Abstract

DNA G-quadruplexes (G4s) are non-B-form DNA secondary structures that threaten genome stability by impeding DNA replication. To elucidate how G4s induce replication fork arrest, we have characterized fork collisions with preformed G4s in the parental DNA using reconstituted yeast and human replisomes. We demonstrate that a single G4 in the leading strand template is sufficient to stall replisomes by arresting the CMG helicase. Electron cryomicroscopy structures of stalled yeast and human CMG complexes reveal that the folded G4 is lodged inside the central CMG channel, arresting translocation. The G4 stabilizes the CMG at distinct translocation intermediates, suggesting an unprecedented helical inchworm mechanism for DNA translocation. These findings illuminate the eukaryotic replication fork mechanism under normal and perturbed conditions.

Faithful replication of chromosomal DNA prior to cell division is essential for genome maintenance. Chromosomal DNA replication in all cells occurs at replication forks and is catalyzed by macromolecular complexes, called replisomes, which coordinate the unwinding of the parental DNA with the synthesis of the two daughter strands. Importantly, uninterrupted replisome progression is frequently challenged by obstacles in the chromosomal template, such as transcription, DNA damage, R-loops, or non-B-form DNA secondary structures, causing replication stress that poses a threat to genome stability (1).

DNA G-quadruplexes (G4s) are non-B-form DNA secondary structures that can form at telomeres and during the transcription or replication of G-rich repeats across the genome (2). G4s are polymorphic four-stranded structures comprising stacks of G-quartets that are each composed of four guanines arranged in a planar ring (3). While implicated in various genomic functions, G4s can also pose an obstacle to DNA replication by impeding DNA polymerases (4) or the replicative DNA helicase, CMG (Cdc45-MCM-GINS) (5, 6). G4s formed during DNA replication collide with DNA polymerases in the wake of the CMG (7, 8), whereas G4s formed during transcription are initially encountered by CMG (5, 9). R-loops likely contribute to the persistence of G4s, as indicated by their genome-wide overlap (10–14). Consistent with this notion, G4-stabilizing ligands induce R-loop-dependent transcription-replication conflict in human cells (15, 16) and G4s block fork progression at R-loops in vitro (5, 9). Because of their genotoxic potential, G4s are tightly controlled by G4-binding proteins and DNA helicases (17, 18). Disruption of G4 regulation, either through loss of proteins that control G4s or stabilization by small molecules, can compromise genome integrity and hinder DNA replication (15, 19–23), raising interest in G4 ligands for cancer therapy (24, 25).

CMG is composed of a hetero-hexameric ring of Mcm2–7 (MCM) ATPase subunits and the non-catalytic Cdc45 and GINS (26). The MCM ring forms a two-tiered structure comprising a structural N-terminal tier (N-tier) and a catalytic C-terminal tier (C-tier) harboring the AAA+ ATPase domains. At the replication fork, CMG translocates along the leading strand template in the 3’−5’ direction while sterically displacing the lagging strand template (27). Electron cryomicroscopic (cryo-EM) studies have revealed how CMG binds forked DNA, with N-terminal β-hairpin loops coordinating the fork junction, and C-terminal hairpin loops, termed pre-sensor 1 (PS1) and helix-2-insert (H2I), mediating ATP-dependent DNA translocation. (28–32). Despite these advances, the precise mechanism of CMG translocation remains unclear (33, 34). The most widely accepted model is a rotary hand-over-hand mechanism, where ATP turnover drives the sequential movement of individual MCM subunits along the DNA (29, 35). However, certain MCM ATPase sites are dispensable for CMG helicase activity (29, 36), leading to the proposal of an asymmetric hand-over-hand mechanism in which specific subunits advance pairwise along the DNA (29). An alternative “pumpjack” model, suggesting CMG cycles between extended and compact states (37), was later disputed due to lack of DNA context in the original structural data (31).

In the replisome, CMG associates with numerous accessory proteins, including the fork protection complex (FPC), composed of Mrc1 and Tof1-Csm3 in budding yeast or CLASPIN and TIMELESS (TIM)-TIPIN in humans (38). Tof1-Csm3/TIM-TIPIN form a crescent-shaped α-helical complex that associates with the MCM N-tier and coordinates parental DNA ahead of CMG (28, 30, 32, 39). This extensive DNA engagement raises the question of where G4-induced fork stalling occurs in the replisome. To investigate this question, we examined yeast and human replisomes colliding with preformed G4s in the parental DNA and determined high-resolution cryo-EM structures of CMG stalled at a G4. The data reveal a conserved mechanism for G4-induced replisome arrest and suggest a novel DNA translocation mechanism for CMG.

Results

A single G4 in the leading strand template is a potent block to the yeast replisome

Previously, using the reconstituted, origin-dependent budding yeast DNA replication system, we observed that R-loop-associated G4s on the leading strand template impede fork progression by inhibiting the CMG helicase (5). A limitation of this study was the structural heterogeneity of the R-loops, which resulted in a variable G4 potential of the displaced strands (5). Therefore, to investigate the impact of preformed G4s on fork progression under defined conditions, we generated DNA templates harboring a single, structurally defined G4 positioned ~1.9 kbp from a yeast replication origin. For this, we ligated DNA fragments containing a preformed G4 site-specifically into plasmid DNA, analogous to a previous approach (6). Subsequent linearization of the templates places the G4 in the path of the rightward replication fork while the leftward fork runs off the opposite template end. We focused our studies on a prototypical G4, composed of the sequence (GGGT)4, which forms a parallel propeller-type structure (40). To stabilize the G4, a poly(dT) sequence was placed opposite the G4.

As expected, a B-form DNA fragment does not present an impediment to the rightward fork (Figure 1). A minor population of leading strand products terminates at the position of the inserted DNA fragment, which is attributed to replisome run-off at leading strand nicks resulting from incomplete ligation of the DNA insert. In contrast, the rightward fork efficiently arrests at the preformed G4 in the leading strand template as evidenced by the accumulation of stalled leading strand products at the expense of full-length leading strand products in the denaturing gel and the concomitant accumulation of stalled fork structures in the native gel. Uncoupled replication products in the native gel indicate limited replisome bypass of the G4 in the absence of continued leading strand synthesis. Consistent with earlier observations (5, 6), a preformed G4 on the lagging strand template does not block fork progression. Thus, a single preformed G4 specifically on the leading strand template is sufficient to stall yeast replication forks.

Figure 1: A single G4 in the leading strand template is sufficient to block replication fork progression.

(A) Denaturing (bottom) and native (top) agarose gel analysis of replication products obtained in the reconstituted yeast system on DNA templates harboring no G4 (lanes 1+2), a G4 on the leading strand template (lanes 3+4) or a G4 on the lagging strand template (lanes 5+6). RI: Replication intermediates. (B) Schematic of replication products obtained in (A). Red: Leading strand products; Blue: Lagging strand products.

Since the FPC has been implicated in the replication of structured DNA repeats (41) and G4 sequences (42), we next asked if the FPC influences CMG helicase activity on G4-containing DNA substrates. For this, CMG helicase assays were conducted in the absence or presence of FPC. Consistent with previous observations in the origin-dependent yeast DNA replication system (43, 44), we find that the FPC increases both the rate and amplitude of substrate unwinding, demonstrating that the stimulatory effect of the FPC on CMG helicase activity is direct (Figure S1). Moreover, like CMG alone (5, 45), CMG-FPC is inhibited specifically by a G4 in the leading strand template (Figure S1). This indicates that the FPC is neither responsible for the G4-induced block to CMG progression nor does it promote the unwinding of DNA G4s by CMG.

To determine if the block to CMG progression is influenced by G4 topology, we tested the effect of G4s with parallel, antiparallel or hybrid topologies (46), as well as a G4 derived from the human CEB25 minisatellite sequence that features an extended 9 nt loop (47), on CMG-FPC helicase activity. All tested G4s inhibited DNA unwinding by CMG-FPC to a similar degree (Figure S2). Thus, the block to CMG-FPC progression is not dependent on G4 topology.

The stalled CMG-FPC engages DNA upstream and downstream of a leading strand G4

We next developed exonuclease protection assays to investigate the position of the G4 with respect to CMG-FPC using forked oligonucleotide-based DNA substrates harboring a prototypical G4 24 bp downstream of the fork junction in the leading strand template, followed by 35 bp of dsDNA downstream of the G4. Since the CMG travels in 3’−5’ direction on the leading strand template with the MCM N-tier facing forward (48, 49), we mapped the position of the C-terminal face of CMG with Exonuclease T (Exo T), a single strand-specific 3’−5’ exonuclease (50). For this, we radiolabled the 5’ end of the G4-containing strand. Reaction products were analyzed by sequencing gel analysis. The single-stranded leading strand template is efficiently digested by Exo T up to one nucleotide from the 3’ end of the preformed G4, demonstrating that the G4 presents an obstacle to Exo T (Figure S3A). In contrast, when the leading strand template is annealed to the lagging strand template, Exo T digests the leading strand template only up to the fork junction, consistent with the single strand specificity of Exo T.

To test the utility of our exonuclease protection assay to map the position of CMG-FPC on DNA, we initially probed CMG-FPC stably bound to the fork junction in the presence of the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP). Reactions were probed with Exo T for two minutes prior to DNA extraction. These conditions yielded a distribution of Exo T stall sites ~22–24 nt upstream of the fork junction (Figure S3B), which agrees with the structural dimensions of CMG-FPC on DNA (28, 31, 32). We also observe a CMG-dependent protection of the 3’ end of the leading strand template. Exo T stall sites at the original fork junction are prominent in all reactions due to incomplete template occupancy by CMG-FPC. Time course analyses reveal that CMG-FPC loading at the fork plateaus after 10 minutes (Figure S3C) and is stable even when challenged with Exo T for up to 30 minutes (Figure S3D).

