Abstract

Spinal fusion is considered today as the last treatment option for different spinal conditions, such as degenerative and infectious illnesses. It consists of fusing two or more vertebrae to obtain reinforcement/fixation based on several methods used to sustain osteosynthesis and grafting, such as cage insertion in the intervertebral space, which provides an important level of mechanical stability, impacting only a low amount of the natural biomechanics of the spine and facilitating the implant bony ingrowth. This review paper first explores the background of intervertebral fusion, emphasizing medical applications and material properties of interbody fusion cages. It then provides a brief historical overview and discusses antibacterial efficacy-related issues. Additionally, some of the most met-in-clinical practice lumbar interbody cages with a detailed description of their geometry and examples of clinical trials performed worldwide are provided. The biomaterials used in lumbar cage manufacture are comprehensively described. In the last part of this review paper, special attention is devoted to prospective biomaterials and coatings for spine fusion cages. Firstly, the rationale for using Mg-based alloys or high osteogenic polycaprolactone as biodegradable and bioresorbable alternatives in the spinal cage industry, addressing the clinical limitations of traditional Ti alloys and polyether ether ketone, is provided. Then, a more conservative approach, focusing on the use of bioactive or antibacterial coatings on the already certified biomaterials, is presented as a second alternative to the existing products on the market. Relevant literature studies are reviewed, and the osteointegrative, bioactive, or antibacterial character of the coatings is explained. Finally, our review identifies current clinical limitations and offers future perspectives that will provide better bioactive solutions, improving the existing biomaterials.

Keywords: Spinal fusion, Clinical trials, Biodegradable cages, Bioactive solutions, Mg-based alloys, High osteogenic polycaprolactone

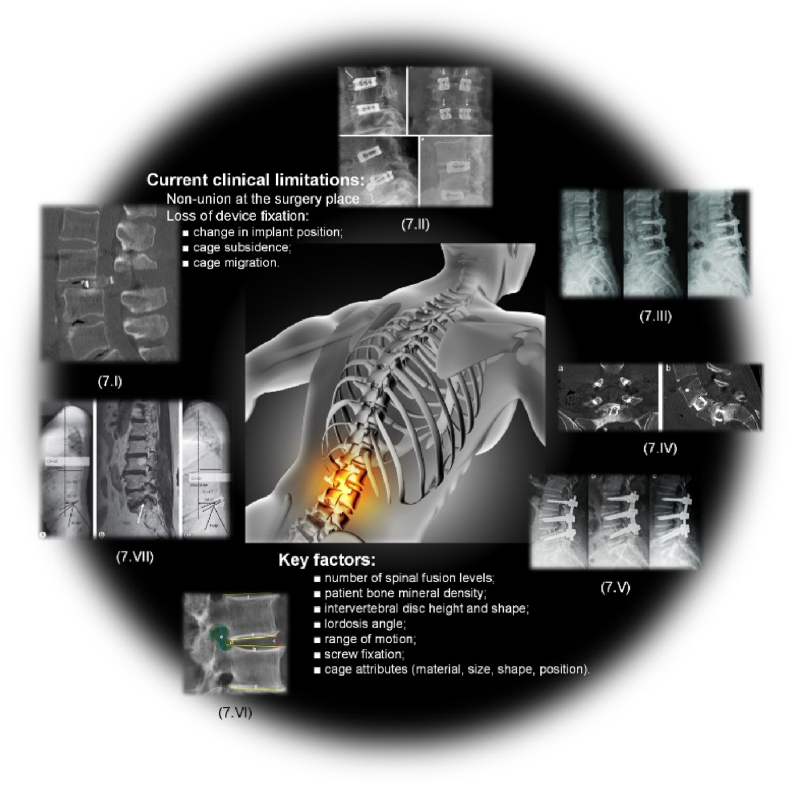

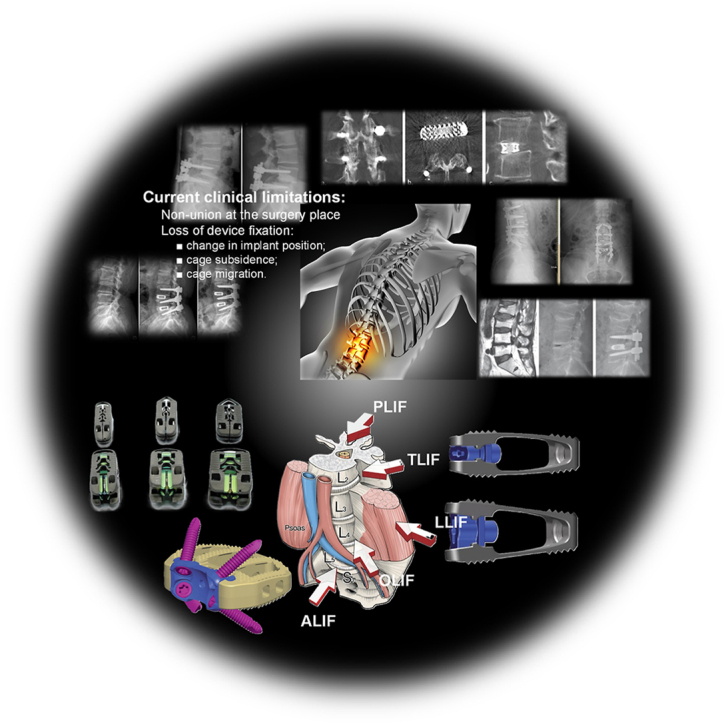

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Medical applications and materials used for interbody fusion cages.

-

•

Surgical approach for lumbar fusion cage insertion.

-

•

Overview of lumbar fusion cages in clinical practice.

-

•

Biomaterials used, mechanical and biological matching, bioactive solutions.

-

•

Prospective biomaterials and coatings for enhanced spine fusion cages.

1. Introduction

The main scope of this review paper is to present innovative bioactive and high osteogenic solutions for interbody spinal cage manufacture that could be further developed, adopted, or improved. Nowadays, an increased awareness regarding spinal conditions in the framework of a continuously aging population has been identified, so spinal fusion remains one of the principal research topics worldwide. The paper will present some medical applications of interbody spinal cages, a historical background, and the most used types of material employed in commercial products. Then, the potential of prospective bioactive materials will be detailed with examples of in vitro or in vivo studies extracted from the literature, and solutions such as complex coatings will be offered to underline their efficiency in improving the osteointegrative, bioactive, or antibacterial behavior of the spinal cages. In the end, clinical limitations of the products available on the market and future perspectives will be presented. The review can be divided into two essential parts as follows: the first one consists of a clinical investigation that includes the most used in practice commercial cages with detailed analyses regarding their geometry, materials, and medical outcomes, while the second part is dedicated to biomaterials. Initially, the traditional materials are presented with devoted attention to their mechanical and biological properties. The innovative and bioactive solutions, which can be applied shortly, are sustained with a detailed literature investigation. Last but not least, the conservative approach of developing coatings for traditional materials is presented by explaining the importance of bioactive or antibacterial properties.

1.1. Medical applications and materials used for interbody fusion cages

Nowadays, spinal degenerative condition is considered a main priority, exhibiting an incidence worldwide higher than 50 % [[1], [2], [3]]. Spine degeneration usually deteriorates the anatomical structure and biomechanics of the vertebrae, surrounding soft tissue, nerves, and, last but not least, the intervertebral discs. These modifications are considered of utmost importance because they have an influence on loading patterns, range of movements, and tolerance to traumatic situations, which usually implies a higher mechanical load application due to an impaired mechanical activity of the spine. Some of the most important degenerative pathologies that lead to spine damage are disc degeneration and rupture, spondylosis – degenerative disease, spondylitis – inflammatory or infections in the bone or soft tissue, scoliosis and other congenital spine conditions with progressive deformity, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis – degenerative or traumatic vertebrae slippage [4]. Intervertebral Disc (IVD) degeneration is one of the most common illnesses and can include the following conditions: a decrease in disc height, disc bulges, disc desiccation, disc herniations, and bone spurs formation [5,6]. A study developed by Brinjikji et al. [5] investigated the prevalence of disk degeneration in pain-free individuals and patients with back pain, based on a systematic literature review of Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) images published in English. They observed that in young asymptomatic patients, IVD degeneration occurred in 37 % of cases, while in individuals aged 80, this rate was approximately 96 %. In 20-year-old individuals, the prevalence of disc bulge was 30 %, disc protrusion 29 %, and annular fissure 19 %. In contrast, older patients show higher prevalence rates: disk bulge 84 %, disk protrusion 43 %, and annular fissure 29 %. The authors concluded that spine degeneration could be present even if a patient exhibits asymptomatic features. It is well known that, due to current lifestyle factors, diseases once considered associated with advanced age and part of the normal aging process are occurring much more frequently in the younger population. As previously mentioned, spinal fusion surgery is also performed to correct the spine shape. Weiss et al. [7] found that spinal fusion surgery is recommended when the spine curvature exceeds 40–45°. The authors noticed in the literature that the old biomaterials used for implants generated important side effects during patient life, such as loss of normal spinal function, neurological damage, higher strain on un-fused vertebrae, inflammatory effects, infections due to the implant contamination, curvature progression, and increased torso deformity. Spinal fusion is an effective surgical technique for complex clinical situations to resolve issues ranging from deformity correction and biomechanical stability to microbial resistance. A recent study developed by Zhao et al. [8] proved that in the case of a 10-year-old boy exhibiting an advanced kyphosis with a thoracic angle of 113° associated with Gaucher disease, a posterior spinal fusion was obtained based on pedicle screw fixation and Ponte osteotomy. By analyzing the medical images of the patient, the authors concluded after a 2-year follow-up period that posterior spinal fusion without an anterior spinal release was a good choice to treat the boy's advanced deformity. Another reason to use spinal fusion consists of spinal instability and weakness as a result of severe arthritis. Crawford et al. [9] investigated the lumbar fusion outcomes in the case of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Their study was based on two groups of patients with an average age of about 65 years old, including arthritis and non-arthritis patients. They noticed an increased level of surgery complications, wound infections, and non-union in the case of the arthritis group. The main conclusion of this study was that about 74 % of the patients exhibited good results, but the lumbar fusion remains still a challenge because, in some cases, it can be accompanied by serious side effects related to immunosuppression treatment of arthritis.

