S. Urbanization and coronary heart disease: a study of urban–rural differences in Northern India. Indian Heart J. 2006;58:126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reddy SK, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ingle GK, Nath A. Geriatric health in India: concerns and solutions. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:214–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DGHS. National programme for prevention and control of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stroke. India: NPCDCS. New Delhi; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith KV, Goldman N. Measuring health status: self-, interviewer, and physician reports of overall health. J Aging Health. 2011;23:242–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, Pasanen M, Urponen H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:517–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.