To determine the position of CMG-FPC stalled at a leading strand G4, CMG-FPC was assembled at the fork in the presence of a low concentration of AMP-PNP, followed by addition of Exo T and subsequent activation of the CMG-FPC with excess ATP (Figure 2A). 2 minutes after addition of ATP, the Exo T stall sites 22–24 nt upstream of the fork junction as well as the fully protected strands diminish and new Exo T stall sites appear ~15 nt upstream of the fork junction, indicating that the CMG-FPC has moved through the fork junction. From 10 minutes onward, Exo T stall sites upstream of the fork junction are absent and a new population of Exo T stall sites, centered ~13 nt from the G4 3’ end, becomes apparent and remains stable for the duration of the experiment. Since Exo T cannot progress past the fork junction on free DNA, these data indicate that CMG-FPC has unwound the duplex region downstream of the fork junction, allowing Exo T to digest the leading strand template in its wake. Notably, we observe an equivalent CMG-FPC stall position on DNA templates in which the G4 is removed 34 bp from the fork junction, demonstrating that the CMG-FPC stall position is independent of the distance of the G4 from the original fork junction (Figure S4A). We conclude that the C-terminal face of the stalled CMG is located ~13 nt from the 3’ end of the G4, suggesting that the G4 is internalized by CMG-FPC.

Figure 2: The stalled CMG-FPC protects DNA upstream and downstream of the G4.

(A) 3’ exonuclease protection analysis to determine position of the C-tier of yeast CMG-FPC stalled at G4 on the leading strand template. (B) 5’ exonuclease protection analysis to determine position of the N-tier of yeast CMG-FPC stalled at G4 on the leading strand template. (C) Schematic summarizing data from (A) and (B). Green: CMG. Yellow: Tof1-Csm3 (TC). N: N-terminal. C: C-terminal.

If the G4 has entered the CMG channel, DNA downstream of the G4 should also be protected by the stalled CMG-FPC. To test this prediction, we developed a 5’ exonuclease protection assay to map the position of the N-terminal face of the CMG-FPC. For this, we incorporated a single 32P group via a splint ligation approach into the backbone of the leading strand template 2 nt downstream of the fork junction and probed the position of CMG-FPC with T5 exonuclease or a combination of 5’ exonucleases with complementary substrate specificities, including T7 exonuclease, RecJf, ExoVIII and T5 exonuclease. Both approaches yielded comparable results.

In the presence of AMP-PNP, i.e. when the CMG-FPC complex is stably bound to the fork junction, the leading strand template is digested up to the G4 (Figure 2B). Following activation of CMG-FPC with ATP, DNA downstream of the G4 is protected from 5’ exonuclease digestion, indicative of CMG-FPC stalling at the G4. CMG alone protects up to ~14 bp downstream of the G4 5’ end, while an additional 8–12 bp are protected in the presence of the FPC, consistent with Tof1-Csm3 engaging ~1 turn of parental DNA ahead of the CMG (28). Collectively, the data demonstrate that the stalled CMG-FPC protects up to 13 bp of DNA on the 3’ side and 22–26 bp DNA on the 5’ side of a leading strand G4, corroborating that the G4 has entered CMG (Figure 2C).

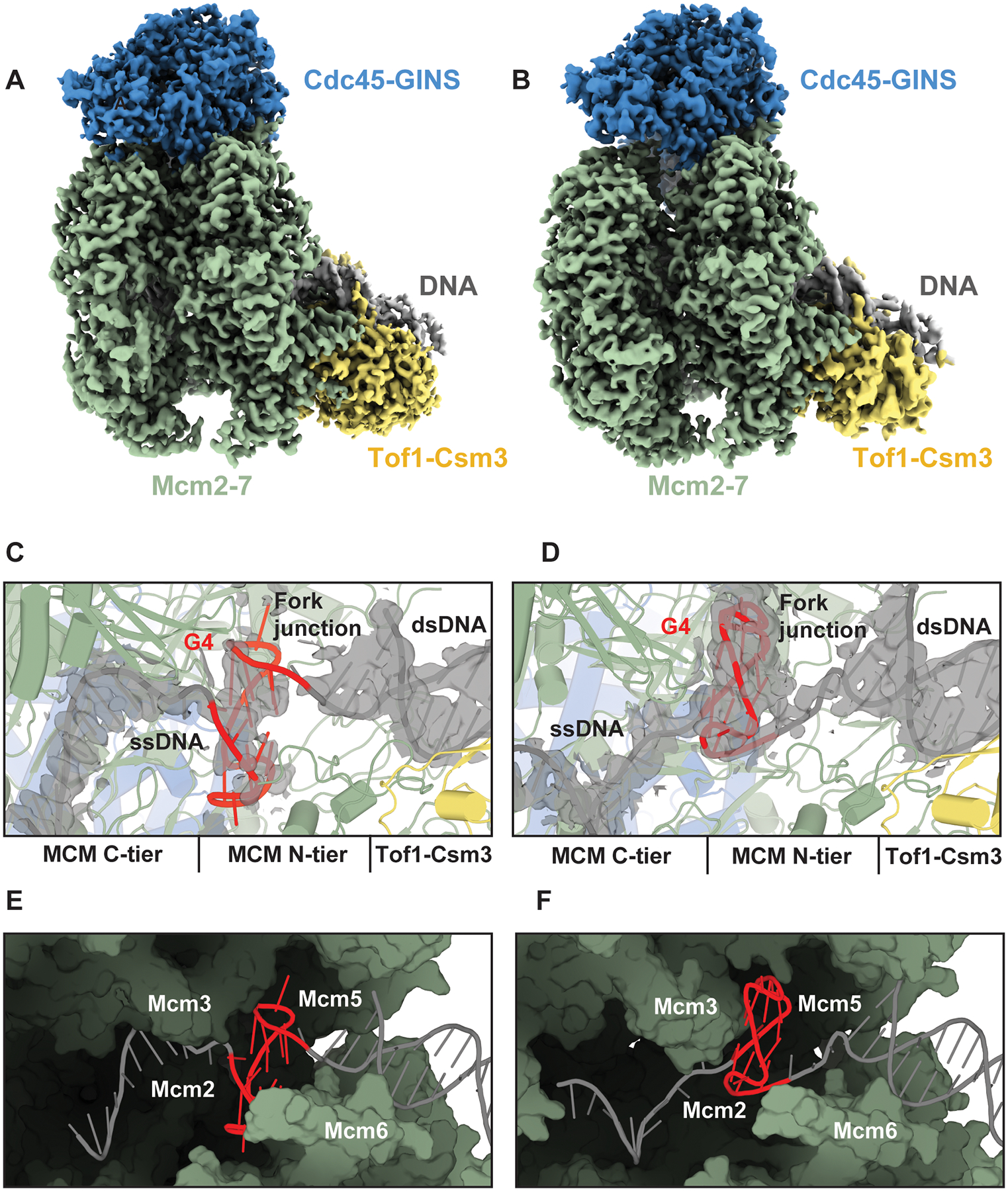

The G4 is trapped at the N-tier/C-tier interface inside the central CMG channel

To determine the structural basis for the G4-induced block to replisome progression, we collected cryo-EM images of yeast CMG-FPC stalled at a leading strand G4. As before, CMG-FPC complexes were assembled in the presence of AMP-PNP on forked DNA harboring a preformed G4 in the leading strand template, 24 bp downstream of the fork junction. DNA unwinding by CMG-FPC was subsequently induced by adding excess ATP. After an incubation time of 10–30 minutes, reactions were vitrified on cryo-EM grids for image collection without the use of any chemical crosslinking agents. Image analysis revealed multiple distinct populations among the particles. Notable differences among the classes relate to the position of the leading strand template in the MCM C-tier, the position of the G4, the ATP-bound state, and the occupancy of Tof1-Csm3 adjacent to the MCM N-tier. Due to their completeness, we will focus our discussion on two major conformations in which the MCM C-tier and Tof1-Csm3 are well resolved, referred to hereafter as states 1 and 2. Reconstruction of state 1 achieved a global resolution of 3.2 Å that was subsequently improved by focused refinements to local resolutions of 3.1–3.2 Å, whereas state 2 achieved a global resolution of 3.5 Å that was improved to 3.3–4.3 Å via focused refinements (Figures S5 and S6A,B).

States 1 and 2 share numerous similar features including possession of the forked DNA template, intact MCM rings, Cdc45-GINS and Tof1-Csm3 (Figure 3A–D). In both states, we also observed densities that allowed unambiguous modeling of the G4 within the central channel at the interface between the MCM N- and C-tiers (Figure 3B,D). Within the channel, the G4s adopt parallel-stranded propeller-type conformations that superimpose well with the NMR structure of an analogous G4 free in solution (Figure S7, RMSD ~1.5 Å). However, the orientations of the G4s within the central channel differ for the two states. In state 1, the G4 extends toward Mcm2 and Mcm6. In state 2, the G4 is rotated ~180° in plane, extending instead toward Mcm3 and Mcm7. The two conformations of the G4 are accomodated by a cavity at the N-tier/C-tier interface (Figure 3E,F). Consistent with the notion that this central cavity can accommodate excess DNA, we find using the 3’ exonuclease protection assay that the CMG-FPC arrests at identical positions at the compact prototypical G4 and the larger CEB25 G4 harboring an extended 9 nt loop (Figure S4B).

Figure 3: The G4 is lodged inside the central channel of stalled yeast CMG-FPC.