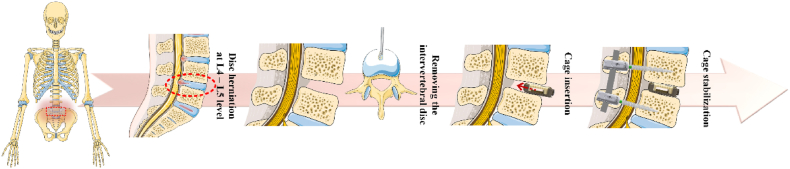

As an overall finding, an important purpose of spinal fusion surgery is nerve root decompression, which is sustained by the IVD anatomical height in a direct correlation with a complete bone fusion achievement [10]. Nowadays, the gold standard is represented by autogenous iliac graft [11,12], but due to the limited quantity of tissue and complications related to donor-site morbidity, this method cannot be applied as a general rule. Another solution consists of allogenic bone graft use, but unfortunately, it is often accompanied by side effects such as disease transmission and graft rejection due to the patient's immune response [13,14]. The use of interbody fusion cages seems to be a viable choice, but in some cases, vertebrae fusion cannot be achieved due to cage loosening and other problems, which occur in 5–35 % of the patients [10]. Consequently, choosing an adequate cage does not guarantee an increased rate of success [15]. Zhang et al. [10] established 3 modalities of bone cage enhancement dedicated to better bone fusion. First and foremost, the cage must be designed to support natural bone ingrowth. Next, the biomaterials should be selected based on their close alignment with the physical and mechanical properties of the human bone. Lastly, secondary post-processing steps, such as applying coatings to the cage, can enhance the biocompatibility and bioactivity of the implant. Fig. 1 presents an example of an anterior lumbar interbody fusion procedure to treat disc herniation based on intervertebral cage insertion between the L4-L5 spinal level. Other authors such as Warburton et al. [16] and Verma et al. [17] considered that an adequate bone substituent must have a certain value of mechanical strength almost equal to that of the human bone, a high biocompatibility correlated with a good bone induction, and a suitable ratio between its performance and final price. The most used materials for interbody fusion cages can be classified as metallic or non-metallic, permanent or temporary, and inert or bioactive. Commercial devices with European Certification (CE) or Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval are typically made from medical-grade titanium (Ti) alloys and polyether ether ketone (PEEK). Unfortunately, these types of biomaterials are characterized by important drawbacks such as impaired radiographical opacity and stress shielding that occur in the case of Ti alloy cages due to an important mismatch between mechanical properties compared to those of the human bone, and in both cases, it can be mentioned the inertia of the materials, which hinder their active participation to the bone remodeling process. In addition, inflammatory responses can also occur in both cases [18]. To overcome the limitations of the aforementioned commercial devices, ongoing research and development of bioabsorbable materials, including biocompatible polymers and bioactive metals like magnesium and zinc, are essential. Also, three-dimensional (3D) porous implants can be considered a good alternative because even if they are made of inert materials, the pore presence will enhance bone ingrowth, blood and nutrient circulation, and the insertion of biological materials directly connected to bone regeneration. Biocompatible coatings can be applied alongside drugs such as strontium ranelate (SRR) or simvastatin (SIM) to support implant osteointegration in osteoporotic patients. Additionally, the combination of Epidermal Growth Factor and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), which regulates the expression of osteogenic genes and promotes interbody fusion, should also be considered [19].

Fig. 1.

Exemplification of anterior lumbar interbody fusion surgical procedure consisting of an intervertebral cage insertion between spinal levels. This Figure was generated using images assembled from Servier Medical Art, which are licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://smart.servier.com, accessed on January 23, 2025).

It can be concluded that interbody cages are an important alternative to the full-biological solutions in intervertebral fusion surgery. However, today, many models of fusion cages exhibit a hollow center that is filled with bone grafts to improve bone fusion. As stated before, the grafts could be autogenic, allogenic, or synthetic. The surgeons could use a Demineralized Bone Matrix (DBM), which consists of an allograft collected from the patient iliac crest and combined with calcium phosphates. DBM is obtained in powder form with a given carrier as a graft extender. Another bioactive solution could be achieved by replacing DBM with ceramics and Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2). In clinical practice, inert fusion cages are combined with orthobiologics to increase the natural osteogenesis that occurs after cage implantation. However, it is important to emphasize the need for ongoing research into innovative materials to mitigate the common risks associated with inert implants.

1.2. History of lumbar interbody fusion surgery

To fully understand the current needs and challenges in developing new and innovative interbody fusion cages, it is essential to examine the history of lumbar interbody fusion surgery and the prevalence of spinal infections. The new biomaterials considered for spinal cage manufacturing must facilitate effective osteointegration and protect against various infections.

The first surgeon who performed a spinal fusion to treat a dislocated fracture between the C6 and C7 vertebra chose a silver wire that was wrapped around the spine and used a posterior approach in 1891 [20]. After that, the posterior approach was applied by Hibbs [21] and Albee [22], who used a bridge created from patients’ bones to fix the negative effects of posterolateral spondylosis. Classical Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF) was introduced in 1994, and later, it was modified by Cloward [23,24] and applied to more than 300 patients. He noticed a higher fusion rate when he used a partial bilateral laminectomy combined with a full facetectomy. The surgeon entirely removed the damaged IVD and both endplates by a posterior surgical procedure and used to fill the obtained void with bone grafts collected from the patient iliac crest. During the time, many studies [[25], [26], [27], [28]] described case reports in which autologous grafts from the fibula or iliac crest and allografts were involved to fix spinal problems, but as described in Section 1.1, the risks mentioned above were noticed. Couture and Branch [29] found that pseudarthrosis developed in cases where bone grafts were used alone, without association with other implants, and this was directly related to graft collapse. Between 1970 and 1980, a supplementary stabilization procedure was proposed based on a plate interconnected with pedicular screws or in combination with the so-called Harrington rod [30]. Steffee and Sitkowski [31] proved that better fusion rates and higher stability were achieved when the interbody fusion procedure was combined with pedicle screw fixation. Blume [32] applied the posterior unilateral transforaminal approach, Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF) to solve lumbar interbody spondylosis. The TLIF procedure was adapted and improved later by Harms [33]. He used one midline posterior incision to perform a posterior unilateral TLIF based on an anterior interbody fusion procedure using classical pedicle implants. In Ref. [34], morselized autologous bone grafts were inserted around a screw-rod ensemble to improve the spinal fusion. Today, in order to obtain a proper osteointegration process for the spinal cages, morselized autologous bone grafts are used to fill the voids between the intervertebral space and cages. Through osteointegration, the cages will offer good nerve decompression and stability to the affected spine segment, but it is usually conditioned to a certain quality and physical properties of the implant surface.

In addition, systematic reviews and important studies were conducted to provide information regarding the best treatment choice for different spine diseases. As an overall finding, spinal fusion procedure is commonly accepted to induce patient relief and have good outcomes. The so-called Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) developed by Weinstein et al. [35] is considered today one of the most comprehensive and interesting studies. It was conducted as a random clinical trial, including patients who supported spine surgery between March 2000 and November 2004, coming from 13 multidisciplinary spine clinics. There were chosen 501 candidates, who were 42 years old on average, of which 42 % were women. Based on those results, other studies were conducted and proved that even after 8 years of follow-up, the spinal fusion intervention was beneficial and suitable to be applied to patients with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis [36,37]. In the last decades, an increasing number of spinal fusion procedures have been reported in Europe and the USA. Provaggi et al. [38] found an increased number of spinal fusions of about 63 % starting from 2005 and ending in 2015 in the United Kingdom, while Grotle et al. [39] noticed an increased number of spinal fusions in Norway between 1999 and 2013. Beyer et al. [40] conducted a study in Köln, Germany, in which they considered patients treated for vertebral osteomyelitis (52 patients) and degenerative spondylolisthesis (48 patients) based on one- or two-stage fusion of the ill spine segments. They found similar outcomes related to patients and concluded that spinal fusion is recommended in many cases to alleviate the patient's pain. Regarding other continents, a very interesting analysis was performed by Kim et al. [41], who noticed after a detailed comparison between Asia (South Korea and Japan) and the USA that many more spine surgical interventions were performed in the last case. This fact was attributed to the lifestyle of the investigated population, and it was concluded that Asian people exhibit their particularities and have healthier behavior. A comprehensive study was conducted by Deyo et al. [42], who observed an increased number of spinal fusions in the USA by 77 % between 1996 and 2004. After that, Rajaee et al. [43] noticed an increase in spinal fusion application by about 137 %, starting in 1998 and ending in 2008. Seven million cases were studied by Sheikh et al. [44]. The authors observed a steady increase in spine fusion intervention, with a rise of 118 %, compared to decompression, a non-spinal procedure, across the North American continent from 1998 to 2014.

Today, minimally invasive surgical techniques are applied in lumbar interbody fusion surgery. Traditionally, this procedure was conducted as a PLIF based on a posterior approach combined with an extended facet joint resection. Then, a cage made of different biocompatible materials was inserted after the nerve roots and dura mater were correctly repositioned. The dura mater is the outermost and toughest layer of the three membranes (meninges) that surround and protect the spinal cord. Another method that was applied in practice is TLIF, which allows the surgeon to use the space between the dura mater and nerve roots through a posterior approach. The Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF) was considered a safe and less traumatic surgical intervention in comparison with PLIF and TLIF because it allows direct visualization of the IVDs, permitting also to perform complete discectomy and introduction of a large interbody cage that improves the patient's position with a better sagittal alignment. In addition, ALIF was usually linked to a higher fusion rate and posterior structure preservation [20]. Another procedure met in practice is the Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF) that is associated with minimum blood loss, soft tissue damage, and shorter hospitalization time. It is also practiced in revision cases and usually restores foraminal height and central canal surface [45,46]. The minimally invasive approaches performed through the lateral anterior corridors include Direct Lateral Interbody Fusion (DLIF) and Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion (OLIF) [47] and, in most cases, minimize the invasiveness grade of the spine and the deterioration of the healthy tissue [48]. The expandable lumbar interbody cages can increase the lordotic angle and the space between IVDs compared to the classical static cages, which makes them widely used [49]. Also, supplementary, the controlled expansion of the medical implant keeps the iatrogenic endplates undamaged, and these devices show a larger footprint. However, despite the advantages described above, the literature has shown that both static and expandable cages yield similar fusion outcomes and maintain favorable sagittal parameters [[50], [51], [52], [53], [54]]. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the main surgical access' impact on fusion effects underlying the advantages and drawbacks associated with each surgical technique [[55], [56], [57], [58]], [[59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75]].

Table 1.

Indications, contraindications, possible risks, and surgery steps for main lumbar spinal surgical accesses.

| Surgical procedure | Indications | Possible risks and complications | Contraindications | Surgery steps | Average fusion rates reported in the literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF) | Permits access to the anterior and posterior columns in a single step and complete visualization of the nerves with circumferential decompression. It is indicated for pseudoarthrosis, spinal stenosis, disc hernia, spondylolisthesis, and disc instability [55,56] | Deterioration of paravertebral muscle, long time of muscular contraction, retraction of nerves to permit the insertion into intervertebral space, epidural bleeding, fibrosis. By retracting the dura mater, durotomy could occur [57,58] | Arachnoiditis, infections [55] | Laminectomy, medial facetectomy, annulotomy, discectomy, cage insertion [61] | 71 % ÷ 96 % [[67], [68], [69]] |

| Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF) | Provides access to the intervertebral disc space through a considerably more lateral approach than PLIF. It reduces nerve retraction and is associated with a low risk of nerve damage and dural tear. Maintains biomechanical stability and the interlaminar surface and facet joints. It can be used as a Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) [59,60]. Indications: the same as PLIF | Infection, nerve injury, blood loss, paraspinal iatrogenic injury [61] | Epidural scarring, infection, osteoporosis, arachnoiditis, conjoined nerves [61] | Discectomy, endplate preparation, cage insertion [61] | 82 % ÷ 98 % [[70], [71], [72]] |

| Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF) | It can reduce the soft tissue deterioration’ area and blood loss, as well as minimize the hospitalization time for each patient. Usually, a lateral incision is performed by dissecting the blunt and abdominal muscles. Maximum attention has to be given after the retroperitoneum is reached so as not to damage the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, iliac inguinal nerve, subiliac nerve, and intercostal nerve [62]. Indications: degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, revisions, correction of coronal and sagittal spine deformity, restoration of foraminal height and central canal height [45] | Damage of the lumbar plexus, psoas, and organs. Tight pain, operative groin, paresthesia, and hip flexion weakness are listed as possible side effects or risks [63] | Adhesive retroperitoneal cases associated with a history of infection, radiation, or another surgery. A main contraindication consists of surgeries made at L5-S1 level [61] | Discectomy and cage insertion made under fluoroscopic guidance [61] | 80 % ÷ 90 % [68,73] |

| Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF) | Less traumatic surgery compared to PLIF. Improved biomechanics due to larger cage insertion. Preserves the back muscles and ligaments and is characterized by higher fusion rates. ALIF is suitable for the L5-S1 level. Indications: degenerative disc disease, sagittal plane deformities, postoperative spondylodiscitis, and pseudoarthrosis [61] | Superior hypogastric plexus deterioration could lead to retrograde ejaculation [64]. Also, postoperative hernia could occur. ALIF is associated with risks such as ureters' and abdominal organs' damage, and post-surgical hernias. In some cases, large vessel deterioration could be present [65] | Other abdominal surgery, obesity, previous radiation therapy, or important aortic disease [61] | Discectomy and large cage insertion [61] | 94 % ÷ 98 % [67,74] |

| Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion (OLIF) | This surgical procedure was developed as a response to overcome the LLIF drawbacks. It provides access to the discs placed between the psoas muscle and abdominal blood vessels with a low risk of lumbar plexus and muscle damage. The follow of the nerves is unnecessary, and thigh pain or postoperative groin seldom occurs. Indications: spondylolisthesis, pseudoarthrosis from L2-L3 to L5-S1, discitis, degenerative disc disease [61] | Large vessel damage [66], sympathetic deterioration | Infection, radiation therapy, and retroperitoneal surgery [61] | Classic discectomy and cage insertion [61] | 92 % ÷ 98 % [75,76] |

An important problem that is met in medical practice consists of infections associated with orthopedic surgical interventions [77]. A study performed by Darouiche [78] provides a risk of infection between 2 % and 5 % in this domain, while others [79,80] stated that many spinal infections are associated with Staphylococcus epidermis and Staphylococcus aureus. Unfortunately, the number of patients exhibiting negative symptoms related to spondylitis, which can be defined as vertebra osteomyelitis, and spondylodiscitis, an infection of the IVDs, has increased lately [81]. In addition, a mortality rate of about 23 % was registered in the case of spondylodiscitis [[82], [83], [84]], making the spine surgery domain very challenging from a social and economic point of view. Some studies [[85], [86], [87]] established that infections occurred in 3.4–8.5 % of spinal surgeries when implants are used and only in 1 % of cases when no external hardware is involved. It should be noted that infections are not the only drawback associated with spinal cages, as they are also directly linked to the development of pseudoarthrosis, with a risk of 30 % [88]. Sometimes, when surgery is performed, even if everything is clean in the operating room, pathogens on the patient's mucous membranes or skin could populate the spinal cage or other implants and lead to multispecies biofilm formation. This condition is considered in the medical sciences as a life-threatening situation because stronger antibiotics and drugs are required to effectively target and eliminate biofilm-associated infection [89]. Even so, vascularization and implant dislocation or loosening are common side effects of infections in the spinal region [[90], [91], [92]]. Unfortunately, the current strategies to address spinal infections associated with implants are limited [93], with fusion rates of approximately 70 % reported for patients with infections [94,95].

Rapid technological advancements must be considered in the development of advanced and multifunctional spinal cage materials, driven by the complications associated with permanent and inert implants. In the authors' opinion, an ideal interbody fusion cage should be biodegradable or bioresorbable to mitigate the risk of biofilm formation, which increases proportionally with the duration the implant remains in the human body. Additionally, the material should possess intrinsic antibacterial properties to prevent infections and exhibit bioactivity to promote new bone formation, ensuring effective healing and stability of the affected segment. Furthermore, the material should be designed to closely match the mechanical properties of bone, enhancing integration and long-term outcomes.

2. Overview of different lumbar fusion cages in clinical applications

This section will focus on the various lumbar fusion cages currently used in clinical applications worldwide. Some studies [43,44] evidenced that in 2008, one of the most met-in-practice diagnoses was that of lumbar degenerative IVD disease, accounting for about 14 % of the total number of surgeries in the United States of America.

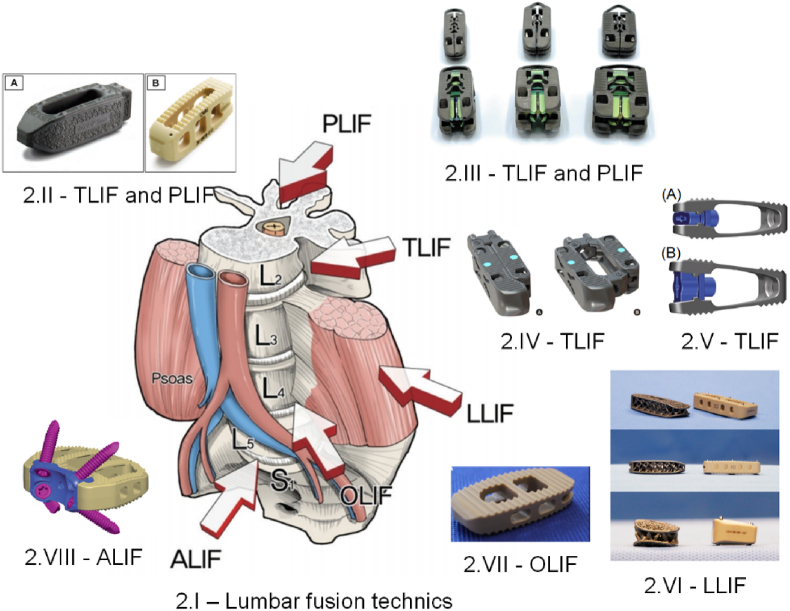

Fig. 2 shows the main types of surgical interventions in the lumbar zone associated with examples of commercial interbody fusion cages made by different producers, as reported in the literature.

Fig. 2.