(A,B) Cryo-EM density map of yeast CMG-FPC stalled at G4, state 1 (A) and state 2 (B) colored by subcomplex with Mcm2–7 in green, Cdc45-GINS in blue, Tof1-Csm3 in yellow and DNA in grey. (C,D) Structure of the G4 bound in the central chamber of the MCM ring in state 1 (C) and state 2 (D). Densities corresponding to the DNA are shown as grey isosurfaces and contoured at 2.5 σ. (E,F) Surface representation of MCM central chamber in state 1 (E) and state 2 (F) with Mcm4 and Mcm7 removed for clarity.

Upstream of the G4, the leading strand templates in states 1 and 2 are threaded in a right-handed spiral configuration through the C-tier, guided by distinct interactions with the PS1 and H2I hairpin loops (Figure S8). In state 1, the leading strand template is coordinated in the 5’ to 3’ direction by Mcm3, −5, −2 and −6, whereas Mcm4 and −7 do not engage the DNA. In state 2, the leading strand template associates in the 5’ to 3’ direction with Mcm2, −6, −4 and −7, and Mcm3 and −5 are unbound from DNA. In both states, the ssDNA backbone is primarily coordinated by highly conserved lysine and alanine residues in the PS1 loop and serine and valine/isoleucine residues at the base of the H2I loop (Figure S8). Previous structures of yeast, fly, and human CMG bound to replication forks exhibit nearly identical DNA-protein contacts, indicating that the G4-stalled structures correspond to canonical translocation states (28–32, 51). For example, the ssDNA in a structure of yeast CMG-FPC bound to a normal forked DNA (PDB 6SKL), which we will refer to as normal fork conformation 1, is coordinated in a similar manner as the ssDNA in G4 stall state 1. Similarly, the ssDNA in a second conformation bound to a normal fork (PDB 6SKO), which we will refer to as normal fork conformation 2, is coordinated in a similar manner to G4 stall state 2.

Whereas the G4 and the upstream ssDNA adopt distinct conformations in G4 stall states 1 and 2, the conformations of the fork and downstream dsDNA are nearly indistinguishable (Figures 3A–D and Figure S9A). In both states, the lagging strand template is coordinated by the N-terminal OB-fold hairpin loops of Mcm6, −4 and −7 at the fork junction (Figure S9B,C). These interactions guide the final base pair to the separation pin residue, Mcm7 F363 and enable the diversion of the unwound lagging strand template towards the Mcm3 and Mcm5 Zn2+-finger domains. Further downstream of the fork, ~1 turn of dsDNA is coordinated by Tof1-Csm3, which tilts the dsDNA in both states at a ~50° angle relative to the central MCM channel. Notably, the conformations of the fork and downstream dsDNA in states 1 and 2, as well as those of the residues that coordinate them, closely mimic normal fork conformation 1 (Figure S9D) (28) and corroborate the 5’ exonuclease protection data (Figure 2B). The striking similarity of the fork junction in the presence of normal and G4-containing forked DNA indicates that the G4 does not perturb the protein-DNA contacts necessary for DNA unwinding.

The G4 in the leading strand template impedes the transition between CMG translocation states

The C-terminal PS1 and H2I loops of Mcm2–7 create a constriction in the central channel that accommodates the leading strand template during normal CMG translocation but is too narrow to accommodate the folded G4, thus impeding template passage from the N-tier to the C-tier (Figure 4A,B). Steric clashes occur between the G4 and the tips of the H2I and PS1 loops (Figure 4C,D). In state 1, the G4 contacts the H2I loops of Mcm5 and Mcm2, while the G4 in state 2 is oriented towards the H2I loops of Mcm3 and Mcm7.

Figure 4: The MCM PS1/H2I loops sterically block passage of the leading strand template at the G4.

(A,B) Surface representation of the constriction from the central cavity to the MCM C-tier for state 1 (A) and state 2 (B) with DNA shown as cartoon, viewed from the N-tier. (C) Interactions between MCM PS1/H2I loops and the G4 in state 1 (C) and state 2 (D), viewed from the side. (E-H) MCM PS1/H2I loops in G4 stall states 1 (E) and 2 (F) and normal fork conformations 1 (G) and 2 (H). Mcm2 is shown in blue, Mcm6, −4, −3, and −7 are shown in green and Mcm5 is shown in orange.

Despite the different orientations of the G4 and upstream ssDNA in the G4 stall states, the PS1/H2I loops are arranged in a largely planar manner in both states (Figure 4E,F). In contrast, structures of yeast and human CMG-FPC bound to normal forked DNA reveal that translocation of the ssDNA in the MCM C-tier is associated with a rearrangement of the PS1/H2I loops into a spiral configuration (Figures 4G,H and S10A). For example, when the ssDNA is coordinated in normal fork conformation 1 by Mcm3, −5, −2, and −6 in the 5’ to 3’ direction, the PS1/H2I loops adopt a planar ring configuration that is nearly identical to that observed in G4 stall state 1 (Figure 4E,G). In normal fork conformation 2, by contrast, the PS1/H2I loops transition to a spiral configuration as DNA is translocated and coordinated by Mcm2, −6, −4, −7, −3 and −5 (Figure 4H). Aligning the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm5 in normal fork conformations 1 and 2 reveals that the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm2, −6, −4, −7 and −3 reorient in conformation 2 toward the 5’ proximal side of the leading strand template (Figure 4H). The largest movement involves the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm2, which transit ~17 Å between 3’- and 5’-proximal positions along the channel axis, corresponding to a 12 nt translocation of the leading strand template (Figure S11B). The movement of the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm2 in normal fork conformation 2 results in a disruption of the interface between the PS1 loop of Mcm2 and H2 of Mcm5 that is defined by main chain interactions between the highly conserved residues S632 in Mcm2 and G443/S445 in Mcm5 in conformation 1. Equivalent interactions order the remaining MCM interfaces (Figure S10B,C).

The transition from the planar to the spiral state is prevented in the context of a G4, as the Mcm2 PS1/H2I loops clash with the G4 in state 1. The G4 in stall state 2 also establishes an impediment to the spiral-to-planar transition, capturing an intermediate translocation state. In this intermediate state, Mcm5 and −3 have released the DNA at the 3’ end of the spiral and have moved towards the 5’ side of the leading strand template, whereas Mcm2, −6, −4, and partially −7, remain bound to the DNA. However, due to the steric clash between the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm5 and −3 and the G4, these loops fail to reestablish 5’ proximal DNA contacts by reengaging the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm2. This prevents restoration of the normal planar state and stalling in a quasi-planar state instead (Figures 4E and S10D,E).

Our assignment of state 2 as an intermediate in the translocation process implies that the CMG translocates on DNA by alternating between spiral and planar configurations of its DNA-binding PS1/H2I loops. In the planar state, represented by G4 stall state 1 and normal fork conformation 1, the Mcm2 and −5 PS1/H2I loops are physically engaged via conserved mainchain interactions, resulting in a closed-ring conformation. Transition into the spiral state, which corresponds to normal fork conformation 2, involves the breakage of the Mcm2/5 PS1/H2I loop interface and movement of the Mcm2 PS1/H2I loops to reengage with the leading strand template 12 nt downstream in the 5’ direction. The interface between the Mcm6 and −2 PS1/H2I loops remains stable during this transition (Figure S10B,C), resulting in the concomitant movement of the Mcm6 and −2 PS1/H2I loops. The 3’-to-5’ movement of the Mcm2 and −6 PS1/H2I loops propagates across the Mcm4, −7 and −3 PS1/H2I loops, allowing the Mcm4 and −7 PS1/H2I loops to engage DNA and culminating in a spiral configuration stabilized by conserved PS1-H2I interactions between all MCM subunits except Mcm2 and −5. Completion of the translocation cycle would involve a sequence of rearrangements, including a transient state analogous to that in G4 stall state 2, that induce the release of the Mcm5 and −3 PS1/H2I loops from the DNA on the 3’ end of the spiral, re-establishment of the PS1-H2I interface between Mcm2 and −5 at the 5’ proximal end of the spiral, re-engagement of the 5’ proximal DNA by the Mcm5 and −3 PS1/H2I loops and release of the Mcm7 and −4 PS1/H2I loops from DNA, thus re-establishing the planar state.

The proposed translocation mechanism is driven by alternating 12 nt movements of the Mcm2 and −5 PS1/H2I loops and thereby diverges from the previously proposed rotary hand-over-hand mechanism, which postulates a sequential 3’ to 5’ movement of individual MCM subunits or pairs of MCM subunits in 2–4 nt steps around the MCM ring analogous to a circular staircase (29). As discussed below, this mechanism aligns with the asymmetric distribution of ATPase sites essential for CMG helicase activity around the MCM ring, which is more difficult to explain by rotary mechanisms (29, 36).

DNA binding is uncoupled from ATP binding in the C-tier of the stalled CMG-FPC

Previous studies indicated that the position of the ssDNA in the C-tier is defined by the nucleotide-binding state of the AAA+ domains (28–32, 51). However, we note that the nucleotide-bound state of CMG previously determined in the presence of ATP is somewhat ambiguous due to limited resolution of the structures in the vicinity of the ATPase sites (29, 31), while other structures of CMG:DNA were determined in the presence of slowly or non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs, such as ATPγS or AMP-PNP, which perturb the formation of intermediate states associated with ATP turnover (28, 30, 51). Consequently, the detailed mechanism by which ATP turnover is coupled to CMG translocation remains unclear.

To gain insight into this question, we took advantage of the high quality of the cryo-EM maps of G4-stalled CMG obtained in the presence of ATP, which allowed for an unambiguous assignment of active site nucleotide-bound states at each of the six MCM subunit interfaces. In G4 stall state 1, ADP is bound at Mcm2; the remaining ATP-binding sites are occupied by ATP. The arrangement of nucleotides is shifted in G4 stall state 2 with ADP bound at Mcm4 and −6 and ATP bound at Mcm2, −3, −5 and −7 (Figure 5A,B). Notably, the active site configuration at all six AAA+ interfaces in both states 1 and 2 principally corresponds to a catalytically competent state as illustrated by the ordered arrangement of catalytic residues from the Walker A, Walker B and R-finger motifs (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5: Nucleotide-bound state of G4-stalled yeast CMG-FPC.