Examples of commercial fusion cages associated with different surgical interventions. (2.I) Main lumbar interbody fusion surgical approaches [48] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0); (2.II) CTL Amedica, Dallas, TX, USA fusion cages: (A) TLIF Si3N4 Valeo™ OL, (B) PLIF PEEK Phantom™ [52] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0); (2.III) Acellus, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA TiHawk7, TiHawk9, and TiHawk11 (from left to right) [96] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0); (2.IV) Amplify Surgical, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA Dual-X TLIF cage [97] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0); (2.V) Signus Medizintechnik GmbH, Alzenau, Germany TLIF Vertaconnect [98] (Figure is licensed under CC BY 4.0); (2.VI) NuVasive, Globus Medical, San Diego, CA, USA 3D Ti Modulus and CoRoent XL PEEK [99] (Figure is licensed under CC BY 4.0); (2.VII) Sanatmetal, Eger, Hungary OLIF PEEK EMERALD™ cage [53] (Figure is licensed under CC BY 4.0); (VIII) DePuy Synthes Spine, PA, USA PEEK SynFix® stand-alone cage [54] (Figure is licensed under CC BY 4.0).

2.1. Permanent lumbar interbody fusion cages

Attention will be focused on permanent lumbar fusion cages currently used in clinical studies and hospitals worldwide, emphasizing implant geometry and biomaterials, the number of treated patients, and key observations related to the investigated models and surgical techniques. Finally, the most current and advanced bioactive solutions will be highlighted at the end of the section.

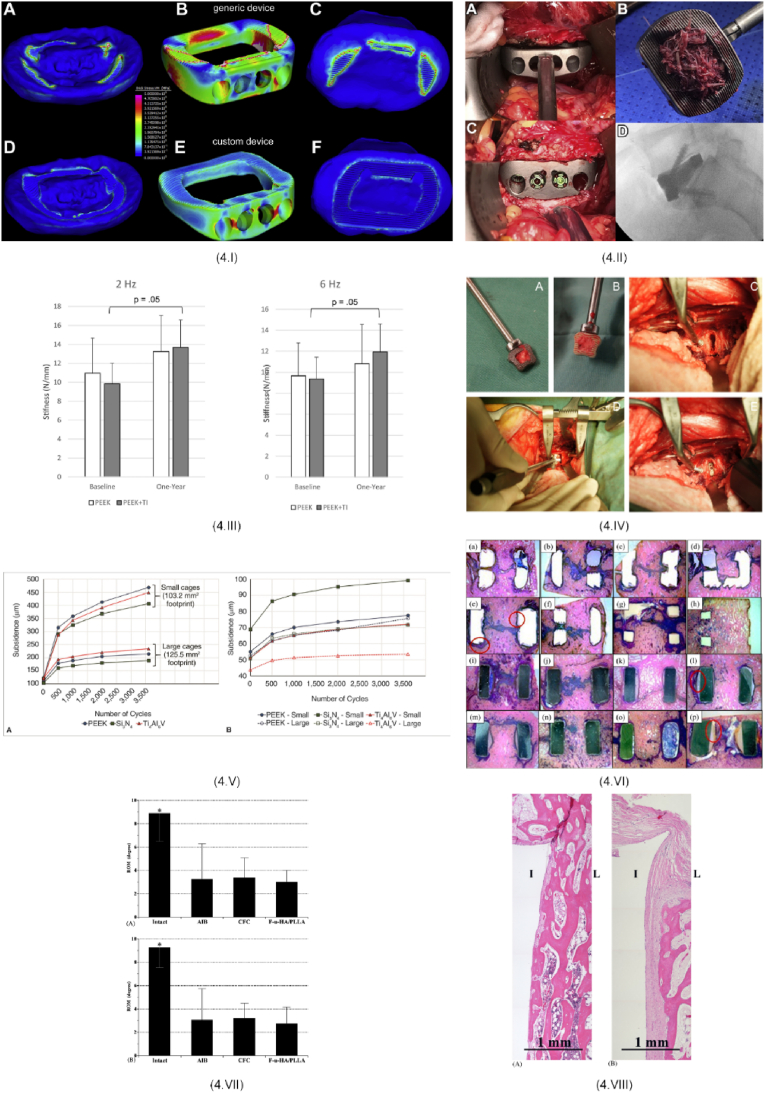

One of the most used worldwide spinal interbody cages is the FlareHawk® produced by a private company called Accelus. They adopted a minimally invasive surgery based on the FlareHawk® system that was used in Europe (Italy and Portugal) as well as in Taiwan and Colombia. FlareHawk® 7 was reported in Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland, while FlareHawk® 9 was used in Argentina, Qatar, Australia, and Chile. It must be underlined that FlareHawk® Expandable Lumbar Interbody Fusion Devices received FDA 510(k) clearance and CE mark certification in 2021 [96]. The literature revealed that about 15,000 devices have been involved in US patient treatments, while worldwide, 17,000 implants for spinal fusion were reported. The FlareHawk® Interbody Fusion System was indicated in most medical approaches for spinal fusion surgeries with autogenous or allogeneic bone grafts on skeletally mature patients suffering from Degenerative Disc Diseases (DDD) [100]. Cheng et al. [101] investigated the feasibility assessment of expandable interbody cages by performing a retrospective analysis on 7 patients based on CT images to evaluate the interbody fusion and the modalities of cage accommodation in a direct relationship with the endplates within the intervertebral space. They used FlareHawk® Integrity Implants (Palm Beach Gardens, FL), which consist of 2 parts made of PEEK that expand in two given directions, having an insert manufactured from Ti, to restore the patient lordosis. The authors noticed that their small case series analysis revealed a successful fusion process due to the good endplate-conforming interbody fusion cages. The adaptable geometry of the expandable cage was suitable for each patient's anatomy and proved compliance and conformity to the dimension of the intervertebral space. An anterior average implant deformation of 1.82 mm and posterior cage deformation of 1.41 mm were reported in combination with a suitable endplate concavity between 1.37 mm and 1.90 mm, which agrees with the literature. It was concluded that the analyzed expandable interbody fusion cage exhibited an adequate value of stiffness, which provides the necessary anterior column support by enhancing the arthrodesis. Coric et al. [102] retrospectively analyzed performance and safety regarding FlareHawk® expandable implants. There were selected 58 patients for the investigation related to the 1-year intervertebral fusion process and 45 patients with Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for back pain, or VAS leg pain with an average follow-up of 4.5 months. The surgeons reported that after 12 months, fusion rates ranging from 92 % to 96 % were achieved. An improvement of about 15 ± 19 points in ODI (100-point scale), 4 ± 3.4 points in VAS leg pain (100-point scale), and 3.4 ± 2.6 points in VAS back pain were noticed. The conclusion was that clinically important improvement considering the ODI and VAS scores was obtained in the case of 58 % (ODI), 76 % (VAS back pain), and 71 % (VAS leg pain). The authors considered that their study gave preliminary clinical evidence regarding the safety of FlareHawk® expandable devices and observed that both surgical procedures, PLIF and TLIF, were adequate. Tan et al. [103] analyzed the positive outcomes obtained after a Minimally Invasive (MIS-TLIF) procedure used to treat spondylolisthesis. A retrospective review was performed in the case of 13 patients. All these patients had a FlareHawk® cage for over 1 year. The mean average age was 61, of which about 62 % were female. After the surgical procedure was applied, the VAS back pain score improved from 7.0 ± 2.9 to 3.1 ± 3, the VAS leg pain decreased from 5.1 ± 3.0 to 1.1 ± 1.7, and the Five Dimensions (EQ5D) score improved from 0.37 ± 1.7 to 0.66 ± 0.23 postsurgical. The main conclusion of this study was that the FlareHawk® cage was a good choice to treat spine illness via the MIS-TLIF surgical approach because no side effects, such as cage migration or endplate damage, were reported. In addition, none of the patients required a second surgical intervention. In a very recent study, Zygogiannis et al. [104] investigated the lumbar spinal rahisynthesis based on PLIF by studying the medical documents retrospectively in the case of 58 patients in KAT General Hospital, Athens, Greece. The mean age of the patients was about 60 years old, and 22 patients were female. The follow-up time was set for 1 year. The surgeons used the FlareHawk® 9 implant. The patients' ODI index improved by a high amount in the case of 45 patients exhibiting a decrease from 48.6 preoperative to 23.1 postoperative (p value of 0.05), remains almost unchanged for 8 patients (mean preoperative value of 49.7; mean postoperative value of 48.1 (p value of 0.05)), and in the case of 5 patients, it worsened with an increased value from 50 to 54.2 (p value of 0.05). It was concluded that an improvement of lordosis, with an increase of 2 ± 0.4°, and a good fusion level were achieved, but a longer follow-up time is mandatory for a detailed analysis of the benefits and side effects. By analyzing the literature, it can be concluded that the FlareHawk® class of lumbar interbody fusion devices exhibit the possibility to enlarge in height and lordosis and in width, generating an improvement of sagittal parameters and disc height. Their larger footprint is usually linked to a reduced risk of cage subsidence, providing an adequate medium for bone fusion. In addition, it must also be mentioned that its unique design allows the conformity between the implant and the endplates, and its open architectural geometry permits the use of bone grafts that can enhance new bone apparition.