(A,B) MCM C-tier of state 1 (A) and state 2 (B). Bound ATP molecules are shown as orange spheres, bound ADP molecules are shown as magenta spheres and ssDNAs are shown as grey surfaces. (C,D) MCM C-tier ATPase sites in state 1 (C) and state 2 (D).

Intriguingly, we observe that DNA binding in the C-tier of the G4-stalled CMG-FPC does not strictly correlate with the ATP-bound state of AAA+ domains (Figure S8). For example, Mcm4 and −7 in state 1 and Mcm5 and −3 in state 2 are bound to ATP, but do not engage the leading strand template. Conversely, Mcm2, −6 and −4 engage the leading strand template in states 1 and 2 in either ADP- or ATP-bound form. Moreover, the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm2:ADP in G4 stall state 1 superimpose on those of Mcm2:AMP-PNP in normal fork conformation 1, while the PS1/H2I loops of Mcm6:ADP and Mcm4:ADP in G4 stall state 2 superimpose on those of Mcm6:AMP-PNP and Mcm4:AMP-PNP in normal fork conformation 2. Collectively, this indicates that ATP- and DNA-binding are not strictly coupled. Whether this reflects a canonical translocation mode or is specific for the G4 stall state remains to be determined.

To determine if the PS1/H2I conformational states described above are associated with global changes in the C-tier, we aligned the MCM C-tiers of CMG-FPC in G4 stall states 1 and 2 on the Mcm5 AAA+ domain. In line with the co-planar arrangement of the PS1/H2I loops in both G4 stall states, the C-tier remains relatively rigid between states 1 and 2 (Figure S11A). This contrasts the rearrangement of the AAA+ domains in CMG-FPC bound to normal forked DNA, which are arranged in a co-planar manner in conformation 1 but adopt a spiral configuration in conformation 2, with Mcm2 and −5 marking the endpoints of the spiral (Figure S11B). The Mcm2 AAA+ domain undergoes the largest change, shifting by ~ 17 Å, while Mcm6, −4, −7 and −3 incur progressively smaller shifts, mirroring the co-axial movement of the corresponding PS1/H2I domains. Previous studies also observed rigid body movements of the C-tier, involving the tilting and rotation of the C-tier relative to the N-tier (28, 32, 37). Alignment of G4 stall states 1 and 2 on the N-tier demonstrates that the C-tier is significantly less dynamic in CMG stalled at the G4 (Figure S11C).

The molecular basis for G4-induced fork arrest is conserved in the human replisome

We next investigated if the mechanism of replisome arrest by G4s is broadly conserved by characterizing the G4-induced fork block using a reconstituted human DNA replication system analogous to that described recently (52). Specifically, replisomes reconstituted from purified human CMG (hCMG), CLASPIN, TIM-TIPIN, AND-1, Pol α, Pol δ, Pol ε, RPA, RFC, PCNA and CTF18-RFC (Figure S12A) were assembled in the presence of a low concentration of AMP-PNP on forked DNA templates harboring a preformed G4 1.9 kbp downstream of the fork junction, followed by the induction of fork progression by adding excess ATP. Analogous to our observations in the yeast system, we find that a single G4 in the leading strand template induces efficient fork stalling, while a G4 in the lagging strand template does not measurably affect fork progression (Figure 6A,B). As before, a background of stalled leading strand products is observed on templates harboring a DNA insert due to the retention of nicks in the DNA during template preparation. These background products are not observed on a linear control template prepared without insertion of a DNA fragment by ligation (“un-scarred”). Thus, a single G4 specifically in the leading strand template is a potent block to both yeast and human replisomes.

Figure 6: The G4 stall mechanism is conserved in the human replisome.

(A) Denaturing (bottom) and native (top) agarose gel analysis of replication products obtained in the reconstituted human system on DNA templates harboring a G4 on the leading strand template (lanes 1–3) or a G4 on the lagging strand template (lanes 4–6). A random B-form DNA fragment was ligated into the template in lanes 7–9, while no fragment was inserted into the template in lanes 10–12. * indicates position of leading strand products resulting from replisome run-off at template nicks, which coincide with stalled products. (B) Schematic of replication products obtained in (A). (C) Cryo-EM density map of human CMG-FPC stalled at G4 colored by subcomplex. (D) Structure of the G4 bound in the central chamber of the MCM ring. Density corresponding to the DNA is shown as a grey isosurface and contoured at 2.5 σ. (E) Interactions between MCM PS1/H2I loops and bound G4, viewed from the side. (F) Surface representation of MCM central chamber with MCM4 and MCM7 removed for clarity (G) Surface representation of the access to the MCM C-tier with DNA shown as cartoon, viewed from the N-tier. (H) MCM C-tier with bound ATP molecules shown as orange spheres, bound ADP molecules shown as magenta spheres and ssDNAs shown as a grey surface.

To determine the structural basis for the G4-induced block to human replisome progression, we characterized human CMG-FPC stalled at a leading strand G4 by cryo-EM. Human CMG-FPC complexes were assembled in the presence of AMP-PNP on forked DNA templates harboring a preformed prototypical G4 in the leading strand template, 24 bp downstream of the fork junction. DNA unwinding was induced by adding excess ATP. After an incubation time of 10–30 minutes, reactions were vitrified without the addition of chemical crosslinking agents. Image analysis yielded a single conformational state at a global resolution of 2.6 Å that was improved to 2.4 – 2.6 Å using focused refinements (Figures 6C and S6C). The DNA is well-defined and can be unambiguously modeled, revealing that the G4 has entered the central channel of hCMG and is blocked from entering the C-tier at the N-tier/C-tier interface (Figure 6D–G). Remarkably, nearly all of the features resolved in yeast G4 stall state 1 are recapitulated in the DNA of G4-stalled hCMG, including the conformation of the G4 in the central channel, the coordination of the upstream ssDNA and the coordination of the downstream fork junction (Figure S12B,C). Both the arrangement of the PS1/H2I domains (Figure S12D) and ATPase site occupancy (Figure 6H) of yeast G4 stall state 1 are also identical in hCMG. Notably, no density for TIM-TIPIN is observed, suggesting a weaker association of the FPC with hCMG than with yCMG. However, we note that the TIM-TIPIN complex is present at stalled hCMG complexes as determined by 5’ exonuclease protection assays (Figure S12E), indicating that FPC binding to hCMG is destabilized under cryo-EM conditions.

Collectively, the data demonstrate that in both yeast and human systems, the G4 passes the FPC at the front of the replisome and the fork junction inside the N-tier, but is blocked from entering the C-tier by steric clashes with PS1/H2I pore loops. CMG is, therefore, arrested by restriction of its internal protein dynamics by the stable secondary structure of the G4.

Discussion

We demonstrate that even a single G4 can create a strong steric block inside the CMG central channel. This provides physical evidence for the replisome blocking potential of G4s, which is often assessed in the presence of G4-stabilizing ligands. Moreover, while G4 stability may be modulated by G4-binding proteins in cellular and extract-based approaches, our utilization of fully reconstituted systems demonstrates that the impact of single G4s on fork progression is intrinsic to the G4 structure. Given the prevalence of potential G-quadruplex sequences (PQSs) across eukaryotic genomes (53, 54), this demonstrates that G4s must be continuously turned over during S phase to allow unhindered fork progression, emphasizing the importance of specialized cellular mechanisms to limit G4 formation and maintain genome stability (18).

Our data demonstrate that G4-induced blocks to replisome progression occur specifically at preformed G4s in the leading strand template, consistent with the bypass of lagging strand steric blocks by the CMG helicase (27, 55). The internalization of the G4 by the CMG has implications for potential fork restart mechanisms by sequestering the G4 away from G4-controlling proteins. Additionally, the fork’s canonical configuration may protect the replisome from ubiquitin-mediated disassembly (56), suggesting that replisome disassembly is not the mechanism for exposing G4s for helicase processing. A previous study in Xenopus showed that DHX36, a 3’−5’ helicase, can promote replisome bypass of a leading strand G4 (6), but this requires prior binding of DHX36 to the G4, conflicting with a fork restart model. Alternatively, 5’−3’ helicases like Pif1 in yeast (57, 58) and FANCJ in humans (7, 59, 60) may facilitate replisome bypass of G4s, analogous to RTEL1-mediated replisome bypass of DNA-protein crosslinks (DPCs) (61), though their role in reactivating stalled forks remains unclear. The methods developed here can help address this.

Unexpectedly, our analysis of the CMG stall mechanism has yielded evidence in support of a novel, helical inchworm CMG translocation mechanism that deviates from rotary hand-over-hand mechanisms suggested by current models (29, 35). We find that all previously published CMG structures from diverse organisms in complex with normal forked DNA broadly fall into two classes of PS1/H2I loop conformations: planar or spiral, with the major conformational change occurring at the Mcm2/5 interface (28–32, 51). The recurrence of these states across diverse systems indicates that the planar and spiral states of the PS1/H2I loops correspond to thermodynamically stable states of CMG when bound to DNA. A reaction coordinate connecting these two states is, therefore, predicted to be populated by an ensemble of high-energy intermediate states that have been too rare to resolve in previous structural analyses. The conformation of G4 stall state 2 reported here is consistent with this interpretation, suggesting that the G4 allowed capture of one such transient intermediate.

The translocation can be described as follows (Figure S13): Starting from the planar state (i), Mcm6, −2, −5 and −3 coordinate DNA at nucleotide positions 1+2, 3+4, 5+6 and 7+8, respectively, in the 3’−5’ direction. Mcm7 and −4 do not contact the DNA, leaving positions 9+10 and 11+12 unoccupied. Transition into the spiral state (ii) involves the disruption of the Mcm2/5 PS1-H2 interface and movement of the Mcm6 and −2 PS1/H2I loops towards the 5’ proximal end of the DNA to engage nucleotides 13+14 and 15+16, respectively, while Mcm5 and −3 remain bound to the DNA on the 3’ proximal end of the spiral. The planar-to-spiral rearrangement allows the Mcm7 and −4 PS1/H2I loops to engage base positions 9+10 and 11+12, respectively. Sequential binding of the Mcm7, −4, −6, and −2 PS1/H2I loops to DNA likely determines the step sizes of MCM subunits during the planar-to-spiral transition. Notably, the 12 nt steps for Mcm2 and −6 between states (i) and (ii) translate into an 8 nt 3’−5’ advance by the CMG, which coordinates nucleotide position 8 via Mcm3 in the planar state (i) and position 16 via Mcm2 in the spiral state (ii) at the 5’ proximal end of the DNA. Next, Mcm5, −3, −7, and −4 sequentially dissociate from nucleotide positions 5–12 and move in 3’ to 5’ direction to reestablish the planar conformation. An intermediate stage of this rearrangement, captured in G4 stall state 2, involves the dissociation of nucleotide positions 5–9 from the Mcm5, −3, and −7 PS1/H2I loops and the approach toward the Mcm2 PS1/H2I loops by those of Mcm5 (iii). Completion of the cycle involves the restoration of the Mcm2/5 PS1-H2 interface and engagement of nucleotide positions 17+18 and 19+20 by Mcm5 and −3, respectively, whereas the Mcm7 and −4 PS1/H2I loops remain dissociated from DNA (iv). The Mcm6 and −2 PS1/H2I loops remain bound at positions 13+14 and 15+16, respectively, throughout this transition. Consequently, the 12 nt advancement by the trailing two subunits, Mcm3 and Mcm5, places them downstream of Mcm2 and contributes 4 nt to the total 3’-to-5’ advancement. Together with the initial 8 nt step headed by Mcm2, CMG thus advances 12 nucleotides in one complete translocation cycle.

We suggest that the restructuring of the Mcm2/5 interface is in part mediated by ATP turnover in the Mcm5 ATP-binding site, which is consistent with active site residues in Mcm5 being essential for CMG helicase activity (36). In our model, ATP-binding to Mcm5 establishes the Mcm2/5 PS1-H2I interface, while ATP-hydrolysis or product release would disengage Mcm2 PS1 from Mcm5 H2I. This agrees with the observation that Mcm5 is occupied by AMP-PNP or ATP in the planar states of CMG bound to normal forks or stalled at a G4, respectively, but nucleotide-free in the spiral state of normal fork conformation 2 (28). Mutational analyses demonstrate that ATP turnover by Mcm3 and −7, which follow Mcm5 in the MCM ring, also drive CMG helicase activity, while the remaining ATPase sites are not essential for DNA unwinding (29, 36). We hypothesize that the clustering of critical ATPase sites on one side of the Mcm2/5 interface drive the asymmetric structural rearrangements associated with the proposed planar-to-spiral transitions.

The CMG translocation mechanism introduced here is unprecedented among hexameric helicases, which are thought to operate either by rotary or concerted mechanisms (33, 34). However, we note that our model bears similarity to an earlier “pump-jack” model (37). Moreover, our model is analogous to the helical inchworm model proposed for the phi29 genome packaging motor, a distantly related homopentameric ATPase (62, 63). Based on this analogy, we predict that DNA translocation by CMG occurs in bursts, involving successive 8 and 4 nt DNA unwinding steps. Careful kinetic analyses will be required to validate this prediction. Furthermore, we expect that approaches established here will facilitate the capture of additional intermediate CMG translocation states in future structural studies.

Materials and Methods

Protein purification

Yeast proteins

Yeast replication proteins were purified as described previously (5, 43, 64, 65).

Human proteins

hCMG, hPol ε, AND-1, CLASPIN, TIM-TIPIN, hPol δ and hPol α were purified from insect cells using the biGBac baculovirus expression system (66). Hi5 cells were infected at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells per mL and incubated for 72 h (unless indicated otherwise) post infection.

hRFC and CTF18-RFC were purified after overexpression in budding yeast cells. hPCNA and hRPA were purified after overexpression in E. coli. Open reading frames (ORFs) were codon-optimized for expression in the respective expression system. For expression in yeast, proteins were expressed from galactose inducible expression vectors stably integrated into the genome. 12 L of cells were grown at 30 °C in YP-GL (YP + 2% glycerol + 2% lactic acid) to a density of 2–4 × 107 cells/mL. Galactose was then added to a final concentration of 2% and incubation was continued for an additional 4 hours before harvesting the cells by centrifugation. The cell pellet was washed once with 200 mL of ice cold 1 M sorbitol /25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6 followed by a wash with 50 mL of respective lysis buffer. Cells were then resuspended in half of the volume of lysis buffer and frozen dropwise in liquid nitrogen. Frozen cell popcorn was stored at −80 °C until further processing. Frozen popcorn was crushed in a freezer mill for six 2-min cycles at a rate of 15 impacts per second. Crushed cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm for 45 min (T647.5 rotor). Purified proteins were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

hCMG purification

The cell pellet obtained from 1 L of Hi5 cells was resuspended in 200 mL of hCMG lysis buffer (45 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/300 mM KCl/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Once resuspended, cells were lysed via sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble phase was incubated with 1 mL of pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG beads at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed with 30 column volumes (CV) of hCMG lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 1 CV of hCMG lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL FLAG peptide via gravity flow followed by 2 CV supplemented with 0.25 mg/mL FLAG peptide. FLAG eluates were pooled and incubated with 0.5 mL Strep-Tactin Superflow beads at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were washed with 20 CV of lysis buffer and the bound proteins were eluted with 8 × 1 CV of hCMG lysis buffer supplemented with 30 mM biotin. Peak fractions containing protein were pooled and diluted with an equal volume of hCMG lysis buffer without KCl prior to fractionation on MiniQ PC 3.2/3 column with a salt gradient of 150 – 1000 mM KCl over 30 CV. Peak fractions from the MonoQ step were pooled and dialyzed against CMG storage buffer (45 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/ 200 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM DTT). hCMG yield was around 0.3 mg per L of insect cell culture.

hPol ε purification

The cell pellet from 0.5 L of infected Hi5 culture was resuspended in 100 mL of Pol ε lysis buffer (40 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/100 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed via sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was incubated with 1 mL of with pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG beads at 4°C for 3 h. The beads were washed with 30 CV of Pol ε lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 1 CV of Pol ε lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL FLAG peptide via gravity flow followed by 2 CV supplemented with 0.25 mg/mL FLAG peptide. FLAG eluates were pooled and fractionated on a MonoQ 5/50 column with a salt gradient of 150 – 600 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fractions from the MonoQ step were pooled and spin concentrated (Amicon Ultra 30K centrifugal filters) prior to fractionation on a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated in Pol ε storage buffer (40 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/200 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT). The final yield was around 0.28 mg of protein from 0.5 L of insect cell culture.

AND-1 purification

The cell pellet from 0.5 L of infected Hi5 culture was resuspended in 100 mL of AND-1 lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/300 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed by sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was incubated with 0.5 mL of pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG beads at 4°C for 2 hours. The beads were washed with 20 CV of AND-1 lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 1 CV of AND-1 lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL FLAG peptide via gravity flow followed by 2 CV supplemented with 0.25 mg/mL FLAG peptide. FLAG eluates were pooled and diluted with an equal volume of AND-1 lysis buffer without NaCl and fractionated on a MonoQ 5/50 column using a salt gradient of 150 – 1000 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fractions from the MonoQ step were pooled and concentrated (Amicon Ultra 30K centrifugal filters) prior to fractionation on a Superdex 200 10/300 column pre-equilibrated with AND-1 storage buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/200 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT). The yield was around 0.15 mg protein from 0.5 L of insect cell culture.

CLASPIN purification

0.5 L of Hi5 cells at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells per mL were infected with CLASPIN baculovirus and the cells were collected 66 h after infection. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 mL of CLASPIN lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH-7.2/150 mM KCl/5 % glycerol/0.01 % NP40S/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). The cells were lysed via sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was incubated with 0.5 mL of pre-equilibrated Strep-Tactin Superflow beads at 4°C for 3 hours. The beads were washed with 40 CV of CLASPIN lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 8 CV of CLASPIN lysis buffer supplemented with 30 mM biotin via gravity flow. Eluates were pooled and concentrated (Amicon Ultra 30K centrifugal filters) prior to fractionation on a Superose 6 10/300 gel filtration column pre-equilibrated in CLASPIN storage buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/200 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT). The protein yield was around 0.1 mg per 0.5 L of insect cell culture.