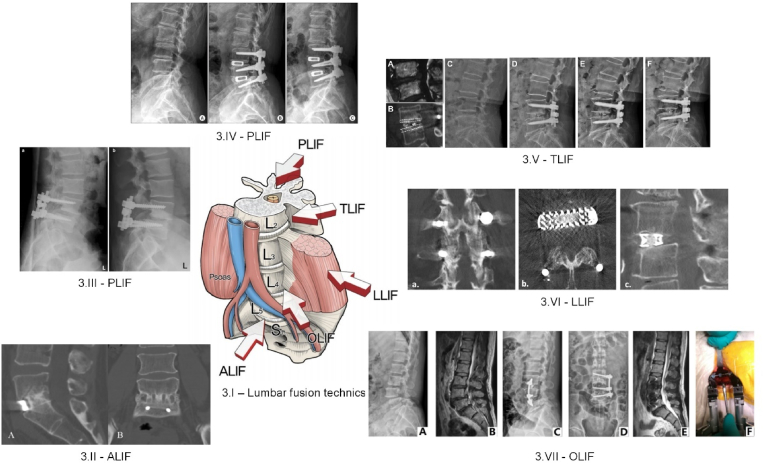

Another important interbody fusion cages used in clinical research are those made by NuVasive company. One can mention the 3D-printed porous or conventional threaded titanium Modulus cages, as well as the CoRoent type, which are manufactured from sPEEK or Ti alloys. The Modulus Interbody Fusion device is designed in a hollow cylindrical or similar geometrical shape with porous, fenestrated, or threaded features. It is made of Ti alloy, and it is advisable to be filled with bone graft to ensure a successful spinal bone fusion. The CoRoent thoracolumbar non-interfixated fusion cage is usually manufactured of either Ti alloy or PEEK-Optima and includes radiographic markers made of tantalum (Ta) or titanium (Ti). Regarding the interfixated implants, they are fabricated only from PEEK-Optima and are equipped with a canted coil lock mechanism (NiCoCrMo) and screws (medical Ti alloy grade). Segi et al. [99] investigated the effect of native endplate injury that occurred in the case of Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF) procedures. The authors have chosen to perform a retrospective study in Nagoya, Japan, including 32 patients with a mean age of about 74.1 ± 6.7, of which 22 were female. These patients have undergone posterior or anterior surgery combined with XLIF. Two types of implants were used as follows: 3D porous titanium (3DTi, Modulus, NuVasive) (11 patients) and sPEEK (CoRoent XL PEEK, NuVasive) (21 patients). The 3DTi cages were combined with a hydroxyapatite mass, which was inserted in their pores, while in the case of polymeric interbody fusion implants, grafting bone was involved. The 3DTi implant was used in the case of 25 levels since the sPEEK cage was applied for 38 levels. The local lordotic angles were preoperatively equal to 4.3° (3DTi) and 4.7° (sPEEK) (p = 0.90), and then after the implant insertion, these values were corrected to 12.3° (3DTi) and 9.1 (sPEEK) (p = 0.013). The authors [99] noted that the risk of side effects is associated with vertebral endplate concavity (VEC) or other endplate injuries. They found that, after three months postoperatively, none of the patients treated with 3DTi cages exhibited Vertebral Endplate Concavity (VEC) progression (VEC was present in 2 levels, or 0.8 %). In contrast, for the sPEEK cages, VEC progression occurred in 8 levels (21 %), with VEC present in 17 levels (45 %), overall (p = 0.002). The main conclusion of this study was that the 3DTi cages were superior to the polymeric implants and gave the patient an improved local correction, as well as less intraoperative VEC. Although a good prognosis was foreseen, the surgeons noticed that the long-term outcomes must be further investigated to estimate the bony fusion process and spinal alignment. Amini et al. [105] performed a retrospective study based on fusion assessment in standalone lateral lumbar interbody fusion by including two PEEK cage systems (XLIF – NuVasive, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA and COUGAR – DePuy Spine Inc., Raynham, MA, USA) and two 3D-printed Ti cages ((Modulus XLIF (NuVasive, Inc.) and Lateral Spine Truss System (4WEB Medical, Inc., Frisco, TX, USA)). A total number of 91 patients (136 levels) were studied, from which an early group consisting of 49 patients (72 levels) and a late group of 42 patients (64 levels) were admitted. The authors [105] underlined in their study that a main disadvantage of the PEEK consists of the so-called “PEEK-Halo effect” represented by a reduced osseointegration and a biofilm layer formation around the implant surface. In addition, new bone material usually occurs around the implant, facilitating the connection to the patient's vertebrae. Supplementary, they stated that the porous Ti cages are the most advanced, exhibiting an increased biocompatibility due to the fact that they are similar to the trabecular bone. To evaluate the outcomes of the surgical procedure, CT scans were performed at 8 months postoperative for the early group and at 19 months postoperative in the case of the late group. The early group bone fusion was higher in the case of the Ti group (95.8 %) in comparison with the PEEK group (62.5 %) (p = 0.002). For the patients included in the late group, no important differences (94.7 % - 3DTi cages; 80.0 % - PEEK cages (p = 0.258)) were reported. It was concluded that the 3D-printed Ti cages with porous geometry are the most adequate for spine bone fusion surgery due to their enhanced osteoconductivity. Velluto et al. [106] evaluated the fusion patterns obtained after lateral lumbar interbody fusion in the case of conventional and 3D-printed porous titanium cages. The authors used titanium threaded or 3D-printed porous titanium (XLIF Modulus NuVasive, San Diego, CA, USA). The porous implants were filled with synthetic bone from NuVasive AttraX Putty type. A total of 135 patients were included, from which 51 patients (Group A) were treated for degenerative spondylolisthesis with porous cages and 84 patients (Group B) with conventional threaded Ti cages. At 2 years post-surgery, the intervertebral bone bridges (BB) were noticed in 83 segments (94.31 %) in Group A, while for Group B they were present in 87 segments (88.7 %). If one considers also the zygapophyseal joints ankylotic degeneration criterium (ZJ Pathria) [107] grade I (Group A: 2 segments (2.27 %); Group B: 4 segments (4.08 %)), grade II (Group A: 5 segments (5.68 %); Group B: 6 segments (6.12 %)), and grade III denoted as posterior fusion (Group A: 81 segments (92.04 %); Group B: 88 segments (89.79 %)) were noticed (Fig. 3.VI). After analyzing these findings, the authors [107] concluded that the porous Ti cages are adequate for spine diseases by facilitating bone ingrowth and bridging space and offering increased stability and successful bone fusion. In the case of spinal interbody fusion devices produced by NuVasive company, it seems that better fusion rates and improved implant osteointegration were obtained for Ti cages. However, one must also mention that Ti, due to an important difference between its elasticity modulus and native vertebrae Young's modulus, can induce an unwanted effect, called stress shielding, which can generate secondary fractures at the implantation site and hinder bone fusion. Regarding the PEEK, as was underlined above, the Halo effect could lead to reduced new bone formation and infection apparition. Therefore, none of these solutions are ideal, but the literature has already demonstrated their promising and effective application in treating spinal disorders.

Fig. 3.

Medical images associated with different surgical interventions.(3.I) Main lumbar interbody fusion surgical approaches [48] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0); (3.II) CT scan image confirming a successful grade I fusion: (A) sagittal image, (B) coronal image based on ALIF insertion of DePuy Synthes Spine, PA, USA PEEK SynFix® stand-alone cage [122] (Reprinted from Ref. [122] Copyright (2025), with permission from Elsevier); (3.III) X-ray images of a young patient after a PLIF surgery using a Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA PLDLLA Hydrosob™ taken (a) at 1 day post-surgery, and (b) after 1 year post-surgery [145] (Figure is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0); (3.IV) Medical images of a patient with spinal stenosis taken before and after PLIF surgery based on Stryker, NJ, USA Titanium O.I.C® cage: (A) preoperative X-ray image evidencing a reduced disc height, (B) lateral view immediately after surgical procedure, (C) lateral view after 3 year post-surgery (Figure is licensed under CC BY 2.0) [140]; (3.V) Medical images of a patient with L4-L5 disc herniation that underwent TLIF surgery with Medtronic, Memphis, Tennessee, USA PEEK Capstone cage: (A) MRI image before surgery, (B) 1 year image evidenced solid fusion and cage subsidence, (C) preoperative upright medical image, (D) reconstruction after TLIF surgery, (E) 1 year image showing loss of disc height and segmental lordosis due to cage subsidence, (F) X-ray image at 33 months post-surgery [119] (Reprinted from Ref. [119] Copyright (2025), with permission from Elsevier); (3.VI) CT scan images presenting different views of a strong fusion (a) coronal view, (b) axial view, (c) sagittal view based on Nuvasive, San Diego, CA, USA Titanium XLIF Modulus cage [106] (Figure is licensed under CC BY 4.0); (3.VII) Medical images of a patient exhibiting grade I spondylolisthesis at L4-L5 level and disc herniation at L3-L4 level treated with Medtronic, Mineapolis, MN, USA Clydesdale Spinal System: (A) and (B) preoperative X-ray and MRI images, (C) anterior-posterior, (D) lateral X-ray and (E) sagittal MRI postoperative images, (F) intraoperative image [124] (Reprinted from Ref. [124] Copyright (2025), with permission from Elsevier).