TIM-TIPIN purification

50 mL of Hi5 cells were infected at a density of 2.5 × 106 per mL and collected 72 hours post-infection and pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 rpm in a swinging bucket rotor at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 20 mL of TIM-TIPIN lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.2/0.01% NP40-S/5% glycerol/150 mM KCl/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed via ultra-sonication pulses of 10 s on and 30 s off for 12 cycles and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was passed over 400 μL of pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG bead at 4°C. The beads were washed with 40 CV of TIM-TIPIN lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 2 CV of TIM-TIPIN lysis buffer supplemented with 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide and mixing on hot-dog roller for 15 min at 4°C, followed by 2 CV supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL FLAG peptide. FLAG eluates were pooled and applied onto a 1 mL MonoQ column equilibrated in TIM-TIPIN lysis buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with a salt gradient of 150 – 1000 mM KCl applied over 20 CV. Peak fractions from the MonoQ column were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-0.5 (30 kDa cutoff) filter (Millipore-Merck) prior to fractionating on a 24 mL Superdex 200 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated with 25 mM Tris pH-7.2/150 mM NaCl/5 % glycerol/0.01 % NP40S/1 mM DTT. The peak fractions were concentrated on an Amicon Ultra-0.5 (30 kDa cutoff) filter (Millipore-Merck) before storage at −80 °C. The yield of purified TIM-TIPIN complex was around 0.31 mg from 50 mL of insect cell culture.

hPol δ purification

The cell pellet from 1 L of infected Hi5 cells was resuspended in 200 mL of Pol δ lysis buffer (30 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5/300 mM NaCl/0.03% NP-40S/6% glycerol/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed via sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was incubated with 1 mL of pre-equilibrated Strep-Tactin Superflow beads at 4°C for 3 hours. The beads were washed with 40 CV of Pol δ lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 8 CV of Pol δ lysis buffer supplemented with 30 mM biotin via gravity flow. The eluates were pooled and diluted to bring the NaCl concentration to 100 mM and supplemented with 0.5 mM ATP and 5 mM magnesium chloride, and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, the eluate was applied onto a 1 mL Capto HiResQ column equilibrated in 50 mM Tris pH-8.0/10 % glycerol/0.01 % NP40-S/100 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT. Bound protein was eluted by applying a gradient of 100 – 1000 mM NaCl over 30 CV. Peak fractions were pooled, supplemented with 0.5 mM ATP and 5 mM magnesium chloride, incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C, concentrated in a spin concentrator, and fractionated on a 24 mL Superdex 200 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated with 25 mM Tris pH-7.2/150 mM NaCl/10 % glycerol/0.005 % Tween 20/1 mM DTT. The peak fractions were concentrated on a spin concentrator before storage at −80 °C. The final yield for hPol δ was around 0.15 mg of protein per 1 L of insect cell culture.

hPol α purification

The cell pellet from 1 L of infected Hi5 cells was resuspended in 200 mL of Pol α lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5/10% glycerol/0.02% NP40-S/300 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed via sonication for 2 min (12 cycles of 10 s on, 20 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 42,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min. The soluble extract was incubated with 1 mL of pre-equilibrated Strep-Tactin Superflow beads for 4 h at 4°C. The beads were washed extensively with 30 CV of Pol α lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 8 CV of Pol α lysis buffer supplemented with 30 mM biotin via gravity flow. Eluates were pooled and diluted gradually with two volumes of Pol α lysis buffer without NaCl and fractionated on a Capto HiResQ 5/50 column using a salt gradient of 100 – 1000 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fractions from the Capto HiResQ 5/50 step were pooled and concentrated (Amicon Ultra 30K centrifugal filters) prior to fractionation on a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated in Pol α storage buffer (25 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5/10% glycerol/0.02% NP40-S/200 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT). The final yield was around 0.15 mg of purified hPol α per 1 L of insect cell culture.

hRFC purification

Crushed cell powder was thawed and an equal volume of RFC lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.6/20% sucrose/5 mM magnesium acetate/0.02% NP40-S/0.02% Triton X-100/0.5% inositol/1 mM ATP/300 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific), was added to resuspend the lysate. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 45 min and the soluble extract was incubated with 1 mL of pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG beads for 2 hours at 4°C for 2 hours. The beads were washed extensively with 15 CV of RFC lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 1 CV of RFC lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL FLAG peptide via rotation on hot dog roller for 10 min) followed by 2 CV supplemented with 0.25 mg/mL FLAG peptide. Eluates were pooled and the FLAG affinity tag was cleaved by incubation with 10-fold molar excess of TEV protease overnight at 4°C. The salt concentration of the protein sample was lowered to 200 mM NaCl by gradually adding RFC lysis buffer without NaCl prior to fractionation on a MonoS 5/50 column using a salt gradient of 200 – 1000 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed against RFC lysis buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and fractionated on a HiTrap Heparin HP(1 mL) column using a gradient of 200– 1000 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed against RFC storage buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.6/20% sucrose/5 mM magnesium acetate/0.02% NP40-S/0.02% Triton X-100/0.5% inositol/1 mM ATP/300 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT) prior to storage. The protein yield was around 1 mg of purified hRFC per 12L of yeast cells.

CTF18-RFC purification

Crushed cell powder was thawed and an equal volume of CTF18 lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.6/10% glycerol/0.02% NP40-S/1 mM EDTA/1 mM EGTA/150 mM KCl/1 mM DTT), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific), was added to resuspend the lysate to homogeneity. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm (T647.5 rotor) for 30 min and the soluble extract was passed through 1 mL of pre-equilibrated M2 agarose anti-FLAG beads at 4°C using an Econo Pump (Bio-Rad). The beads were washed extensively with 15 CV of CTF18 lysis buffer. Bead-bound protein was eluted with 3 CV of CTF18 lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL FLAG peptide (via rotation on hot dog roller for 10 min) followed by 2 CV of lysis buffer. Eluates were pooled and fractionated on a MonoQ 5/50 column using a salt gradient of 150 – 1000 mM KCl over 20 CV. Peak fraction from the MonoQ step was fractionated on a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated with CTF18 storage buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/1 mM EDTA/1 mM EGTA/300 mM potassium acetate/1 mM DTT). The final yield for CTF18-RFC was around 2.5 mg of protein per 12 L of yeast cells.

hPCNA purification

BL21-Codonplus DE3 (RIL) cells (Agilent Technologies) were freshly transformed with the PCNA expression construct. 1 L of cells were grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.6, cooled on ice for 20 min and ethanol was added to a final concentration of 2%. Expression was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG and incubation continued at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min and the cell pellet was stored at −80°C until further processing. The cell pellet was thawed and resuspended in 50 mL of PCNA lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.6/400 mM NaCl/10 mM imidazole/1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and 0.1 mg/mL of lysozyme. Cells were lysed via sonication 1.5 min (3 cycles of 30 s on, 90 s off) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 12,000 rpm (SS34 rotor). The soluble phase was passed over 2 mL of equilibrated Ni2+-NTA agarose resin via gravity flow in a disposable column. Beads were washed with 15 CV of PCNA wash buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA/150 mM NaCl/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/10 mM imidazole/1 mM DTT). Bead-bound protein was eluted with 6 CV of PCNA elution buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA/150 mM NaCl/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/200 mM imidazole/1 mM DTT). Eluates were pooled and fractionated on a MonoQ 5/50 column using a salt gradient of 150 – 1000 mM NaCl over 20 CV. Peak fraction from the MonoQ step was fractionated on a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated in PCNA storage buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA/300 mM potassium acetate/0.02% NP40-S/10% glycerol/1 mM DTT). The protein yield was around 8 mg of purified hPCNA per 1 L of cells.

hRPA purification

The RPA expression plasmid, p11d-tRPA, was a gift from Marc Wold (University of Iowa). RPA was purified as reported previously (67). 8 L of BL21-Codonplus DE3 (RIL) transformed with RPA expression plasmid were grown at 37 °C to OD600 = 0.8. RPA expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG and continued incubation for 3 h. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 130 mL of 30 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5/5 mM DTT/1 mM EDTA/0.5% inositol/1 mM PMSF/0.02% Tween 20/50 mM KCl and protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were lysed by three passages through a French Press at 20,000 psi and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation in a T647.5 rotor at 30,000 rpm for 40 min. One-third of the supernatant (fraction 1) was diluted with 2.5 volumes of Buffer J (30 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5/5 mM DTT/1 mM EDTA/0.5% inositol/0.02% Tween 20/10% glycerol) + 50 mM KCl and loaded onto a 100 mL Affi-Gel Blue column equilibrated in the same buffer. The column was washed with 3 CV equilibration buffer, 3.5 CV Buffer J + 900 mM KCl, and 3 CV Buffer J + 50 mM KCl and 0.5 M NaSCN. Protein (fraction 2) was eluted with Buffer J + 1.5 M NaSCN. Fraction 2 was loaded onto an 11 mL column of hydroxyapatite (BioRad MacroPrep) equilibrated with Buffer J + 50 mM KCl and the column was washed with 2 CV of equilibration buffer, 2 CV of Buffer J + 800 mM KCl, and then 2 CV of equilibration buffer. Protein (fraction 3) was eluted with Buffer J + 50 mM KCl and 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5). Fraction 3 was diluted with Buffer J + 30 mM KCl to a conductivity equivalent to Buffer J + 100 mM KCl and loaded onto a 1 mL Mono-Q column equilibrated in Buffer J + 50 mM KCl. The column was washed with 4 CV of equilibration buffer and 4 CV Buffer J + 100 mM KCl. Protein was eluted with a 20 CV gradient of 200 to 400 mM KCl in Buffer J. hRPA (fraction 4) was pooled based on SDS-PAGE. Fraction 4 (3.3 mg/ml, 2.8 mL) was aliquoted, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C.

DNA templates

DNA templates for use in the reconstituted yeast DNA replication system

DNA templates were generated by ligating small oligonucleotide inserts containing a pre-formed G4 structure into the ARS305-containing plasmid p1400. p1400 was linearized by digestion with BbsI and XcmI to generate non-complementary overhangs. The linearized plasmid DNA was isolated by fractionation on a 10–40 % sucrose gradient (36 mL volume) prepared in 20 mM Tris pH-7.6/1 M NaCl/1 mM EDTA. Gradients were centrifuged for 20 h at 27,000 rpm and 20 °C in an AH-629 swinging bucket rotor (Thermo Scientific). Peak fractions corresponding to the linearized form of p1400 were concentrated and buffer-exchanged to 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/1 mM EDTA (1xTE) using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filters (10 kDa cutoff; Millipore-Merck).

Inserts harboring a pre-formed G4 were generated by annealing PAGE purified, 5’-phosphorylated oligonucleotides (Table S1). Oligonucleotides were electrophoresed on 10 % urea polyacraylamide gels and extracted using the crush-and-soak method (45). Complementary oligonucleotides (10 μM each) were mixed in 500 μL of 20 mM Tris pH-8.0/ 25 mM potassium chloride/10 mM magnesium chloride and annealed by heating to 95 °C for 5 min, followed by cooling to 10 °C at a rate of 1 °C/minute in a thermocycler. Annealed products were electrophoresed on 8 % (39:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) native polyacrylamide gels, excised from the gel and eluted from the gel slices by soaking overnight at 4 °C in 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/50 mM potassium acetate/1 mM EDTA. Ligations were performed similarly as described previously (68). Each ligation reaction was carried out in a volume of 80 mL containing 0.5 nM linearized p1400, 1.5 nM purified insert and 50 mM Tris pH-7.6/10 mM magnesium chloride/2.5 μg/mL BSA/0.1 mM ATP/1 mM DTT and 8000 units of T4 DNA ligase. Reactions were incubated overnight at 16 °C. Subsequently, ligation reactions were concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 filter (Millipore-Merck). Re-circularized supercoiled plasmid from each ligation mixture was separated using cesium chloride ultracentrifugation. For this, concentrated ligation reactions (700 μL) were reconstituted into cesium chloride in 6 mL tubes, using a cesium chloride solution prepared by dissolving 12 g cesium chloride in 10.7 mL of 1xTE and supplemented with 0.8 mg ethidium bromide. The tubes were ultracentrifuged in a TV-1665 (Thermo Scientific) vertical rotor at 60,000 rpm for 16 h at 4 °C. The supercoiled plasmid DNA band was recovered by aspiration, extracted 3 times with butanol, concentrated and buffer-exchanged into 1xTE using Amicon Ultra-0.5 (3 kDa cutoff) filters (Millipore-Merck).

DNA templates for use in reconstituted human DNA replication system

Forked DNA templates for human replication assays were designed similarly as described previously (69). The templates were prepared in two steps: 1) Preparation and isolation of circularized plasmid with G4 inserts similar to the yeast replication templates. 2) Linearization of the circular plasmid to asymmetrically position the G4 structures between the termini, followed by ligation of forked DNA to one end. BstXI and AfeI sites were introduced into p1400 to serve as sites of linearization and fork ligation. This modified vector, p1432, was first linearized with BbsI and XcmI, followed by ligation of a G4 insert (Table S1) as described above for the yeast replication templates. Purified supercoiled plasmids with pre-formed G4 structures were subsequently linearized with BstXI and AfeI. These linearized G4 fragments with one cohesive end were purified by 10–40 % sucrose gradient centrifugation (2.2 mL tubes) in 20 mM Tris pH-7.6/1 M NaCl/1 mM EDTA. Centrifugation was carried out at 53,000 rpm for 4 hours at 20 °C in a TLS55 swinging bucket rotor (Beckman Coulter). Peak fractions corresponding to the linearized G4-containing vector DNA were concentrated and buffer-exchanged to 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/1 mM EDTA (1xTE) using Amicon Ultra-0.5 (3 kDa cutoff) centrifugal filters (Millipore-Merck). The isolated linear vector DNA was ligated to a forked DNA molecule with complementary overhangs to BstXI site, prepared by annealing PAGE-purified oligonucleotides (Table S2). 100–150 μL ligation reactions were performed overnight with 2,000 units of T4 DNA ligase (NEB) at 16 °C in NEBuffer r2.1 (NEB) supplemented with 1 mM ATP. Reactions included 5–10 pmol of linearized G4-containing vector DNA and a 10-fold molar excess of fork DNA. Subsequently, T4 DNA ligase was heat-inactivated at 65 °C for 10 min and ligation reactions were treated with 30 units of AfeI to monomerize fork dimers blunt-ligated at their distal ends. Monomerized fork templates were purified again on 10–40 % sucrose gradients (2.2 mL tubes), centrifuged for 4 hours at 53,000 rpm and 20 °C in a TLS55 swinging bucket rotor (Beckman Coulter). Fractions corresponding to monomeric forked DNA templates were pooled, concentrated and buffer exchanged to 1xTE using Amicon Ultra-0.5 (3 kDa cutoff) filter (Millipore-Merck).

DNA substrates for helicase and 3’ exonuclease protection assays

Templates were prepared by annealing PAGE purified oligonucleotides (Table S3) with one of the complementary oligonucleotides being 5’ radiolabeled. The G4-containing tracking strand was radiolabeled for the 3’ exonuclease protection assay, whereas the non-G4 strand was radiolabeled for the helicase assays. Oligonucleotide (0.25 μM) was radiolabeled in a 15 μL reaction containing 0.5 μM [γ−32P] ATP, 10 units of T4 PNK (NEB) for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by heat inactivation at 80 °C for 20 min. Reactions were supplemented with 50 mM potassium acetate and 1.5 times molar excess of complementary oligonucleotide (Table S3). Annealing was carried by heating the mixture to 95 °C for 5 min, followed by cooling to 10 °C at a rate of 1 °C/min using a thermocycler. Annealed products were separated on 8 % (39:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) native polyacrylamide gels, excised from the gel and eluted from the gel slices by soaking overnight in 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/50 mM potassium acetate/1 mM EDTA.

DNA template for 5’ exonuclease protection assay

The tracking strand was prepared by RNA splint-ligation of two oligonucleotides and subsequently annealed to the complementary non-tracking strand. All oligonucleotides, except the RNA oligonucleotide, were PAGE purified as described above. A 43 nt long oligonucleotide (2970) that corresponds to the 3’ portion of the tracking strand is first radiolabeled at its 5’ end. For this, oligonucleotide (1 μM) is radiolabeled in a 30 μL reaction containing 0.5 μM γ-[32P]-ATP and 10 units of T4 PNK (NEB) for 1 hour at 37 °C. The reaction is subsequently supplemented with 25 μM ATP and incubated for another 30 minutes to phosphorylate the remaining 5’ ends, followed by heat inactivation of T4 PNK. The reaction mix is then supplemented with 10 mM potassium chloride, 1.5 times molar excess of a second oligonucleotide (2990) that corresponds to the 5’ part of the tracking strand and 2.5 times molar excess of an RNA oligonucleotide (2973). The three oligonucleotides were annealed, resulting in an RNA-DNA hybrid juxtaposing the 5’ labeled phosphate of 2970 to the 3’ end of 2290. This juxtaposition of 2990 and 2970 is equivalent to full-length tracking strand (2883) with a nick opposite the complementary RNA oligonucleotide that was sealed by addition of 50 units of SplintR ligase (NEB) and incubation for 4 h at 25 °C. The RNA oligonucleotide was subsequently degraded by addition of 50 pmoles of yeast RNase H1 and 20 μg RNase A (Themo Scientific) at 30 °C for 1 hour. The final reaction volume was 40 μL. The complementary non-tracking strand (2884) was added to the reaction mix containing and annealed by heating the reaction to 95 °C and slow cooling to 10 °C at a rate of 1 °C/min in a thermocycler. The reaction mixture was supplemented with 0.5 % SDS and treated with 0.8 units of Proteinase K (NEB) for 1 hour at 37 °C. Templates were separated on 8 % (39:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) native polyacrylamide gels, excised from the gel and eluted from the gel slices by soaking the gel slices overnight in 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/50 mM potassium acetate/1 mM EDTA.

DNA template for cryo-EM analysis

Templates were prepared by annealing PAGE purified oligonucleotides and extracting the annealed products from native polyacrylamide gels. Complementary oligonucleotides (2883 and 2884, 20 μM each) were mixed in 500 μL of 20 mM Tris pH-8.0/25 mM potassium chloride/10 mM magnesium chloride and annealed by heating to 95 °C for 5 min, followed by cooling to 10 °C at a rate of 1 °C/min in a thermocycler. Annealed products were electrophoresed on 8 % (39:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) native polyacrylamide gels, excised from the gel and eluted from the gel slices by soaking the gel slices overnight in 10 mM Tris pH-8.0/50 mM potassium acetate/1 mM EDTA. The DNA was concentrated to a final concentration of 50 – 100 μM using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 (3 kDa cutoff) filter (Millipore-Merck).

3’ exonuclease protection assay

Fifty microliter reactions containing 4 nM template DNA, 20 nM CMG, 20 nM Csm3-Tof1 and 20 nM Mrc1 were assembled in helicase buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/100 mM potassium acetate/10 mM magnesium acetate/0.1 mg/mL BSA/2.5 mM DTT) and were incubated with 0.1 mM AMP-PNP for 30 min at 30 °C. 25 units of Exonuclease T (NEB) were added to the reaction and incubation continued for another 5 min. A 10 μL aliquot that was withdrawn and added to 90 μL of stop buffer (0.5 % SDS/20 mM EDTA/100 mM sodium chloride/125 μg/mL tRNA) served as the 0-minute time point. The remaining reaction was mixed with an equal volume of 10 mM ATP in helicase buffer and 20 μL aliquots were withdrawn at 2, 10, 30 and 50 minute incubation times and reactions stopped by addition of 80 μL of stop buffer followed by extraction with Tris-saturated phenol/chloroform solution (Acros). Aqueous phase contents were ethanol precipitated, rinsed with 70 % ethanol and dried in a rotary dry-vac. The pellets were resuspended in 12 μL of 33 mM NaOH/50 % (v/v) formamide, heated to 95 °C for 5 min and snap-chilled on ice. Reaction products were electrophoresed on 6 % or 8 % urea polyacrylamide sequencing gels in 1xTBE. Gels were dried on a Whatman sheet, exposed to phosphor-imager and scanned on Typhoon IP scanner (Cytiva). Experiments were repeated in three biological replicates.