CTL Amedica is a well-known company that produces Valeo® (Valeo® TL VBR Lumbar Spacer), a special type of implant made of a micro-composite ceramic based on silicon nitride (Si3N4) and endowed with a surface that has a similar structure to that of the cancellous bone. The spinal fusion cage includes a dense load-bearing component and a porous one in combination with an original surface texture. This is highly hydrophilic and is beneficial for protein and cell adhesion, being considered suitable for good implant osteointegration. The cage has a central cavity dedicated to autograft packing, bottom and top ridges to resist the implant migration process, threaded insertion characteristics, a tapered nose dedicated to the facile introduction, and windows, which offer good bone attachment, as well as good visibility of the implant during the surgical procedure [108]. Some literature studies reported successful clinical applications related to these silicon nitride implants. Youssef et al. [109] evaluated the outcomes of Amedica-TL fusion cages in the case of two patients. The first patient was a woman of 47 years old with lumbar spinal stenosis at L4-L5, while the second patient was a 77-year-old female with lumbar spinal stenosis L4-L5 and disc space collapse L4-L5. Both patients did not have osteoporosis. A TLIF procedure was applied. The 1-year follow-up was based on CT scans and dynamic X-rays and demonstrated solid bony fusion. The authors [109] concluded that this outcome was attributed to the material properties that promoted bone growth both on and through the cage. Calvert et al. [110] performed an original study based on 450 patients and 519 silicon nitride implants from four USA centers and compared their outcomes with those obtained in the case of other biomaterials for 1025 patients grouped in 26 cohorts worldwide. The analyzed surgical approaches were ALIF, TLIF, and PLIF, and the authors included two Si3N4 fusion cage generations from the Valeo® types. Different follow-up times between a minimum value of 11.4 ± 9.8 months and a maximum of 6.4 years were reported. In the case of ceramic implants, there was a higher improvement in the VAS pain scores with ΔVAS of 36.8 ± 35.4 points and good bony fusion. It was concluded that due to the fact that Si3N4 is a special material with increased osteoconductivity, good radiolucency, and bacteriostatic effect, it could be used successfully in lumbar fusion approaches, although they were associated with an increased number of complications that were linked to the fact that in this interesting retrospective study, there were also used old implant designs. McEntire et al. [111] made a study that considered the 2-year clinical and radiographic outcomes of a prospective analysis that compared the results obtained in the case of PEEK and Si3N4 fusion cages for treating lumbar degenerative disc illness. The authors hypothesized that Si3N4 cages are not inferior to PEEK implants. Two commercial models, Valeo® OL (CTL Amedica, Dallas, TX, USA) and Phantom™ PLIF, DePuy Synthes, were chosen for comparison. The study included patients aged between 18 and 75 years with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration or Pfirmann grade II or above, or degenerative spondylolisthesis grade I and II. The surgical procedure consisted of a TLIF approach performed at single- or double-level and involved, besides one of the above-mentioned fusion cages, also pedicle screws for implant fixation. Both cages were filled with autografts harvested from the lamina and facet joints. Of the 92 patients, 44 were treated with Si3N4 cages and 48 with PEEK implants. As a primary clinical outcome, the average improvement in Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) scores was chosen. It was noticed that the PEEK cohort exhibited lower scores, but with the help of a trendline analysis, no differences regarding the improvement from the pre-operative state at 24 months were reported. The secondary clinical outcomes were related to differences between ODI, back and leg VAS pain scores, and SF-36 Physical or Mental Function. The authors [111] observed that the non-inferiority of ceramic implants could not be established based on a priori protocol margin of 2.6. CT scans taken at the 12-month follow-up revealed that 57 % of Si3N4 cages and 42 % of PEEK implants had formed bone bridges between the patient endplates (p = 0.13). If revision criterium was considered, the study found that in the case of the ceramic cage cohort, 10 patients needed a revision intervention at about 20 months post-surgery due to a neurological necessity, pseudoarthrosis, cage non-union, or screw failure, while in the PEEK group, only 4 patients required a revision due to adjacent level and decompression complications. The main conclusion of this study was that no statistically significant differences regarding the ceramic implant outcomes and PEEK cages could be established. By adding a literature investigation and increasing the non-inferiority margin from 2.6 to 4, the authors confirmed that the Si3N4 cages are non-inferior to their polymeric counterparts. Based on existing literature, it can be concluded that ceramic implants demonstrate good fusion rates and can be confidently used to treat various spinal diseases. Additionally, the properties of Si3N4, compared to other biomaterials used in spinal surgery, have resulted in superior outcomes in some cases, which supports its recommendation. While many studies have reported clinical cases related to cervical fusion surgery, there remains a limited amount of information regarding the use of silicon nitride in lumbar applications. The authors of the present review believe that further studies are needed to establish a higher level of confidence in the use of ceramic implants over traditional PEEK or titanium alloys.

The German company SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH produces several fusion cages that have already received the FDA approval and the CE certification. One of the most used models is MOBIS®/MOBIS® II, with a classical geometry, a bullet nose, controlled insertion at different angles, and smooth lateral surfaces [112,113]. This implant is manufactured from Ti6Al4V according to the ASTM F136/ISO 5832-3 and from PEEK-OPTIMA® according to the ASTM F2026. Haeckel et al. [114] made a study in which they analyzed 82 patients that were treated for spinal disorders based on the TLIF approach using only MOBIS® II ST spinal implants filled with synthetic bone grafts in the case of 42 patients and for the rest of the cohort they applied a hybrid fixation with Dynamic Stabilization System (DSS), involving polyaxially pedicle screws at DSS at the adjacent level. The fusion rates were analyzed using CT scans at 12 months postoperatively. In the case of the hybrid group, based on medical images of 37 participants, interbody fusion was achieved for 31 patients (90 %), partial fusion for 14 % (5 patients), and non-union was noticed in 1 case (3 %). Regarding the other cohort, the CT scans were available for 35 patients. A satisfactory interbody fusion was achieved for 28 cases (80 %), partial union was present in the case of 3 participants (9 %), and non-union was observed for 4 people (11 %). The main conclusion of this study was that the minimally invasive TLIF procedure led to important improvements in patient outcomes regardless of whether or not the DSS could be included in the surgical approach. In another study by Duncan and Bailey [115], the fusion cage migration effect was analyzed for the PEEK MOBIS® model. The authors conducted a prospective randomized study on 102 patients who underwent the TLIF procedure. Taking into consideration the fixation technique, there were established two groups: the unilateral one (20 males and 26 females, average age of 53.5 years, DDD, degenerative spondylolisthesis) and the bilateral one (20 males and 36 females, average age of 55.7 years, DDD, spinal stenosis and/or foraminal stenosis associated with instability). The authors noticed the cage migration in the case of 17 patients (11 from the first group and 7 from the second one). Since the implant migration rate was higher in the case of the first analyzed group, it was established that unilateral fixation is not ideal for preventing entirely cage migration in the case of patients who underwent TLIF procedure. The same PEEK implant model was discussed by Brase et al. [116], showing that purulent spondylodiscitis was treated through dorsal decompression and debridement. After that, posterior stabilization was achieved using PEEK lumbar cages and trans-pedicular screws. The authors [116] concluded that PEEK cages are much safer than Ti alloy implants for use in patients undergoing lumbar revision surgery due to an existing infection. Other fusion cage designs produced by SIGNUS Medizintechnik used in clinical research are the VERTACONNECT [98], TETRIS [117], and POSIDON® [118]. Kitsopoulos et al. [98] presented some preliminary results regarding the VERTACONNECT expandable lordotic interbody cages made of Ti alloy. They analyzed 32 patients, exhibiting 40 surgical addressed segments. It was noticed that in the case of 2 patients, a revision surgery was applied to solve the screw loosening and resulting pseudoarthrosis. Another reported side effect consisted of patient endplate damage due to the cage placement observed in the case of 4 patients and cage subsidence was established for 4 patients. As an overall finding, it was concluded that important improvements regarding segmental lordosis and mean degree of spondylolisthesis were present at 2 years postoperative. Regarding the TETRIS cage, Sorge et al. [117] reported the case of a 66-year-old female with lumbar pain. Firstly, she suffered a PLIF surgical intervention at the L4-L5 level, which was solved by using the above-mentioned interbody cage. Unfortunately, this procedure was unsuccessful, and secondary fractures occurred. It was concluded that the treatment route must be carefully chosen in accordance with the patient's health state and bone quality. In some cases, the authors recommended the combination of vertebroplasty and internal fixation lengthening and said that this procedure should be applied as a last alternative. It can be concluded that the interbody fusion cages produced by SIGNUS Medizintechnik are safe enough to ensure a good interbody spinal fusion, and regarding the newest models, they should be carefully treated and analyzed to establish if some improvements are necessary to be performed to avoid revision surgeries.