5’ exonuclease protection assay

Reactions were carried out in 40 μL of helicase buffer containing 4 nM template DNA and either 20 nM CMG (yeast or human) or a mixture of CMG, Csm3-Tof1/TIM-TIPIN and Mrc1/CLASPIN. The protein/DNA mixtures were incubated for 30 min in helicase buffer with 0.1 mM AMP-PNP, either at 30 °C in the case of the yeast proteins or at 37 °C in the case of the human proteins. Prior to the addition of ATP, 10 units of T5 exonuclease (NEB) or 22 units of a 5’ exonuclease concoction [4 units T7 exonuclease (NEB), 12 units RecJf (NEB), 4 units Exonuclease VIII, truncated (NEB), 2 units T5 exonuclease (NEB)] were added to a 20 μL reaction aliquot and incubation continued for 5 min at 30 °C or 37 °C, respectively. The exonuclease reaction was stopped by addition of 80 μL of stop buffer. The remaining 20 μL reaction was mixed with an equal volume of 10 mM ATP in helicase buffer and treated with either T5 exonuclease or 5’ exonuclease concoction, as above, after 30 min post-ATP addition. Reactions were stopped by addition of 60 μL of stop buffer and phenol/chloroform-extracted. Aqueous phase contents were ethanol-precipitated, rinsed with 70 % ethanol and dried in a rotary dry-vac. The pellets were resuspended in 12 μL of 33 mM NaOH/ 50 % (v/v) formamide, heated to 95 °C for 5 min and snap-chilled on ice. Reaction products were electrophoresed on a 6 % urea polyacrylamide sequencing gel in 1xTBE. Gels were dried onto Whatman paper, exposed to phosphor-imager and scanned on Typhoon IP scanner (Cytiva). Experiments were repeated in three biological replicates.

Helicase assay

4 nM subtrates were incubated for 30 minutes at 30 °C with 20 nM of each CMG, Csm3-Tof1 and Mrc1 in a 20 μL reaction volume prepared in helicase buffer with 0.1 mM AMP-PNP. An equal volume of 10 mM ATP in helicase buffer was added to initiate DNA unwinding. At the indicated times, 4 μL aliquots were withdrawn and stopped by mixing with 4 μL of stop buffer containing 0.1 % SDS/40 mM EDTA. Except for the experiments in Supplementary Figure 2, reactions were supplemented with 20 nM un-labeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the labeled strand in template to prevent the re-annealing of the product strands and 200 nM (dT)40 (2602) to sequester free CMG, one minute after the initiation of unwinding. Reaction products were electrophoresed on 8 % (39:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) native polyacrylamide gels in 1xTAE for 2 hours at 75 V. Gels were dried on a Whatman sheet, exposed to phosphor-imager and scanned on Typhoon IP scanner (Cytiva). The bands were quantified using ImageJ and plotted using GraphPad Prism software. Experiments were repeated in three biological replicates.

Sample preparation for cryo-EM analysis

0.25 μM yeast or human CMG, Csm3-Tof1/TIM-TIPIN and Mrc1/ CLASPIN were incubated with 5 μM template DNA and 100 μM AMP-PNP for 30 minutes at 30 °C (yeast proteins) or 37 °C (human proteins) in a 20 mL reaction containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6/100 mM potassium acetate/10 mM magnesium acetate/2.5 mM DTT/0.02 % NP40-S. DNA unwinding was initiated by adding 5 mM ATP to the reaction and incubating the reaction for another 30 minutes. 4 μL of a reaction were spotted on graphene oxide-layered 400-mesh Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 Au grids (EM Sciences), incubated for 30 seconds and blotted for 15 or 30 seconds. Grids were plunge-frozen into liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Scientific) maintained at 4°C and 95% humidity.

Cryo-EM data collection

Cryo-EM samples were imaged using a 300keV FEI Titan Krios microscope equipped with a K3 summit direct electron detector (Gatan). Images were recorded with SerialEM (70) in super-resolution mode at 29,000x, corresponding to a pixel size of 0.413 Å/px. Movies were recorded over 3 sec at a dose rate of 15 e—/pix/sec (0.05 sec/frame), yielding a total dose of 66 e—/Å2.

Cryo-EM data processing

All movies were gain-corrected, 2x Fourier-cropped to 0.826Å/px, CTF estimated, and aligned using whole-frame and local motion correction in CryoSPARC v.4.0.0 (71). Blob-based autopicking was used with to select initial particle images within cryoSPARC Live, after which iterative rounds of 2D classification were performed and best 2D class averages were used to generate an ab initio 3D model. The initial model was used alongside six false-positive “decoy” 3D noise classes in iterative rounds of heterogenous refinement to select for true positive particles from among the full stack of blob-picked particles. After ten rounds of heterogenous refinement, a further round of 2D classification was used to manually curate a selection of particles for use in training a convolutional neural network particle picker (72). All Topaz-picked particles (~1.9M) were extracted at 0.826 Å/px, binned 2x to 1.652 Å/px, and heterogeneously refined as previously described. The final particle stack (294,032) was then re-extracted at 0.826 Å/px prior to Bayesian Polishing in RELION-4 (73). Polished particles were imported to CryoSPARC and refined using non-uniform refinement with local CTF estimation and higher-order aberration correction on particles separated by optical group. These particles were 3D classified to distinguish conformational heterogeneity among the MCM C-tier and G-quadruplex, in addition to a population of particles which lacked Tof1-Csm3. These particles were again refined using non-uniform refinement followed by local refinements of each the N-tier, C-tier, Cdc45-GINS, and Tof1-Csm3 with or without signal subtraction of the rest of the complex. Importantly, masks around each domain were 40 Å soft-padded to reduce boundary artifacts, and slightly overlapped with other masks to aid in composite map generation. Individual local refinements were density-modified in Phenix (74) and joined into a composite map using Phenix’s combine-focus-maps tool.

Model building and refinement

Composite maps were used for de novo model building using the automated graph neural network ModelAngelo (75). The models were manually rebuilt to fit the EM density in COOT (76) and geometrically improved using ISOLDE (77). Iterative real-space refinement in Phenix and manual correction in COOT was used to refine the model (78). All structural figures were generated in PyMOL (Schrodinger, LLC. 2010. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.4) and ChimeraX (79).

DNA replication assays with purified yeast proteins

Reactions were performed as described (5). Experiments were repeated in three technical replicates.

DNA replication assays with purified human proteins

Reactions were performed at 37 °C in 25 mM HEPES-KOH pH-7.6/125 mM potassium glutamate/10 mM magnesium acetate/0.1 mg/mL BSA/1 mM DTT. The concentrations of other components in a reaction were as follows: 1 nM DNA template, 0.1 nM hPol δ, 10 nM hPol α, 120 nM hRPA, 20 nM hCMG, 20 nM TIM-TIPIN, 20 nM CLASPIN, 20 nM AND1, 20 nM hPCNA, 20 nM hRFC, 20 nM CTF18-RFC, 20 nM hPol ε, 50 μM AMP-PNP, 40 μM dNTPs, 200 μM G/C/UTP, 5 mM ATP and 33 nM (1 μCi) [α32P] dATP. Reactions were performed by pre-incubating hCMG, TIM-TIPIN, CLASPIN and AND1 for 10 min with DNA template in the presence of 0.1 mM AMPPNP. Reactions were then diluted two-fold by mixing an equal volume of reaction mix containing the remaining nucleotide and protein factors. Aliquots were drawn at the indicated times and stopped by either adding 50 mM EDTA for denaturing gel analysis or heat inactivation at 80 °C for native gel analysis. For denaturing gel analysis, DNA was isolated from the reactions using SpeedBead magnetic carboxylate (Cytiva). For this, 10 μL of stopped reaction mix was added to 18 μL of SpeedBead mix (2 % SpeedBeads/10 mM Tris pH-8.0/2.5 M sodium chloride/20 % PEG 8000/1 mM EDTA). The beads were separated on a magnetic rack and rinsed three times with 85 % (v/v) ethanol. DNA was eluted with 20 μL of 100 mM NaOH and electrophoresed on a 0.8 % agarose gel for 3 hours at 40 V in 30 mM NaOH/2 mM EDTA. Gels were neutralized with 5 % (w/v) TCA, dried onto Whatman paper and exposed to phosphor imager.

For native gel analysis, reactions were heat-inactivated for 20 minutes at 80 °C and treated with 2.5 units of Quick CIP (NEB) for 30 min to remove phosphate radiolabel from unincorporated nucleotides. The reactions were subsequently supplemented with 0.5 % SDS, 10 mM EDTA and 0.8 units of Proteinase K (NEB) and incubation continued for 30 min. The products electrophoresed for 200 min at 55 V on 0.8 % agarose gels in 1xTAE. Gels were dried on Whatman paper and exposed to phosphor imager.

Experiments were repeated in three technical replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank M. Jason de la Cruz at the MSKCC Richard Rifkind Center for Cryo-EM for assistance with data collection and the MSKCC HPC group for assistance with data processing. We thank Lucia Wang for help with artwork.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health grant R35GM152094 (DR)

National Institutes of Health grant R35GM126907 (KJM)

National Institutes of Health – NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748

Basic Research Innovation Award (DR, RKH)

Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Prize (RKH)

Footnotes