Another important player in the interbody fusion cage market is Medtronic, based in Minneapolis, MN, USA. One of the most commonly used models in clinical cases is the PEEK bullet-tip design Capstone cage. It features an open volume geometry that allows for the introduction of graft material or synthetic bone, surface teeth to prevent implant expulsion, tantalum markers for X-ray imaging, a convex shape that conforms well to the anatomical structure, and it is available in various sizes to accommodate patient characteristics. Zhou et al. [119] analyzed the influence of vertebral endplate morphology on Capstone cage subsidence in patients who underwent a TLIF surgical approach at the L4-L5 segment. Three groups of patients were analyzed: concave group, flat group, and irregular group, based on their endplate shapes. The authors noticed that the unwanted side effects of cage subsidence occurred in 23 cases (15.9 %) from 145 patients after 1-year follow-up. It was concluded that a higher number of implant failures occurred in patients with irregular endplate geometry. Consequently, anatomical geometry plays a crucial role in ensuring the success of surgical intervention (Fig. 3.V). Mun et al. [120] compared the outcomes of the Perimeter PEEK cage with the ones of the PEEK Capstone cage, both manufactured by the Medtronic company, based on two different surgical approaches: OLIF and TLIF. 74 patients were selected for each type of implant and surgical approach. At 6 months, higher fusion rates of 81.1 % and 87.8 % were observed after OLIF and TLIF, respectively. A lower subsidence rate of 16.2 % was attributed to the OLIF intervention. In conclusion, the authors stated that the OLIF procedure was much more effective than the TLIF due to the better stability of the implant. Other literature studies compared this type of cage with those developed by other producers, and some of them are detailed in Table 1 [[121], [122], [123]] (Fig. 3.II). Clydesdale cage is another implant employed in many clinical treatments for spine diseases. It is made entirely of PEEK with a thin titanium layer with a thickness of 0.1 mm. This coating imparts the implant with an increase in friction coefficient and a larger surface area, which benefits new bone growth. Moreover, because the titanium coating is very thin, it does not alter the mechanical properties or radiolucency of the PEEK substrate. Some advantages of the Clydesdale design include the bullet-nosed tip and the convex geometry placed in the contact zone with the endplates. Liu and Feng [124] performed a preliminary clinical study with devoted attention to the advantages and disadvantages of the OLIF in addition to the use of an anterolateral screw-rod system. 14 patients included in this study suffering from spondylolisthesis, disk hernia, and degenerative lumbar stenosis were treated based on a Clydesdale Spinal System, Medtronic, MN, USA, which was filled with synthetic bone graft from Novabone, FL, USA. After a follow-up of about 45 months, a radiological fusion rate of 95 % was achieved (Fig. 3.VII). No important complications, such as infection or ureteral and vascular injuries, were reported. Unfortunately, a cage subsidence was found in the case of one patient. The authors concluded that the OLIF procedure, in combination with the anterolateral screw-rod fixation, led to good treatment results by reducing, at minimum, the blood loss, hospitalization time, and radiological exposure of the patient. Woods et al. [125] made a retrospective cohort study of 137 patients. For the treatment of different spine diseases, in all cases, a PEEK Clydesdale cage packed with rhBMP-2 (Medtronic, INFUSE) and demineralized bone matrix (MASTERGRAFT Medtronic) mixed with autologous bone marrow was used. At 6-month follow-up, complications such as cage subsidence (4.4 %), vascular injury (2.9 %), and postoperative ileus (2.9 %) were reported. A fusion rate of approximately 97.9 %, coupled with the absence of neurological injury, led to the study's main conclusion: the OLIF procedure and Medtronic cages were well-suited for treating complex spinal diseases and improved the patient's quality of life after 6 months. The Crescent cage is an interbody fusion implant with a distinctive banana-shaped design, bullet-nosed tip, 6° lordosis, and teeth for implant fixation. It is manufactured from Ti alloy medical grade or PEEK [126]. Choi et al. [127] investigated the outcomes and technical feasibility of the MIS-TLIF surgical approach based on a banana-shaped cage (Medtronic) or straight cage (Opal, DePuy Synthes Spine, Massachusetts, USA). They included 21 patients in their study, with an average age of 62 years and a mean follow-up period of 12–36 months. The straight cage was used in the case of 13 patients (61.9 %) and the banana-shaped one for 8 patients (38.1 %). A fusion rate of 86.7 % was reported, together with the observation that in many cases, the cage position was established to be anteromedial. In addition, the VAS scores for leg and back pain and ODI scores improved by a high amount after the surgery, although cage subsidence was noticed for 7 patients (33.3 %). It was concluded that the cages used are adequate for treating conditions such as spondylolisthesis or spinal stenosis based on the MIS-TLIF surgical approach. From the studies mentioned above, it can be concluded that Medtronic fusion cages can be introduced into the human body based on modern and minimally invasive techniques and are very suitable for treating different spine conditions. They are usually used in Asia and the USA and seldom in Europe.

The Cougar® LS lateral cage system was developed by the DePuy Synthes company. It is made of carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK Optima and is available on the market in two configurations: parallel and lordotic. This model can be manufactured in various sizes to match the different anatomical particularities of the patient. The radiopacity of the cage is ensured by tantalum wire markers. Rentenberger et al. [128] analyzed the perioperative risk factors associated with early revisions in the case of stand-alone lateral lumbar interbody fusion. A single- or multi-level LLIF procedure was applied to insert the XLIF system (NuVasive, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) or COUGAR cage (DePuy Synthes, Raynham, MA, USA). The authors [128] selected 133 patients: 21 needed revision surgery, and 4 were recommended for it after only 1-year post-surgery. All these patients exhibited neurological symptoms, and no important difference was noticed between the revision and nonrevision groups. However, it was assumed that patients with foraminal stenosis may require revision surgery following the LLIF procedure, as this type of intervention could be associated with neurological pain or other complications. Another device commonly encountered in clinical practice is the Synfix-LR, a PEEK spacer implant attached to a Ti locking plate. Its height could be between 12 and 19 mm with a surface area of 26 × 32 mm2 or 30 × 38 mm2 and a lordosis angle equal to 8° or 12°. Stosch-Wiechert et al. [129] studied the incidence of revision surgery and adjacent segment degeneration in the case of 37 patients suffering from spondylolysis. The minimum follow-up was established at 60 months. 8 patients needed secondary surgery due to some complications that occurred at the cranially adjacent level. Regarding facet joint- or disc-degeneration occurred at the adjacent levels, a percentage of 35.1 % and 24.3 % were established. The main conclusion of this study was that preserving the health of the adjacent levels is of utmost importance in clinical practice, and the surgical technique and implant fusion cage must be carefully chosen to ensure optimal conditions for good and efficient bone fusion. Other studies [130,131] that investigated the Synfix-LR device are presented in Table 2. The fusion cages developed by DePuy Synthes showed good confidence in obtaining a satisfactory fusion rate, but some case reports analyzed their side effects and established a certain occurrence of cage subsidence appearance. It can be also concluded that they present an advantage over their counterparts on the market because they are available in different sizes and with various lordosis angles.

Table 2.

Permanent and bioresorbable interbody fusion cages used in current clinical practice.

| Interbody spinal cage commercial name, producers | Locations where the study was made and/or the patients were selected | Geometry/Material | Ref. | Number of patients/Follow-up time | Study design type | Surgical approach | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent implants | |||||||

| FlareHawk®, Integrity Implants Inc./Accelus, Palm Beach Gardens, FL | USA | PEEK shell that expands bidirectionally/Ti shim | [102] | 58 patients for the investigation related to a 1-year intervertebral fusion process and 45 patients with Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), VAS for back pain, or VAS leg pain with an average follow-up of 4.5 months | Retrospective cohort (retrospective analysis) | PLIF or TLIF/1 or 2-levels between L2 and S1 based on autogenous or allogeneic grafts; patients had a supplementary posterior pedicle screw fixation | This investigation gives preliminary clinical evidence regarding the safety of FlareHawk® expandable devices. Both surgical procedures were adequate and led to significant improvements related to patient life quality, as well as good fusion rates |

| FlareHawk® 9, Integrity Implants Inc./Accelus, Palm Beach Gardens, FL | Greece | [104] | 58 patients/36 males and 22 females with diagnoses such as spinal canal stenosis (40), spondylolisthesis with slip percentage 25 % (5), failed back surgery syndrome revision surgery (5), adjacent segment disease (2), and recurrent herniated disc (7) | Retrospective cohort (retrospective analysis) | Open PLIF and decompression | The patients' ODI index improved in the case of 45 patients exhibiting a decrease from 48.6 preoperative to 23.1 postoperative remains almost unchanged for 8 patients (mean preoperative value of 49.7; mean postoperative value of 48.1, and in the case of 5 patients it worsened with an increased value from 50 to 54.2 (p value of 0.05) | |

| FlareHawk®, Integrity Implants Inc./Accelus, Palm Beach Gardens, FL | USA | [101] | 7 patients; 1-year follow-up | Case series (retrospective analysis) | PLIF/1 or 2-level PLIF constructs with 2 cages with fixation consisting of pedicle screw and rods | The cage highly conformed to the interbody space in the case of each patient. The interbody device deformation was not harmful to bone growth and new bone formation | |

| FlareHawk®, Integrity Implants Inc./Accelus, Palm Beach Gardens, FL | USA | [103] | 13 patients/symptomatic spondylolisthesis/7 cases at L5-S1, 1 case at L3-4, acasend 5 cases at L4-5/Grade 1–86 % cases, Grade 2–14 cases | Case series (retrospective review of patient records) | MIS TLIF | The FlareHawk® biplanar expandable cage is adequate for the spondylolisthesis based on MIS TLIF surgical approach. Important improvements in all radiographic parameters were postoperatively obtained | |

| Modulus ALIF – 3D printed porous titanium implant for anterior spine surgery/NuVasive CoRoent XL PEEK; NuVasive | Japan | 3DTi cages exhibited a bullet shape, while the sPEEK implants had spikes, serrations, and angular corners | [99] | 32 patients, 22 females and 10 males | Retrospective cohort | Anterior and posterior combined surgery with XLIF and posterior fusion (pedicle screw-rod system) | The local lordotic angles were preoperatively equal to 4.3° (3DTi) and 4.7° (sPEEK) and postoperatively these values were corrected to 12.3° (3DTi) and 9.1 (sPEEK) (p = 0.013). None of the patients treated with 3DTi cages exhibited VEC progression, but for the sPEEK cages, eight levels (21 %) were characterized by VEC progression. The 3DTi cage generated low endplate injuries compared to the other model |

| PEEK cage systems (XLIF – NuVasive, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA and COUGAR – DePuy Spine Inc., Raynham, MA, USA); 3D-printed Ti cages (Modulus XLIF (NuVasive, Inc.) and Lateral Spine Truss System (4WEB Medical, Inc., Frisco, TX, USA)) | Germany, USA | PEEK cages, 3DTi -printed cages with porous architecture | [105] | 91 patients, 49 patients included in the early group and 42 patients from the late analysis group | Retrospective cohort (retrospective study) | SA-LLIF from L1-L2 to L4-L5 | The porous 3D-printed Ti cages were characterized by an increased fusion rate compared to their PEEK counterparts due to a very good osteoconduction. PEEK was considered an inert material, which usually did not enhance the new bone formation |

| Titanium threaded or 3D-printed porous titanium (XLIF Modulus NuVasive, San Diego, CA, USA) | Italy, USA | Ti conventional and porous cages | [106] | 135 patients, 51 patients (Group A – porous Ti cage), 84 patients (Group B – conventional threaded Ti cage)/degenerative spondylolisthesis | Retrospective cohort (retrospective, single-center radiological study) | LLIF and posterior percutaneous screw fixation | The porous Ti cages are more adequate for spine diseases by facilitating the bone ingrowth and bridging space and offering an increased stability and a successful bone fusion if one considers the criteria of intervertebral BB and ZJ Pathria |

| Valeo I AL, Valeo II AL, Valeo I TL, Valeo II TL, Valeo I PL/OL, Valeo II PL/OL | USA/worldwide analysis | I and II generation of classical Si3N4 cages | [110] | 450 patients USA with Si3N4 cages compared with 1025 patients with other types of implants localized worldwide/variable follow-up time between 12 months and 6.4 years/all patients treated for spondylolisthesis, degenerative disc disease, disc herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylosis, spinal instability, radiculopathy, post-traumatic deformity, and infectious discitis | Retrospective cohort (retrospective review) | ALIF, TLIF, PLIF | The Si3N4 cages exhibited good outcomes compared with other biomaterial cages leading to a decrease in VAS score |

| Valeo® OL (CTL-Amedica, Dallas, TX, USA) and PEEK Phantom™ PLIF, DePuy Synthes | USA, worldwide | Si3N4 cage with 0° lordosis and PEEK implant with 6° lordosis | [111] | 92 patients, 44 were treated with Si3N4 cages and 48 with PEEK implants/follow-up 2 years/all patients treated for degenerative disc disease, isthmic spondylolisthesis, grade 1, isthmic spondylolisthesis, grade 2, degenerative spondylolisthesis, grade 1, degenerative spondylolisthesis, grade 2 | Randomized controlled trial | TLIF | It was confirmed that the Si3N4 cages are non-inferior to their polymeric counterparts. |

| Valeo®TL VBR Lumbar Spacer/Amedica Corporation, Salt Lake City, UT | USA | Silicon nitride (Si3N4) cage with a dense load-bearing component and a porous one in combination with an original surface texture | [109] | 2 patients (47- and 77-year-old women)/1year follow-up/47-year-old patient: TLIF for lumbar spinal stenosis at L4-L5 combined with axial low back pain and neurogenic claudication; 77-year-old patient: TLIF for lumbar spinal stenosis L4-L5 and disc space collapse L4-L5, with no reported neurological problems before surgery | Case report | TLIF | 47-year-old patient: anterior I grade fusion, posterior grade II fusion. 77-year-old patient: grade I fusion both posteriorly and anteriorly with bone bridging the disc space |

| MOBIS®II ST/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | Australia | A classical geometry that exhibits a bullet nose, controlled insertion at different angles, and smooth lateral surfaces/Ti6Al4V | [114] | 82 patients, average age of 62.1 years, 57 % female | Retrospective cohort (retrospective study) | 41 patients (50 %) underwent TLIF, and 41 people received a hybrid procedure consisting of TLIF and DSS | The minimally invasive TLIF procedure led to important improvement in patient outcomes regardless of the possibility to include in the surgical approach the DSS or not |

| MOBIS®/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | USA | PEEK | [115] | 102 patients, unilateral fixation technique (20 male and 26 female, average age of 53.5 years, degenerative disc disease, degenerative spondylolisthesis); bilateral fixation technique (20 male and 36 female, average age of 55.7 years, DDD, spinal stenosis and/or foraminal stenosis associated with instability) | Prospective randomized study | TLIF with unilateral and bilateral fixation technique | Due to the fact that the implant migration rate was higher in the case of the first analyzed group it was established that unilateral fixation is not ideal in preventing entirely the cage migration |

| MOBIS® I/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | Germany | PEEK | [113] | 39 patients (Group I – 8 patients – with fusion in every segment; Group II – 9 patients – with no fusion in one or both segments; Group III – 22 patients – with no fusion in one or both segments, exhibiting a stable pseudarthrosis) | Retrospective cohort (retrospective study) | TLIF | The study did not underline a notable difference between the fusion rates in L3-L4 or L4-L5. It was concluded that the fibrocartilaginous tissue formed in and out of the cage was enough to reduce the patient's pain |

| VERTACONNECT/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | Germany | Biconvex design with toothed surface and diagonal implant placement/Ti alloy [112] | [98] | 32 patients, 25 patients with monosegmental treatment, 6 were treated bisegmentally, 1 was treated trisegmentally | Retrospective cohort (prospective study) | TLIF, two-year follow-up | Important improvement regarding segmental lordosis and mean degree of spondylolisthesis were present at 2 years postoperative |

| MOBIS®/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | Germany | PEEK | [116] | 6 patients, average age 65.8 years, treated for lumbar purulent spondylodiscitis | Case series (retrospective study) | TLIF | PEEK cages are much safer than Ti alloy implants to be used in the case of patients with lumbar revision surgeries that occurred due to an existent infection |

| TETRIS/SIGNUS Medizintechnik GmbH | Germany | Toothed surface, adequate for MRI imaging, smoothed lateral surfaces/PEEK - OPTIMA | [117] | 1 patient | Case report | PLIF | The treatment route must be carefully chosen in accordance with the patient's state of health and bone quality. In some cases, it is recommended the combination of vertebroplasty and intern fixation lengthening, but this procedure should be applied as a last alternative |

| Capstone/Medtronic, Memphis, Tennessee, USA | China | Bullet-tip design with an open volume geometry, teeth on its surface to hinder the implant expulsion, tantalum markers, a convex shape that suits well to the place anatomy/PEEK | [119] | 145 patients (41 males and 104 females)/mean follow-up of 33.8 ± 12.3 months | Retrospective cohort (retrospective study) | TLIF and pedicle screw instrumentation via an open posterior approach | The vertebral endplate morphology has an important influence on cage subsidence |

| PEEK Capstone (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and PEEK Perimeter (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA) | South Korea | PEEK Capstone cage; PEEK Perimeter cage with a large and round shape, teeth placed on the superior and inferior implant surface, and a hollow geometry for autogenous bone graft | [120] | 74 patients underwent OLIF surgery (Perimeter cages) and 74 were treated with Capstone cages at L5-S1 level based on a TLIF approach | Retrospective cohort (retrospective single-center study) | TLIF and OLIF | The OLIF was considered a much more suitable procedure than TLIF because it produced a successful decompression of foraminal stenosis and generated a higher lordotic angle value. It was concluded that all these positive effects were due to the fact that the Perimeter cage exhibited important mechanical support due to its larger geometry |

| PEEK Capstone (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA) and PEEK PLIVIOS (Depuy Synthes, Raynham, MA, USA) | South Korea | PEEK bullet-shaped Capstone cage, rotation type PEEK PLIVOS cage | [121] | 784 patients exhibiting 881 lumbar levels/prospective observational longitudinal study/5-year analysis | Retrospective cohort (prospective observational longitudinal study) | TLIF | Cage migration without subsidence was noticed in 20 cases, while cage migration with subsidence was present for 37 patients. Cage retropulsion was observed in 17 patients. The main risk factors for the cage migration side effect were associated with osteoporosis, unilateral cage use, pear-shaped disc, and endplate injury |

| PEEK Synfix cage (DePuy Synthes, Welwyn Garden City, UK)- ALIF; PEEK Capstone Cage (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA) – TLIF; two dedicated PEEK cages from Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA - PLIF |

South Korea | Synfix, standalone implant with a geometrical shape ensuring an increased stability/PEEK, PEEK classical Capstone cage | [122] | 77 patients were divided into 3 groups: 26 patients in the ALIF group, 21 patients in the TLIF group, and 30 patients in the PLIF group/1–2 years of follow-up | Retrospective cohort (comparative retrospective study) | ALIF, TLIF, PLIF | A better segmental lordosis restauration was achieved for the ALIF procedure. The fusion rate was not statistically different (69.2 % -ALIF, 72.7 %-TLIF, 64.3 % -PLIF). PLIF approach exhibited the lowest cage subsidence of 10 % compared to 15.4 % - ALIF and 38.1 %-TLIF (all the reported data are determined at 2 years postsurgical) |

| Capstone (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, Tennessee, USA) and Opal (DePuy Synthes Spine, Raynham Massachusetts, USA) – minimally invasive MIS-TLIF; Clydesdale (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, Tennessee, USA) OLIF | South Korea | For MIS-TLIF surgical approach there were used 0° cages, and in the case of OLIF group, for 20 patients there were used 6° cages and for 5 patients 12° cages/PEEK | [123] | 25 patients in each MIS-TLIF and OLIF groups | Retrospective cohort (comparative retrospective study) | MIS-TLIF, OLIF | OLIF surgical procedure was linked to a much more reduced hospitalization time, a lower blood quantity, as well as an excellent disc height restauration and earlier time to fusion |

| Clydesdale Spinal System, Medtronic, MN, USA | USA | PEEK Clydesdale cage packed with rhBMP-2 (Medtronic, INFUSE), demineralized bone matrix (MASTERGRAFT Medtronic), which was mixed with autologous bone marrow | [125] | 137 patients/6 months | Retrospective cohort (retrospective cohort study) | OLIF | Complications such as cage subsidence (4.4 %), vascular injury (2.9 %), and postoperative ileus (2.9 %) were reported. A good fusion rate of about 97.9 %, in combination with the absence of neurological injury, led to the main conclusion, which stated that the OLIF procedure and Medtronic cages were properly chosen to treat complicated spine disease |

| Crescent (Medtronic, MN, USA) and Opal, (DePuy Synthes Spine, Massachusetts, USA) | South Korea | The Crescent cage is an interbody fusion implant that has a distinctive banana shape design with a bullet nose, 6° lordosis and teeth for implant fixation. The Opal cage is made of PEEK | [127] | 21 patients/follow-up between 12 and 36 months. The straight cage was used in the case of 13 patients (61.9 %) and the banana-shaped one for 8 patients (38.1 %). | Retrospective cohort (retrospective study) | MIS-TLIF | A fusion rate of 86.7 % was reported together with the observation that, in many cases, the case position was established to be anteromedial. In addition, the VAS scores for leg and back pain and ODI scores improved by a high amount after the surgery, although cage subsidence was noticed for 7 patients (33.3 %) |